Summary

Maintaining corneal health and transparency are necessary pre-requisites for exquisite vision, a function ascribed to stem cells (SCs) nestled within the limbus. Perturbations to this site or depletion of its SCs results in limbal SC deficiency. While characterizing a murine model of this disease, we discovered unusual transformation phenomena on the corneal surface including goblet cell metaplasia (GCM), conjunctival transdifferentiation, and squamous metaplasia (SQM). GCM arose from K8+ differentiated conjunctival epithelial cells when the limbus was breached and was exacerbated by neovascularization. Regions within the cornea that harbored newly transformed K12+ epithelia were void of blood vessels and GCs, suggesting that the cornea also initiated a self-repair program. Knowledge of the intrinsic circuits that contribute to cell identity change in lineage-restricted epithelia will be invaluable for designing new therapeutics for patients with blinding corneal disease.

Keywords: ocular surface, stem cells, limbus, cornea, conjunctiva, epithelial plasticity, goblet cell metaplasia, squamous metaplasia, transdifferentiation, limbal stem cell deficiency

Highlights

-

•

GCM arises from mature K8+ conjunctival epithelia when the limbus is breached

-

•

Corneal neovascularization promotes goblet cell metaplasia

-

•

Conjunctival epithelia can transdifferentiate into K12+ corneal epithelia in LSCD

-

•

SQM is a late entity that manifests on the corneal surface with disease chronicity

In this article, Di Girolamo and colleagues characterized plasticity of ocular surface epithelia using a clinically relevant mouse model of limbal stem cell deficiency. They show three types of transformations including goblet cell metaplasia, transdifferentiation, and squamous metaplasia that are initiated by limbal dysfunction and regulated by corneal neovascularization.

Introduction

The ocular surface epithelium is non-keratinized and stratified and spans the eyelid margin (mucocutaneous junction), palpebral, forniceal, and bulbar conjunctiva, limbus, and cornea. Both conjunctival and corneal epithelia (principally marked by keratins K13 and K3/12, respectively) arise from a primordial PAX6+ ectoderm-derived cell, after which the progeny deviate into separate lineages with distinct roles (Wei et al., 1993). Conjunctival epithelial stem cells (SCs) are considered bipotent, giving rise to squames and goblet cells (GCs) (Pellegrini et al., 1999; Wei et al., 1997) as well as columnar and cuboidal cells that take up residence in the same location. However, to date, there are no definitive biomarkers for identifying these cells with high fidelity. This is unlike limbal epithelial SCs (LESCs), which can be discriminated by their K14 (Lobo et al., 2016) and K15 (Altshuler et al., 2021; Nasser et al., 2018) content, as well as their expression of other markers (Di Girolamo, 2015). Moreover, a specific anatomical niche for conjunctival SCs is yet to be found; rather, they are thought to be distributed throughout the bulbar, forniceal, and mucocutaneous junction (Nagasaki and Zhao, 2005; Pellegrini et al., 1999; Wirtschafter et al., 1999). K8 is an interesting biomarker because immunoreactive cells are found in the human superficial conjunctival epithelium (Krenzer and Freddo, 1997) as well as through all layers of mouse (Zhang et al., 2008) conjunctiva. Yet, others have documented K8 predominantly in human basal limbal epithelia (Merjava et al., 2011), implying that it serves as a LESC marker.

Under steady-state conditions, the limbus provides a physical and biochemical barrier that maintains epithelial identity within the corneal and conjunctival compartments, preventing cells on either side from mixing (Kubilus et al., 2017). Notably, when the limbus is severely damaged to the extent that its LESCs are depleted, as is the case in limbal SC deficiency (LSCD) (Deng et al., 2019; Rama et al., 2010), the barrier function imposed by this site is lifted, and a pathological wound-healing response referred to as “conjunctivalization” materializes, which is characterized by the invasion of an inflamed fibrovascular pannus that enshrouds the cornea and obscures vision. In the 80s, researchers propositioned that under these circumstances, the cornea could heal to a relatively normal phenotype (Danjo et al., 1987; Huang et al., 1988; Shapiro et al., 1981; Tseng et al., 1984). The authors of these reports referred to this as transdifferentiation, which is broadly defined as a cell’s ability to switch identity by generating a progeny of an alternative lineage, with both the original and newly spawned cells being otherwise normal (OKada, 1991). In those reports, conjunctival epithelia that covered the wound transitioned into a corneal-like epithelium; a phenomenon that was prevalent when neovascularization was suppressed. Moreover, the phenotypic and functional switch was thought to arise from cells sensing a foreign (corneal) microenvironment (Huang et al., 1988; Tseng et al., 1984). Notably, some researchers have refuted the conjunctival transdifferentiation theory in such settings (Moyer et al., 1996), while others provided indirect supportive clinical evidence (Dua et al., 2009).

Metaplasia is another transformation event that can arise in cells that have experience extrinsic perturbations from mechanical-, chemical-, or microbial-inflicted trauma or intrinsic chronic disturbances in organs with significant regenerative capacity such as the eye, skin, lung, and gut (Slack, 1986). The two main forms of metaplasia include squamous (Dotto and Rustgi, 2016) and mucosal, otherwise referred to as GC metaplasia (GCM) (Fahy and Dickey, 2010). Squamous metaplasia (SQM) of the cornea toward a dry cutaneous identity has been documented in ocular surface disease including dry eye, neoplasia, and pterygia (De Paiva et al., 2007; Dogru et al., 2003; Tole et al., 2001; Van Acker et al., 2021). Studying resected pannus specimens from patients with LSCD has also uncovered SQM as the second type of cell-identity change that arises in this disease, in which the epithelium displays decreased corneal PAX6 and K12 and increased K10 expression, indicative of a transition toward a cutaneous identity, consistent with SQM (Chen et al., 2010; Li et al., 2008a, 2008b).

Notably, patients with LSCD can also present with a pannus harboring numerous GCs (Espana et al., 2004), an occurrence that is especially prevalent when corneal neovascularization is heightened (Joussen et al., 2003). Yet, some individuals with this disease present with few, if any, GCs. This is mainly the case when SQM prevails (Li et al., 2008a). One question we asked is whether GCs trek into the cornea from their forniceal repository or whether they arise from a transformation event such as GCM, similar to the mucosal metaplasia that is prevalent in Barrett’s esophagus (Que et al., 2019) and airway diseases such as cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Fahy and Dickey, 2010). Although GCM has not been identified in the eye, including the ocular surface, NGF and FGF2 (two potent regulators of GC differentiation) can promote the conversion of K12+ corneolimbal epithelia into MUC5AC+ GCs in culture, results which defy the current and well-accepted dogma of stable lineage divergence between corneal and conjunctival epithelia but supports the notion that lineage-defined somatic cells have a level of “plasticity” and hence the ability to modifying stringent molecular programs that dictate their form and function.

Although SQM has been documented on the cornea in LSCD, it is still unclear whether conjunctival transdifferentiation occurs, and there is no indication that GCM develops in the same disease. We hypothesized that such transformations develop in epithelia that trespass into corneal territory, particularly after inflicting a severe injury that induces inflammation and neovascularization. Therefore, our goals were to determine when these phenomena arise, the cells from which they originate, and the conditions that encourage their identity switch. To this end, we employed an animal model of LSCD to show that three types of transformation can transpire on the corneal surface from conjunctival epithelia that transition into MUC5AC+ GCs and K12+ corneal-like and K10+ cutaneous epithelia. Documenting these curiosities will provide clues for delineating the pathogenesis of LSCD and improving treatment options for patients.

