Abstract

The use of topical negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has become increasingly popular in the management of complex wounds. There are many theories as to the mechanism of action of NPWT, but the essential components of the various systems remain consistent. There are many attractive potential properties of negative pressure dressings that lend themselves to the management of upper limb injuries. This article explores the technique of negative pressure wound dressing, the theories pertaining to mechanism of action, and the increasingly broad indications described for the use of NPWT in the hand. The literature pertaining to the efficacy of NPWT in general is also discussed.

Keywords: hand, wound, dressing, vacuum, injury, negative pressure

Introduction

The use of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), also known as topical negative pressure (TNP) dressing, has become increasingly widespread since Argenta and Morykwas published their pioneering series in 1997. 1 2 They were the first group to report the use of this technique in North America; however, reports in the Russian literature date back to 1986. 3 Novel applications and benefits continue to be defined and increasingly broad anatomic indications are described.

The components of a negative pressure wound dressing include a porous foam or gauze. There are two widely used foam materials. The black polyurethane foam with pore size ranging from 400 to 600 μm and the white polyvinyl alcohol with pore sizes from 60 to 270 μm. A semiocclusive dressing is applied to create a seal. A vacuum pump is connected to the dressing by suction tubing. Modern dressing systems may have tubing to allow fluid infiltration of the dressing for saline or antibiotic irrigation.

Mechanism of Action of Negative Pressure Wound Dressing

Despite its widespread application, no unifying theory for the mechanism of action of TNP has been agreed. 4 Mouës et al, following a systematic review of over 400 articles in human, animal, and in vitro studies, felt that the mechanisms of action, which could be attributed to negative pressure wound dressings, included increase in blood flow, angiogenesis, reduction in wound size, modulation of inhibitory contents of wound fluid, and induction of cell proliferation. 3 At a molecular level research by Bellot et al has demonstrated a link between NPWT and regulation of antioxidant mechanisms, notably manganese superoxide dismutase, a mitochondrial antioxidant that is a potent wound healing enhancer. 5 Further proposed molecular mechanisms of action include upregulation of interleukin 8 and vascular endothelial growth factor 6 and reduction in matrix metalloproteinase. 7 Much of the mechanical theory was based on Ilizarov's work. He described microdeformation secondary to tension. Integrins on the cell membrane respond to this tension leading to deformation in the intracellular cytoskeleton. This in turn causes upregulation of secondary messengers that increase gene and protein expression and consequently granulation tissue formation. 8 9

General Indications

Indications for the use of negative pressure wound dressings include traumatic or surgical wounds that cannot be primarily closed. This can include wounds with soft tissue loss, exposed tendon, bone, joint and/or hardware. Skin grafts, chronic nonhealing wounds, and closed wounds at risk of breakdown are also indicated. 10 11 12 Contraindications include exposed vascular structures including anastomosed vessels, nerve, organs, and necrotic tissue. 12

Efficacy

Since 2007 there has been an explosion in both the use of, and the number of publications describing, the use of negative pressure wound dressings. Despite the increasing popularity, the evidence to support their use has been questioned. The Cochrane reviews into the use of negative pressure dressings in both traumatic and surgical wounds were unable to find reliable evidence to support the superiority of TNP over traditional dressings. 13 14

The majority of published work on negative pressure wound dressing is in the lower limb; however, there is a growing enthusiasm for expanding its applications into other anatomical regions.

Search Methods

This article sets out to review and summarize the published literature pertaining to the use of negative pressure wound dressings in the hand.

