Abstract

Little is known about the impacts of covid-19 pandemic on mental health problems among youth population whereas this information is extremely necessary to develop appropriate actions to support these young people overcoming psychological crisis and increasing satisfaction with life during the disease outbreak. This study not only explores the influences of fear and anxiety of covid-19 on life satisfaction, but it also examines the mediating roles of psychological distress and sleep disturbance in this linkage. 1521 students from universities in Vietnam was assessed utilizing the online-based cross-sectional survey. The study revealed that fear and anxiety of covid-19 was strongly related to psychological distress and sleep disturbance and life satisfaction among Vietnamese university students. Also, life satisfaction was found to have a strong and negative association with psychological distress, but without sleep disturbance. Moreover, the findings of the study revealed that fear and anxiety of covid-19 reduced life satisfaction and increased sleep disturbance via psychological distress. This study was expected to contribute to the extant literature by enriching our understanding the serious impacts of covid-19 pandemic on youths' mental health as well as provide some useful references for policy makers to prevent the occurrence of psychological crisis among university students.

Keywords: Fear and anxiety of Covid-19, Psychological distress, Life satisfaction, Sleep disturbance

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease, popularly known as SARS-CoV-2 or Covid-19, was identified in Wuhan city of China at the end of 2019, which continues to rapidly spread at global scale (Ye et al., 2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) declared it as Public health Emergency of International Concern in January 2020, and then a ‘pandemic’ on 11 March 2020. As 16 December 2020, a total number of 71,581,532 global confirmed cases of Covid-19 with 496,156 new cases and a total of 1,618,374 deaths worldwide were reported (WHO, 2020). This pandemic is not only resulting in deaths globally, but also posing serious threat on mental health such anxiety and fear, psychological distress, sleep disturbance, etc. (Feng et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020). to curb the spread of highly infectious disease, millions of people were forced by most governments around the world to impose lock-down, social and physical distancing, school closing to restrict face-to-face learning and teaching. Approximately 1.5 billion school-going and college students across the world are seriously influenced as a result of the closing down of schools and educational institutions (Hasan & Bao, 2020).

The global pandemic has sparked an unparalleled attention among the scholarly community, the major topics of recent studies about covid-19 have been interested in emergency care, treatment, economic preferences, socio-economic vulnerabilities, global environmental change, e-learning crack-up and so forth (e.g. Hasan & Bao, 2020; Müller & Rau, 2020), however, evaluating the effects of covid-19 pandemic on mental health among uninflected people have been relatively neglected (Lee, 2020). Indeed, during the outbreak of covid-19, everyone in the society have to face with the dual pressure of interpersonal isolation and take account into infection. An examination of psychological status as well as risk antecedents is necessary to carry out target intervention (Wang et al., 2020). Firstly, the association between fear and anxiety of covid-19 and the depression as well as generalized anxiety in adult population has been found in several recent studies (e.g. Daly & Robinson, 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Lee & Crunk, 2020; Ye et al., 2020), yet, studies on psychological impacts of covid-19 is only in the early stages of development. Also, these studies only examined generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms (e.g. Zhang, Wang, et al., 2020; Zhang, Ye, et al., 2020), or only developed a scale to estimate psychological distress related to covid-19 in healthy public (e.g. Feng et al., 2020). Secondly, Jiang et al. (2020) argued that psychological distress was significantly correlated with sleep quality of patients who inflected by covid-19 in Wuhan, while Griffin et al. (2020) also found that there was a significant relationship between mental health and sleep disturbance of safety-net primary care clinic patients. Yet, most prior researches only focused on inflected individuals, there are few studies on discovering the effects of fear and anxiety of covid-19, psychological distress on sleep disturbance among uninflected people, particularly for college students, who dramatically affected by the social distancing, self-isolation, and university closures. Thirdly, individuals' life satisfaction during covid-19 pandemic were interested in recent studies (e.g.: Gori et al., 2020; Rogowska et al., 2020;Zhang, Wang, et al., 2020; Zhang, Ye, et al., 2020). However, several studies only focused on the effects of stress by Covid-19 on life satisfaction (Rogowska et al., 2020) while others considered the impacts of self-compassion and health conditions on life satisfaction (Zhang, Wang, et al., 2020; Zhang, Ye, et al., 2020) or examined the role of life satisfaction on shaping perceived stress, approach coping, positive attitude and mature defenses (Gori et al., 2020). The relationship between fear and anxiety of covid-19 and life satisfaction among college students has not been tested. Finally, some studies were interested in investigating the linkage between psychological distress, sleep disturbance (Chueh et al., 2019) and life satisfaction (Lam & Zhou, 2020; Maria-loanna & Patra, 2020; McCleary-Gaddy & James, 2020). Nevertheless, these relationships were not consistent in recent reports. Lam and Zhou (2020); Maria-loanna and Patra (2020) found that psychological distress was negatively associated with life satisfaction, while McCleary-Gaddy and James (2020) argued that this linkage was not significant. Thus, according to our knowledge, far less has been empirically done on exploring underlying mechanisms that influence how fear and anxiety of covid-19 on specific psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction among youths, particularly for college/university students, who affected seriously by lock-down, social distancing and school closures caused by Covid-19.

The major purpose of this study is to explore the effects of fear and anxiety of covid-19 on psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction among college students in Vietnam. Also, the meditating role of sleep disturbance in the linkages between fear and anxiety of covid-19, psychological distress, and life satisfaction are investigated in this study. The results of the study are expected to have contributions to the literature by enriching our understandings about the impacts of covid-19 pandemic on individuals' mental health, especially for youths.

1.1. Impacts of fear and anxiety of covid-19 on psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction

The relationships between covid-19 and mental health problems have been examined in some recent studies (e.g.: Daly & Robinson, 2020; Feng et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Lee & Crunk, 2020; Saricali et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020;Zhang, Wang, et al., 2020; Zhang, Ye, et al., 2020). However, almost all studies either developed an assessment scale to estimate psychological disorders, fear and anxiety caused by covid-19 (Feng et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020), tested psychological consequences, such as anxiety, depression, and stress of covid-19 (Zhang, Wang, et al., 2020; Zhang, Ye, et al., 2020), estimated the relationship between the fear and psychopathology during covid-19 (Lee & Crunk, 2020), considered the effects of covid-19 on stress and emotional reactions (Levkovich & Shinan-Altman, 2020), evaluated general mental health condition diagnosed by covid-19 (Daly & Robinson, 2020) or focused on specific groups, such as pregnant women (Durankuş & Aksu, 2020), employees (Hamouche, 2020), dental patients (Samuel et al., 2021), children, teenagers and adolescents (Zhang, Wang, et al., 2020; Zhang, Ye, et al., 2020), medical staffs and workers (Luo et al., 2020). Thus, estimating the linkages between fear and anxiety of covid-19, psychological distress, sleep disturbance, and life satisfaction among youths can enrich our knowledge about the effects of covid-19 pandemic on mental health problems.

Fear is determined as a reactive state of emotion to a real or potential threat perceptions, which is associated with surges of autonomic arousal, thoughts about instant danger and escape actions (Kalat & Shiota, 2007). Fear is accompanied by anxiety when attempts to deal with a threat are not successful, these two unlikable states are often experienced together (APA, 2019). Since covid-19 are identified as a contagious and deadly disease, it is also no specific cure or vaccine. Thus, many individuals are undergoing intensified fear and anxiety (Lee & Crunk, 2020). Indeed, the outbreak of any infectious disease is correlated with fear, anxiety, psychological disorders and some other mental illness symptoms (Cheng et al., 2004). Asmundson and Taylor (2020) state that coronaphobia, which is determined as an emotional construct, based on fear and anxiety (APA, 2019; Ohman, 2000), the construct of fear and anxiety of covid-19 were expected to reflect negative psychological impacts and maladaptive because of the covid-19 crisis (Lee et al., 2020). Fear and anxiety of covid-19, therefore, has been considered and combined in a body of recent studies (e.g. Coelho et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020).

