Abstract

Background:

Understanding factors promoting symptom severity is essential to developing innovative symptom management models.

Purpose:

Investigate hot flash severity during the menopausal transition (MT) and early postmenopause (PM) and effects of age, MT stages, age of onset of late stage and final menstrual period (FMP), estrogen, FSH), cortisol, anxiety, perceived stress, BMI, smoking, alcohol use and exercise.

Methods:

A subset of Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study participants (n= 291 with up to 6973 observations) provided data during the late reproductive, early and late MT stages and early PM, including menstrual calendars, annual health questionnaires, and symptom diaries and urine specimens assayed for hormones several times per year. Multilevel modeling with an R program was used to test models accounting for hot flash severity.

Results:

Hot flash severity persisted through the MT stages and peaked during the late MT stage, diminishing after the second year PM. In individual analyses hot flash severity was associated with being older, being in the late MT stage or early PM, beginning the late MT stage at a younger age and reporting greater anxiety. In a model including only endocrine factors, hot flash severity was significantly associated with higher FSH and lower estrone levels. An integrated model revealed dominant effects of late MT stage and early PM with anxiety contributing to hot flash severity.

Conclusions and Implications:

Hot flash severity was affected largely by reproductive aging and anxiety, suggesting symptom management models that modulate anxiety and enhance women’s experience of the menopausal transition and early PM.

Keywords: hot flashes, anxiety, menopause

The prevalence of hot flashes during the menopausal transition (MT) and early postmenopause (PM) is well-established, with an estimated 75 to 85 % of women reported experiencing them.1–4 Although the prevalence of hot flashes is an important parameter measured in epidemiologic studies such as the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN),3 dimensions other than symptom prevalence are informative about women’s experiences. During the last decades investigators have begun to focus on frequency, bother and severity of hot flashes, 1,2 including some clinical trials.5–7 The frequency of hot flashes is often assessed as the number of hot flashes per day or number of days per week when women experience hot flashes.3 Although useful as an indicator of the proportion of women experiencing more frequent symptoms, frequency alone provides incomplete information to clinicians and investigators about the potential consequences of hot flashes for a woman’s quality of life. Some investigators instead inquire about the degree to which symptoms bother women or interfere with their activities of daily living.8–9

Less attention has been devoted to the severity of hot flashes during this period of a woman’s life. Studies of symptoms, with the goal of understanding their relationship to self care and use of health services, often include estimates of symptom severity.10 Severity, the perception of the intensity of symptoms, implies the degree to which a symptom might be distressing. Voda’s initial studies of the hot flash revealed that women perceived a high degree of variability in severity of hot flashes, with some describing them as barely noticeable and others as severe, resulting in a distressing experience.11 Perceived severity of symptoms was related to interference with both relationships and work in Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study (SMWHS) participants.12 Because perceived severity of symptoms is likely to influence women’s efforts to manage hot flashes either through self care strategies or seeking care from a health professional, focusing on severity and factors which influence severity is foundational to understanding women’s use of self care and professional care.8

To date a number of studies have examined the association between hot flash severity, estradiol and FSH in relation to women’s progression through the stages of reproductive aging but not the age at which the stages of the MT begin. Freeman and associates found that hot flash severity increased across the MT stages to PM, that estradiol levels were not significant but that variability in estradiol levels was significant. Also, FSH levels were positively associated with hot flash severity in this cohort.2 Similarly, the Melbourne Midlife Women’s Health Project (MMWHP) investigators found that hot flashes were associated with FSH levels.13 Women’s hot flush index scores (severity & frequency) increased with increasing levels of FSH and as they entered the late stage of the MT and early PM. Moreover, the influence of FSH is consistent with findings from the SWAN study in which FSH effects overshadowed those of estradiol.14 None of these studies included age of onset of the MT stages.

Although investigators have studied the relationship of health-related characteristics such as smoking, use of alcohol and exercise to hot flash bother, there is limited understanding of their relationship to estimates of hot flash severity. Guthrie and colleagues found that at baseline, MMWHP participants who reported hot flushes were significantly more likely to have more negative moods, not be in full- or part-time paid work, to smoke, to drink alcohol and to not exercise every day. Over 9 years of follow-up, those who reported bothersome hot flashes were younger, had low levels of exercise and were more likely to smoke.10 In a cross-sectional study of a national sample, Williams and colleagues found that those who were Black, had less education, were unemployed, smoked, and had a higher body mass index (BMI) had more bothersome hot flashes.8 In analyses of data from the SWAN cohort, Thurston found that women who were most bothered by hot flashes were those with poorer health, more negative affect, greater symptom sensitivity, sleep problems, younger age, and African American race.15 In addition, greater body fat was associated with hot flash bother.16

Finally, because stress has been associated with the experience of many types of symptoms, the influence of stress-related factors on hot flash severity warrants attention. Freeman and colleagues found that perceived stress was significantly associated with more severe hot flashes.2,17 In addition, anxiety was significantly associated with the occurrence, severity and frequency of hot flashes.17 Compared with women in the normal anxiety range, women with moderate anxiety were nearly three times more likely, and women with high anxiety were nearly five times more likely, to report hot flashes. Anxiety remained strongly associated with hot flashes after adjusting for MT stage, depressive symptoms, smoking, BMI, estradiol, race, age, and time. In a predictive model, anxiety levels at the previous assessment period and the change in anxiety from the previous assessment period significantly predicted hot flashes.17 Finally, in another study hot flash severity in women in late MT stage or early PM was associated with an increase in cortisol level. This increase was not related to age, age at FMP or years since FMP.18

To date only a few studies of severity of hot flashes have examined age, menopausal transition, health-related and stress-related factors as correlates. In order to examine an integrated model to account for hot flashes, the aims of this study were to

describe severity patterns of hot flashes with respect to age, stages of reproductive aging, estrone, and FSH; and

