Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of early antiviral treatment in preventing clinical deterioration in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infected (COVID-19) patients in home isolation and to share our experiences with the ambulatory management of nonsevere COVID-19 patients. This retrospective study included mild COVID-19 adult patients confirmed by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. They received care via an ambulatory management strategy between July 2021 and November 2021. Demographic data, clinical progression, and outcomes were collected. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were performed to illustrate the cohort’s characteristic and outcomes of the study. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were employed to investigate the associations between clinical factors and disease progression. A total of 1940 patients in the Siriraj home isolation system met the inclusion criteria. Their mean age was 42.1 ± 14.9 years, with 14.2% older than 60 years, 54.3% female, and 7.1% with a body weight ≥ 90 kg. Only 115 patients (5.9%) had deterioration of clinical symptoms. Two-thirds of these could be managed at home by dexamethasone treatment under physician supervision; however, 38 of the 115 patients (2.0% of the study cohort) needed hospitalization. Early favipiravir outpatient treatment (≤ 5 days from onset of symptoms) in nonsevere COVID-19 patients was significantly associated with a lower rate of symptom deterioration than late favipiravir treatment (50 [4.6%] vs 65 [7.5%] patients, respectively; P = .008; odds ratio 1.669; 95% confidence interval, 1.141–2.441). The unfavorable prognostic factors for symptom deterioration were advanced age, body weight ≥ 90 kg, unvaccinated status, higher reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction cycle threshold, and late favipiravir treatment. The early delivery of essential treatment, including antiviral and supervisory dexamethasone, to ambulatory nonsevere COVID-19 patients yielded favorable outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand.

Keywords: ambulatory, COVID-19, dexamethasone, early treatment, Favipiravir, Thailand

1. Introduction

Since the initial outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in late 2019, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has become a major global public health problem. As at August 26, 2022, there were 596,873,121 confirmed cases and 6,459,684 deaths. The pandemic has come in waves, with each surge critically impacting public health systems. Its effects include reduced patient access to healthcare systems, insufficient medications for patient treatment, hospital bed shortages, and inadequate numbers of healthcare personnel. The broad spectrum of clinical manifestations in COVID-19 patients ranges from asymptomatic to severe, with a death rate of 1.08%. Most COVID-19 patients have mild symptoms that can be managed at home. Therefore, new patient care strategies, such as field hospitals and home quarantine with an ambulatory care system, have been established to ameliorate the challenges to healthcare systems during the crisis.[1,2]

The Delta variant wave of COVID-19 in Thailand started to surge in July 2021. As with other countries, the Thai healthcare system was subsequently overwhelmed by enormous numbers of patients, resulting in shortages in therapeutic resources. Most patients had mild disease symptoms that could be managed in an ambulatory care setting, for example, anosmia, rhinorrhea, sore throat, cough, and fever.[3] The Department of Medical Services of Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health issued guidelines for patient treatment in ambulatory-care settings, such as state quarantine facilities and field hospitals. Later, on July 1, 2021, guidelines on how healthcare professionals manage patients with COVID-19 in home isolation were issued. They were promptly and enthusiastically adopted by healthcare personnel. The criteria for home isolation were flexible in that they were based on physicians’ judgments about patient safety and disease control.[4]

The treatment options for COVID-19 have been extensively investigated during the pandemic. Most options are indicated for patients with moderate or severe symptoms. The well-established treatments for asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients include nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), sotrovimab, remdesivir, and molnupiravir.[5] However, in mid-2021, none of these medications were available in Thailand except remdesivir, which was reserved for patients with moderate to severe symptoms.[6]

Favipiravir is an oral, broad-spectrum, antiviral agent approved for treating influenza viruses in Japan and China. It exhibits antiviral activity across a wide range of ribonucleic acid viruses.[7] This antiviral drug was available in Thailand and was one of the most appropriate for treating COVID-19, according to evidence at that time. Previous studies reported that treating patients with favipiravir within 10 days of symptom onset appeared to shorten both the time to clinical improvement[8–10] and the viral clearance time compared with patients administered lopinavir/ritonavir.[11] Thus, favipiravir was recommended as a first-line antiviral therapy for COVID-19 patients in Thailand.[6]

The clinical manifestations of COVID-19 typically start with fever or upper respiratory tract symptoms. Some patients progress to COVID-19 pneumonia, appearing around days 4 to 6 after the onset of symptoms, and develop dyspnea on day 8. The presence of underlying diseases (such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and obesity) and advanced age are risk factors for severe illness.[12] There is evidence that antiviral therapy should be started early after the appearance of symptoms to prevent the spread of the SARS-COV-2 virus into the respiratory tract, endothelium, and neurons. This approach can forestall the development of pneumonia and complications.[13]

Given the shortages of therapeutic resources during the pandemic, ambulatory strategies were implemented in Thailand to obviate the need for hospital admission of asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients. In addition to early antiviral therapy, it was essential to administer systemic corticosteroids as adjuncts to reduce mortality in patients with moderate symptoms who develop desaturation (an oxygen saturation < 95%).[14] Dexamethasone was the corticosteroid of choice as it could be given orally or intravenously.[15] Most evidence supports the use of dexamethasone for in-hospital care. However, with medical personnel and other resource shortages, it is also feasible to prescribe dexamethasone for patients with moderate symptoms on an outpatient basis and under the close supervision of healthcare personnel.

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of early favipiravir treatment in preventing clinical deterioration in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic COVID-19 patients in home isolation. Its secondary purpose was to describe our experiences with the ambulatory management of nonsevere COVID-19 patients.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This retrospective study enrolled COVID-19 patients registered to receive care under the Siriraj home isolation system (Si-home) between July 2021 and November 2021. The study protocol was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Siriraj Institutional Review Board (Si732/2021), Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. The eligibility criteria were an age of 18 years or older, not pregnant, and the absence of advanced liver disease (e.g., cirrhosis or severe hepatic impairment). All study participants were asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic, and none required oxygen supplementation at their presentation. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection was confirmed with the real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) technique. After confirmation of COVID-19, the participants were assigned care through Si-home and were given favipiravir treatment.

