Abstract

Germline determination is essential for species survival and evolution in multicellular organisms. In most flowering plants, formation of the female germline is initiated with specification of one megaspore mother cell (MMC) in each ovule; however, the molecular mechanism underlying this key event remains unclear. Here we report that spatially restricted auxin signaling promotes MMC fate in Arabidopsis. Our results show that the microRNA160 (miR160) targeted gene ARF17 (AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR17) is required for promoting MMC specification by genetically interacting with the SPL/NZZ (SPOROCYTELESS/NOZZLE) gene. Alterations of auxin signaling cause formation of supernumerary MMCs in an ARF17- and SPL/NZZ-dependent manner. Furthermore, miR160 and ARF17 are indispensable for attaining a normal auxin maximum at the ovule apex via modulating the expression domain of PIN1 (PIN-FORMED1) auxin transporter. Our findings elucidate the mechanism by which auxin signaling promotes the acquisition of female germline cell fate in plants.

Subject terms: Cell fate, Plant reproduction, Auxin

In most flowering plants, a single megaspore mother cell (MMC) is formed in each ovule. Here the authors show that miR160 and the auxin response factor ARF17 act to promote MMC fate via SPL/NZZ and control auxin signaling to prevent somatic cells from acquiring MMC fate.

Introduction

A longstanding question in both plants and animals is how germline cells are specified to permit sexual reproduction. During the life cycle of flowering plants, the alternation between the diploid sporophyte and haploid gametophyte generations is connected by the specification of a germline post-embryonically in reproductive organs of the flower1. A single megaspore mother cell (MMC), designated as the first committed cell of the female germline lineage, normally originates from a somatic cell in one ovule, a part of the makeup of the female reproductive organ2–4. The MMC undergoes meiosis to yield four haploid megaspores, but only one megaspore named the functional megaspore (FM) survives and gives rise to the female gametophyte (called embryo sac or megagametophyte), which contains one haploid egg cell. Following double fertilization, the seed which typically harbors a single sexually produced embryo is eventually formed. Previous studies have identified several negatively acting regulatory pathways that restrict the female germline to a single MMC per ovule. In Arabidopsis, the inactivation of WUS (WUSCHEL) gene by the RBR1 (RETINOBLASTOMA RELATED1) transcriptional repressor is essential for the MMC formation5,6. A class of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors called KRPs (KIP-RELATED PROTEINs, also known as ICKs: INTERACTOR/INHIBITOR OF CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASEs) represses the inactivation of RBR1 via inhibiting CDKA;1. Functional disruption of KRP/ICK and RBR1 genes causes additional mitotic divisions of differentiated MMC or its precursor, and thus the formation of supernumerary MMCs. In rice and maize, a Leucine-Rich Repeat Receptor-Like Kinase (LRR-RLK)-linked signaling pathway, including the receptor MSP1 (MULTIPLE SPOROCYTE 1) and its putative ligand TDL1A/MAC1 (TAPETUM DETERMINANT-LIKE 1A/MULTIPLE ARCHESPORIAL CELLS 1), prevents differentiation of somatic cells surrounding the MMC into multiple MMCs7–9. Similarly, in Arabidopsis, the cytochrome P450 protein KLU and the chromatin remodeling complex subunit SWR1 co-activate the expression of WRKY28 in somatic cells surrounding the MMC, which suppresses them to acquire the MMC identity10. In addition, trans-acting small interfering RNAs known as tasiR-ARFs repress the expression of ARF3 in cells neighboring the MMC to inhibit the formation of ectopic MMCs11,12. Moreover, the epigenetic regulation associated with AGO9 (ARGONAUTE9), RDR6 (RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE 6), DRM (DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLASE), RNA helicase gene MEM (MNEME), and SPL/NZZ (SPOROCYTELESS/NOZZLE), might use the similar mechanism to control the number of MMC13–22. Although significant progress has been made toward understanding pathways that restrict MMC formation, the molecular mechanism underlying the promotion of MMC identity remains elusive.

The phytohormone auxin acts as a major regulator of patterning and adaptive development in plants23. Its unique property among signaling molecules is the formation of local maxima or gradients as a result of local biosynthesis and, in particular, the polar auxin transport (PAT) mediated by PIN (PIN-FORMED) auxin exporters24–26. Auxin accumulation in individual cells leads to developmental reprogramming via regulating expression of auxin-responsive genes by ARF (AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR) transcription factors27–30. For example, during root development, xylem and phloem cells are derived from a single, bifacial stem cell. A local auxin-signaling maximum specifies the stem cell organizer by activating expression of HD-ZIP III genes (CLASS III HOMEODOMAIN-LEUCINE ZIPPER) via ARF5 [also known as MONOPTEROS (MP)], ARF7, and ARF1931. So far, it is not known whether the positional information provided by auxin signaling is involved in MMC specification.

We previously showed that the Arabidopsis MIR160a (MICRORNA160a) gene loss-of-function mutant foc (floral organs in carpels) is defective in embryogenesis32. miR160 negatively regulates expression of ARF10, ARF16, and ARF1733–35. In Arabidopsis, the spl/nzz mutant fails to develop MMC14,15,17. Here we report that the miR160-targeted ARF17 specifies the MMC by genetically interacting with SPL/NZZ. Auxin signaling is required for MMC formation in an ARF17- and SPL/NZZ-dependent manner, while miR160 and ARF17 define the expression domain of PIN1, which contributes to establishment of the local auxin maximum at the ovule apex. Our findings highlight the importance of the miRNA fine-tuned auxin signaling that controls specification of the initial female germline cell MMC in flowering plants.

Results

Specification of MMC by miR160 and ARF17

In this study, we found that development of 66.1% of ovules was arrested in the foc mutant (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Table 1). To investigate the cause of foc ovule abortion, we analyzed MMC differentiation morphologically using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy combined with examining expression of the MMC marker pKNU::KNU-VENUS by confocal microscopy11,32,36. We first studied MMC differentiation along with early ovule development in wild-type (WT) plants. The dome-shaped ovule primordium arises at stage 1-I (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and elongates at stage 1-II (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Weak to moderate pKNU::KNU-VENUS signals were detected in one subepidermal cell [named MMCP (MMC precursor)] at the distal end of ovule primordia at stages 1-I (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and 1-II (Supplementary Fig. 1b), respectively, although MMCPs are morphologically indistinguishable from other subepidermal cells. Ovules at stage 2-I lack integuments (Supplementary Fig. 1c), while the inner and outer integuments are initiated successively at stages 2-II (Supplementary Fig. 1d) and 2-III (Supplementary Fig. 1e). From stage 2-I to 2-III, MMCs are so designated because pKNU::KNU-VENUS signals are robust in individual MMCs which have larger cell and nucleus size than somatic cells surrounding them (Supplementary Fig. 1c–e). Additionally, we observed two MMC-like (MMCL) cells at stage 2-I at a very low rate (Supplementary Fig. 1f, 4.8%, n = 250); however, pKNU::KNU-VENUS is predominantly expressed in only one MMCL cell. After stage 2-I, the pKNU::KNU-VENUS signal was detected only in one MMC. Our results suggest that MMC originates from MMCP and observations at pre-meiotic stages (stage 2-I to 2-III) are suitable for assessing MMC numbers.

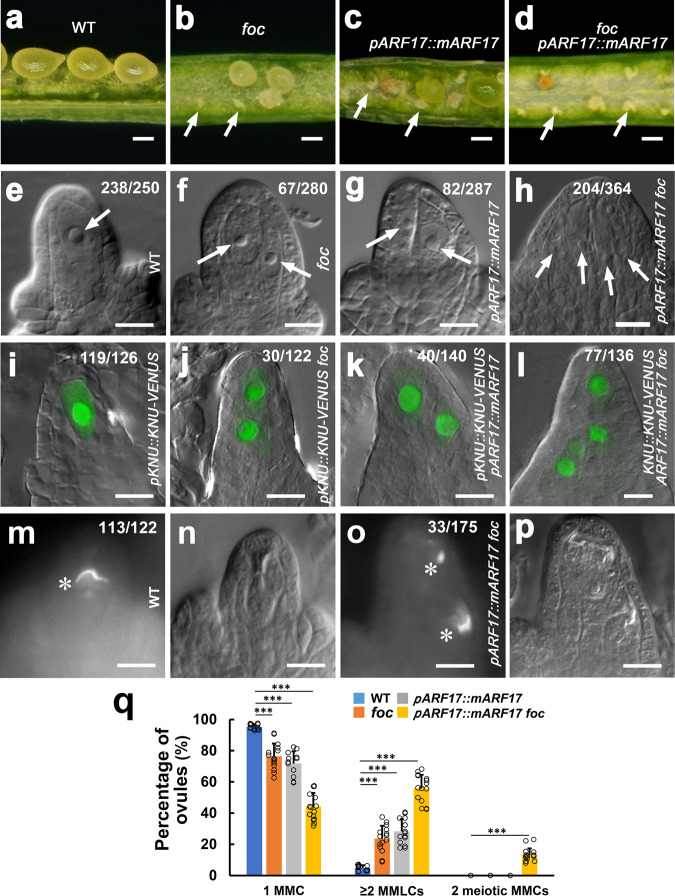

Fig. 1. miR160 and its target ARF17 control MMC formation.

a–d Development of abnormal ovules. Developing seeds in the silique from the Ler wild-type (WT) plant (a), and aborted ovules in siliques of foc (b), ARF17::mARF17 (c), and ARF17::mARF17 foc (d) plants. Arrows indicate aborted ovules. e–p Formation of supernumerary MMCLs and MMCs. e–h Differential interference contrast (DIC) images of ovules showing MMCLs (arrows). i–l Merged confocal and DIC images of ovules expressing pKNU::KNU-VENUS marking the MMC fate. m–p Callose deposition indicating MMC undergoing meiosis. e, i A single MMC in the wild-type (WT) ovule. f, j Two MMCLs in the foc ovule. g, k Two MMCLs in the pARF17::mARF17 ovule. h, l Four MMCLs in the pARF17::mARF17 foc ovule. m–p One MMC in the WT ovule (m) and two MMCs in the pARF17::mARF17 foc ovule (o) undergoing meiosis (denoted by white asterisks). m, o Callose staining. n, p DIC images of (m, o), respectively. q Quantifications of MMCs and MMCLs in WT, foc, pARF17::mARF17, and pARF17::mARF17 foc ovules from 15 individual plants (n = 15 plants; two-sided Student’s t test; Error bars: SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). Source data are provided as a Source data file. Numbers in the panels denote frequencies of phenotypes shown. Scale bars, 1.5 mm (a–d), 10 µm (e–p).

