Abstract

Background

Dental procedures often produce aerosols and spatter, which have the potential to transmit pathogens such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. The existing literature is limited.

Methods

Aerosols and spatter were generated from an ultrasonic scaling procedure on a dental manikin and characterized via 2 optical imaging methods: digital inline holography and laser sheet imaging. Capture efficiencies of various aerosol mitigation devices were evaluated and compared.

Results

The ultrasonic scaling procedure generated a wide size range of aerosols (up to a few hundred μm) and occasional large spatter, which emit at low velocity (mostly < 3 m/s). Use of a saliva ejector and high-volume evacuator (HVE) resulted in overall reductions of 63% and 88%, respectively, whereas an extraoral local extractor (ELE) resulted in a reduction of 96% at the nominal design flow setting.

Conclusions

The study results showed that the use of ELE or HVE significantly reduced aerosol and spatter emission. The use of HVE generally requires an additional person to assist a dental hygienist, whereas an ELE can be operated hands free when a dental hygienist is performing ultrasonic scaling and other operations.

Practical Implications

An ELE aids in the reduction of aerosols and spatters during ultrasonic scaling procedures, potentially reducing transmission of oral or respiratory pathogens like severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Position and airflow of the device are important to effective aerosol mitigation.

Key Words: Aerosol-generating procedures, high-volume evacuation, extraoral local extractor, dental aerosols, ultrasonic scaling, spatter

Abbreviation Key: AGP, Aerosol-generating procedure; DIH, Digital inline holography; ELE, Extraoral local extractor; FOV, Field of view; HVAC, Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning; HVE, High-volume evacuation; LSI, Laser sheet imaging; PPE, Personal protection equipment; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SE, Saliva ejector

There is a general consensus that aerosols are one of the major paths of transmission for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in the COVID-19 pandemic.1 This has led to concerns for health care workers involved in procedures that generate aerosols.2, 3, 4, 5 Although we are unaware of any instances of dental aerosol transmission reported to this time, dental providers are thought to be at particular risk owing to the generation of aerosols and spatters6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 during dental procedures such as ultrasonic prophylaxis and high-speed, water-cooled tooth preparation. The dental profession has responded with increased use of personal protection equipment (PPE) and recommendations to avoid aerosol-generating procedures (AGP) such as ultrasonic scaling. Industry guidelines for addressing airborne risks focus on increased ventilation (or air changes per hour), portable room filtration systems (not at the source), avoidance of discretionary AGPs, and adding time between patients and procedures to allow for increased ventilation.7 , 8 , 12 These measures understandably have placed increased burden on the oral health care system and are based on limited data regarding the generation and mitigation of dental aerosols. Recommendations about mitigation of airborne contaminants in other occupational settings suggest that capture of contaminants near the source is far superior to general ventilation and use of PPE.13

There is a deficiency in the literature regarding the risks posed by aerosols and spatter from AGPs in dental settings and the efficacy of various aerosol-mitigation techniques. A number of studies have collected aerosols and spatters directly on a collecting surface for subsequent analysis, which includes fluorescent14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 or nonfluorescent20, 21, 22, 23 based chromatic indicators and microbiological methods using culture media.24, 25, 26, 27 These studies are limited by their inefficient collection of small-sized aerosols (< ≈ 50 μm), which do not provide a comprehensive characterization over the entire size spectrum. This is especially important as smaller aerosols (0.06-0.14 μm) may carry SARS-CoV-2.28 Some investigations have used aerosol sampling techniques,24 , 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 but they had a limited sampling of large aerosols and spatters or incorrectly used the sampling devices.

Dental procedures generate both aerosols and spatter. Without a commonly recognized size threshold, spatters are generally considered to be large droplets or debris that are heavy enough to settle rapidly without spreading a long distance. Aerosols, however, are small droplets that can become smaller through evaporation and result in smaller residual aerosols (≤ 10 μm) that may stay suspended in air indefinitely because they are sufficiently small enough to overcome gravitational settling, especially in a thermally stratified indoor environment.35, 36, 37 Although most of these residual aerosols are the result of the supplied cooling water, they can include a patient’ saliva, dental plaque, calculus, and blood, which can be infectious to dental practitioners or other dental patients if the patient carries SARS-CoV-2 or other infectious agents. Given that a droplet’s ability to spread and subsequently be inhaled depends on its original size and evaporation process, a comprehensive size characterization of the original droplets and the residual aerosols is essential in risk assessment of AGPs. Such a comprehensive assessment has not been reported yet to our best knowledge.

