Abstract

Aims:

This meta-research study aimed to investigate the level of compliance with the Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) Guidelines for the inclusion, analysis, and reporting of sex/gender, in periodontitis-related randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Materials and Methods:

Following the inclusion of RCTs related to the treatment of periodontitis published between 2018-2019, we applied the SAGER checklist to assess the adherence to sex/gender reporting guidelines. We used non-parametric descriptive statistics and correlation models to test the association of the dependent outcome with other variables.

Results:

101 articles were included in the analysis. The female enrollment ranged between 30-94%. 26 studies enrolled less than 50% of female participants. The overall SAGER score (OSS) of item fulfillment ranged between 0-7 items with an average of 1.9 items signifying poor guideline adherence to the SAGER guidelines. These findings were not associated with the corresponding author gender (p= 0.623), publication year (p=0.947), and funding source (p=0.133). However, a significant but negative correlation with journal impact factor (r=−0.253, p=0.026) was observed.

Conclusions:

Sex and gender were frequently disregarded in clinical trial reporting. This oversight might limit the understanding of sex/gender differences in periodontitis-related clinical trials.

Keywords: clinical trial, sex, gender, periodontitis, periodontal therapy

Introduction

Although sex and gender are related, they are distinctly different (Guenther EA, 2018). Sex is based on biological characteristics, the paired sex chromosomes a person inherits, physiological features, reproductive anatomy, gene expression, hormone function, and biological differences (Guenther EA, 2018). Sex is categorized by the set of paired sex chromosomes as female (XX) or male (XY). In contrast, gender is based on the way a person defines, perceives, and identifies themselves in cultural and social settings (World Health Organization, 2018)(2). These descriptions include man, woman and expand over a binary fluid spectrum (Montanez, 2017).

Historically, clinical trials using exclusively male participants were assumed to produce medical knowledge applicable and generalized to all populations (Public Health Service Task Force, 1985). Research methodologists have historically tried to reduce variances in data by encouraging investigators to use similar age, weight and sex of participants in RCTs. Female participants were typically excluded as suboptimal due to their sex hormonal fluctuations. Moreover, following the thousands of birth defects as a consequence of thalidomide use (Brook, Jarvis, & Newman, 1977), the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects and Biomedical Behavioral Research and later the FDA established a protectionist rule according to which pregnant women were too vulnerable to be included in trials (Office of Human Research Protections, 2014). As the research community began to recognize unique differences between female and male biology, US Public Health Service Task Force on Women’s Health Issues released a report on the low representation of females in clinical trials and suboptimal women’s health care. The report recommended that research would need to focus on diseases unique to the inclusion of females in clinical trials (Public Health Service Task Force, 1985). Ironically, at the same time, the natural history study on the prevalence of periodontitis was published (Loe, Anerud, Boysen, & Morrison, 1986) as a single sex (all male participants) reporting on the rates of progression of periodontal destruction.

In 1990, the NIH established the Office of Research on Women’s Health, which later spearheaded the passage of the 1993 Revitalization Act, ensuring women be included in RCTs and reversing the 1977 FDA guidance banning women in clinical research (Food and Drug Administration, 1977; National Institute of Health, 1994). The 1993 Revitalization Act required principal investigators who apply for NIH grants to describe the plans for the inclusion or the justification for the exclusion of women (National Institute of Health, 1993). Subsequently, the FDA, CDC and AHRQ developed similar guidelines.

However, this delay had negative repercussions for female populations. During the period that these laws were being enacted, several drugs including low dose aspirin or zolpidem (Ambien) that previously had been tested solely on males were starting to manifest widespread side effects exclusively on females (Chiang, Hurwitz, Ridker, & Serhan, 2006; Farkas, Unger, & Temple, 2013; Pettinati et al., 2008). Between 1997-2013, 80% of those withdrawn drugs by the FDA presented significantly greater risks for females (Norman, Fixen, Saseen, Saba, & Linnebur, 2017; Parekh, Fadiran, Uhl, & Throckmorton, 2011). While the NIH required reporting of subject accrual stratified by sex (National Institute of Health, 2001) , the FDA passed a new regulation requiring new drug applications must present safety and efficacy data stratified by sex(Food and Drug Administration, 2014).

Consequently, the NIH convened an internal task force to monitor the inclusion of women in federally funded studies (Office of Research on Women’s Health, 2015) and established the Eliminating Disparities in Clinical Trials (EDICT) project expanding the inclusion of underrepresented populations (Goldberg, 2009; Spiker & Weinberg, 2009).

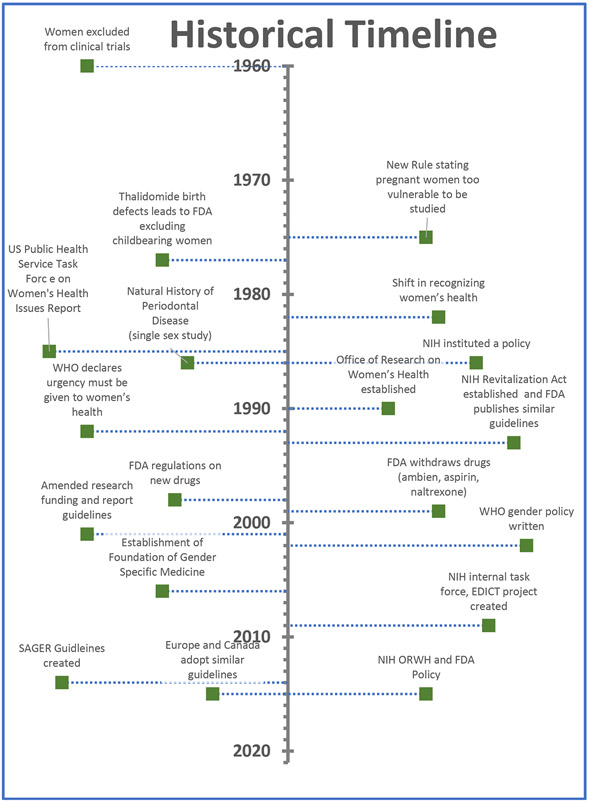

Furthermore, sex and gender inclusion guidelines from 45 national level funding agencies across Europe, North America, and Australia showed a wide variation in the way that sex/gender were conceptualized (Hankivsky, Springer, & Hunting, 2018). Consequently, the European Association of Science Editors established a Gender Policy Committee consisting of a panel of thirteen experts representing nine European countries (De Castro, Heidari, & Babor, 2016). The Committee surveyed 716 journal editors and publishers and found that only 7% of journals had policies on reporting of gender/sex (Heidari, Babor, De Castro, Tort, & Curno, 2016). As a result, the Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines and checklists for authors and editors were developed to help standardize sex and gender reporting in scientific publications (De Castro et al., 2016; Heidari et al., 2016). Figure 1 presents a brief historical timeline on the evolution of sex/gender guidelines.

