Abstract

Rationale

E-cigarette– or vaping-associated lung injury (EVALI) was first identified in 2019. The long-term respiratory, cognitive, mood disorder, and vaping behavior outcomes of patients with EVALI remain unknown.

Objectives

To determine the long-term respiratory, cognitive, mood disorder, and vaping behavior outcomes of patients with EVALI.

Methods

We prospectively enrolled patients with EVALI from two health systems. We assessed outcomes at 1 year after onset of EVALI using validated instruments measuring cognitive function, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, respiratory disability, coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infection, pulmonary function, and vaping behaviors. We used multivariable regression to identify risk factors of post-EVALI vaping behaviors and to identify whether admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) was associated with cognitive, respiratory, or mood symptoms.

Results

Seventy-three patients completed 12-month follow-up. Most patients were male (66.7%), young (mean age, 31 ± 11 yr), and White (85%) and did not need admission to the ICU (59%). At 12 months, 39% (25 of 64) had cognitive impairment, whereas 48% (30 of 62) reported respiratory limitations. Mood disorders were common, with 59% (38 of 64) reporting anxiety and/or depression and 62% (39 of 63) having post-traumatic stress. Four (6.4%) of 64 reported a history of COVID-19 infection. Despite the history of EVALI, many people continued to vape. Only 38% (24 of 64) reported quitting all vaping and smoking behaviors. Younger age was associated with reduced vaping behavior after EVALI (odds ratio, 0.93; P = 0.02). ICU admission was not associated with cognitive impairment, dyspnea, or mood symptoms.

Conclusions

Patients with EVALI, despite their youth, commonly have significant long-term respiratory disability; cognitive impairment; symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress; and persistent vaping.

Keywords: vaping, e-cigarettes, EVALI, e-cigarette– or vaping-associated lung injury, long-term outcome

E-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) was first recognized in 2019 amid reports of young people developing severe respiratory failure after vaping (1–3). As EVALI cases accumulated, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defined EVALI as the presence of bilateral chest infiltrates and exclusion of alternative diagnoses in a patient who had vaped within the preceding 90 days (4). During the subsequent months, EVALI was better characterized, including its association with vaping tetrahydrocannabinol (THC); its rapid clinical response to corticosteroids (5); and that vitamin E acetate, an adulterant in THC-containing e-cigarettes, was a likely culprit driving the acute outbreak (6–9). By the start of 2020, the diagnosis of EVALI cases had substantially decreased, likely as a result of federal efforts to curb illicit cartridge distribution and increased public recognition of vaping-related lung injury (10).

Despite the progress in understanding and classifying EVALI, questions remain. Understanding the long-term outcomes of patients with EVALI is a challenge. Long-term sequelae of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) of other causes are well characterized as the post–intensive care syndrome (PICS). PICS was defined by consensus in 2012 as new or worsening problems in physical, cognitive, or mental health status after critical illness and persisting beyond the acute hospitalization (11). However, patients with EVALI are, on average, younger and healthier than patients with ARDS of other causes. More recently, with the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, young people have experienced ARDS because of COVID-19 at previously unprecedented rates, and anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms were common (7–23%) (12).

Small retrospective studies have shown some residual symptoms and pulmonary function test (PFT) abnormalities that resolved (13). It is unknown whether these patients fully recover or if they have long-term deficits, such as PICS. We sought to characterize 12-month cognitive function, dyspnea, lung function, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, and prevalence of COVID-19 infection among survivors of EVALI.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

This is a prospective cohort study of all patients diagnosed with EVALI in two health systems in the Intermountain West (Utah, Idaho, and Nevada) between June 1, 2019, and August 15, 2021. The institutional review board at Intermountain Healthcare (the single institutional review board for this multicenter study; 1051380) approved the study, and individual informed consent was obtained.

All clinical EVALI diagnoses were validated by the Utah EVALI Taskforce by consensus based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria (4). After March 1, 2020, a negative severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) test result was required for an EVALI diagnosis, corresponding to the test’s availability in these states. All patients with EVALI were screened for participation in this cohort. Patients who had died or declined to participate were not included. In addition, because of lack of survey availability in other languages, only patients who understood English were included. People who were incarcerated were also excluded from the study. We included all patients with EVALI, regardless of whether they were diagnosed and treated in the outpatient setting, the hospital ward, or the intensive care unit (ICU) to capture the long-term outcomes of these patients attributable to EVALI rather than focusing only on long-term outcomes of patients with ARDS.

