Abstract

Background:

An emergency department (ED) visit provides a unique opportunity to identify elder abuse and initiate intervention, but emergency providers rarely do. To address this, we developed the Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT), an ED-based interdisciplinary consultation service. We describe our initial experience in the first two years after program launch.

Methods:

We launched VEPT in a large, urban, academic ED/hospital. From 4/3/17-4/2/19, we tracked VEPT activations, including patient characteristics, assessment, and interventions. We compared VEPT activations to frequency of elder abuse identification in the ED before VEPT launch. We examined outcomes for patients evaluated by VEPT, including change in living situation at discharge. We assessed ED providers’ experiences with VEPT via written surveys and focus groups.

Results:

During the program’s initial two years, VEPT was activated and provided consultation/care to 200 ED patients. Cases included physical abuse (59%), neglect (56%), financial exploitation (32%), verbal/emotional/psychological abuse (25%), and sexual abuse (2%). Sixty-two percent of patients assessed were determined by VEPT to have high or moderate suspicion for elder abuse. Seventy-five percent of these patients had a change in living/housing situation or were discharged with new or additional home services, with 14% discharged to an elder abuse shelter, 39% to a different living/housing situation, and 22% with new or additional home services. ED providers reported that VEPT made them more likely to consider / assess for elder abuse and recognized the value of the expertise and guidance VEPT provided. Ninety-four percent reported believing that there is merit in establishing a VEPT Program in other EDs.

Conclusion:

VEPT was frequently activated and many patients were discharged with changes in living situation and/or additional home services, which may improve safety. Future research is needed to examine longer-term outcomes.

Keywords: elder abuse, emergency department, intervention

INTRODUCTION

Elder abuse (EA) is defined as action or negligence against an older adult that causes harm or risk of harm committed by a person in a relationship with an expectation of trust and includes physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, psychological abuse, and financial exploitation. EA is common, affecting 5-15% of community-dwelling older adults each year1–4 and more than 20% of long-term care residents.5–9 Older adults who experience EA are at higher risk of mortality,3,10,11 depression12 and nursing home placement.13,14 Unfortunately, as few as 1 in 24 cases are identified and reported to appropriate authorities.1 As a result, increasing identification and intervention for EA is a public health priority.15–18

An emergency department (ED) visit for acute injury or illness represents an important potential opportunity to identify EA and initiate interventions, as it may be the only time an isolated older adult leaves their home.19,20 Unfortunately, ED providers rarely recognize or report EA20–22 and don’t have protocols to guide intervention.23 Interdisciplinary ED/hospital-based child protection teams were developed more than 50 years ago to improve care for potential child abuse victims.24,25 Members of these interdisciplinary teams, which now exist in many large US hospitals, use their expertise and work together to optimally coordinate complex acute interventions needed for a maltreated child, often including forensic evaluation and contact with appropriate authorities. Also, availability of a child protection team to respond has been shown to increase identification of child abuse by ED providers.26 In addition to increasing awareness among ED providers, the presence of an expert child abuse response team to handover the challenging, time-consuming next steps of evaluation and intervention may decrease disincentives to raising concerns for child abuse during a busy clinical shift. We hypothesize that similar benefits may be achieved for older adults potentially experiencing EA through a similar type of program.

Modeled on the successful experience of child protection teams, we developed and launched the Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT),23,27 a first-of-its-kind ED-based multidisciplinary consultation service for older adults experiencing EA. Here, we describe our initial experience during the first two years after launch.

METHODS

Description of the Intervention

We have described VEPT and its development in detail elsewhere.23,27 VEPT is an interdisciplinary ED-based consultation service available 24/7 to assess, treat, and ensure the safety of older adults experiencing EA while also collecting forensic evidence when appropriate and working closely with the authorities. ED providers activate VEPT via page when EA concerns arise for an older adult patient. The on-call VEPT provider (emergency physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants who have additional geriatrics and forensics training and who share on-call responsibilities) responds to the page and discusses the case with the ED team. The VEPT provider elicits information about the older adult patient and the case dynamics and may come into the ED to perform a face-to-face assessment. This assessment may include a forensic evaluation, with comprehensive documentation and photographs. VEPT also includes social workers who have specialized expertise in elder abuse. These VEPT Social Workers: (1) provide supportive counseling to victims, (2) obtain collateral from and work with family members, caregivers, primary care physicians, and other concerned persons, (3) involve law enforcement and Adult Protective Services (APS) as appropriate, (4) coordinate with the primary ED team and hospital resources, (5) identify which community-based services may be appropriate to offer the victim, and (6) collaborate with community-based agencies. Other hospital resources, including ED Psychiatry, ED Radiology, Patient Services, Security, Legal, and Ethics may also be involved when necessary. The VEPT team gives recommendations to the primary ED care team, including additional testing, strategies to ensure safety, available resources, and appropriate disposition. Detailed protocols are available as Supplementary Figure S1, and more information is available at: http://vept.med.cornell.edu. Neither the older adult nor their insurance is billed for the VEPT program’s involvement in their care.

