Abstracts

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has created endless social, economic, and political fear in the global human population. Measures employed include frequent washing hands and using alcohol-based hand sanitisers and hand rubs as instant hand hygiene products. Due to the need to mitigate the pandermic, there is an increase in the local production of alcohol-based hand sanitisers, whose quality and efficacy against germs and the virus are questionable. Therefore, the current study investigated the in-vitro antimicrobial efficacy of on-market alcohol-based handwashing sanitizers used to mitigate the Covid-19 global outbreak toward combating enveloped bacteria such as E. Coli, P. aeroginosa, S. aureus, and a fungus C. albicans. The antimicrobial effectiveness of alcohol-based hand sanitizer was performed by the agar well diffusion method, and the analysis of variance (ANOVA) model was used for statistical analysis. Results indicate that alcohol hand-based sanitizers were more effective in inhibiting P. aeroginosa, with a mean zone of inhibition of 12.47 mm, followed by E. coli, a gram-negative bacterium with a mean zone of inhibition of 12.13 mm than both S. aureus and C. albicans as gram-positive bacteria, and fungi respectively had the same inhibition average of 11.40 mm. The overall mean diameter of inhibition was statistically significantly different among the fifteen tested products. Only one brand of alcohol-based hand sanitizers was the most effective in inhibiting microbes. Less effective sanitizers may impair Covid 19 mitigation efforts and put the population at risk instead of protecting it. Indicating the need for all materials used to mitigate Covid 19 pandermic, including alcohol-based hand sanitizers, to be evaluated and monitored to ensure public health safety.

Keywords: Antimicrobial, Alcohol-based hand washing sanitizers, Covid-19, Mitigation strategies, Public health safety

Antimicrobial; Alcohol-Based Hand washing Sanitizers; Covid-19; Mitigation strategies; Public health safety;

1. Introduction

The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has become a major global public health concern. The necessity of hand cleanliness and respiratory protection in preventing the transmission of the virus has been a top priority for mitigating the outbreak [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. All formulations of hand washing sanitizers are therefore required by health regulatory organizations to attained and maintain certain standards [5,7, 8, 9, 10]. Hand sanitization with alcohol is usually believed to reduce or eliminate bacterial/viral load; however, the compliance rates vary. Hand rubs rinses, gels, and foams containing ethanol, isopropanol, or n-propanol are extensively used for disinfection. Their alcoholic action is effective at a concentration range between 85 and 95%. Isopropyl alcohol inhibited more bacterial and fungal species than ethanol over the concentration range of 60%–100% [11, 12]. The viscosity of glycerine as a component of sanitizers lowers the antibacterial properties of isopropyl alcohol, which was seen on smaller inhibition zone widths through in vitro studies, implying that could be attributable to decreased drug transport [13, 14]. The addition of benzalkonium to isopropyl alcohol sanitizers enhances the efficacy; nevertheless, the synergic activity was not superior over the benzalkonium alone [14]. The efficiency of hand sanitizer mostly relies on the concentration of alcohol, formulation, presence of excipients, applied volume, contact time, and microbial contamination load are important factors [15]. The WHO recommends hand washing sanitizer to prevent the spread of infectious microorganisms through hands [16, 17, 18]. Hand sanitization has become among the WHO recommended personal protection measures for the COVID-19 mediated altered lifestyle [19], with the major focus on preventing the spread of SARS-COV-2 coronavirus infection.