The fear and anxiety of covid-19 caused by infectious spread, school closures, social distancing as well as unexpected lockdown can lead to psychological distress and some other negative emotional issues among students (Odriozola-González et al., 2020). Some prior studies have reported that students were anxious and fearful relating to covid-19 infection (e.g. Odriozola-González et al., 2020; Taghrir et al., 2020). Some scholars argue that the development of mental health problems, such as psychological distress or depression can be derived from fear and anxiety of covid-19 (e.g. Lee & Crunk, 2020; Satici et al., 2020) state that while others also emphasized that fear and anxiety is correlated with higher degrees of generalized anxiety and depression in adults (Lee et al., 2020). However, these studies only developed scales to reflect fear, anxiety or depression related to covid-19, but not consider the relationships between fear and anxiety of covid-19 with other constructs.

The interrelation between fear, anxiety and sleep disturbances has been confirmed in a number of studies (Bilsky et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2018). Sleep disturbances become common and chronic symptoms among youths and correlated with the increase of risks regarding of psychological, somatic and depressive problems (Bilsky et al., 2020). Although the correlations between sleep disturbances and a wide array of internalizing issues, such as fear and anxiety, has been well documented, the relationship between sleep issues and anxiety sensitivity appear to be specifically robust (Brown et al., 2018). Moreover, several scholars claimed that psychological effects of other infectious disease (Lee et al., 2016) and covid-19 pandemic (Huang & Zhao, 2020) revealed the higher fear, anxiety, depression and sleep disturbances, thus, these relationships should be examined (Ernsten & Havnen, 2020). To date, no empirically studies have estimated how youth fear and anxiety of covid-19 may related to youth sleep disturbance in public population.

A systematic research has reviewed that self-quarantined individuals during social distancing by covid-19 pandemic suffered from fear and anxiety of being inflected, isolation, which can decrease their life satisfaction (Li et al., 2020). Life satisfaction refers to “the subjective evaluation of current life quality, which is an essential indicator of psychological health and wellbeing” (Li et al., 2020, p.1). Rogowska et al. (2020) suggested that the major changes in everyday routines and practices as well as lifestyle are required to reduce the infectious rates in the communities, such as using face masks, washing hands, physical distancing might affect significantly the development of mental health problems and an increase in negative emotions (anxiety, depression, fear and indignation), which was noted to have significant correlation with life satisfaction (de Pedraza et al., 2020; Gori et al., 2020; Zhang, Wang, et al., 2020; Zhang, Ye, et al., 2020). For Vietnamese youths, the fear and anxiety of covid-19 might be negatively associated with their life satisfaction.

1.2. Impacts of psychological distress on sleep disturbance and life satisfaction

Sleep disturbances become more common in the modern society (Chueh et al., 2019), and these disturbances can be significantly associated with individuals' physical and mental health (Magnavita & Garbarino, 2017). Sleep disturbance might be affected by many antecedents, prior studies have presented a body of crucial factors shaping sleep disturbances among individuals, including sociodemographic and health situations, gender, age (Dong et al., 2017), overweight status (Patel et al., 2008), marital status (Cheung & Yip, 2015). Also, some recent studies indicate that psychological distress affects sleep disturbance (Chueh et al., 2019). Han et al. (2021) revealed that a change in psychological distress and anxiety can lead to short-term sleep disturbance while Cheung and Yip (2015) also emphasize that individual with more severe anxiety and depression have greater degree of sleep disturbance. Moreover, although the correlation between psychological distress and sleep disturbances has been documented in previous studies (Chueh et al., 2019; Duraku et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020; Griffin et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020), almost all these studies only focused on either nurses (Chueh et al., 2019); patients (Griffin et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020), or adolescents (Duraku et al., 2020). Kalyani et al. (2017) argue that estimating the effect of psychological distress on sleep disturbance among young population, especially for college students, is needed to preserve the ‘health of the society’ later generations.

Life satisfaction that refers people's general judgment of their psychological well-being as well as quality of life, also consists of emotional and cognitive assessment of an individual's life (Diener et al., 1985). Psychological distress stands in contrast with life satisfaction by showing a negatively emotional form (Lam & Zhou, 2020). Psychological distress also indicates unpleasant emotional reactions to stressful status, such as emotions that a status is uncontrolled and overwhelmed (Cohen & Williamson, 1988). The association between psychological distress and life satisfaction has been acknowledged in previous studies, however, the findings of these studies were mixed and inconsistent. Indeed, many studies indicated that psychological distress has a negative correlation with life satisfaction (Lam & Zhou, 2020; Marum et al., 2014; McCleary-Gaddy & James, 2020; Satici et al., 2020). Also, Maria-loanna and Patra (2020) suggest that students, who had more anxiety, psychological distress, and depressive symptoms, tend to be less satisfied with life. However, Zhi et al. (2016) argued that psychological distress was positively associated with life satisfaction. In the context of Vietnam, where the social distancing measures of the government was strictly implemented to restrict the spread of covid-19 pandemic, psychological distress can reduce students' life satisfaction.

1.3. Impact of sleep disturbance on life satisfaction

Sleep disturbances is often comorbid with mental and physical health, these symptoms not only decrease the quality of life, but they might also aggravate mental and physical illness, reduce the life satisfaction, and raise the risk of mortality (Kim & Ko, 2018). In addition, life satisfaction is popularly utilized as a great indicator to show individuals' general well-being (Diener et al., 1985), and it has been found to have correlations with perceived stress, psychological distress and self-efficacy in many previous researches (e.g. Coffman & Gilligan, 2002; Lee et al., 2016). However, the underlying mechanism in which life satisfaction internalize sleep disturbance has not answered clearly (Kim & Ko, 2018; Wang & Boros, 2020), especially for university students (Lund et al., 2010), although the important role of sleep for well-being and quality of life has been documented for another groups, such as elderly people (Kim & Ko, 2018; Zhi et al., 2016), athletes (Litwic-Kaminska & Kotyśk, 2017), Parkinson's disease caregivers (Perez et al., 2020), and euthymic patients (De la Fuente-Tomás et al., 2018). Thus, more studies examining the linkage between sleep problems and life satisfaction in university students is needed. In the context of Vietnam, although the spread of covid-19 pandemic is relatively well-controlled, university students are required to stay at home, study online as well as comply with strict physical distancing. Thus, they can have to face with psychological distress, sleep problems, and life dissatisfaction.

1.4. Proposed conceptual model and hypotheses

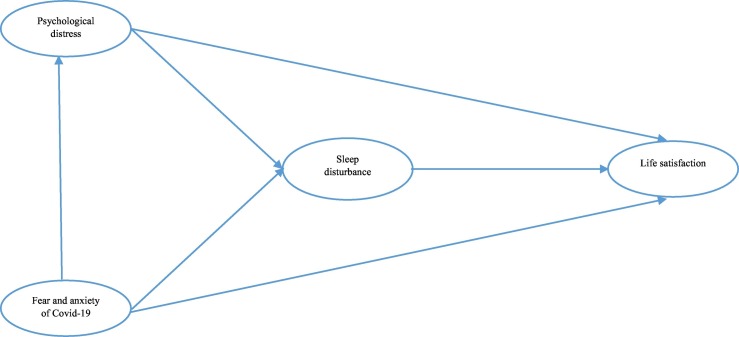

The present study aims to examine the impact of fear and anxiety of covid-19 on psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction as well as explore the mediating roles of psychological distress and sleep disturbance in this linkage (Fig. 1). Based on the above literature review, the current research proposed six hypotheses:

H1

Fear and anxiety of covid-19 is positively related to psychological distress among university students in Vietnam.

H2

Fear and anxiety of covid-19 is positively related to sleep disturbances among university students in Vietnam.

H3

Fear and anxiety of covid-19 is negatively related to life satisfaction among university students in Vietnam.

H4

Psychological distress is positively related to sleep disturbances among university students in Vietnam.

H5

Psychological distress is negatively related to life satisfaction among university students in Vietnam.

