Abstract

The pandemic ‘stay at home’ obligations turned our homes from a place to live to a place to live, work, entertain ourselves and to study. Since March 2020, confinement has had a permanent impact on students’ perception of studying and on academic lifestyle. Most universities continue teaching online, and most academic facilities, such as lecture and seminar halls, student halls, and dormitories, have been abandoned. Some of them form vast areas in cities that play a major role in the urban structure. The authors have examined the degree and way of occupation of the academic infrastructure before and in time of the pandemic. Evidence and data have been gathered from different universities in Poland and Italy. From their origins, academic campuses can be considered autonomous communities within or on the city limits. In a post-pandemic perspective, the evidence shows that the growing population of students does not mean campus development and that the campuses that have shown the greatest resilience are “open” campuses which are able to share, integrate, and exchange their spaces and facilities with those of the city. The authors conclude that the pandemic will have an impact on the future urban form of academic facilities.

Keywords: Post-COVID campus, Academic facilities, Resilient university

Introduction

The university is an ancient concept which, has usually been associated with a particular locus, at a single, fairly homogenous site, or as a collection of buildings in a town or city (Harris-Huemmert 2020). The theme of the campus has characterized the modern history of architectural design due to the analogy it establishes with the meaning of the city, that is, the idea of the urban phenomenon as the foundation of community life from an economic, socio-political, and cultural point of view. Intended as the community in which knowledge economy develops, campuses have often become places of experimentation for social behavior and, more recently, for an eco-sustainable settlement model: “Nonetheless, between the techno-campus and the eco-campus, the university complex intercedes as an instrument of a developmental projection, of a wish to be a future city” (Quintelli 2015).

The prototype of the campuses should be sought in ancient gymnasiums where, in addition to rooms intended for physical culture, there were also exhedra—lecture halls for talks and discussions which evolved into independent buildings (Stavrou 2016). Universities created in Europe were as a merger of different schools, which meant that they operated in the facilities scattered across cities without creating separate districts. The emerging study general gained more autonomy, but medieval academic centers were always associated with the city (Bologna model) or the church (Paris model). The organization of academic life was at various levels, depending on the location, specificity of education, the number of faculties, and the diversity of students (Edwards 2002). The first emerging universities—Bologna 1088, Paris 1100 and Oxford—1167 were organized on the model of monastic schools (as evidenced by the plan of a model monastery school preserved in the St. Gallen monastery) (Büker 2020; Busse 2015). The first modern universities whose name—the academy—derives from the ancient Plato school established in the Akademos grove (Eliopoulos 2015), were already much more developed institutions. Their social impact was even greater as their buildings, which had various functions (lecture halls, libraries, lecturers’ apartments, and student dormitories), occupied entire quarters in the urban fabric. The Krakow Collegium Maius (1364), the oldest part of the University of Krakow, was created by joining two buildings w.Jagiellońskaand several neighboring houses. After the fires, they were combined into a harmonious whole surrounding the cloister courtyard (Matelski and Chwalba 2010).

One of the most famous attempts to autonomously organize the space of a student campus is the Bauhaus space in Dessau. Buildings located on the left bank of the Elbe River were built there in 1925–32. Wünsche (1989) writes, attempts to organize student life in a specific, but limited space, were globally successful, but they were met with initial scepticism and doubts among contemporaries. In fact, during the last century, universities migrated out of town to seek a better future in the open landscape (Hebbert 2018). The architecture from the whole to the parts and from the parts to the whole reflected the l’esprit nouveau (the new spirit) or the Zeitgeist (spirit of the age) of the technological age and functionalism for which the modern movement stood for (Abimbola and Babatunde 2016). The discussion on the relationship between the campus and the city is well recognized among the academics (e.g., Hebbert 2018; Way 2016; Peker and Ataöv 2020). The effect of the knowledge economy is to break down the conventional boundaries between campus and city. Campuses also have the potential to be at the forefront of inspiring, flexible environments. In recent years, many universities have attempted to institutionalize the concept of sustainable development by incorporating it into the curriculum, research agendas, infrastructure, administration, and operations (Bradecki et al. 2022). In the latest developments, the two may be as intermixed as they were in the oldest urban universities (Hebbert 2018). That statement applies to university campus architectural, structural (Friedman 2005), and phenomenological dimensions. Most of the research on university campuses discusses mostly architectural and urban features: in Poland (Żabicki 2021, Kapecki 2015, 2020) and in Italy (De Carlo 1968; Coppola and Pignatelli 1969; Canella and D’Angiolino 1989; Controspazio 1989). University campuses must not only provide an environment for studying, but also one that promotes physical and mental health (Ming and Fu 2019; Winnicka-Jasłowska 2012). Universities require more versatile individual spaces, as well as clusters of facilities offering a variety of options for students to work in different ways, and which also increase the ability for teachers to adopt different instructional approaches (Jamieson 2003). That refers to development of ICT technologies and meets the proposal of Janne Corneil and Philip Parsons that we should aim to make the boundary between the university and the city at least porous, at best non-existent (2007). Nowadays, campus environments are park-like spaces, which include diverse landscape types that can be categorized as natural or artificial in general (Lu and Fu 2019).

