Abstract

Objectives. To examine the effect of the January 2017 leak of the federal government’s intent to broaden the public charge rule (making participation in some public programs a barrier to citizenship) on immigrant mothers and newborns in New York State.

Methods. We used New York State Medicaid data (2014–2019) to measure the effects of the rule leak (January 2017) on Medicaid enrollment, health care utilization, and severe maternal morbidity among women who joined Medicaid during their pregnancies and on the birth weight of their newborns. We repeated our analyses using simulated measures of citizenship status.

Results. We observed an immediate statewide delay in prenatal Medicaid enrollment by immigrant mothers (odds ratio = 1.49). Using predicted citizenship, we observed significantly larger declines in birth weight (−56 grams) among infants of immigrant mothers.

Conclusions. Leak of the public charge rule was associated with a significant delay in prenatal Medicaid enrollment among immigrant women and a significant decrease in birth weight among their newborns. Local public health officials should consider expanding health access and outreach programs to immigrant communities during times of pervasive antiimmigrant sentiment. (Am J Public Health. 2022; 112(12):1747–1756. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.307066)

Since 1882, US immigration law has denied admission to people who are or are likely to become a public charge. The term public charge, however, was undefined until 1999, when regulatory guidance limited the definition to those who were primarily dependent on specific federal benefit programs for their income or requiring long-term institutionalized care.1,2

In 2017, the Trump administration indicated its intent to change the definition of public charge in a way that would constrain low-income immigrants’ use of core public benefit programs essential to health and well-being. In January 2017, a draft executive order from the federal government to broaden the existing rule was leaked and circulated widely. A proposed rule was published in October 2018.3 A final rule was issued in August 2019,4 but its implementation was the subject of several court challenges. The rule ultimately went into effect briefly on February 24, 2020, though full implementation was stayed by the courts and after January 20, 2021, by the Biden administration.5 On September 8, 2022, the Biden administration published a new set of rules that codifies the more generous pre‒Trump era public charge guidance.6

When deemed a public charge, an individual is not eligible for lawful permanent resident (LPR) status, commonly known as holding a “green card,” and will be denied entry or reentry to the United States. The rule does not directly affect other immigrants—those who already have LPR status, are naturalized US citizens, or are the citizen children of immigrants. In this article, we use the term “noncitizen” to refer to those without LPR status and the term “immigrant” to include all foreign-born persons.

The pre-2020 definition deemed immigrants a public charge when the use of cash assistance programs or government-funded institutionalized long-term care represented their primary source of economic support.2 The new rule would have expanded this list of benefits by incorporating several public benefit programs that are widely used by low-income families and individuals to help meet basic needs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, and housing assistance, and would regard any use of these benefits as grounds for deeming an individual a public charge. In addition, the revised rule creates stricter income and wealth tests. The effects could have been substantial, because the use of these additional benefits is so widespread. While over the period 1997 to 2017 fewer than 3% of US-born citizens participated in the programs that comprised the criteria under the long-standing definition, nearly half (43% to 52%) participated in at least one of the programs that would have made them subject to the new public charge criteria had they been immigrants.7,8 The proposed rule changes could have had far-reaching and direct effects on the composition, health, and economic stability of the targeted immigrant families. Because of confusion and fear of deportation or loss of future LPR status, “the chilling effect,” they could have affected eligible immigrants who were not directly targeted by the rule but might nevertheless not enroll or renew public benefits for themselves or their (citizen) children. In addition, immigrants might not seek or might withdraw from public benefits that were not targeted by the rule, such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children or Medicaid among pregnant women and children aged younger than 21 years.

Large-scale chilling effects caused by the new widened definition were reported broadly.9–14 The Urban Institute found that 14.8% of adults in low-income families with children reported avoiding Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program in 2019.15 Research has also shown that potentially 2.1 million essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic failed to enroll in Medicaid, and 1.3 million gave up SNAP because of concerns about the public charge rule.9

IMPORTANCE OF ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE

The impact of the public charge rule may be particularly consequential for the health of low-income pregnant immigrant women, who might delay Medicaid enrollment during pregnancy, which, in turn, could delay and reduce prenatal care utilization.12,16 Lack of proper prenatal care during pregnancy might lead to lower birth weight and an increased likelihood of preterm birth. Health conditions such as maternal depression that go undiagnosed and untreated have been found to also negatively affect children’s health, food security, and developmental outcomes.17,18 Parental insurance coverage is associated with a greater likelihood that insured children have a usual source of health care and receive preventive services.19–21 Studies have also shown that sociopolitical stressors, such as immigration raids and President Trump’s inauguration, themselves significantly increased rates of preterm births and low birth weight.22–24

In the United States, 1 in 4 children live with at least 1 immigrant parent.25 More than 10 million people live in immigrant families that receive 1 of the major public benefits that under newly proposed rules could be considered a “public charge.”8 This includes millions of US-born children with noncitizen parents. New York State (NYS) has one of the nation’s largest immigrant populations; at 4.4 million people they constitute more than 20% of the state’s total population. The contrast between New York City (NYC) and the suburban or rural areas in New York State also provides a unique opportunity to examine the effect of the public charge rule leak in urban versus nonurban areas.

