Abstract

Background and Aims

The North China Plain, the highest winter-wheat-producing region of China, is seriously threatened by drought. Traditional irrigation wastes a significant amount of water during the sowing season. Therefore, it is necessary to study the drought resistance of wheat during germination to maintain agricultural ecological security. From several main cultivars in the North China Plain, we screened the drought-resistant cultivar JM47 and drought-sensitive cultivar AK58 during germination using the polyethylene glycol (PEG) drought simulation method. An integrated analysis of the transcriptome and metabolomics was performed to understand the regulatory networks related to drought resistance in wheat germination and verify key regulatory genes.

Methods

Transcriptional and metabolic changes were investigated using statistical analyses and gene–metabolite correlation networks. Transcript and metabolite profiles were obtained through high-throughput RNA-sequencing data analysis and ultra-performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry, respectively.

Key Results

A total of 8083 and 2911 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and 173 and 148 differential metabolites were identified in AK58 and JM47, respectively, under drought stress. According to the integrated analysis results, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling was prominently enriched in JM47. A decrease in α-linolenic acid content was consistent with the performance of DEGs involved in jasmonic acid biosynthesis in the two cultivars under drought stress. Abscisic acid (ABA) content decreased more in JM47 than in AK58, and linoleic acid content decreased in AK58 but increased in JM47. α-Tocotrienol was upregulated and strongly correlated with α-linolenic acid metabolism.

Conclusions

The DEGs that participated in the mTOR and α-linolenic acid metabolism pathways were considered candidate DEGs related to drought resistance and the key metabolites α-tocotrienol, linoleic acid and l-leucine, which could trigger a comprehensive and systemic effect on drought resistance during germination by activating mTOR–ABA signalling and the interaction of various hormones.

Keywords: Abscisic acid, drought resistance, germination, metabolomics, mTOR signalling, linoleic acid, α-linolenic acid, RNA-seq, wheat

INTRODUCTION

With the decrease in global water resources, drought-induced losses in crop yield are increasing annually (Gupta et al., 2020). The North China Plain is the highest winter-wheat- (Triticum aestivum L.) producing region of China. It is also an area that experiences water shortages. As the main abiotic stress, drought stress is one of the major factors limiting wheat production, and a drought-induced poor germination rate results in a serious yield reduction. Irrigation is usually applied to the soil before or after seeding to improve the germination rate, becoming part of this region’s irrigation scheme for winter wheat. However, low water use efficiency leads to a waste of water resources; therefore, improving drought resistance during germination is vital to wheat production. The efficiency of seed germination and seedling emergence is crucial to crop yield. It is regulated by environmental factors, such as temperature, light or oxygen, and endogenous factors, such as dormancy (Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger, 2006; Izydorczyk et al., 2018). Increasing evidence suggests that it is feasible to regulate the germination ability of crop seeds using biotechnology (Chono et al., 2013; Luo et al., 2021). Thus, drought-resistant seeds can adapt to low soil moisture during germination, which is of great significance for alleviating water shortages and maintaining the ecological security of the region.

Plant hormones and signal transduction processes are essential in drought resistance during germination (Miransari and Smith, 2014). One of the main effects of drought is the accumulation of the phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) (Zhu, 2011, 2016). Endogenous ABA is critical in inducing osmolyte biosynthesis through various signalling cascades (Urano et al., 2009). As a signal transduction process, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is crucial in regulating energy homeostasis to resist stress. The target of rapamycin (TOR) is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine protein kinase that regulates hormone and environmental signals in plants (Fu et al., 2020). Research has shown that TOR functions as a key regulator in response to diverse abiotic stresses (Fu et al., 2020) and positively regulates plant responses to drought and osmotic stress. In arabidopsis, the TOR transgenic line has a longer primary root than the wild type under salt stress (Deprost et al., 2007). Ectopic expression of the arabidopsis TOR gene in rice improves water use efficiency and yield under drought stress (Bakshi et al., 2017). Overexpression of TOR also results in resistance to exogenous ABA during seed germination (Bakshi et al., 2017, 2019). These results indicated that the expression of the TOR gene might mitigate the effects of drought to enhance plant growth. The hormone levels of raptor1b (regulatory-associated protein of TOR B) mutant seeds showed noticeable changes, including increases in ABA, auxin and jasmonic acid, which are known to inhibit germination (Salem et al., 2017). The ABA content of raptorb mutant seeds was increased (Salem et al., 2017), which indicates that TOR is a crucial regulator of seed germination. Many metabolites that respond to drought stress function as vital regulators and have drawn increasing attention recently. Drought-resistant metabolites result from interactions among many genes and pathways and contribute to stress resistance (Garg et al., 2002; Taji et al., 2002; Nuccio et al., 2015). Acetate has been reported to be associated with drought tolerance (Kim et al., 2017). PDC1 and ALDH2B7 are genes for key enzymes in the acetate biosynthesis pathway, and PDC1 and ALDH2B7 double overexpression plants exhibited enhanced drought tolerance (Kim et al., 2017). Seed germination is a complex physiological process regulated by various developmental and environmental cues. However, the mechanisms of drought resistance during germination in wheat, especially the regulatory network, including signal transduction and metabolites, remain largely unknown.

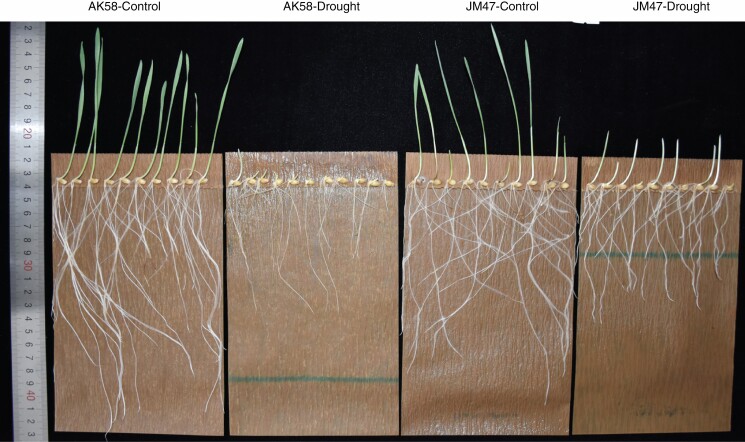

The JM47 cultivar shows strong drought resistance at both the physiological and molecular levels (Wang et al., 2019). Although AK58 is also a drought-resistant cultivar, it was hypersensitive to drought during seed germination, based on our experimental results (Fig. 1). As drought-resistant and drought-sensitive cultivars from the North China Plain, JM47 and AK58 were screened during germination using the polyethylene glycol (PEG) drought simulation method. In this study, we applied an integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics approach to explore drought resistance during seed germination in wheat. We conducted a hydroponic experiment to simulate the seed germination process under drought stress and analyse the drought resistance network during germination. Based on previous results, this experimental model was appropriate for this study because the available transcriptome and metabolomics datasets used here were comparable and the studied phenotypes clearly showed drought resistance during germination. We provide a mass of analysed data to provide new prospects for drought resistance during germination. This study aims to minimize the waste of water resources and improve water use efficiency. We also provide novel insights into improving the agro-ecological environment.

Fig. 1.

Whole view of seed germination under drought treatment at 7 DAI in the two studied cultivars.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design and sampling

Drought-resistant phenotypes of several main wheat cultivars in the North China Plain were identified using the PEG drought simulation method. The screen showed two cultivars with significant differences in drought resistance during germination: the drought-resistant JM47 and drought-sensitive AK58 cultivars. These two wheat cultivars, which were generated by the Henan Institute of Science and Technology through breeding Zhoumai11//Wenmai6/Zhengzhou8960 and by the Shanxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences through breeding 12057/Han522/K37-20, respectively, were used in this study. A hydroponic experiment was carried out using seed germination pouches to induce seed germination for 7 d in a greenhouse under controlled environmental conditions: approx. 16/8 h light/dark regime, 24/18 °C temperature, approx. 500 μmol m–2 s–1 photon flux density and 65 % relative humidity. Four treatments (drought conditions with AK58 and JM47 and control conditions with AK58 and JM47) were performed in this study. The control used 30 mL of deionized water, while drought stress was simulated using 30 mL of 15 % PEG-6000 solution. Three biological replicates were performed, with each replicate containing ten seeds in a germination pouch. Seeds were sterilized in 1 % sodium hypochlorite solution for 30 min, washed six times with distilled water and soaked in water and 15 % PEG-6000 solution for 9 days after imbibition (DAI).

Physiological and morphological traits were measured at 7 DAI using three biological replicates of each sample. Three and eight biological replicates of root samples were collected for transcript and metabolite identification at 7 DAI, respectively. Each biological replicate consisted of ten plants. Root samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen until used in further experiments.

Measurements of physiological and morphological traits

Methods for determination of physiological and morphological traits, including germination rate, maximum root length, maximum shoot length, root to shoot ratio, total root length, total root surface area, total root volume and root activity, are provided in Supplementary data Method S1.

RNA-seq and differential expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the roots at 7 DAI using TRIzol® Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Procedures used for library preparation and transcriptome sequencing analysis are provided in Supplementary data Method S2. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were investigated under both drought-stressed and well-watered conditions at 7 DAI for AK58 and JM47. DEGs were identified via a false discovery rate (FDR) of < 0.05 and |log2(CT_mean_fpkm/CK_mean_fpkm)| ≥ 1. To further obtain the functions of these unigenes, BLASTX (e-value < 0.00001) was employed to search the public databases, including NCBI non-redundant (Nr), Swiss-Prot, KEGG and STRING. The DEGs were subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) (http://geneontology.org/) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) enrichment analyses to determine their biological functions and metabolic pathways at a Bonferroni-corrected P-value < 0.05 compared with the whole-transcriptome background.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

qRT-PCR analysis was performed with a Thermal Cycler CFX96 Real-Time System (BIO-RAD, USA) using the GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega, USA). qRT-PCR was performed under the following conditions: 95 °C for 2 min and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60° C for 30 s and 72° C for 30 s. Each experiment was performed with three biological replicates. β-Actin was used as a reference. Fold changes were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The DNA primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Supplementary data Table S1.

