Abstract

Background

Immediate postpartum intrauterine device (IPPIUCD) use remains too low in Ethiopia and there are high levels of unmet need for IPPIUCD. This systematic review and meta-analysis investigates individual studies conducted in Ethiopia on IPPIUCD use and influencing factors.

Method

Extensive database searching was done using Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopes, Cochrane library, Web of Science, and Science Direct search engines. Data were extracted and analyzed using Cochrane review manager version 5.4.1. A random-effects model with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to estimate the pooled magnitude of IPPIUCD use. Forest plot was used to estimate the pooled IPPIUCD use and inverse variance was used to identify the presence of heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed by using funnel plots and Egger's statistical tests.

Result

This study showed that the pooled use of IPPIUCD in Ethiopia was 8.37% (95% CI: 4.32, 16.21). Those who had heard about IPPIUCD were 4.2 times (OR = 4.2, 95% CI: 1.51, 11.68) more likely, had birth interval >3 years were 3.90 times (OR = 3.90, 95% CI: 1.68, 9.05) more likely, had good knowledge were 4.44 times (OR = 4.44, 95% CI: 2.26, 8.76) more likely and counseled clients were 3.99 times (OR = 3.99, 95% CI: 1.28, 12.37) more likely to use IPPIUCD; and the odds of using IPPIUCD was 45% (OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.40, 0.77) less likely among aged 15–24 years old to use IPPIUCD.

Conclusion

IPPIUCD use in Ethiopia was low. Age category, ever heard about IPPIUCD, level of knowledge, birth interval and being counseled about IPPIUCD were statistically significant factors influencing IPPIUCD use.

Keywords: Ethiopia, Immediate postpartum, IUCD, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

Ethiopia; Immediate postpartum; IUCD; Meta-analysis; Systematic review.

1. Background

Immediate post partal intrauterine contraceptive device (IPPIUCD) is one of family planning methods, and it is safe and very effective, reliable and long acting reversible family planning method (LARC) [1, 2]. IPPIUCD placed in the uterus after 10 min of placental expulsion; is very safe, effective, and efficient method of overcoming women's desire for long-acting but reversible method of family planning [3, 4]. In addition to post placental insertion IPPIUCD can also be placed within 48 h and after 4 weeks of delivery [3, 5, 6, 7].

The intra-uterine device (IUD) were used as an interval method for the last many years (after 6 weeks postpartum), but it has not been always used as IPPIUCD [8]. But now it is an effective immediate post partal contraception with fewer side effects and good patient satisfaction [8, 9, 10]. This long acting reversible contraceptive method can be placed after termination of pregnancy, spontaneous delivery and during operational delivery [11].

Institutional delivery and child immunization are the determinants most related with voluntary use of IPPIUCD [12, 13]. Different articles have verified the necessity of effective counseling and community participation to improve IPPIUCD use [12, 13, 14, 15]. The difficulties identified for IPPIUCD use were perceiving low risk of conception during the postpartal period among health care professionals and most importantly women needed to use the method, small rate of institutional deliveries, and cultural restrictions [16, 17, 18].

Most of postpartum women in Ethiopia shows their preference to extend pregnancy for more than one year following current birth [19]; but use of IPPIUCD methods reported previously was very low [20, 21, 22] and having unwanted pregnancy is very high during the postpartum period [23, 24]. In addition women who use modern contraceptive methods like LARC, including IPPIUCD and implants, was low (<10%) [25].

According to 2019 mini Ethiopian demographic health survey IUD use was 2% whereas IPPIUCD use was very low [25]. It was 3.3% in Debretabor [22], 4% in west Gojjam Zone [26], higher than the listed figures in urban part of Ethiopia [19, 21] and much more less on Somali (0.1) and Afar regions (0.2) [27].

Moreover, identified factors for low use of IPPIUCD range from scarced provision of IUCDs to absences of staff able in offering family planning counseling and services to previous misconceptions about IUCDs among both health professionals and the community [3, 28, 29, 30, 31]. There for improving access to effective IPPIUCD use can minimize the probability of unwanted pregnancy and short birth intervals [32].

Even though there were number of primary articles conducted on IPPIUCD in different part of Ethiopia, there is no study which represents as a reference on the use of immediate postpartal intrauterine contraception and the pooled effects of IPPIUCD use and influencing factors in the country. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis is planned to verify the best available articles to pool the use of immediate postpartal modern contraception in Ethiopia. The result and conclusion of this study will bring scientific information to be used by program planners, other researchers and policy developers to have qualified service delivery. Besides, it also used as the health professionals in using scientific data for implementation in the setup where the service is provided.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

The authors have assessed the PROSPERO database (http://www.library.ucsf.edu/) for all published or ongoing researches available related to the title to skip any further duplication. Accordingly the result brought that there were no ongoing or published articles in the area of this title. Therefor this review and meta-analysis was registered on PROSPERO with an identification number CRD42021268754 on 19/08/2021. This review and meta-analysis was conducted to verify the pooled use of IPPIUCD in Ethiopia. Scientific consistency was formulated by using PRISM checklist [33].

