Abstract

γδ T cells are widely distributed throughout mucosal and epithelial cell-rich tissues and are an important early source of IL-17 in response to several pathogens. Like αβ T cells, γδ T cells undergo a stepwise process of development in the thymus that requires recombination of genome-encoded segments to assemble mature T cell receptor (TCR) genes. This process is tightly controlled on multiple levels to enable TCR segment assembly while preventing the genomic instability inherent in the double-stranded DNA breaks that occur during this process. Each TCR locus has unique aspects in its structure and requirements, with different types of regulation before and after the αβ/γδ T cell fate choice. It has been known that Runx and Myb are critical transcriptional regulators of TCRγ and TCRδ expression, but the roles of E proteins in TCRγ and TCRδ regulation have been less well explored. Multiple lines of evidence show that E proteins are involved in TCR expression at many different levels, including the regulation of Rag recombinase gene expression and protein stability, induction of germline V segment expression, chromatin remodeling, and restriction of the fetal and adult γδTCR repertoires. Importantly, E proteins interact directly with the cis-regulatory elements of the TCRγ and TCRδ loci, controlling the predisposition of a cell to become an αβ T cell or a γδ T cell, even before the lineage-dictating TCR signaling events.

Graphical Abstract

E proteins transcription factors regulate the rearrangement and expression of TCR genes and the generation of γδ T cells in the thymus (purple and pink structure).

1. Introduction

Two main categories of T cells are present in jawed vertebrates, as defined by their T cell receptor (TCR) chains (Rast et al., 1997). αβ T cells express a TCR composed of TCRα and TCRβ chains and include the conventional “helper” and “killer” T cells that execute the adaptive immune response. γδ T cells express a complex of TCRγ and TCRδ chains which are tightly linked to their functional capabilities (Anderson & Selvaratnam, 2020). γδ T cells perform critical functions, including defense against infection, cancer cell lysis, and maintenance of microbial homeostasis and barrier tissue integrity (Y. S. Chen et al., 2020; Hovav, Wilharm, Barel, & Prinz, 2020; Mikulak et al., 2019; Papotto, Yilmaz, & Silva-Santos, 2021). γδ T cells can be either innate or adaptive (Papotto, Reinhardt, Prinz, & Silva-Santos, 2018). Innate γδ T cells acquire their functional properties within the thymus, whereas adaptive γδ T cells can differentiate in response to stimulation in the periphery (Chien, Zeng, & Prinz, 2013; Muschaweckh, Petermann, & Korn, 2017; Narayan et al., 2012; Schmolka et al., 2013; Shibata et al., 2008).

As with αβ T cells, there are four main categories of responses available to γδ T cells, including a cytotoxic program and three different cytokine profiles: the Th1 program (IFNγ) and Th2 program (IL-4), and a Th17 program (IL-17). These properties are selectively imparted to successive waves of γδ T cells during specific stages of fetal and adult life (Anderson & Selvaratnam, 2020). Vγ5+ Vδ1+ γδ T cells comprise the first γδ T subset to arise in the fetal thymus (Havran & Allison, 1988). Vγ5+ Vδ1+ γδ T cells, which develop only in the fetal thymus from fetal precursors, become lifelong skin-resident γδ T cells (Gentek et al., 2018). This is followed by the generation of IL-17 producing Vγ6+ Vδ1+ γδ T cells, which reside in mucosal tissues such as in the lung, intestine, and reproductive tract (Itohara et al., 1990; Monin et al., 2020). A second fetal subset of γδT17 T cells arises from cells expressing a Vγ4+ Vδ5+ TCR (Kashani et al., 2015). Thymic development of innate γδT17 cells expressing either Vγ4+ or Vγ6+ ceases postnatally (Sandrock et al., 2018). In the adult thymus, Vγ4+ cells can become γδT1 cells or retain a functionally naïve state that can be modulated in the periphery (“induced” γδT17s) (Buus, Odum, Geisler, & Lauritsen, 2017). IFNγ-producing Vγ4+ and Vγ1+ cells are the predominant types of γδ T cells that develop in the adult thymus. There is also a subset of Vγ1+ Vδ6.3+ γδ T cells that exhibit a Th2-like response (Gerber et al., 1999). Vγ7+ cells, which form the majority of the γδ T cell intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) in the intestine, are mainly generated outside the thymus (Di Marco Barros et al., 2016).

The key determinant of choice between the αβ lineage or the γδ lineage is signaling through either the pre-TCR or γδTCR, respectively (Fahl, Kappes, & Wiest, 2018; Zarin, Chen, In, Anderson, & Zuniga-Pflucker, 2015). The pre-TCR comprises a TCRβ chain complexed with the invariant preTα chain. Successful rearrangement of the TCRβ gene loci is required for cell surface expression of the pre-TCR, whereas rearrangement of the TCRγ and TCRδ loci is required for cell surface expression of the γδTCR. Rearrangement, which is mediated by the recombinase activating gene (Rag) proteins (Teng & Schatz, 2015), is preceded by transcription of the variable (V), diversity (D), and/or joining (J) elements in their germline configuration. Transcription increases the accessibility of the TCR loci, facilitating Rag protein binding and rearrangement. Germline transcription of V, D, or J segments is modulated by promoters directly upstream of each element in collaboration with more distal enhancers. After rearrangement, enhancers function to increase TCR expression levels. Just as importantly, silencer elements are needed to repress inappropriate TCR expression. Given the integral role of the TCR chains in γδTCR commitment, selection, and functional programming, it is essential to understand how these loci are regulated. Several key studies have defined constellations of transcription factors and cis-regulatory elements that mediate rearrangement and expression of the TCRγ and TCRδ loci in the fetal and adult thymus. Of note, the E protein transcription factors E2A and HEB have emerged as important regulators of TCRγ and TCRδ gene expression. In T cells, E proteins act as homodimers (E2A/E2A or HEB/HEB) or heterodimers (E2A/HEB) to control target gene expression by binding the E box recognition site CANNTG. E proteins regulate many layers of γδ T cell development, including the direct regulation of TCRγ and TCRδ locus expression. Here we will focus on the roles of E proteins in the regulation of the TCRγ and TCRδ loci. We will also compare them to their roles in TCRβ locus regulation and explore how E proteins can differentially regulate these three TCR encoding gene loci in a stage-specific manner.

2. T cell development

2.1. T cell developmental subsets

The earliest progenitors of T cells, known as thymic seeding progenitors, migrate into the thymus from the fetal liver in the embryo or the bone marrow in the adult. Once they enter the thymus, they undergo strong Notch signaling that initiates T-lineage gene expression and shuts down regulators of alternative lineages (Hosokawa & Rothenberg, 2021). These early T cell precursors do not express the TCR co-receptors CD4 or CD8 and are thus known as double negative cells (DNs). DN cells can be further subdivided into DN1, DN2, DN3, and DN4 cells, based on the expression of CD44 and CD25 (Godfrey, Kennedy, Suda, & Zlotnik, 1993). TCRβ, TCRδ, and TCRγ rearrangement occur at the DN2 and DN3 stages. Signaling through the pre-TCR, which contains the TCRβ chain, directs cells into the αβ-T lineage fate choice, in a process called β-selection (Dutta, Venkataganesh, & Love, 2021). γδTCR signaling is stronger than pre-TCR signaling and promotes differentiation into the γδ-T lineage (Haks et al., 2005; Hayes, Li, & Love, 2005; Zarin et al., 2018). Cells receiving a pre-TCR signal upregulates CD4 and CD8 to become double positive (DP). Pre-TCR and γδTCR signaling downregulate the Rag genes, which are later reactivated in DP cells to drive TCRα rearrangement (K. Miyazaki & Miyazaki, 2021). Subsequently, positive selection of DP thymocytes through αβTCR signaling silences Rag expression, followed by differentiation into either CD4 SP (single positive) T cells or CD8 SP T cells (Vacchio, Ciucci, & Bosselut, 2016). These cells undergo further selection events to limit autoimmune reactivity as they finish their maturation in the thymus before emigrating to the periphery (Gascoigne, Rybakin, Acuto, & Brzostek, 2016). After positive selection, during maturation, both αβ T cells and γδ T cells in the thymus downregulate CD24, which can be used as a marker to follow maturation (Zarin, Wong, Mohtashami, Wiest, & Zuniga-Pflucker, 2014).

