Abstract

Mutation in LRRK2 (Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2) is a common cause of Parkinson’s disease. Aberrant LRRK2 kinase activity is associated with disease pathogenesis, and thus it is an attractive drug target for combating PD. Intense efforts in the past nearly two decades have focused on developing small-molecule inhibitors of the kinase domain of LRRK2, which have identified potent kinase inhibitors. However, most LRRK2 kinase inhibitors have shown adverse effects; therefore, alternative mechanism-based strategies are desperately needed. In this review, we will discuss the new insights gleaned from recent cryo-EM structures of LRRK2 towards understanding the mechanisms of actions of LRRK2 and explore the potential new therapeutic avenues.

Keywords: GTPase, kinase, allosteric regulation, Roc, COR, therapeutics

Historical overview of LRRK2 and its association with Parkinson’s Disease

In 2002, a 13.6cM region at chromosome 12p11.2-q13.1 was linked to inheritable autosomal dominant Parkinson’s disease (PD) and named PARK8 [1]. Two years after, in 2004, two research groups independently identified Leucine-Rich-Repeat Kinase 2 (LRRK2) as the causative gene in PARK8 [2, 3]. To date, several PD-associated mutations in LRRK2 have been identified, and together, they constitute the most common cause of inheritable PD [1–8]. Mutations in LRRK2 account for up to 30% of familial PD cases, and they have also been associated with the risk for sporadic PD [9, 10]. Conversely, a variant of LRRK2, the R1398H polymorphism, has been linked to a reduced risk of PD [11].

The precise function of LRRK2 remains unclear, although it has been found bound to microtubules, localized to the trans-Golgi network and plasma membranes, and may play a role in vesicular trafficking, axonal transport, and ciliation [12–21]. LRRK2 can be classified as belonging to the Roco family (see Glossary) of proteins, which is defined by the occurrence of a Ras-like GTPase domain called Ras of complex proteins (Roc) upstream of a unique domain named C-terminal of Roc (COR) [22, 23]. The Roc domain is a bona fide GTPase that hydrolyzes GTP and undergoes nucleotide-dependent conformational changes reminiscent of the canonical GTPase [24]. The PD-associated mutations in the Roc domain reduce its GTPase activity and impair its conformational dynamics [24–27]. However, the mechanisms by which these occur remain elusive, and the role of the Roc-COR di-domain in the activity of LRRK2 is still unclear.

The most common PD-associated mutation in LRRK2 (G2019S) resides within the activation loop of the kinase domain, and it causes an aberrant increase in kinase activity [28–30]. Interestingly, the PD-associated mutations in the Roc domain also cause overactivation of LRRK2 kinase activity [31, 32], thus suggesting the potential existence of yet-to-be characterized allosteric effects between the two domains. The association of aberrant kinase activity with disease pathogenesis has made LRRK2 an attractive drug target for combating PD. Most of the efforts, to date, have been focused on developing small-molecule inhibitors of LRRK2 kinase activity and, so far, have resulted in several highly potent kinase inhibitors, and one compound has progressed to phase 1b clinical trial [33, 34]. Several preclinical studies showed adverse effects upon inhibition of LRRK2 kinase activity; therefore, alternative strategies are being actively explored (see Text Box for more details) [35]. As such, there is a need for understanding the molecular mechanism of action of LRRK2 for the development of mechanism-based drug discovery strategies. In this review, we will discuss the current understanding of the mechanisms of actions of LRRK2 and explore the potential new therapeutic avenues gleaned from the recent studies (Box 1).

TEXT BOX. New avenues for therapeutic discovery.

LRRK2 remains the most promising drug target for combating Parkinson’s disease (PD), and the predominant therapeutic strategy in the recent 18 years has been on developing small-molecule inhibitors targeting the kinase domain of LRRK2. LRRK2 is an attractive drug target for several practical reasons, including being an enzyme consisting of active sites well suited for binding potential drugs and the preexisting deep experience in kinase drug discovery in the field. Indeed, LRRK2 kinase activity has been effectively inhibited by a broad set of kinase inhibitors that compete for ATP in the ATP-binding pocket as well as LRRK2-specific compounds [33, 34], including two compounds, DNL201 and DNL151, in clinical trials [59]. Although a recent study in nonhuman primates showing that the histopathological changes caused by LRRK2 kinase inhibitors were reversible after drug withdrawal has helped alleviate concerns about the toxicity observed in earlier preclinical studies [60–63], they have prompted interest in potential alternative strategies, including targeting the Roc domain or specific domain-domain interfaces [35].

To this end, three compounds targeting the GTP affinity of Roc showed rescuing effects against LRRK2-associated impairment and toxicity in neuronal cultures and mouse models [64–66]. Moreover, impairing GTP-binding by introducing a point mutation T1348N into the PD-associated mutant G2019S resulted in the attenuation of dopaminergic neuronal loss in a rat model [54]. While these studies suggest that targeting the GTP-binding site of Roc may have therapeutic effects, there are several drawbacks to this strategy; including the potential off-target side effects as the GTP-binding pockets of different small G-proteins are remarkably similar, and thus specificity would be difficult to achieve, and their superior affinity for Roc needed in order to compete with the high cellular concentration of GTP (~ 0.5 mM) [67].

A new front of targeting LRRK2 focuses on allosteric modulators of GTP-binding by modulating the conformational states of Roc, which could potentially circumvent the formidable challenges mentioned above. A recent study showed that disrupting LRRK2 dimerization by poisoning the interface between Roc and COR with a stabilized helical peptide resulted in decreased kinase activity [68]. Similarly, the binding of nanobodies to LRRK2, presumably locking it in certain conformations, also attenuated its kinase activity [69]. Understanding where these peptides and nanobodies bind and how they alter the conformation of LRRK2 would facilitate their optimization. The recent availability of structural data has provided frameworks for structure-based design of small-molecule inhibitors and provided insights that opened new avenues for structured-based design of conformational-locking antibodies and other biologics targeting LRRK2.