H6

Sleep disturbances are negatively related to life satisfaction among university students in Vietnam.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Measures and questionnaire development

To estimate the effects of fear and anxiety of covid-19 on psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction. The survey approach was adopted in this study for data collection. Also, all the constructs in this research were measured by scales which has been used in previous studies. Particularly, the five-item scale measuring “fear and anxiety of covid-19” was adapted from Lee et al. (2020), using a five-point time anchored scale (1 = not at all to 5 = nearly every day over the last two weeks). The measure of “psychological distress”, including ten items, are modified from Kessler psychological distress scale (K10) (Kessler et al., 2003), utilizing five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The six-item scale of “sleep disturbance” (PROMIS 6-item Sleep Disturbance Scale) is adopted from Full et al. (2019), this scale includes six items, such as “my sleep quality was…”, “my sleep was refreshing…”, “I had a problem with my sleep”, “I had difficulty falling asleep”, “my sleep was restless…”, and “I tried to get to sleep…”. All items have a five-point response, however, the first item rated from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very good) while remaining items ranked from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The five-item scale of “life satisfaction” as modified from Diener et al. (1985) with five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

In this study, the questionnaire, that consists all the scale items measuring four constructs in the conceptual framework, has been developed. In addition, some demographic question, such as age, gender, fields and years of study, monthly income, and a diagnosis with mental health was included at the final section of questionnaire. Also, the definition of mental health, psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction has been shortly explained in the beginning of the questionnaire to ensure that students have common understanding about these issues. As the target respondents are students in Vietnam, therefore, the scale items were first translated into Vietnamese from original English version. Specifically, the translation of English langue version to Vietnamese has been initially checked by bilingual researchers to guarantee the accuracy of language and meaning. Also, some local terms has been identified for conditions of interest whereas materials has been adapted to fit local idioms, images and circumstances. Some words, therefore, have been modified to more appropriate to the Vietnamese context. Then, the questionnaire instrument was back-translated into English to ensure the consistence of original and translational versions. After that, field test with a small group of respondents was conducted in order to secure that all items (statements) were completely comprehended by respondents. Finally, the final version of questionnaire has been distributed to university students.

2.2. Sample

The convenient sampling method was utilized in the present study. The online-based cross-sectional survey was carried out between September 20 and October 30 in Vietnam. Although almost cities in Vietnam have been allowed to relax social distancing measures at this time, the government still set certain restrictions, such as wearing masks and keeping a safe distance, prohibiting bars, karaoke, and game centers. Thus, using online data collection tool throughout social media during the covid-19 pandemic is more appropriate (Deniz, 2021; Han et al., 2021). Firstly, an instrument of anonymous online survey was developed to ensure that personal information was kept in confidence and circulated via online communications, such as messenger and public groups of Facebook, Zalo and Viber, and personal emails. Secondly, the participants were informed clearly that they were voluntary to participate in fulfilling the survey, their responses would have been confidential and secure, the data only used for academic purposes. 5000 online questionnaires have been directly delivered to personal emails, Facebook, Zalo, and Viber of university students in order to invite them to participate in the survey. Then, 1601 questionnaires have been answered, the response rate accounted for 32.02%. However, to improve the quality of data, the study decided to extract all responses that had missing values. Finally, after eliminating 80 invalid responses, the final valid data was 1521 undergraduate students (95.003%) recruited from various universities in Vietnam was utilized for analyses. Holmes (1983) suggested that at least 115 valid responses for total sample size (applied psychology) is a need to analyze effectively and efficiently. Therefore, the sample of 1521 response met the requirement for data analysis.

2.3. Analytical approach

The study conducted confirmatory factor analysis utilizing AMOS 24.0 and multiple regression analysis with bootstrapping using SPSS 24.0. Firstly, descriptive statistics was conducted to show the mean, standard deviation (SD) and examine normality of each research variables. Univariate normality was assessed by using skewness-kurtosis values, all items in the scales should have a skewness value of lower than 3 and the kurtosis value of less than 8 (Hair et al., 2010). Secondly, Cronbach's alpha and exploratory factor analysis were employed to examine the internal consistency reliability of each variable. All factors were also able to have an acceptable value when the Cronbach's alpha is higher than 0.63 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994) and the Corrected Item-Total Correlation of each item should be higher than 0.3 (Hair et al., 2010). Thirdly, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and regression analysis with PROCESS approach (Preacher & Hayes, 2004) were also employed to analyze the collected data. Confirmatory factor analysis, that was utilized to examine the reliability and validity of the scales for measuring the constructs, was adopted since this approach might be employed to test whether measures of a construct with the nature of that construct (Peláez-Fernández et al., 2019), and has been widely utilized in social studies (Hair et al., 2010). Goodness of fit of measurement model was considered utilizing χ2 (Chi-square Statistics), χ2/DF (Chi-Square/Degree of Freedom), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index), GFI (Goodness-of-Fit), AGFI (Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index), NFI (Normed-Fit Index) and RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation). χ2 and χ2/DF are sensitive to sample size (Jӧreskog & Moustaki, 2001), the CFI, TLI and RMSEA were used. A CFI over 0.90 is ideal (Browne & Cudeck, 1993), exceeding 0.95 is an excellent fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). RMSEA value is lower than 0.05 presenting a good fit, while this value is between 0.05 and 0.08 indicating a moderate fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). In addition, a structural equations method essentially can be considered to analyze the data in this research. However, utilizing measures to construct the interaction terms in a structural equations model is seen as a complex process, and lacks a measure with which to examine the multicollinearity level (Peláez-Fernández et al., 2019). Also, structural equation model (SEM) relies on maximum likelihood estimation that requires multivariate normality (Jackson, 2003), something that was not satisfied by the data (Doornik & Hansen, 2008). PROCESS macro approach (Preacher & Hayes, 2004), which has been previously validated and adopted (e.g. Duchesne et al., 2017; Peláez-Fernández et al., 2019) and has the advantage of ease of interpretation, allows for simultaneous estimation of multiple mediators (Duchesne et al., 2017). Thus, instead of utilizing a structural equation model, this study employed the regression analysis with PROCESS macro approach to estimate the proposed models. Finally, the study adopted bootstrapped standard errors with 10,000 bootstrap sample and 95% confidence interval to assess the mediating effects.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics

As illustrated in Table 1 , less than half (43.3%) of the students are male. Also, most of participants aged from 18 to 20 years old, accounted for 82.8%, followed by who aged from 21 to 23 (15.8), and over 23 years old (just 1.3%). The percentage of respondents aged more than 23 years old only accounted for 1.3% because almost university students in Vietnam enroll in universities at age from 18 to 22 years old. 52.3% students are studying in economics and business management fields. More than a half of participants are first and second-year students (57.5%). However, most of students (66.0%) have monthly income (included family financial supports) less than 3,000,000 VND, this result reflects that almost students only can spend around 130 USD each month with financial support from their families. However, this spending is rather suitable for students in Vietnam. Finally, 15.1% of respondents from student sample was diagnosed with a mental health problem.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

| Social-demographic information | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 658 | 43.3 |

| Female | 863 | 56.7 | |

| Age | From 18 to 20 years old | 1260 | 82.8 |

| From 21 to 23 years old | 241 | 15.8 | |

| Over 23 years old | 20 | 1.3 | |

| Fields of study | Economics and business management | 796 | 52.3 |

| Engineering and others | 725 | 47.7 | |

| Years of study | First year | 292 | 19.2 |

| Second year | 583 | 38.3 | |

| Third year | 454 | 29.8 | |

| Final year | 192 | 12.6 | |

| Monthly income (family financial supports included) | <3,000,000 VND | 1004 | 66.0 |

| 3,000,000–7,000,000 VND | 428 | 28.1 | |

| 7,000,000–10,000,000 VND | 49 | 3.2 | |

| >10,000,000 | 40 | 2.6 | |

| Have you been diagnosed with a mental health problem? | Yes | 230 | 15.1 |

| No | 1291 | 84.9 | |

Note: N = 1521, 1 USD = 23,148.00 VND (exchange rate on 16 December 2020).

3.2. Normality test and scale assessments

The univariate normality of scales has been tested via a Skewness-Kurtosis method; the results show that these scales were found in their promising value (Hair et al., 2010). Also, the Cronbach's alpha and exploratory factory analysis (EFA) were utilized to examine the reliabilities and validities of scales. Table 2 illustrated the results of Cronbach's alpha and pattern matrix. All variables were found to have expected values with the lowest level of 0.786 (αSD = 0.786), therefore, the internal consistency reliabilities of all scales were satisfactory (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Then, all these items were subjected to exploratory factor analysis with principal axis factoring method and promax rotation. Totally, four factors were drawn with a total extracted variance of 58.725% and KMO value of 0.909.

