Abstract

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder with manifestations somatic resulting from reliving the trauma. The therapy for the treatment of PTSD has limitations, between reduced efficacy and “PTSD pharmacotherapeutic crisis”. Scientific evidence has shown that the use of ketamine has benefits for the treatment of depressive disorders and other symptoms present in PTSD compared to other conventional therapies. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the available evidence on the effect of ketamine in the treatment of post-traumatic stress. The systematic review and the meta-analysis were conducted following PRISMA guidelines and RevManager software, using randomized controlled trials and eligible studies of quality criteria for data extraction and analysis. The sample design evaluated included the last ten years, whose search resulted in 594 articles. After applying the exclusion criteria, 35 articles were selected, of which 14 articles were part of the sample, however, only six articles were selected the meta-analysis. The results showed that the ketamine is a promising drug in the management of PTSD with effect more evident performed after 24 h evaluated by MADRS scale. However, the main limitations of the present review demonstrate that more high-quality studies are needed to investigate the influence of therapy, safety, and efficacy.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, mental disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), stress disorders, ketamine

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a neurological disorder characterized by the individual's exposure to threatening and distressing events with a potential risk of death. This disorder can also be triggered by emotional triggers such as thoughts, dreams, or memories of the event, which cause the affected person to relive memories of trauma and intense negative and distressing emotions. 1 Other diseases that affect mental health, such as depression and anxiety, when associated with PTSD, favor a greater severity of symptoms.2,3

PTSD can manifest acutely or chronically. However, in chronic condition, it becomes disabling with a potential increase in the risk of completed suicide in individuals. 2 It is estimated that about 8% of the world's population has experienced or will experience a PTSD episode in their lifetime. 4 Nevertheless, professions such as civil and military police, firefighters, and emergency medical service workers 5 have a higher prevalence in the development of this disorder. In most cases, people who develop the disorder have been through situations that involved accidents with serious injuries, physical aggression, or sexual abuse. 1 However, news of global events such as pandemics (COVID-19) and war also cause a variety of neuropsychological reactions stemming from acute stress symptoms such as avoidance, symptoms of negative alteration of thoughts and emotions, or symptoms of hyperactivation, mostly consummated in patients with a prior history of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 6

Previous studies involving meta-analysis of pharmacological treatment of PTSD 7 point out that the use of the group of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) , 8 such as sertraline and paroxetine or inhibitor noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) venlafaxine, 9 are used in treatment but, unfortunately, fail to completely remit PTSD symptoms. Thus, there is a limitation to the use of these drugs 10 with inconsistent findings of pharmacological efficacy in treatment compared to placebo control groups.

PTSD affects the physiobiological and neurochemical functions of central brain regions such as the amygdala, hypothalamus, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. However, amygdala rupture is correlated with negative emotional processing seen in PTSD patients caused by adrenal gland stimulation that affects the increased release of the stress hormone cortisol, resulting in dysregulation of the catecholamine neurocircuitry. 11 These neurochemical changes also affect other circuits such as cannabinoids, serotonergic, glutamatergic, GABA, endogenous peptides, and neuropeptides making them pharmacological therapeutic targets that can be used for the treatment of PTSD. 12

Preclinical studies and clinical trials have demonstrated the pharmacotherapeutic potential of using glutamate modulators or NMDA receptor antagonism as beneficial for the treatment of PTSD. Excitotoxicity caused by glutamate can be potentiated by trauma and stress, which correlates with atrophy in the dendritic spines and neuronal death in the hippocampus region, explaining, in part, the failure or dysregulation of memory – a clinical feature present in this disease. 11 Ketamine is traditionally used as an adjuvant drug in general anesthesia. Nevertheless, its antagonistic effect on the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-like glutamate receptor shows suggestive evidence of therapeutic potential for the treatment of PTSD 13 or depression. 14

Many studies have been performed on the effect of ketamine on stress-related disorders. Possible molecular mechanisms are correlated with a dose-dependent response and treatment time.2,4,13,15–18 Recently, the S-enantiomer of ketamine was approved in 2019; your rapid actions blocking the N-methyl-D-aspartate site (receptor antagonist of NMDA) help control symptoms of depression and acute suicidal ideation or behavior. 19 Pré-clinical studies showed that administration at higher doses might also bind to the opioid mu and sigma receptors; these actions correlate with the adverse and collateral effects.17,20 Thus, given the divergence of information on efficacy and correlation with the duration of therapy, this study aims to analyze the available evidence on the effect of ketamine in the treatment of post-traumatic stress.

Methodology

The search strategy and protocol for this review were registered in the PRISMA code (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) with register 10928322 with a guiding question defined as “Literature data based on human clinical trials show the existence of clear evidence of the beneficial effect of ketamine in the treatment of post-traumatic stress?”. The search for articles was established according to the inclusion criteria: time-lapse from January 2012 to March 2022, human clinical trial, ketamine, and PTSD present in the Cochrane Library, Embase, MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science and Clinical Trials. For this, the Medical Subject Headings (Mesh) descriptors “Ketamine and Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic, PTSD disorder” were used combined with the Boolean operator “AND”. For the meta-analysis, we selected only human clinical trials of ketamine therapy use. Case reports or case series were excluded. The search and selection of potential studies were performed independently by two investigators (T.R.A. and L.F.R.M) to ensure eligibility. The initial agreement in the selection of articles was calculated using Conger's generalized kappa coefficient (κ). Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the two researchers. Data from studies that met the inclusion criteria were compiled using Rayyan®.21 The methodological quality of studies and risk of bias were assessed using the RoB 2 tool using the Cochrane Collaboration criteria for randomized trials22 which classifies studies as “low risk of bias”, “high risk of bias” and “uncertain risk of bias”.

