ABSTRACT

Drug combinations and drug repurposing have emerged as promising strategies to develop novel treatments for infectious diseases, including Chagas disease. In this study, we aimed to investigate whether the repurposed drugs chloroquine (CQ) and colchicine (COL), known to inhibit Trypanosoma cruzi infection in host cells, could boost the anti-T. cruzi effect of the trypanocidal drug benznidazole (BZN), increasing its therapeutic efficacy while reducing the dose needed to eradicate the parasite. The combination of BZN and COL exhibited cytotoxicity to infected cells and low antiparasitic activity. Conversely, a combination of BZN and CQ significantly reduced T. cruzi infection in vitro, with no apparent cytotoxicity. This effect seemed to be consistent across different cell lines and against both the partially BZN-resistant Y and the highly BZN-resistant Colombiana strains. In vivo experiments in an acute murine model showed that the BZN+CQ combination was eight times more effective in reducing T. cruzi infection in the acute phase than BZN monotherapy. In summary, our results demonstrate that the concomitant administration of CQ and BZN potentiates the trypanocidal activity of BZN, leading to a reduction in the dose needed to achieve an effective response. In a translational context, it could represent a higher efficacy of treatment while also mitigating the adverse effects of high doses of BZN. Our study also reinforces the relevance of drug combination and repurposing approaches in the field of Chagas disease drug discovery.

KEYWORDS: Chagas disease drug discovery, drug combination, drug repurposing, chloroquine, benznidazole

INTRODUCTION

Chagas disease (CD), caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, is an important public health problem, affecting 6 to 7 million people worldwide. According to World Health Organization (WHO) (2022), 70 million people are at risk with 30,000 new cases reported each year (1, 2). Although endemic in the American continent, this disease has spread to nonendemic, developed areas such as Europe, Japan, and Australia, due to the globalization/migration process (3). T. cruzi parasites are vectorially transmitted to human hosts by the hematophagous triatomine bug as metacyclic trypomastigote forms. Occasionally, the transmission can also occur orally by ingestion of food and drink contaminated with T. cruzi, as well as by nonvectorial routes, such as organ transplantation, congenitally, or blood transfusion (4).

The most important clinical issue associated with CD is chronic chagasic cardiopathy (CCC), developed in 20 to 30% of infected individuals and characterized by progressive heart failure and severe arrhythmia, which can lead to death. Besides the use of supportive care for heart failure, the only treatment available for end-stage CCC is heart transplantation, which is expensive, highly complex, and largely unavailable to most patients; even for those who enter the heart transplant list, the mortality rate for CCC patients is higher than those with other heart diseases (4, 5).

The only available anti-T. cruzi drugs, benznidazole (BZN) and nifurtimox (NFX), were introduced over 50 years ago and face serious efficacy and safety issues (6). Despite being effective in treating acutely infected patients and early infection in children, they diverge to prevent CCC development and progression in chronically infected adults, the phase when most patients are diagnosed (7). In addition, BZN and NFX induce frequent and important side effects, including skin irritation, neurotoxicity, and digestive system disorders, which are poorly tolerated by patients (8, 9). Recent efforts have advanced two azoles (inhibitors of T. cruzi ergosterol biosynthesis), posaconazole (POS) and ravuconazole (RAV), to clinical studies. Despite their promising in vitro and in vivo activity, POS and RAV failed in phase II clinical trials due to their low efficacy against CD (10, 11). Combinatory regimens of BZN and POS were tried, but the treatment had no synergistic effect on parasite eradication in infected patients (12). Thus, the collection of recent data highlights the challenge of developing novel, low-cost, safe, and effective CD treatments.

Corroborating the antichagasic chemotherapy paradigm, it is known today that even drugs that yield strong “in vitro” results and are efficient in curing acutely infected patients or experimental animals (such as BZN) are not able to eradicate the parasite when used in the chronic phase (6, 13–15), suggesting the existence of other factors that favor the persistence of the parasite even under the effect of trypanocidal compounds. Knowing that invasion and replication of pathogens subvert host cell factors, such as plasma membrane and actin networks (16, 17), endocytic pathway (18), immune response (19), and host gene expression (20), a new drug screening strategy has emerged that is centered on interfering with host cell factors required for pathogen internalization and invasion, survival, and replication. In fact, drugs that target host factors have been reported in the control of several pathogens, including HIV and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) viruses, Plasmodium falciparum, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (21–25).

In this context, we selected two repurposed drugs, colchicine (COL) and chloroquine (CQ), which are demonstrated to affect different stages of host-T. cruzi interaction. COL, an anti-inflammatory drug used to treat gouty arthritis, is able to bind to tubulins, blocking the polymerization of microtubules (26) and directly interfering with T. cruzi internalization (27). CQ, an antimalarial drug, is a lysosomotropic pH-raising agent that inhibits the escape of trypomastigotes from vacuolar compartment to cytoplasm, thereby impeding lysosome-dependent invasion and inhibiting autophagy (28). Both drugs were combined with the trypanocidal drug BZN in an attempt to maximize its effect. Using the drug combination strategy, we aim at interfering with different stages of T. cruzi invasion, cytoplasm translocation, parasite differentiation, and trypomastigote/amastigote viability, with the expectation of reducing or perhaps eradicating T. cruzi from the host cell and infected animals.

RESULTS

Drug toxicity in different host cell lines.

Prior to the evaluation of drug and drug combination activity against T. cruzi parasites, we performed cytotoxicity assays for BZN, COL, CQ, and the combination of these three drugs on HEK293T, THP-1, U2OS, and LLC-MK2 cell lines. Drug toxicity was determined by measuring cellular metabolic activity through a 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT)-based assay.

In general, drugs presented low cytotoxicity across the four cell lines (Table 1). While BZN was not toxic for any of the cell lines at tested concentrations, CQ presented a variable and low toxicity (50% cytotoxic concentration [CC50] = 50.7 to 100.4 μM), and COL exhibited low toxicity in HEK293T and THP-1 cells at higher concentrations (CC50 of 105.6 and 146.3 μM, respectively). Interestingly, regarding drug combinations, CC50 values were higher than 200 μM for all cell lines, demonstrating that the addition of CQ and COL at 5 μM to BZN did not increase the cytotoxicity of this compound alone.

TABLE 1.

Cytotoxicity of drugs and drug combination on different host cells

| Compound(s) | CC50 value (μM) according to cell linea |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK293T | THP-1 | U2OS | LLC-MK2 | |

| Benznidazole | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 |

| Chloroquine | 83.7 (±26.7) | 50.7 (±26.9) | 80.4 (±16.7) | 100.4 (±29.2) |

| Colchicine | 105.6 (±69.3) | 146.3 (±101.3) | >200 | >200 |

| Drug combination (5 μM CQ and 5 μM COL + variable BZN concentrations) | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 |

Data are represented as mean (±SD) of at least two independent experiments. Drug exposure = 72 h.

Activity of drugs and drug combinations against T. cruzi Y strain.

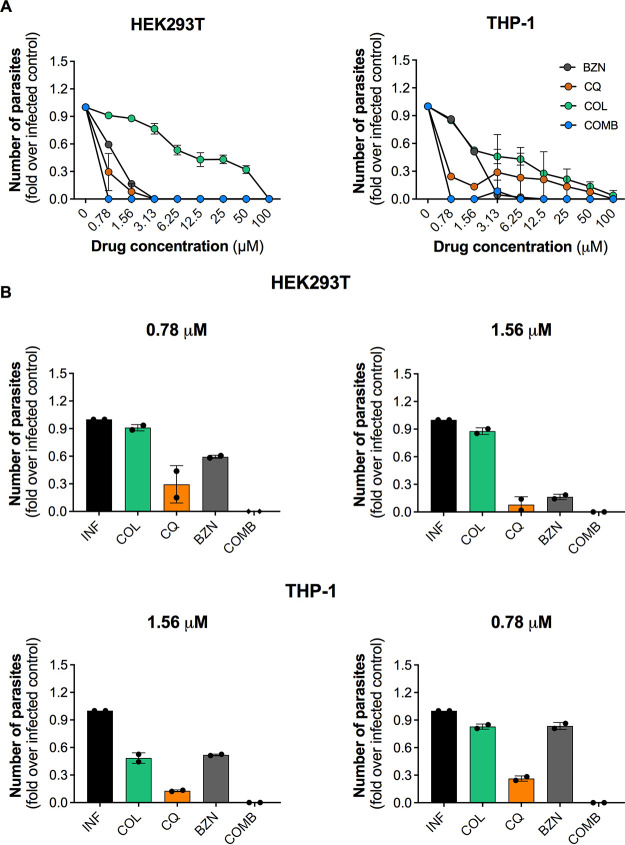

To assess the antiparasitic activity of drugs and drug combinations, we carried out a trypomastigote release assay. HEK29T and THP-1 cell lines were infected with T. cruzi Y (a partially benznidazole-resistant) strain (29) and then treated with different concentrations of drugs and drug combinations. The number of parasites released to the supernatant at the peak day after in vitro infection was calculated to determine drug activity (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

In both host cells, drugs presented a concentration-dependent effect on trypomastigote release suppression (Fig. 1A), which was more efficacious in HEK293T cells than THP-1 cells. The reference drug BZN was similarly active in both cell lines and displayed its maximum activity until 3.125 μM. Regarding the tested compounds, CQ demonstrated a variable effect on distinct host cells, reaching 100% inhibition of trypomastigote release at 3.125 and 100 μM in HEK293T and THP-1, respectively. Weak inhibitory activity of COL was observed in both cell lines, in which only the concentration of 100 μM was able to completely eradicate parasite release. The drug combination eradicated parasites released up to the lowest BZN concentration (0.78 μM), a reduction of at least 4-fold in the most efficacious concentration of BZN alone.