During the Coronavirus pandemic, city life has undergone profound changes and citizens have adopted new ways of using space. Since March 2020, the reality of the limited flexibility of existing systems of teaching was immediately acknowledged by the closure of physical facilities and the subsequent migration to online teaching (Ilisko et al. 2021). Currently, we can observe the lack of knowledge of how contemporary European urban societies should deal with the restrictions caused by the epidemic and in what way urban structures could facilitate behavior that slows down the transmission of the disease (Mironowicz et al. 2021).

Physical distancing has strongly affected the daily life of citizens, and its consequences vary depending on the part of the city: the most crowded neighborhoods, with a lack of adequate public transport and widespread public and proven local services have been negatively affected. This brings up the question of the fundamental relationship between architecture and public health (Scala and Grazia 2020) urban form and social behavior. Legeby and Koch (2021) conducted a web questionnaire (PPGIS) in three Swedish cities: Stockholm, Uppsala, and Gothenburg. Respondents were asked to describe how their habits have changed, indicating on a map the places they continue to frequent and those they have begun to avoid and adding information on the activities they carry out there. The results of the questionnaire indicated that social groups with fewer resources are directly dependent on public services and facilities and especially on those located near their homes. Cruz-Rodriguez et al. (2020) conducted a research on student mobility behavior and means of transportation used by students in their transportation to the university. They conclude that in post-pandemic conditions, the perception of public transportation as unhealthy can gain ground and remain (Cruz-Rodriguez et al. 2020).

In 2020 a revolution occurred, online education has become a prerequisite for university education (Shunya 2020), and teaching was conducted only with ICT technologies, and so the university campus became a virtual instead of a physical place for students and teachers. The vehicle, bicycle, and pedestrian traffic on campuses decreased, while online traffic drastically increased (Favale et al. 2020). Temporary reuses and reversible interventions, capable of the urban system to pandemic risk management (Berlingieri and Triggianese 2020). The ICT discourse in education has been so widespread that many believe it might potentially lead to ‘a fundamental shift’—the shift from conventional university education to lifelong learning enabling learners to access higher education based on online content regardless of time and place (Peters et al. 2020). However, the limitations of ICT use in education cannot be overlooked (Pedro-Caranana 2020). Some researchers try to compare and use/incorporate the idea of smart city to smart university (Fortes et al. 2019; William et al. 2019). Min-Allah and Alrashed (2020) state that smart campus is an emerging trend that allows educational institutions to combine smart technologies with physical infrastructure for improved services, decision making, campus sustainability. Dong et al. (2016) propose a mobile platform that would perform some of the smart campus functions. Although there is evidence on good performance and effects of distance, online learning (Clark et al. 2020), we must remember that continuous online education had an impact on academic health (Wahid et al. 2020), and the stress level has increased (Demetriou et al. 2021), so the on-site experience is crucial in the wider image of academic education. Eirdosh and Hanisch (2021) wrote, it is impossible to define which factor is the most important one in optimizing on-site learning in the pandemic era. Pandemic created an opportunity to assess education infrastructure in real time as part of on-going crisis management (Iliško et al. 2021). For some universities in many countries, mass transition to distance learning became a challenge in Ukraine (Grynyuk et al. 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic offers us the opportunity to rethink not only new digital, online, and pedagogical possibilities but also the basic purposes of education (Choo et al. 2020). Samoylenko et al. (2020) indicate the role of teachers in future education, and show that COVID-19 has had even more impact on the way that teachers would have to improve in modern age in 3 components: teacher as personality, as a specialist, and as a professional.

This paper is structured as follows. Authors present the methodology and the data that have been gathered. The substantiation and classification of the case studies have also been presented. The quantitative approach and spatial recognition have been used to indicate and compare four different campuses before and after pandemia. Since research showed changes in the use of academic facilities, authors argue that the pandemic will have an impact on the future of academic campuses’ structure in the cities.

Methodology

The aim of our study was to document the impact of the pandemic on academic facilities and the way they were used in time of the pandemic. Observations were made in three different universities in Italy and Poland, which are structurally different. Data on pandemic restrictions from March 2020 until June 2021 and their effects were collected. Furthermore, data on the occupation of campus facilities since 2018 have been compared. Comparative quantitative analysis has been carried out to diagnose the impact of the pandemic.

Following data have been researched: cities total area, university campus structure, location, and its connections with the city, distance to the city center, number of inhabitants, number of students, number of bedrooms in dormitories, occupancy of university buildings’ dormitories, academic public spaces, campus-like premises, and campus area. Observations have been made to comment on the effects of abandonment of academic sites. The use of academic premises and academic activities (way of use, number of users) were compared before and after pandemia. Data have been collected from universities management offices. Also findings from observation of various locations in the universities have been reported, and some of the spatial phenomena have been illustrated before/after pandemia. Four case studies have been chosen: University of Bologna (UNIBO) in the city of Bologna and campus in Cesena, Silesian University of Technology (SUT), campus in Gliwice, Katowice University of Technology (KUT), Katowice. All represent diverse kinds of universities which can be classified as follows: multicampus (Bologna), campus-like (Gliwice), noncampus-like, and scattered (Bologna, Katowice). Following criteria: spatial differentiation, size of the university, access to data and location in the city have been considered.