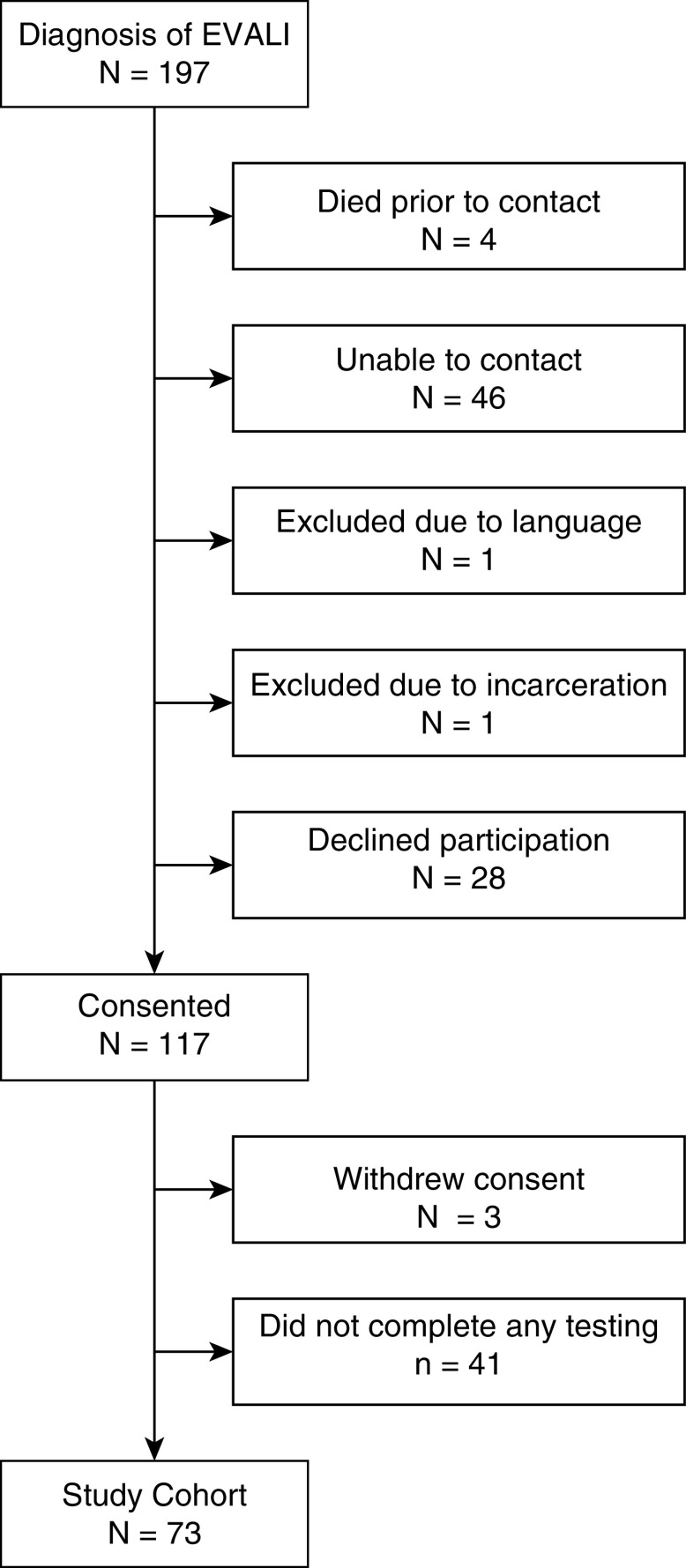

Subjects were contacted after their EVALI diagnosis and could be enrolled in the study at any time up to 12 months after their EVALI diagnosis. If they were enrolled more than 3 months after their EVALI diagnosis, they would only be offered the 12-month surveys. Patients were contacted via text, e-mail, or telephone with reminders to complete surveys. Surveys were administered at 12 months after EVALI diagnosis. PFTs were scheduled at 12 months after EVALI diagnosis. Pandemic-related delays in PFT availability and preprocedural testing limited PFT completion and timing, and extension up to 24 months after EVALI diagnosis was included. All subjects who completed at least one 12-month follow-up after EVALI diagnosis were included for analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram of enrollment for patients with e-cigarette– or vaping-associated lung injury (EVALI).

Variables, Data Sources, and Measurements

We employed a battery of tests with large experience among survivors of ARDS that were part of the Core Outcome Measurement Set (14). Cognitive impairment was assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) blind test, which was administered via telephone by research assistants trained in MoCA administration. The data were checked and results overseen by a trained psychology professional (R.O.H.). Patients were considered to have possible cognitive impairment if they had MoCA scores ⩽25 (15).

Respiratory symptoms were assessed by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) (16) with domains including symptoms, activity, impacts, and total, as well as by the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea score (16). A categorical variable based on SGRQ score ⩾25 for impaired was used in some analyses to determine co-occurrence of symptoms and impacts (17).

Mood symptoms of anxiety and depression were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) score, with scores ⩾8 on the subscales indicating depression or anxiety (18). The Impact of Event Scale–Revised was used to assess symptoms of post-traumatic stress (19, 20), with an overall mean score ⩾1.6 considered abnormal. Additional questions regarding COVID-19 diagnosis and assessments of admission location (ICU, hospital ward, emergency department, or outpatient) as well as length of stay via chart review were also included.

Statistical Methods

We used descriptive statistics to characterize variables. We compared long-term smoking and vaping behaviors with baseline using the McNemar test for significance.

To understand the relationship between post-EVALI vaping and/or smoking behavior and other variables, we analyzed bivariate correlations between vaping and/or smoking behavior (yes or no) and explanatory variables. The explanatory variables were age, sex, HADS depression score, HADS anxiety score, SGRQ total score, and MoCA blind total score. These variables were selected a priori for their likely association with vaping and/or smoking behavior.