Search Strategy

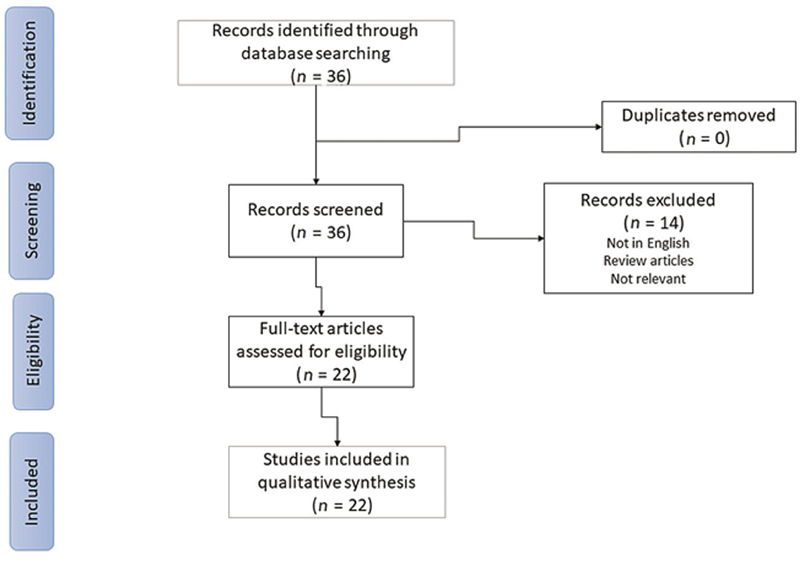

A literature review of the PubMed, Medline, and Embase databases was performed to identify papers on the use of NPWT in the hand. The search was performed with an intention to report the results according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) if suitable comparative studies had been identified. The search terms “negative pressure wound dressing, vacuum assisted closure, hand and hand injury” were used. Inclusion criteria covered articles published in the English language. There was no limit with regard to publication date. The bibliographies and reference lists were reviewed to identify any further relevant articles. The search returned 36 papers the abstracts of which were reviewed by the first author (JL) as part of this study. Papers were excluded if not published in English, if review articles or if not describing outcomes of a new application or technique for the use of NPWT in the hand. Full text articles of the remaining 22 articles were reviewed, again by the first author (JL). Summaries of the study findings were included in the final manuscript if they demonstrated an indication for, or a technique for applying NPWT in the hand. Due to the nature of the included articles, case reports, small case series, and technique descriptions, synthesis of the results according to the PRISMA statements was not possible. We, therefore, present a narrative review of the published literature describing the application of topical NPWT in the hand. The search process is summarized in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for the search strategy.

Results

Techniques for Applying Negative Pressure Wound Dressings in the Hand

Maintenance of an air tight seal is essential for the function of negative pressure wound dressing. Due to the irregular contours of the hand and the web spaces, this can be extremely challenging, particularly if trying to produce a sufficiently streamlined dressing to allow early range of movement. This has led to the development of several novel techniques.

Ng et al were the first to describe the hand-in-glove technique. They suggested using a sterile co-polymer glove (Copolymer Sterile Exam Glove, Yaan Device Co. Ltd., Jan Hua Hsien, Taiwan) secured at the wrist with the usual adhesive polyurethane drape, to encase the foam dressing and the suction tubing. They applied an adhesive dressing (Tegaderm 3M Health Care, St Paul, Minnesota, United States) to the wound edges to prevent maceration and wound enlargement from direct contact with the foam. 15 They stress the importance of trimming the patient's nails before applying the negative pressure if one wishes to avoid glove penetration and loss of seal ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

The hand-in-glove technique (Reprinted with permission from Elsevier Ltd). 15

Several authors have modified this technique. In 2009, Foo et al incorporated a second copolymer glove and used the adhesive vacuum-assisted closure (VAC; Kinetic Concepts Inc, San Antonio, Texas, United States) drape to create a mesentery and prevent tension on the suction tubing. They describe the use of this dressing to treat multiple volar digit injuries with good effect, terming it the “hand-in-gloves” technique Fig. 3 . 16

Fig. 3.

The hand-in-glove technique (Reprinted with permission from Elsevier Ltd). 16

Sommier et al expressed concern at encasing the uninjured fingertips in the dressing. They felt that there was an unnecessary risk of maceration and that the ability to assess the color and vascularity of the digits would be compromised. They therefore recommend the “hand in mitt” technique where the fingers of the sterile glove are removed. They do not report which glove they used but found no loss of suction with the fingers removed. 17

Fujitani et al describe two cases using sterile latex surgical gloves as part of a negative pressure dressing in the hand. In contrast to the previously described techniques, they applied the glove first with a hole cut out over the wound. The adhesive polyurethane dressing was applied over this and the suction tubing attached. Both wounds were definitively covered with skin grafts following the negative pressure therapy and the patients made a good recovery Fig. 4 . 18

Fig. 4.