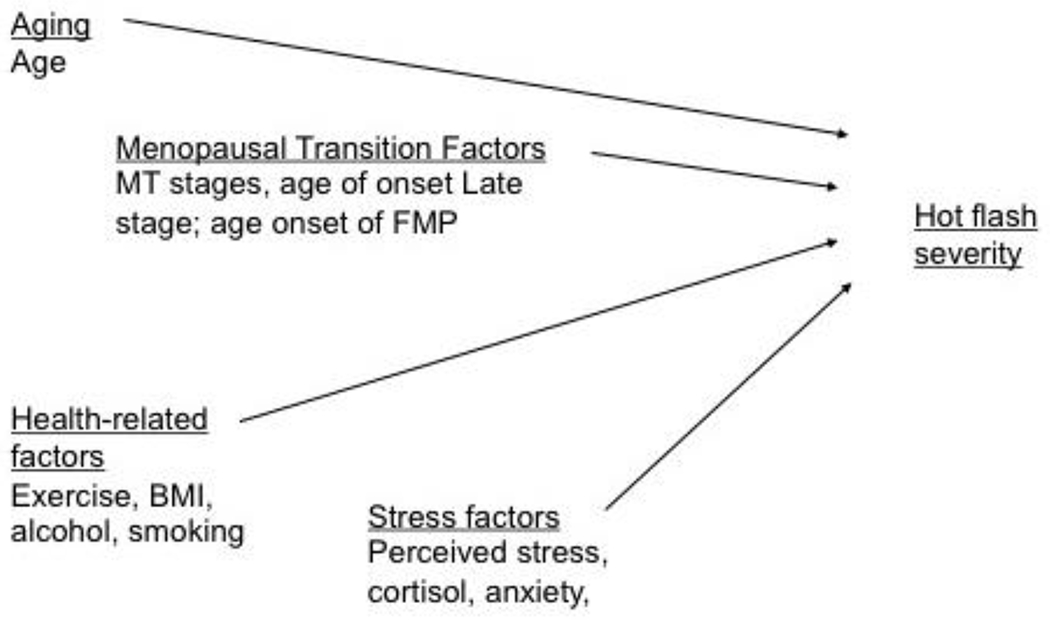

examine changes in hot flash severity level in a multilevel model as it is affected by age, menopausal transition-related factors (MT stages, age at onset of late MT stage, and age at final menstrual period (FMP)), health-related factors (BMI, smoking, drinking alcohol, amount of exercise), and stress-related factors (perceived stress, cortisol and anxiety). (See Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Factors influencing hot flush severity during the menopausal transition (MT) and early postmenopause. FMP, final menstrual period; BMI, body mass index

Methods

Design

The data for these analyses are from a longitudinal study of the MT, the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study (SMWHS), described in detail elsewhere.19 Women entered the cohort between 1990 and early 1992 when most were not yet in the MT or were in the early stages of the transition to menopause. Eligibility for the parent study included ages 35-55, at least one ovary, a period within the previous 12 months, not pregnant or lactating and able to speak and read English. After completing an initial in-person interview (n=508) administered by a trained Registered Nurse interviewer, participants (n=390) began providing data annually by questionnaire, menstrual calendar, and health diary. The health diary included a symptom checklist that included hot flashes, as well as indicators of health behaviors and stress. Diary data were obtained on days 5, 6 and 7 of the menstrual cycle and coincided with first morning voided urine specimens (collected on day 6) that women provided 8 to 12 times per year for endocrine assays (from late 1996 through 2000), and then quarterly for 2001-2005. These data were in addition to an annual health questionnaire and menstrual calendars.

Sample

Eligible participants for this study (N=291) were those who contributed ratings of hot flash severity from the health diaries beginning in 1990 and were in either the late reproductive, early or late MT stages, or within 5 years from FMP during the course of the study. Women not eligible for this study either did not keep a daily diary or were not able to be classified into one of the eligible stages due to hormone use, inadequate calendar data, hysterectomy, chemotherapy or radiation therapy. The women who were eligible for inclusion were midlife women with a mean age of 41.5 (SD=4.3) years at the beginning of the study, 15.9 years of education (SD=2.8), and a median family income of $38,200 (SD=$15,000). Most (87%) of the eligible participants were currently employed, 71% married or partnered, 22% divorced or separated or widowed, and 7% never married or partnered. Eligible women described themselves at the start of the parent study as follows: 7% African American, 9% Asian American, 82% Caucasian. As seen in Table 1, women included in these analyses compared to those who were ineligible were similar with respect to employment status, marital status, and age. They differed significantly by income, ethnicity, and years of education: those who were included in the analyses had higher incomes, more education, and were more likely to be Caucasian. Data obtained during any occasions of hormone use were not included in the analyses presented here.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Start of Study (1990-1991) of the Eligible and Ineligible Women in the Mixed Effects Modeling Analyses of Hot Flash Severity.

| Eligible Women (n=291) | Ineligible Women (n=217) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p value* |

|

| |||

| Age (years) | 41.5 (4.3) | 42.0 (5.0) | 0.18 |

|

| |||

| Years of education | 15.9 (2.8) | 15.3 (3.0) | 0.03 |

|

| |||

| Family income ($) | 38,200 (15,000) 18.6 (7.0) |

35,200 (17,600) 17.1 (8.3) |

0.04 |

|

| |||

| Characteristic | N (Percent) | N (Percent) | p value ** |

|

| |||

| Currently employed | |||

| Yes | 254 (87.3) | 184 (84.8) | 0.40 |

| No | 37 (12.7) | 33 (15.2) | |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicity | .001 | ||

| African American | 20 (6.9) | 38 (17.5) | |

| Asian /Pacific Islander | 27 (9.3) | 16 (7.4) | |

| Caucasian | 238 (81.8) | 153 (70.5) | |

| Other (Hispanic, Mixed) | 6 (2.1) | 10 (4.6) | |

|

| |||

| Marital Status | 0.42 | ||

| Married/partnered | 278 (71.1) | 141 (65.0) | |

| Divorced/widowed/not partnered | 63 (21.7) | 62 (28.6) | |

| Never married/partnered | 21 (7.2) | 14 (6.5) | |

Independent t-test

Chi-square test

Measures

The concepts and measures used in these analyses include: age; MT-related factors (MT stages, age of late stage onset, age at FMP, urinary estrone, and urinary FSH); health-related factors (BMI, smoking, alcohol use and amount of exercise); stress-related factors (perceived stress, cortisol, anxiety) and hot flash severity.

Hot flash severity was assessed in the diary using an item that asked women to rate the severity of their hot flashes on a scale where 1 indicated not present, 2 mild, 3 moderate and 4 extreme.

Menopausal Transition-related factors.

