Abstract

The effects of Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin (LKT) on the activity of phospholipase D (PLD) and the regulatory interaction between PLD and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) were investigated in assays using isolated bovine neutrophils labeled with tritiated phospholipid substrates of the two enzymes. Exposure of [3H]lysophosphatidylcholine-labeled neutrophils to LKT caused concentration- and time-dependent production of phosphatidic acid (PA), the product of PLD. LKT-induced generation of PA was dependent on extracellular calcium. Both production of PA and metabolism of [3H]-arachidonate ([3H]AA)-labeled phospholipids by PLA2 were inhibited when ethanol was used to promote the alternative PLD-mediated transphosphatidylation reaction, resulting in the production of phosphatidylethanol rather than PA. The role of PA in regulation of PLA2 activity was then confirmed by means of an add-back experiment, whereby addition of PA in the presence of ethanol restored PLA2-mediated release of radioactivity from neutrophil membranes. Considering the involvement of chemotactic phospholipase products in the pathogenesis of pneumonic pasteurellosis, development and use of anti-inflammatory agents that inhibit LKT-induced activation of PLD and PLA2 may improve therapeutic management of the disease.

Pasteurella haemolytica biotype A serotype 1 is the primary bacterial agent of bovine pneumonic pasteurellosis, or shipping fever (9), a disease characterized by extensive infiltration of neutrophils and exudation of fibrin into airways and alveoli (29). Instead of clearing the bacterial infection, mobilized neutrophils aggravate lung injury (3, 25), probably by undergoing degranulation and lysis, resulting in the release of inflammatory mediators, superoxides, and proteolytic enzymes.

A bacterial virulence factor that appears to contribute substantially to infiltration of neutrophils into sites of P. haemolytica infection is P. haemolytica leukotoxin (LKT). LKT is a pore-forming RTX (repeats-in-toxin) cytotoxin produced by log-phase bacteria that is specifically cytolytic to ruminant leukocytes and platelets (7, 8). Exposure of bovine neutrophils to LKT stimulates not only degranulation and production of superoxides (18) but also synthesis of chemotactic eicosanoids, such as leukotriene B4 (LTB4) (6). LTB4 is a potent chemotactic agent for bovine neutrophils (15) and has been implicated as an important mediator of P. haemolytica-induced inflammation (5).

LTB4 is derived from oxidation of arachidonic acid (AA), which is released from membrane phospholipids by the action of phospholipases (21). In a previous study, we demonstrated that exposure of bovine neutrophils to LKT results in increased activity of cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) and subsequent synthesis of LTB4; a specific inhibitor of cPLA2 inhibited both the release of membrane AA and the production of LTB4 (27). LKT-induced effects on cPLA2 were dependent on extracellular Ca2+, consistent with the role of calcium in promoting translocation of cPLA2 from the cytosol to cell membranes. However, it is unlikely that regulation of cPLA2 occurs entirely via the direct effects of intracellular Ca2+. In human neutrophils, PLA2 acts in concert with phospholipase D (PLD), which occupies a central position in the signaling cascade leading to neutrophil activation and synthesis of eicosanoid mediators in response to physiological stimulators (1). Future research exploring the use of anti-inflammatory agents to attenuate LKT-induced inflammation depends on elucidation of the principal regulatory mechanisms controlling phospholipid metabolism. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to determine whether LKT causes an increase in PLD activity in bovine neutrophils and to study the regulatory role of PLD in LKT-induced activation of PLA2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of P. haemolytica LKT.

P. haemolytica LKT and LKT-negative control [LKT(−)] preparations were prepared as described previously (27), using a P. haemolytica biotype A serotype 1 wild-type strain (89010807N) and its isogenic LKT-deficient mutant (LKT− 11-36, produced by allelic replacement of LktA with a β-lactamase bla gene) (20). LKT activity was quantified as toxic units (TU), using BL3 cells, as described previously (6). One TU was defined as the amount of LKT that caused 50% maximal leakage of lactate dehydrogenase from 4 × 105 BL3 cells in 200 μl at 37°C after 1 h of incubation. The mean activity of undiluted LKT preparations used in this study was (6.6 ± 1.9) × 105 TU/ml. LKT and LKT(−) preparations were divided into aliquots and stored frozen at −135°C until use.

