Abstract

In addition to the threat of serious illness, COVID-19 and subsequent restrictions had devastating economic consequences for many US citizens. This study examines the evolution of food security over the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic testing whether the initial economic stimulus payment improved the nutritional well-being of vulnerable populations. We use data from phase 1 of the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey among a nationally representative sample of adults and the 2017–2018 Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement. Using an ordered logistic regression, we assess differences in the incidence and severity of food security across demographic, income, geographic, and employment status cohorts and assess the effects of the first economic stimulus payment. Our results show that marginalized groups faced greater food insecurity and had food-related outcomes worsen over time. Blacks, Hispanics, and individuals living in rural areas became less food secure as the pandemic progressed. However, receipt of a stimulus payment appears to have improved conditions. Rising food prices and persistent high unemployment have the potential to exacerbate food insecurity among marginalized and at-risk groups.

Keywords: COVID-19, Stimulus, Inequality, Racial differences, Black, Rural, Food security

Introduction

In their 2020 report, the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) estimated that nearly 8.9% of the world’s population lives in hunger [1]. Moreover, the FAO also estimated that the number of people affected by severe food insecurity is increasing, decreasing the likelihood of achieving the zero-hunger sustainable development goal. The pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (COVID-19) has created harsh economic conditions that left many individuals unemployed, increased food prices, and increased the probability of becoming food insecure. These effects have been felt in high-income [2], middle-income, and low-income nations [1, 3].

International organizations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggested that countries use direct transfers to ease the economic burden of the pandemic [4]. Accordingly, the US government began the disbursement of economic stimulus checks to qualified households in April 2020. The dollar amount of this payment varied by the number and status of the household members and was intended to help individuals bridge any income gap that may have arisen due to the pandemic. This stimulus was an unconditional cash transfer. An average household with two adults and two children received $1200 per adult and an extra $500 per child. The timing of the receipt of the stimulus payment varied depending on if the household was enrolled in direct deposit with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). However, most recipients received their direct deposit on April 15th and the two following weeks. For those who did not typically file tax returns or opted to receive paper checks, mailing began in May and continued throughout the month.

In addition to its immediate consequences, such as hunger and psychological distress, food insecurity is also associated with adverse long-term health outcomes. In particular, studies over the last several decades have demonstrated that food insecurity is associated with worse outcomes on health exams [5], being in poor health [6, 7], increased odds of being hospitalized [8], decreased nutrient intakes [9, 10], and chronic diseases and conditions such as diabetes [11, 12], hypertension [5], obesity [13], and childhood asthma [14, 15]. Furthermore, several of these conditions impair immune function and weaken the immune response, making it more difficult for individuals to fight infections [16–18]. This concern becomes even more critical in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as severe outcomes, including death, are already associated with these exact underlying health conditions [19].

We focus on the USA for a couple of reasons. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity (measured as a lack of food consumption) among US citizens increased after the 2008 financial crisis and remained relatively constant through 2014 [20]. In 2015, food insecurity began to decrease, but the recovery was stalled by the onset of the COVID pandemic in 2020. Rates of food insecurity in the USA have historically been higher than the national average for households with incomes near or below the federal poverty line, households with children (particularly those headed by single adults), adults living alone, Black- and Hispanic-headed households, and households in principal cities [21, 22].

As the number of COVID-19 cases in the USA rapidly rose in early 2020, communities already hard-hit by food insecurity became further strapped for resources, as mandated business shutdowns, increasing unemployment, and food supply chain shortages added to the challenges in acquiring sufficient food [23–25]. Historically, job loss coupled with the loss of childcare is associated with lower food security. Low-income earners have been disproportionately hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, being more likely to lose their income and be food insecure. For example, Census Bureau surveys from the summer of 2020 show that food insecurity among Black households with children has increased from 25 to 39% since 2018, and food insecurity among Hispanic households with children has increased from 17 to 37% in the same period [26]. Moreover, school closures have removed children’s access to meals provided for free or at reduced costs, which increases food pressure on larger families [27]. Furthermore, many of the communities already disproportionately experiencing food insecurity are the same ones disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 disease itself [28–30].

With the wide-ranging effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is increasingly critical that governments roll out the most effective responses to communities in need. The stimulus check of April 2020, received by over 80 million US citizens [31, 32], provides a unique opportunity to study the efficacy of this government response and whether cash flows may be an effective tool in helping to combat food insecurity.

Previous research has shown that COVID-related stimulus payments in developed democracies allowed individuals to buy more food once received [31–35]. Thus, we expect that the most vulnerable households will suffer from less food insecurity after the distribution of stimulus payments. However, this expectation might be mitigated by the pandemic’s differential across race and urbanization since this has been highlighted by previous studies [22]. In fact, news reports worldwide illustrate that more vulnerable groups face higher levels of food insecurity. This paper analyzes the relationship between economic stimulus and food insecurity in certain population subgroups.

This paper’s main objective is to analyze if the stimulus packages reduced the incidence of food insecurity in marginalized households during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the rising food prices and the persistent high unemployment that accompanied the pandemic, it is plausible that the stimulus packages were unable to ameliorate the lack of food consumption during the first months of the pandemic. We use nationally representative data from the USA and a series of regression analyses to assess the differences in the incidence and severity of food security across demographic, income, geographic, and employment status cohorts.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Variable Operationalization

This paper’s empirical analysis centers on the US Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey (HPS): a quick deployment cross-sectional data collection instrument designed to collect information on a range of topics that have impacted US households during the pandemic. The HPS asked household heads about their experiences in terms of employment status, spending patterns, food security, housing, physical and mental health, access to health care, and educational disruption. In weeks 1 and 2 of the survey, the Census Bureau sampled nearly 1.9 million and 1.0 million housing units, respectively. It added an additional 1.1 million addresses each week thereafter to ensure that the survey remained representative of the US population. In total, the survey sampled approximately 13.8 million housing units collecting roughly 108,000 responses per week, for an approximate 5.0% response rate. This study utilized Phase I of the HPS collected between April 23 and July 21, 2020. Twelve cross-sectional sample which were collected roughly bimonthly were assembled to create the full Phase I HPS data file.

HPS was designed to produce estimates at three different geographical levels—metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), state, and nation. Sampling for the HPS was drawn from the Census Bureau Master Address File (MAF) and was applied through four adjustments within each state to account for nonresponse and coverage of the interview persons demographic characteristics. These adjustments were as follows: (1) household nonresponse adjustment to account for households that do not respond to the survey; (2) an adjustment to control the weights to the occupied housing unit counts using the American Community Survey (ACS) occupied housing unit estimates based on the 2014–2018 5-year estimates; (3) an adjustment to account for the number of adults within the housing unit; and (4) a two-step iterative raking procedure which rakes the demographics of the interviewed persons to known educational attainment/sex/age distributions and ethnicity/race/sex/age population distributions. Within each state, demographic groups of interviewed persons were assessed prior to the raking procedure to determine if collapsing was necessary. The base weights reflect these sampling rates and adjustment procedures.

The federal payment was a cash transfer to US citizens, permanent residents, or qualifying resident aliens. The only qualification was that an individual must have a Social Security Number and not be claimed as a dependent on another taxpayer’s tax return. Individuals received $1200 per person if they filed individual tax returns with annual adjusted gross income (AGI) of $75,000 or less, if they filed as head of household with AGI less than $112,500, or if they filed married jointly with AGI less than $150,000. There was an income cap on the amount received: individuals with no qualifying children did not receive an Economic Impact Payment (EIP) if their AGI was more $99,000, $136,500, or $198,000, respectively.

Importantly, the presence of children in a household affected the stimulus amount received. Recipients got up to an additional $500 per qualifying child (subject to the same qualifications as above and were less than 17 years of age when the latest tax return was filed). The total-phaseout cutoff AGI levels increased by $10,000 for each qualifying child [36].

To account for the relative importance of the stimulus to the respondent, we include an explanatory variable for household income. The transfer itself was first distributed electronically to those who had filed their taxes online in the prior year and was then subsequently distributed via mail to all remaining others. Because it applied to all US persons and was agreed upon on a short-term basis by elected officials, the transfer can be treated exogenously.

Despite these arguments for its exogeneity, it could be argued that EIP receipt was endogenously related to whether the respondent filed taxes online, and therefore potentially to previous food insecurity levels. However, the quantity of interest is the effect of household-level stimulus receipt on food insecurity. Methods to correct for endogenous selection bias, such as a Heckman style model, would limit the second stage of the analysis to only estimating the effect of stimulus on food insecurity conditional on receiving the stimulus. They are therefore unsuitable for analyses of the quantity of interest. In order to ensure that these effects are accurately estimated, we perform additional robustness tests on a data set matched by stimulus receipt.

To measure food security, we leverage a question on phase 1 of the HPS asking respondents how to best describe “household food consumption in the last 7 days.” Respondents could choose one of the following 4 statements:

Enough of the kinds of food (I/we) wanted to eat,

Enough, but not always the kinds of food (I/we) wanted to eat,

Sometimes not enough to eat,

Often not enough to eat.

We treat this variable as a categorical/count variable given the different levels of food security presented for each response. For robustness in the empirical estimation, we also use two more questions that ask respondents whether food insecurity arises from lack of ability to pay for food and whether the respondent is confident in her ability to secure food. Morales, Morales, and Beltrán use a similar strategy in their analysis of food insecurity during the first week of HPS collection [37].