Considering the importance of access to timely prenatal care for low-income immigrant women, the gaps in the literature, and the hostile environment that may be generated by antiimmigration policies and rhetoric, this study aimed to measure changes in Medicaid enrollment of pregnant low-income immigrant women as a result of the 2017–2020 public charge revisions.

METHODS

We used NYS Medicaid claims data for this analysis. The NYS Medicaid claims data include both fee-for-service claims and comprehensive managed care claims, which are of comparable quality.26 The database includes Medicaid recipients’ enrollment status, such as address history, demographic characteristics, and citizenship status, though the citizenship status variable is not available for those who joined Medicaid via the Health and Benefits Exchange Program after 2014. The database also includes detailed information on Medicaid utilization, including date of service, diagnoses, and procedures.

Sample

We selected all infants born in NYS hospitals between September 2014 and December 2019. We then linked the infants to their mothers by using the Medicaid case number, infant’s date of birth, and mother’s hospital discharge date. On average, we identified more than 120 000 infants per year, and 89% were linked to their mothers (Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org). Our main sample was mothers who joined Medicaid during pregnancy (40%–48% of women who were pregnant each year) because NYS offers Medicaid to pregnant women at a relatively higher income threshold of $28 723 for a family of 1 regardless of immigration status.

Timing of the Public Charge Rule Impacts

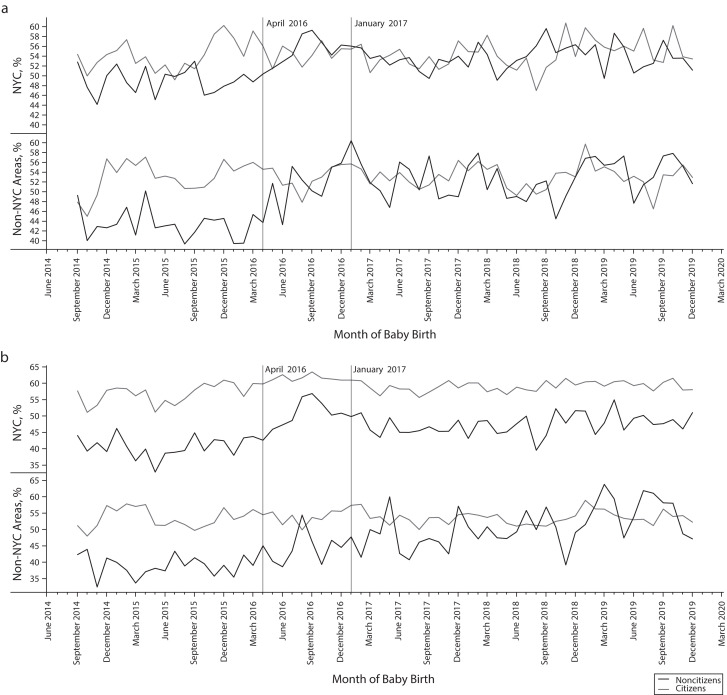

We used January 2017 as the cutoff for the post period because the memo leaked during that time. We excluded pregnancies that had dates of birth between April and December 2016. Although January 2017 was the month of the inauguration and the leak of the memo, Trump announced his candidacy in June 2015 and gained popularity and large-scale media coverage from 2015 to 2016, so chilling effects may have already been triggered in this population before January 2017. We observed some evidence of the pre-2017 chilling effect in our data (Figures 1 and 2). We provided a set of sensitivity analyses including April to December 2016 in Appendix B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of Delayed Enrollment by (a) Reported Citizen Status and (b) Predicted Citizenship Status: New York State, 2014‒2019

