Abstract

An enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strain of serotype O114:H− that expressed both heat-labile and heat-stable enterotoxins and tested negative for colonization factors (CF) was isolated from a child with diarrhea in Egypt. This strain, WS0115A, induced hemagglutination of bovine erythrocytes and adhered to the enterocyte-like cell line Caco-2, suggesting that it may elaborate novel fimbriae. Surface-expressed antigen purified by differential ammonium sulfate precipitation and column chromatography yielded a single protein band with Mr 14,800 when resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (16% polyacrylamide). A monoclonal antibody against this putative fimbrial antigen was generated and reacted with strain WS0115A and also with CS1-, CS17-, and CS19-positive strains in a dot blot assay. Reactivity was temperature dependent, with cells displaying reactivity when grown at 37°C but not when grown at 22°C. Immunoblot analysis of a fimbrial preparation from strain WS0115A showed that the monoclonal antibody reacted with a single protein band. Electron microscopy and immunoelectron microscopy revealed fimbria-like structures on the surface of strain WS0115A. These structures were rigid and measured 6.8 to 7.4 nm in diameter. Electrospray mass-spectrometric analysis showed that the mass of the purified fimbria was 14,965 Da. The N-terminal sequence of the fimbria established that it was a member of the CFA/I family, with sequence identity to the amino terminus of CS19, a new CF recently identified in India. Cumulatively, our results suggest that this fimbria is CS19. Screening of a collection of ETEC strains isolated from children with diarrhea in Egypt found that 4.2% of strains originally reported as CF negative were positive for this CF, suggesting that it is biologically relevant in the pathogenesis of ETEC.

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is a common cause of traveler’s diarrhea and a leading cause of diarrhea and dehydration in children in developing countries (4, 38). ETEC virulence factors include heat-stable (ST) and heat-labile (LT) enterotoxins and colonization factors (CF), which work in concert to cause diarrhea (reviewed in reference 17). CFs are essential for ETEC to adhere to and colonize the mammalian small intestine (16). They may be fimbrial or nonfimbrial (8, 17), and most confer the ability to agglutinate erythrocytes in the presence of mannose (16). CF expression is usually thermoregulated, with expression at 37°C but not at 22°C, although exceptions have been reported (22, 36).

Over 20 human-specific and antigenically distinct ETEC CFs have been described, including colonization factor antigens (CFA), putative colonization factors (PCF), and coli surface antigens (CS) (reviewed in references 8 and 17). In many geographic areas, the most commonly identified CFs from human ETEC isolates include CFA/I, CFA/II, and CFA/IV (reviewed in reference 46). A number of other CFs have been identified and at least partially characterized. These include CFA/III, CS7, CS17, CS19, CS20, CS22, PCFO159, PCFO166, PCF2230, PCFO148, PCFO9, PCFO20, and PCF8786 (reviewed in references 8 and 17). Some CFs, such as CFA/I, possess a single fimbrial antigen. Other CFs appear to be composed of distinct protein subunits. For example, CFA/II is composed of CS3 alone or in combination with CS1 or CS2. Similarly, CFA/IV is composed of CS6 alone or in combination with CS4 or CS5.

A considerable proportion of ETEC strains do not appear to express a known CF (3, 32, 45). Given the importance of CFs in the pathogenesis of ETEC, it has been suggested that these strains either have lost the ability to express a known CF or express an unknown CF (42). In a recent epidemiological study of pediatric diarrhea in rural lower Egypt, approximately 70% of ETEC strains isolated from children with diarrhea did not produce a known CF (1, 34). This finding prompted us to screen diarrhea-associated CF-negative ETEC strains for novel CFs that may be common in this geographical region.

In the present study, we characterized such a CF associated with LTST- and ST-expressing ETEC from Egypt and a monoclonal antibody (MAb) that is reactive to an epitope shared with CS1 and CS17.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Use of animals.

In conducting the research described in this report, all aspects involving animal use were conducted in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act implementing instructions (9 CFR, subchapter A, parts 1 to 3), applicable U.S. Department of Defense regulations, and recognized standards relating to the care and use of laboratory animals.

Bacterial strains.

E. coli WS0115A (O114:H−/LTST:CF−), investigated in this study, was originally isolated from the stool of a 12-month-old Egyptian girl suffering from watery diarrhea (1, 23, 34). The stool was negative for other bacterial enteropathogens, rotavirus, Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium. WS0115A was analyzed for enterotoxin production by a GM1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (39, 40) and for CF expression by using MAbs against CFA/I, CS1, CS2, CS3, CFA/III, CS4, CS5, CS6, CS7, CS17, PCFO159, and PCFO166 in colony dot blot analysis (37, 43). ETEC E1392-75 (CS1+), E20738A (CS17+), and F595C (CS19+) were described previously (19, 43) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

ETEC strains used in this study

| Strain designation | Colonization factor | Source |

|---|---|---|

| WS0115A | Unknown | This study |

| E1392-75 | CS1 | A.-M. Svennerholm |

| E20738A | CS17 | A.-M. Svennerholm |

| F595C | CS19 | H. Sommerfelt |

Hemagglutination.

Bacterial strains were tested for mannose-resistant hemagglutination (MRHA) as previously described (10). Briefly, washed erythrocytes from human (group A), bovine, guinea pig, or chicken erythrocytes were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2) with or without 1% d-mannose. Bacterial cells (1010 CFU/ml) were mixed with equal volumes of erythrocyte suspensions on a glass slide, and hemagglutination was assessed visually within 2 min.

Adherence to human Caco-2 cells.

