Abstract

The present study of 124 families examined linkages between patterns of sleep arrangement use across the first 6 months post-partum and (a) family socio-demographics, (b) nighttime sleep of infants, mothers, and fathers, and (c) coparenting distress, and mothers’ emotional availability with infants and bedtime. Families were recruited when infants were 1-month-old, and infants were classified, from video data available at 3 and 6 months post-partum, into one of three sleep arrangement pattern groups: Solitary sleep, cosleeping, and cosleeping (at 3 months)-to-solitary sleep (at 6 months). Mothers in cosleeping arrangements were more likely to be at higher socioeconomic risk, non-White, unemployed, and to have completed fewer years of education. Controlling for these variables and for duration of breast feeding and parental depressive and anxiety symptoms, subsequent 3 (sleep arrangement pattern) X 2 (infant age: 3 and 6 months) mixed-model analyses of covariance revealed that sleep arrangement patterns were more robustly linked with maternal sleep than with infant and father sleep. Mothers in cosleeping arrangements experienced more fragmented sleep and greater variability in fragmented sleep relative to mothers of infants in solitary sleep, and fathers in cosleeping arrangements showed greater variability across the week in the number of minutes of nighttime sleep. Cosleeping was associated with mother reports of less positive and more negative coparenting, and mothers in cosleeping arrangements were independently observed to be less emotionally available with their infants at bedtime compared to mothers in the other two sleep arrangement groups. These linkages were largely upheld after statistically controlling for mothers’ stated preference for sleep arrangements they were using.

Keywords: Sleep arrangements, Cosleeping, Infant, Sleep, Parenting, Family

The way parents structure infants sleep during the early post-partum and its linkages with family functioning and have been subjects of considerable debate. Where infants sleep, and for how long, has multiple determinants and has been associated with cultural prescriptions, socio-demographics, practical considerations, and personal choice (Salm Ward et al., 2016; Shimizu & Teti, 2018; Worthman, 2011). Cosleeping, typically identified when the infant shares the same room (roomsharing) and/or the same bed (bedsharing) as the parent, is particularly controversial in Western circles. Bedsharing in particular has been the subject of heated debate as a risk factor in the incidence of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) (American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, 2016). In sharp contrast, bedsharing has been touted by others as a beneficial practice that promotes breastfeeding and enables the parent to monitor the infant more closely during the night (McKenna et al., 2007). Although their cross-sectional design precluded causal inference, Wang et al. (2013) identified cosleeping as causal to disrupted sleep in the infant (Wang et al., 2013), and in their longitudinal study Teti et al. (2016) identified cosleeping as a marker and possible cause of family distress, especially if cosleeping is prolonged. Indeed, Teti and colleagues (Shimizu & Teti, 2018; Teti et al., 2016; Teti et al., 2015) found that mothers who engaged in cosleeping across the first year post-partum experienced higher levels of disrupted maternal sleep, higher levels of marital discord, greater personal and coparenting distress, and more criticism about their choice of sleep arrangement, compared to mothers of infants in predominantly solitary sleeping arrangements. In addition, mothers in persistent cosleeping arrangements were independently rated as less emotionally available with their infants at bedtime, compared to mothers of infants in predominantly solitary sleep arrangements (Teti et al., 2016). Moreover, disrupted sleep, marital discord, coparenting distress, and criticism about infants’ sleep arrangement continued to be significantly greater among persistent cosleeping mothers compared to mothers of infants in solitary sleep regardless of whether cosleeping parents indicated that they preferred their sleeping arrangement (Countermine & Teti, 2010; Shimizu & Teti, 2018, Teti et al., 2016).

Several problems plague this literature, however. To begin, even among Western parents, cultural and socio-demographic factors play a substantive role in choices about whether to cosleep with one’s infant. Both room- and bedsharing forms of cosleeping are significantly more common in non-Western samples, non-White samples, and in families with lower education and income (Jenni & O’Connor, 2005; Luijk et al., 2013; Mileva-Seitz et al., 2017; Mindell et al., 2010). Thus, any examination of correlates of infant sleep arrangements must, in one way or another, address and account for such broad contextual influences, if only to help identify linkages between sleep arrangements and individual and family functioning that are independent of socio-demographic confounds.

Second, studies of linkages between sleep arrangements and family functioning in Western culture reveal that sleep arrangements, perhaps especially during the first six months post-partum, are quite fluid. Hauck et al. (2008) found in a longitudinal study of approximately 2000 families in the US that the vast majority of families engaged in some form of cosleeping with their infants at 1 month (81 %). This percentage dropped to 63 % by 3 months, and to 45 % by 6 months, with further decreases across the remainder of the first year. Teti and colleagues (2015, 2016) more recently replicated these trends, with fully 73 % of families engaged in one or another form of cosleeping (either roomsharing, bedsharing, or both within a given night or across time) at 1 month, which decreased to 45 % by 3 months, 32.9 % by 6 months, and 23 % by 12 months. Important to note is that in Western circles, roomsharing and bedsharing, as different manifestations of cosleeping, are rarely stable early in the post-partum even across short intervals of time and within the same night, and it is not unusual for parents to move their infants in and out of the parents’ sleep spaces across a single night (Ball, 2002). Indeed, parents in Western cultures who engage in exclusive roomsharing or bedsharing with their infants over extended periods of time tend to be relatively small in number, making it difficult to ascertain whether there are differential effects/correlates of persistent bed- vs. roomsharing. What is clear, nonetheless, is that a single “snapshot” of infant sleep arrangements, at a single point in time, especially during the first six months post-partum, is likely not representative of the pattern of sleep arrangements being used with the infant over time.

Such fluidity may not characterize sleep arrangements in non-Western cultures that endorse cosleeping as the normative and recommended practice for infant sleep during the first year of life and beyond. Shimizu et al. (2014), for example, found that ninety-two percent of Japanese families continued the practice of cosleeping with their infants across five decades, from the 1960 s through 2008, despite significant technological advancements, increases in individual educational attainments, and greater numbers of women entering the workforce in Japan across that period of time. No such stability has been apparent in the U.S. and other Western cultures, and available data indicate that among many families in Western circles, parental choices about structuring infant sleep evolve across the first year of life and beyond.

Third, linkages between sleep arrangements and infant and parent sleep are far from settled. Prior work linked cosleeping with one’s infant with increased infant night waking (DeLeon & Karraker, 2007; Ramos et al., 2007), but in these and other studies the source of information about infant sleep was in almost all cases the mother. More recent studies using actigraphy to index infant sleep revealed no differences in infant or paternal sleep quality (e.g., fragmented sleep) in relation to sleep arrangements (Teti et al., 2016; Volkovich et al., 2018). Instead, both studies found that it was maternal sleep that was disrupted to higher degrees in cosleeping arrangements (i.e., greater levels of fragmented sleep), compared to maternal sleep when infants slept in separate quarters away from parents. The present study made use of objective, actigraphic assessments of infant, maternal, and paternal sleep, using a variety of actigraphy-based sleep indices to obtain a more comprehensive assessment of linkages between infant sleep arrangement patterns early in the post-partum and infant, mother, and father sleep.

Fourth, it was of interest to determine if maternal, paternal, and infant sleep, and levels of family distress would be sensitive to differences in infant sleep arrangement patterns during the early post-partum, a period in which infant and maternal sleep dysregulation was already expected to be high. Western parents may find cosleeping with one’s infant to be more acceptable earlier in the first year (i.e., before 6 months of age) than later. Evidence for this is indirect but is suggested by the higher rates of cosleeping observed during the first few months after birth (suggesting greater acceptance of cosleeping at this age), followed by gradual decreases in cosleeping rates at 3 and 6 months (Hauck et al., 2008; Teti et al., 2016). If parents are more accepting of cosleeping with infants before 6 months than later, doing so before 6 months may not be as stressful to parents as it would later, when pressures build to place infants into solitary sleep.