One example of a common dental hygiene procedure that has been avoided during the COVID-19 pandemic owing to concerns about aerosol generation is ultrasonic scaling for dental prophylaxis.4 This ultrasonic scaling technology increases the efficiency of dental hygienists and is less physically demanding than manual scaling. Dental hygienists are at risk of developing repetitive stress injuries, and the ban on ultrasonic scaling procedures makes these injuries more likely. The reduced efficiency of manual scaling also increases the time the patient is seated in the dental chair and, for some patients, may increase the number of appointments needed. High-volume evacuation (HVE) is reported to reduce aerosol contamination considerably,26 , 38 , 39 but it is generally not used by dental hygienists without having an assistant to hold, position, and manipulate the end of the HVE. Extraoral local extractors (ELEs) have been discussed and marketed since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, but evidence supporting their effectiveness is rare,40 , 41 and details about the proper design, configuration, and use of ELEs have not been studied and reported.

We conducted this study to provide detailed physical characterizations of aerosols and spatters from ultrasonic scaling processes using novel in situ optical methods. We further used the methods to evaluate the effectiveness of a variety of dental aerosol–mitigation devices.

Methods

We used digital inline holography (DIH) and laser sheet imaging (LSI) to gain a holistic insight into the generation and mitigation of aerosols and spatters from an ultrasonic scaling procedure. We used DIH to measure the size and speed of particles next to the aerosol-generating source, whereas the main purpose of LSI measurements was to visualize quantitatively particle movement and variation in concentration (from the amount of scattered light). Both of these techniques also provided an effective methodology for the evaluation of various aerosol-mitigation strategies and devices, with DIH being the primary method of assessment and LSI a supplemental one.

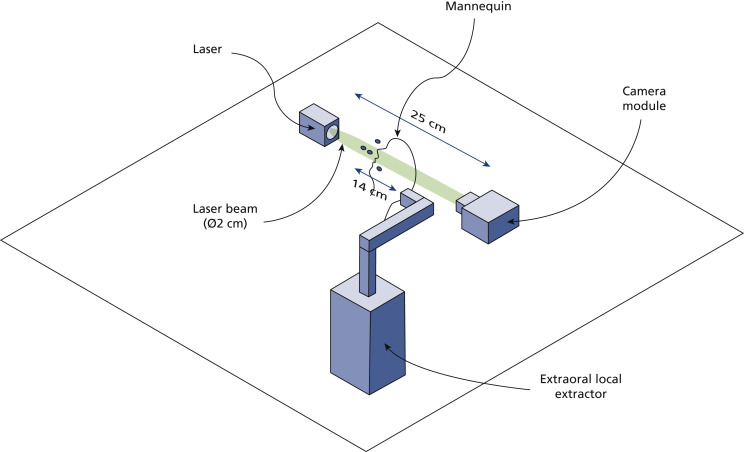

DIH

We conducted near-field in situ holographic measurements using a DIH setup consisting of a laser and a digital camera as well as beam-expanding, collimating, and condensing optics. We placed a dental manikin with thermoplastic teeth on a horizontal surface facing upward to mimic a patient during the dental procedure. The center of the DIH sample volume (15.6 × 13.0 × 250 mm3) was located approximately 8 mm above the manikin’s oral cavity (Figure 1 ). A more detailed description of the DIH setup can be found in Appendix 1, available online at the end of this article.

Figure 1.

Schematic of digital inline holography setup used for near-field aerosol size and velocity measurements. The digital inline holography system is mounted onto a cage system secured to a table (not shown) and incorporates beam-expanding, collimating, and condensing optics (also not shown). See Appendix 1.

We used the hybrid hologram processing method proposed by Shao and colleagues,42 consisting of image enhancement, digital reconstruction, particle segmentation, and postprocessing, to obtain the size distribution of particles passing through the DIH sample volume during simulated dental procedures. A sample data set of analyzed DIH results can be found in Appendix 2, available online at the end of this article.

Simulated ultrasonic scaling

A dental hygienist simulated supragingival scaling of the facial surfaces of the maxillary incisors and the lingual surfaces of the mandibular incisors using an ultrasonic scaler (Cavitron Plus with 30K FSI-1000 inserts; Dentsply Sirona) operating at the medium power setting and a median (standard deviation) water consumption rate of 36 (2) mm3/min while the holographic sensor (35 frames per s, 13-μs exposure) acquired 10-second videos for a total of 3 trials. Clinically, ultrasonic scaling in these dental regions generates the most spatters and aerosols.

