Abstract

This meta-analysis aimed to determine the prevalence, symptoms, and outcomes of COVID-19 in the elderly with Parkinson’s disease (PD) by searching in the international databases of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Sciences, and EMBASE using the keywords of “COVID-19” and “Parkinson’s.” All articles related to Parkinson's disease and COVID-19 from January 2019 to October 20, 2021 were reviewed. The STATA software was used for analysis. A total of 20 articles were selected for data extraction in this meta-analysis, of which ten were cross-sectional studies (to determine the prevalence), five case–control studies, and five cohort studies (to examine the association). The results of the meta-analysis showed the prevalence of COVID-19 in patients with PD was 1.06% (95% CI 1.03–1.1%; P = 0.02), and the prevalence of their hospitalization due to COVID-19 was 0.98% (95% CI: 0.95–1.02%; P = 0.00). Also, the prevalence of depression and anxiety during the pandemic in this group was 46% (95% CI 29–64%; P = 0.00) and 43% (95% CI: 24–63%; P = 0.00), respectively. The prevalence of tremor and sleep problems were higher than those of other symptoms in the studied population. According to the results, there was no significant difference in the risk of COVID-19 infection between Parkinson's patients and healthy people. In other words, the risk of COVID-19 infection was equal in both groups (RR = 1.00 (CI 95% 0.77–1.30%; P = 0.15)). The results showed mortality and hospitalization rates of the elderly with Parkinson's disease were not significantly different from those of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and mental disorders increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. So, designing and developing more specific studies, like cohort studies, with large sample size is required for assessing these associations.

Keywords: COVID-19, Parkinson’s disease, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

COVID-19 spread in most countries so rapidly that the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [1–4]. The pandemic has had a profound effect on all human life aspects, including people’s physical and mental health around the world [5, 6]. The risk of COVID-19 and its mortality is higher among vulnerable populations, such as the elderly with chronic diseases, especially neurological ones [7]. However, the pandemic and the subsequent emergency situation forced officials to focus on controlling and adhering to the care associated with this virus while ignoring the priority of caring for those with chronic and neurological diseases [8]. On the other hand, the outcomes of this disease increased in older people living with neurological diseases, one of the most prominent of which is Parkinson's disease [6]. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most common neurological diseases prevalent in the elderly. In addition to motor symptoms, such as bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor caused by degeneration and the destruction of dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurons, non-motor symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders, to advanced stages are also common in the early [8, 9]. Therefore, changes and social conditions during the pandemic may have affected the motor and non-motor symptoms experienced by PD patients and negatively affected their life quality [6, 9, 10]. To date, few clinical studies have been performed on patients with PD, infected by COVID-19 [4]. Therefore, there is currently insufficient evidence to suggest PD itself increases the risk of COVID-19 or COVID-19 exacerbates PD symptoms. Contradictory results have been reported from studies with small sample sizes of PD patients with COVID-19 [2].

However, studies have shown the COVID-19 pandemic has directly and indirectly affected patients with PD worldwide in various ways [6, 11]. First, although the risk of developing PD does not increase in the general population [3], individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 are more likely to have worsening symptoms [12]. It is not yet clear whether patients with Parkinson's and those receiving advanced treatment are likely to be at greater risk of COVID-19 death [13]. Second, the conditions of caring for PD patients have changed [14]: surgical treatments have been delayed [15], and access to outpatient clinics has been limited to prevent the spread of COVID-19 [16]. Regular physical evaluation and adjustment of medications in non-emergency situations have also become more difficult. Third, the social, economic, and medical outcomes have led to profound lifestyle changes in patients with PD, including decreased overall physical activities, inability to attend exercise classes, and increased levels of mental distress.

In PD, these lifestyle changes are referred to the "hidden sorrows" of COVID-19 [17] because they may indirectly worsen symptoms. Physical activities help reduce PD motor symptoms [18]. Also, staying at home is especially psychologically harmful to this population. Mental distress worsens a variety of motor symptoms and also causes or exacerbates neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety and depression [6].

The study aimed to systematically review and meta-analyze the status of patients with PD during the COVID-19 pandemic. The first goal of this meta-analysis was to determine the prevalence of COVID-19 in patients with Parkinson's disease. Subsequently, the occurrence of symptoms and outcomes associated with COVID-19 was determined in these patients. Finally, the effect of COVID-19 and its conditions was determined on the symptoms of PD, like physical activities, sleep complications, and mental disorders.

Methods

The study protocol has previously been registered in PROSPERO with the code CRD42021282398. The present study was a systematic review and meta-analysis designed and conducted with the PECOT structure. P means the study population, patients with Parkinson’s disease, E means exposure to COVID-19, C means the comparison group, including all people with Parkinson's who did not have COVID-19, and O means the study outcome, the prevalence of COVID-19, depression and anxiety, physical activities, Parkinson’s symptoms, and sleep disorders in patients with Parkinson’s disease during the pandemic. This meta-analysis is the most comprehensive one associated with COVID-19 in patients with Parkinson’s disease, which has considered all possible outcomes reported in the early studies.

Search strategy and screening

All articles published in international databases were searched to extract studies which examined PD during the COVID-19 pandemic. The search was conducted in these databases without any language or time restrictions. Search strategies included the following keywords: “COVID 19,” “COVID-19 Virus Disease,” “2019-nCoV Infections,” “2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease,” “Coronavirus Disease 2019,” SARS Coronavirus 2 Infection,” “SARS-CoV-2 Infection,” “SARS-CoV-2 Infections,” “COVID-19 Virus,” “Wuhan Coronavirus,” “SARS Coronavirus 2,” “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2,” “Parkinson,” “Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease,” “Lewy Body Parkinson’s Disease,” “Parkinson’s Disease,” “Primary Parkinsonism,” and “Secondary Parkinson’s Disease,” all of which have been compiled from Mesh. The search databases included (Medline) PubMed, Scopus, Web of Sciences, and EMBASE, and its timeline was from January 2019 to October 20, 2021. The duplicate studies were removed using the title of the published articles, their authors, and year of publication using Endnote software, version 9. Then, the remaining articles were reviewed and evaluated based on their titles, abstracts, and full texts considering the inclusion criteria. Two study authors independently (MA, PM) screened articles based on their titles, abstracts, and full texts, and disagreements were resolved by a third one (YM). After screening, the final selection of articles was made by evaluating the full text of the selected ones.