Figure 1 –

Historical Timeline

The aim of this meta-research study was to determine the level of compliance with the SAGER guidelines for the inclusion, analysis, and reporting of sex/gender, in periodontitis-related RCTs 2 years after the guidelines were published. We hypothesized that there is an overall lack of adherence to the SAGER guidelines in inclusion, analysis, and reporting of sex/gender in periodontitis-related RCTs.

Materials and Methods:

The search strategy incorporated examination of electronic databases only. Non-English journals were excluded. A MEDLINE (PubMed) and SCOPUS search was conducted by one of the authors and the University of Connecticut Health Sciences Library. Human randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials published between January 2018 - December 2019 were included. The RCTs were limited to patients with periodontitis. The following search strategy was followed to filter and produce the study list (24):

periodont*[tw] AND disease[tw] AND (randomized controlled trial[pt] OR (randomized[tw] AND controlled[tw] AND trial[tw])) *

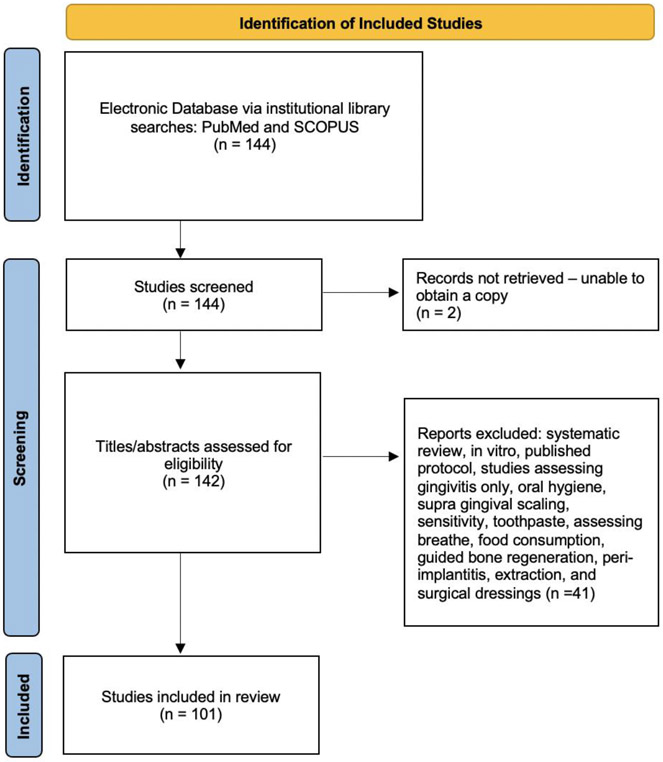

A flow diagram (Figure 2) was used to show the selection process of the included studies (Page et al., 2021). The titles of the identified articles were initially screened. Further screenings for relevance analysis of the abstract and full text were performed by two reviewers.

Figure 2 –

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Inclusion Criteria:

Studies were included if they were: 1) randomized clinical trials conducted on patients with periodontitis and/or receiving periodontal therapy, 2) published in 2018 or 2019 and 3) with study populations limited to patients with periodontitis. There was no inclusion criterion related to a cutoff number of enrolled subjects or follow up period.

Exclusion Criteria:

The following exclusion criteria were applied on: 1) in-vitro or non-human studies, 2) non-English language, 3) grey literature, unpublished literature as well as other databases such as Google Scholar or Research Gate as well as letters, editorials, research theses, letters to the editor, case reports, retrospective studies, abstracts, published protocols, systematic reviews, technical reports, conference proceedings, studies on cadavers, and literature review papers, 4) studies conducted in any other field of dentistry, 5) studies assessing gingivitis, oral hygiene, supra-gingival scaling, breathe, toothpastes, or sensitivity, and 6) studies conducted on peri-implantitis, extraction site preservation or surgical dressings.

Data Extraction:

The primary outcome was the overall adherence to the SAGER guidelines for the title/abstract, introduction, methods, results, and discussion. Table 1 summarized the SAGER criteria. Moreover, the following secondary variables were assessed: 1) trial enrollment numbers/rates stratified per sex, 2) source of funding (federal, industry, no funding), 3) journal metrics/impact factor and 4) sex of corresponding author based on first name recognition.

Table 1 –

SAGER Criteria (23):

| 1. Title and Abstract | 1. Do the title or abstract explain if results of the study are to be applied to only one sex or gender? |

| 2. Background/Introduction | 2. Are the terms sex and gender used in the background? 3. Are sex/gender identified as relevant or not in the research question, hypothesis, or objective? 4. Does background discuss why sex/gender differences may be expected? |

| 3. Criteria for inclusion-exclusion | 5. Do the inclusion-exclusion criteria consider sex-gender differences? 6. Do they specifically exclude pregnant females? |

| 4. Methods | 6. Is the number of female/male subjects reported? 7. If so, what is the % of females in the study? 8. If only one sex was included is it discussed why? |

| 5. Results and Analysis | 9. Did the study extract data by sex? 10. Were any subgroup analysis by sex completed? 11. Do results distinguish between findings for females/males? |

| 6. Discussion and Conclusion | 12. Do they report conclusions that are different for women and men? 13. If adverse effects are reported, is information sex-disaggregated? 14. Does the study address sex/gender implications for clinical practice or research? 15. If no analysis by sex/gender was performed is it explained why? |

To facilitate this process, we used a standardized data extraction. The following items were collected from the article and arranged in fields: publication year, source of funding, journal impact factor (Clarivate Analytics, 2019), number of reported female and male subjects, percentage of enrolled female subjects, results adherence to SAGER guidelines. SAGER guideline adherence was assessed based on the response to a total of 14 items for all studies with the exception of the single sex studies, which required one additional item (Table 1). In addition, we extracted the sex of the corresponding author based on first name recognition using an internet search engine with the author’s name and affiliation (Genderize.io). In order to assign gender to the corresponding author, we used the website genderize.io with a cutoff probability of 0.55.

Two reviewers read each article and extracted the data independently according to a data collection form ensuring systematic recording of study variables. We used a dichotomous scoring method (1 or 0) for the following categories in regards to sex/gender specific adherence per SAGER item. A score of 1 signifying adherence or a score of 0 signifying lack of adherence. Any disagreement between reviewers was settled after discussion with principal investigators. An overall SAGER score (OSS) was calculated after adding scoring points per item.