Variables with bivariate correlation P values ⩽0.10 were considered for binary logistic regression modeling using stepwise backward elimination. We followed the same process to evaluate whether age, sex, and ICU admission were associated with HADS, SGRQ, and MoCA scores.

Results

Participants

Seventy-three patients were included who completed at least one 12-month follow-up between July 20, 2020, and August 15, 2021 (Figure 1). One hundred ninety-seven patients with an EVALI diagnosis 12 or more months before August 15, 2021, were identified. Forty-six patients were not able to be reached, 28 declined, 4 died, and 2 were excluded (incarcerated and language barrier), leaving 117 patients consented for the study. Three patients withdrew consent before testing, and 41 patients did not complete a single 12-month assessment, leaving 73 patients who completed at least one 12-month outcome measurement (Figure 1). A histogram of patients by month of enrollment is shown in Figure 2.

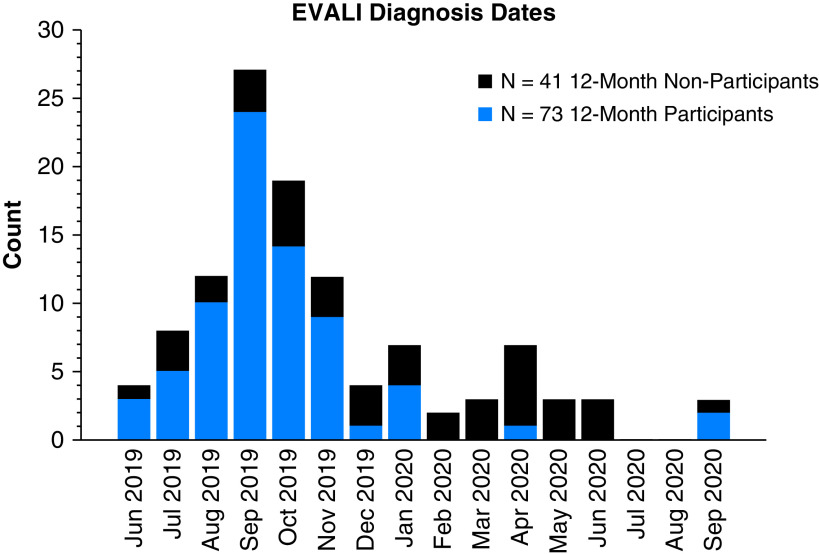

Figure 2.

Histogram of patients diagnosed with e-cigarette– or vaping-associated lung injury (EVALI) between June 2019 and September 2020, both for patients who completed the survey portion of the study and for patients who did not.

Descriptive Data

Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients with EVALI were mostly male (49 of 73; 67.1%), young (mean age, 30.9 yr; standard deviation, 10.9). Many (14 of 64; 19.2%) were Hispanic, and most (62 of 64; 84.9%) were White.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics

| Measure | All Participants (N = 73) | Outpatient (Ambulatory and ED) (n = 13) | Inpatient (Ward and ICU) (n = 60) | Nonparticipants (n = 41) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex, n (%) | 24 (32.9) | 4 (30.8) | 20 (33.3) | 16 (39.0) |

| Age, yr | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 30.9 (10.9) | 31.9 (10.9) | 30.7 (11.0) | 33.9 (11.9) |

| Min–max | 16–66 | 18–51 | 18–66 | 19–65 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.4 (7.0) | 27.2 (7.0) | 28.7 (7.0) | 28.0 (7.9) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) |

| Asian | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) |

| White | 62 (84.9) | 12 (92.3) | 50 (83.3) | 39 (95.1) |

| Black or African American | 2 (2.7) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.4) |

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| More than one race | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0) |

| Not reported/unknown | 5 (6.8) | 0 (0) | 5 (8.3) | 1 (2.4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 58 (79.5) | 11 (84.6) | 47 (78.3) | 35 (85.4) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 14 (19.2) | 2 (15.4) | 12 (20.0) | 6 (14.6) |

| Not reported/unknown | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) |

| Highest education level, n (%) | ||||

| Responded | 65 (89.0) | 11 (84.6) | 54 (90.0) | 21 (51.2) |

| Less than high school | 16 (24.6) | 3 (27.3) | 13 (24.1) | 3 (14.3) |

| High school diploma | 20 (30.8) | 3 (27.3) | 17 (31.5) | 10 (47.6) |

| Some college or more | 29 (44.6) | 5 (45.5) | 24 (44.4) | 8 (38.1) |

| Severity of illness | ||||

| Highest level of care, n (%) | ||||

| Ambulatory | 2 (2.7) | 2 (15.4) | — | 1 (2.4) |

| ED | 11 (15.1) | 11 (84.6) | — | 3 (7.3) |

| Hospital ward | 30 (41.1) | — | 30 (50.0) | 15 (36.6) |

| ICU | 30 (41.1) | — | 30 (50.0) | 22 (53.7) |

| Inpatient LOS, d | — | |||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 5.0 (3.0–7.3) | — | 5.0 (3.0–7.3) | 4.1 (3.1–7.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 6.2 (5.0) | — | 6.2 (5.0) | 5.1 (3.1) |