Modified hand in mitt technique (Reprinted with permission from the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan). 18

The hand-in-glove technique can be applied to cases with external skeletal fixation as demonstrated by Gerszberg and Tan in two published cases. They were able to maintain a seal using the hand-in-glove technique despite external skeletal fixation being in situ. The external fixator was applied as dictated by the bony injury. The foam was cut to the size of the wound with relieving cuts around the pins. A large sterile surgical glove with the fingers removed was applied over the entire construct with care being taken to pad any sharp prominences. The sponge component of surgical scrubbing brushes was utilized. The proximal end of the glove was secured with the adhesive film dressing from the negative pressure dressing set (V.A.C. ATS Therapy System, KCI, KK, Japan). In a series of two cases, a good seal was achieved in both patients and definitive coverage was performed with skin grafting Fig. 5 . 19

Fig. 5.

Hand-in-glove technique with external skeletal fixation in situ (Reprinted with permission from SLACK inc). 19

An alternative technique for creating an adequate seal, yet allowing the early mobilization so essential in hand surgery, is described by Hasegawa et al. They applied a Hydrosite sponge secured with Opsite film dressing (Smith and Nephew, Tokyo, Japan) before inserting the dressed hand into a commercially available gas sterilized sealing bag (Ziploc, Asahi, Kasei, Osaka, Japan), which is then secured with dressing tape. The vacuum was stopped and if necessary a small amount of air instilled to the bag with a syringe to allow active range of movement exercises. Following the exercises negative pressure could be reapplied Fig. 6 . 20

Fig. 6.

Bag type negative pressure wound therapy (Reprinted with permission from Okayama University, Japan). 20

Managing Specific Wounds in the Hand

Burns

Ehrl et al reported the results of a case series of 80 burnt hands in 51 patients. All were treated with a polyurethane-based negative pressure dressing. The hand was encased in a mitten made of the polyurethane foam secured with skin staples. The foam was covered with the adhesive film and negative pressure of–75 mm Hg applied with the hand in the position of safe immobilization Fig. 7 .

Fig. 7.

Negative pressure wound dressing used to treat burnt hands (Reprinted with permission from the American Burn Association). 21

All patients with third-degree burns were able to be treated with split skin grafting. They were able to review 47 hands in 30 patients at a mean of 35 months post burn. About 85.1% of hands had full active extension with 78.7% able to make a full fist. Mean disability of the arm shoulder and hand (DASH) was 13.8. With regard to scarring 41 cases were deemed good with no evidence of hypertrophy and six were deemed acceptable. None were felt to be unacceptable. 21

In a four-armed multicenter trial from the Netherlands, 86 patients with deep dermal or full thickness burns requiring skin transplantation were randomized in to four arms. The groups were split skin graft with or without negative pressure dressing and split skin graft with dermal substitute, again with or without TNP. Key findings were that graft take was comparable throughout, demonstrating that single-stage grafting with a dermal substitute was feasible. This was in contrast to previous reports of dermal substitute single-stage grafting having a poor rate of graft take. Contamination rates were significantly lower in the TNP groups and skin elasticity was highest in the TNP and dermal substitute group. 22 In a follow-up study, it was shown that the added intervention of dermal substitute and TNP contributed, at most, 7% to the overall cost of caring for these patients. They felt that when the overall variability of the treatment expenditure was taken into account “the cost considerations of the interventions in this study should not play an important role.” 23

Negative pressure wound dressing may also play a role as a temporizing measure in the management of the burnt hand. Wang et al describe nine cases using TNP dressing following debridement of deep dermal burn and prior to reconstruction with a super thin glove like abdominal flap. They report partial flap necrosis in just one case. All aesthetic outcomes were reported as satisfactory and either no pain or minor discomfort only was reported from the donor site. 24

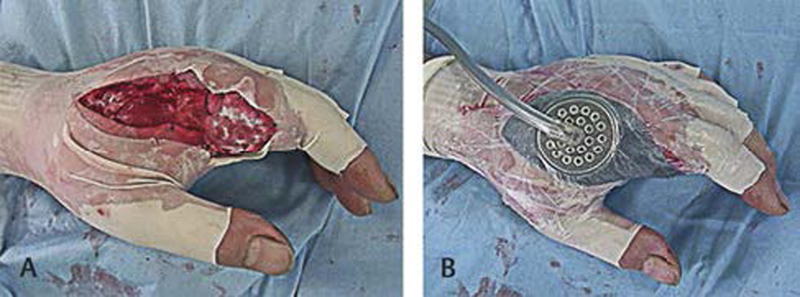

As well as thermal injury negative pressure wound dressing has been used to treat cryoinjuries. Kua et al describe a case of bilateral hand injuries secondary to Freon exposure. Freon is an industrial refrigerant that causes severe tissue trauma. A 36-year-old patient was treated with severe cold injury secondary to Freon exposure and a consequential acute compartment syndrome. He underwent surgical decompression then NPWT and hyperbaric oxygen. The result was excellent with no tissue loss nor intrinsic atrophy. They suggest that the negative pressure and hyperbaric oxygen had a synergistic protective effect on the injured tissue Fig. 8 . 25

Fig. 8.