Each WT ovule typically produces one MMC (Fig. 1e, q, 95.2%, n = 250, Fig. 1i, 94.4%, n = 126, and Supplementary Fig. 1c–e) at pre-meiotic stages; however, we observed two or more MMCLs in foc ovules (Fig. 1f, q, 25.7%, n = 280 and Fig. 1j, 24.6%, n = 122), suggesting that miR160 is important for MMC specification. miR160 negatively regulates expression of ARF10, ARF16, and ARF1732–35; therefore, to determine which ARF is involved in MMC specification, we generated pARF10::mARF10, pARF16::mARF16, and pARF17::mARF17 transgenic plants in the Ler background to express their miR160-resistant versions which are no longer subject to miR160’s negative regulation under the control of their own promoters. Eighty percent of ovules and seeds were aborted in pARF17::mARF17 plants (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 1). Notably, as opposed to normal ovules from pARF10::mARF10 and pARF16::mARF16 plants, only ovules from 12 examined pARF17::mARF17 independent lines produced supernumerary MMCLs (Fig. 1g, q, 28.6%, n = 287 and Fig. 1k, 28.6%, n = 140), thus phenocopying foc ovules. When introduced into the foc background, pARF17::mARF17 foc plants showed more aborted ovules (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 1) and an even higher number of supernumerary MMCLs in all 15 examined independent plants (Fig. 1h, q, 56.0%, n = 364 and Fig. 1l, 56.6%, n = 136), possibly due to a dosage effect of ARF17. In addition, analysis of callose deposition that was used as a cytological marker for MMC undergoing meiosis14,16 found that meiosis typically occurred only in one MMC in WT, foc, and pARF17::mARF17 ovules (Fig. 1m, n, 92.6%, n = 122 and Fig. 1q), whereas two MMCs are preparing to enter meiosis in pARF17::mARF17 foc ovules (Fig. 1o, p, 18.9%, n = 175 and Fig. 1q). During later female gametophyte (FG) development37, embryo sacs with various defects were observed both in foc and pARF17::mARF17 plants (Supplementary Fig. 2a–s). Even two embryo sacs were observed in 5.6% of pARF17::mARF17 foc ovules (Supplementary Fig. 2t, n = 216). Taken together, our results suggest that the miR160-controlled ARF17 is a key part of the machinery ensuring specification of a single MMC per ovule in Arabidopsis.

Precise control of ARF17 spatial expression is important for MMC specification

To understand how miR160 and its target ARF17 control MMC specification, we first examined their expression during early ovule development. Whole-mount in situ hybridization studies showed that the MIR160a gene is primarily expressed in chalaza and funiculus of ovules at stage 2-III (Fig. 2a, e). pMIR160a5’::NSL-3xGFP::MIR160a3’ transgenic plants also showed GFP signals mainly in chalaza at stage 2-II (Fig. 2g) and in both chalaza and funiculus at stage 2-III (Fig. 2h), confirming the in situ hybridization results. The mature miR160 was detected not only in chalaza and funiculus but also highly in MMC (Fig. 2b). To test where miR160 acts, we generated the miR160 GFP sensor38 driven by the UBI10 promoter39. GFP signals were ubiquitously detected in pUBI10::NSL-3xGFP ovule cells, including the MMC (Fig. 2i, j, control). In the pUBI10::miR160sensor-NSL-3xGFP ovule, GFP signals were not observed in the MMC and became weaker in the chalaza (Fig. 2k, l), suggesting that the mature miR160 is active in a range of ovule cells, and in particular, the MMC.

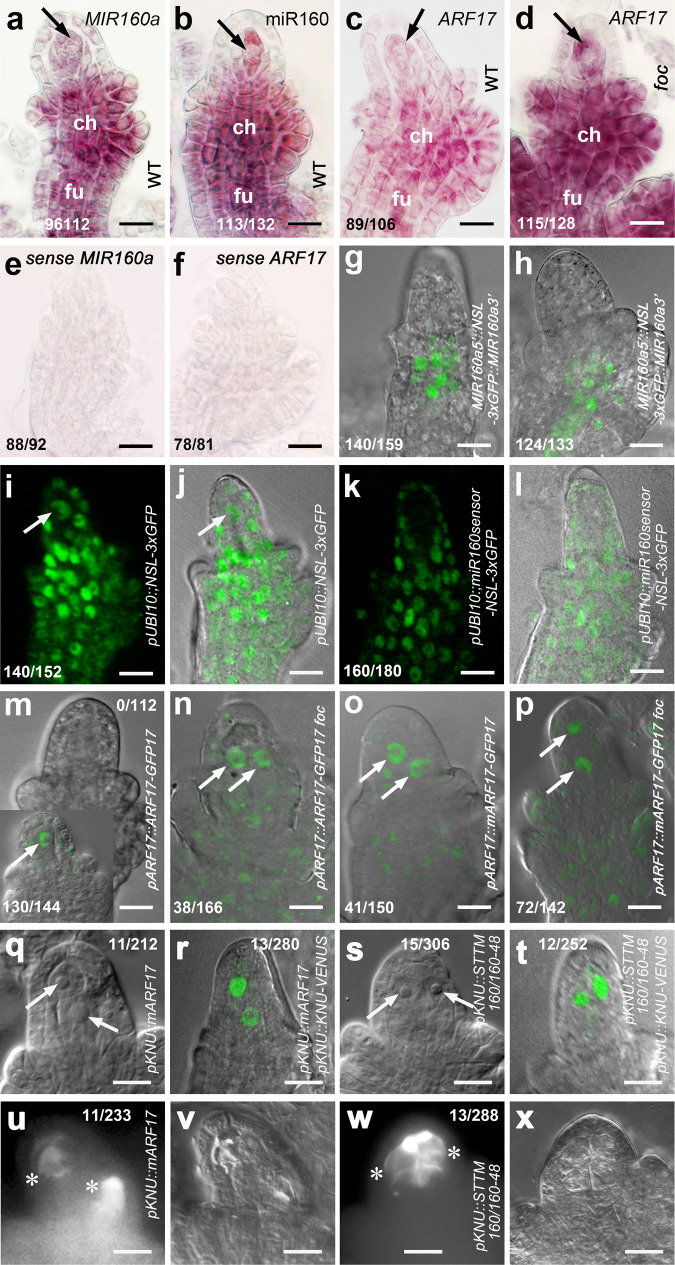

Fig. 2. Expression of miR160 and ARF17 in the MMC is essential for its specification.

a–f Images of whole-mount mRNA in situ hybridization showing expression of the MIR160a (FOC) gene mainly in chalaza (ch) and funiculus (fu) (a) and the mature miR160 also in the MMC (b) in WT ovules at stage 2-III; ARF17 in the MMC, ch, and fu in the WT ovule (c) but with the overall enhancement in the foc ovule (d) at stage 2-III. Arrows: MMC. Sense probes of MIR160a (e) and ARF17 (f), respectively. Experiments were repeated twice with similar results. Merged confocal and DIC images of pMIR160a5’::NSL-3xGFP::MIR160a3’ ovules showing GFP signals mainly in the chalaza at stage 2-II (g) and in both chalaza and funiculus at stage 2-III (h). Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. i–l Examination of the miR160 GFP sensor showing the mature miR160 acts in the MMC (arrows). Confocal (i) and merged confocal and DIC (j) images of the pUBI10::NSL-3xGFP ovule showing ubiquitous expression of GFP signals in ovule cells, including the MMC. Confocal (k) and merged confocal and DIC (l) images of the pUBI10::miR160sensor-NSL-3xGFP ovule showing no signal in the MMC and weaker signals in the chalaza. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. m–p Merged confocal and DIC images showing localization of the ARF17 protein in MMCs/MMCLs (arrows). m Signal was not observed directly under the confocal in the pARF17::ARF17-GFP ovule at stage 2-III, while immunofluorescence assay showing signal in one MMC (the bottom left inset). Confocal microscope readily detected signals in two MMCs/MMCLs of pARF17::ARF17-GFP foc (n), pARF17::mARF17-GFP (o), and pARF17::mARF17-GFP foc (p) ovules at stage 2-III. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. q–x Overexpression of ARF17 in the MMC did not cause the MMC proliferation. q, s DIC images. r, t Merged confocal and DIC images of ovules expressing pKNU::KNU-VENUS. q, r Two MMCs (arrows) were produced at a low rate in the pKNU::mARF17 ovule at 2-III. s, t Two MMCs (arrows) were formed at a low rate in the pKNU::STTM160/160-48 ovule at stage 2-III. Callose deposition indicating two MMCs undergoing meiosis (denoted by white asterisks) in pKNU::mARF17 (u, v) and pKNU::STTM160/160-48 (w, x) ovules. u, w Callose staining. v, x DIC images of (u, w), respectively. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Scale bars, 10 µm.

ARF17 transcripts were observed in the MMC, chalaza, and funiculus in the WT ovule (Fig. 2c, f), with an overall higher level in the foc ovule (Fig. 2d). The GFP signal was not observed in pARF17::ARF17-GFP ovules directly using a confocal microscope (Fig. 2m), however, the ARF17 protein was found in the MMC in a whole-mount immunofluorescence assay of pARF17::ARF17-GFP ovules (Fig. 2m, the bottom left inset), suggesting that a relatively low level of ARF17 protein in the MMC is important for its specification. In contrast, under a confocal microscope ARF17 was readily detected in extra MMCLs of pARF17::ARF17-GFP foc (Fig. 2n), pARF17::mARF17-GFP (Fig. 2o), and pARF17::mARF17-GFP foc (Fig. 2p) ovules. Moreover, weak GFP signals were also present in chalaza and funiculus of these ovules. Our results suggest that the mature miR160 negatively regulates the expression of ARF17.

