Abstract

The majority of clinical trials currently and historically do not include older adults or non-white participants. While more women are being recruited, their numbers are still limited. It is very hard to interpret trial results and apply them to older adults when their participation in clinical trials is limited.

The focus of this article is the lack of clinical trial participation by persons of diverse races and ethnicities and the presentation of a model infrastructure grounded in community engagement that is proving to be effective in increasing the interest and participation of older African Americans in research.

The Issue

The majority of clinical trials currently and historically do not include older adults or non-white participants. While more women are being recruited, their numbers are still limited. It is not uncommon for clinical trials to exclude those who are over 65 or who have multiple medical problems or disabilities. They often exclude those who have cognitive impairment or may have limited life expectancy. Many trials avoid those that live in nursing homes and some exclude those who live in assisted living facilities.1 This is essentially the entire patient population we see as geriatricians. It is very hard to interpret trial results and apply them to older adults when their participation in clinical trials is limited.

Importantly, and the focus of this article, is the lack of clinical trial participation by persons of diverse races and ethnicities and the presentation of a model infrastructure grounded in community engagement that is proving to be effective in increasing the interest and participation of older African Americans in research.

The lack of diversity in clinical trials was highlighted with the recent accelerated approval of Aducanumab, which was tested in an international trial that did not enroll any adults over the age of 85. It also included only 0.6% or 19 Black people, 3% Latinx participants and .03% or 1 Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander participant.2 The Asian participants were primarily recruited from their study arm in Japan. We know that Alzheimer’s disease (AD) impacts African-Americans and Latinx patients at rates that are two times and one and a half times higher respectively, yet this drug was approved without adequate participation of these groups in the clinical trial.

How can a drug get approved when the clinical trial does not even include the people who are most impacted by AD?

Many organizations and funders have recognized the lack of older, diverse adults in clinical trials and have issued guidelines and directives for researchers and industry to follow. The lack of older adults in clinical trials has been addressed formally by organizations such as the International Conference for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. It states that there is “no good basis for the exclusion of patients on the basis of advanced age alone, or because of the presence of any concomitant illness or medication, unless there is a reason to believe that that concomitant illness or medication will endanger the patient or lead to confusion in interpreting the results of the study. Attempts should be made to include patients over 75 years of age and those with concomitant illness and treatments.” 3

The NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 established Policy and Guidelines on the inclusion of Women and Members of Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research, which states that the Director of the NIH shall ensure that women and members of minority groups are included as subjects in each research project. The NIH must establish guidelines that specify the circumstances under which such inclusion is inappropriate; the manner in which trials are required to be designed and carried out must be specified; and guidelines have to specify the operation of outreach programs. 4

Despite these guidelines from NIH, there is still more work that needs to be done to improve diversity across several disease states in NIH funding categories. Table 1, Diversity Across Disease States, illustrates that as recently as 2021, inclusion is still very low across disease states, especially Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias and neurodegenerative diseases.

Table 1-.

Indicates the inclusion statistics across racial groups in NIH funding categories. https://report.nih.gov/RISR/#/

| Diversity Across Disease States | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean % Selected NIH Funding Categories | ||||

| NIH Inclusion Statistics Report 2021¹ | ||||

| African American | White | Hispanic/Latino | Not Hispanic/Latino | |

| Aging | 9% | 75% | 2% | 95% |

| ADRD | 6% | 80% | 3% | 95% |

| Cancer | 6% | 75% | 3% | 93% |

| Diabetes | 9% | 67% | 6% | 91% |

| Neurodegenerative | 5% | 82% | 3% | 93% |

The issue was magnified with the release in April 2022 of the FDA’s Diversity Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants from Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Subgroups in Clinical Trials.5 Sponsors are now required to submit a recruitment plan to the FDA early on in their development process that indicates how they will ensure diversity in recruitment. This is a critical step that will help ensure that future medications and devices have been trialed in the broad and varied populations of people that use them.

The Challenge for Academic Medical Centers

Academic medical centers (AMCs), where most of us have trained and many of us work, are typically the sites where clinical research is conducted, but their relationships with the communities they serve are often impacted by decades of mistrust and fear, based on patient experiences.

Most of the major AMCs in the U.S. are in urban areas that are often in low income, low resource areas where patients are seen in resident clinics rather than as private patients, creating a dual standard of care. Patients are frequently part of the teaching service, and many patients feel their health concerns are not heard or considered. The shifting continuity of care in teaching clinics and clinical services can add to the disparities of care.

