ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is a leading cause of gastrointestinal infections and in the present day is a major concern for global health care system. The unavailability of specific antibiotics for CDI treatment and its emerging cases worldwide further broaden the challenge to control CDI.

Methods:

The availability of a large number of genome sequences for C. difficile and many bioinformatics tools for genome analysis provides the opportunity for in silico pangenomic analysis. In the present study, 97 strains of C. difficile were used for pangenomic studies and characterized for their phylogenomic and functional analysis.

Results:

Pangenome analysis reveals open pangenome of C. difficile and high genetic diversity. Sequence and interactome analysis of 1,481 core genes was done and eight potent drug targets are identified. Three drug targets, namely, aminodeoxychorismate synthase (PabB), D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase (DD-CPase) and undecaprenyl diphospho-muramoyl pentapeptide beta-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase (MurG transferase), have been reported as drug targets for other human pathogens, and five targets, namely, bifunctional diguanylate cyclase/phosphodiesterase (cyclic-diGMP), sporulation transcription factor (Spo0A), histidinol-phosphate transaminase (HisC), 3-deoxy-7-phosphoheptulonate synthase (DAHP synthase) and c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase (PdcA), are novel.

Conclusion:

The suggested potent targets could act as broad-spectrum drug targets for C. difficile. However, further validation needs to be done before using them for lead compound discovery.

Keywords: Clostridioides difficile, Drug target, Genome, Inhibition, Phylogenomics

Introduction

Clostridioides difficile, earlier known as Clostridium difficile, is a toxin-producing Gram-positive, anaerobic bacteria (1). During infection, it releases toxins that disrupt the intestinal epithelia, resulting in a variety of diseases ranging from mild, self-limiting diarrhoea to the fatal pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) (2-5). During the past two decades, there has been dramatic increase in the incidence and severity of C. difficile infection (CDI) (6,7). CDI is usually followed by the antibiotic treatment that impairs the protective gut microflora (8).

C. difficile was first identified from microbial flora of faeces of healthy newborn infants and was considered that it has no deleterious effects in human (9). But later on, it was identified as the cause of antibiotic-associated PMC (10). C. difficile has been reported to have genetic heterogeneity because of its wide ecological adaptability. Hence, in the past 20 years, significant changes in CDI epidemiology have been reported (11). The differences in the severity of the infection, presence of pathogen at multiple sites (human, animal and environment) and their genetic differences have revived interest in the genomic comparison of C. difficile.

Several strains of C. difficile have been isolated and sequenced from different ecological niches; these sequences were procured for genomic comparison. The availability of genome sequence and further development in genomics and related sciences has provided a platform to understand the functions of various proteins encoded by its genome. The concept of pangenome can be applied to identify different genomes: core genome, that is, genes present in all strains of the dataset; dispensable or accessory genome, which are genes present in few strains of the dataset; and strain specific or unique genome, which are genes present in only one strain and absent in others (12). Core gene(s) can be utilized to identify the drug targets and design broad-spectrum antibiotics for pathogenic species, whereas accessory and unique genes are supposed to give them advantage in survival, pathogenicity or habitat adaptation (13). The analysis of gene functions reveals their incorporation in different genes and their proteins, which are functional in various metabolic processes that help pathogens to survive in the different ecological niches (14).

There are various bioinformatics approaches to investigate the drug target from the genome such as ligand-based interaction fingerprint, proteochemometrics modelling, linear interaction energy modelling and many more (15). Here we have used the core genome of C. difficile to identify the drug target by an integrative approach using sequence and interactome analysis. Conventional methods for drug discovery are very costly and time consuming; however, using computer analysis at initial stages can reduce the cost and time. In the present study, pangenome analysis was done and its core genome has been used to identify the drug targets. This method has been developed for the first time to identify the drug targets from the core genome of C. difficile, which can be used in the future for other pathogens too.

Methodology

Collection of genomic data

The strains of C. difficile isolated from almost all the geographical regions of the world were chosen for the present study. The complete genome sequences of these 97 C. difficile strains and their associated proteomes were retrieved from the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (16). The assembly levels of all these genomes were complete, that is, all the expected necessary chromosomes are present with no gaps.