FIG 1.

Activity of drugs and drug combinations against T. cruzi Y strain in HEK293T and THP-1 cell lines. Cells were infected with trypomastigotes of the Y strain at an MOI of 10 and treated with different concentrations of drugs (100 to 0.78 μM). For the combinatory treatment (COMB), COL and CQ at 5 μM were combined with variable concentrations of BZN (100 to 0.78 μM). Treatment was performed every other day up to 144 h for HEK293T cells and 192 h for THP1 cells when the number of trypomastigotes released in culture supernatant was determined by parasite counting. (A) Effect of different concentrations of BZN, COL, CQ, and drug combinations on trypomastigote release. (B) Comparison of BZN, COL, and CQ activities at 0.78 and 1.56 μM on both cell lines. In combination treatment, “COMB” refers to 5 μM COL and CQ with either 1.56 or 0.78 μM BZN. Results are based on the quantification of the number of trypomastigotes released in supernatant and are shown as fold change compared to nontreated infected control. Data represent average ± SD of two independent experiments.

When compared to the treatment of compounds alone, the drugs combined with BZN at 1.56 and 0.78 μM yielded the strongest reduction in trypomastigote release in both infected cell lines tested (Fig. 1B). The combination treatments with BZN at 0.78 μM in both cell lines (and at 1.56 μM in THP-1 cells) were significantly more effective than treatments with BZN, COL, and CQ alone. Also, the abovementioned drug combinations were the only treatments under these concentrations that completely eradicated trypomastigotes release. Interestingly, CQ was also effective against T. cruzi in both cell lines, with >70% inhibition of trypomastigote release. COL presented only marginal activity under these concentrations. The dose-response curves and the 50% effective concentration (EC50) values for each condition are shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. Taken together, these results indicate that the tested drugs potentiated the effect of BZN, resulting in reduced release of trypomastigotes from infected mammalian cells.

In order to evaluate if the action of the drugs could be due to a direct effect on nonreplicative trypomastigote forms, T. cruzi trypomastigotes of Y strain were incubated with different concentrations of CQ and BZN for 24 h. CQ and BZN exhibited a limited effect on decreasing trypomastigotes viability. In fact, at 200 μM concentration, maximum inhibitions of 20 and 32.7%, respectively, were observed. Lower concentrations of both compounds were not able to reduce parasite viability significantly (data not shown).

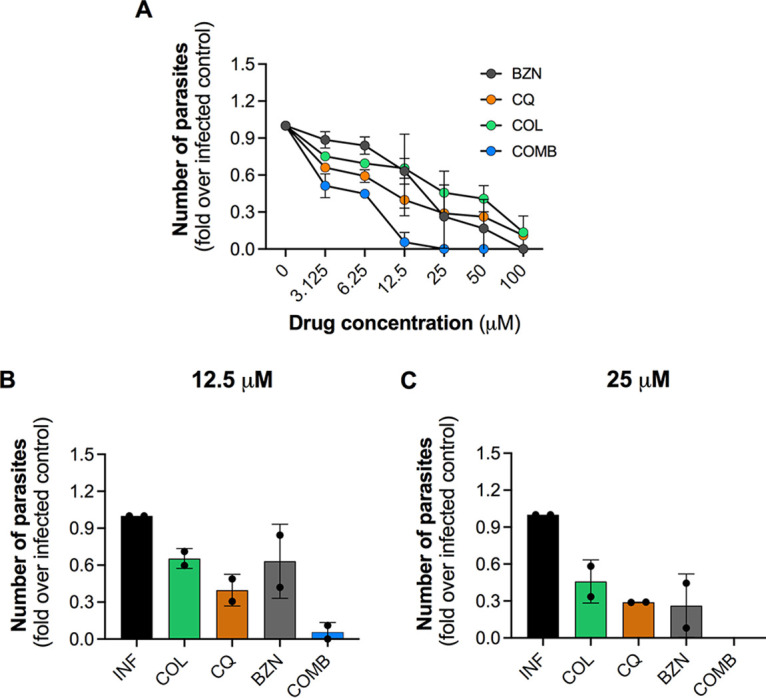

Activity of drugs and drug combinations against a BZN-resistant strain.

To verify if drugs and drug combinations presented activity against distinct T. cruzi strains, we performed a dose-response study against the Colombiana strain, a highly virulent and benznidazole-resistant strain (29).

As expected, compared to the T. cruzi Y strain (Fig. 1), the Colombiana strain seemed to be more tolerant to BZN and other tested drugs (Fig. 2), as observed by changes in the profile of dose-response curves. Moreover, BZN monotherapy completely abrogated trypomastigote release only at the maximum concentration tested of 100 μM. CQ and COL were not able to reduce parasite release to undetectable levels, although they presented high activities at 100 μM (>85%) (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Activity of drugs and drug combinations against the T. cruzi Colombiana strain in the THP-1 cell line. Cells were infected with Colombiana strain at an MOI of 10 and treated with different concentrations of drugs (100 to 3.125 μM). For the combinatory treatment, COL and CQ at 5 μM were combined with variable concentrations of BZN (100 to 3.125 μM). Treatment was performed every other day up to 192 h (peak day of trypomastigote release) when the number of trypomastigotes released in culture supernatant was determined by parasite counting. (A) Effect of different concentrations of BZN, COL, CQ, and drugs combination in trypomastigote release. (B and C) Comparison of BZN, COL, and CQ activities at 12.5 and 25 μM. In combination treatment, “COMB” refers to 5 μM COL and CQ with either 12.5 or 25 μM BZN. Results are based on the quantification of the number of trypomastigotes released in supernatant and are shown as fold change compared to nontreated infected control. Data represent average ± SD of two independent experiments.

Drug combinations, i.e., 5 μM COL and 5 μM CQ combined with variable concentrations of BZN, showed a significant effect starting from 12.5 μM BZN, presenting an activity 12-fold higher than BZN alone (Fig. 2B). However, the maximum inhibition of 100% in trypomastigote release was achieved only when drugs were combined with BZN at 25 μM (Fig. 2C). The dose-response curves and the EC50 values for each condition are presented in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material.

Overall, data show that, despite the variable levels of activity between distinct T. cruzi strains, the tested compounds were able to boost BZN’s antiparasitic activity, even against a highly resistant parasite strain.

Effect of drugs and drug combinations on intracellular amastigotes and trypomastigote release.

Given that drugs and drug combinations reduced trypomastigote release in HEK29T and THP-1 cell lines (Fig. 1 and 2), we further investigated their activities in U2OS cells by accessing the following two parameters in parallel: trypomastigotes released in supernatant of infected cells and the number of intracellular amastigotes. The U2OS osteosarcoma-derived human cell line was used in the assays since culture grows as homogeneous monolayers and the cells present a large cytoplasm area, which is ideal for image analysis and quantification of T. cruzi intracellular amastigotes (30). We also opted to use a stock of parasites recently isolated from animals since it presents higher biological relevance than culture-adapted strains. Compared to a parasite stock adapted to in vitro culture, the animal- isolated strain was more infective, presenting superior fitness, higher infection ratio, and a higher number of intracellular amastigotes over time (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

Preliminary experiments showed an increased cytotoxicity of tested compounds in the infection protocol, especially for COL (CC50 = 0.02 μM) (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material); therefore, COL was removed from the drug combinations, and CQ was tested at two different concentrations, 1 and 5 μM, to establish the best concentration to be combined with BZN.