Alcohol used in hand sanitization does not stay on the hands for a very long after application, necessitating repeated hand sanitization. The process denatures and coagulates microbial proteins, resulting in cell lysis. Because of the rising demand for hand sanitizer to combat the spread of SARS-CoV-2, some firms have developed formulations that have not been verified or licensed for usage [20]. In addition, alcohol-based hand sanitizers are widely used because they can easily be prepared at affordable prices. To fight this, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), have developed guidelines for the design and manufacture of such products [21], which are adopted by entire countries. Commercial disinfectants or biocides have been researched for efficacy [11], although there is an insufficient study on disinfectants' efficacy against biofilm-forming bacteria in clinical settings. The SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for causing the Covid 19 pandemic is an enveloped virus [22, 23]. The use of enveloped microbes as a model organism is necessary for in vitro to mimic the structure of the virus, and if the alcohol-based hand washing sanitizers managed to cross the membrane and inhibit the activity of these microbes, it would also be possible for the virus, hence justifying its use in the mitigation of Covid 19 global outbreak. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, as a clinical representative isolate, has been found to cause both community-acquired and nosocomial infections, particularly in patients with a history of intravenous (IV) drug use-associated infections, burn wounds, acute leukaemia, cystic fibrosis, organ transplants, and corneal infections. The virus can be deposited on a solid surface, through which touching the contaminated objects or contacting body mists from affected people can transmit the virus. Enveloped viruses like coronavirus and influenza A H1N1 can live for lengthy periods on inert surfaces [24, 25, 26, 27]. Therefore, the current study investigates in-vitro the antimicrobial efficacy of on-market alcohol-based hand washing sanitizers towards combating P. aeroginosa, S. aureus, E. coli and C. albicans and its application in combating Covid-19 global outbreak.

2. Methodology

The current study is an in vitro study conducted at the Department of Microbiology, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania. This study was Ethically cleared by the University of Dodoma Ethical Review Committee. Among the 147 registered bands by the Tanzania Medicines and Medical Devices Authority (TMDA) [28, 29], fifteen diverse brands of alcohol-based hand sanitizers available at Dodoma market were randomly collected out of their popularity and maximum usage, whereby all studied brands used were kept anonymous. However, it included locally, registered and imported formulations which were available in the marked during the course of this study. The main composition of investigated sanitizers is presented in Table 1. The Mueller-Hinton agar was utilized culture media for the agar diffusion method, while the nutrient broth and nutrient agar medium were used for bacterial isolate preservation. Standard microbes of S. aureus (ATCC-25923), E coli (ATCC-25922), P. aeroginosa (ATC-27853C), and C. albicans (ATCC-10231) were used. Culture plates of the respective micro-organisms were preserved on the nutrient agar slants and were stored at 4 °C. The control used was ciprofloxacin for bacterial and Nystatin oral suspension as an antifungal drug. These microbial agents used as control because they are used widely for mitigation of microbial infection and have proven to have broad spectrum efficacy.

Table 1.

Properties of alcohol-based hand sanitizers evaluated.

| Ingredients | |

|---|---|

| Main | Excipients |

| Ethyl Alcohol (Ethanol) | Water Glycerine |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | |

| Aloe Vera | |

| Fragrance | |

| Isopropyl alcohol | Aqua |

| Glycerine | |

| Triethanolamine | |

| Carbomer | |

2.1. Microbiological analysis

2.1.1. Culture of the testing organism

A standard S. aureus (ATCC-25923), E coli (ATCC-25922), P. aeroginosa (ATC-27853C), and C. albicans (ATCC-10231) preserved and archived in 15% glycerol, were revived by culturing it in nutrient and Saborauds dextrose agar [30, 31].

2.2. Phenotypic antimicrobial effectiveness testing from hand sanitizer

The antimicrobial effectiveness of hand sanitizer testing was performed by well diffusion method on Muller Hinton (MH) agar (Oxoid Ltd) [32, 33, 34]. The S. aureus as gram-positive bacteria, E coli and, P. aeroginosa as Gram-negative bacteria and C. albicans as fungi were tested against hand sanitizer collected from different localities in Dodoma city. In order to ensure accuracy and reliability of results, experiments were done in triplicate, while cross contamination was avoided by experimenting different strains at different days. The Quinolone antibiotics Ciprofloxacin (CIP) disk was used as a standard for comparison, similarly as reported by [32, 33, 34, 35, 36]. Bacterial suspensions were adjusted to an opacity equivalent to 0.5 red from McFarland standard densitometer. Then the inoculum was transferred onto well dried Mueller Hinton agar plates. The test organisms were uniformly seeded on the Mueller-Hinton agar surface and exposed to 1mL fresh milk samples. After that, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h (overnight), and the diameter of the zones of inhibition was recorded using a simple ruler, similarly as was reported by [11, 13, 14, 35, 37, 38].