2.2. Data collection

Demographic data, baseline characteristics, and clinical progression were collected from the hospital’s electronic medical records and the Si-home self-report electronic database.

2.3. The Si-home

Si-home is an out-of-hospital system for the care of COVID-19 patients during COVID surges. During the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand, all patients at Siriraj Hospital with respiratory tract symptoms or suspected COVID-19 were triaged at the acute respiratory infection (ARI) clinic. Patients with dyspnea, shortness of breath, chest pain or tightness, hemoptysis, desaturation, tachypnea, or nausea and vomiting were classified as severe. They were sent to the emergency room for further evaluation. Patients classified as nonsevere underwent the COVID-19 diagnostic process at the ARI clinic: history taking, vital sign taking, and a nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 RT-PCR testing. Subsequently, the patients were advised to undertake self-quarantine at home and wait for the laboratory results.

Once the test results were available, an infectious disease specialist triaged patients with a confirmed COVID-19 infection to receive care through Si-home. The patient criteria for Si-home were being asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic upon presentation at the ARI clinic, able to self-quarantine, and able to care for themselves at their home.

After patients’ assignment to Si-home, the triage doctor prescribed essential medications for their treatment. They consisted of symptomatic treatment medications (cetirizine, cough suppressant, and acetaminophen), a 5-day course of favipiravir, and dexamethasone. The favipiravir dosage was based on each patient’s body weight. Although the dexamethasone tablets were provided as part of the Si-home medications, they were labeled “not to be taken unless advised by your doctor by phone call.” Equipment to monitor patients’ vital signs (a digital thermometer and a pulse oximeter) was also provided. The medications and equipment were dispatched to patients via commercial delivery services on the day of their prescription or the next day.

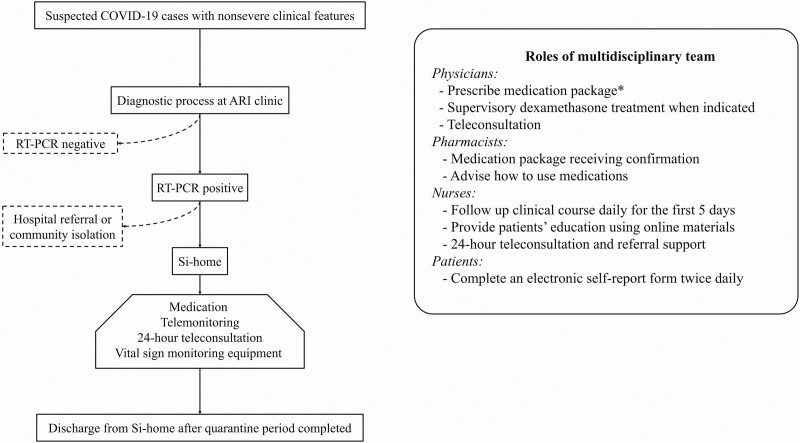

Afterward, the multidisciplinary team has roles and responsibilities in taking care of patients during the Si-home quarantine period, 14 days after the onset of symptoms (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the COVID-19 patients that registered the Siriraj home isolation system and roles of multidisciplinary team. *medication package includes symptomatic medications, dexamethasone, and 5-day courses of favipiravir based on patient BW. BW < 90 kg; Day 1: 1800 mg bid, Day 2–4: 800 mg bid. BW ≥ 90 kg; Day 1: 2400 mg bid, Day 2-4: 1000 mg bid. ARI = acute respiratory infection, bid = twice daily, BW = body weight, COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, kg = kilograms, mg = milligrams, RT-PCR = reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, Si-home = Siriraj home isolation system.

During the quarantine period, if patients reported worrisome symptoms or abnormal vital signs (including oxygen saturation), nurses immediately contacted them by telephone or video call to assess the symptom severity. These were reported to an attending doctor. If the symptoms met the criteria for dexamethasone treatment, the doctor prescribed the drug. The nurses phoned the patients back to advise them to start the medication the medication course immediately (6 mg once daily for 5 days). However, if the symptoms worsened or the patients needed oxygen supplementation therapy, the patients were transferred to Siriraj Hospital for inpatient management.

Out-of-hospital dexamethasone treatment was initiated if any 1 of the following criteria were met: oxygen saturation < 96%; dyspnea without desaturation, but the oxygen saturation dropped by > 3 percentage points during exercise or a sit-to-stand test; or fever ≥ 38°C for more than 48 hours. Patients who met these criteria or had other health conditions that justified hospitalization in the attending physician’s judgment were classified as the “clinical deterioration” group.

For patients in the “clinically stable” group, clinical improvement after receiving favipiravir was measured as follows:[9]

Time to recover from fever. This was the duration from the first favipiravir dose to when a patient’s body temperature fell to < 37°C, with maintenance for at least 72 hours. This measure was only applied to patients with a temperature > 37°C at the ARI clinic.

Time to cough relief. This was the duration from the first favipiravir dose to when a patient reported mild or no cough, with maintenance for at least 72 hours. This measure was only applied to patients who reported cough at the ARI clinic.

Patients were placed into 2 groups based on the timing of their first dose of favipiravir. Those who took the first dose within 5 days after symptom onset were assigned to the “early favipiravir treatment” group. The patients who took their first dose after the fifth day were allocated to the “late favipiravir treatment” group.

2.4. COVID-19 vaccination status

COVID-19 vaccination status was classified into the following 3 categories:

Fully vaccinated. This applied to patients given a second dose of any COVID-19 vaccine more than 14 days before onset.

Partially vaccinated. This referred to patients given a second dose of any COVID-19 vaccine within 14 days before symptom onset or only 1 dose more than 14 days before onset.

Unvaccinated. This category was employed for patients given a single dose of any COVID-19 vaccine within 14 days before symptom onset or those without COVID-19 vaccination.

2.5. Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

No prior study has investigated the effects of favipiravir treatment on the clinical deterioration of COVID-19 in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients in an ambulatory care setting. Therefore, we collected and analyzed the data of all eligible patients enrolled in Si-home.