Pangenome analysis

Pangenome analysis was conducted on these 97 strains of C. difficile using the Bacterial Pan Genome Analysis (BPGA) tool (17). For this, we have used USEARCH algorithm to generate orthologous protein clusters with the default threshold of 50% identity (18). By examining 20 permutations at random and giving median values after each genome is added, the pan and core genome size is determined. By comparing the common gene and unique gene families to the entire genome, core and pan genome curves, respectively, are created. In addition, it also generates the pan phylogeny using the pan matrix data. Using neighbour-joining method, a pangenome tree was constructed with a default combination value of 20 iterations.

Functional analysis

All the accessory and unique genes were subjected to functional analysis using protein BLAST against COG (Clusters of Orthologous Genes) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) databases (19,20). The percentage frequencies of these COG and KEGG categories are calculated for each gene and their outputs are generated in the form of charts.

Identification of drug targets

Core genome obtained from pangenome analysis was used to identify the potent drug targets. Initially, all the core genes were subjected to BLAST search against human (21). Genes with the E-value greater than 1 × 10–3 were considered as non-homologous. This is done to reduce the cross-reactivity with the human genome and to decrease drug toxicity. The resultant non-homologous genes (to human) were subjected to BLAST against DEG (Database of Essential Genes) to identify the genes that were essential for bacterial sustainability. DEG contains experimentally validated genes of many genera that are essential for survival (22). To shortlist essential genes, E-value <0.0001 and bit score >100 was used. The essential genes involved in vital function are targeted, such that the pathogen is affected and killed. All non-homologous and essential genes were subjected to virulence study. VFDB (Virulence Factor Database) is a comprehensive database that provides information about virulence factors, which are the gene products that help the pathogen to grow inside host and increase its ability to cause disease (23).

All the selected proteins were filtered on the basis of their physicochemical properties such as number of amino acids, molecular weight, isoelectric point (pI), GRAVY (grand average of hydropathicity) value, aliphatic index and subcellular localization. Except subcellular localization, all the parameters are calculated using Protparam tool and subcellular localization is predicted using CELLO (24,25). Sequences with less than 100 amino acids called peptides are excluded from the present study. Similarly, drugs are more accessible to low molecular weight targets, therefore sequences with more than 75 kDa are also excluded (26). The drug targets having low pI have been included in this study, which is in accordance with the study of Bakheet and Doig (27). In addition, negative GRAVY value indicated the hydrophilic nature of drug target and higher value of aliphatic index indicates thermostability (28,29). All extracellularly localized proteins were also excluded from the study, these being secreted outside the cell (30).

Interactome analysis

To search the key proteins (from selected proteins), the choke point analysis using pathway tool is performed to find out the proteins which were specific in the metabolic network and whose function cannot be replaced by any other protein (31). A choke point protein is compulsory for any pathway and is essential for pathogen survival. Targeting choke point protein affects the metabolic pathway, which results in death of the pathogen. Further analysis was done using interactome studies, in which the input of all choke point proteins was given to the STRING database and network was created at high confidence level (32). The metabolic functional interaction was created using various methods such as gene fusion, neighbourhood, co-occurrence, co-expression and text mining. The interactome was downloaded from STRING in xml format and its analysis was done using cytoscape (33).

In cytoscape, various critical network parameters such as clustering coefficient, characteristic path length and network centralization were calculated for each node of the network. Clustering coefficient Cn for node n was calculated using:

Cn = 2en /k(kn – 1)