Overview of the case studies

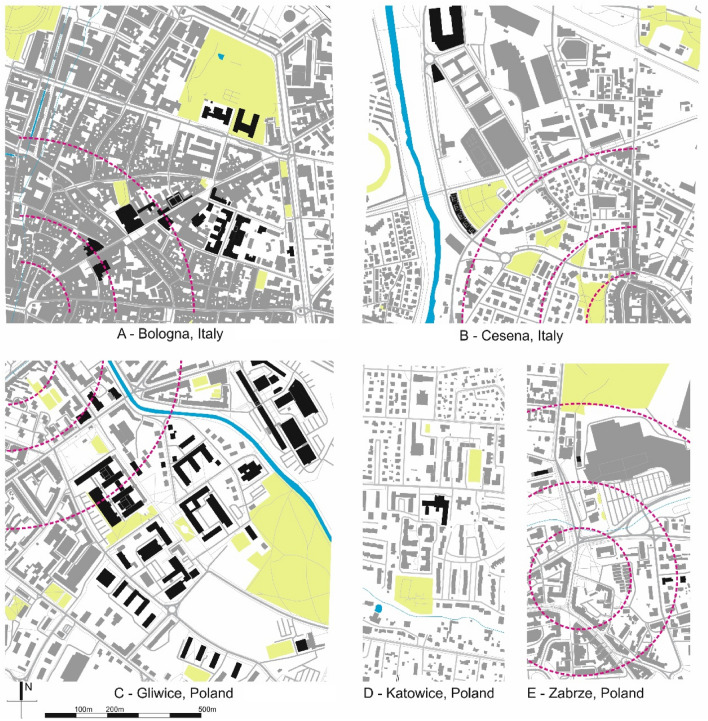

The University of Bologna has a long tradition, and it was established in medieval times on the spontaneous initiative of a group of wealthy students precisely in conjunction with the birth of the municipality as a city republic. Today, the UNIBO provides a multicampus organization, which is divided into the offices of Bologna, Cesena, Forli, Ravenna, and Rimini for a total of 2854 teachers and researchers, 2946 technical-administrative staff, and a community of over 87,000 students. The oldest university buildings in Bologna are spread all over the city and most of them are used as headquarters of Faculties. In Bologna, the university hosts more than 60,000 people and provides courses to 56,900 students. Although there is no campus-like infrastructure, Bologna can be presumed as an academic center with well-recognized public spaces (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Location of campus facilities (in black) in the plan of the city, location of the major green spaces (light green) and location of the city center: distance 100, 200, 500 m (radial dotted line): a Bologna throughout, b Cesena, c Gliwice, d Katowice, e Zabrze

The campus in Cesena was established in 1999 as a masterplanned area, and it was planned to be developed further (Fig. 1b). The Cesena campus hosts 1500 students, 200 professors and researchers of architecture, psychology, agri-food sciences and Technologies, Computer Science and electrical energy and Information Engineering, and is organized in Headquarters Organizational Units (US). The campus has numerous services: a 196-seat central campus library, 2112-seat study rooms, 8 computer labs, 38 teaching rooms, a student residence with 22 beds, with further 133 beds in partner residences and accommodations, and 2 refreshment points.

The reported numbers have been reduced by 50% due to the pandemic, with introduction of blended teaching to the highest possible degree. The desolation that followed the abandonment of campus spaces and public services by students raises at least one fundamental question that brings us back to the analogy between the university campus and the city: the inversely proportional relationship between phenomena of alienation and accessibility to services and the usefulness and necessity of the public and collective dimension of life. Students forced into distance learning have had to do without not only services but have had to give up the bonds that transform individual choices into collective projects and actions, exacerbating the darker conclusions of Bauman’s liquid modernity (Bauman 2000).

The Silesian University of Technology was established in 1945 in Gliwice Poland. Since 1984, some of the faculties of the Faculties have been located in other cities: Dąbrowa Górnicza, Katowice, Zabrze, and Rybnik. Today (2021), SUT holds 18,000 students on 15 Faculties and Institutes with 1630 academic teachers and approximately. 1370 non-academic staff. The campus in Gliwice was consistently planned and most of the academic facilities were located in one site along the Akademicka street (Fig. 1c). In 2013, the street was successfully turned into pedestrian public space with squares, gardens, and fountains (Bradecki 2017). Before the pandemic, the academic campus in Gliwice hosted daily ca. 8000 academics and occasionally over 10,000 people during the IGRY students’ event.

The Katowice University of Technology was established in 2003 in the city of Katowice (Fig. 1d), and it holds 2800 students on 2 faculties with approximately 50 of academic teachers and 25 administrative staff. Since 2012, the media department in Zabrze was established (currently medical and nursing faculties) (Fig. 1e). For this purpose, one of the buildings in the immediate vicinity of the city center, Theater Square, was renovated. Due to the growing number of students, plans for the renovation of another historical building in the city center were prepared. In 2019, the university was preparing to buy 3 buildings to create dormitories. The COVID pandemic and the uncertain future of stationary education meant that the university ceased activities leading to the creation of a campus in the city of Zabrze.