Menopausal transition-related factors included MT stages, age of onset of the late stage and age at FMP, as well as urinary estrone glucuronide and FSH. Using menstrual calendar data, women not taking any type of estrogen or progestogen were classified according to stages of reproductive aging: late reproductive, early MT, late MT, or early PM, based on staging criteria developed by Mitchell, Woods and Mariella20 and validated by the ReSTAGE collaboration.21–23 The names of stages match those recommended at the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW).24 The time before the onset of persistent menstrual irregularity during midlife was labeled the late reproductive stage when cycles were regular. Early stage was defined as persistent irregularity of more than 6 days absolute difference between any two consecutive menstrual cycles during the calendar year, with no skipped periods. Late stage was defined as persistent skipping of one or more menstrual periods. A skipped period was defined as 60 or more consecutive days of amenorrhea during the calendar year.23 Persistence means the event, irregular cycle or skipped period, occurred one or more times in the subsequent 12 months. The date of the first day of the first bleeding segment after the first skipped period was used to calculate age of onset of late stage. Final menstrual period was identified retrospectively after one year of amenorrhea without any known explanation. The date of the FMP is synonymous with the term menopause. This date was used to determine age of onset of FMP. Early PM refers to the years within five years of the FMP.

Urinary Assays.

Urinary assays were performed in our laboratories using a first-voided morning urine specimen provided on day 6 of the menstrual cycle, if menstrual periods were identifiable. For women with no bleeding or spotting or extremely erratic flow, a consistent date each month was used. Women were asked to abstain from smoking, caffeine use, and exercise before the urine collection. All assays were adjusted for urinary creatinine which was assayed in urine specimens using the method of Jaffe25. More assay details are reported elsewhere.19

Urinary estrone glucuronide (E1G) was selected to assess estrogens because it is stable, can be reliably measured without special preparation, and is highly correlated with serum estradiol levels.26–31 Urinary E1G was measured by a competitive enzyme immunoassay (EIA) that cross-reacts 83% with estradiol glucuronide and less than 10% with free estrone, estrone sulfate, estriol glucuronide, estradiol and estriol 26. The assay is described in detail elsewhere. 19

Urinary FSH was assayed using Diagnostic Products Corporation (DPC) Double Antibody FSH Kit, using a radioimmunoassay (RIA) was designed for the quantitative measurement of FSH in serum and urine.32 The procedure is described in detail elsewhere.18

Health-related factors.

Health-related factors included women’s smoking status, use of alcohol, amount of exercise and BMI. Women were asked to indicate in the daily health diary whether or not they smoked and whether they drank alcohol (coded as 0 for no and 1 for yes). Exercise was the response to the question: how many total minutes of non-work related exercise did you do today? (walking, running, biking, swimming, aerobics, sports, work out, gardening, yard work). In addition, height and weight were reported annually from which the BMI was calculated (wtkg/htm2)

Stress-related factors.

Stress-related factors included perceived stress, anxiety, and urinary cortisol. Perceived stress was assessed in the diary with a question “how stressful was your day?” that women rated from 1 (not at all) to 6 (extremely, a lot). Brantley, Waggoner, Jones, & Rappaport33 found that a global stress rating and the sum of stress ratings across multiple dimensions correlated significantly (r=.35, p<.01). Anxiety was assessed by asking women to rate how anxious they felt that day on a scale where 0 was absent and 4 was extreme.

Urinary Cortisol levels were determined by radioimmunoassay using Coat-A-Count Cortisol Kit (Siemens Medical Solutions, Los Angeles, CA)and is described in detail elsewhere.34 Coat-A-Count Cortisol is designed for the quantitative measurement of unbound cortisol (hydrocortisone, Compound F) in serum, urine, and heparinized plasma. The assay is highly specific for cortisol and has extremely low cross-reactivity with other steroids, except for prednisolone.

Analyses

Initially, patterns of hot flash severity were examined with frequency distributions and bar graphs to describe changes in hot flash severity across age in 5 year increments from age 35 to age 55, by MT stages, and by number of years before or after FMP. Second, to ascertain if the data from this study were consistent with other longitudinal studies with respect to hormonal covariates of hot flashes, univariate mixed effects modeling using the R library35–39 was used to describe individual effects of urinary estrone and FSH on hot flash severity. Third, to find out which covariates in the conceptual model (Figure 1) had a significant effect when examined individually, univariate mixed effects modeling was used. Finally, to test a multivariate model to determine which predictors had a significant effect on hot flash severity over time, those individual variables from the univariate analyses with a significance of p ≤0.1 were entered together in a multivariate mixed effects model.

Before testing the conceptual model, an initial series of statistical models tested age alone as a predictor of hot flash severity to learn whether a random intercept, fixed slope model or a random intercept, random slope model was the best fit. It was first postulated that overall levels of HF severity would differ from woman to woman (random intercept), but the scores would change with age in a common manner (fixed slope). The second statistical model extended the first to postulate that each woman had a different mean level of HF severity and rate of change (random intercept, random slope). The best fitting model (fixed slope or random slope) was determined by using the maximum likelihood estimation with Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).39 Using the best fitting model, individual covariates were added iteratively to test the effect on HF severity over time. Because these analyses were for explanation and to stimulate further mechanistic studies, a p value of 0.10 was used as the criterion of significance for the univariate model and 0.05 for the final model. Different numbers of women and observations occurred with each covariate tested because the analysis required pairing of observations of the outcome and predictor variables at each time point. In all analyses, age was centered at the group mean to enable the interpretation of the effect of age on hot flash severity.