| Min–max | 0.9–29.9 | — | 0.9–29.9 | 1.7–15.6 |

| ICU LOS, d | — | |||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 4.0 (2.6–6.7) | — | 4.0 (2.6–6.7) | 2.0 (1.8–4.4) |

| Mean (SD) | 5.0 (3.4) | — | 5.0 (3.4) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Min–max | 0.7–15.0 | — | 0.7–15.0 | 0.6–7.8 |

| 12-mo PFTs | ||||

| ⩾10 mo after EVALI, n (%) | 17 (23.3) | 4 (30.8) | 13 (21.7) | 0 (0) |

| Months since EVALI diagnosis | ||||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 18.7 (13.9–20.5) | 18.3 (14.2–21.3) | 18.7 (13.9–20.1) | — |

| Min–max | 10.6–22.9 | 13.6–21.5 | 10.6–22.9 | — |

| Medical facility, n (%) | ||||

| Intermountain Healthcare | 56 (76.7) | 11 (84.6) | 45 (75.0) | 37 (90.2) |

| University of Utah | 17 (23.3) | 2 (15.4) | 15 (25.0) | 4 (9.8) |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; ED = emergency department; EVALI = e-cigarette– or vaping-associated lung injury; ICU = intensive care unit; LOS = length of stay; max = maximum; min = minimum; PFT = pulmonary function test; SD = standard deviation.

Although many patients were sick enough with their EVALI diagnosis to require an admission to the ICU (30 of 73; 41.1%), the majority did not need an ICU admission, and 18.8% (13 of 73) did not require hospital admission. Median inpatient length of stay was 5.0 days with an interquartile range (IQR) of 0.3 to 7.3 days.

Twenty-three percent of patients (17 of 73) completed their 12-month PFTs (Table 2). A self-reported COVID-19 illness diagnosis confirmed by testing was present in 6.3% (4 of 64) of patients in the interval period. None reported that they were hospitalized for that infection.

Table 2.

Pulmonary function test results

| Measure | 12-Mo PFT (n = 17) |

|---|---|

| FEV1 (% predicted) | |

| Completed, n (%) | 15 (88.2) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 95.0 (82.0–105.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 95.1 (12.8) |

| Min–max | 79.0–116.0 |

| FVC (% predicted) | |

| Completed, n (%) | 15 (88.2) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 106.0 (97.0–111.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 105.5 (12.0) |

| Min–max | 84.0–127.0 |

| FEV1/FVC | |

| Completed, n (%) | 15 (88.2) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 76.5 (65.9–80.4) |

| Mean (SD) | 74.0 (9.0) |

| Min–max | 58.5–89.1 |

| DlCO (% predicted) | |

| Completed, n (%) | 17 (100) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 108.0 (85.5–126.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 106.8 (27.5) |

| Min–max | 55.0–155.0 |

Definition of abbreviations: DlCO = diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC = forced vital capacity; max = maximum; min = minimum; PFT = pulmonary function test; SD = standard deviation.

Outcome Data

Cognitive impairment, dyspnea, and anxiety and/or depression

The clinical outcomes at 12 months are summarized in Table 3. Twelve months after EVALI diagnosis, 39.1% (25 of 64) of subjects had cognitive impairment, 48.4% (30 of 62) of subjects had respiratory impairment, and 59.4% (38 of 64) of subjects had symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Post-traumatic stress symptoms associated with the EVALI diagnosis were also present in 61.9.5% (40 of 63).

Table 3.

Clinical and behavioral outcomes at 12 months after e-cigarette– or vaping-associated lung injury diagnosis

| Measure | 12 Mo (N = 73) | 12 Mo, Inpatient (Ward and ICU) (n = 60) | 12 Mo, Outpatient (ED and Ambulatory) (n = 13) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoCA blind total | |||

| Responded, n (%) | 64 (87.7) | 53 (88.3) | 11 (84.6) |

| Min–max | 17.7–30.0 | 17.7–30.0 | 20.5–30.0 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.1 (3.1) | 25.9 (3.1) | 26.9 (2.9) |

| ⩽25, impaired, n (%) | 25 (39.1) | 23 (43.4) | 2 (18.2) |

| >25, normal, n (%) | 39 (60.9) | 30 (56.6) | 9 (81.8) |

| SGRQ | |||

| Responded, n (%) | 62 (84.9) | 52 (86.7) | 12 (92.3) |

| Symptoms, mean (SD) | 37.1 (32.9) | 37.8 (32.7) | 33.6 (32.0) |

| Activity | 35.4 (30.2) | 36.7 (30.0) | 32.2 (35.6) |

| Impact | 25.0 (25.7) | 27.1 (26.1) | 20.2 (27.3) |

| Total | 30.3 (26.7) | 31.7 (26.6) | 26.0 (29.8) |

| <25, normal, n (%) | 32 (51.6) | 26 (50.0) | 7 (58.3) |

| ⩾25, impaired, n (%) | 30 (48.4) | 26 (50.0) | 5 (41.7) |

| mMRC scale score | |||

| Responded, n (%) | 64 (87.7) | 54 (90.0) | 10 (76.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.92 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.2) | 0.50 (1.0) |

| Grade, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 30 (46.9) | 23 (42.6) | 7 (70.0) |