We developed an algorithmic approach to standardize the determination of the level of suspicion for each case (high, moderate, or low) for each type of EA (physical abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, verbal/emotional/psychological abuse, and financial exploitation) that incorporates established risk factors with history, physical findings, test results, and collateral information. For overall level of suspicion for a case, we used the highest level for any individual type of EA. During the initial 6 months, to ensure standardization, all VEPT members met regularly to review and discuss the level of suspicion assessment for each case. Through this process, consensus was developed that was applied to future case investigations.

VEPT was launched on April 3, 2017, after training more than 400 ED and hospital providers on EA identification and working with VEPT, including in-person presentations to attending and resident physicians, advanced practice providers, ED/hospital social workers, and Emergency Medical Services. We presented at Social Work Grand Rounds and an Ethics Committee meeting. VEPT also developed an online module for ED nurses and administrators.

In addition to the cases identified within the ED, we partnered with APS to enable them to activate VEPT if, during a home visit, they became concerned about a client’s immediate safety or deemed an emergent medical / forensic examination necessary. In these cases, APS called a dedicated telephone number, deploying police and an ambulance to transport the older adult and the concerned professional to our ED for VEPT evaluation.

Though we initially intended to consult only in the ED, it became common for in-patient teams to request our team’s assistance after admission. To respond to this, we expanded our VEPT program to respond to consults from in-patient teams throughout the hospital. These consults are not included in the cases we report here.

Setting

The hospital where this intervention was deployed is a large, urban, academic medical center that treats over 90,000 patients each year, of whom more than 30% are ≥ 60 years old. Though not yet accredited as a Geriatrics ED, our ED focuses on innovation to optimize geriatric care for older adults, including geriatric emergency medicine (GEM) protocols and a GEM fellowship training program. The hospital is a Level I trauma center, a regional burn center, and it has a designated inpatient unit for the Acute Care of the Elderly.

Funding

The design of the VEPT program was funded by a Change AGEnts grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the program was initially funded by the Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation. The program is currently funded by the New York State Office of Victim Services. During the period reported here, costs associated with VEPT included personnel: a full-time social worker and compensation for effort from 3 emergency physicians and 1 advanced practice provider who shared on-call responsibilities as VEPT providers.

Describing Initial VEPT Experience

We used a standardized protocol to comprehensively track detailed information for each VEPT activation from 4/3/17-4/2/19 in a custom-designed registry using REDCap (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN). We examined the presenting complaint for each case, categorizing them using the Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) Presenting Complaint List version 1.1,28 which we modified to add options relevant for older adults. We considered a presenting complaint EA-related if concern for abuse, neglect, or exploitation was explicitly reported at the beginning of the ED visit by the older adult or someone else as the reason for presentation. We captured which member(s) of the ED team activated VEPT and developed 13 categories of activation reason, including patient reporting EA, unusual or unexplained injury, and family member / caregiver exhibiting concerning behavior. We captured the demographic characteristics of the older adult, their relationship to the person suspected of mistreatment, and circumstances surrounding the potential EA.

We closely evaluated the VEPT assessment, including history, collateral obtained, and physical findings. We also looked at the VEPT assessment of the level of suspicion for each type of EA as well as the overall level of suspicion. Additionally, we examined the recommendations VEPT made, including additional laboratory tests, imaging, and disposition.

For cases with high or moderate suspicion for ongoing EA after VEPT evaluation, we examined the interventions VEPT performed, including involvement of other hospital-based resources as well as reporting to APS, the police, and other community-based services. Notably, in New York State, APS only accepts referrals for older adults who are being discharged to the community rather than a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation and has criteria for involvement including that the older adult: (1) is physically or mentally impaired, (2) due to these impairments, is unable to manage their own resources, carry out the activities of daily living, or protect themselves from abuse, neglect, exploitation, or other hazardous situations without assistance from others, and (3) has no one available who is willing and able to assist them responsibly. Also, in New York, unlike nearly all US states, health care providers are not mandated reporters of elder abuse.

