Abstract

Traditional family planning research has excluded Black and Latinx leaders, and little is known about medication abortion (MA) among racial/ethnic minorities, although it is an increasingly vital reproductive health service, particularly after the fall of Roe v. Wade. Reproductive justice (RJ) community-based organisation (CBO) SisterLove led a study on Black and Latinx women’s MA perceptions and experiences in Georgia. From April 2019 to December 2020, we conducted key informant interviews with 20 abortion providers and CBO leaders and 32 in-depth interviews and 6 focus groups (n = 30) with Black and Latinx women. We analysed data thematically using a team-based, iterative approach of coding, memo-ing, and discussion. Participants described multilevel barriers to and strategies for MA access, wishing that “the process had a bit more humanity … [it] should be more holistic.” Barriers included (1) sociocultural factors (intersectional oppression, intersectional stigma, and medical experimentation); (2) national and state policies; (3) clinic- and provider-related factors (lack of diverse clinic staff, long waiting times); and (4) individual-level factors (lack of knowledge and social support). Suggested solutions included (1) social media campaigns and story-sharing; (2) RJ-based policy advocacy; (3) diversifying clinic staff, offering flexible scheduling and fees, community integration of abortion, and RJ abortion funds; and (4) social support (including abortion doulas) and comprehensive sex education. Findings suggest that equitable MA access for Black and Latinx communities in the post-Roe era will require multi-level intervention, informed by community-led evidence production; holistic, de-medicalised, and human rights-based care models; and intersectional RJ policy advocacy.

Keywords: medication abortion, reproductive justice, abortion barriers, racial/ethnic disparities, qualitative research, community-led research

Résumé

Jusqu’à présent, la recherche sur la planification familiale a exclu les responsables noirs et latino-américains, et on sait peu de choses sur l’avortement médicamenteux parmi les minorités raciales/ethniques, même s’il s’agit d’un service de santé reproductive de plus en plus essentiel, en particulier après la révocation de l’arrêt Roe v. Wade. SisterLove, une organisation communautaire travaillant sur la justice reproductive a dirigé une étude sur les conceptions et les expériences de femmes noires et latino-américaines sur l’avortement médicamenteux en Géorgie. D’avril 2019 à décembre 2020, nous avons mené des entretiens auprès d’informateurs clés avec 20 prestataires pratiquant l’avortement et dirigeants d’organisations communautaires ainsi que 32 entretiens approfondis et six groupes de discussion (n = 30) avec des femmes noires et latino-américaines. Nous avons analysé les données thématiquement à l’aide d’une approche itérative et collective de codage, de préparation de notes et de discussion. Les participants ont décrit des obstacles à plusieurs niveaux et des stratégies pour avoir accès à l’avortement médicamenteux, souhaitant que « le processus soit un peu plus humain » et qu’il soit « plus holistique ». Les obstacles comprenaient: (1) des facteurs socioculturels (oppression intersectionnelle, stigmatisation intersectionnelle et expérimentation médicale); (2) les politiques nationales et des États; (3) des facteurs se rapportant aux centres de santé et aux prestataires (manque de diversité du personnel des centres, longs délais d’attente); et (4) des facteurs de niveau individuel (manque de connaissances et de soutien social). Les solutions suggérées incluaient: (1) des campagnes dans les médias sociaux et le partage de témoignages; (2) un plaidoyer politique fondé sur la justice reproductive; (3) une diversification du personnel des centres de santé, pour proposer plus de souplesse dans les horaires et les tarifs, l’intégration communautaire de l’avortement et des fonds pour l’avortement dans le cadre de la justice reproductive; et (4) un soutien social (notamment des doulas accompagnant l’avortement) et une éducation sexuelle complète. Les conclusions semblent indiquer qu’un accès équitable des communautés noires et latino-américaines à l’avortement médicamenteux après la révocation de l’arrêt Roe v. Wade exigera des interventions à plusieurs niveaux, guidées par la production de données à assise communautaire; des modèles de soins holistiques, démédicalisés et fondés sur les droits de l’homme; et un plaidoyer politique intersectionnel dans le cadre de la justice reproductive.

Resumen

Las investigaciones tradicionales sobre planificación familiar han excluido a líderes negros y latinxs, y no se sabe mucho sobre el aborto con medicamentos (AM) entre minorías raciales/étnicas, a pesar de ser un servicio de salud reproductiva cada vez más vital, en particular después de la derogación de Roe c. Wade. SisterLove, organización comunitaria (OC) de justicia reproductiva (JR) lideró un estudio sobre las percepciones y experiencias de AM de mujeres negras y latinas en Georgia. Entre abril de 2019 y diciembre de 2020, realizamos entrevistas con informantes clave –20 prestadores de servicios de aborto y líderes de OC—, y 32 entrevistas a profundidad y 6 grupos focales (n = 30) con mujeres negras y latinas. Analizamos los datos por temática utilizando el enfoque iterativo de codificación, memorandos y debates basado en equipo. Los participantes describieron barreras de múltiples niveles y estrategias para el acceso al AM deseando que “el proceso tenga un poco más de humanidad … debería ser “más holístico”. Algunas barreras mencionadas fueron: (1) factores socioculturales (opresión interseccional, estigma interseccional y experimentación médica); (2) políticas nacionales y estatales; (3) factores relacionados con los centros de salud y prestadores de servicios (falta de personal clínico diverso, largos tiempos de espera); y (4) factores individuales (falta de conocimiento y apoyo social). Algunas soluciones sugeridas fueron: (1) campañas en redes sociales e intercambio de historias; (2) promoción y defensa de políticas basadas en JR; (3) diversificación del personal clínico, ofrecer horarios y honorarios flexibles, integración comunitaria del aborto y los fondos de JR para aborto; y (4) apoyo social (que incluye doulas que asisten con abortos) y educación sexual integral. Los hallazgos indican que el acceso equitativo al AM para comunidades negras y Latinas en la era post-Roe necesitará intervención de múltiples niveles, informada por la producción de evidencia liderada por la comunidad; modelos de atención holística, desmedicalizada y basada en los derechos humanos; y promoción y defensa de políticas de JR interseccionales.

Introduction

Medication abortion (MA) is an increasingly vital reproductive health service, particularly after the fall of Roe v. Wade, but there are major gaps in our understanding of access to, preferences for, experiences with, and utilisation of MA among racial/ethnic minorities in the US. One recent study by Wingo et al. found Black respondents were less likely than other racial groups to prefer MA over surgical abortion.1 A study of Ohio’s new policy restricting how providers can administer MA significantly reduced the likelihood that non-White patients could access the service.2 Teal and colleagues’ study focused on MA among low-income, non-English-speaking Latinas,* and they reported high acceptability (94% would recommend to a friend), safety, and efficacy although only 39% of eligible women chose MA over surgical abortion.3 Other studies suggest Latina and Black women† are more likely to use pills and other methods to self-manage their abortions as compared to White women.4,5 Researchers like Dehlendorf, Harris, and Weitz have described the paradox wherein women of colour have both higher abortion rates‡ and lower access to abortion care, carefully explaining that abortion in Black and Latina communities is contextualised by socioeconomic disadvantage, barriers to quality contraceptive care, and warranted mistrust of health providers.6,7 Beyond this, the evidence about racial/ethnic disparities in MA is very limited. This is an important gap, because access to medication abortion is a particularly vital reproductive health service for Black, Latinx, and other women of colour. Black and other women of color face higher risk of pregnancy-related complications, with three times the risk of maternal mortality compared to White women.8 Because Black and other women of colour face disproportionate barriers to clinic-based abortion care (including cost, transportation, childcare), MA and telemedicine for abortion are essential for connecting them to high-quality abortion care outside of the clinic setting.8,9 MA has become even more critical in the context of COVID-19, after the US Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson that overturned Roe v. Wade and federal abortion protections, and under highly-restrictive early abortion bans like Georgia’s, which is around 6 weeks’ gestation.10–14

Moreover, abortion research has seldom employed a reproductive justice (RJ) or community-engaged framework to understand and address pertinent questions regarding access to abortion for marginalised groups.15 This has led to a critical lack of Black and Latinx voices in the existing literature on abortion. Briefly, RJ can be defined as a social theory and community organising framework that promotes the human rights to have children, to not have children, and to parent one’s children with health and dignity free of reproductive oppression and coercion.16–19 Community-based participatory research (CBPR)18–20 is a type of community-engaged research that positions community members as equals or leaders in the research process from conceptualisation to dissemination and improves the relevance, usefulness, validity, replicability, and sustainability of research and interventions.21 CBPR is built on mutual partnership, respect, and trust between researchers and community members most affected by public health issues. CBPR is particularly important for understanding and addressing health inequities, because it centres people with marginalised experiences and empowers them through increased community capacity to study and resolve the issues they face. While CBPR has been applied across many public health topics, it is sorely lacking in family planning. This is especially problematic given the sensitive nature of family planning and reproductive injustices against communities of colour by family planning professionals.17,18,22,23 To address this glaring gap, our team centres Black and Latinx voices through all steps of the research process; this is crucial for the development of the sexual and reproductive health field and for improving reproductive health outcomes in Black and Latinx communities.