2.3. Statistical investigation

The outcome variable of the study was the diameter of zones of inhibition measured in millimetres using a simpler ruler recorded. The independent variable was brands of alcohol-based hand sanitizers, whereas the microorganism was used as a control variable. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) modal was used for analysis. The statistical package SAS (version 9.4) [39] was used to analyze the data, at 5% level of significance throughout the study, and an independent variable with a p-value less than 0.05 was considered significantly associated with the outcome variable.

3. Results

The application of hand washing sanitizer in a uniformly cultured microbe tends to affect the growth of microbes that will be highly affected. Figure 1 shows selected experimental results showing inhibition zones of sample and standards. Microbes are grown in areas where no sample (alcohol-based sanitizer) or standards applied.

Figure 1.

Selected experiments showing inhibition zones of tested alcohol-based hand sanitizer.

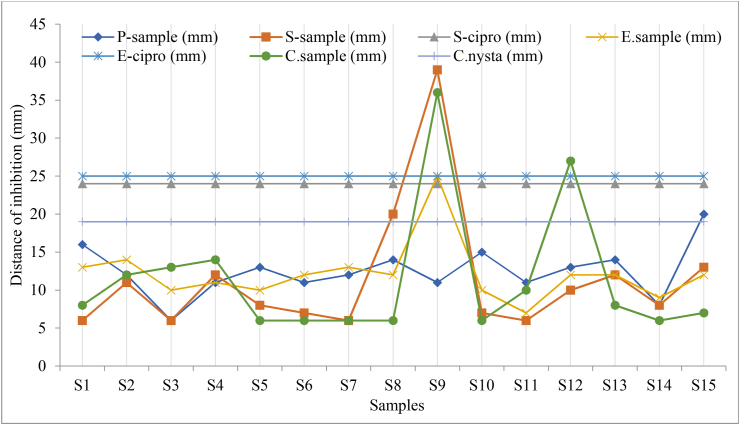

Results of the antimicrobial activity of tested alcohol-based hand sanitizers brands collected at Dodoma city market based on availability are presented in Figure 2. Diameters of the zones of inhibition measured for each sample are presented in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Variations in the zone of inhibition produced by tested alcohol-based hand sanitizer.

Table 2.

Mean distribution of diameter of the zones of inhibition measured in millimetres (mm) using a simpler ruler.

| Hand Sanitizer | N | Mean SE | 95% CI | Min | Max | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 10.75 1.99 | [6.75, 14.75] | 6 | 16 | 43 |

| 2 | 4 | 12.25 0.55 | [11.15, 13.35] | 11 | 14 | 49 |

| 3 | 4 | 8.75 1.49 | [5.78, 11.72 ] | 6 | 13 | 35 |

| 4 | 4 | 12.00 0.62 | [10.76, 13.24] | 11 | 14 | 48 |

| 5 | 4 | 9.25 1.30 | [6.64, 11.86] | 6 | 13 | 37 |

| 6 | 4 | 9.00 1.29 | [6.43, 11.57] | 6 | 12 | 36 |

| 7 | 4 | 9.25 1.65 | [5.95, 12.55] | 6 | 13 | 37 |

| 8 | 4 | 13.00 2.52 | [7.96, 18.04] | 6 | 20 | 52 |

| 9 | 4 | 27.75 5.54 | [16.67, 38.83] | 11 | 39 | 111 |

| 10 | 4 | 9.50 1.76 | [5.97, 13.03] | 6 | 15 | 38 |

| 11 | 4 | 8.50 1.04 | [6.42, 10.58] | 6 | 11 | 34 |

| 12 | 4 | 15.50 3.39 | [8.71, 22.29] | 10 | 27 | 62 |

| 13 | 4 | 11.50 1.09 | [9.30, 13.70] | 8 | 14 | 46 |

| 14 | 4 | 7.75 0.55 | [6.65, 8.85] | 6 | 9 | 31 |

| 15 | 4 | 13.00 2.34 | [8.32, 17.68] | 7 | 20 | 52 |

N – Number of microbes used as modal organisms.

