Abstract

Arsenic exposure has been reported to alter the gut microbiome in mice. Activity of the gut microbiome derived from fecal microbiota has been found to affect arsenic bioaccessibility in an in vitro gastrointestinal (GI) model. Only a few studies have explored the relation between arsenic exposure and changes in the composition of the gut microbiome and in arsenic bioaccessibility. Here, we used simulated GI model system (GIMS) containing a stomach, small intestine, colon phases and microorganisms obtained from mouse feces (GIMS-F) and cecal contents (GIMS-C) to assess whether exposure to arsenic-contaminated soils affect the gut microbiome and whether composition of the gut microbiome affects arsenic bioaccessibility. Soils contaminated with arsenic did not alter gut microbiome composition in GIMS-F colon phase. In contrast, arsenic exposure resulted in the decline of bacteria in GIMS-C, including members of Clostridiaceae, Rikenellaceae, and Parabacteroides due to greater diversity and variability in microbial sensitivity to arsenic exposure. Arsenic bioaccessibility was greatest in the acidic stomach phase of GIMS (pH 1.5–1.7); except for GIMS-C colon phase exposed to mining-impacted soil in which greater levels of arsenic solubilized likely due to microbiome effects. Physicochemical properties of different test soils likely influenced variability in arsenic bioaccessibility (GIMS-F bioaccessibility range: 8–37%, GIMS-C bioaccessibility range: 2–18%) observed in this study.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) and World Health Organization (WHO) rank inorganic arsenic (As) as the number one priority substance which poses a “significant potential threat to human health” and one of the top ten pollutants, respectively, due to toxicity and exposure potential (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2017; World Health Organization, 2018). Ingestion of food, water, and soil containing inorganic As at hazardous levels can acutely cause diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Chronic oral exposure to As has been linked to colon, kidney, and bladder cancers, cognitive deficits, hyperkeratosis, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (Hughes et al., 2011). Although food and water are more common routes of oral exposure, ingestion of arsenic-contaminated soils occurs in young children who engage in frequent hand-to-mouth activity and pica behavior. Prevalence of hand-to-mouth behavior which is most common in children under 2-years old may account for higher exposure to soil-borne arsenic in this age group (Tulve et al., 2002). Exposure to As has also been shown to perturb gut microbiome composition (Lu et al., 2014a). Recently described associations between interindividual differences in the gut microbiome and variability in metal(loid) bioavailability and bioaccessibility suggest that alteration in the microbiome may affect metal(loid) bioavailability (Lu et al., 2014b; Yin et al., 2017a). Bioavailability is a measure of the percentage of a contaminant present in an ingested material that crosses the gastrointestinal (GI) barrier and is available for systemic distribution and metabolism (Bradham et al., 2018). Bioaccessibility is a surrogate measure for bioavailability that is obtained in in vitro systems and is expressed as the ratio of the amount of contaminant released from the test material by solubilization in an extraction media to the total amount of the contaminant in the test material (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2015a).

In investigations of metal(loid) bioavailability and its mechanisms, a growing number of bioaccessibility studies use multi-compartment systems such as the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem® (SHIME) which contain gut bacteria to recapitulate the human GI tract. SHIME is a chemical and biological simulation of the GI tract and consists of compartments corresponding to the stomach, small intestine, ascending, transverse, and descending colon. All three colon compartments are inoculated with fecal bacteria from human donors; the bacteriological functionality of these microorganisms has been validated for nutrition studies via metabolic byproducts (Van de Wiele et al., 2015). Notably, SHIME contains microorganisms collected from fecal sources to simplify collection and reduce risk to donors and implicitly assumes that the comparison and functionality of the fecal microbiota is comparable to that of the large intestine in vivo (Molly et al., 1994). However, Marteau et al. (2001) and Lkhagva et al. (2021) found that cecal bacteria have greater diversity than fecal bacteria residing along the GI tract and physicochemical properties of feces are different from the large intestine. Because the fecal microbiome does not accurately represent microbiome communities in the gut (Marteau et al., 2001); cecal contents may be a more appropriate source of microorganisms for studies of functionality in the GI tract (Lkhagva et al., 2021).

Earlier studies conducted with SHIME advanced understanding of the microbial and physicochemical properties of the GI system that may influence metal(loid) bioavailability in soils. In SHIME exposed to soil containing As at concentrations ranging from 15 to 3227 mg/kg, As bioaccessibility increased in the presence of the colon microbiome (Yin et al., 2017b). Greater As bioaccessibility has also been observed in the colon phase than in the stomach and intestinal phases (Laird et al., 2007). In contrast to the aforementioned studies, the acidic pH of the stomach environment facilitated greater As dissolution in the low pH stomach phase than in the intestinal and colon phases containing gut bacteria regardless of diet and fed versus fasted state (Yin et al., 2017b; Alava et al., 2015; Sharafi et al., 2019). Taken together, these results highlight the variability in test systems and the role gut microbiota may play in bioaccessibility. Including gut bacteria in bioavailability models may be a valuable approach to identifying factors that affect soil As bioavailability and toxicant-induced alterations in microbiome composition.

In this study, we used a multi-compartment in vitro gastrointestinal model system (GIMS) containing microorganisms from two sources to explore whether the microbiome in the in vitro system affected the bioaccessibility of As in soils, and whether As exposure affected microbiome composition. Here, GIMS contained bacteria from feces (GIMS-F) or cecum contents (GIMS-C) from donor mice. We also explored how microbiome composition and As bioaccessibility differed between GIMS-F versus GIMS-C and how GIMS bioaccessibility compared with a gold standard bioaccessibility assay which has been validated against mice bioavailability data, USEPA SW-846 Method 1340 (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2007). Examining the relationship between soil As exposure and bioaccessibility and microbiome composition will help to elucidate effects of toxic metal(loid) exposure on the absorptive function of the GI tract and bioavailability which may have far-reaching harmful consequences including increased potential for adverse health effects.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Soil processing and characterization

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Standard Reference Material (SRM) 2710a soil is certified for highly elevated As levels (1540 mg/kg) and was purchased from NIST (NIST, Gaithersburg, MD). US Geological Survey (USGS) soil was collected by USGS near an abandoned lead mine in Flat Creek, Montana (USGS, Denver, CO). Sodium arsenate heptahydrate served as a water-soluble positive control (Sigma-Aldrich). Remaining As-contaminated soils were collected from mining and pesticide-impacted sites. Soils were dried at <40 °C and sieved to either <250 μm or <74 μm. Particles <250 μm are most likely to adhere to hands which poses a concern for young children who often engage in hand-to-mouth activity (Xue et al., 2007). Soils were homogenized and riffled, and physicochemical properties were recorded (Table 1). Arsenic soil concentrations were determined using Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis (INAA) in the Department of Nuclear Engineering, North Carolina State University (NCSU, Raleigh, NC; mean As mass detection limit, 0.035 μg).