Hospital staff may not live in the same neighborhood as the urban footprint of the AMC, which can contribute to a limited understanding of the surrounding communities and the patients seen in their clinics. Similarly, a lack of knowledge of our patients also impacts the types of research questions we might consider when thinking about a research project. Further, these patients may not see the AMC as supportive of their communities relative to job recruitment, contracts with local businesses and advocacy around economic development.

If we are not providing high-quality care to these patients, considering their health needs in research plans or supporting their communities, is it exploitation when we recruit them just to meet recruitment goals for our studies?

A “check the box for diversity” approach is very common in clinical trials and can be perceived by communities as superficial and does not convey a genuine interest in the participants or a real intent to enroll participants from traditionally underrepresented groups.

Researchers must develop methods for having community conversations with potential participants to find out what approaches to clinical research work best for them and which health issues are most important.

In our work at SUNY Upstate Medical University (SUNY Upstate), we have adopted the perspective that we, as researchers, should not “take before asking.” This requires that we ask questions and learn as much as we can about the community and potential trial participants. We just cannot go into a community and ask for them to sign up for a clinical trial without understanding their needs and concerns. Further, we focus on the importance and value of engaging diverse members of the community in defining research questions and ensuring that our methods and recruitment protocols address community priorities, interests and practical needs. We also follow the principle that we have to “give before you take.” We have to develop relationships and a sense of mutual trust that indicates a commitment to the communities we serve. I have been asked by many colleagues over the years to help them “get into” a black church or barbershop just so that they can meet their recruitment goals, which is clearly an exploitative approach.

The more that is needed from participants for a particular clinical trial, the more the researchers involved need to know and understand the people they want to recruit and their communities. A clinical trial that is multi-year or requires multiple visits or invasive procedures needs even stronger levels of trust and stronger relationships between the researchers and the community to reach diversity goals.

Traditionally, researchers and their teams develop a hypothesis and a research protocol based on their interests and then begin to recruit, frequently without a plan that will lead to the successful enrollment of older adults from diverse backgrounds.

We take the reverse approach at SUNY Upstate by first finding out what health care concerns are important to the community, and from that developing a series of talks on subjects of interest incorporating, as appropriate, the role of research in addressing a health issue. Topics range from what is normal aging and memory loss to the importance of monitoring medications and even wills and health care proxies. We also go further to make referrals for primary care visits or geriatrics assessments. In short, we begin by addressing what our communities and individuals need, weaving in frank discussions about research and its importance in improving the care we provide.

Barriers to Participation

Potential barriers or disincentives to the participation of diverse populations in research range from research design to recruitment protocols, screening methods, outreach materials, and lack of transportation support. Several examples follow.

The usual methods for advertising a clinical trial such as flyers, may not be useful for communicating in all communities. Flyers may be written in a language that isn’t accessible to some older adults, use terms unfamiliar to a lay public, and have limited reach to those with limited mobility, especially during the pandemic. Many older adults are also not familiar with the term clinical trial, and research is often a pejorative word that conjures up images of guinea pigs or pain.

The Mini Mental State Exam is still used for screening in many clinical trials for AD, even though we have known for years that this tool, as well as others, are not accurate in non-white populations, for those who have low educational attainment or whose primary language is not English.

Researchers need to have an understanding of the language and culture of the communities they want to involve. One of our community partners mentioned that her organization serves people from 22 different countries who speak different Spanish idioms.

These examples highlight the challenge of translating consent forms, flyers and recruitment materials for diverse participants. Some potential participants may also have limited literacy in their primary language. Research centers may not have clinical trial staff and raters that speak languages other than English, making it a challenge to administer cognitive and other assessments. It is also not unusual for clinical trial inclusion criteria, especially those for AD, to exclude participants whose primary language is not English.

Access to healthcare or to the research site can also be a challenge, even for those who live close to that research institution. Potential participants may not feel they can participate in a clinical trial sponsored by the same AMC where they do not feel comfortable seeking medical care.

When researchers think about protocol development, we have to consider issues that are important to potential participants such as the timing and number of study visits. These factors can be a challenge for working participants who do not have benefits such as paid sick or personal time. Some trials require a “study buddy” who may be working or have responsibilities that make it hard for them to accompany the participant to the study visit. Potential participants may also have significant roles in childcare for their families or may continue to work past traditional retirement ages, which limits their ability to participate in a clinical trial with study visits during the day. Study visits need to be offered on flexible schedules that may be outside of traditional business hours.