Metabolite extraction and analysis

The procedures for metabolite extraction and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis are provided in Supplementary data Method S3.

Integrative analysis of the transcriptome and metabolomics

KEGG enrichment analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test to identify biological processes most relevant to biological phenomena. After P-value correction (P_bonferroni, ≤0.05), the KEGG pathways for differential metabolites and DEGs were significantly enriched. Metabolites were filtered for correlation analysis via variable importance in the project (VIP) > 1, P < 0.05. Pearson correlation coefficients and P-values were calculated for the transcriptome and metabolomics data integration using Spearman’s method. Correlations corresponding to a coefficient of |R| >0.9 were selected.

Measurement of ABA content

The ABA content in fresh root and shoot samples (0.5 g) harvested at 7 DAI was determined using an ELISA (enzyme-linked immunoassay) kit as described by Zhao et al. (2006). Three biological replicates were used for each experiment. The ELISA data were calculated as described in Weiler et al. (1981).

RESULTS

Drought resistance in seed germination and related physiological traits identified for AK58 and JM47

We observed a significant difference in germinated seeds between the two cultivars at 7 DAI during the drought treatment (Fig. 1); JM47 germinated much better than AK58, which barely germinated.

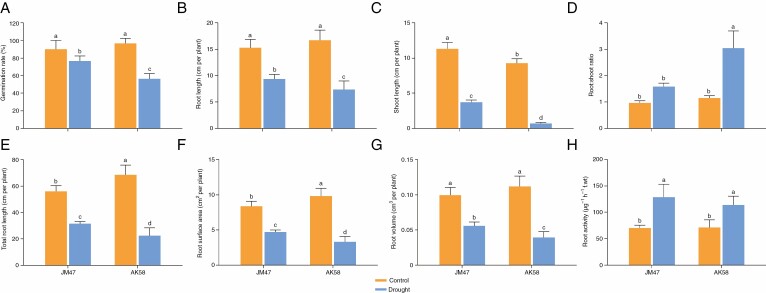

Specific traits were measured in germinated seeds to further verify the physiological changes. Under drought stress, the germination rate was significantly lower in AK58 than in JM47 (Fig. 2A). Certain physiological traits, including the maximum root length, shoot length, total root length, root surface area and root volume (Fig. 2B, C, E–G), exhibited the same trend as the germination rate. The root to shoot ratio exhibited a different trend (Fig. 2D). However, root activity was higher in JM47 than in AK58 plants (Fig. 2H).

Fig. 2.

Morphological changes of seed germination under drought treatment at 7 DAI in the two cultivars. (A) Germination rate, (B) root length, (C) shoot length, (D) root:shoot ratio, (E) total root length, (F) root surface area, (G) root volume and (H) root activity. Different letters indicate a significant difference among treatments at the 0.05 significance level based on Duncan’s multiple range tests. Bars represent the mean ± s.d. (n = 3).

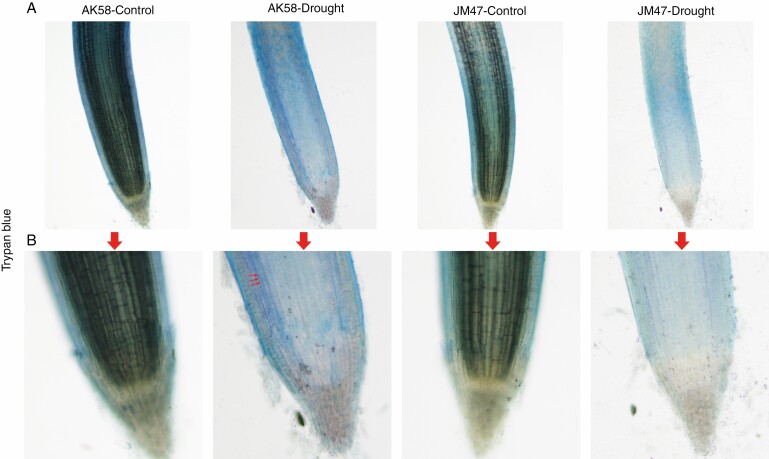

Cell death was observed in the roots using trypan blue staining. Based on microscopic observations of the root tip, there were no significant differences in the number of dead cells between the two cultivars under well-watered conditions (Fig. 3A, B). However, under drought stress, the number of dead cells accounted for a large proportion in AK58 but only a small proportion in JM47 (Fig. 3A, B), indicating that JM47 had a stronger drought resistance capacity.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the root during germination under drought treatment by trypan blue staining in the two cultivars under a microscope at (A) ×4 and (B) ×10 magnification. Dead cells are indicated by red arrows.

Identification of DEGs in JM47 and AK58

To identify the DEGs involved in regulating drought resistance during the germination stage in wheat, RNA-seq was performed. In total, 1.2 billion clean reads were obtained from the tested samples. On average, nearly 0.1 billion reads for each sample were uniquely mapped to the reference genome. More than 90 % of reads were at the Q30 level (an error probability of 0.01 %), and the mapping rate of each sample is shown in Supplementary data Table S2.

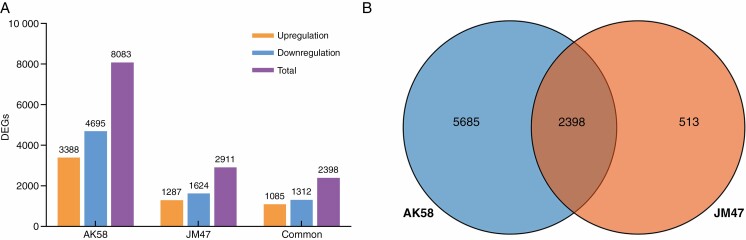

Interestingly, the number of DEGs in AK58 was greater than that in JM47 under drought treatment at 7 DAI (Fig. 4A, B; Supplementary data Table S3).

Fig. 4.

Summary of RNA sequencing data. (A) Histogram of the number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) under drought treatment at 7 DAI in the two cultivars. (B) Venn diagram showing the number of DEGs under drought treatment and the number of shared DEGs in the two cultivars.

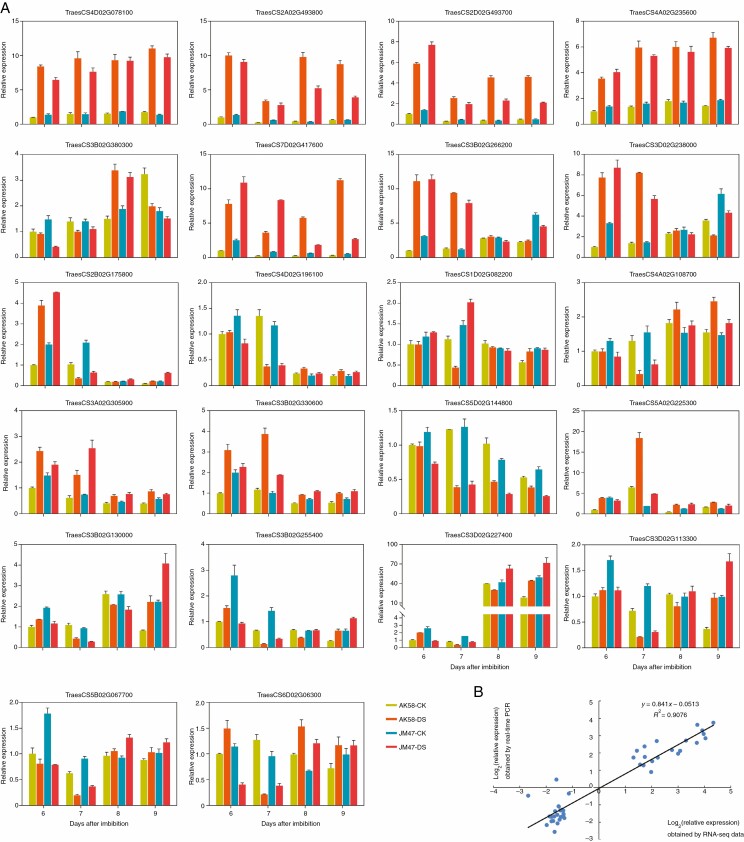

qRT-PCR assays were performed on 22 DEGs to validate the RNA-seq data (Supplementary data Table S1), and the results were compared with those obtained from RNA-seq analysis. As shown in Fig. 5, the qRT-PCR results were highly consistent with those of the RNA-seq analysis, which validated the reliability of the RNA-seq data.

Fig. 5.

