Abstract

Background

Multiple studies have examined the effects of compulsory community treatment (CCT), amongst them there were three randomized controlled trials (RCT). Overall, they do not find that CCT affects clinical outcomes or reduces the number or duration of hospital admissions more than voluntary care does. Despite these negative findings, in many countries CCT is still used. One of the reasons may be that stakeholders favor a mental health system including CCT.

Aim

This integrative review investigated the opinions of stakeholders (patients, significant others, mental health workers, and policy makers) about the use of CCT.

Methods

We performed an integrative review; to include all qualitative and quantitative manuscripts on the views of patients, significant others, clinicians and policy makers regarding the use of CCT, we searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane CENTRAL Register of Controlled Trials (via Wiley), and Google Scholar.

Results

We found 142 studies investigating the opinion of stakeholders (patients, significant others, and mental health workers) of which 55 were included. Of these 55 studies, 29 included opinions of patients, 14 included significant others, and 31 included mental health care workers. We found no studies that included policy makers. The majority in two of the three stakeholder groups (relatives and mental health workers) seemed to support a system that used CCT. Patients were more hesitant, but they generally preferred CCT over admission. All stakeholder groups expressed ambivalence. Their opinions did not differ clearly between those who did and did not have experience with CCT. Advantages mentioned most regarded accessibility of care and a way to remain in contact with patients, especially during times of crisis or deterioration. The most mentioned disadvantage by all stakeholder groups was that CCT restricted autonomy and was coercive. Other disadvantages mentioned were that CCT was stigmatizing and that it focused too much on medication.

Conclusion

Stakeholders had mixed opinions regarding CCT. While a majority seemed to support the use of CCT, they also had concerns, especially regarding the restrictions CCT imposed on patients’ freedom and autonomy, stigmatization, and the focus on medication.

Keywords: involuntary treatment, attitude of health personnel, personal satisfaction, family, personal autonomy, outpatient compulsory treatment, supervised community treatment, community treatment order

Introduction

Compulsory Community Treatment (CCT) is available as a coercive outpatient treatment option in many countries, including the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Asia, UK, and the Netherlands (1, 2). It is also known as Outpatient Compulsory Treatment or Supervised Community Treatment. The intention of this court-ordered treatment is to offer a less restrictive alternative to involuntary admission and to prevent relapses and the readmissions that can result from problems such as non-compliance with treatment. Although patients remain in the community, they have to comply with certain conditions such as taking medication or keeping appointments. The consequence of not complying with these conditions is usually readmission to a psychiatric hospital (3). In several countries, including United Kingdom, the court order is called a community treatment order (CTO).

There is an ongoing debate about the evidence on the effectiveness of CCT. Reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and pre-post studies on the effects of CCT did not demonstrate that CCT was more effective than voluntary outpatient care, either in reducing the number or duration of hospital admissions or in improving clinical outcomes (4, 5). The last Cochrane review in 2014 summarized the RCTs as follows: “CCT results in no significant difference in service use, social functioning or quality of life compared with standard voluntary care. […] However, [these] conclusions are based on three relatively small trials, with high or unclear risk of blinding bias, and low- to moderate-quality evidence” (5).

The most recent meta-analysis about the effects of CCT, states: “We found no consistent evidence that CCT reduces readmission or length of inpatient stay, although it might have some benefit in enforcing use of outpatient treatment or increasing service provision, or both” (4).

Kisely et al. performed a meta-analysis on outcomes of CCT in Australia and New Zealand. They did not find that CCT reduced the duration or number of admissions (6). Neither did the observational study of Weich et al. (7). There is some evidence suggesting that longer CTO’s are of greater benefit in improving outcome measures (6, 8). Other recent naturalistic studies did find that CCT increased treatment adherence, could increase the time people spent outside hospital, could decrease suicide risk and mortality and could decrease the duration of admission to hospital (8–11).

Despite discussions about its effectiveness, CCT is still used in many countries (4). This might be because in developing mental health laws, other views, factors, and experiences are taken into account. It may be that stakeholder groups (clinicians, patients, significant others, and policy makers) have positive views on the use CCT, despite a lack of scientific evidence of its effectiveness.

Corring et al. performed a constant comparative analysis of published qualitative research of three stakeholder groups (patients, relatives, and mental health workers) concerning CCT. They find that all three groups see benefits that outweigh the coercive nature of CCT, but also name limitations regarding the representativeness of people on the CTO group, which may bias the results (12).

With this integrative review we added to this knowledge by:

(1) Integrating both the qualitative as well as the quantitative results of studies on the views on CCT of these stakeholder groups, now also searching for the views of policy makers.

(2) Investigating whether their opinion was influenced by having experience with CCT.

Methods

Integrative reviews – the method we chose to analyse the existing literature – were described by Whittemore and Knafl as “the broadest type of research review methods allowing for the simultaneous inclusion of experimental and non-experimental research in order to more fully understand a phenomenon of concern. [They] may also combine data from the theoretical as well as empirical literature” (13). By allowing for the inclusion of different methodologies (e.g., both quantitative and qualitative) to represent the current knowledge on a subject (13), integrative reviews are therefore very suited to analyse the wide-ranging literature on stakeholders’ views and experiences, as any restrictions on the inclusion of the manuscripts based on methodology would lead to the loss of valuable inputs.

Whittemore and Knafl describe five steps in performing an integrative review: (1) Problem identification, (2) Literature search, (3) Data evaluation, (4) Data analysis, and (5) Presentation.

These steps were followed in the execution of this integrative review.

Problem identification

While there is no evidence from empirical studies (see “Introduction” section) that CCT is an effective way to reduce time spent in hospital, the number of admissions or to improve clinical outcomes, many countries still use this measure. Maybe this decision is based on opinions of stakeholders who have other arguments than scientific evidence to be in favor of a mental health system including CCT. Therefore, we would like to know: (1) the opinions of the various stakeholders (patients, significant others, mental health workers, and policy makers) on the use of CCT and whether their opinion was influenced by having experience with CCT; and (2) the advantages and disadvantages of CCT these stakeholders identified.