Evaluation Model

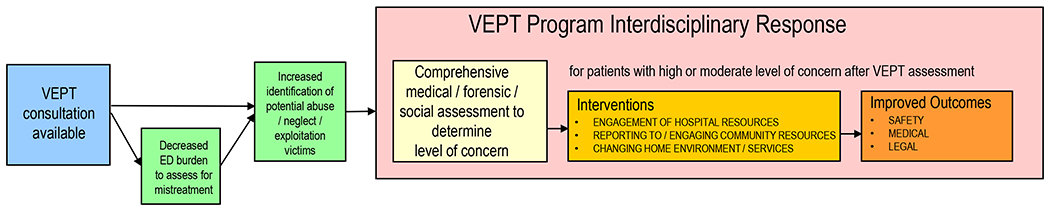

Figure 1 shows the evaluation model that has guided our quantitative and qualitative program evaluation strategy. We hypothesized that the availability of VEPT would increase the identification of potential victims and also decrease the burden on ED providers associated with these complex cases, which would further increase identification by reducing perceived barriers in considering the diagnosis. In addition, we hypothesized that, after VEPT activation, the multidisciplinary team’s comprehensive medical / forensic / social assessment would reliably determine the level of suspicion for EA. For patients with high or moderate level of suspicion after VEPT assessment, the team would initiate interventions including engaging hospital resources from multiple disciplines, reporting to APS and law enforcement, connecting with community resources, and facilitating changes to the home environment. Ultimately, we anticipated that VEPT involvement would lead to improved safety and medical outcomes.

Figure 1:

Evaluation Model for Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) Program

Quantitative Evaluation

To quantitatively evaluate VEPT, we compared the number of VEPT activations to potential EA cases identified in our ED during the 5 years before VEPT was launched (4/3/2012–4/2/2017). Our electronic medical record documentation includes the opportunity to formally register concern for elder abuse/intimate partner violence during the initial ED nursing assessment at triage. We found cases from the 5-year period prior to VEPT in patients aged ≥60 in which concern for EA was identified during this initial screen. During this period, we also identified ED visits or hospitalizations that were assigned International Classification of Diseases, 9th or 10th Revision (ICD-9/10) diagnosis code(s) consistent with EA. In these cases, we reviewed documentation from the evaluation, including from social work and nursing, to assess whether EA was considered.

For older adults evaluated by VEPT, we evaluated change in living/housing situation on discharge, and return to ED within 6 months for an EA-related issue.

We administered written surveys to 81 ED attending physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurses one year after launch (in April–June, 2018) to assess their perception of the program (Supplementary Text S1).

Quantitative analyses were conducted using Stata v16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Results are presented as frequencies with proportions and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR).

Qualitative Evaluation

We conducted 4 focus groups with participants from multiple disciplines (ED nurse practitioners and physician assistants, ED social workers, inpatient social workers, and geriatricians) during July–October 2018 to explore provider perspectives on the VEPT. We chose focus groups rather than interviews because this approach unearths the spectrum of participant experiences and feelings and elicits further reflection on one’s own perspective in the context of other convergent and divergent views in the group. We developed a semi-structured topic guide informed by our previous related research experience.23 (Final version included as Supplementary Text S2). We included 32 participants because we believed that we reached saturation. Focus groups were recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were initially analyzed and coded by two authors (TR, AE) using content analysis,29 and findings were discussed with the entire investigative team to develop consensus on major themes. We used the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research30 and our previous research23 to guide collection and analysis.

Research Ethics Approval

This research was approved by the Weill Cornell Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Description of VEPT Activations

During the initial two years of the program, VEPT was activated 200 times in the ED (88 times during Year 1 (4/3/17-4/2/18) and 112 times during Year 2 (4/3/18-4/2/19)). Table 1 shows the level of suspicion for EA after VEPT evaluation for different types of abuse. Table 2 shows the characteristics of all ED patients for whom VEPT was activated as well as for patients for whom suspicion was high or moderate after VEPT evaluation. Additional aspects of VEPT activation and initial evaluation are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Table 3 shows the ED disposition and VEPT program-facilitated interventions for patients with high/moderate suspicion for EA.

Table 1:

Types of Possible Elder Abuse among Patients for whom Vulnerable Elder Protection Team was Activated (n=200), 4/3/2017-4/2/2019

| High Suspicion after Evaluation (n=76) | Moderate Suspicion after Evaluation (n=46) | Low Suspicion after Evaluation (n=78) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| % | % | % | |

|

|

|||

| Overall / Any | 38 | 23 | 39 |

| Physical Abuse | 22 | 11 | 27 |

| Neglect | 16 | 18 | 23 |

| Financial Exploitation | 14 | 10 | 9 |

| Verbal / Psychological / Emotional Abuse | 13 | 7 | 5 |

| Sexual Abuse | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Table 2:

Characteristics of Emergency Department Patients for whom Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) was Activated and Aspects of VEPT Initial Evaluation (n=200), 4/3/2017-4/2/2019

| All Activations (n=200) | High / Moderate Suspicion after Evaluation (n=122) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| % | % | |

|

|

||

| Reason for Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) activation | ||

| Patient reporting elder abuse | 34 | 38 |

| Unusual or unexplained injury(ies) | 27 | 20 |

| Community-based professional reports abuse | 20 | 30 |

| Family member/paid caregiver/concerned other reports abuse | 15 | 19 |

| Report of unsafe home environment due to clutter, no food, utilities off, other hazards | 14 | 18 |

| Delay in seeking medical care | 13 | 11 |

| Patient appears unkempt /emaciated, poor wound care | 10 | 11 |

| Family member /caregiver exhibiting concerning behavior | 8 | 8 |

| Report patient is facing eviction or in rental arrears | 5 | 7 |

| Vulnerable Elder Protection Team consulted in past | 4 | 6 |

| Older adult with dementia left unattended /wandering / found confused in public place | 3 | 2 |

| Patient not being given / taking medications appropriately | 2 | 2 |

| No safe home environment for discharge | 2 | 2 |

| Caregiver hospitalized, so inadequate care at home | 2 | 1 |

| Multiple reasons | 43 | 54 |

| Age (median, IQR) | 81, 72 – 89 | 80, 72– 86 |

| Female | 79 | 79 |

| Arrived via Emergency Medical Services | 76 | 78 |

| ≥3 Chronic Medical Conditions | 55 | 50 |

| Dementia / Cognitive Impairment | 66 | 63 |

| Requires Assistance with any Activities of Daily Living | 72 | 75 |

| ≥4 Visits to ED in Previous 12 months | 8 | 9 |

| Presenting complaint | ||

| Elder abuse-related | 34 | 47 |

| Not elder abuse-related | ||

| Trauma (including fall) | 15 | 9 |

| Cardiovascular | 11 | 11 |

| Neurologic (including confusion) | 11 | 9 |

| Orthopedic | 9 | 5 |

| Mental health/psychological issue | 7 | 6 |

| Skin | 6 | 4 |

| General & minor | 4 | 3 |

| Other* | 3 | 6 |

| Source(s) of VEPT Activation | ||

| ED medical provider | 49 | 39 |

| ED social worker | 39 | 35 |

| Other ED team member | 5 | 7 |

| Adult Protective Services | 8 | 11 |

| Jewish Association for Services for the Aged | 6 | 9 |

| Other community agency | 5 | 7 |

| Other** | 4 | 4 |

| Potential Perpetrator | ||

| Adult Child | 38 | 36 |

| Spouse/Partner/Companion | 18 | 21 |

| Home health aide | 18 | 12 |

| Nursing home staff | 8 | 6 |

| Other family | 16 | 18 |

| Other non-family | 10 | 8 |

| Multiple Perpetrators | 17 | 17 |

| Older adult’s living situation | ||

| Community-Dwelling with Potential Perpetrator | 57 | 70 |

| Community Dwelling – Other | 35 | 23 |

| Nursing Home / Group Home | 9 | 7 |

| Potential Perpetrator Patient’s Primary Caregiver | 56 | 51 |

| Potential Perpetrator Patient’s Health Care Decision-Maker | 28 | 23 |

| Health Care Proxy | 17 | 11 |

| Health Care Surrogate | 11 | 12 |

| Potential Perpetrator Present in ED | 36 | 28 |

Other not elder abuse-related presenting complaints include: Genitourinary, Respiratory, ENT – mouth, throat, neck, Gastrointestinal, Ophthalmology

Other sources of VEPT activation include: New York City Elder Abuse Center, Community-Based Elder Abuse Multi-Disciplinary Teams, New York Police Department

Table 3:

Interventions / Outcomes for Patients Identified as Likely Victims of Elder Abuse after Comprehensive Vulnerable Elder Protection Team Evaluation (n=122), 4/3/2017-4/2/2019

| High / Moderate Suspicion after Evaluation | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| % | |

|

|

|

| Admitted to hospital | 84 |

| Additional medical issue requiring admission | 45 |

| Primarily for safety | 38 |

| VEPT assistance to in-patient social work/team | 78 |

| Collaboration with ED / hospital services / resources | |

| Geriatrics in-patient consultation | 64 |

| Victim Intervention Program social work team* involved | 43 |

| Ethics Committee involved | 4 |

| Sexual Assault Forensic Examination performed | 2 |

| Reporting to other investigative authorities | |

| Reported to Adult Protective Services (new report or confirmation of active open case, among n=73 discharged to the community) | 67 |

| Reported to police | 11 |

| Facility-related complaint filed with Department of Health | 3 |

| New York City Elder Abuse Center (NYCEAC) involved | 12 |

| Case subsequently presented to NYCEAC Multi-Disciplinary Team | 3 |

| Length of hospitalization (median, IQR) | 8, 5 – 15 |

| After medical clearance for patients initially admitted for medical issue (median, IQR) | 6, 4 – 13 |

| For patients admitted primarily for safety (median, IQR) | 10.5, 6 – 26 |

| Change in living / housing situation on discharge | 52 |

| Elder abuse / domestic violence shelter | 14 |

| Subacute rehab/nursing home placement | 24 |

| Alternative living situation in community | 12 |

| Change to new / different nursing home | 3 |

| New / additional home services on discharge | 27 |

| Home services initiated | 8 |

| New home services added | 15 |

| Existing home services expanded | 3 |

| Home services changed to replace potential abuser | 1 |

| Returned to ED within 6 months | |

| For elder abuse-related issue | 4 |

| For any issue | 25 |

Program in our hospital funded by the New York State Office of Victim Services that provides support and follow-up counseling for victims of crime, with a focus on sexual assault victims.