Hand exposed to Freon gas post-surgical decompression and with NPWT in position (Reprinted with permission from Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg). 25

Fight Bite

Two papers report the use of negative pressure dressings in fight bite injuries. Kilian reports a case of a 30-year-old man with magnetic resonance imaging confirmed metacarpal head osteomyelitis treated with repeated debridement NPWT and intravenous antibiotics. The infection resolved and they were able to primarily close the wound. 26

Fujitani et al reported on a similar case of metacarpal head osteomyelitis secondary to a fight bite. Following multiple debridements intravenous antibiotics and TNP dressing, the infection resolved and the wound was covered with a local flap and skin grafting. 18

Degloving

Negative pressure wound dressing has been utilized in the management of major degloving injuries of the hand. DeFranzo et al report a case of roller degloving of the hand. The dorsum of the hand and all fingers to the distal palmar crease were affected. The little ring and middle finger were nonviable and amputated through the middle phalanx. Full-thickness defatted skin grafts were held in place with vacuum assisted dressings and 95% graft take was achieved. They employed a similar technique in a degloving injury of the foot to good effect. 27

Surgically Created Wounds

Chipp et al describe three cases where they have utilized negative pressure wound dressing in the management of elective surgical wounds. They use a gauze-based TNP with a large iodine impregnated adhesive film (Ioban 3M, Bracknell, United Kingdom) applied in two halves to “sandwich” the hand. Continuous suction at 80 mm Hg is applied using the Renasys NPWT system (Smith and Nephew, Hull, United Kingdom).

They have employed this technique to protect tenuous dorsal skin following revision excision of a venous malformation in the left hand of a 35-year-old female. The wound was primarily closed but there was concern for the vascularity of the thin skin flaps due to scarring from previous surgery. The negative pressure dressing was applied as described above for 1 week until the initial wound check.

The same team reports the use of vacuum-assisted closure in a case of dermofasciectomy and skin graft for recurrent severe Dupuytren's contracture. The dressing was applied in the described technique and the hand splinted in the position of safety. There was a small amount of graft loss in the palm, but rapid adherence of the graft and minimal postoperative swelling was noted.

The same technique was employed to both stabilize the graft and splint the thumb in a 60-year-old lady following first web space release. 28

Distant Flaps

There are two reports in the literature of negative pressure dressings being employed as adjuncts in the management of abdominal flaps for coverage of upper limb defects.

Chipp et al describe a case of a 42-year-old multiply injured blast victim. A pedicled abdominal flap was used to resurface the palmar aspect of his hand, but in the initial postoperative period he found the traditional bulky dressing quite cumbersome and a small amount of the flap became detached. He returned to theater for reattachment of the flap and gauze-based TNP was applied to splint the arm and facilitate nursing care. The flap was successfully divided at 3 weeks as planned. 28

Weinand similarly utilized a negative pressure dressing to stabilize a superficial inferior epigastric pedicled abdominal flap for the treatment of a burnt hand. They noted hastened attachment of the flap at just 4 days postoperatively. 29

Use of TNP in Previously Contraindicated Situations

Post Replant

It has been suggested that negative pressure wound dressings should be used with caution in tissues with compromised perfusion. 30 Concern had been raised that the circumferential application of negative pressure wound dressing in the hand and digit could further impact upon the already precarious blood flow in the replanted extremity. In an in vitro study, Matsushita et al were able to demonstrate preserved skin perfusion pressures and minimal direct pressure effect to the skin from a circumferential negative pressure dressing even with suction applied of up to 200 mm Hg well above that used in clinical practice. 31

In a series of 11 replanted limbs where negative pressure dressings were used for the management of partial necrosis or soft tissue defects, Dadaci et al report very satisfactory outcomes. Following debridement, they applied TNP at 75 mm Hg intermittent (5 minutes suction and 2 minutes resting at 35 mmHg). The dressing was changed at 3 days. After 6 days, the dressing was removed, a skin graft was applied, and the TNP was reapplied for a further 4 days. They report almost complete graft survival and maintained partial oxygen saturations of between 96 and 99% throughout the period of negative pressure application. 32

