Abstract

This preregistered systematic review examined the peer-reviewed scientific literature to determine the effect of hearing aids (HAs) on static and dynamic balance in adults with Hearing Impairment (HI). A search of the English language literature in seven academic databases identified 909 relevant articles published prior to July 2021. Ten articles contained studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review. Seven studies had measured static balance with five reporting improvements and one reporting no changes in balance with HA use. Two studies had measured dynamic balance with both reporting no changes with HA use. One study had measured both dynamic and static balance and reported no changes with HA use. For adults with HI, the evidence was equivocal that amplification from HAs improves balance. High quality studies investigating the effect of HAs on balance in adults with HI are needed given this field is likely to develop in response to the growing population of adults with hearing and balance impairment worldwide.

Keywords: hearing aids, hearing impairment, balance, postural stability, vestibular impairment

Introduction

The generic term “balance” describes the ability to maintain a stable and specific orientation in relation to the immediate environment with static balance describing the ability to hold the body in a specific position and posture and dynamic balance describing the ability to maintain balance when the body is in motion. Balance is achieved through the complex integration of multiple sensory inputs (Melzer et al., 2001) including vision (Ray et al., 2008), somatosensation (Simoneau et al., 1995), vestibular inputs (Shumway-Cook & Horak, 1986), and the more recently suggested input of hearing (Campos et al., 2018). The similarly generic term “balance problems” describes the falls, postural instability, and/or vestibular impairment that can result from a failure in one or more sensory inputs to balance and/or their integration. Balance problems are prevalent in both general and clinical populations (Murdin & Schilder, 2015) with management options dependent on aetiology. This review considers the use of hearing aids (HAs) to manage balance problems in adults with Hearing Impairment (HI).

The association of balance problems with HI in adults stems from their high rates of co-occurrence (Agrawal et al., 2012; Berge et al., 2019; Murdin & Schilder, 2015; Zuniga et al., 2012) and suggestions that poorer hearing thresholds could be associated with increased risk of postural instability (Berge et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2018). The latter includes reports of the chance of falling increasing by 2.39 in the presence of HI (Jiam et al., 2016) and by 1.4 with every 10 dB increase in HI (Lin & Ferrucci, 2012).

The co-occurrence of balance problems and HI could be due to several factors, both direct and indirect (Berge et al., 2019). Direct factors include the proximity and shared anatomy and physiology of the vestibular and hearing end organs in the inner ear and their associated innervation via the VIIIth cranial nerve and brainstem (Berge et al., 2019; Santos et al., 2015). Such proximity increases the probability of an impairment in one system affecting the other system (e.g., Meniere's disease, acoustic neuromas, and vestibular labyrinthitis). Indirect factors include processes that can simultaneously affect both balance and hearing such as the non-pathological process of ageing (Agmon et al., 2017; de Almeida Ciquinato et al., 2020) or pathological processes such as diabetes (Frisina et al., 2006), thyroid problems (Bellman et al., 1996), and oto-vestibulotoxic medication (Chen et al., 2007).

The suggestion that HAs could be used to improve balance in adults with HI stems from two main factors. The first factor argues that hearing could serve as a fourth sensory input in the maintenance of balance (after vision, somatosensation and input from the vestibular system) (Campos et al., 2018; Gandemer et al., 2017). This argument proposes that listeners use monaural and binaural cues to create three-dimensional, spatial hearing maps of the surrounding environment (Campos et al., 2018; Gandemer et al., 2017). Listeners then use these maps to locate themselves relative to static and dynamically changing sound sources in their environment (Eddins & Hall, 2010). Support for this hypothesis can be drawn from studies showing adults with normal hearing can improve their balance when given access to auditory cues that are stationary (Gandemer et al., 2017; Zhong & Yost, 2013) or dynamic (Deviterne et al., 2005; Tanaka et al., 2001). The second factor argues that hearing competes with balance (and other functions) for limited cognitive resources in the brain (Lau et al., 2016). This argument proposes that the presence of unmanaged HI could see the listener needing to draw on cognitive resources to support hearing over balance. This competition could result in listeners allocating insufficient cognitive resources to maintain balance (Hofer et al., 2003).

Given the two factors described above, it is possible that HAs could improve balance in adults with HI by enhancing access to auditory cues and/or reducing the need for cognitive resources. These possibilities have recently been the target of at least two systematic reviews (Borsetto et al., 2021 and Ernst et al., 2021). Borsetto et al. (2021) reviewed the influence of HAs on balance control in adults with mild to severe sensorineural HI and concluded that HAs could improve balance in adults with HI in certain conditions. Ernst et al. (2021) reviewed the impact of diagnosed and treated HI (including HAs and cochlear implants) on balance and the risk of falls and concluded that hearing amplification is most likely to improve balance in elderly. Despite both reviews contributing significantly to our knowledge of HAs and balance, both reviews lacked a quality assessment of the included studies, a detailed description of the audiological data presented in the reviewed studies, and registration with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. A third review by Carpenter and Campos (2020) should also be considered for its claim that any conclusion on the effect of HAs on balance is premature. Whilst also contributing to our knowledge of HAs and balance, this review's use of strict inclusion criteria limited its review of HAs and balance to three studies that had used well-defined posturography measures to assess balance in adults with hearing loss with and without their HAs (Maheu et al., 2019; Negahban et al., 2017; Vitkovic et al., 2016; all of which are included in the current review). The remaining studies reviewed by Carpenter and Campos (2020) investigated balance in adults with cochlear implants and adults with normal hearing that had been suppressed.

In this registered systematic review, we examine the peer-reviewed scientific literature to determine the efficacy of HAs on static and dynamic balance in adults with HI. We include details of quality assessments of selected studies and present detailed hearing and balance data extracted from the studies. This review sought to answer the following research question presented in the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) format of Needleman (2003): In adults with HI (P), does amplification with HAs (I) improve static and dynamic balance (O) compared to no amplification (C).

Methods

The protocol and methods used in this review were registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number CRD 42020194035, 5th September 2020). The review method followed the guidelines established by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-P) (Shamseer et al., 2015).

Search Strategy

An extensive, computer-based, systematic search of the literature was completed using the following databases: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane library (including Central), Medline, and CINAHL. The search was originally conducted in May 2020 and repeated in October 2021 in order to include any papers published since the original search. Reference lists and citation tracking were screened to identify any additional relevant studies, and Google Scholar was used to identify further gray literature.