Literature search

The following electronic bibliographic databases were searched two times, on 24 September 2019 and 27 August 2021 (date last searched) for manuscripts published in English: MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE (via embase.com), PsycINFO (via Ovid), CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (via Wiley) and Google Scholar. Although we used no filters for dates, populations and study designs, conference abstracts were removed from the search. Using the method described by Bramer et al. (14), the search was developed by an experienced information specialist (WMB) in close collaboration with the first author (DW). It consisted of four elements that are searched as controlled terms (MeSH or Emtree terms) and free text terms in title and/or abstract:

(1) Compulsory or involuntary, (2) outpatient or community, (3) mental health care or psychiatric diseases, and (4) experiences or opinion. We limited the results to articles published in the English language. Appendix 1 lists the search terms for all databases. References were imported in EndNote and deduplicated according to the method described by Bramer et al. (15).

Data evaluation

AM and DW screened the title and, if the title indicated that the manuscript could be relevant, abstract of all the manuscripts in order to identify and include:

-

-

All qualitative and quantitative studies on the views of patients, significant others (partner, family, and carers), clinicians and policy makers regarding the use of CCT.

In the selected manuscripts, we also checked all references for relevant studies. If there was no initial consensus on including the manuscript for full text reading, or if the title and abstract did not provide enough information to decide whether a manuscript should be included at this stage, the manuscript was selected for full-text reading.

DW and AM separately reviewed the manuscripts selected. Each manuscript was thoroughly read by both DW and LM separately to see if the authors described the opinion of the participants concerning whether or not they supported the use of CCT.

Table 1 describes the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria in the full text reading phase.

|

Inclusion - Quantitative and qualitative studies on the views of stakeholders regarding the use of CCT - Only manuscripts are included that express whether or not stakeholders support the use of CCT - Manuscripts published only in English in peer-reviewed journals until September 2021 Exclusion - Manuscripts that do not indicate whether stakeholders support or reject a system with CCT - Manuscripts that study the same population as another included manuscript (the manuscript that focused most on our question was chosen in these situation) |

Then from the selected manuscripts the following data was extracted using a data extraction table:

-

-

Which stakeholder groups.

-

-

Whether the study used qualitative or quantitative methods.

-

-

Country the study was performed in.

-

-

In which way data was collected.

-

-

Number of stakeholders.

-

-

Whether or not participants had experience with CCT.

-

-

For quantitative manuscripts: the percentages of stakeholders that were either for or against CCT.

-

-

For qualitative manuscripts: terms in the studies that described the stakeholders’ majority view, such as “generally preferred…”, “supported”, “were opposed to”, “rejected” or “favored”. When possible, in the results of this review the literal phrases in the manuscripts are used to describe the results.

Discrepancies between DW and AM regarding the conclusion in qualitative manuscripts that the majority of the participants were in favor, were mixed or against the use of CCT, were discussed until consensus could be reached.

Quantitative results and qualitative results were summarized in a single table.

When the different stakeholder groups mentioned specific advantages or disadvantages of CCT, these were extracted and included in a separate table, being ranked from most to least mentioned by stakeholders in the different manuscripts.

No separate quality assessment of manuscripts was conducted. To ensure the quality of the manuscripts we only included manuscripts that had been published in journals with peer review.

Results

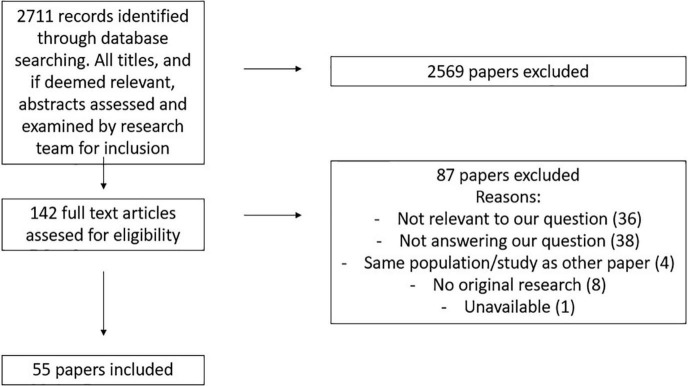

The search in the different databases identified 5,300 manuscripts, from which 2,711 unique articles remained after deduplication. On the basis of their title and in some cases abstract, 2,569 of the identified manuscripts were excluded, as they did not meet our inclusion criteria.

Finally, after full text screening, 55 manuscripts were included in the analysis (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Literature selection process.

Table 2 lists the stakeholders’ opinions on the use of CCT. Quantitative outcomes are reported as percentages. The outcomes of qualitative studies are reported as they were reported in the manuscript. The number of participants named in the table for these quantitative studies, is, as far as it could be traced back, the number of participants answering the question about CCT.

TABLE 2.

Outcomes of the studies that investigated the views of patients, significant others and mental health workers on the use of compulsory community treatment (CCT).

| Stakeholder | Quantitative or qualitative | Country | Author | Year | Method | Participant | Experience with CCT | Summary of findings |

| Patients | Qualitative | USA | Scheid-Cook (3) | 1993 | Interviews | 51 patients | Yes | Generally preferred CCT to admission |

| Qualitative | England | Canvin et al. (16) | 2002 | Interviews | 20 patients | Yes | Most believed CCT to be better than hospitalization | |

| Qualitative | Australia | Brophy and Ring (17) | 2004 | Focus groups | 30 patients | Yes | Were generally dissatisfied with many aspects of CCT | |

| Qualitative | Canada | O’Reilly et al. (18) | 2006 | Interviews | 14 patients | Yes | Preferred a CTO over returning to hospital | |

| Qualitative | England | Gault (19) | 2009 | Interviews | 11 patients | No | All were opposed to CCT | |

| Qualitative | Canada | Schwartz et al. (20) | 2010 | Interviews | 6 patients | Yes | Views on CCT were mixed | |

| Qualitative | Scotland | Ridley and Hunter (21) | 2013 | Interviews | 49 patients | Partly (35%) | Welcomed CCT in the light of an alternative to involuntary admission | |

| Qualitative | England | Fahy et al. (22) | 2013 | Structured interviews | 17 patients | Yes | Views on CCT were mixed | |