The cell adhesion test was performed as described previously (12, 44). Briefly, monolayers of differentiated Caco-2 cells were suspended in minimal essential medium (MEM; Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% nonessential amino acids, and grown in a 24-well tissue culture plates (Corning Glass Works, Corning, N.Y.) containing circular coverslips. The plates were incubated at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cultures were used at postconfluence after 14 days of incubation. For the adhesion test, cells were washed three times with serum-free MEM. A suspension of 104 bacteria/ml (grown on CFA agar) in MEM containing 0.5% d-mannose was prepared and divided into aliquots. A 1-ml volume of bacterial suspension was added to each monolayer well, and the plate was incubated for 3 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The plates were washed five times with sterile PBS (pH 7.2), fixed in 70% methanol for 15 min, and stained with 20% filtered Giemsa solution for 15 min. Washed coverslips were removed, air dried, and mounted on a glass slide. The percentage of cells with at least one adherent bacterium was calculated from observations of 10 random fields in three separate experiments.

Purification of fimbriae.

Fimbrial purification was performed as previously described (15). Briefly, strain WS0115A was grown in 1 liter of Casamino Acids-yeast extract broth with bile salts at 37°C for 24 h. The cells were harvested and sheared on ice with a Waring blender. Following passage through a 0.65-μm-pore-size filter, the filtrate was kept at 4°C for 3 days and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was refiltered. Ammonium sulfate was added to 20% saturation, the resulting precipitate was removed by centrifugation, and ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatant to achieve a final 40% saturation. The resultant precipitate was resuspended in 10 ml of 0.05 M phosphate buffer and then dialyzed for 24 h against the same buffer. This protein fraction, enriched for CF, was further purified on a DEAE-Sephadex A-50 column. The protein content of the final extract was determined by the method of Lowry et al. (29).

Gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

The purity and molecular weight of the fimbrial antigenic preparation from strain WS0115A were evaluated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (12% polyacrylamide) (26) or precast Tricine SDS-PAGE (16% polyacrylamide) (Novex, Encinitas, Calif.) as specified by the manufacturer (35). For immunoblot studies, fractionated material was transferred to nitrocellulose sheets as previously described (41). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubating strips in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Proteins immobilized on nitrocellulose sheets were reacted with the appropriate MAbs, and antibody-antigen complexes were detected by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) heavy-plus-light-chain (H+L) antisera in 0.1% BSA–0.05% Tween 20–PBS. Following a 2-h incubation at room temperature, 4-chloro-1-naphthol was added.

Polyclonal antibody and MAb production.

MAbs were produced by the scheme of De St. Groth and Scheidegger (13). Briefly, female BALB/c mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 4 μg of the purified fimbrial antigen in complete Freund’s adjuvant. The animals were boosted intravenously with 4 μg of the antigen only at 7 and 9 weeks after the initial inoculation. Four days after the last immunization, sera were collected and tested against the immunizing antigen and whole bacterial isolates by using ELISA and a dot blot assay, respectively. Splenocytes of immunized mice that had highly reactive polyclonal antisera were fused with the mouse myeloma cell line P3NS1 at a ratio of 1:5. After 10 days of incubation in hypoxanthine-aminopterin-thymidine (HAT) selective medium, stable hybridomas were tested by ELISA for the production of specific antibodies. Hybridomas producing high titers of antibodies against the purified fimbrial antigen were propagated and tested for reactivity against the CFs in a dot blot assay. A hybridoma colony expressing a strong anti-CF reaction was cloned by limiting dilution followed by expansion in modified Dulbecco’s medium supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum in culture flasks. Culture or ascitic fluids were harvested and kept in aliquots at −70°C. The MAb was isotyped by using a commercial kit (MAb isotyping kit, dipstick format; Life Technologies).

For polyclonal antibody production, two New Zealand White rabbits were immunized subcutaneously with 400 μg of purified fimbrial protein in complete Freund’s adjuvant and boosted with 200 μg in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant 21 days after the primary immunization. Sera were collected 10 days after the booster immunization.

Slide agglutination.

The slide agglutination assay was performed essentially as previously described (28). Briefly, bacterial cells were harvested from CFA agar and adjusted to a concentration of 1010 CFU/ml in PBS. Then 10 μl of bacterial suspension was applied to glass slides. To each drop, equal volumes of either diluted mouse polyclonal antisera or MAbs were added and mixed with a wooden applicator stick. Visible bacterial agglutination within 2 min was considered a positive reaction.

ELISA.

Briefly, wells of polystyrene microtiter plates were coated with 100 μl of purified fimbrial antigen (1 μg/ml in PBS) and kept at 37°C overnight. After blocking with 0.1% BSA in PBS, serial dilutions of antisera or MAbs in PBS containing 0.1% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20 were added and incubated for 90 min at room temperature. The plates were washed, and horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse IgG (H+L) antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.) were added followed by o-phenylenediamine. Within 15 to 20 min, the optical density of the developed color was read with an ELISA reader (Titertek Multiskan; Flow Laboratories, Irvine, Scotland) at 450 nm.

Dot blot immunoassay.

A 2-μl volume of bacterial suspension (109 CFU/ml) harvested from CFA agar was applied to each of the nitrocellulose strips presoaked in PBS and air dried. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubating the strips in 1% BSA–PBS, and this was followed by incubation for 2 h with mouse antisera (diluted 1:100) or culture supernatants containing MAbs (diluted 1:20). The strips were developed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse IgG (H+L) antisera in 0.1% BSA–0.05% Tween 20–PBS for 2 h at room temperature, after which 4-chloro-1-naphthol was added.