Table 1.

Test material properties.

| Exposure material in GIMS (F and/or C) | Soil source | Soil properties | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As (mg/kg) | Fe (mg/kg) | Mn (mg/kg) | Al (mg/kg) | Pb (mg/kg) | Zn (mg/kg) | pH | Particle size (micron) | ||

| F | Mining-Impacted | 965 | 97,663 | 1523 | 72,076 | 24 | 461 | 5.7 | <250 |

| F, C | Pesticide-Impacted | 411 | 20,346 | 466 | 12,754 | 1281 | 74 | 5.6 | <250 |

| F, C | NIST 2710 A | 1540 | 38,589 | 1817 | 10,861 | 5582 | 4204 | 4.0 | <74 |

| C | USGS Flat Creek Montana | 748 | 36,054 | 2605 | 4136 | 6745 | 9200 | 5.9 | <250 |

F – GIMS inoculated with fecal material.

C – GIMS inoculated with ceca material.

Unpublished results from EPA/ORD/Bradham laboratory.

2.2. Gastrointestinal microbial system (GIMS)

The GIMS system consisted of four-500 mL jacketed vessels with lids maintained at 37 °C (°C) in a constant temperature bath filled with aluminum beads for heat conduction. Each vessel in the bath was mounted on a magnetic stirrer and the contents of the vessel was continuously agitated by a magnetic stir bar. The entire apparatus was housed in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, MI) containing an atmosphere of 10% hydrogen, 5% carbon dioxide, and 85% nitrogen gases. The four vessels in GIMS represent the stomach, pancreas, small intestine, and colon compartments (Supplementary Fig. 1). The fed stomach solution was adapted from the SHIME methodology (Molly et al., 1994) and comprised of (in grams/liter deionized water): pepsin (2.0), xylan from corn core (1.0), arabinogalactan (1.0), potato starch (4.0), pectin (2.0), glucose (0.4), mucin (4.0), potassium bicarbonate (10.0), yeast extract (3.0), cysteine (0.5), and peptone (1.0) at a pH of 1.5–2.0. Pancreatic fluid was comprised of (in grams/liter deionized water): pancreatin (0.9), bile (6.0), and sodium bicarbonate (12.5). Peristaltic pumps operating at a fixed flow rate of 1.5 mL per minute were used to shuttle fed stomach solution to the small intestine (duration: 18 min) followed by shuttling of pancreatic fluid to the small intestine (duration: 9 min) to achieve a stomach to pancreatic fluid ratio of 2-to-1 or 40.5 mL total (fluid ratio adapted from the SHIME methodology). Fluids were mixed for 2 h before transport, via peristaltic pump, to the colon compartment (duration 13 min or 19.5 mL total) to provide nutrition for colon bacteria (Supplementary Fig. 1). Excess colon fluid (i.e. volumes greater than 300 mL) was removed as needed. Fluid cycling occurred three times per day, seven days per week.

2.3. GIMS bacteria collection and characterization

GIMS were inoculated with 12.5 mL of cecal or fecal material obtained from female mice (Supplementary: GIMS inoculation and verification). Five 1.0 mL replicate colon fluid samples were collected immediately before GIMS inoculation, 2 h after GIMS inoculation, and every seven days for 28 days prior to and after weekly As exposure (Fig. 1). Upon collection, all microbe samples were centrifuged at 4500×g for 10 min. The supernate was discarded, and pelleted material was stored at −80 °C until it was processed for 16 S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing (16 S rRNA). DNA was isolated from fecal pellets and fluid/soil exposure mix using a PowerSoil® DNA isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, California) according to manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was amplified using universal primers (515 and 806) to target the V4 regions of 16 S rRNA. Individual samples were barcoded, pooled to construct the sequencing library, and sequenced on an Illumina Miseq (Illumina, California) to generate pair-ended 250 × 250 reads. Raw mate-paired fastq files were quality-filtered and data were analyzed using Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME). UCLUST were used to get the observed operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with a 97% sequence similarity threshold. Taxonomy was assigned at six different levels: phylum, class, order, family, genus and species.

Fig. 1.

Experiment Setup.

2.4. In vitro bioaccessibility (IVBA) SW-846, method 1340 data

Total As bioaccessibility data for NIST 2710 A standard reference material obtained with IVBA SW-846, Method 1340 were compared with total As bioaccessibility data obtained with the GIMS system. This approach allowed evaluation of GIMS results in terms of results from a “gold standard” bioaccessibility assay that has undergone extensive inter- and intra-laboratory testing. Estimates of total As bioaccessibility data obtained with IVBA SW-846, Method 1340 have been strongly correlated with estimates of soil As bioavailability obtained with the mouse assay (United States Environmental Protection Agency and Innovation, 2017; United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2015b). In addition, Method 1340 data are publicly available (United States Environmental Protection Agency and Innovation, 2017) and data were previously acquired by USEPA in accordance with standard operating procedures for IVBA SW-846, Method 1340 (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2017a).

2.5. GIMS bioaccessibility assay

In GIMS inoculated with fecal bacteria (GIMS-F), 12 mL aliquots of fluid from each GIMS-F compartment were exposed to As-contaminated test materials (NIST 2710a, pesticide-impacted, mining-impacted soils, or sodium arsenate heptahydrate (positive control)) to form a reaction mixture with a final As concentration of 50 ppm. Due to a shortage of mining-impacted test material, this test material was omitted from the protocol at week 3 in GIMS-F study and replaced with USGS test material in GIMS-C study. In GIMS inoculated with cecal bacteria (GIMS-C), every seven days post-inoculation, 12 mL aliquots of stomach, small intestine, or colon fluid was exposed to As-contaminated test materials (NIST 2710 A, sodium arsenate heptahydrate (positive control), USGS, and pesticide-impacted soils) to form a 50 ppm As mixture. Reaction mixtures were prepared on day 7, 14, 21, and 28 after initial inoculation (Fig. 1). All final As concentrations of 50 ppm were based on the As mass in the dried soil samples. In studies 1 and 2, a no-exposure (negative) control was included.