| Qualitative | Canada | Mfoafo-M’Carthy (23) | 2014 | Interviews | 24 patients | Yes | Most participants expressed appreciation of CCT | |

| Qualitative | Norway | Riley et al. (24) | 2014 | Interviews | 11 patients | Yes | Generally preferred CCT to admission | |

| Qualitative | Australia | Light et al. (25) | 2014 | Interviews | 5 patients | Yes | Participants experienced ambivalence toward CCT | |

| Qualitative | England | Stroud et al. (26) | 2015 | Interviews | 21 patients | Yes | Participants were often keen to stay on the CTO | |

| Qualitative | Norway | Stuen et al. (27) | 2015 | Interviews | 15 patients | Yes | Participants had different views | |

| Qualitative | Norway | Stensrud et al. (28) | 2015 | Interviews | 16 patients | Yes | Views on CCT were mixed | |

| Qualitative | England | Banks et al. (29) | 2016 | Interviews | 21 patients | Yes | Most preferred CCT to admission | |

| Qualitative | Canada | O’Reilly et al. (30) | 2016 | Focus groups | 20 patients | Yes | Were ambivalent about CCT | |

| Qualitative | Canada | Francombe et al. (31) | 2018 | Interviews | 9 patients | Yes | Generally preferred CCT to admission | |

| Qualitative | Canada | Mfoafo-M’Carthy et al. (32) | 2018 | Interviews | 11 patients | Yes | Most participants had negative feelings toward CCT | |

| Qualitative | England | Haynes and Stroud (33) | 2019 | Interviews | 16 patients | Yes | Overall, patients saw CCT as more favorable than as adverse | |

| Qualitative | Australia | McMillan et al. (34) | 2019 | Interviews | 8 patients | Yes | Participants had diverse experiences of CCT | |

| Qualitative | Australia | Brophy et al. (35) | 2019 | Interviews | 8 patients | Yes | Most described CCT as wholly negative | |

| Qualitative | Australia | Dawson et al. (36) | 2021 | Interviews | 8 patients | Yes | Some considered CCT to be benign; others felt it had been a negative experience | |

| Quantitative | USA | Swartz et al. (37) | 2003 | Interviews | 123 patients | Yes | 72% did not endorse the benefits of CCT | |

| Quantitative | USA | Swartz et al. (38) | 2004 | Interviews using vignettes | 104 patients | Unclear | 55% regarded CCT as fair, 62% as effective The majority preferred CCT to admission |

|

| Quantitative | England | Crawford et al. (39) | 2004 | Structured interviews | 103 patients | No | 60% preferred CCT over admission | |

| Quantitative | New Zealand | Gibbs et al. (40) | 2006 | Semi structured interview | 42 patients | Yes | 65% was favorable toward CCT | |

| Quantitative | Ireland | O’Donoghue et al. (41) | 2010 | Interviews | 67 patients | No | 56% would prefer treatment in hospital to CCT | |

| Quantitative | New Zealand | Newton-Howes and Banks (42) | 2014 | Questionnaires | 79 patients | Yes | 53% thought they would have been better off treated informally | |

| Quantitative | Canada | Nakhost et al. (43) | 2019 | Interviews | 69 patients | Yes | 82% preferred CCT to admission | |

| Significant others | Qualitative | USA | Swartz et al. (44) | 2003 | Interviews using vignettes | 83 significant others | Unclear | Generally preferred CCT to admission |

| Qualitative | Canada | O’Reilly et al. (45) | 2006 | Interviews focus groups | 14 significant others | Yes | Were very positive about CCT | |

| Qualitative | New Zealand | Gibbs et al. (40) | 2006 | Semi-structured interviews | 27 significant others | Yes | The great majority supported the use of CCT | |

| Qualitative | England | Gault (19) | 2009 | Interviews | 8 significant others | No | All were opposed to CCT | |

| Qualitative | Australia | Light et al. (25) | 2014 | Interviews | 6 significant others | Yes | Were ambivalent about CCT | |

| Qualitative | England | Stroud et al. (26) | 2015 | Interviews | 7 significant others | Yes | Felt reassured and better consulted with CCT | |

| Qualitative | Norway | Stensrud et al. (46) | 2015 | Interviews | 11 significant others | Yes | Generally supported the use of CCT | |

| Qualitative | Canada | O’Reilly et al. (30) | 2016 | Focus groups | 18 significant others | Yes | Were positive about CCT | |

| Qualitative | England | Banks et al. (29) | 2016 | Interviews | 7 significant others | Yes | Generally positive toward CCT | |

| Qualitative | England | Rugkasa and Canvin (47) | 2017 | Interviews | 24 significant others | Yes | Generally supported the use of CCT | |

| Qualitative | Canada | Francombe et al. (31) | 2018 | Interviews | 6 significant others | Yes | Generally preferred CCT to admission | |

| Qualitative | Australia | Brophy et al. (35) | 2019 | Interviews | 30 significant others | Partly (33%) | Often identified the CTO as helping | |

| Quantitative | USA | McFarland et al. (48) | 1990 | Questionnaires | 209 significant others | No | 57% were in favor of outpatient commitment | |

| Quantitative | New Zealand | Vine and Komiti (49) | 2015 | Questionnaires | 62 significant others | Partly (63%) |

67% said that CTOs should be included in mental health legislation | |

| Mental health workers | Qualitative | USA | Scheid-Cook (3) | 1993 | Interviews | 73 mental health workers | Yes | Participants found CCT to be in general a good thing |

| Qualitative | USA | Swartz et al. (44) | 2003 | Questionnaires with vignettes | 85 mental health workers | Unclear | Generally preferred CCT to admission | |

| Qualitative | Canada | O’Reilly et al. (18) | 2006 | Focus groups | 78 mental health workers | Yes | Most mental health workers felt that orders can be useful | |

| Qualitative | New Zealand | Gibbs et al. (40) | 2006 | Semi-structured interviews | 90 mental health practitioners | Yes | Generally favored the use of CCT | |

| Qualitative | England | Taylor et al. (50) | 2013 | Questionnaires | 9 mental health professionals | Yes | Participants were ambivalent about CCT | |

| Qualitative | USA | Sullivan et al. (51) | 2014 | Interviews | 19 mental health workers | Yes | Participants were not unanimous in their comfort with CCT. | |

| Qualitative | England | Stroud et al. (26) | 2015 | Interviews | 35 mental health workers | Yes | CTT was perceived helpful for certain patients | |

| Qualitative | Canada | O’Reilly et al. (30) | 2016 | Focus groups | 27 mental health workers | Yes | Generally supported the use of CCT | |

| Qualitative | Norway | Stensrud et al. (52) | 2016 | Focus groups | 22 mental health workers | Yes | Participants had a positive view of CCT | |

| Qualitative | Canada | Pridham et al. (53) | 2018 | Interviews | 12 service providers | Yes | Saw CCT as a welcome alternative to admission | |

| Qualitative | Canada | Mfoafo-M’Carthy et al. (32) | 2018 | Focus group Interviews | 6 mental health workers 1 psychiatrist, 1 programme coordinator |