For the meta-analysis, only studies that showed methodological similarity and were classified as having a low risk of bias were selected. Data analysis was performed using RevManager software (Version 5.4. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020). The estimate of variance between studies was calculated using the Tau2 test and statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran Q test and the Higgins (I2) statistic. An I2 value of less than 50% was equivalent to no heterogeneity, while values greater than 50% were equivalent to great heterogeneity between studies.

Data were standardized using the Z score to stabilize the variance of mean differences between included studies. To account for the potential heterogeneity of the population sample in each study and the results of statistical tests of heterogeneity, a random effect model using the inverse variance method was used to combine effect sizes to estimate the mean difference and corresponding level intervals of 95% confidence level (95% CI). To explore the reasons for heterogeneity, subgroup analyzes were applied based on the instrument applied (CAPS-5, LCP-5, and MARS) and on the function of time of assessment after the intervention (baseline effect vs. first 24 hours). After treatment and baseline effect vs best effect of ketamine after 24 hours of treatment). A P value of less than 0.05 was identified as statistically significant. For statistically significant results, the effect size was estimated by measuring the correlation coefficient (r). Values of r < .20 – negligible effect; ≥.20 and ≤.49 – small effect; ≥.50 and ≤.79 – average effect; ≥.80 – high effect. 23

The Begg funnel plot and statistical tests to assess bias in the results were not performed due to the number of studies included in the meta-analysis. The Cochrane Collaboration recommends not to perform these tests in reviews of fewer than 10 studies. 24

Results

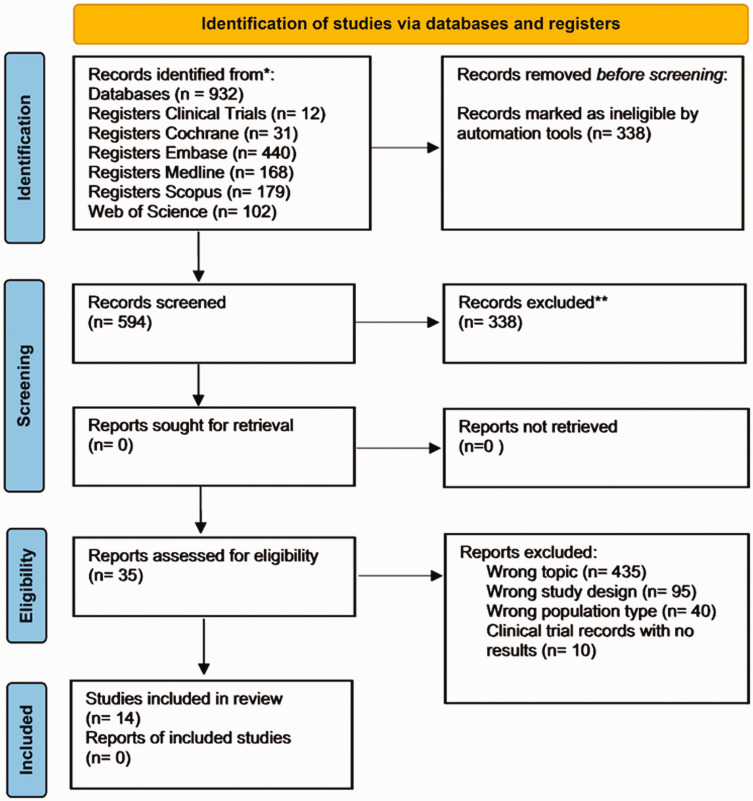

The primary search identified 932 articles, of which 338 were eliminated due to duplicity, and the 594 articles were selected for reading in the abstracts. After the process, 35 articles were evaluated as potentially eligible and retained for full reading based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these, 14 articles were included in this review. For the meta-analysis, six studies were included. The steps involved in the selection of studies are illustrated below in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Data compiled from selected articles were standardized in Table 1, which provides an overview of study characteristics, specifying last author, year, country, study type, population, age, intervention and dose (control and treatment), results, sample size, and supervision. Among the studies found, 64.28% were randomized clinical trials, 28.57% were observational cohort studies, and 7.14% were open-label proof-of-concept studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of original included studies (n = 14).