Results

LSCD induction, its histological, clinical, and phenotypic assessment

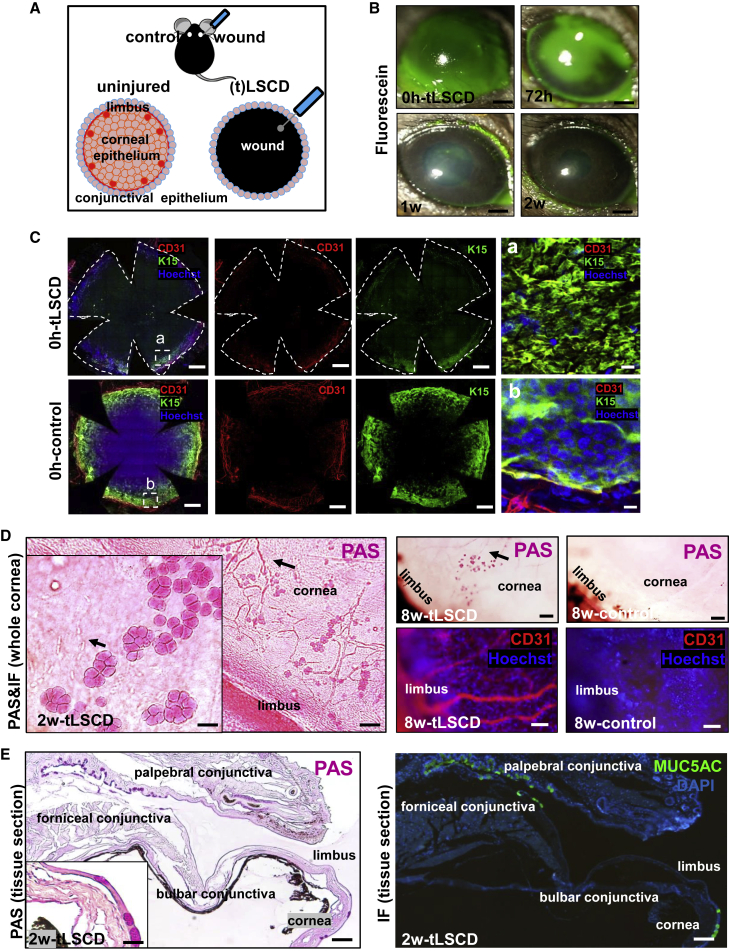

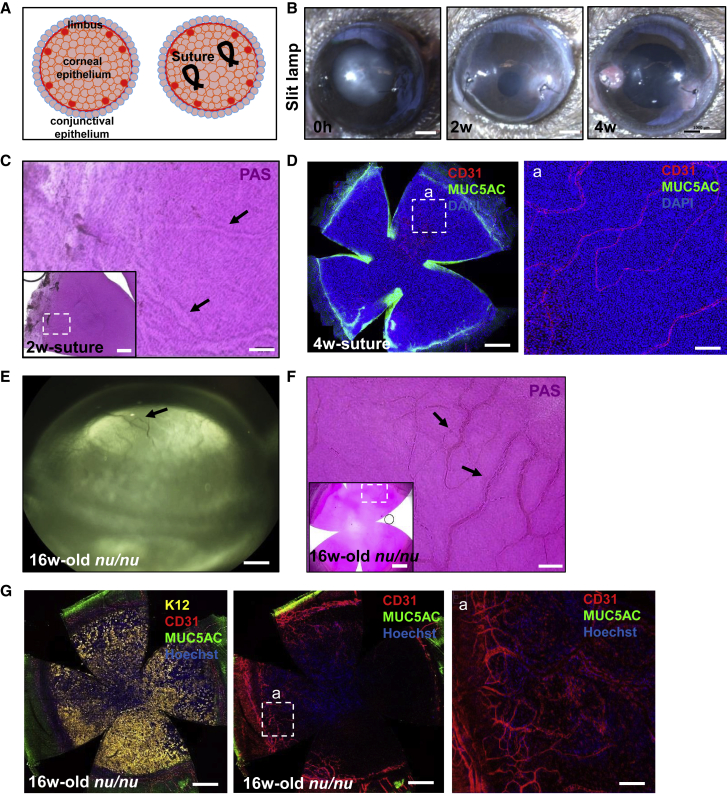

To assess the clinicopathological signs of total (t)LSCD after inflicting a corneolimbal epithelial debridement injury (Figure 1A), eyes were examined at regular intervals by Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining of histological sections (Figure S1A), slit-lamp microscopy (Figures 1B and S1B), and optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Figure S1C). These comprehensive assessments confirmed that the limbal and corneal epithelium was completely removed at 0 h post-tLSCD (Figures 1B and S1A–S1C). In addition, immunofluorescent staining for K15 with Hoechst confirmed the absence of basal limbal epithelium after the debridement (Figure 1C). Only, non-specific immunoreactivity developed in the stromal-epithelial basement membrane plane of the limbal margin compared with specific basal epithelial cell-associated K15 immunofluorescence in control corneas (Figures 1Ca and 1Cb, respectively). This was likely caused by excess proteins being deposited from vascular and other components after the severe injury. In this experiment, CD31 was used to mark the extent of limbal-stromal vascular plexus. A leukocyte infiltrate was detected at 24 h, after which the cornea was covered by a monolayer of epithelia at 48 h post-tLSCD (Figure S1A, arrows). GCs appeared at 2 weeks and persisted for 8 weeks (Figure S1A), confirming the progressive and stable pathological features of LSCD in this model. Wounded eyes developed corneal haze (Figure S1B) and early fluorescein uptake, which subsided once the defect re-epithelialized (Figure 1B). Mean epithelial thickness within the central cornea increased (p < 0.0001 at 0 h, p < 0.0001 at 1 week, and p = 0.0001 at 2 weeks, respectively) (Figure S1C). Stromal edema contributed to corneal thickening at 1 week post-wounding compared with control eyes (p < 0.0001); this subsided after 2 weeks (p = 0.2241) (Figure S1C).

Figure 1.

Induction of tLSCD and its histological, clinical, and phenotypical assessment

(A) Schematic representation on how tLSCD was induced in C57BL/6 mice.

(B) Corneas of live mice (n = 4/group) were monitored by slit lamp after instilling sodium fluorescein (green). Scale bars, 400 μm.

(C) Immunofluorescence for CD31 (red) and K15 (green) at 0 h post-tLSCD and control (n = 3/group). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Hatched white squares are magnified in (a) and (b) (right column), displaying the z-plane between stromal and basal epithelial layers. Scale bars, 400 and 20 μm (a and b).

(D) PAS-stained whole corneas (n = 3/group) indicating GC distribution and neovascularization (arrows) in LSCD. Inset (main panel) is a magnified view of GCs and blood vessels (arrows). Scale bars, 100 and 50 μm (inset). Whole corneas immunostained for CD31 (n = 3/group) confirming neovascularization (red). Scale bars, 50 μm.

(E) Representative images of corneal sections stained with PAS (n = 3/group) or immunostained for MUC5AC (n = 3/group) to identify GCs across the ocular surface in LSCD. Inset is a magnified view of GCs on the cornea. Scale bars, 50 and 20 μm (inset).

Histochemical and immunophenotypical assessments on whole flat-mount corneas and tissue sections confirmed re-epithelization of the corneal surface including the appearance of PAS+ GCs and stromal blood vessels at 2 weeks post-wounding, which persisted up to the 8-week monitoring period (Figure 1D). Notably, GCs and blood vessels appeared to co-locate (Figure 1D, arrows). Immunofluorescence on tissue cross-sections revealed MUC5AC+ cells in the same specimens, confirming their identity as GCs in the forniceal/palpebral conjunctiva as well as among the new epithelia that resurfaced the cornea (Figure 1E). No GCs were observed in the region spanning the bulbar conjunctiva and limbus (Figures 1E and S1D), suggesting that these cells did not migrate from their forniceal/palpebral cul de sac; rather, they transformed from conjunctival epithelial cells that invaded the inflamed and vascularized cornea.

qRT-RCR was performed to elucidate the gene expression profile of the epithelia covering the cornea. Corneal-specific K12 mRNA was decreased in tLSCD compared with healthy corneas at 1 (p = 0.0013) and 2 weeks (p = 0.0036) post-wounding (Figure S1E). This coincided with increased conjunctival-specific K8, K13, Igfbp7, and Muc5ac mRNA at 1 (p = 0.0042, p = 0.0015, p = 0.0027, p = 0.0048, respectively) and 2 weeks (p = 0.0046, p = 0.00001, p = 0.0089, p = 0.0019, respectively) after injury compared with contralateral controls. K14 mRNA was significantly elevated at 1 (p = 0.037) and 2 weeks (p = 0.023) after injury. No change in Ki67 mRNA was observed at either time point compared with controls, indicating that corneal resurfacing was not mediated by proliferating cells; rather, it was due to migrating epithelia.