Figure 3A shows representative images of T. cruzi infection in human cells for both controls (infected dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]-treated cells and noninfected cells) and compound-treated wells, evidencing the high activity of BZN + 5 μM CQ compared to BZN alone. BZN, which was used as a reference drug, exhibited high efficacy (100%) and potency (EC50 = 5.2 μM) against intracellular amastigotes with no toxicity in host cells. CQ also presented high anti-T. cruzi activity at a low micromolar concentration, with EC50 = 3.5 μM, and a maximum activity of 100%; however, cytotoxicity was observed (CC50 = 10.3 μM), resulting in a relatively low selective index of 3 (Fig. 3B and C).

FIG 3.

Efficacy of drugs and drug combinations against T. cruzi intracellular amastigotes. U2OS in 96-well plates were infected with T. cruzi Y strain at an MOI of 30 and treated with compounds in serial dilution by a factor of 3-fold. The following concentrations were used: 400 to 0.02 μM for BZN and 80 to 0.004 μM for CQ. For the combinatory treatment, fixed concentrations of CQ at either 1 or 5 μM were combined with variable concentrations of BZN (400 to 0.02 μM). Treatment was performed every other day up to 144 h when the number of trypomastigotes released in culture supernatant was determined by parasite counting, and the number of intracellular amastigotes and the infection ratio was determined by high content analysis. (A) Representative images of T. cruzi-infected U2OS cells in the assay endpoint (144 h postinfection), showing both infected (DMSO treated) and noninfected controls as well as the treatment with BZN alone and combined with CQ at 1 and 5 μM. (B to E) Dose-response curves of BZN, CQ, and drug combinations. The x axis indicates the log of compound concentration (molar); the left y axis (blue color curves) indicates the normalized antiparasitic activity, which represents the inhibition of infection in relation to controls; and the right y axis (red color curves) indicates compounds cytotoxicity, which represents the reduction of host cells number in relation to infected control. Values presented in graphs refer to both EC50 and CC50 values and represent average ± SD of four independent experiments. (F to I) Effect of drugs and drug combinations on both intracellular amastigote number and trypomastigote number. As indicated, the left y axis refers to the number of intracellular amastigotes (dark gray bars), and the right y axis refers to the number of trypomastigotes released in supernatant of infected cells (light gray bars). Data represent average ± SD of three (amastigotes) and two (trypomastigotes) independent experiments.

Regarding drug combinations, while there was no gain in BZN potency and efficacy when adding CQ at 1 μM, the addition of CQ at 5 μM significantly increased BZN potency, with all tested concentrations displaying antiparasitic activity of >70%. In this case, cytotoxicity was found only at the highest concentration of BZN (400 μM), in which the number of cells reduced by 33% (Fig. 3D and E). Cell viability assays also demonstrated that the BZN+CQ combination was not toxic at tested concentrations (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material).

The effects of drugs seemed to be more pronounced against trypomastigotes than amastigotes. While 0.04 μM CQ was able to significantly reduce the number of trypomastigotes released in culture supernatant (2-fold lower compared to the infected control), concentrations ≤1 μM seemed not to affect amastigote viability (Fig. 3F).

A more prominent difference was observed for BZN; while all tested concentrations inhibited trypomastigote release, at least 3-fold compared to infected controls, only concentrations of >1.6 μM were active against amastigotes. Moreover, even at the highest concentration of 400 μM, BZN did not eliminate all intracellular amastigotes, whereas concentrations greater than 5 μM had 100% inhibition of trypomastigote release at 144 hours postinfection (hpi) (Fig. 3G).

No differences were observed between the activities of BZN alone and BZN combined with CQ at 1 μM (Fig. 3H). Conversely, the combination of BZN and CQ at 5 μM resulted in a strong reduction in the number of intracellular amastigotes (>60%) and complete inhibition of parasite release in culture supernatant at all tested concentrations (Fig. 3I).

Altogether, these results demonstrate the effectiveness of the BZN plus 5 μM CQ combination against T. cruzi infection by significantly reducing the number of intracellular amastigotes and inhibiting/delaying trypomastigote release.

Dynamics of T. cruzi infection after drug removal.

The experiments above demonstrated that although the combination of BZN and CQ can suppress trypomastigote release, it does not eliminate all intracellular amastigotes. Nevertheless, it remained unclear if residual amastigotes were viable and could proliferate after drug removal. To address these questions, a washout assay was designed using LLC-MK2 cells infected with the T. cruzi Y strain. After 7 days of treatment, drugs were removed and cultures were maintained for an additional period of 7 days, when infection was assessed for trypomastigote release and intracellular amastigotes. The LLC-MK2 was used in this experiment due to its robustness, relatively slow growth, and capacity of maintaining the infection for a longer period of time, which allowed us to monitor the infection up to 14 days (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). The schematic representation of the washout assay and the representative images of infection are shown in Fig. 4A and B.

FIG 4.

Dynamics of T. cruzi infection after drugs removal. LLC-MK2 cell line in 96-well plates was infected with T. cruzi Y strain at an MOI of 10 and treated with compounds in serial dilution by a factor of 3. For BZN alone, the following concentrations were used: 133.3, 14.8, 1.6, 0.18, and 0.02 μM. For the combinatory treatment, fixed concentrations of CQ at either 1 or 5 μM were combined with variable concentrations of BZN (133.3 to 0.02 μM). Treatment was performed every other day up to 144 h when drugs were removed, and cultures were maintained for an additional period of 144 h. Analyses were performed at two time points, at the end of treatment and at the assay endpoint, by counting trypomastigotes released in culture supernatant and by determining the number of intracellular amastigotes (high content analysis). (A) Schematic representation of washout assay. (B) Representative images of T. cruzi-infected LLC-MK2 cells at the end of treatment (144 hpi) and at assay endpoint (288 hpi), showing both infected and noninfected controls as well as the treatment with BZN alone and combined with CQ at 1 and 5 μM. (C and D) Effect of BZN alone and in combination with CQ considering the end of treatment and assay endpoint, respectively. As indicated by colors legend, BZN alone (gray), BZN + CQ 1 μM (blue), and BZN + CQ 5 μM (pink). Results are based on the quantification of both amastigotes area and number of trypomastigotes released in supernatant and are shown as fold change compared to nontreated infected control. Data represent average ± SD of three (amastigotes) and two (trypomastigotes) independent experiments.

On the final day of the treatment, i.e., 144 h postinfection (Fig. 4C), we observed that BZN combined with 5 μM CQ presented higher efficacy compared to that of other treatments, reducing the load of intracellular amastigotes and trypomastigotes released in the supernatant by at least 50% compared to infected nontreated controls. Also, drug effect was more pronounced on inhibiting trypomastigote release than intracellular amastigotes; while none of the treatments was able to fully eradicate intracellular amastigotes, higher concentrations of BZN alone (133.3 μM) or in combination (133.3 and 14.8 μM) completely abolished trypomastigote release 144 h postinfection.

After drug removal (Fig. 4D), we could observe parasite relapse in all conditions, although higher concentrations of BZN alone (133.3 μM) combined with CQ (BZN at 14.8 and 133.3 μM) reduced significantly both amastigote and trypomastigote recrudescence (at least 0.5-fold over the infected nontreated control). Regarding the activity of drugs against amastigotes, no differences were observed between BZN alone and combined with CQ. In addition, concentrations lower than 1.6 μM exhibited only marginal activity against intracellular parasites. Contrarily, the activity gain of drug combinations is evident in the reduction of trypomastigote release compared to BZN monotherapy. The combination of BZN + 5 μM CQ led to a suppression of at least 70% in the number of trypomastigotes in the culture supernatant, even at concentrations of ≤1.6 μM, in which the load of intracellular amastigotes was comparable to infected nontreated controls. Any of the treatments presented cytotoxicity in the tested conditions (Fig. 4C and D; see also Fig. S6).

Overall, data showed that none of the treatments was able to eliminate the parasites by 100%. However, in wells treated with the combination of BZN and 5 μM CQ, the number of trypomastigotes released in the supernatant was significantly reduced when compared to BZN treatment alone, especially for lower concentrations. Furthermore, the drug combination appears to be more active in inhibiting trypomastigote release rather than in killing amastigotes.

