Abstract

Background & Aims:

The economic burden of chronic liver disease is rising, however the financial impact of chronic liver disease on patients and families has been underexplored. We performed a scoping review to identify studies examining financial burden (patient/family healthcare expenditures), financial distress (material, behavioral, and psychological consequences of financial burden), and financial toxicity (adverse health outcomes of financial distress) experienced by patients with chronic liver disease and their families.

Methods:

We searched Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, and the Web of Science online databases for articles published since the introduction of the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score for liver transplant allocation in February 2002 until July 2021. Final searches were conducted between June and July 2021. Studies were included if they examined the prevalence or impact of financial burden or distress among patients with chronic liver disease and/or their caregivers.

Results:

A total of 19 observational studies met inclusion criteria involving 24,549 patients and 276 caregivers across 5 countries. High rates of financial burden and distress were reported within the study populations, particularly among patients with hepatic encephalopathy, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver transplant recipients. Financial burden and distress were associated with increased pre- and post-transplant healthcare utilization and poor health-related quality of life as well as caregiver burden, depression, and anxiety. None of the included studies evaluated interventions to alleviate financial burden and distress.

Conclusions:

Observational evidence supports the finding that financial burden and distress are underrecognized but highly prevalent among patients with chronic liver disease and their caregivers and are associated with poor health outcomes. There is a critical need for interventions to mitigate financial burden and distress and reduce financial toxicity in chronic liver disease care.

Keywords: Financial distress, financial toxicity, financial hardship, end-stage liver disease, cirrhosis, palliative hepatology

INTRODUCTION:

The global burden of chronic liver disease is rising, affecting over 1.5 billion individuals worldwide.1 In Europe, liver disease is now the second leading cause of years of working life lost, following ischemic heart disease.2 In the United States, there have been rising rates of cirrhosis-related hospitalizations and consequent annual healthcare costs over the past two decades, outpacing those for patients with congestive heart failure.3,4

Despite the growing recognition of the increasing economic burden of chronic liver disease globally, we lack a comprehensive understanding of its financial impact on patients and their families. While there has been an increasing recognition of the financial impact of cancer5 and cardiovascular disease6 on patients and their families, we currently lack an understanding of the costs experienced by patients with chronic liver disease and their families across the following domains:

Financial burden: Patient and family income consumed by healthcare costs7–9

Financial distress: Material, behavioral, and psychological consequences of financial burden7–11

Financial toxicity: Adverse health outcomes of financial distress5,8,12

To address this gap, we performed a scoping review of the financial impact of chronic liver disease on patients and families to broadly explore key concepts and available evidence on this topic.13 Our specific scoping review objectives were to (1) identify the types of financial burden and distress experienced by patients with chronic liver disease and their family caregivers; (2) identify risk factors for financial burden and distress; and (3) describe financial toxicity outcomes in this population. We conclude by proposing a conceptual framework characterizing domains of financial burden, distress and toxicity in chronic liver disease care to guide future research, intervention development, and clinical-, policy-, and system-level changes needed to address current gaps in care.

METHODS:

Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

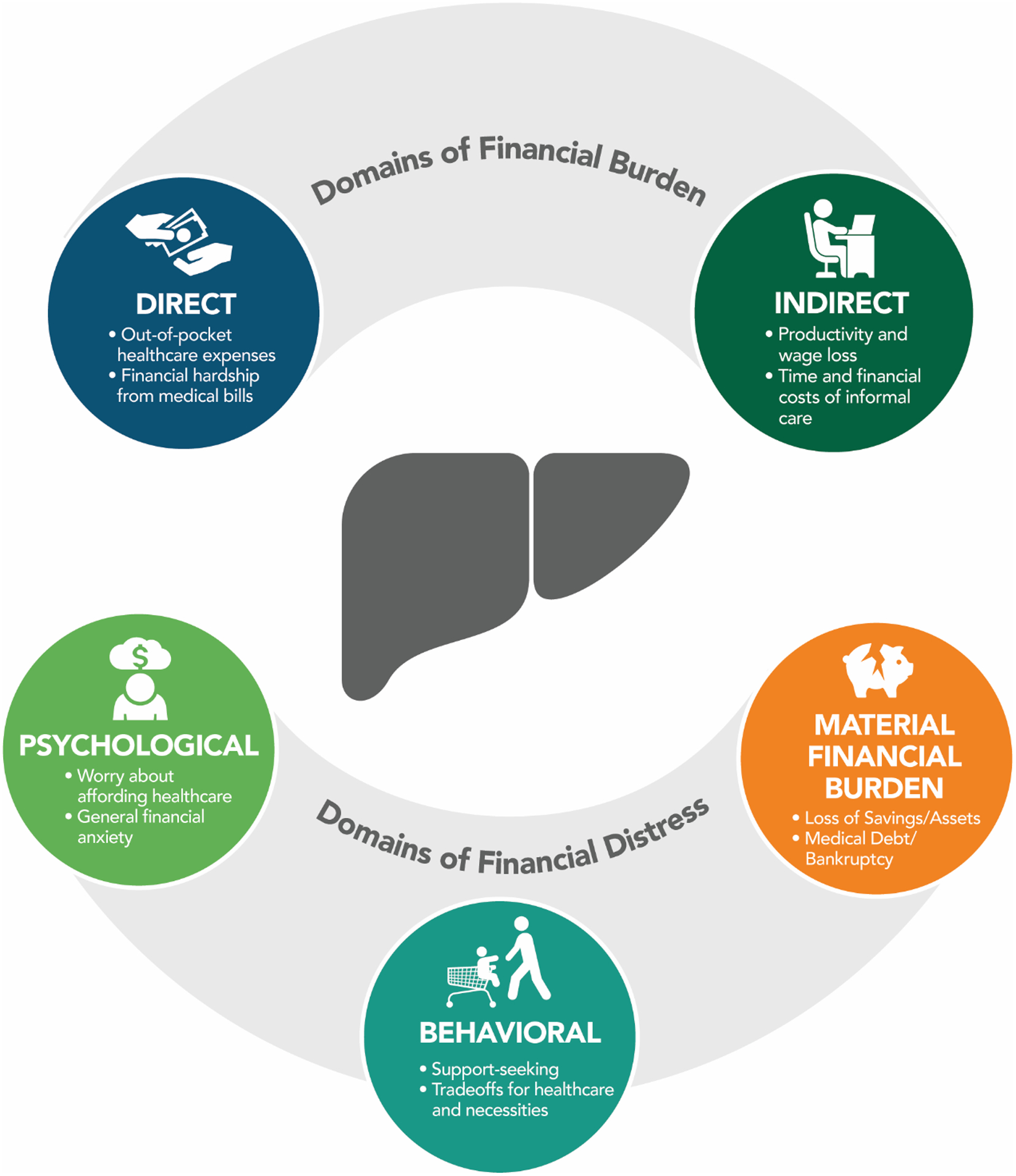

To be included in the review, studies needed to examine the prevalence or impact of financial burden and/or distress among patients with chronic liver disease and/or their caregivers. Definitions of financial burden and financial distress were informed by review of the oncology and cardiology literature.6–8,10,14 Financial burden measures included both direct (healthcare expenditures) and indirect (wage loss) financial burden. Measures of direct financial burden included objective measures such as out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures and subjective measures such as patient- and caregiver-reported difficulty paying medical bills. Measures of indirect financial burden included work loss, absenteeism, and costs of caregiving due to chronic liver disease care. Financial distress measures were classified in three broad domains: (1) material consequences of the costs of chronic liver disease care such as loss of savings, medical debt, and bankruptcy; (2) behavioral coping strategies to manage financial burden including support-seeking and making tradeoffs between medical care and paying for necessities including healthcare; and (3) psychological worry or distress due to financial burden (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Domains of Financial Burden and Distress in Chronic Liver Disease Care.