To test whether expression of ARF17 and miR160 is required for ectopic MMCL formation, we first overexpressed miR160-resistant ARF17 in the MMC using the MMCP and MMC specific promoter pKNU11. A majority of pKNU::mARF17 ovules had one MMC, while two MMCs were observed in ~5% of pKNU::mARF17 ovules (Fig. 2q, 5.2%, n = 212, Fig. 2r, 4.6%, n = 280, and Fig. 2u, v, 4.7%, n = 233). We then employed the STTM (Short Tandem Target Mimic) method40 to knock down miR160 in the MMC using the KNU promoter. Similarly, pKNU::STTM160/160-48 ovules mainly produced one MMC, although 5% of ovules formed two MMCs (Fig. 2s, 4.9%, n = 306, Fig. 2t, 4.8%, n = 252, and Fig. 2w, x, 4.5%, n = 288). In WT, 4.8% of ovules also formed two MMCLs (Supplementary Fig. 1f), which is similar to pKNU::mARF17 and pKNU::STTM160/160-48 ovules, suggesting that miR160 restricts ARF17 expression in ovule cells and overexpression of ARF17 solely in the MMC does not promote MMC proliferation.

ARF17 is required for MMC specification by genetically interacting with SPL/NZZ

To test whether ARF17 is required for MMC specification, we overexpressed ARF17 in the spl mutant, which does not produce MMC14,15,17. Compared with the case in WT (Fig. 3a, 95.2%, n = 250 and Fig. 3e, i, 91.7%, n = 133), almost no MMC (Fig. 3b, 98.9%, n = 180 and Fig. 3f, j, 0%, n = 216) was formed in spl ovules; however, pARF17::mARF17 partially rescued the formation of MMC (Fig. 3c, 44.0%, n = 241 and Fig. 3g, k, 29.8%, n = 141) in the spl mutant. Similarly, the restored MMC differentiation was also observed in the spl foc double mutant (Fig. 3d, 35.2%, n = 210 and Fig. 3h, i, 30.9%, n = 152). No FM was formed in the spl mutant ovule (Fig. 3m, n); however, FM was found in pARF17::mARF17 spl (Fig. 3o, 26.7%, n = 277) and spl foc (Fig. 3p, 24.4%, n = 172) ovules. Moreover, manual pollination led to seed development in both pARF17::mARF17 spl and spl foc plants in comparison with the spl mutant (Supplementary Fig. 3a–d), further suggesting that overexpression of ARF17 could partially enable female gametogenesis in the spl mutant.

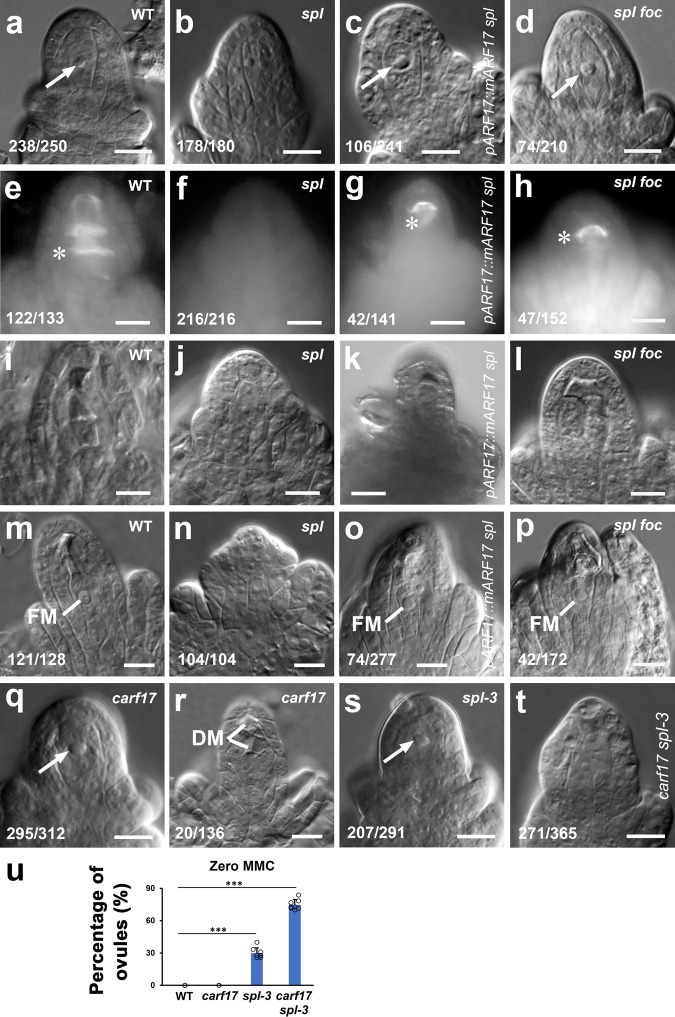

Fig. 3. ARF17 controls MMC specification.

a–l Overexpression of ARF17 in the spl mutant rescued the MMC formation. DIC images showing one MMC in WT (a, arrow), no MMC in spl (b), one MMCL in pARF17::mARF17 spl (c, arrow), and one MMCL in spl foc (d, arrow) ovules. e–l Callose deposition (denoted by white asterisks) displaying one MMC undergoing meiosis in WT (e), pARF17::mARF17 spl (g), and spl foc (h) ovules, but no meiosis occurrence in the spl ovule (f). e–h Callose staining. i–l DIC image of e–h. m–p Overexpression of ARF17 in the spl mutant rescued the functional megaspore (FM) formation. DIC images showing FMs in WT (m), ARF17::mARF17 spl (o), and spl foc (p) ovules, but no FM in the spl ovule (n). q–t Requirement of ARF17 for MMC specification. DIC images showing an MMC in the carf17 ovule (q, arrow) but the abnormal megasporogenesis indicated by all degenerated megaspores (DM, r). DIC images showing an MMC in the spl-3 (s, arrow) ovule, but no MMC in the carf17 spl-3 ovule (t). u Quantifications of zero MMC in WT, carf17, spl-3, and carf17 spl-3 ovules from 8 individual plants (n = 8 plants; two-sided Student’s t test; Error bars: SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). Source data are provided as a Source data file. Numbers in the panels denote frequencies of phenotypes shown. Scale bars, 10 µm.

To further test the requirement of ARF17 for MMC specification, we generated three crispr-arf17 (carf17) independent mutants (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c) and identified a weak spl T-DNA insertion allele spl-3 (Supplementary Fig. 4j, k). The carf17 mutants are normal in vegetative growth (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e), but male sterile (Supplementary Fig. 4f–i). The carf17-6 mutant (still named as carf17 in this paper for simplicity), which has no Cas9, was used for further analysis. Although the MMC differentiation is morphologically normal in the carf17 mutant (Fig. 3q, 94.6%, n = 312 and Fig. 3u), failure of the FM formation was observed (Fig. 3r, 14.7%, n = 1 36). Female fertility of the carf17 mutant was reduced 23.2% (Supplementary Fig. 3a, e), further suggesting that the carf17 mutant is abnormal in FM/embryo sac formation. There were 71.1% of spl-3 ovules with MMC (only 28.9% without MMC, Fig. 3s, n = 291 and Fig. 3u); however, 74.2% of carf17 spl-3 double mutant ovules did not develop MMC (Fig. 3t, n = 365 and Fig. 3u). Collectively, our results suggest that ARF17 is required for promoting MMC specification by genetically acting downstream of SPL/NZZ.

Auxin signaling is involved in MMC specification

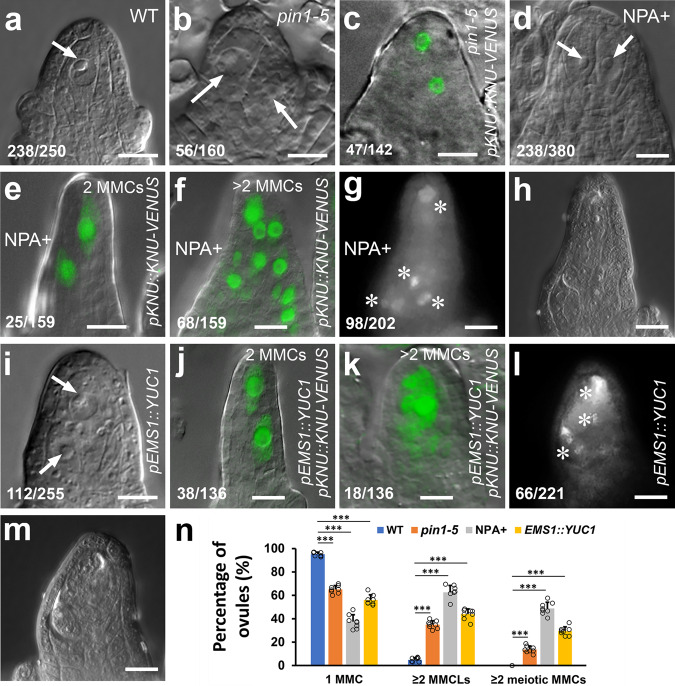

To unravel the molecular mechanism by which miR160 and ARF17 determine the MMC fate, we tested the potential role of auxin signaling in MMC specification. We first examined whether polar auxin transport (PAT) affects MMC formation. Compared with the WT (Fig. 4a, n, 95.2%, n = 250), ovules from the pin1-5 mutant41 produced two or more MMCLs (Fig. 4b, 35.0%, n = 160, Fig. 4c, 33.1%, n = 142, Fig. 4n, and Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). Abnormal embryo sacs were also found in pin1-5 ovules (Supplementary Fig. 5d–h). The PAT inhibitor N-1-Naphthylphthalamic Acid (NPA) inhibits PIN auxin transporters42, thus we continuously applied NPA to WT inflorescences every 24 h for 4 days, which resulted in supernumerary MMCLs (Fig. 4d, n, 62.6%, n = 380, Fig. 4e, 15.7%, n = 159, Fig. 4f, 42.8%, n = 159, and Supplementary Fig. 5i–p) and multiple embryo sacs at different stages per ovule (Supplementary Fig. 5q–x). Callose deposition analysis indicated that multiple MMCLs acquired the MMC identity (Fig. 4g, h, 48.5%, n = 202 and Fig. 4n). Furthermore, we ectopically expressed the auxin biosynthesis gene YUC143 driven by the EMS1 promoter which is active in the epidermis of nucellus and chalaza44. pEMS1::YUC1 led to extra MMCLs (Fig. 4i, 43.9%, n = 255, Fig. 4j, 27.9%, n = 136, Fig. 4k, 13.2%, n = 136, and Fig. 4n) in 10 examined independent transgenic lines. We also observed multiple MMCs accumulating callose (Fig. 4l, m, 29.9%, n = 221, and Fig. 4n). Hence, disruption of PIN-dependent PAT and increased local auxin biosynthesis led to ectopic MMC formation.

