Abstract

Reduced levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol correlate with increased risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases and HDL performs functions including reverse cholesterol transport, inhibition of lipid peroxidation, and suppression of inflammation, that would appear critical for cardioprotection. However, several large clinical trials utilizing pharmacologic interventions that elevated HDL cholesterol levels failed to provide cardioprotection to at-risk individuals. The reasons for these unexpected results have only recently begun to be elucidated. HDL cholesterol levels and HDL function can be significantly discordant, so that elevating HDL cholesterol levels may not necessarily lead to increased functional capacity, particularly under conditions that cause HDL to become oxidatively modified, resulting in HDL dysfunction. Here we review evidence that oxidative modifications of HDL, including by reactive lipid aldehydes generated by lipid peroxidation, reduce HDL functionality and that dicarbonyl scavengers that protect HDL against lipid aldehyde modification are beneficial in pre-clinical models of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: HDL, lipid aldehydes, isolevuglandins, malondialdehyde, apoA1, atherosclerosis

Overview

Plasma lipoproteins play a crucial role in whole body physiology as carriers of lipids, and disorders related to lipid and lipoprotein metabolism have life-threatening consequences. It is now well established that elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is a causative risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ASCVD). In contrast, whether reduced levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) or its major apolipoprotein, apoA1, have a causative role in ASCVD remains controversial. Reduced levels of HDL-C correlate with increased risk for ASCVD. Furthermore, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) performs functions including reverse cholesterol transport, inhibition of lipid peroxidation, and suppression of inflammation, that would appear critical for cardioprotection. However, several large clinical trials utilizing pharmacologic interventions that elevated HDL-C levels failed to provide cardioprotection to at-risk individuals. The reasons for these unexpected results have only recently begun to be elucidated. HDL-C levels and HDL function can be significantly discordant, so that elevating HDL-C levels may not increase HDL functional capacity, particularly under conditions that cause HDL to become oxidatively modified, resulting in HDL dysfunction. Here we review evidence that oxidative modifications of HDL, including by reactive lipid aldehydes generated by lipid peroxidation, reduce HDL functionality and that dicarbonyl scavengers that protect HDL against lipid aldehyde modification are beneficial in pre-clinical models of ASCVD.

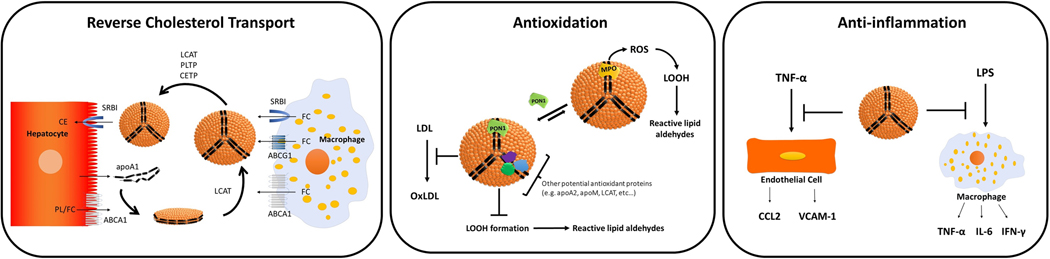

Potentially cardioprotective role of HDL

The Framingham Heart Study reported an inverse relationship between plasma HDL-C and the incidence of coronary heart disease [1] and numerous studies since then have confirmed this inverse correlation [2, 3]. In animal models of atherosclerosis, infusion of HDL [4, 5] or transgenic expression of apoA1 [6, 7] decreases atherosclerotic lesion areas. Transfusion of apoA1 or reconstituted HDL into humans also conferred cardioprotection in clinical trials [8, 9]. At least three functions of HDL may contribute to its potential anti-atherosclerotic effects: its ability to facilitate reverse cholesterol transport, its ability to protect other lipoproteins from peroxidation (reviewed in [10]) and its ability to dampen inflammatory responses (reviewed in [11][12]) (Figure 2).

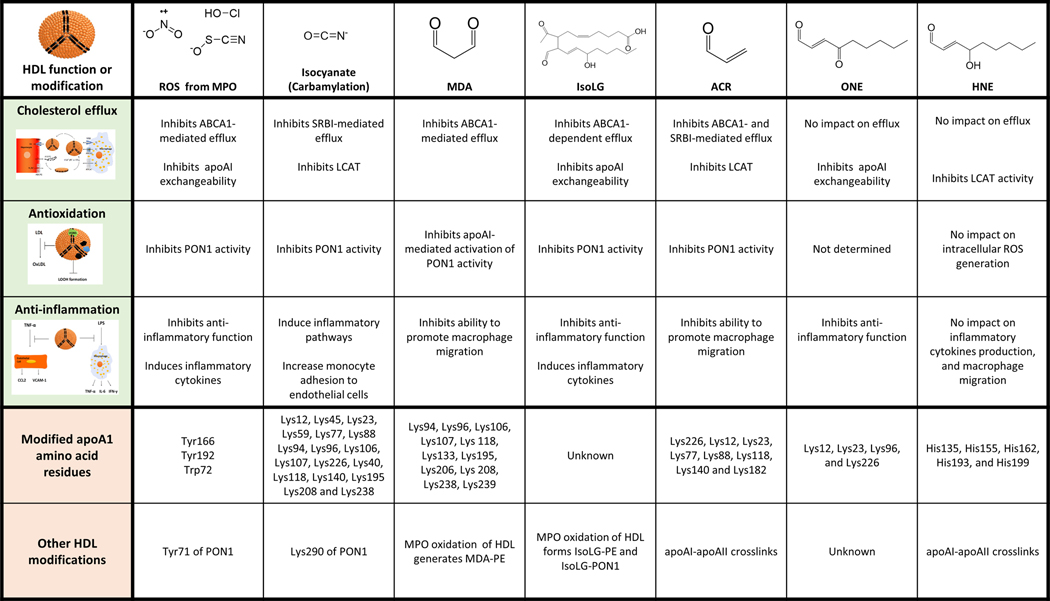

Figure 2.

Effects of oxidative modification on HDL function. Oxidative modifications of HDL include modification of amino acid residues by reactive oxygen species (ROS) formed by MPO, by isocyanate formed non-enzymatically by oxidation of urea, or by various reactive lipid aldehydes formed by lipid peroxidation. These lipid aldehydes include malondialdehyde (MDA), isolevuglandin (IsoLG), acrolein (ACR), 4-oxononenal (ONE), and 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE). The sites of apoA1 amino acid residue modification by each compound is shown as well as other known HDL protein modifications.

It is important to recognize that HDL is a collection of highly heterogenous lipoparticles. ApoA1 is the major protein constituent of HDL, comprising about 70% of its protein mass, and appears to play critical roles in all of three of the major HDL functions. ApoA1 serves as a scaffold for other proteins to associate with HDL and also interacts with cellular transporters that facilitate the transfer of lipids to and from HDL. More than 85 different proteins at least transiently associate with HDL including lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT), cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP), phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP), and paraoxonase-1 (PON-1) [13–15].

Reverse cholesterol transport.

The various forms of HDL (lipid-poor apoA1, HDL2, and HDL3) serve as acceptors for cholesterol from peripheral tissue to transport cholesterol from these cells to the liver for excretion or redistribution [16]. Reverse cholesterol transport begins when apoA1 secreted from the liver and intestine interacts with ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily A Member 1 (ABCA1) on cells such as macrophages to accept phospholipid and free cholesterol (Figure 2). LCAT associated with apoA1 then converts free cholesterol to cholesterol ester (CE), forming spherical HDL particles. Spherical HDLs accept additional free cholesterol via interaction with ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily G Member 1 (ABCG1) and Scavenger Receptor BI (SRBI) on donor cells. CETP and PLTP exchange cholesterol ester (CE) from HDL for triglyceride (TG) from LDL and VLDL. Finally, HDL interacts with SRBI on the surface of hepatocytes to deliver CE to the liver [16].

Effective reverse cholesterol transport requires HDL to penetrate the subendothelial space to interact with macrophages that have taken up cholesterol from a variety of sources including apoptotic cells. The small particle size of HDL (7.3–13 nm) compared to other lipoproteins like LDL (21.2–27 nm) and VLDL (27–200 nm) may be an important feature of HDL in this regard. Two mechanisms for transportation of HDL into subendothelial space have been reported: i) non-specific passive penetration through pores in the endothelial cell monolayer [17], and ii) active transcytosis through endothelial cells via active transport requiring ABCA1, ABCG1, SRBI, ecto-F1-ATPase, and caveolin-1 [18–20]. After collecting cholesterol and other toxic molecules from tissue, HDL enters the lymphatics to return to circulation and deliver cholesterol to the liver for metabolism and disposal. HDL facilitated cholesterol transport from peripheral tissues reduces cholesterol accumulation in the intima-media of arteries [21]. Measurements of whole body reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) capacity can be used to assess risk for development of ASCVD [22]. However, whole body RCT is too cumbersome for regular clinical use, so that surrogate measures such as measuring the capacity of HDL isolated from patients to facilitate the efflux of cholesterol from cholesterol-loaded macrophages are used instead. These ex vivo cholesterol efflux assays correlate well with whole body RCT [23] and the cholesterol efflux capacity of HDL inversely associates with ASCVD [24–26].

Antioxidation.