| Source Study | Country | Design of study | Total of populations | TEPT patients | TEPT patients Treated with Ketamine | Range of Age or Mean age | Regimen | Route of administration | Control/placebo | Outcomes | Time of intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Abdallah et al., 2022b) | USA | Clinical trial double blinded and randomized | 262 | 158 | 53 with 0.2 mg/kg 51 with 0,5 mg/kg | 54 to Placebo (saline) 43,2 to Standard Dose (0.5 mg/kg) 43 to Low Dose (0.2 mg/kg) | Single infusion (0.2 mg/kg) twice weeklyRepeat infusion (8 of 0,5 mg/kg) twice weekly | Intravenous | Saline | No significant evidence of the dose-related show effect of ketamine on PTSD symptoms. | 4 weeks |

| (Margaret T. Davis et al., 2021) | USA | ClinicalRandomized trial | 58 | 15 | 15 | 36,1 to dose 0.23 mg/kg followed 0,58 mg/kg 33,3 to dose 0.5 mg/kg | Single bolus infusion (0.23 mg/kg) for one minute followed by Single infusion (0,58 mg/kg) per hour over | Intravenous | Control group received constant IV infusion of 0.5 mg/kg ketamine over 40 min. | Individual with PTSD showed a great improvement in the severity of depressive symptoms at 2 hours and 1 day after ketamine administration (p's < .001, Cohen d's = 0.80–1.02) | 2 hours and 1 day after ketamine administration |

| (Sean E. Rossiter, Madison H. Fletcher, 2021) | USA | Clinical trial randomized | 83 | 10 | 10 | Ages from 18 to 75 years | Three single infusion (0.5 mg/kg) over 40 minutes for week | Intravenous | Saline | Significant change in PTSD symptoms with decrease from baseline up to 24 hours after 6th infusion (mean change in PCL-5 = 33.3, p < 0.0005, Cohen's d = 2.17) | 2 weeks |

| (Norbury et al., 2021) | USA | Clinical trial double blinded and randomized | 21 | 21 | 11 | 42,3 to Midazolam 0,045 mg/kg.42,5 to ketamine 0.5 mg/kg | Three single infusion (0.5 mg/kg) over 40 minutes for week | Intravenous | Midazolam (0,045 mg/kg × 3/week). | Ketamine makes changes to an a priori set of imaging measurements from a functional connectivity of the target neural circuit between the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and the amygdala. This increased functional connectivity between the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and the amygdala has been associated with improvements in PTSD severity. | 2 weeks |

| (Feder et al., 2021) | USA | Clinical trial double blinded and randomized | 30 | 30 | 15 | Ages of 18 to 7038.5 to Midazolam 0,045 mg/kg39.3 to ketamine 0.5 mg/kg | Six single-dose of ketamine infusions approximately three times per week over 2 consecutive | Intravenous | Six single-dose of midazolam infusions approximately three times per week over 2 consecutive | The ketamine group (67%) showed a significantly greater improvement in CAPS-5 and MADRS total scores compared to the midazolam group (20%). Repeated ketamine infusions reduce symptom severity in chronic PTSD | 2 weeks |

| (Dadabayev et al., 2020 b) | USA | Clinical trial double blinded and randomized | 41 | 20 | 10 | Ages from 29 to 65 years42.47 to ketamine 0.5 mg/kg | Single infusion of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) over 40 minutes. | Intravenous | Single infusion of Ketorolac 15 mg over 40 minutes. | The ketamine and ketorolac might offer meaningful and durable responses for both PTSD and CP symptoms that persisted for seven days after the infusion. | 1 week |

| (Pradhan et al., 2018 b) | USA | Clinical trial double blinded and randomized | 20 | 10 | 10 | Age from 24 to 60 years41,7 | Single infusion of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) over 40 minutes by one week and TIMBER interventions (12 sessions) | Intravenous | Single infusion of saline and TIMBER interventions (12 sessions) | The protocol of treatment produces one rapid and significant therapeutic response, which lasts for only 4–7 days associated with TIMBER interventions was increased to 34.44 ± 19.12 days. | One time for a week during 10 weeks |

| (Feder et al., 2014) | New York (USA) | Clinical trial double blinded and randomized | 57 | 41 | 22 | Ages from 18 to 55 years36.4 to ketamine 0.5 mg/kg 35.7 to Midazolam 0,045 mg/kg | Single infusion of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) or midazolam (0.045 mg/kg), over 40 minutes by 2 weeks | Intravenous | Midazolam (0.045 mg/kg) | The ketamine infusion shows a significant and rapid reduction in PTSD symptoms and in comorbid depressive symptoms with good tolerance and without clinically significant dissociative symptoms. | 13 days |

| (Soleimani et al., 2014) | USA | Clinical trial double blinded and randomized | 24 | 10 | 10 | Age from 18 to 80 years | Single infusion of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) or midazolam (0.045 mg/kg) over 40 minutes by seven days | Intravenous | Midazolam (0.045 mg/kg) | The ketamine shows safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy as an intervention for patients who present an elevated risk for suicidal ideation. However, the ketamine group presents headache (58.3%) and dissociative symptoms, which resolved within 4 hours of the treatment. | 5 weeks |

| (Shiroma et al., 2020) | USA | Proof-Of-Concept Study | 12 | 10 | 10 | Age from 18–75 years44,1 to ketamine 0.5 mg/kg | Single infusion of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) over 40 minutes by seven days combined with Prolonged exposure (PE) tharapy | Intravenous | None | The ketamine treatment shows rapid antidepressant and anxiolytic effects that increase patients' treatment adherence to Prolonged exposure (PE) therapy during PTSD treatment. | 10 weeks |

| (Ross et al., 2019) | USA | Cross sectional studies by observational case | 30 | 30 | 30 | Age from 18 to 75 years | Six ketamine infusions of with a dose of 1 mg/kg with a maximum of 60 mg by one hour over a 2-to 3-week | Intravenous | None | The significant change in score of self-report questionnaires and reduction of symptoms of depression measured by PHQ-9 and symptoms of PTSD measured DSM-5 (PCL-5) Checklist. | For 3 weeks |