Analysis of the data

Firstly, the analysis of the size, scale, and relation to the city has been prepared (Table 1). The campus area is usually perceived as a space for academics. The presented case studies demonstrate that it is difficult to set the borderline of the campus area, and public spaces usually used by students are very often used also by the citizens. Since the university is often perceived as buildings with adjacent spaces, the campus’ area land-use structure has been presented (built-up areas, green spaces and other spaces paving, unused etc.). This turned out to be problematic in cases of SUT (large area, complicated structure) and UNIBO Bologna(spread across the city). Green areas in the campuses were indicated, and the distance to adjacent public parks has been showed, since many researchers argued that greenery is important in campuses. Also, the laws and regulations of different universities have been compared. Although the rules were different in most universities (Table 2), the practice was that most classes were conducted online, and laboratories were on-site held only on several occasions. Data on the campus occupation has been gathered from semesters 2018/2019 and 2020/2021 (Table 3). The total number of students decreased, but this change cannot be strictly connected with pandemic. The SUT case study shows that the number of students was the same in 2019 as in 1975 and 1995. Dormitories were occupied by 100% before and ca. 20% during the pandemic. The highest impact of the pandemic can be observed in international exchange programs. According to the report of Polish Rectors (2020), fewer students decide to apply for international exchange programs, and in some cases, this leads to financial troubles, since in many cases, foreign students are a source of income. In Cesena, the dormitories were occupied only by Italian students while foreign students were blocked by the lockdown.

Table 1.

Comparison of data on academic facilities in cities—general overview

| SUT Gliwice | KUT Katowice, Zabrze | Cesena campus | Bologna campus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of inhabitants | 177,000 | 302,000, 190,000 | 97,000 | 390,000 |

| City area | 133.8 km2 |

164.7 km2—Katowice, 80.4 km2 Zabrze |

249.5 km2 | 140.9 km2 |

| Campus area | ~ 340,000 sqm | 990 sqm, 0 | 30.750 sqm | Campus spread across the city |

| Campus area land-use structure |

Built up space 25% Green space 40% Other 35% |

Built up space 50%/ Green space 1%/ Other 49%/ |

Built up space 20% Green space 20% Other 60% |

Campus buildings and adjacent spaces spread across the city |

| Time of walk to the city center, distance |

815 min., 500–1000 m |

59 min., 4900 m—Katowice 3 min., 300 m—Zabrze |

20 min., 1600 m | 9–20 min.- 700–1600 m |

| Time of walk to the major green area (park), distance |

5–8 min., 300–500 m, Chrobry Park |

17 min., 1400 m Katowicki Park Leśny, 2 min., 160 m, Park Hutniczy Zabrze |

13 min. 1000 m Parco urbano dell podromo |

Small random parks and green areas spread across the city |

| Public space area/open space volume in campus | Parks, paths, squares open to citizens, ~ 25,000 sqm/7% | Front entrance square ~ 250 sqm/25% | 9200 sqm/30% | Public spaces of the city |

Table 2.

Academic ‘covid’ rules and regulations, method of education in academic facilities and during semester 2020/2021

| SUT, Gliwice | KUT Katowice, Zabrze | UNIBO Cesena, Bologna | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lectures | Online | Online | Online |

| Seminars | Online | Online | Online |

| Laboratory | On-site, provided a laboratory class cannot be organized online and hygienic precautions were enabled, e.g., capacity of the laboratory reduced to 50% | Online/on-site for the faculty of medicine: Hygienic precautions were enabled, e.g., capacity of the laboratory reduced to 50% | Blended mode. Students could follow from home or book and come to the laboratory with a capacity reduced by 50% |

| Common rules | Students cannot enter the facilities; academics work at home, and enter the facilities if there is a need | Students can enter the facility to conduct online education in special rooms, some of the laboratories, exams were conducted on-site | Students cannot enter the facilities; academics work at home, and enter the facilities if there is a need |

| Academic staff meetings | Online, on-site in exceptional situations | ||

| Dormitories | Some of the buildings were prepared as COVID hospitalization venues, and students who stayed were moved to other buildings | – | Italian students have returned home, foreign students have spent the lockdown in university residences |

Table 3.

Comparison of data on academic facilities in campuses in semester 2018/2019 (before the pandemic) and semester 2020/2021

| SUT Gliwice | KUT Katowice, Zabrze | UNIBO Cesena | UNIBO Bologna | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018/2019 | No. of students | 18,106 | 1059, 395 | 5987 | 51,000 |

| No. of beds in dormitories/percentage of use | 2016/92% | – | 155 | 1600 | |

| Average number of people on campus daily | 8000 | 0.0 | 3000 | All students | |

| No. of academic staff/technical staff | 1711/1567 | 50/25 | 302 | 4635 | |

| No. of open commercial places (cafés, copy shops) | 20 | 2 | 3 | All the city | |

| 2020/2021 | No. of students | 17,596 | 1059, 395 | 6250 | 56,917 |

| No. of beds in dormitories/percentage of use | 1896/52% | – | 130 | 800 | |

| Average number of people on a campus daily | ~ 400 | 0.0 | 300 | 3.000 | |

| No. of academic staff/technical staff | 1711/1567 | 395 | 302 | 4635 | |

| No. of commercial places (cafés, copy shops) | ~ 7 | 0 | 1 |

Some data cannot be gathered or the COVID restrictions cannot be considered as the only reason for changes. Only laboratories and crucial activities were conducted within academic facilities. Most universities have adjacent car and bike parking lots. It has been observed that most of the parking lots were not used and grass grew on the sidewalk (Gliwice, Katowice). Commercial places (cafés, copy shops, bookstores) were closed, and only a few were occasionally open (Gliwice). The collected data show that dormitories were used in 90–100% before the pandemic, while only in 50% during the full pandemic semester. Despite this, the paradox of this condition is that, in many cases, the number of new students enrolled has increased by up to 10% (Unibomagazine 2020). In this way, the presence of students, teachers, and technical staff in the Campus structures has drastically decreased by 90%.