Lastly, prior work on infant sleep arrangements has relied exclusively on parental report, usually by mothers, to provide information on where their infants sleep. Much can be said in favor of using parents as information sources (Seifer, 2005), but it is also the case that parent reports, particularly those that rely on memory of earlier events or when parents are not trained to be observers of their children, may be fraught with inaccuracies (Teti & McGourty, 1996). The present study classified infant sleep arrangements solely through direct observation, from continuous video recordings throughout the night, to determine where infants slept, thus enabling a detailed record of the stability vs. fluidity of infant sleep locations within a given night as well as across time.

1. The present study

The present exploratory study of a rural Pennsylvania sample builds upon earlier work and addressed the following questions:

To what degree are sleep arrangement patterns observed from 3-to-6 months associated with racial/ethnic and family sociodemographics? In addition to identifying correlates of sleep arrangement patterns, we planned to use these analyses to identify potential covariates in subsequent analyses.

Are sleep arrangement patterns linked with actigraphy-provided information on infant, maternal, and paternal sleep, and if so, how? These analyses focused on several actigraph variables drawn from a full week of data collection at 3 and 6 months postpartum: number of minutes of nighttime sleep, variability in nighttime sleep minutes, sleep fragmentation, and variability in sleep fragmentation.

Is early cosleeping (3-to-6 months post-partum), based on direct observation of sleeping arrangements from video, similarly linked with higher coparenting distress and less emotionally available mothering at infant bedtime as was reported in an earlier study (Teti et al., 2016), which was based on information collected across the full first year and used mothers’ reports, not direct observation, about sleep arrangements?

Finally, do linkages between sleep arrangement patterns, coparenting, and quality of maternal behavior at infant bedtimes persist after accounting for mothers’ preferences for the sleep arrangements they were using?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Data for this study were drawn from a larger study funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [R01HD052809; Study of Infants’ Emergent Sleep TrAjectories (SIESTA)], a longitudinal study of parenting, infant sleep and infant development across the first two years awarded to the first author. A project staff member approached mothers in two local hospitals in central Pennsylvania within 48 h after delivery. In total, 898 mothers were approached, at which point the study was described and interested mothers provided further contact information. Multiple birth deliveries were not recruited. Follow-up calls to interested mothers took place 2-to-3 weeks after discharge. Of the 898 approached, 167 agreed to participate, and initial home visits were scheduled when infants were between 4-to-6 weeks of age. The present study focused on data collected during the infants’ first six months, with sociodemographic information collected at 1 months. Of the 167 recruited families, 153 remained in the study at 6 months, and of these, 124 families had codable video and a clearly identifiable sleep arrangement pattern across 3 and 6 months that occurred in sufficient numbers for analysis. These 124 families comprised the final study sample.

Analyses comparing the 43 families who either withdrew from the study or had no or incomplete sleep arrangement data by 6 months with the 167 families initially recruited revealed no differences on any socio-demographic index. Of the 124 families with complete sleep arrangement data at both 3 and 6 months, mothers’ mean age was 29.9 years (range 19-to-43) at birth, and fathers’ mean age was 32.4 years (range 22-to-49) at birth. Seventy-one infants were female. Ninety-five percent of parents were married or living with a partner, and 37 % were primiparous. Eighty-five percent of mothers and 86 % of fathers were White, with the remaining evenly split between African American, Asian American, Latino, or “Other”. Ninety-nine percent of mothers had completed high school, and 60 % of mothers had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Ninety-nine percent of fathers had completed high school, with 66 % completing a bachelor’s degree or higher. Eighty-nine percent of fathers and 61 % of mothers were employed full or part-time at 1 month, and median yearly family income was $65,000.

3. Overall procedure

The present study focused on data obtained when infants were 1, 3, and 6 months of age. At 1 month, mothers completed a demographic questionnaire, including information on child age, parental income, parental education, and infant feeding method, with a follow-up question about feeding method at 3 and 6 months. In addition, at 3 and 6 months an observational assessment was made of infant sleep arrangement and maternal parenting during infant bedtime from a digital video recording set up with the help of the parents. Because most families at 1 month engaged in some form of cosleeping (73 %), observational assessments of infant sleep arrangements from video took place at 3 and 6 months, a time span in which parents’ choice of sleep arrangements across the first year are underway and tend to stabilize by 6 months and thereafter (Teti et al., 2016). This observational video coincided with diary- and actigraphy-based assessments of infant and parent sleep-wake activity for 7 consecutive days at both age points. In addition, at each age point mothers completed a coparenting assessment.

4. Measures

Socio-demographics.

Mothers and fathers provided information on a variety of socio-demographic indices, including yearly family income, infant age, maternal age, education, marital status, age, race, number of children and number of adults living in the home, whether the parent was currently working (not currently working, working < 36 h/week, working > 36 h/week), whether the mothers breastfed up to and including six months post-partum, and whether the infant had been placed in daycare.

A family socioeconomic risk (SER) composite was created that reflected paternal and maternal education level and family income-to-needs ratio. First, both parent’s parental education, reported at recruitment, was separately coded on a 1–8-point scale where 1 = attended high school but did not graduate, 2 = graduated high school, 3 = attended college but did not graduate, 4 = graduated from college with an Associate’s degree, 5 = graduated from college with a Bachelor’s degree, 6 = attended graduate/medical/law school, or other, but did not graduate, 7 = graduated with a Master’s degree, 8 = graduated with a Doctoral degree (Ph.D., Law or Medical degree). Next, a family income-to-needs ratio was computed for each family by dividing family income by the federal poverty threshold for the appropriate family size and the year of report. In the final sample, 6.5 % of families were identified as at or below poverty thresholds (ratio < 1) and 22.5 % were identified as low income (ratio between 1 and 2; Diemer et al., 2013). The final SER score per family was computed by standardizing and combining the z-scores of the averaged family income-to-needs ratio measure and maternal and parental education level. This score was created such that higher composite scores indicated higher risk. Correlations between family income-to-needs ratios and maternal and parent education were all significant (rs=0.38 to.39, ps<0.001). Lastly, a home space constraints variable was created by standardizing and compositing two variables, overall family size and mothers’ ratings on an item from the Sleep Practices Questionnaire (Goldberg & Keller, 2007), “We have limited sleeping space”, rated on a 1-to-5 scale, inquiring about adequacy of sleeping space in the home. Family size and inadequate of sleep space were significantly correlated, r(120) = 0.35, p < .001.

Observed infant sleep arrangements.

At 3 and 6 months infant nighttime sleep arrangement throughout the night was recorded with Bosch Divar XF digital video recorder (DVR), up to four infrared color CCD night-vision cameras and four Channel Vision 5104 microphones, and a portable digital video player that played the recorded video from each camera in real time to help parents reposition cameras if necessary. The up-to-four camera DVR setup allowed observers to view multiple potential sleep arrangement locations simultaneously such as both the infant crib and parent bed. Camera location was informed by individual parent recommendations based on their infant bedtime and nighttime interactions. The night chosen for the video typically occurred during the week and was chosen in collaboration with the family to occur during a typical night of sleep for the infant and when both parents were at home.

To determine infant sleep arrangements, videos at 3 and 6 months were observed across the night from the point of infant sleep onset to final morning wake-up. Coding infant night sleep was a labor-intensive process that required extensive training and took between 5 and 10 h per video. Coding took place across several years and thus there were over 30 trained coders used to score nighttime video. For every 30 s interval, coders blind to all other family data scored infant sleep location (infant’s crib/bed, parent bed, or other location), and parent presence. Inter-coder reliabilities were high, with intraclass correlations (ICCs) ranging from 0.80 to 0.98 based on videos from 40 families that were double-coded.

Because sleep arrangements during this early post-partum period can be fluid, patterns of sleep arrangements were identified that considered consistencies as well as inconsistencies in sleep arrangements across 3 and 6 months. The following clearly identifiable patterns were identified and used in analyses: solitary sleep (the infant slept separately from the parents at both time points, n = 64,); cosleeping (the infant room-shared, bed-shared, or both with a parent at both time points, n = 37); and cosleeping-to-solitary sleep (the infant coslept at 3 months but slept separately at 6 months, n = 23). These three patterns comprised the final study sample (N = 124). There were 4 additional families that were observed moving from solitary sleeping at 3 months to cosleeping at 6 months, comprising a subgroup that was too small for meaningful analyses. Importantly, our observations revealed that cosleeping almost always involved some combination of roomsharing and/or bedsharing, sometimes in conjunction with sleeping in a separate room. Very few infants exclusively roomshared or exclusively bedshared with parents at both 3 and 6 months (ns = 8 and 7, respectively). Again, these subgroups were too small in number for meaningful analyses.