| (Albott et al., 2018) | USA | Cohort studies | 24 | 19 | 15 | Age from 18 to 75 years52,1 to ketamine 0.5 mg/kg | Six ketamine infusions of with a dose (0.5 mg/kg) over 40 minutes by approximately three times per week during a 12 days | Intravenous | none | Repeat ketamine infusions show a PTSD remission rate of 80.0%, had a median time to relapse of 41 days, and no reports of worsening PTSD symptoms over the course of the study. | 8 weeks |

| (Hartberg et al., 2018) | Austrália | Cohort studies | 171 | 115 | 37 | Age from 21 to 84 yearsMedian of 46 to ketamine group | The sublingual dose of ketamine ranged from 0.5 to 7.0 mg/kg twice daily, 3 h apart. | Sublingual | – | Oral ketamine treatment was reduced by 70% in inpatient hospital days, and hospital admissions were reduced by 65%. No serious adverse events and no long-term negative effects are associated with ketamine | 3 years |

| (Mion et al., 2017) | France | Cohort studies | 274 | 98 | 89 | Media age of 30 years in the PTSDMedia age of 29 years in the no PTSD group | 173 ± 144 (mg) | No present | none | The post-traumatic stress disorder group that received ketamine presented minor post-traumatic episodes compared with the no PTSD group, and the ketamine administration in the traumatic military setting does not have a detrimental effect. | 3 years |

It is observed that most studies originated in the United States (85.7%), and the total number of participants was 1107 (range: 18–80), including male and female participants diagnosed with PTSD (n = 587; 53% and range: 18–80). However, considerable variation in sample sizes was observed between treatment and control in the studies, which precludes further comparison.

For most trial studies, ketamine was administered intravenously as a bolus (two trials) or fractional infusion (twenty trials) with a treatment time interval of two weeks. Interestingly, an experimental study shows sublingual administration. Most included studies show that ketamine treatment was compared with positive control midazolam.

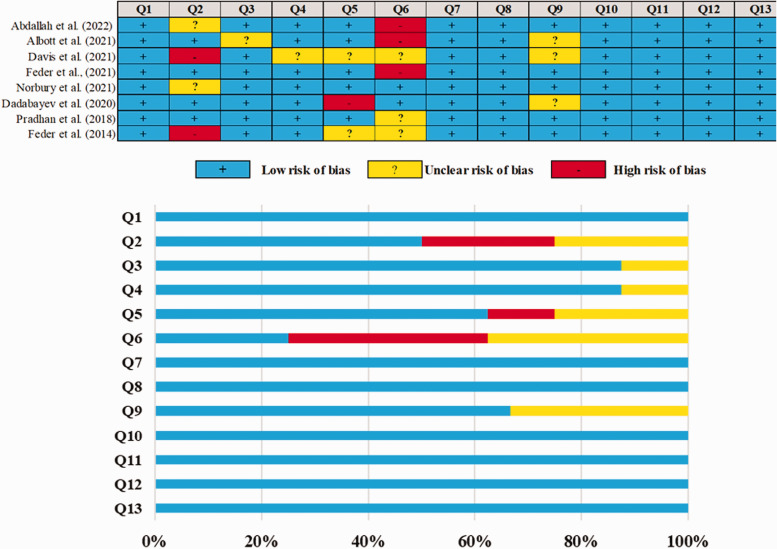

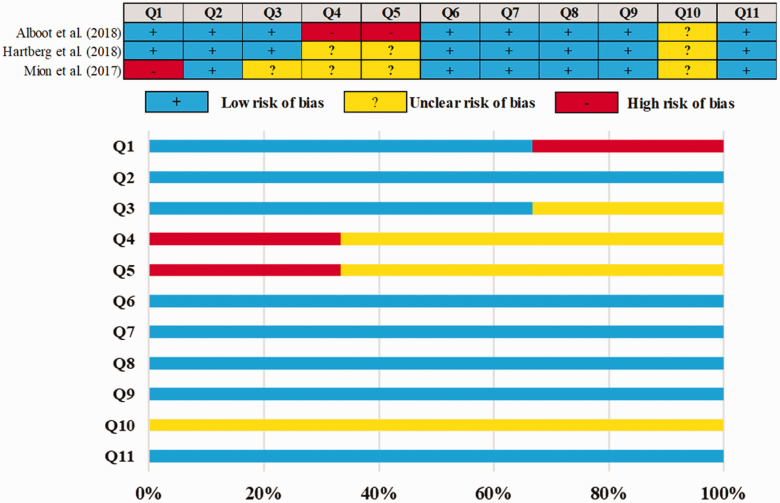

The overall risk of bias quality for all eight studies included in the meta-analysis was very high, with only a handful of questions having “low risk” domains. The risk of bias is summarized in Figure 2. It was observed that five studies did not document certain aspects of the design protocol and, therefore, lost a point for being unclear.

Figure 2.