Oxidation of LDL phospholipids to form lipid peroxides (LOOH) and subsequent formation of lipid aldehydes that modify apoB (oxLDL) play critical roles in the development of atherosclerosis [27]. The evidence that HDL exerts potent antioxidative effects, especially to prevent oxidation of LDL, has been reviewed by Brites et al [10]. Isolated LDL is readily oxidized in vitro using copper, but coincubation with HDL or with PON1 largely inhibits to formation of LOOH or the breakdown of LOOH to reactive lipid aldehydes such as MDA under these conditions [28, 29]. Although PON1 is a relatively minor protein component of HDL, it appears to be essential for the antioxidative effects of HDL [10, 28, 30, 31]. PON1 competes with MPO for binding to apoA1 [32], which may protect HDL phospholipids from peroxidation, as MPO is a major source of reactive oxygen species that cause lipid peroxidation in circulation [33]. Other HDL proteins with potential antioxidant properties include apoA1, apoA2, apoA5, apoE, apoM, apoD, apoF, apoJ, apo L-1 and serum amyloid A [10]. HDL can also readily catalyze the transfer of CE peroxides and hydroxides from cells and from LDL [34–36], and cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) appears to be critical to this process [37], as does HDL phospholipid composition and the rigidity of HDL surface [31].

Anti-inflammation.

OxLDL is pro-inflammatory, so that HDL inhibition of LDL oxidation exerts an anti-inflammatory effect. However, HDL inhibition of inflammation extends to other stimuli besides oxLDL. HDL inhibits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced cytokine secretion, including reducing levels of tumor necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α), interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) and interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) [38]. HDL binding and neutralization of LPS only partially accounts for these effects [39]. HDL also inhibits induction of CCL2 by co-culture of endothelial and smooth muscle cells [41], inhibits endothelial cell expression of adhesion molecules in response to TNFα [42, 43], and suppresses the adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells [44]. Both apoA1 and HDL phospholipids appear to contribute to these various anti-inflammatory effects [45, 46]. Some of the anti-inflammatory effects require interaction of apoA1 with ABCA1 and cholesterol efflux [21, 40]. Of note, the cholesterol efflux mediated by HDL can drive both anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory effects, although the anti-inflammatory effects predominate [40, 47].

HDL function versus HDL cholesterol Levels in Cardioprotection

The apparent cardioprotective effects of HDL led to development of pharmacological interventions that increase HDL-C levels in individuals with low HDL-C levels. Both inhibition of CETP and administration of niacin raise HDL-C levels, but large scale clinical trials of these interventions found no beneficial effect [48–50], calling into question the role of HDL in cardioprotection [51–53].

The premise that pharmacologically increasing HDL-C levels in persons with low HDL-C levels enhances their HDL function may not be valid (reviewed in [54]). For instance, CETP drives the net transfer of unoxidized cholesterol esters from HDL to LDL but also drives the net transfer of oxidized cholesterol esters from LDL to HDL [36, 37]. Thus, CETP inhibition may raise HDL levels of unoxidized cholesterol ester at the cost of reducing hepatic degradation of oxidized cholesterol esters via HDL. CETP inhibition using torcetrapib also appears to decrease PON1 activity [55], a critical antioxidative function of HDL.

A large study including both healthy individuals and those with angiographically confirmed coronary artery disease examined correlates with carotid artery intima-media thickness. This study found that lower cholesterol efflux capacity strongly predicted coronary artery disease status, but that HDL-C and apoA1 levels account for less than 40% of the observed variation in measured cholesterol efflux capacity [26]. A second study followed individuals for a median time of 9.4 years after making initial measurements including HDL-C and cholesterol efflux capacity. This study again found a strong inverse relationship between cholesterol efflux capacity and coronary disease and poor correlation between efflux capacity and HDL-C levels [56].

Modifications of HDL alter its functional capacity.

Individuals with risk factors for ASCVD such as familial hypercholesterolemia, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes often have reduced HDL function that poorly correlates with changes in HDL-C levels [57–62] suggesting that under these conditions, HDL might undergo modificationsthat alter its functionality.

Such modifications could include changes in the protein and lipids content of HDL or covalent modifications of HDL proteins and phospholipids. A well-established example of the first type of modification is “acute-phase HDL”, where an infection or other inflammatory stimulus invokes wholesale changes in the proteins and lipid content of HDL. Notable changes in acute-phase HDL include reduction in apoA1 and marked increase in serum amyloid A; reduction in cholesterol esters with concomitant increases in free cholesterol, triglycerides, and free fatty acids; and reduced levels of CETP, LCAT, and PON1 with increased levels of secretory phospholipase A2 and LPS-binding protein (reviewed in [63] and [64]). The net effect of these changes is that acute-phase HDL has significantly altered function compared to normal HDL. Significant alterations in the HDL proteome, including enrichment in serum amyloid A, have been reported in patients with coronary artery disease and other chronic inflammatory conditions (reviewed in [14]).

We hypothesize that oxidative modification of HDL proteins and phospholipids also contributes to HDL dysfunction and evidence for this hypothesis will be the focus on the remainder of this review. In serum, the majority of cholesterol linoleate hydroperoxides [65], phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxides [66], and F2-isoprostanes [67] (stable end-products of arachidonic acid peroxidation) are associated with HDL rather than the other lipoproteins. Mechanisms driving HDL enrichment with LOOH likely include LCAT-facilitated transfer of oxidized acyl chains from phospholipids to free cholesterol to form oxidized cholesterol esters [68], CETP-facilitated transfer of oxidized lipids from LDL to HDL [36, 37], and binding of extracellular MPO to apoA1 [33, 69]. The capture of oxidized lipids and MPO by HDL likely facilitates their removal and protects the organism under conditions of low oxidative stress. However, pathophysiological conditions may overwhelm the antioxidative capacity of HDL, leading to its oxidative modification and loss of function.

Multiple mechanisms for Oxidative modification of HDL

In vitro oxidation of apoA1 or HDL using MPO results in oxidative modification and loss of function that markedly resembles that seen in apoA1 or HDL extracted from atherosclerotic lesions [69–74], consistent with MPO being a major driver of HDL oxidative modification in vivo. After activation by hydrogen peroxide, MPO can utilize substrates including chloride (Cl-), bromide (Br-), thiocyanate (SCN-), and nitrite ions (NO2-) to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hypochlorous acid (HOCl), hypobromous acid (HOBr), hypothiocyanous acid (HOSCN), isocyanate (CNO-), and nitrogen dioxide radical (●NO2) [75]. Other ROS, such as superoxide (O2●-), the hydroxyl radical (OH●) and peroxynitrite (ONOO-), can be generated by other enzymes including NADPH oxidases and xanthine oxidase. These ROS can directly oxidize amino acids including cysteine (Cys), methionine (Met), tyrosine (Tyr), tryptophan (Trp), or lysine (Lys) to generate modified amino acids including disulfide bonds (Cys-Cys crosslinks), oxidized Met (oxMet), oxidized Trp (oxTrp), 3-chlorotyrosine (3-Cl-Tyr), nitrotyrosine (NO2-Tyr), and tyrosine dimers (Tyr-Tyr), N-chloroamines, and carbamyl-Lys.

In addition to directly oxidatively modifying HDL amino acids, ROS also indirectly modify HDL proteins by generating lipid peroxides (LOOH) that fragment into reactive lipid aldehydes. ●NO2 is particularly adept at the peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids [76, 77], as is ONOO- [78]. LOOH undergoes secondary reactions to form reactive lipid aldehydes including malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxy-nonenal (HNE), 4-oxo-nonenal (ONE), isolevuglandins (IsoLG), acrolein (ACR), and methylglyoxal (MGO) (Figure 2). These reactive lipid aldehydes then modify amino acids including Lys, Cys, histidine (His), or arginine (Arg) (reviewed in [79]). MDA and IsoLG target primary amines including Lys and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), while HNE preferentially targets cysteine (Cys) and histidine (His), then arginine (Arg), Lys, and PE. ONE shows similar preferences as HNE, except that ONE modifies Lys and PE to a greater extent. ACR preferentially modifies Cys, but also modifies Lys, PE, and to a lesser extent His. MGO preferentially modifies Arg.

Implicating oxidative modification of HDL as a key contributor to HDL dysfunction and ASCVD requires the following evidence: i) demonstration that oxidative modification of HDL occurs in vivo; ii) demonstration that in vitro oxidation or direct modification of HDL by lipid aldehydes causes loss of HDL function; iii) demonstration that selective elimination of amino acid oxidation (e.g. by substitution of oxidation-resistant amino acids for oxidation-prone amino acids) or aldehyde modification (e.g. by using aldehyde scavengers that block modification) protects HDL function under conditions that normally result in loss of function; and iv) that restoration of HDL function in this manner decreases disease. We examine the current state of such evidence below.

HDL is oxidatively modified in vivo.

A substantial body of evidence demonstrates that amino acids of HDL proteins undergo oxidative modification of HDL during atherosclerosis. Approximately 20% of apoA1 isolated from atherosclerotic lesion includes oxTrp72, and oxTrp72 levels correlate with increased cardiovascular disease risk [80]. Zheng et al found apoA1 3-Cl-Tyr levels to be about 2.5-fold higher in CVD patients compared to controls, and apoA1 NO2-Tyr levels to be 1.5-fold higher [70]. Bergt et al also found that HDL 3-Cl-Tyr levels are higher in patients with coronary artery disease than in control individuals, and that HDL isolated from atherosclerotic lesions had higher 3-Cl-Tyr levels compared to HDL isolated from serum [81]. Similarly, HDL NO2-Tyr is higher in HDL isolated from atherosclerotic lesions than HDL isolated from serum or plasma [70, 81, 82]. The carbamyl-Lys content of HDL isolated from the atherosclerotic lesion correlates with its 3-Cl-Tyr content and with lesion severity [83]. In apoA1 isolated from human aortic atheroma, 16 of the 21 Lys residues show some amount of carbamylation [84]. This pattern is consistent with the carbamylation reaction primarily occurring with lipid-poor apoA1 rather than HDL and with the isocyanate for the carbamylation reaction being formed non-enzymatically from urea rather than enzymatically by MPO from thiocyanate [84].

In individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), a strong risk factor for early onset CAD, levels of HDL IsoLG-protein adducts, HDL IsoLG-PE adducts, MDA-apoAI adducts, and HDL ONE-protein adducts are elevated from two to five-fold in plasma compared to that of control individuals [85–87]. When HDL was isolated from patients with coronary artery disease, those with acute coronary syndrome showed 40% higher levels of MDA adducts than those with stable angina [88]. In patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy, arterial lesion HDL levels of MDA were 3.6-fold higher than plasma HDL levels of MDA [89]. Individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have elevated risk for atherosclerosis and HDL HNE-adducts are increased in CKD patients compared to controls [90]. Immunohistochemistry showed colocalization of ACR adducts and apoAI in atherosclerotic lesions [91], but to the best of our knowledge, increased levels of ACR-apoAI or ACR-HDL in patients with ASCVD or at risk for ASCVD have not been reported.

Does oxidative modification of HDL correlate with reduced HDL function?

In vitro oxidation of isolated HDL, especially when HDL is oxidized enzymatically using MPO, leads to reductions in HDL function including impairments in cholesterol efflux, anti-apoptotic effects, anti-peroxidation effects, and anti-inflammatory effects [32, 69–74, 92]. Modification of apoA1 or isolated HDL with reactive lipid aldehydes typically shows similar effects as MPO oxidation.

Reduced Cholesterol efflux.

In vitro modification of HDL with MPO reduces its capacity to facilitate ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux from macrophages [70, 91]. Early studies demonstrated that both MPO/H2O2/Cl- and MPO/H2O2/NO2- mediated oxidation of apoA1 led to Tyr modification, with Tyr192 being the primary Tyr modified [91]. Of interest, only 3-Cl-Tyr192 modification and not NO2-Tyr192 modification correlated with reduced cholesterol efflux [91]. Oxidation of HDL with peroxynitrite (ONOO-) had no significant effect on cholesterol efflux despite resulting in significant apoA1 nitration of Tyr [70, 91]. Subsequent studies showed that mutation of apoA1 Tyr residues to oxidation-resistant phenylalanine (Phe) residues did not protect apoA1 from the reductions in ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux capacity induced by MPO/H2O2/Cl- [93], suggesting that 3-Cl-Tyr may simply serve as a surrogate indicator for other oxidative modifications. Follow-up studies showed that MPO/H2O2/Cl- oxidation of HDL also results in Trp72 oxidation, and mutation of Trp72 to Phe protected apoA1 from MPO-mediated reduction in its ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux capacity [80]. Carbamylation of HDL causes cholesterol to accumulate in macrophages as lipid droplets by increasing SR-BI dependent uptake, but carbamylation of HDL does not alter ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux from cholesterol loaded macrophages [83].

Reactive lipid aldehydes can also cause loss of efflux capacity by HDL. Modification of apoA1 with 0.3- and 3-molar equivalents of IsoLG per apoAI molecule reduces cholesterol efflux from cholesterol loaded macrophages by about 20% and 30%, respectively [87]. Modification of HDL with 5- to 50-molar equivalent MDA reduces efflux from 13% to 75% respectively [89]. Modification of apoA1 with 20- or 50-molar equivalent ACR reduced efflux about 25% and 50%, respectively [94, 95]. In contrast, incubation of apoA1/HDL with various concentrations of HNE, ONE, MGO, or glyoxal has no effect on cholesterol efflux [62, 89].

Why IsoLG, MDA, and ACR modification of apoA1 inhibits cholesterol efflux, while apoA1 modification with other lipid aldehydes like HNE, ONE, and MGO do not, remains unclear. Simply crosslinking apoA1 appears insufficient to reduce cholesterol efflux, as ONE, HNE, and MGO can also crosslink apoA1 when sufficient concentrations are used. The two most C-terminal alpha helices of apoA1, Helix 9 (residues 209–219) and helix 10 (residues 220–243), are critical for its interaction with ABCA1 [96–98] and these two helices include three Lys (Lys226, Lys238, Lys239), one Arg (Arg215) but no His residues residues that could be targets for aldehyde modification. Of note, the loss of cholesterol efflux with ACR modification was directly proportionate to the extent of Lys226 ACR modification [94]. Modifying apoA1 with 20 mol equivalents of MDA leads to extensive crosslinking of Lys226 to Lys206 and to Lys182 [89], and of Lys239 to Lys208 and Lys182, while also forming MDA monoadducts on Lys118, Lys133, and Lys195 [89]. The specific Lys residues of apoA1 modified by IsoLG have not yet been reported. While incubation of HNE with apoA1 modifies all five His residues, no modification of Lys were detected [87, 89]. Incubation of MGO with apoA1 leads to extensive Arg modification but not Lys modification [89]. These results suggest that the extent of apoA1 Lys modification, especially Lys226 modification, may be a key determinant of altered cholesterol efflux capacity. However, ONE modifies Lys226 (as well as Lys12, Lys23, and Lys96), yet fails to inhibit cholesterol efflux [62]. Furthermore, carbamylation of apoA1 in vitro results in extensive Lys226 modification, along with modification of Lys23, Lys40, Lys94, and Lys 118 [84], but carbamylation of apoA1 does not result in altered cholesterol efflux [83]. Thus, the mechanisms underlying reduced efflux after apoA1 modification with specific lipid aldehydes, and the extent to which amino acid oxidation and aldehyde modification interact to reduce cholesterol efflux needs further elucidation.

Reduced antioxidation.

Although HDL (and especially HDL-associated PON1) protects LDL from in vitro oxidation by copper or free radical initiators, early studies showed that HDL-associated PON1 begins to lose its activity as oxidation continued. This inhibitory effect can be recapitulated by addition of peroxidized lipid preparations to PON1 [99].

In vitro oxidation of HDL with MPO/H2O2/NO2- or MPO/ H2O2/Cl- leads to a drop in PON1 activity, as well as oxidation of Tyr71 of PON1 to generate NO2-Tyr or 3-Cl-Tyr adducts, respectively [32]. These two events appear mechanistically related, as Tyr71 interacts with cholesterol within HDL to stabilize PON1 binding to HDL and substitution of Tyr71 with other amino acids such as alanine, aspartic acid, or Lys reduces PON1 activity [32]. In samples from individuals presenting for diagnostic coronary angiography and matched healthy controls, the levels of HDL 3-Cl-Tyr inversely correlated with PON1 activity, further supporting a causative role of Tyr71 modification in reducing PON1 activity in vivo [32].

Reactive lipid aldehydes may also contribute to PON1 inactivation. Treating HDL with the peroxynitrite generator SIN1 induces lipid peroxidation, as measured by the formation of PC with fragmented acyl chains with omega aldehyde moieties (“core aldehydes”), and causes a rapid drop in PON1 activity [100]. Direct addition of PC with core aldehydes only minimally inhibited PON1 activity [100], as would be expected given the poor reactivity of these simple aldehydes. Whether SIN1 treatment of HDL generates IsoLG or MDA adducts has not been determined but would be expected. Treatment of HDL with 5 mol equivalent of IsoLG (relative to apoA1) results in approximately 50% inhibition of HDL PON1 activity [101]. ApoA1 allosterically activates PON1 [101, 102], raising the possibility that IsoLG modification of apoA1 caused the reduced PON1 activity. However, IsoLG modified-HDL stimulates the activity of subsequently added recombinant PON1 to nearly the same extent as unmodified HDL does, suggesting that IsoLG-modification of apoA1 has minimal effect on apoA1 allosteric activation of PON1 [101]. In contrast, IsoLG modification of recombinant PON1 markedly inhibits its activity and treatment of HDL with MPO/H2O2/NO2- results in IsoLG modification of PON1 [101], suggesting that the reduced HDL PON1 activity after exposure to oxidants results at least in part from IsoLG modification of PON1. Treatment of HDL modified by 5 mol equivalents of MDA (relative to apoA1) results in approximately 50% inhibition of HDL-mediated activation of PON1 subsequently added to the HDL, suggesting that MDA indirectly inhibits PON1 by blocking apoA1-mediated activation [85]. Whether MDA can also inhibit PON1 by direct modification of its Lys was not determined. Treatment of HDL with ACR results in dose dependent inhibition of HDL PON1 activity [103]. Whether this inhibition of PON1 activity results from ACR directly modifying PON1 or modifying apoA1 to prevent its allosteric activation of PON1 is unknown. These same investigators showed that in individuals with end-stage renal disease, hemodialysis treatment decreased plasma ACR levels and increased PON1 activity [103], suggesting that ACR (and other reactive lipid aldehydes removed by hemodialysis) play an important role in determining PON1 activity rates in vivo [103]. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have looked at whether levels of reactive lipid aldehyde adducts detected for HDL proteins or PON1 are inversely correlated to activity of the sample. Such studies would be important validation of a causal role for lipid aldehyde modification of HDL in reducing PON1 activity.

Reduced suppression of inflammation and pro-inflammatory effects.

Oxidation of HDL with MPO/H2O2/Cl- not only blocks the ability of HDL to inhibit TNFα stimulated VCAM-1 surface expression by endothelial cells, but actually further potentiates this response [69]. MPO-oxidized HDL can stimulate NFκB activation and VCAM-1 surface expression on its own, even in the absence of TNFα, while non-oxidized HDL has no such effect [69]. Mutation of various Trp, Tyr, and Met residues of apoA1 to oxidation resistant residues (Phe and Val) do not protect apoA1 from MPO-mediated conversion to its proinflammatory form, suggesting that oxidation of these amino acids does not play a role in this conversion [69].