Key: SS1–S15 are samples 1 to 15; P-sample = P. aeroginosa under samples test; S-cipro = S. aurous under ciprofloxacin as control test; S-sample = S. aurous under samples test; E. sample = E. coli under samples test; E-cipro = under ciprofloxacin as control test; C. sample = C. albicans under sample test; C. nysta = C. albicans under Nystatin oral suspension as control test;

Table 3 shows that inhibition of Pseudomonas aeroginosa, a gram-positive bacteria produced 12.47 mm compared to other microorganisms. Both Staphylococcus aurous and Candida albicans as gram-positive bacteria and fungi, respectively, had the same inhibition average of 11.40 mm, while E. coli as gram-negative bacteria experienced a mean of 12.13 mm diameter of inhibition zones.

Table 3.

Mean distribution of diameter of the zones of inhibition measured in millimetres (mm) using a simpler ruler by four (4) types of microorganisms preserved.

| Microorganism | N | Mean SE | 95% CI | Min | Max | Cut-off | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeroginosa | 15 | 12.47 0.83 | [10.81, 14.12] | 6 | 20 | 24 | 167 |

| S. aurous | 15 | 11.40 2.15 | [7.10, 15.70] | 6 | 39 | 24 | 158 |

| E.coli | 15 | 12.13 1.00 | [10.13, 14.14] | 7 | 25 | 25 | 170 |

| C. albicans | 15 | 11.40 2.21 | [6.98, 15.82] | 6 | 36 | 19 | 164 |

Despite the study found the diameter of zones of inhibition for S. aurous being 39 mm and C. albicans being 36 mm as presented in Figure 2 being high, which was produced by sanitizer 9, most of the microorganisms produced a 6 mm diameter of zone of inhibition and their average diameters of zones of inhibition fall within the standard set. Furthermore, the total diameters of inhibition zones were distributed as 167 mm, 158 mm, 170 mm, and 164 mm, corresponding to P. aeroginosa, S. aurous, E. coli, and C. albicans.

4. Discussions

The result of this study indicates that among all investigated hand sanitizers, sanitizer 9 was the most effective compared to the other 14 brands. The order of effectiveness was 9 > 13>10–15 > 2>3 > 14>1 > 11>4–6∼8 > 5–7 > 12 based on mean diameter against ciprofloxacin standard for bacteria and nystatin standard for fungus as indicated in Table 3 and diameter of inhibition in Figure 2. These results indicate that the quality of sanitizers available at the Dodoma city and other regions needs quality evaluation and periodic monitoring. Similar findings were reported in the previous study that evaluated hygienic practices, and among the practices, the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers was reported [6]. The current study further indicates that, the tested sanitizers effectively inhibited P. aeroginosa, a gram-positive bacterium, compared to other microbes. These sanitizers had similar effectiveness towards S. aurous and C. albicans and relatively higher towards E. coli. The diameter of zones of inhibition for S. aurous which was 39 mm and C. albicans which was 36 mm were produced by sanitizer 9, as presented in Table 3. The assessment of zone of inhibition (ZOI) of collected samples in this study is a continuation of a previous study reported by Ripanda et al 2022 [29]. The study involved assessment of effectiveness of traditional hygienic practices including use of 15 brands of on-market alcohol-based hand sanitizers through direct application among 30 volunteers. Among those 15 brands, 33% were registered while the remained 67% included both local and imported brands. A similar study by Ahmed and colleagues tested the antimicrobial activity of common hand sanitizers in hospital and laboratory settings and found that two samples (25%) of the eight hand washes and sanitizers had antimicrobial activity against both S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. In addition two samples (25%) had antimicrobial activity against either S. aureus or P. aeruginosa [40]. Moreover, four samples (50%) had no inhibitory action against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa [40].