Electron microscopy (EM).

Negative staining and immunoelectron microscopy (IEM) techniques were described previously (6). Briefly, samples were negatively stained with 2% ammonium molybdate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and examined in a Hitachi HU-12A electron microscope at 80 kV. For IEM, prior to staining, each bacterium-coated grid was placed on a drop of primary antiserum diluted in Dulbecco’s PBS (Advanced Biotechnologies, Inc., Columbia, Md.) plus 1% BSA and washed with the same solution. Each grid was then placed on a drop of 15-nm goat anti-mouse colloidal gold or 10-nm goat anti-rabbit colloidal gold (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.).

Mass-spectrometric analysis.

Samples were prepared as previously described (5–7). Briefly, dried, salt-free proteins were dissolved in hexafluoroisopropanol (Sigma) and acetic acid was added to adjust the protein concentration to 5 to 10 mM. Electrospray mass spectra were acquired on an SX102 mass spectrometer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an electrospray source with a heated capillary (Analytica, Bradford, Conn.). The spectrum obtained (mass/charge) was deconvoluted with JEOL software, and the mass spectrum was determined. Lysozyme (molecular weight, 14,305.2) was used as an external standard in the first run of each day’s samples.

Protein sequencing.

Purified fimbria was run on precast 16% Tricine–SDS-PAGE gels as described above. Samples were electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (ProBlott; Perkin-Elmer–Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) by the method of Matsudaira (30) with the NOVEX miniblot apparatus. Electrotransferred proteins were stained with Rapid Coomassie stain (Diversified Biotech, Newton Centre, Mass.). The N-terminal sequence of the purified intact fimbria was obtained by placing strips of PVDF containing the intact subunit protein onto a precycled Polybrene membrane and subjecting the protein to gas-phase sequencing (model 494 sequencer; Perkin-Elmer–Applied Biosystems). To obtain the internal protein sequence near the N terminus of the protein, the covalent structure of the fimbria was disrupted with 70% formic acid (27). Digested material was run on SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes as above. The high-molecular-weight fragment selected in this manner was excised from the PVDF membrane and subjected to gas-phase sequencing.

RESULTS

Analysis of strain WS0115A for adhesion properties.

As a first step in the analysis of ETEC WS0115A for potential CFs, the MRHA pattern was determined by using human, bovine, chicken, and guinea pig erythrocytes. ETEC E1392-75 (CS1+) and E20738A (CS17+) were used as controls. When grown at 37°C, strain WS0115A induced MRHA of bovine erythrocytes. The MRHA-positive strain, E20738A (CS17+), displayed MRHA of both bovine and chicken erythrocytes, while the MRHA-negative strain, E1392-75 (CS1+), failed to display MRHA with any erythrocyte tested.

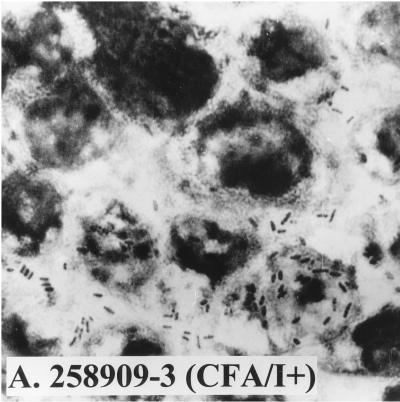

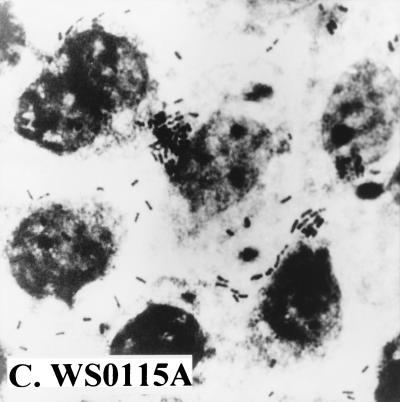

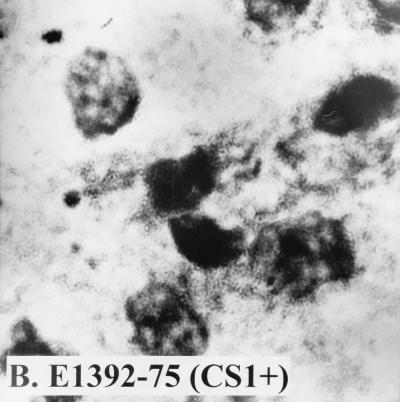

Since these results suggested that strain WS0115A expressed an unidentified adhesion, we examined its ability to attach to Caco-2 cells, an established cell culture model for ETEC colonization. In four separate experiments, it adhered to Caco-2 cells with a mean adherence of 23% (Fig. 1). The positive control, ETEC 258909-3 (CFA/I+), adhered to Caco-2 cells with a mean adherence of 21%, while the negative control, ETEC E1392-75 (CS1+), failed to adhere.

FIG. 1.

Adhesion ability of different ETEC strains to Caco-2 cells. (A) ETEC 258909-3 (CFA/I+, adhesion positive); (B) ETEC E1392-75 (CS1+, adhesion negative); (C) ETEC WS0115A (adhesion positive).

Purification of fimbrial antigen and characterization of antibodies.