In Zhou et al's cohort study of 43 patients with complex wounds requiring reconstruction in patients with replanted extremities, they were able to demonstrate a reduction in the number of flaps needed for definitive wound coverage. This was due to increased granulation tissue allowing skin grafting to be employed in preference. They reported no negative effect on the survival rate of the replanted limb. 33

More recently, the use of NPWT has been used in the treatment of venous congestion following fingertip replant. A team from Bogota in Colombia reports two cases of distal digital replants that showed significant venous congestion postoperatively. Both were treated with negative pressure dressing at intermittent pressure of 75 mm Hg. Both digits survived. 34

Pediatrics

Hutchison and Craw demonstrated the safety and efficacy of using dermal substitute with out-patient negative pressure wound dressing in a pediatric patient. There was a single case involving the upper limb within a case series of eight patients. The wound was secondary to an extravasation injury and compartment syndrome leaving a complex defect with exposed extensor tendons. They recommend reducing the suction pressure to 75 to 100 mm Hg in children below 12 and 50 to 75 mm Hg in infants. They conclude that the use of dermal substitute and secondary skin grafting with negative pressure wound dressing is safe and efficacious in children negating the need for flap reconstruction in many cases. 35

Uses Other than Wound Management

Splinting

Kairinos et al were the first to describe the technique for creating a hand splint utilizing a negative pressure wound dressing. They employed two foam slabs with strips of foam between the fingers. The foam slabs are secured together with skin staples taking care to secure the dorsal and volar slabs in such a way as to create a position of safe immobilization once the negative pressure is applied Fig. 9 . 36

Fig. 9.

The “Vac splint” for hands (Reprinted with permission from Elsevier Ltd). 36

Taylor et al described their experience using a gauze-based TNP system (Kerlix AMD Tyco Healthcare Gosport, United Kingdom) as a splint and wound dressing in a cohort of severely injured military personnel. They employed intermittent pressure of–80 mm Hg. They conclude that negative pressure wound dressings in the multiply injured patient are quick and easy to apply as well as being conducive to wound healing and providing simple and effective immobilization. 37

Scleroderma

Patel and Nagle describe a single case of a patient with chronically infected and ulcerated hand secondary to scleroderma being managed with negative pressure wound dressing without surgery. Amputation had initially been suggested for the 61-year-old patient; however, following medical optimization with tadalafil and 4 months of subatmospheric pressure treatment using a VAC dressing (KCI, San Antonio, Texas, United States) his wounds healed with no evidence of infection and no need for amputation. 38

Evidence

The indication and applications of negative pressure wound dressings continue to grow exponentially; however, robust scientific evidence to demonstrate their efficacy or superiority in the hand is lacking.

A randomized control trial (RCT) has been performed by Shim et al, on NPWT in acute multitissue injuries of the hand. After reconstructive surgery, patients were randomized to conventional wound dressing or TNP, both of which were changed every 3 days. The conventional dressing consisted of “polyurethane foam with a compressible elastic bandage and a short arm splint in a functional position.” The TNP used was CuraVAC (CGBio Korea). The age and hand injury severity score of the two cohorts were comparable. A total of 51 patients were recruited over 3 years. The DASH score was recorded 1 month post removal of sutures and at 1 year post injury. Scores were significantly lower in the TNP group at both time points. Furthermore, the time required to recover 90% of contralateral range of movement was reduced from 46.9 to 33.3 days in the TNP group. 39

Karlakki et al have also highlighted the potential benefits of TNP in general use with respect to hip and knee arthroplasty patients. This was a nonblinded single-center RCT recruiting 220 arthroplasty patients to either TPM (PICO, Smith & Nephew) or a control dressing (Mepore or Tegaderm). There was an overall improvement in wound exudate, with a fourfold reduction in grade 4 measurements in the PICO cohort. Additional reductions in dressing changes, length of stay, and superficial surgical site infections (SSI) were noted in the study group. Wound blistering was seen in 11% of the NPWT cohort versus 1% in the control group. This was felt to be partially user-related as a higher prevalence was noted where the trainee had applied the dressing. 40

Further positive results have been highlighted by a meta-analysis of 16 studies (10 RCTs; 6 observational) into the preventative use of TVN dressings (PICO, Smith & Nephew) in surgical wounds from all surgical specialties. 41 A total of 1,863 patients (2202 wounds) were represented and indicated a statistically significant reduction in length of stay, SSI, and wound dehiscence when compared with standard postoperative dressings.

