Abstract

Background:

Over one-half of older adults are discharged to the community after emergency department (ED) visits, and studies have shown there is increased risk of adverse health outcomes in the immediate post-discharge period. Understanding the experiences of older adults during ED-to-community care transitions has the potential to improve geriatric emergency clinical care and inform intervention development. We therefore sought to assess barriers experienced by older adults during ED-to-community care transitions.

Methods:

We conducted a qualitative analysis of community-dwelling cognitively intact patients aged 65 years and older receiving care in four diverse EDs from a single U.S. healthcare system. We constructed a conceptual framework a priori to guide the development and iterative revision of a codebook, used purposive sampling, and conducted recorded, semi-structured interviews using a standardized guide. Two researchers coded the professionally transcribed data using a combined deductive and inductive approach and analyzed transcripts to identify dominant themes and representative quotations.

Results:

Among 25 participants, 20 (80%) were women and 17 (68%) were white. We identified four barriers during the ED-to-community care transition: 1) ED discharge process was abrupt with missing information regarding symptom explanation and performed testing, 2) navigating follow-up outpatient clinical care was challenging, 3) new physical limitations and fears hinder performance of baseline activities, and 4) major and minor ramifications for caregivers impact an older adult’s willingness to request or accept assistance.

Conclusions:

Older adults identified barriers to successful ED-to-community care transitions that can inform the development of novel and effective interventions.

Keywords: emergency department, care transition, barrier, qualitative, older adults

Introduction

Older adults, defined as those aged 65 years and older, accounted for over 23 million emergency department (ED) visits in 2018, representing nearly 18% of all ED visits nationally.1 Over one-half of older adults seeking care in the ED are discharged back to the community setting, including their own homes.2 With varying time horizons in prior analyses, the days-weeks after an ED visit has been shown to impart substantial vulnerability and risk for older adults, with identified adverse health outcomes of ED revisits, hospital admission, and mortality.3–6

Calls to improve ED-to-community care transitions for older adults have increased in recent years. ED care transitions have been prioritized within developed residency competencies,7 the 2014 Geriatric ED Guidelines,8 the 2017 National Quality Forum ED Transitions of Care Report,9 the 2018 launch of the American College of Emergency Physicians geriatric ED accreditation process,10 and funded initiatives from the National Institute on Aging including the Geriatric Emergency care Applied Research Network.11–13 To date, effective ED-to-community care transition interventions have largely proven elusive. Recent work has highlighted an overall lack of high-quality data to guide recommendations about optimal ED-to-community care transition strategies for older adults.14–18 With the extant literature demonstrating limited relevant qualitative data,19,20 hypothesis-generating qualitative research may identify potential opportunities to improve care transitions, which could help generate novel ED-to-community care transition interventions to be tested and implemented among older adults.

Addressing a critical knowledge gap, we sought to assess the barriers experienced by older adults during ED-to-community care transitions. Such understanding has the potential to improve geriatric emergency care by providing clinicians valuable information about how to improve the ED clinical care and the discharge process by offering researchers foundational data to inform the development of effective ED-to-community care transition interventions targeting older adults.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This report shares the qualitative findings of a larger ongoing exploratory sequential mixed-methods study to develop and validate a novel patient-reported outcome measure focused on ED-to-community care transitions among older adults. Methods and results are reported in accordance with the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ).21 This study protocol was approved by the Yale University institutional review board.

We recruited participants from four hospital EDs: a Level I trauma center/tertiary referral hospital, two academic community hospitals, and a freestanding ED within the same health system. At the time of investigation, one of the EDs was accredited as a Level 3 Geriatric ED. Inclusion criteria for patients were: 1) age 65 or older, 2) anticipated discharge after the ED encounter, and 3) fluent in English or Spanish. Exclusion criteria included: 1) residing in a nursing home, skilled nursing facility, rehabilitation center, or other extended care facility, 2) cognitive impairment, or 3) determination by the treating clinician that the candidate participant was inappropriate for the study due to critical illness, contact precautions, altered mental status, and intoxication among other reasons.

In this work, we chose to focus on cognitively intact older adults, as the unique experiences of those with cognitive impairment and caregivers would likely identify separate barriers, facilitators, and themes during the ED-to-community care transition. Cognitive impairment was identified by a diagnosis of dementia or cognitive impairment listed within the ‘Problem List’ of the electronic medical record. To capture potential participants with undiagnosed or undocumented cognitive impairment, we additionally performed cognitive assessments of participants using the validated 4AT and AD8 screening tools.22–27 The 4AT is scored from 0–12 and tests for cognitive impairment, including delirium. A score of ≥4 suggests possible delirium, a score of 1–3 suggests possible cognitive impairment, and a score of 0 suggests delirium or severe cognitive impairment is unlikely. Given our intentional focus on older adults without cognitive impairment, we excluded those participants with a score of ≥4. We then performed the AD8 with a family member or friend contact person listed in the electronic health record by telephone. Previously assessed in the ED,22,23 the AD8 is a screening tool more specifically focused on dementia with 8 questions and a score range of 0 to 8. Aligned with prior research,24 a score of ≥2 on the caregiver-completed AD8 was noted to suggest cognitive impairment (including possible dementia) and resulted in study exclusion.