Results

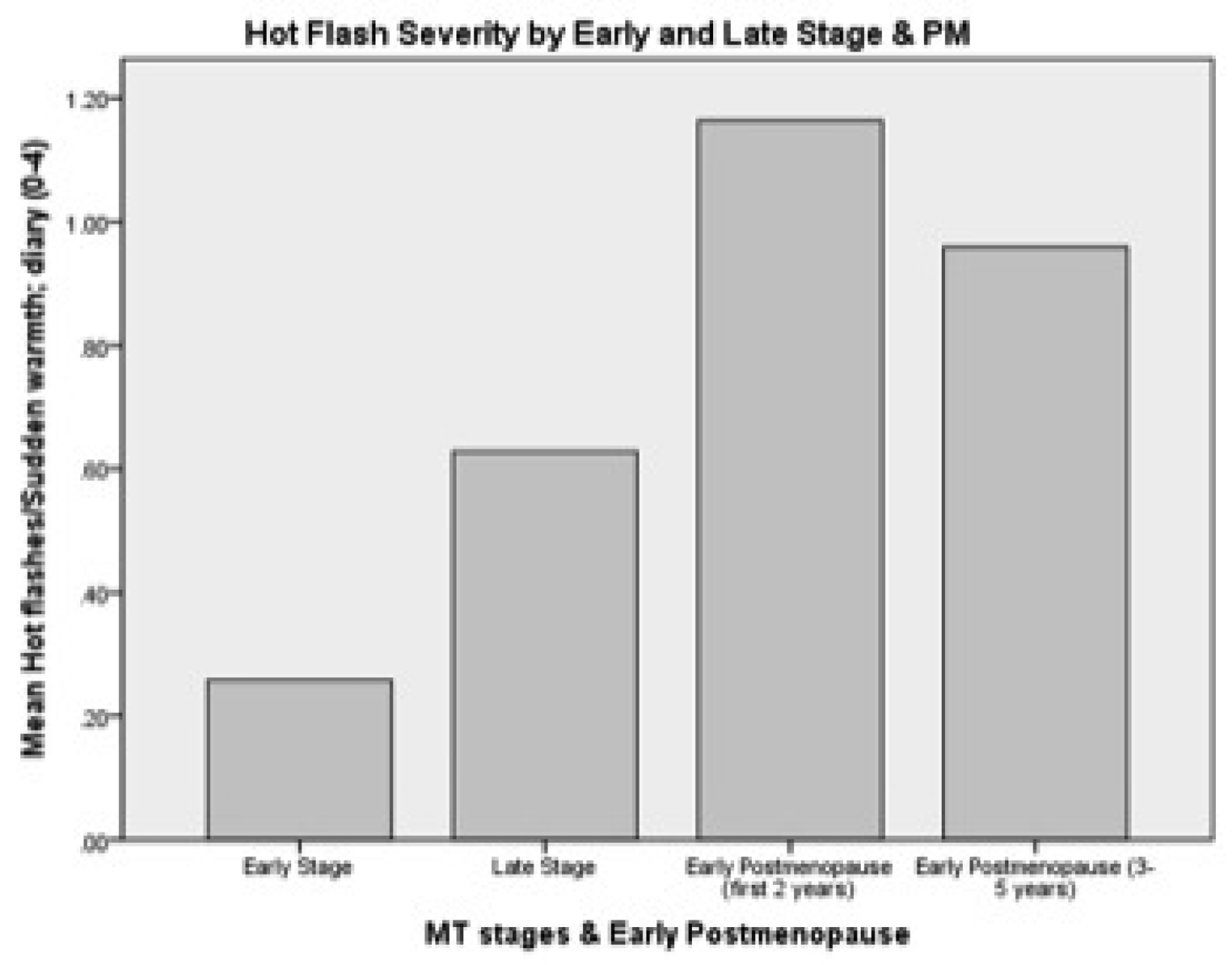

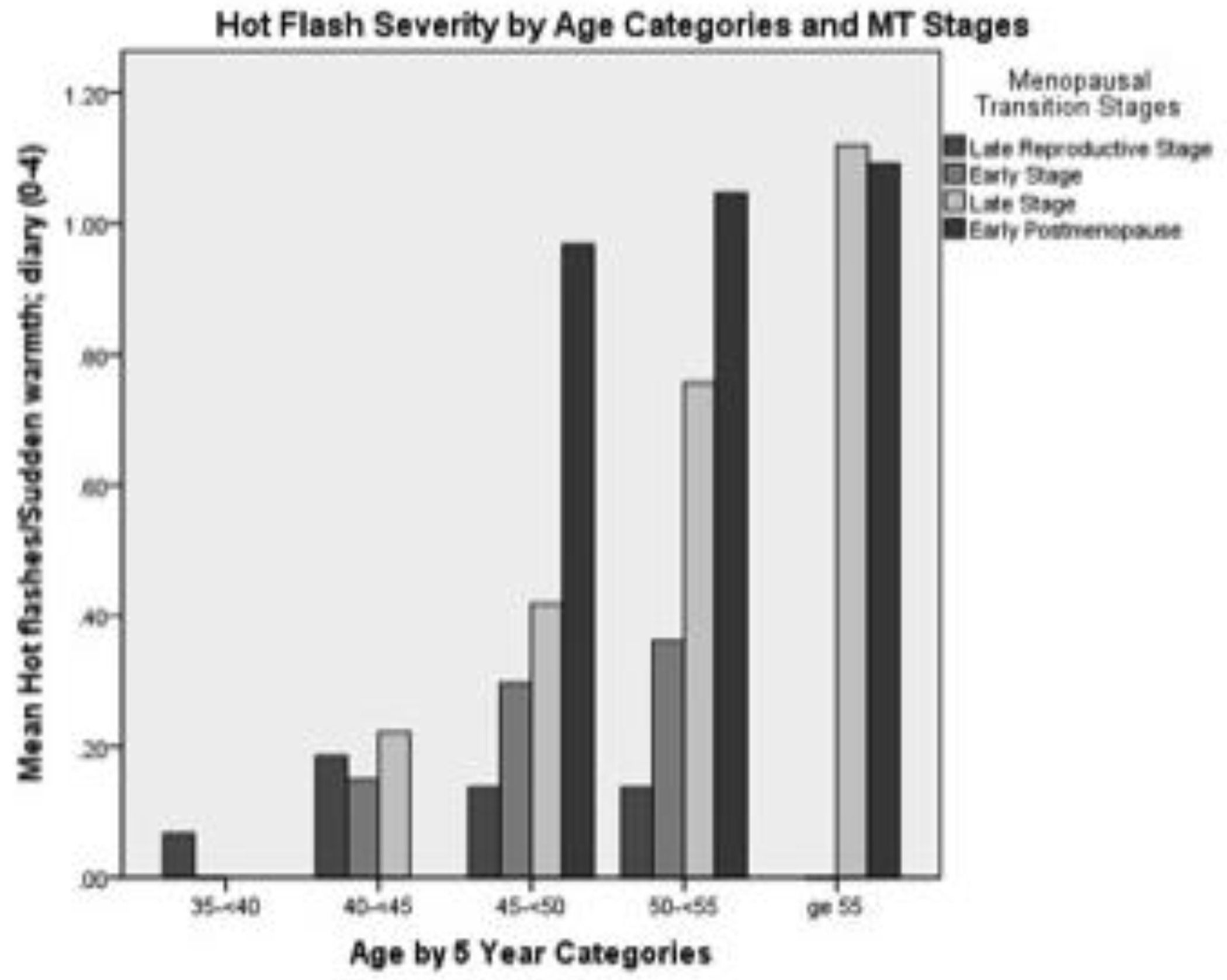

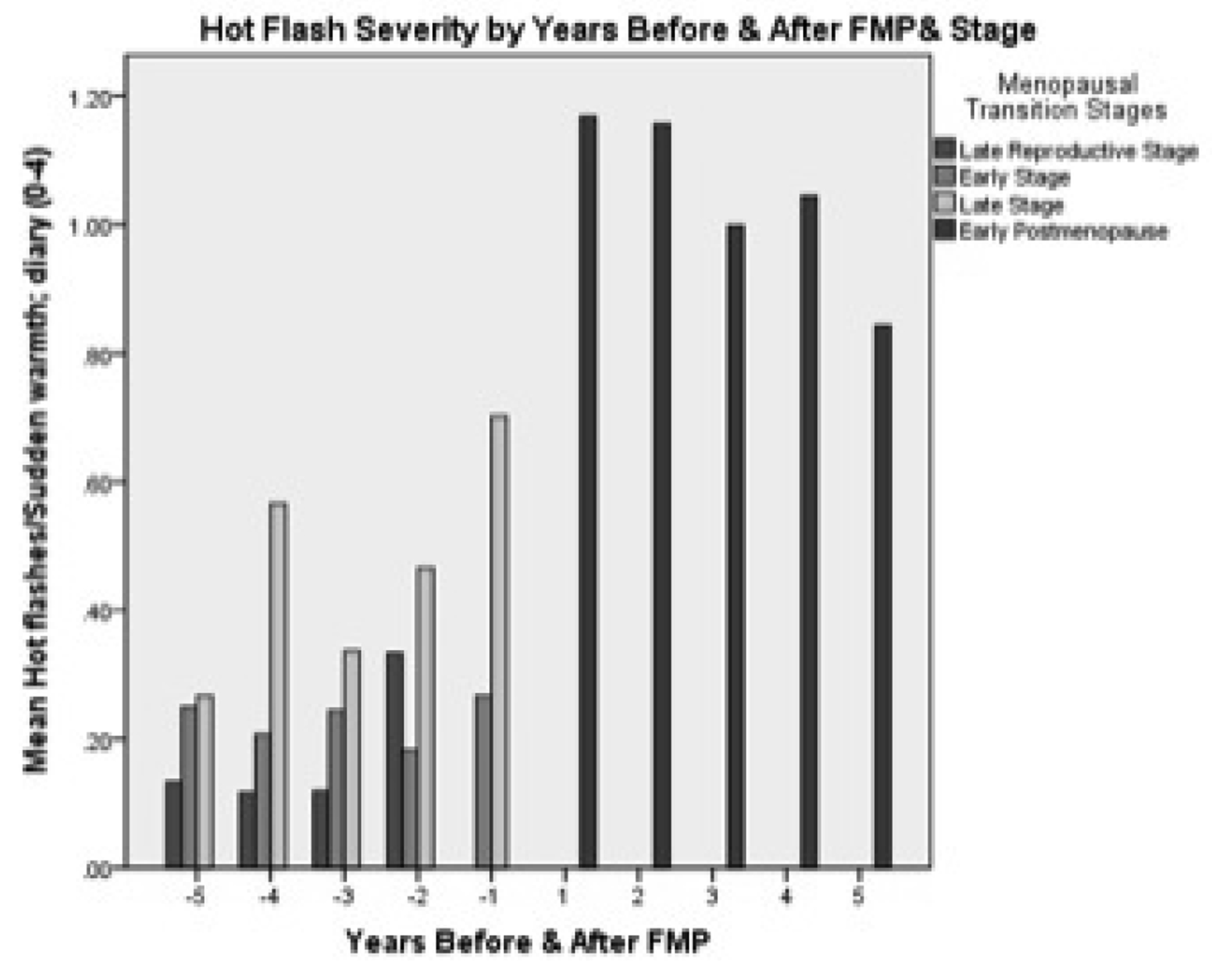

The first aim was to describe changes in hot flash severity with respect to age, stages of reproductive aging, estrone and FSH. Hot flash severity, as expected, increased from age 35 until age 60 (Table 2). This pattern of change was mirrored by increases in severity from the late reproductive stage up to two years PM (Table 2). A small decrease occurred from three to five years PM (Figure 2). When examining the influence of both age and reproductive aging together, hot flash severity increased visibly as women progressed through the early and late MT stage to early PM despite their age group (Figure 3). When number of years before and after FMP was examined, hot flash severity increased the most from two years before FMP to 1 year after FMP and began declining three years after FMP (Table 2). Severity was highest during late MT stage and for all 5 years after FMP (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Frequency Distributions for Hot Flash Severity by Age Categories, Menopausal Transition Stage & Years Before & After FMP