Tested mitigation devices and strategies

We subsequently tested various mitigation devices, including a saliva ejector (SE), operated by the dental hygienist; an HVE, operated by a second person; and an ELE (DentalPro Aerosol UVC; BOFA International) at 2 different flow rates, 100 mm3/h (59 ft3/min) and 220 m3/h (129 ft3/m). We used different aerosol-mitigation devices, and combinations thereof, during the simulated procedure. For the mitigation measurements, we used the SE and HVE adjacent to the operating field as is typical of clinical practice. We tested the ELE nozzle at 2 distances from the mouth of the manikin, 14 cm and 18 cm. We determined that the 14-cm distance was the most effective nozzle placement on the basis of the recommendations of dental hygienists who collaborated with the manufacturer of the tested ELE through informal clinical testing. We investigated the 18-cm distance to further assess the impact of ELE nozzle position on aerosol mitigation.

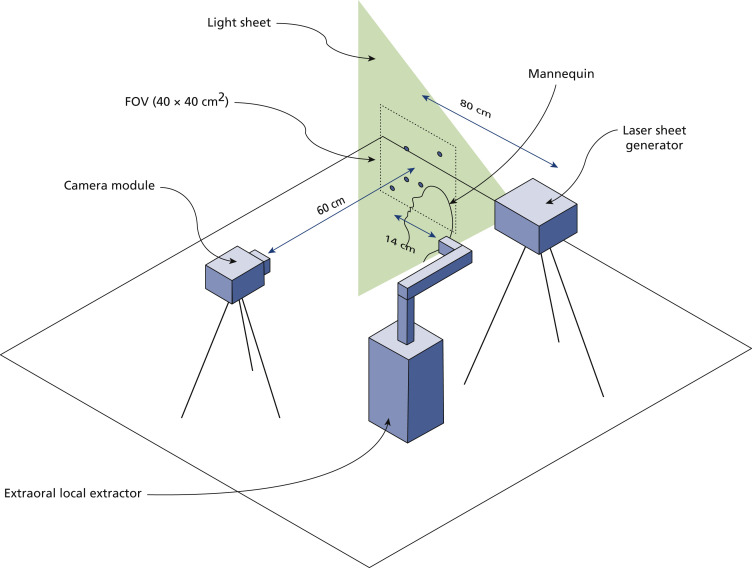

LSI

We conducted far-field in situ LSI using the setup illustrated in Figure 2 , which comprised a high-resolution camera coupled with an image intensifier, an imaging lens, and a light sheet–generating system. We placed the dental manikin on a horizontal surface facing upward in a fashion similar to the previous setup. We placed the light sheet generating system 80 cm to the side of the center of the camera’s field of view (FOV) and used it to generate a light sheet that crossed the manikin’s head just above the oral cavity and below the nose. Aerosol generation in dental procedures is a heterogenous process influenced by the placement and positioning of the dental tool across the oral cavity and the spatial distribution of sprays is likely to occur on the axis of propagation.43 Therefore, we chose this measurement plane to ensure maximum interaction between the laser illumination and the aerosol generated during the procedure and demonstrate a worst-case scenario in terms of disease transmission and infection risk. We oriented the camera module, located 60 cm from the manikin, perpendicularly to the light sheet and focused it to achieve an FOV of 40 × 40 cm2. We obtained additional measures to ensure the signal to noise ratio was maximized, such as spray-painting the manikin head and implementing a light trap to diminish background reflection. More details of the LSI setup can be found in Appendix 3, available online at the end of this article.

Figure 2.

Schematic of laser sheet imaging setup used for far-field plume and spatter measurements. The camera module incorporates a camera sensor, image intensifier, and imaging lens, and the laser sheet generator is composed of a high-power laser and a set of optical lenses. See Appendix 3. FOV: Field of view.

We converted recorded images to gray scale and enhanced them using background subtraction. We segmented the plume of aerosol generated during the procedure using an entropy filter, and we measured the total pixel intensity from light scattered by the aerosol plume and spatter and compared it with the mitigation-free test trial to obtain the device’s capture efficiency.

We tested the ultrasonic scaling simulation and the mitigation techniques with LSI in the same manner described with DIH. This provided a complementary broader FOV for the generated droplets and aerosols as well as their mitigation.