2.2. Patterns of TCR rearrangement during the DN stages of T cell development

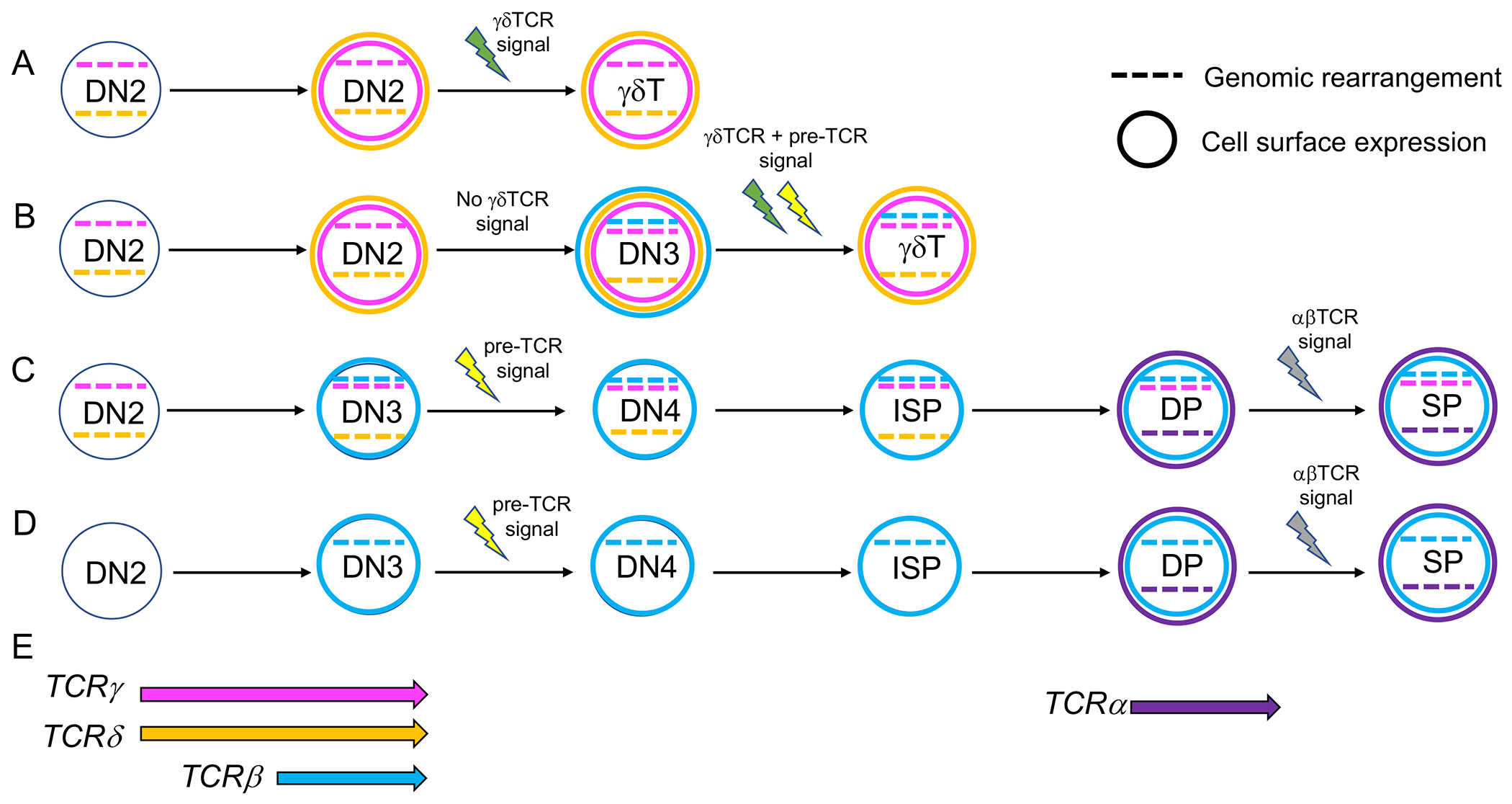

Several patterns of TCR receptor rearrangement can occur in DN thymocytes, leading to four distinct outcomes (Margolis, Yassai, Hletko, McOlash, & Gorski, 1997). In most thymocytes, rearrangement of the TCRγ and TCRδ loci occur at the DN2 stage before rearrangement of the TCRβ locus at the DN3 stage (Capone, Hockett, & Zlotnik, 1998; Livak, Tourigny, Schatz, & Petrie, 1999; Pereira, Boucontet, & Cumano, 2012; Shibata et al., 2014). Cells that successfully express and receive a signal through the γδTCR can enter the γδ T cell lineage (Figure 1A). These cells carry TCRγ and TCRδ locus rearrangements with TCRβ mostly in the germline configuration, although some may carry Trbd to Trbj rearrangements. Other cells undergo rearrangement of the TCRγ and TCRδ loci and express γδTCR on the surface. Some of these cells do not receive a strong γδTCR signal, likely due to a lack of ligand. These cells differentiate into the DN3 stage and undergo TCRβ rearrangement, resulting in the generation of a functional pre-TCR. Concurrent expression of pre-TCR and γδTCR can boost the weak γδTCR signal enough to direct the cells into the γδ T cell lineage (Zarin et al., 2014). In these cases, pre-TCR-specific components are downregulated and TCRβ expression is lost, resulting in γδ T cells with residual TCRβ locus rearrangements (Margolis et al., 1997; Pereira et al., 2012) (Figure 1B). If the TCRγ and TCRδ rearrangements are non-productive and a γδTCR is not expressed on the surface, this leads to the normal course of β-selection and generation of αβ T cells that carry out-of-frame TCRδ and/or TCRγ rearrangements (Figure 1C). The TCRδ locus is removed during TCRα rearrangement, but extrachromosomal circles containing rearranged TCRδ loci can still be detected (Kang, Baker, & Raulet, 1995; Kang & Raulet, 1997). This outcome is quite common, whereas few γδ T cells carry TCRβ rearrangements. The fourth scenario involves cells that reach the DN3 stage without rearranging the TCRγ or TCRδ loci, leading to the production of αβ T cells with the TCRγ or TCRδ loci in the germline configuration (Figure 1D). This is most likely to happen in the adult thymus, where the TCRγ, TCRδ, and TCRβ loci can rearrange simultaneously (Figure 1E). Pre-TCR signaling leads to a burst of proliferation (Dutta, Zhao, & Love, 2021; Michie & Zuniga-Pflucker, 2002). γδTCR signaling is not accompanied by a burst of expansion and may entail distinct signaling elements than those used to transmit the pre-TCR signal (Laird, Laky, & Hayes, 2010; S. Y. Lee et al., 2014; S. Y. Lee, Stadanlick, Kappes, & Wiest, 2010; Muro et al., 2018). Interestingly, the few mature T cells in the periphery that express both TCRαβ and TCRγδ share more characteristics with the γδ T cell lineage than with the αβ T cell lineage (Edwards et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Stochastic patterns of TCR rearrangement can lead to γδ T cells with TCRβ locus rearrangements and αβ T cells with rearrangements in the TCRγ locus. The TCRγ (pink) and the TCRδ (orange) loci usually rearrange at the DN2 stage, whereas the TCRβ locus (blue) undergoes rearrangement primarily in DN3 cells. A. Selection of γδ T cells prior to TCRβ locus rearrangement. B. Selection of γδ T cells after TCRβ locus rearrangement. C. Selection of αβ T cells after non-productive TCRγ and/or TCRδ locus rearrangement. D. Selection of αβ T cells before TCRγ or TCRδ locus rearrangement. E. Restricted timing of TCRβ, TCRδ, TCRγ, and TCRα rearrangement. Colored dashed lines indicate genomic rearrangement, colored circles indicate cell surface expression. Lightning signs indicate TCR signaling, green for γδTCR signaling, yellow for pre-TCR signaling, and gray for αβTCR signaling.

2.3. E protein and Id protein roles during thymocyte development.

2.3.1. E proteins.

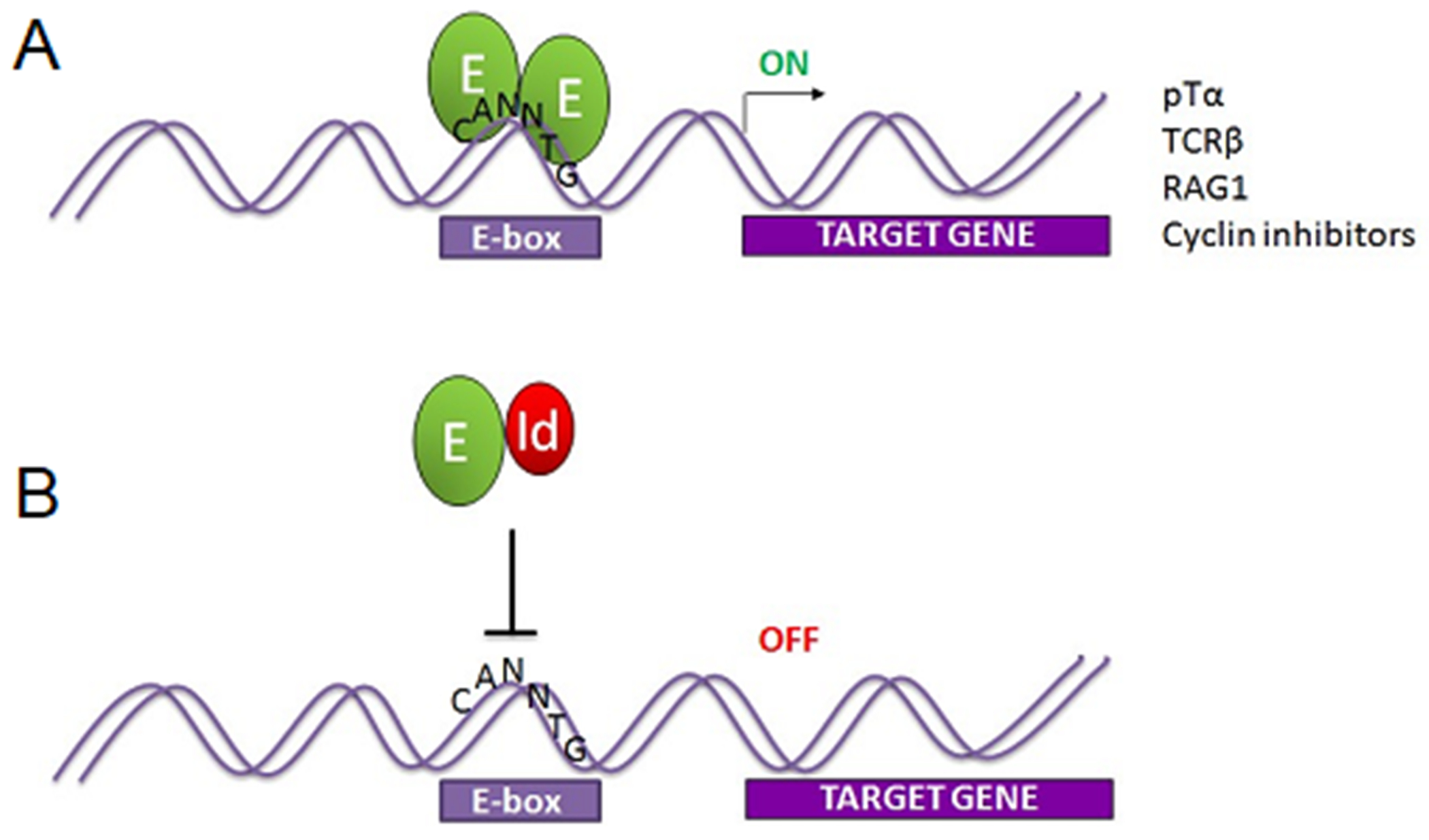

E proteins belong to the larger class of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors that operate widely in developmental processes (Murre, 2019). In vertebrates, the E proteins E2A, HEB, and E2-2 are encoded by the Tcf3, Tcf12, and Tcf4 gene loci, respectively, whereas E proteins are represented in invertebrates by one gene locus, such as SpE in the sea urchin and Daughterless in Drosophila (Kee, 2009; Schrankel, Solek, Buckley, Anderson, & Rast, 2016). In most tissue types, E proteins (also known as Class I bHLH factors) dimerize with tissue-specific Class II bHLH factors to drive lineage-specific genes during differentiation. However, in T cells, HEB and E2A dimerize with themselves, as homodimers, or with each other, as heterodimers, to drive T cell specific gene expression (Figure 2) (Belle & Zhuang, 2014; Zhuang, Barndt, Pan, Kelley, & Dai, 1998). E2A and HEB directly regulate most of the genes required for assembly of the pre-TCR and its associated signaling components (M. Miyazaki et al., 2017; M. Miyazaki et al., 2011; Tremblay, Herblot, Lecuyer, & Hoang, 2003). However, E2A−/− and HEB−/− mice exhibit different partial blocks in development, indicating that E2A homodimers and HEB homodimers cannot completely substitute for HEB/E2A heterodimers (Bain et al., 1997; Barndt, Dai, & Zhuang, 1999; Engel, Johns, Bain, Rivera, & Murre, 2001; Ikawa, Kawamoto, Goldrath, & Murre, 2006). Conditional removal of both E2A and HEB from early T cell precursors causes a severe block at the DN2 stage and allows the outgrowth of ILCs (M. Miyazaki et al., 2017; Qian et al., 2019; Wojciechowski, Lai, Kondo, & Zhuang, 2007). It is important to note that the Tcf12 locus gives rise to two HEB variants, a long form known as HEBCan, and a shorter form, HEBAlt, which are highly evolutionarily conserved (Schrankel et al., 2016; D. Wang et al., 2006). Both are expressed at the DN stage, during the rearrangement of TCRβ, TCRγ, and/or TCRδ genes, but only HEBCan is expressed in DP thymocytes during TCRα rearrangement (Rothenberg, Moore, & Yui, 2008; D. Wang et al., 2006). E2A and HEB can bind to co-activators, such as CBP/p300, and to co-repressors, such as ETO and the polycomb repressor complex (PRC) (Bradney et al., 2003; Teachenor et al., 2012; Yi et al., 2020; Yoon, Foley, & Baker, 2015; J. Zhang, Kalkum, Yamamura, Chait, & Roeder, 2004). E2A can also associate with the chromatin remodeling protein CHD4 (also known as Mi2β) (Teachenor et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2004), which mediates either transcriptional activation or repression, depending on the context (Ramirez & Hagman, 2009).

Figure 2.

E protein transcription factors E2A and/or HEB form dimers that bind the “E-box” sequence CANNTG and activate transcription. A. Binding of E protein dimers drives expression of E protein target genes, which include many T-lineage genes. B. Id proteins disrupt E protein dimers to form inactive dimers that cannot bind DNA, causing the loss of E protein target gene expression. Green oval=E protein, red oval = Id protein.