The structure of LRRK2

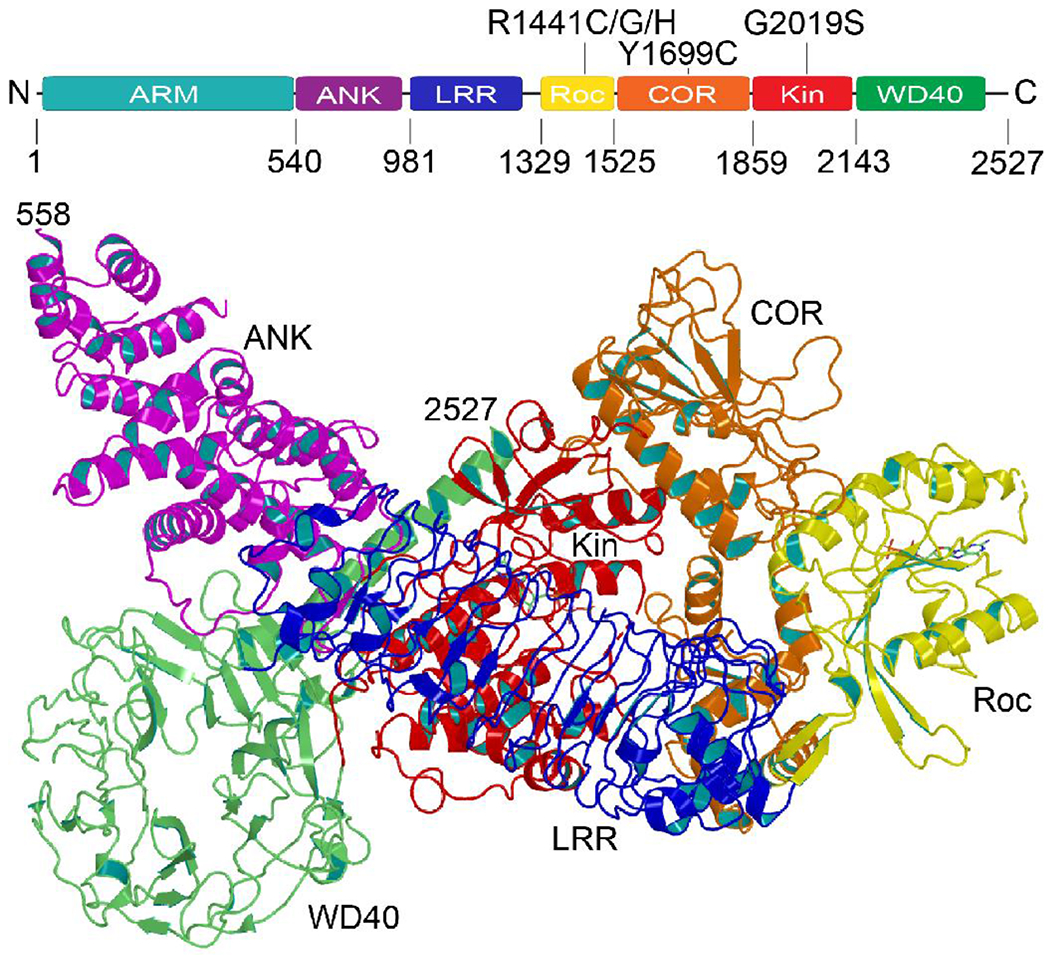

The primary structure of LRRK2 consists of 2,527 amino acids (Figure 1). Bioinformatic analysis of the amino acid sequence revealed sequence similarity to seven different well-studied protein folds, including, from N-terminus; 1) an Armadillo repeat domain (ARM), which is composed of multiple copies of pairs of U-shaped α-helices connected by a hairpin-turns forming an alpha-solenoid structure, 2) an Ankyrin repeat domain (ANK), which is also a solenoid structure formed with linear arrays of tandem copies of a motif composing of a α-helix-loop-α-helix repeating units, 3) a Leucine-rich repeat domain (LRR), which is composed of β-strand-turn-α-helix repeating units forming a horseshoe-shaped solenoid domain, 4) a GTPase domain called Ras of complex proteins (Roc) that consists of six β-strands and five α-helixes together with the interconnecting loops form the G protein signature structural features, 5) a unique domain called C-terminal of Roc (COR), which consists of two lobes, one composing mainly of α-helixes and loops and the other composing of β-strand-α-helix-β-strand motif, 6) a kinase domain (Kin) consisting of five β-strains and one α-helix in the N-terminal lobe and the C-terminal lobe consists of six α-helices and two long loops, together representing all the conserved features of a kinase domain, and lastly 7) a WD40 domain (WD40) composing of seven blades each consisting of four anti-parallel β-strands and together forming a solenoid circular β-propeller structure. The remaining 27 amino acids form an α-helix extending from the WD40 domain (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Structure of LRRK2.

a) The primary structure of LRRK2 consists of 2527 amino acids folded into seven domains, including Armadillo (ARM), Ankyrin (ANK), Ras of complex proteins (Roc), C-terminal of Roc (COR), kinase (Kinase), and WD40. b) Ribbon presentation of LRRK2 showing the Roc domain (yellow) cradled in the center of the COR domain (orange). The ANK domain (purple) and LRR domain (blue) wrap around the Kin domain (red). The WD40 domain (green) tethers the kinase domain via a long C-terminal helix. This conformation is believed to be a kinase-inactive state. (PDB ID: 7LI4)

Besides the atypically long primary structure and the occurrence of many domains, the three uncommon structural features that make LRRK2 unique are the number of solenoid repeat domains (ARM, ANK, LRR, and WD40) it contains, the co-existence of two different enzymes (GTPase and kinase) in the same polypeptide chain, and the defining Roc-COR tandem domain, which forms a tight complex. The ANK and LRR domain, which are in the N-terminal ‘arm’ of Roc, is wrapped around the kinase domain, which is the C-terminal ‘arm’ of COR [13, 36] (Figure 1). The WD40 domain is tethered to the kinase domain by the C-terminal helix [13, 36] (Figure 1). The ARM domain is less resolved and extended away from the protein core [36].

As discussed below, LRRK2 appears to adopt many different conformations in vitro, and it likely undergoes significant conformational changes as it carries out its function. It is unclear where the conformations captured by cryo-EM lie along the range of LRRK2 activity, or if they are on the path. Therefore, the role of the domains and their arrangement with respect to one another in the cycle of LRRK2 activity is not yet clear. However, a recent study showed that the Roc-COR tandem domain dynamically moved relative to the kinase domain and, in doing so, altered the interactions and conformation of the kinase domain [37], thus presenting a plausible model in which the motions occurring in Roc-COR regulates the kinase activity of LRRK2. Indeed, a recent cryo-EM structure of an LRRK2-Rab29 complex revealed an ‘activated’ conformation in which the COR domain of LRRK2 interacts directly with the activation loop of its kinase domain, thus supporting the notion of Roc-COR playing a role in regulating LRRK2 kinase activity [38]. Roc-COR has also been speculated to be involved in the dimerization of LRRK2, which has also been observed in the bacterial Roco protein [39, 40]. Indeed, prior to the availability of LRRK2 samples amenable for biochemical and structural characterization, studies using the bacterial model system had provided insights into the mechanisms of the Roco family of proteins [39–44]. However, this review mainly focuses on LRRK2. To date, several quaternary structures of LRRK2, including monomer, dimer, trimer, tetramer, and polymer on microtubules, have been observed [12, 13, 36, 38]; however, the significance of each of these conformational states to the function of LRRK2 remains unclear.