Mothers’ preference for their choice of sleep arrangement.

A stand-alone item from the Sleep Practice Questionnaire (SPQ; Keller & Goldberg, 2004) was used to understand parental comfort regarding their infant’s sleep arrangement. The 62-item SPQ assesses parent-report infant sleep arrangement and parental perceptions around that arrangement. This SPQ item asked, “Is your baby’s current sleep location the place that you most prefer for him/her to sleep” to mothers at both 3 and 6 months. The item was utilized to determine mothers’ preference for the infant sleep arrangement. This item was rated on a 3-point scale: 1 = No, not my preference, 2 = Yes, to some extent my preference, and 3 = Yes, definitely my preference.

Sleep/wake activity.

Both parents and infants wore a Respironics/Mini Mitter actiwatch (model AW-64) during each of the seven nights of data collection at 3 and 6 months to assess sleep-wake activity over the night and across the week on each occasion. Infants wore the actiwatch on their upper ankle (affixed with a soft elastic band) while parents wore it affixed to their non-dominant wrists. Sampling epoch length for all actiwatches was 1 min, and a medium (40 activity counts) wake threshold value was used. Using Actiware (Version 5.0) software, actigraphy data, in actogram format, were uploaded onto a study computer. Time that infants were put to bed, time that infants fell asleep for the night, time infants awoke the next morning, and the times that parents went to sleep and woke up the next morning, were drawn from parent daily diary reports (see below) and actigraphy records. The Sadeh algorithm (Sadeh et al., 1994) was used to identify sleep onset as the first of at least 3 continuous minutes of actigraph-identified sleep and sleep offset as the last of at least 5 continuous minutes of sleep. Actiware® (version 5.0) software (Respironics/Mini Mitter, 2005) was used to determine, for each infant and parent for each of the seven nights, number of minutes of sleep per night and sleep fragmentation (percent of mobile bouts + percent of immobile bouts less than 1 min in duration, reflecting the amount of restlessness throughout the night) (Levine et al., 1987). Actiware® software then calculated, for each participant, the mean and variability (standard deviation) of each of these measures across the full week of data collection at 3 and 6 months.

As a cross-check of actigraph-identified sleep onsets and offsets, parents worked together to complete an infant sleep diary (adapted from Burnham et al., 2002) at every morning of data collection, noting for the previous night when the infant was put down to sleep, night awakenings, and when the infant awoke that. Each parent also completed a daily sleep diary (the 24-Hour Sleep Patterns Interview; Meltzer et al., 2007) for her/his own sleep during the previous night, again as a cross-check of actigraph-identified sleep onsets and offsets. This information was obtained during daily phone calls to the parents each morning during data collection. Mean number of scored nights of actigraphy, out of 7 total nights, was > 6 (median and mode = 7) for infants, mothers, and fathers at both 3 and 6 months. Participants with less than 4 scorable nights of actigraph data were excluded from analysis. In the final study sample (N = 124), the number of families with scorable sleep arrangement patterns and actigraph data at 3 and 6 months ranged from 108 to 116.

Maternal emotional availability (EA) at bedtime.

Among the same videos used to assess nighttime sleep arrangements patterns across 3 and 6 months (n = 124), there were 59 families with scorable bedtime EA video, and thus analyses examining level and longitudinal change in EA across 3 and 6 months were based on these 59 families. The reduced number of videos of bedtime parenting, compared to those used to assess sleep arrangements across the night, was the result primarily of parents turning on the camera system at the end of bedtime, when the bulk of bedtime parenting was over. Mean length of bedtimes was 71.11 min (SD = 65.62) at 3 months, and 48.52 (SD = 43.56) at 6 months, and only two videos at 3 and two at 6 months were eliminated from EA scoring because of insufficient amounts (< 5 min) of bedtime parenting in the recordings. Families without missing maternal EA data at 3 and 6 months (and thus included in analyses) differed from those with missing EA data at either 3 or 6 months such that mothers with complete data at both age points were more likely to be unemployed [χ2 (1) = 9.56, p = .002], to be breast feeding their infants [χ2 (1) = 8.98, p = .003], and to be at lower socioeconomic risk [F(1112) = 3.82, p = .053], which further justified statistically controlling for mothers employment status, socioeconomic risk, and breast feeding status in all analyses.

Mothers’ emotional availability to infants at bedtime was assessed with the well-validated Emotional Availability scales (EAS, Version 3; Biringen et al., 1998). EAS makes use of four scales to assess parental EA: Sensitivity (9-point scale), assessing the parent’s ability to read accurately and respond contingently to child signals with warmth and emotional connectedness; Structuring (5-point scale), measuring parent’s capacity for appropriate scaffolding of child activities and setting appropriate limits; Nonintrusiveness (5-point scale, reverse-scored), reflecting parent’s capacity to respect the child’s autonomy and personal space; and Nonhostility (5-point scale, reverse-scored), assessing parent’s ability to interact with the child without signs of covert or overt irritability/anger. The two child EA scales (responsiveness and involvement) were not scored because of the limited behavioral repertoire of infants in the first year and because they were not straightforwardly applicable to a bedtime context, in which the “task” is to prepare the infant for sleep.

EA was coded by a research assistant trained and certified in the EAS system and who was blind to all other observational data, including nighttime sleep arrangement data. From the videos, it was evident that mothers were much more likely to put infants to bed than fathers. Bedtime EA on fathers could only be obtained from 37 families at both 3 and 6 months. These numbers, when further subdivided by sleep arrangement groupings, yielded cell sizes that were too small for meaningful analyses. Thus, analyses of paternal EA and sleep arrangements were not conducted. At each age point, the four EA scales for mothers were standardized and summed to create a maternal EA composite. Internal reliability of the maternal EA composite was adequate (standardized item alphas =0.77 and.78 at 3 and 6 months, respectively). Interrater reliability on the maternal EA composite was also adequate. The Intraclass correlation (ICC) on the maternal EA composite was.98, based on 42 mother-infant dyads.

Coparenting quality.

The present study included assessments of coparenting quality, as viewed by the mother, which has been viewed as a core indicator of overall family functioning (McHale et al., 2004). Coparenting quality was assessed by mother-report with the Coparenting Relationship Scale (CRS; Feinberg et al., 2012) at 3 and 6 months. The CRS is a 47-item self-report measure in which mothers rated each item on a 7-point scale (ranging from “not true of us” to “very true of us” for the first 39 items; and “never” to “very often” for the last 8 items). The CRS yields seven dimensions of coparenting: Agreement with Partner, Increased Closeness, Support-Cooperation, Endorses Partner’s Parenting, Division of Labor, Exposure to Conflict, and Competition-Undermining. Each of these individual coparenting dimensions have adequate psychometrics (construct validity and test-retest and internal reliability (Feinberg et al., 2012). In the present study, a positive coparenting quality composite measure was created at each age point by summing the five dimensions of Agreement with Partner, Increased Closeness, Support-Cooperation, Endorses Partner’s Parenting, and Division of Labor (alphas =0.81 and.84 at 3 and 6 months, respectively. Similarly, the two dimensions of Exposure to Conflict and Competition-Undermining were summed to form a negative coparenting quality composite variable at each age point (alphas =0.75 and.80 at 3 and 6 months, respectively).

Lastly, mother reports of depressive and anxiety symptoms were obtained at 1-, 3- and 6-months of infant age using the depression and anxiety subscales of the Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90–R; Derogatis, 1994). For each parent, a mean depressive symptom score and a mean anxiety symptom score was obtained by averaging the scores for each subscale across 1, 3, and 6 months.

5. Results

5.1. Socio-demographics and infant sleep arrangement patterns

Initial descriptive analyses indicated that, for the most part, sociodemographic variables were minimally skewed, with the exception of race (skewness = 2.03), reflecting the preponderance of White families in the study sample, yearly family income (skewness = 2.17), reflecting the fact that less than 20% of families reported yearly family incomes of > $100,000/year, and space constraints (skewness = 1.07), indicating that the majority of families did not report inadequate sleeping space.