Procedures

Participants were approached and screened by a research assistant (I.U.) while in the ED, with the maximum variation strategy of purposive sampling by age, self-reported race, and chief complaint to capture a wide range of perspectives and to ensure generalizability of findings. After obtaining informed consent, I.U. collected sociodemographic and contact information. Each participant received a $25 gift card after study participation.

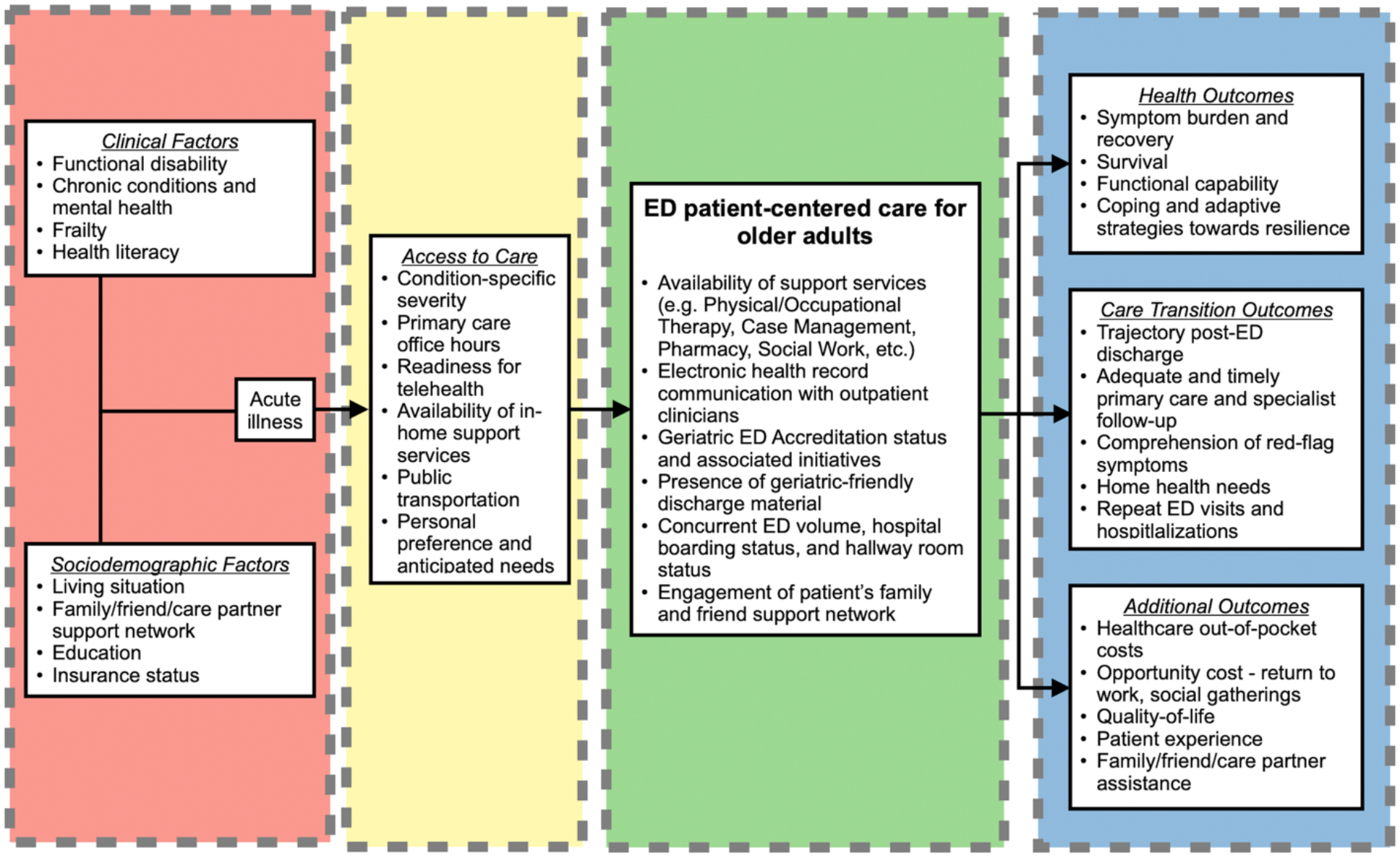

Following the ED visit, a trained qualitative interviewer of older adults (K.H.B.) contacted participants by telephone to complete one-on-one interviews at a location of the participant’s choosing. Participants were contacted within 3–7 days of the initial ED visit, as we felt that cognitively intact adults would be able to remember reliably the details of the acute illness prompting the ED visit, while also allowing for a reasonable time period to elapse for them to experience the ED-to-community transition. A semi-structured interview guide was developed and pilot tested based on the existing literature, our study team’s content expertise, and a newly-developed conceptual framework of ED-to-community care transitions among older adults (Figure 1) based on literature review, concept mapping, and expert consensus agreement. All interviews were audio-recorded, professionally transcribed, and redacted. Intended to provide essential context to inform data analysis, field notes were taken immediately after each interview regarding general comments, contributions to the richness of the interview, as well as challenges or opportunities related to the qualitative content.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model and framework for ED-to-community care transitions among older adults

Note: Clinical and sociodemographic factors (red) as well as access to care considerations (yellow) that conceptually drive ED presentation by older adults during an acute illness are shown, in addition to potential in-ED initiatives and broader contextual considerations (green) that may contribute to subsequent patient-centered outcomes (blue).

Data Analysis

We used an iterative process of thematic analysis to synthesize the data, identify patterns, and develop themes across the interviews.28 Specifically, we used a combined deductive and inductive approach,29 where concepts in the standardized interview guide were used to structure the initial codebook and data from interviews were incorporated (Supplemental Text S1). The coding team was composed of C.J.G. and P.T.S., two emergency physicians with expertise in care transitions among older adults. C.J.G. has completed formal training in qualitative research. Initially, the two investigators independently coded five transcripts and met to review coding and refine the coding structure. Both researchers coded 100% of the data. Coders obtained consensus on major topics and subtopics from the remainder of the research team and applied the final coding structure to all transcripts. C.J.G. and P.T.S. iteratively reviewed coded data, compiled separate memos, and identified themes using NVivo software (version 12; QSR International, Victoria, Australia). Recruitment, interviewing, and coding occurred concurrently until data saturation was reached. Coders shared findings and obtained team consensus of representative quotes and contextualized findings.

