Abstract

Translational stop codon readthrough provides a regulatory mechanism of gene expression that is extensively utilised by positive-sense ssRNA viruses. The misreading of termination codons is achieved by a variety of naturally occurring suppressor tRNAs whose structure and function is the subject of this survey. All of the nonsense suppressors characterised to date (with the exception of selenocysteine tRNA) are normal cellular tRNAs that are primarily needed for reading their cognate sense codons. As a consequence, recognition of stop codons by natural suppressor tRNAs necessitates unconventional base pairings in anticodon–codon interactions. A number of intrinsic features of the suppressor tRNA contributes to the ability to read non-cognate codons. Apart from anticodon–codon affinity, the extent of base modifications within or 3′ of the anticodon may up- or down-regulate the efficiency of suppression. In order to out-compete the polypeptide chain release factor an absolute prerequisite for the action of natural suppressor tRNAs is a suitable nucleotide context, preferentially at the 3′ side of the suppressed stop codon. Three major types of viral readthrough sites, based on similar sequences neighbouring the leaky stop codon, can be defined. It is discussed that not only RNA viruses, but also the eukaryotic host organism might gain some profit from cellular suppressor tRNAs.

INTRODUCTION

Regulation of gene expression is found at different stages, one of which operates at the level of termination in protein synthesis. Normally, termination of mRNA translation is signalled by the occurrence of any of the three nonsense (stop) codons UAG, UAA or UGA at the ribosomal A site. Protein release factors specifically bind to these codons (for which cognate tRNAs are not available) and subsequently mediate release of the nascent polypeptide chain from the ribosome. However, there are several processes known that can circumvent nonsense codons, for example ribosomal frameshifting and suppression by either mutated or natural cellular tRNAs. In the case of frameshifting, the reading frame is shifted in the 5′ or 3′ direction and as a consequence the suppressed stop codon is read as a sense codon (1–3). Mutated suppressor tRNAs carry an altered anticodon allowing the tRNA to misread a stop codon by normal base pair interactions. A bulk of chemically induced nonsense suppressors have been isolated in the past from Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae and employed in genetic and biochemical studies, but will not be the subject of this article.

Natural nonsense suppression, however, means the reading of stop codons as sense codons by normal cellular tRNAs which are called natural suppressors. This review describes primarily the structure and function of such tRNAs—with the exception of selenocysteine tRNA—in higher eukaryotes. It does not cover missense (i.e. the reading of sense codons by non-cognate tRNAs) and nonsense suppression in bacteria for which excellent reviews exist (4–6). Furthermore, this article deals with codon context effects, i.e. primary sequences and secondary structures in the vicinity of ‘leaky’ stop codons that influence the efficiency of suppression. A number of recent reports describing related topics are recommended to the reader (7–13).

IDENTIFICATION OF STOP CODON READTHROUGH

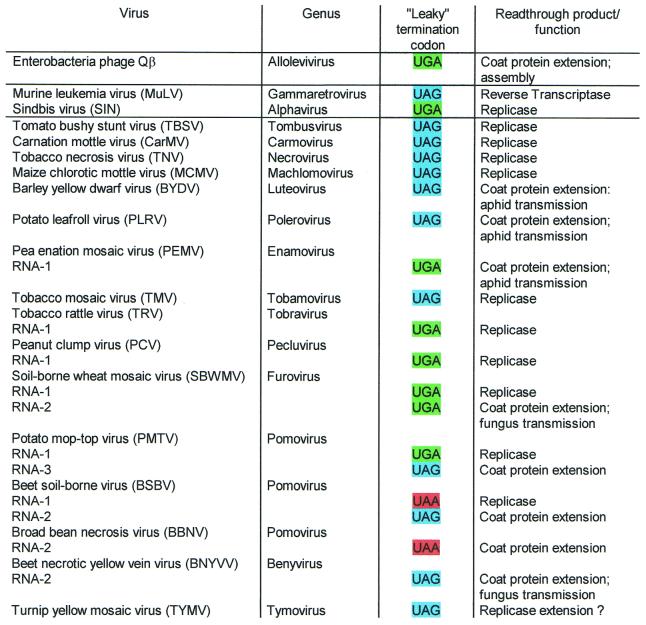

Translational readthrough provides a regulatory mechanism of gene expression by permitting the differential production of more than one polypeptide from a single gene. Notably, RNA viruses make use of this potential to expand the genetic information of their relatively small genomes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Suppressible termination codons in positive sense ssRNA viruses, representing mostly type species from the corresponding genus. The classification of viruses is according to Pringle (104). Detailed information about sequences and function of readthrough products is listed in the legends to Figures 13 and 14.

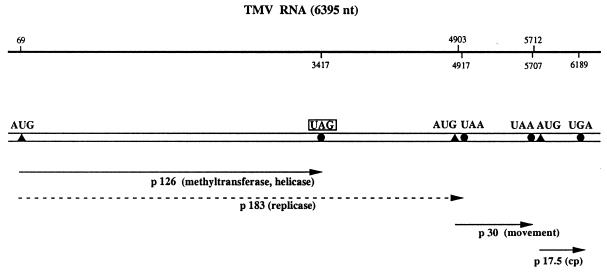

The first type of stop codon readthrough was detected in E.coli infected with RNA phage Qβ. It was shown that normal tRNATrp with CCA anticodon stimulates readthrough over the UGA stop codon at the end of the coat protein cistron, resulting in an elongated coat protein that is essential for the formation of infective Qβ particles (14–16). It took more than a decade to detect natural suppressor tRNAs also in eukaryotic cells. Pelham (17) postulated the presence and ‘leakiness’ of a UAG codon at the end of the 126 kDa cistron in tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) RNA (Fig. 2), since he found stimulation of the in vitro synthesis of the 183 kDa readthrough protein in the presence of yeast amber suppressor tRNA. The elucidation of the complete TMV RNA sequence confirmed the existence of an internal UAG stop codon (18). Moreover, the observation that the 183 kDa polypeptide was synthesised in TMV-infected tobacco protoplasts and tobacco leaves (19,20) supported the notion that the ‘leaky’ UAG codon is very likely suppressed by a cellular tobacco tRNA. The 126 kDa protein contains a putative methyltransferase and a helicase domain, whereas the 183 kDa readthrough product harbours the highly conserved GDD motif, responsible for replicase activity (10). Both polypeptides are essential for TMV multiplication (21).

Figure 2.

Schematic structure of TMV RNA. The 6.4 kb genomic ssRNA of TMV (18) is designated by a double horizontal line. The upper line indicates the locations of ORFs as determined from the sequence. The positions of initiation and termination codons are specified by closed triangles and circles, respectively. The proteins synthesised in vivo are shown as single lines with arrowheads, the 183 kDa readthrough product is indicated by a broken line. The ‘leaky’ UAG stop codon at the end of the 126 kDa cistron is boxed.

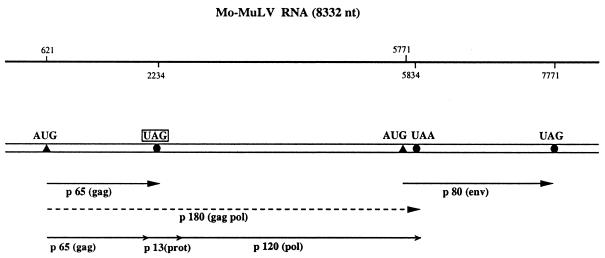

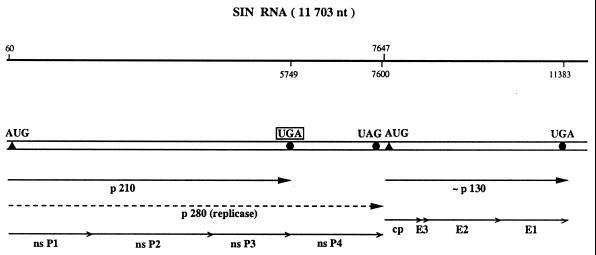

The second well-known example for translational readthrough is found upon expression of the murine leukemia virus (MuLV) RNA in animal tissue. In MuLV-infected mouse cells the in-frame UAG stop codon at the end of the gag cistron is suppressed to yield a gag–pol fusion polypeptide of 180 kDa, which is subsequently cleaved into the gag protein, a protease of 13 kDa and the reverse transcriptase (Fig. 3). Thus, the readthrough product is the only source of reverse transcriptase, and consequently UAG suppression is necessary for normal multiplication of MuLV. Yoshinaka et al. (22) showed that the protease that overlaps the readthrough region contains glutamine inserted at the site of the UAG codon, indicating that a cellular tRNAGln acts as a UAG suppressor. Many (but not all) members of the alphavirus genus contain a ‘leaky’ UGA stop codon within their genomic RNA separating the non-structural proteins nsP3 and nsP4 (Fig. 4). The nsP4 protein shares homologous amino acid sequences with the RNA-dependent RNA replicase of poliovirus and plant RNA viruses, and is supposed to contain the elongating activity of the sindbis virus replicase (23).

Figure 3.

Schematic structure of Mo-MuLV RNA. The 8.3 kb genomic ssRNA of Mo-MuLV (105) is represented by a double line. The positions of initiation and termination codons are indicated by closed triangles and circles, respectively. The ‘leaky’ UAG codon is boxed. The two primary polypeptides of 65 and 80 kDa are indicated by single lines. The gag/pol readthrough product of 180 kDa is shown as a broken line. This polypeptide is subsequently cleaved into the gag protein, a protease of 13 kDa and the reverse transcriptase of 120 kDa.

Figure 4.

Schematic structure of sindbis virus (SIN) RNA. The 11.7 kb genomic ssRNA of SIN (106) is represented by a double line. The positions of initiation and termination codons are specified by closed triangles and circles, respectively. The translation of SIN non-structural (ns) proteins starts from the AUG codon at the beginning of nsP1 and proceeds to the UGA at the end of the nsP3 cistron. Partial readthrough of this ‘leaky’ stop codon yields the polypeptide of 280 kDa which is subsequently processed by proteolytic cleavage to produce the non-structural proteins nsP1 to nsP4.

Besides TMV, a bulk of plant RNA viruses from at least 14 groups utilise stop codon readthrough to generate either a functional polymerase or an extended coat protein. The latter is important for the assembly of the virion and/or vector transmission. Of all known ‘leaky’ stop codons, UAA is by far the least frequently used. Some of the multicomponent viruses, such as beet soil-borne virus and potato mop-top virus contain diverse ‘leaky’ stop codons on different RNA species (Fig. 1).