Led by our HIV and RJ organisation, SisterLove, in partnership with researchers from local academic universities, we conducted a community-engaged, qualitative study of MA among Black and Latinx communities in metro-Atlanta, Georgia.15,24 We explored Black and Latinx women’s perceptions of, experiences with, barriers to, and facilitators of MA to address the following research questions:

What are their understandings, attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions of MA?

How do they describe their MA experiences or experiences they have heard about?

What are the barriers and facilitators in accessing MA?

What are their recommendations for integrated approaches to MA care?

Materials and methods

Setting and approach

Metro-Atlanta, GA is an ideal setting given the state’s wide inequities in maternal and infant health,25 increasingly restrictive abortion policy climate,17,18,26,27 the metro area’s socio-demographic and rural-suburban-urban diversity,28 and the region’s strong RJ presence.29 Compared to other parts of the US, women in Georgia experience more barriers to contraception,30 obstetric care,31 abortion services,32 and have a higher burden of unintended pregnancy and birth.33,34 Georgia also has the country’s highest maternal mortality rate (28.7 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2011) with Black women at four times the risk of White women,35 and a higher-than-average infant mortality (6.98 per 1,000 live births in 2013), with Black infants twice as likely to die as White infants.36 Moreover, the state’s deportation rate is the highest nationally,37 and Latinx women across the US experience disproportionate and unique barriers to reproductive health care including immigration enforcement, sociocultural stigma, lack of insurance, and language barriers.38,39

Using CBPR and RJ principles, all research activities were conducted with guidance and oversight from the study’s Community Advisory Board, including abortion clinics and advocacy groups, community-based organisations (CBO) serving Black and Latinx communities, faith leaders, and researchers as well as Black and Latinx women from metro-Atlanta.15 The Community Advisory Board helped develop data collection instruments, advised on recruitment strategies, discussed findings, and participated in dissemination as co-presenters at conferences and co-authors of manuscripts. The study team was majority Black and Latinx and approximately half bilingual (Spanish and English). The primary researcher at SisterLove and the Project Director were both Black Latinx women living in metro-Atlanta, who were personally familiar with the Black and Latinx communities this study focuses on. The primary academic researcher was a White woman living in metro-Atlanta and a native of Georgia, who has 12 years of post-graduate experience in community-engaged research with Black and Latinx communities. Student researchers worked directly at SisterLove and came from Black, Latinx, and/or immigrant communities living in metro-Atlanta. All study activities were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Emory University (IRB 00107733) in January 2019.

Recruitment and sample

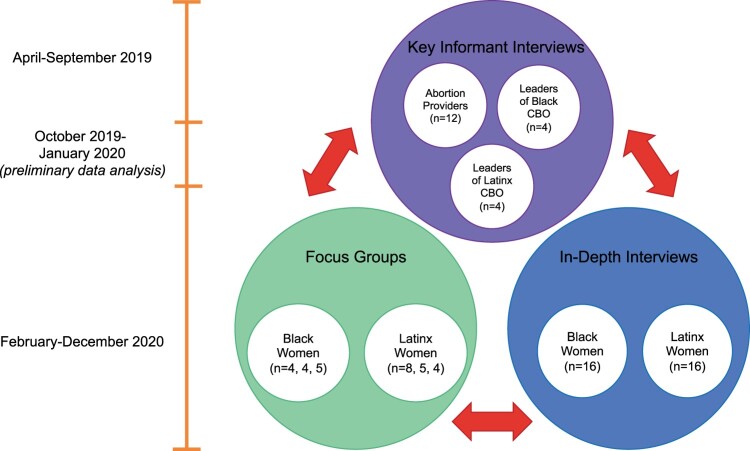

Data were collected from April 2019 to December 2020, starting immediately after Georgia’s early abortion ban (based on fetal cardiac activity, which typically begins at 6 weeks gestation) but before it was enacted, which did not occur until July 2022.14 From April to September 2019, we conducted 20 semi-structured key informant interviews with abortion providers and leaders of CBOs serving Black and Latinx communities in metro-Atlanta (see Figure 1). We defined key informants as abortion providers – who could provide clinical perspectives about their Black and Latinx patients’ abortion care – and leaders of Black and Latinx CBOs, who could provide insight about the social context of Black and Latinx abortion patients as well as examples of how CBOs provide (or do not provide) abortion education and referrals. Notably, many leaders of Black and Latinx organisations are also Black and Latinx women, with their own personal perspectives of and experiences with MA. Key informants were recruited by email from local abortion clinics, from partnering CBOs, and through our Community Advisory Board. From February to December 2020, we then conducted 16 in-depth interviews with Black women, 16 in-depth interviews with Latinx women, 3 focus groups with Black women (n = 4, 4, and 5), and 3 focus groups with Latinx women (n = 8, 5, and 4). We sought to recruit a diverse group of Black and Latinx women for in-depth interviews and focus groups, with varying perspectives across educational and economic background, age, and geographic location in the metro-area. This would ensure diverse perspectives on MA within the heterogeneous Black and Latinx communities in metro-Atlanta. Therefore, interview and focus group participants were recruited through abortion clinics, CBOs, social media, radio advertising, and flyers in community settings (e.g. hair and nail salons, centres of commerce, university student lounges). In-depth interviews provided the opportunity for women to discuss sensitive personal topics, and the focus group demonstrated how Black and Latinx women discuss abortion in safe but public settings. We gathered and triangulated data from these three sources in order to formulate a more comprehensive narrative of the experiences and perceptions of MA care. All participants provided verbal consent and received a $30 gift card for participation.

Figure 1.

Triangulation of data sources from key informant interviews with abortion providers (n = 12) and leaders of Black (n = 4) and Latinx (n = 4) community-based organisations, in-depth interviews with Black (n = 16) and Latinx (n = 16) women, and focus groups with Black (n = 4, 4, 5) and Latinx (n = 8, 5, 4) women in metro-Atlanta

Semi-structured interview guides, semi-structured focus group guides, and a close-ended demographic survey were initially developed by the core SisterLove and Emory researchers. Questions were drafted based on RJ; for example, by considering intersectionality, contextualising in historical and ongoing racial oppression, and emphasising structural inequalities. The team also relied on public health theory including the socio-ecological model40 that posits factors across levels of the social ecology (socio-cultural, policy, institutions, and individual) interact and influence health behaviour and outcomes. Finally, some questions were developed based on the integrated behaviour model,41 which emphasises the importance of knowledge, attitudes, norms, and access as determinants of health behaviour and outcomes. The drafted guides and survey were then shared iteratively with the Community Advisory Board, who assisted in editing and refining the tools until the Board unanimously approved.