Validation of RNA-seq results by qRT-PCR. Expression levels of 22 genes used in this study were detected by qRT-PCR. (A) Transcript levels of 22 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) at 6, 7, 8 and 9 DAI. The bars represent the s.d. (n = 3). (B) Comparison between the relative expression obtained from RNA-seq data and qRT-PCR at 7 DAI. The RNA-seq log2 value of the relative expression (y-axis) has been plotted against the developmental stages of qRT-PCR (x-axis). Primers are listed in Supplementary data Table S1. The corresponding expression data of RNA-seq are listed in Supplementary data Tables S6, S8 and S13.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis

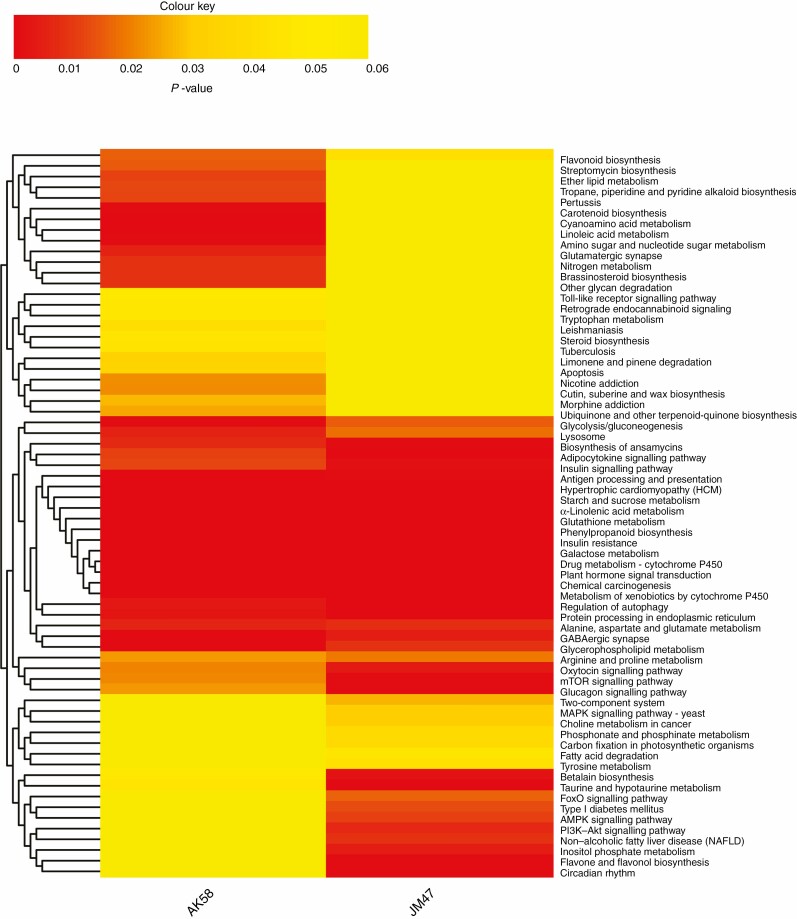

Most of the DEGs were cultivar specific (Fig. 4B). The enriched GO terms also showed apparent cultivar-specific results, suggesting that different molecular mechanisms were activated in the two cultivars (Supplementary data Table S4). For example, ‘coniferin beta-glucosidase activity’ and ‘linoleate 9S-lipoxygenase activity’ were evidently and only enriched in AK58, whereas transporter activity-related GO terms (arsenate ion transmembrane transporter activity and malate transmembrane transporter activity) were strikingly and uniquely enriched in JM47 (Supplementary data Table S4). Similar to the GO terms, the enriched KEGG pathways exhibited cultivar-specific results (Fig. 6). Specifically, the pigment, hormone and amino acid metabolism pathways (e.g. carotenoid biosynthesis, brassinosteroid biosynthesis, linoleic acid metabolism, glutamatergic synapse and nitrogen metabolism) were enriched in AK58. However, pathways strikingly enriched in JM47 were relevant to defence/immunity, energy metabolism and signal transduction [e.g. flavone and flavonol biosynthesis, carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms, phosphate and phosphinate metabolism, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)–Akt signalling pathway, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signalling pathway, circadian rhythm and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathway – yeast] under drought stress (Fig. 6). Furthermore, some KEGG pathways were enriched in AK58 and JM47 (e.g. plant hormone signal transduction, α-linolenic acid metabolism). However, the mTOR signalling pathway was more enriched in JM47 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Hierarchical clustering of enriched KEGG pathways based on P-values under drought treatment at 7 DAI for AK58 and JM47. P-values <0.05 denote that the pathway is significantly enriched. Red represents significantly enriched pathways and yellow the non-significantly enriched pathways.

Regulation of plant hormone- and signal transduction-related DEGs

A total of 359 and 129 genes encoding protein kinases were identified in AK58 and JM47 plants under drought stress, respectively (Supplementary data Table S5). However, genes encoding receptor-like protein kinases (RLKs) accounted for the largest proportion of these genes among AK58 and JM47, at 242 (67 %) and 80 (62 %), respectively (Supplementary data Table S5). Furthermore, most genes encoding serine/threonine RLKs were downregulated in AK58 and JM47. Interestingly, the AMPK signalling pathway, PI3K–AKT signalling and circadian rhythm were only enriched in JM47, whereas enrichment of the mTOR signalling pathway was evident in both cultivars. A total of 14 genes collectively involved in the AMPK, PI3K–AKT, circadian rhythm and mTOR signalling pathways, were enriched in JM47, accounting for a large portion of DEGs at 73.7, 82.4, 93.3 and 100 %, respectively (Supplementary data Table S6).

As secondary messengers, calcium ions are crucial in various signalling pathways. Most DEGs enriched in the calcium ion signalling pathway were downregulated in AK58 and/or JM47 under drought stress (Supplementary data Table S7).

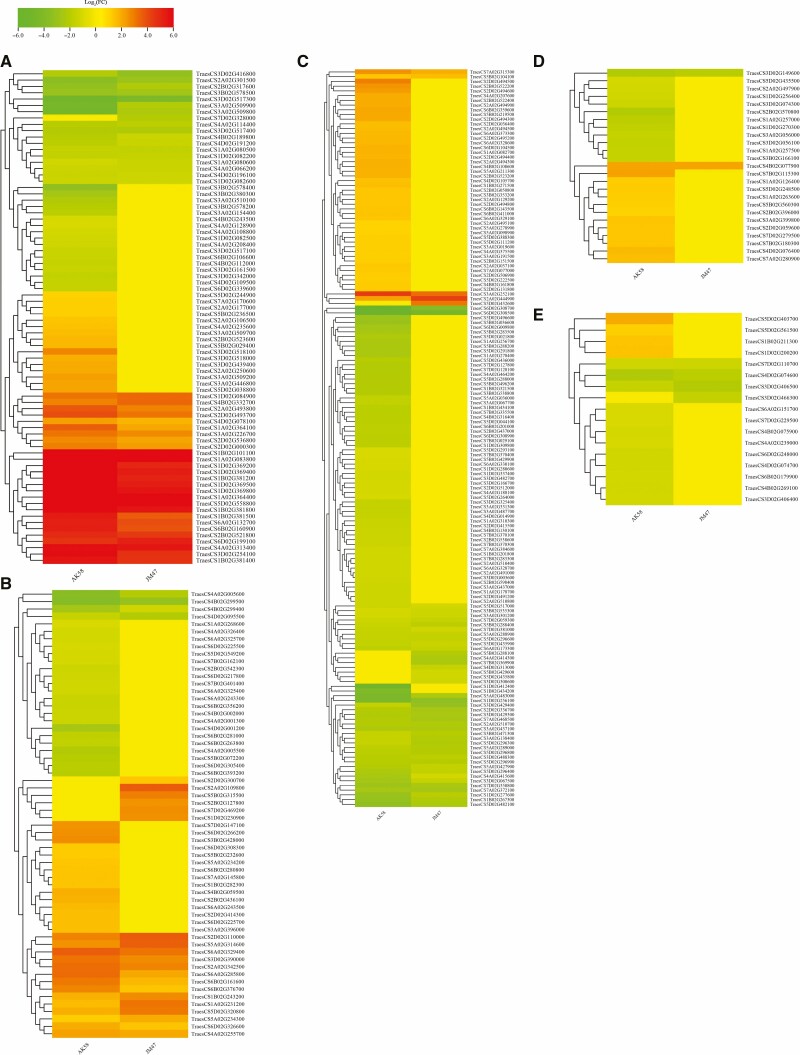

Furthermore, DEGs involved in hormone biosynthesis were verified, and their expression was substantially altered under drought treatment. The number of hormone-related DEGs was greater in AK58 than in JM47. According to KEGG analysis of the DEGs, carotenoid biosynthesis (ko00906) related to ABA metabolism was significantly and uniquely enriched in AK58; however, the DEGs involved in ABA biosynthesis in AK58 showed no significant change in JM47 (Fig. 7A; Supplementary data Table S8). Four genes (TraesCS5D02G038800, TraesCS5B02G029400, TraesCS5B02G029400 and TraesCS2A02G250600) predicted to encode 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED) were upregulated under drought treatment in AK58. Moreover, two genes (TraesCS5D02G244900 and TraesCS5B02G236500) encoding ABA 8ʹ-hydroxylase were upregulated under drought treatment in AK58 but showed no change in JM47. The changes in the expression of genes involved in the ABA signalling pathway, such as PP2C (protein phosphatase 2C) and SnRK (SNF1-related protein kinase) genes, were similar to those related to ABA biosynthesis in the two cultivars (Fig. 7A; Supplementary data Table S8).

Fig. 7.

Hierarchical clustering of hormone-correlated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) based on log2 (CT_mean_fpkm/ CK_mean_fpkm) under drought treatment at 7 DAI in AK58 or JM47. Red represents upregulated expression, and green represents downregulated expression. (A) ABA-correlated DEGs, (B) ethylene-related DEGs, (C) auxin-related DEGs, (D) GA-related DEGs and (E) JA-related DEGs in AK58 or JM47. If the value for log2 (CT_mean_fpkm/ CK_mean_fpkm) exceeded the range between –6 and 6, it was treated as –6 or 6 in the heatmap.

The number of DEGs involved in ethylene metabolism was much higher in AK58 than in JM47 (Fig. 7B; Supplementary data Table S9).

The genes encoding indole-3-aldehyde oxidase (IAO) were downregulated in the two cultivars (Fig. 7C; Supplementary data Table S10); the expression of two common downregulated genes (TraesCS5D02G435900 and TraesCS5A02G427900) decreased more in AK58 than in JM47. The expression of genes involved in the auxin signalling pathway evidently changed; the number of up- and downregulated genes accounted for 55 % and 45 %, respectively, and included the genes for AUX (auxin transporter-like protein), AUX/IAA (auxin-induced protein 5NG4), ARF (auxin response factor), GH3 (auxin-responsive GH3-like protein) and SAUR (small auxin up RNA) (Fig. 7C; Supplementary data Table S10).

Moreover, the up- and downregulated DEGs related to gibberellin (GA) metabolism accounted for approx. 50 % each in AK58, while the expression of these genes hardly changed in JM47 (Fig. 7D; Supplementary data Table S11). In addition, DEGs associated with jasmonic acid were observed in the two cultivars (Fig. 7E; Supplementary data Table S12).