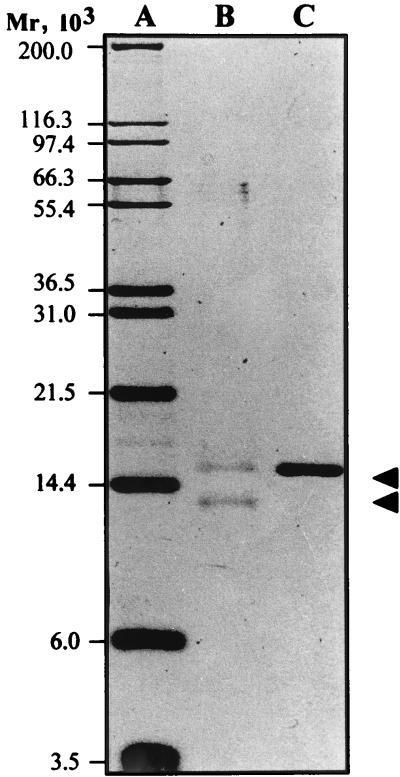

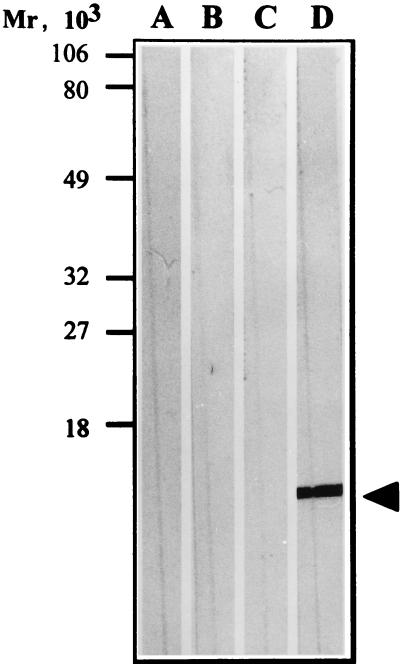

In light of the initial analysis of strain WS0115A for adhesion properties, a fimbrial protein extract was prepared. Resolution of a purified extract by SDS-PAGE revealed a single band with an apparent molecular weight (Mr) of 14,800 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE (16% polyacrylamide) analysis of the purified fimbrial preparation from ETEC WS0115A. Lanes: A, molecular weight standards; B, purified fimbrial preparation from ETEC WS0115A after 70% formic acid treatment; C, purified fimbrial preparation from ETEC WS0115A. The fimbrial protein band with Mr of 14,800 is indicated by the upper arrowhead, and the position of the cleavage product after formic acid treatment is indicated by the lower arrowhead.

To characterize this potential CF, the purified fimbrial extract from ETEC WS0115A was used for the production of polyclonal antibodies. Colony dot blot analysis of strain WS0115A and reference ETEC strains that expressed CFA/I, CS1, CS2, CS3, CFA/III, CS4, CS5, CS6, CS7, CS17, PCFO159, and PCFO166 with the resultant antiserum demonstrated strong reactivity against strain WS0115A as well as weaker reactions with strains that expressed CS1 or CS17 (data not shown). In contrast, strain WS0115A did not react with MAbs raised against these CFs, suggesting that it expressed a fimbrial protein that, while sharing some epitopes with CS1 and CS17, was distinct from them.

Antibodies from two hybridomas that were reactive in colony blots with strain WS0115A as well as with ETEC reference strains E1392-75 (CS1+) and E20738A (CS17+) were identified. One of these hybridomas, 3H12, with isotype and subclass profile IgG2b, was selected for further characterization. Limiting dilution of the 3H12 hybridoma produced a number of antibody-secreting colonies with properties identical to the 3H12 parent. These clones were used for expansion and production of MAbs.

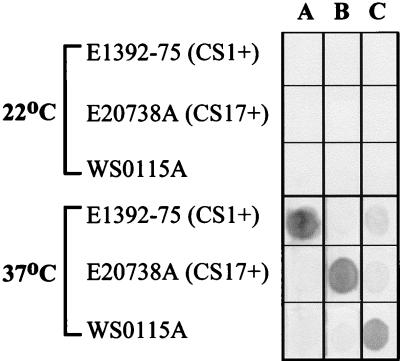

Western blot analysis with the 3H12 MAb against the purified fimbrial extract from strain WS0115A resolved by SDS-PAGE gave a strong reaction with a single antigenic band (Fig. 3). No reaction was observed when normal mouse sera or anti-CS1 or anti-CS17 MAbs were used. When the 3H12 MAb was used in a colony dot blot analysis, a strong reaction occurred with strain WS0115A (Fig. 4). Weaker reactions were observed when the 3H12 MAb was used in this assay with the ETEC reference strains E1392-75 (CS1+) and E20738A (CS17+). Reactivity for all strains was temperature dependent; fimbrial antigens could be detected when strains were grown at 37°C but not at 22°C.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of the purified fimbrial preparation from ETEC WS0115A. Lanes: A, normal mouse serum; B, anti-CS1 MAb; C, anti-CS17 MAb; D, MAb from the 3H12 hybridoma. The fimbrial protein band is indicated by the arrowhead.

FIG. 4.

Effect of temperature on CF expression. Colony dot blot analysis of E1392-75 (CS1 positive), ETEC E20738A (CS17 positive), and ETEC WS0115A grown at 22 and 37°C is shown. Lanes: A, reactivity with CS1-specific MAb; B, reactivity with CS17-specific MAb; C, reactivity with 3H12 MAb.