The HPS asked a new question beginning in week seven to evaluate household use of the federal stimulus payment. We use this question to create an indicator variable if the respondent received such payment. Furthermore, we include a range of socioeconomic and demographic variables to serve as controls. These include income, age, employment status, marital status, gender, and household size. We create an indicator variable for having an educational attainment level equal to or greater than a high school degree. We also create a variable for household size based on respondent indication of the number of individuals in their household under the age of 18 and dichotomous variables for respondent racial, ethnic, and residential self-classification. Finally, we create an indicator of “rural” status for households located outside one of 15 classified MSAs.

HPS is a cross-sectional survey containing very few questions about events that occurred in the past or the recipient’s state at points in the past. However, the literature has shown that families that suffered food security in the past are more likely to suffer from it again. We take two steps to measure whether the household has a history of food insecurity before the survey was answered. First, we consider the HPS measure of respondent household food sufficiency before March 13, 2020, as a baseline measure of food insecurity before the stimulus was disbursed. Second, to compare food security during the COVID-19 pandemic to measures of food security during previous time periods, we match the HPS households with entries in the Current Population Survey’s Food Security Supplement (CPS-FSS).1,2,3 We use adult food security status reported in the CPS, which is the closest analog to the HPS measure. Moreover, like the HPS measure, the CPS measure consists of four response categories reflecting an ordered level of difficulty obtaining food, making matching logically consistent. Table 1 shows correspondence between the CPS and HPS ordered categories.

Table 1.

CPS food security and HPS food sufficiency categories

| Rank | CPS | HPS |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | High food security | Enough of the kinds of food (I/we) wanted to eat |

| 1 | Marginal food security | Enough, but not always the kinds of food (I/we) wanted to eat |

| 2 | Low food security | Sometimes not enough to eat |

| 3 | Very low food security | Often not enough to eat |

To create this second historical food security measure, we matched HPS respondents with similar individuals in the 2018 CPS using propensity score matching (PSM).4 We matched on demographic variables common to both the HPS and CPS: race, ethnicity, gender, age, marital status, current employment status, household size, state of residence, and household income. To produce high-quality matches but ensure that final estimates were not biased, we chose two-to-one greedy matching with replacement.5 This method minimizes the propensity score distance between the matched pairs such that each HPS respondent is matched to the two closest CPS respondents even if the CPS respondent has been selected before. To avoid bad matches, CPS and HPS respondents are only matched if the propensity score match lies within ± 0.5%. We assessed match quality by comparing the characteristics of the original HPS cohort and the matched HPS cohort to ensure that the standardized variable differences were within an acceptable differential so not to alter the covariate distribution.

Empirical Estimations

We use a three-part empirical approach. We first assess the effect of the pandemic on food security over all 12 weeks of data. In the second and third parts of the analysis, we divide the 12-week phase 1 survey into two 6-week panels—pre-stimulus and post-stimulus—and estimate the statistical model separately for each. This three-part approach separates the effect of the pandemic over time from the effects of the stimulus. Block bootstrapping (as recommended by [36]) was then performed to correct the standard errors and confidence intervals generated from the matched sample regression.

To identify different population subgroups, we rely on HPS respondent self-classification by race (White, Black, Asian, any other race alone, or other combination) and ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic). Based on these responses, we created four racial/ethnic subgroups—White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and other. We include dichotomous indicators for Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and other race, leaving White non-Hispanic as the reference category. We also include dichotomous demographic control variables for whether a respondent identifies as female, married, employed, and having less than a high school education.

To capture the trend in food security over time, we include a variable for the survey week and the prior level of food security measured from the matched 2018 CPS to account for intertemporal variation. Finally, we include time-subgroup interaction terms (Black, Hispanic, and rural indicators) to test for differences during the sample among different groups. We weighted all estimates using person-level sampling weights to conform to a nationally representative sample.

Because our food security dependent variable is expressed as a, ranked, discrete numeric value, we use ordinal logistic (OL) regression as our empirical model.6 Due to the ordering of dependent variable levels, the OL regression accounts for discrete and ordered nature and the relationship between discrete and continuous regressors. One of the assumptions underlying OL regression is that the relationship between each pair of outcome groups is the same. In other words, OL assumes that the coefficients that describe the relationship between, say, the lowest versus all higher categories of the response variable are the same as those that describe the relationship between the next lowest category and all higher categories, etc. The proportional odds assumption allows for the estimation of only one set of coefficients. Application of the Brant test indicates whether this assumption is met or violated.

Given that food security also represents categories of counts of a food-related condition, a negative binomial (NB) and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression were also estimated as a robustness tests. The NB model accounts for overdispersion, the presence of disproportionately more zeros than any other numerical category, which is particularly important because most respondents during the early weeks of the pandemic did not experience food insecurity. The OLS regression provides highly logical and interpretable results despite unreliable standard errors. For the 12-week period, our basic empirical model is:

| 1 |

The empirical model for the second and third parts of the analysis is slightly different. It includes a dummy variable for receipt of the stimulus payment (EIP) as well as interactions between each subgroup and receipt of the payment:

| 2 |

For interpretability reasons, we also present OLS results as a test for robustness7.

Results

Quality of Matches

A total of 1,066,593 respondents from HPS reported their level of food security during the first 3 months of the pandemic. Most of these respondents were female (60.0, SD = 0.49), most were married (58.1, SD = 0.49), and the average age was 51.6 (SD = 12.72). Only about 2% had not graduated from high school (1.9, SD = 0.14). Hispanics (9.0, SD = 0.28) and Blacks (8.0, SD = 0.27) comprise less than 20% of respondents, and 57% of respondents (SD = 0.49) were employed at the time of the survey. The average income level is 4.54 (SD = 2.09), which corresponds to an annual income between $35,000 and $45,000. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the matched and unmatched samples, which are nearly identical.8

Table 2.

Comparison of matched and unmatched sample characteristics

| Unmatched HPS sample | Matched HPS sample | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std dev | Min | Max | N | Mean | Std dev | Min | Max | |

| Income | 1,066,593 | 4.54 | 2.09 | 1 | 8 | 941,575 | 4.54 | 2.09 | 1 | 8 |

| Black | 1,066,593 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0 | 1 | 941,575 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic | 1,066,593 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0 | 1 | 941,575 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 1,066,593 | 51.57 | 15.72 | 18 | 88 | 941,575 | 51.65 | 15.49 | 18 | 88 |

| Employed | 1,066,593 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 941,575 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Female | 1,066,593 | 0.6 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 941,575 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | 1,066,593 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0 | 1 | 941,575 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0 | 1 |

| Married | 1,066,593 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 941,575 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| State FIPS code | 1,066,593 | 27.75 | 16.2 | 1 | 56 | 941,575 | 27.78 | 16.21 | 1 | 56 |

As expected, not all HPS respondents had a suitable CPS match. To ensure the matched cohort provided an accurate presentation of the original population, Table 3 summarizes the standardized baseline characteristics of the HPS unmatched and matched samples. Demographic proportions between the two samples were similar with slight differences in characteristic means and variances.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics by racial/ethnic cohort

| N | Min | Max | Std dev | Mean | N | Mean | Std dev | N | Mean | Std dev | N | Mean | Std dev | N | Mean | Std dev | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | Black | White | Hispanic | Other race | |||||||||||||

| Average food security levels | |||||||||||||||||

| Food security2018 | 941,575 | 0 | 3 | 0.92 | 0.47 | 66,836 | 0.48 | 0.92 | 722,730 | 0.47 | 0.92 | 78,408 | 0.46 | 0.91 | 73,601 | 0.46 | 0.91 |

| Food security2019 | 940,423 | 0 | 3 | 0.58 | 0.28 | 66,722 | 0.55 | 0.8 | 721,952 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 78,232 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 73,517 | 0.33 | 0.63 |

| Food security2020 | 941,575 | 0 | 3 | 0.64 | 0.4 | 66,836 | 0.68 | 0.81 | 722,730 | 0.35 | 0.59 | 78,408 | 0.62 | 0.75 | 73,601 | 0.48 | 0.68 |

| Sample statistics for individual characteristics | |||||||||||||||||

| Age | 941,575 | 18 | 88 | 15.49 | 51.65 | 66,836 | 48.03 | 14.02 | 722,730 | 53.09 | 15.5 | 78,408 | 45.71 | 14.55 | 73,601 | 47.22 | 14.65 |

| Female | 941,575 | 0 | 1 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 66,836 | 0.7 | 0.46 | 722,730 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 78,408 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 73,601 | 0.55 | 0.5 |

| Married | 941,575 | 0 | 1 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 66,836 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 722,730 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 78,408 | 0.52 | 0.5 | 73,601 | 0.57 | 0.49 |

| HS education | 941,575 | 0 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 66,836 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 722,730 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 78,408 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 73,601 | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| # HH children | 941,575 | 0 | 5 | 1.06 | 0.66 | 66,836 | 0.86 | 1.17 | 722,730 | 0.59 | 1.02 | 78,408 | 0.94 | 1.21 | 73,601 | 0.77 | 1.1 |