One-way analyses of variance with pairwise comparisons and chi-square analyses were performed to identify relations between infant sleep arrangement patterns obtained from video records at 3 and 6 months (solitary, cosleeping, and cosleeping-to-solitary sleep) and socio-demographic variables. Results are depicted in Table 1. Sleep arrangement patterns were significantly associated with maternal education, F(2121) = 3.50, p = .03, partial η2 = 0.06, socioeconomic risk, F(2119) = 3.44, p = .035, partial η2 = 0.05, and space constraints, F(2, 116) = 8.71, p < .001, partial η2 = .13. Pairwise comparisons, using α = 0.017 (corrected for multiple comparisons) revealed that mothers who coslept with their infants completed fewer years of education, were at significantly higher socioeconomic risk than mothers of infants in solitary sleep and reported less space for sleeping in the home. Cosleepers were also at higher socioeconomic risk than families who coslept at 3 months but moved their infants into solitary sleep by 6 months. Analyses also revealed that cosleeping was significantly associated with being non-White, χ2 (2) = 15.19, p = .001, and with mothers who reported that they were unemployed at a level that approached significance, χ2 (2) = 7.35, p = .025. No other socio-demographic variable was associated with sleep arrangement patterns. To rule out the potential impact of these socio-demographics, socioeconomic risk, race, mothers’ employment status, and space constraints were used as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic and socioeconomic associations with sleep arrangement patterns.

| Sleep arrangement pattern 3-to-6 months |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Solitary | Cosleep |

Cosleep to solitary | |

| Mean (SD) n | |||

|

| |||

| Maternal age (yrs.) | 30.16 (3.95) n = 64 | 29.08 (6.50) n = 37 | 30.23 (5.90) n = 22 |

| Paternal age (yrs.) | 32.0 (28.08) n = 62 | 32.47 (6.43) n = 32 | 33.61(6.44) n = 23 |

| Maternal education* | 5.28 (1.71)a n = 64 | 4.24 (2.24)bc n = 37 | 4.91 (1.65)ac n = 23 |

| Paternal education* | 5.03 (1.67) n = 61 | 4.44 (1.93) n = 32 | 5.13 (2.10) n = 23 |

| Annual income** 74,097 (37,632) n = 59 | 60,416 (54,030) n = 34 | 86,435 (69,536) n = 23 | |

| Number of children | 1.89 (0.86) n = 64 | 2.05 (0.94) n = 37 | 1.70 (0.64) n = 22 |

| Space constraints | −0.38 (1.37)a n = 62 | 0.77 (1.73)b n = 36 | −.61 (1.20)a n = 21 |

| Socioeconomic risk | −0.43 (1.89)a n = 59 | 0.69 (2.52)b n = 32 | −.66 (2.89)a n = 23 |

| Solitary | Cosleep | Cosleep to solitary | |

| n (%) of Participants Within Each Sleep Arrangement Pattern | |||

| Mother’s race | |||

| White | 61 (95.3 %)a | 24 (66.7 %)b | 20 (87 %)ab |

| Non-White | 3 (4.7 %) | 12 (33.3) % | 3 (13 %) |

| Father’s race | |||

| White | 57 (93.4 %)a | 22 (71.0 %)b | 19 (90.5 %)ab |

| Non-White | 4 (6.6 %) | 9 (29.0 %) | 2 (9.5 %) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/ living with partner | 63 (98.4 %) | 33 (89.2 %) | 22 (95.7 %) |

| Single/not living with partner | 1 (1.6 %) | 4 (10.8 %) | 1 (4.3 %) |

| Sex of infant | |||

| Male | 27 (42.2 %) | 14 (37.8 %) | 12 (52.2 %) |

| Female | 37 (57.8 %) | 23 (62.2 %) | 11 (47.8 %) |

| Mother employed? | |||

| Yes | 46 (71.9 %)a | 16 (44.4 %)b | 14 (60.9 %)ab |

| No | 18 (28.1 %) | 20 (55.6 %) | 9 (31.9 %) |

| Father employed? | |||

| Yes | 58 (93.5 %) | 29 (90.6 %) | 0 (100.0 %) |

| No | 4 (6.5 %) | 3 (9.4 %) | 0 (0 %) |

Note: Values in parentheses are standard deviations or percentages. Values with different superscripts differed significantly between sleep arrangement category at α = 0.017, corrected for multiple comparisons.

Highest level of education coded as 1: Did not complete high school; 2: High school graduate; 3: College, no degree; 4: Associate’s degree; 5: Bachelor’s degree; 6: Attended graduate school, no degree; 7: Master’s degree; 8: Doctoral, law, or medical degree.

Annual income expressed in dollars.

Space constraints is a z-score composite of two variables: family size and mothers’ ratings of sleep space inadequacy in the home. Higher scores indicate greater space constraints.

Socioeconomic risk is a standardized composite of income-to-needs ratio and parental education. Higher scores indicate higher socioeconomic risk.

Additional covariates were used in analyses because of their links with sleep arrangements and family sleep (Ball, 2002; Teti & Crosby, 2012). These included duration of breast feeding, indexed as the number of measurement occasions during the first six months that mothers were engaged in breastfeeding their infants, with breastfeeding scores ranging from 0 (never breastfed the infant) to 3 (breastfed the infant at 1, 3, and 6 months). In addition, maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms (from Derogatis, 1994 – see above) were included as covariates. Whether or not infants were in daycare arrangements during the first six months were not associated with sleep arrangement patterns and thus were not included as a covariate. Overall, the collinearity among these 7 covariates was low (M=0.15), with the highest collinearity found between mothers’ depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms, r(121) = 0.74, p < .001 and the remaining associations ranging between 0.00 and 0.27 (absolute values).

5.2. Maternal, paternal, and infant sleep and sleep arrangements patterns

A series of 3 (sleep arrangements: Solitary, cosleeping, and cosleeping to solitary) X 2 (3 months, 6 months) mixed-model analyses of covariance was conducted to examine the independent and interactive linkages between 3-to-6 month sleep arrangement patterns and infant age during the early post-partum and mothers’, fathers’, and infants’ sleep. Dependent variables in these analyses were number of minutes asleep during the nighttime sleep period, variability in nighttime sleep, sleep fragmentation, and variability in sleep fragmentation, averaged by Actiware software across the full week of data collection at 3 and 6 months. These analyses included socioeconomic risk, race, mothers’ employment status, space constraints, duration of breast feeding, mean depressive symptoms and mean anxiety symptoms across the first six months as covariates. Significant main effects of sleep arrangements were followed by post-hoc pairwise comparisons that were adjusted for the number of comparisons per analysis using the Bonferroni procedure (critical value for significance α = 0.017).