There are also some beneficial consequences of lockdown to health; for example, many urban areas have experienced significant reductions in air pollution, noise pollution, traffic congestion, and crime, while also seeing increases in active travel, such as walking/cycling (particularly for people who would not normally undertake these activities) and a re-awakening of attitudes towards nature in cities (Rice 2020).

Findings

Some of the public spaces have been transformed and academic infrastructure was used in a non-typical way. In Bologna, the Rock, Cultural Heritage leading urban futures project, transformed some public spaces in the city into green spaces to mitigate the heat islands typical of stone-paved historical centers and make the city more liveable during lockdown (Fig. 2). A circus-like tent was set up in the internal courtyard of the Cesena campus (Fig. 3) to allow the few remaining students to eat while sheltered from the rain, after the anti-COVID measures had resulted in closure of the lunch space in the internal rooms. The main public square located in the center of the campus and on the main paths to the city remained mostly empty during pandemia, while it has been occupied by various users in non-pandemic time (Fig. 4). At the SUT, an ice-skating rink has been turned to a clinic (vaccination point) for the city of Gliwice (Fig. 5). In June 2021, an itinerary exam for new candidates for the Faculty of Architecture was organized in a sports gym to provide social distancing (Fig. 6.). In all case studies, a different number of people near the front entrance were spotted (Fig. 7). Most of the parking remained unused during pandemia, and in some cases, vegetation grew on the pavement (Fig. 8). In spring of 2021, some courses at universities were conducted in a ‘blended’ mode which usually means teaching on-site and online at the same time. That led to misunderstandings and complications. On some occasions, students did not appear at all or only a few of them took part in a laboratory class, while others were online (Fig. 9).

Fig. 2.

Bologna: re-use of representative public spaces, students putting new lawn in the historical city center (Via Zamboni); source https://da.unibo.it/it/ricerca/progetti-di-ricerca/progetti-in-ambito-internazionale/rock

Fig. 3.

Cesena campus and the internal court: before (10.2018) and in the time of pandemic (2021), a heated space was set up in the courtyard to allow students to eat outside; authors’ photo

Fig. 4.

SUT, Gliwice Akademicka Street, main public square and in time of the pandemic (05.2021) and after (05.2022); authors’ photo

Fig. 5.

Ice arena converted to vaccination point for the citizens of Gliwice, SUT (04.2021); authors’ photo

Fig. 6.

Architectural drawing skill test in a sports gym (06.2021), vacant parking during pandemia (05.2021) Gliwice, SUT; authors’ photo

Fig. 7.

KUT, Katowice, Rolna street, open square next to the main entrance to the university before (05.2019) and during pandemia (05.2021); authors’ photo

Fig. 8.

KUT, Katowice, occupied car parking next to the university before 05.2019 and vacant car parking with vegetation in the pavement during pandemia 05.2021; authors’ photo

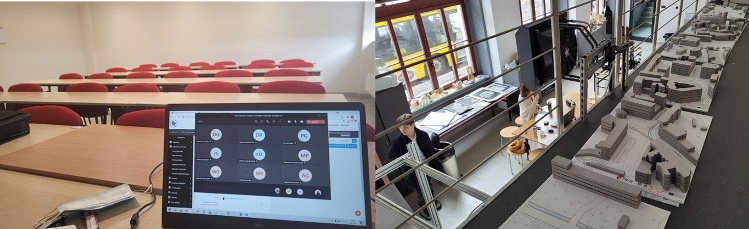

Fig. 9.

Blended classes (on-site & online): all students online and no students on-site at KUT, 05.2021, blended laboratory at SUT, model making requires facility equipment (3D plotter): 4 students on-site and 10 online preparing the models with a live camera, 05.2021; authors’ photo

The conclusions of the findings can be described below. The impact of pandemia has been observed in academic facilities: most of the academic spaces were unused, common gatherings, student events were not organized, common public spaces open to citizens were only used occasionally. On some occasions, academic facilities have been converted to temporary use for students (new objects: tents) and/or local society (change of use: vaccination point in skating arena, public examination in the sports arena). In 2021 during the summer and fall, restrictions have been eased and some spaces started to be used again. Comparison of data from all universities showed lower expenses on facilities’ maintenance and on travel (most of events: conferences, large seminars were held online).

Until now, there has been too little data to predict the impact of the pandemic on education. Based on the observations of the authors, after March 2019, the academic facilities and public spaces have been used by students only occasionally. For example, Akademicka street, Gliwice, the SUT campus was used mostly by walking citizens. The academic premises (copy shops, cafeterias, bars) were either closed or open occasionally. Both owners of the businesses and universities noted a loss in income. In the case of SUT in Gliwice, most of the campus facilities were only used only occasionally. This brings us to the recommendation that more mixed use with active frontage open to the city would be helpful in attracting more non-academic users and make the campus more resilient.

Discussion

Universities plan to continue distance learning, regardless of whether pandemic restrictions will be required. Since semester 2021/2022, SUT has conducted all lectures in ‘blended’ mode to provide lectures on-site with simultaneous online transmission. Lectures would be blocked to provide ‘home lecture days’ for students, which allows them not to visit the campus on some days. Since lectures can be estimated to comprise 30% of the academic education, we can estimate that the campus might be less attended in the post-COVID era. Also, less traffic can be predicted and more various sustainable means of transport are being considered as sustainable and helpful for the post-COVID university (Cruz-Rodriguez et al. 2020). The authors foresee that, in some cases, academic campus areas might be abandoned in the future if distance learning stays for the future. The public spaces in campuses that are not connected with the city are more likely to be vacant than any other because of lack of users.