2.2. Information source

A systematic and genuine search of the research articles was done via the following listed databases. Google, Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopes, Cochrane library, the Web of Science, and Science Direct search engines were included in the review.

All articles in this study were obtained using the following terms “Immediate postpartum, Postpartum mothers, Immediate postpartum IUCD, Postpartum period, Post-delivery, puerperal period, Contraception, Family planning, Contraceptive, Utilization, Use, IPPIUD, PPIUD, IUD, Ethiopia”. The search was performed using the following key search terms: “AND” and “OR” boolean operators individually and in combination with each other. Moreover, the reference lists of all the included studies were also searched to identify any other studies that may have been missed by the search strategy. The search for all researches was done from June 10th to July 5th, 2021 without limiting the publication dates of the literatures.

2.3. Eligibility criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion criteria

Articles published in the international reputable journals and conducted in Ethiopia and had results on IPPIUCD use were included in this study. Published researches were searched and screened for inclusion in the final analysis. This study included available observational study designs (cross-sectional studies and case-control studies). All researches that were published, master's thesis found in institutional repositories, and PhD dissertation accessed from the repositories till the final date of data analysis and submission of this manuscript to this journal were included in accordance with these criteria.

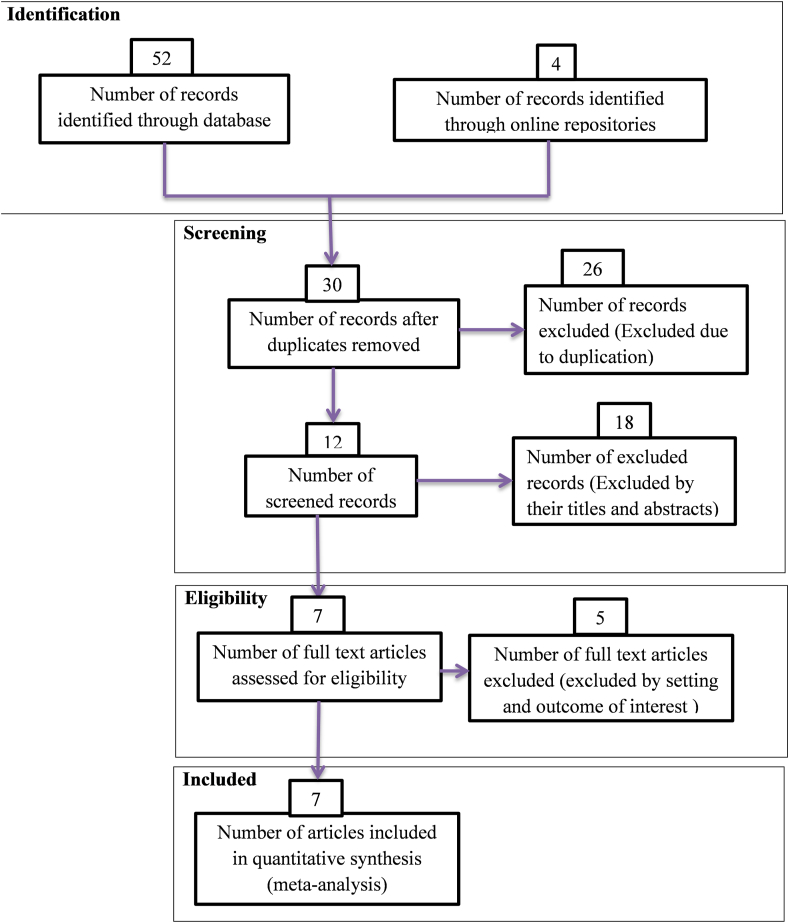

During the beginning of our search 56 studies were found of which 26 were skipped due to duplication and the rest 30 studies were identified for eligibility. From 30 studies 18 were excluded by highlight review on their abstracts and 12 studies assessed for full text from this 5 studies excluded because of not relevant to the current review and the remaining 7 studies were included in the final meta-analysis of this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagrams of included studies in the Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of IPPIUCD use in Ethiopia, 2021.

2.3.2. Exclusion criteria

Studies without sound methodologies, and review and meta-analysis were not included in this analysis. Duplication of results in studies and outcome variable measures with inconsistency were excluded from the final analysis. Studies which incorporate other types of contraception as an immediate postpartum family planning other than IUD were excluded.