Fig. 4. Manipulation of auxin signaling alters MMC specification.

a–c Loss-of-function of PIN1 causing supernumerary MMCLs. DIC images showing one MMC (arrow) in WT (a) and two MMCLs (arrows) in pin1-5 (b) ovules. c A merged confocal and DIC image of the pin1-5 ovule expressing pKNU::KNU-VENUS showing two MMCLs. d–h Inhibiting polar auxin transport by NPA resulting in supernumerary MMCLs and MMCs. d A DIC image showing two MMCLs (arrows) in the 4-day NPA-treated WT ovule. e, f Merged confocal and DIC images of 4-day NPA-treated ovules expressing pKNU::KNU-VENUS marking the MMC fate. e 2 MMCLs. f >2 MMCLs. g, h Callose deposition (denoted by white asterisks) showing multiple MMCs undergoing meiosis in the NPA-treated ovule. g Callose staining. h DIC image of g. i–m Alteration of auxin biosynthesis leading to supernumerary MMCLs and MMCs. i A DIC image showing two MMCLs (arrows) in the pEMS1::YUC1 ovule. j, k Merged confocal and DIC images of pEMS1::YUC1 ovules expressing pKNU::KNU-VENUS marking the MMC fate. j 2 MMCLs. k >2 MMCLs. l, m Callose deposition (denoted by white asterisks) showing multiple MMCs undergoing meiosis in the pEMS1::YUC1 ovule. l Callose staining. m DIC image of l. n Quantifications of MMCs and MMCLs in WT, pin1-5, NPA-treated, and pEMS1::YUC1 ovules from 8 individual plants (n = 8 plants; two-sided Student’s t test; Error bars: SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). Source data are provided as a Source data file. Numbers in the panels denote frequencies of phenotypes shown. Scale bars, 10 µm.

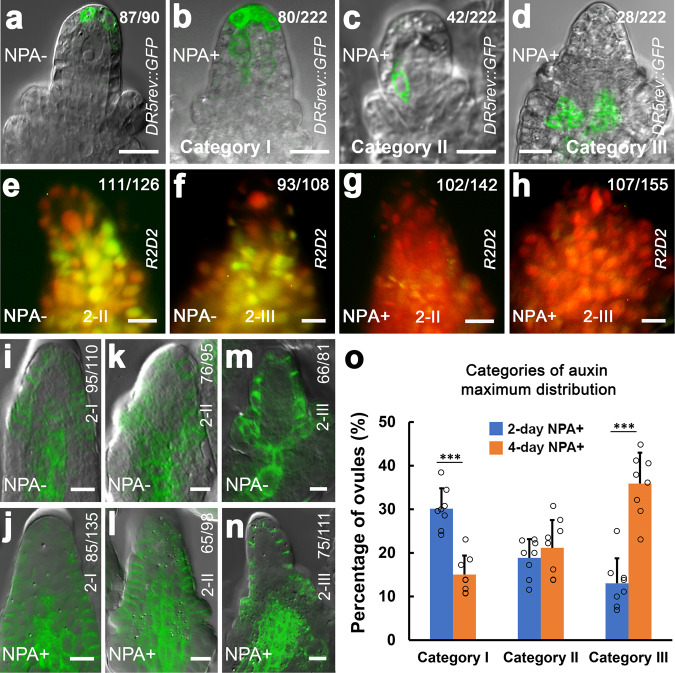

To further characterize the role of auxin signaling in MMC specification, we first investigated auxin response using the auxin response/output marker DR5rev::GFP45 when MMC differentiation is normal or abnormal. We found that the DR5rev::GFP expression represented a single auxin maximum at the apex of the ovule primordium and nucellus (Supplementary Fig. 6). The auxin maximum is restricted to one cell of the epidermal layer at stages 1-I (Supplementary Fig. 6a) and 1-II (Supplementary Fig. 6b) when the MMCP is present (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). At stages 2-I (Supplementary Fig. 6c), 2-II (Supplementary Fig. 6d), and 2-III (Supplementary Fig. 6e) when the MMC becomes distinct (Supplementary Fig. 1c–e), the auxin maximum occupies two or three epidermal cells. After the 2-day NPA treatment, ovules produced supernumerary MMCLs (44.6%, n = 260) and the auxin maximum changed in terms of numbers and positions in most of ovules at stage 2-III (Fig. 5a–d). We summarized these alterations into three categories, which are Category I: expanded apical maxima—auxin maxima are expanded from the apex to underneath cells (Fig. 5b, 30.2%, n = 222 and Fig. 5o), Category II: centrally shifted maxima—auxin maxima are relocated inside nucellus (Fig. 5c, 18.9%, n = 222 and Fig. 5o), and Category III: basally shifted maxima—auxin maxima are moved to the chalaza (Fig. 5d, 12.6%, n = 222 and Fig. 5o). The 4-day NPA treatment significantly increased the percentage of auxin maximum change in the Category III (Fig. 5o). In addition, similar pattern changes of auxin maxima were also observed in pEMS1::YUC1 ovules (Supplementary Fig. 7). We then examined auxin accumulation in ovules using the auxin reporter R2D246. A high level of auxin was detected in nucellus, including the MMC, at stages 2-II (Fig. 5e) and 2-III (Fig. 5f). NPA treatment caused auxin accumulation in both nucellus and chalaza at stages 2-II (Fig. 5g) and 2-III (Fig. 5h).

Fig. 5. Establishment of local auxin signaling in the ovule requires PIN1.

a–d Merged confocal and DIC images of ovules expressing DR5rev::GFP showing three categories of auxin maximum changes after 2-day NPA treatment at stage 2-III. a One auxin maximum at the peak of nucellus without NPA treatment (NPA-). b–d NPA treatment (NPA+). b Category I: expanded apical maxima. c Category II: centrally shifted maxima. d Category III: basally shifted maxima. e–h Accumulation of auxin in ovules. Fluorescence images of ovules expressing R2D2 showing mDII-ntdTomato (red), DII-n3×Venus (green), and overlayed fluorescence signal (yellow). Red color indicates accumulation of auxin. High level of auxin (red) in the nucellus including the MMC without NPA treatment (NPA−) at stages 2-II (e) and 2-III (f). More accumulation of auxin (red) in the nucellus and chalaza with NPA treatment (NPA+) at stages 2-II (g) and 2-III (h). i–n Merged confocal and DIC images of ovules expressing pPIN1::PIN1-GFP showing the PIN1 expression in epidermal cells of nucellus and the central chalaza at stage 2-I (i), in epidermal cells of nucellus, integuments, and the central chalaza at stages 2-II (k) and 2-III (m) without NPA treatment and the expanded PIN1 expression domain in the chalaza after 2-day NPA treatment at stages 2-I (j), 2-II (l), and 2-III (n). o Quantifications of auxin maximum distribution in ovules from eight individual plants at stage 2-III after 2-day and 4-day NPA treatment (n = 8 plants; Two-sided Student’s t test; Error bars: SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). Source data are provided as a Source data file. Numbers in the panels denote frequencies of phenotypes shown. Scale bars, 10 µm.

We also examined the PIN1 expression domain after NPA treatment during ovule development. In pPIN1::PIN1-GFP47 ovules, PIN1 is mainly found in epidermal cells of nucellus at stage 1-I (Supplementary Fig. 8a), then also appeared in one file of cells in the center of chalaza at stage 1-II (Supplementary Fig. 8b). At stages 2-I (Fig. 5i and Supplementary Fig. 8c), 2-II (Fig. 5k and Supplementary Fig. 8d), and 2-III (Fig. 5m and Supplementary Fig. 8e), PIN1 is present in epidermal cells of nucellus, integuments, and in a few files of cells in the central chalaza. The NPA treatment led to expansions of PIN1 expression domain in the central cells of chalaza at stages 2-I (Fig. 5j), 2-II (Fig. 5l), and 2-III (Fig. 5n). In summary, our findings suggest that the spatially restricted auxin activity mediated by PIN1 is important for MMC fate acquisition.