The need to be able to use local services without having to use public transport fits perfectly with the type of city that Richard Sennet (2013) defines as an “open city” and which he identifies with the model of the medium-sized European city. Sennet’s ‘open city’ has little to do with the idea of a generic city or the liquid modernity feared by Bauman (2000). By “open city,” we mean a city open to social interaction and this opening is made possible precisely by the mixture of residences and services, that is the mixture of different social groups in the same neighborhood, which is the exact opposite of the phenomenon of gentrification and of functional specialization. What Sennet fears most of all is what he calls functional overdetermination and overspecification (Sennet 1977). A similar idea can also be applied to homes. Luca Reale writes “At this point, the design themes for architects appear very evident: on the scale of private living, there is a need to leave great organizational freedom of space, even going beyond the rhetoric of flexibility and concentrating action on co-responsibility of choices by users up to nonallocation of space, technological and network efficiency, temporary division of spaces, recovery of privacy in the home even in the presence of remote school and working.’ (Reale 2020).

In 1988, on the 9th Centenary of the University of Bologna, a document was drawn up—the Magna Charta Universitatum—aimed at defining and affirming the main constitutive values of university institutions: institutional autonomy, academic freedom, but also international collaboration and social responsibility. The Observatory of the Magna Carta recently organized two webinars entitled ‘What lessons are we learning from Covid 19?’ (September 2020) and ‘Fostering sustainable development: the role of higher education—plans, progress, and values” (December 2020). Both webinars seem to spark ideas about the future of college campuses. On the one hand, the idea that the social responsibility of campuses concerns not only university education, but also lifelong learning education and the opening of campus facilities and services to the city. On the other hand, campuses can open up to the city and are configured as real examples of good practices for sustainable environmental and energy development.

The pandemic has accelerated the prophecy of Michel Serres (2012)—knowledge “has escaped beyond the limits of the educational institutions”—and has questioned the distinction between institutional places of learning (the school, the classroom, the laboratory, etc.) and places that favor an informal learning process such as one’s home and public spaces. Rafael López-Toribio (2015) writes: ‘Colleges have to redefine their role, not only as informal education, but as spaces capable of attracting synergies that provide new teaching and learning methods. Colleges no longer have the exclusive rights on the educational process. That means that colleges would now be centrality nodes in a learning network dissolved in the city itself; spaces of meeting and relationship between individuals.’ This discourse can also be reversed: not only can learning places include private places and public spaces, but public spaces and public utility services also can extend to the facilities and services of university campuses.

Conclusions

Research shows that comparative, quantitative analysis is not always sufficient to show the role of campus in cities’ structure. The pandemic period showed that teaching and studying can be conducted with almost abandoned academic facilities. The SUT case study with its large campus area showed that nearly 10.000 students (5% of the Gliwice population) did not using the space which is located in the center. Among presented case studies, only SUT campus offered green space for citizens, which were occasionally used in the time of pandemia and is often used daily. This shows that green spaces should be part of academic infrastructure and local parks are not sufficient, especially if located too far. The types of universities (multicampus, campus, scattered campus) show that the use of the academic campus has proven to be challenging in the time of the pandemic and will have to face changes in the future. These considerations on the relationship between individuals and forms of living, i.e., between urban form and social behaviors, bring us back to the role of campus structures within cities and more generally to the role and perspective of the urban phenomenon in the post-pandemic reality. How is the city of the present–future to be imagined if it is true that the urban form can influence social behavior? It is often said that the city will have to rethink the proxemics between bodies and space and provide a greater expansion of spaces, abandoning the concentration and density typical of the historic city. There are characteristics of the historic city that appear to us as a coherent and appropriate solution to the critical issues highlighted above: for example, accessibility to services finds an optimal solution in the functional mixité typical of the historic city.

Certainly, the city-campus reciprocity works best when the campus is not an isolated place located in a peripheral environment but is an urban campus or a widespread campus within the city. In this case, the buildings and premises of the campus naturally fit into the fabric of the city and their availability for civic use. The idea of smart campus, which can be associated with modern ICT technologies, has been tested in ways different from expected. We can assume that future fusion of technology and new post-COVID academic lifestyle (blended studying) can lead to new spatial solutions.

To conclude, moments of crisis and difficulty can become the catalysts for virtuous changes of direction. These changes in direction must associate the fate of the campuses with that of the cities in which they are located and favor a mutual integration of structures and services. Just as education must be made available to all for life, so the facilities and services of university campuses must be made available to the city and open to the use of citizens. Future research on use of academic facilities and its connections with the city is needed since some of the data are not revealed. In 2022, universities started to operate on-site, but some will not conduct education in the traditional way and this has an impact on academic spaces.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lamberto Amistadi, Email: lamberto.amistadi@unibo.it.

Tomasz Bradecki, Email: tomasz.bradecki@polsl.pl.

Barbara Uherek-Bradecka, Email: barbara.bradecka@wst.com.pl.