| Rural | 941,575 | 0 | 1 | 0.46 | 0.7 | 66,836 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 722,730 | 0.74 | 0.44 | 78,408 | 0.54 | 0.5 | 73,601 | 0.59 | 0.49 |

| Week | 941,575 | 1 | 12 | 3.34 | 6.63 | 66,836 | 6.65 | 3.35 | 722,730 | 6.61 | 3.34 | 78,408 | 6.78 | 3.33 | 73,601 | 6.62 | 3.34 |

| Stimulus | 476,047 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.56 | 34,393 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 362,986 | 0.53 | 0.5 | 41,380 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 37,288 | 0.58 | 0.49 |

| Hispanic | 941,575 | 0 | 1 | 0.28 | 0.08 | ||||||||||||

| White | 941,575 | 0 | 1 | 0.42 | 0.77 | ||||||||||||

| Black | 941,575 | 0 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.07 | ||||||||||||

| Other race | 941,575 | 0 | 1 | 0.27 | 0.08 | ||||||||||||

N represents total number of observations

Min represents the minimum vale

Max represents the maximum value

Std dev represents the sample standard deviation

Mean represents the sample mean

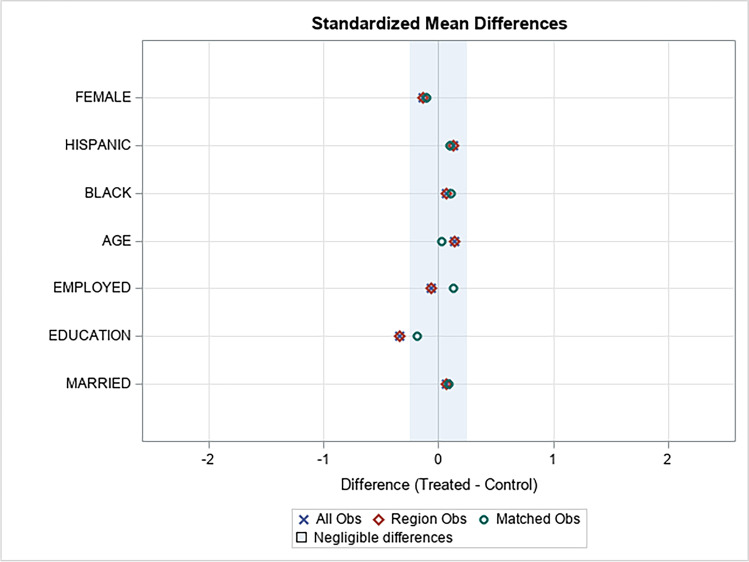

We matched the samples using propensity scores calculated from race, ethnicity, gender, age, marital status, income, employment status, and state of geographical residence. Figure 1 shows the difference between the treatment sample from HPS and the matched sample from CPS. The sample proportions differ by less than ± 0.2 suggesting high-quality matches and equivalent pairing of sample characteristics.

Fig. 1.

Standardized variable differences

Food Security in the Data

For any of our food security measures, a value of zero indicates that respondents have high food security, with enough of the type of foods they want to eat. A value of three indicates that respondents have very low food security, with often not enough to eat. Table 4 shows the distribution of all three food security metrics for 2018, 2019, and 2020 across all four racial/ethnic subgroups. All four subgroups have become less food secure over time. Although the proportion of respondents at the lowest level of food security has fallen between 2018 and 2020, the largest change is among the second tier — those who have sufficient food, but not always the types that they prefer — which increased from 9.54 to 26.88% of the full sample.

Table 4.

Food security categorical representation

| Food security categorical distribution by subgroup in 2018, 2019, and 2020 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Hispanic | Black | White | Other race | ||

| Food security2020 | High | 66.9 | 52.41 | 51.23 | 70.52 | 60.97 |

| Marginal | 26.88 | 35.4 | 32.81 | 24.96 | 31.24 | |

| Low | 5.06 | 10 | 13 | 3.67 | 6.26 | |

| Very low | 1.16 | 2.2 | 2.96 | 0.84 | 1.53 | |

| Food security2019 | High | 77.98 | 64.89 | 62.3 | 81.26 | 73.91 |

| Marginal | 17.11 | 24.76 | 23.3 | 15.42 | 19.97 | |

| Low | 3.96 | 8.35 | 11.61 | 2.69 | 4.86 | |

| Very low | 0.95 | 2 | 2.78 | 0.64 | 1.26 | |

| Food security2018 | High | 75.37 | 75.58 | 74.89 | 75.36 | 75.75 |

| Marginal | 9.54 | 9.66 | 9.56 | 9.55 | 9.36 | |

| Low | 7.89 | 7.72 | 8.21 | 7.87 | 7.97 | |

| Very low | 7.19 | 7.05 | 7.35 | 7.22 | 6.92 | |

Figure 2 shows the portion of each subgroup reporting very low food security in each of the 12 weeks of HPS Phase I. Food security is stable over time among Whites but varies more among Blacks and Hispanics. These fluctuations could a shift in the distribution of FS categories within subgroups.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of each subgroup reporting high food security and very low food security

Chi-square tests indicate that the distributions of food security are indeed statistically significantly different between Whites and Blacks (χ2 = 16,573.74, p < 0.001), Hispanics (χ2 = 9899.25, p < 0.001), and other races (χ2 = 1306.3521, p < 0.0001). Rural residents (χ2 = 169.61, p < 0.001) and women (χ2 = 3238.93, p < 0.001) also differ significantly compared to their reference category (urban residents and men, respectively).

Regression Analysis: Base Model Weeks 1–12

Table 5 shows results for the regression without the stimulus indicator or interaction terms included. Positive coefficients correspond to lower food security. Estimates indicate significantly lower food security among females (0.1458, se = 0.0053), Hispanics (0.1545, se = 0.0196), Blacks (0.1864, se = 0.0202), other racial groups (0.1471, se = 0.0189), household with children (0.0384, se = 0.0025), those without a high school diploma (0.2612, se = 0.0172), those living in rural areas (0.0338, se = 0.0124), and those who previously experienced food insecurity in 2019 (0.5952, se = 0.0191) or 2018 (0.0727, se = 0.0059) compared to the reference group. Conversely, older respondents (− 0.0115, se = 0.0002) had higher food security than younger respondents. Interaction terms for Black (0.0153, se = 0.00230), Hispanic (0.01254, se = 0.0036), other racial groups (0.0084, se = 0.0025), and rural residents (0.0127, se = 0.0017) with the weekly indicator are positive and statistically significant suggesting that these groups had comparatively lower food security than the reference group and the level of disparity changed over time.

Table 5.

Food security and race: base model ordered logit estimation

| Weeks 1–12 | Weeks 1–6 | Weeks 7–12 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log likelihood | 1,093,796 | 519,950 | 572,213 | ||||||

| AIC | 1,093,840 | 519,994 | 572,257 | ||||||

| Estimate | Std err | t-value | Estimate | Std err | t-value | Estimate | Std err | t-value | |

| Intercept(1) | − 3.05145 | 0.0176517 | − 172.86996 | − 3.53995437 | 0.0269228 | − 131.48536 | − 2.60585 | 0.0456886 | − 57.034893 |

| Intercept(2) | 0.414236 | 0.0172961 | 23.949695 | 0.092008412 | 0.026264 | 3.5032141 | 0.726198 | 0.0455041 | 15.958952 |

| Intercept(3) | 3.207183 | 0.0192434 | 166.66445 | 2.965413331 | 0.0290619 | 102.03798 | 3.453968 | 0.0469393 | 73.583642 |

| Food security2019 | 0.595203 | 0.0191383 | 311.00139 | 0.629322706 | 0.0275149 | 228.7203 | 0.564339 | 0.0268669 | 210.05015 |

| Food security2018 | 0.07266 | 0.0059203 | 12.272942 | 0.063046535 | 0.0085966 | 7.3339163 | 0.081202 | 0.0081768 | 9.9307579 |

| Age | − 0.01151 | 0.0001793 | − 64.170977 | − 0.0121812 | 0.0002616 | − 46.560643 | − 0.01079 | 0.0002467 | − 43.745577 |

| Female | 0.145847 | 0.0052526 | 27.766831 | 0.14308781 | 0.0076109 | 18.800482 | 0.147334 | 0.0072697 | 20.266904 |

| HS education | 0.261232 | 0.017151 | 15.231269 | 0.24272427 | 0.025332 | 9.5817383 | 0.28256 | 0.0233144 | 12.119556 |

| Rural | 0.03378 | 0.0124446 | 2.7144665 | 0.075214095 | 0.0199186 | − 3.7760677 | 0.066658 | 0.0457077 | 2.4583483 |

| Week | − 0.0083 | 0.0015305 | − 5.4236384 | − 0.08636938 | 0.0046301 | − 18.65389 | 0.019062 | 0.0043139 | 4.4188025 |

| # HH children | 0.038388 | 0.002457 | 15.624308 | 0.02983655 | 0.0035608 | 8.379062 | 0.044761 | 0.0034009 | 13.161492 |

| Black | 0.18641 | 0.0202282 | 9.215326 | 0.112232379 | 0.0324009 | 3.4638616 | 0.414683 | 0.0724313 | 5.7251911 |

| Hispanic | 0.154525 | 0.0196345 | 7.8700911 | 0.179951532 | 0.0318909 | 5.642717 | 0.1370978 | 0.0688497 | 1.9912622 |