The search strategy was developed and tested through an iterative process by an experienced medical information librarian in consultation with the review team. The database search terms were: HI OR hearing loss OR presbycusis OR hard of hearing AND hearing aid* OR listening device OR hearing device OR auditory intervention OR auditory amplification AND postural stability OR postural balance OR balance OR dizziness OR vertigo OR gait OR posture OR dynamic posture OR static posture OR vestibular impairment* OR vestibular disorder*. There were no date restrictions on any of the searches. The full search strategy is reported in the supplementary material.

Study Inclusion Criteria

The study inclusion criteria were based on the PICO format (Needleman, 2003) of the research question (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Inclusion Criteria Defined in Terms of the PICO Question.

| P (Population) | Adults aged ≥ 18 years with any type of hearing impairment ≥ 20dBHL. |

| I (Intervention) | At least one group of participants fitted with HAs (unilateral or bilateral). |

| C (comparison) | Either a within-group comparison (HAs on vs off) or a between-group comparison (aided group vs unaided group). |

| O (outcome) | Any measure of balance, postural stability, gait, or vestibular function. |

Note: HA = Hearing aids.

Study designs that were considered for this review were Randomised Control Trials (RCTs), cross-sectional studies, retrospective studies, case reports, and observational studies. Systematic reviews, single case reports, clinical handbooks, books, and studies with non-human participants were excluded from the review. Studies were also excluded if the outcome measure of balance was limited to self-reports of falls only, or if the report was written in a language other than English.

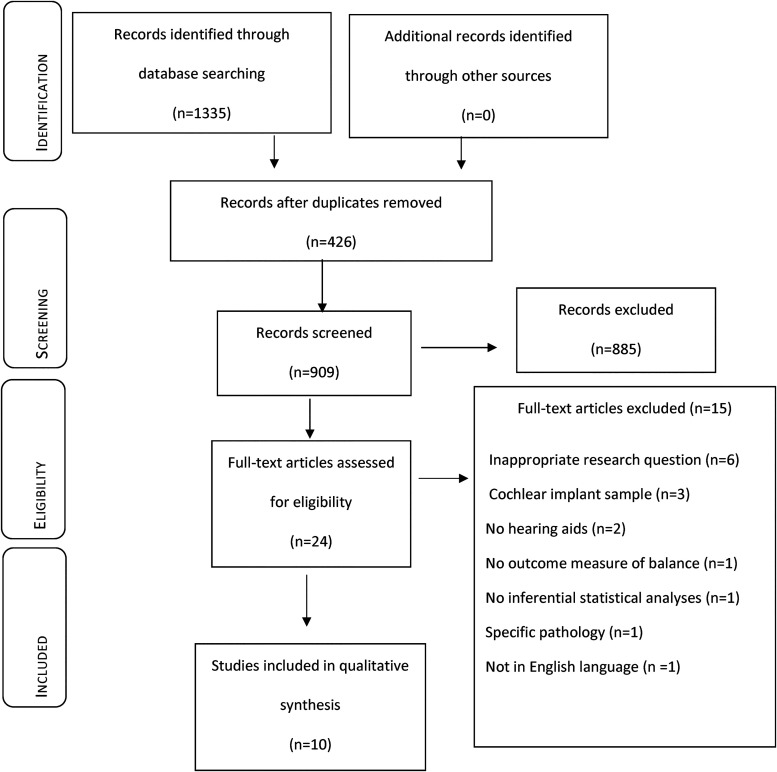

Study Selection and Inter-Rater Reliability

A standardized data collection form was developed in Covidence (www.covidence.org). Detailed guidance notes were developed and piloted by the first author and shared with two other reviewers to ensure consistency. The search strategy (Figure 1, adapted from PRISMA flowchart [Moher et al., 2009]) initially yielded a total of 1335 articles of which 426 were duplicates. The title and abstracts of the 909 identified articles were screened independently by two reviewers for inclusion using the study selection criteria. The conflict error between the two reviewers during this title and abstract screening round was <3%. Any conflicts were resolved by discussion between the reviewers and with the other authors where needed. A total of 24 articles met the eligibility criteria for a full review by two reviewers against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, of which 10 met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the present systematic review. The conflict error between the two reviewers during this full article review round was 8.3% (2 articles). These conflicts were resolved by discussion between the reviewers and the other authors.

Figure 1.

Selection of studies for the systematic review based on preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The first author used a checklist of items relevant to the present study's inclusion criteria to extract elements about the study design and relevant results from the ten articles included in the review (Table 2). Data was included from participants with HAs and participants from other groups if that group's performance on a balance task was compared to the HA group. The reliability of the data extraction was checked by the co-authors and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. A meta-analysis of the included data was not possible due to the small number of studies identified and the heterogeneity of study design and balance outcome measures. The extracted data were analyzed using a narrative synthesis which relies primarily on the use of words and text to summarize and explain the findings of the synthesis (Popay et al., 2006).

Table 2.

Summary of the ten Studies Included in the Systematic Review. the First Seven Studies Measured Static Balance Only, the Eighth Study Measured Both Dynamic and Static Balance and the Final two Studies Measured Dynamic Balance. the Final two Columns Provide a Simple Indication of the Overall Finding of Each Study Regarding HAs Affecting Static (S) or Dynamic (D) Balance in Adults with Hearing Impairment, Where “Yes” Indicates a Positive Finding (Improvements in Balance with HAs) and “No” Indicates a Negative Finding (no Improvements in Balance with HAs).