Quantitative Evaluation

Comparison to Elder Abuse Identification Prior to VEPT Launch

In the 5 years prior to VEPT launch, EA was identified in the ED a mean of 10 times each year (median: 11, IQR: 7-14, range: 6-15). Concern was noted during the initial nursing assessment at triage in 58% of these, and 52% had an ICD diagnosis of EA from the ED. Among all cases, 62% had suspicion for physical abuse, 37% neglect, 27% verbal/emotional/psychological abuse, 25% financial exploitation, and 2% sexual abuse.

Outcomes for VEPT Patients

Among patients with high/moderate suspicion for EA, VEPT activation led to a majority receiving safety interventions (Table 3). Overall, 75% had a change in their living / housing situation or were discharged with new or additional home services, with 14% discharged to an elder abuse shelter, 39% to another different living / housing situation, and 27% with new or additional home services. In comparison to EA cases identified in the 5 years prior to VEPT launch, fewer VEPT patients returned to the ED for an EA-related issue within 6 months after discharge (4% vs. 8%) or for any reason (25% vs. 28%). Very few patients (4%) returned to the ED for an EA-related issue within 6 months after discharge, with 25% returning for any reason. This differed from before our program, with 8% returning for an EA-related issue and 28% returning for any reason.

Provider Perspectives on VEPT

Among survey respondents, 84% reported that VEPT introduction training increased their confidence in assessing for EA, 83% reported VEPT’s existence increased the frequency with which they considered / assessed for EA, 38% reported using VEPT frequently, and 94% believed there was merit in establishing a VEPT program in other EDs.

Qualitative Evaluation

Themes from provider focus groups are shown in Table 4 and representative quotations from each in Supplementary Table S2. A major theme emerged that ED providers believed that VEPT made them more likely to consider EA. One common reason was that becoming engaged represented less additional work for them than it would have in the past.

Table 4:

Themes from Focus Groups of Emergency Department and Hospital Providers about VEPT Program after One Year of Operation

| Theme |

|---|

| Presence of VEPT makes ED providers more likely to consider elder abuse at least partially because doing so represents less additional work for them than it would have previously |

| Expertise and guidance from a consult service valuable to provide appropriate assessment and care to complex patients while avoiding prolonged ED stays |

| VEPT social worker reduces the burden on ED social workers by leading the social assessment and management of these complex, time-consuming cases during busy shifts. |

| VEPT consultation and input helps justify hospital admission for safety and reduces resistance from admitting team to plan. |

| VEPT involvement may reduce the length of hospitalization by completely assessing the social situation and addressing potential barriers to hospital discharge that might otherwise take several days to uncover. |

| VEPT team may ensure that Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy referrals for patients requiring admission are initiated in the ED, reducing the length of hospitalization, as the completion of these assessments is critical for hospital discharge and helps determine appropriate post-hospital disposition. |

| VEPT team, given their expertise and familiarity with available resources, may contact and regularly update family members, reducing the burden on and providing support to in-patient teams. |

| That the VEPT team is comprised of physicians and advanced practice providers who also work in the ED makes ED providers more comfortable activating and working with the team. |

| Inclusion of physicians as members of VEPT important to ensure that recommendations are considered seriously implemented by inpatient medical teams. |

| VEPT team participating in multi-disciplinary rounds on the first day after a patient is hospitalized may ensure that all inpatient staff are aware of the plan including next steps and reduce any anxiety about appropriate management. |

| Emphasizing the low threshold to consult VEPT and that any member of the ED team may do so is important to overcome reluctance of some to activate or concerns about appropriateness of cases for the team. |

| More education at regular interval on the VEPT program and clinical observations that should trigger activation and consideration of potential elder abuse would be helpful. |

ED Advanced Practice Provider #2: I think…I’m more likely to address it. Like a borderline case…if you are like not sure…whether you want to get involved, because it’s a lot of work. Like if there is a little bit of sneaky suspicion…I’m very easy to pull the trigger on [VEPT]…You guys can do it more successfully.

Another major theme was providers’ recognition of the value of expertise and guidance from a consult service. They believed the VEPT social worker reduced the burden on ED social workers by managing these cases. Providers felt that VEPT consultation and input helped justify hospital admission for safety and that VEPT involvement may reduce the length of hospitalization by completely assessing the social situation and addressing early potential barriers to hospital discharge.