Studies were included if they were: (1) peer-reviewed original research; (2) written in English; (3) available in full-text; and (4) involved adult (≥ 18 years old) individuals with chronic liver disease or their caregivers. We included quantitative and mixed-methods studies to examine different methods of assessing financial hardship in this population. Studies were excluded if they did not report patient- or caregiver-level quantitative data on financial burden or distress.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

With the support of one research librarian (LP), we searched the following online databases to identify potentially relevant manuscripts: Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. We limited our search to articles published since the introduction of the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score for liver transplant allocation in February 2002 until July 2021. In addition, we manually examined the citation list of any relevant studies and reviews to identify additional eligible studies. Final searches were conducted between June and July 2021. References were sorted and evaluated for inclusion using the Rayyan application.15 The search terms and strategy for each database are available in Appendix A.

Study Selection and Data Abstraction

After removal of duplicate citations, two independent reviewers (N.N.U. and N.S.) performed title and abstract screening followed by full-text review to identify potentially eligible studies. Interrater discrepancies for study inclusion were resolved by one additional reviewer (M.S.).

We developed a structured extraction form for study characteristics, including study objective, study design, setting and data source, eligibility criteria, participant demographics and clinical characteristics, definition or measurement of financial burden and distress, outcome measurements, and key findings. We additionally extracted reported risk factors for financial burden and distress and the association of financial burden and distress variables with patient and caregiver health outcomes (financial toxicity). The extraction form was piloted on a sample of articles and data extraction was completed independently by two reviewers (N.N.U. and N.S.) and reviewed by an additional reviewer (M.S.). All healthcare expenditure data were inflation-adjusted to the year 2021 using the United States Inflation Calculator and Bank of Canada Inflation Calculator and are reported as mean annual expenditures where appropriate.16,17

Conceptual Framework

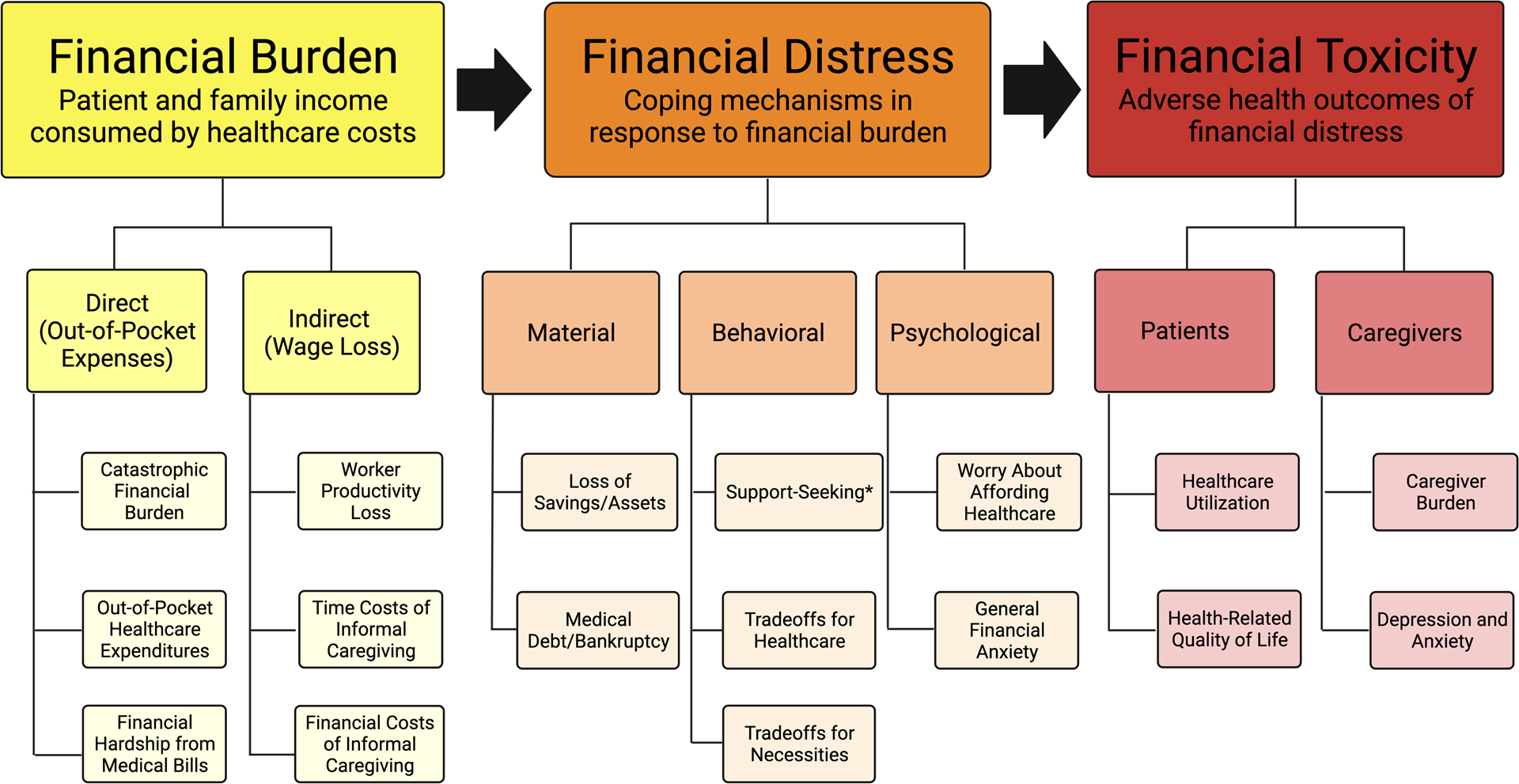

We integrated the findings from our scoping review with existing models of financial burden in the oncology and cardiology literature to develop a conceptual framework for financial burden, distress, and toxicity in chronic liver disease based on currently-available evidence (Figure 2).6–11,14

Figure 2:

Conceptual Framework of Financial Burden, Financial Distress, and Financial Toxicity in Chronic Liver Disease Care. *Support-seeking includes financial coping behaviors such as crowdfunding, increased borrowing, pursuit of cost-reducing strategies for medical care, and caregivers increasing their work capacity.