All recruitment, data collection, and data analyses were conducted by the SisterLove team, including Master's level student researchers working at SisterLove. Ongoing training in qualitative research methods, interview and focus group techniques, and qualitative analysis was provided by the primary academic researcher. Interviews and focus groups lasted approximately one hour (see Appendix A for the guides). All were transcribed and translated to English from Spanish if needed. Transcripts were analysed in Dedoose42 using the Sort, Sift, Think, Shift43 protocol. This protocol incorporates multiple approaches from traditional qualitative methods like grounded theory, phenomenology, and narrative analysis. First, each transcript was read carefully by a SisterLove student researcher, who then wrote a summary memo, annotated emerging topics, and identified key quotations. Collectively, the emerging topics were compiled by the primary academic researcher into a preliminary codebook, which was then discussed, edited, and agreed upon by the SisterLove team. This codebook was then used by the SisterLove student researchers to horizontally code across all interviews. Each code was assigned to two student coders, who reconciled to reach 100% inter-coder agreement. When there was disagreement between coders that could not be resolved within the dyad, the disagreement was raised at regular team meetings, where the SisterLove project director and primary academic researcher facilitated a larger conversation. Final decisions on coding were left to SisterLove’s discretion. After coding, the primary researcher led theme development through an iterative process of deeper analysis of the codes (e.g. code co-occurrence, frequency of code use, group differences), memo-ing, diagramming, and group conversation with the team and the Community Advisory Board. The team compared results from the key informant interviews, in-depth interviews, and focus groups in order to triangulate findings and to understand how MA norms and discussion vary from private to group settings.

Finally, the team also practiced careful reflexivity throughout the study. In addition to being taught and allowed to practice reflexivity during qualitative methods training, researchers conducting interviews were prompted after the interview using a debrief guide to identify (1) how their own identities and life experiences influenced the interview dynamic, (2) what assumptions and beliefs they brought to the interview, and (3) what emotions they felt during and after the interview. During weekly team meetings, researchers conducting interviews and analysing data discussed reflexivity. Notably, White researchers on the team were supported to identify and address their own biases through support from Black and Latinx leaders on the team.

Results

Our key informant sample was diverse by race/ethnicity (40% Black/African American, 40% Latinx, 35% White, 15% Asian/Pacific Islander), although most key informants were highly educated (80% graduated college or had a graduate or professional degree). The in-depth interviews and focus groups were stratified by Black/African American and Latinx, as reflected in 50% of in-depth interview participants who were Black and 50% who were Latinx, 50% of focus group participants who were Black, and 57% Latinx. The majority (69%) of in-depth interview participants and focus group participants (57%) had graduated college or had a graduate degree, and they were mostly employed (72%, 80%). In-depth interview and focus group participants were highly religious with 88% and 73% identifying with Christianity or another religion, respectively. They were also more likely to be single and never married (72%, 57%) than married, separated, or divorced. Half (50%) of the in-depth interview participants lived at less than 200% of the federal poverty level, but only 17% of focus group participants did. On average, key informants were 36 years old, in-depth interview participants were 29, and focus group participants were 31. See more sample demographics in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographics of the study sample consisting of abortion providers, CBO leaders, Black women, and Latinx women in metro-Atlanta

| Demographic Variable | Key Informant Interviews (n = 20) |

In-Depth Interviews (n = 32) |

Focus Groups (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Woman | 90% (18) | 100% (32) | 100% (30) |

| Man | 5% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Other | 5% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Race | |||

| Black/African American | 40% (8) | 50.0% (16) | 50% (15) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 15% (3) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0% (0) | 3.1% (1) | 0% (0) |

| Biracial or Multiracial | 0% (0) | 12.6% (4) | 6.7% (2) |

| White | 35% (7) | 12.5% (4) | 16.7% (5) |

| Other | 0% (0) | 15.6% (5) | 20% (6) |

| Prefer Not to Answer | 10% (2) | 6.3% (2) | 3.3% (1) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Latinx | 40% (8) | 50.0% (16) | 56.7% (17) |

| Not Latinx | 60% (12) | 50.0% (16) | 43.3% (13) |

| Age: Mean (SD) | 36.3 (10.46) | 29.3 (6.8) | 31 (7.8) |

| Educational Level | |||

| Some High School | 5% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Graduated High School | 10% (2) | 6.3% (2) | 6.7% (2) |

| Vocational training | 0% (0) | 3.1% (1) | 3.3% (1) |

| Some College | 5% (1) | 21.9% (7) | 23.3% (7) |

| Professional Degree | 15% (3) | 0% (0) | 3.3% (1) |

| Graduated College | 30% (6) | 43.8% (14) | 43.3% (13) |

| Graduate Degree | 35% (7) | 25% (8) | 13.3% (4) |

| Key Informant Type | |||

| Leader of Black CBO | 20% (4) | – | – |

| Leader of Latinx CBO | 20% (4) | – | – |

| Abortion Provider | 60% (12) | – | – |

| Religious Denomination | |||

| Non-Evangelical Protestant Christian/Other Christian | – | 43.8% (14) | 43.3% (13) |

| Catholic | – | 28.2% (9) | 16.7% (5) |

| Evangelical Protestant Christian | – | 6.3% (2) | 13.3% (4) |

| Other Religion | – | 9.4% (3) | 0% (0) |

| Do Not Affiliate With Any Religion | – | 12.5% (4) | 26.7% (8) |

| Annual Household Income/Household Size | |||

| <200% federal poverty level | – | 50.0% (16) | 16.7% (5) |

| 200% federal poverty level or more | – | 40.6% (13) | 76.7% (23) |

| Did not report income | – | 3.1% (1) | 6.7% (2) |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed | – | 71.9% (23) | 80% (24) |

| Unemployed | – | 28.1% (9) | 20% (6) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | – | 12.5% (4) | 36.7% (11) |

| Separated/Divorced | – | 15.62% (5) | 6.7% (2) |

| Single, Never Married | – | 71.9% (23) | 56.7% (17) |

| Political Identity | |||

| Left/Liberal | – | 59.4% (19) | 50% (15) |

| Moderate | – | 12.5% (4) | 16.7% (5) |

| Right/Conservative | – | 9.4% (3) | 0% (0) |

| Do Not Affiliate With Any Political Group | – | 9.4% (3) | 23.3% (7) |

| Prefer Not to Answer | – | 6.3% (2) | 10% (3) |

We identified four themes across our participants’ multiple levels of their social ecology, which account for barriers to and intervention strategies for MA among Black and Latinx women (see Figure 2): (1) intersectional oppression, intersectional stigma, and medical research exploitation of Black and Latinx communities create socio-cultural barriers to MA for racial/ethnic minorities; (2) national, state, and institutional policies disproportionately reduce MA accessibility for marginalised groups; (3) clinic- and provider-levels factors inadvertently decentre patients during abortion services and create unnecessary barriers to MA for Black and Latinx communities; and (4) barriers at higher levels of the socio-ecological model come to bear at the individual level, where Black and Latinx women shoulder disproportionate barriers to MA.

Figure 2.

Barriers to and intervention strategies for medication abortion among Black and Latinx women in Georgia across the socio-ecological model

Socio-cultural context and solutions

Socio-cultural barriers

First, intersectional oppression, intersectional stigma, and intersectional medical research exploitation of Black and Latinx communities created systematic barriers to MA for racial/ethnic minorities at the socio-cultural level. Participants repeatedly and consistently emphasised how Black and Latinx women’s barriers to MA are complex precisely because Black and Latinx women face gender, racial, ethnic, immigration, and economic disadvantage all at once. As one abortion provider,§ Sarah,** explained, “Basically all the things that make life harder for Black people in this country will be playing into why accessing abortion is harder for them.” Participants described how stigma intersected with various identities to impact their MA experience. Black and Latinx women must face not only abortion stigma, but also the additional layers of stigma attached to their race, sexuality, gender, socioeconomic level, and other experiences:

“[Someone who has an abortion] would be judged sadly … my tías [my aunts] … are very religious … they would just be so quick to judge like me or my sister and be like ‘They’re hoes’ like ‘They got an abortion because they’re sleeping around and not even taking care of themselves’ … if it was my situation I think my tías … they wouldn’t judge me because compared to my other cousins – they never like went to college, didn’t graduate … I think they’d be more forgiving, but if it was like one of my cousins who like didn’t graduate or still has a part-time job at like a retail then they’d be more judgmental … ‘Oh you know, well, she’s this type of girl, and what did you expect.’ … I think it would be harder for minorities like Blacks and Latinos … we have to think about like the culture and there’s already like so much stigma about like the welfare queen and all these other things that they would make it so much harder … I mean we can’t even access birth control easily, so imagine like an abortion pill. Especially for Black and Latina women that are predominantly in low-income working class like they think it’s harder, they think it’s more expensive, there’d be so much stigma around it … ” (Angelica, 26-year-old Latinx woman)

Another example of intersectional systematic disadvantage described by participants was medical and research exploitation of Black and Latinx communities. Abortion providers, CBO leaders, Black women, and Latinx women alike referenced the “experimentation … [like] Tuskegee” and birth control pill trials in Black and Latinx communities and how this builds mistrust against MA and its safety. Notably, some participants made distinctions between the mistrust in Black communities and Latinx communities. One abortion provider, Elena, explained that the majority of Black women choose surgical abortion while Latinx women prefer MA:

“Looking at the black perspective, I will say the majority choose surgical. Now when it comes to the Latina community, it could go both ways depending on the circumstances. I do overall feel like they would prefer medical simply because most Latinas will say, ‘I don’t want to be put to sleep.’ They are scared of not waking up. Second is because they are scared, because, when you say surgery … they always ask, ‘Is there cutting involved?’ That is typical common question we get … when I explain to them that is going to occur at home, they feel more comfortable being somewhere, where they are comfortable [not] in a clinic office with all these other staff members or providers and they don’t feel comfortable, especially because they are a different language. I guess something makes it feel safer for them to do it at home … Black [patients] I’ve seen more surgical, because they just want to get this in and out and simple fact, when we explain to them that this is something you want to do at home they panic, like ‘No, no, no I don’t have time for that, I just need to go in there and get me out.’”

A 35-year-old Black woman, Ebony, shared more about mistrust of the medical establishment, medical providers, and the medication abortion pills themselves saying,

“ … probably the fear of … this being like … a trial basis, you know, not knowing whether it would be safe. So if I’m terminating the fetus from medication, what is that doing to my body? Would I eventually have cancer later down the line, would I eventually not be able to conceive again, you know just with these experiments, experiments, experimentation sometimes is the reason especially all ethnic group they don’t really like those things. So when you talk about the syphilis case with the Tuskegee experience and things like that, a lot of times we’re being used … and then you have issues where they were doing an experiment and they were leaving women – black women – sterile.”

While Angelica and Ebony could eloquently articulate intersectional stigma in the context of MA silence is a more common phenomenon surrounding abortion stigma in both Black and Latinx communities. Destiny, a 29-year-old Black woman, shared:

“With this particular topic, I guess people really wouldn’t open and tell you that unless they’re really close to you. I’ve never had any friends or family tell me anything about it.”

Isabella, a 27-year-old Latinx woman, explained,

“I do think it is more stigmatized in minority populations, which can definitely influence if no one’s talking to you about it, you’re not going to have that information available.”

Socio-cultural solutions

To address these socio-cultural barriers, participants suggested that MA social marketing campaigns and story-sharing could reduce stigma and build trust. When asked how MA could ideally be delivered to their communities, Black and Latinx participants described MA and comprehensive sex education campaigns “blasted on … social media … Twitter … Instagram … and Facebook” emphasising, “it’s not gonna work if people don’t know that they’re pregnant”. Participants also described the power of “story-sharing”, especially within trusted networks through “word of mouth” and “women’s support groups”. Others emphasised how they trusted information from other Black and Latinx women – both in their networks and at abortion clinics – to keep them safe. One Black focus group participant, Kourtni, said,

“I’m a woman who was glad to come forward to tell my story because, I think those people, they’re big and bad enough to protest because, they haven’t talked to someone like me … or anybody else who’s had an abortion, or had experience with medication abortion to learn what their specific story was. If you start matching a face and a personality and a life to this instead of just some figment of your imagin[ation] some wanton woman … perhaps, that will end. That’s my hope and that’s part of the reason why I want there to be more conversations about this because this is happening to real people … I want people to talk more about it and I want people to have the license and the courage to come out of the dark. This is not something to be ashamed of.”

Policy barriers and solutions

Policy barriers

Even before the fall of Roe v. Wade or implementation of Georgia’s severe 6-week gestational age limit, participants’ stories demonstrated how policies at the national, state, and institutional levels disproportionately reduce MA accessibility for marginalised groups. When asked about the new 6-week limit that passed in Georgia, Jada, an abortion provider, explained,

“It would be a huge detriment because, Black women, especially those in lower class, they do not have the proper resources or access to the proper resources that maybe a middle class Black woman might have or even, of course, our White counterparts. So I think that that would be a huge detriment for them, and almost taking away our rights more so than, you know, a white woman’s rights.”

At the national and state levels, the Hyde amendment was cited as a major barrier for Black and Latinx women, who are more likely to rely on Medicaid funding, while state laws restricting the use of private insurance for abortion reduced abortion access for even the more affluent women. One abortion provider, Monica, explained,

“We have a lot of women who call … and ask if we accept Medicaid, if Medicaid would cover it. Especially because some of these women are on pregnancy Medicaid when they come in. So unfortunately, we cannot accept Medicaid at all [because of] state law … ’cause you hear about places like California and I know Medicaid covers having an abortion. So it’s, ‘Why can’t we have that?’ … we did offer a discount for those with Medicaid but that’s recently ended.”

Provider participants also cited the Food and Drug Administration’s Risk and Mitigation Strategies (FDA REMS) – which at the time required MA be delivered in-clinic by a physician – as “the biggest one”. Black and Latinx women similarly shared, “I don’t think it should be prescribed just by a doctor.” Even after the FDA REMS were modified to allow telemedicine for abortion and provision by non-physicians, Georgia law still requires the medication to be prescribed by a physician and the legislators attempted (unsuccessfully) to ban telemedicine for abortion.44,45 Providers, CBO leaders, and Black and Latinx women also highlighted state-level mandates such as “mandatory delays” (waiting periods) and inaccurate “required counselling” as key barriers to MA in Georgia. Some clinics are able to review state-mandated counselling over the phone 24-hours in advance when women schedule their MA, but many clinics don’t have the capacity. In turn, MA can take up to three separate visits: mandatory counselling, medication distribution, and follow-up ultrasound. One provider, Gabriela, explained,

“But travel still comes into play for medication abortion … we’ll see a lot of patients from Tennessee who will come to Atlanta … because there is a 48-hour wait law in Tennessee compared to 24-hour here in Georgia. So, I’ve seen multiple patients who will call the office and they have an automated verbal consent 24-hour consent over the phone before or like during your scheduling process … then they are told ok well we can wait 48-hours to schedule you here in Tennessee or 24-hours and you can go to Atlanta. And many people will choose to drive the two [to] three hundred miles to get to Atlanta just so they can get their pills the next day. So, travel, transportation is a huge barrier. The state laws themselves are a barrier. We wouldn’t even need someone to read something through the phone if we didn’t have this 24-hour wait period. We could offer same day counseling, same day service if we did not have that law.”

Policy solutions

Several abortion providers, CBO leaders, and Black and Latinx women cited “advocacy” and political engagement as the best method for improving the policy context. In fact, one clinic recruitment site uniquely integrates clinical services with RJ community outreach and policy advocacy; community members we interviewed describe it as having “more humanity” and being “holistic”. Black and Latinx women described how their own experiences of reproductive injustice (for example, Georgia’s new 6-week gestational age limit29 or contraceptive coercion) fuelled their support for political engagement and advocacy. They also highlighted how abortion restrictions are connected to larger systems of gender, racial, and economic oppression. One 24-year-old Black woman, Lauren, explained,

“I feel like [politics have] made me more confident in my decision to have a medication abortion. Just seeing the type of people who are pushing these agendas … This is disgusting. This is another form of white supremacy at work. I'm not going to like fall into this trap. I'm going to advocate for it regardless and no one can say whatever about it. You do not control my body. Your people have controlled our bodies for way too long. I'm not going to allow your stigmatization and all these scriptures that you bring up that you don't even follow yourself to basically control how I move and what I decide to do with my body … The type of stuff they say is like they have no regard for humanity. The same people who pass the six-week abortion ban are the same people who were uplifting white supremacy and Confederate monuments that have no regard for black lives. They have no say in what I do with my body.”