Judgments about each methodological quality of clinical studies included in the review. (Q1 – Was true randomization used for the assignment of participants to treatment groups?; Q2 – Was allocation to treatment groups concealed?; Q3 – Were treatment groups similar at the baseline?; Q4 – Were participants blind to treatment assignment?; Q5 – Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment?; Q6 – Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment?; Q7 – Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest?; Q8 – Was follow-up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analyzed?; Q9 – Were participants analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized?; Q10 – Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups?; Q11 – Were outcomes measured in a reliable way?; Q12 – Was appropriate statistical analysis used?; Q3 – Was the trial design appropriate, and were any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial?).

The overall risk of bias is also applied to three qualitative studies summarized in Figure 3. Low scores are observed when compared to double-blind randomized controlled trials. The highlighted issues have an unclear risk of bias because they do not document specific aspects of the design protocol.

Figure 3.

Judgments about each methodological quality of clinical studies included in the review. (Q1 – Were the two groups similar and recruited from the same population?; Q2 – Were the exposures measured similarly to assign people to both exposed and unexposed groups?; Q3 – Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way?; Q4 – Were confounding factors identified?; Q5 – Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated?; Q6 – Were the groups/participants free of the outcome at the start of the study (or at the moment of exposure)?; Q7 – Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way?; Q8 – Was the follow-up time reported sufficient to be long enough for outcomes to occur?; Q9 – Was follow-up complete, and if not, were the reasons for loss to follow-up described and explored?; Q10 – Were strategies to address incomplete follow-up utilized?; Q11 – Was appropriate statistical analysis used?).

Results of the meta-analysis of the effect of ketamine on PTSD-associated symptoms

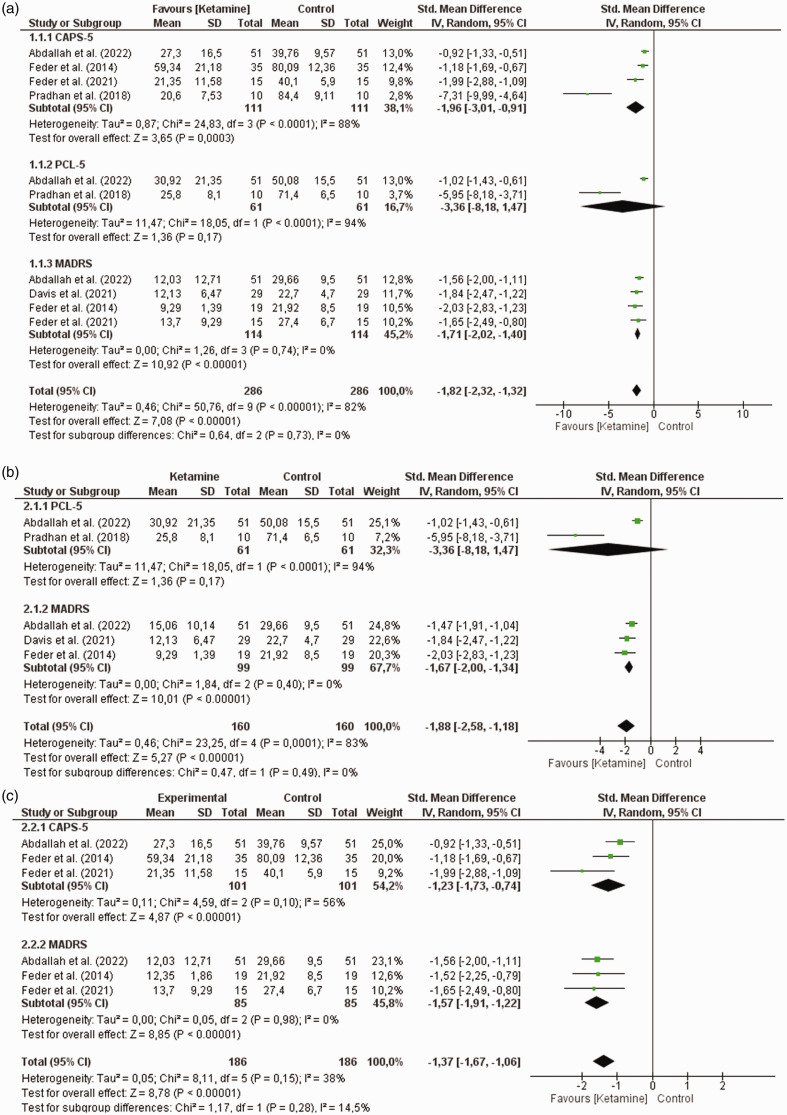

The effect of ketamine on controlling symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is shown in Figure 4. Overall, the results demonstrate a statistically significant difference, with this effect being favorable for ketamine treatment [baseline vs. Best effect after ketamine treatment (ΔM = −1.82, 95% CI = −2.32, −1.32, χ2 = 50.76, I2 = 82%, Z = 7.08, p < 0, 00001, r = 0.42/low effect, Figure 4(a)). Baseline effects vs. Best effect of ketamine in the first 24 hours after treatment (ΔM = −1.88, 95% CI = −2.58, −1.18, χ2 = 23.25, I2 = 83%, Z = 5.2, p < 0.00001, r = 0.42/low effect, Figure 4(b)). Baseline effects vs. Best effect of ketamine after 24 hours of treatment (ΔM = −1.37, 95% CI = −1.67, −1.06, χ2 = 8.11, I2 = 38%, Z = 8.78, p < 0.00001, r = 0.64/mean effect, Figure 4(c)].

