Abstract

Introduction

Hypertension is one of the major co-morbidities affecting older Indians, though current trends show that it is increasingly being diagnosed in younger adults as well. In elderly members of the population, it has been shown to be associated with other co-morbidities, making its management difficult. Among the issues that have arisen with its treatment is the increased prevalence of polypharmacy. Thus, there is a need to identify the issues arising from this increase in medications. In particular, the patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL) can be assessed and interpreted to ensure only appropriate polypharmacy is practiced.

Methods

The adjusted Research and Development (RAND) 36-Item Health Survey 1.0 for health-related quality of life was sent to a consecutive sampling of 100 hypertensive patients at a rural tertiary care hospital in Wardha District. They were all clinically diagnosed with hypertension and had been prescribed allopathic medication for the same. They were instructed to answer all the questions to the best of their abilities, and each question was then scored from 0 to 100. In addition, they were given questions regarding their age, sociodemographic details, number of medications and frequency of dosage, and additional co-morbidities. The independent variable, i.e., the number of medications (polypharmacy), was then compared to the physical and mental scores they received on the 36-Item Short Form survey (SF-36) to see if there was an association between the two.

Result

The patients with hypertension that satisfied the criteria for polypharmacy scored lower in the Physical Component Score (PCS) of the HRQoL with a mean difference of 10.4 points. This is a significant value, and when studied in a multivariate linear regression model, controlling for the covariates mentioned above, indicated a statistically significant and negative association between the number of medications and adjusted PCS scores (β = −5.437, p<0.05, 95% CI −8.392 to −2.482). In regards to the Mental Component Score (MCS) of the HRQoL, a difference of 3.72 points was observed unadjusted and, upon controlling for covariates, it was found to be statistically significant (β = −2.825, p<0.05, 95% CI −5.300 to −0.351).

Conclusion

There is a negative correlation between HRQoL and polypharmacy in hypertensive patients. This is especially evident in the physical aspect, as can be inferred from the Physical Component Scores attained in the study. A smaller but still significant negative correlation is seen in the mental component as well. Hence, a change of policy is indicated to idealize prescriptions and physicians must be vigilant about inappropriate polypharmacy.

Keywords: sf-36, comorbidities, polypharmacy, health-related quality of life, hypertension

Introduction

The complications of hypertension remained the leading killer globally in 2020, with an estimated death toll of more than 10 million worldwide. The majority of hypertension management guidelines recommend that the diagnosis of hypertension be made at or above 140 mm Hg for systolic blood pressure, above 90 mm Hg for diastolic blood pressure, or both [1,2]. Due to the gradual development of stiffness in arterial walls and modifications in the compliance of arteries, hypertension has a disproportionate effect on elderly people. Evidence indicates that this is primarily due to the environmental and lifestyle changes that the modern world has afforded us [3]. Hypertension is very much on the rise, especially in developing countries with an income at the middle and lower end of the scale [4]. In 2019, it was reported that in India, approximately 29.8% of people suffered from increased blood pressure. The gap between rural and urban afflicted was also found to be narrowing as diet and lifestyle changes were altered [5]. As it is a multifactorial disease, this increase in cases could be attributed to both genetic as well as environmental risk factors [6].

There are several classes of drugs that can be used to manage hypertension, each of them tailored to different patients’ needs. A physician might prescribe one or more of the following classes of drugs at their discretion: beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics, calcium channel blockers, etc. [7].

Modern medicine has heralded a slew of medical innovations that have revolutionized disease treatment in patients, not only in the treatment of hypertension but other conditions as well. The increasing number of developed drug classes has benefited mankind immensely, but when faced with the problem of multi-morbidity, has also increased the chances of inappropriate polypharmacy. The guidelines of pharmacy were initially framed for only single morbidities and, in the wake of multi-morbidity, they are having to be reassessed [8]. These co-morbidities encompass the common ones such as stroke, coronary artery disease, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, while the uncommon ones include rheumatic and psychiatric ailments. Diabetes is also common among elderly patients suffering from hypertension and requires careful monitoring by the physician to ensure adequate care is given to the patient. Ultimately, these ailments need to be treated as well as hypertension, and hence arises the problem of polypharmacy [1].