Results

We interviewed 25 older adults between November 2021 and February 2022. On average, interviews lasted 21 minutes, with a range of 12 to 38 minutes. Participants’ mean age was 72.2 years (standard deviation [SD] = 3.8 years), 48% were married, and 32% identified as African American. Participants presented to the ED for a variety of grouped chief complaint reasons, including: cardiopulmonary (20%), musculoskeletal (32%), gastrointestinal (24%), neurologic (8%), or other (16%) reasons (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 25)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 5 (20) |

| Female | 20 (80) |

| Age, mean years (SD) | 72.2 (3.8) |

| Race | |

| White | 17 (68) |

| African American | 8 (32) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 12 (48) |

| Single | 4 (16) |

| Divorced | 8 (32) |

| Widowed | 1 (4) |

| No. of Chronic Conditions, mean (SD) | 2.1 (1.3) |

| ED Chief Complaint Category | |

| Cardiopulmonary | 5 (20) |

| Musculoskeletal | 8 (32) |

| Gastrointestinal | 6 (24) |

| Neurologic | 2 (8) |

| Other | 4 (16) |

| Emergency Severity Index, mean (SD) | 2.8 (0.4) |

Four themes emerged: 1) ED discharge process was abrupt with missing information regarding symptom explanation and performed testing, 2) navigating follow-up outpatient clinical care was challenging, 3) new physical limitations and fears hinder performance of baseline activities, and 4) major and minor ramifications for caregivers impact an older adult’s willingness to request or accept assistance. Themes, subthemes, and representative quotations are available in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of themes and representative quotations

| Theme/Subtheme | Representative Quotation |

|---|---|

| 1. ED discharge process was abrupt and lacked explanation | |

| Symptom explanation was often absent | I think I would’ve—when I went in, the doctors had to do what they had to do, of course, but at least explain to me or try to explain to me what could have caused the problem. (Pt 44) |

| An explanation of test results was often not provided | [They] didn’t tell me what the results of the CAT scan were. They didn’t tell me I had an infection. They didn’t tell me they called in a prescription. That was a lot of information that I should have gotten. (Pt 118) |

| Abruptness | There’s a lot of pressure to kick people out because we were everywhere. The emergency room was very overloaded. I don’t remember the period of time in between, which couldn’t have been too long before they said, “Okay. You’re getting discharged,” brought me my sling, brought me my papers, said, “Night.” (Pt 93) |