Clinic- and provider-level barriers and solutions

Clinic- and provider-level barriers

Beyond the impact of policies on local health systems (or sometimes as a consequence of them), we identified numerous clinic- and provider-level factors that further inadvertently decentred patients during abortion services and created unnecessary barriers to MA for Black and Latinx communities. One major category of these barriers was implicit bias stemming from non-representative staff (i.e. not Black or Latinx) and lack of structural competency (i.e. ignorance about structural factors and resulting social inequality) at the abortion clinics, particularly among physicians. One abortion provider, Maya, said it clearly: “I would be fascinated to hear the specific barriers [Black and Latinx patients] face before they get here. It’s hard for me to know … I feel like I don’t know what they are.” Participants repeatedly explained how Black and Latinx patients are more comfortable with and trusting of services from providers who “look” like them and “speak their language”. Elena, the abortion provider who noted Latinx patients prefer medication abortion, explained:

“I’m talking to patients and they say ‘Man that’s expensive’ and I will refer them to other clinics that I know are cheaper than us. But then they’ll end up calling me back and say, ‘No I want to schedule with you because there was nobody who spoke Spanish.’ So it could fall back to a language barrier … if it’s a Spanish-speaking patient, and although they speak English, they always prefer to speak in Spanish, because they feel more comfortable expressing themselves. [I] feel like it’s more of a comfort level especially culture-wise, as well. When they see someone else that speaks the language or have some sort of relation, a common thing … .”

Several patients described instances of not “being present[ed] all the options” (for example, being given injectable contraceptives post-abortion without adequate consent) or being pushed toward surgical abortion instead of MA because of implicit bias about one’s schedule, health literacy, or adherence to follow-up requirements. A 27-year-old Black woman, Brittany, shared,

“A couple of years ago, I had an abortion, and they didn’t give me too much information about the two types. They just said, ‘Okay, well this is the only option’ and I didn’t know that there was another option until much, much later. I actually researched it … and I would have asked for a medical abortion. So I guess doctor’s just like, ‘Oh, this is the only–’ They didn’t present all the options to me … they kind of almost decided for me or it was like a forced decision, but they’ll just, ‘Oh well you’re probably going to want this so let’s just do that.’ And then you know being – I guess you know being panicked, I was just, ‘Okay, well I’ll just do that.’”

Black and Latinx women also faced cost-related barriers resulting from both national/state policy (e.g. Hyde amendment and restrictions against private insurance that require patients to pay out-of-pocket) and clinic-level restrictions that gave Medicaid discounts for surgical but not MA. This led to Black and Latinx community perceptions that some abortion clinics are “just a way to make money”. Cost-related barriers compounded because MA typically requires more visits than surgical abortion.

Clinic- and provider-level solutions

Participants offered many innovative and varied ideas for addressing clinic- and provider-level barriers. Primarily, women and providers alike emphasised the need for diverse Black and Latinx staff that represent the communities they serve, and who can provide empathic, comprehensive counselling that enables reproductive autonomy and informed decision-making. In addition to informational support, participants also emphasised the importance of emotional social support before, during, and after MA - for example, from abortion doulas. Lauren, the 24-year-old Black woman who is now a political advocate for abortion, shared,

“The next day, we went, and I got an [medication] abortion … the passing period really hurt. It was very emotionally taxing. I think having like a doula or something like that, would’ve made the process easier. I really didn’t fully understand what was going on because … I feel like things weren’t really explained to me clearly. I also feel that I was also rushed into then getting this birth control shot that I didn’t fully consent to on the day of my abortion … I feel like the [abortion] explanation process it could have been a little bit more nurturing … It was like very like, ‘These are the things we’re going to do to you,’ as opposed to like, ‘Let’s slowly walk through this.’ Because the decision was easy to make to go and have an abortion. I don’t regret it at all. It’s just I wish the process had a bit more humanity to it and a bit more holistic, but that’s not the reality of our medical world … I would expect more or want more. I feel like maybe I would have gotten that if I … went to a black clinic, with black leadership.”

Additionally, some clinics have opted for flexible scheduling, sliding scale fees, counselling over the phone, and confirmation pregnancy tests at home rather than ultrasound, which accommodates more patients. Gabriela, the abortion provider who noted travel and distance barriers to medication abortion care, explained,

“For medication abortion follow up … our policy is still that we want to see everybody at one to two weeks and routinely we are still doing – we’re still doing transvaginal ultrasounds … but we – I’ve had a couple people forgo the ultrasound option and we just do a pregnancy test, which may still be positive and then we tell people to repeat it themselves in a couple of weeks … Or we do a phone follow up for … a lot of our out-of-towners or we tell people follow up with your regular OB/GYN within a month … we try to make [it] so it’s not hard and fast although we usually prefer them to come in but we can make adjustments depending on a patient’s needs.”

At the same time, as one abortion provider, Christine, said, MA needs to be “de-medicalized” and we must “be more creative … taking this all … outside of the traditional medical institutions … having both information and care available in the community”. Specific ideas included telehealth, community health workers (the RJ abortion clinic has an entire team of Latinx community health workers), and community health fairs. Other participants described how MA education and services can be integrated by providing counselling and referrals to MA care from primary care clinics and CBOs that already provide health and social services to Black and Latinx women. Kimberly, a 39-year-old Black woman and leader of a Black CBO shared,

“ … for clients that do test positive for pregnancy at times, we kinda ask them or some of them may just go out and say they didn’t want to keep the baby and wanted to end pregnancy. So at that time we do have brochures, where they can go through the different types of abortions that are available … [We] used to partner with one abortion center up in Atlanta, and so we kinda give the information on where they can go to get their needs met..”

Finally, our results underscore the importance of comprehensive “holistic” RJ abortion funds that go beyond financial support. Participants described how those groups approach abortion from a RJ framework; provide wrap-around services like childcare, transportation, and lodging; and go above and beyond to ensure no women feel coerced into (or out of) an abortion decision. A leader from one such RJ abortion fund, Simone, said,

“Our [reproductive justice abortion] fund is all people of color, primarily black folks … we aren’t afraid to have these conversations … like ‘Yes, abortion access and family planning in this country, in this world has been very heavily rooted in racism and eugenics. However, that doesn’t mean that like you can’t make the best decision for yourself using a medicine that will help you make that decision.’. … it’s like once again holding that tension of what is true, what has happened, but also doing what is best for you … In this moment, no one is forcing you to make this decision. You can choose to have the pill. You can choose to do surgical. Or you can choose to continue your pregnancy … We can give you a ride up to the clinic, and if you change your mind, that’s fine … ”

Individual-level barriers and solutions

Individual-level barriers

Barriers at higher levels of the socio-ecological model come to bear at the individual level, where Black and Latinx women shoulder the burdens of structural oppression, sociocultural stigma, medical and research exploitation, and inequitable abortion policies. Many participants, like Rosa, a 39-year-old Latina woman and also a Latinx CBO leader, listed the intersectional individual-level barriers in quick order: “lack of information … education … money … fear of … shaming … lack of public transportation … fear of [immigration] raids.” For Black and Latinx women, marginalisation due to sexism, racism, ethnocentrism, economic inequality, and nationalism combine to impede MA access in complex ways. The most obvious and ubiquitous individual-level barrier among community members was “lack of knowledge” and “awareness” about MA. Participants also described how many women lack basic sex education and do not understand their own anatomy. Elena shared this story:

“She was 17 years old … she took the first pill here in our facility … the next day the father had showed up … and he had stated she didn’t feel comfortable inserting the pills, because she did not know where her vagina was at. So right there that was a red flag for us, and we realized going forward we need to make sure that the patient understands their body and understands the comfortability of you inserting those pills.”