DISCUSSION

This study represents, to our knowledge, the first evaluation of an ED-based interdisciplinary consultation service for older adults experiencing EA.

After the launch of VEPT, potential cases of EA identified in our ED increased almost tenfold, from <1 to nearly 8 each month. That our program was frequently activated suggests that VEPT was providing an important service for vulnerable patients that was useful to ED providers. Notably, we did not have in place a protocol for formal universal EA screening31 at triage (beyond opportunity to register concern within the chart) or by bedside nurses. Thus, our study demonstrates that training and an available response team can significantly increase EA identification even without screening. Cases identified included all types of EA, including financial exploitation and sexual abuse. Many victims were suffering from multiple types of EA concurrently, which is common and has been previously reported.3

In most cases, the patient’s presenting complaint was not EA-related. This underscores that ED teams focused only on addressing the potential medical causes of a patient’s chief complaint may miss concurrent EA without a high index of suspicion. Other than reports of EA, VEPT was most commonly activated for unusual or unexplained injuries or physical findings suggesting that the patient was receiving poor care, emphasizing the importance of the physical exam and history in identifying potential EA. In many cases, the potential abuse was by the patient’s health care decision-maker, demonstrating how challenging it can be to effectively and ethically manage these cases in the ED without expertise.

After a comprehensive VEPT evaluation, high or moderate suspicion for at least one type of EA persisted in 61% of patients. This suggests both that the concerns of ED providers were appropriate, and that providers were not only activating on cases with clear evidence of EA but also on those where there was suspicion that further investigation might clarify. If all cases on which VEPT was activated were judged to have high or moderate suspicion for EA after a comprehensive VEPT evaluation, that would suggest that many potential cases were being missed. The forensic component of the VEPT evaluation, in addition to assisting in evaluating the likelihood of EA, provided complete and accurate documentation of findings. This feature may be critical for justice for the abused older adult in a future legal proceeding,32 including in proceedings to obtain an order of protection.

VEPT was able to initiate many interventions in the hospital and through collaboration with partners in the community. The most striking result is the large percentage of patients with high or moderate suspicion after VEPT evaluation who were discharged to a different home environment or with additional home services. This result suggests that patient safety for patients on whom VEPT was activated may have increased. This finding highlights the breadth of resources available in a hospital and the unique opportunity an ED visit / hospitalization presents to intervene. Infrastructure already in place in hospitals to facilitate transitions of care can be leveraged to assist with discharge to a safer home situation. Notably, many of these patients were discharged to one of two local EA shelters,33 which have a wide variety of services to support them. In contrast, community-based programs, which do not have the resources and infrastructure that a hospital does, have not been able to show similar changes in living situation.34

Only a very small percentage of patients with high or moderate suspicion for EA represented to our ED during the period under study for an EA-related issue after the index visit when VEPT was activated. Given that research suggests that EA victims are usually heavy users of unscheduled acute medical care,35–37 interventions such as this have the potential to affect health care utilization.

Results from the surveys and focus groups suggest that VEPT’s interdisciplinary expertise was helpful to ED clinical providers and viewed favorably by them, increasing the likelihood of recognizing potential EA and decreasing the ED provider burden associated with identification.

Though it only represented a small percentage of VEPT cases, our partnership with APS offered a novel strategy for them to protect older adults in immediate danger or with acute medical issues. This approach may be superior to calling 911 and relying on the local ED without a VEPT program or trying to manage the case in the community. We are working with community agencies to expand this component of VEPT while rigorously evaluating it.

Notably, we used change in home living situation and the implementation of additional home services as proxy measures for increased safety, but these interventions may not have led to increased safety in all cases. Additionally, we have not measured how VEPT interventions affected an older adult’s quality-of-life. Although moving a patient from an unsafe home environment in the community with an abusive caregiver to a nursing home may increase their safety, it may not be what they would have wanted and may isolate them, worsening their quality-of-life. Additionally, the potential for elder abuse exists in nursing homes, particularly from other residents.38 Therefore, it is critical to more deeply explore the consequences of VEPT interventions to ensure that they are not having an unintended negative effect.

Our experience also highlights potential challenges in maintaining and replicating this program. VEPT providers spent significant time performing a comprehensive evaluation on each patient. This suggests that our program is resource-intensive and may be expensive, requiring significant funding or a strategy to generate revenue. That nearly half of all activations occurred outside of regular business hours showed the value of a team available to ED providers at any time, but the cost-benefit of maintaining a 24/7 program needs to be studied.

Finally, the majority of VEPT patients were admitted to the hospital, with many admitted because a safe discharge plan could not be established in the ED. Although ideally no hospital routinely discharges patients into unsafe circumstances, there is significant resistance to what have historically been termed “social” or non-medical admissions, for which Medicare and other insurance companies may not reimburse and which may occupy an inpatient bed for a prolonged period. Given the absence of alternatives for these patients with a high risk of morbidity and mortality, the hospital has been supportive of our program. It will be important to ascertain similar administrative supportiveness as part of VEPT replication attempts.