Descriptive statistics were used to report the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables with a normal distribution are given as the mean ± standard deviation, and continuous variables with a nonnormal distribution are shown as the median and interquartile range (IQR). As appropriate, comparisons of categorical data were performed using the chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Comparisons of normally and nonnormally distributed continuous data were performed using Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were employed to investigate the associations between clinical factors and disease progression. The magnitudes of the associations are presented as odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted odds ratios (aORs). A probability (P) value < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics for Windows, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). The forest plot was illustrated using Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic data

In all, 1940 adult patients with nonsevere COVID-19 who met the enrollment criteria were registered on Si-home between July 2021 and November 2021. This was when the Delta variant of COVID-19 peaked in Thailand. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the early and late favipiravir treatment groups are detailed in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 42.1 ± 14.9 years, with over half being female (54.3%). There were 133 (7.1%) patients with a body weight ≥ 90 kg. One-sixth of the patients (n = 276) were older than 60, and 637 (32.8%) had at least 1 comorbidity. The 3 most common comorbidities were hypertension (15.3%), diabetes mellitus (7.3%), and lipid disorders (5.8%). Most patients (1795; 92.5%) had symptoms of COVID-19, while the remaining 145 (7.5%) patients were asymptomatic at presentation. The median time from the onset of COVID-19 symptoms to the first dose of favipiravir was 5 days (IQR 4–7). The mean RT-PCR cycle threshold was 22.1 ± 5.6.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (N = 1940).

| Early favipiravir treatment (n = 1076) | Late favipiravir treatment (n = 864) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 485 (45.1%) | 401 (46.4%) | .557 |

| Age (years) | 43.0 ± 15.1 | 40.8 ± 14.7 | .001 |

| Age > 60 years | 169 (15.7%) | 107 (12.4%) | .037 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 ± 5.3 | 24.8 ± 5.1 | .02 |

| BW ≥ 90 kg | 87 (8.4%) | 46 (5.5%) | .016 |

| Vaccination status | <.001 | ||

| •Unvaccinated | 485 (47.5%) | 574 (69.8%) | |

| •Partially vaccinated | 333 (32.6%) | 161 (19.6%) | |

| •Vaccinated | 204 (20.0%) | 87 (10.6%) | |

| Symptomatic at presentation | 931 (86.5%) | 864 (100.0%) | <.001 |

| ≥ 1 comorbidities | 358 (33.3%) | 279 (32.3%) | .648 |

| •HT | 174 (8.1%) | 122 (6.3%) | .212 |

| •DM | 87 (16.2%) | 54 (14.1%) | .122 |

| •Lipid disorders | 67 (6.2%) | 45 (5.2%) | .339 |

| •Stroke | 7 (0.7%) | 5 (0.6%) | .841 |

| •CKD | 8 (0.7%) | 7 (0.8%) | .868 |

| RT-PCR cycle threshold | 21.5 ± 5.9 | 22.8 ± 5.2 | <.001 |

| Time to start favipiravir after symptom onset (days) | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 7.9 ± 1.9 | <.001 |

BMI = body mass index, BW = body weight, CKD = chronic kidney disease, DM = diabetes mellitus, HT = hypertension, kg = kilograms, m2 = square meter, RT-PCR = reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

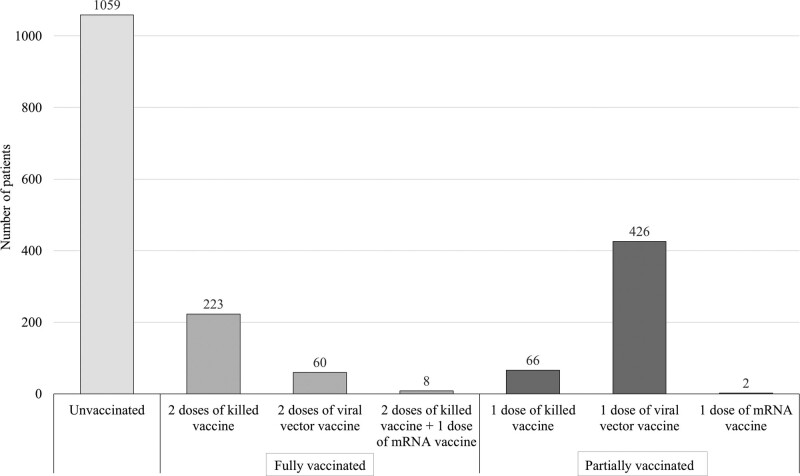

3.2. COVID-19 vaccination status

Vaccination statuses were collected for 1844 (94.2%) patients. Approximately 60% of the patients in this subgroup were unvaccinated (n = 1059; 57.4%); only 291 (15.8%) were fully vaccinated, and the remaining 494 (26.8%) patients were partially vaccinated. Among the 291 fully vaccinated patients, 76.6% were given 2 doses of killed vaccine, 20.6% received 2 doses of viral vector vaccine, and 2.8% had 2 doses of killed vaccine followed by 1 dose of mRNA vaccine. Of the 494 partially vaccinated patients, 13.4% were administered 1 dose of killed vaccine, 86.2% received 1 dose of viral vector vaccine, and 2 were given 1 dose of mRNA vaccine (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

COVID-19 vaccination status of COVID-19 patients in Si-home (N = 1844).

3.3. Early versus late favipiravir treatment and clinical deterioration

The early favipiravir treatment group had significantly higher proportions of patients with prognostic factors for severe disease than the late favipiravir treatment group. Regarding an age ≥ 60 years, the early treatment group had 169 (15.7%) patients compared with 107 (12.4%) in the late treatment group (P = .037). As for a body weight ≥ 90 kg, the early treatment group had 87 (8.4%) patients, whereas the late treatment group had 46 (5.5%; P = .016). However, the proportion of unvaccinated patients in the early treatment group was lower than that in the late treatment group (485 [47.5%] vs 574 [69.8%] patients, respectively; P < .001). Additionally, all patients in the late favipiravir treatment group had mild symptoms. While only 86.5% of the early favipiravir treatment group had symptoms at enrollment, the rest was asymptomatic (P < .001).