| Other race | 0.147121 | 0.0188823 | 7.7914337 | 0.13188391 | 0.0304871 | 4.3258927 | 0.286427 | 0.0679534 | 4.2150591 |

| Black * Week | 0.015316 | 0.0026941 | 5.6850541 | 0.031192144 | 0.0081907 | 3.8082489 | − 0.0075672 | 0.0075079 | − 1.007903 |

| Hispanic * Week | 0.012541 | 0.0025882 | 4.8454944 | 0.005669595 | 0.0080309 | 0.7059769 | 0.014389 | 0.0071037 | 2.0256184 |

| Other race * Week | 0.008432 | 0.0025259 | 3.3380544 | 0.010647632 | 0.0077424 | 1.3752317 | − 0.0054907 | 0.007035 | − 0.7804853 |

| Rural * Week | 0.012689 | 0.0016826 | 7.5414042 | 0.024602557 | 0.0050978 | 4.8261288 | 0.0019713 | 0.0047332 | 0.4164862 |

| Odds ratios | |||||||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | ||||

| Food security2019 | 384.53221 | 370.37545 | 399.23007 | 540.8960191 | 512.499 | 570.86649 | 282.41784 | 267.93103 | 297.68794 |

| Food security2018 | 1.0753647 | 1.0629587 | 1.0879156 | 1.065076402 | 1.0472813 | 1.0831739 | 1.0845896 | 1.0673463 | 1.1021114 |

| Age | 0.9885579 | 0.9882105 | 0.9889054 | 0.987892688 | 0.9873863 | 0.9883994 | 0.9892667 | 0.9887886 | 0.9897452 |

| Female (1 vs 0) | 1.1570191 | 1.1451689 | 1.1689919 | 1.153831115 | 1.1367471 | 1.1711718 | 1.1587407 | 1.1423477 | 1.175369 |

| HS education (1 vs 0) | 1.2985286 | 1.2556036 | 1.3429211 | 1.274717098 | 1.2129732 | 1.339604 | 1.3265209 | 1.2672692 | 1.3885429 |

| Rural (1 vs 0) | 1.9667837 | 1.9434882 | 1.9906545 | 1.927544882 | 1.8920314 | 1.9644722 | 1.0689295 | 0.9773332 | 1.1691104 |

| Week | 0.9917336 | 0.9887632 | 0.994713 | 0.917255353 | 0.9089691 | 0.9256172 | 1.0192452 | 1.0106637 | 1.0278995 |

| # HH children | 1.0391345 | 1.0341425 | 1.0441506 | 1.03028612 | 1.0231207 | 1.0375018 | 1.0457775 | 1.0388299 | 1.0527715 |

| Black (1 vs 0) | 1.2049156 | 1.1580795 | 1.253646 | 1.11877281 | 1.0499344 | 1.1921246 | 1.5138912 | 1.313533 | 1.7448108 |

| Hispanic (1 vs 0) | 1.167104 | 1.1230436 | 1.2128929 | 1.197159338 | 1.1246214 | 1.274376 | 1.1469404 | 1.0021572 | 1.3126405 |

| Other race (1 vs 0) | 1.1584936 | 1.1164029 | 1.2021712 | 1.140975856 | 1.0747954 | 1.2112314 | 1.3316615 | 1.1656062 | 1.5213735 |

| Black * Week | 1.015434 | 1.0100863 | 1.02081 | 1.031683716 | 1.0152539 | 1.0483794 | 0.9924614 | 0.977964 | 1.0071736 |

| Hispanic * Week | 1.0126199 | 1.0074962 | 1.0177697 | 1.005685697 | 0.98998 | 1.0216406 | 1.0144935 | 1.0004665 | 1.0287172 |

| Other race * Week | 1.0084672 | 1.003487 | 1.0134722 | 1.01070452 | 0.995483 | 1.0261588 | 0.9945243 | 0.9809055 | 1.0083322 |

| Rural * Week | 1.0127701 | 1.0094356 | 1.0161156 | 1.024907697 | 1.0147183 | 1.0351994 | 1.0019733 | 0.992721 | 1.0113118 |

Dependent variable: food security (0 = high security, 1 = marginal food security, 2 = low food security, 3 = very low food security)

Indicates significant at the 95% confidence level

Estimates weighted using survey sampling weights

Regression Analysis: Base Model Weeks 1–6 and 7–12

Regression results from the first 6 weeks of the sample mirror the full sample results. The week during which the individual was surveyed is negative (− 0.0863, se = 0.0046) suggesting that within this time frame, individuals experienced relatively lower levels of food security in later weeks compared to earlier weeks. Regression results from the second half of the sample are also like those presented for the full 12-week duration. However, neither indicators for rural residence nor Hispanic ethnicity appear to be statistically significant from the reference group. Interaction effects vary slightly from those presented above. In the first half of the sample, only interactions with Black (0.0312, se = 0.0082) and rural (0.0246, se = 0.0051) remain statistically significant. In the second half of the sample, only the interaction with Hispanic (0.0144, se = 0.0071) is significantly different from the reference group. The significant interaction terms suggest that these groups experience even greater differences in food security compared to the reference group in the later weeks of observation than they did in the earlier weeks.

Regression Analysis: Full Model Weeks 1–6 and 7–12 (OL)

Table 6 shows the OL regression results including all interaction terms. Estimates for demographic and contextual characteristics are similar to those presented above. In the first 6 weeks, comparatively lower food security was observed among females (0.1431, se = 0.0.0076), Hispanics (0.1800, se = 0.0319), Blacks (0.1122, se = 0.0324), other racial groups (0.1319, se = 0.0305), household with children (0.0298, se = 0.0036), those without a high school diploma (0.2427, se = 0.0253), and those who previously experienced food insecurity in 2019 (0.6393, se = 0.0291) or 2018 (0.0631, se = 0.0096) compared to the reference group. Older respondents (− 0.0128, se = 0.0002) had lower food security than younger respondents. Interaction terms show that rural residents (0.0246, se = 0051) and Blacks (0.0057, se = 0.0080) experience comparatively different food security changes compared to the reference groups during the first 6 weeks.

Table 6.

Food security, stimulus payments, and race: full model ordered logit estimation

| Weeks 1–6 | Weeks 7–12 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log likelihood | 519,950 | 568,225 | ||||

| AIC | 519,994 | 568,279 | ||||

| Estimate | Std err | t-value | Estimate | Std err | t-value | |

| Intercept(1) | − 3.53995437 | 0.0269228 | − 131.48536 | − 1.914339337 | 0.049070567 | − 39.01196711 |

| Intercept(2) | 0.092008412 | 0.026264 | 3.5032141 | 1.430223734 | 0.048975534 | 29.20282059 |

| Intercept(3) | 2.965413331 | 0.0290619 | 102.03798 | 4.159100309 | 0.050321802 | 82.65006681 |

| Food security2019 | 0.629322706 | 0.0275149 | 228.7203 | 0.565832251 | 0.02699385 | 209.6152471 |

| Food security2018 | 0.063046535 | 0.0085966 | 7.3339163 | 0.05651632 | 0.008192328 | 6.898688476 |

| Age | − 0.012181203 | 0.0002616 | − 46.560643 | − 0.010335994 | 0.00024699 | − 41.84784549 |

| Female | 0.14308781 | 0.0076109 | 18.800482 | 0.12716756 | 0.007299693 | 17.42094615 |

| HS education | 0.24272427 | 0.025332 | 9.5817383 | 0.293914526 | 0.023318254 | 12.60448277 |

| Rural | 0.075214095 | 0.0199186 | 3.7760677 | 0.143287015 | 0.050113895 | 2.859227252 |

| Week | − 0.08636938 | 0.0046301 | − 18.65389 | 0.018676384 | 0.004349617 | 4.29379921 |

| # HH children | 0.02983655 | 0.0035608 | 8.379062 | 0.045125615 | 0.003408669 | 13.23848576 |

| Black | 0.112232379 | 0.0324009 | 3.4638616 | 0.64957343 | 0.081761781 | 7.944707457 |

| Hispanic | 0.179951532 | 0.0318909 | 5.642717 | 0.384415099 | 0.075236903 | 5.109395585 |

| Other race | 0.13188391 | 0.0304871 | 4.3258927 | 0.391610479 | 0.074047594 | 5.288632028 |

| Black * Week | 0.031192144 | 0.0081907 | 3.8082489 | 0.824570014 | 0.019977396 | 41.27514915 |

| Hispanic * Week | 0.005669595 | 0.0080309 | 0.7059769 | − 0.007093174 | 0.007514718 | − 0.943904137 |

| Other race * Week | 0.010647632 | 0.0077424 | 1.3752317 | 0.014652384 | 0.00710797 | 2.061402174 |

| Rural * Week | 0.024602557 | 0.0050978 | 4.8261288 | − 0.005419017 | 0.007060354 | − 0.767527672 |

| Stimulus | 0.003042242 | 0.004762261 | 0.638823106 | |||

| Black * Stimulus | − 0.293257943 | 0.041546945 | − 7.05847186 | |||

| Hispanic * Stimulus | − 0.291669634 | 0.034460361 | − 8.463916977 | |||

| Other race * Stimulus | − 0.10599822 | 0.033446012 | − 3.169233476 | |||

| Rural * Stimulus | − 0.159486795 | 0.022988053 | − 6.937812207 | |||

| Odds ratios | ||||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | |||

| Food security2019 | 540.8960191 | 512.499 | 570.86649 | 286.6673562 | 271.8948831 | 302.2424408 |