Preparation of bovine neutrophils.

Two healthy beef calves (200 ± 50 kg) served as blood donors for isolation of neutrophils. Neutrophils were isolated by hypotonic lysis as described previously (27) and suspended in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS). Cell concentration and viability were estimated by hemocytometer and trypan blue exclusion. Proportions of viable neutrophils were greater than 95%.

Radiolabeling of bovine neutrophils.

Activity of PLD was assayed by measuring the release of radioactivity from cells labeled with 1-O-alkyl-[1′-2′-3H]-2-lyso-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine ([3H]lyso-PC; 30 Ci/mmol; Dupont NEN Research Products, Boston, Mass.). [3H]lyso-PC was suspended by sonication in Ca2+-free HBSS (7 μCi of [3H]lyso-PC in 70 μl of ethanol was mixed with 10 ml of HBSS buffer) and then added to the tube containing the bovine neutrophil pellet. The cell concentration was ≈3.0 × 107 cells per ml. Cell suspensions were incubated at 37°C for 45 min, washed twice with cold HBSS, and finally suspended in modified HBSS (1 mM Ca2+, 0.5 mM Mg2+, 50 μM EGTA) at 1.5 × 107 cells/ml.

Activity of PLA2 was assayed by measuring the release of [3H]arachidonate ([3H]AA) from radiolabeled cell membranes. Bovine neutrophils were labeled by using a modification of the method described by Ramesha and Taylor (24). Briefly, [3H]AA (100 μCi/ml or 0.0010 mmol/ml of ethanol; Dupont NEN Research Products) was added to neutrophils in suspension (2.0 × 107 cells/ml) at 0.5 μCi/ml, and the suspension was then incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Thereafter, the suspension was centrifuged (200 × g, 10 min), and the cell pellet washed twice with cold HBSS before resuspension of the neutrophils in HBSS containing 0.5 mM MgCl2, 50 μM EGTA, and 1 mM CaCl2 at a concentration of 1.0 × 107 to 1.5 × 107 cells/ml.

Effect of LKT on neutrophil PLD activity.

Concentration- and time-dependent effects of LKT and controls were tested in 10-ml glass tubes. LKT-induced responses were distinguished by comparison with LKT(−). Concentration-dependent effects of LKT on PLD activity were studied by incubating [3H]lyso-PC-loaded neutrophils with dilutions (1:100, 1:1,000, 1:50,000) of LKT or LKT(−) for 15 min. The relationship between period of incubation and LKT-induced stimulation of PLD was measured by incubating neutrophils with LKT (1:1,000) or LKT(−) (1:1,000) for 0, 2, 5, 10, or 15 min. Experiments included at least three replicates for each of the primary treatments.

Stimulation was terminated by addition of 3 ml of chloroform-methanol (1:2, vol/vol) and 0.1 ml 9% formic acid, and lipids were extracted by a modification of the method of Bligh and Dyer (2). Briefly, the mixture was vortexed for 2 min, 2 ml of chloroform was added, and the mixture was vortexed for 30 s; this was followed by further addition of 1 ml of water and mixing for 30 s. After centrifugation at 600 × g for 10 min, the chloroform phase was removed and evaporated under a stream of nitrogen. Lipid precipitates were resuspended in 30 μl of chloroform-methanol (9:1, vol/vol) and separated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on channeled Silica Gel G 60 TLC plates (250-mm thickness, 20- by 20-cm plates; Fisher Scientific Co., St. Louis, Mo.) by development for 70 min in the organic phase of a solvent system consisting of ethyl acetate–iso-octane–acetic acid–water (110:50:20:100, vol/vol) (1). Silica gel bands corresponding to phosphatidic acid (PA), the primary product of PLD-catalyzed hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine, were identified by parallel elution of PA standard (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and scraped into scintillation vials for measurement of radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting (model LC5000TD; Beckman Instruments). Radioactivities in eluted bands corresponding to lipid standards were expressed as percentages of total radioactivity extracted from the sample (radiolabeled substrate and products) and spotted onto the plates.

Effect of ethanol on LKT-induced production of PA.