Study selection

The search strategy in international databases was independently performed by the two researchers (MA and PM), and the disagreements were resolved by the third person (YM).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of COVID-19 infection and its symptoms in elderly patients with PD and the association between PD and COVID-19. Therefore, both descriptive observational studies (cross-sectional ones) and analytical observational studies (case or cohort ones) were examined. The prevalence of PD symptoms and those of COVID-19 in Parkinson's patients should have been reported in these studies. Review studies, case reports, case series, clinical trials, other interventional studies, and letters to the editor were excluded from the present research (Table 1).

Table 1.

The eligibility criteria

| Eligibility criteria | |

|---|---|

| Association | Prevalence |

|

The study population was patients with Parkinson’s disease (with Covid-19 or not) The exposure in these studies was Covid-19 The comparison group included people with Parkinson's who did not have Covid-19 The intended outcomes were the risk of complications associated with Covid-19 and its symptoms (Covid-19, hospitalization, and death and symptoms, including fever, cough, respiratory difficulties, diarrhea, smell reduction, taste reduction, muscle pain/ joint pain, nausea/vomiting, and fatigue) |

The study population was patients with Parkinson’s disease (with Covid-19 or not) The intended outcomes in studies were evaluation of the Parkinson's symptoms such as tremor, physical activity, sleep disorders, and mental disorders The intended type of studies was analytical or descriptive cross sectional |

Data extraction

After three stages of evaluation based on the title, abstract, and full text, the selected articles were retrieved for detailed analysis. The data were collected using a checklist containing the authors’ names, country, publication year, study type, study population, sample size, data source, duration of Parkinson’s disease, age, number of patients with COVID-19, rates of hospitalization and mortality due to COVID-19, evaluation of depression and anxiety, physical activities, COVID-19 symptoms (fever, cough, weakness, respiratory problems and shortness of breath, dysuria, decreased sense of smell, decreased sense of taste, fatigue, headache, myalgia, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting), and PD symptoms (tremor, dyskinesia, bradykinesia, rigidity, gait, freezing of gait, balance problems, cognitive impairment, sleep problems, and daytime sleepiness) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants and mental disorders

| Authors (Years) (R) Country |

Type of study | Study population | Sample size | Data sources | Age (male) | Duration of Disease | Number of COVID-19 | Admission to hospital (COVID-19) | Mortality (COVID-19) | Mortality Causes (EF; 95% CI) | Depression (COVID-19) | Anxiety (COVID-19) | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Birgul Balci (2021) [23] Turkish |

Case control |

PD Non-PD |

Patients = 45 Healthy = 43 |

Questionnaire screening |

Patients = 67(66%) Healthy = 66(55.8%) |

8 years | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7 |

|

Elisa Montanaro (2021) [24] Italy |

Case control |

PD Non-PD |

All Patients = 100 Caregivers = 60 |

Electronic database of the movement disorder Center of the University Hospital of Turin |

All patients = 62.4 ± 9.0 (38–78) Male = 60 Caregivers = 62.1 ± 9.2 (43–83) Male = 21 |

All Patients = 13.4 ± 4.6 (6–31) | Execution of nasopharyngeal swab (from February 2020 to T0) n = 1 Diagnosis of COVID-19 (from February 2020 to T0) n = 1 | NR | NR | NR |

T = 0 All patients = 35% T = 1 All patients = 34.1% |

T = 0 All patients = 39% T = 1 All patients = 30.6% |

7 |

|

Luca Vignatelli (2020) [7] Italy |

Historical cohort design |

PD Non-PD |

Parkinson’s disease = 696 Parkinsonism = 184 Control cohort = 8590 |

Italian health system |

Control cohort = 76 (58.2) Parkinson’s disease = 75 (58.8) Parkinsonism = 80.5 (57.1) |

– |

PD: 4 (3 men) PS = 6 (3 men) control cohort = 64 (44 men) |

Number of hospital admission for COVID-19 Control cohort = 64 Parkinson’s disease = 4 Parkinsonism = 6 |

N = 29 PD = 1 PS = 3 control cohort = 25 |

NR | NR | NR | 8 |

|

Maria Buccafusca (2020) [25] Italy |

Cohort | Patients with COVID and Parkinson's |

Patients with COVID and Parkinson's = 12 |

Hospital | 73 (50%) | 22 years |

12 (100%) |

Days of hospitalization – average = 30.7 |

0 | NR | NR | NR | 6 |

|

Raphael Scherbaum (2020) [11] Germany |

Cross-sectional study |

PD non-PD |

5,210,432 numbers PD = 65,127 Non-PD = 5,176,177 |

Hospital | NR | NR |

30,872 Non-PD = 30,179 PD = 693 |

30,872 Non-PD = 30,179 PD = 693 |

Non-PD = 6241 20.7% PD = 245 35.4% |

NR | NR | NR | 7 |

|

Mehri Salari (2020) [19] Iran |

Cross-sectional, case–control survey | Parkinson’s disease (PD) and non-PD |

500 PD = 137 Caregivers = 95 Control = 442 |

NR |

PD = 55 (34.3) Control = 43 (25.3) |

< 5 32.8 5–10 35.8 > 10 31.4 |

PD = 1.5% Control = 4.5 |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

PD % No anxiety = 18.2 Mild = 26.3 Moderate = 29.9 Severe = 25.5 CONTROL No anxiety = 56.3 Mild = 28.3 Moderate = 10.6 Severe = 4.8 |

7 |

|

Eleonora Del Prete (2020) [2] Italy |

Case-controlled survey | Parkinson’s disease (PD) |

21 PD COVID-19 = 7 PD non-COVID = 14 PD = 733 |

NR | 75 |

PD non-COVID = 8.93 PD COVID-19 = 9.29 |

PD COVID-19 = 7 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

PD = 183 25% |

8 |

|

Fukiko Kitani-Morii (2020) [8] Japan |

Cross-sectional study | PD patients and their family members |

71 39 PD patients and 32 controls |

NR |

< 70 = 25 (35.2) 70–79 = 33 (46.4) > 80 = 13 (18.3) |

< 5 = 22 (56.4) > 5 = 17 (43.5) |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

Total Normal = 32 (46.3) Mild = 20 (28.9) Moderate = 9 (13.0) Severe = 8 (11.5) PD Normal = 14 (36.8) Mild = 9 (23.6) Moderate = 8 (21.0) Severe = 7 (18.4) CONTROL Normal = 18 (58.0) Mild = 11 (0.35) Moderate = 1 (3.2) Severe = 1 (3.2) |