Figure 4.

Results of the meta-analysis of the effect of ketamine on symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder assessed by the CAPS-5, PCL-5 and MADRS scales. (a) Baseline effect vs Best effect after ketamine treatment. (b) Baseline effect vs Best effect of ketamine in the first 24 hours after treatment and (c) Baseline effect vs Best effect of ketamine after 24 hours of treatment.

Thus, we used subgroup analyzes to better understand these findings and explore the reasons for heterogeneity. Significant results were found only for symptoms assessed by the CAPS-5 and/or MADRS instruments. Baseline effects vs. Best effect after ketamine treatment [CAPS-5 (ΔM = −1.96, 95% CI = −3.01, −0.91, χ2 = 24.83, I2 = 88%, Z = 3.65, p = 0.0003, r = 0.35/low effect). MADRS (ΔM = −1.71, 95% CI = −2.02, −1.40, χ2 = 1.26, I2 = 0%, Z = 10.92, p < 0.00001, r = 1, 02/height effect), Figure 4(a)], baseline vs. Best effect of ketamine in the first 24 hours after treatment [MADRS (ΔM = −1.67, 95% CI = −2.00, −1.34, χ2 = 1.84, I2 = 0%, Z = 10, 01, p < 0.00001, r = 1.01/high effect), Figure 4(b)] and baseline effects vs. Better effect of ketamine after 24 hours of treatment [CAPS-5 (ΔM = −1.23, 95% CI = −1.73, −.74, χ2 = 4.59, I2 = 56%, Z = 4.87, p < 0.00001, r = 0.48/low effect). MADRS (ΔM = −1.57, 95% CI = −1.91, −1.22, χ2 = 0.05, I2 = 0%, Z = 8.85, p < 0.00001, r = 0, 96/high effect), Figure 4(c)].

These findings show that ketamine is a promising drug in PTSD therapy, despite the high heterogeneity found in some subgroups. Its effect is highlighted in the evaluations performed after 24 h (r = 0.64/mean effect) in the evaluation of symptoms by the MADRS scale [Baseline effects vs Best effect after treatment with ketamine (r = 1.02/high effect). In the first 24 hours after treatment (baseline effects versus the best effect of ketamine with r = 1.01/high effect) and this benefit lasts after 24 hours of treatment (baseline effects versus the best effect of ketamine after 24 hours of treatment (r = 0.96/high effect)].

Discussion

In this new analysis, we show that the case for using ketamine as a promising therapy for PTSD is favorable. However, the preliminary studies available for meta-analysis do not allow us to suggest the dosage and frequency/route of administration but may indicate the need for parameter adjustments to ensure safety and cost-effectiveness during treatment.

In this systematic review, 64.28% of the studies analyzed were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), representing the best study design for testing the effectiveness of clinical interventions. 25 The composition of the sample considered previous exposure to traumatic events, such as natural disasters, catastrophes, serious accidents, terrorist attacks, wars, and many other violent actions. 26 Given that war veterans and victims of violence were frequently exposed to these events, they accounted for a large part of the sample.

The age range of participants clinically diagnosed with PTSD ranged from 18 to 80 years with age predominance of 43.2 years. It is verified that the symptomatologic manifestations of PTSD may have manifested in periods after the traumatic events. However, there should be more evidence for this finding that analyzes the temporal relationship between the traumatic event and the onset of symptoms.

It is observed that 85.5% (n = 12) of the studies were carried out in the USA. This country has more than 200 programs focused on treating individuals with PTSD symptoms spread across every state across the country through the US Department of Veterans Affairs and the national PTSD center, a world leader in PTSD research, education, and treatment. 27 In addition, this country has a high military contingent sent to conflicts around the world, which in part justifies this investment in assistance due to war conflicts.15,27 Because of this context, new research on PTSD is paramount.

The choice of Ketamine administration route is related to bioavailability and adequate infusion time, ensuring better cost-benefit for patients. The intravenous route offers greater availability of the active ingredient in the body when compared to the oral route. 28 For ketamine, a slow infusion over 40 minutes intravenously in 0.9% sodium chloride is recommended. 15

However, studies show that ketamine is administered intravenously (IV) at doses in the range of 0.1 and 0.5 mg/kg. However, in this review, most studies in this area of research established the dose standardization at 0.5 mg/kg. 29 It is important to note that many articles included in the review consider the dose of 0.5 mg/kg as a single dose, constituting the standard of care.2–4,15–17,30–33 The option of administering ketamine through infusion pumps has been pointed out in most studies for providing greater stability of infusion with precision or automated intervals ensuring better bioavailability in the patient's body fluids.