| Food security2018 | 1.065076402 | 1.0472813 | 1.0831739 | 1.058143883 | 1.041289295 | 1.075271285 |

| Age | 0.987892688 | 0.9873863 | 0.9883994 | 0.989717239 | 0.989238241 | 0.990196468 |

| Female (1 vs 0) | 1.153831115 | 1.1367471 | 1.1711718 | 1.135607285 | 1.119475671 | 1.151971354 |

| HS education (1 vs 0) | 1.274717098 | 1.2129732 | 1.339604 | 1.341669221 | 1.281731104 | 1.40441025 |

| Rural (1 vs 0) | 1.927544882 | 1.8920314 | 1.9644722 | 1.154060986 | 1.046096466 | 1.273168206 |

| Week | 0.917255353 | 0.9089691 | 0.9256172 | 1.018851878 | 1.01020299 | 1.027574815 |

| # HH children | 1.03028612 | 1.0231207 | 1.0375018 | 1.046159265 | 1.039193308 | 1.053171917 |

| Black (1 vs 0) | 1.11877281 | 1.0499344 | 1.1921246 | 1.91472389 | 1.631211979 | 2.247511435 |

| Hispanic (1 vs 0) | 1.197159338 | 1.1246214 | 1.274376 | 1.468754995 | 1.267382157 | 1.702123722 |

| Other race (1 vs 0) | 1.140975856 | 1.0747954 | 1.2112314 | 1.479361357 | 1.279513415 | 1.710423665 |

| Black * Week | 1.031683716 | 1.0152539 | 1.0483794 | 2.2808998 | 2.19331706 | 2.371979863 |

| Hispanic * Week | 1.005685697 | 0.98998 | 1.0216406 | 0.992931923 | 0.978414621 | 1.007664628 |

| Other race * Week | 1.01070452 | 0.995483 | 1.0261588 | 1.014760257 | 1.00072128 | 1.028996184 |

| Rural * Week | 1.024907697 | 1.0147183 | 1.0351994 | 0.994595639 | 0.980927176 | 1.008454562 |

| Stimulus | 1.003046874 | 0.993728134 | 1.012453002 | |||

| Black * Stimulus | 0.745829735 | 0.687503431 | 0.809104315 | |||

| Hispanic * Stimulus | 0.747015283 | 0.698227219 | 0.799212375 | |||

| Other race * Stimulus | 0.899426249 | 0.84235714 | 0.960361751 | |||

| Rural * Stimulus | 0.852581226 | 0.815020061 | 0.891873441 | |||

Dependent variable: food security (0 = high security, 1 = marginal food security, 2 = low food security, 3 = very low food security)

Indicates significant at the 95% confidence level

Estimates weighted using survey sampling weights

Following week six of the HPS, the $1200 federal stimulus payment was announced. Data is not available on exactly when payments were received, or the precise amount received. However, we accounted for individuals who received a stimulus payment at some point during weeks seven through 12. While the average food security level did not differ significantly between those that did and did not receive a stimulus (0.0030, se = 0.0048), receipt of a stimulus by identified subgroups did show a comparative difference. Blacks (− 0.2933, se = 0.0415), Hispanics (− 0.2917, se = 0.0344), other racial groups (− 0.1060, se = 0.0334), and rural residents (− 0.1595, se = 0.0230) who received a stimulus payment had statistically different food security levels than individuals in their cohort who did not receive a payment. In other words, receipt of a stimulus payment was associated with lower levels of food insecurity among all three-minority racial and residential groups.

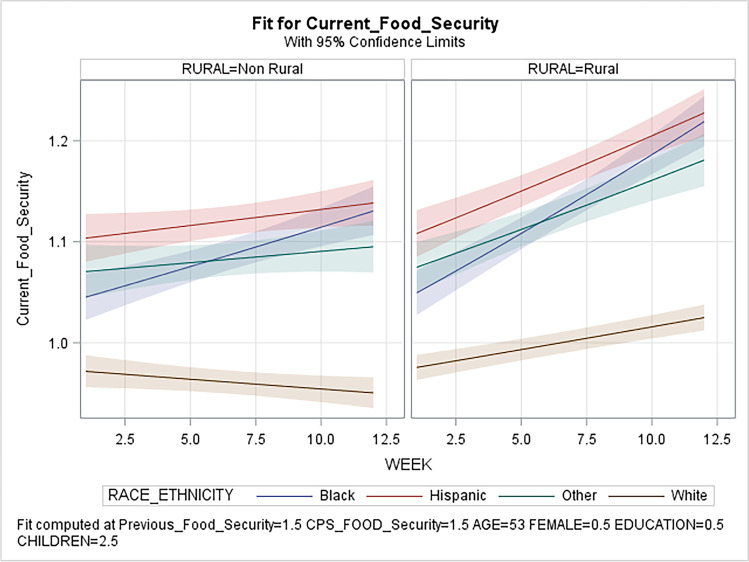

Figure 3 shows the predicted food security for each ethnic group in rural and non-rural households. Rural households experienced higher predicted levels of food insecurity than their non-rural counterparts, suggesting that the existing disparity is increasing over time.

Fig. 3.

Weeks 1–12 food security in rural and non-rural areas

Figure 4 shows predicted food insecurity for all racial groups in rural and non-rural areas for weeks one through six. Between-group racial and urban/rural disparities in food insecurity are present even early in the pandemic suggesting that they likely existed prior to the observation period.

Fig. 4.

Weeks 1–6 food security in rural and non-rural areas

Figure 5 shows predicted food insecurity level for each subgroup in weeks 7–12 split by receipt of the EIP.

Fig. 5.

Weeks 7–12 food security with the stimulus

Overall, recipients who identify as members of marginalized groups are more food insecure than members of non-marginalized groups. The positive coefficient for Stimulus indicates that the baseline effect is that EIP recipients are more food insecure, which makes sense because program eligibility was restricted by income. As a result of receiving the stimulus, members of marginalized groups experienced an overall reduction in this food insecurity, shown in each subgroup’s negative interaction coefficient. However, because the magnitudes of the interaction coefficients are less than the magnitude of the positive baseline Stimulus coefficient, this reduction did not entirely alleviate the food insecurity that marginalized groups generally experience.

Robustness Tests

Given the use of an ordered dependent variable, the Brant test was run for all models to ensure that the parallel regression assumption was in fact valid. Results indicated that all models were valid under this specification. While the authors believe that the above model meets all assumptions of the OL model, OLS regression and NB regression are specified for Eqs. 1 and 2. Results are listed in Tables 7 and 8 respectively validate the results presented above and ensure that the model selection did not greatly influence the results. While standard errors are unreliable when OLS is used to estimate a discrete dependent variable model, coefficient estimates approximate the linear association between food security and the respective regressors. The OLS coefficient estimates reinforce the findings from the OL model and similar levels of statistical significance support earlier findings. These results remained largely consistent when the number of matches, matching characteristics, and matching method were changed. Additionally, to ensure that structural differences between age and gender cohorts did not bias these findings, the sample was divided by sex and age to test within the sample heterogeneity. Both genders and all age cohorts showed similar results.

Table 7.

OLS robustness

| Food security, stimulus payments, and race: OLS estimation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks 1–12 | Weeks 1–6 | Weeks 7–12 | |||||||

| R-square | 0.5095 | 0.535 | 0.4988 | ||||||

| Adj R-sq | 0.5095 | 0.535 | 0.4988 | ||||||

| F value | 65,117.4 | 35,533.3 | 23,660.6 | ||||||

| Parameter estimates | |||||||||

| Estimate | Std err | t-value | Estimate | Std err | t-value | Estimate | Std err | t-value | |

| Intercept | 0.35587 | 0.00296 | 120.37 | 0.38423 | 0.0043 | 89.3 | 0.2434 | 0.00912 | 26.69 |

| Food security2019 | 0.72163 | 0.000794 | 908.55 | 0.73553 | 0.00109 | 673.16 | 0.68684 | 0.00115 | 594.76 |

| Food security2018 | 0.0049 | 0.000576 | 8.51 | 0.00508 | 0.000793 | 6.41 | 0.00305 | 0.000825 | 3.7 |

| Age | − 0.00306 | 3.33E-05 | − 92.02 | − 0.00302 | 4.68E-05 | − 64.62 | − 0.00315 | 4.68E-05 | − 67.38 |

| Female | 0.02277 | 0.00106 | 21.55 | 0.01936 | 0.00147 | 13.21 | 0.01991 | 0.0015 | 13.24 |

| HS education | 0.05134 | 0.00206 | 24.89 | 0.04637 | 0.00294 | 15.76 | 0.05147 | 0.00286 | 17.97 |

| Rural | − 0.00298 | 0.00243 | − 1.23 | − 0.00599 | 0.0036 | − 1.66 | − 0.0002 | 0.00938 | − 0.02 |

| Week | 0.000873 | 0.00031 | 0.28 | − 0.00986 | 0.000873 | − 11.3 | 0.00174 | 0.000894 | 1.95 |