Table 2.

Cronbach's alpha, pattern matrix and descriptive characteristics of variables.

| Code | Variables | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Cronbach's alpha | Factor |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |||||||

| FAC | Fear and anxiety of Covid-19 (Lee et al., 2020) | 2.2325 | 0.76827 | 0.533 | 0.558 | 0.852 | ||||

| FAC1 | I felt dizzy, lightheaded, or faint when I read or listened to news about the coronavirus | 2.4497 | 1.03822 | 0.394 | −0.659 | 0.841 | 0.633 | |||

| FAC2 | I had trouble falling or staying asleep because I was thinking about the coronavirus | 2.2945 | 0.95492 | 0.540 | −0.220 | 0.816 | 0.759 | |||

| FAC3 | I felt paralyzed or frozen when I thought about or was exposed to information about the coronavirus | 2.4109 | 1.03497 | 0.492 | −0.460 | 0.809 | 0.777 | |||

| FAC4 | I lost interest in eating when I thought about or was exposed to information about the coronavirus | 2.1308 | 0.95730 | 0.813 | 0.336 | 0.814 | 0.786 | |||

| FAC5 | I felt nauseous or had stomach problems when I thought about or was exposed to information about the coronavirus | 1.8764 | 0.84789 | 1.139 | 1.795 | 0.828 | 0.724 | |||

| PD | Psychological distress (Kessler et al., 2003) | 2.5465 | 0.84791 | 0.368 | −0.185 | 0.934 | ||||

| PD1 | I often feel tired out for no good reason | 2.8632 | 1.11908 | 0.113 | −0.964 | 0.933 | 0.686 | |||

| PD2 | I often feel nervous | 2.8988 | 1.07189 | 0.042 | −0.889 | 0.929 | 0.757 | |||

| PD3 | I often feel so nervous that nothing could calm me down | 2.3715 | 0.99509 | 0.588 | −0.219 | 0.927 | 0.725 | |||

| PD4 | I often feel hopeless | 2.4221 | 1.09875 | 0.580 | −0.430 | 0.924 | 0.832 | |||

| PD5 | I often feel restless or fidgety | 2.5076 | 1.05324 | 0.432 | −0.558 | 0.926 | 0.757 | |||

| PD6 | I often feel so restless that I could not sit alone | 2.2498 | 0.97030 | 0.704 | 0.077 | 0.929 | 0.677 | |||

| PD7 | I often feel depressed | 2.7114 | 1.11930 | 0.188 | −0.882 | 0.924 | 0.863 | |||

| PD8 | I often feel that everything is not effort | 2.5595 | 1.09930 | 0.391 | −0.685 | 0.924 | 0.847 | |||

| PD9 | I often feel so sad that nothing could cheer me up | 2.3688 | 1.05571 | 0.609 | −0.338 | 0.927 | 0.762 | |||

| PD10 | I often feel worthless | 2.5128 | 1.11273 | 0.434 | −0.613 | 0.929 | 0.724 | |||

| SD | Sleep disturbance (Full et al., 2019) | 2.6226 | 0.84791 | 0.181 | 0.469 | 0.786 | ||||

| SD1 | Quality sleep | 2.7028 | 0.88692 | −0.017 | −0.121 | 0.754 | 0.648 | |||

| SD2 | Refreshing | 2.6529 | 0.94754 | 0.095 | −0.409 | 0.734 | 0.804 | |||

| SD3 | Problem with sleep | 2.6614 | 1.01522 | 0.141 | −0.582 | 0.754 | 0.614 | |||

| SD4 | Difficulty failing asleep | 2.5082 | 1.02217 | 0.259 | −0.506 | 0.754 | 0.592 | |||

| SD5 | Restless | 2.7364 | 1.10420 | 0.097 | −0.742 | 0.762 | 0.508 | |||

| SD6 | Tried hard to get to sleep | 2.4740 | 1.05232 | 0.289 | −0.541 | 0.766 | 0.510 | |||

| LS | Life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1985) | 3.2034 | 0.69965 | −0.289 | 0.320 | 0.787 | ||||

| LS1 | In most ways my life is close to my ideal | 2.7364 | 0.93586 | 0.151 | −0.471 | 0.745 | 0.673 | |||

| LS2 | The conditions of my life are excellent | 3.0434 | 0.92093 | −0.172 | −0.357 | 0.716 | 0.781 | |||

| LS3 | I am satisfied with my life | 3.2525 | 0.95664 | −0.400 | −0.328 | 0.716 | 0.757 | |||

| LS4 | So far I have gotten the important things I want in life | 3.7686 | 0.88054 | −0.852 | 0.909 | 0.779 | 0.527 | |||

| LS5 | If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing | 3.2163 | 1.05688 | −0.162 | −0.647 | 0.775 | 0.554 | |||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy | 0.909 | |||||||||

| Sig. (Bartlett's test of sphericity) | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Cumulative (%) | 58.725 | |||||||||

| The value of initial Eigenvalue | 2.003 | |||||||||

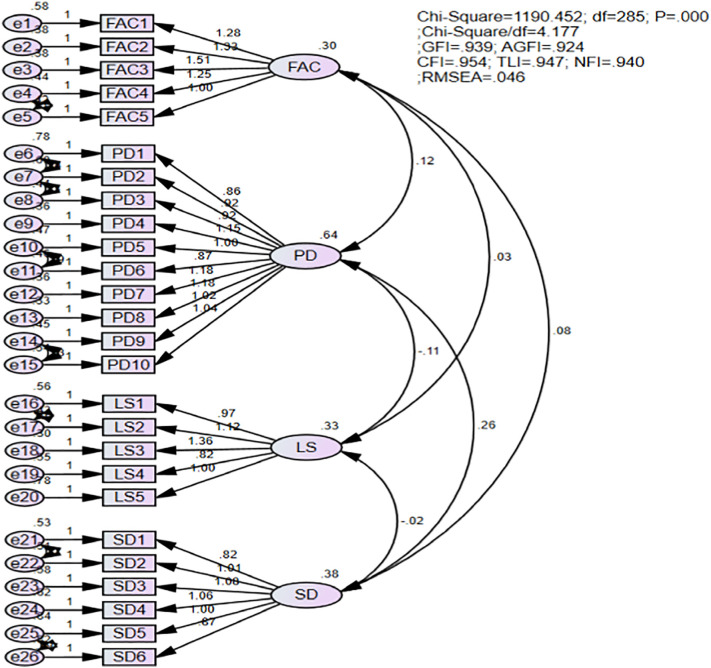

To assess the convergent validity and discriminant validity of all scales in the research model, the measurement models were estimated. The initial measurement model was constructed consisting of all observed variables as indicators. As indicated in Fig. 2 , results of confirmatory factor analysis (CAF), utilizing AMOS 24.0 software, illustrated a good level of fit. All t-test of observed variables were significant at the 0.001 level. Specifically, χ2(285) = 525.278; CMIN/DF = 4.177 < 5; p < 0.01; GFI = 0.939 > 0.9; AGFI = 0.924 > 0.9; CFI = 0.954 > 0.9; TLI = 0.947 > 0.9; NFI = 0.940 > 0.9 and RMSEA = 0.072 < 0.5 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Fig. 2.

Measurement model.