Total Normal = 35 (49.2) Mild = 20 (28.1) Moderate = 10 (14.0) Severe = 6 (8.4) PD Normal = 18 (46.1) Mild = 9 (23.0) Moderate = 7 (17.9) Severe = 5 (12.8) Control Normal = 17 (53.1) Mild = 11 (34.3) Moderate = 3 (9.3) Severe = 1 (3.1) |

8 |

|

Francesco Cavallieri (2020) [10] Italy |

Cross-sectional online survey |

PD Caregivers |

103 PD = 67 Caregivers = 36 |

online survey |

(Men = 61.17%) 41–50 = 3 51–60 = 16 61–70 = 54 71–80 = 22 > 80 = 8 |

< 2 = 11 2–5 = 28 > 5 = 64 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6 |

|

H El Otmani (2020) [26] Moroccan |

Prospectively cohort |

PD patients | 50 | via the Internet |

60.4 (48%) |

NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR |

At the beginning = 14 (28%) After 6 weeks = 17 (34%) Depression Improvement = 5 Worsening = 12 |

At the beginning = 16 (32%) After 6 weeks = 15 (30%) Anxiety Improvement = 4 Worsening = 8 |

8 |

|

Yun Xia (2020) [37] China |

A quantitative study Cross-sectional and |

PD patients healthy controls |

288 PD patients = 119 healthy control = 169 |

Questionnaire based interview investigation |

61.18 ± 8.77 years PD = (51.3%) male |

6.84 ± 4.60 years | NR | NR | NR | NR |

HADS-depression ≥ 8 PD = 27 Control = 27 |

HADS-anxiety ≥ 8 8 PD = 25 Control = 29 |

6 |

|

Anouk van der Heide (2020) [6] Netherlands |

Longitudinal observational cross-sectional study | PD patients |

PD = 498 Responders (n = 358) non-responders (n = 140) |

sent an online survey to the Personalized Parkinson Project (PPP) cohort |

Responders = 62.8 (61.5%) male Non-responders = 63.3 (55.7%) male |

Responders = 3.9 (1.8) Non-responders = 4.3 (2.0) |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

Worsened = 31.6% No change = 62.7% Improved = 5.8% |

NR | 9 |

|

Niraj Kumar (2020) [21] India |

Cross-sectional study | PD patients |

832 35.4% reported sleep disturbances = 295 New-onset/ worsening of sleep disturbances (NOWS) was reported by 23.9% subjects = 199 |

Questionnaire |

Nearly 84% patients were aged 50 years or older |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

New-onset/worsening of sleep disturbances (n = 199) = 56.3% Parkinson’s disease subjects who never had sleep disturbances (n = 537) = 35.7% |

New-onset/worsening of sleep disturbances (n = 199) = 60% Parkinson’s disease subjects who never had sleep disturbances (n = 537) = 39.1% |

8 |

|

Keisuke Suzuki (2020) [38] Japan |

Cross-sectional survey |

PD Caregivers |

200 PD = 100 Caregivers = 100 |

NR |

CG = 65.5 ± 12.0 PD = 72.2 ± 9.1 |

5.8 ± 4.4 YEARS |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

CG = 17 (17.0) PD = 20 (20.0) |

CG = 6 (6.0) PD = 6 (6.0) |

8 |

|

Heng Zhai (2020) [4] China |

Retrospective, cohort and observational study |

1-PD + COVID 2-COVID |

296 1–10 2–286 |

Hospital |

66 years (50.68%) |

NR | 296 |

ALL = 13.00 (7.00–18.75) PD + COVID = 12.00 (5.25–24.50) COVID + non-PD = 13.00 (7.00–18.00) |

ALL = 119 (40.20%) PD + COVID = 3(30.00%) COVID + Non-PD = 116 (40.56%) |

NR | NR | NR | 7 |

|

Joomee Song(2020) [27] e United Kingdom |

Cohort | PD patients | 100 | NR | 70 Male (54%) | 6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5 (5) | NR | 8 |

|

Ethan G Brown (2020) [22] USA |

Cross sectional |

PD non-PD |

PD = 5429 Non-PD = 1452 |

NR |

PD + COVID = 65(47) PD = 68(52) Non-PD + COVID = 57(8) Non-PD = 61(22) |

PD = 51 Non-PD = 26 |

PD = 5 (9.8%) Non-PD = 2 (7.7%) |

NR | NR | NR | NR | 8 | |

|

Cilia (2020) [12] Italy |

Case control |

PD + COVID PD |

PD + COVID = 12 PD = 36 |

NR |

PD + COVID = 65.5(41.7) PD = 66.3(41.7) |

Case = 6.3 Control = 6.1 |

Confirmed COVID-19 Case = 6 Control = 0 –– Suspect COVID-19 Case = 2 Control = 4 |

N (%) Case = 1 (8.3) |

0 | NR | NR | NR | 6 |

|

Fasano (2020) [3] Italy |

Case control |

PD + COVID Non-PD |

Case = 1381 Control = 1207 |

NR |

Case + COVID = 70.5(52.4) Case non-COVID = 73(57.2) |

Case + COVID = 9.9 Case non-COVID = 9.1 |

Case = 105 (32 confirmed and 73 probable cases) Control = 95 |

N (%) Case = 18(17.1) Control = 25(27.2) |

N (%) Case = 6(5.7) Control = 7(7.6) |

NR | NR | NR | 8 |

|

Diego Santos-Garcia (2020) [5] Spain |

Cross sectional |

PD + COVID PD |

568 PD + COVID = 15 PD = 553 |

NR |

63.5 (47) |

8.6 | 15 | NR | NR | NR |

PD + COVID = 57.1% PD = 65.6% Total = 65.4% |

PD + COVID = 60% PD = 65.5% Total = 65.6 |

6 |

Qualitative evaluation of articles

Two of the study authors (MA, MA) conducted a qualitative evaluation of the studies on the basis of the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) checklist. This checklist was designed to evaluate the quality of observational studies. This tool examines each research with six items in three groups of selecting study samples, comparing and analyzing study groups, and measuring and analyzing the desired outcome. Each of these items is given a score of one if observed in the studies, and the maximum score for each study is nine points. In case of disagreements in the score assigned to the published articles, the discussion method and a third researcher were used [19].

Statistical analysis

The Metaprop command was used to calculate the cumulative prevalence with a 95% confidence interval. First, the total sample volume was extracted from the initial studies. Then, the sample volumes with the desired outcomes were identified in the initial studies and analyzed by the Metaprop command.