To date, very few DNA viruses are known that employ nonsense suppression as a means of regulating gene expression. For instance, the 58 kDa virion protein of the human cytomegalovirus may be synthesised via translational readthrough of a UGA termination codon separating two open reading frames on the 1.6 kb late mRNA (24).

As mentioned above, the readthrough polypeptides have been shown in many cases to be essential for virus production. Furthermore, the ratio of the two synthesised products appears to be critical. Thus, the substitution of the ‘leaky’ UAG by a CAG glutamine codon in MuLV-RNA resulted in the inability to produce virus (25,26). An unbalanced synthesis of the 126 and 183 kDa polypeptides in TMV-infected tobacco plants also caused a low yield of progeny (21).

UAG/UAA SUPPRESSORS

Cytoplasmic tRNATyr

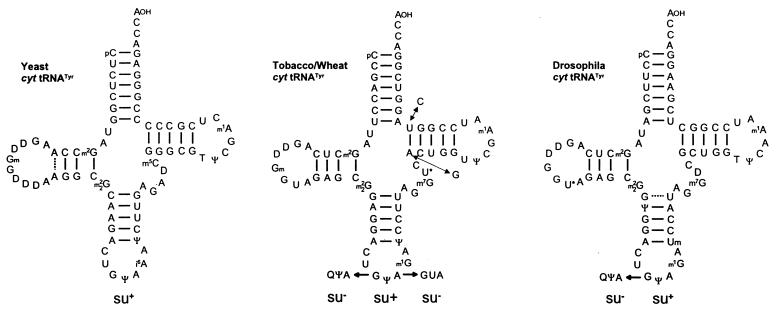

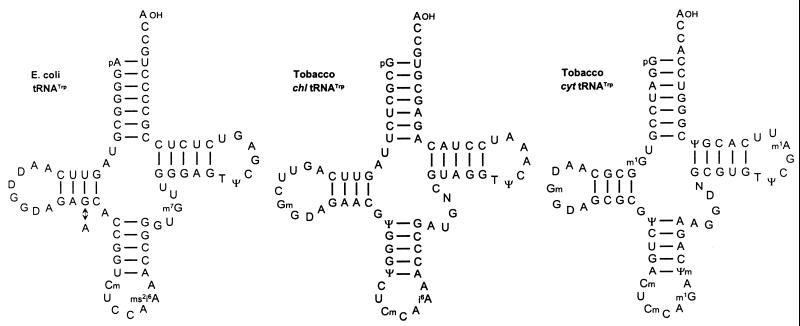

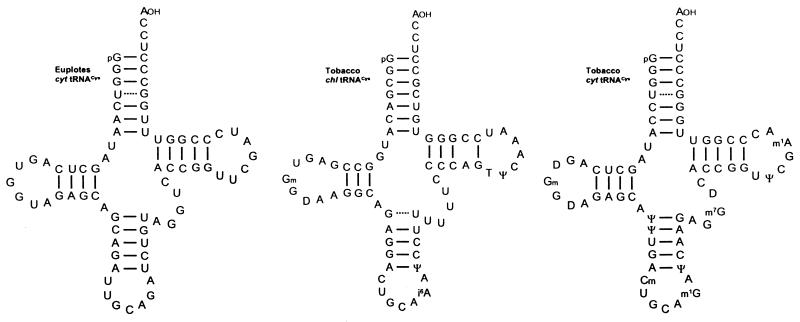

The first eukaryotic natural UAG suppressor tRNA was isolated from tobacco leaves and adult Drosophila on the basis of its ability to promote readthrough over the ‘leaky’ UAG codon of TMV RNA in a messenger-dependent reticulocyte lysate and in Xenopus oocytes, respectively (19,27). The highly purified suppressor tRNA was sequenced by the fragment analysis of partially digested tRNA according to Stanley and Vassilenko (28). Its amino acid acceptance and anticodon sequence identified the UAG suppressor as cytoplasmic tRNATyr with a GΨA anticodon (Fig. 5). Tobacco and wheat leaves contain only tRNATyr isoacceptors with a GΨA anticodon, whereas ∼85% of the tRNATyr species from wheat germ and lupin seeds have a QΨA anticodon (29–31). Interestingly, tRNATyr with a QΨA anticodon is totally unable to stimulate UAG readthrough (27,29,32). The highly modified Q nucleoside is synthesised as the free queuosine base (Q), which is then inserted into tRNA by a transglycosylase to replace guanine (33). Bacterial tRNAs are normally completely modified with respect to Q, whereas yeast is totally lacking Q-containing tRNAs (34). Yeast tRNATyr with a GΨA anticodon is likewise able to suppress the TMV-specific UAG codon in vitro (H.Beier, unpublished result) although its nucleotide sequence differs considerably from plant and animal tRNAsTyr (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Nucleotide sequences of cytoplasmic (cyt) tRNAsTyr from S.cerevisiae (34), Nicotiana rustica (19), wheat germ (29) and Drosophila melanogaster (107). The tRNATyr isoacceptors with GΨA anticodon have been shown to be active UAG suppressors in vitro, whereas the corresponding species with a GUA or QΨA anticodon are unable to misread this stop codon (19,27,29,39). U* (in position 20:A of Drosophila and 47 of plant tRNATyr), acp3U; m1G, 1-methylguanosine; m2G, N2-methylguanosine; m22G, N2,N2-dimethylguanosine; m7G, 7-methylguanosine; m1A, 1-methyladenosine; m5C, 5-methylcytidine; Ψ, pseudouridine; T, ribosylthymine; Q, queuosine; D, dihydrouridine; Gm, 2′-O-methylguanosine; Um, 2′-O-methyluridine.

Animal tRNAs exhibit a variable Q content depending on the developmental state. In differentiated liver only tRNATyr with QΨA anticodon is present (35), but fetal liver, reticulocytes and tumour tissue contain significant amounts of tRNAs with G in place of Q in the first position of the anticodon (36,37). Adult Drosophila possess tRNATyr isoacceptors with GΨA and a QΨA anticodon (27), and relevant changes in the Q content in tRNAs isolated from different ontogenetic stages of Drosophila have been observed (38).

Another interesting attribute of tRNATyr is the pseudouridine (Ψ35) at the second position of the anticodon, a unique feature of all eukaryotic cytoplasmic tRNAsTyr. An in vitro synthesised tRNATyr with GUA instead of GΨA anticodon was unable to suppress the ‘leaky’ UAG codon of TMV RNA (39), indicating that the Ψ35 modification in the tRNATyr anticodon is necessary for the unconventional codon reading. Pseudouridine can form a classical base pair with adenosine, but is more versatile in its hydrogen bonding interactions, possibly resulting in stabilisation of codon–anticodon interactions (40). Hence, there is a remarkable influence of base modifications on UAG suppression. The presence of the hypermodified Q at the first anticodon position of tRNATyr prevents, whereas Ψ at the second anticodon position enhances, the unconventional base pairing (Fig. 5).

Plant cytoplasmic tRNATyr with a GΨA anticodon is quite an efficient UAG suppressor. Under optimal conditions 10–30% of readthrough over the TMV-specific ‘leaky’ UAG are observed in vitro (19,39,41). The same tRNATyr is able to read UAA, but not the UGA stop codon, albeit with lower efficiency (39). Although tRNATyr(GΨA) is a very potent UAG suppressor in vitro, and very likely also in vivo, it cannot be regarded as a universal suppressor because of its limited presence in various tissues as outlined above.

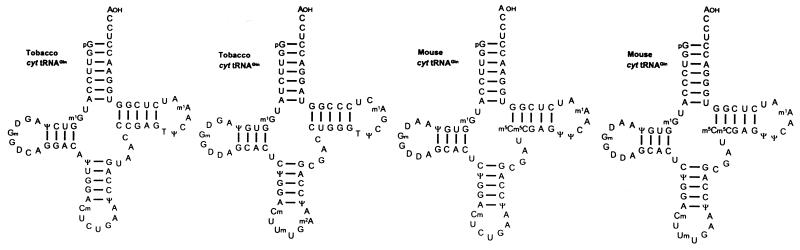

Cytoplasmic tRNAsGln

The second class of eukaryotic UAG/UAA suppressors are cytoplasmic tRNAsGln. Two isoacceptors with a CUG or U*UG anticodon exist virtually in all pro- and eukaryotes (34). A number of observations had implied their putative ability to read UAG and/or UAA codons. For instance, in the yeast S.cerevisiae, transformation with high copy numbers of a tRNAGln isoacceptor with a CUG anticodon resulted in the suppression of a number of UAG mutations in the yeast genome (42–44). Likewise, Pure et al. (45) reported that overexpression of yeast tRNAGln with a UUG anticodon weakly suppressed internal UAA codons. Furthermore, glutamine is inserted at the site of the ‘leaky’ UAG codon in MuLV RNA (22).

Two cytoplasmic tRNAGln isoacceptors were isolated from mouse liver and tobacco leaves, and their sequences were determined (Fig. 6). The minor tRNAGln species from mouse liver with a UmUG anticodon was shown to stimulate readthrough over the ‘leaky’ UAG codon in TMV RNA in a reticulocyte lysate (46). Noticeably, the amount of this suppressor tRNAGln was greatly increased in NIH3T3 and Ehrlich ascites cells infected with Mo-MuLV, as reported by Kuchino et al. (46). In contrast, Feng et al. (47) observed equivalent amounts of the two tRNAGln isoacceptors in MuLV-infected and uninfected NIH3T3 cells. The reasons for this discrepancy are unknown.

Figure 6.

Nucleotide sequences of cytoplasmic (cyt) tRNAsGln from N.rustica (48) and mouse liver (46). All of these tRNAGln isoacceptors suppress either the UAG, UAA or both stop codons in a wheat germ (41,48) and in a reticulocyte lysate, respectively (46). A major tRNAGln with UmUG anticodon from T.thermophila is also a strong UAG/UAA suppressor (41,108). The modified nucleosides not listed in theFigure 5 legend are: m2A, 2-methyladenosine; Cm, 2′-O-methylcytidine.