Researchers might also assume that everyone has a smart phone or a tablet with internet access to enter data or complete surveys. Cellphones and monthly internet access may be cost prohibitive to many people and access to quality internet can be limited in urban as well as rural areas. Some older adults only have landlines or a flip phone, at best.

Support for transportation is also important, since car ownership is not universal and some potential participants may rely on public transportation which itself can be limiting. One study team we assisted with recruitment hired vans to bring participants to study visits, which had a positive impact on meeting their diversity recruitment goals.

Model Infrastructure for Increasing Recruitment Equity

Working with a team at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai School led by Co-PI Mary Sano, PhD, we received a grant from the National Institute on Aging for a Recruitment Accelerator for Diversity in Aging Research, Cognitive Loss and Dementia, or RADAR.

The goal of RADAR is to create a model infrastructure for increasing the recruitment and retention of diverse participants into cognitive and aging research. The focus at SUNY Upstate’s site is on increasing the participation of African Americans in clinical trials.

The RADAR model has two central components. The first is new position called the Community Research Liaison (CRL). The CRL fosters an environment of trust and mutual respect among community members and connects the community and research partners through the second component, the research accelerator, to maximize participation. The research accelerator is a diverse group of research, clinical and lay stakeholders who provide researchers early input to move their science in the right direction for diverse participation with feasible study design and protocol development that address key issues of equity, recruitment and retention.

Community Research Liaison

Consistent with our fundamental principle of community engagement, the position description for the CRL was based on input from community members and community partners who helped us create a position that is responsive to their needs. The qualifications emphasized were experience with community outreach and/or community organizing and excellent interpersonal and communication skills, not a knowledge of research. We were able to identify a person who has deep ties to the community, who knows the neighborhoods, the people and the issues and who is well positioned to serve as a bridge between these neighborhoods and SUNY Upstate researchers.

We developed a curriculum for our CRL that includes basic information about research to facilitate their ability to respond to general research questions, help with recruitment and communicate effectively with researchers. The CRL is not a researcher and does not determine trial eligibility or obtain consent.

Our funding coincided with the initial wave of the pandemic, so we had to shift our outreach activities outdoors as much as possible. Our CRL began in-person relationship building in a public housing development that is right across the street from SUNY Upstate. She called her sessions ‘coffee and a bench’ where she held informal gatherings and conversations that were not necessarily about research. In fact, we have focused most of our initial outreach on listening and understanding what concerns people have about their health. Our CRL brings along small giveaways that are branded with Upstate Geriatrics so community members can begin to associate us with community outreach.

Our CRL’s primary focus has been to build relationships between Upstate and members of the community focusing not just older adults but also their adult children and caregivers as important members of the care team. Using our “ask before you take” approach, our CRL has met with a variety of people in the community which, as noted, has led to the development of a range of talks on topics of interest to the community. Names of those interested in hearing more about research are collected and our CRL follows up to answer any questions and, as indicated, refer them to our clinical trials team. Figure 1 provides images from one community outreach event.

Figure 1-.

Photographs taken at various community outreach activities led by our CRL.