2.3.2. Id proteins.

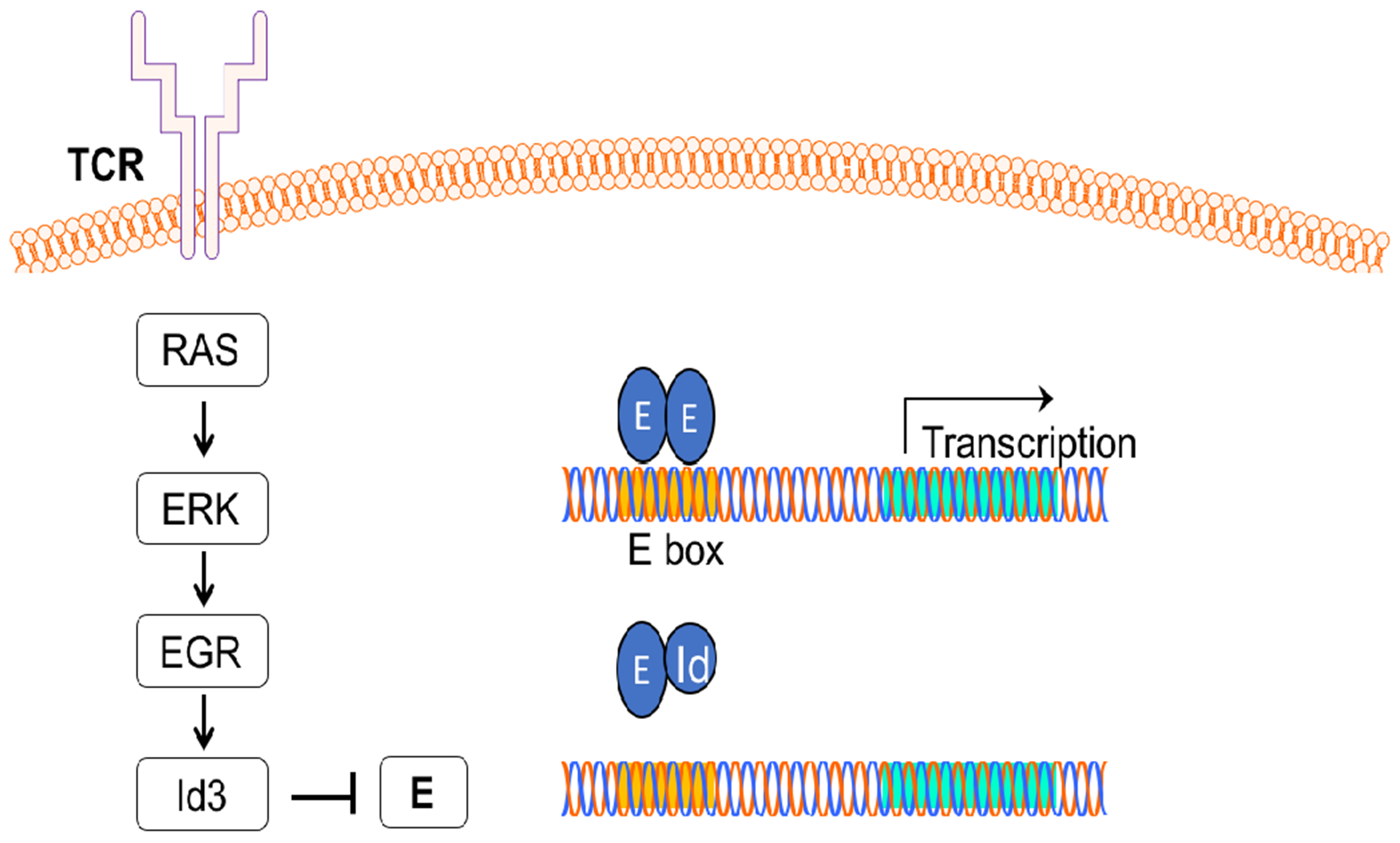

Id proteins regulate E protein activity by forming inactive heterodimers (Figure 2). Early in T cell development, the balance between Id2 and HEB/E2A determines the fate choice between the T cell lineage and ILC lineages (M. Miyazaki et al., 2017; Qian et al., 2019; Zook et al., 2018). Pre-TCR or γδTCR signaling results in upregulation of Id3 and suppression of E protein target genes (Figure 3) (M. Miyazaki et al., 2011; Xi, Schwartz, Engel, Murre, & Kersh, 2006; Yashiro-Ohtani et al., 2009). Id3 is induced weakly in response to pre-TCR signaling, and strongly in response to γδTCR signaling, and acts as a determinant of the αβ/γδ T cell fate choice (Fahl et al., 2018; Lauritsen et al., 2009; Zarin et al., 2018). As DP cells undergo positive selection, αβTCR signaling induces another transient period of Id3 expression, once again halting E protein activity (Bain et al., 2001; Bain, Quong, Soloff, Hedrick, & Murre, 1999). The initial characterization of Id3−/− mice did not support this paradigm, as the thymus of Id3−/− mice exhibit a greatly expanded population of Vγ1+ Vδ6.3+ γδ T cells in the adult thymus. However, this was not due to a role for Id3 in suppressing the γδ T cell fate but was instead due at least in part to uncontrolled regulation of the pro-proliferative factor c-myc in committed Vγ1+ Vδ6.3+ cells (B. Zhang, Jiao, Dai, Wiest, & Zhuang, 2018). Furthermore, these cells secreted massive amounts of IL-4, which had secondary effects on αβ T cell development, obscuring intrinsic aspects of Id3-deficiency (M. Miyazaki et al., 2011; Verykokakis, Boos, Bendelac, Adams, et al., 2010; Verykokakis, Boos, Bendelac, & Kee, 2010; B. Zhang et al., 2018). However, γδTCR-restricted backgrounds and in vitro culture models were used to show that loss of Id3 activity predisposes DN3 cells to enter the αβ T cell lineage even when a γδTCR signal is received, revealing the role of Id3 in the αβ/γδ lineage choice (Lauritsen et al., 2009). While periods of TCR signaling followed by transient periods of Id3 expression are essential for T cell development, it is unclear how the balance between E protein and Id3 activity controls E protein target gene expression (Anderson & Selvaratnam, 2020).

Figure 3.

TCR signaling causes downregulation of E protein target genes by upregulating Id3 in response to the RAS-ERK-EGR signaling pathway.

3. Structure of the TCR gene loci

3.1. TCRβ gene locus

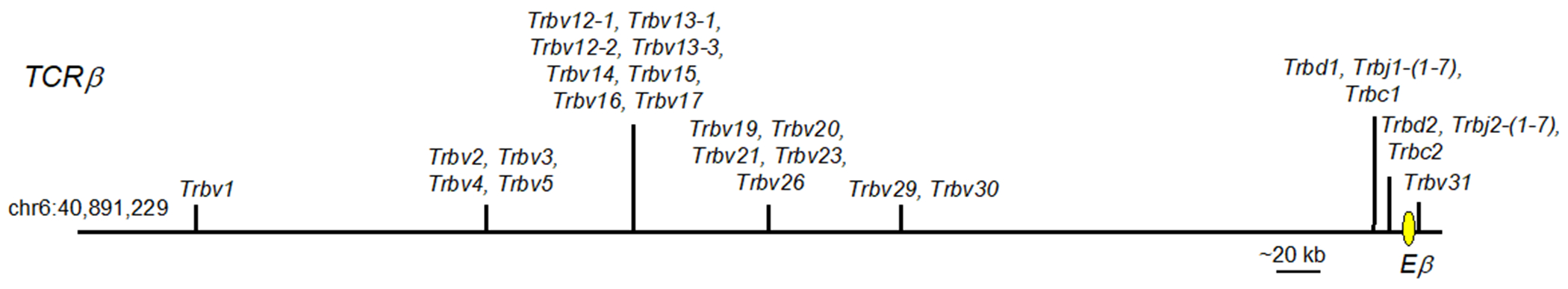

The TCRβ gene locus in mice is composed of a tandem array of V (T cell receptor beta variable; Trbv) segments (Trbv1-Trbv30) located upstream of one D (T cell receptor beta diversity; Trbd) segment (Trbd1), seven J (T cell receptor beta joining; Trbj) segments (Trbj1-(1-7)), and a constant region exon (T cell receptor beta constant; Trbc) (Figure 4) (Majumder et al., 2015). Due to a duplication event, Trbc1 is followed by a second cluster composed of one D (Trbd2), seven J Trbj2 (1-7) elements, and a second constant region exon (Trbc2). Downstream of Trbc2 is a final Trbv segment (Trbv31) in the opposite transcriptional orientation to the rest of the TCRβ locus. Germline transcription of the Trbv elements provides accessibility to the recombinases encoded by the Rag gene locus allowing TCRβ locus rearrangement, which occurs in two steps. First, a Trbd element rearranges to a Trbj element. Next, a Trbv segment rearranges to the fused Trbd-Trbj elements to generate a Trbv-Trbd-Trbj segment that encodes the VβDβJβ portion of the TCRβ chain. This event brings the Trbv gene promoter into proximity with the TCRβ locus enhancer (Eβ), allowing increased expression. Mature TCRβ encoding transcripts are generated by splicing of the VβDβJβ-encoding exons to the Trbc exon.

Figure 4.

Germline configuration of the mouse TCRβ locus. Vertical lines indicate the positions of elements or groups of elements. V elements=Trbv, J elements=Trbj, C exon=Trbc. Yellow oval = TCRβ enhancer (Eβ).

3.2. TCRγ gene locus

Two nomenclatures are commonly used to designate Trgv (T cell receptor gamma variable) segments: the Tonegawa system (Heilig & Tonegawa, 1986), and the Raulet system (Garman, Doherty, & Raulet, 1986). Here we are using the Tonegawa system. The naming conventions for TCR genes and proteins used in this review are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nomenclature used to designate specific TCRγ and TCRδ genomic segments and exons (left) and the proteins generated from rearrangement (right) and expression of those segments.

| Gene | Protein |

|---|---|

| TCRγ locus | TCRγ |

| Trgv1 | Vγ1 |

| Trgv4 | Vγ4 |

| Trgv5 | Vγ5 |

| Trgv6 | Vγ6 |

| Trgv7 | Vγ7 |

| Trgj1 | Jγ1 |

| Trgc1 | Cγ1 |

| Trgj4 | Jγ4 |

| Trgc4 | Cγ4 |

| TCRδ locus | TCRδ |

| Trdv1 | Vδ2 |

| Trdv4 | Vδ1 |

| Trdv5 | Vδ5 |

| Trdv2-1 | Vδ4 |

| Trd2-2 | Vδ4 |

| Trdj1, Trdj2 | Jδ1, Jδ2 |

| Trdd1, Trdd2 | Dδ1, Dδ2 |

| Trdc | Cδ |

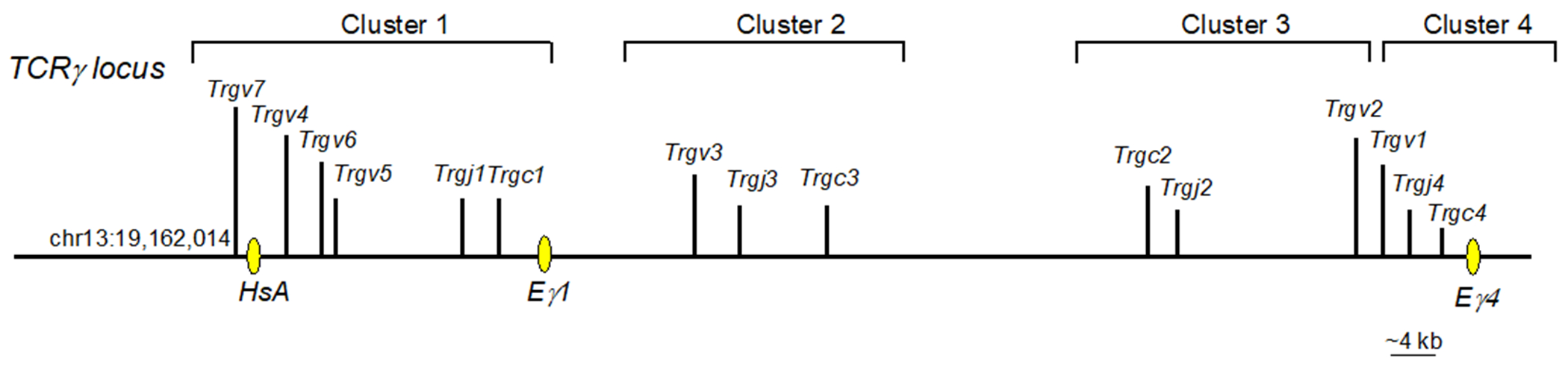

The TCRγ gene locus is comprised of four tandemly arranged clusters with dedicated Trgv, Trgj and Trgc segments (Figure 5). Rearrangement of TCRγ encoding elements does not occur between different clusters.