RESULTS

Study Selection

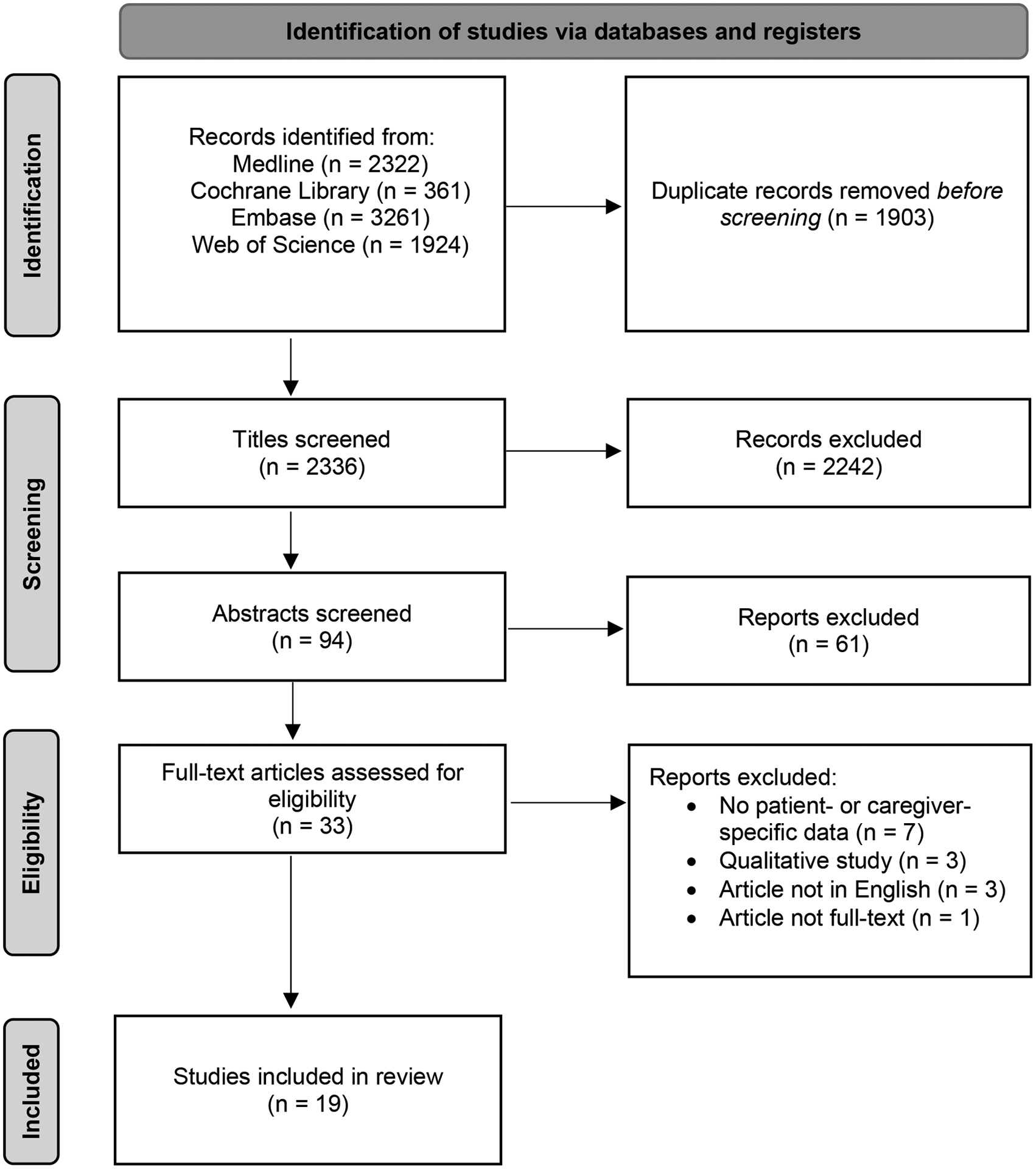

Of 2,336 nonduplicate records screened, with 94 titles, abstracts, and/or full texts reviewed, 19 studies met the final inclusion criteria. The PRISMA flow chart is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3:

Flow Diagram of Study Selection

Study and Patient Characteristics

Included studies were conducted between 2007–2021 and patient sample sizes ranged between 96 and 12,998 for a combined sample of 24,549 patients across all the studies. A total of 18 studies used structured surveys and one study used mixed-methods. Most of the studies were from the United States (n=11) followed by Canada (n=3), India (n=3), China (n=1), and Bangladesh (n=1). A few studies focused on patients with a specific etiology of chronic liver disease such as Hepatitis B (HBV) (n=1), Hepatitis C (HCV) (n=2), and alcohol-related liver disease (n=1). Five studies focused on liver transplant recipients (n=5). Three studies included data on caregivers for a total caregiver sample size of 276. Additional study information and patient and caregiver characteristics, including demographic information, are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Reference | Study Description | Study Design Setting/Data Source (Subjects, n) | Study Inclusion Criteria Participant Demographics | Financial Burden and Financial Distress Measures: Definition, Prevalence | Financial Toxicity Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lago-Hernandez et al., 2021 (USA)32 | To estimate the prevalence, risk factors, and consequences of cost-related medication non-adherence in individuals with chronic liver disease | Cross-sectional NHIS, 2014–2018 (n=3,237) |

Patients with chronic liver disease

|

Behavioral Financial Distress (Tradeoffs for Healthcare): Cost-related medication nonadherence

|

Among chronic liver disease patients, cost-related medication nonadherence was associated with:

|

| Lago-Hernandez et al., 2021 (USA)25 | To estimate the national burden and consequences of financial hardship from medical bills in individuals with chronic liver disease | Cross-sectional NHIS, 2014–2018 (n=3,666) |

Patients with chronic liver disease

|

Direct Financial Burden (Financial Hardship from Medical Bills):

|

Among chronic liver disease patients, being unable to pay medical bills was associated with:

|

| Peretz et al., 2020 (Canada)23 | To document the psychological and financial impact of having to travel long distances for liver transplantation in adult liver disease patients | Cross-sectional Health Sciences Center, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada; 2018–2019 (n=96) |

Liver transplant recipients

|

Direct Financial Burden (Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditures) for patients and/or their families/friends during the liver transplant hospitalization:

|

N/A |

| Pol et al., 2019 (Canada)34 | To increase understanding of the motivations and outcomes of organ transplantation crowdfunding | Mixed-methods Canadian adult liver transplantation campaigns posted to GoFundMe; May 2018 (n=134) |

Adult liver transplant candidates |

Behavioral Financial Distress (Support-Seeking): Crowdfunding

|

N/A |

| Lu et al., 2019 (USA)63 | To examine hepatitis C virus (HCV) medication use and costs in a commercially insured population | Retrospective Harvard Pilgrim Health Care medical and pharmacy claims data, 2012–2015 (n=3,091) |

Patients with chronic HCV infection

|

Direct Financial Burden (Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditures) on HCV medications

|

N/A |

| Beal et al., 2017 (USA)30 | To examine patterns of employment discontinuity among liver transplant recipients and evaluate clinical, demographic, and economic factors that may contribute to delayed or unstable employment | Retrospective UNOS, 2002–2009 (n=12,998) |

Deceased donor liver transplant recipients at least 5 years post-transplant

|

Indirect Financial Burden (Worker Productivity Loss): Patient employment status after liver transplantation

|

N/A |

| Singh et al., 2016 (India)26 | To estimate the socioeconomic impact of alcohol use on patients with alcohol-related liver disease and their families | Cross-sectional Shrirama Chandra Bhanj Medical College and Hospital, Cuttack, Odisha, India, 2013–2014 (n=100) |

Patients with alcohol-related liver disease

|

Indirect Financial Burden (Worker Productivity Loss):

|

N/A |

| Stepanova et al., 2017 (USA)4 | To assess the effects of chronic liver disease on quality of life and work productivity as well as its economic burden in the US | Cross-sectional MEPS, 2004–2013 and NHANES (1999–2012) (n=1,864) |

Patients with chronic liver disease

|

Direct Financial Burden (Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditures):

|

Yearly health expenses (per $10,000 USD) were independently associated with a decrease in the Physical Component Score (Beta = −0.5 ± 0.09) and Mental Component Score (−0.25 ± 0.10) of the Short-Form 12 health-related quality of life survey |

| Che et al., 2016 (China)19 | To investigate the financial burden of patients who had various stages of hepatitis B (HBV)-related diseases and the level of alleviation from financial burden by health insurance schemes in Yunnan province of China | Cross-sectional First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, 2012–2013 (n=940) |

Patients with chronic HBV, compensated HBV cirrhosis, decompensated HBV cirrhosis, and HBV with HCC

|

Direct Financial Burden (Catastrophic Financial Burden): Household’s out-of-pocket expenses exceeding 40% of household’s capacity to pay

|

N/A |

| Rakoski et al., 2012 (USA)21 | To assess health status and functional disability of older individuals with cirrhosis and its complications, as well as estimate the burden and cost of informal caregiving in this population | Prospective longitudinal Health and Retirement survey linked to Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 1998–2008 (n=371) |

Patients > 50y with cirrhosis

|

Direct Financial Burden (Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditures): Self-reported over the previous two years

|

N/A |

| Hareendran et al., 2020 (India)31 | To study the quality of life, psychosocial burden and prevalence of mental health disorders among caregivers | Cross-sectional Government Medical College Trivandrum, South India, 2018–2019 (n=132) |

Primary caregivers of patients with cirrhosis

|

Behavioral Financial Distress (Support-Seeking):

|

Increased cost of cirrhosis treatment was associated with an increased risk of depression and anxiety among caregivers |

| Rodrigue et al., 2007 (USA)24 | To survey liver transplant and kidney transplant recipients about the financial impact of transplantation and to ascertain the strategies they used to manage non-reimbursed expenses related to transplantation | Cross-sectional University of Florida, 1995–2004 (n=333) |