The overall F statistic was significant (F (17; 42) = 2.96, p = 0.0022) as presented in Table 3, indicating that the model accounts for a significant portion of the variation in diameter of zones of inhibition among the tested sanitizers. Hence, the effects of alcohol-based hand sanitizers were significant (F = 3.56, p = 0.0007) at the 0.05 level. This indicates that the quality of sanitizer is important for the observed inhibition of respective sanitizers and can be used to address the quality; hence when used for mitigation of Covid pandermic may ensure the safety of public health. Basically, there is a need to evaluate the quality of the materials for mitigation of Covod 19 pandermic and that the ingredients added in the sanitizers influence their effectiveness towards microbes [41]. The findings further revealed that the effects of hand sanitizers were significant (F = 3.56, p = 0.0007) at the 0.05 level. It indicates that quality is key to ensure public safety. Hence mitigation strategies should consider monitoring the quality of these products.

Apart from the need for assessment and monitoring of the antimicrobial efficacy of commonly used alcohol-based hand sanitizers, ensuring safety for users is urgent. With increasing reports of antimicrobial resistance like vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus (S.) aureus (MRSA) that necessitates mitigation strategies. Similarly, microbes may develop resistance towards these disinfection and sanitation products, including alcohol-based hand sanitizers that may impair efforts towards mitigation of current and future pandermic. It should not be overlooked, and future research should consider microbe resistance to sanitation and disinfection products. This study further revealed that the mean value of the diameter of zones of inhibition was significantly different between sanitizer 9 and other brands, as given by the results of Tukey's test for multiple comparisons. Indicating that sanitizer 9 had more effectiveness as given by a significantly higher zone of inhibition (p = 0.0092).

The inclusion of monitoring of biocidal resistance in the WHO action plan and the One Health strategy to tackle antimicrobial resistance species is required and may call attention for further research. This resistance may be due to improper use of disinfectants, which might lead to the destruction of normal flora resulting to least body defence against disease such as corona [42]. Pathogens such as Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter species, and various fungal species have shown medication and biocidal resistance [43, 44, 45, 46], posing a risk of increasing patient mortality and overall deterioration of global ecosystem health. This should be put into consideration during Covid 19 and future pandemics. There is presently a scarcity of information on the effects of biocidal use on environmental habitats and ecosystems. Excessive disinfectant use combined with antimicrobial resistant (AMR) may result in secondary disasters such as loss of soil fertility, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem injury requiring intervention.

5. Conclusions and future outlook

Results of this study indicated the presence of low-quality sanitation products that may impair Covid 19 mitigation strategies. Though this may not reflect the quality status globally, have important consequences regarding infection control and the need to mitigate Covid 19 pandemic globally. It indicates the future need to develop sanitation and disinfection products and procedures that are efficient against all bacteria. The inhibition zone for each sanitizer over the selected microbes is an effective indication of efficacy versus associated risks. Although the spreading pattern of pathogens may vary based on the quality and quantity of used sanitizer, but individual body immunity has a role to play too. These sanitation and disinfection agents are prone to resistance; therefore, strategies for mitigating drug resistance should include sanitation and disinfection products.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Saidi Hamad Vuai: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Asha Ripanda; Hossein Miraji: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Mtabazi Sahini: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Khalfan Sule: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

Ms. ASHA SHABANI RIPANDA was supported by UDOM JAS [JAS 2020].