Identification of transcription factors (TFs) involved in the response to drought stress

In total, 427 DEGs encoding TFs were identified. AK58 (414) had more TF DEGs than JM47 (124), probably because AK58 was more sensitive to drought stress during germination and thus contributed more TF genes that participated in the response to drought stress. These DEGs belonged to 33 families (Table 1; Supplementary data Table S13). In addition, 164 and 250 TF genes were up- and downregulated in AK58, respectively, and 69 and 55 TF genes in JM47. Among these genes, ten families accounted for approx. 81 % of the stress response TF genes, namely WRKY (50), NAC (48), ERF (47), MYB (41), bHLH (43), bZIP (30), B3 (30), MYB-related (21), HB-other (20) and HSF (17).

Table 1.

The number of DEGs encoding transcription factors under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47

| TF family | The number of DEGs encoding TFs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AK58 | JM47 | Common | |

| AP2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| ARF | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| B3 | 30 | 6 | 6 |

| bHLH | 41 | 12 | 10 |

| bZIP | 30 | 18 | 18 |

| C2H2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| C3H | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| CO-like | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| DBB | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Dof | 13 | 2 | 2 |

| EIL | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| ERF | 43 | 15 | 11 |

| FAR1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| GRAS | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| HB-other | 20 | 2 | 2 |

| HD-ZIP | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| HSF | 16 | 13 | 12 |

| LBD (AS2/LOB) | 11 | 4 | 4 |

| LSD | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| M_type | 9 | 1 | 0 |

| MIKC | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| MYB | 39 | 13 | 11 |

| MYB_related | 21 | 3 | 3 |

| NAC | 45 | 18 | 15 |

| NF-YA | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Nin-like | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| RAV | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| SBP | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| SRS | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| TALE | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| TCP | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| WRKY | 50 | 8 | 8 |

| ZF-HD | 5 | 2 | 2 |

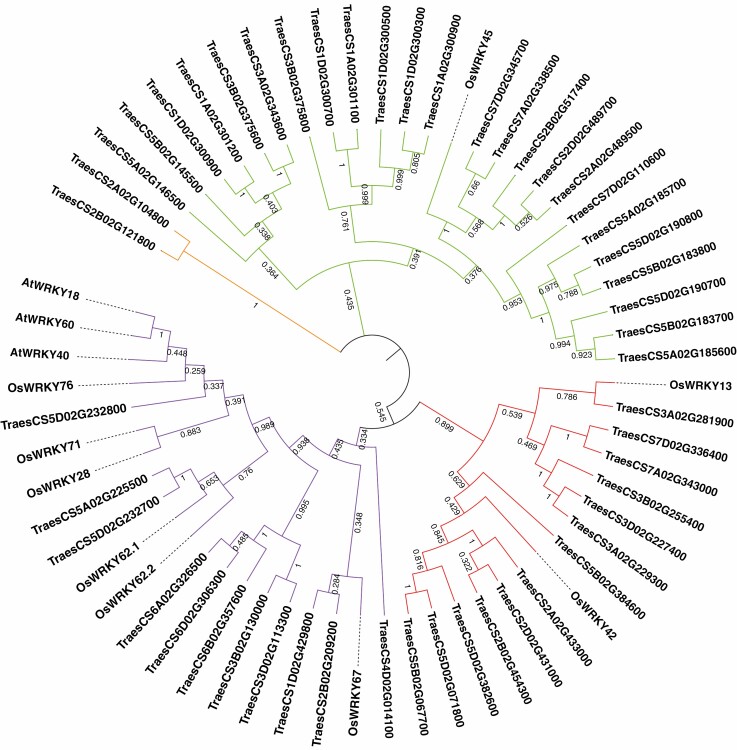

Wheat de novo transcriptome data were compared with or without drought treatment to identify the WRKY genes regulated by drought. A pairwise comparison revealed 50 WRKYs showing significantly downregulated transcription levels in AK58 or JM47 (Supplementary data Table S13). The amino acid sequences of 50 WRKYs in wheat are listed in Supplementary data Table S14. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA7.0 to investigate the evolutionary relationships of drought-responsive wheat WRKYs with previously reported WRKYs. In total, 24 drought-responsive wheat WRKYs belonged to Group I, 13 to Group II and 11 to Group III (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Unrooted phylogenetic tree representing relationships among 50 drought-responsive TaWRKY, nine OsWRKY and three AtWRKY members. The tree was constructed based on comparisons of amino acid sequences using the Neighbor–Joining method with bootstrap test (1000 replicates) in MEGA7. The percentages of replicates in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test are shown next to the main branches. The colours show the groups; green (group I), red (group II), purple (group III), orange (non-grouped) and black (non-grouped).

Identification of differential metabolites in AK58 and JM47 under drought stress during germination

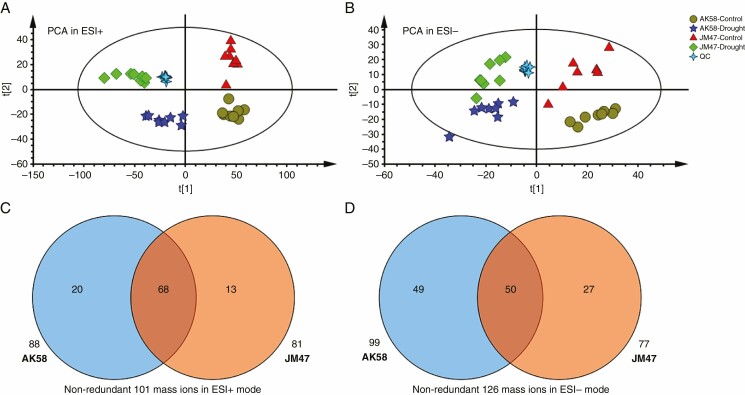

A total of 173 and 148 differential metabolites were detected in AK58 and JM47, respectively, by both ion modes (ESI+ and ESI–). There were 88 and 99 differential metabolites in ESI+ and ESI–, respectively, in AK58 and 81 and 77 in JM47 (Fig. 9C, D; Supplementary data Table S15). Many differential metabolites were shared between these two cultivars in response to drought stress (Fig. 9C, D). Multivariate data analyses [principal component analysis (PCA), partial least-squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) and orthogonal projections to latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA)] were performed to further evaluate the capability of the LC-MS-based metabolomics approach to distinguish between drought-stressed and well-watered conditions. Four principal components were identified in ESI (+) (R2X [1] = 0.41, R2X [2] = 0.0907) and ESI (–) (R2X [1] = 0.41, R2X [2] = 0.0907) (Fig. 9A, B). For AK58 and JM47, samples were only separated from the drought-stressed and well-watered conditions depending on these differential metabolites via PCA.

Fig. 9.

Principal component analysis (PCA) score plot based on differential metabolites under drought treatment at 7 DAI in the two cultivars derived from metabolite ions acquired from the (A) ESI+ and (B) ESI– mode. Potential markers were selected by comparing quantitative differences of mass ions in (C) ESI+ and (D) ESI– mode under drought treatment at 7 DAI in the two cultivars.

To identify the metabolic differences among the experimental groups and validate the model, we performed PLS-DA (Supplementary data Fig. S1) and 200 response sorting tests on the PLS-DA model (Supplementary data Fig. S2). The OPLS-DA models were constructed to identify the most significant metabolites (Supplementary data Fig. S3).

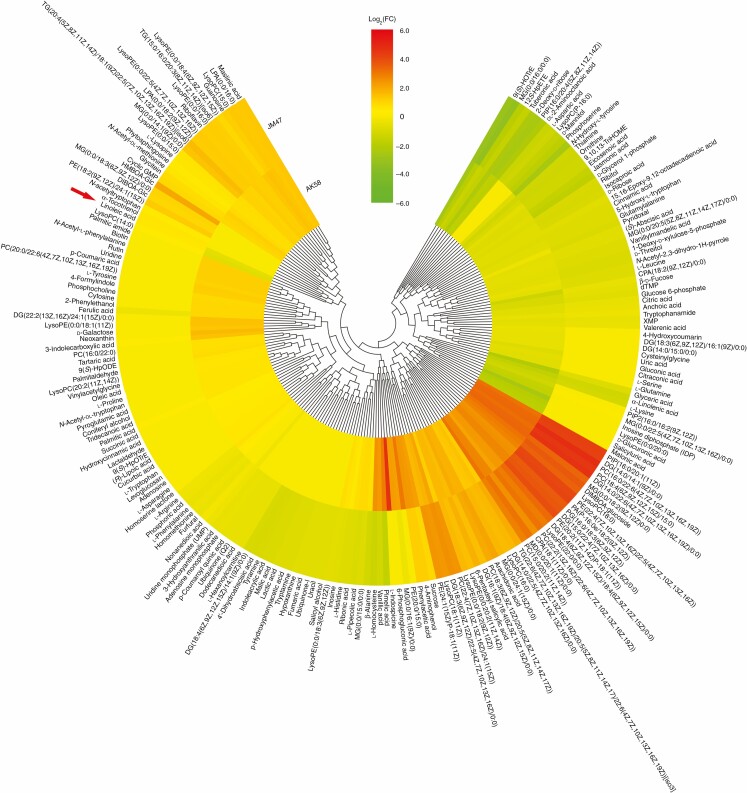

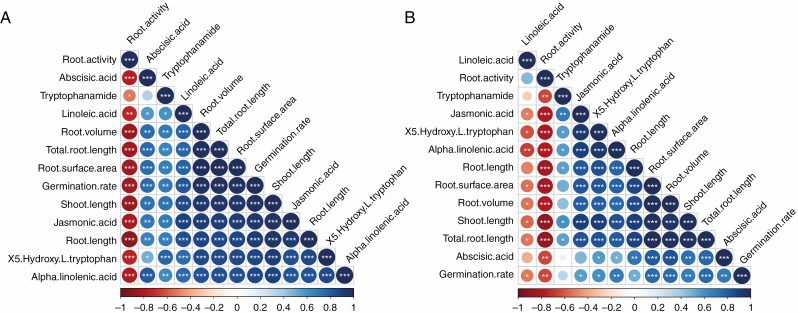

In total, 205 differential metabolites were detected in AK58 and JM47 (Fig. 10). Many of these showed different expression patterns in AK58 and JM47 (Fig. 10). Some differential metabolites were upregulated in both AK58 and JM47, including 6-pentadecyl salicylic acid, arachidonic acid, maslinic acid and riboflavin. However, some differential metabolites, such as malonic acid, d-glucuronic acid and salicyluric acid, were evidently downregulated in AK58 but barely changed in JM47. Based on metabolomic data, some hormones, such as ABA and jasmonic acid, changed strikingly in AK58 and JM47 under drought stress. The contents of both ABA and jasmonic acid decreased less in AK58 than in JM47. Linoleic acid and α-linolenic acid, precursors of jasmonic acid biosynthesis, exhibited significant differences. The content of α-linolenic acid decreased more in AK58 than in JM47 under drought stress. Intriguingly, linoleic acid content was significantly increased in JM47 but reduced in AK58 (Fig. 10). A Pearson correlation matrix was constructed for AK58 and JM47 to determine the correlation between hormones and various physiological and morphological traits (Fig. 11A, B). The contents of 5-hydroxy-l-tryptophan and tryptophanamide, precursors of auxin biosynthesis, were significantly positively correlated with various morphological traits in AK58 and JM47. However, the linoleic acid content was negatively correlated with all traits except for root activity in JM47, which was the opposite of AK58.