While native HDL suppresses LPS-induced secretion of Tnfα and Il-1β, HDL modified by 1 molar equivalent IsoLG not only fails to suppress LPS-induced inflammatory cytokine secretion, but in fact significantly potentiates LPS-induced IL-1β secretion [87], suggesting that IsoLG-HDL could play a similar role in driving inflammation as oxidized LDL. ONE modification of HDL also ablates the ability of HDL to suppress LPS-induced Tnfα, IL-1β, and IL-6 production, but ONE-HDL does not further potentiate LPS-induced cytokine secretion [62]. Modification of HDL by ACR, MDA, or HNE did not alter its ability to suppress LPS-induced macrophage inflammatory cytokine secretion [104].

One component of IsoLG-HDL, IsoLG modified phosphatidylethanolamine (IsoLG-PE), is able to directly stimulate TNFα secretion in a NFκB-dependent manner via activation of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) [86] and induces monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells [105]. Interestingly, IsoLG modifies PE to a greater extent than lysine [106], which may be why even low concentrations of IsoLG suffice to turn HDL into an inflammatory particle. PE modified in vitro with MDA, HNE, and ONE, but not with ACR or MGO also induces monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells [105]; however, whether such PE adducts form when HDL is exposed to these aldehydes or to oxidants has not yet been investigated.

Oxidized LDL promotes the trapping of macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions by inhibiting macrophage migration from the plaque [107]. HDL normally promotes macrophage migration in vitro, but HDL modified with ACR or MDA fails to promote migration [104]. HNE modification has no effect. Whether IsoLG-modified HDL alters macrophage migration is untested.

In vivo correlations between oxidative modification and HDL function.

As noted previously, individuals with ASCVD or with strong risk factors for ASCVD have reduced HDL function [57–62]. Although increased HDL oxidative modification and reduced HDL function both correlate with increased cardiovascular diseases, whether the extent of HDL oxidative modification in a sample inversely correlates with HDL functional capacity measured in the same sample needs further elucidation. Zheng et al showed strong inverse relationships between ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux and apoA1 3-Cl-Tyr levels or apoA1 NO2-Tyr levels in a small group of patients from a U.S. cardiology clinic [70]. However, Wang et al found that increased levels of HDL 3-Cl-Tyr and HDL NO2-Tyr did not correlate with reduced efflux capacity in individuals with coronary artery disease in a small Chinese cohort [108]. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies that have examined correlations between the extent of apoA1 or HDL modification by MDA, ACR, or IsoLG and cholesterol efflux capacity or other HDL functions in patient samples. Therefore, studies examining the relationships between various oxidative modifications and HDL function in large cohorts of relevant individuals are urgently needed to resolve these questions.

aldehyde scavengers represent an alternative approach To inhibit oxidative modification and provide cardioprotection

Validating a causal role for lipid aldehyde modification of HDL in development of cardiovascular disease requires demonstrating that selectively eliminating these modifications rescues HDL function and prevents or reverses disease. While dietary antioxidants can be used to reduce the formation of lipid aldehydes, the pharmacological doses of dietary antioxidants needed for even modest reductions in aldehyde levels have pluripotent effects including interfering with critical cell signaling pathways and blocking formation of other non-reactive lipid products, making it difficult to interpret outcomes. A more relevant approach uses small molecule nucleophiles serving as sacrificial targets for reactive lipid aldehydes, thereby sparing proteins and PE from aldehyde modification. A number of such reactive lipid aldehyde scavengers have been developed and show potential for treatment of cardiovascular disease.

α,β-unsaturated aldehydes such as HNE and ACR can be scavenged by thiol-based scavengers such as 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate (MESNA), amifostine, glutathione, and taurine or by imidazole-based scavengers such as carnosine (reviewed in [109]). MESNA is used as an adjunctive treatment for chemotherapy [110–112], and experimentally for ulcerative colitis [113, 114] and liver injury [115]. Carnosine, but not MESNA, also effectively scavenges MGO and carnosine has shown utility in treatment of diabetes [116, 117], atherosclerosis [118, 119], heart failure [120, 121], and ischemic brain damage[122, 123].

MESNA and carnosine are not effective for scavenging aldehydes that preferentially target primary amines like IsoLG. Furthermore, the extreme reactivity of IsoLG (>50% reaction of free aldehyde to form protein adduct in 20 sec compared to > 60 min required for 50% reaction of HNE to form protein adduct [124]) represented a significant challenge for identifying compounds with sufficient reactivity to prevent protein adduction by IsoLG. Fortunately, the screening of a series of bioavailable primary amines led to the identification of 2-aminomethylphenols (2-AMPs) as highly effective IsoLG scavengers [125, 126].

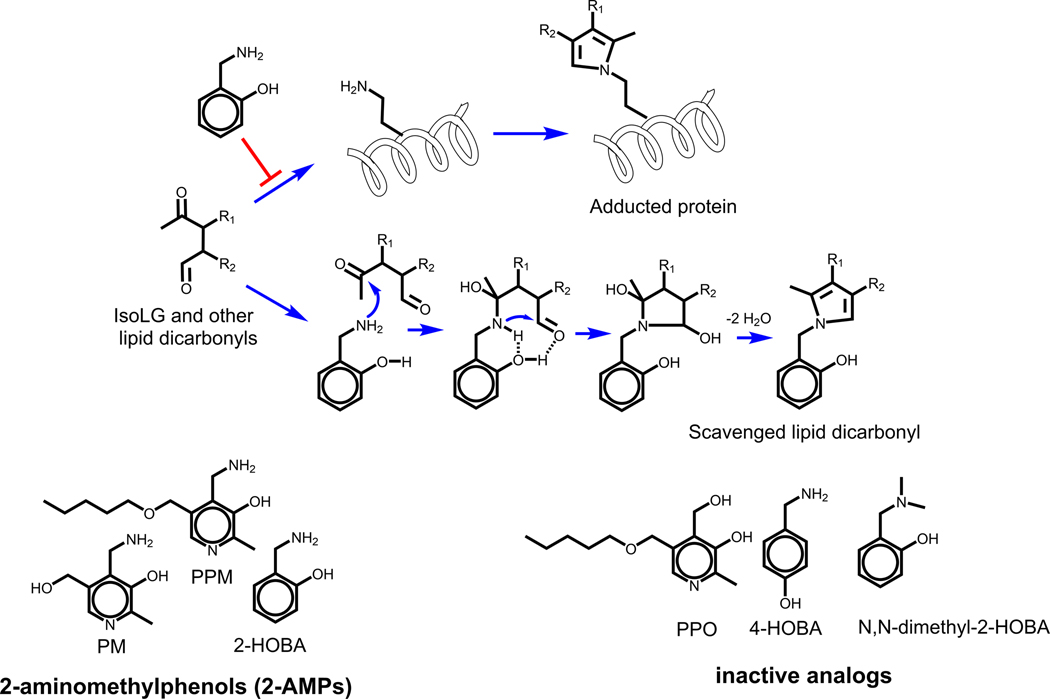

Mechanistically, the enhanced reactivity of 2-AMPs is due to the phenolic group stabilizing the initial formation of the imine adduct on the methylamine moiety, catalyzing the formation of the stable pyrrole adduct [125] (Figure 3). This leads to a >1000-fold faster reaction of IsoLG with 2-AMPs than the reaction of IsoLG with Lys [125]. In cellular assays, the more hydrophobic 2-AMP analogs such as 2-hydroxylbenzylamine (2-HOBA) and pentylpyridoxamine (PPM) show far greater ability to block the formation of IsoLG adducts than hydrophilic 2-AMP analogs such as pyridoxamine (PM) [126], presumably due to their greater hydrophobicity allowing them to penetrate into cellular membranes where IsoLG are generated [127]. 2-HOBA, PPM, and other 2-AMPs are also highly effective at scavenging other lipid dicarbonyls such as ONE and MDA [128]), but do not effectively scavenge α,β-unsaturated alkenals such as HNE that lack a second carbonyl moiety [125]. 2-HOBA and PPM reduce levels of lipid dicarbonyl protein adducts in a variety of cellular assays where oxidative stress is implicated and also inhibit key adverse effects [129–137]. Several compounds closely related to 2-AMPs only poorly react with IsoLGs including regioisomers of 2-AMPs such as 4-hydroxybenzylamine (4-HOBA), substituted amine analogs such as N,N-dimethyl-2-HOBA, or analogs where a hydroxyl group replaces the amine such as pentylpyridoxine (PPO) (Figure 3). Since these compounds are ineffective scavengers, they can be used as control compounds [138].

Figure 3.

2-aminomethylphenols (2-AMPs) including 2-hydroxybenzylamine (2-HOBA), pentylpyridoxamine (PPM) or pyridoxamine (PM) react with IsoLG or other lipid dicarbonyls to scavenge these dicarbonyls and thus blocking the modification of proteins by these lipid dicarbonyls. The high rate of reactivity of 2-AMPs is the result of their phenolic hydrogen helping to stabilize the initial imine adduct through hydrogen bonding and thereby helping to catalyze pyrrole formation. Inactive analogs of 2-AMP cannot participate in the same reaction and so can be used a control compounds for cellular and in vivo studies.

2-AMPs effectively protect HDL from oxidative modification and provide cardioprotection.