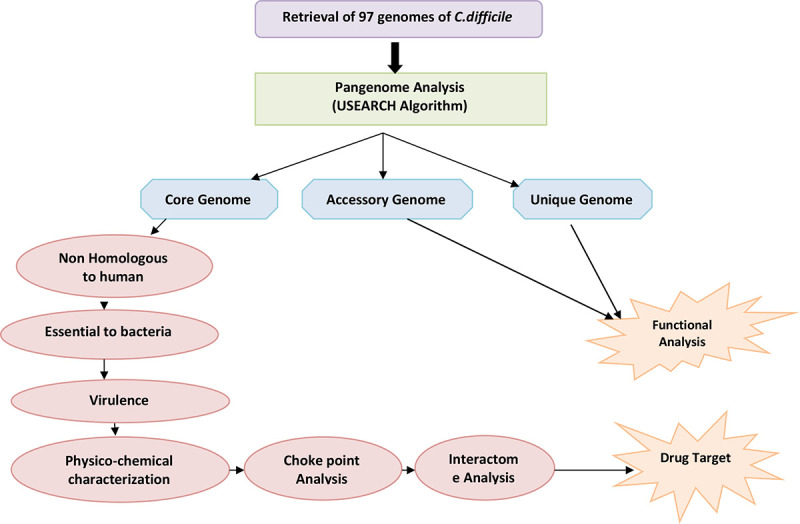

where en is the number of connected pairs between all neighbours of n and kn is the number of neighbours. Characteristic path length is the distance between nodes. Network centralization is the measure of network association around the central node; node having value close to 1 is central to network and value near to 0 shows decentralization. The values for clustering coefficient and characteristic path length are calculated for a node as well as after deleting the node. The difference in these two values shows the impact of node in the network (33). The complete methodology is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1 -.

Flowchart depicting the workflow of the methodology adopted.

Results and discussion

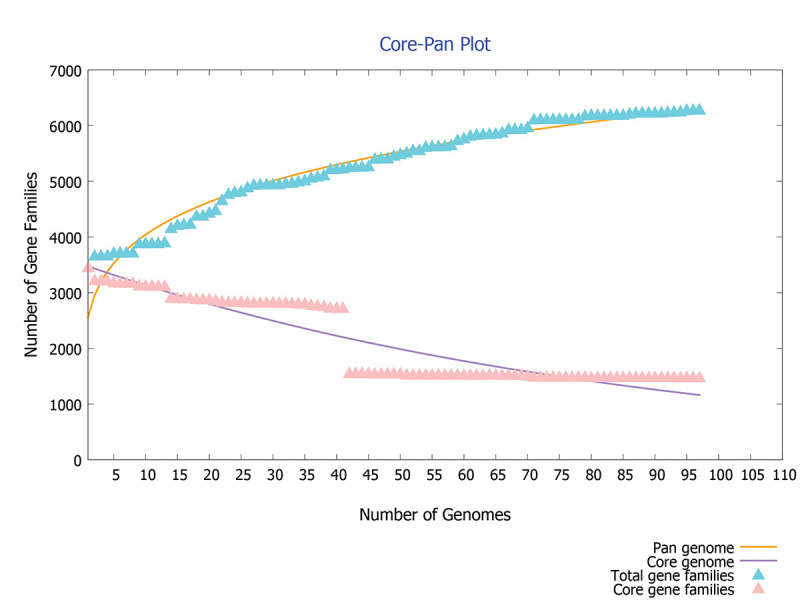

The 97 complete genomes and associated proteomes of C. difficile available till the present study were downloaded from the NCBI. Their information such as accession number, name of the strain, country from where isolated and genome statistics is provided in Supplementary File 1. The pangenome analysis of these 97 strains reveals 6,286 gene families (pangenome), out of which 1,481 are core genes (present in all species). Thus the core genes form 23.5% of the total genome, which signifies a high genetic diversity among different strains. The same feature is represented in core-pan genome plot (Fig. 2). As the genomes are added, the size of pangenome increases, whereas the size of core genome declines. The curve of pangenome (yellow colour) is still progressing, indicating the likelihood of addition of more genes, that is, global gene repertoire is likely to change in the near future and its pangenome is almost open.

Fig. 2 -.

Core-pan plot of 97 strains of C. difficile genome.