Of the 1940 patients, a worsening of clinical symptoms (e.g., desaturation) was found in only 115 (5.9%) patients, of whom 38 (2.0% of the study cohort) required hospital admission. Early favipiravir treatment was significantly associated with a lower rate of symptom deterioration than late treatment (50 [4.6%] vs 65 [7.5%] patients, respectively; P = .008; OR 1.669; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.141–2.441).

3.4. Clinical deterioration related factors

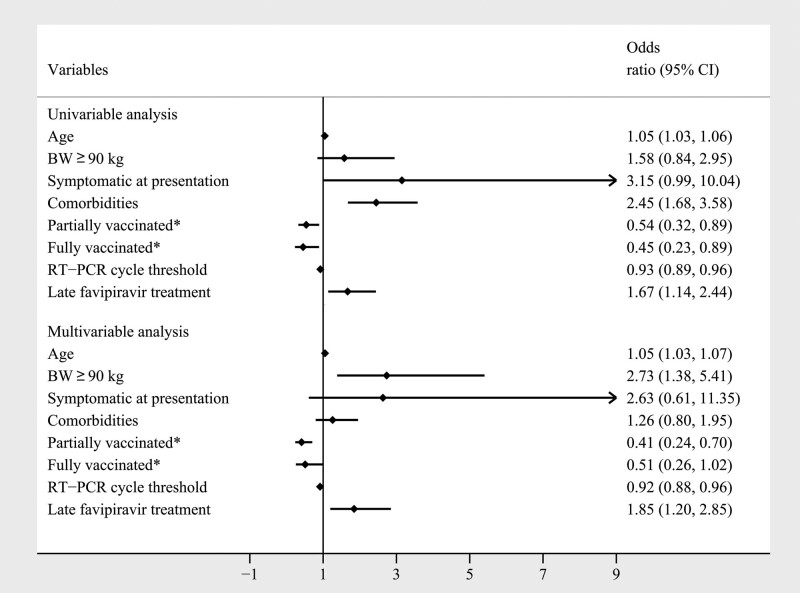

Logistic regression analysis identified the predictors of clinical deterioration in asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic COVID-19 patients. They were age, symptomatic at presentation, associated comorbidities, vaccination status, RT-PCR cycle threshold, and late administration of favipiravir. The subsequent multivariable logistic regression analysis determined that older age, body weight ≥ 90 kg, vaccination status, RT-PCR cycle threshold, and late favipiravir treatment were statistically associated with clinical deterioration during treatment (Fig. 3). A body weight ≥ 90 kg presented a 2.735-fold greater risk of worsening clinical symptoms (OR 2.735; 95% CI, 1.384–5.405; P = .004). Advancement of age resulted in a 1.052-fold higher risk of desaturation (OR 1.052; 95% CI, 1.035–1.069; P < .001).

Figure 3.

Logistic regression of the factors associated with clinical deterioration during the treatment courses in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic COVID-19 patients (N = 1940). *Compared with unvaccinated population. BW = body weight, kg = kilograms, RT-PCR = reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

Moreover, the infectivity rate of COVID-19 was associated with clinical outcomes. Patients with a higher RT-PCR cycle threshold had a lower chance of clinical deterioration (OR 0.917; 95% CI, 0.876–0.961; P < .001). Early favipiravir treatment and vaccination prevented clinical deterioration in patients with asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic COVID-19. Administration of the first favipiravir dose more than 5 days after symptom onset was associated with a 1.846-fold higher chance of clinical deterioration than administration within 5 days (OR 1.846; 95% CI, 1.196–2.849; P = .006). Furthermore, the COVID-19 vaccines showed efficacy against clinical deterioration in patients with different levels of vaccination protection. The chance of clinical deterioration was lowered for partially vaccinated patients, most of whom (86.2%) received 1 dose of a viral vector vaccine (OR 0.412; 95% CI, 0.240–0.704; P = .001).

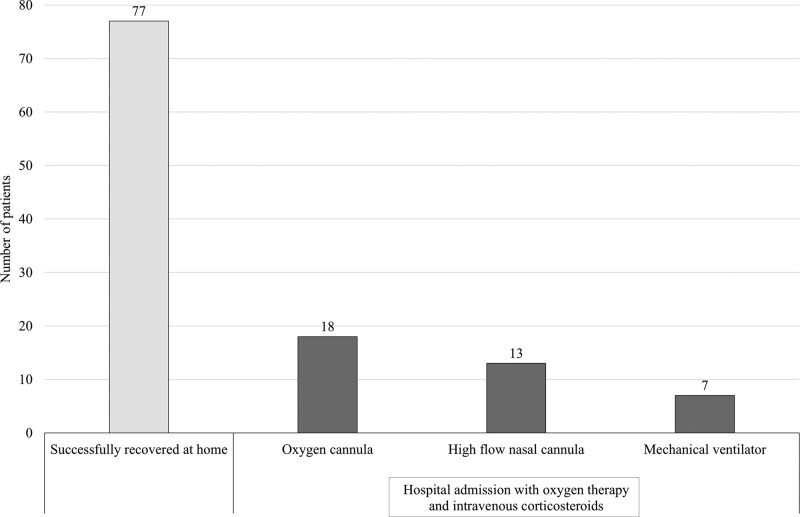

3.5. Outcomes of ambulatory dexamethasone treatment

In patients with clinical progression to dyspnea with desaturation, medical intervention with dexamethasone was performed on an out-of-hospital basis. The clinical outcomes of all patients in Si-home are presented in Table 2. Of the 115 patients with clinical deterioration, 77 (67.0%) showed clinical improvement after dexamethasone treatment and made a full recovery at home. Thirty-eight (33.0%) of these were admitted to the hospital and required oxygen therapy as well as intravenous corticosteroids. Eighteen (47.4%) of the hospitalized patients were successfully managed with oxygen cannulas, 13 (34.2%) were treated with high-flow nasal cannulas, and 7 needed mechanical ventilator support. Only 8 of hospitalized patients (0.4% of the study cohort) had clinical progression to in-hospital death, with all 7 on mechanical ventilator support dying. Figure 4 illustrates the clinical outcomes of patients who had clinical deterioration.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients in Si-home (N = 1940).

| Early favipiravir treatment (n = 1076) | Late favipiravir treatment (n = 864) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mildly symptomatic and cured at home | 1026 (95.4%) | 799 (92.5%) |

| Clinical deterioration | 50 (4.6%) | 65 (7.5%) |

| •Cured at home | 25 (2.3%) | 52 (6.0%) |

| •Hospital admission | 25 (2.3%) | 13 (1.5%) |

| In-hospital death | 7 (0.7%) | 1 (0.1%) |

Figure 4.