Both cytoplasmic tRNAGln isoacceptors from tobacco stimulated readthrough over the TMV-specific UAG codon in a wheat germ extract partially depleted of endogenous tRNAs. In this system, Nicotiana tRNAGln with a UmUG anticodon was a less efficient UAG suppressor than tRNAGln with a CUG anticodon (48). One of the major tRNAGln isoacceptors from the unicellular ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila has a UmUG anticodon and comprises a high sequence similarity to its animal and plant counterparts (Fig. 6). This tRNAGln isoacceptor is a very potent UAG and UAA suppressor in wheat germ extract, provided appropriate amounts of a Tetrahymena synthetase preparation are added to the extract (41). Most of the sequenced cellular tRNAGln species carry an unmodified A residue immediately 3′ to the anticodon at position 37 (Fig. 6). Interaction of the two tRNAGln isoacceptors with UAG and/or UAA requires an unconventional G:U base pairing at the third anticodon position (see below). Presumably, an unmodified A adjacent to the anticodon facilitates non-canonical base pairing at the third anticodon position, since a number of reports have conversely shown that a hypermodified A, like i6A (N6-isopentenyladenosine) or ms2i6A (2-methylthio-N6-isopentenyladenosine), impedes non-Watson–Crick interactions at this position (49–51).

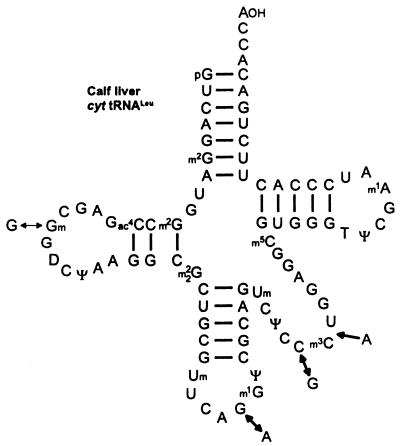

Cytoplasmic tRNAsLeu

Two amber suppressor tRNAs have been isolated from calf liver that read the ‘leaky’ UAG codon of TMV RNA and RNA-2 of beet necrotic yellow vein virus (BNYVV) in a messenger-dependent reticulocyte lysate (52). They are neither tRNATyr nor tRNAGln species, but tRNALeu isoacceptors of cytoplasmic origin with CAA and CAG anticodon (Fig. 7). The recognition of the UAG codon by these suppressors requires an unusual A:A pairing in the second, and also a G:U pairing in the third, position of the anticodon. It is not known whether the corresponding plant tRNALeu isoacceptors also comprise UAG suppressor activity in vitro.

Figure 7.

Nucleotide sequences of cytoplasmic (cyt) tRNAsLeu from calf liver (52). The two tRNALeu isoacceptors have been shown to misread the TMV-specific ‘leaky’ UAG codon in a reticulocyte lysate. The modified nucleoside not listed in the Figure 5 legend is m3C, 3-methylcytidine.

UGA SUPPRESSORS

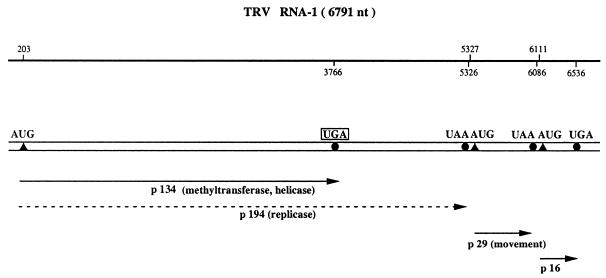

Chloroplast and cytoplasmic tRNAsTrp

Readthrough over the ‘leaky’ UAG in TMV RNA was employed for the characterisation of virtually all eukaryotic UAG suppressors described above. In order to identify UGA suppressors, a second plant RNA virus was utilised in most cases. The tobravirus, tobacco rattle virus (TRV), has a bipartite genome. RNA-1 molecules contain the genetic information needed for RNA replication and intercellular movement, whereas RNA-2 specifies the coat protein. In vitro and in vivo translation studies have demonstrated that RNA-1 directs the synthesis of two polypeptides of 134 and 194 kDa (53). Expression of the 194 kDa replicase protein requires readthrough over a ‘leaky’ UGA stop codon at the end of the 134 kDa cistron (Fig. 8)

Figure 8.

Schematic structure of TRV RNA-1. The 6.8 kb genomic ssRNA-1 of TRV (109) is designated by a double horizontal line. The positions of initiation and termination codons are indicated by closed triangles and circles, respectively. The first ORF codes for a non-structural protein of 134 kDa that is terminated by a UGA codon. Partial readthrough of this ‘leaky’ UGA stop codon yields the 194 kDa polypeptide (broken line).

Two natural UGA suppressors were isolated from uninfected tobacco plants on the basis of their ability to promote readthrough over the ‘leaky’ UGA codon in TRV RNA-1 in a wheat germ extract (54). Their amino acid acceptance and nucleotide sequences identified the two UGA suppressors as chloroplast and cytoplasmic tryptophan-specific tRNAs with the anticodon CmCA (Fig. 9). Unexpectedly, it was found that chloroplast tRNATrp suppresses the UGA codon more efficiently than cytoplasmic tRNATrp. It has been speculated that structural features and/or base modifications of the former contribute to higher suppression. Thus, a mutant strain from E.coli with increased UGA suppressor activity turned out to contain a tRNATrp species with an unaltered anticodon, but a single nucleotide exchange at position 24 leading to an A24:U11 instead of a G24:U11 base pair in the D-stem (14; Fig. 9). Presumably, the mutation at position 24 reduces the rate at which the ribosome rejects non-cognate tRNAs, more easily permitting unconventional base pairing (55,56). The chloroplast tRNATrp from tobacco contains the same A24:U11 base pair as the mutated E.coli tRNATrp, whereas cytoplasmic tRNATrp has a G:C pair at this postion (Fig. 9). It should be noted, however, that it is not known whether eukaryotic ribosomes express similar constraints. Another difference between the two tRNATrp isoacceptors lies in the nature of the modified nucleoside at position 37. Chloroplast tRNATrp carries i6A or ms2i6A, whereas cytoplasmic tRNATrp has a m1G (1-methylguanosine) at this position. It has been proposed that i6A and its derivatives stabilise anticodon–codon interactions by increasing the stacking effect of the anticodon on neighbouring nucleotides, thus supporting non-canonical base interactions at the first anticodon position (57,58).

Figure 9.

Nucleotide sequences of chloroplast (chl) and cytoplasmic (cyt) tRNAsTrp from N.rustica.. The two tRNATrp isoacceptors promote UGA readthrough preferentially in the TRV-specific codon context in wheat germ extract (54,88). For comparison, the sequences of wild-type tRNATrp from E.coli and a mutated derivative are also shown. The mutated tRNATrp contains a single nucleotide exchange (G→A) at position 24, and exhibits increased UGA suppressor activity as compared to the wild type (14). The modified nucleosides not listed in the Figure 5 legend are: i6A, N6-isopentenyladenosine; ms2i6A, 2-methylthio-N6-isopentenyladenosine; Ψm, 2′-O-methylpseudouridine.

Given the high UGA suppressor activity of chloroplast tRNATrp, the question arises whether fidelity of chloroplast synthesis is impaired. However, close inspection of the 24 protein-coding genes in the Nicotiana chloroplast genome that terminate with a UGA codon, reveals that in ∼50% of the cases the stop codon is flanked at the 3′ side by a second one within 0–3 codons (59) and in other cases it is embedded in an unfavourable codon context (see below), suggesting that deleterious effects are negligible.

Several reports indicate that tRNATrp isoacceptors with UGA suppressor activity are also present in higher vertebrates. A tRNATrp was purified from rabbit reticulocytes and was shown to efficiently suppress the UGA codon at the end of the β-globin gene in vitro (60). However, the sequence of this tRNA was not determined and, thus, the possibility cannot be ruled out that the suppressor was in fact mitochondrial tRNATrp with a U*CA anticodon, the only tRNATrp species encoded by the rabbit mitochondrial genome (34), and not cytoplasmic tRNATrp with a CCA anticodon. Furthermore, a tRNATrp with a CmCA anticodon was isolated from avian sarcoma virus virions whose sequence and nucleoside modifications were identical to cytoplasmic tRNATrp of uninfected cells, yet the former was a more active UGA suppressor in vitro as compared to its cellular counterpart (61). The reason for this unusual observation is yet unknown. The authors speculate that two conformations of avian tRNATrp may exist that influence the biological activity of the tRNA.

Chloroplast and cytoplasmic tRNAsCys

A number of observations made the existence of cysteine-accepting UGA suppressors very likely. Feng et al. (62) demonstrated that replacement of the ‘leaky’ UAG by a UGA stop codon in MuLV RNA (Fig. 3) directs the incorporation of cysteine in addition to tryptophan and arginine at the corresponding position of the readthrough product upon translation in a reticulocyte lysate.

Chloroplast and cytoplasmic tRNACys isoacceptors with a GCA anticodon (Fig. 10) were isolated from uninfected tobacco leaves on the basis of aminoacylation assays with [35S]cysteine in the presence of an unfractionated wheat germ aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase preparation. Subsequently, the readthrough activity of the two isoacceptors was studied in wheat germ extract programmed with in vitro synthesised transcripts containing the ‘leaky’ UGA region of TRV RNA-1 (Fig. 8). Chloroplast tRNACys turned out to suppress the UGA in the TRV as well as in the TMV codon context more efficiently than the cytoplasmic counterpart (63), an observation already made for chloroplast tRNATrp (see above). No data are available about putative UGA suppressor activity of cytoplasmic tRNACys from animal cells. However, as deduced from the overall sequence homology of tRNACys gene sequences in the mouse and human genome with the corresponding plant genes (64) it is reasonable to assume that animal tRNAsCys also have the potential to act as UGA suppressors.

Figure 10.

Nucleotide sequences of chloroplast (chl) and cytoplasmic (cyt) tRNAsCys from N.rustica. The two tRNACys isoacceptors promote UGA readthrough in wheat germ extract (63). The sequence of tRNACys from E.octocarinatus has been deduced from the known gene sequence contained within a cloned macronuclear DNA molecule. This tRNACys isoacceptor presumably reads the in-frame UGA codons present in numerous gene-derived mRNAs in Euplotes cells (64).