| Study & research design | Participants | HAs | Methods | Effect of HAs on static or dynamic balance | S | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rumalla et al. (2015) Single group case series (pretest-posttest). |

|

|

|

|

Yes | |

| Ibrahim et al. (2019) Single group case series (pretest-posttest). |

|

|

|

|

Yes | |

| Negahban et al. (2017) Two group case series (one group pretest-posttest & one group posttest only). |

|

|

|

|

Yes | |

| Maheu et al. (2019) Two group case series (pretest-posttest).* |

|

|

|

|

Yes | |

| Ninomiya et al. (2021) Two group case series (pretest-posttest).* |

|

|

|

|

Yes | |

| Vitkovic et al. (2016) Single group case series (pretest-posttest). |

|

|

|

|

Yes | |

| McDaniel et al. (2018) Single group case series (pretest-posttest). |

|

|

|

|

No | |

| Lacerda et al. (2012) Single group case series (pretest-posttest). |

|

|

|

|

No | No |

| Weaver et al. (2017) Single group case series (pretest-posttest). |

|

|

|

|

No | |

| Kowalewski et al. (2018) Single group case series (pretest-posttest).* |

|

|

|

|

No |

Note. All values following the ± are standard deviations; *these studies included adults with normal hearing but their results are not considered here; 4fa = 4-fequency average; ABC scale = Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale (Powell & Myers, 1995); AC = air conduction; AP = anterior-posterior; BBN = broad band noise; BBS = Berg Balance Scale (Berg et al., 1992); BKB-SIN = Bamford Kowal-Bench Speech-in-Noise test (Bamford & Bench, 1979); BTE = Behind the ear; CIC = Completely In the canal; CoP = Centre of Pressure; FES-I = Falls Efficacy Scale-International (Yardley et al., 2005), where participants answer questions about fear of falling; HA = Hearing aids; HI = Hearing impairment; HL = Hearing Level; ITC = In the canal; ITE = In the ear; kHz = kilohertz; LE = left ear; Max = maximum; mCTSIB = modified Clinical Test of Sensory Interaction in Balance (Cohen et al., 1993) that measures CoP sway area and velocity in 4 static conditions: 1) firm surface, eyes open, 2) firm surface, eyes closed, 3) foam surface, eyes open, and 4) foam surface, eyes closed, each held for a maximum of 30 s; ML = mediolateral; RE = right ear; RITE = Receiver In the ear; Rof = Romberg on foam (Galán-Mercant & Cuesta-Vargas, 2014), where participants stand on a foam surface with eyes open; SNHL = sensorineural hearing loss; SOT = Sensory Organization Test (Ford-Smith et al., 1995); SD = standard deviation; SPL = sound pressure level; TST = a tandem stance test (Maki et al., 1994), where participants stand placing one foot in front of the other, heel to toe; TUG = Timed Up and Go test (Schoppen et al., 1999), where participants stand up from a seated position, walk for 3m at a comfortable pace, and sit from a standing position; WN = white noise.

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

Each study was assessed by two reviewers using the Downs and Black (1998) quality checklist. This checklist's high inter-rater reliability (Deeks et al., 2003) and consistency with 18 other recommended quality assessment tools (West et al., 2002) has seen it used in systematic reviews including in the field of audiology (Maidment et al., 2018). The checklist consists of 27 questions relating to the quality of reporting, external validity, internal validity, and statistical power of a study. Each criterion is scored “0” if not evident (or unable to be determined) or “1” if evident. The exception is criterion 5 (description of principle confounders), which is scored “0” if not evident (or unable to be determined), “1” if partially evident, or “2” if evident. The final score for the checklist categorizes a study into one of four quality levels: excellent (scores of 26–28), good (scores of 20–25), fair (scores of 15–19), or poor (scores ≤ 14) (Hooper et al., 2008).

Results

Of the 10 studies included in this review, eight used a single group case series (pretest-posttest) and two used a two group case series research design in which objective measures were obtained in laboratory settings from participants completing balance tasks with and without HAs (Table 2). Seven studies measured static balance, two measured dynamic balance, and one measured both static and dynamic balance of participants. Measures of static balance were performed while the participant was standing still. This often saw the measurement of slow drifts and immediate corrections as the participant attempted to preserve the body's center of mass within its base of support (Collins & De Luca, 1995). Measures of dynamic balance were performed while the participant was moving. This saw a range of measures performed while participants completed different types of motion (Baker et al., 2021). Two examples (of many) include the use of inertial sensors to measure changes in center of pressure when walking a fixed distance, and the measurement of changes in the number of steps required to regain balance while walking forward with acceleration on a dual belt treadmill.

Two studies (Maheu et al., 2019 and Negahban et al., 2017) included between-groups measures. Negahban et al. (2017) compared the postural stability of a group of participants with HI who wore HAs to that of a group of participants with HI who did not wear HAs. Maheu et al. (2019) compared the postural stability of a group of participants with confirmed hearing and vestibular impairment who wore HAs to a group with confirmed HI but no vestibular impairment who wore HAs. Eight studies provided no information regarding the details of the HAs and their settings for their participants. Of the two studies that did offer some details on the HAs, Rumalla et al. (2015) verified the output of the HAs worn by participants by means of insertion gain and Negahban et al. (2017) reported the participants’ average aided thresholds.

Participants

One hundred and ninety-nine participants with HI were evaluated in the ten studies included in the review (ranging from 9 to 47 per study). The degree and type of HI varied both within and between studies with degree and type of impairment not reported in Kowalewski et al. (2018), Rumalla et al. (2015), and Weaver et al. (2017), moderate impairment (type not specified) reported in Ninomiya et al. (2021), mild sloping to severe impairment (type not specified) reported in Negahban et al. (2017) and McDaniel et al. (2018), and moderate to profound sensorineural impairment reported in Ibrahim et al. (2019), Lacerda et al. (2012), Maheu et al. (2019), and Vitkovic et al. (2016).

The 10 reviewed studies showed considerable variability in the reported length of participants’ HA use and experience. Five studies included participants with at least 3 months experience with HAs (Ibrahim et al., 2019; McDaniel et al., 2018; Negahban et al., 2017; Rumalla et al., 2015; Weaver et al., 2017). Ninomiya et al. (2021) included participants with at least one year of experience with HAs. Three studies reported that their participants were experienced HA users but did not specify the duration of use (Kowalewski et al., 2018; Maheu et al., 2019; Vitkovic et al., 2016). Lacerda et al. (2012) assessed the balance of their participants pre- and 4 months post-fitting with HAs. Negahban et al. (2017) was the only study to report any correlation results between the time of HA acquisition and balance measures in their participants. Six studies indicated that their participants wore bilateral HAs during the trial (Maheu et al., 2019; McDaniel et al., 2018; Negahban et al., 2017; Ninomiya et al., 2021; Rumalla et al., 2015; Weaver et al., 2017), one study reported both unilateral and bilateral HA use (Vitkovic et al., 2016), and the remaining studies did not specify the laterality of the participants’ HA fitting (Ibrahim et al., 2019; Kowalewski et al., 2018; Lacerda et al., 2012). Vitkovic et al. (2016) was the only study to report the types of the HAs used by their participants. Further information regarding the HA features, programming algorithms and average daily use were not reported by any of the studies.