Clinical outcomes of patients with clinical deterioration (N = 115).

3.6. Effects of favipiravir treatment in patients without clinical deterioration

Further analysis was conducted to determine whether early favipiravir treatment enhanced the resolution of symptoms in the 1825 patients in the clinically stable group (those who did not experience clinical deterioration). In all, 619 of these patients reported having fever at the onset of their symptoms and provided daily online details of their temperature progression throughout the 14-day quarantine period. Forty-two (6.8%) of this subgroup of patients reported having persistent fever until their discharge from Si-home. The fever resolution rates of the early and late favipiravir treatment groups demonstrated no significant difference (P = .202; 95% CI, 0.819–2.930).

A total of 1058 patients reported having cough at symptom onset and provided daily online details of their cough progression throughout the 14-day quarantine period. Persistent cough was reported by 329 (31.1%) patients in this subgroup until their discharge from Si-home. There was no significant difference between the cough resolution rates of the early and late favipiravir treatment groups (P = .641; 95% CI, 0.718–1.212). The mean times to cough relief were 4 (IQR 2–8) and 2 (IQR 0–4) days, respectively, after receiving the first favipiravir dose (P < .001).

3.7. Factors associated with early favipiravir treatment failure

Approximately 5% of the early favipiravir treatment group’s asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic COVID-19 patients progressed to moderate symptoms. The results of our univariable and multivariable analyses with a logistic regression model are presented in Table 3. One of the significant predictors identified for worsening symptoms was patient age (OR 1.070; 95% CI, 1.043–1.097; P < .001). Another factor was COVID-19 vaccination status. The COVID-19 vaccines demonstrated their efficacy in preventing asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients from progressing to moderate symptoms. In patients who were partially vaccinated (mostly with 1 dose of a viral vector vaccine), the chance of clinical deterioration was lowered by 0.309-fold (OR 0.309; 95% CI, 0.145–0.655; P = .002).

Table 3.

Logistic regression of the factors associated with clinical deterioration during the treatment course in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic COVID-19 patients who received early favipiravir treatment (n = 1094).

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Age | 1.064 (1.042–1.085) | <.001 | 1.070 (1.043–1.097) | <.001 |

| BW ≥ 90 kg | 1.229 (0.475–3.182) | .670 | 2.063 (0.725–1.026) | .175 |

| Symptomatic at presentation | 2.517 (0.773–8.194) | .133 | 3.333 (0.752–14.768) | .113 |

| Comorbidities | 3.817 (2.111–6.902) | <.001 | 1.717 (0.864–3.412) | .123 |

| Partially vaccinated* | 0.518 (0.256–1.049) | .068 | 0.309 (0.145–0.655) | .002 |

| Fully vaccinated* | 0.381 (0.146–0.997) | .049 | 0.450 (0.166–1.219) | .116 |

| RT-PCR cycle threshold | 0.939 (0.887–0.994) | .029 | 0.957 (0.893–1.026) | .214 |

Compared with unvaccinated population. BW = body weight, kg = kilograms, RT-PCR = reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

4. Discussion

During the peak of the Delta variant wave of COVID-19, many countries faced severe shortages of hospital beds, medical facilities, and healthcare personnel to care for newly infected patients via conventional hospital admission strategies. The shortfalls were particularly pronounced in resource-limited areas and developing countries. Consequently, ambulatory care systems, such as field hospitals, out-of-hospital isolation, and online medical services, were established for patients with asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic manifestations. Siriraj Hospital, a university hospital in Bangkok, Thailand, implemented the Siriraj home isolation system, or Si-home, to support COVID-19 patients. Medications such as favipiravir and digital oxygen saturation measurement devices were delivered to patients in their homes, and telephone monitoring under physician supervision was provided until the disease had improved. Thus, Si-home achieved the goal of early favipiravir treatment for more than 1000 patients during the crisis.

Moreover, Si-home’s close telemedicine monitoring enabled early detection of the progression of an illness to a moderate or severe level. Consequently, Si-home physicians could rapidly initiate appropriate treatment. Typically, this took the form of a course of corticosteroid therapy using the dexamethasone supplied to each patient at the beginning of home isolation. However, on occasion, the physicians arranged for the prompt return of a patient to the hospital.

Early outpatient treatment of COVID-19, including antiviral therapy, aims to prevent hospitalization or death. Based on pathophysiology, the rationale for early favipiravir treatment is a reduction in the rate, quantity, and duration of viral replication, coupled with a lower degree of direct viral injury to the respiratory epithelium, vasculature, and organs. The optimum period for treating a patient with favipiravir is within 5 days after the appearance of the first symptom; this duration corresponds with the “viral phase” of COVID-19. Additionally, antiviral drug administration suppresses viral stimulation and, if viral replication is attenuated, the activation of inflammatory cells, cytokines, and coagulation.[16,17]

A phase II/III, multicenter, randomized clinical trial was conducted of favifavir, which is favipiravir that has been resynthesized in Russia.[18] The trial’s interim results indicated a significantly higher viral clearance rate on the fifth day among hospitalized COVID-19 patients administered avifavir than among nonrecipients, and the drug was well tolerated. However, Doi et al[19] found contrasting results in their prospective, randomized, open-label trial of early versus late favipiravir therapy in hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Japan. That research team concluded that favipiravir did not improve viral clearance by RT-PCR measurement by day 6 but was associated with a reduction in the time to defervescence. Another interesting point is that the research by Doi and colleagues monitored participants for 28 days; neither disease progression nor death occurred among the 89 enrolled patients during this period.