2.4. Study outcome

The first main center of attention in this systematic review and meta-analysis was IPPIUCD use. IPPIUCD use is defined as placing of IUCD to the postpartum mother's womb 10 min after the expulsion of placenta to 48 h of delivery [19, 34]. The second main center attention in this study was influencing factors of IPPIUCD use. Data for this outcome was extracted in a format of rows and columns on the Review Manager Spreadsheet, and then the software calculates odds ratio for each factor, p-value and other necessary statistics.

Influencing factors included in this systematic review and meta-analysis were fertility plan (Yes, no), heard about IPPIUCD (yes, no), counseled about IPPIUD (yes, no), birth interval (<3 years, >3 years), time of counseling about IPPIUCD (on ANC, on labor), discuss about IPPIUCD with their partner (yes, no), age group [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44] and level of education (literate, illiterate), knowledge (good, poor).

2.5. Quality assessment and data extraction

The basic quality of included research articles was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). The NOS was created to evaluate the quality of observational research articles in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Data of this study were extracted by the two authors (YFG and TMB) using a standardized data extraction checklist on review manager.

This systematic review and meta-analysis uses PRISMA flow chart to differentiate and pick important articles for the analysis. During commencement, duplicated types of studies were not included by using Medley version 1.19.4 referencing tool. The articles were excluded by adding highlight reviewing to their titles and abstracts before assessing the whole text. Full text studies or research results were assessed for the rest studies. Depend on the stated eligibility criteria above; eligibility of the articles was evaluated.

For the dependent variable (IPPIUCD use) and independent variables (factors influencing IPPIUCD use), data were extracted using review manager, then odds ratio was calculated based on the findings of the primary articles. The checklist for data extraction contains the name of authors, publication year, region (the study area), study design, the magnitude of IPPIUCD use, sample size, and response rate (Table 1). All literatures was checked by the two authors independently (YFG and TMB). There were no disagreements between the two independent reviewers.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of 7 included articles to pool IPPIUCD use in Ethiopia, 2021.

| Authors | Year | Region | Design | Study area | Sample size | Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandefro et al. [35] | 2021 | Amhara | Case control | Gondar | 450 | – |

| Dereje et al. [36] | 2021 | Addis Ababa | Cross-sectional | Paulos | 586 | 12.97 (10.1, 15.5) |

| Abenezer et al. [37] | 2021 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | Gojjam | 423 | 4.02 (1.65, 5.24) |

| Yohannes et al. [19] | 2021 | Addis Ababa | Cross-sectional | Lideta | 286 | 26.6 (21.3, 31.8) |

| Haymanot et al. [38] | 2020 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | Debretabor | 182 | 3.3 (2.85, 3.75) |

| Seid et al. [39] | 2020 | SNNPR | Case control | Gamo | 510 | – |

| Lidetu et al. [40] | 2017 | SNNPR | Cross-sectional | Sidama | 310 | 21.9 (17.3, 26.5) |

SNNPR: Southern Nation Nationality and Peoples Region.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Eligible primary studies were extracted using a format prepared in Review Manager Spreadsheet. Cochrane Review Manager Version 5.4 software was used to calculate the pooled use of IPPIUCD with a 95% confidence level by using the Der Simonian and Laird random-effects meta-analysis (random-effects model).

2.7. Heterogeneity and publication bias

The degree of heterogeneity between the included studies was evaluated by determining the p-values of I2-test statistics. I2 test statistics scores of 0, 25, 50, and 75% were taken as no, low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively [41]. Due to the observed high heterogeneity across studies, we used a random effect model to assess pooled estimate. Publication bias was checked by funnel plot. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used as cutoff point for statistical significance of publication bias.

3. Results

3.1. Selection and characterization of included studies

Seven articles included in this systematic review and meta-analysis was summarized in Table 1. Five articles had used cross-sectional study design [19, 36, 37, 38, 40] while two articles were case control studies [35, 39] with a sample size ranging from 182 in Debretabor town [38] to 586 in Addis Ababa [36]. In relation with the region in which the study was conducted, two articles were from the SNNPR [39, 40], two from Addis Ababa [19, 36] and three from Amhara region [35, 37, 38] (Table 1).

