Abstract

We constructed a rough mutant of Brucella abortus 2308 by transposon (Tn5) mutagenesis. Neither whole cells nor extracted lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from this mutant, designated RA1, reacted with a Brucella O-side-chain-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb), Bru-38, indicating the absence of O-side-chain synthesis. Compositional analyses of LPS from strain RA1 showed reduced levels of quinovosamine and mannose relative to the levels in the parental, wild-type strain, 2308. We isolated DNA flanking the Tn5 insertion in strain RA1 by cloning a 25-kb XbaI genomic fragment into pGEM-3Z to create plasmid pJM6. Allelic exchange of genomic DNA in B. abortus 2308 mediated by electroporation of pJM6 produced kanamycin-resistant clones that were not reactive with MAb Bru-38. Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA from these rough clones revealed Tn5 in a 25-kb XbaI genomic fragment. A homology search with the deduced amino acid sequence of the open reading frame disrupted by Tn5 revealed limited homology with various glycosyltransferases. This B. abortus gene has been named wboA. Transformation of strain RA1 with a broad-host-range plasmid bearing the wild-type B. abortus wboA gene resulted in the restoration of O-side-chain synthesis and the smooth phenotype. B. abortus RA1 was attenuated for survival in mice. However, strain RA1 persisted in mice spleens for a longer time than the B. abortus vaccine strain RB51, but as expected, neither strain induced antibodies specific for the O side chain.

Members of genus Brucella are gram-negative coccobacilli and are facultative intracellular pathogens that can cause chronic zoonotic disease. There are six well-recognized Brucella species which show differences in their host specificities and pathogenicities (19, 45). Brucella abortus is the causative agent of cattle brucellosis, but along with Brucella melitensis, Brucella suis, and Brucella canis, it can also cause undulant fever in humans (13). Brucellae proliferate within macrophages of the host animal and thereby successfully avoid the bactericidal effects of phagocytes. Our knowledge about all the mechanisms Brucella employs for its intracellular survival is limited. Recent findings indicate that brucellae replicate in phagosomes by preventing the fusion between phagosomes and lysosomes (32). In addition, several other mechanisms are thought to be operative, among which are the actions of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (including the O side chain [8, 11, 15, 34, 35]), the structure of core LPS (1), and various other Brucella components (6, 7, 10, 11, 14).

Brucella organisms exhibiting a smooth phenotype are generally more virulent than those with a rough phenotype (36), with the exceptions of B. canis and Brucella ovis, which are rough but virulent in their primary host. The smooth phenotype is due to the presence of a complete LPS in the outer cell membrane, which is composed of lipid A, a core oligosaccharide, and an O-side-chain polysaccharide. LPSs of rough Brucella strains do not contain O side chains. Although the fine structure of Brucella LPS has not been elucidated, it has been reported that the lipid A region is composed of 2-amino-2-deoxy-d-glucose, n-tetradecanoic acid, n-hexadecanoic acid, 3-hydroxytetradecanoic acid, and 3-hydroxyhexa-decanoic acid (12). If we assume that most of the mannose found in the LPS is in the O-side-chain subunits, the core appears to be primarily composed of glucose (28). The amounts of glucosamine and 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid (KDO) have not been determined in the core region of B. abortus (28). The O side chain of B. abortus is a linear homopolymer of α-1,2-linked 4,6-dideoxy-4-formamido-α-d-mannopyranosyl subunits usually averaging between 96 and 100 subunits in length (12). In comparison, these lengths appear to be much longer than those of the O side chains of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, which average about 40 subunits per chain (17). However, since the B. abortus O-side-chain subunit is a monosaccharide while those of Salmonella are most often pentasaccharides (47), the molecular weights of the O side chains are probably similar. In B. abortus, smooth LPS has been implicated in counteracting several bactericidal activities of the phagocytes and demonstrated to be essential for intracellular survival (34, 35). Rough strains of B. abortus, such as vaccine strain RB51, exhibit loss of virulence and cannot replicate within macrophages (40). Despite such an important role for the O side chain in Brucella, our knowledge about its biosynthesis is limited. The present study was undertaken to identify the genes encoding the essential proteins or enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of the B. abortus O side chain. This report describes the isolation of a rough strain of B. abortus by Tn5 mutagenesis and the determination of the disrupted gene, named wboA, as encoding a glycosyltransferase. In addition, the LPS composition and virulence of the mutant rough strain are presented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in these experiments are listed in Table 1. E. coli and S. typhimurium strains were grown at 37°C in either Luria-Bertani broth (27), terrific broth (43), or SOB (18). All Brucella strains were grown at 37°C in tryptic soy broth. Bacterial strains containing plasmids were grown in media containing appropriate antibiotics (100 μg of ampicillin per ml or 25 μg of kanamycin or chloramphenicol per ml).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| B. abortus | ||