Fig. 10.

Hierarchical clustering of differential metabolites based on log2 (CT/CK) under drought treatment at 7 DAI in AK58 or JM47. Red represents upregulated expression, and green represents downregulated expression. If the value of log2 (CT/CK) exceeded the range of –6 and 6, it was treated as –6 or 6 in the heatmap.

Fig. 11.

Pearson’s correlation matrix of hormones and various physiological and morphological traits under drought treatment at 7 DAI in the two cultivars. (A) AK58 and (B) JM47. Blue represents positive correlations and red represents negative correlations, *P-values < 0.05, **P-values < 0.01, ***P-values < 0.001.

Analysis of KEGG pathways depending on differential metabolites

The KEGG enrichment analysis was conducted for all differential metabolites in AK58 and JM47 (Table 2), and six and four KEGG pathways were enriched in AK58 and JM47, respectively. Three KEGG pathways (linoleic acid metabolism, arachidonic acid metabolism and glycerophospholipid metabolism) were enriched in AK58 and JM47. Interestingly, linoleic acid significantly increased in JM47 but decreased in AK58 under drought stress.

Table 2.

KEGG pathways depending on differential metabolites in AK58 and JM47 under drought stress at 7 DAI

| Cultivars | KEGG ID | Pathway name | Metabolite ID | Metabolite | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AK58 | ko00591 | Linoleic acid metabolism | C00157 | Phosphatidylcholine | 0.0096907 |

| C01595 | Linoleic acid | ||||

| ko00590 | Arachidonic acid metabolism | C00219 | Arachidonic acid | 0.039348 | |

| C00157 | Phosphatidylcholine | ||||

| ko00564 | Glycerophospholipid metabolism | C00350 | Phosphatidylethanolamine | 0.044563 | |

| C00157 | Phosphatidylcholine | ||||

| C04230 | LysoPC(18:1(9Z)) | ||||

| ko00970 | Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | C00152 | l-Asparagine | 0.02315 | |

| C00135 | l-Histidine | ||||

| C00079 | l-Phenylalanine | ||||

| C00062 | l-Arginine | ||||

| C00064 | l-Glutamine | ||||

| C00065 | l-Serine | ||||

| C00078 | l-Tryptophan | ||||

| C00082 | l-Tyrosine | ||||

| C00148 | l-Proline | ||||

| ko00360 | Phenylalanine metabolism | C00079 | l-Phenylalanine | 0.028849 | |

| C05629 | Hydrocinnamic acid | ||||

| C00811 | 4-Hydroxycinnamic acid | ||||

| ko00940 | Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | C00079 | l-Phenylalanine | 0.043467 | |

| C00082 | l-Tyrosine | ||||

| C00811 | 4-Hydroxycinnamic acid | ||||

| C01494 | Ferulate | ||||

| C00590 | Coniferyl alcohol | ||||

| JM47 | ko00591 | Linoleic acid metabolism | C00157 | Phosphatidylcholine | 0.0091833 |

| C01595 | Linoleic acid | ||||

| ko00590 | Arachidonic acid metabolism | C00219 | Arachidonic acid | 0.037397 | |

| C00157 | Phosphatidylcholine | ||||

| ko00564 | Glycerophospholipid metabolism | C00350 | Phosphatidylethanolamine | 0.041547 | |

| C00157 | Phosphatidylcholine | ||||

| C04230 | LysoPC(18:1(9Z)) | ||||

| ko00410 | β-Alanine metabolism | C00049 | l-Aspartic acid | 0.015616 |

‘Metabolite ID’ represents the accession number of the substance in the KEGG database; P-values < 0.05 represent that the pathway is significantly enriched.

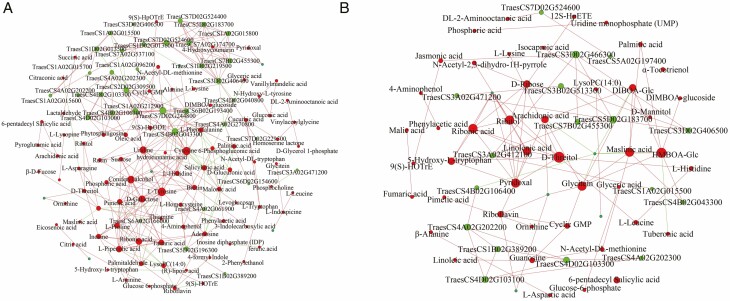

Network analysis of the transcriptome and metabolomics

Network analysis was performed on the transcriptome and metabolomics data to further explore the mechanisms of drought resistance during germination. In our study, the top ten KEGG pathways focused on the greatest number of DEGs or differential metabolites (Supplementary data Fig. S4). KEGG enrichment analysis was conducted to integrate differential metabolites and DEGs (Supplementary data Fig. S5); pathways of lipid and amino acid metabolism (e.g. cyanoamino acid metabolism, glycerophospholipid metabolism, linoleic acid metabolism and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis) (Supplementary data Fig. S5A) and signal transduction (e.g. the mTOR signalling pathway, glucagon signalling pathway and oxytocin signalling pathway) (Supplementary data Fig. S5B) were evidently enriched in AK58 and JM47 under drought stress, respectively. Furthermore, these two pathways (plant hormone signal transduction and α-linolenic acid metabolism) were remarkably enriched in the two cultivars. The α-linolenic acid content decreased more in AK58 than in JM47, which was consistent with the expression pattern of DEGs involved in auxin biosynthesis under drought stress. A network analysis was conducted to determine the correlation between metabolites and DEGs. The results showed that 1693 DEGs had strong correlation coefficient values (|R| >0.9) with 145 differentially expressed metabolites in AK58, whereas 642 DEGs were strongly relevant to 105 differentially expressed metabolites in JM47 (|R| >0.9) (Supplementary data Table S16). Based on the enriched KEGG pathways in both transcriptome and metabolomics analyses, emphasis was placed on plant hormone signal transduction, the mTOR pathway and α-linolenic acid metabolism. Some DEGs enriched in the ‘α-linolenic acid’ pathway strongly correlated with differential metabolites in the two cultivars (Table 3; Supplementary data Table S17). Moreover, some ABA-related DEGs were strongly correlated with differential metabolites in AK58 and JM47 (Table 4; Supplementary data Table S8). To understand the regulatory network of seed germination, a network analysis of DEGs enriched in the ‘α-linolenic acid’ pathway and differential metabolites was conducted in AK58 (Fig. 12A) and JM47 (Fig. 12B). Based on the results of DEGs enriched in the ‘α-linolenic acid’ pathway and differential metabolites, 12 genes showed higher correlation coefficient values (R > 0.9) with 19 differential metabolites in AK58, of which one gene (TraesCS3A02G471200) encoded salicylate O-methyltransferase. Four genes showed higher correlation coefficient values (R > 0.9) with five differential metabolites in JM47, of which one (TraesCS3D02G466300) encoded jasmonate O-methyltransferase. Furthermore, network analysis of ABA- and auxin-related DEGs and differential metabolites was conducted in the two cultivars (Supplementary data Fig. S6). The results showed a difference in the germination and complex regulatory networks between the two cultivars under drought stress.

Table 3.

Interaction value between metabolites and genes enriched in the α-linolenic acid metabolism pathway in AK58 and JM47 under drought stress at 7 DAI

| Cultivars | Gene | Metabolite | Pearson’s correlation (R) | P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AK58 | TraesCS5A02G193900 | dTMP | –9.97E-01 | 1.80E-05 | 7.30E-05 |

| TraesCS4A02G061900 | Sucrose | 9.96E-01 | 2.75E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS3D02G406500 | LysoPE(0:0/20:0) | 9.97E-01 | 1.58E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS5D02G196300 | l-Asparagine | 9.95E-01 | 3.12E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS4B02G043300 | Ribitol | –9.95E-01 | 3.55E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS1A02G096200 | Tryptophanamide | 9.98E-01 | 9.12E-06 | 7.30E-05 | |

| JM47 | TraesCS7D02G524600 | DG(16:1(9Z)/18:4(6Z,9Z,12Z,15Z)/0:0) | –9.91E-01 | 1.14E-04 | 9.31E-06 |

| TraesCS3D02G466300 | α-Tocotrienol | –9.91E-01 | 1.29E-04 | 9.31E-06 | |

| TraesCS3D02G406500 | Ubiquinone-1 | 9.93E-01 | 7.26E-05 | 9.31E-06 |

Negative Pearson’s correlation values represent a negative correlation of the gene and metabolite, and positive values represent a positive correlation.

P-value < 0.05 represents a significant correlation of gene and metabolite, FDR represents the corrected P-value.