A single-arm study was conducted by Procter and associates[20] on the clinical outcomes of 922 outpatients who were not hospitalized but treated at home. They underwent early ambulatory multidrug therapy for high-risk COVID-19. The investigation used zinc, hydroxychloroquine, and ivermectin as antiviral agents—but not favipiravir—together with steroids (inhaled budesonide/intramuscular dexamethasone). The study concluded that early ambulatory multidrug therapy is safe, feasible, and associated with low rates of hospitalization and death.

Our work was a large comparative study of 1940 patients in the early (1076 patients) and late (864 patients) favipiravir treatment groups in Si-home. We focused on the clinical progression from asymptomatic or mild symptoms to moderate or severe illness. The categorization of participants receiving favipiravir within 5 days after the onset of their first symptom into the early group was based on pathophysiology, acceptable studies, and guidelines.

This is the first study to focus on interesting dynamic outcomes such as clinical progression. Si-home patients were deemed to be in the clinical deterioration group if, during their 14-day quarantine period, they were either prescribed dexamethasone by a Si-home doctor or were admitted to the hospital. The prescribing of dexamethasone was based on patients’ self-reported respiration parameters, a persistent fever exceeding 48 hours, or any other condition that the Si-home doctor deemed to warrant corticosteroid administration. In our view, this is the most practical and appropriate method for identifying clinical deterioration in real-world practice. As we recognized that many factors influence clinical severity (e.g., age, obesity, comorbidities, and vaccination status),[21] we performed a multivariable analysis to adjust for confounding factors. Our study also performed a subgroup analysis of the determinants of clinical deterioration in the early favipiravir treatment group.

On the other hand, our research has some limitations. It employed a retrospective study design, and there were some inequalities in the baseline characteristics of the early and late favipiravir treatment groups. Moreover, given the pressure that Si-home was under during the Delta variant surge, we could not ensure that participants had been blindly and randomly assigned to the early and late favipiravir treatment groups. Fortunately, the Si-home physicians blindly and freely assessed clinical progression and prescribed dexamethasone.

The majority of our study participants were adults and middle-aged. The average age was approximately 42 years, and only 14% of the patients were over 60. This predominantly middle-aged population corresponded with the age group most likely to have mild disease severity at diagnosis and, therefore, to be suitable for out-of-hospital care. We expected that the rate of clinical deterioration during home isolation would be around 5% to 10%. Rates higher than 10% would indicate that patients’ anticipated severities of illness had been underestimated during the triage undertaken before their placement in Si-home. Conversely, clinical deterioration rates lower than 5% would signal an overestimation of their anticipated severities of illness. Ultimately, our study cohort had 115 (5.9%) patients with clinical deterioration.

Regarding the baseline characteristics, the early favipiravir treatment group had several significantly worse unfavorable prognostic factors than the late group. They were mean age (43.0 ± 15.1 vs 40.8 ± 14.7; P = .001), age ≥ 60 years (15.7% vs 12.4%; P = .037), body weight ≥ 90 kg (8.4% vs 5.5%; P = .016), and RT-PCR cycle threshold (21.5 vs 22.8; P < .001). However, the late favipiravir treatment group was disadvantaged via its higher proportion of unvaccinated patients (69.8% vs 47.5%; P < .001). After entering the unequal confounders into the multivariable regression analysis to justify the outcomes, we still found that late favipiravir treatment was an associated factor of COVID-19 clinical deterioration, with an OR of 1.846 (P = .006).

A randomized, open-label, clinical trial of early treatment with favipiravir in Malaysia by Chuah et al[22] showed that favipiravir had a nonsignificant effect on preventing disease progression among high-risk patients. Our study had some critical differences:

It enrolled lower-risk patients (younger and with fewer poor-prognostic factors).

It was conducted in an ambulatory setting rather than a hospitalized setting.

It focused on various worsening clinical characteristics, with or without hypoxia.

We hypothesize that early favipiravir treatment in patients with low risks and mild symptoms alleviates clinical deterioration, whereas there is no statistically significant difference among patients with high risks or severe symptoms.

Our study also explored the variables influencing a worsening of the clinical course. The multivariable analysis revealed that advanced age, a body weight ≥ 90 kg, and a higher RT-PCR cycle threshold were unfavorable parameters (Fig. 3). Body weight ≥ 90 kg showed the highest magnitude in this study, which is consistent with previous studies that highlighted the impact of obesity.[23,24] The multivariable analysis also clearly identified vaccination status as a protective factor, with partial vaccination demonstrating a greater likelihood of a favorable clinical outcome than full vaccination (OR 0.42 vs 0.51). An explanation for this anomaly is that immunity might steadily wane in fully vaccinated patients as time progresses from their last COVID-19 booster shot. In contrast, partially vaccinated patients might be relatively recent vaccine recipients. However, our study did not explore the level of immunity.

Not surprisingly, the logistic regression analysis of the RT-PCR cycle threshold revealed a strong significant correlation with clinical deterioration (P < .001). This finding is compatible with a robust systematic review conducted by Rao and colleagues[25] that indicated that lower RT-PCR cycle thresholds (less time for the RT-PCR run in viral amplification) produced poorer outcomes than higher thresholds. A lower cycle threshold reflects higher infectivity and greater amounts of the virus. This typically indicates a longer time for viral clearance, thereby possibly stimulating a hyperimmune response and, in turn, causing a complicated disease course.