The kinase activity of LRRK2

The kinase activity of LRRK2 has been demonstrated by several studies, including autophosphorylation, phosphorylation of generic kinase substrates and specific peptide substrates, and phosphorylation of a sub-group of Rab GTPases associated with vesicular trafficking [17, 21, 29, 45–48]. These G-proteins are currently the strongest candidates for the biological substrates of LRRK2. LRRK2 kinase activity has been shown to regulate lysosomal glucocerebrosidase via the phosphorylation of Rab10 in cells derived from a PD patient [49], thus providing support that Rab10 is a substrate of LRRK2; however, it remains unclear whether other yet unidentified substrates exist.

To date, it appears that each of the four most-characterized PD-associated mutation sites in LRRK2 leads to an increase in kinase activity. For example, several studies have observed that the most common mutation in LRRK2, G2019S, exhibited higher kinase activities than the wild-type [29, 46]. Similarly, the adjacent I2020T mutation has also been shown to have higher kinase activity against myelin basic protein and autophosphorylation [29, 50]. However, the I2020T LRRK2 mutant has been observed to exhibit lower kinase activity against moesin in vitro [46], thus potentially reflecting the complexity of the mechanisms regulating LRRK2 activity. Adding to this potential complexity, the PD-associated mutations in the Roc and COR domains at position R1441 and Y1699, respectively, have also been observed to exhibit higher kinase activity [31], thus suggesting a potential allosteric regulatory mechanism governing LRRK2 kinase activity. Taken together, the data show that the aberrant increase in the kinase of LRRK2 is associated with the pathogenesis of PD and that this could occur by both mutations within the kinase domain or those in the other domains.

The mechanism by which LRRK2 kinase activity is regulated and how it is affected by the PD-associated mutations remains unclear. However, G2019S resides in the so-called DFG motif (DYG in LRRK2) in the activation loop of the kinase domain, which suggests that the regulatory mechanism of LRRK2 kinase activity is, at least in part, similar to that of other well-characterized kinases [51], where the aspartic acid of the DFG motif is a key catalytic residue, and thus its positioning is critical for catalysis. Additionally, the phenylalanine of DFG plays a role in the assembly of the so-called Regulatory Spine (R-spine) essential for the activation of conical kinases. Therefore, the G2019S mutation, changing the DYG motif to DYS, is expected to alter interactions and impair the regulatory mechanism described above. However, how the PD-associated mutations outside of the kinase domain of LRRK2 regulate its kinase activity remains a mystery. Recently, molecular dynamic and hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass-spectrometry studies showed dynamic interactions between the kinase domain with the Roc-COR di-domain, which suggests that these interactions might constitute an allosteric regulatory mechanism of LRRK2 kinase activity [37]. Indeed, a recent cryo-EM structure of an activated LRRK2 showed direction interactions between the kinase and COR domains leading to the assembly of the R-spine and ordering of the activation loop. Understanding the mechanism by which this allostery occurs is undoubtedly essential for understanding LRRK2 activity regulation and potentially unlocking new avenues for therapeutic discovery.

The role of the G-domain in regulating the kinase activity of LRRK2

Several lines of evidence support that the Roc domain of LRRK2 may be the allosteric regulator of its kinase activity. For example, the capacity of LRRK2 to bind GTP and its ability to hydrolyze GTP is required for proper kinase activity [52, 53]. The artificial mutations within the Roc domain (K1347A, T1348N) that abrogate GTP binding displayed weakened or no kinase activity in vitro or in cells [53]. Most of the PD-associated mutations in the Roc-COR tandem domain (R1441C, R1441H, Y1699C) that enhance GTP affinity and reduce GTP hydrolysis showed increased LRRK2 kinase activity [25]. More recently, it has been shown that the G2019S mutation in LRRK2 induced neurodegeneration in a rodent model via a mechanism that is dependent on both kinase and GTPase activity [54].

Moreover, the dopaminergic neuronal loss induced by the G2019S mutation in the striatum of a rat model was significantly attenuated when the GTP-locked mutants (T1348N, R1398L) were also introduced [54]. As such, it appears that both conformation and GTPase activity of Roc modulate the kinase activity of LRRK2. How the Roc domain regulates the activity of its kinase activity of LRRK2 remains unclear; however, the literature suggests two plausible mechanisms.

LRRK2 potentially exists in equilibrium between membrane-bound dimeric and cytosolic monomeric conformations [55], where the dimeric form has been shown to have higher kinase activity than that of the monomeric conformation [56], thus suggesting that the kinase activity might be activated upon dimerization. A recent cryo-electron tomography study of LRRK2 bound to microtubules in situ showed the Roc-COR di-domain at the homo-dimeric interface [12]. Although it remains unclear whether or not this dimeric interaction occurs in un-bounded soluble LRRK2, it has been observed in the Chlorobaculum tepidum homolog Roco protein, where homodimerization occurred via a direct interaction between the Roc and COR domains in a guanine nucleotide-dependent manner – a dynamic equilibrium between GDP-bound dimeric and GTP-bound monomeric conformations [39]. This evidence suggests a plausible mechanism whereby nucleotide binding to the Roc domain regulates dimerization of LRRK2 and thereby its kinase activity.