Because the prevalence of COVID-19 was very low in patients with Parkinson’s disease, it was decided to combine the indexes in the case–control and cohort studies and report them in the form of the relative risk (RR) indicating the rate of risk of the preferred outcomes in people with Parkinson's.

To investigate the association using the cumulative RR with a 95% confidence interval, the methane command was used considering the logarithm and standard deviation of the logarithm of the RR. The heterogeneity between the studies was assessed using I2 and Q Cochrane tests. Also, Egger test was used to assess publication bias. The statistical analysis was performed using STATA 16.0, and the P value < 0.05 was considered.

Results

Qualitative results

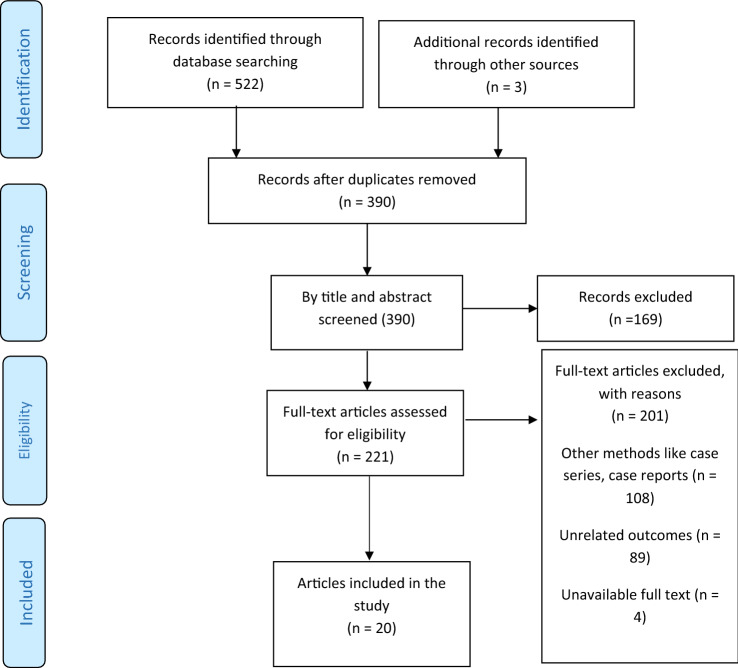

Based on the search strategy, 522 studies were obtained from the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Sciences, and EMBASE databases, of which 135 were excluded due to duplication, and 390 remained. After reviewing the title and full text of the articles, 20 studies remained for analysis, of which ten were cross-sectional studies [5, 6, 8–11, 20–23], five case–control studies [2, 3, 12, 24, 25], and five cohort studies [4, 7, 26–28] (Table 2), and all were from 2020 to 2021 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of search strategy and syntax

The quality assessment checklist (NOS checklist) of the observational studies showed 50% of the scores were between 6 and 8 and the other 50% were between 8 and 10, indicating most of these studies had a good quality (Table 2).

Depression in PD patients was examined in nine studies [5, 6, 8, 9, 21, 22, 25, 27, 28], of which two [25, 27] were performed before and during the pandemic and seven [5, 6, 8, 9, 21, 22, 27, 28] during the pandemic. The results of the two comparative studies showed the depression frequency in patients with PD increased during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the pandemic (32.6% vs. 34%)[25, 27]. In cross-sectional studies [5, 6, 8, 9, 21, 22] which determined the depression frequency in PD patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, the results showed a high frequency of depression (with an average above 20%) in these patients. The prevalence of depression among Parkinson's patients during the pandemic was evaluated in six reference studies.

Nine studies [2, 5, 8, 9, 20–22, 25, 27] examined and compared anxiety in PD patients before and during the pandemic, of which two studies [25, 27] checked the level before and during the pandemic and seven [2, 5, 8, 9, 20–22] during the pandemic. The results of the two comparative studies for anxiety levels before and during the pandemic showed a reduction in anxiety in patients with PD during the COVID-19 pandemic (36.6% vs. 30%)[25, 27]. However, cross-sectional studies [5, 8, 9, 20–22] showed a high prevalence of anxiety in these patients during the pandemic.

Sleep disorders were investigated in the selected articles in two categories of sleep problems and daytime sleepiness. Sleep problems were studied in nine articles [2, 6, 8, 9, 20–22, 24, 28], three of which [24] examined the changes after the occurrence of COVID-19 infection. In the first study [24], this symptom became more severe in 25.9% of patients over 65 years old and 11% of those under 65 years old. In the second study [6], the sleep-related symptoms became more severe in 27% of the study population, and in the third study [9], 41% of patients were affected. In a study [21], the average sleep time rose to 1.39 during the pandemic. Another study [28] found the sleep rate was reduced in 5% of people with PD. Daytime sleepiness was studied in one article [24] which found it became more severe in 25.9% of patients over 65 years old and 5.6% of ones under 65 years old. Finally, sleep disorders became more severe in the population with Parkinson’s disease in the post-pandemic period.

Quantitative results

Prevalence of COVID-19 and its associated outcomes in patients with Parkinson’s disease

The COVID-19 prevalence in Parkinson’s patients during the pandemic was evaluated in four studies [5, 11, 20, 23]. The sample size of patients with Parkinson’s disease was 71,261 people in 4 studies, of whom 761 were infected with COVID-19. The prevalence of COVID-19 in patients with PD was 1.06% (CI 95% 1.03%–1.1%; P = 0.02) with a heterogeneity rate of 70.36% after combining these studies (Table 3). The results of Egger test showed the publication bias occurred (B: 0.34, SE: 0.05, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of the prevalence of COVID-19, mental disorders, Parkinson’s symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease

| Categories | Outcomes | No. study (SS) | No. of patients | Pooled prevalence | Heterogeneity assessment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | p value | Test Q | |||||

| Outcomes of covid-19 | Covid-19 | 4 (71,261) | 761 | 1 .06% (1.03–1.1%) | 70.36% | 0.02 | 10.12 |

| Admission to Hospital | 3 (71,124) | 703 | 0.98% (0.91–1.7%) | 98.05% | 0.00 | 102.70 | |

| Mental Disorder | Depression | 6 (2156) | 1104 | 46% (29–64%) | 98.33% | 0.00 | 299.13 |

| Anxiety | 6 (1795) | 864 | 43% (24–63%) | 98.37% | 0.00 | 307.53 | |

| Parkinson’s symptoms | The physical activity | 5 (1352) | 768 | 57% (45–67%) | 92.96% | 0.00 | 56.83 |