The power law regression model equation,

f(x) = a.Xb

where f(x) is the pangenome size, X is the number of genomes used, and a and b are fitting parameters used to find the openness and closeness of pangenome, has been used in the present study (17). In our study with C. difficile genes, the values of f(x) = 6,286, X = 97, a = 2687.17 and b = 0.185459 indicated that the pangenome is open at b > 0; otherwise, the pangenome would be considered to be closed. The value of b = 0.185459 indicates that the pangenome is open but soon may be closed with increase in genome data. C. difficile has 186,308 accessory genes which are present in a few strains and has 976 unique genes which are present in specific strains of C. difficile. The conservation level of C. difficile does not seem to be very high. The genome level analysis reveals high genetic variability; this may be due to its existence in different niches.

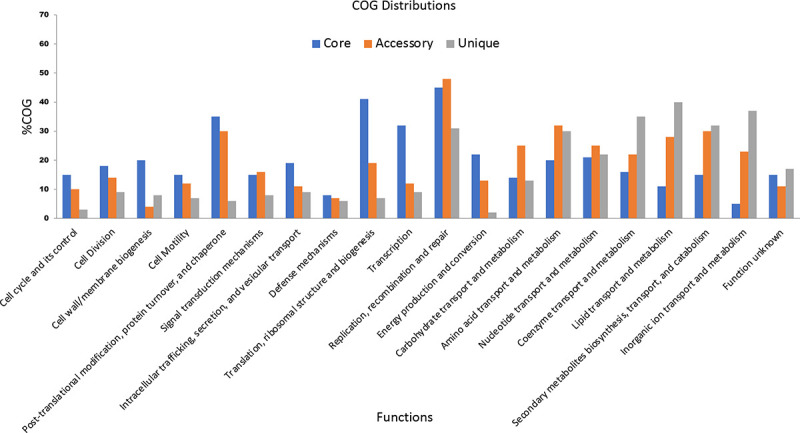

On functional analysis, it is observed that unique genes (shown in blue) and accessory genes (shown in red) are mostly responsible for metabolism and transporter function (Fig. 3). This shows that both of them are more diversified in C. difficile. Recently in 2021, Kulecka et al. also reported the variability in the metabolism genes in recurrent CDI cases (34). In addition, the core genes like PolC-type deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) polymerase III, exonuclease subunit C, cell wall–binding protein Cwp20, sensor histidine kinase KdpD and alanine-tRNA ligase (shown in green) are the genes for cellular processes such as cell division, cell cycle and its control, cell motility, cell wall/membrane biogenesis, transcription, translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis, and are mostly conserved. This signifies that genes involved in important cellular mechanism are conserved, while genes required to adapt to the new ecological niches are variable.

Fig. 3 -.

Functional analysis of various core, accessory and unique genes using COG and KEGG distributions.