References

- Abimbola OA, Babatunde EJ. Modernism and cultural expression in university campus design: The Nigerian example. Archnet-IJAR. 2016;10(3):21–35. doi: 10.26687/archnet-ijar.v10i3.1102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman Z. Liquid modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Berlingieri, F., and M. Triggianese. 2020. Post-pandemic and urban morphology. Preliminary research perspectives about spatial impacts on public realm.FAMagazine 52–53. 10.12838/fam/issn2039-0491/n52-53-2020/537.

- Bradecki T. 2017. Wielkie inwestycje w przestrzeni publicznej na przykładzie ulicy Akademickiej w Gliwicach, ed. T. Bradecki, and K. Gasidło. Wielkie inwestycje publiczne w miastach aglomeracji. Silesian University of Technology, 23–33.

- Bradecki T, Hallova A, Stangel M. Concretization of sustainable urban design education in the project based learning approach—experiences from a fulbright specialist project. Sustainability. 2022;14(12):6971. doi: 10.3390/su14126971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Büker D. In neuem Licht—Der Klosterplan von St. Gallen. 2020 doi: 10.3726/b17608ISBN:9783631835944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busse R. St. Gallen als Bezugsrahmen. Sozialwirtschaft. 2015;25(2):22–25. doi: 10.5771/1613-0707-2015-2-22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canella G., and L.S. D’Angiolini. 1975. Università, Ragione, Contesto, Tipo. Bari.

- Controspazio. 1989. Rivista bimestrale di architettura e urbanistica, No. 5/1989.

- Choo S, Apple M, Stone L, Tierney R, Tesar M, Besley T, Misiaszek L. Reimagining the new pedagogical possibilities for universities post-Covid-19. Educational Philosophy and Theory. 2020 doi: 10.1080/00131857.2020.1777655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Nong H, Zhu H, Zhu R. Compensating for academic loss: Online learning and student performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Economic Review. 2021;68:101629. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola P, Pignatelli A. L’università in espansione. Orientamenti Dell’edilizia Universitaria. Milano: Etas Kompass; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Corneil J, Parsons P. The contribution of campus design to the knowledge society: an international perspective. In: Hoeger K, Christiaanse K, editors. Campus and the City—Urban design for the knowledge society. Zurich: GTA Verlag; 2007. pp. 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Rodriguez J, Luque-Sendra A, Heras A, Zamora-Polo F. Analysis of interurban mobility in university students: Motivation and ecological impact. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(24):9348. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo G, editor. Pianificazione e disegno delle università. Roma: Edizioni universitarie italiane; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou L, Hadjicharalambous D, Keramioti L. Examining the relationship between distance learning processes and university students’ anxiety in times of crisis. European Journal of Social Sciences Studies. 2021;6(2):123–141. doi: 10.46827/ejsss.v6i2.1012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Kong X, Zhang F, Chen Z, Kang J. On campus: A mobile platform towards a smart campus. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):974. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2608-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S. 2002. A woman is wise: The influence of civic and christian humanism on the education of women in Northern Italy and England during the renaissance.Ex Post Facto: Journal of the History Students at San Fransisco State University 11.

- Eirdosh D, Hanisch S. Evolving schools in a post-pandemic context. In: Filho WL, editor. COVID-19: Paving the way for a more sustainable world. World sustainability series. Cham: Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eliopoulos T. 2015. New evidence on the early Helladic ‘House of Akademos’ in Plato’s Academy, July 2020. 10.2307/j.ctv15vwjjg.44; Athens and Attica in Prehistory: Proceedings of the International Conference, Athens, 27–31 May 2015.

- Favale T, Soro F, Trevisan M, Drago I, Mellia M. Campus traffic and e-Learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Computer Networks. 2020;176:107290. doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2020.107290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortes S, Santoyo-Ramón JA, Palacios A, Baena D, Mora-García E, Medina M, Mora P, Barco R. The Campus as a Smart City: University of Málaga environmental, learning, and research approaches. Sensors. 2019;19(6):1349. doi: 10.3390/s19061349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, D. 2005. Campus design as critical practice. Places Journal, Considering the Place of Campus 17(1).

- Grynyuk S., A. Zasluzhena, I. Zaytseva, and I. Liahina. 2020. Higher education of Ukraine plagued by the covid-19 pandemic, November 2020, DOI: 10.21125/iceri.2020.0667, Conference: 13th annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation.

- Harris-Huemmert, S. 2020. Concepts of campus design and estate management: Case studies from the United Kingdom and Switzerland. Beiträge zur Hochschulforschung, 41. Jahrgang, 1/2019, 24–49.

- Hebbert M. The campus and the city: A design revolution explained. Journal of Urban Design. 2018;23(6):883–897. doi: 10.1080/13574809.2018.1518710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iliško D, Venkatesan M, Price E. Sustainable crises management in education during COVID-19. Paving the Way for a More Sustainable World. 2021 doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-69284-1_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson P. Designing more effective on-campus teaching and learning spaces: A role for academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development. 2003;8(1–2):119–133. doi: 10.1080/1360144042000277991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapecki T. O architekturze szkół wyższych w Polsce na początku XXI wieku. Cracow: Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kapecki T. Architecture of higher education institutions in Poland. Contemporary trends in the design of academic campuses. Prace Geograficzne. 2020;162:13–30. doi: 10.4467/20833113PG.20.010.13097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Legeby A., Koch D. 2021. The changing of urban habits during the Corona 198 pandemic in Sweden Festival dell'Architettura Magazine. 52–53: 198–203. 10.1283/fam/issn2039-0491/n52-2020/493

- López-Toribio R. Social spaces of learning. The case of ETSA in Granada. FAMagazine. 2015;6(34):66–74. doi: 10.12838/issn.20390491/n34.2015/5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Fu J. 2019. Attention restoration space on a university campus: Exploring restorative campus design based on environmental preferences of students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 16(14): 2629. 10.3390/ijerph16142629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Matelski D., Chwalba A. (2010), Dzieje Collegium Maius. In Studia z historii społeczno-gospodarczej ed. W. Pu, and J. Kita, vol. VIII.