| 2. Barriers to navigating follow-up outpatient clinical care | |

| Discharge paperwork was cumbersome, lengthy, and often not helpful | I haven’t had a chance to look at that paperwork. I have to look at it later. She told me about it and showed it to me, but it was just so much. (Pt 131) |

| Conflicting instructions create uncertainty among older adults | Really, they didn’t give me any instructions when I left. I saw them in the notes. Mostly the difference was I was supposed to do some exercises, which the emergency room didn’t know because the doctor hadn’t gotten back. There was an internal miscommunication, I would say, there. (Pt 93) |

| Subsequent accessibility to usual clinician was a common barrier | You know anybody, you call, “Oh, well, we’ll get an appointment in three weeks,” and this. It’s hard, so whatever. (Pt 109) |

| Desire for a follow-up telephone call after ED care | The only thing that I would say, going to the emergency room, I think, maybe, a follow-up phone call would be good. (Pt 138) |

| Patient need to infer next steps and take care into their own hands | Really, they didn’t give me any instructions when I left. I saw them in the notes. (Pt 93) |

| 3. New physical limitations and fear of completing prior activities | |

| New limitations to baseline functional status | I don’t know what’s wrong with me, but just lying in bed makes me feel better, so that’s what I’m doing. It’s horrible. Who wants to lie in bed all day? I’m an active person. Two years ago, I was doing Zumba twice a week, and now I’m lying in bed. (Pt 109) |

| New pauses to the day or completing tasks slower are common after an ED visit | When I get one of these spells, I have to lay down for like an hour and wait for it to pass, so it’s limiting what I can do somewhat, where going out I’m careful not to try to do too much. (Pt 47) |

| Mental hesitancy | I’m afraid of it [symptomatic dizziness] and because I don’t want to get that again. What I do is really take it very—a lot of precautions. I use a lot of precautions if I do anything. (Pt 131) |

| 4. Hesitancy to accept the potential need for formal and informal family/friend caregiver assistance | |

| Perceived frustration among family caregivers | She’s getting annoyed with me. My daughter is frustrated now. She’s not only taking care of her father, who had a stroke, but she’s taking care of her mother who up until a year ago was perfectly healthy and could do everything. Now I’m just a waste. (Pt 109) |

| Reliance on family caregivers and friends for support during recovery | I have to be really nice to my wife, or I can’t tie my shoes. Anything that needed two hands above my waist, I could not do, so my wife’s had to help me put coats—I can’t put socks on. (Pt 93) |

| Impact on lives of family caregivers | Still, I felt so bad for him [son] because he has a life. He was supposed to be at work, he took off from work. (Pt 114) |

| Varied desire, need for, and perceived benefit from formal caregiver assistance | The very nice woman said they were going to make a referral to the VNA [Visiting Nurse Association]. I said, “I don’t think I really need one,” because I have people at home. The VNA called me Friday night and wanted to come out the next day. I said, “No, that’s okay.” I think I took her by surprise. (Pt 93) |

ED Discharge Process

Interviewees reported that a lack of symptom and test explanation as well as the overall abruptness of the discharge process contributed to the concerns regarding the ED discharge process. Participants often felt that they were left to determine next steps on their own:

What they didn’t do was I didn’t really get any understanding of what was happening in my left arm. In the end I figured it out myself after a couple of days.

(Pt 55)

Interviewer: Were you given any instructions when you left?

Interviewee: Yeah, call my primary and “Take Tylenol if you have to.” I’m just leaving urgent care right now because I’m still having the same problem. I must say, the lady that took care of me today gave me more attention and explained more to me than when I was in the emergency room. (Pt 44)

Participants recognized that definitive answers to the causes of their symptoms were often not possible during ED evaluation. However, many expressed a desire for better explanations of the potential underlying etiologies of symptoms and reasoning for specific diagnostic testing. In the context of severe ED crowding and boarding, several participants felt as if they were rushed out of the ED given the high volumes of people seeking emergency care, with one participant stating:

It was like, “We’re seeing you. We’re done seeing so. Now you can go home.” That’s how I felt.

(Pt 44)

Barriers to Navigating Follow-Up Care

Older adults identified several barriers to navigating outpatient follow-up clinic care. Most common across participants was the sentiment that ED discharge paperwork was cumbersome, lengthy, and not helpful. One participant commented on the overwhelming amount of paperwork provided to them:

Oh, they gave me a whole pile of them, and, “If you start to feel this way again, come back.” To be honest with you, I know what to do, and this was something of an anomaly. I didn’t read all the paperwork.

(Pt 154)

Additional barriers included conflicting instructions from different staff members, limited accessibility to familiar outpatient providers, desire for a telephone call follow-up from the ED, and the need for the patient to infer the next steps and take care into their own hands. One older adult described how important findings that required follow-up were not discussed during the evaluation of emergent conditions in the ED setting.