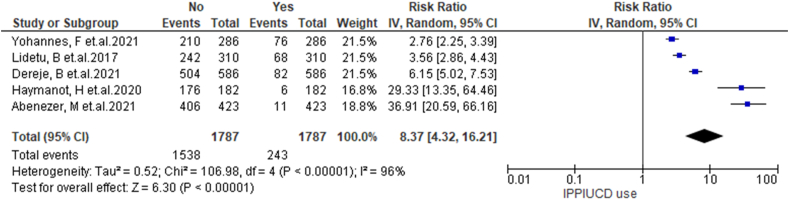

To obtain the pooled use of IPPIUCD random effect model was used with p value less than 0.001. This study showed that the pooled use of IPPIUCD in Ethiopia was 8.37% (95% CI: 4.32, 16.21) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the pooled IPPIUCD use in Ethiopia, 2021.

3.2. IPPIUCD use

In this systematic review and meta-analysis fertility plan, ever heard about IPPIUCD, counseled about IPPIUD, birth interval, time of counseling about IPPIUCD, discuss about IPPIUCD with their partner, age group and level of education and level of knowledge were statistically significant at one or more primary studies [19, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40]. However age category, ever heard about IPPIUCD, level of knowledge, birth interval, counseled about IPPIUCD were stay statistically significant in this meta-regression.

This review analyzed data from 1787 immediate postpartal women to estimate the pooled use of IPPIUCD. A total of 5 (4 published and one unpublished) articles were included in this review yielding the pooled IPPIUCD use in Ethiopia 26.6% (95% CI: 19.88%, 29.48%) with the lowest, 3.3% (95% CI: 2.85%, 3.75%) in Debretabor [38] and the highest 80.32% (95% CI: 21.3%, 31.8%) in Addis Ababa [19] (Table 1).

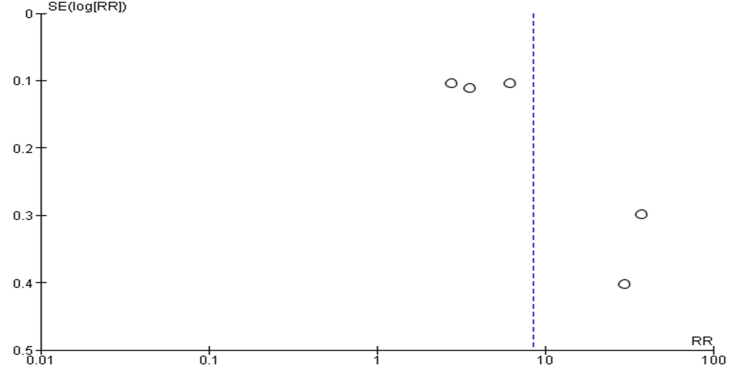

3.3. Publication bias

Bias among the included studies was checked by funnel plot and Egger test at a 5% significant level. The funnel plot was asymmetry, and the Egger test showed no statistical significance for the presence of publication bias with p-value of 0.18 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot with 95% confidence limit of the pooled use of IPPIUCD in Ethiopia, 2021.

3.4. Factors influencing IPPICD use in Ethiopia

In the current review and meta-analysis ever heard about IPPIUCD, birth interval, age category, level of knowledge, counseled about IPPIUCD were strongly associated with IPPIUCD use. However, fertility plan, level of education, time of counseling, discuss with partner about IPPIUCD showed no statistically significant association with IPPIUCD use.

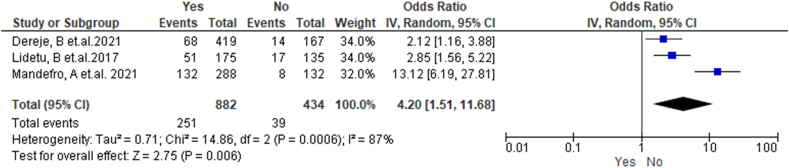

In the current review and meta-analysis three studies showed that ever heard about IPPIUCD were positively associated with IPPIUCD use [35, 36, 40]. Those who had heard about the method were 4.2 times (OR = 4.2, 95% CI: 1.51, 11.68) more likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those who never had heard. Random effect model was used with I2 value of 87% and P value of 0.006 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of association between IPPIUCD uses and ever heard about IPPIUCD in Ethiopia, 2021.

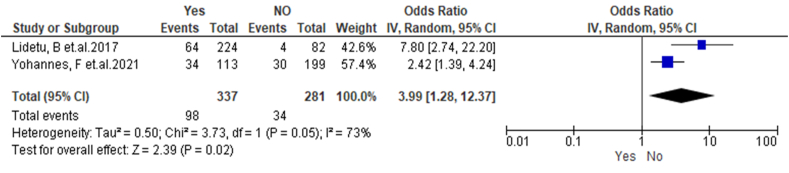

In this meta-regression two studies [19, 40] have showed that counseled clients were 3.99 times (OR = 3.99, 95% CI: 1.28, 12.37) more likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those who had not counseled. Since the studies were heterogeneous with I2 value of 73% random effect model was used (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of association between IPPIUCD uses and counseled about IPPIUCD in Ethiopia, 2021.