As previously noted, incubation of isolated HDL with MPO generates IsoLG-protein adducts, ONE-protein adducts, and MDA-protein adducts [85, 87, 101, 105]. Preincubation of isolated HDL with PPM blocks MPO-mediated IsoLG-protein adduct formation [87]. Pre-incubation of HDL with PPM also blocks the ability of IsoLG to alter HDL function when added to isolated HDL including blocking IsoLG-induced crosslinking of apoA1, IsoLG-induced inhibition of cholesterol efflux, and IsoLG-induced loss of HDL-mediated LPS-induced cytokine secretion [87]. Preincubation of isolated HDL with PPM (and to a somewhat lesser extent with 2-HOBA, fluoro-2-HOBA, or chloro-2-HOBA) blocks crosslinking of apoA1 when ONE is incubated with HDL [62]. Preincubation of HDL with PPM (but not PPO) prior to incubation with ONE blocks the loss of HDL-mediated inhibition of LPS-induced cytokine secretion normally induced by ONE [62]. Preincubation of HDL with either PPM or 2-HOBA blocked MDA-mediated crosslinking [85].

Both 2-HOBA and PPM are orally bioavailable and can be administered to rodents in drinking water [85, 127]. Administration of 2-HOBA to female Ldlr−/− mice fed a high-cholesterol diet markedly reduces total aorta atherosclerotic lesion area, reduces the necrotic area of lesions, and enhances macrophage efferocytosis, without significantly altering either total plasma cholesterol or triglyceride levels [139]). Consistent with its mechanism of action being lipid dicarbonyl scavenging, 2-HOBA treatment reduced MDA- and IsoLG-protein adduct levels in the lesions and IsoLG and MDA adducts of 2-HOBA were detected in various tissues of 2-HOBA treated mice [139]. HDL isolated from 2-HOBA treated mice showed reduced MDA levels compared to HDL isolated from mice treated with vehicle or 4-HOBA (other lipid dicarbonyl adducts were not measured due to limited sample size) and this isolated HDL showed increased ex vivo cholesterol efflux capacity compared to vehicle or 4-HOBA treated mice [139]. 2-HOBA treatment also increased HDL PON1 activity [85]. Similar to 2-HOBA, administration of PPM to Ldlr−/− mice also reduced HDL dicarbonyl adducts and enhanced the ex vivo cholesterol efflux capacity and PON1 activity of HDL isolated from PPM-treated mice [85].

The anti-atherosclerotic effects of dicarbonyl scavenger treatment are unlikely to be due exclusively to their effects on HDL function, as scavengers also reduce levels of LDL adducts [85, 139]. Furthermore, treatment with either 2-HOBA or PPM markedly reduces hypertension (a major contributor to cardiovascular disease) in several rodent models [132, 133]. The anti-hypertensive effects of dicarbonyl scavengers are primarily attributed to their ability to block the formation of dicarbonyl modified neo-antigens presented by dendritic cells and recognized by cytotoxic T cell [132]. Given this evidence, the remarkable anti-atherosclerotic effects of 2-HOBA and PPM most likely result from multiple beneficial effects of reducing lipid dicarbonyl adducts, including the enhancement of HDL function seen with this treatment.

Conclusions and future directions

The failure of clinical trials with dietary antioxidants and with HDL-C raising drugs research initially appeared to foreclose any significant role for oxidative modification of lipoproteins in the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and for HDL in protecting against disease. However, recent studies suggest a different conclusion. Because dietary antioxidants have little impact on the extent of LOOH formation and oxidative modification in vivo and because raising HDL-C levels do not necessarily improve HDL functionality in at risk individuals, these previous clinical studies do not preclude oxidative modifications of apoAI and other HDL components making significant contributions to development of ASCVD. In vitro studies clearly demonstrate the potential for oxidative modifications of HDL to markedly alter HDL functionality, either by oxidation of amino acid residues such as tyrosine and tryptophan or by lipid aldehyde modification of nucleophilic amino acids such as lysine. That various studies have found increased levels of oxidized HDL amino acids and HDL lipid aldehyde modification in diseased individuals support a causative role in disease. However, whether the extent of oxidative modification is sufficient to drive loss of function and is in fact causal remains to be demonstrated convincingly. In this regard, the early mouse studies with the 2-AMP class of lipid dicarbonyl scavengers such as 2-HOBA and PPM that showed both enhanced HDL functionality and reduced atherosclerosis are highly promising. Even so, additional studies are needed to determine whether these effects are the result of protecting HDL from oxidative modifications, rather than blocking modifications at other sites such as LDL. Furthermore, given that successful treatments in animal models of disease often fail to translate to improved human outcomes, whether oxidative modifications of HDL significantly contribute to development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in humans will remain an open question until dicarbonyl scavengers show success in clinical trials.

Figure 1.

Major anti-atherosclerotic functions of HDL. HDL has a critical role in reverse cholesterol transport, as HDL acquires free cholesterol (FC) from macrophages and other cells in peripheral tissues, esterifies FC to cholesterol esters, and then transports cholesterol esters to the liver for excretion by hepatocytes. Antioxidative effects of HDL include inhibiting the oxidation of LDL and the formation of lipid peroxides (LOOH). PON1 plays a major role in HDL’s antioxidative effect both through its catalytic activity and by competing with MPO for binding to apoA1. Other proteins associated with HDL have also been shown to exert antioxidative effects. HDL exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects including suppression of cytokine secretion by endothelial cells and macrophages in response to inflammatory stimuli.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health P01 HL116263-06A1.