They called me after I’d come home and said, “There is a lump in your parotid gland, and you need to get that looked at right away.” Unfortunately, they didn’t give me any information. Do I contact an ENT? Do I contact a neurologist? I had to fumble around until I found the right doctor to see. That can be a problem, not giving people adequate follow-up, directing them where to go, I think.

(Pt 154)

New Physical Limitations and Fears

After an ED visit, older adults reported various new disabilities that required unforeseen changes to their daily lives. Most apparent were the physical limitations to completing activities of daily living. Two participants requiring a sling after an upper extremity injury reported similar experiences:

There’s some clothing I can’t put on. Basically, I’m right-handed, so that’s good, but my left-hand does more than I thought it did… It took a little while for me to figure out how to sleep.

(Pt 93)

Of course, with one hand in a sling, it’s like being a one-armed paper hanger. You’re not very useful. I found even going to the bathroom and pulling down your pants in your pajamas, that’s more awkward. They said non-weight bearing, so my daughter served me my meals, even if it was a bowl of cereal.

(Pt 71)

Older adults were also more psychologically cautious during the acute recovery period after an ED visit. Several participants identified fears completing daily tasks, with concern that their previous symptoms would recur. One participant expressed her fear for recurrence of epistaxis:

Mentally, you’re thinking, “Oh, should I do a load of wash? Can I lift this up?” No, I don’t…Like I said, there’s been no sign that it’s going to bleed again, and we’ve had two cold nights. I think I’m out of the woods now. You never know.

(Pt 14)

Acceptance of Formal and Informal Assistance

Participants had varied experiences with requesting and accepting formal or informal assistance from caregivers post-ED discharge. Several older adults felt that the arrangement of formal Visiting Nurse Association (VNA) services would be beneficial, while others felt their illness did not require that level of care and they preferred no help.

Participants reported the impact of their acute illness on their family members and friends serving as informal caregivers. Participants often relied on family members and friends for support after discharge. Several reported that this reliance often resulted in tangible job, financial, family, and social life implications for informal caregivers. Two participants stated:

Still, I felt so bad for him [son] because he has a life. He was supposed to be at work, he took off from work.

(Pt 114)

My daughter’s doing the laundry. She’s doing the shopping. The only thing I could do is write out my Christmas cards.

(Pt 71)

For some participants and their informal caregivers, the ED visit and associated acute illness was often another more noticeable step down on the steadily declining functional trajectory. Older adults internalized frustrations from burdened family member caregivers during the care transition after an ED visit, with one stating:

She’s getting annoyed with me. My daughter is frustrated now. She’s not only taking care of her father, who had a stroke, but she’s taking care of her mother who up until a year ago was perfectly healthy and could do everything. Now I’m just a waste.

(Pt 109)

Discussion

This qualitative study revealed barriers experienced by older adults navigating the ED-to-community care transition. These barriers included an abrupt ED discharge process and suboptimal explanation of the underlying etiology of symptoms and reasoning for laboratory testing and imaging; difficulties navigating follow-up outpatient clinical care; new physical limitations and fears during the recovery; and hesitancy to accept the potential need for formal or informal family/friend caregiver assistance. Findings have implications for expectant management discussions within ED discharge processes and for the development of ED-to-community care transition interventions targeting identified barriers.

Our work builds upon the extant literature by elucidating salient and generalizable barriers experienced by older adults experiencing ED-to-community care transitions. Prior qualitative research has relied on staff perceptions of older adults,30 focused on modifiable reasons for ED utilization rather than ED-to-community care transitions,31 or assessed the implementation of a specific program targeting a specific population.32 Furthermore, prior research has identified barriers to successful ED-to-community care transitions across all ages,33 with emphasis placed specifically on follow-up compliance, ED navigators, and telephone calls, and the last being similarly called upon by older adults in this work.

Our findings also support the main components of our conceptual framework (Figure 1), which may be used by ED clinicians to improve ED-to-community care transitions and for future investigators to design effective interventions. The inflow of older adults seeking emergency care is dependent upon clinical factors, sociodemographic factors, and access to care that are predominantly unable to be modified by the time an older adult reaches the ED setting. However, subsequent outcome attainment, such as quality of life, adequate follow-up, or comprehension of red-flag symptoms, may be substantially impacted by components of the ED encounter and community care transition. Potential barriers to incorporating our conceptual framework may exist given the variability in access to multidisciplinary support services, Geriatric ED Accreditation efforts and initiatives, as well as differing levels of screening for health literacy, frailty, cognitive impairment, and social needs that may contribute to success of the care transition.