| 1 | 22 (34.4) | 20 (37.0) | 2 (20.0) |

| 2 | 2 (3.1) | 2 (3.7) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 7 (10.9) | 6 (11.1) | 1 (10.0) |

| 4 | 3 (4.7) | 3 (5.6) | 0 (0) |

| 0–1, normal, n (%) | 52 (81.3) | 43 (79.6) | 9 (90.0) |

| 2–4, dyspnea, n (%) | 12 (18.8) | 11 (20.4) | 1 (10.0) |

| HADS total | |||

| Responded, n (%) | 64 (87.7) | 54 (90.0) | 10 (76.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 14.7 (9.2) | 14.8 (9.3) | 14.3 (9.1) |

| ⩾8, anxiety/depression, n (%) | 38 (59.4) | 32 (59.3) | 6 (60.0) |

| HADS anxiety | |||

| Responded, n (%) | 64 (87.7) | 54 (90.0) | 10 (76.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 9.1 (5.4) | 9.2 (5.5) | 8.7 (5.5) |

| ⩾8, n (%) | 36 (56.3) | 31 (57.4) | 5 (50.0) |

| ⩾11, n (%) | 25 (39.1) | 21 (38.9) | 4 (40.0) |

| HADS depression | |||

| Responded, n (%) | 64 (87.7) | 54 (90.0) | 10 (76.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 5.6 (4.6) | 5.6 (4.7) | 5.6 (4.6) |

| ⩾8, n (%) | 22 (34.4) | 17 (31.5) | 5 (50.0) |

| ⩾11, n (%) | 8 (12.5) | 7 (13.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| IES-R | |||

| Responded, n (%) | 63 (86.3) | 53 (88.3) | 10 (76.9) |

| Avoidance, mean (SD) | 2.0 (0.9) | 2.1 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.5) |

| Intrusion | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.2 (1.1) | 1.7 (0.8) |

| Hyperarousal | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.1) | 1.6 (0.8) |

| Total sum | 45.7 (19.9) | 47.6 (20.3) | 35.6 (14.7) |

| Total mean | 2.1 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.7) |

| <1.6, normal, n (%) | 24 (38.1) | 18 (34.0) | 6 (60.0) |

| ⩾1.6, PTSD, n (%) | 39 (61.9) | 35 (66.0) | 4 (40.0) |

| Reported COVID-19 infection, n (%) | |||

| Responded | 64 (87.7) | 54 (90.0) | 10 (76.9) |

| Yes | 4 (6.3) | 4 (7.4) | 0 (0) |

| Hospitalized | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| No | 55 (85.9) | 46 (85.2) | 9 (90.0) |

| Unsure | 5 (7.8) | 4 (7.4) | 1 (10.0) |

Definition of abbreviations: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease; ED = emergency department; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICU = intensive care unit; IES-R = Impact of Event Scale–Revised; max = maximum; min = minimum; mMRC = modified Medical Research Council; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; SD = standard deviation; SGRQ = St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

To determine the co-occurrence of symptoms of dyspnea, anxiety/depression, and cognitive impairment among patients, we assessed the 46 subjects who had complete data for respiratory symptoms, anxiety and depression, and cognitive impairment (see Figure E1 in the data supplement). Nearly one-fourth of patients had cognitive impairment, dyspnea, and mood symptoms (11 of 46; 23.3%), whereas 15.2% (7 of 46) had cognitive impairment without dyspnea and/or mood symptoms.

Dyspnea and anxiety and/or depression symptoms frequently occurred together. Twenty-five (86.2%) of 29 patients with dyspnea had anxiety and/or depression symptoms, whereas 25 (71.4%) of 35 patients with anxiety and/or depression reported dyspnea.

There was no association between ICU admission, either by itself or in multivariable regressions that included age and sex, and cognitive impairment, dyspnea, or mood symptoms. Although age and sex were not associated with cognitive impairment, male sex was associated with lower anxiety HADS scores (less anxiety) (β = −3.73 compared with female sex; P = 0.017) and lower SGRQ scores (less dyspnea) (β = −20.0; P = 0.003).

Binary logistic regression for reduced smoking or vaping behavior was significant for age in both the whole cohort (n = 73; odds ratio [OR], 0.93; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.89–0.99; P = 0.02) and when only inpatients were considered (n = 60; OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.87–0.99; P = 0.02). The results of regressions to predict ICU admission were not significant for both the whole cohort and inpatients only. SGRQ abnormality was not significantly predicted by our explanatory variables in the whole cohort, but it was significantly predicted by age in the inpatient-only cohort (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01–1.15; P = 0.02). For each year increase in age, the likelihood of abnormal SGRQ survey results increased by 8%.

When we considered inpatients only (n = 60), there was still no association between our explanatory variables and ICU admission or vaping behavior in multivariable logistic regression. Dyspnea symptoms (abnormal SGRQ) were not significantly predicted by explanatory variables in the whole cohort, but they were significantly predicted by age in the inpatient only cohort (OR, 1.08; P = 0.02). For each year increase in age, the likelihood of an abnormal SGRQ survey result increased by 8%.