| Tremor | 4 (1998) | 976 | 68% (35–94%) | 99.54% | 0.00 | 649.51 | |

| Dyskinesia | 3 (1898) | 866 | 50% (21–79%) | 99.45% | 0.00 | 362.97 | |

| Rigidity | 2 (598) | 458 | 79% (76–83%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 51.80 | |

| Gait impairments | 2 (932) | 377 | 43% (40–46%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 41.26 | |

| Freezing of gait | 2 (1330) | 555 | 42% (39–44%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 49.73 | |

| Sleep problems | 6 (1725) | 898 | 72% (45–92%) | 99.08% | 0.00 | 545.45 | |

The hospitalization prevalence in Parkinson’s patients during the pandemic was evaluated in three studies [5, 11, 23], in which the sample size of patients with Parkinson's disease was 71,124 people, of whom 703 were hospitalized due to COVID-19. After combining these studies, the hospitalization prevalence in patients with Parkinson’s disease was equal to 0.98% (CI 95% 0.95–1.02%; P = 0.00) with a heterogeneity rate of 98.05% (Table 3). The results of Egger test showed the publication bias occurred (B 0.22, SE 0.03, P < 0.001).

Prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease during the COVID-19 pandemic

The depression prevalence in patients with Parkinson’s disease during the pandemic was investigated in 6 studies with a sample size of 2156 patients, of whom 1104 had depression. The lowest prevalence was related to the study of Suzuki et al. [9] with 20% (CI 95% 13–29%), and the highest rate to the study of Van der Heide [6] with 72% (CI 95% 68–76%). The depression prevalence after combining these studies was 46% (CI 95% 29–64%; P = 0.00) with heterogeneity of 98.33% (Table 3). The results of Egger test showed the publication bias occurred (B 0.69, SE 0.12, P < 0.001). The anxiety prevalence in Patients with Parkinson's disease during the pandemic was evaluated in 6 studies with a sample size of 1,795 people, of whom 864 suffered from anxiety [5, 8, 9, 20–22]. The lowest prevalence was related to the study of Xia et al. [21] with 21% (CI 95% 14–29%), and the highest rate to the study of Salari et al. [20] with 81% (CI 95% 73–87%). The anxiety prevalence in patients with PD was 43% (CI 95% 24–63%; P = 0.00) with the heterogeneity of 98.37% after combining these studies (Table 3). The results of Egger test showed the publication bias occurred (B 1.09, SE 0.88, P < 0.001).

The anxiety prevalence in Parkinson’s patients was different in Asia and Europe. Of course, only one study was conducted in Europe, but in Asia, five studies were published in this regard. After combining the studies conducted in Asia, the prevalence was 38% (95% CI 16–63%; P = 0.00) while it was 65% in Europe (95% CI 61–69%). Also, depression was higher in the Europe continent (Prevalence: 68%; % 95 CI 66–71%).

Physical activities in Parkinson’s patients during the Covid-19 pandemic

The prevalence of physical activities in Parkinson’s patients during the pandemic period was investigated in five studies [5, 6, 9, 10, 21]. The study of Suzuki et al. [9] had the lowest prevalence with 44% (CI 95% 34–54%), and the highest was related to the study of Xia et al. [21] with 73% (CI 95% 64–81%). Finally, the prevalence of physical activities in patients with PD was 57% (CI 95% 45–67%; P = 0.00) with the heterogeneity of 92.96% after combining these studies (Table 3). The results of Egger test showed the publication bias occurred (B 0.33, SE 0.05, P < 0.001).

Prevalence of symptoms in Parkinson’s patients during the COVID-19 pandemic

Four studies [5, 6, 9, 22] investigated the tremor prevalence in Parkinson’s patients during the pandemic. The tremor prevalence in patients with Parkinson’s disease during the pandemic was evaluated in four studies with a sample size of 1,998 patients, of whom 976 had tremors. The lowest rate was related to the study of Kumar et al. [22] with 21% (CI 95% 19–24%), and the highest to the study of Suzuki et al. [9] with 100% (CI 95% 96–100%). The tremor prevalence was 68% (CI 95% 35–94%; P = 0.00) with the heterogeneity of 99.54% (I2) after combining these studies (Table 3). The results of Egger test showed the publication bias occurred (B 0.11, SE 0.01, P < 0.001). The results of the meta-analysis also showed the prevalence of dyskinesia, rigidity, gait, and freezing of gait were equal to 50% (CI 95% 21–79; P = 0.00), 79% (CI 95% 76–83; P = 0.00), 43% (CI 95% 40–46; P = 0.00), and 42% (CI 95% 39–44; P = 0.00), respectively (Table 3). The results of subgroup analyses based on the different continents showed the tremor prevalence in European patients was higher than its prevalence in those living in Asia (Table 3).

Sleep disorders in patients with Parkinson’s before and during the incidence of the COVID-19 pandemic

The prevalence of sleep problems in patients with Parkinson’s disease during the COVID-19 pandemic was evaluated in 6 studies with a sample size of 1,725 people, of whom 898 had sleep disorders. The prevalence of sleep problems in Parkinson’s patients during the pandemic period was 72% (CI 95% 45–92%; P = 0.00) with a rate of heterogeneity of 99.08% after combining these studies (Table 3). The results of Egger test showed the publication bias occurred (B 1.33, SE 0.92, P < 0.001).

The association of Parkinson’s disease with the occurrence of COVID-19 and its related outcomes