In a slide agglutination assay the mouse polyclonal antiserum used at a dilution of 1:60 agglutinated strain WS0115A and also the CS17-expressing ETEC E20738A, but not the CS1-expressing ETEC E1392-75. When this assay was repeated with the 3H12 MAb, no agglutination was seen with any of these strains. In contrast, the use of MAbs against CS1 and CS17 resulted in agglutination of the ETEC strains that expressed these respective CFs but not of strain WS0115A. As with the colony dot blot assay, agglutination displayed temperature dependence: agglutination was observed when bacteria were grown at 37°C on CFA agar containing bile salts but not when the bacteria were grown at 22°C.

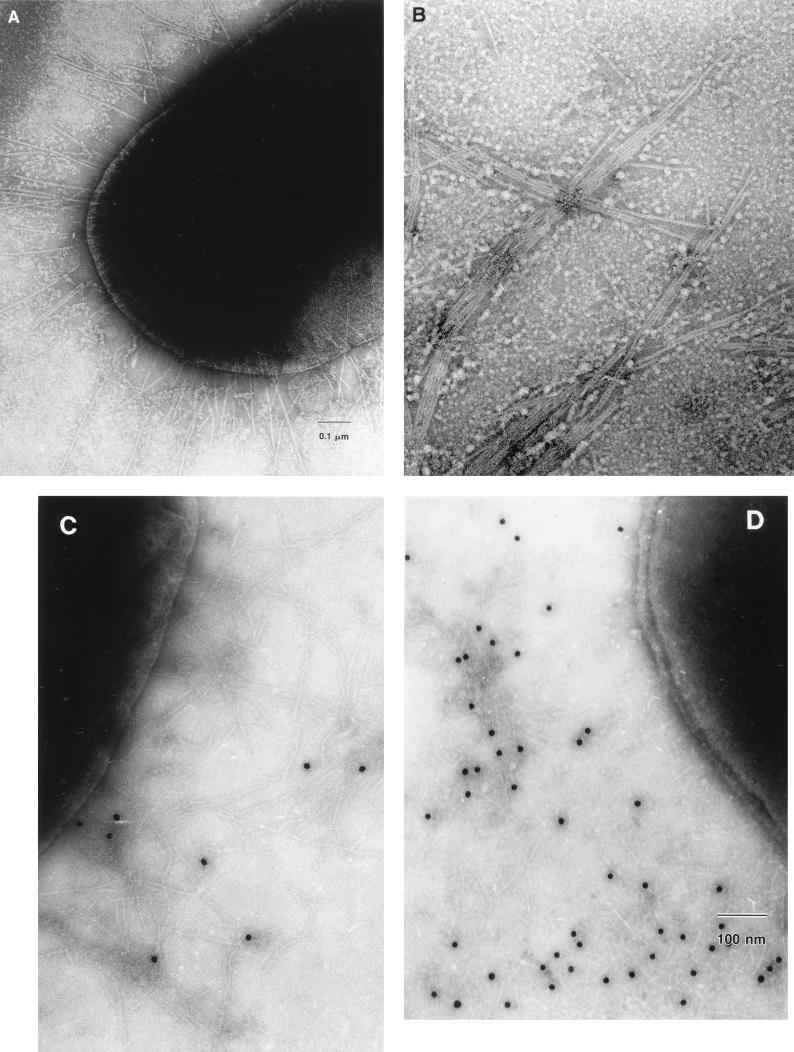

EM and IEM.

Strain WS0115A was examined for fimbrial structures by EM. The bacteria expressed fimbriae in a peritrichous manner, and the fimbriae were rigid and approximately 7 nm in diameter (Fig. 5A and B), with a range of 6.8 to 7.4 nm, similar to most ETEC CFs (8). IEM of strain WS0115A incubated with the 3H12 MAb demonstrated that binding occurred, albeit at low levels (Fig. 5C). Hyperimmune rabbit serum raised to purified fimbrial antigen was also used as the source of primary antibody in IEM (Fig. 5D). The serum showed a labeling of gold particles along the pilus shaft at several places with no apparent periodicity. Under identical conditions, control nonimmune rabbit serum demonstrated a lack of reactivity to the WS0115A bacterial cell in general and to the fimbriae in particular (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

EM and IEM of strain WS0115A and purified fimbriae. (A) Negative strain of WS0115A; (B) negative strain of purified WS0115A fimbriae; (C) IEM of strain WS0115A with the 3H12 MAb (primary dilution of 1:50 in Dulbecco’s PBS plus 1% BSA followed by goat anti-mouse 15 nm colloidal gold); (D) IEM of strain WS0115A with rabbit polyclonal antiserum raised against purified fimbriae of WS0115A (primary dilution of 1:500 in Dulbecco’s PBS plus 1% BSA followed by goat anti-rabbit 10-nm colloidal gold).

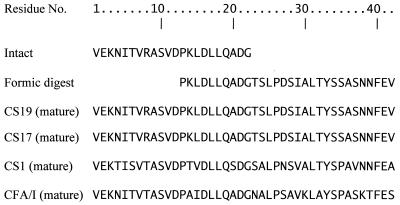

Molecular mass and protein sequence analysis.

Purified fimbriae from strain WS0115A analyzed by electrospray mass spectrometry showed several charged states of the denatured protein (most prominently m/z of 1,871.9, 2,138.9, and 2,494.9, with charges of 8, 7, and 6, respectively). When this data was deconvoluted, the mass of the purified fimbrial protein was determined to be 14,964.9.

Forty-two amino acids of the amino terminus of the putative CF from strain WS0115A were identified (Fig. 6). From the intact protein subunit, 22 amino acids were determined, while an additional 20 amino acids were determined from the lower-molecular-weight band derived from formic acid cleavage by selectively cleaving peptide bonds between aspartic acid and proline residues (27). This sequence information places this protein in the CFA/I family (8, 25).