| 2308 | Wild-type, smooth strain | G. G. Schurig |

| RA1 | Tn5-induced rough mutant of 2308 | This study |

| RB51 | Rifr rough mutant of 2308 | 40 |

| E. coli DH5α | rfbD endA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 F′ | Promega |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-3Z | AmprlacZ′ | Promega |

| pSUP2021 | Ampr, Tn5 (Kanr) | 41 |

| pUC4-K | Ampr Kanr | Pharmacia-Biotech |

| pJM6 | Ampr, 25-kb XbaI chromosomal fragment from strain RA1 ligated into pGEM-3Z | This study |

| pJM63 | 11.6-kb EcoRI insert from pJM6 ligated into pGEM-3Z | This study |

| pRW4424 | 2.1-kb insert from pJM63 ligated into pUC18 | R. Warren |

| pRW4425 | 5.9-kb insert from pJM63 ligated into pUC18 | R. Warren |

Enzymes and reagents.

Restriction endonucleases, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase, T4 DNA ligase, Bluo-Gal (halogenated indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside), and agarose were purchased from Bethesda Research Laboratories (Gaithersburg, Md.). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Corporation (St. Louis, Mo.). Incert and NuSieve low-melting-point agarose were purchased from FMC Bioproducts (Rockland, Maine).

Serological tests.

A colony immunoblot assay was performed as previously described with a rat monoclonal antibody (MAb), Bru-38, specific for the Brucella O-side-chain epitopes (38, 39). Western blotting was performed according to standard procedures (4). Along with the experimental mice serum samples, MAb Bru-38 was used in the Western blot analysis. The B. abortus tube agglutination test was performed according to the established procedure (2).

DNA procedures.

The routine molecular biologic techniques performed in this study were based on the standard procedures outlined elsewhere (4, 26). All plasmids were isolated from the bacteria by an alkaline lysis procedure (22) unless otherwise stated. Electroporation was used to introduce plasmids into Brucella (25). All other plasmids were introduced into E. coli and Salmonella by the CaCl2 procedure (18, 26).

Southern blotting.

The capillary transfer method (42) was used with 20× SSC (3 M NaCl, 0.3 M sodium citrate [pH 7.0]) as the buffer medium to transfer the DNA from the gel to a Nytran membrane (Shleicher and Schuell Inc., Keene, N.H.). The DNA was UV-crosslinked to the membrane with a Stratalinker (Stratagene Cloning Systems, La Jolla, Calif.) and allowed to dry. Nonradioactive probes were prepared and hybridized with a Genius kit and by using the accompanying procedures from Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals (Indianapolis, Ind.).

DNA sequence analysis.

Nucleotide sequence of the DNA flanking the Tn5 insertion was determined with an Applied Biosystems Inc. (ABI) model 373A automated DNA sequencer. Fluorescence-labeled dideoxy nucleotides were incorporated into DNA with Prism thermocycling kits (ABI). Primes for DNA sequencing were prepared with an ABI model 394 automated oligonucleotide synthesizer. Contigs were assembled and aligned with the Sequencer program (GeneCodes, Madison, Wis.). DNA and protein homologies were determined with BLAST (3) programs.

Complementation.

Complementation of the wboA mutation was accomplished by cloning the gene along with flanking DNA into the broad-host-range plasmid pBBR1MCS (24). The DNA fragment that included wboA was cloned by PCR with a primer pair (5′ primer, GGA TGT CGA CCA GCC CTC CAC ATC AAT AGC; 3′ primer, TTG CGG ATC CTT TAC TCG TCC GTC TCT TAC). The underlined nucleotides represent added SalI and BamHI restriction sites, respectively. The first four nucleotides of each primer were added to aid in restriction digestion of the PCR product. PCR mixtures contained 100 ng of B. abortus DNA with Hot Tub polymerase (Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, Ill.) according to the manufacturer’s directions. The reactions were carried out for 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 53°C for 30 s, and polymerization at 72°C for 1 min 30 s. The generated DNA fragment was purified with a Wizard PCR purification kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and digested with SalI and BamHI, followed by ligation with similarly cleaved pBBR1MCS. Several clones containing plasmids with the expected profile were chosen for DNA sequencing to confirm the construct. One of these plasmids with the expected DNA insert was designated pAB3. Electro-competent strain RA1 was prepared by pelleting bacteria grown overnight in YENB (0.75% yeast extract, 0.8% nutrient broth) medium and by resuspending the bacteria in one-half volume of ice-cold 10% glycerol. These cells were pelleted and resuspended in 1/10 volume of ice-cold 10% glycerol. Five microliters of a 100-ng/ml concentration of pAB3 was electroporated in B. abortus RA1 (2.5 kV, 600 Ω, 25 mF). After 2 h of growth in SOC (18), 50 μl of cells was plated on tryptic soy broth agar supplemented with 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml.