Static Balance Outcome Measures

Two studies (Ibrahim et al., 2019; Rumalla et al., 2015) used the Romberg on foam test and the tandem stance test (TST) to examine maximum hold time up to 30 s to measure the benefits of HAs on static balance. In both studies, the static balance tests were performed with and without HAs. Ibrahim et al. (2019) reported a significant (p < 0.05 or better) increase in standing time on the Romberg on foam test for eight out of nine participants with HAs (mean improvement 4.4 s, with one participant showing a ceiling effect in both HA conditions) and on the TST (mean improvement 3.36 s) for all nine participants. Rumalla et al. (2015) reported a significant (p < 0.005) increase in standing time on the Romberg on foam test in 10 out of 14 participants with HAs (mean improvement 8.5 s, with four participants showing a ceiling effect in both HA conditions), and a significant increase in standing time with HAs on the TST in all 14 participants (mean improvement 5.3 s). Rumalla et al. (2015) found no significant (p > 0.05) correlation between the audiometric gain (mean = 12.75 dB SPL) of HAs and the improvements reported on both tests of static balance.

Four studies (Ninomiya et al., 2021; Maheu et al., 2019; Negahban et al., 2017; Vitkovic et al., 2016) recorded Centre of Pressure (CoP) excursion measures (sway area, sway velocity, mean velocity and/or path length) to assess the postural stability of participants with and without HAs while standing in four different static conditions on force platforms or load cells. Ninomiya et al. (2021) assessed their participants using posturography and reported significant (p < 0.05) reductions in the total path area, maximum COP displacement in AP direction, averaged sway velocity in both AP and ML in the presence of an external auditory sound when HAs were used. Maheu et al. (2019) reported that HAs significantly (p < 0.005) reduced somatosensory reliance (measured by comparing balance standing with eyes open on foam versus eyes open on a firm surface, and without auditory input versus with auditory input) but not visual reliance (measured by comparing balance standing with eyes closed on firm surface versus eyes open on a firm surface, and without auditory input versus with auditory input) for maintaining balance in 10 participants with hearing and vestibular impairment compared to eight participants with HI only. Maheu et al. (2019) suggested the benefit of HAs for the participants with hearing and vestibular impairment stemmed from greater weighting of auditory cues for maintaining balance to compensate for the loss of somatosensory cues. Negahban et al. (2017) reported significant (p < 0.0001) reduced sway in both the anterior-posterior and mediolateral directions in participants with HAs on for the eyes open on foam condition and reported significantly (p < 0.0001) reduced sway in both the anterior-posterior and mediolateral directions for the aided group when compared to the unaided group. Vitkovic et al. (2016) used the modified Clinical Test of Sensory Interaction in Balance (mCTSIB) to report a significant (p < 0.05) interaction between HA (HA vs no HAs) and acoustic environment (sound vs no sound) conditions. This interaction showed that wearing a HA in the presence of external sound resulted in less sway (better postural stability) than with no external sound.

One study (McDaniel et al., 2018) used the Sensory Organization Test (SOT) to measure the postural stability of a group of adults with HI and HAs. The SOT involves six static conditions of which four resemble the static conditions used by Vitkovic et al. (2016), Negahban et al. (2017) and Maheu et al. (2019). However, McDaniel et al. (2018) failed to find any significant (p > 0.05) differences in the SOT composite score of their participants with HAs versus without HAs.

Dynamic Balance Outcome Measures

Two studies by Kowalewski et al. (2018) and Weaver et al. (2017) employed different dynamic measures and showed no significant (p > 0.05) improvements in postural stability with HAs.

The first study, Kowalewski et al. (2018), measured the number of steps required to regain balance (reactive balance) while standing on a dual belt treadmill in three balance and auditory conditions in a group of older adults with HI and HAs. The authors reported no significant (p > 0.05) difference in the number of steps taken (reactive balance) for the hearing-impaired group when wearing HAs compared to not wearing HAs.

The second study, Weaver et al. (2017), used walking tests to assess the dynamic balance of a group of adults with HI and HAs while HAs were worn and not worn. The authors did not report any significant (p > 0.05) differences in the walking speed, stride length variability, swing time variability, double support phase or time needed to complete the Timed Up and Go test for participants wearing HAs compared to not wearing HAs.

Static and Dynamic Balance Outcome Measures

Lacerda et al. (2012) used the Berg Balance Scale (BBS), a clinical test that measures functional balance by scoring the performance of 14 dynamic and static tasks. A group of older adults with HI were fitted with HAs and their balance was assessed before and after 4 months of using HAs. The authors found no significant differences between the BBS scores before (50.6 ± 4.9) and after (51 ± 5) HA use, with scores remaining within normal limits on both occasions.

Quality of Evidence

Table 3 shows the quality assessment of the ten studies reviewed. All studies were graded as “Fair” except for McDaniel et al. (2018) and Ninomiya et al. (2021), which were graded as “Poor”. All studies returned higher scores for quality of reporting than for external and internal validity. Statistical power was not reported in any of the studies.

Table 3.

Quality Measures of Individual Studies Assessed According to the Downs and Black (1998) checklist.

| Study | Quality of reporting (Q1–10). Maximum = 11 | External validity (Q11–13). Maximum = 3 | Internal validity (Q14–26). Maximum = 13 | Statistical power (Q27). Maximum = 1 | Overall quality. Maximum = 28 | Quality rating (Hooper et al., 2008) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rumalla et al. (2015) | 9 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 16 | Fair |

| Ibrahim et al. (2019) | 8 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 17 | Fair |

| Negahban et al. (2017) | 8 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 16 | Fair |

| Maheu et al. (2019) | 7 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 15 | Fair |

| Ninomiya et al. (2021) | 7 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 14 | Poor |

| Vitkovic et al. (2016) | 9 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 18 | Fair |

| McDaniel et al. (2018) | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 12 | Poor |

| Lacerda et al. (2012) | 7 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 15 | Fair |

| Weaver et al. (2017) | 7 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 15 | Fair |

| Kowalewski et al. (2018) | 7 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 15 | Fair |

Problems with both external and internal validity were noted for all studies. Problems with the external validity of most of the included articles were related to the lack of representativeness of samples to the general population; no studies reported how the samples were selected, nor did they report sample proportions relative to the source population. Problems with internal validity were related to selection bias resulting from the absence of control groups, lack of blinding of participants and assessors, poor control for confounding variables (e.g., HA features, use duration and objective measures of gain, participants’ age, and aetiologies and types of HI) and finally the lack of inclusion of participants with balance problems.