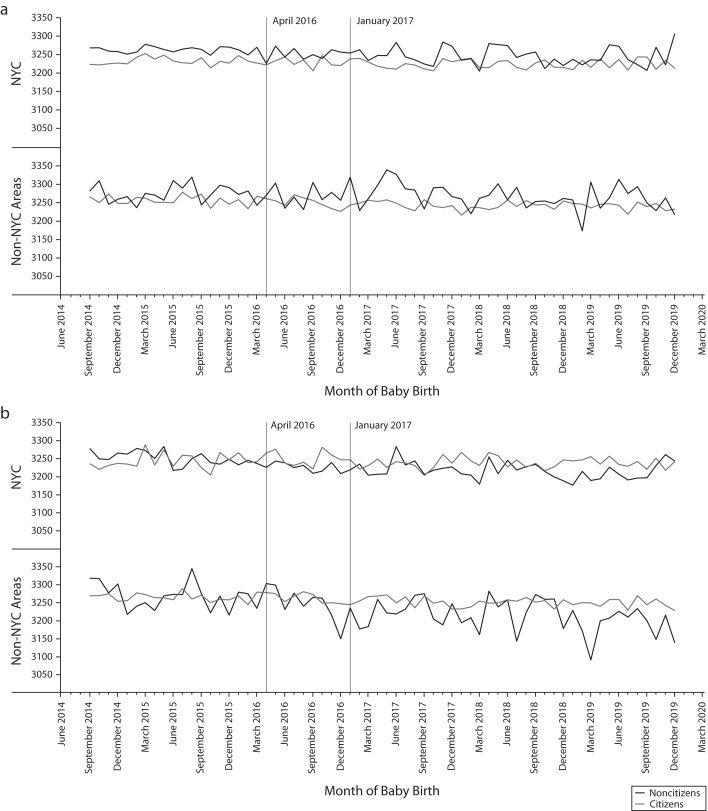

FIGURE 2—

Birth Weight by (a) Reported Citizen Status and (b) Predicted Citizenship Status: New York State, 2014‒2019

Citizenship

We established 2 citizenship measures. For most, but not all, Medicaid beneficiaries, citizenship status is recorded in the enrollment record. The percentage of those without recorded immigration status increased by year, with 2019 the highest at 30%.

We cannot rule out that the missingness is not at random to the exposure of the public charge rule. To address those not reporting statuses, we used a conditional probability method to estimate a continuous measure that represents an individual’s probability of being foreign-born conditioning on that individual’s age (aged 18 years or older vs younger than 18 years), sex (male vs female), race (White, Black, Asian, Hispanic, and other), and census tract in NYS. Studies have used the American Community Survey (ACS) to examine the effect of the public charge rule by citizenship status.11,13,14 We used data from the 2018 ACS Five-Year Estimate to construct a “sex by age by nativity and citizenship status” rate within each race/ethnicity group.

For instance, Person A is 20 years old, female, Hispanic, and living in a given census tract. To predict Person A’s probability of being “foreign born,” we use the estimate of the number of foreign-born people, and 18 years and older, female, and Hispanic living in that census tract as the numerator and the estimate of the total number of people who are 18 years and older, female, and Hispanic living in the given census tract as the denominator.

We verified the estimate using reported citizenship status. The estimate has a stronger predictive value outside NYC. For all reported noncitizens, the average predicted probability of being an immigrant in our model was 0.28 in NYC and 0.24 in the rest of the state; for all reported citizens, the average predicted probability of being an immigrant in our model was 0.15 in NYC and 0.04 in the rest of the state.

We included the predicted probability as a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 1 in all the regression models. In the time-series graphs only, we used a binary variable with 1 indicating a predicted probability between the third quartile and the maximum based on the distribution of known noncitizens (≥ 0.4 for NYC and ≥ 0.39 for the rest of the state) and 0 indicating a predicted probability between the minimum and the first quartile (≤ 0.13 for NYC and ≤ 0.02 for the rest of the state). We included a set of time-series graphs using the median (0.25 for NYC and 0.15 for the rest of the state) as the cutoff in Appendix C (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org).

Outcomes

We evaluated delayed enrollment during pregnancy, prenatal care visits, low birth weight, and severe maternal morbidity (SMM). We used 2 measures of delayed Medicaid enrollment during pregnancy, after the end of the first trimester (≤ 6 months before birth), and after the end of the second trimester (≤ 3 months before birth). We evaluated whether mothers had any prenatal visits. Among those with at least 1 outpatient visit, we evaluated the change in the number of total visits and the days to the first outpatient visit since the imputed pregnancy date (280 days before the infant’s date of birth). Low birth weight is a binary variable with 1 indicating 2500 grams or less. We used the SMM definition provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We included qualifying diagnoses or procedures for SMM-related inpatient visits 1 year after birth.

Statistical Analysis

We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to perform all statistical analyses. We used a comparative interrupted time-series (ITS) model and a difference-in-difference (DID) design to test for the immediate effect of the public charge rule. We then adjusted for the mother’s age, race, county, and infant’s birth month to control for individual, geographical, and seasonal effects (adjusted ITS). Lastly, we evaluated the overall effect of the public charge rule using a traditional DID model, post versus pre and noncitizens versus citizens, adjusting for age, race, county, and infant’s birth month. We used logistic regression for all binary outcomes and linear regression for the continuous outcomes. We included the model statements in Appendix D (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org).