Statistical Analysis:

Cohen’s Kappa statistic was used to assess inter-rater agreement. For the descriptive analysis categorical variables were expressed as proportion percent. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare item fulfillment between 2018 and 2019. For the exploratory bivariate association between Overall SAGER Score (OSS) and related variables, we applied non-parametric Spearman correlation statistics. An a priori bivariate analysis cutoff of p=0.1 will be used for the multivariate model variable selection. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software (SPSS Inc).

Results

General findings:

The SAGER guidelines and statistical analysis were applied to a total of 101 articles, which fulfilled the criteria and were included in the analysis (Figure 2). Among the corresponding authors, 73% were males and 28% were females. When examining the descriptive data on funding, we found that 4%, 25%, 25%, 14%, 2% and 30% of the studies were self-funded, funded by an institution, federally funded, industry or privately funded, were both federal and institutionally funded and were not funded or did not report their funding source, respectively. Table 2 shows the paper allocation to different journals in percentages. The majority of the papers were published in Journal of Clinical Periodontology (12%), Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy (10%), Journal of Periodontology (9%), Journal of Periodontal Research (6%).

Table 2 –

Paper percentage allocated to each journal

| Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 12% |

| Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy | 10% |

| Journal of Periodontology | 9% |

| Journal of Periodontal Research | 6% |

| Clinical Oral Investigations | 4% |

| International Journal of Dental Hygiene | 4% |

| Brazilian Dental Journal | 3% |

| Indian Journal of Dental Research | 3% |

| International Journal of Periodontics and Restorative Dentistry | 3% |

| Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice | 3% |

| Journal of Investigative and clinical dentistry | 3% |

| Oral Diseases | 3% |

| Acta Odontologica Scandinavica | 2% |

| BMC Oral Health | 2% |

| International Journal of Envrionmental Research and Public Health | 2% |

| Journal of Applied Oral Science | 2% |

| Journal of Biological regulators and homeostatic agents | 2% |

| Lasers in Medical Science | 2% |

| Photobiomodulation, Photomedicine and Laser Surgery | 2% |

| Quintessence International | 2% |

| Journal of Dentistry | 1% |

| American Journal of Dentistry | 1% |

| Australian Dental Journal | 1% |

| Beneficial Microbes | 1% |

| Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome | 1% |

| Growth Factors | 1% |

| Infectious Disorders | 1% |

| Inflammopharmacology | 1% |

| JDR Clinical and Translational Research | 1% |

| Journal of American College of Nutrition | 1% |

| Journal of Dental Hygiene | 1% |

| Journal of Dental Research | 1% |

| Journal of Ethnopharmacology | 1% |

| Journal of International Medical Research | 1% |

| Journal of Invest Clin Dent | 1% |

| Journal of Stomatology Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | 1% |

| Journal of the American College of Nutrition | 1% |

| Lasers in Surgery and Medicine | 1% |

| Minerva Medica | 1% |

| Minerva Stomatologica | 1% |

| Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice | 1% |

| Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences | 1% |

There were two single sex/gender studies. One article included only females (Anusha et al., 2019), and another included only males (AlAhmari, Ahmed, Al-Kheraif, Javed, & Akram, 2019). Eleven trials did not report the percentage of females in the study, although they included both sexes. Excluding the single sex studies (AlAhmari et al., 2019), the percentage of enrolled females ranged between 30%- 94% of the study populations. More specifically, in 26 studies female participants represented less than 50% of the study population, while in ten studies females represented less than 40% of the study participants. In addition, 52 out of the 101 articles excluded breast-feeding/lactating patients while the rest did not.

We also examined the use of gender or sex terminology in the included manuscripts. This analysis revealed that 38 studies used gender terms (women and men), 20 used sex terms (female and male), eight used the terms interchangeably, while 35 did not use any sex or gender terms at all throughout the manuscript.

Inter-rater Analysis: Cohen’s k-statistical analysis revealed a range of agreement per item of 80-100%. The remaining disagreements were resolved after discussion with the senior author.

SAGER checklist findings:

Overall, fourteen items of SAGER guidelines were included in the analysis. Detailed data per study is presented in the Amendment. However, only the single sex studies required the additional single-sex related item per SAGER guidelines (27)(28). Therefore, only for the two single sex studies, we conducted a 15-SAGER item analyses.

The overall item fulfillment (OSS) ranged between 0-7 items with an average of 1.9 items (Table 3). Therefore, we found poor guideline adherence in all items showing low percentage of fulfillment, and some items showed no fulfillment. Our results showed that studies did not report, interpret, or discuss results according to gender or sex.

Table 3:

SAGER item fulfillment for each article

| Item | Item section | Number of articles fulfilled this item |

Fulfillment percentage for each item (%) |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title and Abstract | Do the title or abstract explain if results of the study are to be applied to only one sex or gender? | 1 | 1% | |

| Background/Introduction | 1. Are the terms sex and gender used in the background? | 4 | 4% | |

| 2. Are sex/gender identified as relevant or not in the research question, hypothesis, or objective? | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3. Does background discuss why sex/gender differences may be expected? | 0 | 0 | ||

| Criteria for inclusion-exclusion | Do the inclusion-exclusion criteria consider sex-gender differences? | 1 | 1% | |

| Do they specifically exclude pregnant females? | 80 | 79% | ||

| Methods | 1. Is the number of female/male subjects reported? | 90 | 89% | |

| 2. What is the % of females in the study? | 89 | 88% | ||

| 3. If only one sex was included, is it discussed why? | 1 | 50% | Among the two single sex studies, only one discussed the rationale | |

| Results and Analysis | 1. Did the study extract data by sex? | 0 | 0 | |

| 2. Were any subgroup analysis by sex completed? | 3 | 3% | ||

| 3. Do results distinguish between findings for females/males? | 4 | 4% | ||

| Discussion and Conclusion | 1. Do they report conclusions that are different for women and men? | 3 | 3% | |

| 2. If adverse events are reported, is information sex-disaggregated? | 0 | 0 | 54 RCTs reported adverse events No adverse event results were disaggregated | |

| 3. Does the study address sex/gender implications for clinical practice or research? | 1 | 1% | Only one study addressed sex/gender implications | |

| 4. If no analysis by sex/gender was performed is it explained why? | 3 | 3% |

Title and Abstract:

Only 1 article (1%) fulfilled the item “Do the title or abstract explain if results of the study are to be applied to only one sex or gender?”