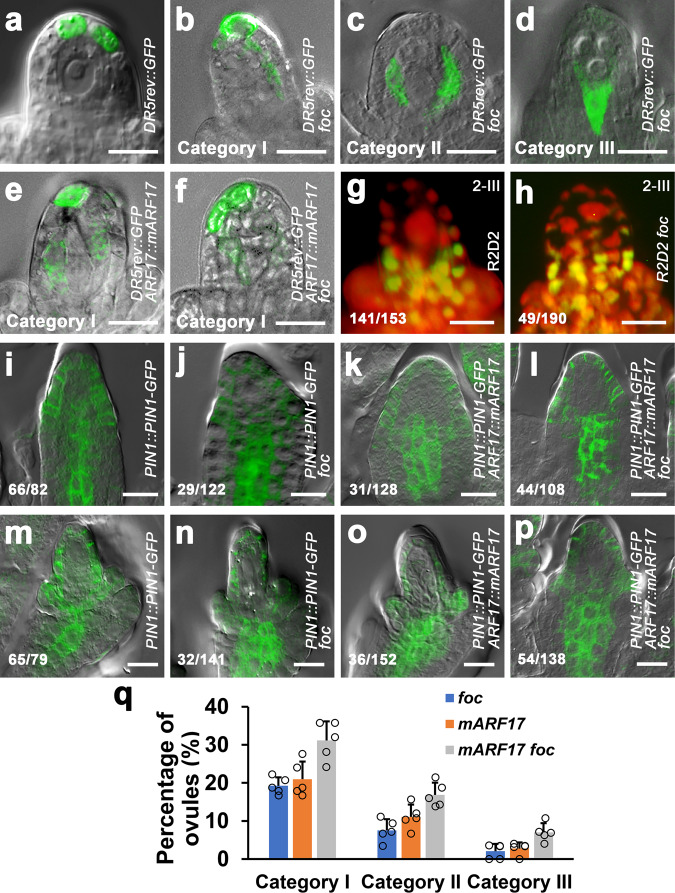

miR160 and ARF17 control establishment of the local auxin maximum via defining the expression domain of PIN1

To gain insight into the possible relationship between the miR160-regulated ARF17 and the local auxin activity in specification of MMC, we examined the potential effects of miR160 and ARF17 on auxin response and accumulation. A single auxin maximum was present at the apex of nucellus in DR5rev::GFP ovules at stage 2-III (Fig. 6a); however, DR5rev::GFP foc ovules showed alterations of auxin maxima in three categories (Fig. 6b–d, q), resembling that NPA-treated ovules (Fig. 5b–d). Similar changes of auxin maxima were also observed in DR5rev::GFP pARF17::mARF17 (Fig. 6e, q) and DR5rev::GFP pARF17::mARF17 foc (Fig. 6f, q) ovules. Examination of R2D2 expression found that more auxin was accumulated in nucellus in foc ovules at stages 2-III (Fig. 6g, h).

Fig. 6. miR160 and ARF17 control the local auxin maximum in ovule via defining the PIN1 expression domain.

a–f Merged confocal and DIC images of ovules expressing DR5rev::GFP showing auxin maximum distributions. a One auxin maximum at the apex of nucellus of the DR5rev::GFP ovule. DR5rev::GFP foc ovules showing changes of auxin maxima in Category I (b, expanded apical maxima), Category II (c, centrally shifted maxima), and Category III (d, basally shifted maxima). Auxin maxima in Category I from DR5rev::GFP pARF17::mARF17 (e) and DR5rev::GFP pARF17::mARF17 foc (f) ovules. g, h Changes of auxin accumulation in the foc ovule. Fluorescence images of ovules expressing R2D2 showing a high level of auxin (red) in the nucellus, especially in the MMC of the WT ovule at stage 2-III (g) but auxin accumulation in extra MMCLs in the nucellus of the foc ovule at stage 2-III (h). Merged confocal and DIC images of ovules showing the effect of foc and ARF17 on PIN1 expression domain at stages 2-I (i–l) and 2-III (m–p). i, m PIN1 is present at the nucellus epidermis, the center of chalaza, and integuments in pPIN1::PIN1-GFP ovules. The PIN1 domain is expanded in chalaza in pPIN1::PIN1-GFP foc (j, n), pPIN1::PIN1-GFP pARF17::mARF17 (k, o), and pPIN1::PIN1-GFP pARF17::mARF17 foc (l, p) ovules. q Quantifications of auxin maximum distribution in DR5rev::GFP foc, DR5rev::GFP pARF17::mARF17, and DR5rev::GFP pARF17::mARF17 foc ovules from five individual plants (n = 5 plants; Error bars: SD). Source data are provided as a Source data file. Numbers in the panels denote frequencies of phenotypes shown. Scale bars, 10 µm.

We then tested whether miR160 and ARF17 regulate the PIN1 expression domain. Compared to its expression in pPIN1::PIN1-GFP ovules (Fig. 6i, m and Supplementary Fig. 9a), PIN1 expression domains were expanded in the central chalaza of pPIN1::PIN1-GFP foc (Fig. 6j, n and Supplementary Fig. 9b), pPIN1::PIN1-GFP pARF17::mARF17 (Fig. 6k, o and Supplementary Fig. 9c), and pPIN1::PIN1-GFP pARF17::mARF17 foc (Fig. 6l, p and Supplementary Fig. 9d) ovules at stages 1-II, 2-I, and 2-III. Our results suggest that Moreover, ARF17 genetically interacts domains of PIN1, which is critical for establishment of a single local auxin maximum at the ovule apex and accumulation of auxin in nucellus, including the MMC.

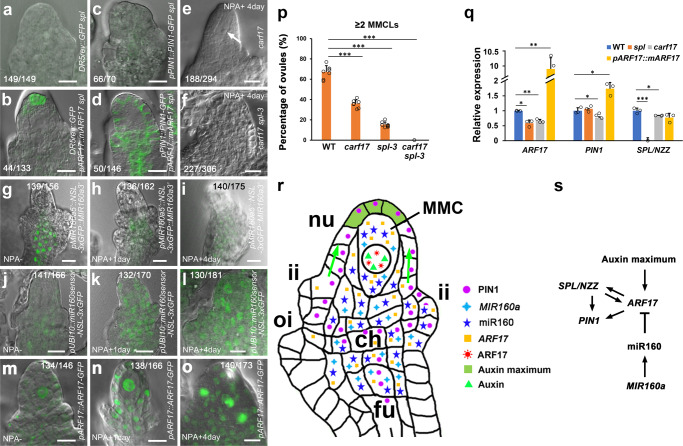

Auxin signaling specifies MMC through ARF17 and SPL/NZZ

We finally tested whether auxin signaling controls MMC specification through ARF17 and SPL/NZZ. The auxin maximum was almost undetectable at the apex of DR5rev::GFP spl ovule where the MMC is not formed (Fig. 7a, 100%, n = 149); however, in the DR5rev::GFP pARF17::mARF17 spl ovule with the MMC, the auxin maximum was restored to the ovule apex (Fig. 7b, 33.1%, n = 133). As described previously48, PIN1 was almost not observed either in the epidermis of nucellus or the central chalaza in the pPIN1::PIN1-GFP spl ovule (Fig. 7c, 94.3%, n = 70), while the PIN1 expression was recovered in the pPIN1::PIN1-GFP pARF17::mARF17 spl ovule (Fig. 7d, 34.2%, n = 146). Our results suggest that miR160-regulated ARF17 is required for attaining the PIN1-established auxin maximum at the ovule apex. After a 4-day NPA treatment, 62.6% of WT ovules produced supernumerary MMCLs (Fig. 4d, n = 380 and Fig. 7p), but 36.1% of carf17 (Fig. 7e, p, n = 294) and 15.2% of spl-3 (Fig. 7p, n = 344) ovules formed extra MMCLs. MMC was not found in 74.2% of carf17 spl-3 double mutant ovules (Fig. 3t, n = 365). NPA treatment did not induce the formation of MMC in 74.9% of carf17 spl-3 ovules and 25.1% ovules only formed one MMC (Fig. 7f, p, n = 306). Thus, the failure of supernumerary MMCL production in NPA-treated carf17 spl-3 ovules suggests that the auxin signaling-induced MMC specification requires ARF17 and SPL/NZZ.

Fig. 7. Auxin signaling controls MMC specification through ARF17 and SPL/NZZ.

a–d Merged confocal and DIC images of ovules showing rescued auxin signaling by overexpression of ARF17. a Absence of auxin maximum in the DR5rev::GFP spl ovule. b The restored auxin maximum to the apex of nucellus in the DR5rev::GFP pARF17::mARF17 spl ovule. c Almost no detectable PIN1 in the pPIN1::PIN1-GFP spl ovule. d Partially rescued PIN1 expression at the epidermis of nucellus and chalaza in the pPIN1::PIN1-GFP pARF17::mARF17 spl ovule. e, f DIC images of ovules showing one MMC (arrow) in the carf17 ovule, but no MMC in the carf17 spl-3 ovule after NPA treatment. g–i NPA treatment represses the MIR160a (FOC) expression. Merged confocal and DIC images of pMIR160a5’::NSL-3xGFP::MIR160a3’ ovules showing the decreased expression of MIR160a in chalaza after 1-day (h) and 4-day (i) NPA treatment comparing with the control (g). j–l NPA treatment represses the miR160 accumulation. Merged confocal and DIC images of pUBI10::miR160sensor-NSL-3xGFP ovules showing increased GFP signals in nucellus, particularly the MMC, and chalaza after 1-day (k) and 4-day (l) NPA treatment comparing with the control (j). m–o NPA treatment increases the ARF17 protein expression in MMCLs. Merged confocal and DIC images of pARF17::ARF17-GFP ovules showing elevated levels of ARF17 protein in MMCLs and other subepidermal nucellus cells after 1-day (n) and 4-day (o) NPA treatment comparing with the control (m). p Quantifications of ≥2 MMCLs in WT, carf17, spl-3, and carf17 spl-3 ovules with NPA treatment from eight individual plants (n = 8 plants; two-sided Student’s t test; Error bars: SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). q qRT-PCR results showing expression of ARF17, PIN1, and SPL/NZZ in WT, spl, carf17 and pARF17::mARF17 ovules. Values were normalized as relative expression to ACTIN2. (n = 3 biological replicates; two-sided Student’s t test; Error bars: SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). Source data are provided as a Source data file. r A model illustrating the MMC specification controlled by miR160-orchestrated auxin signaling. Green arrows indicate auxin flow. Colored shapes indicate presence of the mature miR160, auxin, mRNAs, and proteins. ch chalaza, fu funiculus, ii inner integument, MMC megaspore mother cell, nu nucellus, and oi outer integument. s The proposed regulatory network associated with auxin signaling, MIR160a, miR160, ARF17, PIN1, and SPL/NZZ during the MMC specification. Arrows indicate the positive regulation/interaction, while the T-bar indicates the negative regulation/interaction. Numbers in the panels denote frequencies of phenotypes shown. Scale bars, 10 µm.