Reaction mixtures containing fluid from the stomach and small intestine compartments were incubated for 2 h; and reaction mixtures containing fluid from the colon phase were incubated for 20 h at 37 °C with constant shaking within a large AtmosBag glove bag (Sigma, Milwaukee, WI) filled with 99.92% compressed nitrogen gas to maintain anaerobic conditions. After exposure, 5–1 mL replicate aliquots from each exposure condition were collected and centrifuged at 5000 rcf for 10 min to separate supernate (soluble As) and pellet (insoluble As). Supernates and pellets were stored at −80 °C until submitted for determination of As by INAA. Arsenic bioaccessibility in each phase was calculated from INAA values using the following equation:

| (1) |

Total arsenic bioaccessibility in GIMS was the sum of percent bioaccessibility in stomach, small intestine, and colon phases.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was used to determine beta diversity which reflects microbial diversity between samples via comparison of gut microbiome community profiles between the control and As-exposed groups. Rarefaction curves were used to characterize alpha diversity which reflects taxa richness and relative abundance between groups (weighted UniFrac). In GIMS-F study, t-tests and one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s pairwise comparison test (Stata version 16.0 software, College Station, TX) were used to determine significant differences between mean percentage As IVBA by week and GI phase, respectively, after exposure to each test material. Data were normally distributed and met assumptions for t-tests and ANOVA. T-tests were performed to determine significant differences in total As bioaccessibility between GIMS at weeks 3 and 4 and USEPA-validated Method 1340 after exposure to NIST 2710a soil. Method 1340 and GIMS week 3 data had equal variance; method 1340 and GIMS week 4 data had unequal variance. T-tests for data with or without unequal variance were performed when appropriate. A p-value <0.05 indicated significant differences between groups.

In GIMS-C study, arsenate and NIST exposure data were normally distributed and met assumptions for t-tests and ANOVA. Pesticide-impacted and USGS data were not normally distributed before and after data transformations and non-parametric statistical tests were conducted for these data. T-tests and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s pairwise comparison tests were performed to assess significant differences between mean % As IVBA by week and GI phase, respectively, after exposure to each test material. For non-parametric data, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were performed to determine differences between weeks 3 and 4 mean percent IVBA for each GI phase. To identify differences between mean percent As IVBA across GI phases after exposure to each test matrix 3 and 4 weeks after GIMS inoculation, Kruskal Wallis tests were performed. T-tests were performed to identify differences in total As bioaccessibility between GIMS at weeks 3 and 4 and EPA-validated Method 1340 after exposure to NIST 2710a soil. A p-value <0.05 indicated significant difference.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. GIMS bacterial community stabilizes by weeks 3–4

Alpha diversity reflects species richness within samples as represented in the rarefaction curves. Beta diversity reflects the microbial diversity between samples as represented in the PCoA analysis. PCoA analysis showed segregation between microbial diversity of the original inoculum and all other arsenic-exposed and non-exposed groups in GIMS-F (Fig. 2c) and GIMS-C post-inoculation (Fig. 2f). After GIMS inoculation, bacteria abundance fluctuated along all timepoints prior to day 21 in GIMS-F and GIMS-C (Supplementary Tables 2-3). Disappearance of members from the families Erysipelotrichaceae and Clostridiaceae, relative to the inoculum, were observed in both GIMS-F and GIMS-C (Supplementary Tables 3-4). Relative to the inoculum, disappearance of members from the families Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococceae, and Rikenellaceae as well as genera Akkermansia, Dehalobacterium, and Parabacteroides were unique to GIMS-F. Extinction of selected microbes was likely due to failure of microbes to thrive in culture conditions (Almeida et al., 2019; Ormerod et al., 2016). Environmental pressures such as microbial competition for nutrients and space, absence of required nutrients, and antimicrobial properties of certain bacteria (e.g. members of the Bacillaceae family) within the colon phase may contribute to the loss of diversity (Justice et al., 2017).

Fig. 2. Alpha and Beta diversity at weeks 3–4 in GIMS-F (A–C) and GIMS-C (D–F).

A.) Alpha diversity (observed OTU) rarefaction curve at week 3 B) Alpha diversity at week 4 C) PCoA based on weighted UniFrac distances of no exposure (inoculum: blue, 2 h post-inoculation: red, week 1: yellow, week 2: gray, week 3: black, week 4: magenta) and arsenic-exposed groups (week 1: green, week 2: pink, week 3: teal, week 4: purple). Weeks 2–4 no exposure groups are circled in black. Weeks 2–4 arsenic-exposed groups are circled in red. D.) Alpha diversity rarefaction curve at week 3. E.) Alpha diversity at week 4 F) PCoA based on weighted UniFrac distances of no exposure (inoculum: blue, 2 h post-inoculation: red, week 1: green, week 2: pink, week 3: beige, week 4: purple) and arsenic-exposed groups (week 2: gray, week 3: black, week 4: magenta). Week 1 arsenic-exposed groups are circled in green. A cluster of week 2 arsenic-exposed, no exposure, and 2 h post-inoculation groups are circled in red. A cluster of weeks 3–4 no exposure and arsenic-exposed groups are circled in black.

From days 21–28 (or weeks 3–4), bacteria count increased in GIMS-F (i.e. total number of anaerobes and lactose-fermenting bacilli) and GIMS-C (i.e. total anaerobes, Lactobacilli, anaerobic gram-negative rods, lactose-fermenting bacilli, and non-fermenting bacilli) (Supplementary Tables 2-6). These determinative microbiology findings aligned with the 16 S rRNA gene sequencing data (Supplementary Tables 5-6). Notably at weeks 3–4, greater microbial diversity was sustained in GIMS-C than in GIMS-F. Segregation of GIMS-F week 1 and 2 clusters from weeks 3–4 with 83.3%, 10.16%, and 4.55% variation explained by PC1-PC3, respectively, indicated changes in microbial diversity occurred for 2 weeks with microbial community stabilization reached by week 3 (Fig. 2c). Due to system stabilization at week 3, weeks 3–4 were the focus of microbiome and bioaccessibility analyses. In the GIMS system, selective pressures associated with microbial extinction likely played a role in the progression from an unsteady state, characterized by temporal variability in bacteria community structure up to week 3, to a steady state at week 3 at which time temporal variability was no longer observed. This stabilization period is similar to SHIME in which system stability is typically attained by week 3 based on production of specific metabolic byproducts (Van de Wiele et al., 2015; Molly et al., 1994).

According to GIMS-F 16 S rRNA results, Bacteroidetes (62.1%) and Firmicutes (27.1%) comprised the bulk of bacteria in the colon compartment followed by Proteobacteria (10.6%) based on average taxa percentage across no exposure treatments for weeks 3 through 4 (Table 2, Supplementary Tables 5-6). In contrast to microbiome composition in GIMS-F, Verrucomicrobia (37.8%), Proteobacteria (29.8%), and Bacteroidetes (22.6%) made up 90% of the bacteria in the GIMS-C colon phase based on the average taxa percentage for the no exposure control at weeks 3–4. Firmicutes accounted for 9.4% of the bacteria in the GIMS-C colon phase. These results contrast with other mammalian studies in which Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes comprise the bulk of the bacteria in the colon (combined range = 76–94%); Verrucomicrobia and Proteobacteria (combined range = 0.18–21%) make up the smallest percentage of bacteria in the colon (Lu et al., 2014a; Donaldson et al., 2016; Arumugam et al., 2011).