Liver transplant recipients

|

Direct Financial Burden (Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditures): Estimated monthly out-of-pocket expenses

|

N/A |

| Shrestha et al., 2019 (India)27 | To evaluate the burden on the informal caregivers of patients with cirrhosis and the factors responsible for this burden in a population in Northern India | Cross-sectional Post-graduate institute of Medical Education and Research, Northern India, 2015 (n=200; 100 patients and 100 caregivers) |

Patients with cirrhosis and their informal caregivers

|

Indirect Financial Burden (Worker Productivity Loss):

|

N/A |

| Rahman et al., 2020 (Bangladesh)18 | To estimate the cost of illnesses among a population in urban Bangladesh and to assess the household financial burden associated with these diseases | Cross-sectional Rajshahi, Bangladesh, 2011 (n=41) |

Household members with self-reported liver disease |

Direct Financial Burden (Catastrophic Financial Burden): Household’s out-of-pocket expenses exceeding 40% of household’s capacity to pay

|

N/A |

| Federico et al., 2012 (Canada)22 | To evaluate time costs (time spent seeking healthcare) and out-of-pocket costs for patients with hepatitis C (HCV) and their caregivers | Cross-sectional University of British Columbia, 2006–2008 (n=738) |

Patients with HCV

|

Direct Financial Burden (Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditures):

|

N/A |

| Bajaj et al., 2013 (USA)29 | To investigate the association between socioeconomic status and cognition in a multicenter study of cirrhosis | Cross-sectional Multicenter (Virginia Commonwealth University, University of Rome, Case Western University), 2012 (n=236) |

Patients with cirrhosis

|

Indirect Financial Burden (Worker Productivity Loss):

|

N/A |

| Bajaj et al., 2011 (USA)28 | To study the emotional and socioeconomic burden of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy on patients and informal caregivers | Cross-sectional Virginia Commonwealth University, 2009–2010 (n=104) |

Patients with cirrhosis and their informal caregivers

|

Material Financial Distress (Loss of Savings/Assets, Medical Debt/Bankruptcy):

|

N/A |

| Bolden and Wicks, 2010 (USA)35 | To examine predictors of subjective burden and mental health status of family caregivers of persons with chronic liver disease | Cross-sectional University-based hepatology practice in a large southeastern US city, 2010 (n=73) |

Family caregivers of patients with chronic liver disease

|

Indirect Financial Burden (Worker Productivity Loss):

|

Caregivers who experienced a decrease in their income were more likely to report depressive and anxiety symptoms and caregiver burden |

| Serper et al., 2017 (USA)33 | To evaluate the association of “medication trade-offs”—defined as choosing to spend money on other expenses over medications—with medication nonadherence and transplant outcomes | Cross-sectional Two large US transplant centers, 2011–2012 (n=103) |

Liver transplant recipients > 30 days post-transplant

|

Indirect Financial Burden (Worker Productivity Loss):

|

Patients with trade-offs were more likely to report nonadherence to medications (mean adherence: 77 ± 23% with trade-offs vs. 89 ± 19% without trade-offs, p < 0.01). The presence of medication trade-offs was associated with post-transplant hospital admissions (RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.14–2.35, p < 0.01) |

Types of Financial Burden and Distress in Liver Disease

Direct Financial Burden

Catastrophic Financial Burden and Out-of-Pocket Healthcare Expenditures

A total of seven studies examined direct financial burden in pre- and post-transplant patients with chronic liver disease.18–24 The prevalence of catastrophic financial burden, defined as annual out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures exceeding 40% of annual household income, ranged between 12%−51% among patients with HBV and other chronic liver diseases in two cross-sectional studies from Bangladesh and China.18–20 In a 2017 U.S. study by Stepanova et al. conducted using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), patients with chronic liver disease reported out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures of $19,390 U.S. dollars (USD) annually ($22,808 in inflation-adjusted USD) compared to $5,567 annually ($6,548 in inflation-adjusted USD) in patients without liver disease.4 In a 2021 study by Rakoski et al. using a nationally representative sample of older adults in the U.S., patients with cirrhosis reported paying $1,075 USD ($1,306 in inflation-adjusted USD) in annual out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures compared to $730 USD ($886 in inflation-adjusted USD) for those without cirrhosis.21 High out-of-pocket health expenditures were also observed in a 2012 Canadian study by Federico et al. of 738 patients with chronic HCV, in which patients receiving active treatment and those with late-stage disease spent approximately 7% of their annual income on HCV-related healthcare.22

Two single-center studies examined financial burden in the post-transplant setting.23,24 In a 2020 cross-sectional survey study of 96 liver transplant recipients by Peretz et al., patients and families spent a median of $4,645 Canadian dollars (CAD) ($4,904 in inflation-adjusted CAD) out-of-pocket during their liver transplant hospitalizations.23 In a 2017 U.S. study of 333 patients by Rodrigue et al., liver transplant recipients reported spending an average of $6,480 USD ($7,368 in inflation-adjusted USD) annually in out-of-pocket for transplant-related medical costs.24 In this study, 43% of participants reported that health problems related to their transplantation had caused financial problems for themselves or their families.

Financial Hardship from Medical Bills

In a 2021 U.S. study by Lago-Hernandez et al. using the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS, 2014–2018), 37% of patients with chronic liver disease reported financial hardship from medical bills, and 14% were unable to pay their medical bills at all.25 After adjusting for comorbidities, insurance status, and sociodemographic factors, patients with chronic liver disease were significantly more likely to experience hardship from medical bills than adults without chronic liver disease (adjusted OR [aOR] 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.27–1.62). In this study, the prevalence of financial hardship from medical bills among patients with chronic liver disease was comparable to diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease.

Indirect Financial Burden

Worker Productivity Loss

Rates of unemployment among patients with chronic liver disease ranged from 44%−80% across six observational studies.4,22,26–29 The 2017 study by Stepanova et al. revealed that the rate of employment among patients with chronic liver disease was substantially lower compared to non-chronic liver disease patients (45% vs. 70%, p<0.0001).4 In addition, patients with chronic liver disease had significantly lower work productivity due to illness and disability, reporting 3 times more disability days per year compared to controls (10.2 days vs. 3.4 days, p<0.0001).

Two studies reported unemployment rates among liver transplant recipients ranging from 36%−48%.22,30 In the 2011 study by Federico et al. of 47 HCV transplant recipients, mean annual time costs (time spent seeking healthcare) resulted in the equivalent of 420 hours (over 10 weeks of working time) of lost wages per patient per year.22 A 2017 study by Beal et al. of 12,998 liver transplant recipients using United Network for Organ Sharing data (2002–2009) revealed that more than 1 in 10 patients had delayed work participation until 3 years or more after their transplant.30

Time and Financial Costs of Informal Caregiving

Two studies reported out-of-pocket and time costs of informal caregiving for patients with chronic liver disease.21,22 In a U.S.-based analysis of the Health and Retirement Study (1998–2008) by Rakoski et al., the annual costs of informal caregiving for older individuals with cirrhosis was $4,700 USD ($5,707 in inflation-adjusted USD) per person, compared to $2,100 USD ($2,550 in inflation-adjusted USD) for age-matched individuals without cirrhosis.21 In the 2011 Canadian study by Federico et al., time costs of informal caregiving resulted in the equivalent of annual lost wages of $766 CAD, $1,050 CAD, and $2,460 CAD for caregivers of patients with HCV cirrhosis, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver transplant recipients, respectively.22

Financial Distress

Material Financial Distress

Loss of Savings/Assets

In a 2011 U.S. cross-sectional study by Bajaj et al. of 104 patients with cirrhosis and their caregivers, 54% of families reported that they were unable to add to their personal/family savings and 5% were evicted from their homes due to their medical expenses.28 In a 2013 multicenter study by Bajaj et al. of 236 patients with cirrhosis, median liquid assets ranged from $500 - $4,999 USD ($598 - $5,983 in inflation-adjusted USD) in the patient cohort, which reduced to under $500 USD if current debt was subtracted.29 In a 2007 study by Rodrigue et al. of 333 adult liver transplant recipients, 57% of patients reported that they needed to use their savings to pay for out-of-pocket medical expenses.