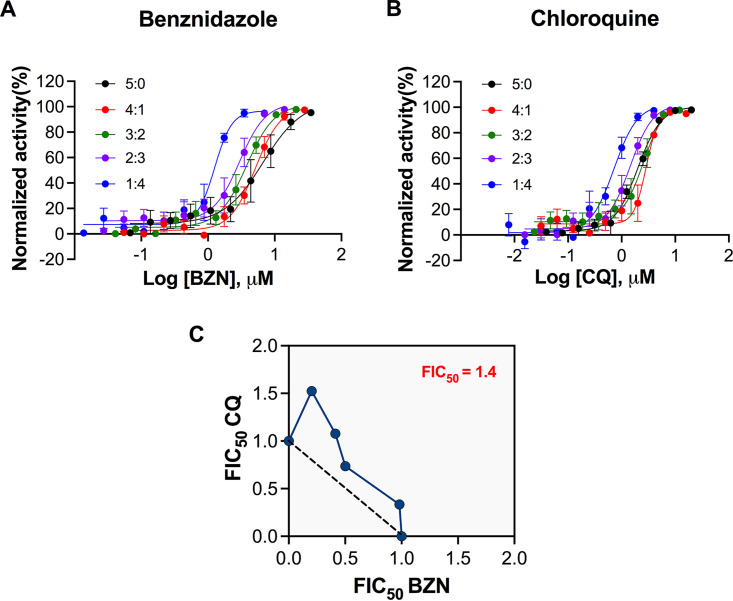

In vitro interaction between benznidazole and chloroquine.

Given that chloroquine potentiated the trypanocidal effect of benznidazole, we further investigated the interaction between both drugs by the modified fixed-ratio isobologram methodology (31–33) using U2OS cells infected by the T. cruzi Y strain.

Based on EC50 values calculated by dose-response curves (Fig. 5A and B), we determined the sum of the 50% fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC50) (∑FIC50) for each drug association (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The ∑FIC50 values varied from 1.24 to 1.73. The overall mean ∑FIC50 (x∑FIC50) which expresses the general profile of the combination, was established at 1.44, demonstrating an additive interaction (34). The additivity was confirmed by isobologram (Fig. 5C), in which all FIC50 values were located close to the additivity line.

FIG 5.

In vitro drug interactions between benznidazole and chloroquine. (A and B) Dose-response curves of benznidazole and chloroquine, respectively, for each drug combination as follows: 5:0, 4:1, 3:2, 2:3, 1:4, and 0:5. The x axis indicated the log of compound concentration (molar), and the y axis indicates the normalized antiparasitic activity. (C) Isobologram representing the in vitro interaction between BZN and CQ. Each dot shows the FIC50 values for both drugs in each drug combination. The dotted line represents the theoretical line of additivity. The xΣFIC for all drug combinations is highlighted at the upper right corner. Data represent four independent experiments.

Evaluation of efficacy of drug combination in vivo.

After establishing that CQ alone at nontoxic concentrations is capable of reducing or abrogating T. cruzi infection of mammalian cells in vitro and that CQ potentiates BZN activity against T. cruzi, we assessed the effect of the drugs, alone or in combination, on the acute infection of the BALB/c mouse with the T. cruzi Colombian strain. In our study design, infected animals were treated daily for 20 consecutive days, starting at 10 days postinfection (dpi), employing the following: BZN low dose (25 mg/kg of body weight/day) or full dose (100 mg/kg/day), CQ (50 mg/kg/day), and the combination of 50 mg/kg/day CQ and 25 mg/kg/day BZN (Fig. 6). These doses are well tolerated in murine models (35, 36). The survival was 100% in all treatment groups, since this was a nonlethal infection protocol.

FIG 6.

Therapeutic efficacy of drugs and drug combination in animal models. Female BALB/c mice were infected intraperitoneally with 5,000 blood trypomastigote forms of Colombian strain of T. cruzi. Gavage treatments of BZN 100 mg/kg/day, BZN 25 mg/Kg/day, CQ 50 mg/kg/day, and the combination of BZN 25 mg/kg/day plus CQ 50 mg/kg/day were administered daily for 20 consecutive days starting at 10 dpi. Parasitemia was assessed by optical microscopy every 5 days, starting on the first day of treatment (10 dpi) up to the assay endpoint (30 dpi). Each group was composed of 7 mice. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis is shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

In the infected vehicle-treated controls, parasitemia increased over time reaching a mean parasite number of 1.3 × 105/mL at 30 dpi. Monotherapy of 25 mg/kg/day BZN and 50 mg/kg/day CQ presented a mild effect, reducing parasitemia by 35% in comparison to the controls. In contrast, mice treated with BZN at the high dose of 100 mg/kg showed a moderate suppression of 58%.

Interestingly, the association of CQ significantly increased the antiparasitic effect of BZN, maintaining low levels of parasitemia throughout the assay period. Compared to vehicle-treated infected animals, the reduction in parasitemia was >90%, considering later time points (25 and 30 dpi). Moreover, at the assay endpoint, BZN in combination with CQ was 8-fold and 5.8-fold more effective than BZN monotherapy of 25 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg, respectively.

Overall, even though the tested combinatory regimen did not result in sterile cure in infected animals, data show that the BZN and CQ combination is more effective in vivo against T. cruzi infection than BZN monotherapy.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to investigate repurposed drugs to boost the anti-T. cruzi effect of BZN, aiming at inducing a synergic/additive effect and optimizing its therapeutic efficacy. We characterized the response of the parasite to the repurposed drugs COL and CQ; these therapeutic compounds were selected because of their known effects on blocking host cell pathways crucial to T. cruzi infection. While COL is linked to inhibiting microtube assembly by binding to tubulins, directly interfering with T. cruzi invasion (27), CQ is linked to impairing trypomastigote escape from parasitophorous vacuole to cytoplasm (28). Using the strategy of combining BZN, a trypanocidal drug, with COL and CQ, which target host cell factors, we aimed at associating different mechanisms of action to mitigate/eliminate T. cruzi infection.

Due to the high toxicity of BZN, ongoing clinical studies are assessing the effect of reducing the total dose of BZN by lowering daily doses, shortening treatment from 60 to 30 days, or using intermittent treatment regimens aimed at decreasing adverse events (37–39). Given the already low efficacy of regular BZN treatment in chronic chagasic patients, it is possible that the plan of alleviating the side effects by lowering the drug dosage might come along with a more reduced efficacy. Thus, the quest for synergic/additive drugs that enhance BZN effect while reducing the required dose is a promising strategy. Moreover, drug combinations might shorten the duration of treatments, reducing the adverse effects associated with time-dependent drug accumulation and delaying or preventing the occurrence of resistance in pathogens (40).

Another relevant approach is drug repurposing. Since it is based on employing a new therapeutic use for approved drugs, this strategy leads to a substantial reduction in development costs and timeline. Moreover, a robust data set of drug information might be available in the literature, including potential molecular targets, safety and efficacy profiles, and pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics properties (40). In fact, successful examples of repurposed drugs can be highlighted in the context of infectious diseases, such as antifungals (amphotericin B for leishmaniasis and fexinidazole for sleeping sickness), anticancer agents (miltefosine and tamoxifen for leishmaniasis), and antibiotics (paromomycin for leishmaniasis) (40, 41).

Primary in vitro cytotoxicity studies in noninfected cells indicated that CQ and COL induced low or no toxicity across different cell types. However, when tested in T. cruzi-infected cells, both drugs showed increased cytotoxicity, particularly COL, which produced CC50 values at nanomolar concentrations. Variations in cytotoxicity between infected and noninfected cells might be a result of methodological differences; while noninfected cells were evaluated by MTT-based assays, after 72 h of drug exposure, infected cells were evaluated by high content assays (determination of cell number) after 144 h of drug exposure with drug replacement every alternate day.

Experiments measuring trypomastigote release into the supernatant of infected mammalian cells demonstrate that CQ may be as potent as BZN in suppressing parasite release, whereas COL showed only mild activity at higher concentrations. The combination of the three drugs was the only treatment capable of eradicating parasite release in all tested concentrations, even at the lowest BZN concentration, with no apparent cytotoxicity, which demonstrates the superior efficacy of drug combinations compared to BZN monotherapy. Importantly, the efficacy of the drug combination was also observed against the highly BZN-resistant strain Colombiana and across different cell types, indicating that its inhibitory activity is independent of host cell types and parasite strains. Additionally, a larger panel of strains and clones (belonging to distinct T. cruzi genetic lineages) could be considered in a future study in order to confirm the broad-spectrum activity of the BZN and CQ combination as suggested by Zingales et al. (42).

Given that drugs and drug combinations demonstrated a strong activity in trypomastigote release assays, we further evaluated their activities against intracellular amastigotes (Fig. 3), recommended for assessing in vitro activity of compounds against T. cruzi (30, 43, 44), since they represent the persistent, and thus the clinically relevant, form in the chronic stage of Chagas diseases. Although previous studies have demonstrated that COL significantly reduced T. cruzi invasion in NRK and L6E9 cell lines (27), in our studies, in which drug effects were evaluated at later time points, COL presented limited effect on reducing/eliminating intracellular amastigotes. Thus, a drug combination was performed by associating only CQ and BZN. Compared to published data (30, 45), BZN alone presented increased activity in our assays, especially in terms of potency (EC50 = 5.2 μM). This divergence may have occurred due to differences in assay methodologies; while most protocols are based on a period of drug exposure of 72 or 96 h, in this study, we applied a drug exposure time of 144 h with a renewal of medium with fresh drug every alternate day, which could have intensified BZN antiparasitic effect. Furthermore, variations among parasite strains/clones belonging to different laboratories could also explain the differences in BZN susceptibility.