Research Accelerator

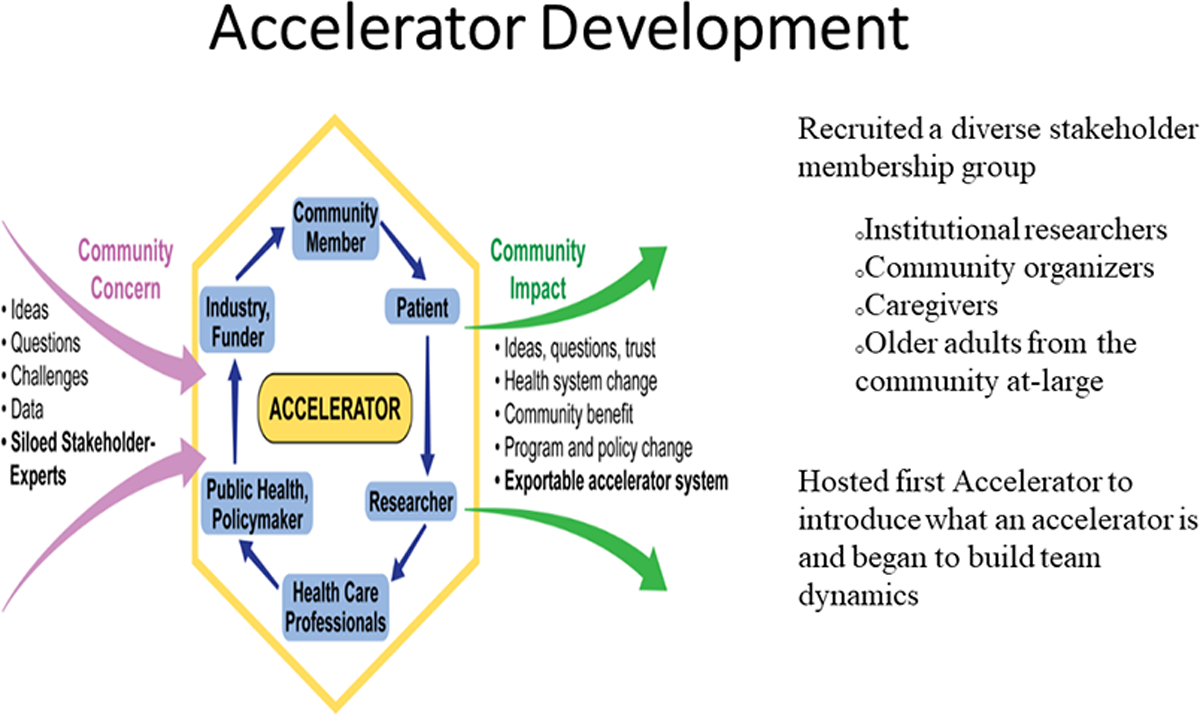

The second component of the RADAR model is the research accelerator. Our accelerator consists of a carefully selected group of researchers and clinicians along with community organizers, faith-based leaders, geriatrics service providers, caregivers, and lay older adults from the community. The accelerator was developed as a dynamic way for researchers to bring ideas, questions and challenges or data for review by accelerator members. This process helps facilitate trust, ideas and additional questions for the researcher to address.

Figure 2-.

Explains the development and function of the research accelerator at SUNY Upstate Medical University.

While the accelerator reviews studies at several stages of development and implementation, our goal is to have researchers bring early research ideas and preliminary project designs to the accelerator for review so that ideas and protocols are developed with a community perspective early on to facilitate recruitment, help avoid unattended actions or consequences and get community buy-in.

Our first accelerator meeting was held without any presenting researchers to build team dynamics and review responsibilities. We wanted to make sure community members felt comfortable talking with the accelerator’s researcher members and that all felt equally valued. We make sure every member has a chance to talk during meetings and all accelerator members are referred to by their first name, even avoiding titles among researchers.

Researchers who request an accelerator review provide written materials on their study in advance of meetings for accelerator member review. They then present their projects, recruitment plans and materials at an accelerator meeting using lay language, without acronyms. Following this presentation, the researcher leaves the meeting and accelerator members review and discuss the information and materials provided, and put forth their ideas and recommendations for changes that may facilitate diversity goals. A written report is generated based on this input, which is shared with the researcher.

Impact and Sustainability

Our CRL started in July 2021 and has already had a significant impact. We currently have five active recruitment projects, four funded by NIH. The CRL’s recruitment and retention activities are being budgeted into three R01 applications. We have completed three accelerator reviews with more in the pipeline. One project the CRL assisted with recruitment was not doing well in recruiting African Americans. At six months they had only 11 referrals and none were African-American. Once our CRL was involved, the total number of people referred for screening went up to 35, all of whom were African-American and 37% of whom were enrolled in the study. This illustrates that when you involve someone like a CRL who is committed to and has built trust within a community, recruitment can be greatly facilitated.

We are now determining our markers of success and are in the process of a formal evaluation of our work. The NIA grant runs through the end of November 2022. Many innovative projects start on soft money and cannot be sustained once the funding has ended. This adds to the sense of distrust in communities that see several years of work that generates interest and activity, only to have it all end. We are working to prevent this from happening with our RADAR project by developing a sustainability plan.

Our goal is to make the RADAR model part of SUNY Upstate’s research infrastructure, available to all researchers across the University and incorporated into their grant application and industry clinical trial budgets as recruitment and retention expenses. We are developing a pricing structure for accelerator activities and the CRL’s recruitment work. We believe that researchers and industry will be very interested in this model, given NIH and FDA guidance and requirements.

We are also continuing to enhance our CRL and accelerator methods, including the successful hand-off of individuals recruited by the CRL to researchers who may not understand the concept of community-based research. A successful hand-off process plays a significant role in a participant’s comfort in continuing their participation in a study over time, impacting retention rates. We also want to address the potential tension between the CRL’s relationship development and recruitment activities and timelines. It takes time to build relationships and trust which may not always align with enrollment timelines for a clinical trial.