The clinical outcomes clearly showed a lower rate of overall clinical deterioration in the early treatment group than in the late group (50/1076 patients [4.6%] vs 65/864 patients [7.5%]). A subset examination revealed that half of the clinical deterioration patients in the early treatment group needed hospitalization, whereas the corresponding proportion for the late treatment group was one-fifth. Nevertheless, this finding is minor as it does not relate to our primary objective. Moreover, the population sizes of the individual clinical deterioration subsets are too small to draw definitive conclusions. Likewise, the 7 in-hospital deaths in the early treatment group and the 1 death in the late treatment group are incomparable because of the very low incidences. Our tentative explanation is that early favipiravir treatment improves outcomes in mild cases but not in moderate or severe cases.

5. Conclusions

Our study shared our experiences with a home isolation system during the Delta variant surge of COVID-19. This ambulatory strategy rescues patients who cannot otherwise access healthcare systems that have become overwhelmed by high demand and insufficient resources. The administration of early antivirus and supervisory dexamethasone therapy to suppress new severe cases may alleviate the public health burdens. Our findings emphasize the need for early delivery of essential treatment to nonsevere COVID-19 patients, especially those in high-risk groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank all healthcare personnel involved in patient care. The authors also thank Miss Pinyapat Ariyakunaphan and Miss Euarat Meepramoon, research assistants, for collecting the data, and Mr. David Park for the language editing.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Tullaya Sitasuwan, Pochamana Phisalprapa, Weerachai Srivanichakorn, Chaiwat Washirasaksiri, Chonticha Auesomwang, Rungsima Tinmanee, Naruemit Sayabovorn, Methee Chayakulkeeree, Pakpoom Phoompoung, Korapat Mayurasakorn, Nitat Sookrung, Anchalee Tungtrongchitr, Rungsima Wanitphakdeedecha, Saipin Muangman, Sansnee Senawong, Watip Tangjittipokin, Gornmigar Sanpawitayakul, Diana Woradetsittichai, Pongpol Nimitpunya, Chayanis Kositamongkol, Cherdchai Nopmaneejumruslers, Visit Vamvanij, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Data curation: Tullaya Sitasuwan, Naruemit Sayabovorn, Pongpol Nimitpunya, Chayanis Kositamongkol, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Formal analysis: Tullaya Sitasuwan, Pochamana Phisalprapa, Weerachai Srivanichakorn, Naruemit Sayabovorn, Chayanis Kositamongkol, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Funding acquisition: Pochamana Phisalprapa.

Investigation: Tullaya Sitasuwan, Pochamana Phisalprapa, Weerachai Srivanichakorn, Chaiwat Washirasaksiri, Chonticha Auesomwang, Rungsima Tinmanee, Naruemit Sayabovorn, Methee Chayakulkeeree, Pakpoom Phoompoung, Korapat Mayurasakorn, Nitat Sookrung, Anchalee Tungtrongchitr, Rungsima Wanitphakdeedecha, Saipin Muangman, Sansnee Senawong, Watip Tangjittipokin, Gornmigar Sanpawitayakul, Diana Woradetsittichai, Pongpol Nimitpunya, Chayanis Kositamongkol, Cherdchai Nopmaneejumruslers, Visit Vamvanij, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Methodology: Tullaya Sitasuwan, Pochamana Phisalprapa, Weerachai Srivanichakorn, Chaiwat Washirasaksiri, Chonticha Auesomwang, Rungsima Tinmanee, Naruemit Sayabovorn, Chayanis Kositamongkol, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Project administration: Tullaya Sitasuwan, Pochamana Phisalprapa, Weerachai Srivanichakorn, Chaiwat Washirasaksiri, Chonticha Auesomwang, Rungsima Tinmanee, Naruemit Sayabovorn, Methee Chayakulkeeree, Pakpoom Phoompoung, Korapat Mayurasakorn, Nitat Sookrung, Anchalee Tungtrongchitr, Rungsima Wanitphakdeedecha, Saipin Muangman, Sansnee Senawong, Watip Tangjittipokin, Gornmigar Sanpawitayakul, Diana Woradetsittichai, Pongpol Nimitpunya, Chayanis Kositamongkol, Cherdchai Nopmaneejumruslers, Visit Vamvanij, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Resources: Tullaya Sitasuwan, Pochamana Phisalprapa, Weerachai Srivanichakorn, Chaiwat Washirasaksiri, Chonticha Auesomwang, Rungsima Tinmanee, Naruemit Sayabovorn, Chayanis Kositamongkol, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Supervision: Pochamana Phisalprapa, Korapat Mayurasakorn, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Validation: Tullaya Sitasuwan, Pochamana Phisalprapa, Weerachai Srivanichakorn, Chaiwat Washirasaksiri, Naruemit Sayabovorn, Chayanis Kositamongkol, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Visualization: Tullaya Sitasuwan, Pochamana Phisalprapa, Naruemit Sayabovorn, Chayanis Kositamongkol, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Writing – original draft: Tullaya Sitasuwan, Pochamana Phisalprapa, Chayanis Kositamongkol, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Writing – review & editing: Tullaya Sitasuwan, Pochamana Phisalprapa, Weerachai Srivanichakorn, Chaiwat Washirasaksiri, Chonticha Auesomwang, Rungsima Tinmanee, Naruemit Sayabovorn, Methee Chayakulkeeree, Pakpoom Phoompoung, Korapat Mayurasakorn, Nitat Sookrung, Anchalee Tungtrongchitr, Rungsima Wanitphakdeedecha, Saipin Muangman, Sansnee Senawong, Watip Tangjittipokin, Gornmigar Sanpawitayakul, Diana Woradetsittichai, Pongpol Nimitpunya, Chayanis Kositamongkol, Cherdchai Nopmaneejumruslers, Visit Vamvanij, Thanet Chaisathaphol.

Abbreviations:

- ARI =

- acute respiratory infection

- CI =

- confidence interval

- COVID-19 =

- coronavirus disease 2019

- IQR =

- interquartile range

- OR =

- odds ratio

- RT-PCR =

- reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- Si-home =

- Siriraj home isolation system

The study was conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Siriraj Institutional Review Board (Si732/2021). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

The authors have no consent to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This research was funded by the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand (R016534002).