A Cochrane review has recently been performed into the use of negative pressure dressings in both traumatic and surgical wounds and included many of the papers in the Strugala and Martin meta-analysis. 42 The Cochrane review also found a reduction in SSI in the negative pressure dressing group. However, the review additionally highlighted the limitations of the current literature base in TNP, stating that the finding was of “low certainty” due to a very serious risk of bias of the included studies.

Conclusion

The uses and indications of negative pressure wound dressing in the hand are expanding rapidly with very promising reports of short-term results in limited case reports and series. The use of TNP as a preventative measure in surgical incisions is additionally gaining momentum, although it remains to be seen as to how this can be applied to the use in the hand. A suitable TNP dressing may enable earlier engagement with hand therapy, but further investigation into the use of PICO in the hand would be appropriate. Benefits such as a reduced length of stay are less relevant with day case elective procedures, although a suitable TNP may result in lower rates of wound dehiscence. NPWT seems to be safe and effective in the management of complex wounds and multitissue injuries. At present, however, experimental data to demonstrate superiority of negative pressure dressings over conventional dressings are lacking. This paucity of comparative studies limits the extent of our review to a narrative report of the currently described applications of negative pressure wound therapy in the hand. The efficacy of this technology remains to be demonstrated.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Argenta L C, Morykwas M J. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38(06):563–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morykwas M J, Argenta L C, Shelton-Brown E I, McGuirt W. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38(06):553–562. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199706000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mouës C M, Heule F, Hovius S ER. A review of topical negative pressure therapy in wound healing: sufficient evidence? Am J Surg. 2011;201(04):544–556. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watt A J, Friedrich J B, Huang J I. Advances in treating skin defects of the hand: skin substitutes and negative-pressure wound therapy. Hand Clin. 2012;28(04):519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellot G L, Dong X, Lahiri A. MnSOD is implicated in accelerated wound healing upon Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT): a case in point for MnSOD mimetics as adjuvants for wound management. Redox Biol Elsevier B. 2018;V:1–42. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labler L, Rancan M, Mica L, Härter L, Mihic-Probst D, Keel M. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy increases local interleukin-8 and vascular endothelial growth factor levels in traumatic wounds. J Trauma. 2009;66(03):749–757. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318171971a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennis P, Orgill P, Lee R C. Clinical Review: The mechanisms of action of vacuum assisted closure: more to learn. Surgery. Mosby. Inc. 2009;146(01):40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilizarov G A. The tension-stress effect on the genesis and growth of tissues. Part I. The influence of stability of fixation and soft-tissue preservation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(238):249–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ilizarov G A. The tension-stress effect on the genesis and growth of tissues: Part II. The influence of the rate and frequency of distraction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(239):263–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webb L X. New techniques in wound management: vacuum-assisted wound closure. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10(05):303–311. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stannard J P, Volgas D A, Stewart R. McGwin G Jr, Alonso JE. Negative pressure wound therapy after severe open fractures: a prospective randomized study. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23(08):552–557. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181a2e2b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Streubel P N, Stinner D J, Obremskey W T. Use of negative-pressure wound therapy in orthopaedic trauma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(09):564–574. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-09-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Newton K, Dumville J C, Costa M L, Norman G, Bruce J. Negative pressure wound therapy for open traumatic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7:CD012522. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012522.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumville J C, Owens G L, Crosbie E J, Peinemann F, Liu Z. Negative pressure wound therapy for treating surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(06):CD011278. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011278.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng R, Sebastin S J, Tihonovs A, Peng Y P. Hand in glove–VAC dressing with active mobilisation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59(09):1011–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foo A, Shenthilkumar N, Chong AK-S. The “hand-in-gloves” technique: vacuum-assisted closure dressing for multiple finger wounds. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. British Association of Plastic. Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(05):e129–e130. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommier B, Sawaya E, Pelissier P. The hand in the mitt: a technical tip for applying negative pressure in hand wounds. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2014;39(08):896. doi: 10.1177/1753193413480315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujitani T, Zenke Y, Shinone M, Menuki K, Fukumoto K, Sakai A. Negative pressure wound therapy with surgical gloves to repair soft tissue defects in hands. J UOEH. 2015;37(03):185–190. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.37.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerszberg K S, Tan V. Vacuum-assisted closure with external fixation of the hand. Orthopedics. 2011;32(11):829–831. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20090922-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasegawa K, Namba Y, Kimata Y. Negative pressure wound therapy incorporating early exercise therapy in hand surgery: bag-type negative pressure wound therapy. Acta Med Okayama. 2013;67(04):271–276. doi: 10.18926/AMO/51073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehrl D, Heidekrueger P I, Broer P N.Topical negative pressure wound therapy of burned hands J Burn Care Res 2017(Mar)1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bloemen M CT, van der Wal M BA, Verhaegen P DHM. Clinical effectiveness of dermal substitution in burns by topical negative pressure: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20(06):797–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hop M J, Bloemen M CT, van Baar M E. ScienceDirect. Burns. Elsevier Ltd Int Soc Burns Inj. 2014;40(03):388–396. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang F, Liu S, Qiu L. Superthin abdominal wall glove-like flap combined with vacuum-assisted closure therapy for soft tissue reconstruction in severely burned hands or with infection. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;75(06):603–606. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kua E HJ, Tanri N P, Tan B-K. Cryoinjury with compartment syndrome of bilateral hands secondary to Freon gas: a case report and review of current literature. Eur J Plast Surg. 2014;38(01):77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilian M. Clenched fist injury complicated by septic arthritis and osteomyelitis treated with negative pressure wound therapy: one case report. Chin J Traumatol. 2016;19(03):176–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeFranzo A J, Marks M W, Argenta L C, Genecov D G. Vacuum-assisted closure for the treatment of degloving injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(07):2145–2148. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199912000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chipp E, Sheena Y, Titley O G. Extended applications of gauze-based negative pressure wound therapy in hand surgery: a review of five cases. J Wound Care. 2014;23(09):448–450. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2014.23.9.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinand C. The vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device for hastened attachment of a superficial inferior-epigastric flap to third-degree burns on hand and fingers. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30(02):362–365. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318198a77e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kairinos N, Voogd A M, Botha P H. Negative-pressure wound therapy II: negative-pressure wound therapy and increased perfusion. Just an illusion? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(02):601–612. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318196b97b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsushita Y, Fujiwara M, Nagata T, Noda T, Fukamizu H. Negative pressure therapy with irrigation for digits and hands: pressure measurement and clinical application. Hand Surg. 2012;17(01):71–75. doi: 10.1142/S0218810412500116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dadaci M, Isci E T, Ince B. Negative pressure wound therapy in the early period after hand and forearm replantation, is it safe? J Wound Care. 2016;25(06):350–355. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2016.25.6.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou M, Qi B, Yu A. Vacuum assisted closure therapy for treatment of complex wounds in replanted extremities. Microsurgery. 2013;33(08):620–624. doi: 10.1002/micr.22178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez-Sierra M A, Bermudez J C. Use of negative-pressure wound therapy to overcome venous congestion in fingertip reimplantation. 14th Triennial Congress IFSSH 2019. [DOI]