| Mean (SD) | N (observations) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age Category | ||

| 35-<40 | 0.06 (0.30) | 399 |

| 40-<45 | 0.17 (0.50) | 1775 |

| 45-<50 | 0.29 (0.63) | 2562 |

| 50-<55 | 0.72 (1.00) | 1590 |

| 55-<60 | 1.08 (1.03) | 552 |

| ≥ 60 | 1.00 (0.96) | 16 |

|

| ||

| MT stages | ||

| Late Reproductive | 0.15 (0.46) | 2661 |

| Early | 0.26 (0.59) | 2022 |

| Late | 0.63 (0.99) | 1009 |

| PM (1-2 years) | 1.16 (1.06) | 583 |

| PM (3-5 years) | 0.96 (1.00) | 619 |

|

| ||

| FMP intervals | ||

| −5 | 0.22 (0.52) | 323 |

| −4 | 0.25 (0.58) | 361 |

| −3 | 0.27 (0.66) | 342 |

| −2 | 0.41 (0.81) | 318 |

| −1 | 0.69 (1.06) | 318 |

| +1 | 1.17 (1.07) | 326 |

| +2 | 1.16 (1.04) | 257 |

| +3 | 1.00 (1.00) | 215 |

| +4 | 1.04 (1.03) | 187 |

| +5 | 0.84 (0.91) | 164 |

Figure 2.

Hot flush severity by early-and late-MT stages and early Postmenopause

Figure 3.

Hot flush severity by age categories and stages of menopausal transition (MT) and early postmenopause

Figure 4.