Background/Introduction:

While 4 articles (4%) fulfilled the item: “Are the terms sex and gender used in the background?”, no articles fulfilled the items: “Are sex/gender identified as relevant or not in the research question, hypothesis, or objective?” and “Are sex/gender identified as relevant or not in the research question, hypothesis, or objective?”

Criteria for inclusion-exclusion:

Only one article (1%) fulfilled the item: “Do the inclusion-exclusion criteria consider sex-gender differences?” In addition, twenty of the included studies did not specifically report the exclusion of pregnant patients, while 80 studies excluded pregnant patients with no differences between 2018-2019 (p=0.127).

Methods:

Only two items showed high fulfillment “Is the number of female/male subjects reported?” and “What is the percentage of female in the study?” (89% and 88% respectively). The item ‘If only one sex was included, is it discussed why?’ was fulfilled 50%. Given that there were only two studies included in this assessment (27)(28), only one of these two studies reported the rationale for a single sex study.

Results and Analysis:

Three items were evaluated in the Result section. While, none of the studies fulfilled the item “Did the study extract data by sex?”, three papers completed a subgroups analysis by sex. Finally, only four papers distinguished and presented the results between findings for females and males.

Discussion and Conclusion:

3% of the studies pointed out sex differences in their conclusions. One study (1%) addressed sex/gender implications for clinical practice and research. Three studies (3%) attempted to justify the absence of sex/gender analysis. More than half of the trials (54 trials) reported adverse events only. None of the studies sex-disaggregated information on adverse events.

Comparison of SAGER adherence (per item analysis) as a function of time:

Forty-seven articles were published in 2018, and 54 articles were published in 2019. Article OSS range in 2018 was 0-7, compared to 0-6 in 2019. Individual SAGER item fulfillment for each year was demonstrated in Table 4. The Mann-Whitney U test comparing the overall difference in item fulfillment between the two years showed no statistically significant difference (p=0.204). Table 5 demonstrated each item difference between the 2 years. Although no statistically significant differences were noted, it is important to note the improving trend of item fulfillment from 2018 to 2019.

Table 4:

SAGER item fulfillment per article stratified by per year:

| Item | Item section | Number of articles fulfilled this sub- item 2018 |

Number of articles fulfilled this sub- item 2019 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title and Abstract | Do the title or abstract explain if results of the study are to be applied to only one sex or gender? | 0 | 1 | 0.204 |

| Background/Introduction | 1. Are the terms sex and gender used in the background? | 2 | 2 | 0.204 |

| 2. Are sex/gender identified as relevant or not in the research question, hypothesis, or objective? | 0 | 0 | n/a | |

| 3. Does background discuss why sex/gender differences may be expected? | 0 | 0 | n/a | |

| Criteria for inclusion-exclusion | Do the inclusion-exclusion criteria consider sex-gender differences? | 0 | 1 | 0.204 |

| Do they specifically exclude pregnant females? | 41 | 39 | 0.138 | |

| Methods | 1. Is the number of female/male subjects reported? | 43 | 47 | 0.589 |

| 2. What is the % of females in the study? | 43 | 46 | 0.589 | |

| 3. If only one sex was included, is it discussed why? | n/a | 1 | n/a Ŧ | |

| Results and Analysis | 1. Did the study extract data by sex? | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| 2. Were any subgroup analysis by sex completed? | 1 | 2 | 0.589 | |

| 3. Do results distinguish between findings for females/males? | 1 | 3 | 0.589 | |

| Discussion and Conclusion | 1. Do they report conclusions that are different for women and men? | 1 | 2 | 0.589 |

| 2. If adverse events are reported, is information sex-disaggregated? | 0 | 0 | n/a | |

| 3. Does the study address sex/gender implications for clinical practice or research? | 1 | 0 | 0.204 | |

| 4. If no analysis by sex/gender was performed is it explained why? | 0 | 3 | 0.704 |

One-gender studies published in 2019.

Table 5:

SAGER item fulfillment per article per year

| Item | Item section | Number of articles fulfilled this sub- item 2018 |

Number of articles fulfilled this sub- item 2019 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title and Abstract | Do the title or abstract explain if results of the study are to be applied to only one sex or gender? | 0 | 1 | 0.204 |

| Background/Introduction | 1. Are the terms sex and gender used in the background? | 2 | 2 | 0.204 |

| 2. Are sex/gender identified as relevant or not in the research question, hypothesis, or objective? | 0 | 0 | n/a | |

| 3. Does background discuss why sex/gender differences may be expected? | 0 | 0 | n/a | |

| Criteria for inclusion-exclusion | Do the inclusion-exclusion criteria consider sex-gender differences? | 0 | 1 | 0.204 |

| Methods | 1. Is the number of female/male subjects reported? | 43 | 47 | 0.589 |

| 2. What is the % of women in the study? | 43 | 46 | 0.589 | |

| 3. If only 1 gender was included is it discussed why? | n/a | 1 | n/a Ŧ | |

| Results and Analysis | 1. Did the study extract data by sex? | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| 2. Were any subgroup analysis by sex completed? | 1 | 2 | 0.589 | |

| 3. Do results distinguish between findings for females/males? | 1 | 3 | 0.589 | |

| Discussion and Conclusion | 1. Do they report conclusions that are different for women and men? | 1 | 2 | 0.589 |

| 2. If adverse effects are reported, is information sex-disaggregated? | 0 | 0 | n/a | |

| 3. Does the study address sex/gender implications for clinical practice or research? | 1 | 0 | 0.204 | |

| 4. If no analysis by sex/gender was performed is it explained why? | 0 | 3 | 0.704 |

Bivariate Correlation analyses:

For the exploratory bivariate association between OSS and related variables, we applied non-parametric Spearman correlation statistics. We found no significant correlation between SAGER OSS and gender of corresponding author (r=0.051, p= 0.623), year of publications (r=0.007 and p=0.947), and funding source (r=−0.153, p=0.133). However, we found a significant but negative correlation with journal impact factor (r=−0.253, p=0.026). In other words, the higher the impact factor, the lower the SAGER OSS. The results of Spearman correlation statistics did not allow for a further multivariate regression model to assess predictors of adherence to SAGER guidelines.

Discussion and Conclusion:

This was the first study to examine the level of compliance of periodontitis-related RCTs to the SAGER guidelines with focus on sex/gender. We found that there was an overall lack of adherence to the SAGER guidelines in inclusion, analysis, and reporting of the inclusion of sex/gender in periodontitis-related RCTs. Sex and gender differences have been frequently disregarded in research design, study implementation and scientific reporting in the literature (Liu & Mager, 2016). This oversight has limited the generalizability of research findings and their applicability to clinical practice, in particular for female patients.