FIG. 6.

N-terminal protein sequence of WS0115A fimbrial subunit. Residue no., the amino acid residue number, beginning at the amino terminus of the protein; Intact, untreated fimbrial protein; Formic digest: lower-molecular-weight protein derived from 70% formic acid cleavage. The sequences of the relevant regions of CS19, CS17, CS1, and CFA/I are shown for comparison.

Prevalence of putative CF in a type collection of ETEC strains.

A total of 231 ETEC strains, each obtained from individual episodes of pediatric diarrhea, were screened with the 3H12 MAb to determine the relative prevalence of the putative CF determinant. Of these ETEC strains, 49% (114 of 231) expressed a known CF as determined by a monoclonal dot blot assay (32). Of the ETEC strains that were CF negative, 4.2% (5 of 117) reacted with the 3H12 MAb. Serotype analysis of these five strains found that they were all O114:H−.

DISCUSSION

ETEC WS0115A (LTST:CF−/O114:H−) was initially identified as being negative for CFs based on monoclonal dot blot analysis. The putative CF detected in this study has properties similar to those of other ETEC adhesins, but it appears distinct from other known CFs. On the basis of our cumulative findings, we conclude that the fimbria of ETEC strain WS0115A represents a CF not previously detected in Africa.

Several independent lines of experimental evidence support our claim. First, this fimbria is immunologically distinct from other ETEC CFs since strain WS0115A did not express any of the major CFs as determined by colony dot blot analysis with anti-CF-specific MAbs. However, the 3H12 MAb reacted strongly with strain WS0115A in addition to ETEC reference strains expressing either CS1 or CS17. This cross-reaction with CS1 and CS17 indicates that these CFs share epitopes. Since previous studies have shown that CS1 and CS17, while being members of the CFA/I family, are more closely related to each other than to other members of this family (8, 17, 25), our findings suggest that the WS0115A fimbria is a CF closely related to CS1 and CS17 of the CFA/I family.

Our analysis of the WS0115A fimbria demonstrates that it shares many other properties of the major ETEC CFs, particularly those of the CFA/I family. First, it is expressed when grown in the presence of bile salts at 37°C but not at 22°C. It induces MRHA of bovine erythrocytes. Morphologically, the fimbria is a rigid rod, resembling those of the CFA/I family. Further, as shown by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE, mass spectrometry, and Western blot analysis, it appears to be a single subunit, as are most members of the CFA/I family.

While ETEC WS0115A was not examined for some other CFs such as CS13 (PCFO9), PCFO20, PCFO148, PCF2230, PCF8786, and Longus, its fimbrial antigen appears to be distinct from these antigens in one or more significant traits. The Mr of CS13 at 27,000, PCFO20 at 18,100, and Longus at 22,000 are poor matches for the CF of strain WS0115A (18, 20, 21, 45). PCFO20 does not mediate MRHA (43), in contrast to the strain WS0115A CF, which induces MRHA of bovine erythrocytes. PCFO148 is composed of curly fibrils of 3 nm in diameter, while the fimbriae on strain WS0115A are distinct rigid rods with a diameter of 7 nm (8, 17, 24). Unlike the CF of strain WS0115A, antigens PCF2230 and PCF8786 are described as nonfimbrial antigens (2, 11).

Could the CF of strain WS0115A be CS17? It differs from CS17 (31) in three respects. First, it is linked with ST production whereas CS17 is strictly associated with LT production even across different serogroups. Second, MAb against CS17 readily agglutinates CS17-positive ETEC strains but not strain WS0115A. The failure of the 3H12 MAb to agglutinate strain WS0115A could be due to the relatively small number of epitopes available for cross-linking. Another possibility is that this reflects the biological properties of the antibody subclass (IgG2b), since the polyclonal antiserum raised against the fimbria of strain WS0115A induces bacterial agglutination. Finally, the Mr of CS17 (17,300) is considerably larger than that of the fimbria expressed by strain WS0115A.

While we were completing this research, a new ETEC CF, designated CS19, was reported (19). These authors found a CF-negative ETEC strain, designated F595C, isolated from a patient with diarrhea in Bangladesh, that expressed a novel CF, which was designated CS19. Like our strain WS0115A, F595C is LTST, but F595C is O8:H25. CS19 is structurally and biochemically related to CS17 and to other members of the CFA/I family (19). The N-terminal sequence of the first 42 amino acids of the mature forms of CS17 and CS19 and the fimbria of strain WS0115A are identical, firmly establishing the protein family relationship (19, 25). In contrast to the CF expressed by strain WS0115A, CS19 reportedly does not mediate MRHA of bovine erythrocytes.

Despite these differences, there were enough similarities between the two adhesins to investigate their potential relationship. When we tested the reactivity and specificity of a CS19 polyclonal antiserum (φ79) against strain WS0115A, we found that it reacted strongly with strain WS0115A as well as with CS1- and CS17-expressing strains. In addition, the 3H12 MAb reacted strongly with strain F595C, a CS19-expressing ETEC. When we screened strain F595C and WS0115A for MRHA, we found that they had identical patterns, agglutinating only bovine erythrocytes.