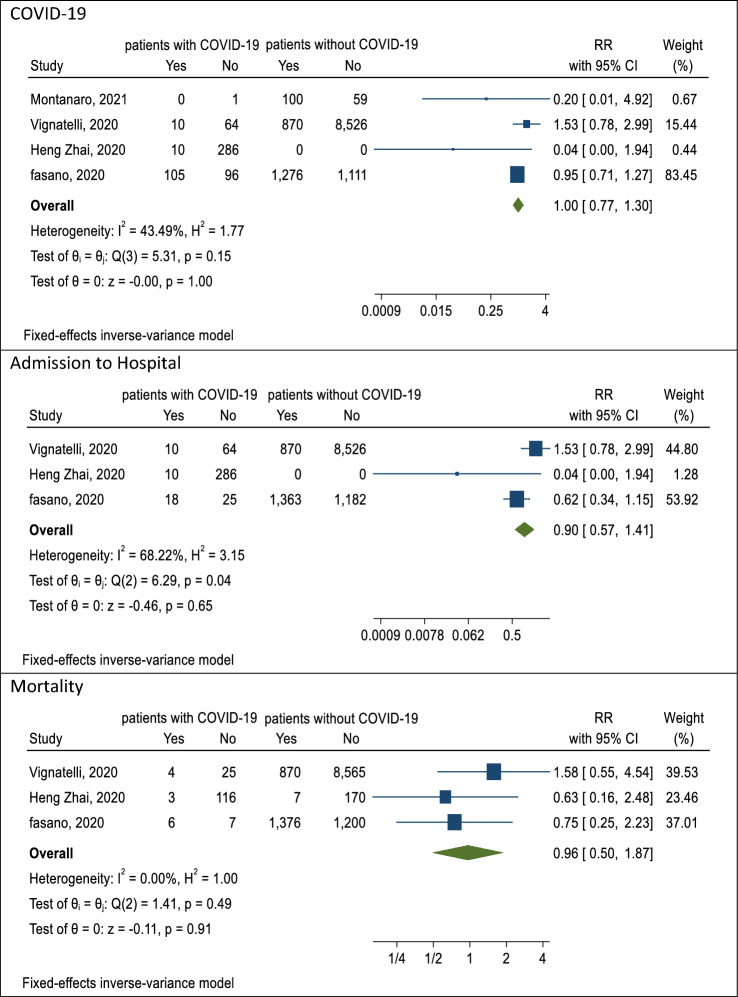

The association of COVID-19 with PD during the pandemic was studied in four [3, 4, 7, 25] articles. The lowest RR was related to the study of Montanaro et al. [25] with 0.20 (CI 95% 0.01–4.92), and the highest RR to the study of Vignatelli et al. [7] with 1.53 (CI 95% 0.78–2.99). The reported RR was 1.00 (CI 95% 0.77–1.30; P = 0.15) with a heterogeneity rate of 43.49% after combining these studies (Table 4). Also, the results after combining the studies [3, 4, 7] showed a reduction in the hospitalization rate of those with PD (RR 0.90; CI 95% 0.57, 1.41; P = 0.04; I square 43.49%) due to not seeking care for fear of COVID-19 infection (Table 4 and Fig. 2). The results of Egger test showed the publication bias not occurred (B: 2.33, SE: 1.00, P = 0.44).

Table 4.

Meta-analysis of RR of outcomes and symptoms of COVID-19 in patients with Parkinson’s disease

| Categories | Outcomes | No. of study | Sample size PD | Sample size non-PD | No. of covid-19 | Pooled RR | Heterogeneity assessment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | I2 | p value | Test Q | ||||||

| Outcomes of covid-19 | Covid-19 | 4 (12,514) | 2371 | 10,143 | 125 | 447 | 2246 | 9696 | 1.00 (0.77–1.30) | 43.49% | 0.15 | 5.31 |

| Admission to Hospital | 3 (12,354) | 2271 | 10,083 | 38 | 357 | 2233 | 9708 | 0.9 (0.57–1.41) | 68.22% | 0.04 | 6.30 | |

| Mortality | 3 (12,345) | 2271 | 10,083 | 13 | 148 | 2253 | 9935 | 0.96 (0.50–1.87) | 0.00 | 0.49 | 1.42 | |

| Symptoms of Covid-19 | Fever | 3 (3044) | 1491 | 1553 | 89 | 320 | 1402 | 1233 | 0.92 (0.67–1.27) | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.56 |

| Cough | 3 (3044) | 1491 | 1553 | 80 | 246 | 1411 | 1307 | 1.04 (0.73–1.48) | 28.83% | 0.25 | 2.93 | |

| Respiratory difficulties | 3 (3044) | 1491 | 1553 | 26 | 165 | 1465 | 1388 | 0.63 (0.38–1.07) | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.55 | |

| Diarrhea | 3 (3044) | 1491 | 1553 | 36 | 68 | 1455 | 1485 | 1.01 (0.62–1.67) | 0.00 | 0.44 | 1.34 | |

| Smell reduction | 2 (2748) | 1481 | 1267 | 17 | 19 | 1464 | 1248 | 0.79 (0.41–1.54) | 37.23% | 0.21 | 1.61 | |

| Taste reduction | 2 (2748) | 1481 | 1267 | 19 | 17 | 1462 | 1250 | 0.97 (0.50–1.87) | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.98 | |

| Muscle/Joint | 2(2884) | 1391 | 1493 | 38 | 97 | 1353 | 1396 | 1.06 (0.55–1.68) | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.18 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2(2884) | 1391 | 1493 | 29 | 44 | 1362 | 1449 | 1.23 (0.70–2.14) | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.00 | |

| Fatigue | 2(2884) | 1391 | 1493 | 47 | 185 | 1344 | 1308 | 1.20 (0.77–1.88) | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.59 | |

Fig. 2.

The pooled RR of association outcomes of covid-19 in Parkinson’s patients

The association of mortality and PD during the pandemic was examined, and the results of the meta-analysis showed the risk of mortality caused by COVID-19 in patients with Parkinson’s disease was 0.96 (CI 95% 0.50–1.87; P = 0.49) with the heterogeneity of 0% [3, 4, 7] (Table 4 and Fig. 2). The results of Egger test showed the publication bias not occurred (B 1.09, SE 0.77, P = 0.20).

The results of the meta-analysis showed the risk of fever, cough, respiratory problems, diarrhea, a loss of sense of smell, and a decreased sense of taste caused by COVID-19 in patients with Parkinson’s were equal to 0.92 (CI 95% 0.67–1.27; P = 0.75), 1.04 (CI 95% 0.73–1.48; P = 0.25), 0.63 (CI 95% 0.38–1.07; P = 0.76), 1.01 (CI 95% 0.62–1.67; P = 0.44), 0.79 (CI 95% 0.41–1.54; P = 0.21), and 0.97 (CI 95% 0.50–1.87; P = 0.32), respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

The prevalence of PD symptoms during the pandemic, among which sleep problems, rigidity, and tremor were more prevalent, was examined in this study. Home quarantine, travel ban, and decrease in physical activities during the pandemic were among the factors contributing to the increase in sleep disorders in patients with PD [29]. In addition, insomnia has been exacerbated in this population during the pandemic due to the fact that PD patients are primarily elderly with various underlying diseases and take numerous drugs [30]. Anxiety and depression caused by the pandemic are other factors affecting the increase in insomnia in patients with PD [29, 31]. Studies of Xia et al. [20] and Kitani-Morii et al. [8] found sleep disorders increased during the COVID-19 pandemic and were associated with depression and anxiety in patients with inadequate access to medical services.