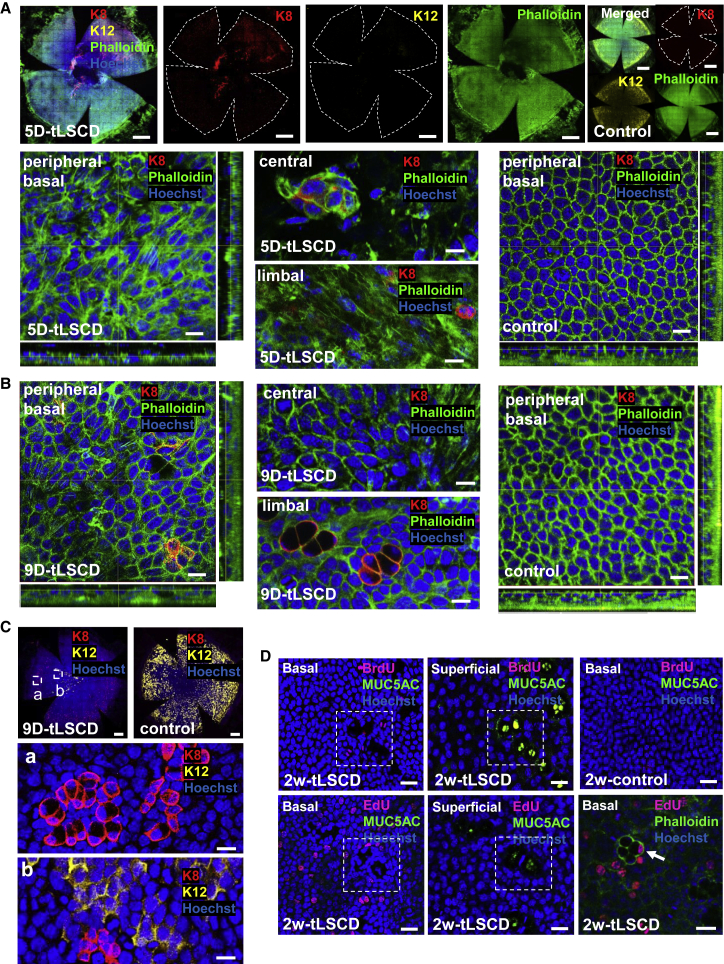

GCM after conjunctivalization

As expected, our model recapitulated many clinicopathological features that develop in patients with LSCD (Deng et al., 2019; Rama et al., 2010). Firstly, the corneal surface was incompletely sealed at 4 days post-injury, and the insurging conjunctival epithelia were K12− (data not shown). This pattern persevered at 5 days post-injury (Figure 2A); however, occasional K12+ epithelia appeared to cover the cornea, and some K8+ cells were observed within the stroma, some of which resembled infiltrating leukocytes (GeneCard: GC12M052897). This was concomitant with significant epithelial cell-shape change as determined by the remodeling F-actin cytoskeleton, indicative that these cells were indeed motile (Figure 2A; Videos S1 and S2; Table S1). Despite there being several reports that have identified GC clusters in uninjured control mice, their presence seems to be strain specific, i.e., numerous in BALB/c and few, if any, in C57BL6 (Pajoohesh-Ganji, Pal-Ghosh, Tadvalkar and Stepp, 2012; Pal-Ghosh et al., 2008). Our data are congruent with findings in black mice, which display no K8+ individual cells or indeed cell clusters in the central, peripheral, or limbal regions of normal corneas (Figures 2A and 2B, control panels; Videos S5 and S6), reminiscent of compound niches that are prevalent in control white mice. At 9 days post-injury, some K12+ epithelia or K12−/K8+ GCs were observed in the cornea, and the F-actin filament pattern returned to near normal (Figure 2B; Videos S3 and S4). Interestingly, K8+ cells were either small epithelia or larger goblet-like cells that formed aggregates (Figure 2Ca and 2Cb). No BrdU+/MUC5AC+ GCs were detected in conjunctivalized corneas at 2 weeks post-injury (Figure 2D, first row). Next, we employed a method that does not rely on antibody-antigen interactions, nor does it require denaturing nucleic acids to detect the incorporated nucleoside, as does BrdU. In this instance, very few, i.e., <0.001%, EdU+/MUC5AC+ were detected among a total of 41,212 ± 23,732 EdU+ cells over the same time frame (Figure 2D, second row), consistent with the notion that GCs rarely, if at all, proliferative (Pajoohesh-Ganji, Pal-Ghosh, Tadvalkar and Stepp, 2012).

Figure 2.

GCM and cell proliferation in tLSCD

(A and B) Immunofluorescence for K8 (red) and Phalloidin (green) and/or K12 (yellow) at 5 and 9 days post-tLSCD (n = 3/group). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars, 400 (whole corneas, top panels in A) and 20 μm (central, peripheral, and limbal basal layers).

(C) Immunofluorescence for K8 (red) and K12 (yellow) at 9 days post-tLSCD (n = 3/group). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Hatched white squares are magnified in peripheral (a) and paracentral (b) corneas. Scale bars, 400 (whole corneas) and 20 μm (a and b).

(D) Cell proliferation across the corneal surface (n = 3/group) after staining whole corneas for BrdU and MUC5AC, EdU and MUC5AC, or EdU and Phalloidin. Hatched white squares indicate the same regions within basal and superficial layers. Rare EdU+/MUC5AC+ GCs are magnified (bottom third panel, arrow). Scale bars, 100 μm.

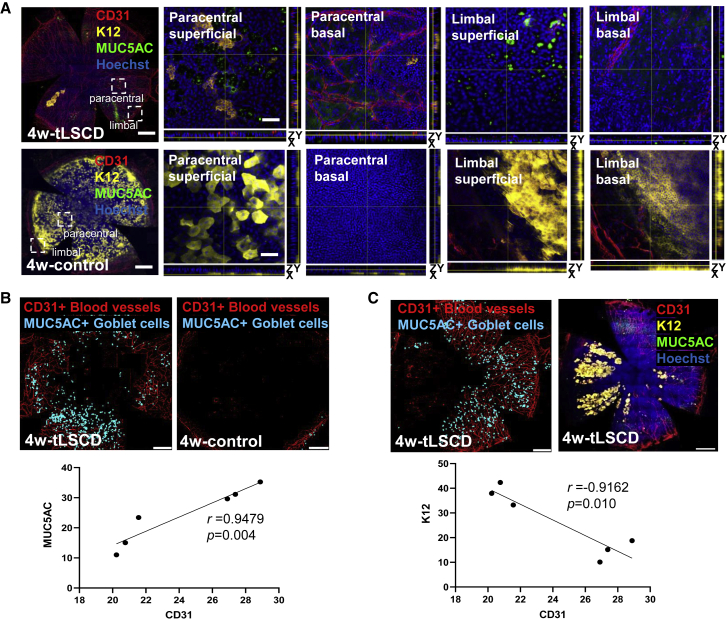

Transformation of conjunctiva into MUC5AC+ GCs or K12+ corneal epithelial cells

With time post-injury, more MUC5AC+ GCs emerged, along with a profound angiogenic response (Figures 3A and 3B). Also, K12+ corneal epithelia-like cells appeared (Figures 3A and 3C), which were morphologically different from their native counterparts because they formed circular clonal-like clusters within the basal to superficial epithelium. They eventually coalesced but were disconnected from the limbal boundary. These cells likely emanated from the conjunctival epithelium, which is not known harbor K12+ cells (Figure S2A), indicating that they entered a transdifferentiation program. Fluorescence intensity for K12, MUC5AC, and CD31 (Figure 3A) was profiled according to radial distance from the cornea’s apex. This analysis revealed decreased K12 concomitant with elevated CD31 and MUC5AC compared with controls in the central, peripheral, and limbal regions (K12: 15.14 versus 37.94, p < 0.0001; 18.78 versus 42.35, p < 0.0001; and 10.09 versus 33.25, p < 0.0001; CD31: 27.38 versus 20.23, p < 0.0001; 28.88 versus 20.76, p < 0.0001; and 26.90 versus 21.56, p = 0.0004; MUC5AC: 31.12 versus 11.03, p < 0.0001; 35.25 versus 15.05, p < 0.0001; and 29.60 versus 23.43, p = 0.1937, respectively). Consistent with our histological data (Figure 1), MUC5AC+ GCs positively correlated with CD31+ blood vessels in tLSCD (Figure 3B), while K12+ epithelial cell clusters in the same corneas negatively correlated with blood vessels and GCs (Figures 3C and S2B; Video S7), indicating that a protracted angiogenic response on the ocular surface may be the impetus for conjunctival epithelia to initiate an identity change. No new blood vessels or GCs were observed 5 days post-injury; however, neovascularization was detected in the peripheral cornea (Figure S2C, arrow), and faintly visible Alcian blue−/PAS+ GCs were occasionally observed near the limbal border at day 7 (Figure S2C, arrowheads), while many prominent Alcian blue+/PAS+ GCs were present in peripheral cornea at day 9.

Figure 3.

GCM in tLSCD

(A) Immunofluorescence for CD31 (red), K12 (yellow), and MUC5AC (green) at 4 weeks post-tLSCD (n = 3/group). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Hatched white squares are magnified in superficial and basal epithelial layers. Scale bars, 400 (first column) and 100 μm (second–fifth columns).

(B) Traces from representative CD31 and MUC5AC immunostained images were used to confirm a positive correlation. (n = 6, Pearson correlation).

(C) Traces from representative CD31 and K12 immunostained images were used to confirm a negative correlation. (n = 6, Pearson correlation).