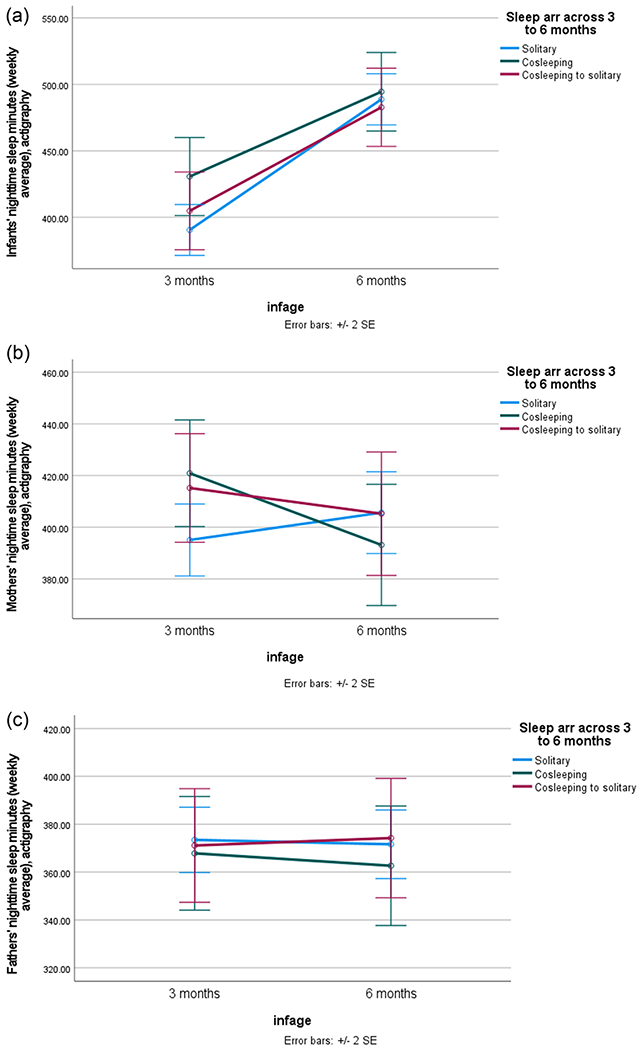

5.3. Mean and variability in nighttime sleep minutes

Analyses of nighttime sleep minutes revealed no main or interactive effects of sleep arrangement patterns on infant sleep minutes. As anticipated, infant age was a strong predictor of infant sleep, which was found to increase significantly from 3-to-6 months, F(1,82) = 16.00, p < .001, partial η2 = .16 (Fig. 1a). This increase is likely a reflection of expected developments in infant sleep regulation and consolidation across the first six months (Camerota et al., 2019). In contrast to infants, for mothers there was a sleep arrangement X infant age interaction, F(2,87) = 4.07, p = .02, partial η2 = 0.09 (Fig. 1b). Analyses of simple effects revealed that, whereas no change in mothers’ nighttime sleep minutes from 3-to-6 months were observed in either the solitary or cosleeping-to-solitary groups, nighttime sleep minutes decreased significantly among mothers in the cosleeping group, p = .01. Interestingly, neither infant age, sleep arrangement patterns, nor their interaction predicted fathers’ nighttime sleep minutes (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Mean nighttime sleep minutes for infants, mothers, and fathers by sleep arrangement pattern, adjusted for covariates. Covariates in analyses include socioeconomic risk, race, mothers’ employment status, space constraints, duration of breastfeeding, parental depressive symptoms, and parental anxiety symptoms.

Analyses of variability in nighttime sleep minutes across the week revealed no linkages with infant age, sleep arrangement patterns, or their interaction for infants and mothers (Fig. 2a and b). Variability in fathers’ sleep minutes, however, was significantly predicated by sleep arrangement pattern, F(2, 84) = 3.29, p = .04, partial η2 = 0.07. Pairwise contrasts indicated significantly higher levels of variability in fathers’ nighttime sleep minutes in cosleeping families relative to solitary sleeping families (p = .01) (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Variability (standard deviation) in nighttime sleep minutes across the week for infants, mothers, and fathers by sleep arrangement pattern, adjusted for covariates. Covariates in analyses include socioeconomic risk, race, mothers’ employment status, space constraints, duration of breastfeeding, parental depressive symptoms, and parental anxiety symptoms.

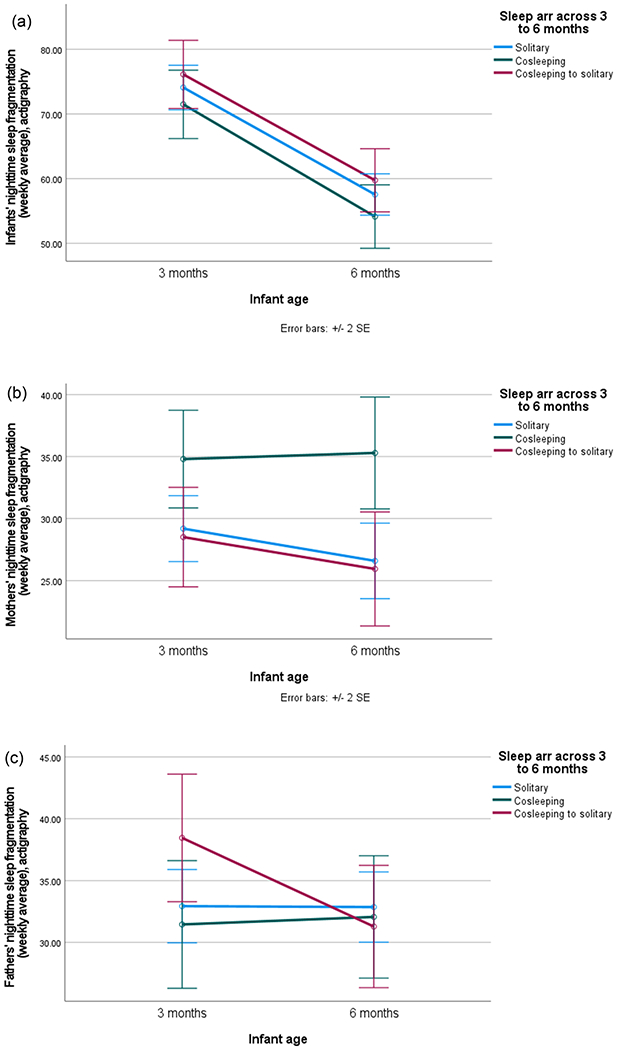

5.4. Mean and variability in sleep fragmentation

Analyses revealed that infant sleep fragmentation decreased significantly from 3-to-6 months, F(1, 82) = 34.46, p < .001, partial η2 = .30, reflecting, as expected, normative increases in infant sleep regulation during the early post-partum (Fig. 3a). No associations were found between infant sleep fragmentation and sleep arrangement patterns or the sleep arrangement patterns X infant age interaction. For mothers, a significant main effect of sleep arrangement patterns emerged, F(2, 87) = 5.64, p = .005, partial η2 = .12, with contrasts showing that mothers in cosleeping arrangements had significantly more fragmented sleep than mothers’ sleep in solitary (p = .003) or cosleeping-to-solitary (p = .004) arrangements (Fig. 3b). No associations were found between fathers’ sleep fragmentation and infant age, sleep arrangement patterns, or their interaction. (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Mean nighttime fragmented sleep for infants, mothers, and fathers by sleep arrangement pattern, adjusted for covariates. Covariates in analyses include socioeconomic risk, race, mothers’ employment status, space constraints, duration of breastfeeding, parental depressive symptoms, and parental anxiety symptoms.

Analyses of variability in sleep fragmentation across the week revealed no main or interactive effects for infants (Fig. 4a). For mothers, however, variability in sleep fragmentation significantly decreased with infant age, F (1,87) = 7.95, p = .006, partial η2 = .08, and was also linked with sleep arrangement patterns, F(2, 87) = 3.62, p = .03, partial η2 = .08. Contrasts revealed significantly greater variability in sleep fragmentation in cosleeping mothers compared to mothers in cosleeping-to-solitary sleeping arrangements (p = .009), but no other pairwise differences emerged (Fig. 4b). There were no associations between variability in fathers’ sleep fragmentation and sleep arrangement pattern, infant age, or the sleep arrangement pattern X infant age interaction (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Variability (standard deviation) in nighttime sleep fragmentation across the week for infants, mothers, and fathers by sleep arrangement patterns, adjusted for covariates. Covariates in analyses include socioeconomic risk, race, mothers’ employment status, space constraints, duration of breastfeeding, parental depressive symptoms, and parental anxiety symptoms.

5.5. Coparenting, bedtime parenting, and sleep arrangement patterns

Similar 3 (sleep arrangement patterns) X 2 (infant age) mixed-model analyses of covariance were conducted to examine the main and interactive effects of sleep arrangement and infant age on mothers’ perceptions of coparenting quality and mothers’ emotional availability with their infants at bedtime (coded blindly from video observations), again with race, socioeconomic risk, mothers’ employment status, space constraints, duration of breast feeding, parental depressive symptoms, and parental anxiety symptoms as covariates. To determine whether mothers’ sleep should also be included as covariates in these analyses, a series of Pearson correlations was conducted to determine if the number of minutes of mothers’ nighttime sleep, sleep fragmentation, and variability in sleep minutes and fragmentation across the week at 3 and 6 months were associated with mothers’ reports of coparenting quality and observations of mothers’ emotional availability at bedtime. Of these, only one significant association emerged (out of 24 total that were conducted), which is not more than what one might have expected by chance at alpha = 0.05. Thus, maternal sleep variables were not additionally included in these ANCOVAs as covariates.