An interesting situation applies for the unicellular ciliate Euplotes octocarinatus. In this organism deviations from the universal genetic code have been described. The UGA stop codon is translated as cysteine within coding regions and does not function as a termination codon in protein synthesis (65). Presumably, only a single tRNACys isoacceptor exists in Euplotes cells which contains a GCA anticodon like all known tRNAsCys species (64; Fig. 10). Plant tRNAsCys have turned out to be relatively inefficient UGA suppressors in vitro (63). One major argument in favour of a more active UGA-decoding Euplotes tRNACys(GCA) is the existence of a release factor in this organism that has lost the capability to bind to UGA codons (66,67), so that competition between the latter and tRNACys is greatly reduced.

Cytoplasmic tRNAsArg

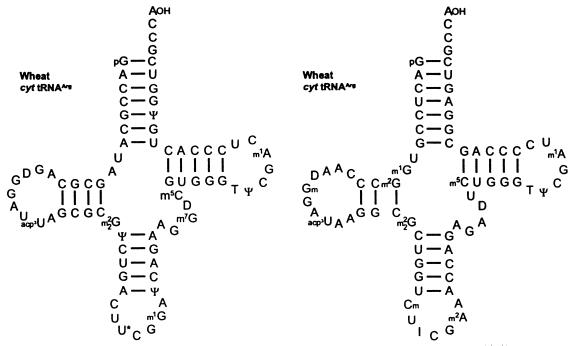

The third class of UGA suppressors has been exclusively characterised in plants on the tRNA level. The six arginine codons CGN and AGR are read by four isoacceptors in E.coli and S.cerevisiae, and by five isoacceptors in the cytosol of higher eukaryotes. Of these five isoacceptors, tRNAArg with a U*CG anticodon is not found in E.coli and yeast (68,69). It is noteworthy that it is just this isoacceptor that is a potent UGA suppressor. The major tRNAArg species have been isolated from wheat germ. In vitro translation of transcripts containing the UGA codon in the context of TRV RNA-1 (Fig. 8) in wheat germ extract in the presence of either of the wheat tRNAArg isoacceptors revealed that mainly tRNAArg with U*CG, and to a lesser extent tRNAArg with ICG anticodon (Fig. 11), stimulated UGA readthrough. Moreover, tRNAArg with a U*CG anticodon was found to also suppress the ‘leaky’ UGA codon in the pea enation mosaic and sindbis virus context (70). Studies of Feng et al. (62) and Chittum et al. (71) indicate that tRNAsArg are also potential UGA suppressors in animals. They identified the amino acid arginine (among others) inserted at the site of UGA in the MuLV-specific context and at the UGA terminating the β-globin cistron upon translation in rabbit reticulocytes in vitro and in vivo

Figure 11.

Nucleotide sequences of cytoplasmic (cyt) tRNAsArg from wheat germ. The tRNAArg with U*CG and to a minor extent tRNAArg with the ICG anticodon promote UGA readthrough preferentially in the PEMV-specific codon context in a wheat germ extract (70). U* (in position 34 of tRNAArg), mcm5U (5-methoxy-carbonylmethyluridine) and/or mcm5s2U (5-methoxy-carbonylmethyl-2-thiouridine); I, inosine.

Sindbis virus RNA contains an in-frame UGA termination codon in the region separating the non-structural proteins nsP3 and nsP4 (Fig. 4). Readthrough over this UGA codon has been observed in cultured cells of chicken, human and insect origin (23). Remarkably, in the closely related semliki forest virus (SFV) there is no UGA, but instead a CGA arginine codon at this position (72), suggesting that possibly the ‘leaky’ UGA in sindbis virus RNA is recognised preferentially by tRNAArg(U*CG), which routinely reads the CGA arginine codon. Li and Rice (73) have presented indirect evidence that tryptophan (and not arginine) is incorporated at the site of the ‘leaky’ UGA in RNA transcripts containing the sindbis virus-specific readthrough region upon in vitro translation in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate. In this connection it should be emphasised that reticulocytes represent a highly specialised type of cells in which the nuclei, and to some extent also the mitochondria, are disintegrated, resulting in the accumulation of mitochondrial tRNATrp with U*CA anticodon in the cytosol. This tRNA isoacceptor utilises normal base interactions to read UGA and consequently may easily out-compete any other natural suppressor.

UNCONVENTIONAL BASE INTERACTONS

Crick (74) had postulated that G:U, U:G and I:C/U/A base pairs at the first anticodon position (also called the ‘wobble’ position) would not affect the fidelity of protein synthesis, due to the degeneracy of the genetic code. Later, some restrictions from this rule were observed in different organisms. For instance, in the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, nonsense suppression has been shown to be strictly codon specific. The ability of ochre suppressors with a U*UA anticodon (where U* is mcm5U or mcm5s2U) to read only UAA and not the UAG stop codon was attributed to the modification present at the first anticodon position, which obviously reduces the interaction with a G residue (75).

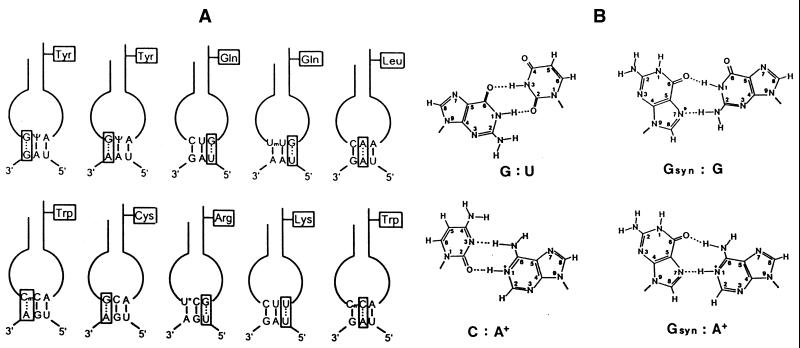

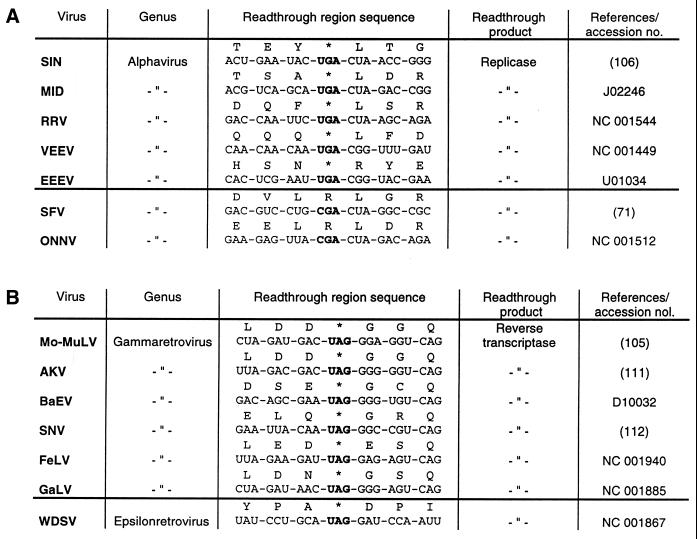

In all types of stop codon recognition by natural suppressor tRNAs non-canonical base pairing occurs mainly at the first or the third anticodon position. Thus, the misreading of UAG or UAA by tRNATyr(GΨA) and of the UGA stop codon by tRNACys(GCA) involves a G:G and G:A base interaction, respectively, whereas the reading of UGA by tRNATrp(CmCA) depends upon a Cm:A mismatch at the same position. On the other hand, G:U base pairs are required at the third anticodon position in the unconventional codon reading by tRNAsGln and tRNAsArg (Fig. 12A). The tRNALeu isoacceptor with a CAA anticodon (Fig. 7) that is capable of suppressing the ‘leaky’ UAG codon of TMV RNA (52) necessitates an unusual A:A interaction at the second anticodon position. A few examples exist in prokaryotes in which unconventional base pairing has been reported in the middle position of the anticodon (76). Strigini and Brickman (77) have shown that E.coli tRNATrp(CCA) misreads in vivo not only UGA (14) but also the UAA codon, requiring two C:A base pairs in the latter case. Likewise, yeast cytoplasmic tRNATrp appears to be able to suppress internal UAG codons in vivo, as demonstrated indirectly by amino acid sequence analysis of the translation product produced by UAG readthrough (78). The comprehensive study by Fearon et al. (78) further revealed that the UAG codon—placed within a favourable nucleotide context within the yeast Ste6 gene—directed not only the incorporation of tyrosine and tryptophan, but also of lysine. Misreading of UAG by tRNALys with a CUU anticodon requires an unorthodox U:U interaction at the third anticodon position (Fig. 12A). Readthrough over UAA and UGA codons—placed at identical sites as the UAG codon—has also been observed in vivo, but the nature of the incorporated amino acids has not been elucidated.

Figure 12.

Unconventional base interactions involved in the misreading of termination codons by natural suppressor tRNAs. (A) Schematic presentation of putative anticodon–codon interactions by eukaryotic suppressor tRNAs. With the exception of tRNALys(CUU) and tRNATrp(CmCA) misreading the UAG codon, all types of non-canonical codon reading by means of an appropriate suppressor tRNA have been demonstrated directly in vitro (19,39,48,52,54,63,70,89). In the case of the two former examples, incorporation of lysine and tryptophan (in addition to tyrosine) has been elucidated by amino acid sequence analysis of the translation protein produced by readthrough of an in-frame UAG codon within the yeast Ste6 gene (78). The tRNAGln isoacceptors with a UmUG anticodon from Tetrahymena, Nicotiana and mouse liver are able to also read UAG besides UAA (41,46,48). (B) Hypothetical interactions between non-complementary bases. In purine–purine mismatches, the nucleoside of the anticodon is presented in the syn configuration (isomerisation about the glycosyl bond of the nucleotide). The space-filling cyclopentene-diol side chain of the queuine base is attached to guanine at the indicated position (*) via a C–C bond, thus impairing the proposed G–G interaction (39). The adenosine in G:A and C:A mismatches is shown in the protonated form.

The mechanism of this unorthodox codon reading is not clear. Based on investigations by Topal and Fresco (79), an increasing number of non-Watson–Crick base pairs have been identified in DNA and RNA helices, some of which were proven by thermodynamic and/or X-ray crystallographic analyses (80–83). Such unconventional base pairs can be formed provided the nucleosides assume minor conformations (syn) and/or minor tautomeric or protonated forms, accompanied often by a slight displacement of the glycosidic bond as in the classical G:U pair (Fig. 12B). Whether these non-Watson–Crick pairs also occur in anticodon–codon interactions remains to be resolved. However, as mentioned above, tRNATyr with the hypermodified nucleoside Q at the first anticodon position does not promote UAG readthrough (27,29,32), emphasising that the guanosine at this position must play a selective role in stop codon suppression (Fig. 12B).