Moreover, Average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) were estimated to demonstrate the reliability, convergent and discriminant validity of variables (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Hair et al., 2010). As illustrated in Table 3 , CR values for all constructs were noted to be higher than 0.7. Although AVE value of “sleep disturbance” and “life satisfaction” only accounted for 0.362 and 0.420 respectively, these values could be accepted (e.g. Ertz et al., 2016). All scales represented good discriminant validities because the square root of average variance extracted (AVE-the diagonal values) for each construct was higher than the inter-construct correlations (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) also indicated that all items were able to have a standardized regression weight higher than 0.5, SD6 had the lowest value at 0.512.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix, construct reliability and discriminant validity.

| CR | AVE | Pearson correlations |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | FAC | LS | SD | |||

| Psychological distress | 0.932 | 0.579 | 1 | |||

| Fear and anxiety of covid-19 | 0.846 | 0.526 | 0.262⁎⁎ | 1 | ||

| Life satisfaction | 0.779 | 0.420 | −0.170⁎⁎ | 0.088⁎⁎ | 1 | |

| Sleep disturbance | 0.771 | 0.362 | 0.451⁎⁎ | 0.209⁎⁎ | −0.032 | 1 |

Notes: **: significant at 0.01 level (two-tailed); AVE: average variance extracted; CR: composite reliability.

3.3. Regression analyses

The results of hypothesis test by utilizing regression analyses were revealed in Table 3, Table 4 . These results might have been contaminated by the concern of multicollinearity because Table 3 showed that correlation coefficient of sleep disturbance and psychological distress were higher than 0.5. Thus, the variance inflation factor (VIF) of independent variables was computed to examine the degree of multicollinearity in this study. The results in the last column in Table 4 revealed that the values of VIF of all independent variables were lower than 4 (Hair et al., 2010), confirming that the model estimations did not have a multicollinearity bias.

Table 4.

Regression results for fear and anxiety of covid-19, psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction.

| Variables | Psychological distress |

Sleep disturbance |

Life satisfaction |

VIF | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

Model 7 |

Model 8 |

Model 9 |

||

| β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | ||

| Intercept | 3.361⁎⁎⁎ | 2.722⁎⁎⁎ | 2.866⁎⁎⁎ | 2.445⁎⁎⁎ | 1.508⁎⁎⁎ | 2.688⁎⁎⁎ | 2.521⁎⁎⁎ | 2.919⁎⁎⁎ | 2.863 | |

| (0.170) | (0.173) | (0.143) | (0.148) | (0.146) | (0.141) | (0.149) | (0.159) | (0.164) | ||

| Gender | −0.020 | −0.011 | −0.007 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.049 | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 1.009 |

| (0.043) | (0.041) | (0.036) | (0.035) | (0.032) | (0.036) | (0.036) | (0.035) | (0.035) | ||

| Age | 0.028 | 0.006 | −0.065 | −0.079 | −0.081 | −0.095 | −0.101 | −0.100 | −0.097 | 1.609 |

| (0.064) | (0.061) | (0.054) | (0.052) | (0.048) | (0.053) | (0.053) | (0.052) | (0.052) | ||

| Fields of study | 0.064 | 0.062 | 0.029 | 0.027 | 0.006 | −0.129⁎⁎⁎ | −0.130⁎⁎⁎ | −0.100⁎⁎ | −0.121⁎⁎ | 1.010 |

| (0.043) | (0.041) | (0.036) | (0.035) | (0.032) | (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.035) | ||

| Years of study | 0.026 | 0.040 | 0.060⁎ | 0.069⁎⁎ | 0.055⁎⁎ | 0.017 | 0.021 | 0.027 | 0.025 | 1.570 |

| (0.029) | (0.027) | (0.024) | (0.023) | (0.021) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.023) | (0.023) | ||

| Monthly income | 0.003 | 0.012 | 0.038 | 0.036 | 0.036 | 0.107⁎⁎⁎ | 0.107⁎⁎⁎ | 0.107⁎⁎⁎ | 0.105⁎⁎⁎ | 1.061 |

| (0.032) | (0.031) | (0.027) | (0.026) | (0.024) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | ||

| Mental health problems | −0.530⁎⁎⁎ | −0.549⁎⁎⁎ | −0.213⁎⁎⁎ | −0.226⁎⁎⁎ | −0.037 | 0.297⁎⁎⁎ | 0.292⁎⁎⁎ | 0.211⁎⁎⁎ | 0.213⁎⁎⁎ | 1.072 |

| (0.059) | (0.057) | (0.050) | (0.049) | (0.046) | (0.049) | (0.049) | (0.050) | (0.050) | ||

| Fear and anxiety of covid-19 | 0.298⁎⁎⁎ | 0.196⁎⁎⁎ | 0.093⁎⁎⁎ | 0.078⁎⁎ | 0.121⁎⁎⁎ | 0.118⁎⁎⁎ | 1.100 | |||

| (0.027) | (0.023) | (0.022) | (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.024) | |||||

| Psychological distress | 0.344⁎⁎⁎ | −0.146⁎⁎⁎ | −0.159⁎⁎⁎ | 1.368 | ||||||

| (0.020) | (0.022) | (0.024) | ||||||||

| Sleep disturbance | 0.037 | 1.277 | ||||||||

| (0.028) | ||||||||||

| N (observations) | 1521 | 1521 | 1521 | 1521 | 1521 | 1521 | 1521 | 1521 | 1521 | 1.009 |

| F-value | 14.700⁎⁎⁎ | 31.582⁎⁎⁎ | 4.956⁎⁎⁎ | 15.098⁎⁎⁎ | 52.369⁎⁎⁎ | 11.656⁎⁎⁎ | 11.706⁎⁎⁎ | 16.152⁎⁎⁎ | 14.566⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.051 | 0.123 | 0.015 | 0.061 | 0.213 | 0.040 | 0.047 | 0.074 | 0.074 | 1.609 |

| Durbin-Watson | 1.928 | 1.934 | 1.911 | 1.933 | 1.903 | 1.949 | 1.944 | 1.913 | 1.918 | |

Note: results are based on trimmed scales. VIF: variance inflation factor. The figures in parentheses are standard errors.

Variables and correlations with statistical significance were highlighted in bold.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

The linkage between fear and anxiety of covid-19 and psychological distress was tested first, corresponding to hypothesis 1, controlling for gender, age, fields of study, years of study, monthly income, mental health problems. Results were represented in Table 4, models 1 and 2. Fear and anxiety of covid-19 was positively related to psychological distress (β = 0.298, p < 0.001). Thus, H1 received support from the data. Also, model 5 tested the hypotheses regarding effects of fear and anxiety of covid-19 and psychological distress on sleep disturbance, including control variables (model 3). Results demonstrated that sleep disturbance was positively affected by fear and anxiety of covid-19 (β = 0.093, p < 0.001) and psychological distress (β = 0.344, p < 0.001), lending support for H2 and H4. In addition, model 9, that tested the hypotheses concerning the impacts of fear and anxiety of covid-19, psychological distress, and sleep disturbance, consisted of control variables (model 6) and referred to hypotheses 3, 5 and 6. Although, the correlation between fear and anxiety of covid-19 and life satisfaction was significant (β = 0.118, p < 0.001), this linkage is positive. In other words, fear and anxiety of covid-19 increase university students' life satisfaction instead of reducing life satisfaction as expected. Therefore, H3 was not supported by the data. Psychological distress was noted to negatively affect life satisfaction (β = −0.159, p < 0.001) while the impact of sleep disturbance on life satisfaction was not significant (p > 0.05). Thus, H5 received support from the date whereas H6 was not supported.

Among the control variables, psychological distress and life satisfaction were negatively controlled by a diagnosis with mental health problem (β = −0.549, p < 0.001), but sleep disturbance was not (model 5) (p > 0.05). There were no effects of gender, age, years of study and monthly income on psychological distress and sleep disturbance (p > 0.05). However, life satisfaction was negatively influenced by fields of study (β = −0.121, p < 0.001) and positively affected by monthly income (β = 0.105, p < 0.001).