Hot flush severity by years before and after final menstrual period (FMP) and stage

The effects of the HPO axis on hot flashes is well established.2,13,14 To verify these findings within this database, a univariate mixed effects model was tested for hot flash severity that included age as a random effect and E1G levels in one model and age and FSH levels in another model. As seen in Table 3, with estrone as a covariate, age had a significant (p <.001) but small effect on hot flash severity (.08 increase in hot flashes for every year increase in age). At the same time a decrease in estrone had a significant effect on hot flash severity (−.35, p <.001). Thus, for every log unit decrease in estrone there was a 0.35 increase in hot flash severity. For FSH the results were similar but in the opposite direction. As FSH increased by one log unit, hot flash severity increased significantly (p<.001) by 0.13.

Table 3.

Random Effects Models for Hot flash Severity with Age as Predictor (β2) and with Estrone and FSH as Covariates (β3)

| Mean Values (p values) | Standard Deviations Number | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | β1* | β2* | β3* | σ1** | σ2** | σε** | Women | Observations |

| Estrone (log10) (1.2) | 0.37 (<.001) | 0.08 (<.001) | −0.35 (<.001) | 0.45 | 0.08 | 0.59 | 130 | 4827 |

| FSH (log10) (1.1) | 0.37 (<.001) | 0.07 (<.001) | 0.13 (<0.001) | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 130 | 4913 |

β1, β2, β3 are the fixed effects (group averages) for the intercept, slope and covariate, respectively.

σ1, σ2, σε are the random effects (variability) for the intercept, slope and residual error, respectively.

Aim 2 was to test a conceptual model of hot flash severity with a multilevel mixed effects model with respect to age, MT related factors, health-related factors and stress-related factors (Figure 1). Estrone and FSH were omitted from this model because their strong effect masks other potential effects. Age and each covariate in the conceptual model were first tested individually using a random intercept, random slope model to determine which covariates had a significant effect on hot flash severity. As seen in Table 4, age had a significant effect (p <.001) on hot flash severity when entered with each covariate except MT stage. Other significant covariates were being in the late MT stage (p <.001) or early PM (p <.001), having a higher BMI (p=.09), being younger at onset of late stage (p=.03), having lower urinary cortisol (p=.01) and greater anxiety (p=.03).

Table 4.

Random Effects Models for Hot flash Severity with Age as Predictor (β2) and with Individual Covariates (β3)

| Mean Values (p values) | Standard Deviations Number | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Predictor | β1* | β2* | β3* | σ1** | σ2** | σε** | Women | Observations |

|

| ||||||||

| Age (47.6) | 0.36 | 0.05 (<.001) | - | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 291 | 6973 |

|

| ||||||||

| Health-related factors | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| BMI (26.0) | 0.36 (<.001) | 0.05 (<.001) | 0.06 (.08) | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 291 | 6973 |

|

| ||||||||

| If smokes | 0.36 (<.001) | 0.05 (<.001) | 0.05 (0.34) | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 291 | 6973 |

|

| ||||||||

| If drinks alcohol | 0.39 (<.001) | 0.05 (<.001) | −0.03 (0.39) | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 291 | 6973 |

|

| ||||||||

| Amount of exercise | 0.36 (<.001) | 0.05 (<.001) | 0.0002 (0.32) | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 291 | 6973 |

|

| ||||||||

| Menopausal Transition Factors | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| MT-stage | 0.19 (<.001) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.58 | 291 | 6973 | |

| Early | 0.02 (0.40) | |||||||

| Late | 0.41 (<.001) | |||||||

| Early PM | 0.84 (<.001) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Age onset Late Stage | 1.92 (0.005) | 0.06 (<0.001) | −0.03 (0.03) | 0.40 | 0.05 | 0.63 | 127 | 4922 |

|

| ||||||||

| Age onset FMP | 0.81 (0.26) | 0.07 (<.001) | −0.008 (0.55) | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 110 | 4516 |

|

| ||||||||

| Stress factors | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Perceived Stress | 0.35 (<.001) | 0.05 (<.001) | 0.005 (0.53) | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 291 | 6973 |

|

| ||||||||

| Cortisol (1.5) | 0.36 (<.001) | 0.08 (<.001) | −0.06 (0.01) | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 130 | 4891 |

|

| ||||||||

| Anxiety | 0.35 (<.001) | 0.05 (<.001) | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 291 | 6973 |

β1, β2, β3 are the fixed effects (group averages) for the intercept, slope and covariate.

σ1, σ2, σε are the random effects (variability) for the intercept, slope and residual error.

Those covariates with a significant effect on hot flash severity at p 0.10 level when tested individually were then included together into a final multivariate mixed effects model. The covariates included age, the MT-related factors stage and age of onset of late stage; the health-related factor BMI; and the stress factors cortisol and anxiety. (See Table 5). With multiple covariates in the model including stage, age no longer had a significant effect on hot flash severity (p = .74). Being in late stage or early PM had a significant effect (p <.001 for both) with hot flash severity increasing by .36 when in late stage compared to hot flash severity when in late reproductive stage. Being in early PM showed an even greater increase in hot flash severity, .92 compared to late reproductive stage. In this final model only anxiety and stage (late and early PM) had significant effects (p = .05) on hot flash severity with a small .03 increase in hot flash severity for every unit increase in anxiety.

Table 5.

Final Random Effects Model for Hot Flash Severity with Age as Predictor and Significant Covariates Simultaneously Entered (N = 81; observations = 3642)

| Beta Coefficient | Standard Error/Standard Deviation | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Fixed effects | |||

| β1 intercept | −0.70 | 1.15 | 0.54 |

| β2 Age (−47.6) years | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.74 |

| β3 Menopausal Transition Stage | |||

| Early Stage | 0.01 | 0.05 | .76 |

| Late Stage | 0.36 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Early PM | 0.92 | 0.09 | <.001 |

| B4 Age onset Late Stage | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.43 |

| B5 BMI (26) | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.36 |

| B6 Log Cortisol (1.5) | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.14 |

| B7 Anxiety | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

|

| |||

| Random effects | |||

| b1 Intercept σ1 | 0.45 | ||

| b2 Age (−47.6) years σ2 | 0.08 | ||

| bε residual σε | 0.61 | ||

Discussion

Severity of hot flashes in the SMWHS population increased with women’s age across the spectrum from age 35 to 60 years. In addition hot flash severity was associated with having lower estrone and higher FSH levels and being in the late MT stage or early PM. Hot flash severity increased most from 2 years before FMP to 1 year after FMP, declining 3 years after FMP, and was highest during the late stage and all 5 years before FMP. These results are consistent with earlier analyses of the effects of estrogen and FSH on hot flash severity in both the SWAN14 and Penn Ovarian Aging Studies.17 They are also consistent with the relationship between MT stages and PM as described by Freeman and colleagues.17,40 Of interest is the declining severity of hot flashes seen in the SMWHS cohort after 2 years following the FMP. This finding suggests that as the PM progresses, the severity of hot flashes diminishes. This needs to be replicated in other cohorts of women studied during the early PM.