This research highlights the centrality of the ED discharge process and the emphasis placed on this crucial interaction by older adults. Outlined within a recent environmental scan by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,34 the ED discharge process often is a complex and potentially time-intensive process that involves patient education, support, and coordination of clinical care. Within 90 days of ED discharge, Hastings et al. identified that over half of older adults did not understand discharge information about expected course of illness as well as return precautions, prompting 42.3% of patients to return to the ED.35 Our findings align with these past reports and underscore that suboptimal discharge process discussions may prompt older adults to seek answers from different care providers very shortly after the ED visit. Furthermore, our work among older adults supports prior research conducted in younger populations identifying persistent uncertainty after ED discharge and the receipt of cumbersome and lengthy paperwork that is largely uninterpretable.36–38 While potential difficulties exist in the busy ED environment,39 we believe that ED clinicians should strive to provide brief, actionable, and clearly written discharge instructions to older adults and engage family members and friends when possible for those particularly at-risk for adverse outcomes. We share an example geriatric-friendly ED discharge instruction sheet for an older adult presenting with abdominal pain (Supplemental Text S2).

This work also identifies the physical and psychological limitations experienced by older adults during ED-to-community care transitions and the subsequent reliance on formal and informal family/friend caregivers. Family caregivers often incur substantial burdens during the acute illness and largely lack formal training or education, potentially contributing to the lack of success with prior ED-to-community care transition interventions.40 EDs and treating clinicians have the potential to address these barriers by ensuring streamlined approaches are in place to engage case management services, geriatric-focused professionals, or home health needs during recovery.

We finally suggest that ED clinicians and investigators should keep the older adults’ physical limitations and functional status in mind after an acute illness, as there has been a broader shift towards addressing outcomes that older adults prioritize. ED clinicians may not always be able to anticipate how new injuries or medical conditions can impact the older adult at home, thus there may be a role for in-ED physical or occupational therapy consultation to do more extensive gait and function testing or train towards maintenance of meaningful activities of daily living.41 Recently, the Care Transitions subgroup from the Geriatric Emergency care Applied Research 2.0 Network – Advancing Dementia Care described care transition interventions delivered to older adults with cognitive impairment and their care partners.42 Common ED-to-community care transition interventions included interdisciplinary geriatric assessment, home visits, and telephone follow-ups, with intervention effects exhibiting mixed levels of success. Lessons learned for those with cognitive impairment could apply to the broader older adult population studied within this work. Translating the prior and current work into a potential future line of investigation, the increased use of technology43–45 (e.g. artificial intelligence, two-way text messaging) among older adults may pragmatically address identified barriers in this work by facilitating home review of discharge instructions, enabling access to outpatient follow-up clinical care, providing personalized physical activity guidance to overcome new limitations, and identifying assistive resources in the community for both family caregivers and older adults after an acute illness.

Overall, the complexities of navigating information retention among older adults, time pressures and concurrent demands of treating ED clinicians, and a healthcare system’s willingness to engage in improving this touchpoint may seem daunting. A non-exhaustive compilation of recommendations and illustrative examples that ED clinicians can consider during the ED encounter and discharge process is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Illustrative examples to address prevalent themes and improve ED-to-community care transitions

| Theme | Illustrative Examples |

|---|---|

| 1. ED discharge process was abrupt and lacked explanation |

|

| 2. Barriers to navigating follow-up outpatient clinical care |

|

| 3. New physical limitations and fear of completing prior activities |

|

| 4. Hesitancy to accept the potential need for formal and informal family/friend caregiver assistance |

|

Limitations

Our study findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. This research occurred in four EDs within one health system in New England, and findings may therefore not be generalizable to other regions. The study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is possible that ED patient volumes and clinician volumes led to suboptimal processes of care than would have occurred otherwise. To enhance generalizability, we purposively enrolled participants to ensure a diverse sample by age, race, and chief complaint category. However, we were unable to enroll any participants that identified Spanish as their preferred language despite intentional efforts to translate study consent forms and materials and the presence of bilingual and bicultural study team members. We recognize that inclusion of a greater proportion of non-English-speaking participants may reveal additional barriers and themes surrounding ED-to-community care transitions. Finally, we chose to focus on cognitively intact older adults, as the unique experiences of those with cognitive impairment and their caregivers would likely identify separate barriers, facilitators, and themes during the ED-to-community care transition. Qualitative analyses specifically involving the population of cognitively impaired older adults and their caregivers offers an exciting future research opportunity to improve ED-to-community care transitions.