In both sets of models, we used individual-level data. In reported citizenship models, we used citizen women as the reference group; we excluded those in the unknown citizenship group. In the predicted citizenship models, we included individuals with both unknown and known citizenship; we used predicted probability for all individuals.

Sensitivity Analyses

We used 2 additional samples. The second sample included only the oldest child of the family (42%–44% each year) to account for the increased familiarity and comfort level with the Medicaid program (or belief that public charge status was already a given) at subsequent births. The third sample combined mothers who joined Medicaid before pregnancy with those who joined Medicaid during pregnancy (Appendix E, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org).

We also looked at the immediate and overall effects of all the outcomes among Hispanics, Asians, and unknown racial groups (Appendix F, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://ajph.org).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the demographic and outcome distributions by reported citizenship status. Reported noncitizens and citizens were similar in age. Noncitizens were more likely to report Hispanic or Asian race/ethnicity.

TABLE 1—

Means and Percentages of Demographic and Outcome Variables by Reported Citizenship and Geography Among Pregnant Women Enrolled in the New York State Medicaid Program, 2014‒2019

| NYC US Citizens | NYC US Noncitizens | Non-NYC US Citizens | Non-NYC US Noncitizens | |||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| No. | 15 096 | 15 527 | 23 362 | 17 037 | 25 347 | 33 158 | 7 256 | 6 921 |

| Age, y (mean) | 27 | 28 | 30 | 30 | 27 | 28 | 30 | 31 |

| Hispanic, % | 14.19 | 9.46 | 37.66 | 22.92 | 6.30 | 3.49 | 41.45 | 12.94 |

| Non-Hispanic, % | ||||||||

| Asian | 6.12 | 5.97 | 14.81 | 18.31 | 2.51 | 2.60 | 10.17 | 15.51 |

| Black | 28.90 | 29.05 | 18.61 | 15.44 | 18.00 | 18.69 | 10.58 | 13.46 |

| White | 15.44 | 15.54 | 9.36 | 9.77 | 48.53 | 47.46 | 8.53 | 10.70 |

| Other | 6.80 | 6.22 | 5.55 | 6.08 | 4.00 | 4.06 | 5.11 | 7.00 |

| Unknown race | 28.51 | 33.72 | 13.99 | 27.46 | 20.63 | 23.67 | 24.14 | 40.35 |

| Outcome measures | ||||||||

| Medicaid enrollment delays, % | ||||||||

| ≤ 6 mo | 54 | 55 | 49 | 54 | 53 | 53 | 43 | 53 |

| ≤ 3 mo | 21 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 12 | 18 |

| Prenatal visits, any, % | 90 | 91 | 95 | 96 | 91 | 92 | 97 | 96 |

| Among those with any, no. of visits, mean | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 10 |

| Among those with any, no. of days to first visit, mean | 130 | 132 | 133 | 137 | 127 | 131 | 115 | 132 |

| Birth weight, grams | 3 194 | 3 187 | 3 259 | 3 243 | 3 252 | 3 235 | 3 273 | 3 239 |

| Low birth weight, % | 9 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 7 |

| Severe maternal morbidity, % | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

Note. NYC = New York City.

Delayed Enrollment

We observed both immediate and overall effects of the public charge rule on delayed Medicaid enrollment (Table 2). The adjusted ITS model results showed increased delayed enrollment immediately after January 1, 2017, in NYS using both measures of citizenship. In NYS, delayed enrollment (≤ 6 months) increased (odds ratio [OR] = 1.49; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.26, 1.77) comparing noncitizens to citizens in the immediate post‒public charge period.

TABLE 2—

The Immediate and Overall Effects of the Public Charge Rule on Maternal and Child Health Outcomes, Comparing Noncitizens and Predicted Immigrants to Citizens: New York State, 2014‒2019

| Reported Citizenship | Predicted Citizenship | |||||

| NYS, Estimate (95% CI) | NYC, Estimate (95% CI) | Non-NYC, Estimate (95% CI) | NYS, Estimate (95% CI) | NYC, Estimate (95% CI) | Non-NYC, Estimate (95% CI) | |

| Immediate effect: comparative interrupted time series | ||||||

| Medicaid enrollment delays | ||||||

| ≤ 6 mo, OR | 1.49 (1.26, 1.77) | 1.36 (1.09, 1.70) | 1.94 (1.34, 2.82) | 1.89 (1.33, 2.69) | 1.44 (0.88, 2.36) | 2.54 (1.43, 4.51) |