Now, while the definition of multi-morbidity has been accepted nearly universally as the simultaneous sufferance of two or more chronic health conditions, polypharmacy definitions are more variable [9]. A 2017 review of polypharmacy definitions stated that there were several definitions for polypharmacy, including both numerical and therapeutic definitions [10]. For this article, keeping in mind that the patients will all be hypertensive, we will consider polypharmacy to be the use of three or more medications in the long term, i.e., greater than 240 days in a year [10,11]. Polypharmacy has been increasingly seen in elderly patients due to an increased life expectancy and a subsequent ‘accumulation’ of chronic health conditions. With each additional co-morbidity comes the need for a new or adjusted treatment plan, often including multiple drugs or drug classes several times a day. Pressure on doctors to adhere to disease-specific guidelines tailored to a single illness without considering multi-morbidity also contributes to the increased prevalence of polypharmacy [8,12].

The common negative effects associated with polypharmacy include drug-drug interactions; adverse drug interactions; increased healthcare costs and duration of hospitalization; increased risk of falls; frailty; disability; and patient non-adherence [13]. The last need not be intentional as forgetfulness was found to be a major reason for patients' non-adherence, especially in the elderly who are oftentimes on multiple medications [14-16]. In addition, there is a negative impact on the healthcare system; reduced physician productivity; a risk of medication errors; and an increased burden on the system itself [13]. As such, there is a need for a reduction in the inappropriate prescription of drugs, and in this vein, there have been studies evaluating the possibility of doing just that [17].

However, it is important to note that polypharmacy in itself is not harmful; rather, it is inappropriate polypharmacy that is associated with common adverse effects. Oftentimes, multiple medication classes are needed to treat a patient’s multiple morbidities. Hence, any drug interactions, adverse or side effects are the lesser of two evils when compared to the patient's initial condition [12]. Ergo, there is a need to consider not only the number of medications but also the additional chronic conditions a patient might be suffering from.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a term indicative of the general quality of a patient’s life in regard to their physical and mental health [18]. It is usually assessed by questionnaires that may be of a generic or specific variety. The latter is tailored to a specific group that is to be assessed, while the former includes the SF-36 and EuroQol (EQ-5D), among others [19,20]. The adjusted SF-36 questionnaire is the one used in this article. It contains 36 questions that measure 8 variables, encompassing both physical and mental well-being, and has been found to be effective in its assessment [21].

With consideration of the above points, it appears that polypharmacy and its association with quality of life are not entirely understood. This study serves to provide better insight into the necessity of guidelines for "appropriate polypharmacy" and to understand what, if any, association is present between polypharmacy and HRQoL.

Previous studies have mostly shown a negative impact of polypharmacy on HRQoL, though they have all been conducted in other countries [7,14,22-24]. There appears to be only one similar study conducted in India, that of Koshy et al., where the quality of life of psychiatric patients undergoing polypharmacy was contrasted with that of those undergoing monotherapy [25]. There is no similar study based in India relating to hypertensive patients or those with cardiovascular indications. Thus, with the lack of prior studies conducted in India, there was a need for this topic to be considered.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study is a cross-sectional type of observational study. The data obtained were from questionnaires sent out to patients in a rural tertiary care hospital in the Wardha district. The questionnaires used included the adjusted research and development (RAND) 36-Item Health Survey 1.0 as well as a few additional questions to establish sociodemographic characteristics. Furthermore, it included questions regarding additional comorbidities and the number of medications being taken by the patient per day based on their reporting.

Study population

The population was sampled as a consecutive sampling from the medicine OPD of a rural tertiary care hospital in Wardha District. The duration of the study was two months and a sample size of 100 patients' data was collected.

The inclusion criteria for patient selection were: (1) the patient should be above 18 years of age and should be mentally capable of providing consent; (2) the patient should be a medically diagnosed patient with hypertension (by AHA guidelines, with measures greater than 140/90 mm Hg on three separate visits with a one-to-four-week difference between each); and (3) the patient should be taking allopathic medicine for the management of hypertension for a period greater than three months.