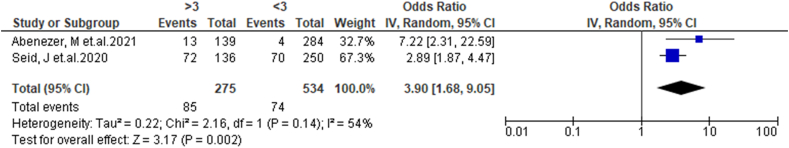

In this meta-regression two studies [37, 39] have showed that those who had birth interval >3 years were 3.90 times (OR = 3.90, 95% CI: 1.68, 9.05) more likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those who had birth interval <3years; by using random effect (I2 = 54%, p = 0.002) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of association between IPPIUCD uses and birth interval in Ethiopia, 2021.

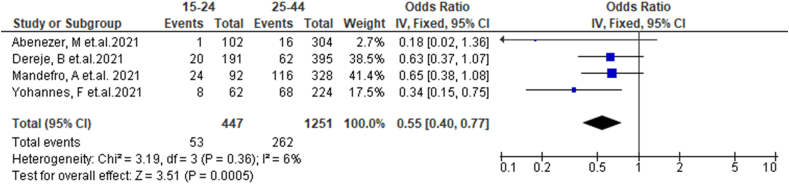

Four studies [19, 35, 36, 37] included in this meta-regression showed 45% of participant aged 15–24 (OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.40, 0.77) were less likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those aged 25–44; by fixed effect with I2 = 6% and P = 0.002 (Figure 6).

Four studies [19, 35, 36, 37] included in this meta-regression showed 45% of participant aged 15–24 (OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.40, 0.77) were less likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those aged 25–44; by fixed effect with I2 = 6% and P = 0.0005 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Forest plot of association between IPPIUCD uses and age category in Ethiopia, 2021.

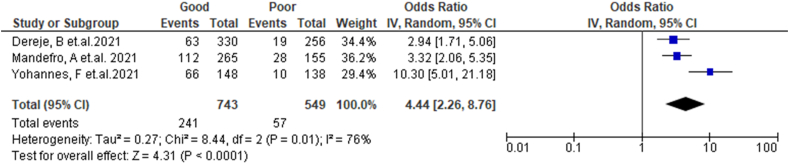

Three studies [19, 35, 36] included in this meta-regression showed that knowledge was positively associated with IPPIUCD use. Those who had good knowledge were 4.44 times (OR = 4.44, 95% CI: 2.26, 8.76) more likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those who had poor knowledge. Random effect model was used with I2 value of 76% and P = 0.0001 (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Forest plot of association between IPPIUCD uses and level of knowledge in Ethiopia, 2021.

4. Discussion

The immediate postpartal period is a unique time for interventions to offer IUCD method [42]. High 6 month continuation rates and a small rate of bad outcomes shows IPPIUCD placement is a feasible and acceptable postpartum contraceptive option for women living in Ethiopia [43]. There has been higher need in the placement of long-acting reversible contraceptives in Ethiopia at or immediately after delivery, without considering delivery type. There are number of primary studies on IPPIUCD in Ethiopia, but there is no systematic review or meta-analysis. There for this study will address country level IPPIUCD use.

This systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the pooled IPPIUCD use in Ethiopia was 8.37 (95% CI: 4.32, 16.21). Similar figure of (16%) IPPIUCD use was reported by studies conducted in Uganda [44] and Washington [45]. The current study figure is lower than studies conducted in Rwanda 45% IPPIUCD use [46], in Cameroon 22% IPPIUCD use [47], in India 28.9% IPPIUCD use, in Georgia 29.7% IPPIUCD use [48]. This might be due to cultural and religious differences between the countries. Other possible reason might be the time of initiating IPPIUCD on those countries; since early initiated countries might have higher magnitudes.

This review had implied that those who were in age 15–24 were less likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those aged 25–44. Similarly a study conducted in Bangladesh showed that most of the participant accepted to use IPPICD were belonged to the age above 25 years compared to those aged below or equal to 24 years [49]. This might be due to most of women aged above 25 years were either married or engaged in sexual activities, there for they need to pay attention to methods preventing pregnancy next pregnancy [44]. In the other hand it might be due to expected number of births were attained in the age 25 year.