| ≤ 3 mo, OR | 1.16 (0.94, 1.42) | 1.03 (0.79, 1.35) | 1.51 (0.89, 2.55) | 0.96 (0.61, 1.51) | 0.83 (0.45, 1.52) | 2.18 (0.96, 4.95) |

| Prenatal visits, OR | 0.70 (0.49, 1.00) | 0.59 (0.38, 0.90) | 0.58 (0.21, 1.57) | 0.91 (0.40, 2.05) | 0.43 (0.14, 1.32) | 1.16 (0.27, 5.05) |

| No. of visits, b | −0.08 (−0.60, 0.43) | 0.13 (−0.57, 0.82) | −1.47 (−2.55, −0.39) | −0.07 (−1.15, 1.00) | 0.41 (−1.12, 1.94) | −2.13 (−3.80, −0.46) |

| Days to first visit, b | 15.65 (9.80, 21.49) | 11.18 (3.58, 18.79) | 25.57 (12.67, 38.46) | 26.33 (14.24, 38.43) | 14.19 (−2.48, 30.87) | 48.53 (28.73, 68.34) |

| Birth weight, grams, b | 2.93 (−41.61, 47.48) | 25.51 (−32.18, 83.19) | −19.33 (−118.69, 80.03) | −22.09 (−112.80, 68.62) | −57.00 (−181.17, 67.17) | 8.55 (−142.27, 159.38) |

| Low birth weight, OR | 1.25 (0.91, 1.73) | 1.18 (0.79, 1.77) | 1.48 (0.69, 3.16) | 0.99 (0.49, 2.00) | 0.99 (0.38, 2.59) | 1.03 (0.33, 3.19) |

| SMM, OR | 1.21 (0.83, 1.77) | 1.49 (0.95, 2.34) | 1.13 (0.41, 3.07) | 1.10 (0.48, 2.50) | 1.92 (0.68, 5.45) | 0.41 (0.10, 1.77) |

| Overall effect: difference-in-differencea | ||||||

| Medicaid enrollment delays | ||||||

| ≤ 6 mo, OR | 1.16 (1.09, 1.23) | 1.07 (0.99, 1.16) | 1.53 (1.34, 1.75) | 1.43 (1.27, 1.61) | 1.29 (1.09, 1.52) | 1.37 (1.11, 1.68) |

| ≤ 3 mo, OR | 0.89 (0.83, 0.96) | 0.78 (0.71, 0.85) | 1.63 (1.35, 1.96) | 1.28 (1.09, 1.49) | 1.14 (0.93, 1.40) | 1.87 (1.41, 2.49) |

| Prenatal visits, OR | 0.85 (0.75, 0.96) | 0.86 (0.74, 1.00) | 0.58 (0.41, 0.81) | 0.70 (0.53, 0.93) | 0.77 (0.53, 1.13) | 0.79 (0.47, 1.32) |

| No. of visits, b | −0.22 (−0.39, −0.04) | −0.13 (−0.36, 0.11) | −0.57 (−0.97, −0.18) | −0.75 (−1.12, −0.39) | −0.37 (−0.88, 0.14) | −0.94 (−1.55, −0.34) |

| Days to first visit, b | 1.86 (−0.16, 3.87) | −0.70 (−3.30, 1.90) | 18.96 (14.24, 23.68) | 13.84 (9.76, 17.92) | 7.16 (1.62, 12.70) | 26.71 (19.55, 33.88) |

| Birth weight, grams, b | −6.83 (−22.22, 8.56) | −0.17 (−19.94, 19.60) | −37.08 (−73.31, −0.86) | −55.96 (−86.57, −25.35) | −52.10 (−93.45, −10.75) | −91.42 (−145.82, −37.01) |

| Low birth weight, OR | 1.04 (0.93, 1.17) | 1.10 (0.96, 1.26) | 0.99 (0.76, 1.30) | 1.09 (0.86, 1.38) | 1.15 (0.84, 1.58) | 1.20 (0.80, 1.81) |

| SMM, OR | 1.04 (0.91, 1.18) | 0.90 (0.77, 1.05) | 1.65 (1.15, 2.36) | 0.60 (0.45, 0.80) | 0.34 (0.24, 0.49) | 1.31 (0.77, 2.23) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; NYC = New York City; NYS = New York State; OR = odds ratio; SMM = severe maternal morbidity.

We evaluated the overall effect of the public charge rule using a traditional difference-in-difference model—post vs pre and noncitizens vs citizens, adjusting for age, race, county, and infant’s birth month.