The ketamine has initial rapid absorption and a large volume of distribution, promoting a half-life of up to 3 hours, with a slower elimination by urine after hepatic metabolism. The dose range varies with different applications route; in injectable solutions, the concentration ranges from 10 to 100 mg/mL. The dosing scheme by intravenous route presents dose with 1.5–2 mg/kg over 30–60 sec; however, may administer incremental doses of 0.5–2 mg/kg IV by 5–15 min; to oral route the dose 6–10 mg/kg PO once; mix with 0.2–0.3 mL/kg of a beverage, however, for resistant depression or PTSD symptoms were used infusion with 0.5 mg/kg IV twice weekly. 34 Must recently, the esketamine, the S-enantiomer of ketamine, was demonstrated good results by intranasal administrations, with a therapy scheme for depression symptoms initiated with 56 mg and a maintenance phase for five weeks with a dose range of 56 or 84 mg. For Depressive Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder with Acute Suicidal Ideation or Behavior was incited with 84 mg intranasally two times a week for four weeks.35–37

The most common side effects of ketamine seen in the studies were blurred vision, dizziness, fatigue, headache, nausea or vomiting, dry mouth, poor coordination, restlessness, anxiety, irritability, constipation, nightmare occurrence, and headache. However, the transient dissociative effect is the most common of the side effects. Despite this, study results suggest that single and repeated infusions of ketamine are safe and well-tolerated by patients with chronic PTSD.2,15,38 The assessment of clinical symptoms is more present in studies that use the CAPS-5 and MARS criteria and in only two studies that use the PCL-5 criteria.15,17 Thus, this low number of samples using the PCL-5 evaluative criterion may have negatively influenced the results, as it is not very representative.

The Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) is a score used to measure the severity of symptoms of depression, and the evidence for the beneficial effects of ketamine in treating depression appears to be more robust 39 than its use in improving PTSD symptoms. 15 Although the biological mechanisms are not fully understood, clinical studies have demonstrated that N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor antagonists, such as ketamine, have rapid antidepressant effects in treatment-resistant depression. 40

The lack of blinding in the analysis of the results of the studies classified as a high risk of bias in the item "Q6 - Were the outcome assessors blinded to the treatment assignment?" it can result in the induction of the evaluation of the results by the evaluators being aware of the attributions of the intervention. Consequently, this can lead to an overestimation of the intervention effects, therefore analyzing more subjective results. 24 Thus, the heterogeneity of the data may be associated with the diversity of criteria for assessing the intensity of PTSD used in randomized clinical trials, the concealment of demographic and population characteristics, and the sample size of individuals exposed to interventions that make it difficult to have the necessary robustness to infer the actual effectiveness of the treatment at short, medium and long duration.

Ketamine treatment rapidly decreased the severity of PTSD.2,15,17 However, the significance of this reduction appears to be controversial, due to the fact that some studies have shown statistically significant results,2,3,30,38 while others have not found significant results (Abdallah et al., 2022 b) or did not present such information transparently. 17 In general, the pooled results of this meta-analysis were consistent with those found by Feder et al. (2021) and Feder et al. (2014), who revealed statistically significant differences favorable to PTSD treatment with ketamine when compared to control groups. Therefore, the severity of PSTD in patient populations varies significantly with the choice of scale; however, these clinical trial studies demonstrated that ketamine treatment rapidly decreased PTSD severity across all checklists compared to control groups representing an important alternative for the treatment of PTSD patients.

Outcomes and limitations

This work is one of the first to compile and evaluate quantitative data from intervention studies to measure the effectiveness of ketamine treatment in reducing PTSD symptoms. Due to the fact that this disease is a debilitating disorder with few treatment options, 15 conducting studies that evaluate alternative therapies and medicines is paramount to improve the prospects for combating the disease. This systematic review with meta-analysis allows us to identify points that should be discussed in future studies and to clarify doubts regarding the infusion time, the standard dose used and the age group of the patients in the studies, and the reason for the high number of studies carried out in the USA.

The study had some limitations, such as (1) Different ways of conducting the RCT that made it difficult to extract the data necessary for the analyses; (2) The amount of RCT available for analysis; (3) the presence of observational studies decreases the reliability of inferences about treatment efficacy.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Luis Fernando Reis Macedo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3262-9503

Gyllyandeson de Araújo Delmondes https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9890-9196

Modesto Leite Rolim Neto https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9379-2120

Irwin Rose Alencar de Menezes https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1065-9581