Table 2.

Fold change in abundance and taxa assignments of gut bacteria in GIMS-F colon fluid exposed to arsenic compared to no exposure control at week 3 and 4.

| Bacteria | Week 3 | Week 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test Material | Test Material | |||||||

| Arsenate | Pesticide-Impacted | USGS | NIST 2710 A | Arsenate | Pesticide-Impacted | USGS | NIST 2710 A | |

| Akkermansia | 1.20 | 1.16 | 1.27 | 1.32 | 1.13 | 1.14 | 1.37 | 1.42 |

| Bacteroides | 1.25 | 1.65 | 1.01 | 1.12 | −1.02 | 1.40 | −1.04 | −1.07 |

| Bilophila | −1.74 | −1.68 | −1.90 | −1.97 | −1.33 | −1.44 | −1.75 | −2.57 |

| Clostridiaceae g.__ | −3.10 | −4.23 | −4.45 | −4.03 | 1.34 | −1.14 | −1.30 | −1.40 |

| Clostridiaceae g. other | X | X | X | X | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Clostridium | 3.15 | 2.09 | 2.94 | 9.90 | 1.30 | −1.60 | −1.72 | −1.14 |

| Enterobacteriaceae g.__ | 1.00 | −1.28 | 1.13 | −1.03 | 1.00 | −1.23 | −1.10 | −1.10 |

| Enterococcus | 1.03 | −2.33 | −1.46 | −1.46 | 1.17 | −2.00 | −1.71 | −1.71 |

| Lachnospiraceae g.__ | 1.15 | −1.28 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.03 | −1.56 | −1.12 | −1.47 |

| Lactobacillales f.__ g.__ | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.60 | X | X | X |

| Parabacteroides | X | 4.33 | −3.75 | X | X | 6.20 | 1.00 | X |

| Peptostreptococcaceae g.__ | −1.09 | −1.17 | 1.14 | 1.54 | 1.25 | −1.22 | −1.08 | −1.04 |

| Proteus | −26.67 | −16.00 | −2.29 | −40.00 | −1.46 | −1.79 | −2.00 | −2.39 |

| Rikenellaceae g.__ | X | −3.70 | X | X | X | −4.40 | X | X |

| Sutterella | −1.29 | −1.15 | −1.83 | −2.54 | 1.41 | 1.19 | −0.19 | −1.87 |

“ND” is microbe not detected in no exposure and arsenic-exposed groups. “X” is microbe became extinct in arsenic-treated group.

3.2. Arsenic exposure disturbs GIMS-C microbiome

Upon exposure to As at week 3, GIMS-F control had greater alpha diversity than As-exposed groups (Fig. 2a). This divergence in control and As-treated groups narrowed at week 4 with the exception of mining-impacted soil (Fig. 2b). Alpha diversity in mining-impacted soil was greater than all other groups at week 4 likely due to the presence of two soil bacteria genera (Verrucomicrobia DA101 and Solibacterales (f) Candidatus (g)). The beta diversity in GIMS-F As-exposed colon phases remained similar to that of the no exposure group (Fig. 2c). More specifically, there were less than 2-fold change in genera across all treatments, except for NIST 2710 A treated group at week 4 in which a 4-fold change in Oscillospira spp. was observed. Week 1 no-exposure control data are unavailable. This data suggests As exposure had no impact on the GIMS-F microbiome.

In GIMS-C, alpha diversity or microbial richness was comparable across all groups. In PCoA plots, segregation of no exposure groups from As-exposed groups with 60% variation explained by PC1, 19% variation explained by PC2, and 8% explained by PC3 suggests As exposure disrupts the microbial community composition regardless of bacteria age (2 weeks vs 3 weeks vs 4 weeks) in the GIMS-C colon phase (Fig. 2f). Upon closer inspection of the 16 S rRNA data, exposure to As in all contaminated soils resulted in the disappearance of two or more bacteria genera. More specifically, three bacteria genera (Parabacteroides, Rikenellaceae g.__, and Clostridiaceae g. other) disappeared in the colon phase at week 3 upon exposure to arsenate for 20 h (Table 3). Bilophila and Sutterella declined with the greatest drop observed in Proteus abundance (27 -fold) relative to the no exposure control. In addition to Lactobacillales f.__ g.__, the same three bacteria genera also disappeared in the colon phase at week 4 (Table 3). Unlike the no exposure group at week 3, 4-week-old GIMS no exposure colon phase contained Lactobacilles f.__ g.__. This data suggests some bacteria families may require more time to become established in an in vitro GI system. If sufficient time is not allowed for select taxa to reach the threshold of detection in control samples, then adverse effects on the microbial community and potential effects on health may be missed. For example, members of the order Lactobacillales are responsible for producing bacteriocins, hydrolyzing bile salts, reducing serum cholesterol levels, and limiting protease activity (Wiedemann et al., 2006; Klaenhammer, 1993; Lye et al., 2010). In the absence of Lactobacillales, elevated protease activity may be a precursor to GI diseases (Edgington-Mitchell, 2016).

Table 3.

Fold change in abundance and taxa assignments of gut bacteria in GIMS-C colon fluid exposed to arsenic relative to no exposure control at week 3 and 4.

| Bacteria | Week 3 | Week 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test Material | Test Material | |||||||

| Arsenate | Pesticide-Impacted | USGS | NIST 2710 A | Arsenate | Pesticide-Impacted | USGS | NIST 2710 A | |

| Akkermansia | 1.20 | 1.16 | 1.27 | 1.32 | 1.13 | 1.14 | 1.37 | 1.42 |

| Bacteroides | 1.25 | 1.65 | 1.01 | 1.12 | −1.02 | 1.40 | −1.04 | −1.07 |

| Bilophila | −1.74 | −1.68 | −1.90 | −1.97 | −1.33 | −1.44 | −1.75 | −2.57 |

| Clostridiaceae g.__ | −3.10 | −4.23 | −4.45 | −4.03 | 1.34 | −1.14 | −1.30 | −1.40 |

| Clostridiaceae g. other | X | X | X | X | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Clostridium | 3.15 | 2.09 | 2.94 | 9.90 | 1.30 | −1.60 | −1.72 | −1.14 |