Limitations

VEPT was launched and evaluated as a single urban, academic, highly resourced ED in the United States focused on geriatric care. Implementing our robust, team-based program in small EDs with limited resources and without routine access to social workers or case managers may be challenging. We believe, however, that capacity exists to develop professional-to-professional telehealth consultation services and local champion programs to overcome this barrier in rural and other low-resource clinical settings. We are already exploring expanding our program via telehealth.

As a comparison group, we used pre-launch data from our hospital with a case finding strategy that relied on specific documentation and may have missed older adults identified by ED providers as elder abuse victims. We also did not compare the accuracy of VEPT assessment to a gold standard. It is possible, for example, that cases we assessed as low suspicion may have been subsequently identified to be abuse victims.

We did not actively follow cases longitudinally after hospital discharge to assess whether safety actually improved and exposure to elder abuse declined. We also did not assess longer-term medical, psychosocial, and legal outcomes.27 We plan to conduct more comprehensive follow-up and to report on this in the future. Despite these limitations, our findings emphasize the potential of ED-based interdisciplinary programs.

Conclusion

The ED has been recognized as an important opportunity to identify elder abuse, and many have advocated for universal or targeted screening in this clinical setting. Before widely implementing strategies to increase EA detection, it is critical to ensure that effective ED-based interventions exist for older adult patients who are identifed. The findings we describe here provide the first evidence suggesting the potential for a comprehensive, interdisciplinary consultation service / response team to increase both EA detection and potentially improve safety through changes in living situation and additional home services. Future research is need to examine longer-term outcomes for this promising approach, which has the potential to improve care for older adults experiencing elder abuse.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1: Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) Operational Protocols

Supplementary Text S1: Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) Post-Launch Provider Surveys to Assess Perception of the Program

Supplementary Text S2: Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) Post-Launch Provider Focus Group Topic Guides to Assess Perception of Program

Supplementary Table S1: Aspects of Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) Activation and Initial Evaluation of Emergency Department Patients (n=200), 4/3/2017-4/2/2019

Supplementary Table S2: Themes and Representative Quotations from Focus Groups of Emergency Department and Hospital Providers about VEPT Program after One Year of Operation

Key Points.

An emergency department visit provides a unique opportunity to identify elder abuse and initiate intervention, but emergency providers rarely do

We developed the Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT), a unique, first-of-its-kind Emergency Department-based interdisciplinary consultation service

VEPT was frequently activated, and safety of patients improved through changes in living situation and additional home services.

Why does this matter?

A comprehensive, interdisciplinary Emergency Department-based consultation service / response team increased identification and contributed to increased safety for older adults experiencing elder abuse. Additional program evaluation studies are needed to elucidate VEPT impact. Dissemination and implementation of similar elder abuse consultation teams in other health systems has the potential to significantly improve elder abuse detection and response in the healthcare setting.

Grants:

This project has been supported by a grant from The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation and by a Change AGEnts Grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation. The program is currently funded through the New York State Office of Victim Services (C11113GG). Tony Rosen’s participation has been supported by a Paul B. Beeson Emerging Leaders Career Development Award in Aging (K76 AG054866) from the National Institute on Aging. The funders have not been involved in the design or conduct of the research.

Sponsor’s Role:

The funders have not been involved in the design or conduct of the research.

Footnotes

- Personal Conflicts: The authors have nothing to disclose.

- Full or adequate disclosure: Other than the funding listed above, the authors have nothing to disclose.

• Meetings: Preliminary findings were presented at Society of Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting, May 2021.

REFERENCES

- 1.Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study: Self-Reported Prevalence and Documented Case Surveys 2012 (online). Available at https://ocfs.ny.gov/reports/aps/Under-the-Radar-2011May12.pdf. Accessed on February 1, 2022.

- 2.National Center for Elder Abuse. The Elder Justice Roadmap: A Stakeholder Initiative to Respond to an Emerging Health, Justice, Financial, and Social Crisis (online). Available at https://www.justice.gov/file/852856/download. Accessed on February 1, 2022.