LPS purification.

Smooth and rough Brucella and Yersinia enterocolitica O:9 LPSs were purified by a modification of the procedure described by Moreno et al. (28), as described by Inzana et al. (20). Briefly, following extraction with NaCl, the collected cells were extracted with hot, 45% aqueous phenol for 15 min and the phases were separated by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 30 min at 15°C. Crude LPS in the aqueous phase was precipitated by addition of methanol, suspended in distilled water, dialyzed against water, and lyophilized (28). The crude LPS was suspended in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2, and incubated with RNase and DNase overnight at room temperature as described previously (28). Pronase was added, and the incubation continued for 2 h at room temperature. The insoluble material was washed with distilled water until the A260 and A280 were less than 0.05, suspended in distilled water (2.5 mg/ml) containing 2.5 μl of triethylamine per ml, and stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was collected by centrifugation, the supernatant was retained, and the precipitate was extracted with triethylamine two more times. The supernatants were pooled and lyophilized. If necessary, the LPS was extracted again with hot 45% aqueous phenol, and the aqueous phase was precipitated with cold methanol, suspended in distilled water, dialyzed, and lyophilized.

Smooth LPS was extracted from acetone-killed bacteria with hot, 45% aqueous phenol as described previously (5). The phenol phase was filtered through a no. 40 Whatman filter, the LPS was precipitated from the phenol phase with cold methanol reagent, and the precipitate was extracted with distilled water and concentrated (5). The crude LPS was reprecipitated with cold methanol, suspended in distilled water, and lyophilized. The smooth LPS was purified by enzyme digestion and hot phenol extraction as described previously (20), except that the aqueous phase was removed and the phenol phase was filtered as described above. The LPS was precipitated with cold methanol reagent and suspended in distilled water twice and lyophilized. The final methanol supernatant was measured at A260 and A280 to confirm the purity of the LPS.

LPS analysis.

Following separation of extracted LPS in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel with a 15% separating gel containing 4 M urea, LPS heterogeneity was visualized by silver staining (44). Fatty acids and alditol acetate or trimethylsilyl derivatives of the glycoses were determined by gas chromatography (GC) (21) and GC-mass spectrometry at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, The University of Georgia, Athens, Ga. The absence of the O side chain was also assessed by immunoblot analysis with MAb Bru-38, specific for the O side chain (39).

Mouse spleen clearance.

Groups of five BALB/c mice each were inoculated intraperitoneally with 2 × 108 CFU of either strain RA1 or strain RB51. Mice were killed, and their spleens were cultured for the presence of Brucella by previously described methods (40). Sera were obtained by cardiac puncture and used in immunoblotting to analyze B. abortus strains and Y. enterocolytica O:9 LPS as described previously (40).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the putative wboA gene of B. abortus has been submitted to GenBank; the accession number is AF107768.

RESULTS

Screening of B. abortus Tn5 insertion mutants for the rough phenotype.

A previously created Tn5 insertion library of B. abortus (25) was screened by colony immunoblotting with MAb Bru-38. Over 2,200 clones of B. abortus Tn5 mutants that did not react with MAb Bru-38 were initially isolated. The absence of the O side chain was further verified by demonstrating the uptake of crystal violet by the colonies (46) (data not shown). One of these rough Tn5-induced mutants, strain RA1, was chosen for further study.

LPS analysis.