In this review those who ever heard about IPPIUCD were more likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those who never heard. Consistently a study conducted in Uganda showed that participants who had informed well in the community were more likely to use IPPIUCD [44]. Similarly a study conducted by USAID states that those who had good information were more likely to use IPPIUCD [50]. This might be due to those who had acquired enough information could decide upon themselves to use IPPIUCD. Beside this they might decide to use it because they have heard the information about the device from satisfied user or heard from those who had appropriate knowledge on the method like health professionals.

This review and meta-analysis showed that, those who had good knowledge level were more likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those who had poor level of knowledge on IPPIUCD. Consistently a scholar from Uganda states that there is generally a knowledge gap about IUCD and specifically on IPPIUCD which could be attributed to low awareness and utilization [44]. In the same fashion a study conducted in Zambia reported that those who had poor knowledge on pregnancy exposure had less likely to use IPPIUCD [50]. This might due to knowledgeable clients had informed choice on the method to be used in parallel with other procedure like delivery and laparotomy without other appoint for hospital visit. In the other hand since they were knowledgeable about the method they might decide to be prevented from pregnancy immediately after delivery.

This study reports those who had birth interval greater than 3 years were more likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those who had birth interval less than 3 years. In the same manner a study conducted in India showed that higher parity women were more likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those who had lower parity [51]. This might be due to need for extending year of next birth using LARC. As it had been indicated in this review they had 3 or more years of interval most likely due to using contraceptives like IPPIUCD otherwise they could have pregnancy before the stated number of years.

In this study counseled participants about IPPIUCD were more likely to use IPPIUCD compared to those who had never counseled. Consistently a study conducted on middle and low resource setting conclude that counseling can overcome gaps in delivery of IPPIUCD [52]. In the same fashion American college of obstetrician and gynecology committee recommends that a due emphasis should be given to counseling to have effective IPPIUCD delivery [8]. In addition to this a study found that there was an improvement in IPPIUCD uptake that had resulted from the intensified counseling [44]. This might be due to women need to be counseled about IPPIUCD in a context that allows informed decision making.

5. Strength and limitation

This systematic review and meta-analysis brings summative report of all primary studies conducted in Ethiopia on IPPIUCD. All variables available in each article were assessed for significance in the pooled effect. Pooled uses of IPPIUCD were obtained and Pooled significant variables were identified. But this systematic review might not be generalized to all regions in Ethiopia. Because the available primary studies were conducted in some of the regions of Ethiopia.

6. Conclusion and recommendation

The pooled use of IPPIUCD in Ethiopia was low compared to studies conducted in other countries. This systematic review and meta-analysis implied that the pooled statistically significant variables to use IPPIUCD were age category, ever heard about IPPIUCD, level of knowledge, birth interval and being counseled about IPPIUCD.

Health care workers working on family planning unit and postpartum unit in Ethiopia need to counsel those mothers who were aged less than 25 years during offering IPPIUCD. Besides this each client either in the delivery room or in the postpartum care unit needs to be counseled about IPPICD by trained professionals. Women who had short birth interval needs health education and information on IPPIUCD, during each contact to the hospitals by health professionals.

Declaration

Author contribution statement

Yohannes Fikadu Geda; Tamitat Melis Berhe: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

Authors of the primary research used on this systematic review and meta-analysis never need to be missed from acknowledgment.