Table 4.

Interaction value between metabolites and genes related to ABA in AK58 and JM47 under drought stress at 7 DAI

| Cultivars | Gene | Metabolite | Pearson’s correlation (R) | P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AK58 | TraesCS5D02G558800 | l-Proline | 9.99E-01 | 2.79E-06 | 7.30E-05 |

| TraesCS1B02G381500 | CPA(18:1(11Z)/0:0) | 9.98E-01 | 7.29E-06 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS3B02G578400 | Malonic acid | 9.96E-01 | 2.68E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS4D02G078100 | Vanillic acid | 9.97E-01 | 1.36E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS4B02G189800 | Palmitic amide | –9.95E-01 | 3.67E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS2D02G493700 | 4-Aminophenol | 9.96E-01 | 1.90E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS4D02G191200 | Uridine | –9.97E-01 | 1.40E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS4A02G235600 | MG(0:0/24:1(15Z)/0:0) | 9.99E-01 | 1.27E-06 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS3A02G154400 | DG(15:0/22:4(7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z)/0:0) | –9.97E-01 | 1.04E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS7A02G170600 | Coniferyl alcohol | 9.95E-01 | 3.39E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS2B02G523600 | DG(15:0/22:4(7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z)/0:0) | 9.96E-01 | 2.59E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS4A02G128900 | l-Asparagine | –9.96E-01 | 2.57E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS1B02G381800 | l-Proline | 9.97E-01 | 1.76E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS3D02G254100 | l-Pipecolic acid | 9.97E-01 | 1.64E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS1A02G083800 | 4-Aminophenol | 9.99E-01 | 5.24E-07 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS1B02G381400 | CPA(18:1(11Z)/0:0) | 9.97E-01 | 1.58E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS1A02G364400 | 4-Aminophenol | 9.96E-01 | 2.41E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS1D02G369800 | l-Pipecolic acid | 9.99E-01 | 2.27E-06 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS1B02G381200 | CPA(18:1(11Z)/0:0) | 9.96E-01 | 2.08E-05 | 7.30E-05 | |

| TraesCS4B02G332700 | PIP(16:0/20:1(11Z)) | 9.98E-01 | 3.46E-06 | 7.30E-05 | |

| JM47 | TraesCS4A02G066200 | Cyclic GMP | –9.92E-01 | 9.86E-05 | 9.31E-06 |

| TraesCS3D02G517300 | l-Leucine | 9.91E-01 | 1.30E-04 | 9.31E-06 | |

| TraesCS7D02G328000 | (S)-Abscisic acid | 9.94E-01 | 5.30E-05 | 9.31E-06 |

Negative Pearson’s correlation values represent a negative correlation of the gene and metabolite, and positive values represent a positive correlation.

P-value < 0.05 represents a significant correlation of gene and metabolite, FDR represents the corrected P-value.

Fig. 12.

Connection network between differentially expressed genes (DEGs) enriched in the α-linolenic acid pathway and differential metabolites in the two cultivars. Green nodes represent genes and red nodes represent metabolites. The size of the node represents the number of related genes or metabolites. Red lines represent a positive correlation and green lines represent a negative correlation. (A) in AK58 and (B) in JM47.

DISCUSSION

Phytohormone signals during germination under drought stress

Phytohormones play vital roles in co-ordinating many signal transduction pathways during germination under stressful conditions (Miransari and Smith, 2014). In this study, according to transcriptome data, the expression of genes involved in hormone signalling pathways was altered under drought stress during germination. ABA is considered a crucial messenger in the response to germination and stress (Zhao et al., 2018). NCED, a rate-limiting enzyme, is crucial in ABA biosynthesis (Schwartz et al., 2003). 8ʹ-Hydroxylase is an important enzyme involved in ABA catabolism. A previous study reported that the expression levels of upregulated NCED genes in roots were higher in JM-262 (drought-tolerant wheat cultivar) than in LM-2 (drought-susceptible wheat cultivar) under drought stress at 48 h after treatment) which contributed to the higher ABA content of JM-262 at that time (Hu et al., 2018). In our study, five NCED genes and two genes encoding 8ʹ-hydroxylase were upregulated in AK58 but were not changed in JM47 under drought treatment. Moreover, the ABA content of the two cultivars was reduced, suggesting that the synthesis of ABA might be elevated in the drought-sensitive cultivar AK58 and promote seed dormancy. ABA produced in the root cap quickly passed (Sengupta et al., 2011) through the xylem to the shoot, which inhibited the germination process; therefore, ABA content might be reduced under drought at 7 DAI. However, the expression of NCED genes hardly changed in JM47, which contributed to the high germination rate. The clear regulation of genes involved in ABA biosynthesis and catabolism suggests the presence of dynamic and multifaceted mechanisms that control ABA content in response to stress. Moreover, PYL, SnRK2 and PP2C genes, key components of the ABA signalling pathway, were investigated as a response to drought stress during germination. PYLs are proposed to be ABA receptors, and PP2Cs and SnRKs act as negative and positive regulators, respectively (Park et al., 2010). The pyl and snrk mutants exhibited poor germination rates under osmotic stress conditions (Zhao et al., 2018). Interestingly, in our study, the ABA content decreased under drought stress in the two cultivars, and the reduction was greater in JM47 than in AK58, perhaps because 8ʹ-hydroxylase functions in catabolism and accelerates the decomposition of ABA. Furthermore, the ABA content was significantly positively correlated with the content of linoleic acid in AK58, which was the opposite of that in JM47 (Fig. 11). Linoleic acid is a precursor of jasmonic acid; therefore, the drought resistance of JM47 might be closely related to the interaction between jasmonic acid and ABA. Additionally, common DEGs encoding PYL were downregulated less, and common DEGs encoding SnRK2 were upregulated more in JM47 than in AK58. Therefore, PYLs may interact with and inhibit osmotic stress-activated SnRK2 protein kinases (Zhao et al., 2018), which might lead to a greater reduction of ABA content in JM47 than in AK58 and improve drought resistance in JM47 during germination. SnRK2 genes (TraesCS4D02G078100 and TraesCS4A02G235600), PYL (TraesCS3A02G154400) and NCED (TraesCS5D02G038800) play vital roles in the regulation network of ABA-related genes and differential metabolites in AK58 (Supplementary data Fig. 6SA). In JM47, SnRK2 genes (TraesCS2A02G493800 andTraesCS2B02G521800) and PP2C (TraesCS2D02G000300) played crucial roles in the regulation network (Supplementary data Fig. 6SB); these genes were significantly correlated with many genes and differential metabolites. There might be a difference between AK58 and JM47 due to the complicated expression patterns of these genes. Furthermore, ABA signalling interacts with other hormone signalling pathways and forms a complex network to control lateral root development and seed germination (Gou et al., 2010; Hu and Yu, 2014).

Previously, extensive cross-talk has been reported, and ethylene signalling has been implicated in drought stress response (Balbi and Devoto, 2008; Kazan, 2015). Ethylene response factors (ERFs) are the major downstream regulatory factors of the ethylene signalling pathway in stress responses. The transcription factor ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 (EIN3) was suggested to induce ERF1 gene expression in response to ethylene and to activate defence responses (Solano et al., 1998). In our study, the expression of EIN3 and ETR genes increased under drought stress in both cultivars. Overexpression of ERF significantly improves resistance to various abiotic stressors in tobacco (L. Wu et al., 2008). Interestingly, two ERF genes were downregulated in AK58 but showed no change in JM47; therefore, it might be a factor that results in drought resistance during germination.

Indole-3-aldehyde oxidase is a key enzyme in the indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) biosynthesis pathway, and eight IAO genes were specifically upregulated in JM-262 (drought-tolerant cultivar) or only downregulated in LM-2 (susceptible cultivar) in wheat (Won et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2018). In our study, the expression of two genes encoding IAO was strikingly decreased in JM47 (drought-resistant cultivar) under drought stress. Interestingly, our results were the opposite to thos of the previous study (Hu et al., 2018); perhaps we focused on germination and not the seedling stage, and drought treatment duration also affected the expression of genes. The interaction of various hormones contributes to the complex germination process under drought stress (Miransari and Smith, 2014). The two IAO genes were downregulated more in AK58 than in JM47, which might lead to stronger drought resistance in JM47. Moreover, these two IAO genes play key roles in the regulation network (Supplementary data Fig. S6C, D). SAUR genes also strongly correlate with many auxin-related genes and differential metabolites. These factors might contribute to drought resistance during germination.

Gibberellin plays a key role in regulating seed dormancy, germination, metabolism and signalling (Shu et al., 2015, 2016). GID1 is a GA receptor that determines the GA signal transduction (Ariizumi et al., 2011). In our study, most GID1 DEGs were downregulated in AK58 but showed no change in JM47, suggesting that JM47 may be free from adverse conditions and has sufficient energy to germinate. In summary, various hormonal signals may affect the expression and regulation of several downstream genes that are important during seed germination.