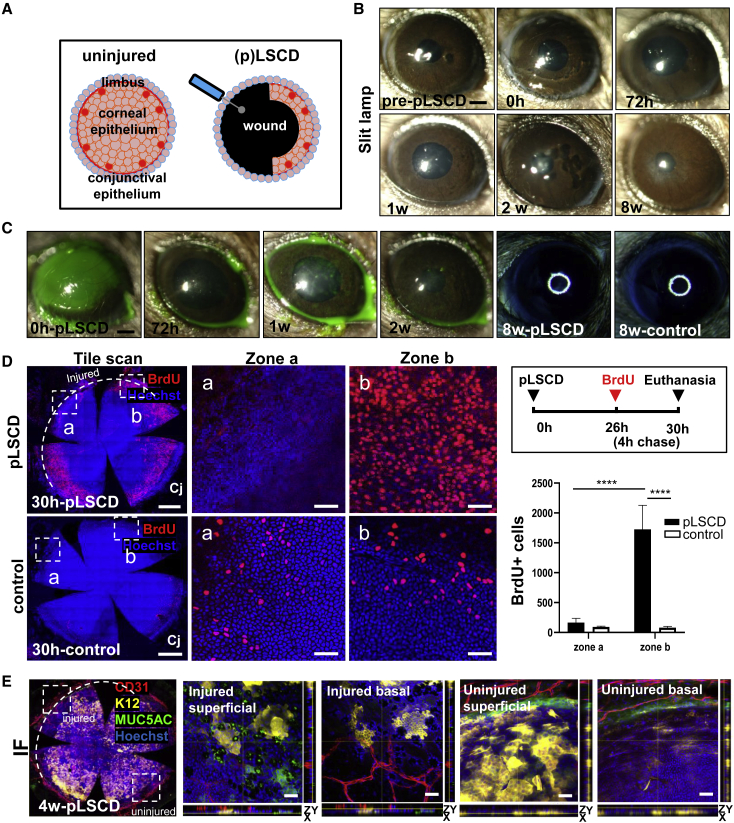

Clinical and phenotypical assessments of partial LSCD

To provide further evidence supporting the proposition that GCM develops when the limbal barrier is damaged, we inflicted partial (p)LSCD by debriding a 180-degree sector of corneolimbal epithelium (Figure 4A). Corneal opacity was detected up to 72 h post-wounding (Figure 4B), which regressed once the defect was resurfaced, after which corneal smoothness became comparable to control eyes (Figure 4C). Also, few, if any, BrdU+ cells were observed in the center of the injured zone, similar to what was observed in control corneas (Figure 4D, zone a), suggesting that the initial stage of conjunctivalization is characterized by cell migration. Notably, the lack of proliferation within the center of injured region was compensated by excess mitotic activity from adjacent corneolimbal epithelia (Figure 4D, zone b). In this model, MUC5AC+ GCs, K12+ epithelial patches, and CD31+ blood vessels were evident in the limbal/peripheral region of the injured sector at 4 weeks post-wound (Figure 4E) but were not detected in the adjacent unwounded zone. These newly arising MUC5AC+ GCs and K12+ epithelia were proximal to one another but did not co-localize, suggesting that the invading conjunctival epithelium assumed a level of plasticity. As expected, K12+ epitherlia were mostly confined to the intermediate and superficial layers of the uninjured peripheral and central cornea (Figure 4E). In contrast, atypical K12+ patches in the injured peripheral zone arose from basal epithelia. Upon computing these visual outputs, K12 expression decreased, concomitant with increased CD31 and MUC5AC immunoreactivity in the limbus and periphery of the injured region compared with the unwounded region (K12: 19.42 versus 35.49, p = 0.0005; CD31: 14.59 versus 11.99, p = 0.0327; and MUC5AC: 18.74 versus 13.02, p = 0.0006, respectively). These data suggest that sectorial limbal debridement and the subsequent regional angiogenic response is responsible for the GCM and transdifferentiation of conjunctival epithelia into K12+ cells.

Figure 4.

Clinical and phenotypical assessments, and cell proliferation in pLSCD mice

(A) Schematic representation on how pLSCD was induced in mice.

(B and C) Corneas of C57BL/6 mice (n = 4/group) were monitored by slit lamp after applying sodium fluorescein or visualized on a dissecting microscope for the corneal smoothness. Scale bars, 400 μm.

(D) Proliferation of corneal epithelia in pLSCD (n = 3/group) and the number of BrdU+ (red) cells between zones a and b, comparing pLSCD and control corneas. The hatched white arc represents the extent of the limbal injury. Scale bars, 400 (first column) and 100 μm (second and third columns). Bars in graph represent mean ± SD, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, Sidak’s multiple comparisons.

(E) Immunofluorescence for CD31 (red), K12 (yellow), and MUC5AC (green) at 4 weeks post-pLSCD (n = 3/group). The hatched white arc represents the extent of the limbal injury. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Hatched white squares are magnified in superficial and basal epithelial layers in injured and uninjured regions. Scale bars, 400 (first panel) and 20 μm (second–fifth panels).

Conjunctival epithelium does not transform during acute and chronic corneal neovascularization

The next question we asked is whether GCM develops in neovascularized corneas when the limbal boundary is left intact. For the acute model of neovascularization, two sutures were placed in the peripheral cornea (Figure 5A), which developed mild opacity around the stitches at 2 weeks and, occasionally, an ulcer at 4 weeks (Figure 5B). GCs were not detected in these corneas, despite the substantial angiogenic response at 2 and 4 weeks post-suture placement (Figures 5C and 5D). When one of the two sutures was accidently placed near the limbus, corneal neovascularization ensued with GCM. Notably, the second suture that was placed in the correct position triggered a vascular response without the emergence of GCs (Figure S3). Likewise, GCs were not detected in athymic mouse corneas (Figures 5E–5G), representative of chronic neovascularization. Therefore, GCM arises when the limbus is damaged.

Figure 5.

Neovascularization without GCM in suture-induced and nu/nu mouse models

(A) Schematic representation on how sutures were placed in the peripheral cornea to induce corneal neovascularization in C57BL/6 mice.

(B) Corneas of C57BL/6 mice (n = 6) were monitored by slit lamp. Scale bars, 400 μm.

(C) Whole corneas (n = 6) were PAS stained. The hatched white square is magnified in the main panel to showcase blood vessels (arrows). Scale bars, 50 and 200 μm (inset).

(D) Immunofluorescence for CD31 (red) and MUC5AC (green) at 4 weeks post-suture (n = 6). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Hatched white square is magnified. Scale bars, 400 (first panel) and 20 μm (second panel).

(E) Corneas of athymic nu/nu mice (n = 3) were monitored by slit lamp. Scale bars, 300 μm.

(F) Representative PAS-stained whole cornea from an athymic nu/nu mouse (n = 3). The hatched white square is magnified in the main panel to show blood vessels (arrows). Scale bars, 50 and 400 μm (inset).

(G) Immunofluorescence for K12 (yellow), CD31 (red), and MUC5AC (green) (n = 3). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Hatched white square is magnified in the third panel (a). Scale bars, 400 (first and second panels) and 20 μm (third panel).