References

- 1.Peterson S.F., Goldthwaite L.M. Postabortion and postpartum intrauterine device provision for adolescents and young adults. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2019;32(5):S30–S35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.05.012. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1083318819302098 [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deshpande D.S.A. Evaluation of safety, efficacy and continuation rates of postpartum intrauterine contraceptive devices (PPIUCD) (Cu-T 380 A) J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. 2018;6(7):1047–1052. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puri M.C., Joshi S., Khadka A., Pearson E., Dhungel Y., Shah I.H. Exploring reasons for discontinuing use of immediate post-partum intrauterine device in Nepal: a qualitative study. Reprod. Health. 2020;17(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-0892-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lakhani S., Cullen J., Ali S.M. Systematic review of educational interventions to improve the uptake of post-partum intrauterine contraceptive device (Ppiucd) Pak. J. Public Health. 2018;7(4):226–231. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dasanayake D.L.W., Patabendige M., Amarasinghe Y. Single center experience on implementation of the postpartum intrauterine device (PPIUD) in Sri Lanka: a retrospective study. BMC Res. Notes. 2020;13(1):4–9. doi: 10.1186/s13104-020-05045-x. [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearson E., Senderowicz L., Pradhan E., Francis J., Muganyizi P., Shah I., et al. Effect of a postpartum family planning intervention on postpartum intrauterine device counseling and choice: evidence from a cluster-randomized trial in Tanzania. BMC Wom. Health. 2020;20(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-00956-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper M., McGeechan K., Glasier A., Coutts S., McGuire F., Harden J., et al. Provision of immediate postpartum intrauterine contraception after vaginal birth within a public maternity setting: health services research evaluation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020;99(5):598–607. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reversible IPL Committee opinion. Am. Coll. Obstet. Gynecol. Women’s Heal. Care Physician. 2016;(670) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasim T., Shaukat S., Javed L., Mukhtar S. Outcome of immediate postpartum insertion of intrauterine contraceptive device: experience at tertiary care hospital. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2018;68(4):519–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makins A., Arulkumaran S. Institutionalization of postpartum intrauterine devices. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018;143:1–3. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Access O., Placental P., Contraceptive I., Insertion D., Article O., Armed P., et al. Vol. 69. 2019. Post placental intrauterine contraceptive device insertion; pp. 1115–1119. (5) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asnake M., Belayihun B., Tilahun Y., Zerihun H., Tasissa A. Leveraging maternity waiting homes to increase the uptake of immediate postpartum family planning in primary health care facilities in Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Heal. Dev. An. 2021;(12) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eva G., Gold J., Makins A., Bright S., Dean K., Tunnacliffe E. Economic evaluation of provision of postpartum intrauterine device services in Bangladesh and Tanzania. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2021;9(1):107–122. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robert M., Msuya S.E., Mahande M.J. Initiation of postpartum modern contraceptive methods : evidence from Tanzania demographic and health survey. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abebe T.W., Mannekulih E. 2020. Focused Family Planning Counseling Increases Immediate Postpartum Intrauterine Contraceptive Device Uptake: A Quasi-Experimental Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran N.T., Seuc A., Tshikaya B., Mutuale M., Landoulsi S., Kini B., et al. Articles Effectiveness of post-partum family planning interventions on contraceptive use and method mix at 1 year after childbirth in Kinshasa , DR Congo (Yam Daabo): a single-blind, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8:399–410. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30546-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Husain S., Husain S., Izhar R. Women ’ s decision versus couples ’ decision on using postpartum intra-uterine contraceptives. EMHJ. 2019;25(5) doi: 10.26719/emhj.18.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Divakar H., Bhardwaj A., Narhari C., Thelma P., Pooja S. Critical factors influencing the acceptability of post - placental insertion of intrauterine contraceptive device : a study in six public/Private Institutes in India. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India. 2019;69(4):344–349. doi: 10.1007/s13224-019-01221-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geda Y.F., Nejaga S.M., Belete M.A., Lemlem S.B. Immediate postpartum intrauterine contraceptive device utilization and influencing factors in Addis Ababa public hospitals : a cross-sectional study. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2021;7(4):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40834-021-00148-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jnr M.G., Alemayehu A., Yihune Manaye, Dessu Samuel, Tamirat Melis N.N. Acceptability and factors associated with immediate postpartum intrauterine contraceptive device use among women who gave birth at Government hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2019. Open Access J. Contracept. 2021;12:93–101. doi: 10.2147/OAJC.S291749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jima G.H., Garbaba W.B. Postpartum family planning utilization and associated factors among women who gave birth in the last 12 Months prior to the study in Lode Hetosa District, South East Ethiopia. J. Women's Health Care. 2020;9:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagos H., Tiruneh D., Necho W., Biru S. Postpartum intra-uterine contraceptive device utilization among mothers who delivered at debre tabor general hospital : cross sectional study design. Int. J. Fam. Community Med. 2020;4(5) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fikadu Geda Y., Siyoum M., Tirfie W.A. Vol. 2020. 2020. Pregnancy History and Associated Factors Among Hawassa University Regular Undergraduate Female Students, Southern Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geda Y. Determinants of teenage pregnancy in Ethiopia: a case–control study, 2019. Curr. Med. Issues. 2019;17(4):112. [Google Scholar]