References

- [1].Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR, High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study, The American journal of medicine 62(5) (1977) 707–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wilson PW, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Kannel WB, Prevalence of coronary heart disease in the Framingham Offspring Study: role of lipoprotein cholesterols, The American journal of cardiology 46(4) (1980) 649–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Assmann G, Gotto AM, HDL Cholesterol and Protective Factors in Atherosclerosis, Circulation 109(23_suppl_1) (2004) III-8-III–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Badimon JJ, Badimon L, Galvez A, Dische R, Fuster V, High density lipoprotein plasma fractions inhibit aortic fatty streaks in cholesterol-fed rabbits, Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 60(3) (1989) 455–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Badimon JJ, Badimon L, Fuster V, Regression of atherosclerotic lesions by high density lipoprotein plasma fraction in the cholesterol-fed rabbit, The Journal of clinical investigation 85(4) (1990) 1234–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rubin EM, Krauss RM, Spangler EA, Verstuyft JG, Clift SM, Inhibition of early atherogenesis in transgenic mice by human apolipoprotein AI, Nature 353(6341) (1991) 265–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Plump AS, Scott CJ, Breslow JL, Human apolipoprotein A-I gene expression increases high density lipoprotein and suppresses atherosclerosis in the apolipoprotein E-deficient mouse, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91(20) (1994) 9607–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nissen SE, Tsunoda T, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, Cooper CJ, Yasin M, Eaton GM, Lauer MA, Sheldon WS, Grines CL, Halpern S, Crowe T, Blankenship JC, Kerensky R, Effect of recombinant ApoA-I Milano on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial, Jama 290(17) (2003) 2292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tardif JC, Grégoire J, L’Allier PL, Ibrahim R, Lespérance J, Heinonen TM, Kouz S, Berry C, Basser R, Lavoie MA, Guertin MC, Rodés-Cabau J, Effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein infusions on coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial, Jama 297(15) (2007) 1675–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brites F, Martin M, Guillas I, Kontush A, Antioxidative activity of high-density lipoprotein (HDL): Mechanistic insights into potential clinical benefit, BBA Clinical 8 (2017) 66–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ansell BJ, Navab M, Watson KE, Fonarow GC, Fogelman AM, Anti-Inflammatory Properties of HDL, Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders 5(4) (2004) 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Namiri-Kalantari R, Gao F, Chattopadhyay A, Wheeler AA, Navab KD, Farias-Eisner R, Reddy ST, The dual nature of HDL: Anti-Inflammatory and pro-Inflammatory, 41(3) (2015) 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ronsein GE, Vaisar T, Deepening our understanding of HDL proteome, Expert review of proteomics 16(9) (2019) 749–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shah AS, Tan L, Long JL, Davidson WS, Proteomic diversity of high density lipoproteins: our emerging understanding of its importance in lipid transport and beyond1, Journal of lipid research 54(10) (2013) 2575–2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Davidson WS, Shah AS, Sexmith H, Gordon SM, The HDL Proteome Watch: Compilation of studies leads to new insights on HDL function, Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular and cell biology of lipids 1867(2) (2022) 159072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Navab M, Reddy ST, Van Lenten BJ, Fogelman AM, HDL and cardiovascular disease: atherogenic and atheroprotective mechanisms, Nature Reviews Cardiology 8(4) (2011) 222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Stender S, Zilversmit DB, Transfer of plasma lipoprotein components and of plasma proteins into aortas of cholesterol-fed rabbits. Molecular size as a determinant of plasma lipoprotein influx, Arteriosclerosis: An Official Journal of the American Heart Association, Inc. 1(1) (1981) 38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].von Eckardstein A, Rohrer L, Transendothelial lipoprotein transport and regulation of endothelial permeability and integrity by lipoproteins, Current opinion in lipidology 20(3) (2009) 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fruhwürth S, Pavelka M, Bittman R, Kovacs WJ, Walter KM, Röhrl C, Stangl H, High-density lipoprotein endocytosis in endothelial cells, World J Biol Chem 4(4) (2013) 131–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Simionescu M, Popov D, Sima A, Endothelial transcytosis in health and disease, Cell Tissue Res 335(1) (2009) 27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yvan-Charvet L, Wang N, Tall AR, Role of HDL, ABCA1, and ABCG1 transporters in cholesterol efflux and immune responses, Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 30(2) (2010) 139–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Turner S, Voogt J, Davidson M, Glass A, Killion S, Decaris J, Mohammed H, Minehira K, Boban D, Murphy E, Luchoomun J, Awada M, Neese R, Hellerstein M, Measurement of reverse cholesterol transport pathways in humans: in vivo rates of free cholesterol efflux, esterification, and excretion, Journal of the American Heart Association 1(4) (2012) e001826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rohatgi A, High-Density Lipoprotein Function Measurement in Human Studies: Focus on Cholesterol Efflux Capacity, Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 58(1) (2015) 32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kosmas CE, Martinez I, Sourlas A, Bouza KV, Campos FN, Torres V, Montan PD, Guzman E, High-density lipoprotein (HDL) functionality and its relevance to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Drugs Context 7 (2018) 212525-212525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Saleheen D, Scott R, Javad S, Zhao W, Rodrigues A, Picataggi A, Lukmanova D, Mucksavage ML, Luben R, Billheimer J, Kastelein JJ, Boekholdt SM, Khaw KT, Wareham N, Rader DJ, Association of HDL cholesterol efflux capacity with incident coronary heart disease events: a prospective case-control study, The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology 3(7) (2015) 507–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Khera AV, Cuchel M, de la Llera-Moya M, Rodrigues A, Burke MF, Jafri K, French BC, Phillips JA, Mucksavage ML, Wilensky RL, Mohler ER, Rothblat GH, Rader DJ, Cholesterol efflux capacity, high-density lipoprotein function, and atherosclerosis, The New England journal of medicine 364(2) (2011) 127–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Poznyak AV, Nikiforov NG, Markin AM, Kashirskikh DA, Myasoedova VA, Gerasimova EV, Orekhov AN, Overview of OxLDL and Its Impact on Cardiovascular Health: Focus on Atherosclerosis, 11 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mackness MI, Arrol S, Durrington PN, Paraoxonase prevents accumulation of lipoperoxides in low-density lipoprotein, FEBS Letters 286(1) (1991) 152–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yoshikawa M, Sakuma N, Hibino T, Sato T, Fujinami T, HDL3 exerts more powerful anti-oxidative, protective effects against copper-catalyzed LDL oxidation than HDL2, Clinical biochemistry 30(3) (1997) 221–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mackness MI, Arrol S, Abbott C, Durrington PN, Protection of low-density lipoprotein against oxidative modification by high-density lipoprotein associated paraoxonase, Atherosclerosis 104(1–2) (1993) 129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Soran H, Schofield JD, Durrington PN, Antioxidant properties of HDL, Front Pharmacol 6 (2015) 222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Huang Y, Wu Z, Riwanto M, Gao S, Levison BS, Gu X, Fu X, Wagner MA, Besler C, Gerstenecker G, Zhang R, Li XM, DiDonato AJ, Gogonea V, Tang WH, Smith JD, Plow EF, Fox PL, Shih DM, Lusis AJ, Fisher EA, DiDonato JA, Landmesser U, Hazen SL, Myeloperoxidase, paraoxonase-1, and HDL form a functional ternary complex, The Journal of clinical investigation 123(9) (2013) 3815–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhang R, Shen Z, Nauseef WM, Hazen SL, Defects in leukocyte-mediated initiation of lipid peroxidation in plasma as studied in myeloperoxidase-deficient subjects: systematic identification of multiple endogenous diffusible substrates for myeloperoxidase in plasma, Blood 99(5) (2002) 1802-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ferretti G, Bacchetti T, Moroni C, Vignini A, Curatola G, Copper-induced oxidative damage on astrocytes: protective effect exerted by human high density lipoproteins, Biochimica et biophysica acta 1635(1) (2003) 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Klimov AN, Kozhevnikova KA, Kuzmin AA, Kuznetsov AS, Belova EV, On the ability of high density lipoproteins to remove phospholipid peroxidation products from erythrocyte membranes, Biochemistry. Biokhimiia 66(3) (2001) 300–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Castilho LN, Oliveira HC, Cazita PM, de Oliveira AC, Sesso A, Quintão EC, Oxidation of LDL enhances the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP)-mediated cholesteryl ester transfer rate to HDL, bringing on a diminished net transfer of cholesteryl ester from HDL to oxidized LDL, Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry 304(1–2) (2001) 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Christison JK, Rye KA, Stocker R, Exchange of oxidized cholesteryl linoleate between LDL and HDL mediated by cholesteryl ester transfer protein, Journal of lipid research 36(9) (1995) 2017–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Guo L, Ai J, Zheng Z, Howatt DA, Daugherty A, Huang B, Li XA, High density lipoprotein protects against polymicrobe-induced sepsis in mice, The Journal of biological chemistry 288(25) (2013) 17947–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Murch O, Collin M, Hinds CJ, Thiemermann C, Lipoproteins in inflammation and sepsis. I. Basic science, Intensive Care Medicine 33(1) (2007) 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Fotakis P, Kothari V, Thomas DG, Westerterp M, Molusky MM, Altin E, Abramowicz S, Wang N, He Y, Heinecke JW, Bornfeldt KE, Tall AR, Anti-Inflammatory Effects of HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein) in Macrophages Predominate Over Proinflammatory Effects in Atherosclerotic Plaques, Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 39(12) (2019) e253–e272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tölle M, Pawlak A, Schuchardt M, Kawamura A, Tietge UJ, Lorkowski S, Keul P, Assmann G, Chun J, Levkau B, Giet M.v.d., Nofer J-R, HDL-Associated Lysosphingolipids Inhibit NAD(P)H Oxidase-Dependent Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Production, 28(8) (2008) 1542–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ashby DT, Rye KA, Clay MA, Vadas MA, Gamble JR, Barter PJ, Factors influencing the ability of HDL to inhibit expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in endothelial cells, Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 18(9) (1998) 1450–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Barter PJ, Baker PW, Rye KA, Effect of high-density lipoproteins on the expression of adhesion molecules in endothelial cells, Current opinion in lipidology 13(3) (2002) 285–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Baker PW, Rye KA, Gamble JR, Vadas MA, Barter PJ, Ability of reconstituted high density lipoproteins to inhibit cytokine-induced expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, Journal of lipid research 40(2) (1999) 345–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tang C, Liu Y, Kessler PS, Vaughan AM, Oram JF, The macrophage cholesterol exporter ABCA1 functions as an anti-inflammatory receptor, The Journal of biological chemistry 284(47) (2009) 32336–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Vuilleumier N, Dayer JM, von Eckardstein A, Roux-Lombard P, Pro- or anti-inflammatory role of apolipoprotein A-1 in high-density lipoproteins?, Swiss Med Wkly 143 (2013) w13781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kothari V, He Y, Kramer F, Barnhart S, Kanter JE, Tang J, Frey JM, Vaisar T, Heinecke JW, Bornfeldt KE, Small HDL, diabetes, and proinflammatory effects in macrophages, The FASEB Journal 33(S1) (2019) 238.3–238.3. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJ, Komajda M, Lopez-Sendon J, Mosca L, Tardif JC, Waters DD, Shear CL, Revkin JH, Buhr KA, Fisher MR, Tall AR, Brewer B, Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events, The New England journal of medicine 357(21) (2007) 2109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, Chaitman BR, Desvignes-Nickens P, Koprowicz K, McBride R, Teo K, Weintraub W, Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy, The New England journal of medicine 365(24) (2011) 2255–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Nissen SE, Tardif JC, Nicholls SJ, Revkin JH, Shear CL, Duggan WT, Ruzyllo W, Bachinsky WB, Lasala GP, Tuzcu EM, Effect of torcetrapib on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis, The New England journal of medicine 356(13) (2007) 1304–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kingwell BA, Chapman MJ, Kontush A, Miller NE , HDL-targeted therapies: progress, failures and future, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 13(6) (2014) 445–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Vergeer M, Holleboom AG, Kastelein JJP, Kuivenhoven JA, The HDL hypothesis: does high-density lipoprotein protect from atherosclerosis?, Journal of lipid research 51(8) (2010) 2058–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ala-Korpela M, Kuusisto S, Holmes MV, Commentary: Big data bring big controversies: HDL cholesterol and mortality, International Journal of Epidemiology 50(3) (2021) 913–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ronsein GE, Heinecke JW, Time to ditch HDL-C as a measure of HDL function?, Current opinion in lipidology 28(5) (2017) 414–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Gugliucci A, Activation of paraoxonase 1 is associated with HDL remodeling ex vivo, Clinica Chimica Acta 429 (2014) 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Rohatgi A, Khera A, Berry JD, Givens EG, Ayers CR, Wedin KE, Neeland IJ, Yuhanna IS, Rader DR, de Lemos JA, Shaul PW, HDL Cholesterol Efflux Capacity and Incident Cardiovascular Events, New England Journal of Medicine 371(25) (2014) 2383–2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Maeba R, Kojima KI, Nagura M, Komori A, Nishimukai M, Okazaki T, Uchida S, Association of cholesterol efflux capacity with plasmalogen levels of high-density lipoprotein: A cross-sectional study in chronic kidney disease patients, Atherosclerosis 270 (2018) 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Gipson GT, Carbone S, Wang J, Dixon DL, Jovin IS, Carl DE, Gehr TW, Ghosh S, Impaired Delivery of Cholesterol Effluxed From Macrophages to Hepatocytes by Serum From CKD Patients May Underlie Increased Cardiovascular Disease Risk, Kidney international reports 5(2) (2020) 199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Yubero-Serrano EM, Alcalá-Diaz JF, Gutierrez-Mariscal FM, Arenas-de Larriva AP, Peña-Orihuela PJ, Blanco-Rojo R, Martinez-Botas J, Torres-Peña JD, Perez-Martinez P, Ordovas JM, Delgado-Lista J, Gómez-Coronado D, Lopez-Miranda J, Association between cholesterol efflux capacity and peripheral artery disease in coronary heart disease patients with and without type 2 diabetes: from the CORDIOPREV study, Cardiovascular Diabetology 20(1) (2021) 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Anderson JLC, Gautier T, Nijstad N, Tölle M, Schuchardt M, van der Giet M, Tietge UJF, High density lipoprotein (HDL) particles from end-stage renal disease patients are defective in promoting reverse cholesterol transport, Sci Rep 7(1) (2017) 41481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].He Y, Ronsein GE, Tang C, Jarvik GP, Davidson WS, Kothari V, Song HD, Segrest JP, Bornfeldt KE, Heinecke JW, Diabetes Impairs Cellular Cholesterol Efflux From ABCA1 to Small HDL Particles, Circulation research 127(9) (2020) 1198–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].May-Zhang LS, Yermalitsky V, Melchior JT, Morris J, Tallman KA, Borja MS, Pleasent T, Amarnath V, Song W, Yancey PG, Davidson WS, Linton MF, Davies SS, Modified sites and functional consequences of 4-oxo-2-nonenal adducts in HDL that are elevated in familial hypercholesterolemia, The Journal of biological chemistry 294(50) (2019) 19022–19033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Khovidhunkit W, Kim M-S, Memon RA, Shigenaga JK, Moser AH, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C, Thematic review series: The Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Effects of infection and inflammation on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism mechanisms and consequences to the host1, Journal of lipid research 45(7) (2004) 1169–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Jahangiri A, High-density lipoprotein and the acute phase response, Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity 17(2) (2010) 156–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Bowry VW, Stanley KK, Stocker R, High density lipoprotein is the major carrier of lipid hydroperoxides in human blood plasma from fasting donors, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 89(21) (1992) 10316–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Nagashima T, Oikawa S, Hirayama Y, Tokita Y, Sekikawa A, Ishigaki Y, Yamada R, Miyazawa T, Increase of serum phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxide dependent on glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients, Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 56(1) (2002) 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Proudfoot JM, Barden AE, Loke WM, Croft KD, Puddey IB, Mori TA, HDL is the major lipoprotein carrier of plasma F2-isoprostanes, Journal of lipid research 50(4) (2009) 716–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Goyal J, Wang K, Liu M, Subbaiah PV, Novel function of lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase. Hydrolysis of oxidized polar phospholipids generated during lipoprotein oxidation, The Journal of biological chemistry 272(26) (1997) 16231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Undurti A, Huang Y, Lupica JA, Smith JD, DiDonato JA, Hazen SL, Modification of high density lipoprotein by myeloperoxidase generates a pro-inflammatory particle, The Journal of biological chemistry 284(45) (2009) 30825–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Zheng L, Nukuna B, Brennan ML, Sun M, Goormastic M, Settle M, Schmitt D, Fu X, Thomson L, Fox PL, Ischiropoulos H, Smith JD, Kinter M, Hazen SL, Apolipoprotein A-I is a selective target for myeloperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation and functional impairment in subjects with cardiovascular disease, The Journal of clinical investigation 114(4) (2004) 529–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Wu Z, Wagner MA, Zheng L, Parks JS, Shy JM 3rd, Smith JD, Gogonea V, Hazen SL, The refined structure of nascent HDL reveals a key functional domain for particle maturation and dysfunction, Nature structural & molecular biology 14(9) (2007) 861–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Peng DQ, Brubaker G, Wu Z, Zheng L, Willard B, Kinter M, Hazen SL, Smith JD, Apolipoprotein A-I tryptophan substitution leads to resistance to myeloperoxidase-mediated loss of function, Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 28(11) (2008) 2063–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Hadfield KA, Pattison DI, Brown BE, Hou L, Rye KA, Davies MJ, Hawkins CL, Myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants modify apolipoprotein A-I and generate dysfunctional high-density lipoproteins: comparison of hypothiocyanous acid (HOSCN) with hypochlorous acid (HOCl), The Biochemical journal 449(2) (2013) 531–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Shao B, Oda MN, Oram JF, Heinecke JW, Myeloperoxidase: an oxidative pathway for generating dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein, Chemical research in toxicology 23(3) (2010) 447–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Davies MJ, Hawkins CL, The Role of Myeloperoxidase in Biomolecule Modification, Chronic Inflammation, and Disease, Antioxidants & redox signaling 32(13) (2020) 957–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Byun J, Mueller DM, Fabjan JS, Heinecke JW, Nitrogen dioxide radical generated by the myeloperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide-nitrite system promotes lipid peroxidation of low density lipoprotein, FEBS Lett 455(3) (1999) 243–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Schmitt D, Shen Z, Zhang R, Colles SM, Wu W, Salomon RG, Chen Y, Chisolm GM, Hazen SL, Leukocytes Utilize Myeloperoxidase-Generated Nitrating Intermediates as Physiological Catalysts for the Generation of Biologically Active Oxidized Lipids and Sterols in Serum, Biochemistry 38(51) (1999) 16904–16915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Radi R, Beckman JS, Bush KM, Freeman BA, Peroxynitrite-induced membrane lipid peroxidation: the cytotoxic potential of superoxide and nitric oxide, Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 288(2) (1991) 481–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Davies SS, May-Zhang LS, Boutaud O, Amarnath V, Kirabo A, Harrison DG, Isolevuglandins as mediators of disease and the development of dicarbonyl scavengers as pharmaceutical interventions, Pharmacology & Therapeutics 205 (2020) 107418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Huang Y, DiDonato JA, Levison BS, Schmitt D, Li L, Wu Y, Buffa J, Kim T, Gerstenecker GS, Gu X, Kadiyala CS, Wang Z, Culley MK, Hazen JE, Didonato AJ, Fu X, Berisha SZ, Peng D, Nguyen TT, Liang S, Chuang CC, Cho L, Plow EF, Fox PL, Gogonea V, Tang WH, Parks JS, Fisher EA, Smith JD, Hazen SL, An abundant dysfunctional apolipoprotein A1 in human atheroma, Nature medicine 20(2) (2014) 193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Bergt C, Pennathur S, Fu X, Byun J, O’Brien K, McDonald TO, Singh P, Anantharamaiah GM, Chait A, Brunzell J, Geary RL, Oram JF, Heinecke JW, The myeloperoxidase product hypochlorous acid oxidizes HDL in the human artery wall and impairs ABCA1-dependent cholesterol transport, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101(35) (2004) 13032–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Pennathur S, Bergt C, Shao B, Byun J, Kassim SY, Singh P, Green PS, McDonald TO, Brunzell J, Chait A, Oram JF, O’Brien K, Geary RL, Heinecke JW, Human atherosclerotic intima and blood of patients with established coronary artery disease contain high density lipoprotein damaged by reactive nitrogen species, The Journal of biological chemistry 279(41) (2004) 42977–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Holzer M, Gauster M, Pfeifer T, Wadsack C, Fauler G, Stiegler P, Koefeler H, Beubler E, Schuligoi R, Heinemann A, Marsche G, Protein carbamylation renders high-density lipoprotein dysfunctional, Antioxidants & redox signaling 14(12) (2011) 2337–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Battle S, Gogonea V, Willard B, Wang Z, Fu X, Huang Y, Graham LM, Cameron SJ, DiDonato JA, Crabb JW, Hazen SL, The pattern of apolipoprotein A-I lysine carbamylation reflects its lipidation state and the chemical environment within human atherosclerotic aorta, The Journal of biological chemistry 298(4) (2022) 101832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Huang J, Yancey PG, Tao H, Borja MS, Smith LE, Kon V, Davies SS, Linton MF, Reactive Dicarbonyl Scavenging Effectively Reduces MPO-Mediated Oxidation of HDL and Restores PON1 Activity, Nutrients 12(7) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Guo L, Chen Z, Amarnath V, Yancey PG, Van Lenten