Some explained this lack of knowledge increased the gestational age at which Black and Latinx presented for abortion, thus reducing their chances of qualifying for MA. Lack of basic sex education combined with inadequate knowledge about MA also meant eligible Black and Latinx patients were ill-prepared for the physical and logistical challenges of “Day Two” when patients take misoprostol at home. Abortion providers explained all of the layers involved: planning for childcare, privacy, time off work, and a support person. Monica described her approach to abortion education and counselling as,

“I just walk through the whole entire process, ‘Today when you take this pill, this is stopping this is you know the pregnancy won’t progress but Day Two you gotta pass the pregnancy.’ … you might have a little bit of cramping some bleeding but for the most part if you have errands go for it this will not … stop you. But just take some time for yourself Day Two to kinda … .Make yourself comfortable all that … .a lot of times health education becomes a planning session. ‘So what are you gonna do? This takes four to six hours how you gonna do this? You have your kids. Do you have a support person at home?’ I always ask if they’re going to have someone with them … . And if not, then we can come up with different comfort measures so they’re not getting up and moving around a lot. So when they do have children, I ask you know ‘Do you have a partner to help with them or maybe a friend someone?’ If they don’t, we try to think of a time when they’re going to be down. Maybe they can watch a movie for a couple of hours and you can be in the bathroom in the bath tub … women are surprised by the process when they arrive. Fortunately we have the video that kinda gives them a heads up before they reach health education so they know ‘Oh there’s a Day Two, there’s a second part of this.’”

Participants described how this is more challenging for Black and Latinx patients, who do not typically have the financial and social resources of White patients because of structural neglect and disadvantage. One 29-year-old Black woman, Noelle, pointed out the double bind they face: not having the resources to support an(other) child or to access abortion. She said,

“Some people don’t have people to watch kids, so it’s just like, it’s just them. They’re just their own support so. Who would be able to watch their kids, so that’ll be another … ‘Oh, I don’t think I’ll be able to get this abortion because I don’t really have anybody.’ So then you’ll bring another baby into the world that you’re not going to have anyone to help you with … they’re having kids and they don’t have anybody to help them. You didn’t have anyone to help you with the first two, and then you keep having more and more. But it’s like, they don’t have an option to go do this, go get an abortion, because like they’re basically forced to have babies.”

Without access to safe, clinic-based abortion care and faced with the dire alternative of forced pregnancy and motherhood without adequate resources, participants described how individual-level barriers to abortion meant women would turn to “pills off the street”, “curanderos”, clothing hangers, and other forms of “home abortion”. Latinx participants, in particular, also described the “experienced” and “internalised stigma” women in their communities face. Rosa, the Latinx community organisation leader, said,

“I would say definitely religion plays a very important role and people’s cultural beliefs … but also there is the experienced stigma around it. People being harassed. People being discriminated against. People worrying that they won’t be accepted in their families and communities. And then the internalized stigma I think also plays an important role on you know, people feeling embarrassed and guilty about it. And it’s interesting that even people who have (pause). Again, you gotta go case by case. I don’t want to, you know, use a broad brush to paint everybody and say all Latinas feel this way because it also depends on so many other factors like education and access to resources and knowledge and things like that. But, I would say that we have seen, in some cases, that even people who have gotten an abortion, they still do not agree with abortion. They tend to be harsh when people seek abortions.”

Individual-level solutions

At the same time, our participants offered solutions for addressing these individual-level barriers and challenges. Primarily, they pointed to the importance of “social support” from their extended networks and from abortion-related institutions. While Black and Latinx women explicitly noted how family members and friends could be harmful, the financial, transportation, childcare, informational, and emotional support made MA a possibility. Women also cited the RJ abortion fund, the National Abortion Federation, and abortion clinic employees as key sources of social support. In fact, some clinics offered “abortion doulas”, who were available for support in the clinic (and one participant described how they could be expanded to support women at-home during “Day Two”). Like when discussing solutions for socio-cultural barriers and Medicaid mistrust, Black and Latinx women also discussed how “word of mouth”, “stories”, and asking someone they “trust” was an essential way to receive reliable MA information and address individual-level barriers like lack of knowledge. When asked how to make MA access easier, one 24-year old Latinx participant, Luis, said,

“I think word of mouth. Uhm, I feel like if someone did have that experience, and it was a positive experience, uhm, I feel like the community that we serve has a big emphasis on other people’s experiences … because its someone they feel like they trust and can identify with instead of … someone who speaks English and can’t really, they can’t really identify with or communicate with.”

Finally, Black and Latinx community members described abortion attitudes in a nuanced way that holds space for both personal beliefs and respecting others’ bodily autonomy with great potential for reducing stigma. Rhonda, a 49-year-old Black woman and leader of a Black CBO, explained,

“We, it’s very mixed, ah, very mixed emotions when it comes to abortions. … even those that may not have had an abortion because they don’t believe in it, they still believe that a woman has a freedom of choice, whether or not, you know, she wants to have an abortion or not … So … it’s a mixture … If I would say the majority … will probably be against having an abortion, but be for, they would be for a woman having a choice, if that makes sense.”

Discussion

This community-led study applied a uniquely RJ approach to understand MA perceptions, barriers, and experiences among Black and Latinx women in metro-Atlanta, Georgia. Our qualitative findings build on, deepen, and in some cases challenge the existing evidence on MA among Black and Latinx communities. Results depicted a complex web of inter-related and intersectional barriers to MA from the socio-cultural to health systems to individual levels. These included barriers rooted in marginalisation, stigma, and mistrust. Importantly, our findings contribute new insights as Black and Latinx participants’ presented numerous solutions rooted in equity, respect, resilience, and trust. These are needed more than ever after the Supreme Court rolled back federal abortion protections, allowing states like Georgia to enact and implement severely restrictive and harmful abortion bans.

A previous quantitative study with several hundred participants found that Black women prefer MA less than surgical abortion methods.1 In our study, participants described important context and pointed to mechanisms that might explain abortion preferences – or inequities – among racial and ethnic minority women. These include mistrust of pills (as a result of historical and ongoing medical and research exploitation of Black communities) and difficult MA logistics including multiple visits and down time on “Day Two”. Another study (n = 270) reported high rates of acceptability of MA among low-income Latinxs living in New York City, but that they still chose surgical over MA 61% of the time.3 In our data, we noted conflicting observations: first, Latinx patients are more likely to choose MA due to fears about surgery and preferences for being in the comfort of their home. At the same time, Latinx patients are less likely to opt for MA because it requires multiple visits, which can be dangerous for undocumented immigrants. Moreover, our study found that lack of education about and awareness of MA is the most common barrier to MA services. The first step to improving equitable access to MA will be increasing MA education and awareness. Future research will need to quantitatively assess Black and Latinx women’s methods preferences and correlate those with factors identified in our study including not only the commonly cited barriers (transportation, cost, childcare needs) but also medical mistrust, lack of Black and Latinx providers, level of understanding about the options, and lack of support for “Day Two”.

Like ours, other studies have described abortion stigma as a relational and cyclical process that ascribes negative attributes to and discriminates against people who have abortions and those who are associated with it.46–50 One key factor of abortion stigma is silence – as we saw in our study – which contributes to the prevalence paradox, wherein a common procedure like abortion is perceived as rare and deviant.46,48 Researchers also explain that abortion stigma, while universal, is also deeply contextualised and moulds to existing local power hierarchies.46,47,51 Our findings echo this literature and demonstrate how stigma is intersectional, meaning it intersects with other forms of stigma based on socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, and other individual circumstances.52,53 One study in South Africa by Mosley et al.54 also suggested this intersectional nature of abortion stigma, drawing on the Earnshaw and Kalichman’s framework developed among patients living with HIV.55 So while our findings on abortion stigma here are not new, per se, they uniquely represent the multiplicative effects of negative sociocultural norms around MA specifically and other types of discrimination and marginalisation experienced by Black and Latinx women more broadly. Further qualitative work is needed to adequately understand and conceptualise this intersectional stigma, while revised quantitative measures are needed that capture the intersectional dimensions of abortion stigma.