In medicine, several recent studies addressing enrollment in clinical research have reported female under-representation and limited sex-based analysis signifying an overall inadequate adherence to NIH policies. As a matter of fact, a systematic review of 395 clinical studies examining HIV drugs (D), vaccines (V) and curative strategies (CS) (Curno et al., 2016) found that females represented 19.2% (D), 38% (V), and 11% (CS) of participants with a greater number of female participants in non-NIH/private noncommercial funded trials (Curno et al., 2016). Ironically, although females represent almost half of the HIV populations, they remained under-represented in clinical trials (Curno et al., 2016). Similar results in oncology clinical trials confirmed female under-represented in melanoma (35%), lung cancer (39%) and pancreatic cancer (40%) trials(31). With the focus on reporting quality, a systematic review of 1,303 RCTs in the top five American surgical journals revealed that only 38.1% of the studies reported data by sex, 33.2% analyzed data by sex, and 22.9% included discussion of sex-based results (Mansukhani et al., 2016). Similarly, Foulkes et al. reported that after 15 years of monitoring the inclusion of females in clinical trials, females represented only 37% of enrollment and only 28% of the publications made a reference to sex specific results (Foulkes, 2011).

Regarding the adherence and considerations of sex and gender guidelines, a recent systematic review of sex/gender analysis of trials published in high impact medical journals revealed that 39% reported balanced enrollment and only 20% analyzed their data by sex, while the interaction between sexes and the treatment were only included in the outcome/discussion in 10% of the articles (Phillips & Hamberg, 2016).

In agreement with our results, poor adherence to the SAGER guidelines was confirmed by other investigators (Lopez-Alcalde et al., 2019). Although 10% of the publications stated a planned sex-based analysis, interestingly only 3% completed the analysis and only 3% considered sex findings in their conclusion (Lopez-Alcalde et al., 2019). Additional assessment against the SAGER guidelines from the Central European Journal of Medicine revealed that among 195 publications, only 4 included the term “sex” in the title, 62 in the abstract, 48 mentioned potential implications of sex on the study results. More importantly, none of the studies reported on the relevance of sex differences in the design of the study, and none of the articles gave a rationale for not conducting sex analysis (Rasky et al., 2017).

While our analysis was restricted to the adherence to the SAGER guidelines, it is important to recognize that other studies addressed compliance with the federal guidelines of sex/gender inclusion and enrollment in RCTs and showed that female patients comprised 37% of RCT populations (Geller, Adams, & Carnes, 2006). Eighty-seven percent of the included papers did not report outcomes stratified by sex or sex as a covariate in modeling (Geller et al., 2006). In their consecutive work, Geller and co-workers found that only 36% of the RCTs reported research performed by sex inclusion or provided explanation as to why the research was not sex sensitive, and only 25% of the studies reported sex specific results (Geller, Koch, Pellettieri, & Carnes, 2011). Additionally, they showed that 15% of the studies enrolled less than 30% females with no difference in reporting based on sex of authors. Furthermore, only one of the fourteen journals (i.e. Journal of American College of Cardiology) included specific guidelines on sex analysis (Geller et al., 2018). Recently, the lack of adherence to sex and gender guidelines has been observed in the analysis of COVID-19 RCTs. Specifically, among over 2,400 COVID-19 trials registered on clinicaltrials.gov, only 16.7% mentioned sex/gender as recruitment criterion and only 4.3% alluded to sex/gender in the analytical plan (Brady, Nielsen, Andersen, & Oertelt-Prigione, 2021) leading to the lack of sex-disaggregated results.

Our paper on the RCT compliance to SAGER guidelines had several strengths. First, to standardize methods and minimize methodological bias, we used validated and well accepted guidelines (SAGER) and incorporated all applicable items. In addition, we evaluated the appropriate use of sex and gender terms in addition to funding source, author gender, inclusion of pregnancy and breastfeeding participants. An inherited limitation deriving from the binary gender options in the included studies prevented us from examining gender minority populations and enrollment rates. We decided to narrow down the RCT selection to 2018-2019 to allow for the publication of trials conducted following the establishment of the SAGER guidelines. To minimize selection bias, we included all trials within the timeframe of 2018-2019. Following this first meta-research study, our team might expand the time inclusion criterion to examine more recently published literature.

In summary, while the SAGER guidelines have been widely accepted and translated into six languages (Peters et al., 2021), we observed that in regards to periodontitis-related RCTs published in 2018 and 2019, adherence to SAGER guidelines was poor. Specifically, we found that RCTs lacked sex/gender disaggregated results, which limit the understanding of sex/gender specific outcomes following periodontitis-related interventions. It is imperative that oral health providers are made aware of the sex and gender bias contained in the evidence, and, therefore, take this under consideration in their clinical decision making. The results of the present study showed that researchers would need to recognize the significance of sex/gender as biologic and socio-behavioral factors and to incorporate them in the data analysis and reporting. Furthermore, other stake holders including funding organization and journal editors should take it upon themselves to uphold the SAGER guidelines and recommendations with the goal to improve sex/gender reporting in published research.

Clinical Relevance:

Scientific Rationale:

There is an oversight of sex and gender differences in biomedical science reporting. Within the last decades, scientific and funding organizations have developed policies and guidelines to support appropriate use of the terms and to reinforce sex/gender data disaggregation.

Principal Findings:

The results showed poor adherence of periodontitis-related RCTs to the SAGER guidelines, which was negatively associated with the journal impact factor.

Practical Implications:

There was a wide range of female enrollment and poor adherence to SAGER guidelines in periodontitis-related RCTs. As a result, we observed a lack of sex/gender data disaggregation that might affect the understanding of therapeutic differences between sexes/genders in periodontitis-related trials.

Conflict of Interest and Source of Funding Statement:

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest. The study was funded by NIH/NIDCR DE027410.