CODON CONTEXT EFFECTS

It has been reported by many groups that translational readthrough of a termination codon is affected by the nucleotide sequences surrounding the ‘leaky’ stop codon in the mRNA of prokaryotic and eukaryotic species (84–86). The codon context can simply consist of only 1–6 nt at the 3′ side of the suppressed stop codon or may involve more complex signals like stem–loop or pseudoknot structures.

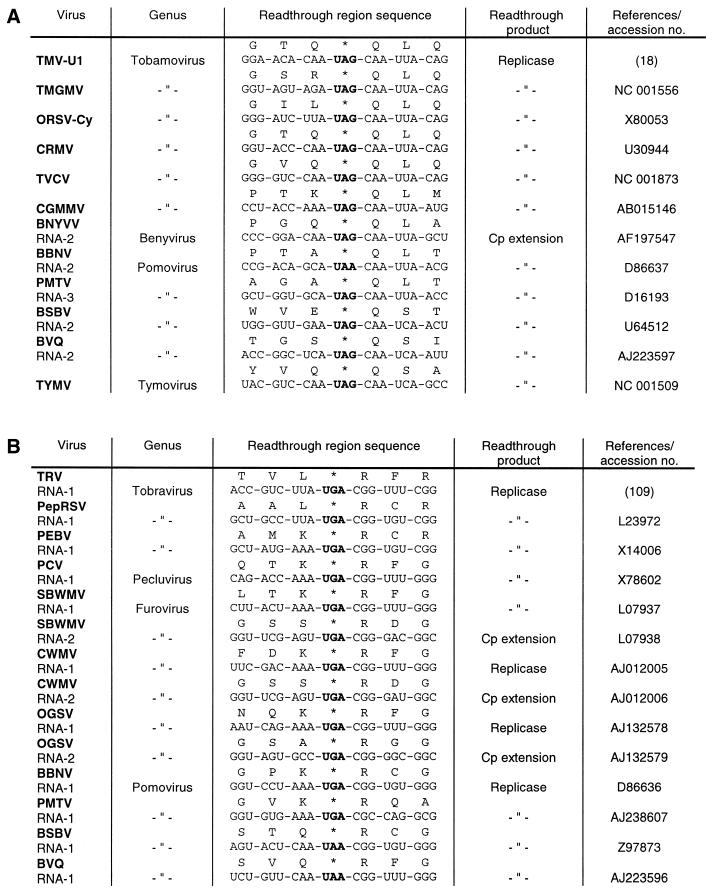

A comparison of sequences from a number of plant and animal viral RNAs that harbour a ‘leaky’ stop codon reveals that they have similar sequences around the stop codon, preferentially at the 3′ side. These readthrough regions can be classified into three groups according to the sequence homology. The type I readthrough region is found exclusively in plant viral RNAs of quite unrelated origin (Fig. 13A). These viruses share the six nucleotides CAA UYA at the 3′ side of the suppressed UAG or UAA codon. A number of nucleotide exchanges within this conserved sequence—embedded in a zein pseudogene—were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis. It was found that changes at each position completely abolished or greatly reduced UAG suppression by tRNATyr(GΨA) in a mRNA- and tRNA-depleted wheat germ extract (39), indicating that this tRNA species needs a very specific codon context for its suppressor activity. The hexanucleotide motif is apparently effectual in quite different systems. Thus, in vitro transcripts containing the TMV-specific readthrough region were translated in a messenger-dependent rabbit reticulocyte lysate and the importance of all 6 nt was shown by measuring UAG suppression via a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase reporter gene (87). Skuzeski et al. (88) had previously come to the same conclusion by studying the transient expression of a β-glucuronidase reporter gene containing part of the TMV-specific readthrough region in tobacco protoplasts. The effects on suppression of all possible single-base mutations in the hexanucleotide motif indicated that the consensus sequence of the form CAR YYA confers leakiness to all three stop codons.

Figure 13.

Plant viral readthrough sites. (A) Type I: TMV, tobacco mosaic virus; TMGMV, tobacco mild green mosaic virus; ORSV-Cy, odontoglossum ringspot tobamovirus; CRMV, chinese rape mosaic virus; TVCV, turnip vein clearing virus; CGMMV, cucumber green mottle mosaic virus; BNYVV, beet necrotic yellow vein virus; BBNV, broad bean necrosis virus; PMTV, potato mop-top furovirus; BSBV, beet soil-borne virus; BVQ, beet virus Q; TYMV, turnip yellow mosaic virus. (B) Type II: TRV, tobacco rattle virus; PepRSV, pepper ringspot virus; PEBV, pea early-browning virus; PCV, peanut clump virus; SBWMV, soil-borne wheat mosaic virus; CWMV, chinese wheat mosaic virus; OGSV, oat golden stripe virus. (C) Type III: TBSV, tomato bushy stunt virus; CNV, cucumber necrosis virus; CarMV, carnation mottle virus; SCV, saguaro cactus virus; JINRV, japanese iris necrotic ring virus; TCV, turnip crinkle virus; MNSV, melon necrotic spot virus; TNV, tobacco necrosis virus; MCMV, maize chlorotic mottle virus; PEMV, pea enation mosaic virus; BYDV, barley yellow dwarf virus; BWYV, beet western yellows virus; BMYV, beet mild yellowing virus; PLRV, potato leafroll virus. The luteoviruses and PLRV are separated by a horizontal line from the other type III viruses because their stop codons are followed by a valine instead of a glycine codon.

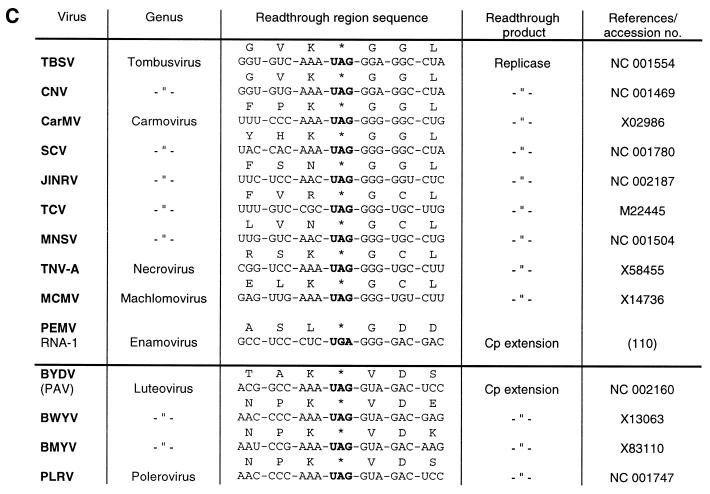

Readthrough regions of type II are found in plant and animal RNA viruses (Figs 13B and 14A). They have in common either a CGG in almost all plant virus and some alphavirus RNAs, or a CUA codon at the 3′ side of the suppressed UGA (rarely UAA) codon. Extensive mutational analyses of these triplets provided evidence that 1–3 nt are sufficient to stimulate UGA readthrough. Thus, it has been found that single nucleotide exchanges of either of the three positions in the CGG codon adjacent to the ‘leaky’ UGA in TRV RNA-1 (Fig. 13B) had only marginal effects on UGA suppression by tRNATrp(CmCA) upon translation in a wheat germ extract, whereas a pronounced influence on UGA readthrough was only seen if 2 or 3 nt were replaced simultaneously (89). As a consequence of the more flexible codon context accepted by tRNATrp(CmCA), as compared to tRNATyr(GΨA), this tRNA species is able to misread the UGA in nucleotide environments other than the TRV-specific codon context, like those of tobacco mosaic and sindbis virus and to a minor extent that of pea enation mosaic virus RNA (89; Figs 13 and 14). Similarly, it was established that cytoplasmic tRNAArg(U*CG) is capable of reading the UGA in quite different contexts, best of all in the pea enation mosaic and sindbis virus contexts (70). Although natural suppressor tRNAs differ in their efficiency to recognise ‘leaky’ stop codons in various codon contexts, none of them are capable of misreading ‘genuine’ stop codons at the end of open reading frames. For instance, the three natural UGA suppressors, tRNATrp(CmCA), tRNAArg(U*CG) and tRNACys(GCA), are absolutely incompetent for stimulating readthrough over the UGA at the end of the β-globin cistron in plant and animal in vitro systems (54,63,70,89).

Figure 14.

Animal viral readthrough sites. (A) Type II: SIN, sindbis virus; MID, middelburg virus; RRV, ross river virus; VEEV, venezuelan equine encephalitis virus; EEEV, eastern equine encephalitis virus; SFV, semliki forest virus; ONNV, O’nyong-nyong virus. The two alphaviruses SFV and ONNV do not contain ‘leaky’ UGA stop codons but instead contain a CGA arginine codon at this position. (B) Type III: Mo-MuLV, moloney murine leukemia virus; AKV, AKV murine leukemia virus; BaEV, baboon endogenous virus; SNV, spleen necrosis virus; FeLV, feline leukemia virus; GaLV, gibbon ape leukemia virus; WDSV, walleye dermal sarcoma virus. The epsilonretrovirus WDSV is separated by a horizontal line from the other type III viruses because its UAG stop codon is followed by an aspartate instead of a glycine codon.

The UGA codon and the nucleotides flanking this stop codon in sindbis virus RNA were subcloned into a heterologous sequence and readthrough efficiency was measured by cell-free translation of RNA transcripts in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate. Mutagenesis of residues in the CUA triplet downstream of the suppressed UGA (Fig. 14A) revealed that only the replacement of the cytidine by any of the other three nucleotides drastically reduced the readthrough efficiency (73).

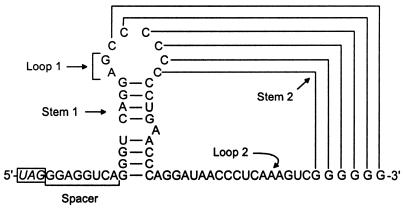

A more complex signal is required for efficient readthrough of the internal UAG of MuLV RNA located between the gag and pol coding regions (Fig. 3). The role of the nucleotide context was investigated in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate and the results indicated that readthrough is mediated by at least 50 nt on the 3′ side of the UAG codon (90–92). Within this region, a purine-rich spacer sequence consisting of 8 nt immediately following the UAG and a pseudoknot structure spanning the next 49 nt have been found to be essential for MuLV-specific UAG suppression (Fig. 15). The linear octanucleotide sequence of this bipartite signal is conserved in diverse gammaretroviral RNAs, representing type III of the listed readthrough regions (Fig. 14B). Alteration of 6 conserved nt within this motif by mutational analyses either eliminated or significantly reduced UAG suppression (91). Likewise, all of these viruses can form similar pseudoknot structures on the 3′ side of their UAG codons. Substitutions of several conserved nucleotides in loop 2 of the MuLV-specific pseudoknot resulted in detrimental effects on UAG readthrough in vitro, showing the importance of structural elements for efficient suppression (92).