The overall effect (DID) in delayed enrollment (≤ 6 months) in NYS had an OR of 1.16 (95% CI = 1.09, 1.23). As the predicted probability of being an immigrant increased from 0 to 1, immediate delayed enrollment (≤ 6 months) increased (OR = 1.89; 95% CI = 1.33, 2.69), while overall the odds of delayed enrollment increased (OR = 1.43; 95% CI = 1.27, 1.61). The large increase is driven by the upstate New York and Long Island (non-NYC) area. In NYC, delayed enrollment (≤ 6 months) comparing noncitizens to citizens in the post‒public charge period was OR = 1.36 (95% CI = 1.09, 1.70) for the immediate delay and OR = 1.07 (95% CI = 0.99, 1.16) for the overall delay, while in non-NYC areas, it was OR = 1.94 (95% CI = 1.34, 2.82) for the immediate delay and OR = 1.53 (95% CI = 1.34, 1.75) for the overall delay.

As the predicted probability of being an immigrant increased from 0 to 1, the OR of immediate delayed enrollment (≤ 6 months) in NYC was positive, but not statistically significant (OR = 1.44; 95% CI = 0.88, 2.36), while overall delayed enrollment increased (OR = 1.29; 95% CI = 1.09, 1.52). We observed significant immediate and overall delays using predicted citizenship (≤ 6 months) in non-NYC areas: immediate OR = 2.54 (95% CI = 1.43, 4.51); overall OR = 1.37 (95% CI = 1.11, 1.68).

We observed a significant overall increase in extremely delayed Medicaid enrollment (≤ 3 months) during pregnancy outside NYC (OR = 1.63; 95% CI = 1.35, 1.96) using reported citizenship and OR = 1.87 (95% CI = 1.41, 2.49) using predicted citizenship.

Prenatal Care Visits

The results showed a significant and overall decrease in the fraction of mothers who had prenatal visits in NYS (OR = 0.85; 95% CI = 0.75, 0.96) using reported citizenship and OR = 0.70 (95% CI = 0.53, 0.93) using predicted citizenship.

Among those with prenatal care visits, we observed decreases in the number of visits and delays to the first visit both immediately and overall. The effect was driven by non-NYC areas: using reported citizenship, mothers immediately had 1.47 (95% CI = −2.55, −0.39) fewer prenatal visits and delayed 25.57 days (95% CI = 12.67, 38.46), and 0.57 (95% CI = −0.97, −0.18) fewer visits and 18.96 (95% CI = 14.24, 23.68) days in the delay overall. Using predicted citizenship, compared with nonimmigrant mothers in non-NYC areas, immigrant mothers had 2.13 (95% CI = −3.80, −0.46) fewer prenatal visits and experienced 48.53 (95% CI = 28.73, 68.34) days in the delay to the first prenatal visit immediately and 0.94 (95% CI = −1.55, −0.34) visits and 26.71 (95% CI = 19.55, 33.88) days overall.

Low Birth Weight

We observed significant overall decreases in birth weight in non-NYC areas: newborns of reported noncitizen mothers weighed 37.08 grams less (95% CI = ‒73.31 grams, −0.86 grams) than those of citizen mothers; newborns of predicted immigrant mothers weighted 91.42 grams less (95% CI = −145.82 grams, −37.01 grams). We did not observe significant changes in the prevalence of low birth weight using the cutoff of 2500 grams or less in the main analyses.

Severe Maternal Morbidity

Compared with reported citizens, the overall odds of SMM for noncitizens increased (OR = 1.65; 95% CI = 1.15, 2.36) in the post period. Using predicted citizenship, we observed significant decreases in SMM in NYC (OR = 0.34; 95% CI = 0.24, 0.49), as well as in NYS as a whole (OR = 0.6; 95% CI = 0.45, 0.8). We did not observe significant immediate effects in SMM using either reported or predicted citizenship.

Sensitivity Analyses

Both the oldest child sample and the all-mothers sample showed significant and immediate delayed enrollment (≤ 6 months) and delays to the first prenatal visit (Appendix E). We observed significant and consistent overall effects of delayed enrollment (≤ 6 months) in the all-mothers sample.

We observed significant effects for both immediate and overall delayed enrollment (≤ 6 months) among Asians using predicted citizenship. We observed positive but not statistically significant results for immediate delayed enrollment among Hispanics using both measures of citizenship (Appendix F). Among those of unknown race, we observed significant statewide overall effects for both measures of delayed enrollment, the number of prenatal visits, days to the first visit, and SMM for outside NYC only (Appendix F).

DISCUSSION

We found that the public charge rule was associated with large and significant damage to the health of immigrant mothers and children in the month of the memo leak, 3 years before it went into effect. In a way, the early timing of our study is evidence of a broader chilling effect beyond the public charge rule—the longer-standing generalized fear among immigrants about seeking public supports given pervasive antiimmigrant sentiment and racial biases that were stoked by the Trump administration.