Figure 5.

Germline configuration of the mouse TCRγ locus. Vertical lines indicate the placement of elements or exons. V elements=Trgv, J elements=Trgj, C exons=Trgc. Yellow ovals = enhancers. Pink oval = promoter.

3.2.1. TCRγ Cluster 1.

The first cluster (TCRγ locus Cluster 1) contains four Trgv segments: Trgv7, Trgv4, Trgv6, and Trgv5, which encode the Vγ7, Vγ4, Vγ6, and Vγ7 TCR chains, respectively. These elements are positioned upstream of Trgj1 and Trgc1 (Figure 5). As in the TCRβ locus, germline transcription of the Trgj segments precedes rearrangement of Trgv elements. Rearrangement of Cluster 1 V segments occurs in an ordered sequence, starting with the proximal Trgv5 segment and ending with the distal Trgv7 segment (Carding & Egan, 2002). T cells expressing Vγ5+ or Vγ6+ TCRs are only produced during fetal life (Havran & Allison, 1990; Itohara et al., 1990; Sandrock et al., 2018). In neonates, Vγ4+ γδ T cells develop, and continue to be generated throughout life, although their functional capabilities change in adulthood. The Trgv7 segment is rearranged postnatally, but unlike the other γδ T cells, most cells bearing Vγ7+ TCRs develop extrathymically and become resident intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (iIELs) (Nielsen, Witherden, & Havran, 2017). Recombined Trgv-Trgj segments form exons that can be spliced to the Trgc exon during transcription.

3.2.2. TCRγ Cluster 2.

The second cluster in the TCRγ locus consists of a cassette containing Trgv3, Trgj3, and Trgc3, which encode Vγ3, Jγ3, and Cγ3, respectively. Trgv3 and Trgc3 have accumulated mutations that render them pseudogenes, excluding them from the TCRγ repertoire (Rodriguez-Caparros et al., 2020).

3.2.3. TCRγ Cluster 3.

The third cluster in the TCRγ locus encodes a cassette oriented in the opposite transcriptional direction from Clusters 1 and 2. Cluster 3 contains one V element (Trgv2), one J element (Trgv2) and one C (Trgc2) region. This Cluster undergoes V to J rearrangement in the postnatal period. Vγ2+ γδ T cells have not been as well studied as most of the other γδ T cells, but it has been reported that they are able to adopt diverse functional properties (Buus, Geisler, & Lauritsen, 2016).

3.2.4. TCRγ Cluster 4.

The fourth cluster in the TCRγ locus contains a cassette of one V (Trgv1), one J (Trgj1), and one C (Trgc1) element. Cluster 4 is arranged in the same transcriptional orientation as Clusters 1 and 2. Trgv1 to Trgj1 rearrangement begins in early postnatal life and persists throughout life. Many Vγ1+ cells produce IFNγ upon stimulation. Cells expressing Vγ1 paired with Vδ6.3 TCR are specialized to develop into γδT2 cells, also known as γδNKT cells (Buus et al., 2017; Kreslavsky et al., 2009). Cells expressing Vγ1 paired with other TCRδ chains do not become γδNKT2 cells, indicating that TCR specificity is an important determinant of functional programming.

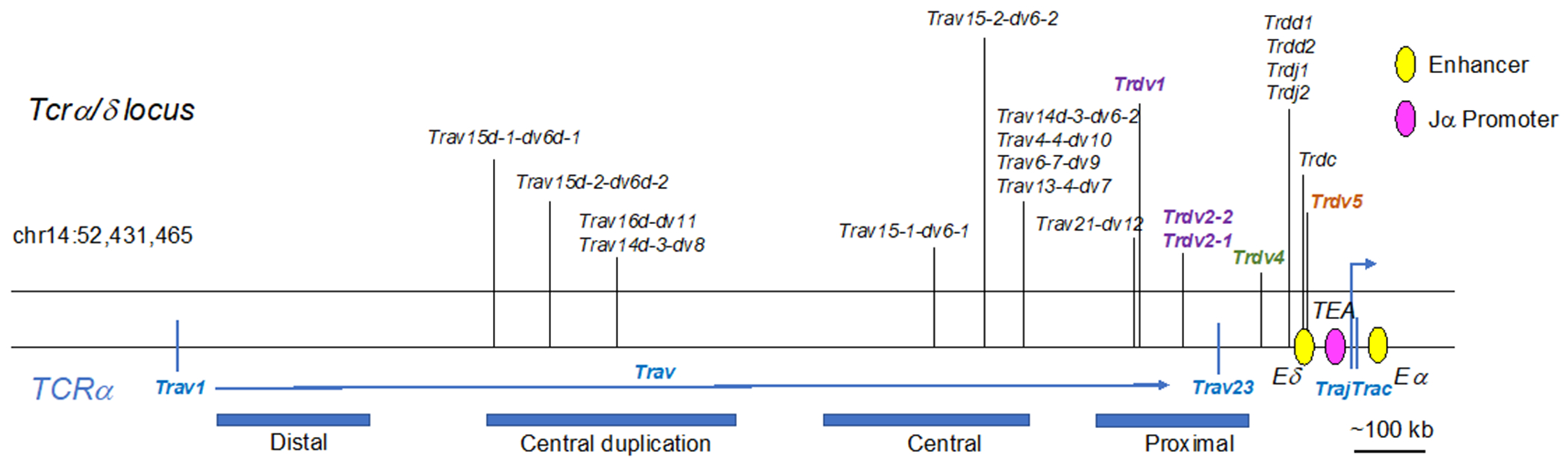

3.3. TCRα/δ gene locus

3.3.1. The TCRδ locus is embedded in the TCRα locus.

The elements encoding the TCRδ chain are located within a 1.5 megabase locus that also encodes the TCRα chain (Figure 6). This remarkable structure was first deciphered in the early 1990s (Koop & Hood, 1994), and is still a subject of intense study (Rodriguez-Caparros et al., 2020). Notably, some of the V segments in the TCRα/δ locus can be used to generate either TCRδ or TCRα chains. Thus, the TCRα/δ locus nomenclature is even more complex than the TCRγ locus nomenclature. Here we will use the nomenclature of IMGT (International Immunogenetics Information system; http://www.imgt.org) for the genes, and the standard nomenclature for the proteins (Table 1). In sum, there are five Trav/Trdv segments, which can be used to generate either TCRα or TCRδ chains, five Trdv TCRδ-specific segments, two Trdd segments, two Trdj segments, and one Trdc exon. The Trav/Trdv elements are interspersed with the Trav segments, whereas the Trdv, Trdd, Trdj elements and the Trdc exon are in a dedicated core that lies just upstream of the Traj elements and the Trac exon. Therefore, rearrangement of any Trav or Trav/Trdv elements to Traj removes the Trdd-Trdj-Trdc core, eliminating the TCRδ encoding cassette from that allele (Hernandez-Munain, 2015).

Figure 6.

Germline configuration of the mouse TCRα/δ locus. Vertical lines on the top indicate V elements that are specific to TCRδ (Trdv) rearrangement (purple or green text) and those that can be used during either TCRα or TCRδ rearrangement (black text). The blue bars on bottom indicate positional groupings of the Trav elements. Purple=Trdv elements expressed in adult thymus. Green=Trdv elements expressed in fetal thymus. Brown=Trdv elements expressed in fetal and adult thymus. Pink oval=promoter, yellow ovals=enhancers. Note that this structure represents the TCRδ locus in the 129 mouse strain. While there are some differences, the general structure and regulatory elements of the TCRδ locus are conserved in the C57Bl/6 mouse strain.

3.3.2. Trdv4.

The Trdv4 segment, which encodes the Vδ1 TCR chain, is expressed exclusively in the fetal thymus, where it can pair with either Vγ5 or Vγ6 chains (Elliott, Rock, Patten, Davis, & Chien, 1988). The TCRδ encoding gene locus also contains D (Trdd; T cell receptor delta diversity) and J (Trdj; T cell receptor delta joining) segments that participate in the rearrangement process. Rearrangement can join one or both Trdd segments to a Trgj segment, resulting in Trdv-Trdd1-Trdj, Trdv-Trdd2-Trdj, or Trdv-Trdd1-Trdd2-Trdj exons that undergo splicing to the Trdc exon during transcription (Elliott et al., 1988). Moreover, recombination intermediates containing a Trdv and a Trdd element, without prior Trdd to Trdj rearrangements, have been observed, further highlighting the unusual nature of this gene locus (Carico & Krangel, 2015; Chien et al., 1987). Significantly, the inclusion of Trdd elements increases the amount of potential diversity in TCRδ chains, which are thought to be more critical in contacting antigen than the TCRγ chain, at least in several cases (Adams, Strop, Shin, Chien, & Garcia, 2008).

3.3.3. Trdv5.

Trdv5 rearrangement begins in late fetal life, concurrently with Trdv4 segments, but Vδ5+ TCR chains are not abundantly expressed in the adult thymus (Kashani et al., 2015). γδ T cells bearing Vγ4+ Vδ5+ TCRs that arise in fetal and neonatal life are programmed in the thymus to be γδT17 cells, whereas Vγ4+ cells that develop in the adult thymus retain plasticity (In et al., 2017; Kashani et al., 2015). Unlike the other Trdv segments, the Trdv5 segment is downstream of the Trdc exon and oriented in the opposite transcriptional direction. However, it is upstream of the Trdj and Trdc segments, thus still within the TCRδ-specific region.

3.3.4. Other dedicated Trdv segments.

There are three additional V segments used exclusively to generate TCRδ chains, Trdv1, Trdv2-1, and Trdv2-2. The resulting Vδ2 and Vδ4 chains, respectively, can pair with either the Vγ4 or Vγ1 TCR chains. These Trdv segments are located upstream of Trdv4 and downstream of the shared Trav/Trdv segments, thus forming the distal end of the TCRδ core region (Carico & Krangel, 2015; Pereira et al., 2000).

3.3.5. Vα/Vδ shared segments.

A vast array of Trav elements lie upstream of the dedicated TCRδ core. Some of these elements can rearrange to either Trdd-Trdj segments or Traj segments and can be included in either TCRδ or TCRα chains (Naik, Hawwari, & Krangel, 2015). These segments are designated as Trav-dv, whereas TCRα-specific elements are specified as Trav. Due to the tandem duplication and divergence of a large section of the Vα region, the “central region” and smaller duplications within these regions, there are a series of closely related genes that have acquired a complex naming convention. For example, Trav15d-1-dv6-1 and Trav15d-2-dv6-2 are two (“1” or “2” at the end of the term) closely related elements (“15”), α/δ shared (“dv6”), and located in the duplicated central region (the “d” after Trav15). In total, there are eleven Trav/Trdv elements. These elements are incorporated into TCRδ chains only in postnatal life.

3.3.6. Trav15d-1-dv6d-1.

The Trav15d-1-dv6d-1 family of Trav/Trdv elements can rearrange to Trdd and Trdj elements, giving rise to Vδ6+ cells. This rearrangement begins in late fetal life, concurrently with Trgv1 expression (Grigoriadou, Boucontet, & Pereira, 2003), and the pairing of these chains directs γδ T cells to become IL-4 producing γδT2 cells (Gerber et al., 1999). IL-4 programming requires high-affinity TCR-ligand interaction and high Id3 expression (Alonzo et al., 2010).

4. Regulation of TCR rearrangement

Sidebar: There are many layers of regulation that control rearrangement and expression of TCR loci. These include regulation of Rag expression and activity, chromatin accessibility, cis-elements including promoters and enhancers, transcription factors, and higher-order chromatin structures, including long distance looping that brings distal and proximal elements together.