Ethanol does not inhibit PLD but rather promotes transphosphatidylation activity, resulting in the production of phosphatidylethanol (PET) instead of PA. To confirm that LKT-induced PA production was due to PLD activation, [3H]lyso-PC-labeled bovine neutrophils were exposed to LKT (1:500) in the presence of ethanol (0 to 2.5%, vol/vol). After incubation at 37°C for 15 min, production of PA and PET was measured by TLC as described above, using PA and PET (Avanti Polar-Lipids, Inc., Alabaster, Ala.) standards for identification of product bands.

Involvement of calcium in LKT-induced activation of PLD.

The extracellular Ca2+ dependence of LKT-induced production of PA from radiolabeled neutrophils was tested by altering the concentration of calcium in the neutrophil suspension media. Neutrophils were suspended in calcium-free HBSS, HBSS with 1 mM CaCl2, HBSS with 1 mM EGTA, or HBSS with 3 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM EGTA. Additional CaCl2 and MgCl2 were not added as in previous experiments. The production of PA was estimated after 15 min of incubation at 37°C as described above.

Regulation of PLA2 activity by PLD.

The regulatory influence of PLD on PLA2 activity was investigated by studying the effect of the PLD product, PA, on release of radioactivity from [3H]AA-labeled neutrophils. Initially, labeled neutrophils were exposed to LKT in the presence or absence of ethanol (0 to 2.5%, vol/vol) to inhibit PLD-catalyzed production of PA. Thereafter, effects of PA produced by PLD were confirmed by exposing neutrophils to LKT in the presence of ethanol with or without added PA. At the completion of each incubation period (15 min at 37°C), experiments were terminated by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min, 100-μl aliquots supernatants were suspended in 5 ml of liquid scintillation cocktail (Atomlight; Dupont NEN Research Products), and radioactivity was measured for 5 min by liquid scintillation counting. Release of radiolabeled phospholipid product was expressed as a percentage of total radioactivity incorporated into neutrophils.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were conducted by using a commercially available microcomputer program (SYSTAT Inc.). Concentration- and time-dependent effects of LKT on PA production were compared to results for corresponding LKT(−) controls, using unpaired t tests. The effects of extracellular Ca2+ dependency of LKT-induced responses were investigated by using the general linear model followed by selected comparisons of means, using Fisher’s least significant difference test. The effects of ethanol or PA on production of PA or PET, or release of radioactivity from [3H]AA-labeled neutrophils were investigated by comparing the response at each dosage level with that of the ethanol- or PA-free control, using Dunnett’s test. Results are reported as means ± standard deviations (SD). Differences between means were declared significant at the P < 0.05 level.

RESULTS

LKT-induced activation of PLD.