Among studies and reports that directly examined the effect of the public charge rule on health care, various timing and data sources have been used to define the post‒public charge period. The set of reports from the Urban Institute looked at Internet surveys conducted in December 2018 to 2020.15,27–29 One study used ACS survey data that compared annual Medicaid and SNAP enrollment changes from 2016 to 2019.14 Other studies based on population surveys and provider surveys looked at effects in 2019.11,12 We found that 1 study examined changes from August 2016 to June 2019 using SNAP administrative program data, although the DID effect was estimated as of September 2018.30 Compared with these studies, our study used individual-level administrative data on Medicaid program use and estimated the direct and significant effect at the earliest timing, in January 2017.

We observed a statewide effect in delayed Medicaid enrollment. The magnitude of such delay is substantial. Among all noncitizen mothers who joined Medicaid during pregnancy, 48% joined in the second trimester or later in March 2016, compared with 57% in January 2017. Similarly, among mothers who lived in areas with higher percentages of noncitizens, 42% joined Medicaid in the 2nd trimester or later in March 2016 versus 49% in January 2017. While Medicaid receipt by pregnant immigrant women would not, under the rule, be considered in a public charge determination,31 declines in Medicaid coverage could occur beyond those directly targeted by the rule.

Our outcomes for prenatal care are consistent with reports indicating that immigrant women were afraid to get prenatal care because of fear of the public charge rule.32 The Kaiser Family Foundation found that half of the health centers surveyed reported a decline in health care use by immigrant patients, especially immigrant pregnant women who were not enrolling in or were disenrolling from Medicaid out of fear of the consequences of being deemed a public charge.12

The literature has shown that immigrants can have different experiences of the system within the same state.33 We have seen evidence of this variability in our study. One such variation between NYC and the rest of the state is that NYC has done extensive outreach to the immigrant communities about seeking care and health services, partnering with dozens of community-based organizations and the public hospital system,34 in addition to laws that NYS as a whole has put in place to support immigrants including those who are undocumented.35,36

For all outcome measures, we observed worse outcomes outside NYC areas. This may be, in part, because we were better able to predict citizenship outside NYC. Even using measured citizenship, however, we observed a larger (and statistically significant) reduction in the number of prenatal visits outside NYC. Among those with reported citizenship, the estimated delay in seeking prenatal care was about 18 days for noncitizen mothers, contributing to a significant reduction in the total number of prenatal visits. Together with the significant delay and reduction in prenatal care, the odds of SMM increased significantly; birth weight also decreased significantly, by about 37 grams in the post period. We did not observe significant effects of any of the mentioned results in NYC.

Strengths and Limitations

Some of the strengths of the study included the use of large-scale claims data at the individual level that allowed us to study the universe of low-income pregnant women on Medicaid and measure nuanced enrollment and health outcomes for both individual infants and mothers.

As a limitation, we had many unreported citizenships in the data, which could threaten the validity of the study by introducing selection bias. We addressed the limitation by estimating the effects using predicted citizenship. Because we only looked at NYS, generalizing the results to states with different Medicaid or immigration policies would be another limitation.

Public Health Implications

Our study demonstrated that the rule changes the Trump administration proposed had far-reaching chilling effects on the health of immigrant mothers and their (citizen) infants. We found larger effects in suburban and rural areas, perhaps because advocacy and community resources are less available in such areas. Local public health officials should consider expanding health access and outreach programs to immigrant communities during times of pervasive antiimmigrant sentiment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding for this research from the Russell Sage Foundation.

We thank NYU Health Evaluation and Analytics Lab and the New York State Department of Health for making the Medicaid claims data available.

Note. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the New York State Department of Health. Examples of analysis performed within this article are only examples. They should not be utilized in real-world analytic products.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The institutional review board at New York University has exempted the study (IRB-FY2018-1285).

See also Alberto and Sommers, p. 1732.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perreira KM, Pedroza JM. Policies of exclusion: implications for the health of immigrant. and their children. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):147–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service. 1999. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1999-05-26/pdf/99-13202.pdf

- 3.Fix M, Capps R.2017. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/leaked-draft-possible-trump-executive-order-public-benefits-would-spell-chilling-effects-legal

- 4.US Department of Homeland Security. 2022. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/08/14/2019-17142/inadmissibility-on-public-charge-grounds

- 5.US Citizenship and Immigration Services. 2020. https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/green-card-processes-and-procedures/public-charge/inadmissibility-on-public-charge-grounds-final-rule-litigation

- 6.US Department of Homeland Security. DHS publishes fair and humane public charge rule. 2022. https://www.dhs.gov/news/2022/09/08/dhs-publishes-fair-and-humane-public-charge-rule