4.1. Rag1/2 expression.

The Rag1 and Rag2 genes encode Rag1 and Rag2 proteins that form the molecular complex responsible for cleaving and re-joining the V, D, and J elements (Teng & Schatz, 2015). The Rag1/2 protein complex is targeted to these elements by the presence of recombination signal sequences (RSSs) at the 3’ end of V segments, the 5’ and 3’ ends of D segments, and the 5’ ends of J segments. Strict regulation of Rag1/2 expression and function is necessary to preserve genomic integrity during T cell development (Fisher, Rivera-Reyes, Bloch, Schatz, & Bassing, 2017; Gladdy et al., 2003). The Rag1 and Rag2 genes are tandemly arranged within one locus in a head-to-head orientation. Rag locus gene expression is regulated by T-cell specific and B-cell specific regulatory elements, both of which require E2A binding (Yoshikawa, Miyazaki, Ogata, & Miyazaki, 2021). In T-lineage cells, E2A binds to the Rag1 promoter, and to an element called T-enh (T-enhancer). In DN3 cells, E2A binds to one site in T-enh, but in DPs, where Rag expression is much higher, E2A binds to a second site as well. E2A also mediates the formation of a chromatin hub that regulates chromosomal looping, bringing the locus into the correct 3D conformation for high expression in DPs (K. Miyazaki & Miyazaki, 2021). This is at least in part due to the interplay between a silencer, positioned between Rag1 and Rag2, and T-enh, also designated as the DP-specific anti-silencer element (ASE) (Yannoutsos et al., 2004), 73 kb upstream of Rag2. T-enh/ASE requires direct binding of E2A, Runx transcription factors, and the matrix attachment protein SATB-1 to counteract the silencer (Naik, Byrd, Lucander, & Krangel, 2019). Rag2 activity is also regulated at a post-translational level due to cell cycle-induced degradation at the G1 to S transition (Jiang et al., 2005). Since E2A regulates cell cycle inhibitors prior to β-selection, E protein activity also indirectly supports Rag2 protein stability and function (Wojciechowski et al., 2007).

4.2. TCR locus accessibility.

Both B cells and T cells use Rag proteins to rearrange the Ig or TCR gene loci, respectively. This raises question of how rearrangement is restricted to TCR loci in T cells. The answer to this lies primarily in chromatin configuration, more broadly known as epigenetics (Dutta, Venkataganesh, et al., 2021). In progenitor cells or cells committed to other lineages, TCR loci are packaged in tightly wound nucleosome structures known as heterochromatin, in a “closed” configuration (K. Miyazaki & Miyazaki, 2021). Genes that are in closed chromatin are inaccessible to transcription factors, except for a subset of factors that are lineage-specific and have “pioneering” activity (Chang, Wherry, & Goldrath, 2014). Even in closed chromatin, there are some transient stochastic moments that loosen chromatin structure. This chromosomal “breathing” provides short windows of opportunity for lineage-specific transcription factors to scan the DNA for target genes. When the transcription factors bind the site and recruit histone acetylases or other chromatin remodeling factors, the chromatin becomes less compact, allowing additional transcription factors to bind and initiate gene expression. In the case of TCR loci, germline transcription of the V and J segments prior to rearrangement is an important part of providing accessibility of the RSSs to Rag1/2 and allowing recombination to occur (Abarrategui & Krangel, 2006). E2A is a pioneering factor that collaborates with other elements in remodeling chromatin to allow access to either T-lineage or B-lineage genes (K. Miyazaki et al., 2020). Therefore, other more T-restricted factors provide the specificity for TCR expression in T cells but not B cells.

5. Transcriptional control of the TCR loci

Sidebar: Although their segmental structures are different certain principles of regulation are shared between TCR loci. The first is that germline transcription of the segmental V, D, and/or J elements is required to make them accessible to the recombination machinery, and promoter and enhancer elements mediate this transcription. The second principle is that rearrangement brings these promoters closer to an enhancer situated downstream of the constant region, upregulating expression. Thirdly, there are sites between the proximal and distal V elements s, enabling chromosomal looping that brings the distal elements closer to the (D)-J-C core of the locus, enabling their expression after the proximal elements have had a chance to be rearranged.

5.1. TCRβ locus.

The TCRβ locus contains D elements in addition to V and J elements, and germline transcription occurs from both the Trbv and Trbd elements. In addition to the Trbv and Trbd promoters, there is also an enhancer, termed Eβ, downstream of the Trbc constant region. CTCF sites in the middle of the TCRβ locus mediate chromosomal looping, enabling rearrangement of distal Trbv regions (S. Chen & Krangel, 2018; Majumder et al., 2015; Shrimali et al., 2012). E2A activates the Trbd promoter (McMillan & Sikes, 2009), and binds directly to the promoter of Trbv13-2, inducing germline transcription (Jia, Dai, & Zhuang, 2008). However, E2A is no longer needed at the DP or SP stage to maintain the expression of rearranged Trbv13-2 transcripts. Since E2A can bind and recruit chromatin remodeling histone acetylases to its target sites, the primary role of E2A in Trbv13-2 and Trbd induction may be to provide access of these elements to the recombination machinery (Bradney et al., 2003; Denis et al., 2014). However, Eβ is also under the control of E proteins, suggesting they continue to be involved in TCRβ regulation after rearrangement (Agata et al., 2007; Barndt et al., 1999). Interestingly, loss of HEB does not appear to interfere with TCRβ rearrangement or expression (Barndt et al., 1999; Braunstein & Anderson, 2010; Takeuchi et al., 2001).

5.2. TCRγ locus.

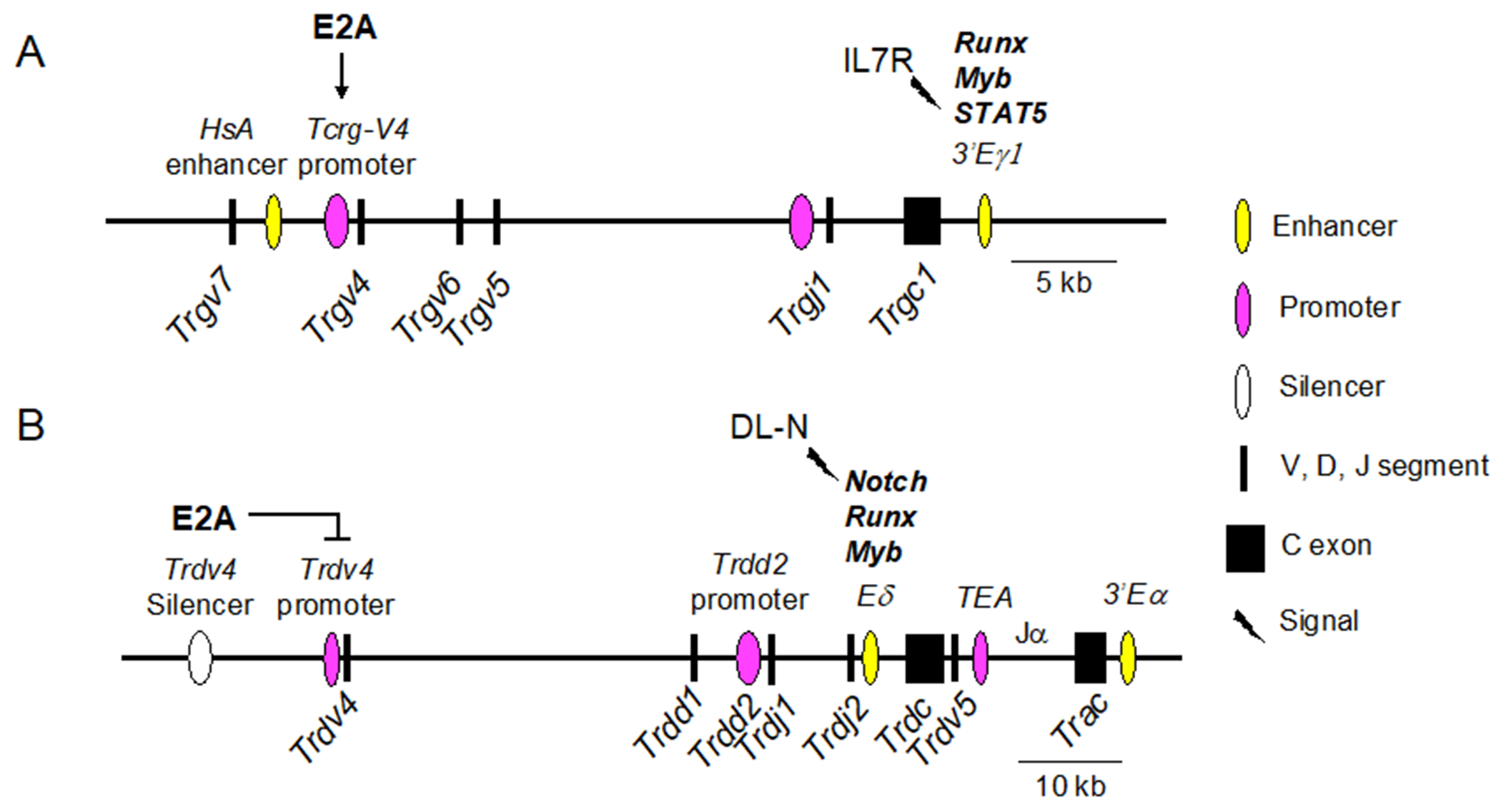

Cluster 1 of the TCRγ locus is the best studied cluster regarding transcriptional regulation (Figure 7A). E2A binds directly to the Trgv4 promoter and is needed for Trgv4 expression (Bain, Romanow, Albers, Havran, & Murre, 1999; Nozaki et al., 2011), whereas HEB is required for Trgv4 expression only in fetal thymocytes (In et al., 2017). Early studies used hypersensitivity assays to locate regions of chromatin accessibility that might be sites of regulation, leading to the discovery of an enhancer-like region, termed HsA, between the Trgv7 and Trgv4 segments in Cluster 1. The most important role of HsA appears to be the maintenance of Trgv4 expression in the periphery (Xiong, Kang, & Raulet, 2002). There are also classical enhancer elements downstream of the Trgc1 exon (Eγ1) and the Trgc4 exon (Eγ4). HsA works in conjunction with ECγ1 to boost Trgv4, Trgv6, or Trgv5 transcription levels, but does not affect Trgv7 transcription. Transgenic manipulation of the Cluster 1 locus showed that swapping the promoters of Trgv5 and Trgv4 altered the order of rearrangement in the adult thymus, whereas swapping the positions of the Trgv5 and Trgv4 segments affected Trgv5 rearrangement in the fetus (Xiong & Raulet, 2007; Xiong, Zhang, Kang, & Raulet, 2008). Moreover, in the adult thymus of E2A-deficient mice, Trgv5 rearrangement was aberrantly activated, and Trgv4 rearrangement was diminished, thus reversing the normal pattern (Bain, Romanow, et al., 1999). This finding suggests that E2A plays a role in suppressing Trgv5 while promoting Trgv4 rearrangement and expression in the adult thymus. E2A and HEB also bind directly to regions in HsA, Eγ, and a site downstream of Trgv4, enabling chromatin accessibility by recruiting the histone acetylase p300/CBP (Nozaki et al., 2011). The importance of E2A and HEB in TCRγ locus accessibility was also shown by the finding that forcing expression of these factors in non-lymphoid cell lines enabled rearrangement of multiple Trgv and Trdv segments in the presence of Rag proteins (Ghosh, Romanow, & Murre, 2001; Langerak, Wolvers-Tettero, van Gastel-Mol, Oud, & van Dongen, 2001). Thus, E2A and HEB play roles in both positive and negative regulation of TCRγ expression prior to γδTCR signaling.

Figure 7.

Differential control of TCRγ and TCRδ loci is regulated by Runx factors, Myb, and E2A, in combination with signaling through Notch and IL-7 receptors, respectively. Core regions of TCRγ Cluster 1 (A) and the TCRδ locus (B). Vertical arrow downward = positive regulation, flat horizontal line = negative regulation. Key for symbols is shown to the right.

Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 are also subject to regulation by Runx, Myb, and STAT5 (Figure 7A). Runx and Myb are recruited to the TCRγ locus, where they bind Eγ1 and Eγ4 and drive a baseline level of TCRγ expression in developing T cell precursors (Tani-ichi, Satake, & Ikuta, 2009). Notch1 activity facilitates the recruitment of Runx1 and Myb to both the TCRγ and the TCRδ loci in DN2/3 cells (Rodriguez-Caparros et al., 2019). STAT5, which is activated by signaling through the IL-7 receptor, binds to the Trgj1 and Trgj4 germline promoters. STAT5 also binds to Eγ1 and Eγ4 after Runx and Myb have bound, recruiting histone acetylases and increasing expression (Masui, Tani-ichi, Maki, & Ikuta, 2008; Tani-ichi et al., 2009; Wagatsuma et al., 2015). Thus, Runx and Myb binding constitutes a first step in TCRγ locus accessibility at the enhancer site, followed by further chromatin remodeling and transcriptional elevation by activated STAT5. As cells enter the αβ-lineage after passing β-selection, pre-TCR signaling downregulates IL-7R expression, which halts STAT5 activity, resulting in the silencing of the TCRγ locus (Tani-Ichi, Satake, & Ikuta, 2011). Moreover, experiments in which pre-TCR stimulation was mimicked resulted in the downregulation of Notch, Runx1, and Myb, suggesting that pre-TCR signaling causes a global decrease in the factors needed to sustain TCRγ expression (Rodriguez-Caparros et al., 2019). STAT5 is also required for the expression of Trgv4 (Masui et al., 2008). E2A and HEB are complementary to these factors, prior to γδTCR signaling, by initiating or suppressing transcription of specific Trgv and Trdv genes before rearrangement. After γδ-T lineage commitment, E proteins do not appear to be needed for sustained Trgv or Trdv expression.

5.3. TCRα/δ locus.

Germline transcription of Trdv and Trav segments is instrumental in providing accessibility for recombination (Y. N. Lee et al., 2009). There are two critical enhancers in the TCRα/δ locus that regulate the expression of TCRδ and TCRα chains in a stage-specific manner, including the switch from TCRδ to TCRα expression as cells differentiate along the αβ T-lineage pathway (Figure 6) (Hernandez-Munain, 2015; Hernandez-Munain, Sleckman, & Krangel, 1999). The TCRδ enhancer (Eδ) is just upstream of the Trdc exon. As in the TCRγ locus, rearrangement of Trdv to Trdd-Trdv brings the Trdv promoters in closer proximity to Eδ, increasing expression. Just downstream of Eδ is the T early activation (TEA) promoter, which drives germline expression of the Traj segments (Huang & Sleckman, 2007). Finally, there is a TCRα enhancer (Eα) downstream of the Trac exon, at the 3’ end of the TCRα/δ locus. In DN T cells, TEA, Eδ, and Eα are occupied, even though TCRα rearrangement does not begin until the DP stage (Rodriguez-Caparros et al., 2020). Cells that pass β-selection silence Eδ, followed by the excision of the TCRδ -specific cassette, including Eδ, during TCRα rearrangement (Hernandez-Munain et al., 1999). There is also a stage-specific silencer upstream of the Trdv4 segment that restricts Trdv4 expression to the fetal thymus (Hao & Krangel, 2011). E2A regulates this silencer. Consequently, the loss of E2A de-represses the Trdv4 segment in the adult thymus (Bain, Romanow, et al., 1999). Therefore, E2A plays a critical role in maintaining the fidelity of the fetal and adult γδ T cell repertoire, in part by directly controlling the expression of Trgv4, Trgv5, and Trdv4.

In addition to their roles in TCRγ expression, Runx and Myb are also critical regulators of TCRδ expression (Figure 7B) (Carabana, Ortigoza, & Krangel, 2005). These factors are strong drivers of germline transcription at the Trdd2 germline promoter and activate the Eδ enhancer. Interestingly, Runx and Myb also directly activate Rag2 expression, indicating that they provide a link between the expression of the TCRγ and TCRδ loci and the recombination machinery that assembles their elements into mature TCR genes (Q. F. Wang, Lauring, & Schlissel, 2000; Yannoutsos et al., 2004). Runx1 and Ets1 regulate TCRβ expression, but Myb does not, providing combinatorial context for differential expression of multiple TCR loci under the control of Runx factors (Zhao, Osipovich, Koues, Majumder, & Oltz, 2017). GATA3 has been implicated in activation of Eδ and control of Trbd accessibility (Ko et al., 1991; McMillan & Sikes, 2009). E2A, by contrast, directly represses inappropriate rearrangement of Trdv4 in the adult and allows rearrangement of Trdv5 and Trdv2-2 in the adult thymus. E2A is necessary to enforce the fetal-adult switch in the Vγ and the Vδ repertoires. Most E protein activity appears to be on regions upstream of Trgv and Trdv rather than on Eγ or Eδ, emphasizing the role of E proteins in providing accessibility to V and D segments in the TCR loci.

6. Other considerations.

6.1. Regulation of human TCR loci.

Here we have focused on the regulation of TCR loci in the mouse since they have been studied extensively. However, there is also great interest in understanding the nature and regulation of human TCRγ and TCRδ loci. This interest is rising, in part due to the newly realized potential of γδ T cells in immunotherapy, and the recognition of the roles they play in inflammation (Mikulak et al., 2019; Simoes, Di Lorenzo, & Silva-Santos, 2018). Gaining a better understanding of the evolution of these fascinating gene loci also sustains this interest (Dornburg & Yoder, 2022). The constant regions of all four TCRs are clearly recognizable as α, β, γ, or δ throughout the vertebrates (Dixon et al., 2021 ; Rast et al., 1997; Rauta, Nayak, & Das, 2012). Due to the rapid rate of antigen receptor evolution (Radtanakatikanon et al., 2020), V, D, and J segments of the TCRγ and TCRδ genes cannot be assigned homology between mice and humans. However, the genomic structures of the TCR loci are highly conserved between mice and humans, and they employ the same mechanisms of rearrangement (Koop & Hood, 1994). Human γδ T cells that produce IL-17 express many of the same regulators that operate in γδT17 cells in mice, indicating conserved pathways (Fujikado et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2021). Significant features of intestinal intraepithelial cells are also shared between humans and mice (Di Marco Barros et al., 2016). Moreover, developmental pathways that lead to innate or adaptive function are conserved between humans and mice (Papadopoulou, Sanchez Sanchez, & Vermijlen, 2020).

Interestingly, circulating and tissue resident γδ T cells in humans are not linked to Vγ identity, but rather to Vδ identity. Specifically, Vδ2+ cells are the predominant subset in the blood, whereas Vδ1+ cells are most highly represented in tissues (Gully, Rossjohn, & Davey, 2021). Studies of human T cell development were hampered for many years by physical and ethical limitations. It is fortunate that these roadblocks are being overcome now due to technical advances in single cell transcriptomics, in vitro culture systems, humanized mice, and human pluripotent stem cells (PSC) (Awong & Zuniga-Pflucker, 2013; Brauer et al., 2016; Hildebrandt et al., 2019; Park et al., 2020). Using these tools, roles for E proteins in human T cell development are starting to be revealed. For example, deletion of HEB from human PSCs inhibited in vitro T cell development (Li et al., 2017). Furthermore, an in vitro study showed that overexpression of Id3 blocked human αβ but not γδ T cell development, consistent with the preTCR/γδTCR signal strength model (Blom et al., 1999). In addition, the studies in which E2A and HEB were able to provide accessibility to TCRγ and TCRδ genes were performed in human kidney cells (Ghosh et al., 2001). Therefore, it is likely that the initiation of TCR expression by E proteins is very similar in mice and humans, even though the Vγ and Vδ sequences are not.

6.2. The role of HEB in TCR rearrangement and expression.

Most of the E protein dependent regulation described in this review has focused on E2A and not HEB. Is there a specific role of HEB in these processes? This is an especially pertinent question given the presence of both HEBAlt and HEBCan at the times of TCRγ, TCRδ, and TCRβ rearrangement, whereas only HEBCan is expressed at the DP stage, concurrently with TCRα rearrangement. Studies of the respective roles of HEB and E2A have been hampered for several reasons. First, the germline deletion of HEB was neonatal lethal in the original 129/B6 knockout strain, and when bred onto a fully C57Bl/6 background, it became embryonic lethal around E18.5 (In et al., 2017; Zhuang, Cheng, & Weintraub, 1996). The germline E2A deletion was not lethal, rendering E2A−/− mice easier to study than the HEB−/− mice. Secondly, when conditional alleles became available, it was recognized that partial redundancy between E2A and HEB was masking some of the E protein-dependent events, leading to muted phenotypes (Jones & Zhuang, 2011). Therefore, most investigators have taken the approach of double-deletions of E2A and HEB with specific Cre drivers, instead of studying E2A and HEB separately (Bouderlique et al., 2019; D’Cruz, Lind, Wu, Fujimoto, & Goldrath, 2012; Jones & Zhuang, 2007; M. Miyazaki et al., 2017; Wojciechowski et al., 2007). Thirdly, until recently, antibodies available for detection of HEB have not been of high quality, limiting biochemical and chromatin immunoprecipitation studies. However, the finding that HEB is required for proper expression of Trgv4 in fetal γδ T cells raised the question of whether HEB is involved in the regulation of other E2A-dependent TCR elements or whether it might have E2A-independent roles (In et al., 2017). Of particular interest is the question of whether HEB-E2A heterodimers prefer different protein partners from those preferred by E2A-E2A and HEB-HEB homodimers. New reagents and mouse strains for studies of HEB should facilitate rapid progress in this area and provide insights into the non-redundant functions of E2A and HEB in TCR expression and γδ T cell development.

Conclusions

The TCR loci are remarkable for many reasons, including their capability and requirement for genomic rearrangement, their segmental structure, and their ability to drive fate-determining signaling in the thymus as well as initiate activation of peripheral T cells in response to pathogens. These gene loci are also unusual in their sequential modes of regulation, including germline V promoter-mediated transcription, which facilitates accessibility, followed by the movement of a V segment and its promoter close to the enhancer element by way of Rag-mediated recombination. These characteristics are shared in all four TCR loci. However, each locus has its own structural characteristics as well, such as the cluster organization of the TCRγ locus, the integration of the TCRδ locus within the TCRα locus, and the tandemly arrayed segments of the TCRβ locus. Each of these features serves a purpose in accessing and maintaining the αβ or γδ T cell fate choices. While Runx and Myb appear to be the core transcription factors controlling TCRγ and TCRδ expression, they also act in combination with other factors, including E proteins, that segregate their activities onto different cis-regulatory elements. Importantly, E proteins are required to maintain the correct exclusion of Trgv and Trdv expression to the fetal or adult thymus. Further studies will be needed to assess how E proteins are integrated into the larger gene regulatory networks that control TCR expression and how this shapes their impact on T-lineage fate choices.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Johanna Selvaratnam for helpful discussions, and Tracy In and Marsela Braunstein for graphics. Thanks also to my colleagues Juan Carlos Zúñiga-Pflücker, David Wiest, and Cornelis Murre for providing critical insights in TCR signaling and γδ T cell development.