Medical Debt/Bankruptcy

Two studies reported a prevalence of medical debt ranging from 24%−46% and medical bankruptcy ranging from 7%−8% of the study populations.24,28

Behavioral Financial Distress

Support-Seeking

Five studies reported financial coping behaviors that included support-seeking behaviors such as crowdfunding28, increased borrowing26,31, pursuing cost-reducing strategies for prescription medications32, and family members having to return to work and/or increase their work hours31 to manage treatment expenses. In one cross-sectional study from India of 132 caregivers of patients with cirrhosis, 25% reported that they had to return to work due to increasing family financial constraints.31 In the 2011 study by Bajaj et al. of 104 caregivers of patients with cirrhosis, 79% of caregivers reported that they did not have any support for financial advice.28

Tradeoffs for Healthcare

Multiple studies reported maladaptive coping behaviors in patients with chronic liver disease and their families in response to financial burden from medical care. Three studies examined the impact of financial burden on patient engagement with medical care.28,32,33 In the 2021 study by Lago-Hernandez et al. of a nationally representative sample of 3,237 patients with chronic liver disease in the U.S., 25% reported experiencing cost-related medication non-adherence.32 In this analysis, patients with chronic liver disease were significantly more likely to experience cost-related medication non-adherence compared to adults without chronic liver disease (aOR 1.4; 95% CI 1.22–1.61). A 2011 U.S. study of 104 patients by Bajaj et al. revealed that cirrhosis-related medical expenses resulted in 12% of patients missing medical appointments, 12% not taking medications, 10% taking less medications than prescribed, and 5% missing needed medical procedures.28 In a 2017 study by Serper et al. of 103 liver transplant recipients from two large U.S. transplant centers, 10% indicated that they could not afford their medications over the past 12 months, and 11% reported that they had to space out their medication frequency due to cost.33

Tradeoffs for Necessities

Five studies examined the impact of financial burden of chronic liver disease care on patients’ abilities to afford necessities such as food and housing.25,28,32–34 In the study by Lago-Hernandez et al., patients with chronic liver disease experiencing financial burden from medical bills had significantly higher odds of food insecurity (aOR 5.6, 95% CI 3.74–8.37)25. In three studies, patients and/or caregivers reported that they had to reduce spending on their children’s education in order to afford medical care.26,28,31

Psychological Financial Distress

Three studies reported the prevalence of psychological financial distress among patients with chronic liver disease ranging from 36% to 63%.24,25,28 In the 2014–2018 analysis of the NHIS by Lago-Hernandez et al., 36% of U.S. patients with chronic liver disease reported high financial distress regarding their future ability to pay for medical care, housing, and monthly bills, save for retirement, and maintain their standard of living.25

Risks Factors for Financial Burden and Financial Distress

Thirteen out of 19 (68%) manuscripts assessed risk factors associated with experiencing financial burden and financial distress.

Common socioeconomic risk factors were lack of insurance25,33, use of public insurance30,33, lower income19,22,25,32,33, unemployment24,25,30,33, lower educational attainment25,29,30,33, and lower health literacy33. Among liver transplant recipients, individuals who were unemployed in the year preceding their transplant were at increased risk of post-transplant unemployment and financial distress.30

Multiple demographic factors were associated with financial hardship and distress. Gender disparity was a common theme, with women at a greater risk of financial burden and distress25,30,32. Black patients were found to have higher rates of financial hardship from medical bills25 and were more likely to report medication trade-offs.33 Patients who were unmarried were less likely to be employed4 as were older adults4,23,28. Younger age was associated with increased financial hardship from medical bills and cost-related medication non-adherence25,32.

Clinical risk factors for financial hardship and distress were examined in multiple studies. Rates of catastrophic financial burden increased with worsening severity of disease (36% compensated cirrhosis, 51% decompensated cirrhosis) in one study of 940 patients with HBV-related disease in China.19 Other clinical factors associated with an increased risk of financial hardship and/or unemployment included the presence of HCC3,4, hepatic encephalopathy9,14, and multimorbidity25,32,33. In one observational study of liver transplant recipients, an increased risk of post-transplant unemployment was seen among patients who developed acute rejection (2.17 relative risk ratio [RRR], 95% CI 1.86–2.54) and diabetes mellitus (1.92 RRR, 95% CI 1.67–2.21) after transplantation.30

Financial Toxicity in Liver Disease

Five studies (26%) assessed the association between financial burden, financial distress, and healthcare outcomes. In the 2021 study by Lago-Hernandez et al., patients with chronic liver disease experiencing financial burden from medical bills had significantly higher odds unplanned emergency department visits (aOR 1.85, 95% CI 1.33–2.57).25 Similarly, financial distress in the form of cost-related medication non-adherence or medication tradeoffs was also associated with unplanned emergency department visits32 and post-transplant hospital admissions33 in two U.S.-based studies.

In the 2017 study by Stepanova et al., yearly health expenses were independently associated with a decrease (per every $10,000 USD) in the Physical Component Scores (beta, −0.50 ± 0.09) and Mental Component Scores (beta, −0.25 ± 0.10) on the Short-Form 12 health-related quality of life survey for patients with chronic liver disease.4

In a U.S. cross-sectional study of 73 caregivers of patients with chronic liver disease, loss of income due to caregiving was associated with increased depressive symptoms, anxiety and caregiver burden.35

Conceptual Framework of Financial Burden, Distress, and Toxicity in Chronic Liver Disease

Figure 2 proposes a conceptual framework for domains of financial burden and distress that are associated with financial toxicity outcomes in adult patients with chronic liver disease and their caregivers.

DISCUSSION

In this scoping review of 19 studies, we found that financial burden and distress are highly prevalent among patients with chronic liver disease and are associated with poor health outcomes for both patients and their caregivers. The prevalence of financial burden and distress in patients with chronic liver disease is comparable to rates observed in patients with other serious illnesses such as chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes.25 Patients with more advanced disease including those with HCC, hepatic encephalopathy, or multimorbidity were at particularly high risk, as were liver transplant recipients. Behavioral financial distress in the form reduced access and adherence to healthcare and other necessities may result in increased pre- and post-transplant healthcare utilization and poor health-related quality of life among patients with chronic liver disease. Unplanned hospital readmissions, uncontrolled illness, and progressive symptomatic disease may in turn be key manifestations of financial toxicity in this population. Despite the high rates of financial toxicity among patients with chronic liver disease, none of the included studies evaluated interventions to alleviate financial burden and distress.

Multiple studies revealed that a diagnosis of chronic liver disease is financially toxic not just for patients but also for their families. The cost of chronic liver disease care resulted in food insecurity, housing instability, and loss of education, assets and savings for patients and families.25,26,28,31–34 Caregivers, especially those of patients with hepatic encephalopathy, were particularly affected both in terms of out-of-pocket and time costs of family caregiving as well as changes in their employment and work productivity.21,22,28,29,31 In many studies, the loss of the patient as the primary breadwinner resulted in substantial financial burden and psychological distress for caregivers, which has been described in prior qualitative studies.36–39 These findings underscore that interventions addressing financial burden and distress for patients with chronic liver disease must also include a holistic assessment of the needs of their family unit.

Addressing financial burden and identifying financial distress in cirrhosis care will require a multilevel approach (Table 2). At the physician level, increased awareness of and routine screening for financial distress may identify patients with chronic liver disease who are at risk for financial toxicity. Patients who are underinsured, unemployed, have new hepatic encephalopathy or HCC are at particularly high risk for financial burden and may merit early screening and intervention. The question “are you having difficulty paying for your medical care?” is an effective screen for financial distress and additional tools that can be used for screening include the “Costs of Care Conversations” tool from the American College of Physicians and the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST) survey.40–43 Clinicians providing care to liver transplant recipients of working age should assess whether they have returned to work and screen for work absenteeism. Additionally, during routine medication reconciliation in outpatient visits, clinicians should discuss low-cost alternatives with patients. At the clinic and hospital level, new models of care using social workers, community health workers, pharmacists and/or financial navigators to help patients and their families navigate employment benefits and family leave, access assistance for prescriptions, unemployment and nonmedical costs, and obtain financial counseling are needed.44,45 There should be an increasing recognition of the non-medical costs of care such as time and transportation, with consideration of telehealth visits, parking vouchers, or hospital at home models of care to alleviate these burdens on patients and their caregivers.46–50 Additionally, addressing cost-related barriers to care may require the development of clinic-based strategies and clinical guidelines to increase cost transparency, guide shared decision-making around cost-benefit tradeoffs, and improve delivery of high-value hepatology care.51 At a policy and system level, promoting legislation for insurance coverage of high-cost medications such as immunosuppressive drugs, value-based drug-pricing, assistance programs for caregivers, and paid family and medical leave are needed.52–55

Table 2.