Yes | Believed that it was in the best interest of certain patients to use CCT | |

| Qualitative | Norway | Riley et al. (54) | 2018 | Interviews | 9 mental health workers | Yes | Viewed CCT as a useful scheme | |

| Qualitative | Norway | Stuen et al. (55) | 2018 | Interviews Focus groups |

8 clinicians 20 ACT-providers |

Yes | Generally believed CTO’s were sometimes necessary | |

| Qualitative | England | Haynes and Stroud (33) | 2019 | Interviews | 41 mental health professionals | Yes | Favored CCT over involuntary admission | |

| Qualitative | Australia | Brophy et al. (35) | 2019 | Interviews | 30 mental health workers | Yes | Were ambivalent about CCT | |

| Quantitative | England | Burns (56) | 1995 | Questionnaires | 59 psychiatrists 55 Community nurses 101 approved social workers |

No | 96% was willing to work with CCT 69% was willing to work with CCT 77% was willing to work with CCT |

|

| Quantitative | Scotland | Atkinson et al. (57) | 1997 | Questionnaires | 193 psychiatrists | No | 86% were against CCT but did support the use of “leave of absence” |

|

| Quantitative | England | Bhatti et al. (58) | 1999 | Structured interviews | 83 mental health workers | No | 68% supports the introduction of CCT | |

| Quantitative | England | Crawford et al. (59) | 2000 | Questionnaires | 1171 psychiatrists | No | 46% supported the use of CCT 35% were against 19% were unsure |

|

| Quantitative | Scotland | Atkinson and Harper Gilmour (60) | 2000 | Questionnaires | 230 psychiatrists 244 mental health officers |

Partly (6%) |

69% were against CCT 42% were against CCT |

|

| Quantitative | Canada | O’Reilly et al. (61) | 2000 | Questionnaires | 50 psychiatrists | Partly (48%) |

62% is satisfied with the use of CCT | |

| Quantitative | United Kingdom | Pinfold et al. (62) | 2002 | Questionnaires | 415 mental health workers | Might have | 62% would not welcome powers of CCT | |

| Quantitative | Australia | Brophy and Ring (17) | 2004 | Interviews | 18 mental health workers | Yes | 72% was satisfied with the way the orders were used | |

| Quantitative | New Zealand | Romans et al. (63) | 2004 | Questionnaires | 202 psychiatrists 82 mental health workers |

Unclear | 79% preferred to work in a system with CCT 85% preferred to work in a system with CCT |

|

| Quantitative | USA | Christy et al. (64) | 2009 | Questionnaires | 242 mental health workers | Partly (45%) |

87% agreed with the use of CCT | |

| Quantitative | England and Wales | Manning et al. (65) | 2011 | Questionnaires | 566 psychiatrists | Yes (most did) |

60% preferred to work in a system with CCT | |

| Quantitative | England | Coyle et al. (66) | 2013 | Questionnaires | 58 psychiatrists 212 other mental health workers |

Unclear | 83% supported the use of CCT 67% supported the use of CCT |

|

| Quantitative | United Kingdom | Gupta et al. (67) | 2015 | Questionnaires | 94 psychiatrists | Partly (78%) | 55% stated that CCT helped to manage patients with complex needs | |

| Quantitative | Taiwan | Hsieh et al. (68) | 2016 | Questionnaires | 176 mental health practitioners | Yes | 75% preferred to work in a system with CCT | |

| Quantitative | Netherlands | De Waardt et al. (69) | 2020 | Interviews | 40 mental health workers | Yes | 73% supported the use of CCT | |

| Quantitative | Spain | Moleon Ruiz and Fuertes Rocanin (70) | 2020 | Interviews | 32 psychiatrists, 10 residents [i.e., doctors] in psychiatry | No | 92.8% supported the introduction of CCT | |

| Other | Quantitative | USA | McFarland et al. (71) | 1989 | Questionnaires | 92 commitment investigators 46 judges |

No | 72% supported the theory of outpatient commitment 74% supported the theory of outpatient commitment |

Appendix 2 lists participants characteristics, the kind of service participants were recruited from and the available information about methods of recruitment.

Data analysis and presentation

Patients

We found 29 manuscripts that reported on the views of patients, 22 of which were qualitative and seven of which were quantitative. Participants in 24 of the 29 studies had experience with CCT.

The studies were performed in eight different countries, being; Canada (n = 7), England (n = 7), Australia (n = 5), USA (n = 3), Norway (n = 3), New Zealand (n = 2), Scotland (n = 1), and Ireland (n = 1).

Of these 29 manuscripts, 14 found that the general opinion of patients was in favor of the use of CCT, eight found ambivalent views and seven found that the general opinion was against the use of CCT.

Significant others

In total, 14 manuscripts reported on the views of significant others (12 qualitative studies and 2 quantitative studies), 12 of them found that significant others supported the use of CCT, one found mixed feelings and one found that they were against the use of CCT.

In 11 of the 12 manuscripts in favor of CCT, the relatives had experience with CCT. So did the participants in the manuscript that reported mixed feelings. The participants in the manuscripts that found a negative attitude toward CCT did not have experience with CCT.

These manuscripts originated from six countries; England (n = 4), Canada (n = 3), New Zealand (n = 2), USA (n = 2), Australia (n = 2), and Norway (n = 1).