To examine whether auxin signaling regulates expression of MIR160a (FOC), miR160, and ARF17, we treated pMIR160a5’::NSL-3xGFP::MIR160a3’32, pUBI10::miR160sensor-NSL-3xGFP, and pARF17::ARF17-GFP plants with NPA. The expression of MIR160a gene was decreased after 1-day and 4-day NPA treatments (Fig. 7g–i), and NPA treatment decreased accumulation of the mature miR160 in the MMC and other cells in nucellus and chalaza (Fig. 7j–l). Conversely, 1-day and 4-day NPA treatments enhanced the expression of ARF17 protein in subepidermal nucellus cells, especially in MMCLs (Fig. 7m–o), suggesting that the formation of MMC requires ARF17. Furthermore, qRT-PCR results showed the expression of ARF17 was decreased in the spl ovule, and the expression of SPL/NZZ was also decreased in the carf17 ovule (Fig. 7q). The expression of PIN1 was decreased in the carf17 ovule but increased in the pARF17::mARF17 (Fig. 7q) ovule. In summary, our results suggest that auxin signaling modulated by the miR160-targerted ARF17, SPL/NZZ, and PIN1 provides the spatially restricted information for the proper specification of a single MMC per ovule.

Discussion

In many animals, germline cells are differentiated and segregated from soma during early embryogenesis, whereas flowering plants generate male and female germline cells post-embryonically in a flower. Previous studies have reported that several pathways involved in cell cycle control, signal transduction, ta-siRNAs, and epigenetic regulation restrain the number of MMCs, i.e., the female germline cells5–14,16. Here we report that the miRNA-controlled, spatially restricted auxin signaling promotes the specification of one MMC per ovule in Arabidopsis (Fig. 7r, s). During the normal ovule development, the MIR160a gene is expressed in ovule cells, while the mature miR160 is particularly active in a single hypodermal cell, which is underneath the auxin maximum at the apex of ovule (Figs. 2a–i, 5a and 7r). miR160 downregulates the expression of ARF17 (Fig. 2c, d), whereas auxin induces the expression of ARF1732. The ARF17 protein is mainly found in the MMC (Fig. 2m–p). Auxin present in the MMC might activate ARF17 (Fig. 5e, f). Moreover, ARF17 genetically interacts with SPL/NZZ (Fig. 3), and they possibly affect each other’s expression (Fig. 7q). ARF17 and SPL/NZZ also affect the PIN1 expression domain (Figs. 6i–p and 7c, d), which may contribute to the establishment of auxin maximum at the apex of ovule and accumulation of auxin in the MMC (Fig. 5a–h). Thus, a delicate balance between miR160 and auxin signaling leads to a precise control of ARF17 function, which promotes one hypodermal cell to acquire the MMC identity (Fig. 7r, s).

SPL/NZZ and ARF3 are important for MMC differentiation, as the spl/nzz mutant fails to form MMC15,17 and ectopic expression of ARF3 results in extra MMCLs12. The MADS-box transcription factor STK (SEEDSTICK) upregulates expression of AGO9, RDR6, and DRM, while AGO9, RDR6, and DRM epigenetically repress the expression of SPL/NZZ14. Ectopic expression of SPL/NZZ in ovules of stk, drm1 drm2, ago9-2, rdr6-11 mutants, and the 35S::SPL/NZZ plant leads to the formation of supernumerary MMCL, but only one of these MMCLs expresses the MMC marker KNU and undergoes meiosis. Furthermore, both the SPL/NZZ transcript and the SPL/NZZ protein are restricted to only a few cells of nucellus epidermis, but they are not present in the MMC or its precursor cell. These results suggest that SPL/NZZ is not sufficient for the complete differentiation of MMC, although it is required for the initial MMC specification non-cell autonomously. SPL/NZZ was suggested to be involved in auxin homeostasis49. A recent study showed that auxin distribution is associated with differentiation of the male germ cell PMC (pollen mother cell)50. Mutations in auxin biosynthesis genes TAA1 (TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE OF ARABIDOPSIS 1) and TAR2 (TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE RELATED 2) impair the PMC formation, whereas ectopic expression of SPL/NZZ partially rescues the PMC specification. Different from its expression pattern in MMC, SPL/NZZ is expressed in PMC, suggesting that SPL/NZZ might directly promote the PMC differentiation. Nevertheless, the elevated expression of SPL/NZZ does not result in excess PMC but the loss of PMC identity in anthers. tasiR-ARFs maintain the expression of ARF3 at the basal end of chalaza via suppressing its expression in apical and hypodermal MMC neighbor cells, which may prevent them from acquiring the MMC fate12. Ectopic expression of the ARF3 protein in the subepidermal cells surrounding the MMC causes supernumerary MMCLs. However, the fact that ARF3 is not expressed in the MMC suggests that ARF3 does not directly specify MMC.

A complex auxin signaling pathway which involves ARF17, SPL/NZZ, and PIN1 is required for MMC specification. The auxin maximum is restricted to one to three cells in the epidermal layer at the apex of nucellus with the progress of MMC differentiation. One hypodermal cell underneath the auxin maximum enlarges and eventually differentiate into MMC. In the spl ovule which fails to develop the MMC, the auxin maximum is not formed at the tip of nucellus (Fig. 7a), and PIN1 is not present in the epidermal cells of nucellus, integuments, and the central chalaza (Figs. 5i–m and 7c). Overexpression of ARF17 can restore the auxin maximum to the nucellus apex by rescuing the normal PIN1 expression in the spl ovule (Fig. 7a–d), suggesting that auxin signaling modulated by ARF17, SPL/NZZ, and PIN1 are important for MMC differentiation. In the apomictic Hieracium subgenus Pilosella ovule, NPA treatment increases the expression level of DR5::GFP and alters the DR5::GFP expression domain51. However, NPA treatment does not affect the MMC differentiation, although the number of aposporous initial cells is increased, suggesting that auxin signaling might play a more dominant role in the apomixis process in apomictic species.

We found that the formation of supernumerary MMCLs in foc, pARF17::mARF17, pARF17::mARF17 foc, pEMS1::YUC1, pin1-5, and NPA-treated ovules is associated with location changes of auxin maxima. These MMCLs express the MMC marker KNU and a portion of them accumulate callose, suggesting that they are preparing to undergo meiosis. Not only in the distal end of nucellus, MMCLs were also observed in other nucellus region (Figs. 1i and 4f, g, k, l and Supplementary Fig. 5o, p). We also observed the ARF17 protein primarily in the normally differentiated MMC as well as in supernumerary MMCLs caused by the ectopic expression of ARF17 (Fig. 2m–p) and by the alteration of auxin signaling (Fig. 7m–o). The acquisition of MMC identity depends on ARF17 (Figs. 3u and 7p); however, overexpression of ARF17 specifically in the MMCP/MMC does not result in the formation of supernumerary MMCLs (Fig. 2q–x). Therefore, different from previously studied regulators5–22, our results suggest that ARF17 is a key determinant for promoting the MMC specification instead of the MMC proliferation. Collectively, we uncover a molecular mechanism underlying the MMC fate determination, which thus lays the foundation to female germline in plants.

Methods

Plant materials

Arabidopsis thaliana Landsberg erecta (Ler) was used as the wild type (WT) unless otherwise noted. The mutants, marker lines, and transgenic lines used in this study were foc32, spl15,17, DR5rev::GFP45, pKNU::KNU-VENUS11, pin1-541, pPIN1::PIN1-GFP47, pPIN1::PIN1-GFP spl48, spl-3* (SALK_090804, * indicated generated/identified in this study), pAT5G01860::n1GFP* (the female gametophyte marker)52, pAT5G45980::n1GFP* (the egg cell marker)52, pAT5G50490::n1GFP* (the central cell marker)52, pAT5G56200::n1GFP* (the antipodal cell marker)52, pARF17::ARF17*, pARF10::mARF10*, pARF16::mARF16*, pARF17::mARF17*, pARF17::mARF17 foc*, pKNU::KNU-VENUS foc*, pKNU::KNU-VENUS pARF17::mARF17*, pKNU::KNU-VENUS pARF17::mARF17 foc*, pKNU::mARF17*, pKNU::mARF17 pKNU::KNU-VENUS*, pKNU::STTM160/160-48*, pKNU::STTM160/160-48 pKNU::KNU-VENUS*, pARF17::ARF17-GFP*, pARF17::mARF17-GFP*, pMIR160a5’::NSL-3xGFP::MIR160a3’*, pUBI10::NSL-3xGFP*, pUBI10::miR160sensor-NSL-3xGFP*, pUBI10::NSL-3xGFP foc*, pUBI10::miR160sensor-NSL-3xGFP foc*, pEMS1::YUC1*, pKNU::KNU-VENUS pEMS1::YUC1*, DR5rev::GFP pEMS1::YUC1*, crispr-arf17 (carf17)*, spl-3 carf17*, DR5rev::GFP foc*, DR5rev::GFP pARF17::mARF17*, DR5rev::GFP pARF17::mARF17 foc*, pARF17::mARF17 spl*, foc spl*, DR5rev::GFP spl*, DR5rev::GFP pARF17::mARF17 spl*, pPIN1::PIN1-GFP foc*, pPIN1::PIN1-GFP pARF17::mARF17*, pPIN1::PIN1-GFP pARF17::mARF17 foc*, pPIN1::PIN1-GFP pARF17::mARF17 spl*, R2D2 (auxin accumulation marker)46, and R2D2 foc*. These plants were either in the Ler background or crossed into the Ler background five times before examination.

Plant growth conditions

All plants were grown in Metro-Mix 360 soil (Sun-Gro Horticulture City State) in growth chambers under a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod, at 22 °C and 50% of humidity.

Generation of constructs and transgenic plants

For genetic analyses, gene expression, and protein localization studies, promoters of ARF10, ARF16, and ARF1734 were cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). Site mutations of ARF1035, ARF1634, and ARF1733 cDNAs were generated by overlapping PCR to produce miR160-resistant versions of mARF10, mARF10, and mARF17. The mARF10, mARF16, and mARF17 were cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO vectors containing corresponding promoters to generate pENTR-pARF10::mARF10, pENTR-pARF16::mARF16, and pENTR-pARF17::mARF17, respectively.