Figure 15.

Proposed secondary and pseudoknot structures in the vicinity of the ‘leaky’ UAG codon in Mo-MuLV RNA. The bipartite signal involved in efficient UAG readthrough consists of 8 nt (underlined) immediately at the 3′ side of the UAG and a stem–loop structure, which can form a pseudoknot with downstream G residues (91,92).

Several plant RNA viruses, among them members of the carmovirus genus, exhibit a conserved octanucleotide sequence at the 3′ side of the suppressed UAG (or UGA) codon that is highly homologous to the corresponding motif in MuLV RNA (Figs 13C and 14B). However, a pseudoknot structure downstream of this sequence that is similar to the one present in retroviruses has not been detected (93), so it remains open whether these plant viruses utilise a similar strategy, i.e. a bipartite signal for stop codon suppression. Barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV), from the luteovirus group, utilises stop codon suppression to produce an extended coat protein which becomes part of the virion. Analysis of the cis-acting sequences required for UAG readtrough in oat protoplasts, wheat germ extract and in reticulocyte lysate revealed two essential regions at the 3′ side of the stop codon: a C-rich region in the vicinity of the UAG, and another more distal sequence located ∼700 nt downstream. It is speculated that the distal element interacts with the C-rich region by long-distance base pairing (94).

An influence of sequences immediately upstream of the termination codon on the efficiency of translational readthrough has been observed in the yeast S.cerevisiae (95,96), but appears to be of minor importance in plant and animal systems (73,87,89).

The precise molecular mechanism explaining the influence of downstream nucleotides and secondary structures on stop codon readthrough is still obscure. It has been suggested that the major forces involve (i) tRNA selection through stabilisation of the A-site tRNA:mRNA interaction by stacking effects; (ii) interaction between the stop codon and the rRNA; and (iii) interaction between the stop codon and the polypeptide chain release factor (85). Clearly, the competition between the suppressor tRNA and the release factor is of great significance. It has been proposed that the latter binds, in fact, to a tetranucleotide sequence (97). While the preferred termination signal differs in prokaryotic and eukaryotic species, a common feature appears to be a strong bias against a cytidine residue following a termination codon in all organisms (98,99), implying that any termination codon followed by a C is a weak stop codon. Consistent with this assumption is the presence of a C residue at the 3′ side of all readthrough regions of type I and type II (Figs 13A and B and 14A). The nucleotide following the stop codon at the 3′ side of type III readthrough regions is a G residue, which is the most favoured nucleotide at this position for efficient termination in the eukaryotic tetranucleotide stop signal (99), suggesting that readthrough by natural suppressor tRNAs is impaired. Possibly as a consequence of this unfavourable tetranucleotide signal, putative secondary structures beyond this position at the 3′ side are required for efficient readthrough as is the case for the UAG suppression in MuLV and BYDV RNA (92,94).

All three types of codon context sequences stimulating efficient stop codon readthrough in vivo and in vitro are not restricted to the suppression of a single stop codon. For example, UAG, UAA and UGA codons in the TMV-specific context (type I) can be suppressed in tobacco protoplasts (88), rabbit reticulocyte lysate (87) and wheat germ extract (39,41); UGA as well as UAA and UAG codons in the sindbis-specific context (type II) are suppressed in cultured cells of animal origin (23); and all three termination codons in the MuLV-specific context are effective in reticulocyte lysate and infected cells (100). Furthermore, a particular stop codon is not read by a single suppressor tRNA isoacceptor. Thus, it has been shown that the ‘leaky’ UGA codon in the TRV-specific context (Fig. 13B) is recognised in vitro by tobacco tRNATrp(CmCA), wheat tRNAArg(U*CG) and tobacco tRNACys(GCA), albeit with quite different efficiencies (54,63,70). Similarly, the ‘leaky’ UAG within TMV RNA is read by tobacco and wheat tRNATyr(GΨA), tobacco tRNAGln(CUG), tobacco and mouse tRNAGln(UmUG) and calf tRNALeu(CAA/CAG) in different in vitro systems (19,29,46,48,52).

CONCLUSION

The dogma of the non-ambiguity of the genetic code is shattered by the observation that a stop codon can have two or more meanings. Thus, the UGA codon may mediate termination of polypeptide synthesis or trigger the incorporation of tryptophan, arginine or cysteine. Likewise, the UAG termination codon may provoke the incorporation of tyrosine, glutamine or leucine. The misreading of termination codons is achieved by a variety of naturally occurring suppressor tRNAs. All of the nonsense suppressors characterised to date (with the exception of selenocysteine tRNA) are normal cellular tRNAs that are primarily needed for reading their cognate sense codons. As a consequence, recognition of stop codons by suppressor tRNAs necessitates unconventional base pairings in anticodon–codon interactions (Fig. 12).

Direct methods for the characterisation of potential suppressor tRNAs involve the purification of a specific suppressor tRNA from any organism or tissue, followed by examination of its suppressor activity in an in vitro system programmed with RNA transcripts that contain defined viral stop codon readthrough regions (19,48,52,54,63,70). Indirect procedures for the detection of presumable suppressor activities utilise the isolation of readthrough proteins from suitable systems and identification of the amino acid(s) incorporated at the stop codon site by protein sequencing. This allows the prediction of the nature of the putative tRNA species involved in the suppression event (62,71,78). In most cases the same natural suppressor tRNAs have been identified by direct and indirect means, with two exceptions. The incorporation of lysine in response to an internal UAG codon within the yeast Ste6 gene (78) and of serine at the UGA terminating the β-globin mRNA (71) suggests the existence of further suppressors not yet characterised in detail.

The observation that more than one natural UAG/UAA and UGA suppressor exist in eukaryotes raises the question whether misreading of a stop codon by suppressor tRNAs is regulated or not. One factor that influences readthrough activity is simply the abundance of a specific tRNA suppressor in a given tissue. This is most obvious for the distribution of tRNATyr(GΨA) versus tRNATyr(QΨA) [the latter not being a UAG suppressor (Fig. 5)], in various plant and animal tissues. In addition to the available amount, a number of intrinsic features of the suppressor tRNA contribute to the ability to read non-cognate codons. Apart from anticodon–codon affinity, the degree of base modifications within the anticodon or in the vicinity of the anticodon may up- or down-regulate the efficiency of misreading.

In order to out-compete the polypeptide chain release factor for their common target, an absolute prerequisite for the action of natural suppressor tRNA is a suitable nucleotide context, preferentially at the 3′ side of the suppressed stop codon. This context may consist of only 3–6 downstream nt, or may involve more complex signals like stem–loop and pseudoknot structures.