Mental health workers

Of the 31 manuscripts that reported the views of mental health workers (15 qualitative and 16 quantitative studies), 24 found that the majority of mental health workers supported the use of CCT, 4 found their participants to have mixed feelings and 3 found that their participants were mainly against the use of CCT. Two out of three studies in this last group were carried out in Scotland around the time CCT was implemented; the participants in these studies did not have experience with CCT.

These studies were performed in 13 different regions/countries: England (n = 7), Canada (n = 5), USA (n = 4), Norway (n = 3), New Zealand (n = 2), Australia (n = 2), Scotland (n = 2), United Kingdom (n = 2), Taiwan (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 1), England and Wales (n = 1), and Spain (n = 1).

There was a wide range of different mental health workers who participated in the studies, amongst them were psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers, and occupational therapist. Appendix 2 lists the specific occupations for each study, as far as they were reported.

We found no manuscripts that reported the views of policy makers; we did find one study on the views of judges and commitment investigators, the majority of whom supported the use of CCT.

Overall, there are more studies that reported that patients were against the use of CCT (7 out of 29 studies), compared to relatives (1 out of 14 studies) and mental health workers (3 out of 31 studies).

But all stakeholder groups report ambivalence toward CCT.

Since most studies concerned stakeholders with experience, no conclusion can be drawn for all stakeholder groups regarding the influence of experience with CCT on the opinion on CCT.

The majority of these studies (67%) obtained qualitative data and only 18 (33%) studies obtained quantitative data. The 18 quantitative studies used different outcome measures, such as preferring to work in a system using CCT, or stating that CCT helps patients with complex needs.

Table 3 lists the advantages and disadvantages of CCT mentioned by stakeholders in the various studies. These are ranked from mentioned in most manuscripts to mentioned in least.

TABLE 3.

The five advantages/disadvantages reported most often in studies of experience and views of compulsory community treatment (CCT).

| Advantages |

| Patients |

| - CCT facilitated access to care - Patients experienced increased support - CCT could improve mental health - CCT provided more freedom than involuntary admission - CCT provided a safety net and a sense of security |

| Significant others |

| - CCT facilitated access to care - CCT facilitated earlier admission - CCT could provide more safety for the patient - CCT could take some of the burden away from family members - CCT could lead to greater carer involvement |

| Mental health workers |

| - CCT provided an opportunity to stay in touch and to monitor the patient’s mental health - CCT could enhance compliance to treatment - CCT could provide a safety net - Provided more freedom than involuntary admission - CCT could improve mental health and avoid involuntary admission |

|

|

| Disadvantages |

|

|

| Patients |

| - CCT constrained autonomy and was coercive - CCT was stigmatizing - CCT interfered with daily life - The focus of CCT lay too much on medication - Patients had to deal with the side-effects of forced medication |

| Significant others |

| - CCT constrained autonomy and was coercive - CCT focused too much on medication - The process of applying for CCT was too cumbersome - CCT could be stigmatizing - CCT also put a strain on carers, involving them in treatment |

| Mental health workers |

| - CCT constrained autonomy and is coercive - CCT could interfere with the therapeutic relationship - CCT imposed an extra administrative burden - CCT could be stigmatizing - CCT focused too much on medication |

The advantage mentioned most often for all stakeholder groups was that CCT facilitated access to care. Furthermore, patients mentioned that they experienced increased support in case of CCT versus not having CCT. Significant others expressed that CCT facilitated earlier admission as an important advantage. And for mental health workers a great advantage was also that it could enhance compliance with treatment.

The most mentioned disadvantage by all stakeholder groups was that CCT restricted autonomy and was coercive. Patients mentioned as second most often that it was stigmatizing. For significant others the second most often mentioned disadvantage was that it focused too much on medication and for mental health workers the second most often mentioned disadvantage was that CCT sometimes interfered with the therapeutic relationship.

Discussion

Despite the lack of scientific evidence for the effects of CCT, this integrative review showed that in half of the studies patients, and in the majority of the studies significant others and mental health workers favored a mental health system that included CCT. Nonetheless, nearly all studies indicated that stakeholders expressed ambivalences about CCT. Patients were more critical regarding the use of CCT than the other stakeholders. The question remains why, despite the ambivalence it raised and in the absence of empirical evidence of its effectiveness, CCT is implemented in so many countries.

It can be helpful to look at the advantages as well as the disadvantages of CCT mentioned by stakeholders more in detail.

The advantage of CCT mostly indicated by patients and significant others was that it facilitates access to care. The rationale for this may be that, if a patient’s situation deteriorated (when being on CCT) he or she would always have someone to contact who could provide the necessary (inpatient) care. The most valued advantage of CCT for mental health workers was that it provided a way to monitor a patient’s health and stay in touch with the patient. This improved access to care is supported in some uncontrolled studies that found that CCT increased the number of outpatient contacts (6).

Another advantage frequently mentioned, was that it provides a safety net and a sense of security.

Research findings also suggest that CCT could provide more safety, since there are studies that find that people on a CTO have a lower mortality rate (10), have lower suicide numbers (11) and were more likely to receive acute medical care for a physical illness (72).

The fact that these advantages seem to be so important for the stakeholders, is an interesting finding, as these advantages also could be achieved without CCT, as long as there is adequate access to care and continuity of care. – as in Italy, where outpatient care is easily accessible (73).

However, it has been argued that just the availability and accessibility of mental health care services alone is not enough to engage all groups of patients into mental health care (30).

The disadvantages mentioned mostly by all stakeholders were that CCT is a coercive measure that it constrains autonomy, and also that it is stigmatizing. Some authors argue on the other hand that CCT can help patients regain their autonomy - and reduces stigma when their stability improves (2). Another disadvantage all stakeholder groups mentioned, is the excessive focus on taking medication. Studies into the main reasons for deciding on using a CTO for mental health workers show that adherence to treatment is the most important reason for deciding to use a CTO (63, 65). Maybe this is because medication is something that mental health workers can easily provide (in contrast to proper housing or daytime activities) and it has proven to be effective in improving certain symptoms of mental health disorders. However, in a study on the opinions of mental health workers, mental health workers stressed that treatment not only involves medication, but other factors were also essential, such as a good therapeutic relationship, proper housing and access to jobs or daytime activities (69).