- 35.Hutchison R L, Craw J R. Use of acellular dermal regeneration template combined with NPWT to treat complicated extremity wounds in children. J Wound Care. 2013;22(12):708–712. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2013.22.12.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kairinos N, Hudson D A. The “Vacsplint” for hands. Journal of Plastic Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(04):e425. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor C J, Chester D L, Jeffery S L. Functional splinting of upper limb injuries with gauze-based topical negative pressure wound therapy. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(11):1848–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel R M, Nagle D J. Nonoperative management of scleroderma of the hand with tadalafil and subatmospheric pressure wound therapy: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(04):803–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shim H S, Choi J S, Kim S W. A role for postoperative negative pressure wound therapy in multitissue hand injuries. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018(04):3.629643E6. doi: 10.1155/2018/3629643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karlakki S L, Hamad A K, Whittal C. Incision negative pressure wound therapy dressings (iNPWTd) in routine hip and knee arthroplasties. Bone Joint Res. 2016;5(08):328–337. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.58.BJR-2016-0022.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strugala V, Martin R. Meta- analysis of comparative trials evaluating a prophylactic single-use negative pressure wound therapy system for the prevention of surgical site complications. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2017;18(07):810–819. doi: 10.1089/sur.2017.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webster J, Liu Z, Norman G. Negative pressure wound therapy for surgical wounds healing by primary closure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3:CD009261. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009261.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]