The MIR160a 5’ promoter32 was PCR-amplified from the BAC clone T16B24 with KpnI and XbaI digestion sites and then cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO vector to generate pENTR-pMIR160a5’. An NSL-3xGFP fragment was digested by KpnI and XbaI from pGreenII KAN SV40-3×GFP53 and inserted into the pENTR-pMIR160a5’ to produce the pENTR-pMIR160a5’::NSL-3xGFP vector. The PCR-amplified MIR160a3’ fragment was then inserted into pENTR-pMIR160a5’::NSL-3xGFP at XbaI and AscI sites to generate pENTR-pMIR160a5’::NSL-3xGFP::MIR160a3’.

To generate the nucleus-localized GFP-based miR160 sensor construct, a 634 bp genomic DNA fragment of the UBI10 promoter was first PCR-amplified from the genomic DNA of Ler39. pMIR160a5’ was replaced by pUBI10 through SacII + KpnI sites in the pENTR-pMIR160a5’::NSL-3xGFP vector to generate pENTR-pUBI10::NSL-3xGFP. The UBI10 promoter with the sensor sequence (TGGCATGCAGGGAGCCAGGCA)38 at the 3’ end was PCR-amplified and the resulting fragment was used to replace pMIR160a5’ in the pENTR-pMIR160a5’::NSL-3xGFP vector to produce pENTR-pUBI10::miR160sensor-NSL-3xGFP.

The PCR-amplified 2 kb KNU promoter11 was amplified from the genomic DNA of Ler and cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector to generate pENTR-pKNU. The mARF17 was PCR-amplified as described above and subsequently cloned into pENTR-pKNU to produce pENTR-pKNU::mARF17. The fragment containing the sequence of an STTM (Short Tandem Target Mimic) targeting the miR160 was PCR-amplified from the STTM160/160-4840 construct and then cloned into pENTR-pKNU to generate pENTR-pKNU::STTM160/160-48.

The PCR-amplified 1.7 kb EMS1 promoter was cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector to generate pENTR-pEMS144. The YUC1 cDNA was PCR-amplified from the pCHF3 plasmid43 and subsequently cloned in the pENTR-EMS1 vector to produce pENTR-pEMS1::YUC1.

To generate crispr-arf17 (carf17) lines, the egg cell-specific promoter-controlled Cas9 vector pHEE401E was used in this study54. Target sites of 23-bp sequences were searched using CRISPR-PLANT (https://www.genome.arizona.edu/crispr/CRISPRsearch.html). A pair of synthesized 23-nt oligoes (100 μmol/l each) containing the target site within the first exon and the BsaI digestion site were heated at 95 °C for 5 min and annealed at the room temperature. Then the Golden Gate reaction was conducted with the annealed insert, the pHEE401E vector, BsaI-HF®v2 (NEB #R3733), and the T4 DNA Ligase (NEB # M0202T) to produce the crispr-arf17 construct.

The pGWB1 binary vector was used for genetic and expression analyses, while the pGWB4 binary vector harboring the GFP gene was employed for protein localization studies55. The final constructs pARF10::mARF10, pARF16::mARF16, pARF17::mARF17, pKNU::mARF17, pKNU::STTM160/160-48, pARF17::ARF17-GFP, pARF17::mARF17-GFP, pMIR160a5’::NSL-3xGFP::MIR160a3’, pUBI10::NSL-3xGFP, pUBI10::miR160sensor-NSL-3xGFP, and pEMS1::YUC1 were generated using the Gateway LR Recombinase II Enzyme Mix (Invitrogen). Detailed information for all constructs and primers is shown in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. The resulting vectors were transformed into Agrobacterium strain GV3101 and plant transformation was performed using the floral dip method56. The transformants were screened on ½ Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates containing 25 μg/ml hygromycin.

NPA treatment

The 50 mM of auxin transport inhibitor N-1-Naphthylphthalamic Acid (NPA) (Sigma; N-12507-250MG) stock solution was prepared in DMSO57. The working NPA solution was 50 µM in 0.01% of Silwet L-77 (Lehle Seeds, Round Rock, TX, USA). The solution containing 0.1% of DMSO and 0.01% of Silwet L-77 was used for mock treatment. One drop of NPA solution was applied to the top of the main inflorescence at 10 a.m. every day. Samples were collected at 2 days and 4 days for analyses.

Whole-mount RNA in situ hybridization and qRT-PCR

RNA in situ hybridization was carried out in whole-mount ovules58. The probes of MIR160a and ARF17 were described in our previous studies32. A miRCURY LNA™ Detection probe with the DIG oligonucleotide 3-end labeling (5’-TGGCATACAGGGAGCCAGGCA-3’) was synthesized (Exiqon) for examining the expression of mature miR16059. Briefly, pistils were removed from flowers and opened along one side of replum. Opened pistils were fixed with vacuum for 1 h. After a series of processes, including chlorophyll removal, permeabilization, and hybridization, ovules were dissected out from pistils for signal detection using Western Blue® (Promoga). Images were taken via an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with an Olympus DP 70 digital camera.

For quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)32,60,61, ovules at stages 2-II and 2-III were collected under dissection microscope from WT, spl, carf17, and pARF17::mARF17 gynoecia. Total RNAs were extracted using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription reactions were then conducted via a QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) after determining the RNA concentration by a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The quantitative real time PCR (DNA Engine Opticon 2 system) were performed using the Fast SYBR Green PCR Master Mix and primers listed in Table S3. ACTIN2 was used as an internal control. Three biological replicates were performed.

Whole-mount immunolocalization

For whole-mount immunolocalization, pistils were harvested, dissected under a dissection microscope, and then embedded in the polyacrylamide solution62. A coverslip was put on the top of the polyacrylamide solution and a tweezer was used to press the coverslip to push ovules out of the pistils. Ovules were permanently embedded in the polyacrylamide matrix after polymerization at room temperature for at least 20 min. After cell wall digestion and cell membrane permeabilization, ovules were blocked by 1% of BSA for 1 h at 37 °C. The anti-GFP antibody (Torrey Pines Biolabs; catalog no. TP401) was applied by 1:100 dilution overnight. After washing five times each for 15 min, samples applied the secondary antibody Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG Antibody (Alexa Fluor® 488) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab; 111-545-003) were incubated overnight. One drop of Prolong Live Antifade reagent (Life Technologies; P36975) was applied to samples which were washed five times each for 15 min. The samples were then mounted for observation. All steps were carried out at 4 °C unless otherwise noted.

Phenotypic analyses and microscopy

To examine megaspore mother cell (MMC) differentiation, flower buds were collected and fixed in 37% of methanol stabilized formaldehyde at room temperature with vacuum for 1 h. A graded ethanol series (20% of increments) was carried out for bud clearance. Ovules were dissected out from pistils and mounted in the Hoyer’s solution63 overnight before imaging. Ovules were photographed on a Leica TCS SP2 laser scanning confocal microscope under Differential interference contrast (DIC) optics.

Ovules examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were performed as described in our previous studies32 using a Hitachi S-570 scanning electron microscope.

The ovule semi-thin section was conducted based on our previous studies60,61,64. Images were photographed by an Olympus BX51 microscope through an Olympus DP 70 digital camera.

Callose deposition assay was conducted for examining MMC meiosis14,16. Briefly, inflorescences were fixed by FAA for 16 h and washed by 1xPBS three times each for 10 min. Pistils were incubated in 0.1% of aniline blue in 100 mM of Tris (pH 8.5) for 12 h. Ovules were dissected out in 30% of glycerol and observed with an Olympus (BX51) microscope under the UV light (365-nm excitation and 420-nm emission). Three biological replicates were performed.

Ovules from plants expressed R2D2 were dissected and mounted in 10% of glycerol. Fluorescence filters for TRITC and FITC were used to acquire signals of tdTomato65 and VENUS66, respectively.

For analyzing GFP signals, ovules were mounted in water and observed with a Leica TCS SP2 laser scanning confocal microscope using a ×63/1.4 water immersion objective lens. The 488-nm laser line was used to excite GFP. The PMT gain settings was held at 650. The emission was detected using PMTs set at 505–530 nm. Images were processed with ImageJ and Photoshop CS6 using the same settings.

Quantification and statistical analysis

For each experiment, numbers of ovules were collected from 10–20 plants. We used a Leica TCS SP2 laser scanning confocal microscope under Differential interference contrast (DIC) optics to count numbers of ovules with zero MMC, one MMC, and multiple MMCLs based on the MMC morphology and expression of the MMC marker KNU::KNU-VENUS. Meiotic MMCs were determined by callose staining. Numbers of ovules with different expression patterns of DR5rev::GFP were counted with a Leica TCS SP2 laser scanning confocal microscope. The “n” represents the total number of ovules analyzed. Three biological replicates were performed for each experiment. The statistical significance was evaluated by the Student’s t test. For the qRT-PCR assay, three biological replicates were performed, and the data were analyzed by the comparative C(T) method67. Bars indicate standard deviation. Asterisks indicate p < 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Cheung, W. Lukowitz, V. Walbot, D. Weijers, and R. Yadegari for critically reading the manuscript; E. Xiong and G. Zhang for preparing some experiments, T. Schuck, J. Gonnering, and P. Engevold for plant care, the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC) for ARF10, ARF16, ARF17, EMS1, MIR160a BAC clones and cDNAs, the SALK_090804 seed, T. Nakagawa for pGBW vectors, Y. Zhao for the YUC1 cDNA, Q. Chen for the pHEE401E vector, R. Yadegari for pAT5G01860::n1GFP, pAT5G45980:n1GFP, pAT5G50490::n1GFP, pAT5G56200:n1GFP vectors, and D. Weijers for the pGreenII KAN SV40-3×GFP and R2D2 vectors, W. Yang for the spl mutant, Y. Qin for the pKNU::KNU-VENUS vector and seed, G. Tang for the STTM160/160-48 vector, and L. Colombo for pPIN1::PIN1-GFP spl and pin1-5 seeds. This work was supported by the US National Science Foundation (NSF)-Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF) research grant to D.Z. (IOS-1322796) and T.A. (2012756). D.Z. also gratefully acknowledges supports of the Shaw Scientist Award from the Greater Milwaukee Foundation, USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA, 2022-67013-36294), the UWM Discovery and Innovation Grant, the Bradley Catalyst Award from the UWM Research Foundation, and WiSys and UW System Applied Research Funding Programs.