References

- 1.Asim M, Wang B, Hao B, et al. Ketamine for post-traumatic stress disorders and it’s possible therapeutic mechanism. Neurochem Int 2021; 146: 105044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feder A, Costi S, Rutter SB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2021; 178: 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norbury A, Rutter SB, Collins AB, et al. Neuroimaging correlates and predictors of response to repeated-dose intravenous ketamine in PTSD: preliminary evidence. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021; 46: 2266–2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis MT, DellaGiogia N, Maruff P, et al. Acute cognitive effects of single-dose intravenous ketamine in major depressive and posttraumatic stress disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2021; 11: 205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liriano F, Hatten C and Schwartz TL. Ketamine as treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder: a review. Drugs Context 2019; 8: 212305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeftić A, Ikizer G, Tuominen J, et al. Connection between the COVID-19 pandemic, war trauma reminders, perceived stress, loneliness, and PTSD in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Curr Psychol 2021; 1–13. DOI: 10.1007/s12144-021-02407-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Astill Wright L, Sijbrandij M, Sinnerton R, et al. Pharmacological prevention and early treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry 2019; 9: 334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fluyau D, Mitra P, Jain A, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder in substance use disorders: a Bayesian meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2022; 78: 931–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morganstein JC, Wynn GH, West JC. Post-traumatic stress disorder: update on diagnosis and treatment. BJPsych Advances 2021; 27: 184–186. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yabuki Y, Fukunaga K. Clinical therapeutic strategy and neuronal mechanism underlying post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). IJMS 2019; 20: 3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray SL, Holton KF. Post-traumatic stress disorder may set the neurobiological stage for eating disorders: a focus on glutamatergic dysfunction. Appetite 2021; 167: 105599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasmusson AM, Pineles SL, Brown KD, et al. A role for deficits in GABAergic neurosteroids and their metabolites with NMDA receptor antagonist activity in the pathophysiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Neuroendocrinol 2022; 34: e13062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Jumaili W, Trivedi C, Chao T, et al. The safety and efficacy of ketamine NMDA receptor blocker as a therapeutic intervention for PTSD review of a randomized clinical trial. Behavioural Brain Res 2022; 424: 113804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McIntyre RS, Rosenblat JD, Nemeroff CB, et al. Synthesizing the evidence for ketamine and esketamine in treatment-resistant depression: an international expert opinion on the available evidence and implementation. Am J Psychiatry 2021; 178: 383–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdallah CG, Roache JD, Gueorguieva R, et al. Dose-related effects of ketamine for antidepressant-resistant symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans and active duty military: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled multi-center clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022; 47: 1574–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dadabayev AR, Joshi SA, Reda MH, et al. Low dose ketamine infusion for comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic pain: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 2020; 4: 2470547020981670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pradhan B, Mitrev L, Moaddell R, et al. D-serine is a potential biomarker for clinical response in treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder using (R,S)-ketamine infusion and TIMBER psychotherapy: a pilot study. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 2018; 1866: 831–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varker T, Watson L, Gibson K, et al. Efficacy of psychoactive drugs for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of MDMA, ketamine, LSD and psilocybin. J Psychoactive Drugs 2021; 53: 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daly EJ, Turkoz I, Salvadore G, et al. The effect of esketamine in patients with treatment‐resistant depression with and without comorbid anxiety symptoms or disorder. Depress Anxiety 2021; 38: 1120–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mello RP, Echegaray MVF, Jesus-Nunes APet al. Trait dissociation as a predictor of induced dissociation by ketamine or esketamine in treatment-resistant depression: secondary analysis from a randomized controlled. J Psychiatr Res 2021; 138: 576–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2016; 5: 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk ofbias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019; 28: 14898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serdar CC, Cihan M, Yücel D, et al. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem Med (Online) 2021; 31: 27–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Julian PT, Higgins Savović J, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Cochrane, p. Chapter 8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vinkers CH, Lamberink HJ, Tijdink JK, et al. The methodological quality of 176,620 randomized controlled trials published between 1966 and 2018 reveals a positive trend but also an urgent need for improvement. PLoS Biol 2021; 19: e3001162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dar IM, Scholar PDN, Chaudhary P, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Kashmir (India): a review. Int J Creative Res Thoughts 2021; 9: i335–i341. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue C, Shawler E, Jordan CH, et al. Veteran and Military Mental Health Issues. In StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdallah CG, Adams TG, Kelmendi B, et al. Ketamine’s mechanism of action: a path to rapid‐acting antidepressants. Depress Anxiety 2016; 33: 689–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrade C. Ketamine for depression, 4: in what dose, at what rate, by what route, for how long, and at what frequency? J Clin Psychiatry 2017; 78: 10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feder A, Rutter SB, Schiller D, et al. The emergence of ketamine as a novel treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Adv Pharmacol 2020; 89: 261–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartberg J, Garrett-Walcott S, de Gioannis A. Impact of oral ketamine augmentation on hospital admissions in treatment-resistant depression and PTSD: a retrospective study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2018; 235: 393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albott CS, Lee S, Cullen KR, et al. Characterization of Comorbid Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder Using Ketamine as an Experimental Medicine Probe. Journal of Psychiatry and Brain Science 2021; 6: e210012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soleimani L, Dewilde K, Kim JJ, et al. Effects of ketamine on suicidal ideation in patients with mood and anxiety spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014; 39: S386–s387. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abuhelwa AY, Somogyi AA, Loo CK, et al. Population Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of the Therapeutic and Adverse Effects of Ketamine in Patients with Treatment-Refractory Depression. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2022. DOI: 10.1002/cpt.2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matłoka M, Janowska S, Gajos-Draus A, et al. Esketamine inhaled as dry powder: Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and safety assessment in a preclinical study. Pulmon Pharmacol Therapeut 2022; 73–74: 102127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Ruixo C, Rossenu S, Zannikos P, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of esketamine nasal spray and its metabolite noresketamine in healthy subjects and patients with treatment-resistant depression. Clin Pharmacokinet 2021; 60: 501–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jonkman K, Duma A, Olofsen E, et al. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of inhaled esketamine in healthy volunteers. pubs.asahq.org, https://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article-abstract/127/4/675/19823 (accessed 8 June 2022) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Feder A, Parides MK, Murrough JW, et al. Efficacy of intravenous ketamine for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71: 681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moriguchi S, Takamiya A, Noda Y, et al. Glutamatergic neurometabolite levels in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Mol Psychiatry 2019; 24: 952–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amidfar M, Woelfer M, Reus GZ, et al. The role of NMDA receptor in neurobiology and treatment of major depressive disorder: evidence from translational research. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2019; 94: 109668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]