Conclusions

Our qualitative study provides perspectives regarding critical barriers faced during ED-to-community care transitions among cognitively intact older adults. These findings may inform the development of novel and efficacious ED-to-community care transition interventions targeting older adults.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Text S1. Semi-structured patient interview guide

Supplemental Text S2. Example geriatric-friendly ED discharge instructions for abdominal pain

Key Points:

Key Point:

Older adults experience care transition barriers after an emergency department visit. These include the abruptness of the discharge process, follow-up care navigation, new limitations hindering performance of baseline activities, and ramifications to caregivers impacting an older adult’s willingness to request or accept assistance.

Why Does This Paper Matter?

These findings can help improve geriatric emergency care and inform the development of effective emergency department-to-community care transition patient-centered interventions that have been elusive thus far.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the older adults who participated in the study and shared their experiences.

Disclosure of Funding:

Dr. Gettel is a Pepper Scholar with support from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale School of Medicine (P30AG021342), the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health (R03AG073988), the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Foundation, and the Emergency Medicine Foundation. Dr. Venkatesh is supported by the American Board of Emergency Medicine National Academy of Medicine Anniversary fellowship and previously by the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation (KL2TR000140) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science. Dr. Hwang is supported by the National Institute on Aging (R33AG058926, R61AG069822), by the John A Hartford Foundation, and the West Health Institute. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Sponsor’s Role:

The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

All other authors declare no conflicts of interest that are relevant to this study.

Disclosure of Meeting Presentations and Preprint Status:

This work has been accepted for presentation at the 2022 Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting and the 2022 OAIC Annual Meeting. This work has not been published as a preprint.

References

- 1.National Hospital Ambulatory Medicare Care Survey: 2018 Emergency Department Summary Tables. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2018-ed-web-tables-508.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2022.

- 2.Trends in hospital emergency department visits by age and payor, 2006–2015. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb238-Emergency-Department-Age-Payer-2006-2015.jsp. Accessed February 28, 2022. [PubMed]

- 3.Hastings SN, Schmader KE, Sloane RJ, Weinberger M, Goldberg KC, Oddone EZ. Adverse health outcomes after discharge from the emergency department–incidence and risk factors in a veteran population. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22(11):1527–1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hastings SN, Whitson HE, Purser JL, Sloane RJ, Johnson KS. Emergency department discharge diagnosis and adverse health outcomes in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57(10):1856–1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duseja R, Bardach NS, Lin GA, et al. Revisit rates and associated costs after an emergency department encounter: a multistate analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015;162(11):750–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabayan GZ, Asch SM, Hsia RY, et al. Factors associated with short-term bounce-back admissions after emergency department discharge. Ann Emerg Med 2013;62(2):136–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogan TM, Losman ED, Carpenter CR, et al. Development of geriatric competencies for emergency medicine residents using an expert consensus process. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17(3):316–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Emergency Physicians, American Geriatrics Society, Emergency Nurses Association, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines Task Force. Geriatric emergency department guidelines. Ann Emerg Med 2014;63(5):e7–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emergency Department Transitions of Care – A Quality Measurement Framework. National Quality Forum. Available at: https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2017/08/Emergency_Department_Transitions_of_Care_-_A_Quality_Measurement_Framework_Final_Report.aspx. Accessed February 28, 2022.

- 10.Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation Program. American College of Emergency Physicians. Available at: https://www.acep.org/geda/. Accessed January 22, 2022.

- 11.GEAR Network. Geriatric Emergency care Applied Research. Available at: https://gearnetwork.org/. Accessed January 22, 2022.

