Even though a third and fourth dose (first and second booster, respectively) of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) messenger RNA vaccine leads to higher SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific antibody response and neutralizing activity against the wild type [1–3], data on the Omicron variant B.1.1.529/BA.1 (BA.1)-specific neutralizing antibodies in chronic intermittent haemodialysis patients (CIHD) are still scarce [4].

We prospectively investigated 76 HD patients in three outpatient dialysis centres (Supplementary Table S1). Neutralizing antibody titres specific for BA.1 were measured with a plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) before and 4 weeks after the second booster vaccine [0.25 ml (50 µg), RNA-1273, Moderna, Cambridge, MA, USA; for details of the vaccination regimens see Supplementary Table S2].

We also assessed antibody levels targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain (S-RBD) and potentially neutralizing antibodies by surrogate neutralization assay [further referred to as surrogate neutralizing antibodies (SNA)] against wild-type SARS-CoV-2 6 weeks before, directly before and 4 weeks after the second booster vaccination (Fig. 1).

Figure 1:

Flowchart of the study setup. Samples were collected at three different time points to evaluate the dynamics of the patients’ immunization status by different methods.

In the 3 months of follow-up after the second booster vaccination, SARS-CoV-2 infections and symptom severity were documented. Asymptomatic infections were detected either by occasional polymerase chain reaction testing of nose and throat swabs or a positive nucleocapsid antibody test in blood samples.

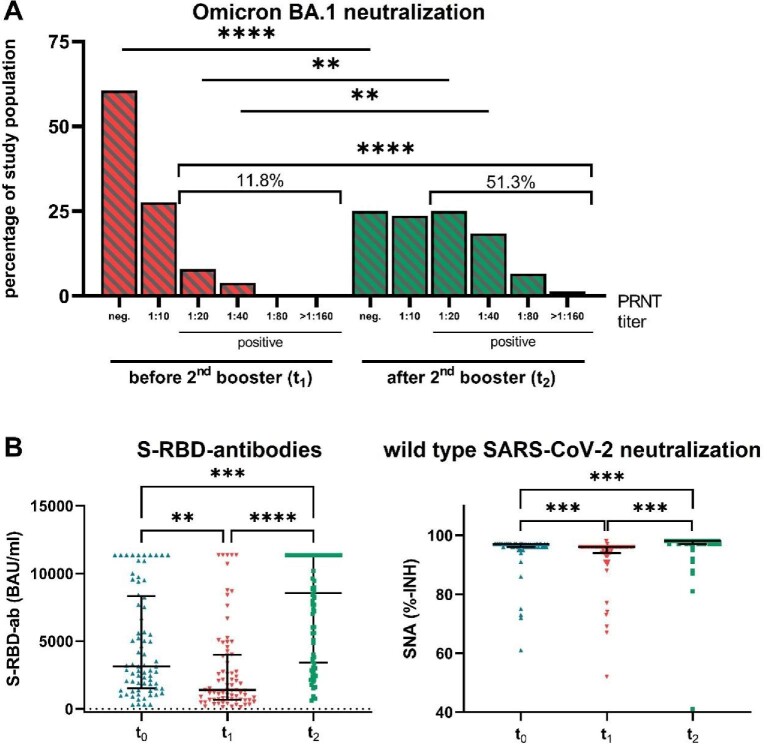

Notably, the BA.1-specific PRNT revealed that only 11.8% (9/76) of our patients were positive (titre ≥1:20) before the second booster (Fig. 2A). Four weeks after the second booster, 51.3% (39/76) showed a positive result in BA.1-specific PRNT, which is a 4.3-fold increase compared with the positivity rate before the second booster (P < .001). This immune response is lower than that reported for the general population (7.2-fold) [5].

Figure 2:

Results. (A) Percentage of study population grouped by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron B.1.1.529/BA.1-specific neutralizing antibody titre assessed by PRNT at two different time points (t1 = before and t2 = 4 weeks after the second booster). (B) Antibody response in plasma samples taken at three different time points [t0 = 6 weeks after the first booster, t1 = 12 weeks after the first booster and before the second booster and t2 = 4 weeks after the second booster with mRNA-1273 (Moderna)]. Data are expressed as median (interquartile range). **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001, ****P ≤ .0001 (Friedman test).

However, we observed a 6-fold increase in S-RBD antibody levels (P < .0001) after the second booster and a response rate for SNA against wild-type of 98.7% (75/76) (Fig. 2B). There was a strong correlation between S-RBD levels and Omicron BA.1 PRNTs (Spearman’s rank correlation, ρ = 0.69; Supplementary Table S4, Fig. S1).

A total of 12 of 76 (15.8%) patients were infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the 3 months following the second booster vaccination (from February to May 2022; dominated by the SARS-CoV-2 BA.1 and BA.2 variants [6, 7]). Six of these 12 patients were negative in the corresponding Omicron BA.1 PRNT (neutralization titres in Omicron BA.1 PRNTs were also applicable for BA.2 [8]).

Four infections were asymptomatic (three patients were positive in the Omicron BA.1 PRNT), seven patients had mild symptoms (three were positive in the Omicron BA.1 PRNT) and one patient (negative in the PRNT) required inpatient therapy of SARS-CoV-2-induced moderate pneumonia and diarrhoea.

The fact that 6 PRNT negative HD patients were not life-threateningly ill upon SARS-CoV-2 infection suggests that not only virus neutralization by the specific antibody response is of relevance, but other mechanisms such as T-cell immunity and non-neutralizing antibodies are active for the prevention of severe coronavirus disease 2019 [9, 10].