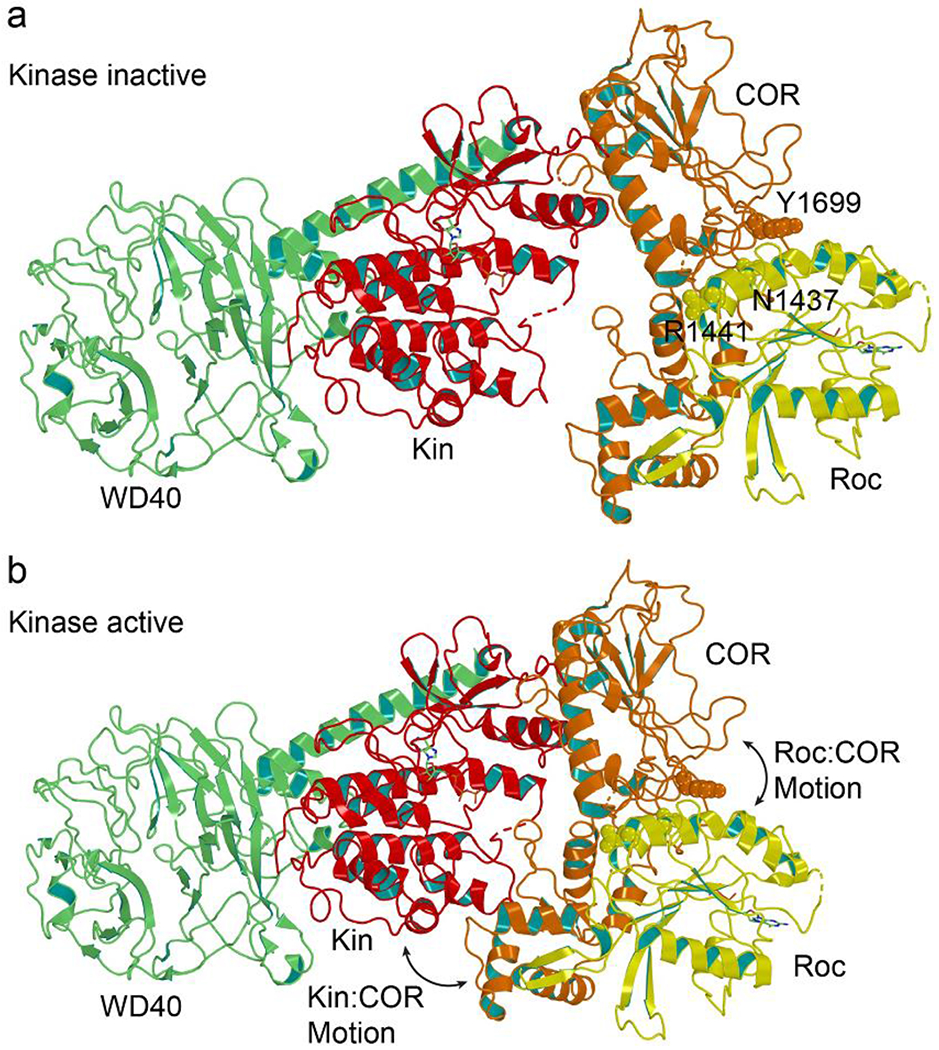

Alternatively, or additionally, the Roc domain may intramolecularly interact with the kinase domain and, in doing so, modulates its kinase activity. Evidence for this potential mechanism came from a recent hydrogen-deuterium exchange study showing the Roc-COR di-domain undergoes a dynamic motion relative to the kinase domain [37]. In the ‘compact’ conformation, Roc-COR interacts directly with the active-site structures of the kinase domain known in canonical kinases to govern the phosphotransfer reaction, including the activation loop and the αC helix [37] (Figure 2). This model is supported by a very recent cryo-EM structure of an LRRK2-Rab29 complex that showed an active conformation of the kinase domain interacting directly with the COR domain [38]. What drives the potential reciprocating motion between the ‘compact’ and ‘extended’ conformations remains unclear; however, clues can be gleaned from the wealth of knowledge on G-protein mediate conformational changes in other systems, the detailed structural and mechanistic studies of the Roc domain, and the recent cryo-EM structures of LRRK2.

Figure 2. Potential allosteric regulation of kinase activity.

a) Ribbon representation showing the Roc-COR tandem domain (yellow-orange) is mostly separated from the Kin domain in a kinase-inactive conformation (PDB ID: 7LI4). b) A theoretic model of Roc allosterically modulates the kinase of LRRK2 constructed by manually rotating Roc of PDB ID 7LI4 closer to its kinase domain based on recent structural data [38]. The Roc-COR tandem domain has rotated closer to and interacts directly with the Kin domain in a kinase-active conformation. This movement might be regulated by a rotation of Roc relative to COR by about 15 degrees [38].

G-domain activity and conformational changes

G proteins are molecular switches that toggle between the “on” and “off” states upon binding to GTP or GDP, respectively [57]. The conformational changes that occur upon binding GTP result in the assembly of protein surfaces for binding to effectors to propagate signaling or drive mechanical motions and protein assemblies. Although G proteins have intrinsic GTP hydrolysis activity, they can be regulated by several types of proteins. GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) facilitate GTP hydrolysis leading to the switching from “on” to “off” conformation of the G protein. In contrast, guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) facilitate the binding of GTP to the G proteins by increasing the rate of exchange of GDP for GTP and, thereby, switching to the “on” conformation. The G-domain of G proteins is about 20-kD, which consists of the structural features required to carry out the basic function of nucleotide binding, hydrolysis, and switching.

The Roc domain of LRRK2 is a 22-kD G-domain that is independently folded and active as a GTPase [24]. Although Roc shares very low amino acid sequence conservation with other G proteins, it possesses all the signature structural features of a typical G protein, including the P-loop, Switch I, Switch II, and the G-binding motifs. However, Roc is unique in that, by definition, it always coexists with the COR domain, suggesting that the way in which Roc functions might also be unique relative to that of the typical G proteins. A notable difference in the amino acid sequence of Roc compared to the typical G protein is an arginine residue at position 1398 of Roc, while other G proteins contain a glutamine residue at the equivalent position. This glutamine residue in the typical G proteins catalyzes GTP hydrolysis by activating a nearby water molecule for nucleophilic attack at the gamma-phosphate of GTP. How an arginine residue at the equivalent position in Roc affects its activity is a mystery and may indicate a unique mechanism of action. Another data point suggesting that the mechanism of Roc might be distinct from that of the typical GTPases is that, although the intrinsic GTPase activity of the isolated Roc domain is similar to that of Ras (kcat = 0.020 min−1 vs. 0.028 min−1, respectively), its affinity for GTP is significantly lower (Kd = 7.85 μM vs. 79.1 pM, respectively) [13, 24, 58].