| # HH children | 0.00856 | 0.000501 | 17.06 | 0.00736 | 0.000696 | 10.58 | 0.00587 | 0.000714 | 8.22 |

| Black | 0.05013 | 0.0037 | 13.53 | 0.05593 | 0.00549 | 10.19 | 0.07104 | 0.01444 | 4.92 |

| Hispanic | 0.0433 | 0.00321 | 13.49 | 0.03575 | 0.00473 | 7.55 | 0.01798 | 0.01238 | 1.45 |

| Other race | 0.01093 | 0.00407 | 2.69 | 0.01086 | 0.00597 | 1.82 | − 0.02584 | 0.01574 | − 1.64 |

| Black * Week | 0.000893 | 0.000499 | 1.79 | − 0.00271 | 0.00142 | − 1.91 | 0.00197 | 0.00144 | 1.37 |

| Hispanic * Week | 0.0014 | 0.000433 | 3.24 | 0.00376 | 0.00122 | 3.09 | 0.00791 | 0.00125 | 6.33 |

| Other race * Week | 0.00255 | 0.000551 | 4.62 | 0.00246 | 0.00155 | 1.59 | 0.00642 | 0.00159 | 4.03 |

| Rural * Week | 0.00123 | 0.00033 | 3.72 | 0.00196 | 0.00093 | 2.1 | 0.00134 | 0.000953 | 1.41 |

| Stimulus | 0.20545 | 0.00312 | 65.81 | ||||||

| Black * Stimulus | − 0.06254 | 0.0055 | − 11.36 | ||||||

| Hispanic * Stimulus | − 0.06787 | 0.00454 | − 14.96 | ||||||

| Other race * Stimulus | − 0.00609 | 0.00561 | − 1.08 | ||||||

| Rural * Stimulus | − 0.01339 | 0.00335 | − 3.99 | ||||||

Dependent variable: food security (0 = high security, 1 = marginal food security, 2 = low food security, 3 = very low food security)

Indicates significant at the 95% confidence level

Estimates weighted using survey sampling weights

Table 8.

Negative binomial robustness

| Food security, stimulus payments, and race: negative binomial model estimation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks 1–12 | Weeks 1–6 | Weeks 7–12 | ||||

| Log likelihood | − 584,109 | − 281,512 | − 293,684 | |||

| AIC | 1,273,204 | 613,417.2 | 641,812.9 | |||

| Maximum likelihood estimates | ||||||

| Estimate | Std err | Estimate | Std err | Estimate | Std err | |

| Intercept | − 1.1768 | 0.0101 | − 1.0386 | 0.0154 | − 1.73 | 0.0306 |

| Food security2019 | 0.9292 | 0.0017 | 0.9455 | 0.0024 | 0.8522 | 0.0025 |

| Food security2018 | 0.0138 | 0.0017 | 0.0105 | 0.0025 | 0.0116 | 0.0024 |

| Age | − 0.007 | 0.0001 | − 0.0072 | 0.0002 | − 0.0067 | 0.0002 |

| Female | 0.0797 | 0.0034 | 0.0807 | 0.0049 | 0.0551 | 0.0047 |

| HS education | 0.0334 | 0.0083 | 0.0262 | 0.012 | 0.0501 | 0.0114 |

| Rural | − 0.0025 | 0.008 | − 0.0302 | 0.0127 | 0.0931 | 0.0309 |

| Week | − 0.002 | 0.001 | − 0.0419 | 0.0031 | 0.0059 | 0.0029 |

| # HH children | 0.0198 | 0.0015 | 0.0154 | 0.0021 | 0.0151 | 0.002 |

| Black | 0.0638 | 0.0116 | 0.0159 | 0.0181 | 0.4692 | 0.0447 |

| Hispanic | 0.1225 | 0.0115 | 0.0995 | 0.0184 | 0.4102 | 0.0423 |

| Other race | 0.0927 | 0.0127 | 0.0703 | 0.0202 | 0.2978 | 0.0485 |

| Black * Week | 0.0091 | 0.0015 | 0.0178 | 0.0046 | 0.0002 | 0.0044 |

| Hispanic * Week | 0.0048 | 0.0015 | 0.0095 | 0.0046 | 0.0064 | 0.0042 |

| Other race * Week | 0.0041 | 0.0017 | 0.0081 | 0.0051 | 0.0005 | 0.0048 |

| Rural * Week | 0.0065 | 0.0011 | 0.0143 | 0.0033 | 0.0019 | 0.0031 |

| Stimulus | 0.8069 | 0.0111 | ||||

| Black * Stimulus | − 0.4313 | 0.0182 | ||||

| Hispanic * Stimulus | − 0.399 | 0.0158 | ||||

| Other race * Stimulus | − 0.2351 | 0.0186 | ||||

| Rural * Stimulus | − 0.0959 | 0.0118 | ||||

Dependent variable: food security (0 = high security, 1 = marginal food security, 2 = low food security, 3 = very low food security)

Indicates significant at the 95% confidence level

Estimates weighted using survey sampling weights

Finally, individuals who received a stimulus were matched to those who did not receive a stimulus based on age, race, ethnicity, gender, marital status, state of residence, week of survey response, and previous food security. The matched sample thus included individuals who were similar except for their receipt/non-receipt of a stimulus which was not included in the HPS until week 7. Table 9 shows OL model estimation results using only weeks 7 through 12. Specifications both with and without the stimulus interaction terms using allow for the comparison of the food security levels of these matched individuals. Similar coefficients in both specifications ensure consistency and model sensitivity.

Table 9.

Stimulus matched sample

| Food security, stimulus payments, and race: ordered logit model estimation with stimulus matched sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks 7–12 | Weeks 7–12 | |||||

| Log likelihood | − 919,487 | − 905,224 | ||||

| AIC | 1,838,974 | 1,810,449 | ||||

| Maximum likelihood estimates | ||||||

| Estimate | Std err | Estimate | Std err | |||

| Intercept(1) | − 5.1549 | 0.001 | − 5.8433 | 0.0007 | ||

| Intercept(2) | − 2.8256 | 0.0009 | − 3.5335 | 0.0006 | ||

| Intercept(3) | − 0.2178 | 0.0009 | − 0.8979 | 0.0006 | ||

| Food security2019 | 1.548 | 0.0001 | 1.5027 | 0.0001 | ||

| Food security2018 | 0.0277 | 0.0001 | 0.0276 | 0.0001 | ||

| Age | − 0.0122 | 0.005 | − 0.0135 | 0.0112 | ||

| Female | − 0.0511 | 0.0001 | 0.0978 | 0.0001 | ||

| HS education | 0.3497 | 0.0002 | 0.3438 | 0.0002 | ||

| Rural | − 0.0444 | 0.0004 | 0.0602 | 0.0004 | ||

| Week | − 0.0251 | 0.0001 | 0.0221 | 0.0001 | ||

| # HH children | 0.0636 | 0.0001 | 0.0489 | 0.0001 | ||

| Black | 0.2031 | 0.0005 | 0.3456 | 0.0006 | ||

| Hispanic | 0.0678 | 0.0005 | 0.5511 | 0.001 | ||

| Other race | 0.0441 | 0.0006 | 0.1382 | 0.0014 | ||

| Black * Week | 0.0116 | 0.0001 | − 0.0065 | 0.0001 | ||

| Hispanic * Week | 0.0145 | 0.0001 | 0.0188 | 0.0001 | ||

| Other race * Week | 0.0073 | 0.0001 | 0.0142 | 0.0001 | ||

| Rural * Week | − 0.0037 | 0.0001 | − 0.0041 | 0.0001 | ||

| Stimulus | 1.0212 | 0.0003 | ||||

| Black * Stimulus | − 0.5524 | 0.0004 | ||||

| Hispanic * Stimulus | − 0.4129 | 0.0005 | ||||

| Other race * Stimulus | − 0.1583 | 0.0006 | ||||

| Rural * Stimulus | − 0.043 | 0.0004 | ||||

| Odds ratios | ||||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | |||

| Food security2019 | 4.701 | 4.7 | 4.702 | 4.493 | 4.493 | 4.494 |

| Food security2018 | 1.028 | 1.028 | 1.028 | 1.028 | 1.028 | 1.028 |

| Age | 0.988 | 0.988 | 0.988 | 0.987 | 0.987 | 0.987 |

| Female (1 vs 0) | 0.108 | 0.107 | 0.108 | 1.103 | 1.102 | 1.103 |

| HS education (1 vs 0) | 1.419 | 1.418 | 1.419 | 1.41 | 1.41 | 1.411 |

| Rural (1 vs 0) | 0.093 | 0.091 | 0.095 | 1.128 | 1.126 | 1.13 |

| Week | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.026 | 1.022 | 1.022 | 1.022 |

| # HH children | 1.066 | 1.066 | 1.066 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 |

| Black (1 vs 0) | 1.501 | 1.498 | 1.504 | 1.996 | 1.991 | 2.001 |

| Hispanic (1 vs 0) | 1.145 | 1.143 | 1.147 | 1.735 | 1.732 | 1.739 |

| Other race (1 vs 0) | 1.092 | 1.089 | 1.095 | 1.148 | 1.145 | 1.151 |

| Black * Week | 1.989 | 1.988 | 1.989 | 0.994 | 0.993 | 0.994 |

| Hispanic * Week | 1.015 | 1.014 | 1.015 | 1.019 | 1.019 | 1.019 |

| Other race * Week | 1.007 | 1.007 | 1.008 | 1.014 | 1.014 | 1.015 |

| Rural * Week | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 |

| Stimulus | 2.777 | 2.775 | 2.778 | |||

| Black * Stimulus | 0.576 | 0.575 | 0.576 | |||

| Hispanic * Stimulus | 0.662 | 0.661 | 0.662 | |||

| Other race * Stimulus | 0.854 | 0.853 | 0.855 | |||

| Rural * Stimulus | 0.958 | 0.957 | 0.959 | |||

Dependent variable: food security (0 = high security, 1 = marginal food security, 2 = low food security, 3 = very low food security)

Indicates significant at the 95% confidence level

Estimates weighted using survey sampling weights

Discussion

While food security in the USA has been slowly increasing since 2008, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic crisis has made it more difficult for households to obtain enough nutritious food as illustrated in our analysis and some others [20]. The pandemic and social distancing efforts implemented to slow its spread have disrupted global and local food supply chains [38]. Due to recessionary pressure, an unprecedented rise in unemployment, and loss of income exacerbated nutritional hardships for millions of households [39] and made vulnerable groups more vulnerable as our results show.