Discussion

The findings of this systematic review indicate that for adults with HI, the evidence is equivocal that amplification with HAs improves static and dynamic balance compared to no amplification or to an unaided control group. Of the seven studies that measured static balance, six reported improvements (Ibrahim et al., 2019; Maheu et al., 2019; Negahban et al., 2017; Ninomiya et al., 2021; Rumalla et al., 2015; Vitkovic et al., 2016) and one reported no change in balance (McDaniel et al., 2018) with HA use. Of the two studies that measured dynamic balance, both reported no change in balance with HA use (Kowalewski et al., 2018; Weaver et al., 2017). The one study that measured both dynamic and static balance (Lacerda et al., 2012) reported no improvements when HAs were used.

Before discussing the potential effects of HAs on static versus dynamic balance, the eight limitations common to most of the studies reviewed must be noted. These limitations were: 1) the poor to fair quality ratings with 9/10 studies being single group case series lacking the control groups needed to attribute changes in balance to hearing aid use (some of these studies include control groups that could not be used to attribute changes in balance to hearing aid use, e.g., the use of control groups consisting of adults with normal hearing thresholds); 2) the use of participants with no self-reported or measured balance problems with 8/10 studies at risk of ceiling effects in their balance measures; 3) the lack of detail on HA type, fitting and usage, with some studies reporting laterality of fit, gain, and duration of use data but no studies reporting fitting algorithms, features or daily usage data; 4) the lack of detail on participant HI, which ranged from incomplete descriptions of type, degree and shape of HI to descriptions of hearing loss as simply being present or absent; 5) the variability in external sounds used, which ranged from no external sound to sounds of different acoustic and linguistic properties (e.g., stochastic noise versus sentences in multi-talker babble); 6) the small and variable sample sizes used in all studies; 7) the use of laboratory conditions in all studies rather than attempting to recreate real-world conditions where the participants would often need to maintain their balance; and 8) the variety of apparati used (e.g., force platforms, Wii Balance Board) to complete a variety of clinical and laboratory measures of balance (e.g., sway area, velocity, time to overall balance).

Hearing Aids and Static Balance

The reported improvements in static balance with HAs (Ibrahim et al., 2019; Maheu et al., 2019; Negahban et al., 2017; Ninomiya et al., 2021; Rumalla et al., 2015; Vitkovic et al., 2016) were twofold. The first was an increased ability to maintain posture for longer periods in the presence of external sound (Ibrahim et al., 2019; Rumalla et al., 2015). The second was significant reductions in body sway area, velocity, or path length in both the anterior-posterior and/or mediolateral directions in the presence of external sound with HAs (Maheu et al., 2019; Ninomiya et al., 2021; Vitkovic et al., 2016) or in the absence of external sound with HAs (Negahban et al., 2017). These reports were countered by McDaniel et al. (2018) who reported no change in sway area when their participants wore HAs in the presence of external sound, and Lacerda et al. (2012) who found no change in five static balance measures in their participants before and after being fitted with HAs.

The improvements in static balance with HAs were most reported in the two conditions most assessed in the reviewed studies. The first condition was maintaining balance when standing on a foam surface (e.g., Romberg on foam and standing on foam with eyes open or eyes closed on the mCTSIB or similar test batteries), which is thought to particularly challenge somatosensory input. The second condition was placing one foot in front of the other (TST), which is thought to challenge balance by narrowing base of support and impairing lateral stability. In all but one of the occasions (Negahban et al., 2017) using these test conditions, the benefits of HAs were only observed in the presence of external noise and not in quiet. One interpretation of this result is the amplification of the external noise provided by the HAs allowed adults with HI to better access the spatial cues in the external sound that can help to orientate the body in space. A second interpretation extends the first by suggesting these additional auditory cues augmented the somatosensory cues that had been compromised by the static balance task itself. Such augmentation could also be interpreted as a shift in the relative weightings given to the available cues when trying to maintain static balance. This shift could be to lessen the weighting given to somatosensory cues as they become less useful, to increasing the weighting given to auditory cues as they become more useful, for maintaining balance when standing on foam or placing one foot in front of the other. This second interpretation offers some support to Maheu et al.’s (2019) conclusion that HAs can decrease the reliance on somatosensory input for balance in adults with HI (although Maheu’s finding was for participants with hearing and vestibular impairments and not HI only).

Hearing Aids and Dynamic Balance

The absence of improvements in dynamic balance with HAs in the three studies investigating dynamic balance in this review (Kowalewski et al., 2018; Lacerda et al., 2012; Weaver et al., 2017) was limited by the small number of studies and the diverse range of dynamic balance measures used. One interpretation of this result could be that in adults with HI, HAs do not benefit dynamic balance as measured by the BBS (Lacerda et al., 2012), gait (Weaver et al., 2017), or reactive balance (Kowalewski et al., 2018). Another interpretation could be that relative to other sensory inputs, hearing was not essential for maintaining dynamic balance in the tasks assessed in these studies. For example, the action of sitting-to-standing in the BBS would be more likely to depend on somatosensory, visual, and vestibular inputs than on auditory input, particularly considering most adults in the reviewed studies presented with no balance problems. More ecologically valid assessments of dynamic balance could be needed to detect any benefit of HAs on dynamic balance. Such assessments may need to depend more on auditory input for maintaining dynamic balance and may need to be applied to adults with both HI and balance problems before any potential benefit of HAs on dynamic balance can be fully determined.

Hearing Aids and Balance – General Discussion

A key challenge to investigating the effect of HAs on balance is the general nature of the terms “hearing impairment” and “balance”. HI can encompass a wide range of types, degrees, shapes, and causes, each affecting hearing differently in different adults. Similarly, balance is a complex process that comprises many systems (visual, somatosensory, and vestibular) with balance problems originating from one, some or all these systems even within a single adult. When choosing a research question in this field, it is critical to specify the nature of the HI, the HAs, the type of balance, and the balance impairment being investigated.