Overall we find that the majority of the stakeholders prefer a system with CCT and apparently puts the emphasis on the advantages, accepting the disadvantages. Corring et al. (12) come to a similar conclusion in their comparative analysis.

When interpreting studies about the opinions of stakeholders on CCT, it should be kept in mind that there is a difference between comparing CCT with involuntary admission and comparing it with voluntary care in the community. A patient could prefer CCT to hospitalization, but if there was the choice between voluntary care in the community or CCT, this person might choose voluntary care. They thus seem to support CCT, but only if the alternative were hospitalization. In many of the studies in which patients reported that they supported CCT, they meant that they preferred it to admission to hospital.

We think patients’ preference should be taken into account when deciding on compulsory care. This practice is already in place in the Netherlands in the new Dutch mental health legislation in which patients make a care plan which entails that patients have the opportunity to state their preferences regarding compulsory care.

O’Reilly et al. describe a general consensus that “the use of CTO”s is justifiable for certain individuals, but only if it can be shown that CTOs confer significant benefits on those individuals’ (74) which leaves room for patients and their mental health care workers to decide to use CCT if they think it helps the patient.

Strengths

The main strength of this integrative review is that it included quantitative as well as qualitative studies. Another strength is that in the literature search we did not focus on specific stakeholder groups but were open for views of all relevant groups.

Limitations

The review protocol was not prospectively registered, however, no protocol changes have been made during the process, also no separate study quality appraisal has been performed for all the studies included.

Many of the studies included in this review were qualitative studies that were not designed to report representative views, but rather to provide the breadth and nuance of experiences in this field. Views on CCT are all very complex and almost always ambivalent, this makes it difficult to state whether participants are “pro or con” CCT. For that reason we also explicitly investigated the advantages and disadvantages reported in these studies.

Also there might be a form of selection bias, since most of the patient participants were recruited through their mental health workers or they signed up for the study themselves. This could mean that the patients who were doing well or were more satisfied with their treatment, were more likely to participate in the studies.

Implications for future research

First, it remains important to investigate further why stakeholders would support CCT. If accessibility and continuity of care is one of the main reasons, countries should invest in accessible voluntary care and further studies should be done to see how we can engage patients more easily in voluntary care rather than relying on coercive legal structures. Second, it would be good to include policymakers and other stakeholders, like judges or general practitioners in this research, in order to investigate the grounds on which mental health laws on CCT are developed and implemented.

Conclusion

While the majority of all stakeholders appears to support the use of CCT, many have reservations. Stakeholders considered the most important advantages of CCT to be access to care and a way to remain in contact with patients and monitor their health, especially during times of crisis or deterioration. Stakeholders mention as the most serious disadvantage the restrictions CCT imposes on patients’ freedom and autonomy, stigmatization, and the focus on the use of medication.