The exclusion criteria for patient selection were (1) patients who don’t consent/are unable to consent; (2) patients who cannot comprehend the questions; and (3) patients with terminal or immediately life-threatening conditions.

Informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to their enrolment in the study. Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Ethics Committee, D.M.I.M.S. (D.U.) and the IRB approval number is DMIMS(DU)/IEC/2021/600.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this study is the health-related quality of life of the patient. It is measured with the RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0, adjusted for the Indian audience. This questionnaire has been shown to be effective and is widely used in both chronic conditions and general quality-of-life studies [21,24,26]. It is a generic questionnaire that measures eight concepts of health. Each question is scored from 0% to 100% (adjusted based on the number of options), with 0% being the lowest and 100% being the highest. The SF-36 provides three scores. The Physical Component Scores (PCSs) encompass the concepts of physical functioning, bodily pain, role limitations due to physical health problems, and general health. The mental component scores include role limitations due to emotional problems, emotional well-being, energy/fatigue, and social functioning. The last score is that of the total HRQoL score, which includes all eight concepts [27].

Independent variable

The main independent variable in this study is the number of medications being taken by a patient. We believe that as the number of drugs increases, there will be a subsequent decrease in HRQoL, thus implying that there is a negative correlation between the two. For this article, we assume polypharmacy to be taking three or more medications daily for a period greater than 240 days in a year. We asked each patient to enumerate the maximum number of drugs they are taking in a single day and compare it to the reported and calculated HRQoL. As the inclusion criteria only specify hypertension, we included a question about any additional comorbidities as well.

Other independent variables that could inadvertently affect the dependent variable, i.e., HRQoL, include sociodemographic characteristics and health-related information as mentioned below.

We collected sociodemographic information, including age, gender, and urban or rural area of residence. Additional comorbidities (they were asked for the number and to specify) and habits like smoking, alcohol use, exercise, and body mass index were included in health-related information.

By including these data when considering the results, we avoided drawing inaccurate conclusions about the reasons behind the change in HRQoL by controlling for these factors.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was first used to profile the population sample. Chi-Square tests were then used to test the hypothesis of an association between polypharmacy groups and independent variables. The PCS, Mental Component Score (MCS), and HRQoL were calculated. An unadjusted association between PCS and MCS scores and polypharmacy was studied with F tests. A multivariate linear regression model with a forward selection of variables was used to assess the association of the scores with polypharmacy after controlling for the covariates mentioned above. Initially, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for the normality of the distribution, and it was found to be non-normal. Hence, Tukey’s Ladder of Power for transformations was used. In this study, square root values were used for transformation in the multivariate regression model. Multicollinearity was assessed with the variance inflation factor. The square of the multiple correlation coefficient (R-square) value improved, allowing the assessment of the goodness of fit of the model. The study findings were considered statistically significant for a p-value less than 0.05.

All statistical analysis was performed with the help of the Statistical Package for Social Services (SPSS) (version 28, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and Microsoft Excel (2019, Microsoft® Corp., Redmond, WA).

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the study population

A total of 100 respondents’ data were analyzed for this study as they responded and consented to the same. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample population. The population was mostly urban dwellers (71%). Further, there were 54 male and 46 female respondents, with a majority being above 50 years of age (73%). The majority of the population had a BMI within the normal (35%) and overweight (43%) categories and a slightly lower propensity towards regular exercise (43%). Most did neither smoke nor consume alcohol regularly, but 10% were regular smokers, and 33% drank alcohol regularly. Regarding their self-reported health, 3% reported excellent health, but the majority claimed good or very good health; 3% reported poor health and 18% fair health; 43% of the population reported at least one comorbidity. In terms of medication, polypharmacy was seen in 63% of the population.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of the Study Population.