When considering HAs and balance, it also seems reasonable to expect that HAs would mostly benefit balance in adults with balance problems directly or indirectly related to a coexisting HI. This emphasizes the need for appropriate research designs when attempting to isolate the effect of HA amplification on balance, including the use of appropriate comparisons or comparison groups where HA amplification is varied but the presence and type of balance problem is kept constant (or controlled for in an apprriate manner).

If hearing does contribute to balance, then research could benefit from identifying which impairments in which balance systems (visual, somatosensory and/or vestibular) are best managed by HA amplification. Research could also benefit from identifying which features in a HA maximize any benefits of amplification on balance. Examples could include the potential benefit of binaural HA fittings to maximize sound localization and noise suppression technologies to improve sound quality (although the latter would need to be implemented in a manner that doesn’t interfere with the former).

The arguments offered above also identify the need to specify the details of the external sounds being amplified by the HAs during the HA and balance task. The use of white, pink, or narrow-band noises can offer consistency amongst research studies but can lack ecological validity. The use of linguistically loaded noise (such as BKB sentences) could increase the need for cognitive resources by creating a dual-task scenario where the listener must both maintain balance and understand the linguistic content of the sound (Kowalewski et al., 2018).

The current systematic review differs from the two previous systematic reviews (Borsetto et al., 2021 and Ernst et al., 2021) and one critical review (Carpenter and Campos (2020) in three of ways. First were differences in the included studies with Borsetto et al. (2021) reviewing eight studies and not reviewing three studies included in the present review (Ibrahim et al., 2019; Kowalewski et al., 2018; Ninomiya et al., 2021); Ernst et al. (2021) reviewing five studies and not reviewing five of the studies included in the present review (Ibrahim et al., 2019; Maheu et al., 2019; Kowalewski et al., 2018; Ninomiya et al., 2021; Vitkovic et al., 2016); and Carpenter and Campos (2020) using a different research design to address different aims to those addressed by the current review, which resulted in their review including only three studies investigating the effect of HAs on static balance (Maheu et al., 2019; Negahban et al., 2017; Vitkovic et al., 2016). Reasons for the differences in studies included between the present review and the three previously published reviews were difficult to determine due to differences in the use and reporting of inclusion/exclusion criteria. Second was the lack of explicit quality assessments of the included studies in the previous reviews, which was remedied by the present review's use of a validated quality assessment tool (Downs & Black, 1998). Third, was the less detailed descriptions of the studies in the previous reviews by Borsetto et al. (2021) and Ernst et al. (2021), which was remedied by the more detailed descriptions of the studies in the present review, particularly with regards to methods, balance measurements, acoustic environments, HI, and HAs.

Future Research

Future research into HAs and balance should address the methodological and conceptual limitations of the current evidence. Adequately powered, longitudinal Randomised Control Trial (RCT) designs should be considered to better elucidate and effects of HAs on both static and dynamic balance in adults with varying degrees, types and aetiologies of HI. The scale of such studies (and the resources required to conduct them) is noted and the use of high-quality observational studies should also be considered given their potential to provide evidence of an association (or not) between HAs and balance in adults with hearing loss. Issues regarding the external and internal validity of future studies should also be addressed via efforts to improve the degree to which sampled participants represent the target population, use of control groups and/or control conditions, blinding of participants and assessors, and control of confounding variables.

More ecologically valid trial settings should also be considered that better represent the real-world environments in which adults with HI regularly struggle with their balance. This could include using acoustical environments that resemble everyday listening situations rather than using white or filtered noise.

Future research should also consider the details of both the HAs and participant use of HAs such as HA type, monaural versus binaural fittings, insertion gain settings, programming algorithms, time since fitting, and daily use to name but a few. This call for greater detail could be premature, however, given the ongoing need to confirm if amplification via HAs can improve balance in adults with hearing loss, and if so, what mechanisms underpin any associations and do those mechanisms differ for static versus dynamic balance.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, is the pressing need to investigate the effect of amplification provided by HAs on the balance of adults with a wide range of self-reported and measured balance problems. Any benefit of HAs on balance is most likely to be realized in adults with hearing and balance impairments rather than HI alone.

Methodological Limitations and Strengths of the Current Review

This systematic review was limited to papers published in the English language in peer-reviewed journals only. The application of the search strategy and inclusion criteria identified only ten papers for inclusion, although the authors were confident that these 10 papers represented all the current research addressing the question asked in the current review.

Conclusion

For adults with HI, the evidence is equivocal that amplification with HAs improves static and dynamic balance compared to no amplification or to an unaided control group. Of the 10 studies reviewed, six reported significant improvements in balance with HA use and four reported no improvements in balance with HA use, and all studies were limited by their fair to poor quality. Future research into the potential effects of HAs on balance in adults with HI should focus on adequately powered, longitudinal designs that use ecologically valid methods to better elucidate the effects of HAs on both static and dynamic balance in adults with hearing and balance impairment.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tia-10.1177_23312165221121014 for A Systematic Review of the Effect of Hearing Aids on Static and Dynamic Balance in Adults with Hearing Impairment by Marina Tareq Mahafza, Wayne J. Wilson, Sandra Brauer, Barbra H. B. Timmer and Louise Hickson in Trends in Hearing

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Sonova AG, Stäfa, Switzerland, for funding the PhD studentship for Marina Mahafza. The authors thank Ms. Katrina Kemp and Ms. Jacinta Foster for their support in the screening and reviewing of the studies for inclusion in the review. They are also grateful for the two anonymous reviewers and editors for helping improve the manuscript.

Glossary

List of Abbreviations

- ABC scale

Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale

- AC

Air Conduction

- AP

Anterior Posterior

- BBN

Broad Band Noise

- BBS

Berg Balance Scale

- BKB-SIN

Bamford Kowal-Bench Speech-in-Noise test

- CoP

Centre of Pressure

- dB

Decibel

- FES-I

Falls Efficacy Scale-International

- HA

Hearing Aid

- HI

Hearing Impairment

- ITC

In the Canal

- ITE

In the Ear

- KHz

Kilo Hertz

- m

meter

- mCTSIB

modified Clinical Test of Sensory Interaction in Balance

- ML

Mediolateral

- N

Number

- PICO

Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome

- RoF

Romberg on Foam

- PROSPERO

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- PRISMA-P

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT

Randomised Control Trial

- s

seconds

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SPL

Sound Pressure Level

- SOT

Sensory Organization Test

- SNHL

Sensorineural Hearing Loss

- RITE

Receiver In the ear

- TST

Tandem Stance Test

- TUG

Time Up and Go

- WN

White Noise.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Sonova AG, Stafa, Switzerland, (grant number Sonova AG, PhD scholarships).