Author contributions

DW wrote the research plan, performed the literature analysis, and wrote the first version and later versions of the manuscript. AM performed the literature analysis and contributed to the manuscript. WB developed the literature search, wrote part of the methodology section, and contributed to the manuscript. FH worked on the initial research plan and contributed to the manuscript. JR worked on the analysis of the data and contributed to the manuscript. GW and CM worked on the research plan, the analysis of the data, and took part in writing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1011961/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Churchill R, Owen G, Singh S, Hotopf M. International experiences of using community treatment orders. London: Department of Health; (2007). 10.1037/e622832007-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mikellides G, Stefani A, Tantele M. Community treatment orders: International perspective. BJPsych Int. (2019) 16:83–6. 10.1192/bji.2019.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheid-Cook TL. Controllers and controlled: An analysis of participant constructions of outpatient commitment. Sociol Health Illn. (1993) 15:179–98. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11346883 22476513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnett P, Matthews H, Lloyd-Evans B, Mackay E, Pilling S, Johnson S. Compulsory community treatment to reduce readmission to hospital and increase engagement with community care in people with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2018) 5:1013–22. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30382-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kisely SR, Campbell LA. Compulsory community and involuntary outpatient treatment for people with severe mental disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2014) 12:CD004408. 10.1002/14651858.CD004408.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kisely S, Yu D, Maehashi S, Siskind D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of predictors and outcomes of community treatment orders in Australia and New Zealand. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2021) 55:650–65. 10.1177/0004867420954286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weich S, Duncan C, Twigg L, McBride O, Parsons H, Moon G, et al. Use of community treatment orders and their outcomes: An observational study. Southampton, MA: NIHR Journals Library; (2020). 10.3310/hsdr08090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris A, Chen W, Jones S, Hulme M, Burgess P, Sara G. Community treatment orders increase community care and delay readmission while in force: Results from a large population-based study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2019) 53:228–35. 10.1177/0004867418758920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank D, Fan E, Georghiou A, Verter V. Community treatment order outcomes in Quebec: A unique jurisdiction. Can J Psychiatry. (2020) 65:484–91. 10.1177/0706743719892718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barkhuizen W, Cullen AE, Shetty H, Pritchard M, Stewart R, McGuire P, et al. Community treatment orders and associations with readmission rates and duration of psychiatric hospital admission: A controlled electronic case register study. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e035121. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt IM, Webb RT, Turnbull P, Graney J, Ibrahim S, Shaw J, et al. Suicide rates among patients subject to community treatment orders in England during 2009–2018. BJPsych Open. (2021) 7:1–6. 10.1192/bjo.2021.1021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corring D, O’Reilly R, Sommerdyk C, Russell E. The lived experience of community treatment orders (CTOs) from three perspectives: A constant comparative analysis of the results of three systematic reviews of published qualitative research. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2019) 66:101453. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.101453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. (2005) 52:546–53. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bramer WM, de Jonge GB, Rethlefsen ML, Mast F, Kleijnen J. A systematic approach to searching: an efficient and complete method to develop literature searches. J Med Libr Assoc. (2018) 106:531–41. 10.5195/jmla.2018.283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. (2016) 104:240–3. 10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canvin K, Bartlett A, Pinfold VA. ‘bittersweet pill to swallow’: Learning from mental health service users’ responses to compulsory community care in England. Health Soc Care Community. (2002) 10:361–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00375.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brophy L, Ring D. The efficacy of involuntary treatment in the community: Consumer and service provider perspectives. Soc Work Ment Health. (2004) 2:157–74. 10.1300/J200v02n02_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Reilly RL, Keegan DL, Corring D, Shrikhande S, Natarajan D. A qualitative analysis of the use of community treatment orders in Saskatchewan. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2016) 29:516–24. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2006.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gault I. Service-user and carer perspectives on compliance and compulsory treatment in community mental health services. Health Soc Care Community. (2009) 17:504–13. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00847.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz K, O’Brien A, Morel V, Armstrong M, Fleming C, Moore P. Community treatment orders: the service user speaks. Exploring the lived experience of community treatment orders. Int J Psychosoc Rehabil. (2010) 15:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ridley J, Hunter S. Subjective experiences of compulsory treatment from a qualitative study of early implementation of the mental health (Care & Treatment)(Scotland) Act 2003. Health Soc Care Community. (2013) 21:509–18. 10.1111/hsc.12041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fahy GM, Javaid S, Best J. Supervised community treatment: Patient perspectives in two Merseyside mental health teams. Ment Health Rev J. (2013) 18:157–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mfoafo-M’Carthy M. Community treatment orders and the experiences of ethnic minority individuals diagnosed with serious mental illness in the Canadian mental health system. Int J Equity Health. (2014) 13:1–10. 10.1186/s12939-014-0069-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riley H, Hyer G, Lorem GF. When coercion moves into your home- – a qualitative study of patient experiences with outpatient commitment in Norway. Health Soc Care Community. (2014) 22:506–14. 10.1111/hsc.12107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Light EM, Robertson MD, Boyce P, Carney T, Rosen A, Cleary M, et al. The lived experience of involuntary community treatment: A qualitative study of mental health consumers and carers. Aust Psychiatry. (2014) 22:345–51. 10.1177/1039856214540759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stroud J, Banks L, Doughty K. Community treatment orders: Learning from experiences of service users, practitioners and nearest relatives. J Ment Health. (2015) 24:88–92. 10.3109/09638237.2014.998809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuen HK, Rugkåsa J, Landheim A, Wynn R. Increased influence and collaboration: a qualitative study of patients’ experiences of community treatment orders within an assertive community treatment setting. BMC Health Serv Res. (2015) 15:409. 10.1186/s12913-015-1083-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stensrud B, Høyer G, Granerud A, Landheim AS. “Life on hold”: A qualitative study of patient experiences with outpatient commitment in two Norwegian counties. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2015) 36:209–16. 10.3109/01612840.2014.955933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banks LC, Stroud J, Doughty K. Community treatment orders: Exploring the paradox of personalisation under compulsion. Health Soc Care Community. (2016) 24:e181–90. 10.1111/hsc.12268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Reilly R, Corring D, Richard J, Plyley C, Pallaveshi L. Do intensive services obviate the need for CTOs? Int J Law. (2016) 47:74–8. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Francombe Pridham K, Nakhost A, Tugg L, Etherington N, Stergiopoulos V, Law S. Exploring experiences with compulsory psychiatric community treatment: A qualitative multi-perspective pilot study in an urban canadian context. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2018) 57:122–30. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mfoafo-M’Carthy M, Grosset C, Stalker C, Dullaart I, McColl L. Exploratory study of the use of community treatment orders with clients of an Ontario ACT team. Soc Work Ment Health. (2018) 16:647–64. 10.1080/15332985.2018.1476283 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haynes P, Stroud J. Community treatment orders and social factors: Complex journeys in the mental health system. J Soc Welfare Fam Law. (2019) 41:463–78. 10.1080/09649069.2019.1663017 32181002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMillan J, Lawn S, Delany-Crowe T. Trust and community treatment orders. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:349. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brophy L, Kokanovic R, Flore J, McSherry B, Herrman H. Community treatment orders and supported decision-making. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:414. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dawson S, Muir-Cochrane E, Simpson A, Lawn S. Community treatment orders and care planning: How is engagement and decision-making enacted? Health Expect. (2021) 24:1859–67. 