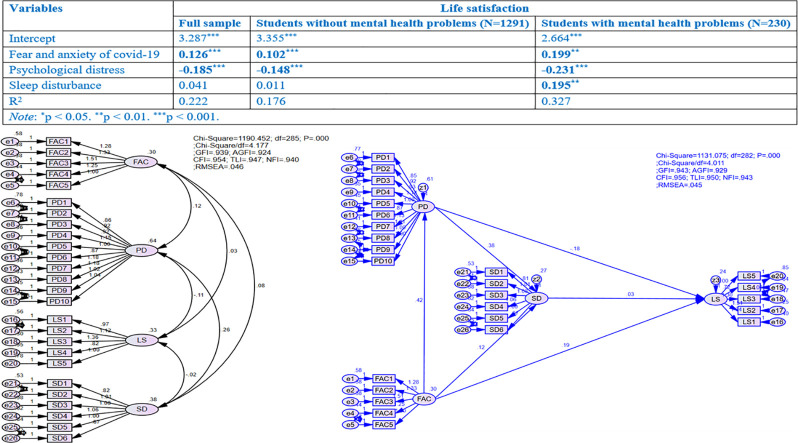

Table 5 interpreted the output from correlations without controlling variables for full sample and two compared groups (healthy individuals versus those with mental health problems). The results showed that the influential degrees of fear and anxiety of covid-19, psychological distress, and sleep disturbance on life satisfaction among students, who diagnosed with mental health problems, were much higher than that of those without mental health issues. Particularly, fear and anxiety of covid-19 among students with mental health problems was more associated with life satisfaction (β = 0.199, p = 0.002 < 0.01), compared to healthy individuals (β = 0.102, p = 0.002 < 0.01). Also, psychological distress among students with mental health issues was more negatively correlated with life satisfaction (β = −0.231, p < 0.001), compared to students without psychological problems (β = −0.148, p < 0.001). Surprisingly, while the relationship between sleep disturbance and life satisfaction among healthy students was not significant (β = 0.011, p = 0.072 > 0.05), sleep disturbance was found to have significant impact on life satisfaction among students diagnosed with mental health issues (β = 0.195; p = 0.005 < 0.01).

Table 5.

Pearson correlation coefficient between two groups.

| Variables | Life satisfaction |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | Students without mental health problems (N = 1291) | Students with mental health problems (N = 230) | |

| Intercept | 3.287⁎⁎⁎ | 3.355⁎⁎⁎ | 2.664⁎⁎⁎ |

| Fear and anxiety of covid-19 | 0.126⁎⁎⁎ | 0.102⁎⁎⁎ | 0.199⁎⁎ |

| Psychological distress | −0.185⁎⁎⁎ | −0.148⁎⁎⁎ | −0.231⁎⁎⁎ |

| Sleep disturbance | 0.041 | 0.011 | 0.195⁎⁎ |

| R2 | 0.222 | 0.176 | 0.327 |

Variables and correlations with statistical significance were highlighted in bold.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

The results of the mediation test with PROCESS macro approach and 10,000 bootstrap sample and 95% confidence interval were illustrated in Table 6 . Results showed that fear and anxiety of covid-19 reduced life satisfaction via psychological distress (βindirect effect = −0.0494, p < 0.05). Also, fear and anxiety of covid-19 increased sleep disturbance throughout psychological distress (βindirect effect = 0.1013, p < 0.05). In contrast, the relationship between fear and anxiety of covid-19, psychological distress and life satisfaction were not mediated by sleep disturbance (p > 0.05).

Table 6.

The mediating tests of psychological distress and sleep disturbance.

| Mediation standardized regression coefficients | Indirect effects | SE | 95% confidence interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Fear and anxiety of covid-19 → psychological distress → life satisfaction | −0.0494⁎ | 0.0090 | −0.0680 | −0.0326 |

| Fear and anxiety of covid-19 → sleep disturbance → life satisfaction | −0.0099 | 0.0238 | −0.0232 | 0.0027 |

| Fear and anxiety of covid-19 → psychological distress → sleep disturbance | 0.1013⁎ | 0.0139 | 0.0753 | 0.1296 |

| Psychological distress → sleep disturbance → life satisfaction | 0.0210 | 0.0134 | −0.0049 | 0.0476 |

Note: LLCI: lower level of confidence interval. ULCI: upper level of confidence interval. SE: standard errors.

Variables and correlations with statistical significance were highlighted in bold.

p < 0.05.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The present study examined the impacts of fear and anxiety of covid-19 on psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction among university students in Vietnam. Beside these direct effects, this study also focused on exploring the mediating roles of psychological distress in the linkages between fear and anxiety of covid-19, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction. Six hypotheses were tested and only four received support from the data. Hypothesis tests were summarized in Table 7 .

Table 7.

Summary of hypothesis tests.

| Hypotheses | Results |

|---|---|

| H1. Fear and anxiety of covid-19 is positively related to psychological distress among university students in Vietnam. | Supported |

| H2. Fear and anxiety of covid-19 is positively related to sleep disturbances among university students in Vietnam. | Supported |

| H3. Fear and anxiety of covid-19 is negatively related to life satisfaction among university students in Vietnam. | Not supported |

| H4. Psychological distress is positively related to sleep disturbances among university students in Vietnam. | Supported |

| H5. Psychological distress is negatively related to life satisfaction among university students in Vietnam. | Supported |

| H6. Sleep disturbances are negatively related to life satisfaction among university students in Vietnam. | Not supported |

The findings confirmed the fear and anxiety of covid-19 play the significant and positive role in predicting psychological distress and sleep disturbance. These results were consistent with findings of many previous studies (e.g. Bilsky et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2018; Lee & Crunk, 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Samuel et al., 2021; Saravanan et al., 2020; Satici et al., 2020). For instance, Saravanan et al. (2020) found that fear and anxiety of covid-19 was strong and positive correlated with psychological distress whereas Babson (2015) confirmed that there were the interactions between sleep disturbance and general fear/anxiety.

Contrary to our expectation, the negative impact of fear and anxiety of covid-19 on life satisfaction failed to receive support from Vietnam data. This finding is also contrary to many prior studies, which represented that fear, anxiety, and depression was detected to have negative impacts on life satisfaction (e.g: de Pedraza et al., 2020; Gori et al., 2020; Zhang, Wang, et al., 2020; Zhang, Ye, et al., 2020). Indeed, Gawrych et al. (2021) confirmed that there was a dramatic medium reduction in the degree of residents' life satisfaction and well-being in Poland during the covid-19 pandemic while de Pedraza et al. (2020) also conducted a cross-country study (25 advanced and developing economies) and their findings showed that there was an increase in life dissatisfaction and anxiety due to forced social distancing. Yet, this present study showed that fear and anxiety of covid-19 was positively correlated with life satisfaction in the context of Vietnam. It means that those students with high degree of fear and anxiety of covid-19, while perceiving a potential threat of covid-19 pandemic and experiencing strict physical distancing, might recognize the real values of life, such as work-life balance, and satisfy with their lives. Also, it can reflect the excellent results, which is derived from the effective control of the spread of covid-19 in Vietnam (Nguyen & Vu, 2020; Quach & Hoang, 2020). However, for better understanding, this problem should be further considered in the further studies.

Notably, while sleep disturbance was not detected to have associations with life satisfaction in the context of Vietnam. This finding is inconsistent with prior studies (De la Fuente-Tomás et al., 2018; Kim & Ko, 2018). For example, Kim and Ko (2018) indicated that life satisfaction was negatively affected by sleep disturbance among older Korean adults. The results also showed that university students' life satisfaction was dramatically and negatively affected by psychological distress. This is consistent with the findings of recent studies (e.g.: Lam & Zhou, 2020; Marum et al., 2014; McCleary-Gaddy & James, 2020; Satici et al., 2020). However, prior studies did not consider this linkage in the context of covid-19 epidemic. Indeed, Zhi et al. (2016) examined the psychological distress and life satisfaction of the elderly while Marum et al. (2014) tested this relationship with a population-based sample. Moreover, as for Vietnamese students, psychological distress was found to play the mediating role in associations between fear and anxiety of covid-19, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction.