| Enterobacteriaceae g.__ | 1.00 | −1.28 | 1.13 | −1.03 | 1.00 | −1.23 | −1.10 | −1.10 |

| Enterococcus | 1.03 | −2.33 | −1.46 | −1.46 | 1.17 | −2.00 | −1.71 | −1.71 |

| Lachnospiraceae g.__ | 1.15 | −1.28 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.03 | −1.56 | −1.12 | −1.47 |

| Lactobacillales f.__ g.__ | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.60 | X | X | X |

| Parabacteroides | X | 4.33 | −3.75 | X | X | 6.20 | 1.00 | X |

| Peptostreptococcaceae g.__ | −1.09 | −1.17 | 1.14 | 1.54 | 1.25 | −1.22 | −1.08 | −1.04 |

| Proteus | −26.67 | −16.00 | −2.29 | −40.00 | −1.46 | −1.79 | −2.00 | −2.39 |

| Rikenellaceae g.__ | X | −3.70 | X | X | X | −4.40 | X | X |

| Sutterella | −1.29 | −1.15 | −1.83 | −2.54 | 1.41 | 1.19 | −0.19 | −1.87 |

“ND” is microbe was not detected in no exposure and arsenic-exposed groups. “X” is microbe became extinct in arsenic-treated group.

Three bacteria genera disappeared in the 3-week-old colon phase after exposure to NIST 2710 A (Parabacteroides, Rikenellaceae g.__, and Clostridiaceae g. other); two genera disappeared after exposure to USGS (Rikenellaceae g.__, and Clostridiaceae g.) soils; and six genera in each treatment group declined in abundance (Table 3). The same bacteria, which were undetected at week 3 upon exposure to NIST 2710 A and USGS soils, were also undetected at week 4 (Table 3). Ten out of 11 genera declined upon exposure to NIST 2710 A and 11 out of 12 genera declined upon exposure to USGS. Lactobacilles f.__ g.__ was absent in 4-week-old colon phases exposed to NIST 2710 A and USGS. Only 1 bacteria genus (Clostridiaceae g. other) was absent after the 3-week-old GIMS colon phase was exposed to pesticide-impacted soil. Clostridiaceae g. other as well as Lactobacilles f.__ g.__ were absent in 4-week-old GIMS colon phase exposed to pesticide-impacted soil.

This study, in which members of Class Clostridia (orders Lachnospiraceae and Clostridiales) displayed sensitivity to As exposure, aligned with recent findings that As-contaminated drinking water (10 ppm) disturbed the gut microbiome composition of mice when consumed over the course of 4 weeks (Lu et al., 2014a). Clostridia are involved in the production of short chain fatty acids, regulation of immune response, and upregulation of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine all of which regulate cognition, learning, and mood (Skillings, 2016; Lopetuso et al., 2013; Morrison and Preston, 2016). Disappearance and decline of Clostridia may have far-reaching effects on host physiology and function. In contrast to effects of all test soils, GIMS-C fluids treated with arsenate at weeks 3 and/or 4 did not present a decline in Enterococcus and family Lachnospiraceae. These differences between arsenate and other As-treated groups, despite normalization of As concentrations to 50 ppm, could be attributed to variability in soil properties not related to As content. Other soil-bound contaminants, such as lead (Pb) and manganese (Mn), have been associated with decreases in Enterococcus and Lachnospiraceae (Lopetuso et al., 2013).

When compared to USGS and NIST 2710a, GIMS-C colon fluid treated with pesticide-impacted soils were found to have a greater number of surviving taxa. More specifically, Rikenellaceae survived, and Parabacteroides survived and increased in abundance relative to the no exposure control in GIMS-C at week 4. Properties of the pesticide-impacted soil may have provided an environment amenable to microbial survival. Pesticide-impacted soils contained the lowest concentrations of zinc (Zn), Pb, Mn, and iron (Fe) among all soils. Rikenellaceae and Parabacteroides may have been sensitive to one or more metal constituents in the other test matrices. For example, La Carpia et al. (La Carpia et al., 2019) found a negative correlation between increasing Fe concentrations and Parabacteroides abundance in mice exposed to Fe via diet. Further study is needed to assess how co-occurrence of soil contaminants alter the microbiome.

There are differences between GIMS-C and GIMS-F in the changes in microbial diversity and abundance. In broad terms, larger declines in diversity and abundance were found in GIMS-F than in GIMS-C prior to arsenic exposure. The greater loss of diversity and abundance in GIMS-F results in fewer surviving bacteria with the potential to reflect the negative impacts of As exposure on the microbiome. This may limit the utility of this system to detect arsenic-mediated effects in surviving bacteria. This limitation highlights the need to select a source for inoculum in which microbial diversity is preserved under physiological conditions. Identifying the factors which determine the suitability of various inoculum sources will require deeper understanding of the selective pressures that shape and maintain the gut microbiome.

3.3. Arsenic bioaccessibility is greatest in stomach phase of GIMS-F and GIMS-C exposed to NIST 2710a soil and in colon phase of GIMS-C exposed to USGS soil