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Hsieh C.C., Lin C.H., Wang W.Y.C., Pauleen D.J., Chen J.V. The outcome and implications of public precautionary measures in taiwan–declining respiratory disease cases in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(13):1–10. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal A., et al. Clinical & immunological erythematosus patients characteristics in systemic lupus Maryam. J. Dent. Educ. 2012;76(11):1532–1539. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruinen de Bruin Y., et al. Initial impacts of global risk mitigation measures taken during the combatting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Saf. Sci. 2020;128(April) doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Padula W.V., et al. Best-practices for preventing skin injury beneath personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic: a position paper from the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stellefson M., Paige S., Wang M.Q., Chaney B.H. Competency-based recommendations for health education specialists to prevent the spread of COVID-19 among adults with COPD. Am. J. Health Educ. 2021;52(1):18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ripanda A., et al. Evaluation of potentiality of traditional hygienic practices for the mitigation of the 2019–2020 Corona Pandemic. Publ. Health Nurs. 2022;2019(January):1–9. doi: 10.1111/phn.13054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakimi A.A., Armstrong W.B. Hand sanitizer in a pandemic: wrong formulations in the wrong hands. J. Emerg. Med. 2020;59(5):668–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villa C., Russo E. Hydrogels in hand sanitizers. Materials. 2021;14(7) doi: 10.3390/ma14071577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berardi A., et al. Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID- 19 . The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect , the company ’ s public news and information. Int. J. Pharm. 2020;584 January. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomson E.L., Bullied A.R. Production of ethanol-based hand sanitizer in breweries during the COVID-19 crisis. Tech. Q. 2020;57(1):47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Booq R.Y., et al. Formulation and evaluation of alcohol-free hand sanitizer gels to prevent the spread of infections during pandemics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18(12) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luther M.K., Bilida S., Mermel L.A., LaPlante K.L. Ethanol and isopropyl alcohol exposure increases biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2015;4(2):219–226. doi: 10.1007/s40121-015-0065-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanhed P., et al. In vitro antifungal efficacy of copper nanoparticles against selected crop pathogenic fungi. Mater. Lett. 2014;115:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapadia S.P., Pudakalkatti P.S., Shivanaikar S. Detection of antimicrobial activity of banana peel (Musa paradisiaca L.) on Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans: an in vitro study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2015;6(4):496–499. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.169864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berardi A., et al. Hand sanitisers amid CoViD-19: a critical review of alcohol-based products on the market and formulation approaches to respond to increasing demand. Int. J. Pharm. 2020;584 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Organisation W.H. “on hand hygiene in health care first global patient safety challenge clean care is safer care,” World heal. Organ. 2017;30(1):64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Practice B.B. Coronavirus disease 2019. World Heal. Organ. 2020;2019(April):2633. [Google Scholar]

- 18.“Infection prevention and control measures for acute respiratory infections in healthcare settings_ an update.” ISSN 1020-3397. [PubMed]