Funding Information

This research was supported by grants to MKA from CIHR (201610PJT), NSERC (RGPIN-2020-05596), and NIH (1P01AI102853-06).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abarrategui I, & Krangel MS (2006). Regulation of T cell receptor-alpha gene recombination by transcription. Nat Immunol, 7(10), 1109–1115. doi: 10.1038/ni1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams EJ, Strop P, Shin S, Chien YH, & Garcia KC (2008). An autonomous CDR3delta is sufficient for recognition of the nonclassical MHC class I molecules T10 and T22 by gammadelta T cells. Nat Immunol, 9(7), 777–784. doi: 10.1038/ni.1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agata Y, Tamaki N, Sakamoto S, Ikawa T, Masuda K, Kawamoto H, & Murre C (2007). Regulation of T cell receptor beta gene rearrangements and allelic exclusion by the helix-loop-helix protein, E47. Immunity, 27(6), 871–884. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo ES, Gottschalk RA, Das J, Egawa T, Hobbs RM, Pandolfi PP, … Sant’Angelo DB (2010). Development of promyelocytic zinc finger and ThPOK-expressing innate gamma delta T cells is controlled by strength of TCR signaling and Id3. J Immunol, 184(3), 1268–1279. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MK, & Selvaratnam JS (2020). Interaction between gammadeltaTCR signaling and the E protein-Id axis in gammadelta T cell development. Immunol Rev, 298(1), 181–197. doi: 10.1111/imr.12924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awong G, & Zuniga-Pflucker JC (2013). Generation, isolation, and engraftment of in vitro-derived human T cell progenitors. Methods Mol Biol, 946, 103–113. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-128-8_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain G, Cravatt CB, Loomans C, Alberola-Ila J, Hedrick SM, & Murre C (2001). Regulation of the helix-loop-helix proteins, E2A and Id3, by the Ras-ERK MAPK cascade. Nat Immunol, 2(2), 165–171. doi: 10.1038/84273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain G, Engel I, Robanus Maandag EC, te Riele HP, Voland JR, Sharp LL, … Murre C (1997). E2A deficiency leads to abnormalities in alphabeta T-cell development and to rapid development of T-cell lymphomas. Mol Cell Biol, 17(8), 4782–4791. doi: 10.1128/MCB.17.8.4782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain G, Quong MW, Soloff RS, Hedrick SM, & Murre C (1999). Thymocyte maturation is regulated by the activity of the helix-loop-helix protein, E47. J Exp Med, 190(11), 1605–1616. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain G, Romanow WJ, Albers K, Havran WL, & Murre C (1999). Positive and negative regulation of V(D)J recombination by the E2A proteins. J Exp Med, 189(2), 289–300. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barndt R, Dai MF, & Zhuang Y (1999). A novel role for HEB downstream or parallel to the pre-TCR signaling pathway during alpha beta thymopoiesis. J Immunol, 163(6), 3331–3343. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10477603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belle I, & Zhuang Y (2014). E proteins in lymphocyte development and lymphoid diseases. Curr Top Dev Biol, 110, 153–187. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405943-6.00004-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom B, Heemskerk MH, Verschuren MC, van Dongen JJ, Stegmann AP, Bakker AQ, … Spits H (1999). Disruption of alpha beta but not of gamma delta T cell development by overexpression of the helix-loop-helix protein Id3 in committed T cell progenitors. EMBO J, 18(10), 2793–2802. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.10.2793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouderlique T, Pena-Perez L, Kharazi S, Hils M, Li X, Krstic A, … Mansson R (2019). The Concerted Action of E2-2 and HEB Is Critical for Early Lymphoid Specification. Front Immunol, 10, 455. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradney C, Hjelmeland M, Komatsu Y, Yoshida M, Yao TP, & Zhuang Y (2003). Regulation of E2A activities by histone acetyltransferases in B lymphocyte development. J Biol Chem, 278(4), 2370–2376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211464200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer PM, Pessach IM, Clarke E, Rowe JH, Ott de Bruin L, Lee YN, … Zuniga-Pflucker JC (2016). Modeling altered T-cell development with induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with RAG1-dependent immune deficiencies. Blood, 128(6), 783–793. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-10-676304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstein M, & Anderson MK (2010). Developmental progression of fetal HEB(−/−) precursors to the pre-T-cell stage is restored by HEBAlt. Eur J Immunol, 40(11), 3173–3182. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buus TB, Geisler C, & Lauritsen JP (2016). The major diversification of Vgamma1.1(+) and Vgamma2(+) thymocytes in mice occurs after commitment to the gammadelta T-cell lineage. Eur J Immunol, 46(10), 2363–2375. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buus TB, Odum N, Geisler C, & Lauritsen JPH (2017). Three distinct developmental pathways for adaptive and two IFN-gamma-producing gammadelta T subsets in adult thymus. Nat Commun, 8(1), 1911. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01963-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone M, Hockett RD Jr., & Zlotnik A (1998). Kinetics of T cell receptor beta, gamma, and delta rearrangements during adult thymic development: T cell receptor rearrangements are present in CD44(+)CD25(+) Pro-T thymocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 95(21), 12522–12527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabana J, Ortigoza E, & Krangel MS (2005). Regulation of the murine Ddelta2 promoter by upstream stimulatory factor 1, Runx1, and c-Myb. J Immunol, 174(7), 4144–4152. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carding SR, & Egan PJ (2002). Gammadelta T cells: functional plasticity and heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol, 2(5), 336–345. doi: 10.1038/nri797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carico Z, & Krangel MS (2015). Chromatin Dynamics and the Development of the TCRalpha and TCRdelta Repertoires. Adv Immunol, 128, 307–361. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JT, Wherry EJ, & Goldrath AW (2014). Molecular regulation of effector and memory T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol, 15(12), 1104–1115. doi: 10.1038/ni.3031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, & Krangel MS (2018). Diversification of the TCR beta Locus Vbeta Repertoire by CTCF. Immunohorizons, 2(11), 377–383. doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.1800072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YS, Chen IB, Pham G, Shao TY, Bangar H, Way SS, & Haslam DB (2020). IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells protect against Clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Invest, 130(5), 2377–2390. doi: 10.1172/JCI127242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien YH, Iwashima M, Wettstein DA, Kaplan KB, Elliott JF, Born W, & Davis MM (1987). T-cell receptor delta gene rearrangements in early thymocytes. Nature, 330(6150), 722–727. doi: 10.1038/330722a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien YH, Zeng X, & Prinz I (2013). The natural and the inducible: interleukin (IL)-17-producing gammadelta T cells. Trends Immunol, 34(4), 151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Cruz LM, Lind KC, Wu BB, Fujimoto JK, & Goldrath AW (2012). Loss of E protein transcription factors E2A and HEB delays memory-precursor formation during the CD8+ T-cell immune response. Eur J Immunol, 42(8), 2031–2041. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis CM, Langelaan DN, Kirlin AC, Chitayat S, Munro K, Spencer HL, … Smith SP (2014). Functional redundancy between the transcriptional activation domains of E2A is mediated by binding to the KIX domain of CBP/p300. Nucleic Acids Res, 42(11), 7370–7382. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marco Barros R, Roberts NA, Dart RJ, Vantourout P, Jandke A, Nussbaumer O, … Hayday A (2016). Epithelia Use Butyrophilin-like Molecules to Shape Organ-Specific gammadelta T Cell Compartments. Cell, 167(1), 203–218 e217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon R, Preston SG, Dascalu S, Flammer PG, Fiddaman SR, McLoughlin K, … Smith AL (2021). Repertoire analysis of gammadelta T cells in the chicken enables functional annotation of the genomic region revealing highly variable pan-tissue TCR gamma V gene usage as well as identifying public and private repertoires. BMC Genomics, 22(1), 719. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-08036-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornburg A, & Yoder JA (2022). On the relationship between extant innate immune receptors and the evolutionary origins of jawed vertebrate adaptive immunity. Immunogenetics. doi: 10.1007/s00251-021-01232-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A, Venkataganesh H, & Love PE (2021). Epigenetic regulation of T cell development. Int Rev Immunol, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/08830185.2021.2022661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A, Zhao B, & Love PE (2021). New insights into TCR beta-selection. Trends Immunol, 42(8), 735–750. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2021.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SC, Sutton CE, Ladell K, Grant EJ, McLaren JE, Roche F, … Mills KHG (2020). A population of proinflammatory T cells coexpresses alphabeta and gammadelta T cell receptors in mice and humans. J Exp Med, 217(5). doi: 10.1084/jem.20190834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott JF, Rock EP, Patten PA, Davis MM, & Chien YH (1988). The adult T-cell receptor delta-chain is diverse and distinct from that of fetal thymocytes. Nature, 331(6157), 627–631. doi: 10.1038/331627a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel I, Johns C, Bain G, Rivera RR, & Murre C (2001). Early thymocyte development is regulated by modulation of E2A protein activity. J Exp Med, 194(6), 733–745. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahl SP, Kappes DJ, & Wiest DL (2018). TCR Signaling Circuits in alphabeta/gammadelta T Lineage Choice. In Soboloff J & Kappes DJ (Eds.), Signaling Mechanisms Regulating T Cell Diversity and Function (pp. 85–104). Boca Raton (FL). [Google Scholar]