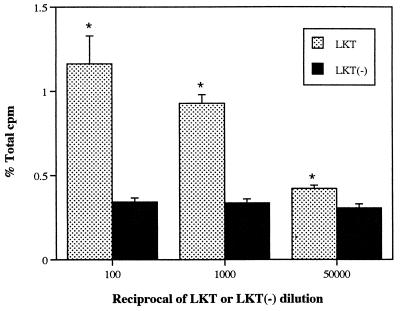

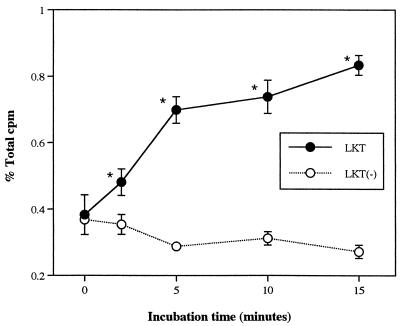

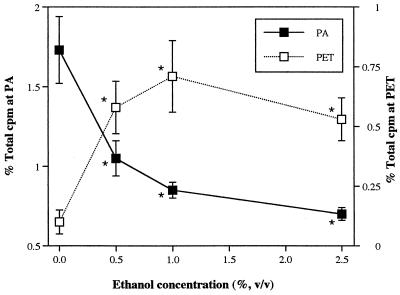

When exposed to a high concentration of LKT (1:100 dilution), production of PA by isolated neutrophils increased approximately threefold compared with that induced by LKT(−), which represents spontaneous release unrelated to LKT. Expressed as a percentage of total radioactivity recovered from each sample (including labeled substrate and products), the amount of PA produced in response to LKT was similar to that produced by human neutrophils primed with tumor necrosis factor alpha and stimulated with N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (approximately 3%, versus 0.6% for the negative control) (1). LKT caused production of PA in isolated bovine neutrophils in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, whereas LKT(−) failed to stimulate PA production (Fig. 1 and 2). PA production in bovine neutrophils appeared less sensitive to LKT than the [3H]AA release that was observed in a previous study (27). As the concentration of LKT was decreased from 1:100 to 1:1,000, release of [3H]AA decreased by approximately 60% (27) whereas PA production decreased by only 20% (Fig. 1). In the presence of ethanol, LKT-induced PA production decreased whereas production of PET (the product of PLD transphosphatidylation activity) increased in an ethanol concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3). These results confirmed that exposure of bovine neutrophils to LKT resulted in increased PLD activity.

FIG. 1.

Effect of LKT and LKT(−) control preparation on production of PA in isolated bovine neutrophils. Neutrophils were loaded with [3H]lyso-PC, exposed to dilutions of LKT or LKT(−) for 15 min, and subjected to TLC (n = 3). % Total cpm = proportion of total recovered radioactivity corresponding to PA standard. ∗, mean (±SD) LKT values were significantly higher than corresponding LKT(−) values.

FIG. 2.

Time-dependent effects of LKT and LKT(−) on production of PA in isolated bovine neutrophils. Neutrophils were loaded with [3H]lyso-PC, exposed to 1:1,000 dilutions of LKT or LKT(−) for various periods, and subjected to TLC (n = 3). % Total cpm = proportion of total recovered radioactivity corresponding to PA standard. ∗, mean (±SD) LKT values were significantly higher than corresponding LKT(−) values.

FIG. 3.

Effects of ethanol on production of PA and PET by isolated bovine neutrophils. Neutrophils were loaded with [3H]lyso-PC, exposed to a 1:500 dilution of LKT for 15 min in the presence or absence of ethanol, and subjected to TLC (n = 3). % Total cpm at PA = proportion of total radioactivity corresponding to PA standard. % Total cpm at PET = proportion of total radioactivity corresponding to PET standard. ∗, mean (±SD) values were significantly different from the corresponding 0% ethanol value.

The effect of LKT on PLD activity in bovine neutrophils was Ca2+ dependent (Table 1). Removal of Ca2+ from the incubation medium caused decreased PA production by [3H]lyso-PC-labeled neutrophils. LKT-induced effects were significantly but not completely restored when a high concentration of Ca2+ that exceeded the chelating capacity of EGTA was added.

TABLE 1.

Extracellular calcium dependence of LKT-induced production of PA in isolated neutrophils exposed to LKT in various buffer suspensions

| Incubation condition | % Total cpm corresponding to PAa |

|---|---|

| 1 mM CaCl2, 0 mM EGTA | 1.06 ± 0.09b |

| 0 CaCl2, 0 mM EGTA | 0.427 ± 0.03c |

| 0 mM CaCl2, 1 mM EGTA | 0.435 ± 0.05c,d |

| 3 mM CaCl2, 1 mM EGTA | 0.535 ± 0.03d |

Data are expressed as the proportion of total radioactivity, including substrates and products, recovered from each sample. Values are significantly different except those with the same superscripts.