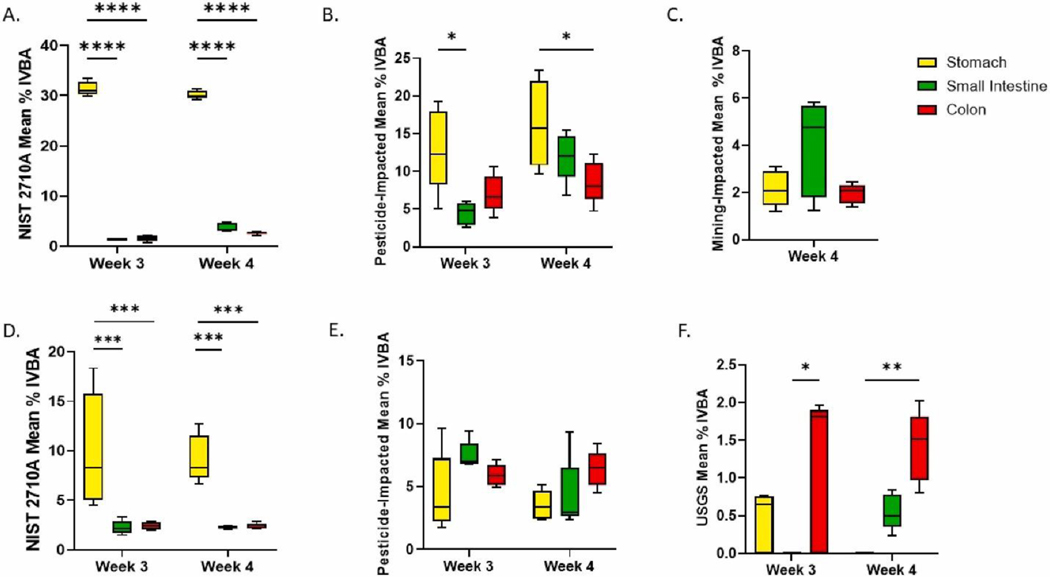

In NIST 2710a-exposed groups, the stomach phase solubilized significantly greater levels of As at weeks 3 and 4, respectively, (GIMS-F: 31 ± 1% and 30.1 ± 0.8%, GIMS-C:10 ± 6% and 9 ± 2%), than did small intestine (GIMS-F: 1.4 ± 0.1% and 3.7 ± 0.8%, GIMS-C: 2.3 ± 0.7% and 2.3 ± 0.2%) and colon phases (GIMS-F: 1.6 ± 0.6% and 2.6 ± 0.2%, GIMS-C: 2.4 ± 0.4% and 2.4 ± 0.3%) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 7). Notably, the chemical constituents of the GIMS-C and GIM-F GI phases are the same, yet stark differences in As bioaccessibility were observed. These differences may be due to high variability within and between performance of test procedures at each GI phase as well as variability in analytical analyses and is partially reflected in the broad standard deviations seen in GIMS-C At weeks 3–4 in phases exposed to pesticide-impacted soil, a similar trend was observed for pesticide-impacted soils in GIMS-F and not GIMS-C. GIMS-F stomach fluid exposed to pesticide-impacted soils solubilized significantly greater amounts of As (Week 3 mean: 13 ± 5%, Week 4 mean: 16 ± 5%) than the small intestine (4 ± 3%, p < 0.05) at week 3 and colon (8 ± 2%, p < 0.05) phases at week 4 (Fig. 3). Similar to NIST 2710a in this study, greater As bioaccessibility has been reported in the acidic stomach environment (pH 1.5) than in intestinal environments (pH 6.0) (Pelfrêne and Douay, 2018; Turner and Ip, 2007; Li et al., 2018). The acidic stomach pH appears to have a stronger role than the colon microbiome in As dissolution when exposed to NIST 2710a and pesticide-impacted soils.

Fig. 3. Mean Percent IVBA for weeks 3–4 in each GI phase of GIMS-F and GIMS-C.

A.) NIST 2710 A GIMS-F B) Pesticide-impacted soil GIMS-F C.) Mining-impacted soil GIMS-F D.) NIST 2710 A GIMS-C E.) Pesticide-impacted soil GIMS-C F.) USGS soil GIMS-C. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0001).

Lower than expected amounts of As dissolved in the stomach phase upon exposure to pesticide-impacted, mining-impacted, and USGS soils. Soil properties affecting As-soil binding affinity or metal interactions in soil leading to As sequestration may have hindered bioaccessibility in the stomach phase. One study identified various soil properties (e.g. co-occurrence of As, Fe, phosphorus, and Zn), which are also believed to be at work in this study, that work in concert to influence As bioaccessibility (Nelson et al., 2018). Differences in the physicochemical properties of each test soil likely led to variability in As IVBA between soils. Soils high in trivalent iron hydroxides have a strong binding affinity for arsenate and arsenite; sequestration by iron hydroxide could reduce As (He and Hering, 2009; Bradham et al., 2011). In this study, total Fe concentrations in the test soils ranged from 20,000–98,000 ppm (Table 1); and As bioaccessibility decreased as the ratio of total As to iron decreased. A limitation of this study is that bioaccessibility of other soil-bound metals and speciation of all metals were not characterized. Although Fe bioaccessibility and speciation were not performed, the potential role of soil iron hydroxide to hinder As bioaccessibility cannot be discounted.

There were no significant differences in As bioaccessibility between GI phases after exposure to pesticide-impacted soil in GIMS-C and mining-impacted soil in GIMS-F. Arsenic was not bioaccessible in GIMS-C stomach fluid exposed to USGS soil at week 4 and in the small intestine fluid at week 3 (Fig. 3f). GIMS-F and GIMS-C percent bioaccessibility in each phase did not differ from week 3 to week 4, except for small intestine fluids exposed to pesticide-impacted and USGS soils in GIMS-F and GIMS-C, respectively. In these cases, As bioaccessibilities were greater at week 4 than week 3 (P = 0.001, Supplementary Table 7). These data suggest any changes observed in the microbiome composition from week 3 to week 4 after exposure to NIST 2710a and pesticide-impacted soils, did not enhance bioaccessibility as reported in other studies (Yin et al., 2017b; Laird et al., 2007). Arsenic uptake by the microbiota of the colon phase could affect the distribution of As between the soluble and insoluble fractions (Chi et al., 2019) and the level of free As available for dissolution. It remains unknown which bacteria families are involved in As removal and As bioaccessibility in the GI tract and whether these populations are present and abundant in GIMS. Although colon microbes may be involved in reducing exposure to As, colon bacteria can also contribute to As toxicity by enzymatically catalyzed conversion of pentavalent As to methylated species that contain trivalent As (Van de Wiele et al., 2010).

Upon exposure to USGS soil, the colon phase solubilized greater amounts of As than stomach and small intestine phases at week 4 and 3, respectively (Fig. 3f). USGS had quantitatively higher levels of Mn, Pb, and Zn, than NIST 2710a and pesticide-impacted soils after normalization to 50 ppm As. Microorganisms’ effects on bioaccessibility and bioavailability are likely dependent on physicochemical properties of the As-containing soils and microbiome composition. For example, while we did not explore whether Mn, Pb, and Zn were associated with As-bearing minerals in the test soils, oxidative dissolution of these minerals by microbes may have led to increased release and dissolution of As (Drewniak and Sklodowska, 2013). Also, Gammaproteobacteria, which had greater abundance in USGS than in NIST 2710a and pesticide-impacted soils, are associated with interconversion of As species via microbial transformation which may have altered As kinetics and facilitated As dissolution (Chaturvedi and Pandey, 2014). Other microbe-associated variables may have altered As bioaccessibility and bioavailability (Drewniak and Sklodowska, 2013; Laird et al., 2013; Laird et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2012). Further investigation of As geochemistry, microbial removal and transformation of As, including determination of the oxidation state of As present in metabolites in the colon fluid, will provide a complete characterization of As exposure and bioaccessibility. Sodium arsenate IVBA in GIMS-F and GIMS-C ranged from 95 to 98% and 65–100%, respectively, across all simulated fluid incubations and timepoints. Arsenic concentration in GIMS-F no exposure groups across all timepoints ranged from below the limit of detection (ND) to 0.13 ppm in the stomach, ND to 0.22 ppm in the small intestine, and ND to 0.21 ppm in the colon phases. Arsenic concentration in the GIMS-F no exposure groups ranged from ND to 0.04 ppm in the stomach and ND in small intestine and colon phases.