ORCID iDs: Marina Tareq Mahafza https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5099-6465

Wayne J. Wilson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8141-5173

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Agmon M., Lavie L., Doumas M. (2017). The association between hearing loss, postural control, and mobility in older adults: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 28(6), 575–588. 10.3766/jaaa.16044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal Y., Zuniga M. G., Davalos-Bichara M., Schubert M. C., Walston J. D., Hughes J., Carey J. P. (2012). Decline in semicircular canal and otolith function with age. Otology & Neurotology, 33(5), 832–839. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182545061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker N., Gough C., Gordon S. J. (2021). Inertial sensor reliability and validity for static and dynamic balance in healthy adults: A systematic review. Sensors, 21(15), 5167. 10.3390/s21155167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford J., Bench R. J. (1979). Speech-hearing tests and the spoken language of hearing-impaired children. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berg K. O., Wood-Dauphinee S. L., Williams J. I., Maki B. (1992). Measuring balance in the elderly: Validation of an instrument. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 83(Suppl 2), S7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge J. E., Nordahl S. H. G., Aarstad H. J., Goplen F. K. (2019). Hearing as an independent predictor of postural balance in 1075 patients evaluated for dizziness. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 161(3), 478–484. 10.1177/0194599819844961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellman S., Davies A., Fuggle P., Grant D., Smith I. (1996). Mild impairment of neuro-otological function in early treated congenital hypothyroidism. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 74(3), 215–218. 10.1136/adc.74.3.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsetto D., Corazzi V., Franchella S., Bianchini C., Pelucchi S., Obholzer R., Ciorba A. (2021). The influence of hearing aids on balance control: A systematic review. Audiology and Neurotology, 26(4), 209–217. 10.1159/000511135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos J., Ramkhalawansingh R., Pichora-Fuller M. K. (2018). Hearing, self-motion perception, mobility, and aging. Hearing Research, 369(Nov), 42–55. 10.1016/j.heares.2018.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M. G., Campos J. L. (2020). The effects of hearing loss on balance: A critical review. Ear and Hearing, 41(1), 107S–119S. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Huang W. G., Zha D. J., Qiu J. H., Wang J. L., Sha S. H., Schacht J. (2007). Aspirin attenuates gentamicin ototoxicity: From the laboratory to the clinic. Hearing Research, 226(1-2), 178–182. 10.1016/j.heares.2006.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H., Blatchly C. A., Gombash L. L. (1993). A study of the clinical test of sensory interaction and balance. Physical Therapy, 73(6), 346–351. doi: 10.1093/ptj/73.6.346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J. J., De Luca C. J. (1995). The effects of visual input on open-loop and closed-loop postural control mechanisms. Experimental Brain Research, 103(1), 151–163. doi: 10.1007/BF00241972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida Ciquinato D. S., Doi M. Y., da Silva R. A., de Oliveira M. R., de Oliveira Gil A. W., de Moraes Marchiori L. L. (2020). Posturographic analysis in the elderly with and without sensorineural hearing loss. International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology, 24(04), e496–e502. 10.1055/s-0040-1701271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks J. J., Dinnes J., D'Amico R., Sowden A. J., Sakarovitch C., Song F., Altman D. (2003). Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 7(27), 27. 10.3310/hta7270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deviterne D., Gauchard G. C., Jamet M., Vançon G., Perrin P. P. (2005). Added cognitive load through rotary auditory stimulation can improve the quality of postural control in the elderly. Brain Research Bulletin, 64(6):487–492. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs S. H., Black N. (1998). The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 52(6), 377–384. 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddins D. A., Hall J. W. (2010). Binaural processing and auditory asymmetries. In The aging auditory system (pp. 135–165). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst A., Basta D., Mittmann P., Seidl R. O. (2021). Can hearing amplification improve presbyvestibulopathy and/or the risk-to-fall? European Archives of oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 278(8), 2689–2694. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06414-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Smith C. D., Wyman J. F., Elswick R, Jr., Fernandez T., Newton R. A. (1995). Test-retest reliability of the sensory organization test in noninstitutionalized older adults. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 76(1), 77–81. 10.1016/S0003-9993(95)80047-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina S. T., Mapes F., Kim S., Frisina D. R., Frisina R. D. (2006). Characterization of hearing loss in aged type II diabetics. Hearing Research, 211(1-2), 103–113. 10.1016/j.heares.2005.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galán-Mercant A., Cuesta-Vargas A. I. (2014). Mobile romberg test assessment (mRomberg). BMC research Notes, 7(1), 1–8. 10.1186/1756-0500-7-640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandemer L., Parseihian G., Kronland-Martinet R., Bourdin C. (2017). Spatial cues provided by sound improve postural stabilization: Evidence of a spatial auditory map? Frontiers in Neuroscience, 11(Jun 26), 357. 10.3389/fnins.2017.00357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer S. M., Berg S., Era P. (2003). Evaluating the interdependence of aging-related changes in visual and auditory acuity, balance, and cognitive functioning. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 285–305. 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper P., Jutai J. W., Strong G., Russell-Minda E. (2008). Age-related macular degeneration and low-vision rehabilitation: A systematic review. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology/Journal Canadien D'ophtalmologie, 43(2):180–187. 10.3129/i08-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim I., Da Silva S. D., Segal B., Zeitouni A. (2019). Postural stability: Assessment of auditory input in normal hearing individuals and hearing aid users. Hearing, Balance and Communication, 17(4), 280–287. 10.1080/21695717.2019.1630983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiam N. T. L., Li C., Agrawal Y. (2016). Hearing loss and falls: A systematic review and meta–analysis. The Laryngoscope, 126(11), 2587–2596. doi: 10.1002/lary.25927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewski V., Patterson R., Hartos J., Bugnariu N. (2018). Hearing loss contributes to balance difficulties in both younger and older adults. Journal of preventive medicine, 3(2), 12. doi: 10.21767/2572-5483.100033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacerda C. F., Silva L. O. E., de Tavares Canto R. S., Cheik N. C. (2012). Effects of hearing aids in the balance, quality of life and fear to fall in elderly people with sensorineural hearing loss. International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology, 16(2), 156–162. 10.7162/S1809-97772012000200002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S. T., Pichora-Fuller M. K., Li K. Z., Singh G., Campos J. L. (2016). Effects of hearing loss on dual-task performance in an audiovisual virtual reality simulation of listening while walking. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 27(7), 567–587. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.15115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F. R., Ferrucci L. (2012). Hearing loss and falls among older adults in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(4), 369–371. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheu M., Behtani S. L., Nooristani S. M., Houde S. M., Delcenserie S. A., Leroux S. T., Champoux S. F. (2019). Vestibular function modulates the benefit of hearing aids in people with hearing loss during static postural control. Ear and Hearing, 40(6), 1418–1424. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maidment D. W., Barker A. B., Xia J., Ferguson M. A. (2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the effectiveness of alternative listening devices to conventional hearing aids in adults with hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology, 57(10), 721–729. 10.1080/14992027.2018.1493546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki B. E., Holliday P. J., Topper A. K. (1994). A prospective study of postural balance and risk of falling in an ambulatory and independent elderly population. Journal of Gerontology, 49(2), M72–M84. 10.1093/geronj/49.2.M72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel D. M., Motts S. D., Neeley R. A. (2018). Effects of bilateral hearing aid use on balance in experienced adult hearing aid users. American Journal of Audiology, 27(1), 121–125. 10.1044/2017_AJA-16-0071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer I., Benjuya N., Kaplanski J. (2001). Age-Related changes of postural control: Effect of cognitive tasks. Gerontology, 47(4), 189–194. 10.1159/000052797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., The Prisma Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdin L., Schilder A. G. (2015). Epidemiology of balance symptoms and disorders in the community: A systematic review. Otology & Neurotology, 36(3), 387–392. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman I. (2003). Introduction to evidence-based dentistry. In Clarkson J., Harrison J. E., Ismail A. I., Needleman I., Worthington H. (Eds.), Evidence based dentistry for effective practice (pp. 1–18). Martin Dunitz. [Google Scholar]