10.1111/hex.13329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Monahan J. Endorsement of personal benefit of outpatient commitment among persons with severe mental illness. Psychol Public Policy Law. (2003) 9:70. 10.1037/1076-8971.9.1-2.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, Elbogen EB. Consumers’ perceptions of the fairness and effectiveness of mandated community treatment and related pressures. Psychiatr Serv. (2004) 55:780–5. 10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crawford MJ, Gibbon R, Ellis E, Waters H. In hospital, at home, or not at all: A cross-sectional survey of patient preferences for receipt of compulsory treatment. Psychiatr Bull. (2004) 28:360–3. 10.1192/pb.28.10.360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibbs A, Dawson J, Mullen R. Community treatment orders for people with serious mental illness: A New Zealand study. Br J Soc Work. (2006) 36:1085–100. 10.1093/bjsw/bch392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Donoghue B, Lyne J, Hill M, O’Rourke L, Daly S, Feeney L. Patient attitudes towards compulsory community treatment orders and advance directives. Irish J Psychol Med. (2010) 27:66–71. 10.1017/S0790966700001075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newton-Howes G, Banks D. The subjective experience of community treatment orders: Patients’ views and clinical correlations. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2014) 60:474–81. 10.1177/0020764013498870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakhost A, Simpson AI, Sirotich F. Service users’ knowledge and views on outpatients’ compulsory community treatment orders: A cross-sectional matched comparison study. Can J Psychiatry. (2019) 64:726–35. 10.1177/0706743719828961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, Hannon MJ, Burns BJ, Shumway M. Assessment of four stakeholder groups’ preferences concerning outpatient commitment for persons with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. (2003) 160:1139–46. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Reilly RL, Keegan DL, Corring D, Shrikhande S, Natarajan D. A qualitative analysis of the use of community treatment orders in Saskatchewan. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2006) 29:516–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stensrud B, Høyer G, Granerud A, Landheim AS. ‘Responsible, but still not a real treatment partner’: A qualitative study of the experiences of relatives of patients on outpatient commitment orders. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2015) 36:583–91. 10.3109/01612840.2015.1021939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rugkåsa J, Canvin K. Carer involvement in compulsory out-patient psychiatric care in England. BMC Health Serv Res. (2017) 17:762. 10.1186/s12913-017-2716-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McFarland BH, Faulkner LR, Bloom JD, Hallaux R, Bray JD. Family members’ opinions about civil commitment. Psychiatr Serv. (1990) 41:537–40. 10.1176/ps.41.5.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vine R, Komiti A. Carer experience of community treatment orders: Implications for rights based/recovery-oriented mental health legislation. Aust Psychiatry. (2015) 23:154–7. 10.1177/1039856214568216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor JA, Lawton-Smith S, Bullmore H. Supervised community treatment: Does it facilitate social inclusion? A perspective from approved mental health professionals (AMHPs). Ment Health Soc Inclusion. (2013) 17:43–8. 10.1108/20428301311305304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sullivan WP, Carpenter J, Floyd DF. Walking a tightrope: Case management services and outpatient commitment. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. (2014) 13:350–63. 10.1080/1536710X.2014.961116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stensrud B, Høyer G, Beston G, Granerud A, Landheim AS. “Care or control?”: A qualitative study of staff experiences with outpatient commitment orders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2016) 51:747–55. 10.1007/s00127-016-1193-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pridham KF, Nakhost A, Tugg L, Etherington N, Stergiopoulos V, Law S. Exploring experiences with compulsory psychiatric community treatment: A qualitative multi-perspective pilot study in an urban Canadian context. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2018) 57:122–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riley H, Lorem GF, Høyer G. Community treatment orders–what are the views of decision makers? J Ment Health. (2018) 27:97–102. 10.1080/09638237.2016.1207230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stuen HK, Landheim A, Rugkåsa J, Wynn R. Responsibilities with conflicting priorities: A qualitative study of ACT providers’ experiences with community treatment orders. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:1–11. 10.1186/s12913-018-3097-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burns T. Community supervision orders for the mentally ill: Mental health professionals’ attitudes. J Ment Health. (1995) 4:301–8. 10.1080/09638239550037596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Atkinson JM, Gilmour WH, Dyer JA, Hutcheson F, Patterson L. Consultants’ views of leave of absence and community care orders in Scotland. Psychiatr Bull. (1997) 21:91–4. 10.1192/pb.21.2.91 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhatti V, Kenney-Herbert J, Cope R, Humphreys M. The mental health act 1983: Views of section 12 (2)-approved doctors on selected areas of current legislation. Psychiatr Bull. (1999) 23:534–6. 10.1192/pb.23.9.534 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crawford M, Hopkins W, Henderson C, Hotopf M. Concerns over reform of the mental health act. Br J Psychiatry. (2000) 177:563. 10.1192/bjp.177.6.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Atkinson M, Harper Gilmour W. Views of consultant psychiatrists and mental health officers in Scotland on the mental health (patients in the community) Act 1995. J Ment Health. (2000) 9:385–95. 10.1080/713680262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O’Reilly RL, Keegan DL, Elias JW. A survey of the use of community treatment orders by psychiatrists in Saskatchewan. Can J Psychiatry. (2000) 45:79–81. 10.1177/070674370004500112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pinfold V, Rowe A, Hatfield B, Bindman J, Huxley P, Thornicroft G, et al. Lines of resistance: Exploring professionals’ views of compulsory community supervision. J Ment Health. (2002) 11:177–90. 10.1080/09638230020023570-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Romans S, Dawson J, Mullen R, Gibbs A. How mental health clinicians view community treatment orders: A National New Zealand Survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2004) 38:836–41. 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01470.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Christy A, Petrila J, McCranie M, Lotts V. Involuntary outpatient commitment in Florida: Case information and provider experience and opinions. Int J Forensic Ment Health. (2009) 8:122–30. 10.1080/14999010903199340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Manning C, Molodynski A, Rugkåsa J, Dawson J, Burns T. Community treatment orders in England and Wales: National survey of clinicians’ views and use. Psychiatrist. (2011) 35:328–33. 10.1192/pb.bp.110.032631 27837467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coyle D, Macpherson R, Foy C, Molodynski A, Biju M, Hayes J. Compulsion in the community: mental health professionals’ views and experiences of CTOs. Psychiatrist. (2013) 37:315–21. 10.1192/pb.bp.112.038703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gupta J, Hassiotis A, Bohnen I, Thakker Y. Application of community treatment orders (CTOs) in adults with intellectual disability and mental disorders. Adv Ment Health Intellect Disabil. (2015) 9:196–205. 10.1108/AMHID-02-2015-0007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hsieh M, Wu H, Chou FH, Molodynski A. A cross cultural comparison of attitude of mental healthcare professionals towards involuntary treatment orders. Psychiatr Q. (2017) 88:611–21. 10.1007/s11126-016-9479-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Waardt D, van der Heijden F, Rugkåsa J, Mulder CL. Compulsory treatment in patients’ homes in the Netherlands: what do mental health professionals think of this? BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:80. 10.1186/s12888-020-02501-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moleon Ruiz A, Fuertes Rocanin JC. Psychiatrists’ opinion about involuntary outpatient treatment. Rev Esp Sanid Penit. (2020) 22:39–45. 10.18176/resp.0006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McFarland BH, Faulkner LR, Bloom JD, Hallaux RJ, Bray JD. Investigators’ and judges’ opinions about civil commitment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law Online. (1989) 17:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Segal SP, Hayes SL, Rimes L. The utility of outpatient commitment: Acute medical care access and protecting health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2018) 53:597–606. 10.1007/s00127-018-1510-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Muusse C, Kroon H, Mulder CL, Pols J. Working on and with relationships: Relational work and spatial understandings of good care in community mental healthcare in trieste. Cult Med Psychiatry. (2020) 44:544–64. 10.1007/s11013-020-09672-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.O’Reilly R, Vingilis E. Are randomized control trials the best method to assess the effectiveness of community treatment orders? Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. (2018) 45:565–74. 10.1007/s10488-017-0845-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.