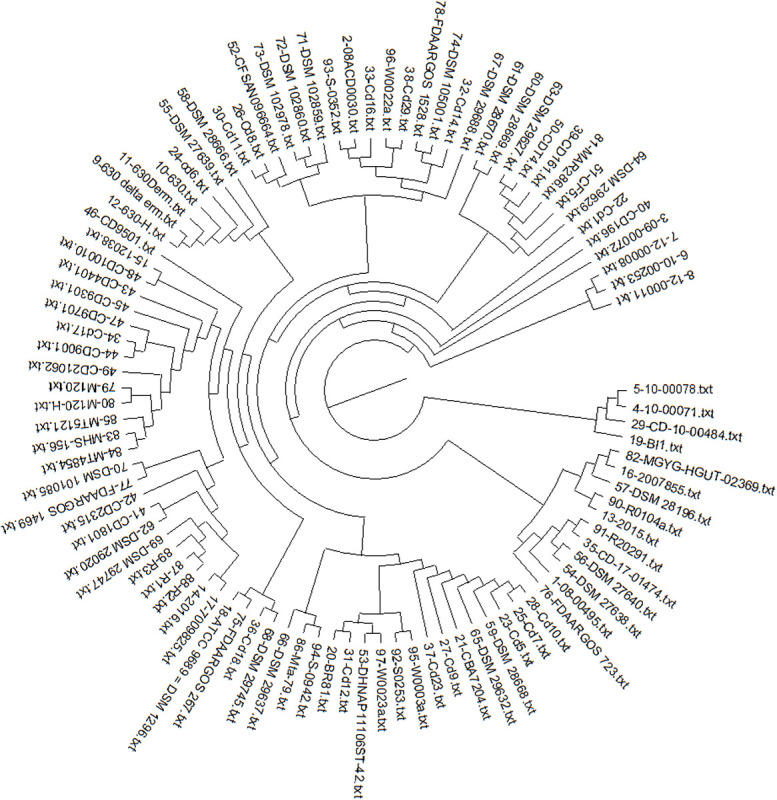

The pan-phylogeny-based phylogenetic tree is shown in Figure 4. It is observed that strains are divided into different clades based on genome similarity. On observing each clade, it is noticed that similarity is mainly based on the country from where the samples are isolated. It suggests that C. difficile adapts to different environmental conditions by expression of relative proportions of the different gene products. For example, strains Cd9, Cd12, MT5121, Cd23 and W0023a are all assembled in one clade and are isolated from the USA. Similarly strains CD-10-00484, 10-00078, DSM 102860, DSM 102978 and DSM 29745 isolated from Germany show genome similarity and are assembled in one clade.

Fig. 4 -.

Pan phylogeny–based phylogenetic tree of 97 strains of C. difficile.

With high genetic variability and drug resistance for CDI, it is very necessary to design a drug that targets the core genes of the pathogen, as core genes are present in all the strains of the pathogen and are essential for the survival of the pathogen. Therefore, targeting core gene will surely help to overcome CDI. We have used an integrative approach based on sequence and interactome analysis to find the drug target against C. difficile.

From the core genome, genes that are homologous to humans are excluded in the first step, as it may adversely affect the host metabolism. A total of 1,130 proteins are found to be non-homologous to human (Supplementary File 2). On further screening, essential proteins that are vital for the survival of pathogens are searched using DEG. Among them, 370 proteins were found to be essential and crucial for C. difficile survival (Supplementary File 2). Essential proteins were further screened for their virulence, as these factors are responsible for pathogenesis. From 370 essential proteins, 130 proteins were found to be virulence-associated factors (Supplementary File 2).

All 130 proteins were checked for their physicochemical properties. Proteins having more than 100 amino acids, less molecular weight, low pI, negative GRAVY value, high aliphatic index and membrane or cytoplasmic localization were further considered (26-30). All these are the physicochemical properties required for the potent drug target. A total of 94 proteins were obtained after all physicochemical checks (Supplementary File 2); they are further used for choke point analysis.

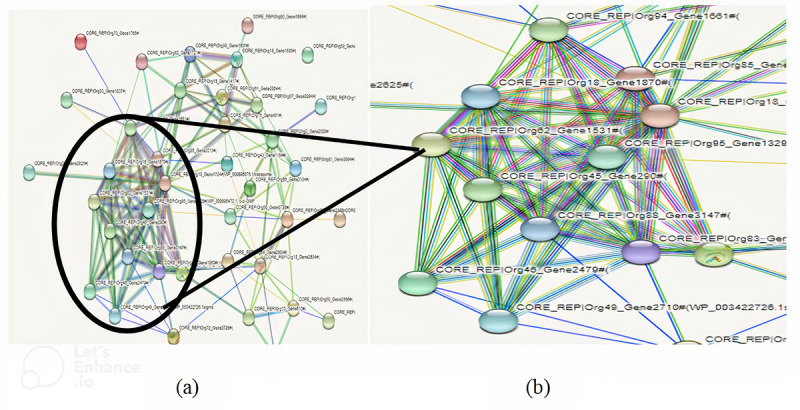

On choke point analysis, only 39 proteins involved in the unique metabolic pathways were identified (Supplementary File 2). For these 39 proteins, interactome is created using STRING as shown in Figure 5.

Fig. 5 - .

A) Interactome created using STRING. B) Zoomed view of interactome.