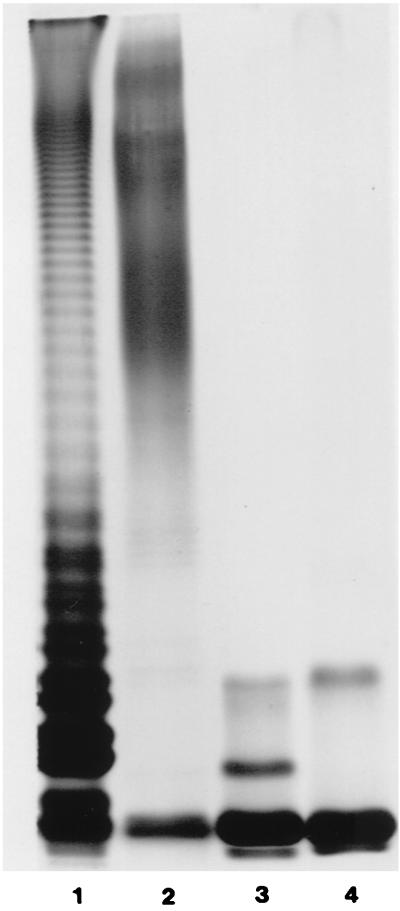

In order to assess the degree of the roughness of strain RA1, the LPS electrophoretic profile was examined (Fig. 1). The silver-stained gel showed no O side chain associated with strain RA1 or vaccine strain RB51 when each strain was compared with B. abortus 2308 (smooth) and S. typhimurium (smooth). A major low-molecular-mass band of the same size (∼4.2 kDa) was present in the LPSs of strains 2308, RB51, and RA1, indicating that strains RA1 and RB51 have a complete core. An additional higher-molecular-mass band was present in strain RA1 and RB51 LPSs, and a band of intermediate size was present in strain RA1 LPS only. Immunoblot analysis with MAb Bru-38 did not reveal any reactivity (data not shown), suggesting that these bands may represent aggregates of core LPS without the O side chain. Compositional analysis indicated that LPSs of strains RB51 and RA1 contained similar amounts of KDO and glucose but that strain RA1 LPS contained substantially more galactose and mannose (Table 2). Whether the differences in these glycoses were responsible for the additional band in strain RA1 LPS could not be determined. N-Acetyl glucosamine was apparently present only in the lipid A moiety because it was not found in lipid-free oligosaccharide. Heptose was also not detected in the LPS (data not shown). The fatty acids identified in Brucella LPS included β-hydroxymyristic acid, palmitic acid, β-hydroxysteric acid, and a large proportion of 27-OH C28, which has not been previously reported. The proportions of these fatty acids were similar in these strains, except there was approximately twice as much palmitic and β-hydroxysteric acids in the LPS of strain 2308 as in the LPS of strain RB51 or RA1.

FIG. 1.

Silver-stained LPS profiles of B. abortus and Salmonella strains. LPSs were extracted and separated by denaturing gel electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, S. typhimurium; lane 2, B. abortus 2308; lane 3, B. abortus RA1; lane 4, B. abortus RB51.

TABLE 2.

Glycose compositions of LPSs from B. abortus RB51, RA1, and 2308

| Strain | Componenta (μg/mg)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Galactose | Mannose | KDO | OVb | |

| RB51 | 32.6 | 0.9 | 4.9 | 114.6 | |

| RA1 | 44.8 | 7.4 | 12.5 | 122.5 | 1.1 |

| 2308 | 22.2 | 2.9 | 22.3 | 56.2 | 31.2 |

Heptose was not identified in the LPS, and amino sugars were not identified in the lipid-free oligosaccharide by colorimetric analysis.

2-Amino-2,6-dideoxy-d-glucose (quinovosamine).

DNA analysis.

In order to identify the mutated gene(s) affecting O-side-chain synthesis, the Tn5 element in strain RA1 was located by physical mapping of the chromosome by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Upon Southern blot analysis, the Tn5 element was located within a 30-kb XbaI fragment (data not shown). Since XbaI does not cut the Tn5 element (23), this restriction enzyme was used to digest the chromosome of B. abortus RA1 and to produce a fragment containing Tn5 and the flanking chromosomal regions. This fragment was ligated into the XbaI site of pGEM3-Z to create pJM6. The actual size of this fragment was estimated to be 25.2 kb. Southern blot hybridization with both the Tn5 element and Brucella chromosomal DNA as probes further confirmed that pJM6 contained both the Tn5 element and the flanking genomic DNA from B. abortus RA1 (data not shown). Further analysis revealed that a 11.6-kb EcoRI fragment from the insert of pJM6 contained the Tn5 element; cloning of this fragment in pGEM-3Z created pJM63 (Table 1).

Nucleotide sequence analysis.

To facilitate sequencing, two EcoRI-PstI fragments from pJM63 were cloned into pUC18 to create pRW4424 and pRW4425. Plasmids pRW4424 and pRW4425 contained a 2.1- and a 5.9-kb insert, respectively; these inserts represented the DNA sequences flanking the Tn5 insertion and 0.7 kb of Tn5 DNA. Nucleotide sequencing of these inserts was performed to obtain the DNA sequence flanking the Tn5 insertion in strain RA1. Computer analysis of the nucleotide sequence revealed an open reading frame (ORF) capable of coding for a protein of 410 amino acids in length. Based on the deduced amino acid sequence, the encoded protein was 46.5 kDa in size and had an isoelectric point of 6.19. The ORF was preceded by a purine-rich ribosomal binding site. Two putative promoter sequences were identified upstream of the ribosomal binding site. The G+C content of the ORF as well as of the flanking regions was calculated to be 46.5%, which is lower than that typical of Brucella spp. (55 to 58%) (19). A BLAST search (3) with the deduced amino acid sequence of the ORF revealed limited homology with various bacterial glycosyltransferases (Table 3). According to the newly suggested nomenclature, this Brucella gene has been named wboA (32a, 33).