Severe dyspnea impairment as assessed by the mMRC score of 2–4 was present in 18.8% (12 of 64). At 12 months after an EVALI diagnosis, PFTs were within predicted limits. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second for the group had a normal median (95% predicted, 82–105% predicted IQR). Forced vital capacity was likewise normal, with a median 106% predicted (IQR, 97–111% predicted). Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide was also normal with median 108% predicted (IQR, 86–126% predicted).

Vaping and smoking behavior

We assessed pre- and post-EVALI vaping and smoking behaviors. Table 4 and Tables E2 and E3 summarize the pre- and post-EVALI use of nicotine and/or THC through vaping and/or smoking.

Table 4.

Self-reported smoking and vaping behaviors of nicotine and tetrahydrocannabinol before and 12 months after e-cigarette– or vaping-associated lung injury

| Smoking/Vaping Behavior | 12-Mo Patients Responding, 64 of 73 (87.7%) | Nicotine E-Cigarettes |

THC/CBD E-Cigarettes |

Tobacco Cigarettes |

Combustible Marijuana |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stopped | Still Using | Stopped | Still Using | Stopped | Still Using | Stopped | Still Using | ||

| Nicotine e-cigarettes, n (%) | 39 of 64 (60.9) | 21 (53.8) | 18 (46.2) | 28 (71.8) | 11 (28.2) | 31 (79.5) | 8 (20.5) | 22 (56.4) | 17 (43.6) |

| THC or CBD e-cigarettes, n (%) | 52 of 64 (81.3) | 40 (76.9) | 12 (23.1) | 39 (75.0) | 13 (25.0) | 45 (86.5) | 7 (13.5) | 30 (57.7) | 22 (42.3) |

| Tobacco cigarettes, n (%) | 25 of 64 (39.1) | 18 (72.0) | 7 (28.0) | 22 (88.0) | 3 (12.0) | 14 (56.0) | 11 (44.0) | 12 (48.0) | 13 (52.0) |

| Combustible marijuana, n (%) | 46 of 64 (71.9) | 32 (69.6) | 14 (30.4) | 35 (76.1) | 11 (23.9) | 38 (82.6) | 8 (17.4) | 21 (45.7) | 25 (54.3) |

Definition of abbreviations: CBD = cannabidiol; THC = tetrahydrocannabinol.

There was a significant reduction in vaping and smoking behavior after an EVALI diagnosis. For example, nicotine e-cigarette use dropped from 61% (39 of 64) before EVALI to 28% (18 of 64) after EVALI (P < 0.001), and THC e-cigarette use dropped from 81% (52 of 64) to 18.8% (12 of 64) (P < 0.001) (Table 4). Overall, although most patients decreased their vaping and/or smoking behavior, only 37.5% of patients (24 of 64) quit all vaping and/or smoking after an EVALI diagnosis (Table E3).

We evaluated factors associated with quitting or reducing vaping and/or smoking behaviors. We examined whether age, sex, HADS anxiety score, SGRQ total score, and MoCA score were associated with reducing vaping and smoking behaviors or quitting all such behaviors. We found that younger age was significantly associated (OR, 0.93; P = 0.02) with reducing vaping or smoking behavior. We did not observe an association between these five factors and complete cessation of vaping or smoking behavior.

We recorded free-text qualitative responses regarding whether patients attempted to reduce or stop vaping. Representative comments include, “I have tried to cut down, but I still vape every day”; “No. I just vape nicotine”; “Sadly, no I have not [changed vaping behavior post-EVALI diagnosis]”; “Yes, at first I was careful with nicotine patches, but now I just vape again”; and “Yes, I don’t vape anymore. I just use cigarettes and nicotine patches.” Some referenced changing the sourcing of their vaping after EVALI diagnosis: “Yes, [changed] my dealer”; “Reduced frequency, only buy authorized products”; “Only buy regulated and use it rarely”; “Only use disposable”; and “Being smarter about it lol.”

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to prospectively assess the long-term outcomes in a cohort of patients after an EVALI diagnosis. Long-term impairments of EVALI are both common and severe. The cognitive, dyspnea, and mood impairments in these patients are remarkable, considering that the patients with EVALI are young and relatively healthy and that the majority did not need ICU admission.

At 12 months after an EVALI diagnosis, 39.1% of patients have cognitive impairment, 48.5% have respiratory limitations measured by symptom scores, 54.3% have anxiety and/or depression, and 63.5% have post-traumatic stress. Although most patients with an EVALI diagnosis reduced their vaping and smoking behaviors, only 37.5% were able to cease vaping and smoking completely.

Despite being younger and healthier than patients with acute lung injury of other causes, patients with EVALI experience serious long-term complications comparable to those of others with PICS after acute lung injury. The 39.1% rate of cognitive impairment in this EVALI cohort is comparable to the cognitive impairment seen in other ICU survivors (34% for a recent cohort of ICU survivors younger than 50 yr old at 12 mo [21] and as high as 55% in a cohort that includes older patients [22]). Similarly, respiratory symptoms (23), mood disorder symptoms (22, 24), and post-traumatic stress (22) were similar in prevalence to other cohorts of ICU survivors.