On interactome analysis with cytoscape, eight potent drug targets were found. Their interactome analysis results are shown in Table I. Out of the eight drug targets, three targets, namely, aminodeoxychorismate synthase (PabB), D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase (DD-CPase) and undecaprenyl diphospho-muramoyl pentapeptide beta-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase (MurG transferase) were identified which have been previously reported (35).

TABLE I -.

Interactome analysis of potent eight drug targets

| Sl. no | Sequence no. | Target name | Clustering coefficient | Characteristic path length | Network centralization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before N.D. | After N.D. | Before N.D. | After N.D. | ||||

| 1. | Org18_Gene1417 | Aminodeoxychorismate synthase (PabB) | 0.666 | 0.397 | 3.98 | 2.76 | 0.325 |

| 2. | Org18_Gene1870 | Bifunctional diguanylate cyclase/phosphodiesterase (cyclic-diGMP) | 0.863 | 0.425 | 2.36 | 1.83 | 0.693 |

| 3. | Org11_Gene1255 | Sporulation transcription factor (Spo0A) | 0.99 | 0.725 | 3.26 | 2.98 | 0.523 |

| 4. | Org39_Gene1501 | Histidinol-phosphate transaminase (HisC) | 0.356 | 0.120 | 2.35 | 1.25 | 0.364 |

| 5. | Org82_Gene1721 | 3-Deoxy-7-phosphoheptulonate synthase (DAHP synthase) | 0.70 | 0.530 | 3.29 | 2.98 | 0.452 |

| 6. | Org18_Gene2684 | Undecaprenyl diphospho-muramoyl pentapeptide beta-N-acetyl glucosaminyltransferase (MurG transferase) | 0.893 | 0.452 | 4.63 | 1.88 | 0.832 |

| 7. | Org50_Gene2566 | D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase (DD-CPase) | 0.528 | 0.257 | 3.00 | 2.08 | 0.452 |

| 8. | Org95_Gene1329 | c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase (PdcA) | 0.731 | 0.458 | 4.11 | 3.37 | 0.673 |

PabB is involved in folate synthesis; its inhibition affects DNA and protein synthesis adversely. It is reported that it is targeted by the antibiotics 6-fluoroshikimic acid and atrop-abyssomycin C (35). Bifunctional diguanylate cyclase/phosphodiesterase (cyclic-diGMP) is a messenger protein that regulates motility, virulence and biofilm formation attributed to pathogenicity (36,37). Inhibition of cyclic-diGMP affects many processes of the pathogen that result in the death of the pathogen. Another identified target is sporulation transcription factor Spo0A, which is a key factor for entry into sporulation in stress conditions and biofilm formation (38).

Histidinol-phosphate transaminase (HisC) is a transferase that is mainly involved in transferring nitrogenous group. It is involved in synthesis and metabolism of many amino acids (39). 3-deoxy-7 phosphoheptulonate synthase (DAHP synthase) is involved in the shikimate pathway and is also responsible for the synthesis of aromatic amino acids, such as tyrosine, phenylalanine and tryptophan which are essential for bacterial metabolism (40). Another identified drug target, MurG transferase, is involved in the peptidoglycan biosynthesis and is reported to be the drug target for many pathogens such as Neisseria meningitidis (41), Acinetobacter baumannii (42) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (43).

Another identified potent target, DD-CPase is a reported drug target and is involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis and remodelling and is inhibited by β-lactam antibiotics (44). C-di-GMP phosphodiesterase (PdcA) is a potent drug target that regulates bacterial pathogenesis as well as is involved in surface adherence and biofilm development (45).

Conclusion

CDI is a challenging situation worldwide. The unavailability of specific antibiotic and emergence of antibiotic resistance against C. difficile is a matter of concern. Diversity in C. difficile genome drives the genomic comparison of the pathogen. Pangenome analysis reveals the open pangenome of C. difficile that may be soon closed. The diversity is due to its adaptability in different niches and different hosts. Due to such genomic diversity, a drug target can be designed only from its core gene, whose inhibition affects all strains of C. difficile. From sequence and interactome analysis of core genes, eight potent drug targets are reported. Out of these, three of the targets – PabB, DD-CPase and MurG transferase – are also reported as drug target for other pathogens, whereas bifunctional cyclic-diGMP, Spo0A, HisC, DAHP synthase and PdcA are newly reported targets. This indicates that the method originated in the present study has a high rate of success and saves considerable time and money. The same method can be used for other pathogens also.