- 7.Trisi BD.2022. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/trump-administrations-overbroad-public-charge-definition-could-deny

- 8.Batalova J, Fix M, Greenberg M.2018. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/chilling-effects-expected-public-charge-rule-impact-legal-immigrant-families

- 9.Touw S, McCormack G, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Zallman L. Immigrant essential workers likely avoided Medicaid and SNAP because of a change to the public charge rule. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(7):1090–1098. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raphael JL, Beers LS, Perrin JM, Garg A. Public charge: an expanding challenge to child health care policy. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(1):6–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrero A, Felix Beltran L, Dominguez-Villegas R, Bustamante AV.2021. https://latino.ucla.edu/research/public-charge-ca-children

- 12.Tolbert J, Pham O, Artiga S.2019. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/impact-of-shifting-immigration-policy-on-medicaid-enrollment-and-utilization-of-care-among-health-center-patients

- 13.Chaudry A, Babcock C, Zhu BZ, Glied SA. Immigrant participation in SNAP in a period of immigration policy changes, 2017‒2019. SSRN. Published online May 30, 2021. 10.2139/SSRN.3872764 [DOI]

- 14.Capps R, Fix M, Betalova J.2022. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/anticipated-chilling-effects-public-charge-rule-are-real

- 15.Haley JM, Kenney GM, Bernstein H, Gonzalez D.2020. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/one-five-adults-immigrant-families-children-reported-chilling-effects-public-benefit-receipt-2019

- 16.Norton SA, Kenney GM, Ellwood MR. Medicaid coverage of maternity care for aliens in California. Fam Plann Perspect. 1996;28(3):108–112. doi: 10.2307/2136222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beardslee WR, Gladstone TRG, Wright EJ, Cooper AB. A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):e119–e131. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14(1):1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidoff A, Dubay L, Kenney G, Yemane A. The effect of parents’ insurance coverage on access to care for low-income children. Inquiry. 2003;40(3):254–268. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_40.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gifford EJ, Weech-Maldonado R, Short PF. Low-income children’s preventive services use: implications of parents’ Medicaid status. Health Care Financ Rev. 2005;26(4):81–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guendelman S, Wier M, Angulo V, Oman D. The effects of child-only insurance coverage and family coverage on health care access and use: recent findings among low-income children in California. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(1):125–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novak NL, Geronimus AT, Martinez-Cardoso A. Change in birth outcomes among infants born to Latina mothers after a major immigration raid. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):839–849. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krieger N, Huynh M, Li W, Waterman PD, van Wye G. Severe sociopolitical stressors and preterm births in New York City: 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2017. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018;72(12):1147–1152. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-211077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alberto CK, Pintor JK, Langellier B, Tabb LP, Martínez-Donate AP, Stimpson JP. Association of maternal characteristics with Latino youth health insurance disparities in the United States: a generalized structural equation modeling approach. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1088. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09188-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capps R, Greenberg M, Fix M, Zong J.2018. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/impact-dhs-public-charge-rule-immigration

- 26.Medicaid managed care and integrated delivery systems: technical assistance to states and strengthening federal oversight. 2013.

- 27.Bernstein H, Gonzalez D, Karpman M, Zuckerman S.2019. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/100270/one_in_seven_adults_in_immigrant_families_reported_avoiding_publi_7.pdf

- 28.Bernstein H, Gonzalez D, Karpman M, Zuckerman S.2020. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/amid-confusion-over-public-charge-rule-immigrant-families-continued-avoiding-public-benefits-2019

- 29.Bernstein H, Karpman M, Gonzalez D, Zuckerman S.2021. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/immigrant-families-continued-avoiding-safety-net-during-covid-19-crisis

- 30.Barofsky J, Vargas A, Rodriguez D, Barrows A. Spreading fear: the announcement of the public charge rule reduced enrollment in child safety-net programs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(10):1752–1761. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Citizenship and Immigration Services. 2020. https://www.uscis.gov/news/fact-sheets/public-charge-fact-sheet

- 32.Dickerson C. Undocumented and pregnant: why women are afraid to get prenatal care. New York Times. November 22, 2020https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/22/us/undocumented-immigrants-pregnant-prenatal.html?referringSource=articleShare

- 33.de Trinidad Young ME, Wallace SP. Included, but deportable: a new public health approach to policies that criminalize and integrate immigrants. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(9):1171–1176. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NYC Care. 2022. https://www.nyccare.nyc/community-based-organization

- 35.New York State Department of Labor. 2022. https://dol.ny.gov/immigrant-policies-and-affairs-0

- 36.Stringer SM. Immigrant Rights and Services Manual. City of New York, Office of the Comptroller. 2015https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/immigrant_rights_and_services_manual.pdf