Additionally, not unlike prior studies on restrictive abortion contexts, our Southeastern-based participants agreed that current policies about and regulation of MA create inequitable barriers for Black and Latinx communities, who are disproportionately affected by poverty, racism, and immigration enforcement. Notably, this was before the Supreme Court decision that overturned Roe v. Wade and the enactment of Georgia’s early abortion ban. Like previous studies, we identified several policies as major MA barriers including physician-only prescription privileges, mandatory waiting periods, mandated (inaccurate) counselling, and the Hyde amendment.2,56 Since data collection, the Georgia state legislature also introduced a bill to outlaw MA via telemedicine (although it did not pass into law) despite the recent FDA decision to remove the REMS requirement for in-person administration of mifepristone.45,57 Participants also described clinic-level policies that decrease MA access including high costs without discounts or sliding scale and required in-person follow-up visits. Collectively, these national, state, and clinic-level policies emerged as upstream determinants of inequitable MA access that cause a cascading effect on other levels of the social ecology. For example, study participants described how sociocultural stigma against abortion leads to state restrictions such as inaccurate mandatory counselling, which leads to clinic-level policies for multiple visits, increases the amount of transportation needed to and from the clinic, increases the cost of MA, and ultimately dissuades Black and Latinx women from choosing that method. Furthermore, our results demonstrate the reciprocal and cyclical relationship between sociocultural stigma and restrictive abortion policy wherein social and cultural norms lead to policies that restrict abortion access, then restrictive policies further contribute to abortion stigmatisation by portraying it as a dangerous and immoral procedure.46–48 Future studies could illuminate those bidirectional pathways between sociocultural norms and policy with the intent of identifying points of intervention. For example, Harris and colleagues are studying how providers’ messaging around abortion can reduce stigma and possibly enable more equitable policies.58

In considering strategies to combat or prevent barriers to MA, our participants proposed that services must be culturally appropriate and available more widely in community settings with trusted providers including telemedicine. This will require addressing (rightful) mistrust at all levels through story-sharing, diverse abortion clinic staff, RJ policy advocacy, RJ abortion funds, education from trusted networks, and structural competency training for abortion providers. Community-based integration of MA education and services can include community health workers, health fairs, social marketing campaigns, and women’s support groups, focused not just on MA but on comprehensive sex education more broadly. Finally, future research needs to centre Black, Latinx, and other marginalised communities through community engagement built on mutual respect, two-way learning, and trust-building.

Several limitations of our study must be noted. First, as a community-based qualitative study, our findings are not meant to be fully representative of a general population nor can they be interpreted as causal. Nonetheless, our diverse purposive sample of relevant stakeholders brings new complementary perspectives to the timely question of MA access. Rather, the study provides deep insight into the contexts, perceptions, and stories of Black and Latinx women, providers and community leaders in metro-Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Second, our study does not adequately explore MA among other groups including trans, gender non-conforming, and rural communities, which all represent important groups that have been under-represented in MA research, experience disparate outcomes, and should be the focus of future research.

Conclusion

Ultimately, this project illuminated new barriers to MA – and solutions to them – while deepening our understanding of MA among Black and Latinx communities. These contributions can be attributed, at least in part, to the paradigm-shifting community-led family planning research approach taken by our advocate-academic-clinical team predominantly composed of Black and Latinx women. Moving forward in the wake of Dobbs v. Jackson, policymakers, clinicians, advocates, and researchers alike will need to “be more creative” to improve access to MA services for racial/ethnic minorities in the US This study carries numerous implications for action, advocacy, and research. These include (1) more community-led research initiatives that apply an RJ framework to family planning studies, (2) de-medicalisation of MA that situates information and services in the community including integration with community-based organisations and clinics as well as telemedicine, (3) more “holistic” and “humane” abortion clinics with diverse staff who represent the communities being served, and (4) RJ policy advocacy that addresses not only abortion access but also underlying structural determinants (poverty, racism, education, transportation) of Black and Latinx health.

Acknowledgements

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the funding agencies.

Appendices.

Appendix A. In-depth interview guide for key informant abortion providers on medication abortion in Georgia (English Only)

Warm-Up

-

1.

Tell me about how you interact with clients at this organization.

-

2.What groups of people does your organization serve?

- Probe: demographics by race/ethnicity, income, sexuality, geographic location, language preferred

Thank you for that information. Now I would like to talk to you about your interactions and experiences with people who seek abortion services at this organization.

Current Abortion Services for Black and Latinx Clients

-

3.

What abortion services do Black and Latinx clients typically utilize at your clinic?

-

4.Can you describe the steps for getting a medication abortion at your clinic?

- Probe if not mentioned: number of visits, gestational limits, counseling, decision-making process of medication vs surgical abortion, follow-up, cost

-

5.

Can you describe a time when a Black client accessed medication abortion services at your clinic?

-

6.

Can you describe a time when a Latinx client accessed medication abortion services at your clinic?

-

7.

Can you describe a time when a White client accessed medication abortion services at your clinic?

Barriers and Facilitators in Medication Abortion Delivery

-

8.What makes it easier for clients to get a medication abortion at your clinic?

- Ask of all: What things about the clinic make it easier?

- Ask of all: What things about the client make it easier?

- Ask of all: What things make it easier for your Black clients to get a medication abortion?

- Ask of all: What things make it easier for your Latinx clients to get a medication abortion?

-

9.What makes it harder for clients to get a medication abortion at your clinic?

- Ask of all: What things about the clinic make it harder?

- Ask of all: What things about the client make it harder?

- Ask of all: What things make it harder for your Black clients to get a medication abortion?

- Ask of all: What things make it harder for your Latinx clients to get a medication abortion?

Policy Factors in Medication Abortion Delivery

-

10.

What state and federal policies* impact your clinic’s ability to provide abortion services?

* If participant needs examples: mandatory counseling, 24-hour waiting period, no public funding unless client’s life is endangered, parental notification required for minors, gestational limits (up to 10 weeks for medication abortion)*- Ask of all: How do those policies influence medication abortion services at your clinic, if at all?

- Ask of all: How do those policies influence medication abortion services for Black clients, specifically?

- Ask of all: How do those policies influence medication abortion services for Latinx clients, specifically?

-

11.[If the participant has not already mentioned this:] Georgia legislators have passed an abortion-related bill that could be enacted in January 2020 and would outlaw abortion at 6 weeks gestation age with exceptions for the mother’s life, rape/incest, and nonviable pregnancies. How would this policy influence medication abortion services at your clinic, if at all?

- Ask of all: How would this policy influence medication abortion services for Black clients, specifically?

- Ask of all: How would this policy influence medication abortion services for Latinx clients, specifically?

Thank you. Now I would like to ask about your ideas for how medication abortion services can best be offered to the communities you serve.

Recommendations for Integrated Service Delivery

-

12.How could medication abortion be combined into other health and social services?

- Probe: referrals, HIV testing, linkage-to-care, wellness and prevention services (pap smears, diabetes management), other reproductive health services including contraception

-

13.

In an ideal world, how would medication abortion services be offered to the communities you serve?

Wrap-Up

-

14.What other thoughts or questions would you like to share before we wrap-up?

- Probe: what topics did we not cover that are relevant?

Appendix B. In-depth interview guide for key informant community-based organization leaders on medication abortion in Georgia (English and Spanish)

Warm-Up

-

1.Tell me about your organization.

- Probe: mission(s), day-to-day operations

-

2.What groups of people does this organization serve?

- Probe: demographics by race/ethnicity, income, sexuality, geographic location, language preferred

-

3.In what ways do you interact with clients in your role at this organization?

- Probe: main role, major responsibilities

Thank you for that information. Now I would like to talk to you about your perceptions and experiences with abortion. Remember there are no right or wrong answers, and our conversation will be confidential.

Language of Medication Abortion

-

4.

Have you heard of medication abortion?

[If no, continue by reading the script and definition below]- [If yes]: What is medication abortion?