CQ alone was as potent as BZN against T. cruzi, presenting an EC50 value at a low micromolar concentration (EC50 = 3.5 μM). However, for both drugs, none of the noncytotoxic concentrations provided the total clearance of intracellular parasites. The removal of COL did not reduce the activity of the drug combination, suggesting that COL may not have contributed to the antiparasitic activity against trypomastigote release. BZN plus 5 μM CQ maintained a very high inhibitory effect by totally abrogating trypomastigote release and significantly reducing the number of intracellular amastigotes. Interestingly, although CQ alone was relatively toxic (CC50 = 10.3 μM), the combination of 5 μM CQ with BZN exhibited only a mild cytotoxicity at the highest concentration of BZN.

Accumulating evidence has suggested that the total clearance of T. cruzi infection seems to be an essential prerequisite for drug candidates, since residual parasites remaining after treatment may be able to recover and proliferate inside the host cells causing infection relapses (46). In a more translational context, an in vitro sterile cure could predict (or even help to explain) the success of treatments in animal models and, lastly, in clinical trials (45, 47, 48). As shown by our results, drugs and drug combinations did not completely clear the infection, as a reduced but detectable number of intracellular parasites was observed after the treatment conclusion (Fig. 4). Thus, to evaluate whether these residual parasites were viable and capable of replicating, we monitored T. cruzi infection after drug removal. Parasite recrudescence occurred in all conditions (observed by the increase in the number of intracellular amastigotes and the presence of trypomastigotes in the supernatant), indicating that sterile cure was not achieved in any of the tested treatments. However, the superior efficacy of drug combinations was evident in suppressing trypomastigote release, compared to BZN monotherapy, especially at lower concentrations. Importantly, this result demonstrated that, by adding CQ, it was possible to reduce the concentration of BZN, maintaining the same trypanocidal effect. Moreover, the set of results from in vitro experiments revealed that the BZN+CQ combination yielded a high anti-T. cruzi potential (especially in comparison with compound performance alone), and the antiparasitic effect was consistent toward distinct parasite stages, diverse T. cruzi strains, a variety of infected cells, and different detection methodologies used, corroborating the robustness and efficacy of the proposed treatment.

The pattern of response to drug combinations was translated to the murine model of acute infection of the T. cruzi Colombian strain, which is resistant to BZN (35). The protocols of infection and treatment were chosen based on previously published studies (35, 49). The combination of 25 mg/kg/day BZN plus 50 mg/kg/day CQ significantly reduced the parasite burden, being 8-fold more effective than the same dosage of BZN administered alone. Furthermore, the superior effect of combined treatment was clearly demonstrated by a 6-fold higher effectiveness in reducing parasitemia under suboptimal dosages of drugs compared to the optimal dose of BZN administered alone (100 mg/kg/day). Thus, these findings confirm that the use of CQ potentiated the anti-T. cruzi effect of BZN, allowing a reduction in effective BZN dosage. Although the combinatory regimen was unable to promote sterile cure in infected animals, studies have shown that parasitic load reduction has a beneficial effect on T. cruzi infection outcome, mitigating the intensity of the inflammatory response and tissue damage (50–52), and thus, disease severity (53, 54).

CQ is an aminoquinoline derivative, first used for the prevention and therapy of malaria. It also acts as an anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis (55). Several mechanisms of action have been proposed to explain the therapeutic effects of CQ, including the inhibition of lysosomal activity (56) and autophagy (57), the modulation of signaling pathways such as Toll-like receptor signaling (58), and the reduction of anti-inflammatory cytokines production/release (59, 60). In the context of infection, in addition to host cell-targeting effects, CQ can also present an antiparasitic activity. In Plasmodium falciparum infection, CQ displays its antimalarial effect by inhibiting the conversion of toxic heme, a product from hemoglobin digestion, to hemozoin (61). For some viruses, such as HIV, Zika virus, and herpesvirus, CQ has been suggested to directly inhibit the viral DNA and RNA synthesis by binding to nucleic acids (61). Regarding T. cruzi infection, Ley and colleges have shown that the increase in the vacuolar pH with chloroquine significantly inhibited the escape of parasites from vacuoles to cytosol (62). More recently, it has been demonstrated that the alkalinization of intercellular pH influenced both parasite invasion as well as its escape into cytoplasm in HeLa and Vero cells (28). Considering that CQ has several described cellular targets and could be acting through various pathways, the mechanism relying on its inhibitory effect against T. cruzi should be further investigated.

In summary, this study demonstrates the potential of BZN in combination with CQ to treat Chagas disease. Their concomitant use potentiated the trypanocidal effect of BZN, resulting in lower doses needed to obtain an effective response. In clinical practice, it could represent a higher efficacy of treatment, with a lower possibility of infection relapses; additionally, a reduction in the frequent adverse effects of BZN is expected with diminished dosages. Importantly, regarding the safety profile of CQ, a short treatment time (e.g., some weeks) is not associated with serious adverse effects. This study also reinforces the relevance of exploring the approaches of drug combination and drug repurposing in the development of novel treatment options for Chagas disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drugs and chemicals.

The reference compound benznidazole (BZN) and the tested compounds chloroquine (CQ) and colchicine (COL) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Stock solutions were prepared by dissolving standardized powder in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for BZN and COL or in water for CQ. Stock solutions were stored at −20°C, protected from light and humidity.

Cell lines and parasites culture.

The human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T and the human monocytic cell line THP-1 were previously available at our laboratory. The Macaca mulatta kidney epithelial cell line LLC-MK2 and the human bone osteosarcoma epithelial cell line U2OS were generously donated by C. B. Moraes (Federal University of São Paulo, UNIFESP, São Paulo, Brazil). All cell lines were cultured in DMEM high-glucose culture medium (except THP-1, which was cultured in RPMI culture medium), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), in a humid atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Trypanosoma cruzi strains representing different biological and genotype discrete typing units (DTU) were employed. The Y strain (TcII) was kindly provided by S. Schenkman (Federal University of São Paulo, UNIFESP, São Paulo, Brazil), and the Colombiana strain (TcI) came from the strain repository from a member of the team (B. Zingales, University of São Paulo, USP, São Paulo, Brazil). Trypomastigotes were harvested from the supernatant of LLC-MK2 cells infected with T. cruzi. Infected cells were maintained in DMEM high-glucose medium, supplemented with 10% FBS, at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

Cytotoxicity assays.

Cytotoxicity of BZN, CQ, and COL and drug combinations were measured by the Tetrazolium- (MTT) method (63). Briefly, exponentially growing cells were seeded at 5 × 103 cells/well in a 96-well microplate at a final volume of 200 μL and were exposed to serially diluted drugs (2-fold dilution, from 800 to 5 μM) and drug combinations (CQ and COL at 5 μM associated with variable BZN concentrations). After 72 h of incubation, 20 μL MTT (5 mg/mL) was added, and the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C followed by the addition of 150 μL DMSO to dissolve the formazan crystals. Optical density was measured at 540 nm by the Labsystems Multiskan MS spectrometer. Nontreated cells were used as a negative control and represented 100% viability.

Infection model—trypomastigote release assay.

A trypomastigote release assay was performed to evaluate the activity of drugs and drug combinations on T. cruzi infection. HEK293T and THP-1 cells were seeded in complete medium at 1 × 105 cells/well into 24-well plates. THP-1 cells were differentiated into macrophage-like cells using 50 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA). After 48 h, culture medium was replaced by medium containing trypomastigotes (Y or Colombiana strain) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 followed by adding drugs in dose-response format, previously diluted in culture medium, with the highest concentration at 100 μM. For drug combinations, CQ and COL at 5 μM were associated with variable concentrations of BZN (the same concentration range used for BZN alone). Cells were washed with medium supplemented with 2% FBS every other day followed by replacement of the supernatant with fresh complete media containing drugs. On the peak day of parasite release, viable trypomastigotes in the supernatant medium were counted under optical microscope. The relative number of parasites was calculated by dividing the number of parasites in treated wells by the number of parasites in nontreated infected controls.

Infection model assay—high content assay combined with trypomastigote release assay.