From a theoretical perspective, this study explores a recent topical issue pertaining to the effects of covid-19 on mental health among young population in the context of Vietnam. The research findings contribute to enrich our understanding about the impacts of fear and anxiety of covid-19 on psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction among youths. Also, this research enhances our knowledge of debatable correlations between psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction. Firstly, this study has adequately adopted and validated the scale “fear and anxiety of covid-19”, developed by Lee et al. (2020), and the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10), proposed by Kessler et al. (2003) in a new setting and context of Vietnam, especially for university students. Secondly, the proposed conceptual framework was added to the newly introduced factors that estimated notable outcomes in the literature on life satisfaction and psychological distress for university students under the influence of covid-19 pandemic. None of existing studies on the effects of fear and anxiety of covid-19 on psychological distress in general, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction. Thirdly, this research confirmed that psychological distress was negatively related to life satisfaction and positively referred to sleep disturbance. These correlations were debatable in recent studies. Fourthly, the significant association between fear and anxiety of covid-19 and life satisfaction was detected in this study while none of standing studies examined this relationship, according to our best knowledge. Besides, this study illustrated that psychological distress significantly mediated the relations between fear and anxiety of covid-19, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction. Particularly, fear and anxiety of covid-19 lowered life satisfaction and raised sleep disturbance through psychological distress. Finally, this present study is the first experimental evidence demonstrating that the influential levels of fear and anxiety of covid-19, sleep disturbance, and psychological distress on life satisfaction among individuals with mental illness were much stronger than that of those with healthy ones.

From a practical perspective, this research is the first one to reflect fear and anxiety of covid-19 as well as its impacts on psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction among university students in Vietnam as a result of school closures, social distancing, unnecessary service closures during the covid-19 pandemic. This study can help the government and education policymaker to realize the serious effects of covid-19 pandemic on university students' mental health problems and provides them useful references to take more appropriate actions and more effective interventions for students to prevent the occurrence of psychological distress during and after disease outbreaks (Jiang, 2020). Also, the findings of this research would also discover the understanding of knowledge about the correlated antecedents that predicted life satisfaction among Vietnamese students. From research results, we can conclude that fear and anxiety of covid-19 can reduce university students' life satisfaction via psychological distress. Thus, to increase the life satisfaction among students, beside effective means of controlling the spread of covid-19 pandemic, the government should have applicable policies to decrease psychological distress among youths.

Even though this research provides a significant outcome, there are several limitations. Firstly, dataset was collected utilizing a cross-sectional online survey. Thus, the generalization of the conclusions can be reduced, further studies can carry out other sampling methods, such as probability or random sampling to increase the confidence of the research. Secondly, no follow-up survey was performed to have further knowledge of the development of fear and anxiety of covid-19, psychological distress, sleep disturbance and life satisfaction of this group. Further studies can utilize tracking test method for deep research. Finally, the current research only explores the linkages between fear and anxiety of covid-19, psychological distress, sleep disturbance, and life satisfaction, further studies should expand the conceptual model to discover the impacts of covid-19 pandemic on the human society.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration: Doanh DUONG CONG. Funding acquisition: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statement

The participants were informed clearly that they were voluntary to participate in fulfilling the survey, their responses would have been confidential and secure, the data only used for academic purposes.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express sincere thanks to university students for fulfilling and sharing the survey to collect dataset. This research was supported by National Economics University, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110869.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

. This is open data under the CC BY license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

- Anderson J.C., Gerbing D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(3):411–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- APA (American Psychological Association) Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three age cohorts: American Psychological Association guideline Lee and Crunk 11 development panel for the treatment of depressive disorders. 2019. https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline/guideline.pdf

- Asmundson G., Taylor S. Coronaphobia revisted: A state-of-the-art on pandemic-related fear, anxiety, and stress. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;76:102326. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babson K.A. Sleep and affect. Elsevier; 2015. Chapter 7-The interrelations between sleep and fear/anxiety: Implications for behavior treatment. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsky S.A., Friedman H.P., Karlovich A., Smith M., Leen-Feldner E.W. The interaction between sleep disturbance and anxiety sensitivity in relation to adolescent anger responses to parent adolescent conflict. Journal of Adolescence. 2020;84:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown W.J., Wilkerson A.K., Boyd S.J., Dewey D., Mesa F., Bunnell B.E. A review of sleep disturbance in children and adolescents with anxiety. Journal of Sleep Research. 2018;27(3) doi: 10.1111/jsr.12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne M.W., Cudeck R. In: Testing structural equation models. Bollen K.A., Long J.S., editors. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. Alternative ways of assessing model fit; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S.K., Wong C.W., Tsang J., Wong K.C. Psychological distress and negative appraisals in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Psychological Medicine. 2004;34(7):1187–1195. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung T., Yip P.S. Depression, anxiety and symptoms of stress among Hong Kong nurses: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015;12:11072–11100. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120911072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chueh K.H., Chen K.R., Lin Y.H. Psychological distress and sleep disturbance among female nurses: Anxiety or depression? Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2019 doi: 10.1177/1043659619881491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho C.M., Suttiwan P., Arato N., Zsido A.N. On the nature of fear and anxiety triggered by COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:581314. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.581314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman D.L., Gilligan T.D. Social support, stress, and self-efficacy: Effects on students’ satisfaction. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice. 2002;4(1):53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Williamson G. In: Social psychology of health. Spacapan S., Oskamp S., editors. SAGE; Newbury Park, CA: 1988. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States; pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Daly M., Robinson E. Psychological distress and adaption to the covid-19 crisis in the United States. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2020;27:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Fuente-Tomás L., Sierra P., Sanchez-Autet M., García-Blanco A., Safont G., Arranz B., García-Portilla M.P. Sleep disturbances, functioning, and quality of life in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2018;269:501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deniz M.E. Self-compassion, intolerance of uncertainty, fear of COVID-19, and well-being: A serial mediation investigation. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;177:110824. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Emmons R.A., Larsen R.J., Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H., Zhang Q., Sun Z., Sang F., Xu Y. Sleep disturbances among Chinese clinical nurses in general hospitals and its influencing factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:241. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1402-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doornik J.A., Hansen H. An omnibus test for univariate and multivariate normality. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 2008;70:927–939. [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne A.-P., Dion J., Lalande D., Bégin C., Émond C., Lalande G., McDuff P. Body dissatisfaction and psychological distress in adolescents: Is self-esteem a mediator? Journal of Health Psychology. 2017;22(12):1563–1569. doi: 10.1177/1359105316631196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duraku Z.H., Kelmendi K., Jemini-Gashi L. Associations of psychological distress, sleep, and self-esteem among Kosovar adolescent. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2020;23(4):511–519. (Doi:0.1080/02673843.2018.1450272) [Google Scholar]