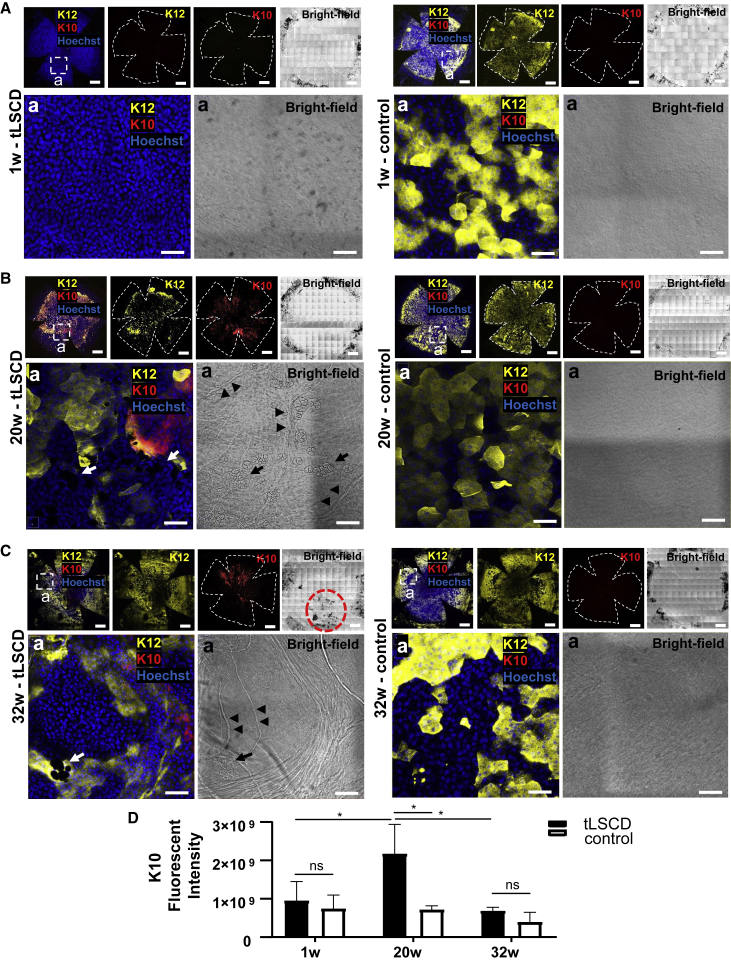

Transformation of conjunctiva into K10+ keratinocytes

SQM onset, progression, and cellular source are features that have not been properly characterized in tLSCD but have been detected (Chen et al., 2010; Li et al., 2008a, 2008b). Here, we demonstrated the absence of K10+ cutaneous-like epithelia in control corneas irrespective of age (Figure 6) and that few (if any) of these cells were present during the first week post-injury (Figure 6A). However, these cells were more frequently detected at 20 weeks after injury compared with controls (Figure 6B). Interestingly, K10 and K12 co-expression was observed at 20 and 32 weeks (Figures 6B and 6C), suggesting that skin-like keratinocytes manifest later in the disease process and are derived from K12+ epithelia. However, we cannot rule out that they also arose from K13+ conjunctival epithelia that invaded the cornea. This extended monitoring also suggest that GCM and corneal neovascularization persevere long term in this model (Figures 6Ba and 6Ca in tLSCD, arrows and arrowheads).

Figure 6.

SQM in tLSCD

(A–C) Immunofluorescence for K12 (yellow) and K10 (red), and bright-field images at 1, 20, and 32 weeks post-tLSCD (n = 3/group). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Hatched white squares are magnified in the lower panels to show GCs (arrows) and blood vessels (arrowhead). The hatched red circle indicates anterior synechia. Scale bars, 400 (top row) and 100 μm (bottom row).

(D) Immunofluorescence intensity for K10 comparing tLSCD to controls (mean ± SD, ns, not significant, ∗p < 0.05, Sidak’s multiple comparisons).

Discussion

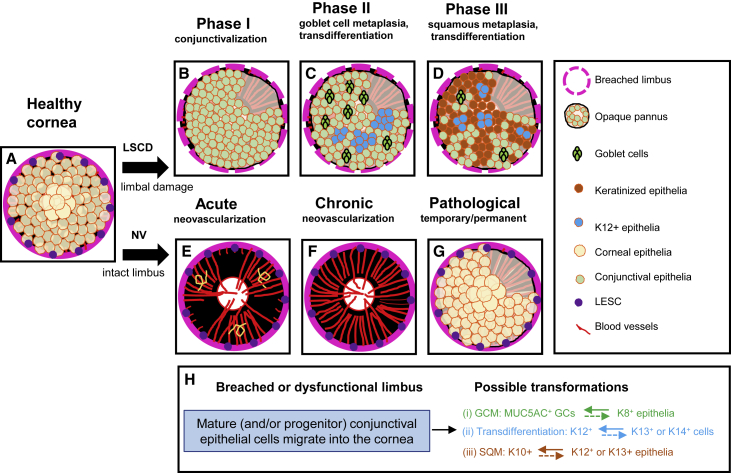

Herein, we used the wound-healing response that transpires in LSCD to identify and partially characterize rare and unusual phenomena within the cornea, namely GCM, SQM, and conjunctival transdifferentiation. To our knowledge, the mechanisms that govern GCM on the ocular surface have not been described as they have in other conditions like Barrett’s disease, where gastric intestinal cells replace esophageal squamous mucosa damaged by chronic reflux (Que et al., 2019), and in airway diseases including cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Fahy and Dickey, 2010). Our investigation identified GCM in diseased murine corneas, where conjunctival epithelia transformed into genuine mucin-producing goblet-like cells. Alongside this pathological healing response, a second transformation reaction eventuated, including transdifferentiation of conjunctival epithelia into K12+ corneal epithelial-like cells (Figures 2, 3, and S2). A third form of identity change, namely SQM, was also observed in the same corneas (Figure 6). While the latter process is known to arise in ocular surface diseases, the timing for its initiation has not been clearly discerned, nor has it been recorded alongside two other transformation variants within the same diseased tissue.

Our first goal in deciphering when GCM occurs was to seek confirmation that GCs did not emigrate into the cornea from their native forniceal repository. Histological investigations unequivocally demonstrated that they did not travel with invading conjunctival epithelia (Figures 1E and S1D). This observation then raised an important question as to what cell type spawned their existence, i.e., whether all conjunctival epithelia undergo GCM, or whether there is a select population with this capability? Although it is known that conjunctival SCs are bipotent (Pellegrini et al., 1999; Wei et al., 1997), this activity has not been clearly delineated in vivo, perhaps because their location has not been pin pointed with accuracy and the paucity of biomarkers that specify these cells. Nonetheless, our observations are consistent with GCs morphing from K8+ cells. Certainly, the conjunctiva harbors cells that express this marker within the differentiated supbasal-superficial tiers, thereby potentially nullifying the proposition that GCs within a conjunctivalized cornea are derived from a stem/progenitor cell population. On the contrary, new K12+ cells arise from K8−, i.e., possibly K13+, K14+, or indeed other conjunctival epithelia (Figure 2C). Initially, they form circular aggregates (Figure 3C) that appear to arise from a basal cellular source (Figure 3A). In humans, GCM of the ocular surface has not been reported but is likely to manifest in diseases like LSCD. However, determining its prevalence is not a trivial undertaking because of technical, logistical, and ethical limitation. Rather, it is assumed that GCs surge into the cornea concomitant with invading epithelia as part of the conjunctivalization process (Tseng et al., 1984). A common clinical manifestation in patients with LSCD (Saidkasimova et al., 2005) and other keratopathies (Fraunfelder et al., 1977) is the occurrence of vision-obstructing corneal mucous plaques, which form when mucin, epithelial cells, and proteinaceous material coagulate and firmly adhere to the underlying corneal epithelium. Whether these plaques arise from GC over-stimulation, hyperplasia, or metaplasia is yet to be confirmed. Notably, GCs are not always detected in corneas of patients with LSCD (Fatima et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008a; Ohji et al., 1987; Sati et al., 2015). We speculate that their absence is related to disease cause, severity, stage, duration, and/or state of the microenvironment (Figure 7). We cannot draw any definitive conclusion about whether GCs partake in the repair process but suspect they play a bigger pathological role given their positive association with neovascularization and negative correlation with new K12+ corneal epithelial-like cells (Figure 3). A major limitation of our study was the lack of direct evidence to lineage trace the origins of GCs. In the future, alternative strategies should be considered with GC-labeling reagents (Kim et al., 2019) or mucin-targeting transgenics (Portal et al., 2017).

Figure 7.

Mechanism of GCM, SQM, and conjunctival transdifferentiation

(A) A healthy cornea depicting an intact limbus with full complement of LESCs and corneal epithelia.

(B) Upon injuring the limbus and/or removing resident LESCs to induce LSCD, the initial healing response is to rapidly resurface the cornea with conjunctival epithelial cells, which occurs concurrent with a vascular response (phase 1).

(C) Subsequently, GCs emerge from mature K8+ conjunctival epithelial cells, and K12+ cornea-like epithelia transdifferentiate from K13+ conjunctival epithelium (phase II).

(D) Features of SQM can also develop either from newly formed K12+ cells or from K13+ conjunctival epithelia that have invaded the corneal surface. However, this may be reliant on disease etiology, microenvironment signals, and/or the time since the initial insult (phase III).

(E–G) In a scenario where the cornea develops acute (E) or chronic (F) neovascularization without damage to the limbus and its SCs, GCM, SQM, and conjunctival transdifferentiation might not arise, and the epithelium maintains a corneal phenotype (G).

(C), (D), and (G) have a sector of cornea without epithelial coverage to enable visualization of the underlying vascular response.

(H) A breach in the limbal barrier facilitates invasion of K8+, K13+, and K14+ conjunctival epithelia or progenitor cells into the cornea (blue rectangle). Once on the cornea, three possible transformation outcomes can evolve, including (1) GCM, where MUC5AC+ cells arise from K8+ conjunctival epithelia (green arrow), (2) transdifferentiation, where K12+ cells form from K13+, K14+, or other conjunctival epithelia (blue arrow), and (3) SCM, where K10+ keratinocytes materialize from K12+ or K13+ cells (red arrow). It is also possible that newly transformed cells can revert to their original identity (colored hatched arrows); however, it remains to be confirmed whether this occurs on the cornea in LSCD.