Previous studies have demonstrated that electrospray mass spectrometry can be used to measure the mass of a protein to an accuracy of about 1 part in 10,000 (5, 7, 9). This level of accuracy can then be used as an independent means of verifying the accuracy of a given protein sequence as derived by classical protein sequencing techniques or by examining the deduced amino acid sequence from a DNA sequence. By using the sequence data for CS17 and CS19 (GenBank accession no. X97495 and X97494), the calculated masses of CS17 and CS19 are 15,375.1 and 14,962.8, respectively (14). The mass determined experimentally for the adhesin from strain WS0115A is 14,964.9. Thus, based on our cumulative findings, we conclude that the unidentified CF of ETEC strain WS0115A is CS19.

A key issue that must still be addressed for CS19 is its relevance in the pathogenesis of ETEC. While a full understanding of its role in the pathogenicity of ETEC will require both extensive field and laboratory studies, some preliminary conclusions can be drawn from our analysis of strain WS0115A in the Caco-2 adhesion assay. Previous studies have established that the Caco-2 cell adhesion assay is a useful in vitro test to investigate the interaction of bacterial enteropathogens with the human intestinal epithelium (12, 44). The cell line closely mimics the structural and functional characteristics of mature enterocytes in the small intestine. Like many other ETEC strains, the adhesion observed for strain WS0115A was mannose resistant, indicating that it was not mediated by type 1 pili. While the adhesion index was low relative to some other CFs and variable across the monolayer, these findings are typical for CF-positive ETEC strains. Previous studies have suggested that the disparity in distribution of cells with adherent bacteria is due to different degrees of differentiation in the individual Caco-2 cells, with corresponding variability in receptors (12, 44). Another possibility is that the variation in adhesion reflects the variation in the fimbriation of the bacterial strain (42). But overall, strain WS0115A behaved as would be expected for a CF-positive ETEC strain in this biological assay.

Further evidence for the biological relevance of CS19 comes from our retrospective analysis of CF-negative ETEC strains collected from children with diarrhea in Egypt, where CS19 was detected in 4.2% of these strains (33). This is a high frequency relative to that found for other putative CFs and suggests that CS19 may be common in this region. Similar retrospective analyses of these ETEC strains for other putative CFs found that antigens such as PCFO159 (0.5%), CFA/III (0.5%), PCFO9 (1.5%), and PCFO20 (1.4%) all were detected with substantially lower frequency in CF-negative ETEC strains than CS19 (33). However, although CS19-positive strains account for 2.2% of the total CF-positive strains and 4.2% of the previously CF-negative strains in our defined ETEC strain collection, this still leaves a significant fraction of our strains without a discernible CF phenotype. To address this, we are continuing to screen selected ETEC strains for novel adhesins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Reference strains, anti-CF MAbs, and the Caco-2 cell line were kindly provided by Anne-Mari Svennerholm, University of Göteborg, Göteborg, Sweden. ETEC F595C and the φ79 antiserum were kindly provided by Hans Sommerfelt, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway. The expert technical assistance of Jeff Anderson and John Barringer, WRAIR, is greatly appreciated. The editorial assistance of Sonia Atchoukian, NAMRU-3, and the photographic expertise of Rafi Pakhtchanian, NAMRU-3, is also greatly appreciated.

This research was supported by the U.S. Naval Medical Research and Development Command (Bethesda, Md.) work unit no. B690.00101PIX3270, U.S. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Md.) interagency agreement no. Y1-HD-0026-01, and the Global Programme on Vaccines and Immunization of the World Health Organization (Geneva, Switzerland).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu-Elyazeed R, Wierzba T F, Mourad A S, Peruski L F, Jr, Kay B A, Rao M, Churilla A M, Bourgeois A L, Mortagy A K, Kamal S M, Savarino S J, Campbell J R, Murphy J R, Naficy A, Clemens J D. Epidemiology of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) diarrhea in a pediatric cohort in a periurban area of Lower Egypt. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:382–389. doi: 10.1086/314593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubel D, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Joly B. New adhesive factor (antigen 8786) on a human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli O117:114 strain isolated in Africa. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1290–1299. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1290-1299.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binsztein N, Jouve M J, Viboud G L, Moral L L, Rivas M, Orskov L, Ahren C, Svennerholm A-M. Colonization factors of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from children with diarrhea in Argentina. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1893–1898. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.9.1893-1898.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black R E. Epidemiology of diarrhoeal disease: implications for control by vaccines. Vaccine. 1993;11:100–106. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90002-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassels, F. J., et al. Unpublished data.