Limitations of the study

This computational method uses multiple genomes with complete genome assembly, therefore this method cannot be employed for pathogens whose majority of the strains have not been sequenced. Pangenome analysis can only be performed if multiple sequenced strains are available for the organism. Pangenomics can easily be done only when proper software or tool is available; it is very complex to handle the genome manually. Another limitation with this study is the use of in silico method for drug target identification that saves considerable time and money, but its accuracy is still questionable. We have used the core genes which are conserved and involved in essential processes for drug target identification, but the drug targets from novel genes which the bacteria inherits from its adaptation in new niches cannot be considered in this type of study.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the facilities of the Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India, New Delhi (DBT), under the Bioinformatics Sub Centre as well as M.Sc. Biotechnology programme used in the present work.

Disclosures

Conflict of interest: The authors confirm that they have no conflict of interest.

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

This article includes supplementary material

References

- 1.Zhu D, Sorg JA, Sun X. Clostridioides difficile biology: sporulation, germination, and corresponding therapies for C. difficile infection. Vol. 8. Front Cell Infect Microbiol; 2018. p. 29.PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(16):1539–1548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1403772. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rupnik M, Wilcox MH, Gerding DN. Clostridium difficile infection: new developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(7):526–536. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2164. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JS, Monaghan TM, Wilcox MH. Clostridium difficile infection: epidemiology, diagnosis and understanding transmission. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(4):206–216. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.25. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abt MC, McKenney PT, Pamer EG. Clostridium difficile colitis: pathogenesis and host defence. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14(10):609–620. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.108. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim SC, Knight DR, Riley TV. Clostridium difficile and one health. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(7):857–863. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.10.023. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):825–834. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seekatz AM, Young VB. Clostridium difficile and the microbiota. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(10):4182–4189. doi: 10.1172/JCI72336. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall IC, O’Toole E. Intestinal flora in new-born infants: with a description of a new pathogenic anaerobe, Bacillus difficilis. AMA Am J Dis Child. 1935;49(2):390–402. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1935.01970020105010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartlett JG, Moon N, Chang TW, Taylor N, Onderdonk AB. Role of Clostridium difficile in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75(5):778–782. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(78)90457-2. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight DR, Imwattana K, Kullin B et al. Major genetic discontinuity and novel toxigenic species in Clostridioides difficile taxonomy. eLife. 2021;10:e64325. doi: 10.7554/eLife.64325. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vernikos G, Medini D, Riley DR, Tettelin H. Ten years of pan-genome analyses. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;23:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.016. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tettelin H, Masignani V, Cieslewicz MJ et al. Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial “pan-genome”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(39):13950–13955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506758102. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croll D, McDonald BA. The accessory genome as a cradle for adaptive evolution in pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(4):e1002608. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002608. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katsila T, Spyroulias GA, Patrinos GP, Matsoukas MT. Computational approaches in target identification and drug discovery. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2016;14:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2016.04.004. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sayers EW, Beck J, Bolton EE et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D10–D17. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa892. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhari NM, Gupta VK, Dutta C. BPGA – an ultra-fast pan-genome analysis pipeline. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):24373. doi: 10.1038/srep24373. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4(1):41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye J, McGinnis S, Madden TL. BLAST: improvements for better sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server issue):W6–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl164. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo H, Lin Y, Liu T et al. DEG 15, an update of the Database of Essential Genes that includes built-in analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D677–D686. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa917. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu B, Zheng D, Jin Q, Chen L, Yang J. VFDB 2019: a comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D687–D692. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1080. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A et al. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. The proteomics protocols handbook. 