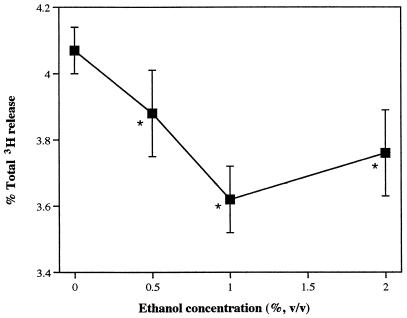

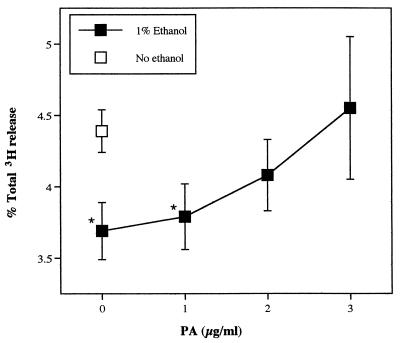

The effects of ethanol on release of [3H]AA from LKT-exposed neutrophils, with or without addition of PA, provided strong evidence that PLD regulates PLA2 activity. As the ethanol concentration was increased between 0 and 1%, LKT-induced [3H]AA release decreased (Fig. 4). Preliminary experiments had determined that ethanol is cytotoxic to neutrophils at high concentration, but at concentrations less than 2%, there were no adverse effects on cell membrane integrity, as measured by lactate dehydrogenase release. When exogenous PA was added in the presence of 1% ethanol, release of radioactivity from [3H]AA-labeled neutrophils was restored (Fig. 5). The effect of exogenous PA on PLA2 activity was concentration dependent.

FIG. 4.

Effect of ethanol on release of [3H]AA and AA metabolites from isolated bovine neutrophils. Neutrophils loaded with [3H]AA were exposed to LKT (1:500) in the presence or absence of ethanol for 15 min, and released radioactivity was measured (n = 3). ∗, mean (±SD) values were significantly different from the corresponding 0% ethanol value.

FIG. 5.

Restoration of [3H]AA release by PLA2 in the presence of ethanol by addition of exogenous PA. Neutrophils loaded with [3H]AA were exposed to LKT (1:500) in the presence or absence of ethanol for 15 min, and exogenous PA was added before measurement of release of radioactivity (n = 3). ∗, mean (±SD) LKT values were significantly different from the no-ethanol value.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have indicated that bovine neutrophils play a central role in the development of acute pneumonic pasteurellosis. Experimental aerosol exposure of P. haemolytica A1 to calves induces rapid infiltration of neutrophils into the lung (26) and a marked change in the neutrophil/macrophage ratio (17). These changes are closely correlated with reported histologic changes in which small airways become plugged with purulent exudate (17). There is reliable evidence indicating that mobilization of neutrophils does not effectively combat infection but contributes to development of lung lesions, probably due to release of oxygen-derived free radicals and hydrolytic enzymes. Neutrophil depletion prior to inoculation with P. haemolytica protected calves from the development of gross fibrinopurulent pneumonic lesions, although less severe inflammatory changes still occurred (3, 25). Thus, the neutrophil-mediated inflammatory response itself appears to be a major determinant of P. haemolytica pathogenicity, and identification of the mechanisms whereby P. haemolytica infection induces extensive neutrophil infiltration and degranulation is crucial to understanding the pathogenesis of pneumonic pasteurellosis.

LKT is believed to be the major virulence factor of P. haemolytica responsible for activation of bovine neutrophils in the development of pneumonic pasteurellosis. In contrast to P. haemolytica lipopolysaccharide, which causes vascular injury (reviewed in reference 28) but is not toxic to bovine neutrophils (10), LKT is specifically cytolytic to ruminant leukocytes and platelets. Stimulation of bovine neutrophils in vitro results in rapid leakage of intracellular K+ and cell swelling (7), increase of intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) (23), degranulation (11), generation of free oxygen radicals (18), and production of lipid inflammatory mediators such as LTB4, which has been implicated as an important chemotactic agent for bovine neutrophils (15) in P. haemolytica infection (5).

Previous studies have indicated that LKT-induced LTB4 synthesis involves Ca2+-dependent activation of cPLA2 (27). Although P. haemolytica LKT may also induce activation of 5-lipoxygenase, the enzyme complex responsible for oxidizing AA to leukotrienes, cPLA2-mediated AA release appears to be the rate-limiting step in the process of LKT-induced LTB4 synthesis. In the presence of exogenous AA, LKT induces substantial production of LTB4 (6), whereas inhibition of cPLA2 in the absence of exogenous AA causes marked inhibition of LTB4 synthesis (27).