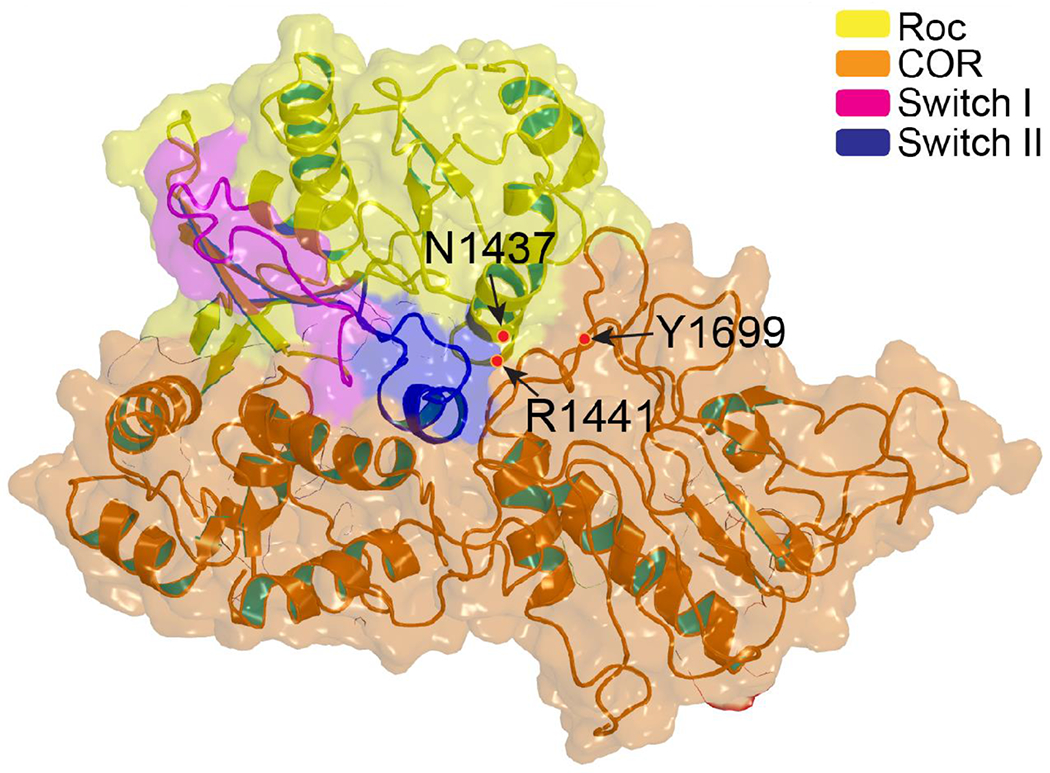

How these unique features of Roc integrate with the COR domain to exert its switching function on the activity of LRRK2 remains elusive. However, in an isolated construct called Rocext consisting of residues 1329-1525, Roc exists in both monomeric and dimeric conformations [24–26]. Although this homo-dimeric conformation of Roc has not been observed in the structures of LRRK2 determined so far and is thus unlikely to occur in the context of the full-length protein, it does occur in Rocext in a nucleotide-dependent manner. Specifically, Wu et al. elegantly showed that dimeric Rocext broke up into monomers upon binding GTP and dynamically converted back to dimers in the GDP-bound form, all occurring in the same protein sample [25]. This showed that the formation of Rocext dimers is a consequence of the nucleotide-dependent conformational changes of the signature structural features, such as Switch I and Switch II, as would occur during the switching actions of canonical G proteins. Using this dimer-monomer equilibrium of Rocext as a measure of its nucleotide-dependent conformational changes, we showed that all the PD-associated mutations in the Roc domain impaired this conformational dynamic and trapped it in the monomeric state, even in the absence of GTP [25–27]. This implies that the PD-associated mutations in Roc each traps it in a persistently activated or “on” state, which begs the question, what does this state do to the full-length LRRK2? Applying these observations to the context of the full-length LRRK2, where the switch regions and the PD-associated mutations in Roc reside at the interface with COR (Figure 3), it seems plausible that the nucleotides and PD-mutations potentially affect the interaction between Roc and COR in a similar fashion as they affected the Roc-Roc homodimer described above. For example, the nucleotide-dependent conformational changes in Roc could potentially alter its interactions with COR, and that the PD-associated mutations in Roc may impair this process and trap it in a persistently ‘activated’ state.

Figure 3. The Roc-COR interface.

Semi-transparent surface rendering of the Roc-COR domain of LRRK2 (yellow-orange) showing the Switch II (blue) is buried deep in the center of the interface cleft of COR. Both PD-mutations in Roc and in COR reside at the interface between the two domains. (PDB ID: 7LI4)

Potential mechanism of Roc conformational changes regulating kinase activity

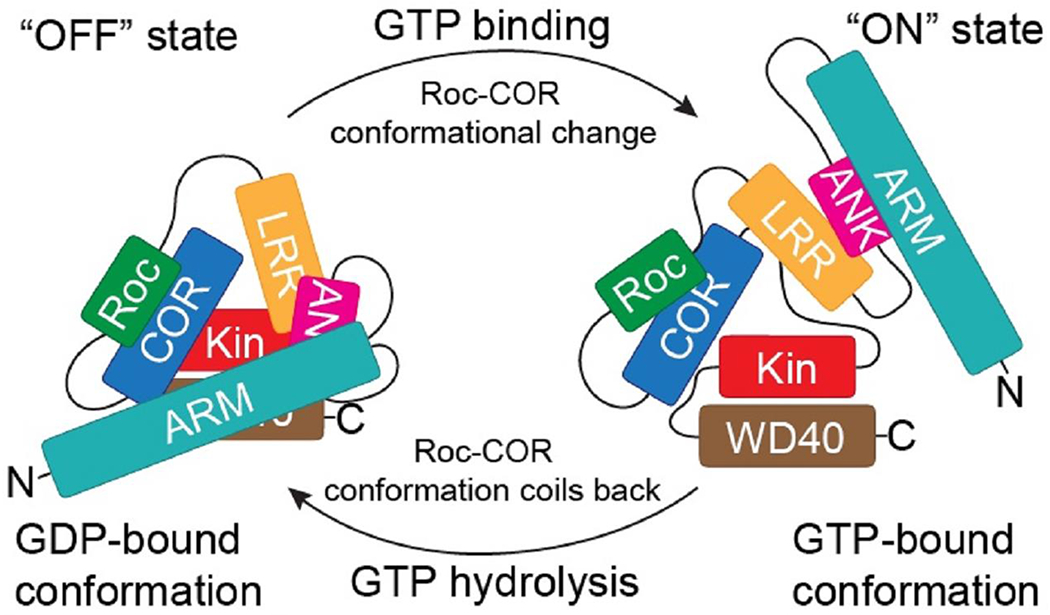

The precise mechanism of nucleotide-mediated conformational changes in Roc and how they are conveyed to the other domains in LRRK2 is entirely unknown. However, the fact that Roc always exists in tandem with the COR domain suggests that the two domains might function as a unit. This notion is supported by the recent cryo-EM structures of LRRK2, revealing that Roc is cradled deeply in the middle of the COR domain [13, 36] (Figure 3). As described above, in the center of this Roc-COR interface lies the Switch II of Roc, which is known to undergo conformational changes upon binding guanine nucleotides and, as its name implies, is critical for mediating the switching mechanism of G proteins [57]. Moreover, the PD-associated mutations that impair the conformational dynamics of Roc described above reside at the interface between Roc and COR (Figure 3). Given the biochemical and structural data described above, it seems plausible that GDP and GTP binding pushes and pulls Switch II relative to COR creating relative motion between the domains N-terminus of Roc and C-terminus of COR. Since the N- and C-terminus half of LRRK2 are covalently linked to the N-terminus of Roc and C-terminus of COR, respectively, we imagine that a motion in Roc with respect to COR would likely result in the drastic global conformational change in LRRK2 (Figure 4). This model would explain that the PD-associated mutations in Roc impair the potential Roc-COR-mediated conformational changes in LRRK2, leading to the dysregulation of its kinase activity. Indeed, during our revision of this manuscript, a cryo-EM structure reported in BioRxiv showed that the interactions between Roc and COR in the kinase-active state are different than those in the kinase-inactive state, where the helix-C of Roc is tilled 15° relatively between the two states [38].

Figure 4.

A theoretical model of GDP-GTP-dependent conformational change in Roc leading to a global structural change in LRRK2. The nucleotide-dependent conformational changes in Roc-COR, in addition to modulating the kinase activity of LRRK2 by the direct interaction between COR and kinase domain as described in [38] and depicted in Figure 2 above, potentially leads to a broad global conformational change and modulate the other activities of LRRK2, such as substrate binding and subcellular localization.