Strategies and Future Directions to Mitigate Financial Burden and Financial Distress in Chronic Liver Disease Care

| Screening for Financial Burden and Distress | Health-System Strategies | Proposed Policy Changes and Future Directions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Burden |

Identify High-Risk Populations

|

|

|

| Financial Distress | Screen for Financial Distress |

|

|

More research on the financial impact of chronic liver disease on patients and caregivers is needed in four key areas. First, the current body of evidence on financial burden, distress and toxicity in chronic liver disease is predominantly from small-sample observational studies with limited outcomes assessments which are prone to biases. There is a need for large, well-typified prospective longitudinal studies assessing different domains of financial burden and distress and causal mechanisms from the time of diagnosis of chronic liver disease to the development of relevant financial and healthcare outcomes to identify risk factors. Second, methods and measures for financial burden and distress varied widely, limiting comparisons across studies. Notably, no study used a standardized instrument such as the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity survey that has been validated in the oncology population.41,56 Third, the included studies provided limited data on race/ethnicity, insurance status, care setting (e.g. rural, urban), or other social determinants of health of the patient and/or caregiver participants. Financial burden represents just one social determinant of health that is impacted by many upstream factors, including systemic policies, socioeconomic status, insurance access, racism, and bias.57 Future research in this area should proactively recruit diverse populations with formal tracking of social determinants of health and should assess for pharmacoequity in cirrhosis care, in which all individuals, regardless of background, have access to evidence-based medications and treatments.58,59 Fourth, as the population of patients with chronic liver disease aged 65 years or older continues to increase, assessing risk factors for financial burden among the Medicare eligible population and outcomes related to costs of care at end-of-life will be an important area for future study.60–62 Lastly, future research is needed to develop and test evidence-based interventions targeting different domains of financial burden and distress.

Conclusions

Observational evidence supports the findings that financial burden and distress are highly prevalent among patients with chronic liver disease and their caregivers and are associated with poor health outcomes. Despite these findings, there is a substantial evidence gap on the measurement of patient-level financial burden and distress, causal mechanisms, and outcomes. There is a critical need for patient- and caregiver-centered interventions to alleviate financial burden and distress and reduce financial toxicity in chronic liver disease care.

Funding/Support:

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Clinical, Translational and Outcomes Research Award (NNU), Massachusetts General Hospital Physician Scientist Development Award (NNU), NIH NIA 1R01AG059183 (JCL), NIDDK Undergraduate Clinical Scholars Program R25DK108711 (MS). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- CAD

Canadian Dollars

- HBV

Hepatitis B Virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C Virus

- HCC

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- MEPS

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

- MELD

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NHIS

National Health Interview Survey

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- USD

United States Dollars

Database:

Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily, Ovid MEDLINE and Versions(R) 1946 to Present

| # | Query |

|---|---|

| 1 | liver diseases/ or exp Hepatic Insufficiency/ or exp Liver Cirrhosis/ or exp Liver Transplantation/ or exp Liver Neoplasms/ or exp fatty liver/ |

| 2 | (“Liver Disease” or “liver diseases” or “liver failure” or “liver fibrosis” or cirrhosis or “liver transplant” or “liver transplants” or “liver transplantation” or “liver cell cancer” or “liver cell cancers” or “liver cancer” or “liver cancers” or cirrhosis or “hepatocellular carcinoma” or HCC or hepatoma or hepatomas or “hepatic encephalopathy” or “hepatic insufficiency” or “fatty liver”).ti,ab. |

| 3 | 1 or 2 |

| 4 | exp “Cost of Illness”/ or exp Health Care Costs/ or exp Health Expenditures/ or exp financing personal/ |

| 5 | (financial adj4 burden).ti,ab. |

| 6 | ((cost or costs) adj2 (treatment or care or illness or healthcare or “health care” or direct)).ti,ab. |

| 7 | (“Financial security” or “Financial status” or “Financial toxicity” or “Financial stress” or “Financial strain” or “Financial hardship*” or “Financial distress” or “Financial difficult*” or “Financial concern*” or “financial consequences” or “Financial costs” or Finances or “Out of pocket” or Copay* or “co pay*” or “cost sharing” or Bankruptcy or “medical debt” or “medical expenses” or “medical expenditures” or “health care expenditure*” or “healthcare expenditure*” or “Socioeconomic status” or “economic status” or “economic consequences” or “Socioeconomic burden” or “economic hardship*” or “economic burden”).ti,ab. |

| 8 | (Patient* or Caregiver* or carers or Family or families or Personal or individual or individuals).ti,ab. |

| 9 | exp “Patients”/ or exp “Caregivers”/ or exp “Family”/ |

| 10 | 5 or 6 or 7 |

| 11 | 8 or 9 |

| 12 | 10 and 11 |

| 13 | 4 or 12 |

| 14 | 3 and 13 |

Database:

Embase.com (via Elsevier)

| # | Query |

|---|---|

| 1 | ‘chronic liver disease’/exp OR ‘liver failure’/de OR ‘liver cirrhosis’/exp OR ‘liver cancer’/exp OR ‘fatty liver’/exp OR ‘liver fibrosis’/de OR ‘liver transplantation’/exp OR ‘hepatic encephalopathy’/exp |

| 2 | ‘liver disease’:ab,ti OR ‘liver diseases’:ab,ti OR ‘liver failure’:ab,ti OR ‘liver fibrosis’:ab,ti OR ‘liver transplant’:ab,ti OR ‘liver transplants’:ab,ti OR ‘liver transplantation’:ab,ti OR ‘liver cell cancer’:ab,ti OR ‘liver cell cancers’:ab,ti OR ‘liver cancer’:ab,ti OR ‘liver cancers’:ab,ti OR cirrhosis:ab,ti OR ‘hepatocellular carcinoma’:ab,ti OR hcc:ab,ti OR hepatoma:ab,ti OR hepatomas:ab,ti OR ‘hepatic encephalopathy’:ab,ti OR ‘hepatic insufficiency’:ab,ti OR ‘fatty liver’:ab,ti |

| 3 | #1 OR #2 |

| 4 | ‘financial burden’/de OR ‘financial stress’/exp OR ‘out of pocket cost’/de OR ‘out of pocket expenditure’/de OR ‘financial management’/de OR ‘economic burden’/de OR ‘cost of illness’/de OR ‘health care cost’/exp OR ‘personal finance’/exp |

| 5 | (financial NEAR/4 burden):ab,ti |

| 6 | ((cost OR costs) NEAR/2 (treatment OR care OR illness OR healthcare OR ‘health care’ OR direct)):ab,ti |

| 7 | ‘financial security’:ab,ti OR ‘financial status’:ab,ti OR ‘financial toxicity’:ab,ti OR ‘financial stress’:ab,ti OR ‘financial strain’:ab,ti OR ‘financial hardship*’:ab,ti OR ‘financial distress’:ab,ti OR ‘financial difficult*’:ab,ti OR ‘financial concern*’:ab,ti OR ‘financial consequences’:ab,ti OR ‘financial costs’:ab,ti OR finances:ab,ti OR ‘out of pocket’:ab,ti OR copay*:ab,ti OR ‘co pay*’:ab,ti OR ‘cost sharing’:ab,ti OR bankruptcy:ab,ti OR ‘medical debt’:ab,ti OR ‘medical expenses’:ab,ti OR ‘medical expenditures’:ab,ti OR ‘health care expenditure*’:ab,ti OR ‘healthcare expenditure*’:ab,ti OR ‘socioeconomic status’:ab,ti OR ‘economic status’:ab,ti OR ‘economic consequences’:ab,ti OR ‘socioeconomic burden’:ab,ti OR ‘economic hardship*’:ab,ti OR ‘economic burden’:ab,ti |

| 8 | patient*:ab,ti OR caregiver*:ab,ti OR carers:ab,ti OR family:ab,ti OR families:ab,ti OR personal:ab,ti OR individual:ab,ti OR individuals:ab,ti |

| 9 | ‘patient’/exp OR ‘caregiver’/de OR ‘family’/de |

| 10 | #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 |

| 11 | #8 OR #9 |

| 12 | #3 AND #10 AND #11 |

| 13 | #3 AND #10 AND #11 AND ([medline]/lim OR [pubmed-not-medline]/lim) |

| 14 | #13 NOT #13 |

Database:

Cochrane Library via Ovid

| # | Query |

|---|---|

| 1 | liver diseases/ or exp Hepatic Insufficiency/ or exp Liver Cirrhosis/ or exp Liver Transplantation/ or exp Liver Neoplasms/ or exp fatty liver/ |

| 2 | (“Liver Disease” or “liver diseases” or “liver failure” or “liver fibrosis” or cirrhosis or “liver transplant” or “liver transplants” or “liver transplantation” or “liver cell cancer” or “liver cell cancers” or “liver cancer” or “liver cancers” or cirrhosis or “hepatocellular carcinoma” or HCC or hepatoma or hepatomas or “hepatic encephalopathy” or “hepatic insufficiency” or “fatty liver”).ti,ab. |

| 3 | 1 or 2 |

| 4 | exp “Cost of Illness”/ or exp Health Care Costs/ or exp Health Expenditures/ or exp financing personal/ |

| 5 | (financial adj4 burden).ti,ab. |

| 6 | ((cost or costs) adj2 (treatment or care or illness or healthcare or “health care” or direct)).ti,ab. |

| 7 | (“Financial security” or “Financial status” or “Financial toxicity” or “Financial stress” or “Financial strain” or “Financial hardship*” or “Financial distress” or “Financial difficult*” or “Financial concern*” or “financial consequences” or “Financial costs” or Finances or “Out of pocket” or Copay* or “co pay*” or “cost sharing” or Bankruptcy or “medical debt” or “medical expenses” or “medical expenditures” or “health care expenditure*” or “healthcare expenditure*” or “Socioeconomic status” or “economic status” or “economic consequences” or “Socioeconomic burden” or “economic hardship*” or “economic burden”).ti,ab. |

| 8 | (Patient* or Caregiver* or carers or Family or families or Personal or individual or individuals).ti,ab. |

| 9 | exp “Patients”/ or exp “Caregivers”/ or exp “Family”/ |

| 10 | 5 or 6 or 7 |

| 11 | 8 or 9 |

| 12 | 10 and 11 |

| 13 | 4 or 12 |

| 14 | 3 and 13 |

| 15 | Remove duplicates from 14 |

Database:

Web of Science Core Collection via Clarivate

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=All years

| # | Query |

|---|---|

| 1 | TOPIC: ((“Liver Disease” or “liver diseases” or “liver failure” or “liver fibrosis” or cirrhosis or “liver transplant” or “liver transplants” or “liver transplantation” or “liver cell cancer” or “liver cell cancers” or “liver cancer” or “liver cancers” or cirrhosis or “hepatocellular carcinoma” or HCC or hepatoma or hepatomas or “hepatic encephalopathy” or “hepatic insufficiency” or “fatty liver”)) |

| 2 | TOPIC: (financial NEAR/4 burden) |

| 3 | TOPIC: ((cost or costs) NEAR/2 (treatment or care or illness or healthcare or “health care” or direct)) |

| 4 | TOPIC: ((“Financial security” or “Financial status” or “Financial toxicity” or “Financial stress” or “Financial strain” or “Financial hardship*” or “Financial distress” or “Financial difficult*” or “Financial concern*” or “financial consequences” or “Financial costs” or Finances or “Out of pocket” or Copay* or “co pay*” or “cost sharing” or Bankruptcy or “medical debt” or “medical expenses” or “medical expenditures” or “health care expenditure*” or “healthcare expenditure*” or “Socioeconomic status” or “economic status” or “economic consequences” or “Socioeconomic burden” or “economic hardship*” or “economic burden”)) |

| 5 | TOPIC: ((Patient* or Caregiver* or carers or Family or families or Personal or individual or individuals)) |

| 6 | #2 OR #3 OR #4 |

| 7 | #6 AND #5 AND #1 |

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: No authors report any financial disclosures or conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collaborators GDaIIaP. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. November 10 2018;392(10159):1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlsen TH, Sheron N, Zelber-Sagi S, et al. The EASL-Lancet Liver Commission: protecting the next generation of Europeans against liver disease complications and premature mortality. Lancet. January 01 2022;399(10319):61–116. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01701-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asrani SK, Kouznetsova M, Ogola G, et al. Increasing Health Care Burden of Chronic Liver Disease Compared With Other Chronic Diseases, 2004–2013. Gastroenterology. September 2018;155(3):719–729.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stepanova M, De Avila L, Afendy M, et al. Direct and Indirect Economic Burden of Chronic Liver Disease in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. May 2017;15(5):759–766.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, Part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park). Feb 2013;27(2):80–1, 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khera R, Valero-Elizondo J, Nasir K. Financial Toxicity in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in the United States: Current State and Future Directions. J Am Heart Assoc. Oct 20 2020;9(19):e017793. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones SM, Henrikson NB, Panattoni L, Syrjala KL, Shankaran V. A theoretical model of financial burden after cancer diagnosis. Future Oncol. Dec 2020;16(36):3095–3105. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-0547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slavin SD, Khera R, Zafar SY, Nasir K, Warraich HJ. Financial burden, distress, and toxicity in cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. August 2021;238:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A, Chan RJ. A Systematic Review of Financial Toxicity Among Cancer Survivors: We Can’t Pay the Co-Pay. Patient. June 2017;10(3):295–309. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0204-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J Natl Cancer Inst. February 2017;109(2)doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francoeur RB. Cumulative financial stress and strain in palliative radiation outpatients: The role of age and disability. Acta Oncol. 2005;44(4):369–81. doi: 10.1080/02841860510029761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381–90. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005-February-01 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witte J, Mehlis K, Surmann B, et al. Methods for measuring financial toxicity after cancer diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review and its implications. Ann Oncol. Jul 1 2019;30(7):1061–1070. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. December 05 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Inflation Calculator. Consumer Price Index Data from 1913 to 2022. Accessed January 31, 2022. https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/

- 17.Bank of Canada. Inflation Calculator. Accessed January 31, 2022. www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/