A high content assay (HCA) was performed to determine the activity of the drugs and drug combinations against T. cruzi intracellular amastigotes (47). U2OS cells were seeded on 96-well plates at a density of 1,000 cells/well. After 24 h, cultures were infected with trypomastigotes of the T. cruzi Y strain (MOI = 30), followed by the addition of compounds, in dose-response format. The range of tested concentrations was as follows: 400 μM to 20 nM for BZN and 80 μM to 4 nM for CQ. For drug combinations, CQ at 5 μM or 1 μM was associated with variable concentrations of BZN (400 μM to 20 nM). Infected cultures were incubated for 144 h, with the replacement of the supernatant by fresh media containing drugs every other day. At assay endpoint, viable trypomastigotes in the supernatant medium were counted as described above and cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS and proceeded to immunofluorescence. Briefly, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 min followed by blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min. Cells were incubated with anti-T. cruzi polyclonal antibody (nonpurified sera obtained from infected mice), diluted 1:800 for 1 h, and then stained with secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (anti-mouse IgG, 1:1,200, 1 h at room temperature). Host cells and parasites nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 at a final concentration of 2 μg/mL.

Images from plates were obtained using an ImageXpress high content microscope (Molecular Devices) at ×20 magnification and then analyzed using a Columbus high-content analysis system (Perkin Elmer) to determine quantitative parameters, such as number of host cells, ratio of infected cells to total cell number in a well (infection ratio), mean number of intracellular parasites, and mean parasite area.

The infection index, calculated by infection ratio × mean parasite number, was normalized to both negative (nontreated infected cells) and positive controls (mock-infected cells) to determine the normalized anti-T. cruzi activity, expressed as a percentage compared to control wells. The cell ratio was defined as the ratio of cell numbers in compound-treated wells to the cell numbers in infected control wells.

Washout assay.

LLC-MK2 cells were seeded in two 96-well plates at a density of 500 cells/well (in 120 μL of culture media). After 24 h, trypomastigotes of the T. cruzi Y strain were added to the plates using an MOI of 10 (in 30 μL). Right after the infection, cultures were treated with drugs in a dose-response format as described above. After 48 and 96 h postinfection, culture supernatant was removed and fresh media containing drugs was added, totaling 3 cycles of treatment. One plate was fixed with 4% PFA right after the end of the treatment (144 h postinfection and first treatment). Another plate was extensively washed to ensure the complete drug removal and was maintained for an additional period of 7 days, with culture medium replacement every alternate day. After this period, plates were fixed with 4% PFA. To verify the presence of intracellular amastigotes, plates were submitted to immunofluorescence and high-content imaging as described above. The relative parasite load was calculated by dividing the parasites area in treated wells by the parasites area in nontreated infected controls.

Additionally, before cell fixation, the supernatant of plate cultures was collected, and viable parasites were counted under an optical microscope. The relative number of parasites was calculated as described above.

Trypomastigote assay.

To determine the activity of drugs and drug combinations against T. cruzi trypomastigotes, stock solutions of drugs were diluted in culture medium and placed in 96-well plates, with concentrations ranging from 200 to 0.4 μM for BZN and 80 to 0.2 μM for CQ. Trypomastigotes harvested from LLC-MK2 cells were seeded at 1 × 106 parasites/well (200-μL final volume) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The viability of trypomastigotes was determined by MTT-based assay as described above. Wells containing trypomastigotes treated with 1% DMSO were used as controls.

In vitro drug interactions.

The drug interaction between BZN and CQ was evaluated by a modified isobologram protocol (31–33). Briefly, dose-response curves at 2-fold dilutions were performed for different drug combinations (EC50 ratios, 5:0, 4:1, 3:2, 2:3, 1:4, and 0:5), and for each ratio, EC50 values were calculated for each drug in the combination. Fractional inhibitory concentrations (FIC50) were calculated as the EC50 of drug in combination divided by the EC50 of drug alone. The sum of FIC50 (∑FIC50) was determined as FIC50 BZN plus FIC50 CQ, and the mean (x∑FIC50) was calculated as the average of ∑FIC50. Isobologram was constructed by plotting FIC values of each drug ratio. The x∑FIC50 was used to characterize the mode of interaction following the Odds method (34) as follows: synergy for x∑ FIC50 ≤ 0.5, additive interaction for x∑ FIC50 > 0.5 to 4, and antagonism for x∑ FIC50 > 4.

In vivo efficacy assay.

Six- to eight-week-old female BALB/c mice were provided by the Institute of Science and Technology in Biomodels (ICTB) of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation and housed in the Experimental Animal Facility (CEA-CF/IOC unit). The experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Council for Animal Experimentation. The Animal Use Ethics Committee of Oswaldo Cruz Institute/Fiocruz approved all procedures performed in this study (license L006/2018). Mice were randomly arranged into groups of 3 to 5 animals and placed in a polypropylene cage lined with pine sawdust and enriched with an igloo, kept in microisolators, and received water and grain-based feed ad libitum. Upon arrival at the Experimental Animal Facility, the animals remained unhandled in the cages for 15 days to facilitate adaptation to the new environment. The environmental conditions were controlled with temperatures of 22 ± 2°C and a 12-h cycle of light and dark. The animals (n = 7/group) were inoculated intraperitoneally with 5,000 blood trypomastigote forms of the T. cruzi Colombian strain (TcI), obtained from serial passages in infected mice. As a control, animals were inoculated with vehicle solution. Infected mice were divided into 5 groups as follows: BZN optimal dose (100 mg/kg/day); BZN suboptimal dose (25 mg/kg/day), previously shown to be partially effective against Colombian infection (35); CQ (50 mg/kg/day); the combination of BZN (25 mg/kg/day) with CQ (50 mg/kg/day); and vehicle, apyrogenic vaccine-graded water (BioManguinhos, Fiocruz). Drug treatment by gavage started 10 days after infection and lasted for 20 consecutive days when the animals were euthanized. As previously described (35) parasitemia was evaluated every 5 days, starting right after the first day of treatment (10 dpi) and continuing up to assay endpoint (30 dpi), by examining 5 μL of blood collected from the tail vein under optical microscope.

Statistical analysis.

All data were processed using the GraphPad Prism software, version 8, and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least two independent experiments. Different data sets were analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. Dose-response curves were generated using a sigmoidal dose-response (variable slope) function, and the EC50 (compound concentration related to 50% antiparasitic activity) and CC50 (compound concentration related to 50% cell ratio) values were determined by interpolation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa de São Paulo - FAPESP (16/15209-0). E.C.-N. and B.Z. received a productivity award from Brazilian Council for Research - CNPq (304620/20165 and 304891/2019-3). R.P.P. was funded by FAPESP (2014/50708-2), L.A. was funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – CAPES (88887.353390/2019-00), and C.H.F. was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq (141635/2014-2). J.L.-V. is sponsored by CNPq (BPP 306037/2019-0) and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro/FAPERJ (E-26/202.572/2019).

We declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Laura Alcântara, Email: lauramalcantara@outlook.com.