2005:571–607. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-890-0:571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu CS, Chen YC, Lu CH, Hwang JK. Prediction of protein subcellular localization. Proteins. 2006;64(3):643–651. doi: 10.1002/prot.21018. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gashaw I, Ellinghaus P, Sommer A, Asadullah K. What makes a good drug target? Drug Discov Today. 2011;16(23-24):1037–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.09.007. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakheet TM, Doig AJ. Properties and identification of human protein drug targets. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(4):451–457. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp002. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solanki V, Tiwari V. Subtractive proteomics to identify novel drug targets and reverse vaccinology for the development of chimeric vaccine against Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9044. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26689-7. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang KY, Yang JR. Analysis and prediction of highly effective antiviral peptides based on random forests. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070166. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar A, Ahmad A, Vyawahare A, Khan R. Membrane trafficking and subcellular drug targeting pathways. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:629. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00629. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karp PD, Paley S, Romero P. The pathway tools software. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(suppl 1):S225–S232. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.S225. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H et al. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein–protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 Jan 4;45(D1):D362–D368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw937. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demchak B, Hull T, Reich M et al. Cytoscape: the network visualization tool for GenomeSpace workflows. F1000 Res. 2014;3:151. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.4492.2. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kulecka M, Waker E, Ambrozkiewicz F et al. Higher genome variability within metabolism genes associates with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02090-9. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahr T, Ravanel S, Basset G, Nichols BP, Hanson AD, Rébeillé F. Folate synthesis in plants: purification, kinetic properties, and inhibition of aminodeoxychorismate synthase. Biochem J. 2006;396(1):157–162. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051851. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nesbitt NM, Arora DP, Johnson RA, Boon EM. Modification of a bi-functional diguanylate cyclase-phosphodiesterase to efficiently produce cyclic diguanylate monophosphate. Biotechnol Rep (Amst). 2015;7:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2015.04.008. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phippen CW, Mikolajek H, Schlaefli HG, Keevil CW, Webb JS, Tews I. Formation and dimerization of the phosphodiesterase active site of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa MorA, a bi-functional c-di-GMP regulator. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(24):4631–4636. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.11.002. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujita M, Losick R. The master regulator for entry into sporulation in Bacillus subtilis becomes a cell-specific transcription factor after asymmetric division. Genes Dev. 2003;17(9):1166–1174. doi: 10.1101/gad.1078303. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sivaraman J, Li Y, Larocque R, Schrag JD, Cygler M, Matte A. Crystal structure of histidinol phosphate aminotransferase (HisC) from Escherichia coli, and its covalent complex with pyridoxal-5′-phosphate and l-histidinol phosphate. J Mol Biol. 2001;311(4):761–776. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4882. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Oliveira MD, Araújo JO, Galúcio JMP, Santana K, Lima AH. Targeting shikimate pathway: in silico analysis of phosphoenolpyruvate derivatives as inhibitors of EPSP synthase and DAHP synthase. J Mol Graph Model. 2020;101:107735. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2020.107735. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tripathi P, Tripathi V. In: Kesari KK, editor. Perspectives in Environmental Toxicology; 2017. Determination of murG transferase as a potential drug target in Neisseria meningitides by spectral graph theory approach. pp. 147–160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amera GM, Khan RJ, Pathak A, Jha RK, Muthukumaran J, Singh AK. Screening of promising molecules against MurG as drug target in multi-drug-resistant-Acinetobacter baumannii – insights from comparative protein modeling, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020;38(17):5230–5252. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2019.1700167. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Konyariková Z, Savková K, Kozmon S, Mikušová K. Biosynthesis of galactan in Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a viable TB drug target? Antibiotics (Basel). 2020;9(1):20. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9010020. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rioseras B, Yagüe P, López-García MT et al. Characterization of SCO4439, a D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase involved in spore cell wall maturation, resistance, and germination in Streptomyces coelicolor. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):21659. doi: 10.1038/srep21659. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamayo R. Cyclic diguanylate riboswitches control bacterial pathogenesis mechanisms. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(2):e1007529. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007529. PubMed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]