Our findings complement the studies focusing on how the COVID-19 pandemic has brought about all kinds of income shocks that affect food security by specifically aiming at the differential impact across race and ethnic groups [40, 41]. More specifically, the findings of this study show that young female non-educated individuals living in rural areas are more food insecure. Another consistent pattern is that households with more children usually are more food insecure than households with fewer children. This result has been found in both high-income [42, 43] and developing contexts [20, 21, 26]. We also find that Black and Hispanic individuals tend to have lower levels of food security when compared to their White counterparts and that they do worse as weeks pass. When looking at the descriptive data, we also find that all ethnic subgroups become less food secure over time. Other work in the USA has highlighted that there are differential rates of food security across races where Blacks and Hispanic households tend to be more food insecure than their White counterparts [20, 21, 26, 37, 44]. We also find that the largest change was from having sufficient food to having sufficient food but not always the types that respondents prefer. This indicates that the pandemic decreased the food options available for consumption probably through lack of purchasing power [39] which aligns to the idea that poorer households tend to be the most prone to food insecurity and have less nutritious options available to them [20, 21, 45].

Our pre-stimulus results mirror those from the 12-week analysis except for a lack of statistical significance for the Black racial indicator variable and the interaction between time and being Hispanic. These results suggest two things. First, that before the stimulus, Whites and Blacks had similar levels of food security at baseline controlling for a diverse array of factors. With the pass of time, the interaction between survey week and Blacks shows that Black respondents are more food insecure than Whites. Similarly, rural households get more food insecure with time. Second, our results show that food security for Hispanics remains high and relatively constant across time. Again, this relationship can be traced to the lack of purchasing power [39], type of economic activity [46], and employment status [26, 47], phenomena that have been exacerbated during the pandemic [48, 49].

Post-stimulus, our results indicate higher levels of food insecurity among young female non-educated individuals living in rural areas and with multiple children. When looking at the coefficients for the race indicator variables, we find that Hispanics and Blacks have higher levels of food insecurity when compared to their White counterparts. Despite this, we do find that Black individuals are becoming more food insecure with time. The fact that we do not find statistically significant results for the interaction between the time and race indicator variables for Hispanics and other races seems to suggest that food insecurity is not getting worse with time for people in these groups. Similarly, that rural households are more food insecure than urban ones but they are not getting worse with time once the stimulus is taken into account.

In terms of the stimulus, our results suggest that there is no statistically significant difference in the baseline levels of those individuals who got the stimulus and those who did. However, the interactions between our race and rural indicator variables with the stimulus imply that Black, Hispanic, and rural individuals are more food secure after receiving this money. These results indicate that households were using their stimulus to tackle food insecurity and that the stimulus is helping more vulnerable groups to insulate from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, when comparing the magnitude of our coefficients, we find that the stimulus is not able to completely counteract the effects of the pandemic on food security. Hence, the US federal stimulus response to the COVID-19 pandemic was effective at alleviating but not eradicating food insecurity.

Our findings also align with previous work suggesting that unconditional cash transfers (UCT) improve food security more than conditional cash transfers (CCT) because they do not constrain consumer choice [50, 51]. Although the literature, including this study, assesses the effect of stimulus on food security, the effects on the type of food being eaten are still unclear. Both Allcott et al. [45] and Bartlett et al. [52] show that increasing income to low-income households can increase the purchase of healthier food. However, in the USA, Hut and Oster [53] present some evidence that dietary changes are hard and often do not change in the face of household shocks like job loss and childbirth. In our categorical analysis, the fact that there is an increase in respondents saying they have enough food but not the type they want agrees with these studies.

Despite the robustness of our results, this study faces several limitations. First, the HPS is a temporary, short-term data collection instrument that collects data at a single point in time. Therefore, no historical data exists, and individuals were not repeatedly surveyed in successive weeks. Because the HPS questions change every 3 months, survey items concerning food security were removed after Phase 1. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the data makes it impossible to determine causality. Each week of the HPS included a different group of respondents making the evolution of individual food security and responses to external stimuli impossible to track. While the average number of respondents who reported lower food security increased, this study cannot definitively attribute these increases to the COVID-19 pandemic or the economic manifestations thereof. Third, propensity score matching cannot account for all sources of potential cofounders available for analysis. While we used a careful set of characteristics in the matching algorithm and carefully evaluated the quality of the matches, it is only possible to match on observed characteristics. Therefore, unobserved differences between matched pairs could have biased results. Finally, the data used in this paper is unable to identify if our results are an artifact of demand or supply factors. For instance, people could be more food insecure because the prices of food increases, people cannot physically access food, or because the food available for them is less nutritious [46, 54]. Such a limitation leaves room for additional work on the identification of the drivers in food insecurity.

Conclusion

This study illustrates the disparate monthly food security across subgroups of society. While findings indicating that marginalized groups experience worse food security outcomes are not novel, they also suggest that receipt of federal stimulus payments was associated with improved food security outcomes for these groups. Additional work is needed to determine if improvements are directly related to EIP receipt. While this work is limited to the first 3 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, trends observed here likely continued and/or worsened for many disadvantaged Americans. The second wave of the HPS includes data on the SNAP program and could form a basis for analysis of its effect during the pandemic.

Clear disparities in food security across races, ethnicities, and geographic areas are likely connected to structural factors. Therefore, sustained policy reform is needed to ensure that households of all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic status have access to sufficient nutrition. Our results suggest that BIG schemes could help to improve vulnerable groups food security in high-income countries as they have done in lower-income settings [55].

Future work should emphasize the political effects of the stimuli roll out. Previous scholarship has shown that politicians tend to be more responsive in places where people are better informed and more politically active [56]. Hence, the fact that rural individuals in our study tend to be more food insecure could potentially respond to this phenomenon. Furthermore, the electoral effects of the stimuli might be of interest, especially in places with sustained food insecurity [57].

This study contributes to an important adjudication of policy. However, its contribution goes further: the economic stimulus payments were a test of a different kind of redistribution from one currently practiced in the USA. The USA currently redistributes resources to individuals based on a patchwork quilt of means-tested programs targeted at specific services like housing choice vouchers and food stamps. Alternatively, under a Basic Income Guarantee (BIG) scheme, the government would transfer a small amount of cash to individuals unconditionally and obligation-free. Scholars argue that a BIG could be an ethically sound, historically congruent, practically feasible, and economically efficient means of providing a basic floor of quality of life and alleviating inequality [58]. Under a BIG scheme, redistribution from the government would instead find its way to individuals via lump-sum payments that the individuals could use to purchase whatever goods they find necessary. Hence, this study contributes important, albeit specific, evidence for the effectiveness of a lump-sum non-conditional redistribution policy in a high-income country setting.

Author Contribution

MJ performed the data analysis and contributed to the writing and editing of the paper. TMcD and MVC contributed overall idea guidance, wrote content, and edited the paper. MC contributed the overview of relevant literature.

Data Availability

All data is publicly accessible.

Code Availability

Upon request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

N/A, no human subjects.

Consent to Participate

N/A, no human subjects.

Consent for Publication

All authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

This is the source of the US Department of Agriculture’s annual reports.

We acknowledge that the recall periods between both measures are different. However, since we want to control for previous states of food insecurity, this difference does not impede the conceptual validity of the new control.

PSM was performed in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) using Proc Psmatch.

Since the validity of estimates depends largely on deriving a high-quality matched sample, is it important to ensure that the matching technique did not bias analyses. To test the validity of results, we supplement the original two-toone greedy matching with various greedy, nearest neighbor, replacement, and match count conditions. We also adjust the characteristics on which respondents were matched to include the appropriate number and type of characteristics. We also exclude various groups of participants using each of these approaches. We form conclusions under each

additional match specification to ensure that results were not due to group differences or the statistical technique.

(0 = enough of the kinds of food (I/we) wanted to eat, 1=enough, but not always the kinds of food (I/we) wanted to eat, 2=sometimes not enough to eat, and 3=often not enough to eat.

These estimates provide a more intuitive contextualization of the regression results. While OLS is not the best

unbiased estimator for non-continuous dependent variables, its coefficient estimates are straightforward and widely

understood, but the standard errors that accompany these estimates are not considered reliable.