| Sl. No. | Characteristic | Percentage (%) (participants(n)=100) |

| 1 | Age | |

| <50 years | 27% | |

| >50 years | 73% | |

| 2 | Gender | |

| Male | 54% | |

| Female | 46% | |

| 3 | Body mass index | |

| Underweight | 3% | |

| Normal | 35% | |

| Overweight | 43% | |

| Obese | 19% | |

| 4 | Exercise | |

| >3 hours per week | 43% | |

| <3 hours per week | 57% | |

| 5 | Region | |

| Urban | 71% | |

| Rural | 29% | |

| 6 | Smoking and/or alcohol | |

| Both | 8% | |

| Neither | 65% | |

| Alcohol | 25% | |

| Smoking | 2% | |

| 7 | Additional co-morbidity (at least 1) | |

| Yes | 43% | |

| No | 57% | |

| 8 | Self-reported health | |

| Excellent | 3% | |

| Very good | 37% | |

| Good | 39% | |

| Fair | 18% | |

| Poor | 3% | |

| 9 | Number of medications daily | |

| Less than 3 | 37% | |

| 3 or more | 63% | |

Chi-square test findings

Chi-square statistics were used to test the hypothesis of an association between polypharmacy groups and independent variables (Table 2). A confidence interval of 95% (p<0.05) was considered to be statistically significant. Among the characteristics of the population, age and habits like smoking and alcohol consumption were found to be statistically significant, as was gender, with males showing a higher propensity for polypharmacy. Region and BMI were not statistically significant; however, lack of regular exercise and the presence of comorbidities were significantly associated with polypharmacy.

Table 2. Chi-Square Tests Findings.

Please note that a p-value of less than 0.05 is taken as statistically significant.

| Variables | Total | No polypharmacy | Polypharmacy | p-Value |

| Total | 100 | 37 | 63 | |

| Age | ||||

| <50 | 27 | 5 | 22 | p<0.05 |

| >50 | 73 | 32 | 41 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 46 | 9 | 37 | p<0.05 |

| Male | 54 | 28 | 26 | |

| Body mass index | ||||

| Underweight | 3 | 1 | 2 | p=0.9452 |

| Normal | 35 | 13 | 22 | |

| Overweight | 43 | 17 | 26 | |

| Obese | 10 | 6 | 13 | |

| Exercise | ||||

| >3 hours per week | 43 | 25 | 18 | p<0.05 |

| <3 hours per week | 57 | 12 | 45 | |

| Region | ||||

| Urban | 71 | 29 | 42 | p=0.2127 |

| Rural | 29 | 8 | 21 | |

| Smoking and/or alcohol | ||||

| Both | 8 | 5 | 3 | p<0.05 |

| Neither | 65 | 19 | 46 | |

| Alcohol | 25 | 13 | 12 | |

| Smoking | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Co-morbidity | ||||

| Yes | 43 | 25 | 18 | p<0.05 |

| No | 57 | 12 | 45 | |

Health-related quality of life findings based on the adjusted RAND 36-item health survey 1.0

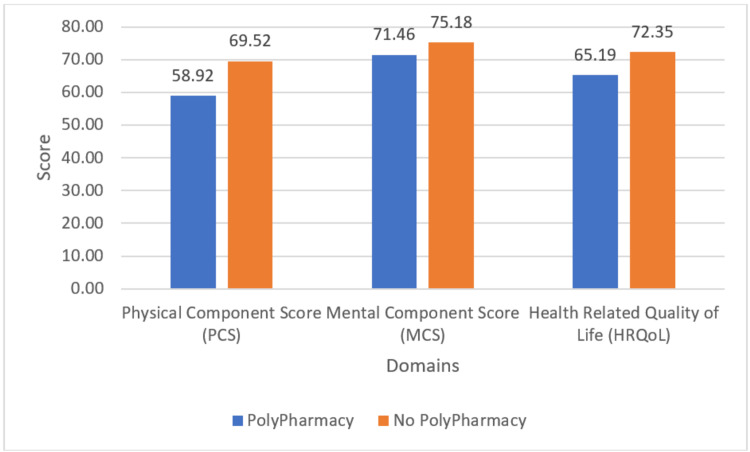

When assessing the aggregate scores of the PCS, MCS, and HRQoL, the scores of patients with and without polypharmacy showed a stark disparity (Figure 1). The average MCS score of patients with polypharmacy is nearly 4 points below that of those with polypharmacy, while the average PCS of patients without polypharmacy was greater than 10 points more than the same for those with polypharmacy, which is a substantial amount. The HRQoL also showed a significant disparity, with patients on multiple medications scoring over 7 points less than the average scores of the rest.