BJ, Savage JR, Fazio S, Linton MF, Davies SS, Isolevuglandin-type lipid aldehydes induce the inflammatory response of macrophages by modifying phosphatidylethanolamines and activating the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts, Antioxidants & redox signaling 22(18) (2015) 1633–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].May-Zhang LS, Yermalitsky V, Huang J, Pleasent T, Borja MS, Oda MN, Jerome WG, Yancey PG, Linton MF, Davies SS, Modification by isolevuglandins, highly reactive gamma-ketoaldehydes, deleteriously alters high-density lipoprotein structure and function, The Journal of biological chemistry 293(24) (2018) 9176–9187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Carnuta MG, Stancu CS, Toma L, Sanda GM, Niculescu LS, Deleanu M, Popescu AC, Popescu MR, Vlad A, Dimulescu DR, Simionescu M, Sima AV, Dysfunctional high-density lipoproteins have distinct composition, diminished anti-inflammatory potential and discriminate acute coronary syndrome from stable coronary artery disease patients, Sci Rep 7(1) (2017) 7295-7295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Shao B, Pennathur S, Pagani I, Oda MN, Witztum JL, Oram JF, Heinecke JW, Modifying apolipoprotein A-I by malondialdehyde, but not by an array of other reactive carbonyls, blocks cholesterol efflux by the ABCA1 pathway, The Journal of biological chemistry 285(24) (2010) 18473–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Florens N, Calzada C, Lemoine S, Boulet MM, Guillot N, Barba C, Roux J, Delolme F, Page A, Poux JM, Laville M, Moulin P, Soulère L, Guebre-Egziabher F, Juillard L, Soulage CO, CKD Increases Carbonylation of HDL and Is Associated with Impaired Antiaggregant Properties, Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 31(7) (2020) 1462–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Shao B, O’Brien K D, McDonald TO, Fu X, Oram JF, Uchida K, Heinecke JW, Acrolein modifies apolipoprotein A-I in the human artery wall, Ann N Y Acad Sci 1043 (2005) 396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Ferretti G, Bacchetti T, Nègre-Salvayre A, Salvayre R, Dousset N, Curatola G, Structural modifications of HDL and functional consequences, Atherosclerosis 184(1) (2006) 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Peng DQ, Wu Z, Brubaker G, Zheng L, Settle M, Gross E, Kinter M, Hazen SL, Smith JD, Tyrosine modification is not required for myeloperoxidase-induced loss of apolipoprotein A-I functional activities, The Journal of biological chemistry 280(40) (2005) 33775–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Shao B, Fu X, McDonald TO, Green PS, Uchida K, O’Brien KD, Oram JF, Heinecke JW, Acrolein Impairs ATP Binding Cassette Transporter A1-dependent Cholesterol Export from Cells through Site-specific Modification of Apolipoprotein A-I*, Journal of Biological Chemistry 280(43) (2005) 36386–36396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Chadwick AC, Holme RL, Chen Y, Thomas MJ, Sorci-Thomas MG, Silverstein RL, Pritchard KA Jr., Sahoo D, Acrolein impairs the cholesterol transport functions of high density lipoproteins, PLoS One 10(4) (2015) e0123138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Burgess JW, Frank PG, Franklin V, Liang P, McManus DC, Desforges M, Rassart E, Marcel YL, Deletion of the C-terminal domain of apolipoprotein A-I impairs cell surface binding and lipid efflux in macrophage, Biochemistry 38(44) (1999) 14524–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Natarajan P, Forte TM, Chu B, Phillips MC, Oram JF, Bielicki JK, Identification of an Apolipoprotein A-I Structural Element That Mediates Cellular Cholesterol Efflux and Stabilizes ATP Binding Cassette Transporter A1*, Journal of Biological Chemistry 279(23) (2004) 24044–24052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Vedhachalam C, Liu L, Nickel M, Dhanasekaran P, Anantharamaiah GM, Lund-Katz S, Rothblat GH, Phillips MC, Influence of ApoA-I Structure on the ABCA1-mediated Efflux of Cellular Lipids*, Journal of Biological Chemistry 279(48) (2004) 49931–49939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Aviram M, Rosenblat M, Billecke S, Erogul J, Sorenson R, Bisgaier CL, Newton RS, La Du B, Human serum paraoxonase (PON 1) is inactivated by oxidized low density lipoprotein and preserved by antioxidants, Free radical biology & medicine 26(7–8) (1999) 892–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Ahmed Z, Ravandi A, Maguire GF, Emili A, Draganov D, Du BNL, Kuksis A, Connelly PW, Apolipoprotein A-I Promotes the Formation of Phosphatidylcholine Core Aldehydes That Are Hydrolyzed by Paraoxonase (PON-1) during High Density Lipoprotein Oxidation with a Peroxynitrite Donor*, Journal of Biological Chemistry 276(27) (2001) 24473–24481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Aggarwal G, May-Zhang LS, Yermalitsky V, Dikalov S, Voynov MA, Amarnath V, Kon V, Linton MF, Vickers KC, Davies SS, Myeloperoxidase-induced modification of HDL by isolevuglandins inhibits paraoxonase-1 activity, The Journal of biological chemistry 297(3) (2021) 101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Gaidukov L, Tawfik DS, High affinity, stability, and lactonase activity of serum paraoxonase PON1 anchored on HDL with ApoA-I, Biochemistry 44(35) (2005) 11843–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Gugliucci A, Lunceford N, Kinugasa E, Ogata H, Schulze J, Kimura S, Acrolein inactivates paraoxonase 1: changes in free acrolein levels after hemodialysis correlate with increases in paraoxonase 1 activity in chronic renal failure patients, Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry 384(1–2) (2007) 105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Schill RL, Knaack DA, Powers HR, Chen Y, Yang M, Schill DJ, Silverstein RL, Sahoo D, Modification of HDL by reactive aldehydes alters select cardioprotective functions of HDL in macrophages, The FEBS journal 287(4) (2020) 695–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Guo L, Chen Z, Amarnath V, Davies SS, Identification of novel bioactive aldehyde-modified phosphatidylethanolamines formed by lipid peroxidation, Free radical biology & medicine 53(6) (2012) 1226–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Sullivan CB, Matafonova E, Roberts LJ, 2nd, V. Amarnath, S.S. Davies, Isoketals form cytotoxic phosphatidylethanolamine adducts in cells, Journal of lipid research 51(5) (2010) 999–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Park YM, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL, CD36 modulates migration of mouse and human macrophages in response to oxidized LDL and may contribute to macrophage trapping in the arterial intima, The Journal of clinical investigation 119(1) (2009) 136–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Wang G, Mathew AV, Yu H, Li L, He L, Gao W, Liu X, Guo Y, Byun J, Zhang J, Chen YE, Pennathur S, Myeloperoxidase mediated HDL oxidation and HDL proteome changes do not contribute to dysfunctional HDL in Chinese subjects with coronary artery disease, PLOS ONE 13(3) (2018) e0193782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Davies SS, Zhang LS, Reactive Carbonyl Species Scavengers-Novel Therapeutic Approaches for Chronic Diseases, Current pharmacology reports 3(2) (2017) 51–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Brock N, Pohl J, The development of mesna for regional detoxification, Cancer treatment reviews 10 Suppl A (1983) 33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Sakurai M, Saijo N, Shinkai T, Eguchi K, Sasaki Y, Tamura T, Sano T, Suemasu K, Jett JR, The protective effect of 2-mercapto-ethane sulfonate (MESNA) on hemorrhagic cystitis induced by high-dose ifosfamide treatment tested by a randomized crossover trial, Japanese journal of clinical oncology 16(2) (1986) 153–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Vose JM, Reed EC, Pippert GC, Anderson JR, Bierman PJ, Kessinger A, Spinolo J, Armitage JO, Mesna compared with continuous bladder irrigation as uroprotection during high-dose chemotherapy and transplantation: a randomized trial, Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 11(7) (1993) 1306–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Amirshahrokhi K, Khalili AR, Gastroprotective effect of 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate against acute gastric mucosal damage induced by ethanol, International immunopharmacology 34 (2016) 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Triantafyllidis I, Poutahidis T, Taitzoglou I, Kesisoglou I, Lazaridis C, Botsios D, Treatment with Mesna and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids ameliorates experimental ulcerative colitis in rats, International journal of experimental pathology 96(6) (2015) 433–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Arai T, Koyama R, Yuasa M, Kitamura D, Mizuta R, Acrolein, a highly toxic aldehyde generated under oxidative stress in vivo, aggravates the mouse liver damage after acetaminophen overdose, Biomedical research (Tokyo, Japan) 35(6) (2014) 389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Lee YT, Hsu CC, Lin MH, Liu KS, Yin MC, Histidine and carnosine delay diabetic deterioration in mice and protect human low density lipoprotein against oxidation and glycation, European journal of pharmacology 513(1–2) (2005) 145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Peters V, Riedl E, Braunagel M, Höger S, Hauske S, Pfister F, Zschocke J, Lanthaler B, Benck U, Hammes HP, Krämer BK, Schmitt CP, Yard BA, Köppel H, Carnosine treatment in combination with ACE inhibition in diabetic rats, Regulatory peptides 194-195 (2014) 36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Barski OA, Xie Z, Baba SP, Sithu SD, Agarwal A, Cai J, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava S, Dietary carnosine prevents early atherosclerotic lesion formation in apolipoprotein E-null mice, Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 33(6) (2013) 1162–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Menini S, Iacobini C, Ricci C, Scipioni A, Blasetti Fantauzzi C, Giaccari A, Salomone E, Canevotti R, Lapolla A, Orioli M, Aldini G, Pugliese G, D-Carnosine octylester attenuates atherosclerosis and renal disease in ApoE null mice fed a Western diet through reduction of carbonyl stress and inflammation, British journal of pharmacology 166(4) (2012) 1344–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Zieba R, Wagrowska-Danilewicz M, Influence of carnosine on the cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin in rabbits, Polish journal of pharmacology 55(6) (2003) 1079–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Lombardi C, Carubelli V, Lazzarini V, Vizzardi E, Bordonali T, Ciccarese C, Castrini AI, Dei Cas A, Nodari S, Metra M, Effects of oral administration of orodispersible levo-carnosine on quality of life and exercise performance in patients with chronic heart failure, Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 31(1) (2015) 72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Min J, Senut MC, Rajanikant K, Greenberg E, Bandagi R, Zemke D, Mousa A, Kassab M, Farooq MU, Gupta R, Majid A, Differential neuroprotective effects of carnosine, anserine, and N-acetyl carnosine against permanent focal ischemia, Journal of neuroscience research 86(13) (2008) 2984–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Zhang X, Song L, Cheng X, Yang Y, Luan B, Jia L, Xu F, Zhang Z, Carnosine pretreatment protects against hypoxia-ischemia brain damage in the neonatal rat model, European journal of pharmacology 667(1–3) (2011) 202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Brame CJ, Salomon RG, Morrow JD, Roberts LJ, 2nd, Identification of extremely reactive gamma-ketoaldehydes (isolevuglandins) as products of the isoprostane pathway and characterization of their lysyl protein adducts, The Journal of biological chemistry 274(19) (1999) 13139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Amarnath V, Amarnath K, Amarnath K, Davies S, Roberts LJ, 2nd, Pyridoxamine: an extremely potent scavenger of 1,4-dicarbonyls, Chemical research in toxicology 17(3) (2004) 410–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]