Given the recent attention to the judicious use of hormonal therapy, with recommendations of limitation to the lowest dose for the shortest duration, investigators have focused specifically on the duration of and persistence of hot flashes after the FMP.40,41 Freeman determined that the median duration of hot flashes was 10.2 years for the Penn Ovarian Aging cohort40 and Col found that the duration was an average of 5 years in the MMWHS.41 Results of similar analyses for the SWAN study have not yet been published but promise to reveal ethnic/racial differences in the persistence of hot flashes after the FMP. Nonetheless, there is good reason to believe that hot flashes extend beyond the early PM, defined by the STRAW criteria as five years after the FMP.24 Understanding the severity of hot flashes during this period of reproductive aging and the factors that account for the associated distress women feel is a worthy research goal.

Our finding that women with greater anxiety experience more severe hot flashes is consistent with Freeman’s early description of the relationship of anxiety to hot flash severity.17 Moreover, anxiety preceded the development of hot flashes and its effect persisted after adjustment for estradiol levels as well as MT stage and other covariates. Indeed, effects of anxiety exceeded those of depressive symptoms. This relationship is also confirmed in studies by Hunter and colleagues, supporting their model in which symptom perception of thermal stimuli is influenced by anxiety, as well as stress, depressed mood, and somatic amplification of symptoms. 42

In addition to these findings, individual analysis showed relationships between hot flash severity and BMI, cortisol, and younger age at the onset of the late MT stage that warrant further exploration. The relationship of BMI to bothersome hot flashes has been well established, especially in the work of Thurston.16,43 In these analyses of individual effects of BMI on hot flash severity, women who had a higher BMI also had more severe hot flashes. When BMI was included in a model with MT stages, cortisol and anxiety, BMI was no longer significant.

In analyses of individual covariates with age, women who were younger at the onset of the late stage of the MT had more severe hot flashes. These results mirror effects of age on hot flash severity as reported by Freeman. 2 In addition, these effects may be related to the consequence of women experiencing accelerated reproductive aging. Bleil and colleagues hypothesized that women who experience more severe psychological stress attributable to environmental adversity would experience an increased volume of growing antral follicles at the cost of depleting their ovarian reserve over time.44 In a community-based sample of premenopausal women 25-45 years of age, Bleil and her colleagues found that antral follicle counts were higher among women reporting more psychological stress and that the associations were present in the younger women (25-35), but not in older women (40 and 45 years). Thus fertility may be potentiated by greater stress exposure resulting in increased reproductive readiness at younger ages and potentially earlier depletion of follicles and earlier menopause. Women experiencing the onset of the late stage of the MT at a younger age may have had higher stress exposure during their earlier reproductive aging stages with the consequence of earlier progression through the MT. Thus a consequence of the lifespan exposure to adversity and experience of stress may alter the course of reproductive aging and may help account for the effects of early experience of the late MT stage on hot flash severity. When age of onset of late stage was included in the model with MT stage, BMI, cortisol and anxiety, the effects of stress were not significant.

In addition, in the univariate analyses only a minor negative effect of cortisol on hot flash severity was found such that women with lower cortisol levels experienced more severe hot flashes. This effect is consistent with studies of chronic stress but also may be attributable to the influence of estrogens on basal cortisol levels such that women with lower estrone levels also had lower cortisol levels in our prior analyses.34 When we included cortisol in the same model of hot flash severity with other covariates, the effect of cortisol was not significant.

Limitations of this study include the need for replication of the findings in a larger and more diverse population, such as the SWAN cohort. In addition, specification of a causal model that includes indirect effects as consistent with those we propose above will be important to elaborate the relationships among age, late MT stage, PM, anxiety and hot flash severity.

Conclusions

Severity of hot flashes persisted through the MT stages and peaked during the late MT stage, diminishing after the second year PM. Women who experienced the greatest hot flash severity were those who were in the late MT stage or early PM and had higher levels of anxiety. In individual analyses, lower estrone and higher FSH levels were significantly related to hot flash severity as were higher BMI, lower cortisol, and younger age at inception of the late MT stage. Women who experience the most severe hot flashes are likely to have higher levels of anxiety, greater body mass, and may have experienced accelerated reproductive aging related to adverse experiences over the lifespan.

Funding Sources:

NINR R01-NR 04141; NINR P30 NR 04001

Contributor Information

Ellen Sullivan Mitchell, Department of Family and Child Nursing, University of Washington.

Nancy Fugate Woods, Department of Biobehavioral Nursing, University of Washington.