- 25.CSA. Ethiopia Mini DHS. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melkie A., Addisu D., Mekie M., Dagnew E. Utilization of immediate postpartum intrauterine contraceptive device and associated factors among mothers who gave birth at selected hospitals in. Heliyon. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CSA, UNICEF E . MOH; 2016. Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonie A., Worku C., Assefa T., Bogale D., Girma A. Acceptability and factors associated with post-partum IUCD use among women who gave birth at bale zone health facilities, Southeast-Ethiopia. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2018;3(1) doi: 10.1186/s40834-018-0071-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahu D., Tripathi U. Outcome of immediate postpartum insertion of IUCD - a prospective study. Ind. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Res. 2018;5(4):511–515. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper M., Cameron S. Successful implementation of immediate postpartum intrauterine contraception services in Edinburgh and framework for wider dissemination. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018;143:56–61. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Caestecker L., Banks L., Bell E., Sethi M., Arulkumaran S. Planning and implementation of a FIGO postpartum intrauterine device initiative in six countries. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018;143:4–12. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper M., Boydell N., Heller R., Cameron S. Community sexual health providers’ views on immediate postpartum provision of intrauterine contraception. BMJ Sex Reprod. Heal. 2018;44(2):97–102. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2017-101905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;2535:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melkie A., Addisu D., Mekie M., Dagnew E. Utilization of immediate postpartum intrauterine contraceptive device and associated factors among mothers who gave birth at selected hospitals in west Gojjam zone, Ethiopia, multi ... Heliyon Utilization of Immediate Postpartum Intrauterine Contraceptive Device and Associated Factors Among Mothers Who Gave Birth at Selected Hospitals in West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia , Multi-Level Facility-Based Study, 2019. Heliyon. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Assefaw M., Azanew G., Engida A., Tefera Z., Gashaw W. Determinants of postpartum intrauterine contraceptive device uptake among women delivering in public hospitals of South Gondar zone, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019: an unmatched case-control study. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. Volu. 2021:2021. doi: 10.1155/2021/1757401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Demissie D.B. Immediate postpartum modern family planning utilization and associated factors among women gave birth public health facilities , Addis Ababa. Res. Sq. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melkie A., Addisu D., Mekie M., Dagnew E. Heliyon Utilization of immediate postpartum intrauterine contraceptive device and associated factors among mothers who gave birth at selected hospitals in. Heliyon. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagos H., Tiruneh D., Necho W., Biru S. Postpartum intra-uterine contraceptive device utilization among mothers who delivered at debre tabor general hospital : cross sectional study design. Int. J. Fam. Community Med. 2020;4(5) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seid Jemal Mohammed W.G.K., Yesera, Endashaw Gesila, Shegaze Mulugeta, Kamknm Shimbre, Yesgat Y.M. Determinants of postpartum IUCD utilization among mothers who gave birth in Gamo zone public health facilities , Southern Ethiopia : a case-control study. Open Access J. Contracept. 2020;11:125–133. doi: 10.2147/OAJC.S257762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tefera L.B., Abera M., Fikru C., Tesfaye D.J. Utilization of immediate post-partum intra uterine contraceptive device and associated factors : a Facility based cross sectional study among mothers delivered at public health Faci ... Journal of pregnancy and child utilization of immediate post-partum I. J. Pregn. Child Health. 2017;4(3) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higgins J.P.T.S. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002;15(21):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harrison M.S., Goldenberg R.L. Immediate postpartum use of long-acting reversible contraceptives in low- and middle-income countries. Harrison Goldenb Matern. Health Neonatol. Perinatol. 2017;3(24):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40748-017-0063-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marchin A., Moss A., Harrison M., Marchin C.A., Moss A., Harrison M., et al. A meta-analysis of postpartum Copper IUD continuation rates in low- and middle-income countries. J. Wom. Health. 2021;4(1):36–46. doi: 10.26502/fjwhd.2644-28840059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Medicine C. Factors influencing utilization of intra-uterine device among postpartum mothers at Gombe Factors influencing utilization of intra-uterine device among postpartum mothers at Gombe Hospital , Butambala disrtict , Uganda. Cogent. Med. 2020;7(1) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lerma K., Bhamrah R., Singh S., Blumenthal P.D. Importance of the delivery – insertion interval in immediate postpartum intrauterine device insertion : a secondary analysis. Obstetrics. 2020:154–159. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13115. August 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Survival C. 2018. Scaling up Immediate Postpartum Family Planning Services in Rwanda. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Planning F. 2016. Advancing Postpartum Family Planning Promotion and Service Delivery Among Youth in Cameroon Overview of E2A Postpartum Family. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berry-bibee E., Jamieson D.J., Marchbanks P.A. HHS public access. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019;132(4):895–905. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nahar K.N., Fatima P., Dewan F., Yesmin A., Laila T.R., Begum N., et al. Acceptability and Feasibility of postpartum intra uterine contraceptive device insertion in Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical university, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Bangladesh Med. J. 2019;47(3):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 50.July O., Dc W. 2012. Development I. Postpartum Family Planning New Research Findings and Program Implications. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valliappan A., Dorairajan G., Chinnakali P. 2017. Postpartum Intrauterine Contraceptive Device: Knowledge and Factors Affecting Acceptance Among Pregnant/Parturient Women Attending a Large Tertiary Health Center in Puducherry, India. 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Providers M.C. 2016. Improving Quality of Postpartum Family Planning in Low-Resource Settings. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.