Studies showed physical activities were associated with reducing stress levels, so reduced physical activities during this period became one of the factors increasing stress levels in people [6]. In Parkinson’s patients, the amount of experienced stress was related to their physical symptoms, and the increase in anxiety and depression in this period was grounds for increasing their physical symptoms [6, 32–34]. Suzuki et al. [9] and Balci et al. [23] in their studies found physical disorders, such as rigidity and tremor, sleep disorders, depression, and anxiety increased because of COVID-19 conditions.

In this study, the association between the symptoms and outcomes of COVID-19 and PD was investigated in addition to their prevalence. The results of this meta-analysis showed there was no significant association between COVID-19 and the hospitalization rate of patients with PD and without PD. Parkinson’s patients were less likely to visit hospitals and medical centers during the pandemic for Parkinson’s-related care because of fear for COVID-19 infection, which may be the reason for decreased hospitalization rates of this population.

Also, the rate of mortality caused by COVID-19 did not show a significant association with Parkinson’s disease. In PD patients, most of the variables, such as age and duration of COVID-19, seemed to be insignificantly different from those of the general population [12, 35]. Zhai et al. [35] found no difference between patients with PD and healthy individuals in terms of COVID-19 infection and hospitalization. Their results are in line with the ones of this meta-analysis. Scherbaum et al. [11] found the incidence, hospitalization, and mortality caused by COVID-19 were associated with PD. A small number of studies also showed the duration of PD and the age of patients were not significantly related to the exacerbation of COVID-19 complications [12]. However, a number of other studies showed the duration of Parkinson's disease more than three years and older age were not factors affecting the exacerbation of COVID-19 symptoms and increase in its death rate [3]. Although there are conflicting results in the world, the present study rejects this association because of the higher sample size of our meta-analysis. It is not yet fully understood whether Parkinson’s-related symptoms have an effect on the exacerbation of COVID-19 symptoms or the increase in the mortality rate. Therefore, cohort studies with larger sample sizes from many different countries are needed.

The meta-analysis results showed the symptom of fatigue due to COVID-19 was 1.20 times greater in patients with PD than ones without PD, which might be due to the fact that people with PD have been often elderly and have had a longer illness duration [13]. The results of studies conducted by Antonini et al. [13] and Zhai et al. [4] are consistent with those of this meta-analysis. So, fatigue was found to be one of the predominant COVID-19 symptoms in Parkinson’s patients.

Parkinson’s patients were highly affected by mental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a high prevalence of anxiety and depression in these patients who have been more prone to these mental disorders due to old age, underlying diseases, taking Parkinson’s drugs, quarantine conditions, and reduced contacts with family members [36, 37]. The results of this meta-analysis and those of Montanaro et al. [24] showed anxiety and distress increased due to the unavailability of care in medical centers and the discontinuation of drug treatments and sports activities. The results of another study performed by Santos-García et al. [5] showed a high prevalence of depression and anxiety, which were in line with the findings of this meta-analysis.

In this meta-analysis, the occurrence of selection bias in the sections of search strategy, screening, and data extraction has occurred less. Because in these sections, two researchers independently to perform these activities. But publication bias has occurred in this meta-analysis especially in the combination of cross-sectional studies to determine pooled prevalence. The occurrence of publication bias is expected in cross-sectional studies, but this bias is occurrence less in other effect sizes like risk ratio. Publication and selection biases have occurred in the present meta-analysis, but these biases have not affected the pooled effect sizes. The reason is that the number of sufficient studies and the sample size of these studies are also very high, so it can be said that the possibility of this bias and especially the occurrence of small study effect in connection with these biases in this meta-analysis is low.

Strengths

This study was the first meta-analysis in the world about Parkinson's disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this meta-analysis, most of the reviewed studies had appropriate populations. The examined studies were conducted in different parts of the world for estimating the prevalence of COVID-19 infection. In this study, the heterogeneity was low, and in some cases, the studies were completely homogeneous.

Limitations

The number of studies in some subgroups, such as symptoms of Parkinson's disease and COVID-19, was low, making it difficult to obtain more accurate results. Also, in the report of the selected articles, confounding variables, such as age, sex, and the duration of Parkinson's disease, were discussed less, which prevented the use of many statistical methods, such as meta-regression and subgroup analysis.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed the rates of mortality and hospitalization were not significantly different between Parkinson’s patients and the general population. However, the PD symptoms and mental disorders in patients with Parkinson’s significantly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, some steps need to be taken to manage them. This study recommends the launch of applications and online services facilitating doctor visits, and monitoring patients’ medications, as well as private and group counseling services, and exercise classes tailored to individual needs. Such suggestions could improve the care for Parkinson's patients during both pandemic periods, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and non-pandemic periods.

Author contributions

YM: designed the study, determined the study concept, and was involved in data analysis and doing statistics; YM, MA, GM, PM, and MA: prepared the manuscript; YM and SR: edited the manuscript; SR: prepared the figures. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funds, grants, or other supports were received.

Data availability

Data for analyses are available by the corresponding author on request.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