- 19.WHO . 2020. COVID - 19 Strategy up Date. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ngumba J. “Evaluation of potentiality of traditional hygienic practices for the mitigation of the 2019 – 2020 corona pandemic Hossein Miraji BSc , MSc , PhD 1,”. Publ. Health Nurs. 2022;2019(1–9) doi: 10.1111/phn.13054. August 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.USP NF . 2020. Compounding Alcohol-Based Hand Sanitizer during COVID-19 Pandemic Background and Introduction; pp. 2019–2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortiz-Prado E., et al. Clinical, molecular, and epidemiological characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), a comprehensive literature review. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020;98(1) doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.115094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittal A., Manjunath K., Ranjan R.K., Kaushik S., Kumar S., Verma V. COVID-19 pandemic: insights into structure, function, and hACE2 receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(8):e1008762. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parhar H.S., et al. Topical preparations to reduce SARS-CoV-2 aerosolization in head and neck mucosal surgery. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1268–1272. doi: 10.1002/hed.26200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Accolti M., Soffritti I., Bonfante F., Ricciardi W., Mazzacane S., Caselli E. Potential of an eco-sustainable probiotic-cleaning formulation in reducing infectivity of enveloped viruses. Viruses. 2021;13(11):1–15. doi: 10.3390/v13112227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris D.H., et al. Mechanistic theory predicts the effects of temperature and humidity on inactivation of sars-cov-2 and other enveloped viruses. Elife. 2021;10:1–59. doi: 10.7554/eLife.65902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montse M. “Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID- 19 . The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect , the company ’ s public news and information,” no. January. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 28.TMDA “List of registered hand sanitizers,”. Dar es Salaam. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 29.M G.S., Asha Ripanda S.H.V., Miraji Hossein, Sule Khalfani, Nguruwe Salvatory, Ngumba Julias. Evaluation of potentiality of traditional hygienic practices for the mitigation of the 2019 – 2020 Corona Pandemic,”. Publ. Health Nurs. 2022:1–9. doi: 10.1111/phn.13054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandal S., Van Treuren W., White R.A., Eggesbø M., Knight R., Peddada S.D. Analysis of composition of microbiomes: a novel method for studying microbial composition. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015;26 doi: 10.3402/mehd.v26.27663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta N., Ferreira J., Hong C.H.L., Tan K.S. Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 and ATCC PTA 5289 ameliorates chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73292-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nawa M., et al. Bacteriological profile and antimicrobial efficacy of alcohol-based hand rubs among health care workers and family caregivers at the children’s university teaching hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. Sci. African. 2021;12 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ike B., et al. Prevalence, antibiogram and molecular characterization of comunity-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in AWKA, anambra Nigeria. Open Microbiol. J. 2017;10(1):211–221. doi: 10.2174/1874285801610010211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ali M.N., et al. Evaluation of laboratory formulated hand sanitizing gel in riyadh municipality central area labs. Saudi J. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2020;6(8):548–558. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barberis C.M., et al. Comparison between disk diffusion and agar dilution methods to determine in vitro susceptibility of Corynebacterium spp. clinical isolates and update of their susceptibility. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018;14(May):246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurnia R.S., Indrawati A., Ika Mayasari N.L.P., Priadi A. Molecular detection of genes encoding resistance to tetracycline and determination of plasmid-mediated resistance to quinolones in avian pathogenic Escherichia coli in sukabumi, Indonesia. Vet. World. 2018;11(11):1581–1586. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2018.1581-1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohammadi F., Yousefi M., Ghahremanzadeh R. Green synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using leaves and stems extract of some plants. Adv. J. Chem. A. 2019;2(4):266–275. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shintre M.S., Gaonkar T.A., Modak S.M. Efficacy of an alcohol-based healthcare hand rub containing synergistic combination of farnesol and benzethonium chloride. Int. J. Hyg Environ. Health. 2006;209(5):477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.SAS Institute Inc “SAS version 9.4,” cary. NC. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed K., et al. Analysis of anti-microbial and anti-biofilm activity of hand washes and sanitizers against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. J. Pakistan Med. Assoc. 2020;70(1):100–104. doi: 10.5455/JPMA.2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montagna M.T., et al. Study on the in vitro activity of five disinfectants against Nosocomial bacteria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16(11) doi: 10.3390/ijerph16111895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chandanapalli Sai Himabindu C.S.H., Bitra Tanish B.T., priya Damodara Padma priya D.P., Nimmala Prema Kumari N.P.K., Shaik Nayab S.N. Hand sanitizers: is over usage harmful? World J. Curr. Med. Pharm. Res. 2020:296–300. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meade E., Slattery M.A., Garvey M. Biocidal resistance in clinically relevant microbial species: a major public health risk. Pathogens. 2021;10(5):1–14. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10050598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santaniello A., Sansone M., Fioretti A., Menna L.F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the occurrence of eskape bacteria group in dogs, and the related zoonotic risk in animal-assisted therapy, and in animal-assisted activity in the health context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(9) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Oliveira D.M.P., et al. Antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020;33(3):1–49. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00181-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buxser S. Has resistance to chlorhexidine increased among clinically-relevant bacteria? A systematic review of time course and subpopulation data. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):1–26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256336. August. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.