Thank you for that explanation. This study is about medication abortion. When we refer to medication we mean the use of medication pills rather than surgery to end a pregnancy through abortion. Medication abortion is safe and can be used during the first trimester of pregnancy. In Georgia, medication abortion must be prescribed by a doctor.

-

5.At your organization, how do people talk about medication abortion, if at all?

- Ask of all: what words do they use?

- Ask of all: what do they say about medication abortion?

- Probe, if participant is talking about abortion broadly: what about medication abortion, specifically?

-

6.In the communities you serve, how do people talk about medication abortion, if at all?

- Ask of all: what words do they use?

- Ask of all: what do they say about medication abortion?

- Probe, if participant is talking about abortion broadly: what about medication abortion, specifically?

Social and Policy Contexts of Medication Abortion

-

7.In the communities you serve, how do people feel about abortion?

- Probe: social norms, religion, attitudes, beliefs, fears, differences by gender and age

- Ask of all: how do people feel about medication abortion, specifically?

-

8.In the communities you serve, what would happen if someone had a medication abortion and their community found out?

- Probe: why is that?

-

9.Thinking about the communities you serve, what makes it hard for someone to have a medication abortion?

- Probe: access to services, knowledge about medication abortion, availability of medication abortion, acceptability of abortion, socioeconomic barriers, transportation, childcare arrangements

-

10.Thinking about the communities you serve, what makes it easier for someone to have a medication abortion?

- Probe: convenient locations of abortion services, knowledge about available services, normalization of abortion use, financial support, social support

-

11.Have you ever experienced medication abortion or known someone who experienced medication abortion?

- [If yes]: what was that like?

- [If yes]: what supported you/that person to have a medication abortion?

- [If yes]: what made it hard for you/that person to get a medication abortion?

- [If no]: have you ever or known someone who experienced any other kind of abortion? (Probe: what was that like?)

-

12.Have you ever known or heard of someone who had a home abortion or a “do-it-yourself” abortion?

- [If yes]: what was that like? (Probe: what were the circumstances?)

-

13.Thinking about the communities you serve, how do public policies influence medication abortion use?

- If participant needs abortion policy examples: mandatory counseling, 24-hour waiting period, no public funding unless pregnant person’s life is endangered, parental notification required for minors, gestational limits (up to 10 weeks for medication abortion)

- If participant needs other public policy examples: TANF (welfare), WIC, food stamps, CHIP (child health insurance), Medicaid

-

14.

Georgia legislators recently passed an abortion-related bill that could go into effect January 2020 and would outlaw abortion at 6 weeks gestation age with exceptions for the mother’s life, rape/incest, and pregnancies where the fetus has a condition that is incompatible with life. How would this policy influence medication abortion services in the communities you serve, if at all?

-

15.What other things influence medication abortion use in the communities you serve?

- Probe: religion, poverty, history of abortion and eugenics, (costs of) childrearing, health risks of pregnancy

Recommendations for Integrated Service Delivery

-

16.Right now, how does your organization address medication abortion, if at all?

- [If yes]: can you tell me about a specific time when your organization addressed medication abortion?

- [If no]: why does your organization not address medication abortion?

-

17.Hypothetically, how could medication abortion be combined into existing health and social services?

- Probe: what steps are needed for that to happen?

-

18.

In an ideal world, how would medication abortion services be offered to the communities you serve?

Wrap-Up

-

19.What other thoughts or questions would you like to share before we wrap-up?

- Probe: what topics did we not cover that are relevant?

Calentamiento

-

1.Háblame de tu organización.

- Sondeo: misión (es), operaciones del día a día

-

2.¿A qué grupos de personas sirve esta organización?

- Sondeo: datos demográficos por raza / etnia, ingresos, sexualidad, ubicación geográfica, idioma preferido

-

3.¿De qué manera interactúa con los clientes en su título en esta organización?

- Sondeo: título principal, mayores responsabilidades

Gracias por esa información. Ahora me gustaría hablar sobre sus percepciones y experiencias con el aborto. Recuerde que no hay respuestas correctas o incorrectas, y nuestra conversación será confidencial.

El Lenguaje del Aborto con Medicamentos

-

4.

¿Has oído hablar de la medicación aborto?

[Si la negativa, continúe leyendo el guión y la definición a continuación]- [En caso afirmativo]: es¿Qué es el aborto con medicamentos?

Gracias por esa explicación. Este estudio trata sobre el aborto con medicamentos. Cuando nos referimos a medicamentos, nos referimos al uso de píldoras de medicamentos en lugar de a la cirugía para interrumpir un embarazo mediante el aborto. El aborto con medicamentos es seguro y puede utilizarse durante el primer trimestre del embarazo. En Georgia, el aborto con medicamentos debe ser recetado por un médico.

-

5.En su organización, ¿cómo habla la gente sobre el aborto con medicamentos, si es que lo hace?

- Pregunte a todos: ¿qué palabras usan?

- Pregunte a todos: ¿qué dicen sobre el aborto con medicamentos?

- Sondeo: si el participante está hablando en términos generales sobre el aborto: ¿qué pasa con el aborto con medicamentos, específicamente?

-

6.En las comunidades a las que sirve, ¿cómo habla la gente sobre el aborto con medicamentos, si es que lo hace?

- Pregunte a todos: ¿qué palabras usan?

- Pregunte a todos: ¿qué dicen sobre el aborto con medicamentos?

- Sondeo: si el participante está hablando en términos generales sobre el aborto: ¿qué pasa con el aborto con medicamentos, específicamente?

Contextos Sociales y Políticos del Aborto con Medicamentos

-

7.En las comunidades a las que sirve, ¿cómo se siente la gente con respecto al aborto?

- Sondeo: normas sociales, religión, actitudes, creencias, temores, diferencias por género y edad

- Pregúntele a todos: ¿cómo se sienten las personas con respecto al aborto con medicamentos, específicamente?

-

8.En las comunidades donde presta servicios, ¿qué pasaría si alguien se hiciera un aborto con medicamentos y su comunidad lo descubriera?

- Sonda: ¿por qué es eso?

-

9.Pensando en las comunidades a las que sirve, ¿por qué es difícil para alguien abortar con medicamentos?

- Sondeo: acceso a servicios, conocimiento sobre el aborto con medicamentos, disponibilidad de aborto con medicamentos, aceptabilidad del aborto, barreras socioeconómicas, transporte, arreglos para el cuidado de niños

-

10.Pensando en las comunidades a las que sirve, ¿qué hace que sea más fácil para alguien abortar con medicamentos?

- Sondeo: ubicaciones convenientes de servicios de aborto, conocimiento sobre los servicios disponibles, normalización del uso del aborto, apoyo financiero, apoyo social

-

11.¿Alguna vez ha experimentado un aborto con medicamentos o conoce a alguien que haya sufrido un aborto con medicamentos?

- [En caso afirmativo]: ¿cómo fue eso?

- [Si la respuesta es afirmativa]: ¿qué lo ayudó a usted / a esa persona a tener un aborto con medicamentos?

- [Si la respuesta es sí]: ¿qué le hizo difícil a usted / esa persona obtener un aborto con medicamentos?

- [Si no]: ¿Alguna vez has conocido a alguien que haya tenido algún otro tipo de aborto? (Sondeo: ¿Cómo fue eso?)

-

12.¿Alguna vez ha sabido o escuchado de alguien que haya tenido un aborto en casa o un aborto por “hágalo usted mismo”?

- [En caso afirmativo]: ¿cómo fue eso? (Sondeo: ¿Cuáles fueron las circunstancias?)

-

13.Pensando en las comunidades a las que sirve, ¿cómo influyen las políticas públicas en el uso del aborto con medicamentos?

- Si la participante necesita ejemplos de políticas de aborto: consejería obligatoria, período de espera de 24 horas, sin financiamiento público a menos que la vida de la persona embarazada esté en peligro, se requiera notificación a los padres de los menores, límites gestacionales (hasta 10 semanas para el aborto con medicamentos)

- Si la participante necesita otros ejemplos de políticas públicas: TANF (bienestar), WIC, cupones de alimentos, CHIP (seguro de salud infantil), Medicaid

-

14.