This work was recorded in the Research Committee of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hsieh RL, Lee WC (2022) Effects of intra-articular coinjections of hyaluronic acid and hypertonic dextrose on knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabilit. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Del Prete E, Francesconi A, Palermo G, Mazzucchi S, Frosini D, Morganti R, et al. Prevalence and impact of COVID-19 in Parkinson's disease: evidence from a multi-center survey in Tuscany region. J Neurol. 2021;268(4):1179–1187. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fasano A, Cereda E, Barichella M, Cassani E, Ferri V, Zecchinelli AL, et al. COVID-19 in Parkinson's disease patients living in Lombardy, Italy. Mov Disord. 2020;35(7):1089–1093. doi: 10.1002/mds.28176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhai H, Lv YZ, Xu Y, Wu Y, Zeng WQ, Wang T, et al. Characteristic of Parkinson's disease with severe COVID-19: a study of 10 cases from Wuhan. J Neural Transm. 2021;128(1):37–48. doi: 10.1007/s00702-020-02283-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos-García D, Oreiro M, Pérez P, Fanjul G, Paz González JM, Feal Painceiras MJ, et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on Parkinson's disease: a cross-sectional survey of 568 Spanish patients. Mov Disord. 2020;35(10):1712–1716. doi: 10.1002/mds.28261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Heide A, Meinders MJ, Bloem BR, Helmich RC. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological distress, physical activity, and symptom severity in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(4):1355–1364. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vignatelli L, Zenesini C, Belotti LMB, Baldin E, Bonavina G, Calandra-Buonaura G, et al. Risk of hospitalization and death for COVID-19 in people with Parkinson's disease or Parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2021;36(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/mds.28408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitani-Morii F, Kasai T, Horiguchi G, Teramukai S, Ohmichi T, Shinomoto M, et al. Risk factors for neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease during COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):e0245864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki K, Numao A, Komagamine T, Haruyama Y, Kawasaki A, Funakoshi K, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of life of patients with Parkinson's disease and their caregivers: a single-center survey in tochigi prefecture. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(3):1047–1056. doi: 10.3233/JPD-212560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavallieri F, Sireci F, Fioravanti V, Toschi G, Rispoli V, Antonelli F, et al. Parkinson's disease patients' needs during the COVID-19 pandemic in a red zone: a framework analysis of open-ended survey questions. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(10):3254–3262. doi: 10.1111/ene.14745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scherbaum R, Kwon EH, Richter D, Bartig D, Gold R, Krogias C, et al. Clinical profiles and mortality of COVID-19 inpatients with Parkinson's disease in Germany. Mov Disord. 2021;36(5):1049–1057. doi: 10.1002/mds.28586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cilia R, Bonvegna S, Straccia G, Andreasi NG, Elia AE, Romito LM, et al. Effects of COVID-19 on Parkinson's disease clinical features: a community-based case-control study. Mov Disord. 2020;35(8):1287–1292. doi: 10.1002/mds.28170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antonini A, Leta V, Teo J, Chaudhuri KR. Outcome of Parkinson's disease patients affected by COVID-19. Mov Disord. 2020;35(6):905–908. doi: 10.1002/mds.28104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schirinzi T, Cerroni R, Di Lazzaro G, Liguori C, Scalise S, Bovenzi R, et al. Self-reported needs of patients with Parkinson’s disease during COVID-19 emergency in Italy. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(6):1373–1375. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04442-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moletta L, Pierobon ES, Capovilla G, Costantini M, Salvador R, Merigliano S, et al. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during Covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2020;79:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma A, Maxwell CR, Farmer J, Greene-Chandos D, LaFaver K, Benameur K. Initial experiences of US neurologists in practice during the COVID-19 pandemic via survey. Neurology. 2020;95(5):215–220. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helmich RC, Bloem BR. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson’s disease: hidden sorrows and emerging opportunities. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(2):351. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Kolk NM, de Vries NM, Kessels RP, Joosten H, Zwinderman AH, Post B, et al. Effectiveness of home-based and remotely supervised aerobic exercise in Parkinson's disease: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(11):998–1008. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salari M, Zali A, Ashrafi F, Etemadifar M, Sharma S, Hajizadeh N, et al. Incidence of anxiety in Parkinson's disease during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Mov Disord. 2020;35(7):1095–1096. doi: 10.1002/mds.28116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia Y, Kou L, Zhang G, Han C, Hu J, Wan F, et al. Investigation on sleep and mental health of patients with Parkinson's disease during the Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2020;75:428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar N, Gupta R, Kumar H, Mehta S, Rajan R, Kumar D, et al. Impact of home confinement during COVID-19 pandemic on sleep parameters in Parkinson's disease. Sleep Med. 2021;77:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown EG, Chahine LM, Goldman SM, Korell M, Mann E, Kinel DR, et al. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(4):1365–1377. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balci B, Aktar B, Buran S, Tas M, Colakoglu BD. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity, anxiety, and depression in patients with Parkinson's disease. Int J Rehabil Res. 2021;44(2):173–176. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montanaro E, Artusi CA, Rosano C, Boschetto C, Imbalzano G, Romagnolo A, et al (2021) Anxiety, depression, and worries in advanced Parkinson disease during COVID-19 pandemic. Neurol Sci. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Buccafusca M, Micali C, Autunno M, Versace AG, Nunnari G, Musumeci O. Favourable course in a cohort of Parkinson's disease patients infected by SARS-CoV-2: a single-centre experience. Neurol Sci. 2021;42(3):811–816. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-05001-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El Otmani H, El Bidaoui Z, Amzil R, Bellakhdar S, El Moutawakil B, Abdoh RM. No impact of confinement during COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depression in Parkinsonian patients. Revue neurologique. 2021;177(3):272–274. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song J, Ahn JH, Choi I, Mun JK, Cho JW, Youn J. The changes of exercise pattern and clinical symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020;80:148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta R, Grover S, Basu A, Krishnan V, Tripathi A, Subramanyam A, et al. Changes in sleep pattern and sleep quality during COVID-19 lockdown. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(4):370–378. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_523_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Videnovic A. Management of sleep disorders in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord. 2017;32(5):659–668. doi: 10.1002/mds.26918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voitsidis P, Gliatas I, Bairachtari V, Papadopoulou K, Papageorgiou G, Parlapani E, et al. Insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Greek population. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113076. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subramanian I, Farahnik J, Mischley LK. Synergy of pandemics-social isolation is associated with worsened Parkinson severity and quality of life. NPJ Parkinson's Dis. 2020;6:28. doi: 10.1038/s41531-020-00128-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zach H, Dirkx M, Bloem BR, Helmich RC. The clinical evaluation of Parkinson's tremor. J Parkinsons Dis. 2015;5(3):471–474. doi: 10.3233/JPD-150650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zschucke E, Renneberg B, Dimeo F, Wüstenberg T, Ströhle A. The stress-buffering effect of acute exercise: evidence for HPA axis negative feedback. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:414–425. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhai H, Lv Y, Xu Y, Wu Y, Zeng W, Wang T, et al. Characteristic of Parkinson’s disease with severe COVID-19: a study of 10 cases from Wuhan. J Neural Transm. 2021;128(1):37–48. doi: 10.1007/s00702-020-02283-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhidayasiri R, Virameteekul S, Kim JM, Pal PK, Chung SJ. COVID-19: an early review of its global impact and considerations for Parkinson's disease patient care. J Mov Disord. 2020;13(2):105–114. doi: 10.14802/jmd.20042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hemmerle AM, Herman JP, Seroogy KB. Stress, depression and Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 2012;233(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data for analyses are available by the corresponding author on request.