These estimates provide a more intuitive contextualization of the regression results. While OLS is not the best unbiased estimator for non-continuous dependent variables, its coefficient estimates are straightforward and widely understood, but the standard errors that accompany these estimates are not considered reliable.

The average state code is 27.75 (SD = 16.20) in both cohorts, indicating balanced state representation.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.UNICEF. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2020. 2020. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1421967/the-state-of-food-security-and-nutrition-in-the-world-2020/2036027/

- 2.Placzek O. Socio-economic and demographic aspects of food security and nutrition. OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 150, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2021. 10.1787/49d7059f-en

- 3.A. Amankwah, S. Gourlay, A. Zezza, Food security in the face of COVID-19: evidence from Africa, World Bank. (n.d.). https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/food-security-face-covid-19-evidence-africa (accessed October 21, 2022).

- 4.IMF, Managing the impact on households: assessing universal transfers (UT), special series on fiscal policies to respond to COVID-19. (2020). https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/covid19-special-notes/en-special-series-on-covid-19-managing-the-impact-on-households-assessing-universal-transfers.ashx (accessed October 21, 2022).

- 5.Stuff JE, Casey PH, Szeto KL, Gossett JM, Robbins JM, Simpson PM, Connell C, Bogle ML. Household food insecurity is associated with adult health status. J Nutr. 2004;134:2330–2335. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vozoris NT, Tarasuk VS. Household food insufficiency is associated with poorer health. J Nutr. 2003;133:120–126. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinreb L, Wehler C, Perloff J, Scott R, Hosmer D, Sagor L, Gundersen C. Hunger: its impact on children’s health and mental health. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e41 . doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon LB, Winkleby MA, Radimer KL. Dietary intakes and serum nutrients differ between adults from food-insufficient and food-sufficient families: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. J Nutr. 2001;131:1232–1246. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkpatrick SI, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity is associated with nutrient inadequacies among Canadian adults and adolescents. J Nutr. 2008;138:604–612. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.3.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seligman HK, Bindman AB, Vittinghoff E, Kanaya AM, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1018–1023. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140:304–310. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan L, Sherry B, Njai R, Blanck HM. Food insecurity is associated with obesity among US adults in 12 states. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkpatrick SI, McIntyre L, Potestio ML. Child hunger and long-term adverse consequences for health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:754–762. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangini LD, Hayward MD, Zhu Y, Dong Y, Forman MR. Timing of household food insecurity exposures and asthma in a cohort of US school-aged children. BMJ Open. 2019;8:e021683 . doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berbudi A, Rahmadika N, Tjahjadi AI, Ruslami R. Type 2 diabetes and its impact on the immune system. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2020;16:442–449. doi: 10.2174/1573399815666191024085838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milner JJ, Beck MA. The impact of obesity on the immune response to infection. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71:298–306. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reider CA, Chung R-Y, Devarshi PP, Grant RW, Hazels-Mitmesser S. Inadequacy of immune health nutrients: intakes in US adults, the 2005–2016 NHANES. Nutrients. 2020;12:1735. doi: 10.3390/nu12061735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Bialek S, Boundy E, Bowen V, Chow N, Cohn A, Dowling N, Ellington S, Gierke R, Hall A, MacNeil J, Patel P, Peacock G, Pilishvili T, Razzaghi H, Reed N, Ritchey M, Sauber-Schatz E. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) — United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343–346 . doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleman-Jensen A. Household Food Security in the United States in. 2019;2018:47. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coleman-Jensen A. Household Food Security in the United States in. 2020;2019:47. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker RJ, Garacci E, Dawson AZ, Williams JS, Ozieh M, Egede LE. Trends in food insecurity in the United States from 2011–2017: disparities by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and income. Popul Health Manag. 2021;24:496–501. doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walmsley TL, Rose A, Wei D. Impacts on the US macroeconomy of mandatory business closures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl Econ Lett. 2021;28:1293–1300. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2020.1809626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elgin C, Basbug G, Yalman A. Economic policy responses to a pandemic: Developing the COVID-19 economic stimulus index. Covid Economics. 2020;1(3):40–53.

- 25.S. Chakraborty, M.C. Biswas, Impact of COVID-19 on the textile, apparel and fashion manufacturing industry supply chain : case study on a ready-made garment manufacturing industry, Journal of Supply Chain Management, Logistics and Procurement. (2020). https://hstalks.com/article/6059/impact-of-covid-19-on-the-textile-apparel-and-fash/ (accessed October 21, 2022).

- 26.Schanzenbach D, Pitts A. Food insecurity in the census household pulse survey data tables. Institute for Policy Research. 2020;1–15.

- 27.Alvi M, Gupta M. Learning in times of lockdown: how COVID-19 is affecting education and food security in India. Food Sec. 2020;12:793–796. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01065-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfson JA, Leung CW. Food insecurity during COVID-19: an acute crisis with long-term health implications. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:1763–1765. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pryor S, Dietz W. The COVID-19, obesity, and food insecurity syndemic. Curr Obes Rep. 2022;11:70–79. doi: 10.1007/s13679-021-00462-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunningham GB, Wigfall LT. Race, explicit racial attitudes, implicit racial attitudes, and COVID-19 cases and deaths: an analysis of counties in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0242044 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker SR, Farrokhnia RA, Meyer S, Pagel M, Yannelis C. Income, liquidity, and the consumption response to the 2020 economic stimulus payments (No. w27097). National Bureau of Economic Research. 10.3386/w27097

- 32.Coibion O, Gorodnichenko Y, Weber M. How did U.S. consumers use their stimulus payments? NBER Working. Paper, (27693). (2020). 10.3386/w27693.

- 33.Bounie D, Camara Y, Galbraith JW. Consumers’ mobility, expenditure and online-offline substitution response to COVID-19: evidence from French transaction data. SSRN Electron J. (2022). 10.2139/ssrn.3588373

- 34.Chang H-H, Meyerhoefer CD. COVID-19 and the demand for online food shopping services: empirical evidence from Taiwan. Am J Agr Econ. 2021;103:448–465. doi: 10.1111/ajae.12170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chetty R, Friedman JN, Hendren N, Stepner M. The economic impacts of COVID-19: Evidence from a new public database built using private sector data (No. w27431). National Bureau of economic research. (2020). 10.3386/w27431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Internal Revenue Service, Calculating the economic impact payment, (2020). https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/calculating-the-economic-impact-payment (accessed October 21, 2022).

- 37.Morales DX, Morales SA, Beltran TF. Racial/ethnic disparities in household food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationally representative study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8:1300–1314. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00892-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aday S, Aday MS. Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Qual Saf. 2020;4:167–180. doi: 10.1093/fqsafe/fyaa024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Béné C. Resilience of local food systems and links to food security — a review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Sec. 2020;12:805–822. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01076-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.T. Hanspal, A. Weber, J. Wohlfart, Income and wealth shocks and expectations during the COVID-19 pandemic, CESifo Working Paper, 2020. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/216640 (accessed October 21, 2022).

- 41.P. Ozili, T. Arun, Spillover of COVID-19: impact on the global economy, (2020). https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/99850/ (accessed October 21, 2022).

- 42.Amare M, Abay KA, Tiberti L, Chamberlin J. COVID-19 and food security: panel data evidence from Nigeria. Food Policy. 2021;101:102099 . doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bauer L, Pitts A, Ruffini K, Schanzenbach DW. The effect of pandemic EBT on measures of food hardship. Washington, DC.: The Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution; 2020.

- 44.Lauren BN, Silver ER, Faye AS, Rogers AM, Woo-Baidal JA, Ozanne EM, Hur C. Predictors of households at risk for food insecurity in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24:3929–3936. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allcott H, Diamond R, Dubé J-P, Handbury J, Rahkovsky I, Schnell M. Food deserts and the causes of nutritional inequality*. Q J Econ. 2019;134:1793–1844. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjz015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kansiime MK, Tambo JA, Mugambi I, Bundi M, Kara A, Owuor C. COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: findings from a rapid assessment. World Dev. 2021;137:105199 . doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith MD, Rabbitt MP, Coleman-Jensen A. Who are the world’s food insecure? New evidence from the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Insecurity Experience Scale. World Development. 2017;93:402–412. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hobbs JE. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue Canadienne d’agroeconomie. 2020;68:171–176. doi: 10.1111/cjag.12237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valaskova K, Durana P, Adamko P. Changes in consumers’ purchase patterns as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mathematics. 2021;9:1788. doi: 10.3390/math9151788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gangopadhyay S, Lensink R, Yadav B. Cash or in-kind transfers? Evidence from a randomised controlled trial in Delhi, India. J Dev Stud. 2015;51:660–673. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2014.997219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim MJ, Lee S. Can stimulus checks boost an economy under COVID-19? Evidence from South Korea. Int Econ J. 2021;35:1–12. doi: 10.1080/10168737.2020.1864435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.S. Bartlett, J. Klerman, L. Olsho, C. Logan, M. Blocklin, M. Beauregard, A. Enver, P. Wilde, C. Owens, Healthy incentives pilot final evaluation report | Food and Nutrition Service, USDA. (2014). https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/hip/final-evaluation-report (accessed October 21, 2022).