TABLE 3.

Homologies of the putative B. abortus glycosyltransferase with other bacterial glycotransferases

| Gene | Organism | Protein size (amino acids) | Putative enzyme | Homologya | Accession no. (GenBank) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rfbU | Salmonella typhimurium | 353 | Mannosyltransferase | 25/43/104 | 141359 |

| rfbW | Synechocystis sp. | 365 | Mannosyltransferase | 19/39/212 | 1001656 |

| wbpX | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 460 | Glycosyltransferaseb | 24/37/186 | 3249545 |

| mtfB | Aquifex aeolicus | 374 | Mannosyltransferase B | 20/38/210 | 2983150 |

| wbdP | Escherichia coli | 404 | Glycosyltransferase | 18/37/249 | 3435176 |

| wbpY | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 371 | Glycosyltransferaseb | 22/38/169 | 3249551 |

Homologies were determined with Gapped BLAST (3). Numbers shown are percentages of identity/percentages of similarity/numbers of amino acids in the region of homology.

The functions of these enzymes have been demonstrated to transfer d-rhamnose by means of an α-1,2 linkage or an α-1,3 linkage (37).

Conversion of B. abortus 2308 from a smooth to a rough phenotype.

B. abortus 2308 transformed with either pJM6 or pJM63 generated 25 kanamycin-resistant and ampicillin-sensitive clones which retained crystal violet and did not react with MAb Bru-38, indicating the loss of the O side chain. DNA hybridization with a Tn5 probe confirmed that the rough phenotype was due to the replacement of the wild-type DNA with the DNA bearing the Tn5 insertion (data not shown).

Complementation of strain RA1.

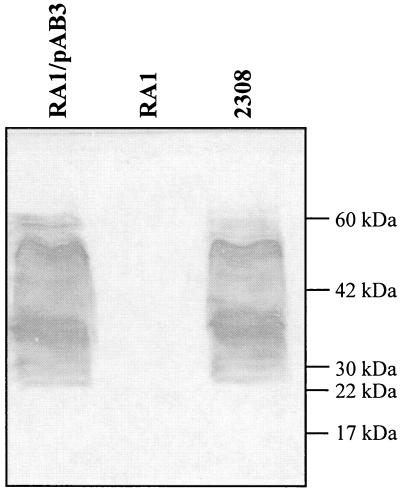

The wboA gene along with the putative promoter sequences was amplified from B. abortus 2308 genomic DNA and cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen). This fragment was subcloned into the SalI and BamHI sites of pBBR1MCS, a broad-host-range plasmid that can replicate in Brucella (24). The ensuing plasmid was designated pAB-3 and electroporated into B. abortus RA1. The resultant chloramphenicol-resistant colonies excluded crystal violet and reacted with MAb Bru-38 in an immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2). The plasmids from these colonies were isolated and shown to be pAB-3 based on restriction mapping and Southern blot analysis (data not shown). These results demonstrate the complementation of the interrupted wboA genomic allele with the intact gene on plasmid pAB-3.

FIG. 2.

Western blot reactions of the indicated B. abortus strains (RA1, RA1/pAB3 [RA1 complemented with a functional B. abortus rfbU gene], and 2308) with the O-side-chain-specific MAb Bru-38. Numbers at the right indicate approximate protein molecular masses.

Immune response and splenic clearance.

BALB/c mice were injected with 1 × 108 to 2 × 108 CFU of either strain RA1 or strain RB51. The mice were killed at various intervals, and the bacterial CFU in their spleens were determined (Table 4). All mice inoculated with strain RA1 had over 103 CFU/spleen at 5 weeks postinfection, and three of five mice were still infected at 7 weeks postinoculation. In contrast, all mice inoculated with strain RB51 were Brucella free at 4 weeks postinfection. All Brucella isolates recovered from spleens were rough and did not contain O side chains as determined by immunoblot analysis (38). All sera from infected mice were negative in the tube agglutination test with smooth Brucella as the antigen and did not react with B. abortus 2308 or Y. enterocolytica O:9 in Western blot analysis (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Clearance of B. abortus RA1 and RB51 from mice spleensa

| No. of days postinfection | Mean log10 CFU/spleen (±SD) in strain:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| RB51 | RA1 | |

| 7 | 4.08 (3.03) | 4.58 (0.73) |

| 14 | 3.19 (2.13) | 4.94 (0.41) |

| 21 | 2.25 (1.39) | 4.31 (0.32) |

| 28 | —b | 3.57 (0.41) |

| 35 | — | 3.12 (0.28) |

| 42 | — | 2.10 (0.98) |

| 49 | — | 0.95 (0.31) |

Infection dose, 2 × 108 CFU (log = 8.3), given intraperitoneally to each of five mice per group.