Figure 1. Mean Health-Related Quality of Life Components Scores.

The mean scores in the individual domains also showed disparity with and without polypharmacy as seen in Table 3. The largest difference can be inferred from physical functioning (difference of 14), role limitation due to physical functioning (difference of 8), and general health (difference of 8). A lesser difference is seen in the other domains, with role limitation due to emotional problems showing a difference of less than 1. However, all the domains show a higher mean score in patients who do not have polypharmacy.

Table 3. Mean Score of Individual Domains of Health-Related Quality of Life.

| Domains | Mean ± standard deviation | |

| Physical functioning | Polypharmacy | 56.76±22.86 |

| No polypharmacy | 70.32±29.18 | |

| Role limitations due to physical health | Polypharmacy | 62.16±32.55 |

| No polypharmacy | 70.37±35.47 | |

| Emotional well being | Polypharmacy | 68.51±14.09 |

| No polypharmacy | 73.81±17.41 | |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | Polypharmacy | 79.28±26.47 |

| No polypharmacy | 79.89±33.08 | |

| Energy/fatigue | Polypharmacy | 67.57±17.70 |

| No Polypharmacy | 70.95±20.85 | |

| Social functioning | Polypharmacy | 67.57±23.47 |

| No polypharmacy | 75.00±24.59 | |

| General health | Polypharmacy | 59.28±15.65 |

| No polypharmacy | 67.33±18.61 | |

Multivariate linear regression model findings

Adjusted PCS and MCS associations, controlling for covariates, were found with the multivariate linear regression model (Table 4). Estimates of the multivariable linear regression model indicated a statistically significant and negative association between the number of medications and adjusted PCS scores (β = −5.437, p<0.05, 95% CI −8.392 to −2.482). In regards to MCS, the association was not found to be statistically significant (p = 0.152) initially, but upon controlling for covariates, it was found to be statistically significant (β = −2.825, p<0.05, 95% CI −5.300 to −0.351). Upon adjusting for covariates, the model was found to be improved.

Table 4. Multivariate Linear Regression Model Findings.

Please note that a p-value of less than 0.05 is taken as statistically significant.

| Variable | β-coefficient | p-value | 95% confidence interval for β | |

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||

| Physical Component Score (unadjusted) | −4.039 | p<0.05 | −7.038 | −1.04 |

| Physical Component Score (adjusted) | −5.437 | p<0.05 | −8.392 | −2.482 |

| Mental Component Score (unadjusted) | −1.803 | p=0.152 | −4.282 | 0.675 |

| Mental Component Score (adjusted) | −2.825 | p<0.05 | −5.3 | −0.351 |

Discussion

This study examines the association between polypharmacy and health-related quality of life in patients with hypertension while accounting for covariates such as sociodemographic factors and the presence of comorbidities. The sociodemographic factors considered were age, gender, BMI, exercise, region of residence, alcohol consumption, and smoking. The study population consisted of a consecutive sampling of patients in the medicine OPD of a rural tertiary care hospital in Wardha District with diagnosed hypertension and prescribed allopathic medication for its management. Of the given factors: age, gender, alcohol and smoking habits, and regular exercise were found to have a statistically significant association. The presence of comorbidities was also found to be statistically significant. Among the total population, 63% were found to have polypharmacy for the given definition, i.e., three or more medications daily for a period greater than 240 days in a year. As expected, there was a significant increase in the number of medications with comorbidities. In addition, there was a lowered HRQoL score for patients with multi-morbidity. This is in line with previous studies [7,14,22-24] and is only logical, given that multiple medications would be required to treat a variety of conditions.

The PCS and MCS were then calculated for each subject in accordance with the adjusted RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0 [27]. Both the average calculated scores showed a disparity between patients having polypharmacy and those not having polypharmacy. The average MCS showed an increase of 4 points for patients without polypharmacy, though this was not seen as statistically significant until the scores were adjusted for covariates. In regards to the PCS, there was a difference of 10.6 points in the average scores of those having polypharmacy and those not. When adjusted for covariates, the difference was reduced slightly but remained statistically significant. The aggregate score of PCS and MCS, the health-related quality of life, also indicated a statistically significant negative correlation between polypharmacy and HRQoL, both unadjusted and later when adjusted for covariates. The results obtained in this study are in line with and expected, given prior studies conducted in Greece and the United States of America [7,14,22-24].