Concluding remarks

It is an exciting time for PD research and LRRK2, particularly with the recent structural and biochemical data providing insights into its mechanism of action. LRRK2 is fundamentally an interesting enzyme in that it consists of two distinct enzymes in the same polypeptide chain. Defining how the activity of one potentially modulates the activity of the other is essential for understanding LRRK2. Understanding the mechanism of LRRK2 would undoubtedly open new avenues for drug discovery to combat PD. The currently available data in the literature suggest that the Roc-COR di-domain is the nucleotide-dependent allosteric regulator of LRRK2 activity. As such, it seems that Roc-COR is an attractive target for allosterically modulating the kinase activity of LRRK2. This strategy may circumvent the adverse effects observed in the currently known inhibitors of the kinase domain of LRRK2.

To do so, a better understanding of the mechanism of conformational changes that occur within Roc-COR and how that is reciprocated to the other domains of LRRK2. Several key remaining questions to unraveling the mechanism of LRRK2 include a) what is the active conformation of LRRK2, b) what is the role of each domain in the functioning of LRRK2, c) what is the mechanism by which LRRK2 switches from an inactive to an active conformation? Answering these questions will likely depend on the ability to trap LRRK2 in its various conformations for structural and biochemical characterizations. Studies are underway in several groups to trap LRRK2 in specific conformations via protein engineering, binding of small molecules, and trapping with antibodies and aptamers in the quest to find the answers to these questions.

OUTSTANDING QUESTIONS:

What is the active conformation of LRRK2?

What is the role of each domain in the functioning of LRRK2?

What is the mechanism by which LRRK2 switches from an inactive to an active conformation?

HIGHLIGHTS:

Mutation in LRRK2 is a common cause of Parkinson’s disease.

Over the past nearly two decades, detailed structural and biochemical studies of the Roc domain of LRRK2 revealed a dynamic nucleotide-dependent conformational equilibrium; however, how this reciprocates to other domains remains unclear.

The recently determined cryo-EM partial structures of LRRK2 reveal how the domains might interact with one another and enable examining Roc activity in the context of the full-length protein.

The available data suggest that the Roc-COR tandem domain may allosterically regulate the kinase activity of LRRK2.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

QQH acknowledges funding from the NIH (R01GM111639, R01GM115844) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. JL acknowledges the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC No. 81971196). The structural coordinate file containing the ARM domain used to make the structural figure was graciously provided by Ji Sun.

GLOSSARY:

- Activation loop

A flexible loop close to the active site. In most kinases, activation occurs by the phosphorylation of specific residues in the activation loop.

- Allosteric modulators

Compounds or proteins that modulate the activity of an enzyme or a receptor by interacting with areas outside of their orthosteric sites.

- GTPase activating protein (GAP)

A negative regulator of GTPase protein that promote the conversion of the GTP-bound form to the GDP-bound form.

- Guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF)

A protein that facilitates the release of GDP from the small G-protein.

- Nanobodies

Small single-domain antibodies derived from heavy chain only antibodies present in camelids and cartilaginous fishes.

- R-spine

The regulatory spine is a collection of residues that dynamically assemble as a part of regulation of kinase activity. An assembled R-spine is a hallmark of an active kinase.

- Roco Family

A family of proteins characterized by containing Roc (a Ras-like GTPase domain) and COR (C-terminal of Roc) domains in tandem.