Source data

Author contributions

J.H. and D.Z. conceived ideas and designed experiments. J.H., L.Z., S.M., B.R.G., V.X., and H.A.O. performed experiments. J.H., J.F., and D.Z. analyzed data. J.H., T.A., J.F., and D.Z. wrote the manuscript with contributions from other authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-34723-6.

References

- 1.Bowman JL, Sakakibara K, Furumizu C, Dierschke T. Evolution in the cycles of life. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2016;50:133–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-035227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang WC, Shi DQ, Chen YH. Female gametophyte development in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010;61:89–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt A, Schmid MW, Grossniklaus U. Plant germline formation: common concepts and developmental flexibility in sexual and asexual reproduction. Development. 2015;142:229–241. doi: 10.1242/dev.102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinto SC, Mendes MA, Coimbra S, Tucker MR. Revisiting the female germline and its expanding toolbox. Trends Plant Sci. 2019;24:455–467. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao L, et al. Arabidopsis ICK/KRP cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors function to ensure the formation of one megaspore mother cell and one functional megaspore per ovule. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao XA, et al. RETINOBLASTOMA RELATED1 mediates germline entry in Arabidopsis. Science. 2017;356:eaaf6532. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nonomura KI, et al. The MSP1 gene is necessary to restrict the number of cells entering into male and female sporogenesis and to initiate anther wall formation in rice. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1728–1739. doi: 10.1105/tpc.012401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao XA, et al. OsTDL1A binds to the LRR domain of rice receptor kinase MSP1, and is required to limit sporocyte numbers. Plant J. 2008;54:375–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang CJ, et al. Maize multiple archesporial cells 1 (mac1), an ortholog of rice TDL1A, modulates cell proliferation and identity in early anther development. Development. 2012;139:2594–2603. doi: 10.1242/dev.077891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao LH, et al. KLU suppresses megasporocyte cell fate through SWR1-mediated activation of WRKY28 expression in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E526–E535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716054115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su ZX, et al. The THO complex non-cell-autonomously represses female germline specification through the TAS3-ARF3 module. Curr. Biol. 2017;27:1597–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su Z, et al. Regulation of female germline specification via small RNA mobility in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2020;32:2842–2854. doi: 10.1105/tpc.20.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh M, et al. Production of viable gametes without meiosis in maize deficient for an ARGONAUTE protein. Plant Cell. 2011;23:443–458. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.079020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendes MA, et al. The RNA dependent DNA methylation pathway is required to restrict SPOROCYTELESS/NOZZLE expression to specify a single female germ cell precursor in Arabidopsis. Development. 2020;147:dev194274. doi: 10.1242/dev.194274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiefthaler U, et al. Molecular analysis of NOZZLE, a gene involved in pattern formation and early sporogenesis during sex organ development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:11664–11669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olmedo-Monfil V, et al. Control of female gamete formation by a small RNA pathway in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2010;464:628–632. doi: 10.1038/nature08828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang WC, Ye D, Xu J, Sundaresan V. The SPOROCYTELESS gene of Arabidopsis is required for initiation of sporogenesis and encodes a novel nuclear protein. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2108–2117. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borges F, Martienssen RA. The expanding world of small RNAs in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015;16:727–741. doi: 10.1038/nrm4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrella R, et al. The emerging role of small RNAs in ovule development, a kind of magic. Plant Reprod. 2021;34:335–351. doi: 10.1007/s00497-021-00421-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang T, Zheng B. Epigenetic regulation of megaspore mother cell formation. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:826871. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.826871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aslam M, Fakher B, Qin Y. Big role of small RNAs in female gametophyte development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:1979. doi: 10.3390/ijms23041979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt A, et al. Transcriptome analysis of the Arabidopsis megaspore mother cell uncovers the importance of RNA helicases for plant germline development. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y. Essential roles of local auxin biosynthesis in plant development and in adaptation to environmental changes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018;69:417–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grieneisen VA, et al. Auxin transport is sufficient to generate a maximum and gradient guiding root growth. Nature. 2007;449:1008–1013. doi: 10.1038/nature06215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adamowski M, Friml J. PIN-dependent auxin transport: action, regulation, and evolution. Plant Cell. 2015;27:20–32. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.134874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brumos J, et al. Local auxin biosynthesis is a key regulator of plant development. Dev. Cell. 2018;47:306–318. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bargmann BO, et al. A map of cell type-specific auxin responses. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2013;9:688. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salehin M, Bagchi R, Estelle M. SCFTIR1/AFB-based auxin perception: mechanism and role in plant growth and development. Plant Cell. 2015;27:9–19. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.133744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Israeli A, Reed JW, Ori N. Genetic dissection of the auxin response network. Nat. Plants. 2020;6:1082–1090. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0739-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramos Baez R, Nemhauser JL. Expansion and innovation in auxin signaling: where do we grow from here? Development. 2021;148:dev187120. doi: 10.1242/dev.187120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smetana O, et al. High levels of auxin signalling define the stem-cell organizer of the vascular cambium. Nature. 2019;565:485–489. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0837-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu XD, et al. The role of floral organs in carpels, an Arabidopsis loss-of-function mutation in MicroRNA160a, in organogenesis and the mechanism regulating its expression. Plant J. 2010;62:416–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mallory AC, Bartel DP, Bartel B. MicroRNA-directed regulation of Arabidopsis AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR17 is essential for proper development and modulates expression of early auxin response genes. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1360–1375. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang JW, et al. Control of root cap formation by microRNA-targeted auxin response factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2204–2216. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu PP, et al. Repression of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR10 by microRNA160 is critical for seed germination and post-germination stages. Plant J. 2007;52:133–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneitz K, Hulskamp M, Pruitt RE. Wild-type ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana: a light microscope study of cleared whole-mount tissue. Plant J. 1995;7:731–749. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christensen CA, King EJ, Jordan JR, Drews GN. Megagametogenesis in Arabidopsis wild type and the Gf mutant. Sex. Plant Reprod. 1997;10:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plotnikova A, et al. MicroRNA dynamics and functions during Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Plant Cell. 2019;31:2929–2946. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grefen C, et al. A ubiquitin-10 promoter-based vector set for fluorescent protein tagging facilitates temporal stability and native protein distribution in transient and stable expression studies. Plant J. 2010;64:355–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan J, et al. Effective small RNA destruction by the expression of a short tandem target mimic in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:415–427. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.094144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moubayidin L, Ostergaard L. Dynamic control of auxin distribution imposes a bilateral-to-radial symmetry switch during gynoecium development. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:2743–2748. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abas L, et al. Naphthylphthalamic acid associates with and inhibits PIN auxin transporters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:e2020857118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2020857118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1790–1799. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang J, et al. Ectopic expression of TAPETUM DETERMINANT1 affects ovule development in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:1311–1326. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friml J, et al. Efflux-dependent auxin gradients establish the apical-basal axis of Arabidopsis. Nature. 2003;426:147–153. doi: 10.1038/nature02085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liao CY, et al. Reporters for sensitive and quantitative measurement of auxin response. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:207–210. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benkova E, et al. Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell. 2003;115:591–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bencivenga S, Simonini S, Benkova E, Colombo L. The transcription factors BEL1 and SPL are required for cytokinin and auxin signaling during ovule development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2886–2897. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.100164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li LC, et al. SPOROCYTELESS modulates YUCCA expression to regulate the development of lateral organs in Arabidopsis. N. Phytol. 2008;179:751–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng Y, et al. Auxin guides germ-cell specification in Arabidopsis anthers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:e2101492118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2101492118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tucker MR, et al. Sporophytic ovule tissues modulate the initiation and progression of apomixis in Hieracium. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:3229–3241. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang D, et al. Identification of transcription-factor genes expressed in the Arabidopsis female gametophyte. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schlereth A, et al. MONOPTEROS controls embryonic root initiation by regulating a mobile transcription factor. Nature. 2010;464:913–916. doi: 10.1038/nature08836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang ZP, et al. Egg cell-specific promoter-controlled CRISPR/Cas9 efficiently generates homozygous mutants for multiple target genes in Arabidopsis in a single generation. Genome Biol. 2015;16:144. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0715-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakagawa T, et al. Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2007;104:34–41. doi: 10.1263/jbb.104.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamaguchi N, et al. A molecular framework for auxin-mediated initiation of flower primordia. Dev. Cell. 2013;24:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hejatko J, et al. In situ hybridization technique for mRNA detection in whole mount Arabidopsis samples. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1939–1946. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Javelle M, Timmermans MCP. In situ localization of small RNAs in plants by using LNA probes. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:533–541. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang J, et al. Control of anther cell differentiation by the small protein ligand TPD1 and its receptor EMS1 in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang J, et al. Carbonic anhydrases function in anther cell differentiation downstream of the receptor-like kinase EMS1. Plant Cell. 2017;29:1335–1356. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Escobar-Guzman R, Rodriguez-Leal D, Vielle-Calzada JP, Ronceret A. Whole-mount immunolocalization to study female meiosis in Arabidopsis. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:1535–1542. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu CM, Meinke DW. The titan mutants of Arabidopsis are disrupted in mitosis and cell cycle control during seed development. Plant J. 1998;16:21–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao DZ, Wang GF, Speal B, Ma H. The EXCESS MICROSPOROCYTES1 gene encodes a putative leucine-rich repeat receptor protein kinase that controls somatic and reproductive cell fates in the Arabidopsis anther. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2021–2031. doi: 10.1101/gad.997902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shaner NC, et al. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:1567–1572. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nagai T, et al. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.