In regards to the individual domains tested by the SF-36, all domains showed a mean score higher in patients not having polypharmacy. The largest differences, as indicated by the PCS scores, were in physical functioning and role limitation due to physical functioning, while there is only a slight rise in the parallel scores of MCS.

The results of the study are indicative that polypharmacy may lead to a worsening in physical ability that can be attributed, perhaps, to the increased drug-drug interactions, adverse drug reactions, frailty, and disability that are often associated with it [13]. The affected mental component score can be associated with increased healthcare costs and duration of hospitalization as well as the patient’s negative outlook on the implications of taking multiple pills [13], though the latter is to a lesser degree. With these results in mind, it prompts doctors to adjust their prescriptions, weighing the risk of adverse drug reactions with that of symptomatic control. Appropriate polypharmacy is the ideal solution to this problem, and doctors must be mindful of the same in their prescriptions, especially when treating multi-morbidity. Further, it calls for a policy change. Guidelines that were earlier made for single diseases need to be adjusted to account for multi-morbidity and the accumulation of conditions that occur in elderly patients, especially for common co-morbidities. A multidisciplinary patient-centered approach would also be an asset, as found in some studies [28]. Further research into that avenue might yield useful information.

This study is limited in that it was based on the self-reporting of patients through a questionnaire, which poses the risk of recall bias, which was combated by requesting data dating no further than four weeks prior. Given the anonymity afforded to the patients, it eliminates social desirability bias. Furthermore, the presence of either multi-morbidity or more severe disease may skew the quality-of-life score, with patients having a poor quality of life due to their health conditions being attributed instead to the number of medications they are taking. This could be possible as the more ill patients would also be taking a greater number of medicines. An attempt to prevent skewing of data in this regard was made by eliminating patients with terminal or immediately life-threatening conditions. Lastly, the sample size of the population and the duration of the study were low. Hence, further research is encouraged to supplement these findings. However, this study serves as a starting point.

Conclusions

Despite the mentioned limitations, the study postulates an association between the physical component of HRQoL and, to a lesser extent, the mental component of the same in patients with hypertension. Further studies are required to emphasize these findings as well as to diversify the knowledge in conditions other than hypertension as this study has attempted.

Having already seen the adverse impacts in previous studies, that of drug-drug interactions, adverse drug interactions, increased healthcare costs and duration of hospitalization, increased risk of falls, frailty, disability, and patient non-adherence, this study quantifies the reduction in physical ability and role limitation due to physical frailty. These results prompt a change in policy with regard to the treatment of multi-morbidity such that the physician has a clear set of guidelines to follow. This is especially evident in hypertension as nearly half the sample size considered exhibited at least one co-morbidity. We hope that more physicians keep these results in mind in their prescribing to provide the best care to their patients.

Appendices

Table 5 shows the questionnaire used in our study. It is an adjusted RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0 for Health-Related Quality of Life.

Table 5. Questionnaire for Health-Related Quality of Life.

| Question | Option |

| Do you consent to have the information you provide below used for the purpose of research (all details will be anonymised before publication)? | Yes |

| No | |

| If you select agree, you are confirming that you are a medically diagnosed hypertension patient and are currently taking allopathic medication for the same. | Agree |

| Disagree | |

| Age | (in years) |

| Gender | Male |

| Female | |

| Area of residence | Urban |

| Rural | |

| Do you partake in either smoking or alcohol consumption? | Smoking |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| Both | |

| Neither | |

| Weight | (in kg) |

| Height | (in cm) |

| Do you exercise more than 3 hours weekly? | Yes |

| No | |

| Number of allopathic medications being taken daily | (name them) |

| Do you have any additional comorbidities besides hypertension? | (If yes, please specify which ones) |