- Small-molecule inhibitors

Bioactive small molecules with a molecular weight of less than 900 Daltons.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Funayama M, Hasegawa K, Kowa H, Saito M, Tsuji S, Obata F: A new locus for Parkinson’s disease (PARK8) maps to chromosome 12p11.2-q13.1. Ann Neurol 2002, 51(3):296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimprich A, Biskup S, Leitner P, Lichtner P, Farrer M, Lincoln S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Uitti RJ, Calne DB et al. : Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron 2004, 44(4):601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paisan-Ruiz C, Jain S, Evans EW, Gilks WP, Simon J, van der Brug M, Lopez de Munain A, Aparicio S, Gil AM, Khan N et al. : Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 2004, 44(4):595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross OA, Wu YR, Lee MC, Funayama M, Chen ML, Soto AI, Mata IF, Lee-Chen GJ, Chen CM, Tang M et al. : Analysis of Lrrk2 R1628P as a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 2008, 64(1):88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos-Reboucas CB, Abdalla CB, Martins PA, Baldi FJ, Santos JM, Motta LB, de Borges MB, Souza DR, de Souza Pinhel MA, Laks J et al. : LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation is not common among Alzheimer’s disease patients in Brazil. Dis Markers 2009, 27(1):13–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Fonzo A, Wu-Chou YH, Lu CS, van Doeselaar M, Simons EJ, Rohe CF, Chang HC, Chen RS, Weng YH, Vanacore N et al. : A common missense variant in the LRRK2 gene, Gly2385Arg, associated with Parkinson’s disease risk in Taiwan. Neurogenetics 2006, 7(3):133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santpere G, Ferrer I: LRRK2 and neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol 2009, 117(3):227–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kluss JH, Mamais A, Cookson MR: LRRK2 links genetic and sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Biochem Soc Trans 2019, 47(2):651–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan EK, Shen H, Tan LC, Farrer M, Yew K, Chua E, Jamora RD, Puvan K, Puong KY, Zhao Y et al. : The G2019S LRRK2 mutation is uncommon in an Asian cohort of Parkinson’s disease patients. Neurosci Lett 2005, 384(3):327–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan DK, Ng PW, Mok V, Yeung J, Fang ZM, Clarke R, Leung E, Wong L: LRRK2 Gly2385Arg mutation and clinical features in a Chinese population with early-onset Parkinson’s disease compared to late-onset patients. J Neural Transm 2008, 115(9):1275–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L, Zhang S, Liu Y, Hong H, Wang H, Zheng Y, Zhou H, Chen J, Xian W, He Y et al. : LRRK2 R1398H polymorphism is associated with decreased risk of Parkinson’s disease in a Han Chinese population. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2011, 17(4):291–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe R, Buschauer R, Bohning J, Audagnotto M, Lasker K, Lu TW, Boassa D, Taylor S, Villa E: The In Situ Structure of Parkinson’s Disease-Linked LRRK2. Cell 2020, 182(6):1508–1518 e1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deniston CK, Salogiannis J, Mathea S, Snead DM, Lahiri I, Matyszewski M, Donosa O, Watanabe R, Bohning J, Shiau AK et al. : Structure of LRRK2 in Parkinson’s disease and model for microtubule interaction. Nature 2020, 588(7837):344–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biskup S, Moore DJ, Celsi F, Higashi S, West AB, Andrabi SA, Kurkinen K, Yu SW, Savitt JM, Waldvogel HJ et al. : Localization of LRRK2 to membranous and vesicular structures in mammalian brain. Ann Neurol 2006, 60(5):557–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng XY, Yang M, Tan JQ, Pan Q, Long ZG, Dai HP, Xia K, Xia JH, Zhang ZH: Screening of LRRK2 interactants by yeast 2-hybrid analysis. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2008, 33(10):883–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beilina A, Rudenko IN, Kaganovich A, Civiero L, Chau H, Kalia SK, Kalia LV, Lobbestael E, Chia R, Ndukwe K et al. : Unbiased screen for interactors of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 supports a common pathway for sporadic and familial Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111(7):2626–2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beilina A, Bonet-Ponce L, Kumaran R, Kordich JJ, Ishida M, Mamais A, Kaganovich A, Saez-Atienzar S, Gershlick DC, Roosen DA et al. : The Parkinson’s Disease Protein LRRK2 Interacts with the GARP Complex to Promote Retrograde Transport to the trans-Golgi Network. Cell Rep 2020, 31(5):107614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan SS, Sobu Y, Dhekne HS, Tonelli F, Berndsen K, Alessi DR, Pfeffer SR: Pathogenic LRRK2 control of primary cilia and Hedgehog signaling in neurons and astrocytes of mouse brain. Elife 2021, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhekne HS, Yanatori I, Vides EG, Sobu Y, Diez F, Tonelli F, Pfeffer SR: LRRK2-phosphorylated Rab10 sequesters Myosin Va with RILPL2 during ciliogenesis blockade. Life Sci Alliance 2021, 4(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobu Y, Wawro PS, Dhekne HS, Yeshaw WM, Pfeffer SR: Pathogenic LRRK2 regulates ciliation probability upstream of tau tubulin kinase 2 via Rab10 and RILPL1 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steger M, Tonelli F, Ito G, Davies P, Trost M, Vetter M, Wachter S, Lorentzen E, Duddy G, Wilson S et al. : Phosphoproteomics reveals that Parkinson’s disease kinase LRRK2 regulates a subset of Rab GTPases. Elife 2016, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosgraaf L, Van Haastert PJ: Roc, a Ras/GTPase domain in complex proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003, 1643(1-3):5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Egmond WN, Kortholt A, Plak K, Bosgraaf L, Bosgraaf S, Keizer-Gunnink I, van Haastert PJ: Intramolecular activation mechanism of the Dictyostelium LRRK2 homolog Roco protein GbpC. J Biol Chem 2008, 283(44):30412–30420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao J, Wu CX, Burlak C, Zhang S, Sahm H, Wang M, Zhang ZY, Vogel KW, Federici M, Riddle SM et al. : Parkinson disease-associated mutation R1441H in LRRK2 prolongs the “active state” of its GTPase domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111(11):4055–4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu CX, Liao J, Park Y, Reed X, Engel VA, Hoang NC, Takagi Y, Johnson SM, Wang M, Federici M et al. : Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in the GTPase domain of LRRK2 impair its nucleotide-dependent conformational dynamics. J Biol Chem 2019, 294(15):5907–5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang X, Wu C, Park Y, Long X, Hoang QQ, Liao J: The Parkinson’s disease-associated mutation N1437H impairs conformational dynamics in the G domain of LRRK2. Faseb J 2019, 33(4):4814–4823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu C, Liao J, Park Y, Hoang NC, Engel VA, Wan L, Oh M, Sanishvili R, Takagi Y, Johnson SM et al. : A revised 1.6 Å structure of the GTPase domain of the Parkinson’s disease-associated protein LRRK2 provides insights into mechanisms. bioRxiv 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nichols WC, Pankratz N, Hernandez D, Paisan-Ruiz C, Jain S, Halter CA, Michaels VE, Reed T, Rudolph A, Shults CW et al. : Genetic screening for a single common LRRK2 mutation in familial Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2005, 365(9457):410–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West AB, Moore DJ, Biskup S, Bugayenko A, Smith WW, Ross CA, Dawson VL, Dawson TM: Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102(46):16842–16847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greggio E, Jain S, Kingsbury A, Bandopadhyay R, Lewis P, Kaganovich A, van der Brug MP, Beilina A, Blackinton J, Thomas KJ et al. : Kinase activity is required for the toxic effects of mutant LRRK2/dardarin. Neurobiology of Disease 2006, 23(2):329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West AB, Moore DJ, Choi C, Andrabi SA, Li X, Dikeman D, Biskup S, Zhang Z, Lim KL, Dawson VL et al. : Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in LRRK2 link enhanced GTP-binding and kinase activities to neuronal toxicity. Hum Mol Genet 2007, 16(2):223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo L, Gandhi PN, Wang W, Petersen RB, Wilson-Delfosse AL, Chen SG: The Parkinson’s disease-associated protein, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), is an authentic GTPase that stimulates kinase activity. Exp Cell Res 2007, 313(16):3658–3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weygant N, Qu D, Berry WL, May R, Chandrakesan P, Owen DB, Sureban SM, Ali N, Janknecht R, Houchen CW: Small molecule kinase inhibitor LRRK2-IN-1 demonstrates potent activity against colorectal and pancreatic cancer through inhibition of doublecortin-like kinase 1. Mol Cancer 2014, 13:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao Y, Dzamko N: Recent Developments in LRRK2-Targeted Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease. Drugs 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudenko IN, Chia R, Cookson MR: Is inhibition of kinase activity the only therapeutic strategy for LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s disease? BMC Med 2012, 10:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Myasnikov A, Zhu H, Hixson P, Xie B, Yu K, Pitre A, Peng J, Sun J: Structural analysis of the full-length human LRRK2. Cell 2021, 184(13):3519–3527 e3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weng JH, Aoto PC, Lorenz R, Wu J, Schmidt SH, Manschwetus JT, Kaila-Sharma P, Silletti S, Mathea S, Chatterjee D et al. : LRRK2 dynamics analysis identifies allosteric control of the crosstalk between its catalytic domains. PLoS Biol 2022, 20(2):e3001427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanwen Zhu FT, Allessi Dario R., Sun Ji: Structure basis of human LRRK2 membrane recruitment and activation. bioRxiv 2022, doi: 10.1101/2022.04.26.489605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deyaert E, Wauters L, Guaitoli G, Konijnenberg A, Leemans M, Terheyden S, Petrovic A, Gallardo R, Nederveen-Schippers LM, Athanasopoulos PS et al. : A homologue of the Parkinson’s disease-associated protein LRRK2 undergoes a monomer-dimer transition during GTP turnover. Nat Commun 2017, 8(1):1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gotthardt K, Weyand M, Kortholt A, Van Haastert PJ, Wittinghofer A: Structure of the Roc-COR domain tandem of C. tepidum, a prokaryotic homologue of the human LRRK2 Parkinson kinase. EMBO J 2008, 27(16):2239–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deyaert E, Leemans M, Singh RK, Gallardo R, Steyaert J, Kortholt A, Lauer J, Versees W: Structure and nucleotide-induced conformational dynamics of the Chlorobium tepidum Roco protein. Biochem J 2019, 476(1):51–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leemans M, Galicia C, Deyaert E, Daems E, Krause L, Paesmans J, Pardon E, Steyaert J, Kortholt A, Sobott F et al. : Allosteric modulation of the GTPase activity of a bacterial LRRK2 homolog by conformation-specific Nanobodies. Biochem J 2020, 477(7):1203–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terheyden S, Ho FY, Gilsbach BK, Wittinghofer A, Kortholt A: Revisiting the Roco G-protein cycle. Biochem J 2015, 465(1):139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klein CL, Rovelli G, Springer W, Schall C, Gasser T, Kahle PJ: Homo- and heterodimerization of ROCO kinases: LRRK2 kinase inhibition by the LRRK2 ROCO fragment. J Neurochem 2009, 111(3):703–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheng Z, Zhang S, Bustos D, Kleinheinz T, Le Pichon CE, Dominguez SL, Solanoy HO, Drummond J, Zhang X, Ding X et al. : Ser1292 autophosphorylation is an indicator of LRRK2 kinase activity and contributes to the cellular effects of PD mutations. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4(164):164ra161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaleel M, Nichols RJ, Deak M, Campbell DG, Gillardon F, Knebel A, Alessi DR: LRRK2 phosphorylates moesin at threonine-558: characterization of how Parkinson’s disease mutants affect kinase activity. Biochem J 2007, 405(2):307–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee BD, Shin JH, VanKampen J, Petrucelli L, West AB, Ko HS, Lee YI, Maguire-Zeiss KA, Bowers WJ, Federoff HJ et al. : Inhibitors of leucine-rich repeat kinase-2 protect against models of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Med 2010, 16(9):998–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shin N, Jeong H, Kwon J, Heo HY, Kwon JJ, Yun HJ, Kim CH, Han BS, Tong Y, Shen J et al. : LRRK2 regulates synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Exp Cell Res 2008, 314(10):2055–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ysselstein D, Nguyen M, Young TJ, Severino A, Schwake M, Merchant K, Krainc D: LRRK2 kinase activity regulates lysosomal glucocerebrosidase in neurons derived from Parkinson’s disease patients. Nat Commun 2019, 10(1):5570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gloeckner CJ, Kinkl N, Schumacher A, Braun RJ, O’Neill E, Meitinger T, Kolch W, Prokisch H, Ueffing M: The Parkinson disease causing LRRK2 mutation I2020T is associated with increased kinase activity. Hum Mol Genet 2006, 15(2):223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McClendon CL, Kornev AP, Gilson MK, Taylor SS: Dynamic architecture of a protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111(43):E4623–4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ito G, Okai T, Fujino G, Takeda K, Ichijo H, Katada T, Iwatsubo T: GTP binding is essential to the protein kinase activity of LRRK2, a causative gene product for familial Parkinson’s disease. Biochemistry 2007, 46(5):1380–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Biosa A, Trancikova A, Civiero L, Glauser L, Bubacco L, Greggio E, Moore DJ: GTPase activity regulates kinase activity and cellular phenotypes of Parkinson’s disease-associated LRRK2. Hum Mol Genet 2013, 22(6):1140–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nguyen APT, Tsika E, Kelly K, Levine N, Chen X, West AB, Boularand S, Barneoud P, Moore DJ: Dopaminergic neurodegeneration induced by Parkinson’s disease-linked G2019S LRRK2 is dependent on kinase and GTPase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117(29):17296–17307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nichols RJ, Dzamko N, Morrice NA, Campbell DG, Deak M, Ordureau A, Macartney T, Tong Y, Shen J, Prescott AR et al. : 14-3-3 binding to LRRK2 is disrupted by multiple Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations and regulates cytoplasmic localization. Biochem J 2010, 430(3):393–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berwick DC, Harvey K: LRRK2 functions as a Wnt signaling scaffold, bridging cytosolic proteins and membrane-localized LRP6. Hum Mol Genet 2012, 21(22):4966–4979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vetter IR, Wittinghofer A: The guanine nucleotide-binding switch in three dimensions. Science 2001, 294(5545):1299–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ford B, Boykevisch S, Zhao C, Kunzelmann S, Bar-Sagi D, Herrmann C, Nassar N: Characterization of a Ras mutant with identical GDP- and GTP-bound structures. Biochemistry 2009, 48(48):11449–11457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tolosa E, Vila M, Klein C, Rascol O: LRRK2 in Parkinson disease: challenges of clinical trials. Nat Rev Neurol 2020, 16(2):97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ness D, Ren Z, Gardai S, Sharpnack D, Johnson VJ, Brennan RJ, Brigham EF, Olaharski AJ: Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2)-deficient rats exhibit renal tubule injury and perturbations in metabolic and immunological homeostasis. PLoS One 2013, 8(6):e66164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tong Y, Giaime E, Yamaguchi H, Ichimura T, Liu Y, Si H, Cai H, Bonventre JV, Shen J: Loss of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 causes age-dependent bi-phasic alterations of the autophagy pathway. Mol Neurodegener 2012, 7:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herzig MC, Kolly C, Persohn E, Theil D, Schweizer T, Hafner T, Stemmelen C, Troxler TJ, Schmid P, Danner S et al. : LRRK2 protein levels are determined by kinase function and are crucial for kidney and lung homeostasis in mice. Hum Mol Genet 2011, 20(21):4209–4223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fuji RN, Flagella M, Baca M, Baptista MA, Brodbeck J, Chan BK, Fiske BK, Honigberg L, Jubb AM, Katavolos P et al. : Effect of selective LRRK2 kinase inhibition on nonhuman primate lung. Sci Transl Med 2015, 7(273):273ra215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li T, Yang D, Zhong S, Thomas JM, Xue F, Liu J, Kong L, Voulalas P, Hassan HE, Park JS et al. : Novel LRRK2 GTP-binding inhibitors reduced degeneration in Parkinson’s disease cell and mouse models. Hum Mol Genet 2014, 23(23):6212–6222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li T, He X, Thomas JM, Yang D, Zhong S, Xue F, Smith WW: A novel GTP-binding inhibitor, FX2149, attenuates LRRK2 toxicity in Parkinson’s disease models. PLoS One 2015, 10(3):e0122461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thomas JM, Li T, Yang W, Xue F, Fishman PS, Smith WW: 68 and FX2149 Attenuate Mutant LRRK2-R1441C-Induced Neural Transport Impairment. Front Aging Neurosci 2016, 8:337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rogne P, Rosselin M, Grundstrom C, Hedberg C, Sauer UH, Wolf-Watz M: Molecular mechanism of ATP versus GTP selectivity of adenylate kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115(12):3012–3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Helton LG, Soliman A, von Zweydorf F, Kentros M, Manschwetus JT, Hall S, Gilsbach B, Ho FY, Athanasopoulos PS, Singh RK et al. : Allosteric Inhibition of Parkinson’s-Linked LRRK2 by Constrained Peptides. ACS Chem Biol 2021, 16(11):2326–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singh RK, Soliman A, Guaitoli G, Stormer E, von Zweydorf F, Dal Maso T, Oun A, Van Rillaer L, Schmidt SH, Chatterjee D et al. : Nanobodies as allosteric modulators of Parkinson’s disease-associated LRRK2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]