Among all soils tested, arsenic bioaccessibility was greatest in NIST2710a. One marked difference between NIST 2710 A and the other test soils is that NIST 2710 A soil had been sieved to a smaller size fraction (<74 μm) than USGS and pesticide-impacted soils (<250 μm). One study found an inverse relationship between soil particle size (decrease from <250 to <2.5 μm) and percent As bioaccessibility (Smith et al., 2009). It is plausible that As bioaccessibility increased when a smaller particle size was used. Particle size analysis was not conducted in this study, thus the particle size distribution in all soil samples remains unknown.

3.4. As bioaccessibility in GIMS-F only aligns with EPA method 1340 IVBA for NIST 2710 A soil

In GIMS-F, there were no significant differences in NIST 2710 A total As bioaccessibility (or sum of bioaccessibility across GI phases) at weeks 3 (34.4 ± 0.7%, p = 0.241) and 4 (36.4 ± 0.4%, p = 0.596) when compared to Method 1340 (38 ± 5%). Conversely, total As bioaccessibility in GIMS-C exposed to NIST 2710a was significantly less than that of Method 1340 at week 3 (14.7 ± 2.0%, p < 0.0001) and 4 (13.7 ± 0.7%, p < 0.0001). Variability within and between performance of test procedures at each GI phase as well as variability in analytical analyses may have contributed to differences in estimates of As bioaccessibility in GIMS-C compared to validated Method 1340. Constituents in the nutrient feed (cysteine and pectin) have also been shown to have a high binding affinity for As (Bhattacharjee and Rosen, 1996; Eliaz et al., 2006) which may also hinder As dissolution in the GIMS. Bile salts which are used in GIMS have been reported to bolster the interaction between Fe and As, resulting in precipitation of the complex and declines in bioaccessibility (Alava et al., 2013). In contrast, Method 1340 medium does not contain bile salts. Notably, GIMS media does not contain unconjugated bile acids which are present in mice GI tract and may affect As dissolution. Use of unconjugated bile acids, such as chenodeoxycholic acid and cholic acid, in addition to bile salts may increase GIMS As bioaccessibility to levels similar to Method 1340.

A criterion for validation of a test method includes repeated testing and refinement of the procedure across a variety of test soils to reduce within- and between-laboratory variability (Griggs et al., 2021). This exercise provides a way to assess the accuracy and reproducibility of the assay and to increase confidence in its predictive value (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2017b). Although Method 1340 has been validated for assessing the oral bioaccessibility of As, GIMS has not undergone the levels of testing required for validation. This research highlights the need to optimize in vitro test conditions and procedures, rigorously test the accuracy and precision of this assay that will support assay validation efforts and generate results that are the best approximation to bioavailability results across a range of test materials which may then be used to inform risk management decisions. Despite this limitation, GIMS inoculated with cecal bacteria provided valuable insight into how As restructures bacteria communities over time in the gut. Using cecal bacteria as an alternative to fecal bacteria may allow researchers to achieve greater ability to characterize the relationship between As exposure and the gut microbiome using an in vitro GI model.

4. Conclusions

GIMS was used to characterize the relationship between soil As exposure, microbiome composition and As bioaccessibility. The current study provided data to compare effects using feces or cecal contents as the inoculum. This study identified major differences (i.e., greater diversity and lower levels of total anaerobes in cecal bacteria) in microbial community structure between fecal and cecal sources which contributed to differential microbial response to soil As exposure. Microbes were not found to play a role in As bioaccessibility regardless of microbe source in nearly all test soils, except USGS in which microbes likely enhanced As bioaccessibility. Unlike other test soils, GIMS-F As bioaccessibility in NIST 2710 soil aligned with IVBA data from validated method 1340. This study highlights the importance of inoculum source, physiochemical and geochemical properties of soils and assay conditions on the relationship between microbiome and metal(loid) bioaccessibility.

Supplementary Material

Disclaimer

This publication was made possible by an NIEHS-funded pre-doctoral fellowship to Jennifer L Griggs (T32 ES007018) and the UNC Superfund Research Program (P42ES005948). This work has been subjected to EPA administrative review by ORD’s Center for Environmental Measurement and Modeling and approved for publication. Although the author is an FDA/CTP employee, this work was not done as part of her official duties. This publication reflects the views of the author and should not be construed to reflect the FDA/CTP’s, NIEHS, NIH, or EPA views or policies.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2017. ATSDR’s Substance Priority List, 2018 12/04/2018]; Available from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/spl/#2017spl.