Analyses on mothers’ reports of positive coparenting revealed a significant effect of infant age, F (1,96) = 4.70, p = .033, partial η2 = .05, such that perceptions of positive coparenting significantly decreased from 3-to-6 months. There was also a significant effect of sleep arrangements, F (2, 96) = 3.27, p = .04, partial η2 = .06. Contrasts revealed that mothers of infants in cosleeping-to-solitary sleep arrangements reported significantly lower positive coparenting than mothers of infants in solitary sleep arrangements, ps = 0.017 (Fig 5a). Analyses of mothers’ reports of negative coparenting also revealed a significant main effect of sleep arrangement pattern, F (2,96) = 5.85, p = .004, partial η2 = .11. Contrasts revealed that mothers of infants in solitary sleep arrangements reported significantly lower negative coparenting perceptions than mothers of infants in cosleeping-to-solitary sleep arrangements, p = .002, with the contrast between the solitary and the cosleeping group approaching significance (p = .027) (see Fig. 5b). No interactive effects of sleep arrangement X infant age were found.

Fig. 5.

Mother-reported coparenting quality (positive and negative) and observed emotional availability with infants at bedtime by sleep arrangement pattern, adjusted for covariates. Covariates in analyses include socioeconomic risk, race, mothers’ employment status, space constraints, duration of breastfeeding, parental depressive symptoms, and parental anxiety symptoms.

Lastly, analyses of mothers’ emotional availability at bedtime revealed a significant effect of sleep arrangement pattern, F(2, 50) = 3.97, p = .025, partial η2 = .14, but no effect of infant age or sleep arrangement pattern X age interaction (Fig. 5c). Contrasts revealed that mothers of infants in cosleeping arrangements were observed to be significantly less emotionally available to their infants than mothers of infants in solitary sleep (p < .009), but not different from mothers in cosleeping-to-solitary arrangements.

A final set of analyses was conducted that examined whether mothers’ level of preference for their infants’ sleep arrangements (1 = not at all my preference, 2 = to some degree my preference, 3 = yes, definitely my preference) mattered in terms of the linkages reported above between sleep arrangement patterns, mothers’ reports of coparenting quality, and mothers’ emotional availability at infant bedtime. To begin, we note that mothers’ preferences for the sleep arrangements they were using were significantly associated across time, χ2(4) = 36.89, p < .001, phi = 0.50, and thus mothers’ preference scores at 3 and 6 months were composited into a single preference score per mother. This composite preference score was then examined in relation to sleep arrangement patterns. That association was significant, χ2(4) = 24.99, p < .001, phi = 0.46, reflecting, that mothers who placed their infants in solitary sleeping arrangements were significantly more likely to express a strong preference for that arrangement than mothers whose infants were in cosleeping and cosleeping-to-solitary sleeping arrangements. Ninety-seven percent of mothers of infants in solitary sleeping arrangements expressed a strong preference (> 2.5 on a 3-point scale) for this sleep arrangement, compared to 54% of mothers in cosleeping arrangements and 35% of mothers in cosleeping-to-solitary arrangements.

To determine if the differences reported above between sleep arrangement patterns, mothers’ coparenting perceptions, and observed emotional availability at infant bedtime, which favored mothers in solitary sleeping arrangements, were the result of mothers’ stronger preferences for solitary sleeping arrangements, 3 × 2 analyses of covariance (sleep arrangement pattern X infant age) were repeated, adding mothers’ preference scores for their sleep arrangements as an 8th covariate, along with race, socioeconomic risk, maternal employment status, and space constraints. Results with this covariate added suggested that maternal preferences for the sleep arrangements they were using mattered for positive coparenting, but not for negative coparenting and mothers’ emotional availability. Specifically, the main effect of sleep arrangement patterns on mothers’ perceptions of positive coparenting was no longer significant, p = .12. By contrast, adding mothers’ preferences as a covariate had no impact on the statistically significant results for mothers’ reports of negative coparenting, which continued to show a main effect of sleep arrangement pattern, F(2, 94) = 4.28, p = .017, partial η2 = .08, with contrasts again showing significantly lower levels of negative coparenting reported by mothers of infants in cosleeping-to-solitary sleeping arrangements (p = .005). Adding mothers’ preferences as a covariate also had no impact on the significant main effect of sleep arrangements on maternal EA at bedtime, F(2, 48) = 8.80, p < .001, partial η2 = .27. Contrasts again revealed that mothers of infants in solitary sleep were independently rated as significantly more emotionally available to their infants at bedtime than mothers of infants in cosleeping arrangements (p < .001). In addition, the contrast between mothers of solitary-sleeping infants and mothers in cosleeping-to-solitary sleeping arrangements approached significance (p = .023). Overall, these results indicated that linkages between infant sleep arrangement patterns and two key indicators of family functioning, coparenting and quality of mothers’ behavior with infants at bedtime, were largely independent of the degree to which mothers preferred the sleep arrangements they were using.

6. Discussion

The present study had two primary goals. First, we sought to examine socio-demographic and racial/ethnic correlates of sleep arrangement usage with infants during the first 6 months post-partum. Second, after statistically controlling for these associations, we aimed to assess whether sleep arrangement patterns identified during the 1st 6 months were associated with infant, maternal, and paternal sleep behavior, maternal emotional availability with infants and bedtime, and coparenting quality. Unique to the present study was that infant sleep arrangement patterns were identified directly from video-recordings of where infants were sleeping, rather than relying on parental report. Of particular interest was whether the linkages between sleep arrangement use, sleep, and mothers’ parenting at bedtime and coparenting quality, obtained during this early post-partum period, were similar to those obtained in an earlier report (Teti et al., 2016) that was based on a longer period of time post-partum. Lastly, we wished to determine to what degree any relations obtained remained significant after accounting for mothers’ stated preferences for the sleep arrangements they were using.

Consistent with prior work (Jenni & O’Connor, 2005; Luijk et al., 2013; Mileva-Seitz et al., 2017; Mindell et al., 2010), families who co-slept from 3-to-6 months were more likely to have mothers who completed fewer years of education, to be at higher overall socioeconomic risk, to be non-White, to be unemployed at recruitment, and to be more likely to report inadequate space for sleeping. No differences emerged for fathers’ education, maternal and paternal age, number of children, marital status, fathers’ employment status, and sex of infant. Although reasons for choosing a sleeping arrangement with one’s infant can be multiply determined, the greater tendency for non-White families to use cosleeping arrangements beyond one month post-partum may be informed at least in part by norms prescribed by their culture of origin (Luijk et al., 2013). In addition, among families with limited economic resources, the tendency to cosleep may relate to inadequate sleeping space within the household. This is supported by our findings that insufficient space for sleeping was significantly and positively associated with socioeconomic risk.

Despite the links with socio-demographics, it is noteworthy that sleeping arrangement patterns were significantly associated with infant and parent sleep, and in particular maternal sleep, after socio-demographics, duration of breastfeeding, and parental depressive and anxiety symptoms were statistically controlled. Further, the patterns of associations in the present study, which were limited to the early post-partum, were similar to and extended those from prior work that examined these linkages over similar and longer periods of post-partum time. Infant sleep duration increased and fragmentation decreased from 3-to-6 months in the present study, reflecting the expected increases in infant sleep regulation and consolidation during the first six months and afterward, as reported in earlier work (Camerota et al., 2019; Teti et al., 2016; Volkovich et al., 2018). Interestingly, whereas infant night sleep minutes and fragmentation were unrelated to sleep arrangement patterns, mothers’ sleep fragmentation was significantly linked with sleep arrangement patterns such that mothers who co-slept experienced more fragmented sleep than mothers who did not. In addition, nighttime sleep minutes decreased from 3-to-6 months among mothers who co-slept with their infants, but no such decreases were observed among mothers in solitary and cosleeping-to-solitary sleeping arrangements.