We are also looking deeper into how to address structural research barriers. For example, a challenge especially for AD trials is that eligibility is typically based on a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or early AD. Yet many African Americans are diagnosed at a later disease stage and are not eligible for participation. Knowing this, our outreach work includes education about the early signs of cognitive impairment and the referral process for a comprehensive evaluation.

Finally, our plans over time are to extend the reach of our model to include Latinx, New American, Asian, and other populations by hiring CRLs from these communities.

The lack of older adults from diverse backgrounds participating in clinical trials is a complex issue and substantial changes need to be made in approaches to clinical trial development and recruitment that have been in place for many decades. The new FDA directives will motivate researchers and pharmaceutical companies to approach this issue in new ways so that their drugs and devices can be approved. Similarly, NIH will look for applications that address diversity goals and effective recruitment methods. One of the deliverables of our NIH grant is the development and dissemination of tools and manuals for accelerator development and CRL training to allow the model to be replicated at other institutions interested in using a community-based to address the lack of diversity in clinical trials.

We are confident that the RADAR model, with its CRL and research accelerator, is an effective approach for engaging diverse communities and increasing their representation in clinical trials. AMCs are uniquely positioned to address these issues and provide the leadership that is needed to meet this important challenge.

Key Points.

Older adults and non-white participants are not well represented in clinical trials.

The FDA now requires sponsors to submit a recruitment plan that indicates how they will ensure diversity in recruitment.

This article outlines a model infrastructure grounded in community engagement that is proving to be effective in increasing the interest and participation of older African Americans in research.

Why does this paper matter?

The majority of clinical trials for drugs and devices in this country have not included adequate representation of older adults and non-white participants. Many non-white participants have either been exploited or excluded from research studies. This has created a justifiable mistrust among some non-white older adults, leading to a reluctance to participate in research studies. In addition, clinicians may feel challenged when they have to make clinical decisions that have not been tested in the patient populations in their practices. While there has been much discussion about these disparities in clinical research, few solutions have been offered to address this ongoing problem.

Using a Recruitment Accelerator for Diversity in Aging Research, Cognitive Loss and Dementia (RADAR), we developed a model infrastructure, focusing on older African Americans, using a Community Research Liaison to foster an environment of trust and mutual respect between community members and researchers. We created a Research Accelerator as a dynamic way for researchers to bring their projects for review, so that protocols are developed with a community perspective to facilitate recruitment and help avoid unattended actions or consequences. Similar programs can be offered by academic medical centers as a means to improve diverse recruitment and retention in aging research.

Acknowledgements:

2. This project was funded by the National Institute on Aging.

Mary Sano, PhD and Sharon A. Brangman, M.D., Co-PIs.

Research Team:

Mt. Sinai- Shehan Chin, Crispin Goytia, Judith Neugroschl, Monica Rivera Mindt, Margaret Sewell, Mari Umpierre.

Recruitment Partners- Mike Splaine, Jennifer Vasconcellos.

Upstate Medical University- Sarah McNamara, Kathy Royal, Nancy Smith.

Sponsor’s Role: This project was funded by the National Institute on Aging, which had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Dr. Brangman discloses the following conflicts of interest:

Advisory Board: Acadia, Biogen, Eisai, Genentech-Roche

Clinical Trials: Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study, Biohaven, Hoffmann-LaRoche, Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Vivoryan Therapeutics.

References

- 1.Zulman DM, Sussman JB, Chen X, Cigille CT, Blaum CS, Hayward RA. Examining the evidence: a systematic review of the inclusion and analysis of older adults in randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med 2011; 26(7): 783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manly JJ, Glymour MM. What the Aducanumab Approval Reveals About Alzheimer Disease Research. JAMA Neurol 2021;78(11):1305–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherubini A, Del Signore S, Ouslander J, Semla T, Michel P Fighting Against Age Discrimination in Clinical Trials. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2010. Sep; 58(9):1791–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NIH Policy and Guidelines for the Inclusion of Women and Minorities in Clinical Research https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women-and-minorities/guidelines.htm. Accessed 08/11/2022.

- 5.Diversity Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants from Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Populations in Clinical Trials https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/diversity-plans-improve-enrollment-participants-underrepresented-racial-and-ethnic-populations. Accessed 8/28/2022.