| Section 1/5 | |

| In general, would you say your health is: | Excellent |

| Very good | |

| Good | |

| Fair | |

| Poor | |

| How true or false is the given statement for you- "I seem to get sick a little easier than other people" | Definitely true |

| Mostly true | |

| Don't know | |

| Mostly false | |

| Definitely false | |

| Do you expect your health to get worse? | Definitely yes |

| Probably yes | |

| Don't know | |

| Probably not | |

| Definitely not | |

| During the past 4 weeks, how much of the time has your physical health or emotional problems interfered with your social activities (like visiting friends, relatives, etc.)? | All of the time |

| Most of the time | |

| Some of the time | |

| A little of the time | |

| None of the time | |

| Section 2/5: The following items are about activities you might do during a typical day. Does your health now limit you in these activities? If so, how much? | |

| Vigorous activities, such as running, lifting heavy objects, participating in strenuous sports | Yes, limited a lot |

| Yes, limited a little | |

| No, not limited at all | |

| Moderate activities, such as moving a table, sweeping, gardening or doing household chores | Yes, limited a lot |

| Yes, limited a little | |

| No, not limited at all | |

| Climbing several flights of stairs | Yes, limited a lot |

| Yes, limited a little | |

| No, not limited at all | |

| Bending, kneeling, or stooping | Yes, limited a lot |

| Yes, limited a little | |

| No, not limited at all | |

| Walking more than 1.5 km | Yes, limited a lot |

| Yes, limited a little | |

| No, not limited at all | |

| Section 3/5: During the past 4 weeks, have you had any of the following problems with your work or other regular daily activities as a result of your PHYSICAL HEALTH? | |

| Accomplished less than you would like | Yes |

| No | |

| Had difficulty performing the work or other activities (for example, it took extra effort) | Yes |

| No | |

| Cut down the amount of time you spent on work or other activities | Yes |

| No | |

| Section 4/5: These questions are about how you feel and how things have been with you during the past 4 weeks. For each question, please give the one answer that comes closest to the way you have been feeling. How much of the time during the past 4 weeks? | |

| Have you felt calm & peaceful? | All of the time |

| Most of the time | |

| A good bit of the time | |

| Some of the time | |

| A little of the time | |

| None of the time | |

| Have you felt anxious and worried? | All of the time |

| Most of the time | |

| A good bit of the time | |

| Some of the time | |

| A little of the time | |

| None of the time | |

| Did you have a lot of energy? | All of the time |

| Most of the time | |

| A good bit of the time | |

| Some of the time | |

| A little of the time | |

| None of the time | |

| Have you felt upset and sad? | All of the time |

| Most of the time | |

| A good bit of the time | |

| Some of the time | |

| A little of the time | |

| None of the time | |

| Did you feel worn out? | All of the time |

| Most of the time | |

| A good bit of the time | |

| Some of the time | |

| A little of the time | |

| None of the time | |

| Have you been a happy person? | All of the time |

| Most of the time | |

| A good bit of the time | |

| Some of the time | |

| A little of the time | |

| None of the time | |

| Section 5/5: During the past 4 weeks, have you had any of the following problems with your work or other regular daily activities as a result of any EMOTIONAL PROBLEMS (such as feeling depressed or anxious)? | |

| Accomplished less than you would like | Yes |

| No | |

| Had difficulty performing the work or other activities (for example, it took extra effort) | Yes |

| No | |

| Cut down the amount of time you spent on work or other activities | Yes |

| No | |

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Institutional Ethics Committee, D.M.I.M.S. (D.U.) issued approval DMIMS(DU)/IEC/2021/600

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.2020 International Society of Hypertension Global hypertension practice guidelines. Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. Hypertension. 2020;75:1334–1357. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The top 10 causes of death. [ Aug; 2021 ]. 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death