Calcium-dependent translocation of cPLA2 from the cytosol to cell membranes and protein kinase-mediated phosphorylation are considered to be important mechanisms involved in the regulation of cPLA2 activity (4, 16). The results of previous experiments investigating LKT-induced effects on cPLA2 activity in the presence or absence of extracellular Ca2+ have supported an important signal transduction role for Ca2+ (27). However, it is not clear whether the regulatory effects of [Ca2+]i are restricted to direct effects on cPLA2 or whether other enzymes may be involved. Indeed, in human neutrophils, PLD is crucial to full expression of cPLA2 hydrolytic activity. PLD is ubiquitous in resting neutrophils, but in stimulated cells it concentrates in the plasma membrane (19), where it specifically hydrolyzes phosphatidylcholine to yield PA and choline. PA is further metabolized by phosphatidate phosphohydrolase to diglycerides (DG) (13). When intact human neutrophils were primed with tumor necrosis factor alpha and stimulated with N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe, AA release occurred in parallel with enhanced PA and DG formation (1). Therefore, in human neutrophils, PLA2 activity is induced by the products of PLD catalysis. Similar results have been reported for studies using rat neutrophils (14).

The results of the present study provide strong evidence that LKT-induced activation of PLA2 is mediated by PLD, principally via calcium-dependent production of PA. Although it is possible that PA promotes PLA2 activity by serving as a substrate, the experiments involving ethanol inhibition of PA production and addition of exogenous PA indicated that production of PA by PLD stimulates hydrolysis of [3H]AA-labeled phospholipid substrate. This effect of PA is consistent with its many regulatory influences on an array of neutrophil functions, such as neutrophil production of free oxygen radicals, degranulation, and phagocytosis (reviewed in reference 22). Indeed, PA is considered an important intracellular lipid messenger in many signaling pathways and may facilitate transport of extracellular Ca2+ across the plasma membrane as well as mobilization of [Ca2+]i (reviewed in reference 12). Furthermore, studies have indicated that PA can stimulate protein kinase C (PKC) and mitogen-activating protein kinase activities, both of which may be involved in phosphorylation of cPLA2. Also, PA is an anionic phospholipid that may alter the physical properties of cell membranes in such a way that cPLA2 activity can be influenced. Thus, there are several mechanisms whereby PA can regulate cPLA2 activity that do not involve serving as a substrate for AA production.