Appendix

Table:

Metric Analysis per Article:

| Journal metrics | Article metrics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | Journal | Impact Factor |

Funding | Author’s Sex* |

% of female enrollment |

OSS |

| Alahmari et el. | 2019 | Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy | 2.89 | Institutional | Male | 0 | 2/15 Ŧ |

| Al-Shammari et al. | 2018 | Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice | n/a | No funding | Male | 58 | 2/14 |

| Alvarenga et al. | 2019 | Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy | 2.89 | Federal | Male | n/a | 0/14 |

| Angst et al. | 2019 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | Federal | Female | 55 | 5/14 |

| Anusha et al. | 2019 | Indian Journal of Dental Research | n/a | No funding | Male | 100 | 6/15 Ŧ |

| Araujo et al. | 2019 | Journal of Periodontology | 3.74 | Federal | Male | 58 | 2/14 |

| Asimakopoulou et al. | 2019 | Journal of Periodontology | 3.74 | Institutional | Male | 56 | 2/14 |

| Babaei et al. | 2018 | Journal of American College of Nutrition | 2.3 | Institutional | Male | 47 | 2/14 |

| Barbosa et al. | 2018 | Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy | 2.89 | Federal | Female | 67 | 2/14 |

| Bazyar et al. | 2018 | Inflammopharmacology | 3.24 | Institutional | Male | 62 | 2/14 |

| Bechara et al. | 2018 | Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy | 2.89 | Federal | Male | 94 | 2/14 |

| Bodhare et al. | 2018 | Journal of Periodontology | 3.74 | No funding | Female | 45 | 2/14 |

| Borecki et al. | 2019 | Lasers in Surgery and Medicine | 3.02 | No funding | Female | 46 | 2/14 |

| Cadore et al. | 2018 | Journal of Periodontology | 3.74 | Federal | Male | 44 | 2/14 |

| Cirino et al. | 2019 | Brazilian Dental Journal | No funding | Male | 94 | 2/14 | |

| Ciurescu et al. | 2019 | Quintessence International | 1.46 | No funding | Male | 52 | 2/14 |

| de Melo Soares et al. | 2019 | Clinical Oral Investigations | 2.81 | No funding | Male | 70 | 2/14 |

| Djurkin et al. | 2019 | Quintessence International | 1.46 | Industrial/private | Male | 53 | 2/14 |

| Dos Santos et al. | 2019 | Lasers in Medical Science | 2.34 | No funding | Male | 74 | 2/14 |

| El-Sharkawy et al. | 2018 | Journal of Periodontal Research | 2.93 | Institutional | Male | 45 | 2/14 |

| Farooqui et al. | 2019 | Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice | n/a | No funding | Female | n/a | 0/14 |

| Ferrarotti et al. | 2018 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | Institutional | Male | 52 | 2/14 |

| Fjeld et al. | 2018 | Acta Odontologica Scandinavica | 1.57 | Institutional | Female | 76 | 2/14 |

| Gandhi et al. | 2019 | International Journal of Periodontics and Restorative Dentistry | 1.51 | No funding | Male | n/a | 2/14 |

| Giammarinaro et al. | 2018 | Minerva Stomatologica | n/a | No funding | Male | 42 | 2/14 |

| Gkatzonis et al. | 2018 | Clinical Oral Investigations | 2.81 | No funding | Male | 67 | 2/14 |

| Gorski et al. (2) | 2018 | Clinical Oral Investigations | 2.81 | Self-funding | Male | 67 | 2/14 |

| Gorski et al. (3) | 2019 | Clinical Oral Investigations | 2.81 | Self-funding | Male | 67 | 2/14 |

| Graziani et al. | 2018 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | Industrial/private | Male | 53 | 2/14 |

| Graziani et al. (2) | 2018 | Journal of Periodontology | 3.74 | Federal and Institutional | Male | 62 | 2/14 |

| Grzech-Lesniak et al. | 2019 | Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy | 2.89 | Institutional | Male | 62.5 | 2/14 |

| Grzech-Leśniak et al. (2) | 2018 | Lasers in Medical Science | 2.34 | No funding | Male | 57 | 2/14 |

| Harmouche et al. | 2019 | Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy | 2.89 | Industrial/private | Male | 61 | 2/14 |

| Hasan et al. | 2019 | Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences | 0.56 | No funding | Male | n/a | 0/14 |

| Hill et al. | 2019 | Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy | 2.89 | Industrial/private | Male | 85 | 3/14 |

| Hong et al. | 2019 | BMC Oral Health | 1.91 | Industrial/private | Male | 67 | 3/14 |

| Husejnagic et al. | 2019 | Journal of Periodontology | 3.74 | Institutional | Female | n/a | 0/14 |

| Invernici et al. | 2018 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | Federal | Male | n/a | 0/14 |

| Ipshita et al. | 2018 | Journal of Investigative and clinical dentistry | n/a | Industrial/private | Female | 52 | 2/14 |

| Issa et al. | 2019 | Journal of Periodontal Research | 2.93 | Self-funding | Male | 70 | 2/14 |

| Ivanaga et al. | 2019 | Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy | 2.89 | No funding | Female | 32 | 2/14 |

| Javid et al. | 2019 | Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome | n/a | Institutional | Female | n/a | 0/14 |

| Karthikeyan et al. | 2018 | Photobiomodulation, Photomedicine and Laser Surgery | n/a | No funding | Female | 40 | 2/14 |

| Kaur et al. | 2019 | Infectious Disorders | n/a | No funding | Female | 31 | 2/14 |

| Kavyamala et al. | 2018 | International Journal of Periodontics and Restorative Dentistry | 1.51 | No funding | Male | 33 | 2/14 |

| Kerdar et al. | 2019 | Journal of Ethnopharmacology | 3.69 | Institutional | Male | n/a | 0/14 |

| Killeen et al. | 2018 | Journal of Dental Hygiene | n/a | Industrial/private | Male | 31 | 2/14 |

| Kizikldag et al. | 2018 | Growth Factors | 1.54 | Institutional | Male | n/a | 0/14 |

| Kocher et al. | 2019 | Journal of Dental Research | 4.91 | Institutional | Male | 50 | 2/14 |

| Kruse et al. | 2018 | Journal of Periodontology | 3.74 | Industrial/private | Female | 41 | 2/14 |

| Kurian et al. | 2018 | Journal of Investigative and clinical dentistry | n/a | Institutional and Industrial/private | Female | 48 | 2/14 |

| Laky et al. | 2018 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | No funding | Female | 47 | 7/14 |

| Laleman et al. | 2018 | Journal of Periodontal Research | 2.93 | No funding | Male | 38 | 2/14 |

| Liaw et al. | 2019 | Australian Dental Journal | 1.4 | Institutional | Female | 60.5 | 2/14 |

| Lin et al. | 2019 | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 2.85 | Federal | Female | 56 | 2/14 |

| Marconcini et al. | 2019 | Journal of Investigative and clinical dentistry | n/a | No funding | Female | 60 | 2/14 |

| Mastrangelo et al. | 2018 | Journal of Biological regulators and homeostatic agents | 1.51 | No funding | Male | 30 | 2/14 |

| Mauri-Obradors et al. | 2018 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | Institutional | Male | 59 | 2/14 |