- Min-Allah N, Alrashed S. Smart campus—A sketch. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2020;59:102231. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming L, Fu J. Attention restoration space on a university campus: Exploring restorative campus design based on environmental preferences of students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16:2629. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironowicz I, Netsch S, Geppert A. Space and spatial practices in times of confinement. Evidence from three European countries: Austria, France, and Poland. Urban Design International. 2021;26(4):348–369. doi: 10.1057/s41289-021-00158-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pedro-Carañana, J. 2020. Post-pandemic university, or post-university? https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/post-pandemic-university-or-post-university.

- Peker E, Ataöv A. Exploring the ways in which campus open space design influences students’ learning experiences. Landscape Research. 2020;45(3):310–326. doi: 10.1080/01426397.2019.1622661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MA, Rizvi F, McCulloch G, Gibbs P, Gorur R, Hong M, Hwang Y, Zipin L, Brennan M, Robertson S, Quay J, Malbon J, Taglietti D, Barnett R, Chengbing W, McLaren P, Apple R, Papastephanou M, Burbules N, Jackson L, Jalote P, Kalantzis M, Cope B, Fataar A, Conroy J, Misiaszek G, Biesta G, Jandrić P, Choo S, Apple M, Stone L, Tierney R, Tesar M, Besley T, Misiaszek L. Reimagining the new pedagogical possibilities for universities post-Covid-19. EPAT Collective Project. 2020 doi: 10.1080/00131857.2020.1777655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintelli C. Campus and City. The Mastercampus Project. FAMagazine. 2015;6(34):10–18. doi: 10.12838/issn.20390491/n34.2015/1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reale L. Bodies and spaces in the public city. Towards a new proxy? FAMagazine. 2020 doi: 10.12838/fam/issn2039-0491/n52-53-2020/500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Report: INTERNACJONALIZACJA w czasach pandemii. Wpływ COVID-19 na studentów zagranicznych w Polsce i rekrutację na studia w roku akad. 2020/21. The Conference of Rectors of Academic Schools in Poland (CRASP),‘Perspektywy’ education foundation https://www.krasp.org.pl/resources/upload/Inne_dokumenty_KRASP/Koronawirus-Kominikaty/Raport-umiedzynarodowienie-w-czasie-pandemii-Perspektywy.pdf.

- Rice L. After Covid-19: Urban design as spatial medicine. Urban Design International. 2020 doi: 10.1057/s41289-020-00142-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samoylenko NB, Zharko LN, Georgiadi AA. Teacher’s professional image: Reimagining the future. SHS Web of Conferences. 2020;87(1):00063. doi: 10.1051/shsconf/20208700063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scala P, Grazia P. Elastic places and intermediate design. FAMagazine. 2020 doi: 10.12838/fam/issn2039-0491/n52-53-2020/501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sennet R. The fall of the public man. 1. London: Penguin Books; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sennet R. 2013. The Open City. Graduate School of Design, Harvard University. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eEx1apBAS9A.

- Serres M. 2012. Pulgarcita, Manifiestos le Pommier, de la Academia Francesa, París.

- Shunya Y. Online university, pandemics and the long history of globalization. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 2020;21(4):636–644. doi: 10.1080/14649373.2020.1832306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stavrou D. 2016. The gymnasion in the hellenistic East: Motives, divergences and networks of contacts, PhD thesis: School of Archeology and Ancient History, University of Leicester. https://leicester.figshare.com/account/articles/10244777.

- University of Bologna. Social Responsibility Report 2020: https://www.unibo.it/en/university/who-we-are/Social-Responsibility-Report/copy_of_social-Responsibility-report.

- Wahid R, Pribadi F, Wakas E. Digital activism: Covid-19 effects in campus learning. Budapest International Research and Critics in Linguistics and Education (BirLE) Journal. 2020;3(3):1336–1342. doi: 10.33258/birle.v3i3.1174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Way T. The urban university’s hybrid campus. Journal of Landscape Architecture. 2016;11(1):42–55. doi: 10.1080/18626033.2016.1144673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- William V, Xavier P, Sergio L. Application of a smart city model to a traditional university campus with a big data architecture: A sustainable smart campus. Sustainability. 2019;11:2857. doi: 10.3390/su11102857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winnicka-Jasłowska D. New outlook on higher education facilities. Modifications of assumptions for programming and design of university buildings and campuses under the influence of changing organizational and behavioral needs. ACEE Architecture Civil Engineering Environment. 2012;5(2):31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wünsche K. 1989. Bauhaus: Versuche, das Leben zu ordnen, Wagenbach Verlag, ISBN-13: 9783803151179.

- Żabicki P. 2021. Architektura kampusów, Warszawska Firma Wydawnicza, Warsaw ISBN 978-83-8011-148-6.