Our findings reveal a high response rate for SNA against wild-type after the second booster, whereas the BA.1-specific neutralizing antibody response rate achieved only 51.3%. This limited neutralizing potency against BA.1 refers to an antibody immune evasion of SARS-CoV-2 [11]. Further studies are required to show whether SARS-CoV-2 variant-adapted vaccines can enhance protection in this highly vulnerable population, e.g. by optimizing neutralizing activity against Omicron variants.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the teams of the dialysis centres for their support and all patients for their participation. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Association of Hesse, Germany (reference 2021-2437-evBO; 21 July 2021). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Contributor Information

Eugen Ovcar, KfH Kuratorium For Dialysis and Transplantation, Offenbach/Main, Germany; Department of Internal Medicine III, Internal Medicine, Nephrology, Rheumatology, Sana Klinikum, Offenbach/Main, Germany.

Sammy Patyna, Department of Internal Medicine III, Division of Nephrology, University Hospital Frankfurt, Goethe University Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany.

Niko Kohmer, Institute for Medical Virology, University Hospital Frankfurt, Goethe University Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany.

Elisabeth Heckel-Kratz, KfH Kuratorium For Dialysis and Transplantation, Gross-Gerau, Germany.

Sandra Ciesek, Institute for Medical Virology, University Hospital Frankfurt, Goethe University Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany; German Centre for Infection Research, External partner site, Frankfurt, Germany; Fraunhofer Institute for Molecular Biology and Applied Ecology, Branch Translational Medicine and Pharmacology, Frankfurt, Germany.

Holger F Rabenau, Institute for Medical Virology, University Hospital Frankfurt, Goethe University Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany.

Ingeborg A Hauser, Department of Internal Medicine III, Division of Nephrology, University Hospital Frankfurt, Goethe University Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany.

Kirsten de Groot, KfH Kuratorium For Dialysis and Transplantation, Offenbach/Main, Germany; Department of Internal Medicine III, Internal Medicine, Nephrology, Rheumatology, Sana Klinikum, Offenbach/Main, Germany.

FUNDING

This research was funded by a private donation.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, K.D.G., E.H.K., E.O. and S.P.; methodology, S.C., H.F.R. and N.K.; validation, S.C., H.F.R. and N.K.; formal analysis, S.P; investigation, E.O. and E.H.K.; resources, K.D.G. and E.H.K.; data curation, E.O. and E.H.K.; writingoriginal draft preparation, S.P., E.O.; writingreview and editing, K.D.G., I.A.H., N.K. and H.F.R.; visualization, S.P.; supervision, K.D.G., I.A.H.; project administration, E.O. and K.D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

E.O., S.P., H.F.R., S.C., I.A.H. and K.D.G. declare no conflicts of interest. E.H.K. received a registration fee from Amgen. N.K. received a speaker fee from Abbott Laboratories for a short presentation on useful algorithms for SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing.

REFERENCES

- 1. Füessl L, Lau T, Rau Set al. Humoral response after SARS-CoV-2 booster vaccination in hemodialysis patients with and without prior infection. Clin Kidney J 2022;15:1633–5. 10.1093/ckj/sfac148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cohen Hagai K, Shashar M, Nacasch Net al. MO887: humoral response to the Pfizer BNT162b2 vaccine booster dose in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2022;37(Suppl 3):gfac083.069. 10.1093/ndt/gfac083.069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patyna S, Eckes T, Koch BFet al. Impact of Moderna mRNA-1273 booster vaccine on fully vaccinated high-risk chronic dialysis patients after loss of humoral response. Vaccines (Basel) 2022;10:585. 10.3390/vaccines10040585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anft M, Blazquez-Navarro A, Frahnert Met al. Inferior cellular and humoral immunity against Omicron and Delta variants of concern compared with SARS-CoV-2 wild type in hemodialysis patients immunized with 4 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine doses. Kidney Int 2022;102;207–8. 10.1016/j.kint.2022.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Regev-Yochay G, Gonen T, Gilboa Met al. Efficacy of a fourth dose of Covid-19 mRNA vaccine against Omicron. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1377–80. 10.1056/NEJMc2202542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robert Koch Institut. Wöchentlicher Lagebericht des RKI zur Coronavirus-Krankheit-2019 (COVID-19). 10 February 2022, p. 37, Table 7, last row, Gesamt (Total in Germany): Omicron B.1.1.529 98,4%. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/Wochenbericht/Wochenbericht_2022-02-10.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (3 October 2022, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robert Koch Institut. Wöchentlicher Lagebericht des RKI zur Coronavirus-Krankheit-2019 (COVID-19). 19 May 2022, p. 29, Table 4, last row, KW18 (Calendar week 18, 2/05-8/05/2022): BA.1 0,7%, BA.2 97,4%. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/Wochenbericht/Wochenbericht_2022-05-19.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (3 October 2022, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilhelm A, Widera M, Grikscheit Ket al. Limited neutralisation of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.1 and BA.2 by convalescent and vaccine serum and monoclonal antibodies. EBioMedicine. 2022;82:104158. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heitmann JS, Bilich T, Tandler Cet al. A COVID-19 peptide vaccine for the induction of SARS-CoV-2 T cell immunity. Nature 2022;601:617–22. 10.1038/s41586-021-04232-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dugan HL, Stamper CT, Li Let al. Profiling B cell immunodominance after SARS-CoV-2 infection reveals antibody evolution to non-neutralizing viral targets. Immunity 2021;54:1290–303.e7. 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mannar D, Saville JW, Zhu Xet al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: antibody evasion and cryo-EM structure of spike protein–ACE2 complex. Science 2022;375:760–4. 10.1126/science.abn7760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.