Broadly speaking, these findings replicate and extend those of Teti et al. (2016), based on a full post-partum year’s assessment, and from Volkovich et al. (2018), both of whom found that it is not infants’ sleep but mothers’ sleep that is at risk for disruption in cosleeping arrangements. This in turn raises concerns about possible longer-term deleterious consequences for maternal personal and relational health among mothers who habitually cosleep. Interestingly, fewer linkages between sleep characteristics and sleep arrangements and infant age were found for fathers. Reasons for this are unclear, but such linkages may depend on fathers’ levels of involvement with infant nighttime care, which we suspect is highly variable across families. Understanding the factors that underlie fathers’ sleep during the transition to parenthood, and the significance that holds for overall family functioning is, in our view, an area highly worthy of further study.

The present study’s focus on variability of infant and parent sleep is an important extension of earlier work, borne out of studies showing that day-to-day variability in sleep is detrimental to parental functioning with infants (e.g., Bai et al., 2020). Again, just as mothers in cosleeping arrangements were found to be at risk for elevated sleep fragmentation, these same mothers were more likely to have more variability in night-to-night sleep fragmentation, and fathers in cosleeping arrangements experienced greater variability in sleep minutes, compared to parents of infants in solitary sleep. More research is needed to better understand the mechanisms that account for the generally poorer sleep quality of parents who cosleep. Likely suspects to examine may be increased tendencies among parents who cosleep with their infants to be awakened by minor infant movements, postural and positional changes, or other infant arousals such as non-distressed vocalizations, that may vary from night-to-night. Such research would be facilitated by the use of newly available large-storage, low-light, multiple input video systems that can be time-synced with actigraphic monitoring of the infant and parent during the night.

The present findings that mother reports of coparenting quality and independent ratings of mothers’ emotional availability with infants at bedtime were less optimal among mothers in cosleeping arrangements replicates earlier work based on the first year postpartum (Teti et al., 2016). Worthy of note is the fact that these relations upheld after statistically controlling for socio-economic risk, race, maternal employment status, space constraints, duration of breastfeeding, and parental depressive and anxiety symptoms. In addition, with the exception of positive coparenting perceptions, whose relation with sleep arrangement patterns was no longer significant, these relations were maintained after also statistically controlling for mothers’ stated preferences for the sleep arrangements they were using. Importantly, these findings did not appear to be associated with mothers’ sleep behavior, which were largely uncorrelated with coparenting and parenting indices.

Collectively, these findings beg the broader question of to what degree infant sleep arrangement patterns bear a causal relation to sleep behavior, coparenting, and parenting. With respect to infant and parenting sleep, we propose that their linkages with sleep arrangements are bidirectional. The manner in which infant sleep is structured is likely to exert effects on parent and infant sleep that are theoretically plausible. At the same time, it is also plausible that parental choices on how to structure their infants’ sleep could be influenced by infant sleep characteristics, as for example if parents increase their use of cosleeping with their infants in response to persistent infant nighttime distress (Ramos et al., 2007).

Similarly, we propose that linkages between infant sleep arrangements and parenting and coparenting subsystems are also bidirectional. Associations between sleep arrangements and parental and family functioning have been difficult to interpret because sleep arrangements are invariably associated with racial/ethnic and socio-demographic variables that operate as potential confounds. The present study attempted to address these confounds by controlling for all socio-demographics that were associated with sleep arrangement patterns, and as well controlling for duration of breastfeeding and parental depressive and anxiety symptoms, but we acknowledge that our study was limited in its capacity to address potential confounds because the level of racial/ethnic diversity in the present sample was low and because the overall sample size was limited.

It is important to note that American Academy of Pediatrics has strongly discouraged bedsharing and instead encourages parents to room share with their infants for at least the first six months after birth, arguing that room sharing promotes proximity to and monitoring of the infant without the potential dangers of sharing the same sleeping surface with the infant (American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, 2016). We also understand, however, that parents’ choice of sleep arrangements is highly personal, multiply influenced, and done with what is believed to be “what is best for the baby” (Worthman, 2011). For example, parents’ choice to cosleep with their infant may be based on a sincere belief that the added proximity to the infant and greater opportunities to provide contact comfort is desirable because of a belief that it promotes parent-infant bonding and secure attachments. The “attachment parenting” perspective, as an illustration, endorses these points (Granju, 1999; Miller & Commons, 2010), although there is precious little empirical justification that supports a clear link between cosleeping and more secure attachments. Indeed, there is a countervailing perspective, with some empirical support, that persistent cosleeping with one’s infant is associated with heightened family stress, as exemplified by greater marital discord, coparenting distress, criticism from others, and reduced emotional availability with the infant at bedtime (Cortesi et al., 2008; Countermine & Teti, 2010; Shimizu & Teti, 2018). We hasten to note that these findings may be peculiar to cultures that do not endorse cosleeping with one’s infant as a long-term beneficial sleep arrangement, and not to cultures in which prolonged cosleeping is endorsed and accepted (Shimizu & Teti, 2018). Nevertheless, we offer that to the extent that persistent cosleeping heightens family stress, this can negatively spill-over into marital, coparental, and parent-infant relationships and interfere with the couple relationship and intimacy. Indirect support for this comes from the present study, in which significant associations between sleep arrangement patterns, coparenting quality, and mothers’ observed emotional availability with infants, favoring solitary sleep arrangements, were maintained even after statistically controlling for all covariates and controlling for mothers’ preference for the sleep arrangements they were using.

There is, nevertheless, other evidence that suggests that family dynamics, and perhaps early coparenting and marital quality in particular, may shape mothers’ use of particular sleeping arrangements. Teti et al. (2015) found that mothers who were cosleeping at one month and who reported high coparenting distress were more likely than mothers with more supportive coparenting relationships to keep their infants in cosleeping arrangements across the first six months. This was not the case for cosleeping mothers at one month with more supportive coparenting relationships, who were significantly more likely to transition their infants out of cosleeping arrangements and into solitary sleep. These findings suggested that mothers may compensate for an unsupportive partner by seeking out their infants during the night and setting up sleep arrangements that promote proximity and physical closeness (e.g., cosleeping). Again, these patterns may be peculiar to cultures that in the main do not endorse cosleeping as a long-term acceptable infant sleep arrangement. To say the least, the extent to which sleep arrangement patterns are causal to individual and family-level processes, or is shaped by them, is an area ripe for further study and one that should be pursued in cultures that do and do not endorse persistent infant-parent cosleeping.

The present study had several strengths. These include reliance on direct observation, rather than parental report, to determine sleep relationship patterning. Second, it made use of week-long, day-to-day objective (actigraphic) assessments of infant, mother, and father sleep, thus obtaining a representative sample of sleep in all family members that was not based on parent-report. Third, its longitudinal design enabled the identification of patterns of sleep arrangement use across time, which is essential in light of the high fluidity of sleep arrangement use for many families in which cosleeping is not the norm.

At the same time, several weaknesses need to be acknowledged. The present study had a low percentage of non-White families, which compromised our ability to document reliable associations between socio-demographics and sleep arrangements. Second, although our institution’s office for human subjects’ protection only allowed us one evening of video collection of bedtime (for privacy reasons), our assessment of sleep arrangements and maternal emotional availability was based on only one evening during the week of data collection, and thus not as representative a sample of data as that collected for infant and parent sleep. Third, our results for family functioning concentrated on mothers because of the reduced availability of fathers for data collection, particularly in the video recordings of emotional availability at infant bedtimes. Fourth, we were unable to make clear determinations of the differential “effects” of roomsharing vs. bedsharing, as two forms of cosleeping, on sleep, coparenting, and maternal emotional availability. Only a handful of families exclusively room- or bedshared with their infants from 3 to 6 months, reflecting more broadly that parents who choose to cosleep tend to make use of both room- and bedsharing across the infants’ first six months. Lastly, the smaller subsample of families for whom mothers’ emotional availability was available at both 3 and 6 months was a weakness, although we note that we found significant linkages between sleep arrangements and maternal EA that replicated earlier work (Teti et al., 2016) despite the reduced sample size.