References

- 1.Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Guthrie JR, Burger HG. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia ER, Pien GW, Nelson DB, Sheng L Symptoms associated with menopausal transition and reproductive hormones in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:230–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gold EB, Block G, Crawford S, Lachance L, FitzGerald G, Miracle H, Sherman S. Lifestyle and demographic factors in relation to vasomotor symptoms: baseline results from the study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:1189–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams RE, Kalilani L, DiBenedetti DB, Zhous X, Granger AL, Fehnel SE, Levine KB, Jordan J, Clark RV. Frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms among peri- and postmenopausal women in the United States. Climacteric 2008;11:32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, Sternfeld B, Cohen LS, Joffe H, Carpenter JS, Anderson GL, Larson JC, Ensrud KE, Reed SD, Newton KM, Sherman S, Sammel MD, LaCroix AZ. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2011;305:267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newton KM, Carpenter JS, Guthrie KA, Anderson GL, Caan B, Cohen LS, Ensrud KE, Freeman EW, Joffe H, Sternfeld B, Reed SD, Sherman S, Sammel MD, Kroenke K, Larson JC, LaCroix AZ.. Methods for the design of vasomotor symptom trials: the Menopausal Strategies: Finding Lasting Answers to Symptoms and Health network. Menopause 2014;21:45–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed SD, Guthrie KA, Newton KM, Anderson GL, Booth-LaForce C, Caan B, Carpenter JS, Cohen LS, Dunn AL, Ensrud KE, Freeman EW, Hunt JR, Joffe H, Larson JC, Learman LA, Rothenberg R, Seguin RA, Sherman KJ, Sternfeld BS, LaCroix AZ. Menopausal quality of life: a RCT of yoga, exercise, and omega-3 supplements. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:244.e1–244.e11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guthrie JR, Dennerstein LR, Taffe JR, Lehert P, Brger HG. The menopausal transiton: a 9-year prospective population-based study. The Melbourne women’s Midlife Health Project. Climacteric 2004;7:375–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter JS. The hot flash related daily interference scale: A tool for assessing the impact of hot flashes on quality of life following breast cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2001;22:979–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams RE, Kalilani LK, DiBenedetti DB, Zhou X, Fehnel SE, Clark RV. Healthcare seeking and treatment for menopausal symptoms in the United States. Maturitas 2007;58:348–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voda AM. Climacteric hot flash. Maturitas 1981;3:73–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woods NF and Mitchell ES. Symptom Interference with work and relationships during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause 2011;18:654–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guthrie JR, Dennerstein L, Taffe JR, Lehert P, Burger HG. Hot flushes during the menopause transition: a longitudinal study in Australian-born women. Menopause 2005;12:460–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randolph JF Jr., Sowers M, Bondarenko I, Gold EB, Greendale GA, Bromberger JT, Brockwell SE, Matthews KA. The relationship of longitudinal change in reproductive hormones and vasomotor symptoms during the menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:6106–6112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thurston RC, Bromberger JT, Joffe H, Avis NE, Hess R, Crandall CJ, Chang Y, Green R, Matthews KA. Beyond frequency: who is most bothered by vasomotor symptoms? Menopause. 2008. Sep-Oct;15:841–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thurston RC, Sowers MR, Chang Y, Sternfeld B, Gold EB, Johnston JM, Matthews KA. Adiposity and reporting of vasomotor symptoms among midlife women: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2008. Jan 1;167:78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR, Kapoor S, Ferdousi T. The role of anxiety and hormonal changes in menopausal hot flashes. Menopause 2005;12:258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cagnacci A, Cannoletta M, Caretto S, Zanin R, Xholli A, Volpe A Increased cortisol level: a possible link between climacteric symptoms and cardiovascular risk factors. Menopause 2011;18:273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell ES, Woods NF. Cognitive symptoms during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause. Climacteric 2011;14:252–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell ES, Woods NF, Mariella A. Three stages of the menopausal transition from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study: toward a more precise definition. Menopause 2000;7:334–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harlow SD, Cain K, Crawford S, Dennerstein L, Little R, Mitchell ES, Nan B, Randolph JF Jr., Taffe J, Yosef M. Evaluation of four proposed bleeding criteria for the onset of late menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:3432–3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harlow SD, Mitchell ES, Crawford S, Nan B, Little R, Taffe J, ReSTAGE Collaboration. The ReSTAGE Collaboration: defining optimal bleeding criteria for onset of early menopausal transition. Fertil Steril 2008;89:129–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harlow SD, Crawford S, Dennerstein L, Burger HG, Mitchell ES, Sowers MF, ReSTAGE Collaboration. Recommendations from a multi-study evaluation of proposed criteria for staging reproductive aging. Climacteric 2007;10:112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, Rebar R, Santoro N, Utian W, Woods NF. Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW). Fertil Steril 2001;76:874–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taussky HH. A microcolorimetric determination of creatinine in urine by the Jaffe reaction. J Biol Chem 1954;208:853–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denari JH, Farinati Z, Casas PR, Oliva A. Determination of ovarian function using first morning urine steroid assays. Obstet Gynecol 1981;58:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanczyk FZ, Miyakawa I, Goebelsmann U. Direct radioimmunoassay of urinary estrogen and pregnanediol glucuronides during the menstrual cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1980;137:443–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Connor KA, Brindle E, Holman DJ, Klein NA, Soules MR, Campbell KL, Kohen F, Munro CJ, Shofer JB, Lasley BL, Woods JW. Urinary estrone conjugate and pregnanediol 3-glucuronide enzyme immunoassays for population research. Clin Chem 2003;49:1139–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker TE, Jennison KIM, Kellie AE. The direct radioimmunoassay of oestrogen glucuronides in human female urine. Biochem J 1979;177:729–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrell RJ, O’Connor KA, Holman DJ. Monitoring the transition to menopause in a five year prospective study: aggregate and individual changes in steroid hormones and menstrual cycle lengths with age. Menopause 2005;12:567–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Connor KA, Brindle E, Shofer JB, Miller RC, Klein NA, Soules MR, Campbell KL, Mar C, Handcock MS. Statistical correction for non-parallelism in a urinary enzyme immunoassay. J Immunoassay Immunochem 2004;25:259–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qui Q, Overstreet JW, Todd H, Nakajima ST, Steward DR, and Lasley BL. Total urinary follicle stimulating hormone as a biomarker for detection of early pregnancy and peri implantation spontaneous abortion. Environmental Health Perspectives 1997:105:862–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brantley PJ, Waggoner CD, Jones GN, Rappaport NB. A Daily Stress Inventory: development, reliability, and validity. J Behav Med 1987;10:61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woods NF, Smith-DiJulio K, Percival DB, Mitchell ES. Cortisol Levels across the menopausal transition: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause 2009;16:708–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models, R package version 3.1 2005:1–66. [Google Scholar]

- 36.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2005. http://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarkar D Lattice: Lattice Graphics. R package version 0.12–11. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinheiro J, Bates D. Mixed-effects models in S and S-PLUS. NY: Springer, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hox J Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Liu Z, Gracia CR. Duration of menopausal hot flushes and associated risk factors. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2011;117:1095–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Col NF, Guthrie JR, Politti M, Dennerstein L Duration of vasomotor symptoms in middle-aged women: a longitudinal study. Menopause 2009;16:453–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunter MS and Chilcot J. Testing a cognitive model of menopausal hot flushes and night sweats. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2013;74:307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thurston RC, Sowers MR, Sternfeld B, Gold EB, Bromberger J, Chang Y, Joffe H, Crandall CJ, Waetjen LE, Matthews KA. Gains in body fat and vasomotor symptom reporting over the menopausal transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. J Epidemiol. 2009. Sep 15;170:766–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bleil ME, Adler NE, Pasch LA, Sternfeld B, Gregorich SE, Rosen MP, Cedars MI. Psychological stress and reproductive aging among pre-menopausal women. Human Reproduction 2012;27:2720–2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]