How to cite this article: Sitasuwan T, Phisalprapa P, Srivanichakorn W, Washirasaksiri C, Auesomwang C, Tinmanee R, Sayabovorn N, Chayakulkeeree M, Phoompoung P, Mayurasakorn K, Sookrung N, Tungtrongchitr A, Wanitphakdeedecha R, Muangman S, Senawong S, Tangjittipokin W, Sanpawitayakul G, Woradetsittichai D, Nimitpunya P, Kositamongkol C, Nopmaneejumruslers C, Vamvanij V, Chaisathaphol T. Early antiviral and supervisory dexamethasone treatment improve clinical outcomes of nonsevere COVID-19 patients. Medicine 2022;101:45(e31681).

Contributor Information

Tullaya Sitasuwan, Email: tullaya.sita@gmail.com.

Pochamana Phisalprapa, Email: coco_a105@hotmail.com.

Weerachai Srivanichakorn, Email: pop.weerachai@gmail.com.

Chaiwat Washirasaksiri, Email: golf_si36@hotmail.com.

Chonticha Auesomwang, Email: chonticha_nui@yahoo.com.

Rungsima Tinmanee, Email: sirwn@mahidol.ac.th.

Naruemit Sayabovorn, Email: naruemit114@gmail.com.

Methee Chayakulkeeree, Email: methee.cha@mahidol.ac.th.

Pakpoom Phoompoung, Email: pakpoom.pho@mahidol.ac.th.

Korapat Mayurasakorn, Email: korapat.may@mahidol.edu.

Nitat Sookrung, Email: nitat.soo@mahidol.edu.

Anchalee Tungtrongchitr, Email: anchalee.tun@mahidol.ac.th.

Rungsima Wanitphakdeedecha, Email: sirwn@mahidol.ac.th.

Saipin Muangman, Email: saipinnoolek@gmail.com.

Sansnee Senawong, Email: sansnee.sen@mahidol.ac.th.

Watip Tangjittipokin, Email: watip.tan@mahidol.edu.

Gornmigar Sanpawitayakul, Email: gornmigar.win@mahidol.ac.th.

Diana Woradetsittichai, Email: diana.wor@mahidol.ac.th.

Pongpol Nimitpunya, Email: pongpol.nim@gmail.com.

Chayanis Kositamongkol, Email: chayanis.kos@mahidol.edu.

Cherdchai Nopmaneejumruslers, Email: cnopman@gmail.com.

Visit Vamvanij, Email: drvisitvam@gmail.com.

References

- [1].Baughman AW, Hirschberg RE, Lucas LJ, et al. Pandemic care through collaboration: lessons from a COVID-19 field hospital. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1563–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].et al. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard [Internet]. Available at: https://covid19.who.int/ [access date August 28, 2022].

- [3].Ayaz CM, Dizman GT, Metan G, et al. Out-patient management of patients with COVID-19 on home isolation. Infez Med. 2020;28:351–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].et al. Guidelines for healthcare professionals in patient advice and home isolation for COVID-19 patients. Thailand: The Ministry of Public Health. 2021. [access date August 28, 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Long B, Chavez S, Carius BM, et al. Clinical update on COVID-19 for the emergency and critical care clinician: Medical management. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;56:158–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].et al. Guidelines for healthcare professionals in diagnosis treatment and in hospital infectious control for COVID-19. Thailand: The Ministry of Public Health. 2021. [access date August 28, 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Delang L, Abdelnabi R, Neyts J. Favipiravir as a potential countermeasure against neglected and emerging RNA viruses. Antiviral Res. 2018;153:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shinkai M, Tsushima K, Tanaka S, et al. Efficacy and safety of favipiravir in moderate COVID-19 pneumonia patients without oxygen therapy: a randomized, phase III clinical trial. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10:2489–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Udwadia ZF, Singh P, Barkate H, et al. Efficacy and safety of favipiravir, an oral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, in mild-to-moderate COVID-19: A randomized, comparative, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 clinical trial. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fujii S, Ibe Y, Ishigo T, et al. Early favipiravir treatment was associated with early defervescence in non-severe COVID-19 patients. J Infect Chemother. 2021;27:1051–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cai Q, Yang M, Liu D, et al. Experimental treatment with Favipiravir for COVID-19: an open-label control study. Engineering. 2020;6:1192–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].CDC Covid- Response Team. Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 - United States, February 12-March 28, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:382–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shiraki K, Sato N, Sakai K, et al. Antiviral therapy for COVID-19: derivation of optimal strategy based on past antiviral and favipiravir experiences. Pharmacol Therap. 2022;235:108121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].The WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies Working Group. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1330–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Recovery Collaborative Group . Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].McCullough PA, Kelly RJ, Ruocco G, et al. Pathophysiological basis and rationale for early outpatient treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection. Am J Med. 2021;134:16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Izzedine H, Jhaveri KD, Perazella MA. COVID-19 therapeutic options for patients with kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2020;97:1297–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ivashchenko AA, Dmitriev KA, Vostokova NV, et al. AVIFAVIR for treatment of patients with moderate Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): interim results of a phase II/III multicenter randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:531–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Doi Y, Hibino M, Hase R, et al. A prospective, randomized, open-label trial of early versus late favipiravir therapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e01897-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Procter BC, Ross C, Pickard V, et al. Clinical outcomes after early ambulatory multidrug therapy for high-risk SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020;21:611–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gallo Marin B, Aghagoli G, Lavine K, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 severity: a literature review. Rev Med Virol. 2021;31:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chuah CH, Chow TS, Hor CP, et al. Efficacy of early treatment with favipiravir on disease progression among high risk COVID-19 patients: a randomized, open-label clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75:e432–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yu W, Rohli KE, Yang S, et al. Impact of obesity on COVID-19 patients. J Diabetes Complications. 2021;35:107817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kwok S, Adam S, Ho JH, et al. Obesity: a critical risk factor in the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Obes. 2020;10:e12403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rao SN, Manissero D, Steele VR, et al. A systematic review of the clinical utility of cycle threshold values in the context of COVID-19. Infect Dis Ther. 2020;9:573–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]