TFs involved in drought stress during germination

Transcription factors play critical roles in seed germination under stress (Yang et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2021). Some of the major TF families are AP2/ERF, ARF, ABI3VP1, bZIP/HD-ZIP, C2H2, GRAS, MYB/MYC, zinc fingers, MADS, NAC and WRKY, which are related to drought tolerance (Gahlaut et al., 2016). In our study, 414 and 124 genes encoded TFs that responded to drought stress during germination in AK58 and JM47, respectively. The largest group of drought-inducible TFs belonged to the WRKY and bZIP families, composed of 50 and 18 members in AK58 and JM47, respectively. Transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana lines overexpressing VlbZIP36 showed enhanced dehydration tolerance during the seed germination stage through transcriptional regulation of ABA- and stress-related genes (Tu et al., 2016). Overexpression of TaWRKY1 and TaWRKY33 activates several stress-related downstream genes, increases germination rates and promotes root growth in arabidopsis under drought stress (He et al., 2016). Drought stress induced TaWRKY19 and TaWRKY2 to a peak value at 3 and 12 h after treatment initiation, respectively, whereas TaWRKY17 expression was increased in leaves but decreased in roots (Niu et al., 2012). H. Wu et al. (2008) found that the expression of some TaWRKY genes, including TaWRKY10, TaWRKY46, TaWRKY68-a and TaWRKY72-b, was upregulated in leaves after 20 % PEG treatment for 4 h. Expression of TaWRKY10 in wheat cv. Chinese spring was induced and reached a maximum level at 1 h after 20 % PEG treatment (Wang et al., 2013). In our study, the bZIP family accounted for the largest proportion of TF family members in JM47. Intriguingly, all WRKY family genes were downregulated in AK58 but were nearly unchanged in JM47, which might be because WRKY gene expression reached a maximum level within a few hours. At 7 DAI, the expression of WRKY genes remained stable in JM47, whereas the DEGs were all downregulated in AK58, which probably affected drought resistance during germination. In addition, there is a clear difference between the number of other TFs regulated in AK58 and JM47, such as AFR, Dof and NAC, which are closely related to the auxin-activated signalling pathway, positive regulation of seed germination and improvement of drought tolerance, respectively (Santopolo et al., 2015; Mao et al., 2022). In our study, almost all of the genes encoding AFR, Dof and NAC TFs were downregulated in AK58 but barely changed in JM47, which might be closely related to stronger drought resistance during seed germination in JM47. DEGs encoding some TFs, such as bHLH and bZIP, were both up- and downregulated. In general, all DEGs encoding TFs were much higher in AK58 than in JM47, which might be because stronger drought resistance led to fewer genes significantly affected by drought stress; therefore, the number of DEGs encoding TFs was lower in JM47 than in AK58. However, further research is required to verify whether these TFs function independently or synergistically to enhance drought resistance during wheat germination.

Integrated analysis of the transcriptome and metabolomics

α-Linolenic acid metabolism plays a key role in the signal transduction pathway induced by abiotic stress, which can enhance resistance during germination (Upchurch, 2008; Torres-Franklin et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2014). In JM47, the gene (TraesCS3D02G466300) encoding jasmonate O-methyltransferase, which is enriched in α-linolenic acid metabolism, had strong correlations with α-tocotrienol. The remarkably increased α-tocotrienol may have improved drought resistance during germination, which is in agreement with previous reports (Chen et al., 2016). Moreover, the gene encoding jasmonate O-methyltransferase plays a core role in the regulation network in JM47 (Fig. 12B), which might be helpful in studying seed germination under drought stress.

Signalling by mTOR positively regulates plant growth and is strongly related to ABA biosynthesis and distribution. The ABA content was decreased in raptorb seedlings, and the genes (NECD3 and AOO3) encoding vital enzymes in ABA biosynthesis were downregulated (Kravchenko et al., 2015). However, the ABA content of the raptorb mutant seeds increased (Salem et al., 2017). YAK1 and ABI4, two significant downstream regulators of TOR signalling, were verified as two key mediators of ABA that control seed germination, root growth and meristem activation via a genetic screen of resistance to the TOR inhibitor AZD-8055 (Li et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2016; Barrada et al., 2019). Plants always transiently sacrifice growth while triggering protective stress responses upon sensing stress. Recently, it was reported that the balance between plant growth and stress adaptation is regulated by the interaction between TOR and ABA signalling (Wang et al., 2018). TOR phosphorylates a highly conserved serine of PYL to abolish its binding activity to ABA, which compromises ABA signalling in unstressed arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2018). The raptorb and lst8-1 mutants exhibited high sensitivity to exogenous ABA application (Salem et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). Furthermore, ABA antagonizes TOR signalling. ABA-activated SnRK2s directly interact with and phosphorylates RaptorB. RaptorB disassociates from the TOR complex due to phosphorylation, which inhibits TOR kinase activity (Wang et al., 2018). Therefore, active TOR promotes growth by inhibiting ABA signalling under nutrient-rich conditions. In contrast, under stress conditions, ABA signalling is activated, which contributes to the inhibition of TOR activity by activating SnRK2, sacrificing growth for survival under stress. Remarkably, several PYL receptors can bind to and inhibit PP2Cs even without ABA in arabidopsis (Hao et al., 2011; Fujii and Zhu, 2012), whereas the phosphor-mimicking mutation of the TOR phosphorylation site within PYL10 disrupts this ABA-independent binding to PP2Cs (Wang et al., 2018). Therefore, the activation of ABA-independent PYLs may be restrained by TOR under normal conditions, which promotes growth and development. In our study, network analysis of the transcriptome and metabolomic data revealed that the mTOR signalling pathway was highly and significantly enriched in JM47. Moreover, a previous study revealed a Tai-Chi model of TOR–ABA signalling to balance plant growth and stress response (Fu et al., 2020); TOR served as a negative regulatory factor for stress response in the model. In our study, most TOR DEGs were downregulated due to drought stress, which probably sacrificed growth to enhance drought resistance, consistent with the model. Under drought treatment, ABA content in roots and shoots was measured in the two cultivars at 7 DAI (Supplementary data Fig. S7). The results of ABA content in the roots were consistent with the metabolomics data. Interestingly, ABA content in roots and shoots decreased and increased, respectively, under drought treatment at 7 DAI. Moreover, DEGs involved in the mTOR signalling pathway were also involved in signalling pathways (e.g. the PI3K–Akt signalling pathway, AMPK signalling pathway and circadian rhythm), and these three signalling pathways were only enriched in JM47 under drought stress (Fig. 6; Supplementary data Table S6). This could be due to mTOR regulation. Additionally, the DEGs encoding SnRK2 were upregulated in the two cultivars, which agreed with previous reports (Salem et al., 2017). Under stress conditions, mTOR–ABA signalling is activated, and ABA produced in roots is rapidly transferred to the shoots through the xylem. The ABA content in the shoots is higher in AK58 than in JM47 under drought treatment (Supplementary data Fig. S7B). Additionally, Fu et al. (2020) reported that ABA- activated SnRK2 phosphorylates Raptor to decrease TOR activity and sacrifice growth for survival during stress, which is consistent with our results. TOR–ABA signalling activates the drought resistance mechanism in JM47, which regulates the distribution of ABA. At 7 DAI, the ABA content in shoots was significantly lower in JM47 than in AK58 under drought treatment, which might lead to better performance by JM47. We predicted that mTOR–ABA signalling might contribute to the mechanism of drought resistance during seed germination.

Conclusions

In the present study, we report that mTOR–ABA signalling is more active in JM47 than in AK58, which determines drought resistance owing to different regulation of hormone signalling, especially the high-efficiency regulation of ABA content between roots and shoots during seed germination under drought stress. Additionally, the activation of α-linolenic acid metabolic pathways plays a vital role in drought resistance in JM47. Some nutrients, such as linoleic acid, α-tocotrienol and l-leucine, accumulate to promote germination in JM47 under drought stress. These are promising candidates for improving drought resistance during germination. The DEGs that contribute to activating mTOR–ABA signalling and α-linolenic acid metabolism pathways were considered candidate DEGs, because they could introduce comprehensive and systemic effects in plant resistance to drought by the interaction of various hormones.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Table S1: the primers used in quantitative real-time PCR. Table S2: quality summary of transcriptome data. Table S3: all differentially expressed genes under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S4: Gene Ontology enrichments of differentially expressed genes under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S5: differentially expressed genes annotated as protein kinases under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S6: differentially expressed genes enriched in signalling pathways under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S7: differentially expressed genes enriched in the calcium ion signalling pathway under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S8: ABA-related differentially expressed genes under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S9: ethylene-related differentially expressed genes under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S10: auxin-related differentially expressed genes under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S11: gibberellin-related differentially expressed genes under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S12: jasmonic acid-related differentially expressed genes under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S13: DEG-related transcription factors under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S14: amino acid sequences of drought-responsive WRKYs in the two wheat cultivars. Table S15: differential metabolites detected in AK58 and JM47 and their basic information under drought stress at 7 DAI. Table S16: interaction value between differential metabolites and differentially expressed genes under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Table S17: KEGG pathway enrichments of differentially expressed genes under drought stress at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Figure S1: PLS-DA score plot based on differential metabolites under drought treatment at 7 DAI in two cultivars. Figure S2: multivariate statistical analysis of 200 permutation tests of PLS-DA in AK58 or JM47 under drought treatment at 7 DAI. Figure S3: OPLS-DA score plot based on differential metabolites under drought treatment at 7 DAI in the two cultivars. Figure S4: KEGG pathway (top 10) enrichment analysis of containing the most number of DEGs or differential metabolites in AK58 or JM47. Figure S5: −log100(FDR) of KEGG pathway in both transcriptome and metabolome under drought treatment at 7 DAI in AK58 and JM47. Figure S6: connection network between ABA- and auxin-related DEGs and differential metabolites in two cultivars. Figure S7: effects of drought stress on ABA content in root and shoot in AK58 and JM47. Method S1: measurements of physiological and morphological traits. Method S2: library preparation and transcriptome sequencing analysis. Method S3: metabolite extraction and analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions about the manuscript. All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the published article and supplementary data files. All sequencing data have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) with accession number: PRJNA733882. The reviewer link to access the data is: https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA733882?reviewer=dbvktt74q0ds9vgdn3enllu4m2

Contributor Information

Zongzhen Li, College of Agronomy, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China.

Yanhao Lian, College of Agronomy, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China.

Pu Gong, College of Agronomy, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China.

Linhu Song, College of Agronomy, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China.

Junjie Hu, College of Agronomy, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China.

Haifang Pang, College of Agronomy, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China.

Yongzhe Ren, College of Agronomy, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China.

Zeyu Xin, College of Agronomy, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China.

Zhiqiang Wang, College of Agronomy, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China.

Tongbao Lin, College of Agronomy, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China.