- 12.Gettel CJ, Voils CI, Bristol AA, et al. Care transitions and social needs: a Geriatric Emergency care Applied Research (GEAR) Network scoping review and consensus statement. Acad Emerg Med 2021;28(12):1430–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gettel CJ, Falvey JR, Gifford A, et al. Emergency department care transitions for patients with cognitive impairment: a scoping review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2022. Accepted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobsohn GC, Jones CMC, Green RK, et al. Effectiveness of a care transitions intervention for older adults discharged home from the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med 2022;29(1):51–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah MN, Hollander MM, Jones CMC, et al. Improving the ED-to-home transition: the community paramedic-delivered care transitions intervention – preliminary findings. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66(11):2213–2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schumacher JR, Lutz BJ, Hall AG, et al. Impact of an emergency department-to-home transitional care intervention on health service use in Medicare beneficiaries: a mixed methods study. Med Care 2021;59(1):29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biese KJ, Busby-Whitehead J, Cai J, et al. Telephone follow-up for older adults discharged to home from the emergency department: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66(3):452–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowthian JA, McGinnes RA, Brand CA, Barker AL, Cameron PA. Discharging older patients from the emergency department effectively: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2015;44(5):761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gettel CJ, Hayes K, Shield RR, Guthrie KM, Goldberg EM. Care transition decisions after a fall-related emergency department visit: a qualitative experience of patients’ and caregivers’ experiences. Acad Emerg Med 2020;27(9):876–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cadogan MP, Phillips LR, Ziminski CE. A perfect storm: care transitions for vulnerable older adults discharged home from the emergency department without a hospital admission. Gerontologist 2016;56(2):326–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpenter CR, DesPain B, Keeling TN, Shah M, Rothenberger M. The six-item screener and AD8 for the detection of cognitive impairment in geriatric emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57(6):653–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carpenter CR, Bassett ER, Fischer GM, Shirshekan J, Galvin JE, Morris JC. Four sensitive screening tools to detect cognitive dysfunction in geriatric emergency department patients: Brief Alzheimer’s Screen, Short Blessed Test, Ottawa 3DY, and the caregiver-completed AD8. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18(4):374–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Coats MA, Morris JC. Patient’s rating of cognitive ability: using the AD8, a brief informant interview, as a self-rating tool to detect dementia. Arch Neurol 2007;64(5):725–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Sullivan D, Brady N, Manning E, et al. Validation of the 6-item Cognitive Impairment Test and the 4AT test for combined delirium and dementia screening in older emergency department attendees. Age Ageing 2018;47(1):61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacLullich AJM, Shenkin SD, Goodacre S, et al. The 4 ‘A’s test for detecting delirium in acute medical patients: a diagnostic accuracy study. Health Technol Assess 2019;23(40):1–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tieges Z, MacLullich AJM, Anand A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the 4AT for delirium detection in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2021;50(3):733–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide no. 131. Med Teach 2020;42(8):846–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 2006;5(1):80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen AN, Andersen O, Gamst-Jensen H, Kristiansen M. Short communication: opportunities and challenges for early person-centered care for older patients in emergency settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(23):12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolk D, Kruiswijk AF, MacNeil-Vroomen JL, Ridderikhof ML, Buurman BM. Older patients’ perspectives on factors contributing to frequent visits to the emergency department: a qualitative interview study. BMC Public Health 2021;21(1):1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldberg EM, Gettel CJ, Hayes K, Shield RR, Guthrie KM. GAPcare: the Geriatric Acute and Post-acute fall prevention intervention for emergency department patients – a qualitative evaluation. OBM Geriat 2019;3(4):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atzema CL, Maclagan LC. The transition of care between emergency department and primary care: a scoping study. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24(2):201–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Improving the emergency department discharge process: environmental scan report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/systems/hospital/edenvironmentalscan/edenvironmentalscan.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2022.

- 35.Hastings SN, Barrett A, Weinberger M, et al. Older patients’ understanding of emergency department discharge information and its relationship with adverse outcomes. J Patient Saf 2011;7(1):19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buckley BA, McCarthy DM, Forth VE, et al. Patient input into the development and enhancement of ED discharge instructions: a focus group study. J Emerg Nurs 2013;39(6):553–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rising KL, Hudgins A, Reigle M, Hollander JE, Carr BG. “I’m just a patient”: fear and uncertainty as drivers of emergency department use in patients with chronic disease. Ann Emerg Med 2016;68(5):536–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerolamo AM, Jutel A, Kovalsky D, Gentsch A, Doty AMB, Rising KL. Patient-identified needs related to seeking a diagnosis in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2018;72(3):282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benjenk I, DuGoff EH, Jacobsohn GC, et al. Predictors of older adult adherence with emergency department discharge instructions. Acad Emerg Med 2021;28(2):215–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zelis N, Huisman SE, Mauritz AN, Buijs J, de Leeuw PW, Stassen PM. Concerns of older patients and their caregivers in the emergency department. PLoS One 2020;15(7):e0235708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldberg EM, Marks SJ, Resnik LJ, Long S, Mellott H, Merchant RC. Can an emergency department-initiated intervention prevent subsequent falls and health care use in older adults? A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2020;76(6):739–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gettel CJ, Falvey JR, Gifford A, et al. Emergency department care transitions for patients with cognitive impairment: a scoping review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2022;S1525-8610(22)00154-2. Doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.01.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Brien K, Liggett A, Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Sunkara P, Lindquist LA. Voice-controlled intelligent personal assistants to support aging in place. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68(1):176–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Acosta-Franco JA, García-Moreno CAM, García-Vázquez MS, Ramírez-Acosta AÁ. Non-invasive AI model for human functional patterns recognition in IADLs. Alzheimers Dement 2021;17 Suppl 11:e054233. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ho A Are we ready for artificial intelligence health monitoring in elder care? BMC Geriatr 2020;20(1):358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Text S1. Semi-structured patient interview guide

Supplemental Text S2. Example geriatric-friendly ED discharge instructions for abdominal pain