Without doubt, a bulk of RNA viruses rely on stop codon readthrough to express part of their genetic information (Fig. 1). Hence, the question arises whether the eukaryotic host organisms also profit from their tRNAs that read termination codons and, thus, facilitate the multiplication of viral pathogens or, in other words, whether these natural suppressor tRNAs have any essential or at least beneficial effect on cellular biosynthesis. One of the very few examples of a natural cellular readthrough protein is the rabbit β-globin readthrough polypeptide that has been identified in reticulocyte lysate by immunoblotting (71,101). This β′-globin is generated by readthrough over the ‘genuine’ UGA stop codon at the end of the β-globin cistron (flanked by a G at the 3′ side), but it is unknown whether it has an essential function. However, an increasing number of reports have been published recently indicating that natural suppressor tRNAs have apparently corrected deleterious nonsense mutations within open reading frames of genes from the human and yeast genome in vivo (e.g. 44,78,102,103). Although this is a mostly unpredictable and inefficient event, the low synthesis of a full-length product might be sufficient in special cases to ensure viability of the organism.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This review article is dedicated to Professor Hans J. Gross on the occasion of his 65th birthday. About 20 years ago he initiated the characterisation of natural suppressor tRNAs, at a time when their general importance was still unpredictable. H.B. is grateful for his ever lasting advice and encouragement and takes this opportunity to thank all of her former coworkers who have committed a great deal of effort in the field of nonsense suppressors. H.B. also thanks the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for long-standing support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hatfield D.L., Levin,J.G., Rein,A. and Oroszlan,S. (1992) Translational suppression in retroviral gene expression. Adv. Virus Res., 41, 193–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rohde W., Gramstat,A., Schmitz,J., Tacke,E. and Prüfer,D. (1994) Plant viruses as model systems for the study of non-canonical translation. J. Gen. Virol., 75, 2141–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farabaugh P.J. and Björk,G.R. (1999) How translational accuracy influences reading frame maintenance. EMBO J., 18, 1427–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murgola E.J. (1985) tRNA, suppression, and the code. Annu. Rev. Genet., 19, 57–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eggertsson G. and Söll,D. (1988) Transfer ribonucleic acid-mediated suppression of termination codons in Escherichia coli.Microbiol. Rev., 52, 354–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engelberg-Kulka R. and Schoulaker-Schwarz,R. (1988) Stop is not the end: physiological implications of translational readthrough. J. Theor. Biol., 131, 477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valle R.P.C. and Morch,M.D. (1988) Stop making sense or regulation at the level of termination in eucaryotic protein synthesis. FEBS Lett., 235, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatfield D.L., Smith,D.W.E., Lee,B.J., Worland,P.J. and Oroszlan,S. (1990) Structure and function of suppressor tRNAs in higher eukaryotes. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol., 25, 71–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santos M.A.S. and Tuite,M.F. (1993) New insights into mRNA decoding – implications for heterologous protein synthesis. Trends Biotechnol., 11, 500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maia I.G., Seron,K., Haenni,A.-L. and Bernardi,F. (1996) Gene expression from viral RNA genomes. Plant Mol. Biol., 32, 367–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gesteland R.F. and Atkins,J.F. (1996) Recoding: dynamic reprogramming of translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 65, 741–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertram G., Innes,S., Minella,O., Richardson,J.P. and Stansfield,I. (2001) Endless possibilities: translation termination and stop codon recognition. Microbiology, 147, 255–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baranov P.V., Gurvich,O.L., Fayet,O., Prere,M.F., Miller,W.A., Gesteland,R.F., Atkins,J.F. and Giddings,M.C. (2001) Recode: a database of frameshifting, bypassing and codon redefinition utilized for gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 264–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsh D. (1971) Tryptophan transfer tRNA as the UGA suppressor. J. Mol. Biol., 58, 439–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiner A.M. and Weber,K. (1973) A single UGA codon functions as a natural termination signal in the coliphage Qβ coat protein cistron. J. Mol. Biol., 80, 837–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofstetter H., Monstein,H.-J. and Weissmann,C. (1974) The readthrough protein A1 is essential for the formation of viable Qβ particles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 374, 238–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelham H.R.B. (1978) Leaky UAG termination codon in tobacco mosaic virus RNA. Nature, 272, 469–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goelet P., Lomonossoff,G.P., Butler,P.J.G., Akam,M.E., Gait,M.J. and Karn,J. (1982) Nucleotide sequence of tobacco mosaic virus RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 79, 5818–5822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beier H., Barciszewska,M., Krupp,G., Mitnacht,R. and Gross,H.J. (1984) UAG readthrough during TMV RNA translation: isolation and sequence of two tRNAsTyr with suppressor activity from tobacco plants. EMBO J., 3, 351–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe Y., Emori,Y., Ooshika,I., Meshi,T., Ohno,T. and Okada,Y. (1984) Synthesis of TMV-specific RNAs and proteins at the early stage of infection in tobacco protoplasts: transient expression of the 30K protein and its mRNA. Virology, 133, 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishikawa M., Meshi,T., Motoyoshi,F., Takamatsu,N. and Okada,Y. (1986) In vitro mutagenesis of the putative replicase genes of tobacco mosaic virus. Nucleic Acids Res., 14, 8291–8305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshinaka Y., Katoh,I., Copeland,T.D. and Oroszlan,S. (1985) Murine leukemia virus protease is encoded by the gag-pol gene and is synthesized through suppression of an amber termination codon. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 82, 1618–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li G. and Rice,C.M. (1989) Mutagenesis of the in-frame opal termination codon preceding nsP4 of sindbis virus: studies of translation readthrough and its effect on virus replication. J. Virol., 63, 1326–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lahijani R.S., Otteson,E.W. and St.Jeor,S.C. (1992) A possible role for nonsense suppression in the synthesis of a human cytomegalovirus 58-kDa virion protein. Virology, 186, 309–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felsenstein K.M. and Goff,S.P. (1992) Mutational analysis of the gag-pol junction of Moloney murine leukemia virus: requirements for expression of the gag-pol fusion protein. J. Virol., 66, 6601–6608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones D.S., Nemoto,F., Kuchino,Y., Masuda,M., Yoshikura,H. and Nishimura,S. (1989) The effect of specific mutations at and around the gag-pol gene junction of Moloney murine leukemia virus. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 5933–5945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bienz M. and Kubli,E. (1981) Wild-type tRNATyr(G) reads the TMV RNA stop codon, but Q base-modified tRNATyr(Q) does not. Nature, 294, 188–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanley J. and Vassilenko,S. (1978) A different approach to RNA sequencing. Nature, 274, 87–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beier H., Barciszewska,M. and Sickinger,H.-D. (1984) The molecular basis for the differential translation of TMV RNA in tobacco protoplasts and wheat germ extracts. EMBO J., 3, 1091–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barciszewski J., Barciszewska,B., Suter,B. and Kubli,E. (1985) Plant tRNA suppressors: in vivo readthrough properties and nucleotide sequence of yellow lupin seeds tRNATyr. Plant Sci., 40, 193–196. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beier H., Zech,U., Zubrod,E. and Kersten,H. (1987) Queuine in plants and plant tRNAs: differences between embryonic tissue and mature leaves. Plant Mol. Biol., 8, 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Junker V., Teichmann,T., Hekele,A., Fingerhut,C. and Beier,H. (1997) The tRNATyr-isoacceptor and their genes in the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila: cytoplasmic tRNATyr has a QΨA anticodon and is coded by multiple intron-containing genes. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 4194–4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okada N., Noguchi,S., Kasai,H., Shindo-Okada,N., Ohgi,T., Goto,T. and Nishimura,S. (1979) Novel mechanism of post-transcriptional modification of tRNA. J. Biol. Chem., 254, 3067–3073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sprinzl M., Horn,C., Brown,M., Ioudovitch,A. and Steinberg,S. (1998) Compilation of tRNA sequences and sequences of tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 148–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson G.D., Pirtle,I.L. and Pirtle,R.M. (1985) The nucleotide sequence of tyrosine tRNAQ*ΨA from bovine liver. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 236, 448–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okada Y., Shindo-Okada,N., Sato,S., Itoh,Y.H., Oda,D.-I. and Nishimura,S. (1978) Detection of unique tRNA species in tumor tissues by Escherichia coli guanine insertion enzyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 75, 4247–4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landin R.-M., Boisnard,M. and Petrissant,G. (1979) Correlation between the presence of tRNAHis(CUG) and the erythropoietic function in foetal sheep liver. Nucleic Acids Res., 7, 1635–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White B.N. and Tener,G.M. (1973) Activity of a transfer RNA modifying enzyme during the development of Drosophila and its relationship to the su(s) locus. J. Mol. Biol., 74, 635–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zerfass K. and Beier,H. (1992) Pseudouridine in the anticodon GΨA of plant cytoplasmic tRNATyr is required for UAG and UAA suppression in the TMV-specific context. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 5911–5918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griffey R.H., Davis,D., Yamaizumi,Z., Nishimura,S., Bax,A., Hawkins,B. and Poulter,C.D. (1985) 15N-labeled Escherichia coli tRNAfMet, tRNAGlu, tRNATyr, and tRNAPhe. J. Biol. Chem., 260, 9734–9741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schüll C. and Beier,H. (1994) Three Tetrahymena tRNAGln isoacceptors as tools for studying unorthodox codon recognition and codon context effects during protein synthesis in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 1974–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin J.P., Aker,M., Sitney,K.C. and Mortimer,R.K. (1986) First position wobble in codon-anticodon pairing: amber suppression by a yeast glutamine tRNA. Gene, 49, 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss W.A. and Friedberg,E.C. (1986) Normal yeast tRNAGln(CAG) can suppress amber codons and is encoded by an essential gene. J. Mol. Biol., 192, 725–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoja U., Wellein,C., Greiner,E. and Schweizer,E. (1998) Pleiotropic phenotype of acetyl-CoA-carboxylase-defective yeast cells. Viability of a BPL1-amber mutation depending on its readthrough by normal tRNAGln(CAG). Eur. J. Biochem., 254, 520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pure A.G., Robinson,G.W., Naumovski,L. and Friedberg,E.C. (1985) Partial suppression of an ochre mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by multicopy plasmids containing a normal yeast tRNAGln gene. J. Mol. Biol., 183, 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuchino Y., Beier,H., Akita,N. and Nishimura,S. (1987) Natural UAG suppressor glutamine tRNA is elevated in mouse cells infected with Moloney murine leukemia virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 2668–2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng Y.-X., Hatfield,D.L., Rein,A. and Levin,J.G. (1989) Translational readthrough of the murine leukemia virus gag gene amber codon does not require virus-induced alteration of tRNA. J. Virol., 63, 2405–2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grimm M., Nass,A., Schüll,C. and Beier,H. (1998) Nucleotide sequences and functional characterization of two tobacco UAG suppressor tRNAGln isoacceptors and their genes. Plant Mol. Biol., 38, 689–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vacher J., Grosjean,H., Houssier,C. and Buckingham,R.H. (1984) The effect of point mutations affecting Escherichia coli tryptophan tRNA on anticodon-anticodon interactions and on UGA suppression. J. Mol. Biol., 177, 329–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bouadloun F., Srichaiyo,T., Isaksson,L.A. and Björk,G.R. (1986) Influence of modification next to the anticodon in tRNA on codon context sensitivity of translational suppression and accuracy. J. Bacteriol ogy, 166, 1022–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson R.K. and Roe,B.A. (1989) Presence of the hypermodified nucleotide N6-(Δ2-isopentenyl)-2-methylthioadenosine prevents codon misreading by Escherichia coli phenylalanyl-transfer RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 409–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valle R.P.C., Morch,M.-D. and Haenni,A.