During the past 2 years, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the mental health of many people, even those who did not get sick with COVID-19. It is challenging to understand the high prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with EVALI in the setting of these secular changes in baseline prevalence. Still, comparing the outcomes in patients with EVALI with those of patients who have recovered from COVID-19 infection may put these findings in context. In a study of patients screened for symptoms 4 months after COVID-19 infection, anxiety symptoms (34%), depression (21%), and post-traumatic stress symptoms (14%) were common (12). Importantly, the prevalence of cognitive impairment in these patients was 38% when assessed by MoCA score, which is similar to the rates we found for patients with EVALI at 12 months (39%).

Our prospective study identified cognitive impairment, dyspnea, and mood disorders in a large cohort of patients with EVALI. Although other studies have examined electronic health record data only with variable follow-up, they, too, have found normal PFT results and persistent vaping at follow-up (13). In this largest electronic health record study to date of 41 patients with EVALI, pulmonary symptoms were noted in 21% of patients, 14% had decreased exercise capacity, and 10% had cough (13). Although the prevalence of respiratory symptoms (abnormal SGRQ) and dyspnea was higher in our study (48.5%), this increase may be due to the assessment of respiratory symptoms via surveys rather than reliance on patients seeking health care and assessment of clinical notes. Furthermore, the rate of dyspnea as assessed by abnormal mMRC scores (2–4) in our study (18.8%) is comparable to the rate of decreased exercise capacity in the study by Triantafyllou and colleagues (14%) (13).

The ramifications of cognitive, physical, and psychological impairment in a cohort of patients with an average age of 31 years, the majority of whom did not even require admission to the ICU, are staggering. In addition, the self-reported difficulty of study participants to give up smoking and vaping are concerning for continued functional decline in these individuals.

The difficulty in quitting vaping and/or smoking behavior even after an EVALI diagnosis suggests that we are at the start of a different pandemic: E-cigarette use/vaping has rapidly escalated, especially among young people. One encouraging finding is that younger age was associated with increased odds of reducing vaping and/or smoking behavior. As such, efforts aimed at preventing young people from starting to vape or smoke, as well as supporting them to quit vaping and smoking, are important in trying to limit the harm from these behaviors and to protect young people. Importantly, access to mental health resources to facilitate treatment of anxiety and depression beyond marijuana use is paramount to this population’s well-being. The inability or unwillingness of many EVALI survivors to quit harmful behaviors despite severe risk during both the initial EVALI disease and in the long term underscores the need for greater efforts in smoking and vaping cessation. Some, including physicians, have promoted vaping as a safe and effective substitute for smoking (25), despite conflicting evidence for its success (26). Our study should serve as an additional caution regarding the potential long-term harms of vaping.

Although this study enrolled a large cohort of patients with EVALI and used validated scales to quantify cognitive, respiratory, and mood disorders, limitations remain. First, these results include data from only 73 participants of the 197 patients diagnosed with EVALI. Although this rate of follow-up is not unusual for this age group and in studies of addiction, it does limit inferences (27). Second, there is no control group for comparison, and there are no baseline data for these patients before their EVALI diagnosis. Although the population of patients with EVALI was relatively young and had few reported comorbidities, no comparisons with patients’ states before their EVALI diagnosis are possible. Thus, a clear causal link between the high prevalence of cognitive and pulmonary limitations with the EVALI diagnosis cannot be established. Third, this study comprises two health systems in the Intermountain West, and patterns of vaping or smoking and e-cigarette supply chain issues (particularly illicit e-cigarettes) likely result in significant regional variation of exposures and patterns of consumption. In addition, cognitive outcomes were assessed using the MoCA score via telephone, and in-depth neurological evaluations, imaging, or formal neurocognitive testing were not feasible. Last, this study may be subject to volunteer bias, with subjects experiencing symptoms being more likely to volunteer for a study assessing these symptoms. Thus, it is possible that participants who completed the surveys at 12 months or underwent PFTs have more severe impairment than those who did not complete the study.

Patients diagnosed with EVALI, even those who are not critically ill, often have serious and long-lasting consequences, including cognitive, respiratory, and mood disorders as well as ongoing vaping and smoking behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to their patients and the dedicated research assistants and clinical research team members who were instrumental in the completion of this study: Mikaele Bown, Mardee Merrill, Amy Denardo, Carlos Barbagelata, and Lisa Weaver.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (3U01HL123018-06S1) and the Intermountain Research and Medical Foundation (AWD01126). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or Intermountain Healthcare.