| Meghil et al. | 2019 | Oral Diseases | 2.61 | Federal | Male | 48 | 2/14 |

| Montenegro et al. | 2019 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | Federal and Institutional | Male | 74 | 2/14 |

| Morales et al. | 2018 | Journal of Applied Oral Science | 1.8 | Federal | Male | 55 | 2/14 |

| Mourao et al. | 2019 | Brazilian Dental Journal | No funding | Male | 55 | 2/14 | |

| Mummolo et al. | 2019 | Journal of Biological regulators and homeostatic agents | 1.51 | No funding | Male | 50 | 2/14 |

| Nakano et al. | 2019 | Journal of Periodontal Research | 2.93 | Industrial/private | Male | 32 | 4/14 |

| Nguyen et al. | 2018 | Journal of Periodontology | 3.74 | Industrial/private | Male | 62 | 2/14 |

| Nishioka et al. | 2019 | Journal of Dentistry | 3.24 | Federal | Male | 62 | 2/14 |

| Oliveiera et al. | 2019 | Brazilian Dental Journal | Federal | Male | 56 | 2/14 | |

| Pankaj et al. | 2018 | Journal of Periodontology | 3.74 | Institutional | Male | 51 | 2/14 |

| Pelekos et al. | 2019 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | No funding | Male | 67 | 2/14 |

| Petrovic et al. | 2018 | International Journal of Dental Hygiene | 1.23 | Federal | Female | 60 | 2/14 |

| Pilloni et al. | 2018 | Minerva Medica | 3.03 | No funding | Female | 40 | 2/14 |

| Pirebas et al. | 2018 | Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice | 0.63 | Institutional | Male | 59 | 2/14 |

| Quintero et al. | 2018 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | Federal | Male | 62 | 2/14 |

| Raghava et al. | 2019 | Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice | Federal | Female | 50 | 2/14 | |

| Ramiro et al. | 2018 | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 2.85 | Federal | Male | 61 | 2/14 |

| Rayyan et al. | 2018 | Journal of Investigative and clinical dentistry | No funding | Female | n/a | 0/14 | |

| Rossi et al. | 2019 | Indian Journal of Dental Research | Federal | Female | 72 | 2/14 | |

| Saffi et al. | 2018 | Oral Diseases | 2.61 | Federal | Male | 75 | 2/14 |

| Saito et al. | 2019 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | Industrial/private | Female | 59 | 2/14 |

| Serban et al. | 2019 | JDR Clinical and Translational Research | Federal | Female | 71 | 3/14 | |

| Sethi et al. | 2019 | Indian Journal of Dental Research | Federal | Male | 53 | 2/14 | |

| Seydanur Dengizek et al. | 2019 | Journal of Applied Oral Science | 1.8 | Institutional | Female | 43 | 2/14 |

| Shah et al. | 2019 | International Journal of Periodontics and Restorative Dentistry | 1.51 | No funding | Male | 65 | 2/14 |

| Sijari et al. | 2019 | International Journal of Dental Hygiene | 1.23 | Federal | Male | 60 | 2/14 |

| Soares et al. | 2019 | American Journal of Dentistry | 0.96 | Industrial/private and Institutional | Male | 60 | 2/14 |

| Stenman et al. | 2018 | International Journal of Dental Hygiene | 1.23 | Federal | Female | 73 | 2/14 |

| Taleghani et al. | 2018 | Journal of Stomatology Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | 1.15 | No funding | Male | 67 | 2/14 |

| Tasdemir et al. | 2019 | Oral Diseases | 2.61 | Self-funding | Male | 50 | 2/14 |

| Theodoro et al. | 2018 | Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy | 2.89 | Federal | Male | 32 | 2/14 |

| Theodoro et al. (2) | 2019 | Beneficial Microbes | 3.37 | Federal | Male | 44 | 2/14 |

| Tongtawee et al. | 2019 | Journal of International Medical Research | 1.29 | Institutional | Female | 49 | 2/14 |

| Tsang et al. | 2018 | Journal of Periodontal Research | 2.93 | Institutional | Male | n/a | 0/14 |

| Tsobgny-Tsague et al. | 2018 | BMC Oral Health | 1.91 | No funding | Male | 54 | 2/14 |

| Van Dijk et al. | 2018 | International Journal of Dental Hygiene | 1.23 | Institutional | Male | 25 | 2/14 |

| Vergnes et al. | 2018 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | Federal | Male | 44 | 2/14 |

| Vitt et al. | 2019 | ACTA Odontologica Scandinavica | 1.57 | Institutional | Male | 50 | 4/14 |

| Vohra et al. | 2018 | Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy | 2.89 | Institutional | Male | 17 | 3/14 |

| Yashima et al. | 2019 | Journal of Periodontal Research | 2.93 | Industrial/private | Male | 52 | 2/14 |

| Zare Javid et al. | 2018 | Journal of the American College of Nutrition | 2.3 | Institutional | Male | 65 | 2/14 |

| Zengin et al. | 2019 | Photobiomodulation, Photomedicine and Laser Surgery | Institutional | Male | 50 | 2/14 | |

| Zhou et al. | 2019 | Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 5.24 | Federal | Male | 59 | 2/14 |

n/a = not available.

Sex of corresponding author.

Single sex studies

Bibliography

- AlAhmari F, Ahmed HB, Al-Kheraif AA, Javed F, & Akram Z (2019). Effectiveness of scaling and root planning with and without adjunct antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the treatment of chronic periodontitis among cigarette-smokers and never-smokers: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther, 25, 247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anusha D, Chaly PE, Junaid M, Nijesh JE, Shivashankar K, & Sivasamy S (2019). Efficacy of a mouthwash containing essential oils and curcumin as an adjunct to nonsurgical periodontal therapy among rheumatoid arthritis patients with chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled trial. Indian J Dent Res, 30(4), 506–511. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_662_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady E, Nielsen MW, Andersen JP, & Oertelt-Prigione S (2021). Lack of consideration of sex and gender in COVID-19 clinical studies. Nat Commun, 12(1), 4015. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24265-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook CG, Jarvis SN, & Newman CG (1977). Linear growth of children with limb deformities following exposure to thalidomide in utero. Acta Paediatr Scand, 66(6), 673–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1977.tb07969.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang N, Hurwitz S, Ridker PM, & Serhan CN (2006). Aspirin has a gender-dependent impact on antiinflammatory 15-epi-lipoxin A4 formation: a randomized human trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 26(2), e14–17. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000196729.98651.bf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarivate Analytics. (2019). Journal Citation Reports. Science Edition. Retrieved from https://jcr.clarivate.com/jcr/home?app=jcr&referrer=target%3Dhttps:%2F%2Fjcr.clarivate.com%2Fjcr%2Fhome&Init=Yes&authCode=null&SrcApp=IC2LS [Google Scholar]