- Negahban H., Bavarsad Cheshmeh Ali M., Nassadj G. (2017). Effect of hearing aids on static balance function in elderly with hearing loss. Gait & Posture, 58(Oct), 126–129. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.07.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninomiya C., Hiraumi H., Yonemoto K., Sato H. (2021). Effect of hearing aids on body balance function in non-reverberant condition: A posturographic study. PLoS one, 16(10), e0258590. 10.1371/journal.pone.0258590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J., Roberts H., Sowden A., Petticrew M., Arai L., Rodgers M., Duffy S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version, 1, b92. 10.1332/174426407781738029. [DOI]

- Powell L. E., Myers A. M. (1995). The activities-specific balance confidence (ABC) scale. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 50(1), M28–M34. 10.1093/gerona/50A.1.M28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray C. T., Horvat M., Croce R., Mason R. C., Wolf S. L. (2008). The impact of vision loss on postural stability and balance strategies in individuals with profound vision loss. Gait & Posture, 28(1), 58–61. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumalla K., Karim A. M., Hullar T. E. (2015). The effect of hearing aids on postural stability. The Laryngoscope, 125(3), 720–723. 10.1002/lary.24974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos T. G. T. D., Venosa A. R., Sampaio A. L. L. (2015). Association between hearing loss and vestibular disorders: a review of the interference of hearing in the balance.

- Schoppen T., Boonstra A., Groothoff J. W., de Vries J., Göeken L. N., Eisma W. H. (1999). The timed “up and go” test: Reliability and validity in persons with unilateral lower limb amputation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 80(7), 825–828. 10.1016/S0003-9993(99)90234-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., Stewart L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ, 349(Jan), g7647. 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumway-Cook A., Horak F. B. (1986). Assessing the influence of sensory interaction on balance: Suggestion from the field. Physical Therapy, 66(10), 1548–1550. doi: 10.1093/ptj/66.10.1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoneau G. G., Ulbrecht J. S., Derr J. A., Cavanagh P. R. (1995). Role of somatosensory input in the control of human posture. Gait & Posture, 3(3), 115–122. 10.1016/0966-6362(95)99061-O [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Kojima S., Takeda H., Ino S., Ifukube T. (2001). The influence of moving auditory stimuli on standing balance in healthy young adults and the elderly. Ergonomics, 44(15), 1403–1412. doi: 10.1080/00140130110110601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E., Martines F., Bianco A., Messina G., Giustino V., Zangla D., Palma A. (2018). Decreased postural control in people with moderate hearing loss. Medicine, 97(14):e0244. 10.1097/MD.0000000000010244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitkovic J., Le C., Lee S., Clark R. (2016). The contribution of hearing and hearing loss to balance control. Audiol. Neuro-Otol, 21(4), 195–202. 10.1159/000445100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver T. S., Shayman C. S., Hullar T. E. (2017). The effect of hearing aids and cochlear implants on balance during gait. Otology & Neurotology, 38(9), 1327–1332. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West S., King V., Carey T. S., Lohr K. N., McKoy N., Sutton S. F., Lux L. (2002). Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence (Evidence report/Technology assessment No. 47 (Prepared by the Research Triangle Institute-University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-97-0011). AHRQ Publication No. 02-E016). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley L., Beyer N., Hauer K., Kempen G., Piot-Ziegler C., Todd C. (2005). Development and initial validation of the falls efficacy scale-international (FES-I). Age and Ageing, 34(6), 614–619. 10.1093/ageing/afi196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X., Yost W. A. (2013). Relationship between postural stability and spatial hearing. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 24(9), 782–788. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.24.9.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga M. G., Dinkes R. E., Davalos-Bichara M., Carey J. P., Schubert M. C., King W. M., Agrawal Y. (2012). Association between hearing loss and saccular dysfunction in older individuals. Otology & Neurotology, 33(9), 1586. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31826bedbc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tia-10.1177_23312165221121014 for A Systematic Review of the Effect of Hearing Aids on Static and Dynamic Balance in Adults with Hearing Impairment by Marina Tareq Mahafza, Wayne J. Wilson, Sandra Brauer, Barbra H. B. Timmer and Louise Hickson in Trends in Hearing