Author Contributions: Conceived of and designed the study: D.P.B., D.H., M.J.L., S.B., S.J.C., and R.O.H. Funding acquisition: D.P.B., S.B., and M.J.L. Project administration: V.A. and L.W. Supervision: V.A., L.W., D.P.B., and S.J.C. Writing – original draft: D.P.B. Writing – review and editing: all authors. Data curation: D.H., J.R.E., V.A., and L.W. Formal analysis: D.S.C., D.P.B., M.J.L., S.J.C. Data analysis: D.P.B., D.S.C., S.J.C., R.O.H., and M.J.L. Had full access to all the data and takes full responsibility for this study: D.P.B.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Layden JE, Ghinai I, Pray I, Kimball A, Layer M, Tenforde MW, et al. Pulmonary illness related to E-cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin — final report. N Engl J Med . 2020;382:903–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maddock SD, Cirulis MM, Callahan SJ, Keenan LM, Pirozzi CS, Raman SM, et al. Pulmonary lipid-laden macrophages and vaping. N Engl J Med . 2019;381:1488–1489. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1912038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Henry TS, Kanne JP, Kligerman SJ. Imaging of vaping-associated lung disease. N Engl J Med . 2019;381:1486–1487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1911995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schier JG, Meiman JG, Layden J, Mikosz CA, VanFrank B, King BA, et al. CDC 2019 Lung Injury Response Group Severe pulmonary disease associated with electronic-cigarette-product use — interim guidance. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2019;68:787–790. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6836e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blagev DP, Harris D, Dunn AC, Guidry DW, Grissom CK, Lanspa MJ. Clinical presentation, treatment, and short-term outcomes of lung injury associated with e-cigarettes or vaping: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet . 2019;394:2073–2083. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32679-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Morel-Espinosa M, Rees J, Sosnoff C, Cowan E, et al. Evaluation of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients in an outbreak of E-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury — 10 states, August–October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2019;68:1040–1041. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, Morel-Espinosa M, Valentin-Blasini L, Gardner M, et al. Lung Injury Response Laboratory Working Group Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med . 2020;382:697–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taylor J, Wiens T, Peterson J, Saravia S, Lunda M, Hanson K, et al. Lung Injury Response Task Force Characteristics of e-cigarette, or vaping, products used by patients with associated lung injury and products seized by law enforcement — Minnesota, 2018 and 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2019;68:1096–1100. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6847e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhat TA, Kalathil SG, Bogner PN, Blount BC, Goniewicz ML, Thanavala YM. An animal model of inhaled vitamin E acetate and EVALI-like lung injury. N Engl J Med . 2020;382:1175–1177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with the Use of E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products [updated 2020 February 25; accessed 2022 March 15]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html.

- 11. Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med . 2012;40:502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morin L, Savale L, Pham T, Colle R, Figueiredo S, Harrois A, et al. Writing Committee for the COMEBAC Study Group Four-month clinical status of a cohort of patients after hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA . 2021;325:1525–1534. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Triantafyllou GA, Tiberio PJ, Zou RH, Lynch MJ, Kreit JW, McVerry BJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of EVALI: a 1-year retrospective study. Lancet Respir Med . 2021;9:e112–e113. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00415-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Friedman LA, Bingham CO, III, et al. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors. An international modified Delphi consensus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2017;196:1122–1130. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0372OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown SM, Collingridge DS, Wilson EL, Beesley S, Bose S, Orme J, et al. Preliminary validation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment tool among sepsis survivors: a prospective pilot study. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2018;15:1108–1110. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201804-233OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Respir Med . 1991;85:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsiligianni IG, Alma HJ, de Jong C, Jelusic D, Wittmann M, Schuler M, et al. Investigating sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve of the Clinical COPD Questionnaire, COPD Assessment Test, and Modified Medical Research Council scale according to GOLD using St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire cutoff 25 (and 20) as reference. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis . 2016;11:1045–1052. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S99793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bienvenu OJ, Friedman LA, Colantuoni E, Dinglas VD, Sepulveda KA, Mendez-Tellez P, et al. Psychiatric symptoms after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-year longitudinal study. Intensive Care Med . 2018;44:38–47. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-5009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hosey MM, Bienvenu OJ, Dinglas VD, Turnbull AE, Parker AM, Hopkins RO, et al. The IES-R remains a core outcome measure for PTSD in critical illness survivorship research. Crit Care . 2019;23:362. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2630-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hosey MM, Leoutsakos JS, Li X, Dinglas VD, Bienvenu OJ, Parker AM, et al. Screening for posttraumatic stress disorder in ARDS survivors: validation of the Impact of Event Scale-6 (IES-6) Crit Care . 2019;23:276. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2553-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, et al. BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med . 2013;369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mikkelsen ME, Christie JD, Lanken PN, Biester RC, Thompson BT, Bellamy SL, et al. The adult respiratory distress syndrome cognitive outcomes study: long-term neuropsychological function in survivors of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2012;185:1307–1315. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2025OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Davidson TA, Caldwell ES, Curtis JR, Hudson LD, Steinberg KP. Reduced quality of life in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome compared with critically ill control patients. JAMA . 1999;281:354–360. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orme J, Jr, Romney JS, Hopkins RO, Pope D, Chan KJ, Thomsen G, et al. Pulmonary function and health-related quality of life in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2003;167:690–694. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-542OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rigotti NA. Randomized trials of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation. JAMA . 2020;324:1835–1837. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.18967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pierce JP, Chen R, Kealey S, Leas EC, White MM, Stone MD, et al. Incidence of cigarette smoking relapse among individuals who switched to e-cigarettes or other tobacco products. JAMA Netw Open . 2021;4:e2128810. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harlan LC, Lynch CF, Keegan TH, Hamilton AS, Wu XC, Kato I, et al. AYA HOPE Study Collaborative Group Recruitment and follow-up of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: the AYA HOPE Study. J Cancer Surviv . 2011;5:305–314. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0173-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]