- Curno MJ, Rossi S, Hodges-Mameletzis I, Johnston R, Price MA, & Heidari S (2016). A Systematic Review of the Inclusion (or Exclusion) of Women in HIV Research: From Clinical Studies of Antiretrovirals and Vaccines to Cure Strategies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 71(2), 181–188. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Castro P, Heidari S, & Babor TF (2016). Sex And Gender Equity in Research (SAGER): reporting guidelines as a framework of innovation for an equitable approach to gender medicine. Commentary. Ann Ist Super Sanita, 52(2), 154–157. doi: 10.4415/ANN_16_02_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas RH, Unger EF, & Temple R (2013). Zolpidem and driving impairment--identifying persons at risk. N Engl J Med, 369(8), 689–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1307972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. (1977). Guidance for Industry. 1977: Public health Service Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/media/71495/download

- Food and Drug Administration. (2014). FDA Action Plan to Enhance the Collection and Availability of Demographic Subgroup Data. Rockville, MD: Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/media/89307/download [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes MA (2011). After inclusion, information and inference: reporting on clinical trials results after 15 years of monitoring inclusion of women. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 20(6), 829–836. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller SE, Adams MG, & Carnes M (2006). Adherence to federal guidelines for reporting of sex and race/ethnicity in clinical trials. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 15(10), 1123–1131. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller SE, Koch A, Pellettieri B, & Carnes M (2011). Inclusion, analysis, and reporting of sex and race/ethnicity in clinical trials: have we made progress? J Womens Health (Larchmt), 20(3), 315–320. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller SE, Koch AR, Roesch P, Filut A, Hallgren E, & Carnes M (2018). The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: A Study to Evaluate Compliance With Inclusion and Assessment of Women and Minorities in Randomized Controlled Trials. Acad Med, 93(4), 630–635. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genderize.io. Retrieved from https://genderize.io/#overview

- Goldberg D (2009). The case for Eliminating Disparities in Clinical Trials. J Cancer Educ, 24(2 Suppl), S34–38. doi: 10.1080/08858190903400484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther EA, H. A., Kelan EK. (2018). Gender vs. Sex [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky O, Springer KW, & Hunting G (2018). Beyond sex and gender difference in funding and reporting of health research. Res Integr Peer Rev, 3, 6. doi: 10.1186/s41073-018-0050-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari S, Babor TF, De Castro P, Tort S, & Curno M (2016). Sex and Gender Equity in Research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res Integr Peer Rev, 1, 2. doi: 10.1186/s41073-016-0007-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu KA, & Mager NA (2016). Women's involvement in clinical trials: historical perspective and future implications. Pharm Pract (Granada), 14(1), 708. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2016.01.708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loe H, Anerud A, Boysen H, & Morrison E (1986). Natural history of periodontal disease in man. Rapid, moderate and no loss of attachment in Sri Lankan laborers 14 to 46 years of age. J Clin Periodontol, 13(5), 431–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01487.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Alcalde J, Stallings E, Cabir Nunes S, Fernandez Chavez A, Daheron M, Bonfill Cosp X, & Zamora J (2019). Consideration of sex and gender in Cochrane reviews of interventions for preventing healthcare-associated infections: a methodology study. BMC Health Serv Res, 19(1), 169. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4001-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansukhani NA, Yoon DY, Teter KA, Stubbs VC, Helenowski IB, Woodruff TK, & Kibbe MR (2016). Determining If Sex Bias Exists in Human Surgical Clinical Research. JAMA Surg, 151(11), 1022–1030. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanez A (2017). Visualizing Sex as a Spectrumo Title [Internet]. Retrieved from Available from: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/sa-visual/visualizing-sex-as-a-spectrum/ Revitalization Act of 1993, (1993). [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health. (1994). NIH Guidelines on the Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research [Press release]. Retrieved from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not94-100.html

- National Institute of Health. (2001). NIH Policy and guidelines on the Inclusion of Women and minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research. Bethesda, MA: NIH; Retrieved from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-02-001.html [Google Scholar]

- Norman JL, Fixen DR, Saseen JJ, Saba LM, & Linnebur SA (2017). Zolpidem prescribing practices before and after Food and Drug Administration required product labeling changes. SAGE Open Med, 5, 2050312117707687. doi: 10.1177/2050312117707687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Human Research Protections. (2014). The Belmont Report. Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Retrieved from Washington, DC: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/index.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Research on Women’s Health. (2015). Report of the Advisory Committee on Research on Women’s Health, Fiscal Years 2013-2014: Office of Research on Women’s Health and NIH Support for Research on Women’s Health. Bethesda, MA: Retrieved from https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sites/orwh/files/docs/1-Introduction-ACRWH-Biennial-Report-FY13-14_3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, … Moher D (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg, 88, 105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh A, Fadiran EO, Uhl K, & Throckmorton DC (2011). Adverse effects in women: implications for drug development and regulatory policies. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol, 4(4), 453–466. doi: 10.1586/ecp.11.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters SAE, Babor TF, Norton RN, Clayton JA, Ovseiko PV, Tannenbaum C, & Heidari S (2021). Fifth anniversary of the Sex And Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines: taking stock and looking ahead. BMJ Glob Health, 6(11). doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati HM, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Suh JJ, Dackis CA, Oslin DW, & O'Brien CP (2008). Gender differences with high-dose naltrexone in patients with co-occurring cocaine and alcohol dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat, 34(4), 378–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SP, & Hamberg K (2016). Doubly blind: a systematic review of gender in randomised controlled trials. Glob Health Action, 9, 29597. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.29597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Service Task Force. (1985). Women's health. Report of the Public Health Service Task Force on Women's Health Issues. Public Health Rep, 100(1), 73–106. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3918328 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasky E, Waxenegger A, Groth S, Stolz E, Schenouda M, & Berzlanovich A (2017). Sex and gender matters : A sex-specific analysis of original articles published in the Wiener klinische Wochenschrift between 2013 and 2015. Wien Klin Wochenschr, 129(21–22), 781–785. doi: 10.1007/s00508-017-1280-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiker CA, & Weinberg AD (2009). Policies to address disparities in clinical trials: the EDICT Project. J Cancer Educ, 24(2 Suppl), S39–49. doi: 10.1080/08858190903400500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). Gender and Health [Internet]. Retrieved from Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_1