—, the infection had cleared.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we isolated and characterized B. abortus RA1, a transposon-derived rough mutant of standard strain 2308. We further identified the gene disrupted by Tn5 in strain RA1 as wboA, which encodes a putative glycosyltransferase, an enzyme which appears to be essential for the biosynthesis of the O side chain in B. abortus. LPS analysis of strains RA1 and RB51 indicated that both strains lack the O side chain. However, the reason for the presence of the intermediate LPS band in strain RA1 that is lacking in strain RB51 is not known (Fig. 1). One possibility is that the mutation in strain RA1 results in exposure of a glycose that can be glycosylated by glycosyltransferases that are not able to attach specific sugars in the parent or in strain RB51. The result may be a side branch in the core, generating a new glycoform. Evidence for this is the relatively high amount of galactose present in RA1, whereas only a trace amount of this glycose is present in RB51. Unfortunately, the nature of the mutation causing the RB51 phenotype is unknown. The neutral sugar content of strain 2308 LPS has been reported by Phillips et al. (30) and includes 50% glucose, 20% mannose, 0.5% KDO, 0.63% rhamnose, 0.9% galactose, and 20% unidentified peaks. The detailed structure of strain 2308 core oligosaccharide is not yet known. Although the contents of LPSs from rough mutants of strain 2308 have not been previously reported, our results were most similar to those of Moreno et al. (29). The LPS from strain RB51 was greatly reduced in mannose content and void of quinovosamine, indicating the lack of the O side chain. The intermediate amount of mannose and small amount of quinovosamine in strain RA1 LPS suggest that the mutation may be leaky and that some of the O side chain may be present. However, the epitope reactive with MAb Bru-38 was lacking or below detection in RA1. In contrast, KDO was the predominant glycose in the rough LPSs of strains RA1 and RB51. The deep, rough nature of strain RB51 LPS was also indicated when this LPS was subjected to mild acid hydrolysis. More than 90% of strain RB51 LPS was lipid A, and less than 10% was oligosaccharide. In contrast, substantially more oligosaccharide was isolated from strain RA1 LPS after acid hydrolysis (data not shown). Since MAb Bru-38 did not react with either of these bands (data not shown), it is reasonable to conclude that the bands are most likely part of the core LPS.

DNA sequence analysis demonstrated that the Tn5 element in strain RA1 disrupted the wboA gene, which encodes a protein with homology to several bacterial glycosyltransferases. However, until the substrate utilization by the putative wboA gene product and the actual reaction it catalyzes are confirmed, it is difficult to establish a functional relationship between this B. abortus protein and the other bacterial polysaccharide synthesis gene product(s). Based on the composition of the B. abortus O side chain (9, 12), it can be proposed that the putative WboA is a mannosyltransferase which forms α-1,2 linkages. Several other genes that code for proteins essential for the biosynthesis of the Brucella O side chain have recently been identified (1, 15, 16). In B. melitensis, a gene encoding mannosyltransferase which can form α-1,3 linkages has been reported (16); in the O side chain of B. melitensis, every fifth residue is linked by an α-1,3 linkage (9). As in most other bacterial species, all the Brucella LPS synthesis genes identified so far, including our wboA, also contain low G+C contents (44 to 49%) compared to that of whole genomic DNA (56 to 58%).

B. abortus rough vaccine strain RB51 is highly attenuated and was cleared from mice within 28 days of an intraperitoneal injection of 108 CFU. It is well documented in the literature that inoculation of mice with as few as 104 CFU of strain 2308 results in chronic infections and that 106 CFU of bacteria can be recovered from their spleens up to 12 weeks postinoculation (31). In contrast, only low numbers of strain RA1 were isolated at 6 weeks from the spleens of mice infected with 108 CFU, suggesting that strain RA1 is more virulent than strain RB51 but less virulent than strain 2308. Furthermore, sera from mice infected with strains RA1 and RB51 did not contain antibodies to the O side chain, as was indicated by the lack of reactivity by their sera with the smooth Brucella and Y. enterocolytica O:9 LPSs. These data indicate that the loss of the O side chain by B. abortus results in significant attenuation, as has been demonstrated by others (1, 40). A direct comparison of the degree of in vivo attenuation of strain RA1 with those of Tn5-induced mutants of the other putative polysaccharide synthesis genes (rfbA, rfbD, and rfbV) cannot be made, since our study was carried out with an infectious dose of 108 CFU and that by Allen et al. (1) was carried out with an infectious dose of 104 CFU. Nevertheless, intraperitoneal injection of a few mice with 104 CFU of strain RA1 did not lead to infection beyond 5 days postinoculation (data not shown).