Because corneal neovascularization is a prominent feature in LSCD (Lim et al., 2009), a process reliant on vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor Flt-1 (VEGFR1) (Joussen et al., 2003), anti-VEGF therapy could be used to improve the local microenvironment and modulate cell-identity changes. Blocking neovascularization in patients with LSCD by photochemical occlusion (Huang et al., 1988) or after applying bevacizumab (Avastin) in rabbits with limbal insufficiency induced transdifferentiation of conjunctival epithelium into cornea-like cells (Lin et al., 2010). This is an ancillary strategy worthy of considering for LSCD; however, the long-term consequences of such therapy need to be scrutinized. Given the strong positive correlation between GCs and CD31+ blood vessels in murine LSCD corneas (Figure 3) (Joussen et al., 2003), our second goal was to determine whether neovascularization alone promoted GCM. Here, we employed two models that spared traumatizing the limbus. In both the suture-induced acute model (Cursiefen et al., 2004) and in the athymic nu/nu mice, which spontaneously develop persistent corneal neovascularization (Kaminska and Niederkorn, 1993), GCM was not detected (Figure 5), suggesting that this process is not entirely reliant on a vascular response; rather, it arises when the limbal barrier is fractured (Figure 7). This paradigm was also tested in pLSCD (Figure 4), where cells invading the injured corneal sector changed identity, as they did in mice with tLSCD. There have been multiple lines of enquiry that provide evidence to support this posit. Corneas of destrin deletion (Dstncorn1) mice develop conjunctivalization including the appearance of GCs and neovascularization (Zhang et al., 2008), equivalent to the features that develop in our mice with LSCD (Figures 1 and 3). How do GCs arise in these mice without limbal involvement? Histological examinations demonstrated that the hyperplastic epithelium, which covered the ocular surface in these mice, had elevated K14 expression (Wang et al., 2001), a protein considered to label limbal precursors (Di Girolamo, 2015; Lobo et al., 2016; Park et al., 2019; Richardson et al., 2017). In this instance, the destrin deletion may have intrinsically altered LESC function, similar to the impairment observed in SCs of Pax6+/− mutant mice (Ramaesh et al., 2003). PAX6, WNT, and NOTCH are master controllers of cell identity, development, and function of ocular surface epithelia (Li et al., 2015; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2006; Ouyang et al., 2014; Vauclair et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2013). For example, conditional inhibition of canonical Notch signaling in K14+ conjunctival cells resulted in suppressed GC differentiation, failure to synthesize MUC5AC, and progressive SQM on the cornea (Zhang et al., 2013). In models of lung disease, Notch2 inhibition prevented GCM (Danahay et al., 2015), suggesting that this pathway could be targeted for therapeutic intervention. Overall, these reports support the notion that a vascular response alone is insufficient to trigger GCM; rather, this process occurs when the limbus is fragmented and/or is dysfunctional (Figure 7).

The second process we unraveled was conjunctival transdifferentiation into K12+ corneal epithelial-like cells (Figures 2, 3 and 4). This phenomenon has been reported on the cornea (Harris et al., 1985; Huang et al., 1988; Tseng et al., 1984), although its occurrence has been disputed (Huang and Tseng, 1991; Kruse et al., 1990; Moyer et al., 1996). Despite this controversy, we determined that it develops within the first few weeks after wounding, i.e., after the defect is sealed, persevering for up to 32 weeks post-injury (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and S2). Before doing so, we ensured the corneolimbal epithelium (including K15+ LESCs) was completely removed (Figure 1) and confirmed the absence of K12+ cells during the early phase of conjunctivalization (Figure 2A). Importantly, we also certified that there were no K12+ cells in the conjunctiva prior to wounding (Figure S2A), given reports that these cells can reside ectopically, at least in humans (Kawasaki et al., 2006). In addition, because compound niches are another source of K12+ and MUC5AC+ cells in mice (Pajoohesh-Ganji, Pal-Ghosh, Tadvalkar and Stepp, 2012), we searched for these structures to no avail (Figures 2A and 2B, panels with controls; Videos S5 and S6). The disparity between studies is potentially attributable to methodological, reagent, or strain-specific differences (Pal-Ghosh et al., 2008). Our findings do, however, raise important questions about whether transdifferentiation is transient or stable and reliant on the state of local microenvironment as is GCM, whether newly transformed cells behave like genuine corneal epithelia, and, if so, can they effectively reinvigorate the injured cornea long term? In attempting to answer these questions, we observed an atypical pattern of K12 distribution in LSCD corneas, along with morphological differences compared with epithelia found in healthy control corneas (Figures 2 and 3). These changes potentially attributed to the foreign environment they now find themselves in, and importantly, their dislocation from the limbal sanctum from which they would otherwise receive niche specific signals. Regions that spawned new K12+ corneal epithelial-like clusters developed less neovascularization and fewer GCs (Figure 3). Notably, a proportion of animals (Tseng et al., 1984; Vauclair et al., 2007) and indeed patients (Dua et al., 2009) with tLSCD can present with healthy central islands of corneal epithelium. Our data indicate that intrinsic homeostatic reparative programs are initiated but may be ineffective in the long term due to the severe pathology that persists (Figure 7). Transdifferentiation may also explain why there have been numerous reports of successful outcomes in patients and animals with LSCD that received conjunctival grafts (Ang et al., 2010; Di Girolamo et al., 2009; Ono et al., 2007; Sakimoto et al., 2020; Thoft, 1977).

SQM was the third transformation variant we identified. This process commonly arises in neoplastic lesions of the human cornea and conjunctiva (Dogru et al., 2003) and in dry eye disease (Chen et al., 2010; Li et al., 2008b; Murube and Rivas, 2003), where K12+ corneal epithelia undergo keratinization toward a cutaneous K10+ variant. Indeed, epithelia covering the cornea in patients with LSCD can undergo similar SQM, a transition linked with duration of the insult (Sati et al., 2015), as well as dry-eye-like symptoms that can develop in individuals with this condition (Schlötzer-Schrehardt et al., 2021) or the level of keratinization (Ohji et al., 1987). We observed this phenomenon in corneas with tLSCD in long-term monitoring of tLSCD, during which K10+ epithelia evolved, some of which co-expressed K12. This was concomitant with a drop in GC density, suggesting that disease chronicity established a dry microenvironment that promoted SQM (Figure 6).

In summary, our study systematically monitored and characterized three transformations that transpire in a clinically relevant animal model of severe corneal injury (Figure 7). First, GCM proceeded only when the conjunctival epithelium ventured into the cornea, a process that was encouraged by the vascular response that develops in LSCD (Figure 7C); however, corneal neovascularization alone was insufficient to entice this process (Figures 5 and 7E–7G). Second, conjunctival transdifferentiation into K12+ corneal-like cells was also triggered (Figure 7C). Notably, regions within the cornea that harbor new K12+ cells had fewer pathological features including blood vessels and GCs (Figure 3), implying that the cornea initiated a homeostatic tissue repair program. How sustainable this process is given the severity and chronicity of this disease and whether these new K12+ cells behave like typical corneal epithelia are questions that currently remain unanswered. Finally, we detected the development of a skin-like phenotype across diseased corneas with the appearance of K10+ epithelia from K12+ cells, suggesting that cells were transitioning from one cell type to another, an observation consistent with SQM (Figures 6 and 7D). The cornea, therefore, represents a unique location for multiple cellular trans-commitment events. Whether these transformations are transient, complete, and/or reversable was not ascertained (Figure 7H); however, suppressing neovascularization can decrease GC density (Lin et al., 2010), indicating that metaplasia can be reversed or minimized. Certainly, intestinal metaplasia can be reverted upon eradicating the causative microbial trigger (Graham et al., 2019). Unraveling the pathways through which the cornea attempts to self-resolve after enduring a severe injury could be harnessed toward devising innovative co-therapies for patients with LSCD to improve the longevity and outcomes of SC-based therapies.

Experimental procedures

Mice

Both male and female C57BL/6 mice (n = 156) for partial and total LSCD induction and suture-induced neovascularization, and athymic mice (BALB/c nu/nu) (n = 12) were housed under pathogen-free conditions and fed standard chow. Animal care and use also conformed with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. All procedures were approved by the University of NSW Animal Care and Ethics Committee (approval no. 20/59A) or the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Houston under protocol 16-044 (see details in supplemental information: mice, corneolimbal epithelial debridement wounds to induce partial and total LSCD, and suture-induced corneal neovascularization model).