- Fisher MR, Rivera-Reyes A, Bloch NB, Schatz DG, & Bassing CH (2017). Immature Lymphocytes Inhibit Rag1 and Rag2 Transcription and V(D)J Recombination in Response to DNA Double-Strand Breaks. J Immunol, 198(7), 2943–2956. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikado N, Mann AO, Bansal K, Romito KR, Ferre EMN, Rosenzweig SD, … Mathis D (2016). Aire Inhibits the Generation of a Perinatal Population of Interleukin-17A-Producing gammadelta T Cells to Promote Immunologic Tolerance. Immunity, 45(5), 999–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garman RD, Doherty PJ, & Raulet DH (1986). Diversity, rearrangement, and expression of murine T cell gamma genes. Cell, 45(5), 733–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90787-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoigne NR, Rybakin V, Acuto O, & Brzostek J (2016). TCR Signal Strength and T Cell Development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, 32, 327–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-111315-125324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentek R, Ghigo C, Hoeffel G, Jorquera A, Msallam R, Wienert S, … Bajenoff M (2018). Epidermal gammadelta T cells originate from yolk sac hematopoiesis and clonally self-renew in the adult. J Exp Med, 215(12), 2994–3005. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber DJ, Azuara V, Levraud JP, Huang SY, Lembezat MP, & Pereira P (1999). IL-4-producing gamma delta T cells that express a very restricted TCR repertoire are preferentially localized in liver and spleen. J Immunol, 163(6), 3076–3082. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10477572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh JK, Romanow WJ, & Murre C (2001). Induction of a diverse T cell receptor gamma/delta repertoire by the helix-loop-helix proteins E2A and HEB in nonlymphoid cells. J Exp Med, 193(6), 769–776. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladdy RA, Taylor MD, Williams CJ, Grandal I, Karaskova J, Squire JA, … Danska JS (2003). The RAG-1/2 endonuclease causes genomic instability and controls CNS complications of lymphoblastic leukemia in p53/Prkdc-deficient mice. Cancer Cell, 3(1), 37–50. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00236-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DI, Kennedy J, Suda T, & Zlotnik A (1993). A developmental pathway involving four phenotypically and functionally distinct subsets of CD3-CD4-CD8- triple-negative adult mouse thymocytes defined by CD44 and CD25 expression. J Immunol, 150(10), 4244–4252. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8387091 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriadou K, Boucontet L, & Pereira P (2003). Most IL-4-producing gamma delta thymocytes of adult mice originate from fetal precursors. J Immunol, 171(5), 2413–2420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gully BS, Rossjohn J, & Davey MS (2021). Our evolving understanding of the role of the gammadelta T cell receptor in gammadelta T cell mediated immunity. Biochem Soc Trans, 49(5), 1985–1995. doi: 10.1042/BST20200890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haks MC, Lefebvre JM, Lauritsen JP, Carleton M, Rhodes M, Miyazaki T, … Wiest DL (2005). Attenuation of gammadeltaTCR signaling efficiently diverts thymocytes to the alphabeta lineage. Immunity, 22(5), 595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao B, & Krangel MS (2011). Long-distance regulation of fetal V(delta) gene segment TRDV4 by the Tcrd enhancer. J Immunol, 187(5), 2484–2491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havran WL, & Allison JP (1988). Developmentally ordered appearance of thymocytes expressing different T-cell antigen receptors. Nature, 335(6189), 443–445. doi: 10.1038/335443a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havran WL, & Allison JP (1990). Origin of Thy-1+ dendritic epidermal cells of adult mice from fetal thymic precursors. Nature, 344(6261), 68–70. doi: 10.1038/344068a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SM, Li L, & Love PE (2005). TCR signal strength influences alphabeta/gammadelta lineage fate. Immunity, 22(5), 583–593. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig JS, & Tonegawa S (1986). Diversity of murine gamma genes and expression in fetal and adult T lymphocytes. Nature, 322(6082), 836–840. doi: 10.1038/322836a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Munain C (2015). Recent insights into the transcriptional control of the Tcra/Tcrd locus by distant enhancers during the development of T-lymphocytes. Transcription, 6(4), 65–73. doi: 10.1080/21541264.2015.1078429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Munain C, Sleckman BP, & Krangel MS (1999). A developmental switch from TCR delta enhancer to TCR alpha enhancer function during thymocyte maturation. Immunity, 10(6), 723–733. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80071-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt MR, Reuter MS, Wei W, Tayebi N, Liu J, Sharmin S, … Ellis J (2019). Precision Health Resource of Control iPSC Lines for Versatile Multilineage Differentiation. Stem Cell Reports, 13(6), 1126–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa H, & Rothenberg EV (2021). How transcription factors drive choice of the T cell fate. Nat Rev Immunol, 21(3), 162–176. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00426-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovav AH, Wilharm A, Barel O, & Prinz I (2020). Development and Function of gammadeltaT Cells in the Oral Mucosa. J Dent Res, 99(5), 498–505. doi: 10.1177/0022034520908839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, & Sleckman BP (2007). Developmental stage-specific regulation of TCR-alpha-chain gene assembly by intrinsic features of the TEA promoter. J Immunol, 179(1), 449–454. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Goldrath AW, & Murre C (2006). E proteins and Notch signaling cooperate to promote T cell lineage specification and commitment. J Exp Med, 203(5), 1329–1342. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In TSH, Trotman-Grant A, Fahl S, Chen ELY, Zarin P, Moore AJ, … Anderson MK (2017). HEB is required for the specification of fetal IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells. Nat Commun, 8(1), 2004. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02225-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itohara S, Farr AG, Lafaille JJ, Bonneville M, Takagaki Y, Haas W, & Tonegawa S (1990). Homing of a gamma delta thymocyte subset with homogeneous T-cell receptors to mucosal epithelia. Nature, 343(6260), 754–757. doi: 10.1038/343754a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J, Dai M, & Zhuang Y (2008). E proteins are required to activate germline transcription of the TCR Vbeta8.2 gene. Eur J Immunol, 38(10), 2806–2820. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Chang FC, Ross AE, Lee J, Nakayama K, Nakayama K, & Desiderio S (2005). Ubiquitylation of RAG-2 by Skp2-SCF links destruction of the V(D)J recombinase to the cell cycle. Mol Cell, 18(6), 699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones ME, & Zhuang Y (2007). Acquisition of a functional T cell receptor during T lymphocyte development is enforced by HEB and E2A transcription factors. Immunity, 27(6), 860–870. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones ME, & Zhuang Y (2011). Stage-specific functions of E-proteins at the beta-selection and T-cell receptor checkpoints during thymocyte development. Immunol Res, 49(1-3), 202–215. doi: 10.1007/s12026-010-8182-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Baker J, & Raulet DH (1995). Evidence that productive rearrangements of TCR gamma genes influence the commitment of progenitor cells to differentiate into alpha beta or gamma delta T cells. Eur J Immunol, 25(9), 2706–2709. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, & Raulet DH (1997). Events that regulate differentiation of alpha beta TCR+ and gamma delta TCR+ T cells from a common precursor. Semin Immunol, 9(3), 171–179. doi: 10.1006/smim.1997.0069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashani E, Fohse L, Raha S, Sandrock I, Oberdorfer L, Koenecke C, … Prinz I (2015). A clonotypic Vgamma4Jgamma1/Vdelta5Ddelta2Jdelta1 innate gammadelta T-cell population restricted to the CCR6(+)CD27(−) subset. Nat Commun, 6, 6477. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee BL (2009). E and ID proteins branch out. Nat Rev Immunol, 9(3), 175–184. doi: 10.1038/nri2507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko LJ, Yamamoto M, Leonard MW, George KM, Ting P, & Engel JD (1991). Murine and human T-lymphocyte GATA-3 factors mediate transcription through a cis-regulatory element within the human T-cell receptor delta gene enhancer. Mol Cell Biol, 11(5), 2778–2784. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.5.2778-2784.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koop BF, & Hood L (1994). Striking sequence similarity over almost 100 kilobases of human and mouse T-cell receptor DNA. Nat Genet, 7(1), 48–53. doi: 10.1038/ng0594-48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreslavsky T, Savage AK, Hobbs R, Gounari F, Bronson R, Pereira P, … von Boehmer H (2009). TCR-inducible PLZF transcription factor required for innate phenotype of a subset of gammadelta T cells with restricted TCR diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 106(30), 12453–12458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903895106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RM, Laky K, & Hayes SM (2010). Unexpected role for the B cell-specific Src family kinase B lymphoid kinase in the development of IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells. J Immunol, 185(11), 6518–6527. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langerak AW, Wolvers-Tettero IL, van Gastel-Mol EJ, Oud ME, & van Dongen JJ (2001). Basic helix-loop-helix proteins E2A and HEB induce immature T-cell receptor rearrangements in nonlymphoid cells. Blood, 98(8), 2456–2465. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JP, Wong GW, Lee SY, Lefebvre JM, Ciofani M, Rhodes M, … Wiest DL (2009). Marked induction of the helix-loop-helix protein Id3 promotes the gammadelta T cell fate and renders their functional maturation Notch independent. Immunity, 31(4), 565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Coffey F, Fahl SP, Peri S, Rhodes M, Cai KQ, … Wiest DL (2014). Noncanonical mode of ERK action controls alternative alphabeta and gammadelta T cell lineage fates. Immunity, 41(6), 934–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Stadanlick J, Kappes DJ, & Wiest DL (2010). Towards a molecular understanding of the differential signals regulating alphabeta/gammadelta T lineage choice. Semin Immunol, 22(4), 237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2010.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YN, Alt FW, Reyes J, Gleason M, Zarrin AA, & Jung D (2009). Differential utilization of T cell receptor TCR alpha/TCR delta locus variable region gene segments is mediated by accessibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 106(41), 17487–17492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909723106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Brauer PM, Singh J, Xhiku S, Yoganathan K, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, & Anderson MK (2017). Targeted Disruption of TCF12 Reveals HEB as Essential in Human Mesodermal Specification and Hematopoiesis. Stem Cell Reports, 9(3), 779–795. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak F, Tourigny M, Schatz DG, & Petrie HT (1999). Characterization of TCR gene rearrangements during adult murine T cell development. J Immunol, 162(5), 2575–2580. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10072498 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder K, Rupp LJ, Yang-Iott KS, Koues OI, Kyle KE, Bassing CH, & Oltz EM (2015). Domain-Specific and Stage-Intrinsic Changes in Tcrb Conformation during Thymocyte Development. J Immunol, 195(3), 1262–1272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis D, Yassai M, Hletko A, McOlash L, & Gorski J (1997). Concurrent or sequential delta and beta TCR gene rearrangement during thymocyte development: individual thymi follow distinct pathways. J Immunol, 159(2), 529–533. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9218565 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui N, Tani-ichi S, Maki K, & Ikuta K (2008). Transcriptional activation of mouse TCR Jgamma4 germline promoter by STAT5. Mol Immunol, 45(3), 849–855. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.06.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan RE, & Sikes ML (2009). Promoter activity 5’ of Dbeta2 is coordinated by E47, Runx1, and GATA-3. Mol Immunol, 46(15), 3009–3017. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie AM, & Zuniga-Pflucker JC (2002). Regulation of thymocyte differentiation: pre-TCR signals and beta-selection. Semin Immunol, 14(5), 311–323. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12220932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulak J, Oriolo F, Bruni E, Roberto A, Colombo FS, Villa A, … Mavilio D (2019). NKp46-expressing human gut-resident intraepithelial Vdelta1 T cell subpopulation exhibits high antitumor activity against colorectal cancer. JCI Insight, 4(24). doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.125884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki K, & Miyazaki M (2021). The Interplay Between Chromatin Architecture and Lineage-Specific Transcription Factors and the Regulation of Rag Gene Expression. Front Immunol, 12, 659761. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.659761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki K, Watanabe H, Yoshikawa G, Chen K, Hidaka R, Aitani Y, … Miyazaki M (2020). The transcription factor E2A activates multiple enhancers that drive Rag expression in developing T and B cells. Sci Immunol, 5(51). doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abb1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki M, Miyazaki K, Chen K, Jin Y, Turner J, Moore AJ, … Murre C (2017). The E-Id Protein Axis Specifies Adaptive Lymphoid Cell Identity and Suppresses Thymic Innate Lymphoid Cell Development. Immunity, 46(5), 818–834 e814. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki M, Rivera RR, Miyazaki K, Lin YC, Agata Y, & Murre C (2011). The opposing roles of the transcription factor E2A and its antagonist Id3 that orchestrate and enforce the naive fate of T cells. Nat Immunol, 12(10), 992–1001. doi: 10.1038/ni.2086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monin L, Ushakov DS, Arnesen H, Bah N, Jandke A, Munoz-Ruiz M, … Hayday A (2020). gammadelta T cells compose a developmentally regulated intrauterine population and protect against vaginal candidiasis. Mucosal Immunol. doi: 10.1038/s41385-020-0305-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muro R, Nitta T, Nakano K, Okamura T, Takayanagi H, & Suzuki H (2018). gammadeltaTCR recruits the Syk/PI3K axis to drive proinflammatory differentiation program. J Clin Invest, 128(1), 415–426. doi: 10.1172/JCI95837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murre C (2019). Helix-loop-helix proteins and the advent of cellular diversity: 30 years of discovery. Genes Dev, 33(1-2), 6–25. doi: 10.1101/gad.320663.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muschaweckh A, Petermann F, & Korn T (2017). IL-1beta and IL-23 Promote Extrathymic Commitment of CD27(+)CD122(−) gammadelta T Cells to gammadeltaT17 Cells. J Immunol, 199(8), 2668–2679. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik AK, Byrd AT, Lucander ACK, & Krangel MS (2019). Hierarchical assembly and disassembly of a transcriptionally active RAG locus in CD4(+)CD8(+) thymocytes. J Exp Med, 216(1), 231–243. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik AK, Hawwari A, & Krangel MS (2015). Specification of Vdelta and Valpha usage by Tcra/Tcrd locus V gene segment promoters. J Immunol, 194(2), 790–794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan K, Sylvia KE, Malhotra N, Yin CC, Martens G, Vallerskog T, … Immunological Genome Project, C. (2012). Intrathymic programming of effector fates in three molecularly distinct gammadelta T cell subtypes. Nat Immunol, 13(5), 511–518. doi: 10.1038/ni.2247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MM, Witherden DA, & Havran WL (2017). gammadelta T cells in homeostasis and host defence of epithelial barrier tissues. Nat Rev Immunol, 17(12), 733–745. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki M, Wakae K, Tamaki N, Sakamoto S, Ohnishi K, Uejima T, … Agata Y (2011). Regulation of TCR Vgamma2 gene rearrangement by the helix-loop-helix protein, E2A. Int Immunol, 23(5), 297–305. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou M, Sanchez Sanchez G, & Vermijlen D (2020). Innate and adaptive gammadelta T cells: How, when, and why. Immunol Rev, 298(1), 99–116. doi: 10.1111/imr.12926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papotto PH, Reinhardt A, Prinz I, & Silva-Santos B (2018). Innately versatile: gammadelta17 T cells in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun, 87, 26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papotto PH, Yilmaz B, & Silva-Santos B (2021). Crosstalk between gammadelta T cells and the microbiota. Nat Microbiol, 6(9), 1110–1117. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00948-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JE, Botting RA, Dominguez Conde C, Popescu DM, Lavaert M, Kunz DJ, … Teichmann SA (2020). A cell atlas of human thymic development defines T cell repertoire formation. Science, 367(6480). doi: 10.1126/science.aay3224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]