The mechanisms whereby PLD itself is regulated include phospholipase C-mediated activation of PKC, the small G proteins of the ADP-ribosylation factor and Rho families, and fluxes in [Ca2+]i (12, 22). Both in vivo and in vitro studies have indicated that activation of PLC generates DG and inositol triphosphate. The production of DG and resulting increase in [Ca2+]i caused by inositol triphosphate-mediated mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ activate PKC, which in turn activates PLD directly or indirectly via the G proteins. However, the results of the present study suggest a more direct role of Ca2+, possibly via influx of extracellular Ca2+ through pores in the plasma membrane caused by LKT. Further support for a more direct role of Ca2+ can be found in observations that PLD can be activated by agonists that act via G proteins without the involvement of PKC and that chelation of Ca2+ will inhibit activation of PLD by these agonists (13), thus suggesting that Ca2+ may exert direct control on PLD activity.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bauldry S A, Wooten R E. Induction of cytosolic phospholipase A2 activity by phosphatidic acid and diglyceride in permeabilized human neutrophils: interrelationship between phospholipase D and A2. Biochem J. 1997;322:353–363. doi: 10.1042/bj3220353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bligh E G, Dyer W J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem. 1959;37:911–923. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breider M A, Walker R D, Hopkins F M, Schultz T W, Bowerstock T L. Pulmonary lesions induced by Pasteurella haemolytica in neutrophil sufficient and neutrophil deficient calves. Can J Vet Res. 1988;52:205–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark J D, Lin L L, Kriz R W, Ramesha C S, Sultzman L A, Lin A Y, Milona N, Knopf J L. A novel arachidonic acid-selective cytosolic PLA2 contains a Ca2+-dependent translocation domain with homology to PKC and GAP. Cell. 1991;65:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90556-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke C R, Lauer A K, Barron S J, Wyckoff J H., III The role of eicosanoids in the chemotactic response to Pasteurella haemolytica infection. J Vet Med Ser B. 1994;41:483–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1994.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinkenbeard K D, Clarke C R, Hague C M, Clinkenbeard P, Srikumaran S, Morton R J. Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin-induced synthesis of eicosanoids by bovine neutrophils in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:644–649. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.5.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinkenbeard K D, Mosier D A, Confer A W. Effects of Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin on isolated bovine neutrophils. Toxicon. 1989;27:797–804. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(89)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinkenbeard K D, Upton M L. Lysis of bovine platelets by Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin. Am J Vet Res. 1991;52:453–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collier J R, Brown W W, Chow T L. Microbiologic investigation of natural epizootics of shipping fever of cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1962;140:807–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Confer A W, Simons K R. Effects of Pasteurella haemolytica lipopolysaccharide on selected functions of bovine leukocytes. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47:154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czuprynski C J, Noel E J, Ortiz-Carranza O, Srikumaran S. Activation of bovine neutrophils by partially purified Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3216–3133. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3126-3133.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.English D, Cui Y, Siddiqui R A. Messenger function of phosphatidic acid. Chem Phys Lipids. 1996;80:117–132. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(96)02549-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Exton J H. Phospholipase D: enzymology, mechanisms of regulation, and function. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:303–320. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita K, Murakami M, Yamashita F, Ammiya K, Kudo I. Phospholipase D is involved in cytosolic phospholipase A2-dependent active release of arachidonic acid by fMLP-stimulated rat neutrophils. FEBS Lett. 1996;395:293–298. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heidel J R, Taylor S M, Laegreid W W, Silflow R M, Liggitt H D, Leid R W. In vivo chemotaxis of bovine neutrophils induced by 5-lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic and eicosapentaenoic acid. Am J Pathol. 1989;143:671–676. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin L L, Wartmann M, Lin A Y, Knopf J L, Seth A, Davis R J. cPLA2 is phosphorylated and activated by MAP kinase. Cell. 1993;72:269–278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90666-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez A, Maxie M G, Ruhnke L, Savan M, Thomson R G. Cellular inflammatory response in the lungs of calves exposed to bovine viral diarrhea virus, Mycoplasma bovis, and Pasteurella haemolytica. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47:1283–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maheswaran S K, Weiss D J, Kannan M S, Townsend E L, Reddy K R, Whiteley L O, Srikumaran S. Effects of Pasteurella haemolytica A1 leukotoxin on bovine neutrophils: degranulation and generation of oxygen-derived free radicals. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1992;33:51–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(92)90034-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan G P, Sengelov H, Whatmore J, Borregaard N, Cockcroft S. ADP-ribosylation-factor-regulated phospholipase D activity localizes to secretory vesicles and mobilizes to the plasma membrane following N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenyalanine stimulation of human neutrophils. Biochem J. 1997;325:581–585. doi: 10.1042/bj3250581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy G L, Whitworth L C, Clinkenbeard K D, Clinkenbeard P A. Hemolytic activity of the Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3209–3212. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3209-3212.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Needleman P, Turk J, Jakschik B A, Morrison A R, Lefkowith J B. Arachidonic acid metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:69–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olson S C, Lambeth J D. Biochemistry and cell biology of phospholipase D in human neutrophils. Chem Phys Lipids. 1996;80:3–19. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(96)02541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortiz-Carranza O, Czuprynski C J. Activation of bovine neutrophils by Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin is calcium dependent. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;52:558–564. doi: 10.1002/jlb.52.5.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramesha C S, Taylor L A. Measurement of arachidonic acid release from human polymorphonuclear neutrophils and platelets: comparison between gas chromatographic and radiometric assays. Anal Biochem. 1991;192:173–180. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slocombe R F, Malark J, Derksen F J, Robinson N E. Importance of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of acute pneumonic pasteurellosis in calves. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:2253–2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker R D, Hopkins F M, Schultz T W, McCracken M D, Moore R N. Changes in leukocyte populations in pulmonary lavage fluids of calves after inhalation of Pasteurella haemolytica. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:2429–2433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z, Clarke C R, Clinkenbeard K D. Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin induced increase in phospholipase A2 activity in bovine neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1885–1890. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.1885-1890.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whiteley L O, Maheswaran S K, Weiss D J, Ames T R, Kannan M S. Pasteurella haemolytica A1 and bovine respiratory disease: pathogenesis. J Vet Intern Med. 1992;6:11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1992.tb00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yates W D G. A review of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis shipping fever pneumonia and viral-bacterial synergism in respiratory disease of cattle. Can J Comp Med. 1982;46:225–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]