- Alava P, et al. , 2013. Arsenic bioaccessibility upon gastrointestinal digestion is highly determined by its speciation and lipid-bile salt interactions. J. Environ. Sci. Health - Part A Toxic/Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng 48 (6), 656–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alava P, et al. , 2015. Westernized diets lower arsenic gastrointestinal bioaccessibility but increase microbial arsenic speciation changes in the colon. Chemosphere 119, 757–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida A, et al. , 2019. A new genomic blueprint of the human gut microbiota. Nature 568 (7753), 499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam M, et al. , 2011. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 473 (7346), 174–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee H, Rosen BP, 1996. Spatial proximity of Cys113, Cys172, and Cys422 in the metalloactivation domain of the ArsA ATPase. J. Biol. Chem 271 (40), 24465–24470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradham KD, et al. , 2011. Relative bioavailability and bioaccessibility and speciation of arsenic in contaminated soils. Environ. Health Perspect 119 (11), 1629–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradham KD, et al. , 2018. In vivo and in vitro methods for evaluating soil arsenic bioavailability: relevant to human health risk assessment. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part A B 21 (2), 83–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi N, Pandey PN, 2014. Phylogenetic analysis of gammaproteobacterial arsenate reductase proteins specific to enterobacteriaceae family, signifying arsenic toxicity. Interdiscipl. Sci. Comput. Life Sci 6 (1), 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi L, et al. , 2019. Gut microbiome disruption altered the biotransformation and liver toxicity of arsenic in mice. Arch. Toxicol 93 (1), 25–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson GP, Lee SM, Mazmanian SK, 2016. Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nat Rev Micro 14 (1), 20–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewniak L, Sklodowska A, 2013. Arsenic-transforming microbes and their role in biomining processes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser 20 (11), 7728–7739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgington-Mitchell LE, 2016. Pathophysiological roles of proteases in gastrointestinal disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 310 (4), G234–G239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliaz I, et al. , 2006. The effect of modified citrus pectin on urinary excretion of toxic elements. Phytother Res. 20 (10), 859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griggs JL, et al. , 2021. Improving the predictive value of bioaccessibility assays and their use to provide mechanistic insights into bioavailability for toxic metals/metalloids – a research prospectus. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part A B 24 (7), 307–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YT, Hering JG, 2009. Enhancement of arsenic(III) sequestration by manganese oxides in the presence of iron(II). Water Air Soil Pollut. 203 (1), 359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes MF, et al. , 2011. Arsenic exposure and toxicology: a historical perspective. Toxicol. Sci. : off. j. Soc. Toxicol 123 (2), 305–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice NB, et al. , 2017. Environmental selection, dispersal, and organism interactions shape community assembly in high-throughput enrichment culturing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 83 (20) e01253–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaenhammer TR, 1993. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS (Fed. Eur. Microbiol. Soc.) Microbiol. Rev 12 (1–3), 39–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Carpia F, et al. , 2019. Transfusional iron overload and intravenous iron infusions modify the mouse gut microbiota similarly to dietary iron. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 5 (1), 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird BD, et al. , 2007. Gastrointestinal microbes increase arsenic bioaccessibility of ingested mine tailings using the simulator of the human intestinal microbial Ecosystem. Environ. Sci. Technol 41 (15), 5542–5547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird BD, et al. , 2009. Nutritional status and gastrointestinal microbes affect arsenic bioaccessibility from soils and mine tailings in the simulator of the human intestinal microbial Ecosystem. Environ. Sci. Technol 43 (22), 8652–8657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird BD, et al. , 2013. An investigation of the effect of gastrointestinal microbial activity on oral arsenic bioavailability. J. Environ. Sci. Health, Part A 48 (6), 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H-B, et al. , 2018. Food influence on lead relative bioavailability in contaminated soils: mechanisms and health implications. J. Hazard Mater 358, 427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lkhagva E, et al. , 2021. The regional diversity of gut microbiome along the GI tract of male C57BL/6 mice. BMC Microbiol. 21 (1), 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopetuso LR, et al. , 2013. Commensal Clostridia: leading players in the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Gut Pathog. 5 (1), 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, et al. , 2014a. Arsenic exposure perturbs the gut microbiome and its metabolic profile in mice: an integrated metagenomics and metabolomics analysis. Environ. Health Perspect 122 (3), 284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, et al. , 2014b. Gut microbiome phenotypes driven by host genetics affect arsenic metabolism. Chem. Res. Toxicol 27 (2), 172–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lye H-S, Rahmat-Ali GR, Liong M-T, 2010. Mechanisms of cholesterol removal by lactobacilli under conditions that mimic the human gastrointestinal tract. Int. Dairy J 20 (3), 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Marteau P, et al. , 2001. Comparative study of bacterial groups within the human cecal and fecal microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 67 (10), 4939–4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molly K, et al. , 1994. Validation of the simulator of the human intestinal microbial Ecosystem (SHIME) reactor using microorganism-associated activities. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis 7 (4), 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DJ, Preston T, 2016. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microb. 7 (3), 189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CM, et al. , 2018. Relating soil geochemical properties to arsenic bioaccessibility through hierarchical modeling. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part A 81 (6), 160–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormerod KL, et al. , 2016. Genomic characterization of the uncultured Bacteroidales family S24–7 inhabiting the guts of homeothermic animals. Microbiome 4 (1), 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelfrene A, Douay F, 2018. Assessment of oral and lung bioaccessibility of Cd and Pb from smelter-impacted dust. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser 25 (4), 3718–3730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharafi K, et al. , 2019. Bioaccessibility analysis of toxic metals in consumed rice through an in vitro human digestion model – comparison of calculated human health risk from raw, cooked and digested rice. Food Chem. 299, 125126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skillings D, 2016. Holobionts and the ecology of organisms: multi-species communities or integrated individuals? Biol. Philos 31 (6), 875–892. [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Weber J, Juhasz AL, 2009. Arsenic distribution and bioaccessibility across particle fractions in historically contaminated soils. Environ. Geochem. Health 31 (1), 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G-X, et al. , 2012. Arsenic in cooked rice: effect of chemical, enzymatic and microbial processes on bioaccessibility and speciation in the human gastrointestinal tract. Environ. Pollut 162 (Suppl. C), 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulve NS, et al. , 2002. Frequency of mouthing behavior in young children. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol 12 (4), 259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner A, Ip K-H, 2007. Bioaccessibility of metals in dust from the indoor environment: application of a physiologically based extraction test. Environ. Sci. Technol 41 (22), 7851–7856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2007. Guidance for evaluating the oral bioavailability of metals in soils for use in human health risk assessment. In: OSWER 9284. USEPA. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2015a. Guidance for sample collection for in vitro bioaccessibility assay for lead (Pb) in soil. In: OSWER 9200.3–100. USEPA. USEPA. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2015b. Relative Bioavailability of Arsenic in the Flat Creek Soil Reference Material.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2017a. Method 1340: in vitro bioaccessibility assay for lead in soil. In: SW-846 Update VI. USEPA. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2017b. In: Validation Assessment of in Vitro Arsenic Bioaccessibility Assay for Predicting Relative Bioavailability of Arsenic in Soils and Soil-like Materials at Superfund Sites. O.o.L.a.E. Management

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2017. In: Innovation, o.S.R.a.T. (Ed.), In Vitro Bioaccessibility Reference Materials For Lead and Arsenic Round Robin Study Report O.

- Van de Wiele T, et al. , 2010. Arsenic Metabolism by Human Gut Microbiota upon in Vitro Digestion of Contaminated Soils. Environmental health perspectives, pp. 1004–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Van de Wiele T, et al. , 2015. The simulator of the human intestinal microbial Ecosystem (SHIME®). In: Verhoeckx K, et al. (Eds.), The Impact of Food Bioactives on Health: in Vitro and Ex Vivo Models. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann I, et al. , 2006. The mode of action of the lantibiotic lacticin 3147 – a complex mechanism involving specific interaction of two peptides and the cell wall precursor lipid II. Mol. Microbiol 61 (2), 285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2018. Arsenic. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/arsenic. (Accessed 11 December 2018).

- Xue J, et al. , 2007. A meta-analysis of children’s hand-to-mouth frequency data for estimating nondietary ingestion exposure. Risk Anal. 27 (2), 411–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin N, et al. , 2017a. Interindividual variability of soil arsenic metabolism by human gut microbiota using SHIME model. Chemosphere 184, 460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin N, et al. , 2017b. In vitro study of soil arsenic release by human gut microbiota and its intestinal absorption by Caco-2 cells. Chemosphere 168, 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.