Clinical, histological, and phenotypical assessment

For clinical assessment, eyes were imaged by slit-lamp microscopy (Nikon FS-3, Tokyo, Japan), OCT (Micron IV, Phoenix Technologies, New York, NY, USA), and SMZ800 dissection microscope fitted with a surgical light-ring (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) (see details in supplemental information: clinical assessment; fluorescein staining, corneal smoothness, and OCT biomicroscopy).

For histological, phenotypical, and molecular assessments, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation at specific time points post-wounding. Gold standard methods of PAS, Alcian blue single or Alcian blue/PAS double staining, immunofluorescence staining, and qRT-PCR were performed (see details in supplemental information: histological assessment, immunofluorescence on tissue sections and whole flat-mount corneas, and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction).

Cell proliferation measured by EdU and BrdU incorporation

To determine the level of proliferation within the cornea, we employed EdU and BrdU, which are chemical and antibody-antigen based reactions, respectively. After EdU or BrdU application in vivo, mice were euthanized, and corneas were fixed, dissected, and stained for EdU according to manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described (Park et al., 2019) (see details in supplemental information: cell proliferation measured by EdU and BrdU incorporation).

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = sample size). Unpaired two-tailed Welch’s t test with unequal variance was used to compare EdU+ and BrdU+ cells between LSCD and control, and ANOVA with Sidak’s or Tukey’s multiple comparisons was used for fluorescence intensity of K10, K12, CD31, and MUC5AC and analysis of OCT or when ascertaining the number and area occupied by GCs or BrdU+ cells. Pearson’s R was used for the correlation between CD31 and MUC5AC and between CD31 and K12. Two-stage step-up multiple t test was performed for qRT-PCR data. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and N.D.; methodology, M.P., E.P., V.J.C.-T., and M.S.; investigation, M.P., R.Z., E.P., V.J.C.-T., and M.S.; writing – original draft, M.P., V.J.C.-T., and N.D.; writing – review & editing, all authors; funding acquisition, N.D.; resources, N.D.; supervision, N.D.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Associate Professor Phoebe Phillips and Dr. George Sharbeen (UNSW, Australia) for sharing their nu/nu mouse tissues. This work was supported by grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1101078 and APP1156944) to N.D.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: October 20, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2022.09.011.

Supplemental information

References

- Altshuler A., Amitai-Lange A., Tarazi N., Dey S., Strinkovsky L., Hadad-Porat S., Bhattacharya S., Nasser W., Imeri J., Ben-David G.J.C.S.C. Discrete limbal epithelial stem cell populations mediate corneal homeostasis and wound healing. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28:1248–1261.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang L.P., Tanioka H., Kawasaki S., Ang L.P., Yamasaki K., Do T.P., Thein Z.M., Koizumi N., Nakamura T., Yokoi N. Cultivated human conjunctival epithelial transplantation for total limbal stem cell deficiency. Invest. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010;51:758–764. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-T., Nikulina K., Lazarev S., Bahrami A.F., Noble L.B., Gallup M., McNamara N.A. Interleukin-1 as a phenotypic immunomodulator in keratinizing squamous metaplasia of the ocular surface in Sjögren's syndrome. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;177:1333–1343. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cursiefen C., Chen L., Borges L.P., Jackson D., Cao J., Radziejewski C., D’Amore P.A., Dana M.R., Wiegand S.J., Streilein J.W. VEGF-A stimulates lymphangiogenesis and hemangiogenesis in inflammatory neovascularization via macrophage recruitment. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:1040–1050. doi: 10.1172/JCI20465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danahay H., Pessotti A.D., Coote J., Montgomery B.E., Xia D., Wilson A., Yang H., Wang Z., Bevan L., Thomas C., et al. Notch2 is required for inflammatory cytokine-driven goblet cell metaplasia in the lung. Cell Rep. 2015;10:239–252. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danjo S., Friend J., Thoft R.A. Conjunctival epithelium in healing of corneal epithelial wounds. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1987;28:1445–1449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paiva C.S., Villarreal A.L., Corrales R.M., Rahman H.T., Chang V.Y., Farley W.J., Stern M.E., Niederkorn J.Y., Li D.-Q., Pflugfelder S.C. Dry eye–induced conjunctival epithelial squamous metaplasia is modulated by interferon-γ. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007;48:2553–2560. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S.X., Borderie V., Chan C.C., Dana R., Figueiredo F.C., Gomes J.A.P., Pellegrini G., Shimmura S., Kruse F.E., and The International Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency Working Group Global consensus on the definition, classification, diagnosis and staging of limbal stem cell deficiency. Cornea. 2019;38:364–375. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Girolamo N. Moving epithelia: tracking the fate of mammalian limbal epithelial stem cells. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2015;48:203–225. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Girolamo N., Bosch M., Zamora K., Coroneo M.T., Wakefield D., Watson S.L. A contact lens-based technique for expansion and transplantation of autologous epithelial progenitors for ocular surface reconstruction. Transplantation. 2009;87:1571–1578. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a4bbf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogru M., Erturk H., Shimazaki J., Tsubota K., Gul M. Tear function and ocular surface changes with topical mitomycin (MMC) treatment for primary corneal intraepithelial neoplasia. Cornea. 2003;22:627–639. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200310000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotto G.P., Rustgi A.K. Squamous cell cancers: a unified perspective on biology and genetics. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:622–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dua H.S., Miri A., Alomar T., Yeung A.M., Said D.G. The role of limbal stem cells in corneal epithelial maintenance: testing the dogma. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:856–863. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espana E.M., Di Pascuale M.A., He H., Kawakita T., Raju V.K., Liu C.-Y., Tseng S.C.G. Characterization of corneal pannus removed from patients with total limbal stem cell deficiency. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:2961–2966. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy J.V., Dickey B.F. Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:2233–2247. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima A., Iftekhar G., Sangwan V.S., Vemuganti G.K. Ocular surface changes in limbal stem cell deficiency caused by chemical injury: a histologic study of excised pannus from recipients of cultured corneal epithelium. Eye. 2008;22:1161–1167. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraunfelder F.T., Wright P., Tripathi R.C. Corneal mucus plaques. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1977;83:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(77)90616-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham D.Y., Rugge M., Genta R.M. Diagnosis: gastric intestinal metaplasia-what to do next? Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2019;35:535–543. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris T.M., Berry E.R., Pakurar A.S., Sheppard L.B. Biochemical transformation of bulbar conjunctiva into corneal epithelium: an electrophoretic analysis. Exp. Eye Res. 1985;41:597–605. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(85)90032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang A.J., Tseng S.C. Corneal epithelial wound healing in the absence of limbal epithelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1991;32:96–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang A.J., Watson B.D., Hernandez E., Tseng S.C. Induction of conjunctival transdifferentiation on vascularized corneas by photothrombotic occlusion of corneal neovascularization. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:228–235. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joussen A.M., Poulaki V., Mitsiades N., Stechschulte S.U., Kirchhof B., Dartt D.A., Fong G.-H., Rudge J., Wiegand S.J., Yancopoulos G.D., Adamis A.P. VEGF-dependent conjunctivalization of the corneal surface. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:117–123. doi: 10.1167/iovs.01-1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminska G.M., Niederkorn J.Y. Spontaneous corneal neovascularization in nude mice. Local imbalance between angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1993;34:222–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki S., Tanioka H., Yamasaki K., Yokoi N., Komuro A., Kinoshita S. Clusters of corneal epithelial cells reside ectopically in human conjunctival epithelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:1359–1367. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Lee S., Chang H., Kim M., Kim M.J., Kim K.H. In vivo fluorescence imaging of conjunctival goblet cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9:15457. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51893-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenzer K.L., Freddo T.F. Cytokeratin expression in normal human bulbar conjunctiva obtained by impression cytology. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997;38:142–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse F.E., Chen J.J., Tsai R.J., Tseng S.C. Conjunctival transdifferentiation is due to the incomplete removal of limbal basal epithelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1990;31:1903–1913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubilus J.K., Zapater I Morales C., Linsenmayer T.F. The corneal epithelial barrier and its developmental role in isolating corneal epithelial and conjunctival cells from one another. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017;58:1665–1672. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-20737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Chen Y.T., Hayashida Y., Blanco G., Kheirkah A., He H., Chen S.Y., Liu C.Y., Tseng S.C.G. Down-regulation of Pax6 is associated with abnormal differentiation of corneal epithelial cells in severe ocular surface diseases. J. Pathol. 2008;214:114–122. doi: 10.1002/path.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Hayashida Y., Chen Y.-T., He H., Tseng D.Y., Alonso M., Chen S.-Y., Xi X., Tseng S.C.G. Air exposure–induced squamous metaplasia of human limbal epithelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008;49:154–162. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Xu F., Zhu J., Krawczyk M., Zhang Y., Yuan J., Patel S., Wang Y., Lin Y., Zhang M., et al. Transcription factor PAX6 (paired box 6) controls limbal stem cell lineage in development and disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:20448–20454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.662940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim P., Fuchsluger T.A., Jurkunas U.V. Limbal stem cell deficiency and corneal neovascularization. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2009;24:139–148. doi: 10.1080/08820530902801478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.-T., Hu F.-R., Kuo K.-T., Chen Y.-M., Chu H.-S., Lin Y.-H., Chen W.-L. The different effects of early and late bevacizumab (Avastin) injection on inhibiting corneal neovascularization and conjunctivalization in rabbit limbal insufficiency. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010;51:6277–6285. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo E.P., Delic N.C., Richardson A., Raviraj V., Halliday G.M., Di Girolamo N., Myerscough M.R., Lyons J.G. Self-organized centripetal movement of corneal epithelium in the absence of external cues. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12388. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merjava S., Brejchova K., Vernon A., Daniels J.T., Jirsova K. Cytokeratin 8 is expressed in human corneoconjunctival epithelium, particularly in limbal epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:787–794. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer P.D., Kaufman A.H., Zhang Z., Kao C.W., Spaulding A.G., Kao W.W. Conjunctival epithelial cells can resurface denuded cornea, but do not transdifferentiate to express cornea-specific keratin 12 following removal of limbal epithelium in mouse. Differentiation. 1996;60:31–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1996.6010031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay M., Gorivodsky M., Shtrom S., Grinberg A., Niehrs C., Morasso M.I., Westphal H. Dkk2 plays an essential role in the corneal fate of the ocular surface epithelium. Development. 2006;133:2149–2154. doi: 10.1242/dev.02381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murube J., Rivas L. Impression cytology on conjunctiva and cornea in dry eye patients establishes a correlation between squamous metaplasia and dry eye clinical severity. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2003;13:115–127. doi: 10.1177/112067210301300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki T., Zhao J. Uniform distribution of epithelial stem cells in the bulbar conjunctiva. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:126–132. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasser W., Amitai-Lange A., Soteriou D., Hanna R., Tiosano B., Fuchs Y., Shalom-Feuerstein R. Corneal-committed cells restore the stem cell pool and tissue boundary following injury. Cell Rep. 2018;22:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohji M., Ohmi G., Kiritoshi A., Kinoshita S. Goblet cell density in thermal and chemical injuries. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1987;105:1686–1688. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060120084031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKada T.S. Clarendon Press; 1991. Transdifferentiation-Flexibility in Cell Differentiation. [Google Scholar]