- 18.Rahman MM, Zhang C, Swe KT, et al. Disease-specific out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in urban Bangladesh: A Bayesian analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0227565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Che YH, Chongsuvivatwong V, Li L, et al. Financial burden on the families of patients with hepatitis B virus-related liver diseases and the role of public health insurance in Yunnan province of China. Public Health. Jan 2016;130:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJ. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. Jul 12 2003;362(9378):111–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rakoski MO, McCammon RJ, Piette JD, et al. Burden of cirrhosis on older Americans and their families: analysis of the health and retirement study. Hepatology. Jan 2012;55(1):184–91. doi: 10.1002/hep.24616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Federico CA, Hsu PC, Krajden M, et al. Patient time costs and out-of-pocket costs in hepatitis C. Liver Int. May 2012;32(5):815–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02722.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peretz D, Grubert Van Iderstine M, Bernstein M, Minuk GY. The Psychological and Financial Impact of Long-distance Travel for Liver Transplantation. Transplant Direct. Jun 2020;6(6):e558. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigue JR, Reed AI, Nelson DR, Jamieson I, Kaplan B, Howard RJ. The financial burden of transplantation: a single-center survey of liver and kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. Aug 15 2007;84(3):295–300. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000269797.41202.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lago-Hernandez C, Nguyen NH, Khera R, Loomba R, Asrani SK, Singh S. Financial Hardship From Medical Bills Among Adults With Chronic Liver Diseases: National Estimates From the United States. Hepatology. Mar 26 2021;doi: 10.1002/hep.31835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh SP, Padhi PK, Narayan J, et al. Socioeconomic impact of alcohol in patients with alcoholic liver disease in eastern India. Indian J Gastroenterol. Nov 2016;35(6):419–424. doi: 10.1007/s12664-016-0699-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shrestha D, Rathi S, Grover S, et al. Factors Affecting Psychological Burden on the Informal Caregiver of Patients With Cirrhosis: Looking Beyond the Patient. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020 Jan-Feb 2020;10(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bajaj JS, Wade JB, Gibson DP, et al. The Multi-Dimensional Burden of Cirrhosis and Hepatic Encephalopathy on Patients and Caregivers. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2011/09// 2011;106(9):1646–1653. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bajaj JS, Riggio O, Allampati S, et al. Cognitive dysfunction is associated with poor socioeconomic status in patients with cirrhosis: an international multicenter study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Nov 2013;11(11):1511–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beal EW, Tumin D, Mumtaz K, et al. Factors contributing to employment patterns after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. June 2017;31(6)doi: 10.1111/ctr.12967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hareendran A, Devadas K, Sreesh S, et al. Quality of life, caregiver burden and mental health disorders in primary caregivers of patients with Cirrhosis. Liver Int. December 2020;40(12):2939–2949. doi: 10.1111/liv.14614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lago-Hernandez C, Nguyen NH, Khera R, Loomba R, Asrani SK, Singh S. Cost-Related Nonadherence to Medications Among US Adults With Chronic Liver Diseases. Mayo Clin Proc. Jun 10 2021;doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serper M, Reese PP, Patzer RR, Levitsky J, Wolf MS. The prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of medication trade-offs in kidney and liver transplant recipients: a pilot study. Transpl Int. August 2018;31(8):870–879. doi: 10.1111/tri.13098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pol SJ, Snyder J, Anthony SJ. “Tremendous financial burden”: Crowdfunding for organ transplantation costs in Canada. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0226686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolden L, Wicks MN. Predictors of mental health, subjective burden, and rewards in family caregivers of patients with chronic liver disease. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. Apr 2010;24(2):89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2009.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ufere NN, Donlan J, Indriolo T, et al. Burdensome Transitions of Care for Patients with End-Stage Liver Disease and Their Caregivers. Dig Dis Sci. September 2021;66(9):2942–2955. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06617-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Künzler-Heule P, Beckmann S, Mahrer-Imhof R, Semela D, Händler-Schuster D. Being an informal caregiver for a relative with liver cirrhosis and overt hepatic encephalopathy: a phenomenological study. J Clin Nurs. Sep 2016;25(17–18):2559–68. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fabrellas N, Moreira R, Carol M, et al. Psychological Burden of Hepatic Encephalopathy on Patients and Caregivers. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. Apr 2020;11(4):e00159. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hudson B, Hunt V, Waylen A, McCune CA, Verne J, Forbes K. The incompatibility of healthcare services and end-of-life needs in advanced liver disease: A qualitative interview study of patients and bereaved carers. Palliat Med. May 2018;32(5):908–918. doi: 10.1177/0269216318756222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shih YT, Nasso SF, Zafar SY. Price Transparency for Whom? In Search of Out-of-Pocket Cost Estimates to Facilitate Cost Communication in Cancer Care. Pharmacoeconomics. March 2018;36(3):259–261. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0613-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer. Oct 15 2014;120(20):3245–53. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Healthcare Transparency: Talking to Patients about the Cost of Their Healthcare. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.acponline.org/clinical-information/high-value-care/resources-for-clinicians/cost-of-care-conversations

- 43.New York Chapter of the American College of Physicians. Cost of Care Resources. Accessed April 21, 2022. https://www.nyacp.org/files/NYACPs%20Financial%20Screening%20Questions.pdf

- 44.Watabayashi K, Steelquist J, Overstreet KA, et al. A Pilot Study of a Comprehensive Financial Navigation Program in Patients With Cancer and Caregivers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. October 2020;18(10):1366–1373. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ufere NN, Hinson J, Finnigan S, et al. The Impact of Social Workers in Cirrhosis Care: a Systematic Review. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology. 2022/April/19 2022;doi: 10.1007/s11938-022-00381-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sherman CB, Said A, Kriss M, et al. In-Person Outreach and Telemedicine in Liver and Intestinal Transplant: A Survey of National Practices, Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019, and Areas of Opportunity. Liver Transpl. October 2020;26(10):1354–1358. doi: 10.1002/lt.25868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serper M, Cubell AW, Deleener ME, et al. Telemedicine in Liver Disease and Beyond: Can the COVID-19 Crisis Lead to Action? Hepatology. August 2020;72(2):723–728. doi: 10.1002/hep.31276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Serper M, Nunes F, Ahmad N, Roberts D, Metz DC, Mehta SJ. Positive Early Patient and Clinician Experience with Telemedicine in an Academic Gastroenterology Practice During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gastroenterology. October 2020;159(4):1589–1591.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital-Level Care at Home for Acutely Ill Adults: a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gen Intern Med. May 2018;33(5):729–736. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4307-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee A, Shah K, Chino F. Assessment of Parking Fees at National Cancer Institute-Designated Cancer Treatment Centers. JAMA Oncol. August 01 2020;6(8):1295–1297. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shah ED, Siegel CA. Systems-Based Strategies to Consider Treatment Costs in Clinical Practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. May 2020;18(5):1010–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen ML. The Growing Costs and Burden of Family Caregiving of Older Adults: A Review of Paid Sick Leave and Family Leave Policies. Gerontologist. June 2016;56(3):391–6. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shah ED, Saini SD, Chey WD. Value-based Pricing for Rifaximin Increases Access of Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Diarrhea to Therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. December 2019;17(13):2687–2695.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.02.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leykum LK, Penney LS, Dang S, et al. Recommendations to Improve Health Outcomes Through Recognizing and Supporting Caregivers. J Gen Intern Med. Jan 03 2022;doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07247-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gill JS, Formica RN, Murphy B. Passage of the Comprehensive Immunosuppressive Drug Coverage for Kidney Transplant Patients Act-a Chance to Celebrate and Reflect. J Am Soc Nephrol. Mar 02 2021;doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020121811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer. February 01 2017;123(3):476–484. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kardashian A, Wilder J, Terrault NA, Price JC. Addressing Social Determinants of Liver Disease During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond: A Call to Action. Hepatology. February 2021;73(2):811–820. doi: 10.1002/hep.31605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Essien UR, Dusetzina SB, Gellad WF. A Policy Prescription for Reducing Health Disparities-Achieving Pharmacoequity. JAMA. Nov 09 2021;326(18):1793–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.17764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tapper EB, Essien UR, Zhao Z, Ufere NN, Parikh ND. Racial and ethnic disparities in rifaximin use and subspecialty referrals for patients with hepatic encephalopathy in the United States. J Hepatol. Mar 28 2022;doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Asrani SK, Hall L, Hagan M, et al. Trends in Chronic Liver Disease-Related Hospitalizations: A Population-Based Study. Am J Gastroenterol. January 2019;114(1):98–106. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0365-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kochar B, Ufere NN, Ritchie CS, Lai JC. The 5Ms of Geriatrics in Gastroenterology: The Path to Creating Age-Friendly Care for Older Adults With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Cirrhosis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. January 12 2022;13(1):e00445. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Narang AK, Nicholas LH. Out-of-Pocket Spending and Financial Burden Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Cancer. JAMA Oncol. Jun 01 2017;3(6):757–765. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu CY, Ross-Degnan D, Zhang F, et al. Cost burden of hepatitis C virus treatment in commercially insured patients. Am J Manag Care. December 01 2019;25(12):e379–e387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]