-L. (1987) Novel amber suppressor tRNAs of mammalian origin. EMBO J., 6, 3049–3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mayo M.A. (1982) Polypeptides induced by tobacco rattle virus during multiplication in tobacco protoplasts. Intervirology, 17, 240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zerfass K. and Beier,H. (1992) The leaky UGA termination codon of tobacco rattle virus RNA is suppressed by tobacco chloroplast and cytoplasmic tRNAsTrp with CmCA anticodon. EMBO J., 11, 4167–4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raferty A.L., Bermingham,J.R.,Jr and Yarus,M. (1986) Mutation in the D arm enables a suppressor with a CUA anticodon to read both amber and ochre codons in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 190, 513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith D. and Yarus,M. (1989) Transfer RNA structure and coding specificity I. Evidence that a D-arm mutation reduces tRNA dissociation from the ribosome. J. Mol. Biol., 206, 489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grosjean H.J. and Chantrenne,H. (1980) On codon-anticodon interactions. Mol. Biol. Biochem. Biophys., 32, 347–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ericson J.U. and Björk,G.R. (1991) tRNA anticodons with the modified nucleoside 2-methylthio-N6-(4-hydroxyisopentenyl)adenosine distinguish between bases 3′ of the codon. J. Mol. Biol., 218, 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sugiura M. (1992) The chloroplast genome. Plant Mol. Biol., 19, 149–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Geller A.I. and Rich,A. (1980) A UGA termination suppression tRNATrp active in rabbit reticulocytes. Nature, 283, 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cordell B., DeNoto,F.M., Atkins,J.F., Gesteland,R.F., Bishop,J.M. and Goodman,H.M. (1980) The forms of tRNATrp found in avian sarcoma virus and uninfected chicken cells have structural identity but functional distinctions. J. Biol. Chem., 255, 9358–9368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feng Y.-X., Copeland,T.D., Oroszlan,S., Rein,A. and Levin,J.G. (1990) Identification of amino acids inserted during suppression of UAA and UGA termination codons at the gag-pol junction of Moloney murine leukemia virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 8860–8863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Urban C. and Beier,H. (1995) Cysteine tRNAs of plant origin as novel UGA suppressors. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 4591–4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grimm M., Brünen-Nieweler,C., Junker,V., Heckmann,K. and Beier,H. (1998) The hypotrichous ciliate Euplotes octocarinatus has only one type of tRNACys with GCA anticodon encoded on a single macronuclear DNA molecule. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 4557–4565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meyer F., Schmidt,H.J., Plümper,E., Hasilik,A., Mersmann,G., Meyer,H.E., Engström,A. and Heckmann,K. (1991) UGA is translated as cysteine in pheromone 3 of Euplotes octocarinatus.Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 3758–3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liang A., Brünen-Nieweler,C., Muramatsu,T., Kuchino,Y., Beier,H. and Heckmann,K. (2001) The ciliate Euplotes octocarinatus expresses two polypeptide release factors of the type eRF1. Gene, 262, 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muramatsu T., Heckmann,K., Kitanaka,C. and Kuchino,Y. (2001) Molecular mechanism of stop codon recognition by eRF1: a wobble hypothesis for peptide anticodons. FEBS Lett., 488, 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Komine Y., Adachi,T., Inokuchi,H. and Ozeki,H. (1990) Genomic organization and physical mapping of the transfer RNA genes in Escherichia coli K12. J. Mol. Biol., 212, 579–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hani J. and Feldmann,H. (1998) tRNA genes and retroelements in the yeast genome. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 689–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baum M. and Beier,H. (1998) Wheat cytoplasmic arginine tRNA isoacceptor with a U*CG anticodon is an efficient UGA suppressor in vitro.Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 1390–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chittum H.S., Lane,W.S., Carlson,B.A., Roller,P.P., Lung,F.-D.T., Lee,B.J. and Hatfield,D.L. (1998) Rabbit β-globin is extended beyond its UGA stop codon by multiple suppressions and translational reading gaps. Biochemistry, 37, 10866–10870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takkinen K. (1986) Complete nucleotide sequence of the nonstructural protein genes of semliki forest virus. Nucleic Acids Res., 14, 5667–5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li G. and Rice,C.M. (1993) The signal for translational readthrough of a UGA codon in sindbis virus RNA involves a single cytidine residue immediately downstream of the termination codon. J. Virol., 67, 5062–5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Crick F.H.C. (1966) Codon-anticodon pairing: the wobble hypothesis. J. Mol. Biol., 19, 548–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hottinger H., Stadelmann,B., Pearson,D., Frendewey,D., Kohli,J. and Söll,D. (1984) The Schizosaccharomyces pombe sup3-i suppressor recognizes ochre, but not amber codons in vitro and in vivo. EMBO J., 3, 423–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murgola E.J., Pagel,F.T. and Hijazi,D.A. (1984) Codon context effects in missense suppression. J. Mol. Biol., 175, 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Strigini P. and Brickman,E. (1973) Analysis of specific misreading in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 75, 659–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fearon K., McClendon,V., Bonetti,B. and Bedwell,D.M. (1994) Premature translation termination mutations are efficiently suppressed in a highly conserved region of yeast Ste6p, a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter familiy. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 17802–17808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Topal M.D. and Fresco,J.R. (1976) Complementary base pairing and the origin of substitution mutations. Nature, 263, 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hunter W.N., Brown,T., Anand,N.N. and Kennard,O. (1986) Structure of an adenine : cytosine base pair in DNA and its implications for mismatch repair. Nature, 320, 552–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brown T., Hunter,W.N., Kneale,G. and Kennard,O. (1986) Molecular structure of the G:A base pair in DNA and its implications for the mechanism of transversion mutations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 2402–2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Holbrook S.R., Cheong,C., Tinoco,I.,Jr and Kim,S.-H. (1991) Crystal structure of an RNA double helix incorporating a track of non-Watson-Crick base pairs. Nature, 353, 579–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morse S.E. and Draper,D.E. (1995) Purine-purine mismatches in RNA helices: evidence for protonated G:A pairs and next-nearest neighbor effects. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 302–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kopelowitz J., Hampe,C., Goldman,R., Reches,M. and Engelberg-Kulka,H. (1992) Influence of codon context on UGA suppression and readthrough. J. Mol. Biol., 225, 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Buckingham R.H. (1994) Codon context and protein synthesis: enhancements of the genetic code. Biochimie, 76, 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Phillips-Jones M.K., Hill,L.S.J., Atkinson,J. and Martin,R. (1995) Context effects on misreading and suppression at UAG codons in human cells. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 6593–6600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Valle R.P.C., Drugeon,G., Devignes-Morch,M.-D., Legocki,A.B. and Haenni,A.-L. (1992) Codon context effect in virus translational readthrough: a study in vitro of the determinants of TMV and Mo-MuLV amber suppression. FEBS Lett., 306, 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Skuzeski J.M., Nichols,L.M., Gesteland,R.F. and Atkins,J.F. (1991) The signal for a leaky UAG stop codon in several plant viruses includes the two downstream codons. J. Mol. Biol., 217, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Urban C., Zerfass,K., Fingerhut,C. and Beier,H. (1996) UGA suppression by tRNATrp(CmCA) occurs in diverse virus RNAs due to a limited influence of the codon context. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 3424–3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Honigman A., Wolf,D., Yaish,S., Falk,H. and Panet,A. (1991) cis acting RNA sequences control the gag-pol translation readthrough in murine leukemia virus. Virology, 183, 313–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Feng Y.-X., Yuan,H., Rein,A. and Levin,J.G. (1992) Bipartite signal for readthrough suppression in murine leukemia virus mRNA: an eight-nucleotide purine-rich sequence immediately downstream of the gag termination codon followed by an RNA pseudoknot. J. Virol., 66, 5127–5132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wills N.M., Gesteland,R.F. and Atkins,J.F. (1994) Pseudoknot-dependent readthrough of retroviral gag termination codons: importance of sequences in the spacer and loop 2. EMBO J., 13, 4137–4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miller W.A., Dinesh-Kumar,S.P. and Paul,C.P. (1995) Luteovirus gene expression. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci., 14, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brown C.M., Dinesh-Kumar,S.P. and Miller,W.A. (1996) Local and distant sequences are required for efficient readthrough of the barley yellow dwarf virus PAV coat protein gene stop codon. J. Virol., 70, 5884–5892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bonetti B., Fu,L., Moon,J. and Bedwell,D.M. (1995) The efficiency of translation termination is determined by a synergistic interplay between upstream and downstream sequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol., 251, 334–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mottagui-Tabar S., Tuite,M.F. and Isaksson,L.A. (1998) The influence of 5′ codon context on translation termination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.Eur. J. Biochem., 257, 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tate W.P., Poole,E.S., Horsfield,J.A., Mannering,S.A., Brown,C.M., Moffat,J.G., Dalphin,M.E., McCaughan,K.K., Major,L.L. and Wilson,D.N. (1995) Translational termination efficiency in both bacteria and mammals is regulated by the base following the stop codon. Biochem. Cell Biol., 73, 1095–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brown C.M., Stockwell,P.A., Trotman,C.N.A. and Tate,W.P. (1990) The signal for the termination of protein synthesis in procaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 2079–2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Brown C.M., Stockwell,P.A., Trotman,C.N.A. and Tate,W.P. (1990) Sequence analysis suggests that tetra-nucleotides signal the termination of protein synthesis in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 6339–6345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Feng Y.-X., Levin,J.G., Hatfield,D.L., Schaefer,T.S., Gorelick,R.J. and Rein,A. (1989) Suppression of UAA and UGA termination codons in mutant murine leukemia viruses. J. Virol., 63, 2870–2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hatfield D.L., Thorgeirsson,S.S., Copeland,T.D., Oroszlan,S. and Bustin,M. (1988) Immunopurification of the suppressor tRNA dependent rabbit β-globin readthrough protein. Biochemistry, 27, 1179–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kopczynski J.B., Raff,A.C. and Bonner,J.J. (1992) Translational readthrough at nonsense mutations in the HSF1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet., 234, 369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Peltola M., Chiatayat,D., Peltonen,L. and Jalanko,A. (1994) Characterization of a point mutation in aspartylglucosaminidase gene: evidence for a readthrough of a translational stop codon. Hum. Mol. Genet., 3, 2237–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pringle D.R. (1999) Virus Taxonomy – 1999. The universal system of virus taxonomy, updated to include the new proposals ratified by the international committee on taxonomy of viruses during 1998. Arch. Virol., 144, 421–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shinnick T.M., Lerner,R.A. and Sutcliffe,J.G. (1981) Nucleotide sequence of Moloney murine leukaemia virus. Nature, 293, 543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Strauss E.G., Rice,C.M. and Strauss,J.H. (1984) Complete nucleotide sequence of the genomic RNA of sindbis virus. Virology, 133, 92–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Suter B., Altwegg,M., Choffat,Y. and Kubli,E. (1986) The nucleotide sequence of two homogeneic Drosophila melanogaster tRNATyr isoacceptors: application of a rapid tRNA anticodon sequencing method using S-1 nuclease. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 247, 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hanyu N., Kuchino,Y., Nishimura,S. and Beier,H. (1986) Dramatic events in ciliate evolution: alteration of UAA and UAG termination codons to glutamine codons due to anticodon mutations in two Tetrahymena tRNAsGln. EMBO J., 5, 1307–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hamilton W.D.O., Boccara,M., Robinson,D.J. and Baulcombe,D.C. (1987) The complete nucleotide sequence of tobacco rattle virus RNA-1. J. Gen. Virol., 68, 2563–2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Demler S.A. and de Zoeten,G.A. (1991) The nucleotide sequence and luteovirus-like nature of RNA 1 of an aphid non-transmissible strain of pea enation mosaic virus. J. Gen. Virol., 72, 1819–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Etzerodt M., Mikkelsen,T., Pedersen,F.S., Kjeldgaard,N.O. and Jørgensen,P. (1984) The nucleotide sequence of the Akv murine leukemia virus genome. Virology, 134, 196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Weaver T.A., Talbot,K.J. and Panganiban,A.T. (1990) Spleen necrosis virus gag polyprotein is necessary for particle assembly and release but not for proteolytic processing. J. Virol., 64, 2642–2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]