With the wboA gene identified in this study, deletion mutants of rough phenotype have been constructed from B. melitensis and B. suis and have been designated VTRM1 and VTRS1, respectively (48). This indicates that the wboA gene product is essential for O-antigen synthesis in other Brucella spp. of smooth phenotype. It was also demonstrated that, like strain RA1, strains VTRM1 and VTRS1 were less virulent than their parent strains, indicating the essential role of smooth LPS in the virulence of these Brucella species (48).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Animal Health and Disease grant 1-37117 to S.M.B., G.G.S., T.J.I., and N.S. and by a graduate research assistantship to J.R.M. from the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine. The GC-mass spectrometry analysis was supported in part by the USDA/DOE/NSF Plant Science Centers program. The Complex Carbohydrate Research Center was funded by Department of Energy grant DE-FG09-87-ER13810.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen C A, Adams L G, Ficht T A. Transposon-derived Brucella abortus rough mutants are attenuated and exhibit reduced intracellular survival. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1008–1016. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1008-1016.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alton G G, Jones L M, Pietz D E. Laboratory techniques in brucellosis. W. H. O. Monogr. Ser. 55. 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley Interscience; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker P J, Wilson J B. Hypoferremia in mice and its application to the bioassay of endotoxin. J Bacteriol. 1965;90:903–910. doi: 10.1128/jb.90.4.903-910.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck B L, Tabatabai L B, Mayfield J E. A protein isolated from Brucella abortus is a Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry. 1990;29:372–375. doi: 10.1021/bi00454a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertram T A, Canning P C, Roth J A. Preferential inhibition of primary granule release from bovine neutrophils by a Brucella abortus extract. Infect Immun. 1986;52:285–292. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.285-292.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun W, Pomales-Lebron A, Stinberg W R. Interaction between mononuclear phagocytes and Brucella abortus strains of different virulence. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1958;97:393–397. doi: 10.3181/00379727-97-23752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bundle D R, Cherwonogrodzky J W, Perry M B. The structure of the lipopolysaccharide O-chain (M-antigen) and polysaccharide B produced by Brucella melitensis 16M. FEBS Lett. 1987;216:261–264. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80702-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canning P C, Roth J A, Deyoe B L. Release of 5′-guanosine monophosphate and adenine by Brucella abortus and their role in the intracellular survival of the bacteria. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:464–470. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canning P C, Deyoe B L, Roth J A. Opsonin-dependent stimulation of bovine neutrophil oxidative metabolism by Brucella abortus. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:160–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caroff M, Bundle D R, Perry M B, Cherwonogrodzky J W, Duncan J R. Antigenic S-type lipopolysaccharide of Brucella abortus 1119-3. Infect Immun. 1984;46:384–388. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.2.384-388.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans A C. Brucellosis—1949. Washington, D.C: The American Association for the Advancement of Science; 1949. The early history of brucellosis; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frenchick P J, Markham R J F, Cochrane A H. Inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion in macrophages by soluble extracts of virulent Brucella abortus. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:332–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godfroid F, Taminiau B, Danese I, Denoel P, Tibor A, Weynants V, Cloeckaert A, Godfroid J, Letesson J-J. Identification of the perosamine synthetase gene of Brucella melitensis 16M and involvement of lipopolysaccharide O side chain in Brucella survival in mice and in macrophages. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5485–5493. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5485-5493.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godfroid F, Taminiau B, Danese I, Tibor A, Mertens P, De Bolle X, Letesson J-J. 51st Annual Meeting of the Brucellosis Research Conference. 1998. The LPS O-side chain biosynthesis gene cluster of Brucella melitensis 16M; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldman R C, Leive L. Heterogeneity of antigenic-side-chain length in lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli O111 and Salmonella typhimurium LT2. Eur J Biochem. 1980;107:145–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoyer B H, McCullough N B. Homologies of deoxyribonucleic acids from Brucella ovis, canine abortion organisms, and other Brucella species. J Bacteriol. 1968;96:1783–1790. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.5.1783-1790.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inzana T J, Iritani B, Gogolewski R P, Kania S A, Corbeil L B. Purification and characterization of lipooligosaccharide from four strains of Haemophilus somnus. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2830–2837. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.11.2830-2837.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inzana T J, Gogolewski R P, Corbeil L B. Phenotypic phase variation in Haemophilus somnus lipooligosaccharide during bovine pneumonia and after in vitro passage. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2943–2951. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2943-2951.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ish-Horowicz D, Burke J F. Rapid and efficient cosmid cloning. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:2989–2998. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.13.2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jorgensen R A, Rothstein S J, Reznikoff W S. A restriction enzyme cleavage map of Tn5 and the location of a region encoding neomycin resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;177:65–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00267254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovach M E, Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop R M, Peterson K M. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques. 1994;16:800–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai F, Schurig G G, Boyle S M. Electroporation of a suicide plasmid bearing a transposon into Brucella abortus. Microb Pathog. 1990;9:363–368. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreno E, Pitt M W, Jones L M, Schurig G G, Berman D T. Purification and characterization of smooth and rough lipopolysaccharides from Brucella abortus. J Bacteriol. 1979;138:361–369. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.2.361-369.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreno E, Speth S L, Jones L M, Berman D T. Immunochemical characterization of Brucella lipopolysaccharides and polysaccharides. Infect Immun. 1981;31:214–222. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.1.214-222.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno E, Jones L M, Berman D T. Immunochemical characterization of rough Brucella lipopolysaccharides. Infect Immun. 1984;43:779–782. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.779-782.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips M, Pugh G W, Deyoe B L. Chemical and protective properties of Brucella lipopolysaccharides obtained by butanol extraction. Am J Vet Res. 1989;50:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips M, Pugh G W, Deyoe B L. Duration of strain 2308 infection and immunogenicity of Brucella abortus lipopolysaccharide in five strains of mice. Am J Vet Res. 1989;50:318–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Sanguedolce V, Mege J-L, Gorvel J-P. Virulent Brucella abortus avoids lysosome fusion and distributes within autophagosome-like compartments. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2387–2392. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2387-2392.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Reeves, P. R. Personal communication.