Edecio Cunha-Neto, Email: edecunha@usp.br.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2022. Chagas disease (also known as American trypanosomiasis). World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee BY, Bacon KM, Bottazzi ME, Hotez PJ. 2013. Global economic burden of Chagas disease: a computational simulation model. Lancet Infect Dis 13:342–348. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kratz JM. 2019. Drug discovery for chagas disease: a viewpoint. Acta Trop 198:105107. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.105107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lidani KCF, Andrade FA, Bavia L, Damasceno FS, Beltrame MH, Messias-Reason IJ, Sandri TL. 2019. Chagas disease: from discovery to a worldwide health problem. Front Public Heal 7:166. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbosa AP, Cardinalli-Neto A, Otaviano AP, da Rocha BF, Bestetti RB. 2011. Comparison of outcome between Chagas cardiomyopathy and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Arq Bras Cardiol 97:517–525. 10.1590/S0066-782X2011005000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sales PA, Molina I, Murta SMF, Sánchez-Montalvá A, Salvador F, Corrêa-Oliveira R, Carneiro CM. 2017. Experimental and clinical treatment of Chagas disease: a review. Am J Trop Med Hyg 97:1289–1303. 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morillo CA, Marin-Neto JA, Avezum A, Sosa-Estani S, Rassi A, Rosas F, Villena E, Quiroz R, Bonilla R, Britto C, Guhl F, Velazquez E, Bonilla L, Meeks B, Rao-Melacini P, Pogue J, Mattos A, Lazdins J, Rassi A, Connolly SJ, Yusuf S. 2015. Randomized trial of benznidazole for chronic Chagas’ cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 373:1295–1306. 10.1056/NEJMoa1507574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Müller Kratz J, Garcia Bournissen F, Forsyth CJ, Sosa-Estani S. 2018. Clinical and pharmacological profile of benznidazole for treatment of Chagas disease. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 11:943–957. 10.1080/17512433.2018.1509704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatelain E. 2017. Chagas disease research and development: is there light at the end of the tunnel? Comput Struct Biotechnol J 15:98–103. 10.1016/j.csbj.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torrico F, Gascon J, Ortiz L, Alonso-Vega C, Pinazo MJ, Schijman A, Almeida IC, Alves F, Strub-Wourgaft N, Ribeiro I, Santina G, Blum B, Correia E, Garcia-Bournisen F, Vaillant M, Morales JR, Pinto Rocha JJ, Rojas Delgadillo G, Magne Anzoleaga HR, Mendoza N, Quechover RC, Caballero MYE, Lozano Beltran DF, Zalabar AM, Rojas Panozo L, Palacios Lopez A, Torrico Terceros D, Fernandez Galvez VA, Cardozo L, Cuellar G, Vasco Arenas RN, Gonzales I, Hoyos Delfin CF, Garcia L, Parrado R, de la Barra A, Montano N, Villarroel S, Duffy T, Bisio M, Ramirez JC, Duncanson F, Everson M, Daniels A, Asada M, Cox E, Wesche D, Diderichsen PM, Marques AF, Izquierdo L, et al. 2018. Treatment of adult chronic indeterminate Chagas disease with benznidazole and three E1224 dosing regimens: a proof-of-concept, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 18:419–430. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molina I, Gómez i Prat J, Salvador F, Treviño B, Sulleiro E, Serre N, Pou D, Roure S, Cabezos J, Valerio L, Blanco-Grau A, Sánchez-Montalvá A, Vidal X, Pahissa A. 2014. Randomized trial of posaconazole and benznidazole for chronic Chagas’ disease. N Engl J Med 370:1899–1908. 10.1056/NEJMoa1313122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morillo CA, Waskin H, Sosa-Estani S, del Carmen Bangher M, Cuneo C, Milesi R, Mallagray M, Apt W, Beloscar J, Gascon J, Molina I, Echeverria LE, Colombo H, Perez-Molina JA, Wyss F, Meeks B, Bonilla LR, Gao P, Wei B, McCarthy M, Yusuf S, Diaz R, Acquatella H, Lazzari J, Roberts R, Traina M, Taylor A, Holadyk-Gris I, Whalen L, Bangher MC, Romero MA, Prado N, Hernández Y, Fernandez M, Riarte A, Scollo K, Lopez-Albizu C, Gutiérrez NC, Berli MA, Cáceres NE, Petrucci JM, Prado A, Zulantay I, Isaza D, Reyes E, Figueroa A, Guzmán Melgar I, Rodríguez E, Aldasoro E, Posada EJ, et al. 2017. Benznidazole and posaconazole in eliminating parasites in asymptomatic T. cruzi carriers: the STOP-CHAGAS trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 69:939–947. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molina-Morant D, Fernández ML, Bosch-Nicolau P, Sulleiro E, Bangher M, Salvador F, Sanchez-Montalva A, Ribeiro ALP, De Paula AMB, Eloi S, Correa-Oliveira R, Villar JC, Sosa-Estani S, Molina I. 2020. Efficacy and safety assessment of different dosage of benznidazol for the treatment of Chagas disease in chronic phase in adults (MULTIBENZ study): study protocol for a multicenter randomized phase II non-inferiority clinical trial. Trials 21:328. 10.1186/s13063-020-4226-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pérez-Molina JA, Pérez-Ayala A, Moreno S, Fernández-González MC, Zamora J, López-Velez R. 2009. Use of benznidazole to treat chronic Chagas’ disease: a systematic review with a meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 64:1139–1147. 10.1093/jac/dkp357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sosa-Estani S, Segura EL. 2006. Etiological treatment in patients infected by Trypanosoma cruzi: experiences in Argentina. Curr Opin Infect Dis 19:583–587. 10.1097/01.qco.0000247592.21295.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida N. 2006. Molecular basis of mammalian cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi. An Acad Bras Cienc 78:87–111. 10.1590/s0001-37652006000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burleigh BA. 2005. Host cell signaling and Trypanosoma cruzi invasion: do all roads lead to lysosomes? Sci STKE 2005:pe36. 10.1126/stke.2932005pe36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Souza W, De Carvalho TMU, Barrias ES. 2010. Review on Trypanosoma cruzi: host cell interaction. Int J Cell Biol 2010:295394. 10.1155/2010/295394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira LRP, Ferreira FM, Laugier L, Cabantous S, Navarro IC, Da Silva Cândido D, Rigaud VC, Real JM, Pereira GV, Pereira IR, Ruivo L, Pandey RP, Savoia M, Kalil J, Lannes-Vieira J, Nakaya H, Chevillard C, Cunha-Neto E. 2017. Integration of miRNA and gene expression profiles suggest a role for miRNAs in the pathobiological processes of acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Sci Rep 7:17990. 10.1038/s41598-017-18080-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manque PA, Probst CM, Probst C, Pereira MCS, Rampazzo RCP, Ozaki LS, Ozaki LS, Pavoni DP, Silva Neto DT, Carvalho MR, Xu P, Serrano MG, Alves JMP, Meirelles MdNSL, Goldenberg S, Krieger MA, Buck GA. 2011. Trypanosoma cruzi infection induces a global host cell response in Cardiomyocytes. Infect Immun 79:1855–1862. 10.1128/IAI.00643-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei L, Adderley J, Leroy D, Drewry DH, Wilson DW, Kaushansky A, Doerig C. 2021. Host-directed therapy, an untapped opportunity for antimalarial intervention. Cell Rep Med 2:100423. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufmann SHE, Dorhoi A, Hotchkiss RS, Bartenschlager R. 2018. Host-directed therapies for bacterial and viral infections. Nat Rev Drug Discov 17:35–56. 10.1038/nrd.2017.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parihar SP, Guler R, Khutlang R, Lang DM, Hurdayal R, Mhlanga MM, Suzuki H, Marais AD, Brombacher F. 2014. Statin therapy reduces the Mycobacterium tuberculosis burden in human macrophages and in mice by enhancing autophagy and phagosome maturation. J Infect Dis 209:754–763. 10.1093/infdis/jit550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishnan MN, Garcia-Blanco MA. 2014. Targeting host factors to treat West Nile and dengue viral infections. Viruses 6:683–708. 10.3390/v6020683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schor S, Einav S. 2018. Combating intracellular pathogens with repurposed host-targeted drugs. ACS Infect Dis 4:88–92. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leung YY, Yao Hui LL, Kraus VB. 2015. Colchicine—update on mechanisms of action and therapeutic uses. Semin Arthritis Rheum 45:341–350. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodríguez A, Samoff E, Rioult MG, Chung A, Andrews NW. 1996. Host cell invasion by trypanosomes requires lysosomes andmicrotubule/kinesin-mediated transport. J Cell Biol 134:349–362. 10.1083/jcb.134.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stecconi-Silva RB, Andreoli WK, Mortara RA. 2003. Parameters affecting cellular invasion and escape from the parasitophorous vacuole by different infective forms of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 98:953–958. 10.1590/s0074-02762003000700016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Filardi LS, Brener Z. 1987. Susceptibility and natural resistance of Trypanosoma cruzi strains to drugs used clinically in Chagas disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 81:755–759. 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franco CH, Alcântara LM, Chatelain E, Freitas-Junior L, Moraes CB. 2019. Drug discovery for Chagas disease: impact of different host cell lines on assay performance and hit compound selection. Trop Med Infect Dis 4:82. 10.3390/tropicalmed4020082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fivelman QL, Adagu IS, Warhurst DC. 2004. Modified fixed-ratio isobologram method for studying in vitro interactions between atovaquone and proguanil or dihydroartemisinin against drug-resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:4097–4102. 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4097-4102.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reimão JQ, Mesquita JT, Ferreira DD, Tempone AG. 2016. Investigation of calcium channel blockers as antiprotozoal agents and their interference in the metabolism of Leishmania (L.) infantum. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med 2016:1523691. 10.1155/2016/1523691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Figueiredo Diniz L, Mazzeti AL, Caldas IS, Ribeiro I, Bahia MT. 2018. Outcome of E1224-Benznidazole combination treatment for infection with a multidrug-resistant trypanosoma cruzi strain in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e00401-18. 