- 3.Lachs MS, Pillemer KA. Elder abuse. New Engl J Med 2015;373:1947–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yon Y, Mikton CR, Gassoumis ZD, Wilber KH. Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e147–e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortmann C, Fechner G, Bajanowski T, Brinkmann B. Fatal neglect of the elderly. Int J Legal Med 2001;114:191–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiamberg LB, Oehmke J, Zhang Z, et al. Physical abuse of older adults in nursing homes: a random sample survey of adults with an elderly family member in a nursing home. J Elder Abuse Negl 2012;24:65–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen T, Pillemer K, Lachs M. Resident-to-resident aggression in long-term care facilities: An understudied problem. Aggress Violent Behav 2008;13:77–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinoda-Tagawa T, Leonard R, Pontikas J, et al. Resident-to-resident violent incidents in nursing homes. JAMA 2004;291:591–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen T, Lachs MS, Bharucha AJ, et al. Resident-to-resident aggression in long-term care facilities: insights from focus groups of nursing home residents and staff. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA, Charlson ME. The mortality of elder mistreatment. JAMA 1998;280:428–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong XQ, Simon MA, Beck TT, et al. Elder abuse and mortality: the role of psychological and social wellbeing. Gerontology 2011;57:549–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyer CB, Pavlik VN, Murphy KP, Hyman DJ. The high prevalence of depression and dementia in elder abuse or neglect. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:205–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA. Adult protective service use and nursing home placement. Gerontologist 2002;42:734–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong X, Simon MA. Association between reported elder abuse and rates of admission to skilled nursing facilities: findings from a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Gerontology 2013;59:464–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Report on: The Future of Geriatric Care in our Nation’s Emergency Departments: Impact and Implications. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roskos ER, Wilber ST. 210. The effect of future demographic changes on emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:65. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilber ST, Gerson LW, Terrell KM, et al. Geriatric emergency medicine and the 2006 Institute of Medicine reports from the Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the U.S. health system. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:1345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White House Conference on Aging: Elder Justice Policy Brief. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bond MC, Butler KH. Elder abuse and neglect: definitions, epidemiology, and approaches to emergency department screening. Clin Geriatr Med 2013;29:257–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen T, Hargarten S, Flomenbaum NE, Platts-Mills TF. Identifying elder abuse in the Emergency Department: Toward a multidisciplinary team-based approach. Ann Emerg MEd 2016;68:378–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans CS, Hunold KM, Rosen T, Platts-Mills TF. Diagnosis of elder abuse in U.S. Emergency Departments. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:91–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens TB, Richmond NL, Pereira GF, Shenvi CL, Platts-Mills TF. Prevalence of nonmedical problems among older adults presenting to the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen T, Stern ME, Mulcare MR, et al. Emergency department provider perspectives on elder abuse and development of a novel ED-based multidisciplinary intervention team. Emerg Med J 2018;35:600–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kistin CJ, Tien I, Bauchner H, Parker V, Leventhal JM. Factors that influence the effectiveness of child protection teams. Pediatrics 2010;126:94–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hochstadt NJ, Harwicke NJ. How effective is the multidisciplinary approach? A follow-up study. Child Abuse Negl 1985;9:365–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powers E, Tiyyagura G, Asnes AG, et al. Early involvement of the child protection team in the care of injured infants in a pediatric emergency department. J Emerg Med 2019;56:592–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosen T, Mehta-Naik N, Elman A, et al. Improving quality of care in hospitals for victims of elder mistreatment: Development of the Vulnerable Elder Protection Team. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2018;44:164–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grafstein E, Bullard MJ, Warren D, Unger B, CTAS National Working Group. Revision of the Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) Presenting Complaint List version 1.1. CJEM 2008;10:151–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int 1992;13:313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosen T, Platts-Mills TF, Fulmer T. Screening for elder mistreatment in emergency departments: current progress and recommendations for next steps. J Elder Abuse Negl 2020;32:295–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosen T, Stern ME, Elman A, Mulcare MR. Identifying and initiating intervention for elder abuse and neglect in the Emergency Department. Clin Geriatr Med 2018;34:435–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reingold DA. An elder abuse shelter program: Build it and they will come, a long term care based program to address elder abuse in the community. J Gerontol Soc Work 2006;46:123–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosen T, Elman A, Dion S, et al. Review of programs to combat elder mistreatment: Focus on hospitals and level of resources needed. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:1286–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dong X, Simon MA. Elder abuse as a risk factor for hospitalization in older persons. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:911–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong X, Simon MA. Association between elder abuse and use of ED: Findings from the Chicago Health and Aging Project. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, et al. ED use by older victims of family violence. Ann Emerg Med 1997;30:448–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lachs MS, Teresi JA, Ramirez M, et al. The prevalence of resident-to-resident elder mistreatment in nursing homes. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:229–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1: Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) Operational Protocols

Supplementary Text S1: Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) Post-Launch Provider Surveys to Assess Perception of the Program

Supplementary Text S2: Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) Post-Launch Provider Focus Group Topic Guides to Assess Perception of Program

Supplementary Table S1: Aspects of Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT) Activation and Initial Evaluation of Emergency Department Patients (n=200), 4/3/2017-4/2/2019

Supplementary Table S2: Themes and Representative Quotations from Focus Groups of Emergency Department and Hospital Providers about VEPT Program after One Year of Operation