- 6.Cassels F J, Deal C D, Reid R H, Jarboe D L, Nauss J L, Carter J M, Boedeker E C. Analysis of Escherichia coli colonization factor antigen 1 linear B-cell epitopes, as determined by primate responses, following protein sequence verification. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2174–2181. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2174-2181.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassels F J, Pannell L K, Boedeker E C. Abstracts of the 93rd General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1993. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. Absolute molecular weight determination of E. coli fimbrial major subunits, abstr. B-304; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassels F J, Wolf M W. Colonization factors of diarrheagenic E. coli and their intestinal receptors. J Ind Microbiol. 1995;15:214–226. doi: 10.1007/BF01569828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chait B T, Kent S B H. Weighing naked proteins: practical, high-accuracy mass measurements of peptides and proteins. Science. 1992;257:1885–1894. doi: 10.1126/science.1411504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cravioto A, Scotland S M, Rowe B. Hemagglutination activity and colonization factor antigens I and II in enterotoxigenic and non-enterotoxigenic strains of Escherichia coli isolated from humans. Infect Immun. 1982;36:189–197. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.1.189-197.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darfeuille-Michaud A, Forestier B, Joly B, Cluzel R. Identification of a nonfimbrial adhesive factor of an enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strain. Infect Immun. 1986;52:468–475. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.468-475.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darfeuille-Michaud A, Aubel D, Chauviere G, Rich C, Bourges M, Servin A, Joly B. Adhesion of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli to the human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2 in culture. Infect Immun. 1990;58:983–992. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.893-902.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De St. Groth S F, Scheidegger D J. Production of monoclonal antibodies. Strategies and tactics. J Immunol Methods. 1980;35:1–21. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(80)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans D G, Evans D J., Jr New surface associated heat-labile colonization factor antigen (CFA/II) produced by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli of serogroups O6 and O8. Infect Immun. 1978;21:638–647. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.2.638-647.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans D G, Evans D J, Jr, DuPont H L. Hemagglutination patterns of enterotoxigenic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli determined with human, bovine, chicken, and guinea-pig erythrocytes in the presence and absence of mannose. Infect Immun. 1979;21:336–346. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.2.336-346.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaastra W, Svennerholm A-M. Colonization factors of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:444–452. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giron J A, Levine M M, Kaper J B. Longus: a long pilus ultrastructure produced by human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:71–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grewal H M S, Valvatne H, Bhan M K, van Dijk L, Gaastra W, Sommerfelt H. A new putative fimbrial colonization factor, CS19, of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1997;65:507–513. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.507-513.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heuzenroeder M W, Elliot T R, Thomas C J, Halter R, Manning P A. A new fimbrial type (PCFO9) of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli O9:H−, LT+ isolated from a case of infant diarrhea in Central Australia. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;66:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90258-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hibberd M L, McConnell M M, Field A M, Rowe B. The fimbriae of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strain 334 are related to CS5 fimbriae. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:2449–2456. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-12-2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honda T, Arita M, Miwatani T. Characterization of new hydrophobic pili of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: a possible new colonization factor. Infect Immun. 1984;43:959–965. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.959-965.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalil S B, Shaheen H, El Ghorab N, Mansour M M, Peruski L F, Jr, Churilla A, Kamal K. Abstracts of the 96th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1996. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. Detection of a putative colonization factor of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli from Egyptian children with diarrhea, abstr. B-254; p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knutton S, Lloyed D R, McNeish A S. Identification of a new fimbrial structure in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) serotype O148 which adheres to human intestinal mucosa: a potentially new human ETEC colonization factor. Infect Immun. 1987;55:86–92. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.86-92.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kusters J G, Gaastra W. Fimbrial operons and evolution. In: Klemm P, editor. Fimbriae: adhesion, genetics, biogenesis, and vaccines. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press Inc.; 1994. pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landon M. Cleavage at aspartyl-prolyl bonds. Methods Enzymol. 1977;47:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(77)47017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez-Vidal Y, Svennerholm A-M. Monoclonal antibodies against the different subcomponents of colonization factor antigen II of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1906–1912. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1906-1912.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsudaira P. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidine difluoride membranes. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McConnell M M, Hibberd M, Field A M, Chart H, Rowe B. Characterization of a new putative colonization factor (CS17) from a human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli of serotype O114-H21 which produces only heat-labile enterotoxin. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:343–347. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McConnell M M, Hibberd M L, Penny M E, Scotland S M, Cheasty T, Rowe B. Surveys of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli from three different geographical areas for possible colonizations. Epidemiol Infect. 1991;106:477–484. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800067522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peruski, L. F., et al. Unpublished data.

- 34.Peruski, L. F., B. A. Kay, R. Abu El-Yazeed, S. H. El-Etr, A. Cravioto, T. F. Wierzba, M. Rao, N. El-Ghorab, H. Shaheen, S. B. Khalil, K. Kamal, A.-M. Svennerholm, J. D. Clemens, and S. J. Savarino. Phenotypic diversity of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) from a community-based study of pediatric diarrhea in rural Egypt. J. Clin. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smyth C J. Two mannose-resistant hemagglutinins on enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli of serotype O6.K15.H16 or H− isolated from travellers and infantile diarrhoea. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:2081–2096. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-9-2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sommerfelt H, Steinsland H, Grewal H, Viboud G I, Bhandari N, Gaastra W, Svennerholm A-M, Bhan M. Colonization factors of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from children in North India. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:768–776. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J, Sack D A. Development of oral vaccines against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhoea. Vaccine. 1989;7:196–198. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(89)90228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Svennerholm A-M, Wiklund G. Rapid GM1-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a visual reading for identification of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:596–600. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.4.596-600.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svennerholm A-M, Wikstrom M, Lindbland M, Holmgren J. Monoclonal antibodies against Escherichia coli heat stable-toxin (STa) and their use in a diagnostic ST gangloside GM1-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:585–590. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.4.585-590.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets. Procedures and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valvatne H, Sommerfelt H, Gaastra W, Bhan M K, Grewal H M S. Identification and characterization of CS20, a new putative colonization factor of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2635–2642. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2635-2642.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viboud G I, Binsztein N, Svennerholm A-M. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies against putative colonization factors of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and their use in an epidemiological study. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:558–564. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.3.558-564.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viboud G I, McConnell M M, Helander A, Svennerholm A-M. Binding of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli expressing different colonization factors to tissue-cultured Caco-2 cells and to isolated human enterocytes. Microb Pathog. 1996;21:139–147. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viboud G I, McConnell M M, Smith H R, Rowe B. A new fimbrial colonization factor, PCFO20, in human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1990;61:5190–5197. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5190-5197.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolf M K. Occurrence, distribution, and associations of O and H serogroups, colonization factor antigens, and toxins of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:569–584. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]