- 3.Hypertension and drug adherence in the elderly. Burnier M, Polychronopoulou E, Wuerzner G. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:49. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The global epidemiology of hypertension. Mills KT, Stefanescu A, He J. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:223–237. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asian management of hypertension: current status, home blood pressure, and specific concerns in India. Sogunuru GP, Mishra S. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2020;22:479–482. doi: 10.1111/jch.13798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The hypertension pandemic: an evolutionary perspective. Rossier BC, Bochud M, Devuyst O. Physiology (Bethesda) 2017;32:112–125. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00026.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Association between polypharmacy and health-related quality of life among US adults with cardiometabolic risk factors. Vyas A, Kang F, Barbour M. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:977–986. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02377-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Current and future perspectives on the management of polypharmacy. Molokhia M, Majeed A. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18:70. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0642-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Multimorbidity: what do we know? What should we do? Navickas R, Petric VK, Feigl AB, Seychell M. J Comorb. 2016;6:4–11. doi: 10.15256/joc.2016.6.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:230. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The development of polypharmacy. A longitudinal study. Veehof L, Stewart R, Haaijer-Ruskamp F, Jong BM. Fam Pract. 2000;17:261–267. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appropriate polypharmacy and medicine safety: when many is not too many. Cadogan CA, Ryan C, Hughes CM. Drug Saf. 2016;39:109–116. doi: 10.1007/s40264-015-0378-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polypharmacy: evaluating risks and deprescribing. Halli-Tierney AD, Scarbrough C, Carroll D. http://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2019/0701/p32.html?utm_medium=email&utm_source=transaction. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assessing forgetfulness and polypharmacy and their impact on health-related quality of life among patients with hypertension and dyslipidemia in Greece during the COVID-19 pandemic. Souliotis K, Giannouchos TV, Golna C, Liberopoulos E. Qual Life Res. 2022;31:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02917-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assessment of compliance to treatment of hypertension and diabetes among previously diagnosed patients in urban slums of Belapur, Navi Mumbai, India. Kotian SP, Waingankar P, Mahadik VJ. Indian J Public Health. 2019;63:348–352. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_422_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Awareness, medication adherence, and diet pattern among hypertensive patients attending teaching institution in western Rajasthan, India. Mathur D, Deora S, Kaushik A, Bhardwaj P, Singh K. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9:2342–2349. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_193_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Effect of antihypertensive medication reduction vs usual care on short-term blood pressure control in patients with hypertension aged 80 years and older: the OPTIMISE randomized clinical trial. Sheppard JP, Burt J, Lown M, et al. JAMA. 2020;323:2039–2051. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Haraldstad K, Wahl A, Andenæs R, et al. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:2641–2650. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02214-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health-related quality of life and associated factors in functionally independent older people. Machón M, Larrañaga I, Dorronsoro M, Vrotsou K, Vergara I. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:19. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0410-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Measuring health-related quality of life. Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:622–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Short form 36 (SF36) health survey questionnaire: normative data for adults of working age. Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Wright L. BMJ. 1993;306:1437–1440. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6890.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Associations between polypharmacy, symptom burden, and quality of life in patients with advanced, life-limiting illness. Schenker Y, Park SY, Jeong K, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:559–566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04837-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Psychotropic polypharmacy and its association with health-related quality of life among cancer survivors in the USA: a population-level analysis. Vyas A, Alghaith G, Hufstader-Gabriel M. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:2029–2037. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SF36 is a reliable patient-oriented outcome evaluation tool in surgically treated degenerative cervical myelopathy cases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Wang WG, Dong LM, Li SW. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:7126–7137. doi: 10.12659/MSM.916764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.A cross-sectional comparative study on the assessment of quality of life in psychiatric patients under remission treated with monotherapy and polypharmacy. Koshy B, Gopal Das CM, Rajashekarachar Y, Bharathi DR, Hosur SS. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:333–340. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_126_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Comparison of performance of specific (SLEQOL) and generic (SF36) health-related quality of life questionnaires and their associations with disease status of systemic lupus erythematosus: a longitudinal study. Louthrenoo W, Kasitanon N, Morand E, Kandane-Rathnayake R. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22:8. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-2095-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Hays RD, Morales LS. Ann Med. 2001;33:350–357. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Effects of a clinical medication review focused on personal goals, quality of life, and health problems in older persons with polypharmacy: A randomised controlled trial (DREAMeR-study) Verdoorn S, Kwint HF, Blom JW, Gussekloo J, Bouvy ML. PLoS Med. 2019;16:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]