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (no. 2016YFD0300205) and Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province (202102110025). These funding bodies have had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

LITERATURE CITED

- Ariizumi T, Lawrence PK, Steber CM.. 2011. The role of two F-box proteins, SLEEPY1 and SNEEZY, in Arabidopsis gibberellin signaling. Plant Physiology 155: 765–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi A, Moin M, Kumar MU, et al. 2017. Ectopic expression of Arabidopsis Target of Rapamycin (AtTOR) improves water-use efficiency and yield potential in rice. Scientific Reports 7: 42835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi A, Moin M, Madhav MS, Kirti PB.. 2019. Target of rapamycin, a master regulator of multiple signalling pathways and a potential candidate gene for crop improvement. Plant Biology 21: 190–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbi V, Devoto A.. 2008. Jasmonate signalling network in Arabidopsis thaliana: crucial regulatory nodes and new physiological scenarios. New Phytologist 177: 301–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrada A, Djendli M, Desnos T, et al. 2019. A TOR–YAK1 signaling axis controls cell cycle, meristem activity and plant growth in Arabidopsis. Development 146: dev171298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Li Y, Fang T, Shi X, Chen X.. 2016. Specific roles of tocopherols and tocotrienols in seed longevity and germination tolerance to abiotic stress in transgenic rice. Plant Science 244: 31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chono M, Matsunaka H, Seki M, et al. 2013. Isolation of a wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) mutant in ABA 8ʹ-hydroxylase gene: effect of reduced ABA catabolism on germination inhibition under field condition. Breeding Science 63: 104–115. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.63.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprost D, Yao L, Sormani R, et al. 2007. The Arabidopsis TOR kinase links plant growth, yield, stress resistance and mRNA translation. EMBO Reports 8: 864–870. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch-Savage WE, Leubner-Metzger G.. 2006. Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytologist 171: 501–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L, Wang P, Xiong Y.. 2020. Target of rapamycin signaling in plant stress responses. Plant Physiology 182: 1613–1623. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Zhu JK.. 2012. Osmotic stress signaling via protein kinases. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 69: 3165–3173. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1087-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahlaut V, Jaiswal V, Kumar A, Gupta PK.. 2016. Transcription factors involved in drought tolerance and their possible role in developing drought tolerant cultivars with emphasis on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 129: 2019–2042. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2794-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg AK, Kim JK, Owens TG, et al. 2002. Trehalose accumulation in rice plants confers high tolerance levels to different abiotic stresses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 99: 15898–15903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252637799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou J, Strauss SH, Tsai CJ, et al. 2010. Gibberellins regulate lateral root formation in Populus through interactions with auxin and other hormones. The Plant Cell 22: 623–639. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.073239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Rico-Medina A, Caño-Delgado AI.. 2020. The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science 368: 266–269. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz7614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Q, Yin P, Li W, et al. 2011. The molecular basis of ABA-independent inhibition of PP2Cs by a subclass of PYL proteins. Molecular Cell 42: 662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He GH, Xu JY, Wang YX, et al. 2016. Drought-responsive WRKY transcription factor genes TaWRKY1 and TaWRKY33 from wheat confer drought and/or heat resistance in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biology 16: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Xie Y, Fan S, et al. 2018. Comparative analysis of root transcriptome profiles between drought-tolerant and susceptible wheat genotypes in response to water stress. Plant Science 272: 276–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Yu D.. 2014. BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE2 interacts with ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE5 to mediate the antagonism of brassinosteroids to abscisic acid during seed germination in arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 26: 4394–4408. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.130849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izydorczyk C, Nguyen TN, Jo SH, Son SH, Tuan PA, Ayele BT.. 2018. Spatiotemporal modulation of abscisic acid and gibberellin metabolism and signalling mediates the effects of suboptimal and supraoptimal temperatures on seed germination in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant, Cell & Environment 41: 1022–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazan K. 2015. Diverse roles of jasmonates and ethylene in abiotic stress tolerance. Trends in Plant Science 20: 219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Ntui VO, Xiong L.. 2016. Arabidopsis YAK1 regulates abscisic acid response and drought resistance. FEBS Letters 590: 2201–2209. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, To TK, Matsui A, et al. 2017. Acetate-mediated novel survival strategy against drought in plants. Nature Plants 3: 4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravchenko A, Citerne S, Jéhanno I, et al. 2015. Mutations in the Arabidopsis Lst8 and Raptor genes encoding partners of the TOR complex, or inhibition of TOR activity decrease abscisic acid (ABA) synthesis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 467: 992–997. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Song Y, Wang K, et al. 2015. TOR-inhibitor insensitive-1 (TRIN1) regulates cotyledons greening in Arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science 6: 861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD.. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2–ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Dai Y, Zheng C, et al. 2021. The ABI4–RbohD/VTC2 regulatory module promotes reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation to decrease seed germination under salinity stress. New Phytologist 229: 950–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H, Li S, Chen B, et al. 2022. Variation in cis-regulation of a NAC transcription factor contributes to drought tolerance in wheat. Molecular Plant 15: 276–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miransari M, Smith DL.. 2014. Plant hormones and seed germination. Environmental and Experimental Botany 99: 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Niu CF, Wei W, Zhou QY, et al. 2012. Wheat WRKY genes TaWRKY2 and TaWRKY19 regulate abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant, Cell & Environment 35: 1156–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuccio ML, Wu J, Mowers R, et al. 2015. Expression of trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase in maize ears improves yield in well-watered and drought conditions. Nature Biotechnology 33: 862–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Fung P, Nishimura N, et al. 2010. Abscisic acid inhibits PP2Cs via the PYR/PYL family of ABA-binding START proteins. Science 324: 1068–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem MA, Li Y, Wiszniewski A, Giavalisco P.. 2017. Regulatory-associated protein of TOR (RAPTOR) alters the hormonal and metabolic composition of Arabidopsis seeds, controlling seed morphology, viability and germination potential. The Plant Journal 92: 525–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santopolo S, Boccaccini A, Lorrai R, et al. 2015. DOF AFFECTING GERMINATION 2 is a positive regulator of light-mediated seed germination and is repressed by DOF AFFECTING GERMINATION 1. BMC Plant Biology 15: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SH, Qin X, Zeevaart JAD.. 2003. Elucidation of the indirect pathway of abscisic acid biosynthesis by mutants, genes, and enzymes. Plant Physiology 131: 1591–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta D, Kannan M, Reddy AR.. 2011. A root proteomics-based insight reveals dynamic regulation of root proteins under progressive drought stress and recovery in Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek. Planta 233: 1111–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu K, Meng YJ, Shuai HW, et al. 2015. Dormancy and germination: how does the crop seed decide? Plant Biology 17: 1104–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu K, Liu XD, Xie Q, He ZH.. 2016. Two faces of one seed: hormonal regulation of dormancy and germination. Molecular Plant 9: 34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano R, Stepanova A, Chao Q, Ecker JR.. 1998. Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes & Development 12: 3703–3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taji T, Ohsumi C, Iuchi S, et al. 2002. Important roles of drought- and cold-inducible genes for galactinol synthase in stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 29: 417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Franklin ML, Repellin A, Huynh VB, d’Arcy-Lameta A, Zuily-Fodil Y, Pham-Thi AT.. 2009. Omega-3 fatty acid desaturase (FAD3, FAD7, FAD8) gene expression and linolenic acid content in cowpea leaves submitted to drought and after rehydration. Environmental and Experimental Botany 65: 162–169. [Google Scholar]

- Tu M, Wang X, Feng T, et al. 2016. Expression of a grape (Vitis vinifera) bZIP transcription factor, VlbZIP36, in Arabidopsis thaliana confers tolerance of drought stress during seed germination and seedling establishment. Plant Science 252: 311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch RG. 2008. Fatty acid unsaturation, mobilization, and regulation in the response of plants to stress. Biotechnology Letters 30: 967–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano K, Maruyama K, Ogata Y, et al. 2009. Characterization of the ABA-regulated global responses to dehydration in Arabidopsis by metabolomics. The Plant Journal 57: 1065–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Deng P, Chen L, et al. 2013. A wheat WRKY transcription factor TaWRKY10 confers tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in transgenic tobacco. PLoS One 8: e65120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Zhao Y, Li Z, et al. 2018. Reciprocal regulation of the TOR kinase and ABA receptor balances plant growth and stress response. Molecular Cell 69: 100–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang X, Huang G, et al. 2019. iTRAQ-based quantitative analysis of responsive proteins under PEG-induced drought stress in wheat leaves. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20: 2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler EW, Jourdan PS, Conrad W.. 1981. Levels of indole-3-acetic acid in intact and decapitated coleoptiles as determined by a specific and highly sensitive solid-phase enzyme immunoassay. Planta 153: 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won C, Shen X, Mashiguchi K, et al. 2011. Conversion of tryptophan to indole-3-acetic acid by tryptophan aminotransferases of Arabidopsis and YUCCAs in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 108: 18518–18523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Ni Z, Yao Y, Guo G, Sun Q.. 2008. Cloning and expression profiles of 15 genes encoding WRKY transcription factor in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Progress in Natural Science 18: 697–705. [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Wang XC, Huang R.. 2008. Transcriptional modulation of ethylene response factor protein JERF3 in the oxidative stress response enhances tolerance of tobacco seedlings to salt, drought, and freezing. Plant Physiology 148: 1953–1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Song Z, Li C, et al. 2018. RSM1, an Arabidopsis MYB protein, interacts with HY5/HYH to modulate seed germination and seedling development in response to abscisic acid and salinity. PLoS Genetics 14: e1007839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X, Li Y, Liu S, Xia F, Li X, Qi B.. 2014. Accumulation of eicosapolyenoic acids enhances sensitivity to abscisic acid and mitigates the effects of drought in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany 65: 1637–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Li G, Yi GX, et al. 2006. Comparison between conventional indirect competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (icELISA) and simplified icELISA for small molecules. Analytica Chimica Acta 571: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Zhang Z, Gao J, et al. 2018. Arabidopsis duodecuple mutant of PYL ABA receptors reveals PYL repression of ABA-independent SnRK2 activity. Cell Reports 23: 3340–3351.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK. 2011. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 53: 247–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK. 2016. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 167: 313–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.