- 33.Reeves P R, Hobbs M, Valvano M A, Skurnik M, Whitfield C, Coplin D, Kido N, Klena J, Maskell D, Raetz C R H, Rick P D. Bacterial polysaccharide synthesis and gene nomenclature. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:495–503. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(97)82912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riley L K, Robertson D C. Brucellacidal activity of human and bovine polymorphonuclear leukocyte granule extracts against smooth and rough strains of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1984;46:231–236. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.231-236.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riley L K, Robertson D C. Ingestion and intracellular survival of Brucella abortus in human and bovine polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1984;46:224–230. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.224-230.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roantree R J. The relationship of lipopolysaccharide to bacterial virulence. In: Weinbaum G, Kadis S, Ajl S J, editors. Microbial toxins: a comprehensive treatise. Vol. 5. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1971. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rocchetta H L, Burrows L L, Pacan J C, Lam J S. Three rhamnosyltransferases responsible for assembly of the A-band d-rhamnan polysaccharide in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a fourth transferase, WbpL, is required for the initiation of both A-band and B-band lipopolysaccharide synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1103–1119. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roop R M, Preston-Moore D, Bagchi T, Schurig G G. Rapid identification of smooth Brucella species with a monoclonal antibody. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2090–2093. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.11.2090-2093.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schurig G G, Hammerberg C, Finkler B. Monoclonal antibodies to Brucella surface antigens associated with smooth lipopolysaccharide complex. Am J Vet Res. 1984;45:967–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schurig G G, Roop II R M, Bagchi T, Boyle S M, Burman D, Sriranganathan N. Biological properties of RB51; a stable rough strain of Brucella abortus. Vet Microbiol. 1991;28:171–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90091-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon R, Priefer U, Punhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in-vivo genetic engineering: transposition mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;11:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tarof C W, Hobbs C A. Improved media for growing plasmid and cosmid clones. Focus. 1987;9:12. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai C M, Frasch C E. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verger J-M, Grimont F, Grimont P A D, Grayon M. Brucella, a monospecific genus as shown by deoxyribonucleic acid hybridization. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1985;35:292–295. [Google Scholar]

- 46.White P G, Wilson J B. Differentiation of smooth and nonsmooth colonies of brucellae. J Bacteriol. 1951;61:239–240. doi: 10.1128/jb.61.2.239-240.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilkinson R G, Gemski P, Stocker B A D. Non-smooth mutants of Salmonella typhimurium: differentiation by phage sensitivity and genetic mapping. J Gen Microbiol. 1972;70:527–554. doi: 10.1099/00221287-70-3-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winter A J, Schurig G G, Boyle S M, Sriranganathan N, Bevins J S, Enright F M, Elzer P H, Kopec J D. Protection of BALB/c mice against homologous and heterologous species of Brucella by rough strain vaccines derived from Brucella melitensis and Brucella suis biovar 4. Am J Vet Res. 1996;57:677–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]