In the main, the present study extended earlier work (Teti et al., 2016, Volkovich et al., 2018) by showing linkages between longitudinal sleep arrangement patterns during the first six months post-partum infant and parent sleep, coparenting quality, and mothers’ emotional availability with infants at bedtime. Early sleep arrangements appear to have implications for parent sleep and parenting/coparenting quality, which in turn may have downstream organizational influences on family health and well-being and child development. Much more needs to be learned, both in Western and non-Western circles, about how these processes unfold.

Author statement

This paper was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Health and Human Development, U.S.A., R01 HD052809, awarded to the first author. We thank Molly Countermine, Corey Whitesell, Cori Reed, and Renee Stewart for their assistance in coordinating this project. Special thanks are given to the participating families. Correspondence regarding this paper should be addressed to Douglas M. Teti, Human Development and Family Studies, 105 Health and Human Development Building, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802 (dmt16@psu.edu). Access to the data for this study can be requested by emailing the corresponding author.U.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest

None.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. (2016). SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: Evidence base for 2016 updated recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics, 138, 1–14. 10.1542/peds.2016-2940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Whitesell CJ, & Teti DM (2020). Maternal sleep patterns and parenting quality during infants’ first 6 months. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(3), 291–300. 10.1037/fam0000608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball HL (2002). Reasons to bed-share: Why parents sleep with their infants. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 20, 207–221. 10.1080/0264683021000033147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biringen Z, Robinson JL, Emde RN (1998). “Manual for scoring the emotional availability scales” (3rd ed.). Unpublished manuscript, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham MM, Goodlin-Jones BL, Gaylor EE, & Anders TF (2002). Nighttime sleep-wake patterns and self-soothing from birth to one year of age: A longitudinal intervention study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 43, 713–725. 10.1111/1469-7610.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camerota M, Propper CB, & Teti DM (2019). Intrinsic and extrinsic factors predicting infant sleep: Moving beyond main effects. Developmental Review, 53, 1–20. 10.1016/j.dr.2019.100871 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cortesi F, Giannotti F, Sebastiani T, Vagnoni C, & Marioni P (2008). Cosleeping versus solitary sleeping in children with bedtime problems: Child emotional problems and parental distress. Behavioral Sleeping Medicine, 6, 89–105. 10.1080/15402000801952922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Countermine MS, & Teti DM (2010). Sleep arrangements and maternal adaptation in infancy. Infant Mental Health Journal, 31(6), 647–663. 10.1002/imhj.20276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon CW, & Karraker KH (2007). Intrinsic and extrinsic factors associated with night waking in 9-month-old infants. Infant Behavior and Development, 30(4), 596–605. 10.1016/J.INFBEH.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR (1994). SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90-R: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Brown LD, & Kan ML (2012). A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting. Parenting, 12(1), 1–21. 10.1080/15295192.2012.638870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg WA, & Keller MA (2007). Parent-infant cosleeping: Why the interest and concern? Infant and Child Development, 16, 331–339. 10.1002/icd.523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granju KA (1999). Attachment parenting: Instinctive care for your baby and young child (New York). Pocket Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hauck FR, Signore C, Fein SB, & Raju TN (2008). Infant sleeping arrangements and practices during the first year of life. Pediatrics, 122, S113–S120. 10.1542/peds.2008-1315o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenni OG, & O’Connor BB (2005). Children’s sleep: An interplay between culture and biology. Pediatrics, 115, 204–216. 10.1542/peds.2004-0815B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MA, & Goldberg WA (2004). Cosleeping: help or hindrance for young children’s independence. Infant and Child Development, 13, 369–388. 10.1002/icd.365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Roehrs T, Stepanski E, Zorick F, & Roth T (1987). Fragmenting sleep diminishes its recuperative value. Sleeping: Journal of Sleeping Research & Sleeping Medicine, 10, 590–599. 10.1093/sleep/10.6.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luijk MPCM, Mileva-Seitz VR, Jansen PW, van IJzendoorn MH, Jaddoe VWV, Raat H, Hofman A, Verhulst FC, & Tiemeier H (2013). Ethnic differences in prevalence and determinants of mother–child bedsharing in early childhood. Sleeping Medicine, 14(11), 1092–1099. 10.1016/J.SLEEP.2013.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Kazali C, Rotman T, Talbot J, Carleton M, & Lieberson R (2004). The transition to coparenthood: Parents’ prebirth expectations and early coparental adjustment at 3 months postpartum. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 711–733. DOI:10.10170S0954579404004742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna JJ, Ball HL, & Gettler LT (2007). Mother-infant cosleeping, breastfeeding and sudden infant death syndrome: What biological anthropology has discovered about normal infant sleep and pediatric sleep medicine. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 50(45), 133–161. 10.1002/ajpa.20736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA, & Levandoski LJ (2007). The 24-hour sleep patterns interview: A pilot study of validity and feasibility. Behavioral Sleeping Medicine, 5, 297–310. 10.1080/15402000701557441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileva-Seitz VR, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Battaini C, & Luijk MPCM (2017). Parent-child bedsharing: The good, the bad, and the burden of evidence. Sleeping Medicine Reviews, 32, 4–27. 10.1016/J.SMRV.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PM, & Commons ML (2010). The benefits of attachment parenting for infants and children: A behavioral developmental view. Behavioral Development Bulletin, 16(1), 1–14. 10.1037/h0100514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JA, Sadeh A, Wiegand B, How TH, & Goh DYT (2010). Cross-cultural differences in infant and toddler sleep. Sleeping Medicine, 11(3), 274–280. 10.1016/J.SLEEP.2009.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos KD, Youngclarke D, & Anderson JE (2007). Infant and child development parental perceptions of sleep problems among cosleeping and solitary sleeping children. Infant and Child Development, 16, 417–431. 10.1002/icd.526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Respironics/Mini Mitter Actiwatch instruction manual: Actiwatch communication and sleep analysis software (Version 5.0) Bend OR; 2005. Author,. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Sharkey KM, & Carskadon MA (1994). Activity-based sleep-wake identification: An empirical test of methodological issues. Sleep, 17, 201–207. 10.1093/sleep/17.3.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salm Ward TC, Robb SW, & Kanu FA (2016). Prevalence and characteristics of bedsharing among black and white infants in Georgia. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(2), 347–362. 10.1007/s10995-015-1834-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M, Park H, & Greenfield PM (2014). Infant sleeping arrangements and cultural values among contemporary Japanese mothers, 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M, & Teti DM (2018). Infant sleeping arrangements, social criticism, and maternal distress in the first year. Infant and Child Development. Wiley Online Library,. 10.1002/icd.2080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifer R (2005). Who should collect our data: Parents or trained observers? In Teti DM (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in developmental science (pp. 123–137). MA: Blackwell: Malden. [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, & Crosby B (2012). Maternal depressive symptoms, dysfunctional cognitions, and infant night waking: The role of maternal nighttime behavior. Child Development, 83, 939–953. 10.1111/j.1467-624.2012.01760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, Crosby B, McDaniel BT, Shimizu M, & Whitesell CJ (2015). Sleep and development: Advancing theory and research: X. marital and emotional adjustment in mothers and infant sleep arrangements during the first six months. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 80(1), 160–176. 10.1111/mono.12150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, & McGourty S (1996). Using mothers vs. trained observers in assessing children’s secure base behavior: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Child Development, 67, 597–605. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01753.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, Shimizu M, Crosby B, & Kim B-R (2016). Sleep arrangements, parent-infant sleep during the first year, and family functioning. Developmental Psychology, 52(8), 1169–1181. 10.1037/dev0000148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkovich E, Bar-Kalifa E, Meiri G, & Tikotzky L (2018). Mother–infant sleep patterns and parental functioning of roomsharing and solitary-sleeping families: A longitudinal study from 3 to 18 months. Sleeping: Journal of Sleeping and Sleeping Disorders Research, 41(2), 1–14. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Xu G, Liu Z, Lu N, Ma R, & Zhang E (2013). Sleep patterns and sleep disturbances among Chinese school-aged children: Prevalence and associated factors. Sleeping Medicine, 14, 45–52. 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthman CM (2011). Developmental cultural ecology of sleep. In El-Sheikh M (Ed.), Sleep and development (pp. 167–194). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof.oso/9780195395754.003.0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]