- Ono K., Yokoo S., Mimura T., Usui T., Miyata K., Araie M., Yamagami S., Amano S. Autologous transplantation of conjunctival epithelial cells cultured on amniotic membrane in a rabbit model. Mol. Vis. 2007;13:1138–1143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang H., Xue Y., Lin Y., Zhang X., Xi L., Patel S., Cai H., Luo J., Zhang M., Zhang M., et al. WNT7A and PAX6 define corneal epithelium homeostasis and pathogenesis. Nature. 2014;511:358–361. doi: 10.1038/nature13465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajoohesh-Ganji A., Pal-Ghosh S., Tadvalkar G., Stepp M.A. Corneal goblet cells and their niche: implications for corneal stem cell deficiency. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2032–2043. doi: 10.1002/stem.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal-Ghosh S., Tadvalkar G., Jurjus R.A., Zieske J.D., Stepp M.A. BALB/c and C57BL6 mouse strains vary in their ability to heal corneal epithelial debridement wounds. Exp. Eye Res. 2008;87:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M., Richardson A., Pandzic E., Lobo E.P., Whan R., Watson S.L., Lyons J.G., Wakefield D., Di Girolamo N. Visualizing the contribution of keratin-14+ limbal epithelial precursors in corneal wound healing. Stem Cell Rep. 2019;12:14–28. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini G., Golisano O., Paterna P., Lambiase A., Bonini S., Rama P., De Luca M. Location and clonal analysis of stem cells and their differentiated progeny in the human ocular surface. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:769–782. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portal C., Gouyer V., Gottrand F., Desseyn J.-L. Preclinical mouse model to monitor live Muc5b-producing conjunctival goblet cell density under pharmacological treatments. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que J., Garman K.S., Souza R.F., Spechler S.J. Pathogenesis and cells of origin of Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:349–364.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rama P., Matuska S., Paganoni G., Spinelli A., De Luca M., Pellegrini G. Limbal stem-cell therapy and long-term corneal regeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:147–155. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaesh T., Collinson J.M., Ramaesh K., Kaufman M.H., West J.D., Dhillon B. Corneal abnormalities in Pax6+/− small eye mice mimic human aniridia-related keratopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:1871–1878. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A., Lobo E.P., Delic N.C., Myerscough M.R., Lyons J.G., Wakefield D., Di Girolamo N. Keratin-14-positive precursor cells spawn a population of migratory corneal epithelia that maintain tissue mass throughout life. Stem Cell Rep. 2017;9:1081–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saidkasimova S., Roberts F., Jay J.L. Mucous plaque keratitis associated with aniridia keratopathy. Eye. 2005;19:926–928. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakimoto T., Sakimoto A., Yamagami S. Autologous transplantation of conjunctiva by modifying simple limbal epithelial transplantation for limbal stem cell deficiency. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2020;64:54–61. doi: 10.1007/s10384-019-00701-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sati A., Basu S., Sangwan V.S., Vemuganti G.K. Correlation between the histological features of corneal surface pannus following ocular surface burns and the final outcome of cultivated limbal epithelial transplantation. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2015;99:477–481. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlötzer-Schrehardt U., Latta L., Gießl A., Zenkel M., Fries F.N., Käsmann-Kellner B., Kruse F.E., Seitz B. Dysfunction of the limbal epithelial stem cell niche in aniridia-associated keratopathy. Ocul. Surf. 2021;21:160–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro M.S., Friend J., Thoft R.A. Corneal re-epithelialization from the conjunctiva. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1981;21:135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack J. Epithelial metaplasia and the second anatomy. Lancet. 1986:268–271. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoft R.A. Conjunctival transplantation. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1977;95:1425–1427. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450080135017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tole D.M., McKelvie P.A., Daniell M. Reliability of impression cytology for the diagnosis of ocular surface squamous neoplasia employing the Biopore membrane. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2001;85:154–158. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng S.C., Hirst L.W., Farazdaghi M., Green W.R. Goblet cell density and vascularization during conjunctival transdifferentiation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1984;25:1168–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Acker S.I., Van den Bogerd B., Haagdorens M., Siozopoulou V., Ní Dhubhghaill S., Pintelon I., Koppen C. Pterygium—the good, the bad, and the ugly. Cells. 2021;10:1567. doi: 10.3390/cells10071567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauclair S., Majo F., Durham A.-D., Ghyselinck N.B., Barrandon Y., Radtke F. Corneal epithelial cell fate is maintained during repair by Notch1 signaling via the regulation of vitamin A metabolism. Dev. Cell. 2007;13:242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang I., Kao C.W., Liu C., Saika S., Nishina P.M., Sundberg J.P., Smith R.S., Kao W.W. Characterization of Corn1 mice: alteration of epithelial and stromal cell gene expression. Mol. Vis. 2001;7:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z.-G., Wu R.-L., Lavker R.M., Sun T.-T. In vitro growth and differentiation of rabbit bulbar, fornix, and palpebral conjunctival epithelia. Implications on conjunctival epithelial transdifferentiation and stem cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1993;34:1814–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z.-G., Lin T., Sun T.-T., Lavker R.M. Clonal analysis of the in vivo differentiation potential of keratinocytes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997;38:753–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtschafter J.D., Ketcham J.M., Weinstock R.J., Tabesh T., McLoon L.K. Mucocutaneous junction as the major source of replacement palpebral conjunctival epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1999;40:3138–3146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Zhao J., Chen L., Urbanowicz M.M., Nagasaki T. Abnormal epithelial homeostasis in the cornea of mice with a destrin deletion. Mol. Vis. 2008;14:1929–1939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Lam O., Nguyen M.-T.T., Ng G., Pear W.S., Ai W., Wang I.-J., Kao W.W.-Y., Liu C.-Y. Mastermind-like transcriptional co-activator-mediated Notch signaling is indispensable for maintaining conjunctival epithelial identity. Development. 2013;140:594–605. doi: 10.1242/dev.082842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.