- Durankuş F., Aksu E. Effects of the covid-19 pandemic on anxiety and depressive symptoms in pregnant women: A preliminary study. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1763946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernsten L., Havnen A. Mental health and sleep disturbances in physically active adults during the COVID-19 lockdown in Norway: Does change in physical activity level matter? Sleep Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertz M., Karakas F., Sarigöllü E. Exploring pro-environmental behaviors of consumers: An analysis of contextual factors, attitude, and behaviors. Journal of Business Research. 2016;69:3971–3980. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L.S., Dong Z.J., Yan R.Y., Wu X.Q., Zhang L., Ma J., Zeng Y. Psychological distress in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic: Preliminary development of an assessment scale. Psychiatry Research. 2020;291:113202. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C., Larcker D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(1):39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Full K.M., Malhotra A., Crist K., Moran K., Kerr J. Assessing psychometric properties of the PROMIS Sleep Disturbance Scale in older adults in independent-living and continuing care retirement communities. Sleep Health. 2019;5(1):18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawrych M., Cichoń E., Kiejna A. Covid-19 pandemic fear, life satisfaction and mental health at the initial stage of the pandemic in the largest cities in Poland. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2021;26(1):107–113. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1861314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori A., Topino E., Fabio A.D. The protective role of life satisfaction, coping strategies and defense mechanisms on perceived stress due to COVID-19 emergency: A chained mediation model. PLoS One. 2020;15(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin S., Tan J., Perrin P.B., Williams A.B., Smith E.R., Rybarczyk B. Psychosocial underpinnings of pain and sleep disturbance in safety-net primary care patients. Pain Research & Management. 2020;2020:5932018. doi: 10.1155/2020/5932018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Jr., Black W.C., Babin B.J., Anderson R.E. 7th ed. Pearson Education International, Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: 2010. Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Hamouche S. COVID-19 and employees’ mental health: Stressors, moderators and agenda for organizational actions. Emerald Open Research. 2020;2(15):1–15. doi: 10.35241/emeraldopenres.13550.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Jang J., Cho E., Choi K.C. Investigating how individual differences influence responses to the covid-19 crisis: The role of maladaptive and five-factor personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;176:110786. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan N., Bao Y. Impact of “e-learning crack up” perception on psychological distress among college students during Covid-19 pandemic: A mediating role of ‘fear of academic year loss’. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020;118:105355. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C. Sample size in four areas of psychological research. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 1983;86(2/3):76–80. doi: 10.2307/3627914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P.M. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research. 2020;288:112954. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D.L. Revisiting sample size and number of parameter estimates: Some support for the N:q hypothesis. Structural Equation Modelling. 2003;10(1):128–141. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Zhu P., Wang L., Hu Y., Pang M., Ma S., Tang X. Psychological distress and sleep quality of COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, a lockdown city as the epicenter of COVID-19. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jӧreskog K.G., Moustaki I. Factor analysis of ordinal variables: A comparison of three approaches. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001;36(3):347–387. doi: 10.1207/S15327906347-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalat J.W., Shiota M.N. Thomson Wadsworth; Belmont: 2007. Emotion. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyani M.N., Jamshidi N., Salami J., Pourjam E. Investigation of the relationship between psychological variables and sleep quality in students of medical sciences. Depression Research and Treatment. 2017;2017:7143547. doi: 10.1155/2017/7143547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Barker P.R., Colpe L.J., Epstein J.F., Gfroerer J.C., Hiripi E.…Zaslavsky A.M. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C., Ko H. The impact of self-compassion on mental health, sleep, quality of life and life satisfaction among older adults. Geriatric Nursing. 2018;39:623–628. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam K.K.L., Zhou M. A serial mediation model testing growth mindset, life satisfaction, and perceived distress as predictors of perseverance of effort. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;167:110262. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.A. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Studies. 2020;44(7):393–401. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1748481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.A., Crunk E.A. Fear and psychopathology during the covid-10 crisis: Neuroticism, hypochondriasis, reassurance-seeking, and coronaphobia as fear factors. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. 2020;0(0):1–14. doi: 10.1177/0030222820949350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.C., Asher J.M., Goldlust S., Kraemer J.D., Lawson A.B., Bansal S. Mind the scales: Harnessing spatial big data for infectious disease surveillance and inference. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;214(suppl_4):S409–S413. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.A., Mathis A.A., Jobe M.C., Pappalardo E.A. Clinically significant fear and anxiety of Covid-19: A psychometric examination of the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale. Psychiatry Research. 2020;290:112112. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkovich I., Shinan-Altman S. Impact of the covid-19 pandemic on stress and emotional reactions in Israel: A mixed-methods study. International Health. 2020;0:1–19. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihaa081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A., Wang S., Cai M., Sun R., Liu X. Self-compassion and life-satisfaction among Chinese self-quarantined residents during COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated mediation model of positive coping and gender. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;170:110457. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwic-Kaminska K., Kotyśk M. Comparison of good and poor sleepers: Stress and life satisfaction of university athletes. Revista de Psicología del Deporte. 2017;26(4):121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lund H.G., Reider B.D., Whiting A.B., Prichard J.R. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(2):124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., Jiang W., Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. 2020;291 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnavita N., Garbarino S. Sleep, health and wellness at work: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017;14:1347. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maria-loanna A., Patra V. The role of psychological distress as a potential route through which procrastination may confer risk for reduced life satisfaction. Current Psychology. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00739-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marum G., Clench-Aas J., Nes R.B., Raanaas R.K. The relationship between negative life events, psychological distress and life satisfaction: A population-based study. Quality of Life Research: an International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation. 2014;23(2):601–611. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0512-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleary-Gaddy A.T., James D. Skin tone, life satisfaction, and psychological distress among African Americans: The mediating effect of stigma consciousness. Journal of Health Psychology. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1177/13591053209542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller S., Rau H. Economic preferences and compliance in the social stress test of the covid-19 crisis. Journal of Public Economics. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T.H.D., Vu D.C. Impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic upon mental health: Perspective from Vietnam. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(5):480–481. doi: 10.1037/tra0000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J.C., Bernstein I.H. The assessment of reliability. Psychometric Theory. 1994;3:248–292. [Google Scholar]

- Odriozola-González P., Planchuelo-Gómez Á., Irurtia M.J., de Luis-García R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Research. 2020;290:113108. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohman A. In: Handbook of emotions. 2nd ed. Lewis M., Haviland-Jones J.M., editors. Guilford; 2000. Fear and anxiety: Evolutionary, cognitive, and clinical perspectives; pp. 573–593. [Google Scholar]

- Patel S.R., Blackwell T., Redline S., Ancoli-Israel S., Cauley J.A., Hillier T.A.…Stone K.L. The association between sleep duration and obesity in older adults. International Journal of Obesity. 2008;32:1825–1834. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza P.d., Guzi M., Tijdens K. Publications Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2020. Life dissatisfaction and anxiety in COVID-19 pandemic. EUR 30243 EN. (JRC120822) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peláez-Fernández M., Rey L., Extremera N. Psychological distress among the unemployed: Do core self-evaluations and emotional intelligence help to minimize the psychological costs of unemployment? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2019;256:627–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez E., Perrin P.B., Lageman S.K., Villaseñor T., Dzierzewski J.M. Sleep, caregiver burden, and life satisfaction in Parkinson’s disease caregivers: A multinational investigation. Disability and rehabilitation. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1814878. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K.J., Hayes A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behaviour Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quach H.L., Hoang N.A. Covid-19 in Vietnam: A lesson of pre-preparation. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2020;127:104379. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogowska A., Kuśnierz C., Bokszczanin A. Examining anxiety, life satisfaction, general health, stress and coping styles during COVID-19 pandemic in Polish sample of university students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 2020;13:797–811. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S266511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel S.R., Kuduruthullah S., Khair A., Al Shayeb M., Elkaseh A., Varma S.R., Nadeem G., Elkhader I.A., Ashekhi A. Impact of pain, psychological-distress, SARS-CoV2 fear on adults' OHRQOL during COVID-19 pandemic. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2021;28(1):492–494. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saravanan C., Mahmoud I., Elshami W., Taha M.H. Knowledge, anxiety, fear, and psychological distress about COVID-19 among university students in the United Arab Emirates. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11:582189. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.582189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saricali M., Satici S.A., Satici B., Gocet-Tekin E., Griffiths M.D. Fear of covid-19, mindfulness, humor, and hopelessness: A multiple mediation analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00419-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satici B., Gocet-Tekin E., Deniz M.E., Satici S.A. Adaptation of the fear of COVID-19 scale: Its association with psychological distress and life satisfaction in Turkey. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00294-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghrir M.H., Borazjani R., Shiraly R. COVID-19 and Iranian medical students; a survey on their related-knowledge, preventive behaviors and risk perception. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2020;23(4):249–254. doi: 10.34172/aim.2020.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Boros S. Effects of a pedometer-based walking intervention on young adults’ sleep quality, stress and life satisfaction: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies. 2020;24:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Zhang Y., Ding W., Meng Y., Hu H., Liu Z.…Wang M. Psychological distress and sleep problems when people are under interpersonal isolation during an epidemic: A nationwide multicenter cross-sectional study. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists. 2020;63(1) doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2020. https://covid19.who.int/ Retrieved November 25, 2020, from.

- Ye B., Wu D., Im H., Liu M., Wang X., Yang Q. Stressors of covid-19 and stress consequences: The mediating role of rumination and the moderating role of psychological support. Children and Youth Service Review. 2020;118:105466. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Ye M., Fu Y., Yang M., Luo F., Yuan J., Tao Q. The psychological impact of the covid-19 pandemic on teenagers in China. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67:747–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.X., Wang Y., Rauch A., Wei F. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Research. 2020;288:112958. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi T., Sung X., Li S., Wang Q., Cai L., Li L., Li Y., Xu M., Wang Y., Chu X., Wang Z., Jiang X. Associations of sleep duration and sleep quality with life satisfaction in elderly Chinese: The mediating role of depression. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2016;65:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

. This is open data under the CC BY license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.