10.1128/AAC.00401-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Odds FC. 2003. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J Antimicrob Chemother 52:1. 10.1093/jac/dkg301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vilar-Pereira G, Resende Pereira I, De Souza Ruivo LA, Cruz Moreira O, Da Silva AA, Britto C, Lannes-Vieira J. 2016. Combination chemotherapy with suboptimal doses of benznidazole and pentoxifylline sustains partial reversion of experimental Chagas’ heart disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:4297–4309. 10.1128/AAC.02123-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore BR, Page-Sharp M, Stoney JR, Ilett KF, Jago JD, Batty KT. 2011. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and allometric scaling of chloroquine in a murine malaria model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3899–3907. 10.1128/AAC.00067-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Álvarez MG, Ramírez JC, Bertocchi G, Fernández M, Hernández Y, Lococo B, Lopez-Albizu C, Schijman A, Cura C, Abril M, Laucella S, Tarleton RL, Natale MA, Eiro MC, Sosa-Estani S, Viotti R. 2020. New scheme of intermittent benznidazole administration in patients chronically infected with Trypanosoma cruzi: clinical, parasitological, and serological assessment after three years of follow-up. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e00439-20. 10.1128/AAC.00439-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torrico F, Gascón J, Barreira F, Blum B, Almeida IC, Alonso-Vega C, Barboza T, Bilbe G, Correia E, Garcia W, Ortiz L, Parrado R, Ramirez JC, Ribeiro I, Strub-Wourgaft N, Vaillant M, Sosa-Estani S, Arteaga R, de la Barra A, Camacho Borja J, Martinez I, Fernandes J, Garcia L, Lozano D, Palacios A, Schijman A, Pinazo MJ, Pinto J, Rojas G, Estevao I, Ortega-Rodriguez U, Mendes MT, Schuck E, Hata K, Maki N, Asada M. 2021. New regimens of benznidazole monotherapy and in combination with fosravuconazole for treatment of Chagas disease (BENDITA): a phase 2, double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis 21:1129–1140. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30844-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cafferata ML, Toscani MA, Althabe F, Belizán JM, Bergel E, Berrueta M, Capparelli EV, Ciganda Á, Danesi E, Dumonteil E, Gibbons L, Gulayin PE, Herrera C, Momper JD, Rossi S, Shaffer JG, Schijman AG, Sosa-Estani S, Stella CB, Klein K, Buekens P. 2020. Short-course benznidazole treatment to reduce trypanosoma cruzi parasitic load in women of reproductive age (BETTY): a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial study protocol. Reprod Health 17:128. 10.1186/s12978-020-00972-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alcântara LM, Ferreira TCS, Gadelha FR, Miguel DC. 2018. Challenges in drug discovery targeting TriTryp diseases with an emphasis on leishmaniasis. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 8: 430–439. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Field MC, Horn D, Fairlamb AH, Ferguson MAJ, Gray DW, Read KD, De Rycker M, Torrie LS, Wyatt PG, Wyllie S, Gilbert IH. 2017. Anti-trypanosomatid drug discovery: an ongoing challenge and a continuing need. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:217–231. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zingales B, Miles MA, Moraes CB, Luquetti A, Guhl F, Schijman AG, Ribeiro I, Chagas Clinical Research Platform Meeting . 2014. Drug discovery for Chagas disease should consider Trypanosoma cruzi strain diversity. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 109:828–833. 10.1590/0074-0276140156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engel JC, Ang KKH, Chen S, Arkin MR, McKerrow JH, Doyle PS. 2010. Image-based high-throughput drug screening targeting the intracellular stage of Trypanosoma cruzi, the agent of Chagas’ disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3326–3334. 10.1128/AAC.01777-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Portella DCN, Rossi EA, Paredes BD, Bastos TM, Meira CS, Nonaka CVK, Silva DN, Improta-Caria A, Moreira DRM, Leite ACL, De Oliveira Filho GB, Filho JMB, Dos Santos RR, Soares MBP, De Freita Souza BS. 2021. A novel high-content screening-based method for anti-Trypanosoma cruzi drug discovery using human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells Int 2021:2642807. 10.1155/2021/2642807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacLean LM, Thomas J, Lewis MD, Cotillo I, Gray DW, De Rycker M. 2018. Development of Trypanosoma cruzi in vitro assays to identify compounds suitable for progression in Chagas’ disease drug discovery. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12:e0006612. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sánchez-Valdéz FJ, Padilla A, Wang W, Orr D, Tarleton RL. 2018. Spontaneous dormancy protects Trypanosoma cruzi during extended drug exposure. Elife 7:e34039. 10.7554/eLife.34039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moraes CB, Giardini MA, Kim H, Franco CH, Araujo-Junior AM, Schenkman S, Chatelain E, Freitas-Junior LH. 2014. Nitroheterocyclic compounds are more efficacious than CYP51 inhibitors against Trypanosoma cruzi: implications for Chagas disease drug discovery and development. Sci Rep 4:4703. 10.1038/srep04703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cal M, Ioset JR, Fügi MA, Mäser P, Kaiser M. 2016. Assessing anti-T. cruzi candidates in vitro for sterile cidality. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 6:165–170. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romanha AJ, de Castro SL, de Soeiro MNC, Lannes-Vieira J, Ribeiro I, Talvani A, Bourdin B, Blum B, Olivieri B, Zani C, Spadafora C, Chiari E, Chatelain E, Chaves G, Calzada JE, Bustamante JM, Freitas-Junior LH, Romero LI, Bahia MT, Lotrowska M, Soares M, Andrade SG, Armstrong T, Degrave W, de Andrade ZA. 2010. In vitro and in vivo experimental models for drug screening and development for Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 105:233–238. 10.1590/s0074-02762010000200022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caldas S, Caldas IS, de Diniz LF, de Lima WG, de Oliveira RP, Cecílio AB, Ribeiro I, Talvani A, Bahia MT. 2012. Real-time PCR strategy for parasite quantification in blood and tissue samples of experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Acta Trop 123:170–177. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benvenuti LA, Roggério A, Freitas HFG, Mansur AJ, Fiorelli A, Higuchi ML. 2008. Chronic American trypanosomiasis: parasite persistence in endomyocardial biopsies is associated with high-grade myocarditis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 102:481–487. 10.1179/136485908X311740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bustamante JM, Rivarola HW, Fernández AR, Enders JE, Fretes R, Palma JA, Paglini-Oliva PA. 2002. Trypanosoma cruzi reinfections in mice determine the severity of cardiac damage. Int J Parasitol 32:889–896. 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lo Presti MS, Rivarola HW, Bustamante JM, Fernández AR, Enders JE, Fretes R, Gea S, Paglini-Oliva PA. 2004. Thioridazine treatment prevents cardiopathy in Trypanosoma cruzi infected mice. Int J Antimicrob Agents 23:634–636. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia S, Ramos CO, Senra JFV, Vilas-Boas F, Rodrigues MM, Campos-De-Carvalho AC, Ribeiro-Dos-Santos R, Soares MBP. 2005. Treatment with benznidazole during the chronic phase of experimental Chagas’ disease decreases cardiac alterations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:1521–1528. 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1521-1528.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schrezenmeier E, Dörner T. 2020. Mechanisms of action of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine: implications for rheumatology. Nat Rev Rheumatol 16:155–166. 10.1038/s41584-020-0372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Circu M, Cardelli J, Barr M, O’Byrne K, Mills G, El-Osta H. 2017. Modulating lysosomal function through lysosome membrane permeabilization or autophagy suppression restores sensitivity to cisplatin in refractory non-small-cell lung cancer cells. PLoS One 12:e0184922. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mauthe M, Orhon I, Rocchi C, Zhou X, Luhr M, Hijlkema KJ, Coppes RP, Engedal N, Mari M, Reggiori F. 2018. Chloroquine inhibits autophagic flux by decreasing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy 14:1435–1455. 10.1080/15548627.2018.1474314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kužnik A, Benčina M, Švajger U, Jeras M, Rozman B, Jerala R. 2011. Mechanism of endosomal TLR inhibition by antimalarial drugs and imidazoquinolines. J Immunol 186:4794–4804. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jang CH, Choi JH, Byun MS, Jue DM. 2006. Chloroquine inhibits production of TNF-alpha, IL-1beta and IL-6 from lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes/macrophages by different modes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45:703–710. 10.1093/rheumatology/kei282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karres I, Kremer JP, Dietl I, Steckholzer U, Jochum M, Ertel W. 1998. Chloroquine inhibits proinflammatory cytokine release into human whole blood. Am J Physiol 274:R1058-64. 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.4.R1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coban C. 2020. The host targeting effect of chloroquine in malaria. Curr Opin Immunol 66:98–107. 10.1016/j.coi.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ley V, Robbins ES, Nussenzweig V, Andrews NW. 1990. The exit of Trypanosoma cruzi from the phagosome is inhibited by raising the pH of acidic compartments. J Exp Med 171:401–413. 10.1084/jem.171.2.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mosmann T. 1983. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 65:55–63. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download aac.00284-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 9.1 MB (9.3MB, pdf)