Results

DIH

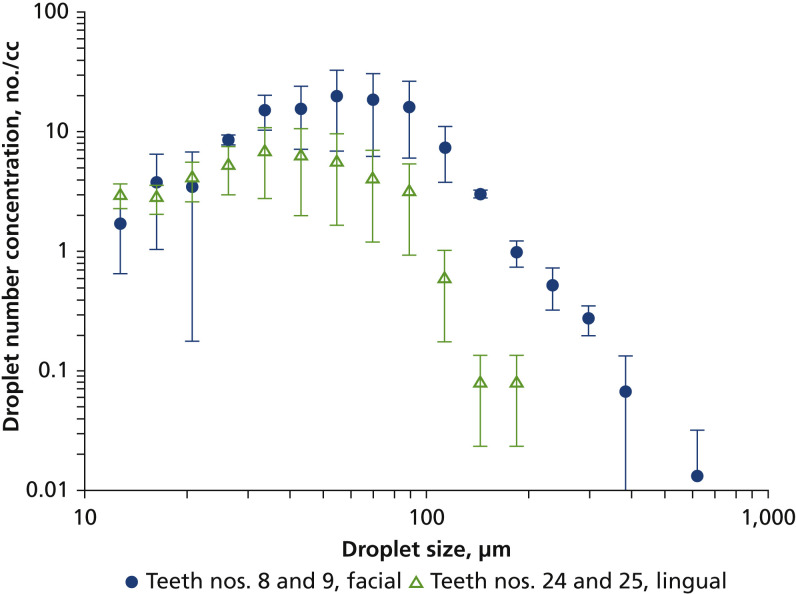

Droplet Size Distribution

The observed droplet generation of the ultrasonic scaler was dynamic, consisting of a relatively continuous generation of a plume of small droplets (aerosols) with occasional large spatters shooting out at high speed. Like with many other liquid films broken up by mechanical forces, we observed a wide range of droplet sizes with DIH, with more than 99% ranging from 12 through 200 μm (Figure 3 ). Spatters greater than 200 μm were much less prevalent and were highly dependent on the positioning and movement of the ultrasonic scaler tip on teeth. The number mode (size with the highest number concentration) of the size distributions were 55 μm when working on the facial surfaces of teeth nos. 8 and 9 and 34 μm for the lingual surfaces of teeth nos. 24 and 25. Total droplet concentration was 114 particles per cm3 for teeth nos. 8 and 9 and 42 particles per cm3 for teeth nos. 24 and 25. The lower concentration for teeth nos. 24 and 25 was due to the more confined space trapping droplets inside the mouth of the manikin. The concentration difference between the 2 sites was more pronounced for larger droplets.

Figure 3.

Size distribution of droplets as measured via digital inline holography. Error bars represent standard deviations of 3 measurements.

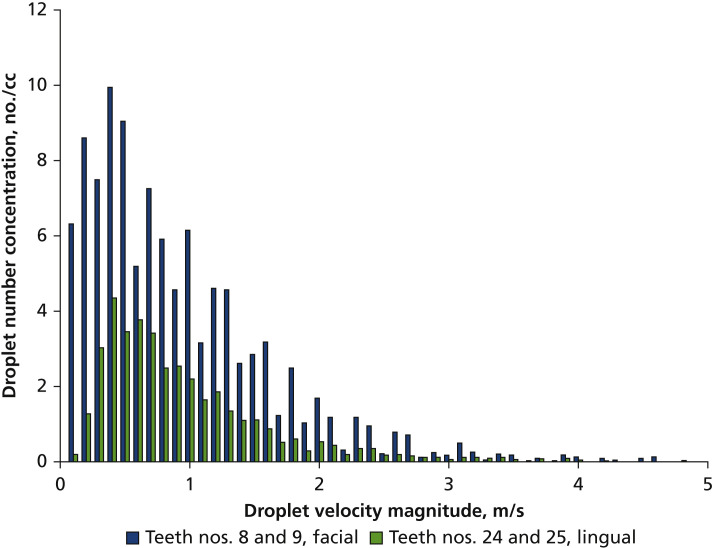

Droplet Velocity

More than 65% of the droplets had a velocity of less than 1 m/s, and less than 2% of the droplets had a velocity greater than 3 m/s (Figure 4 ). The low average droplet velocity observed here suggests that a suction-based point-of-source mitigation strategy is possible and may be more effective than mitigation based on whole-room ventilation. A 3-dimensional mapping of the velocity profile (not shown) suggested there was no dominant direction of droplet travel. As such, we chose particle size as the basis to evaluate the capture efficiency of the different mitigation strategies.

Figure 4.

The velocity distribution of droplets as measured via digital inline holography.

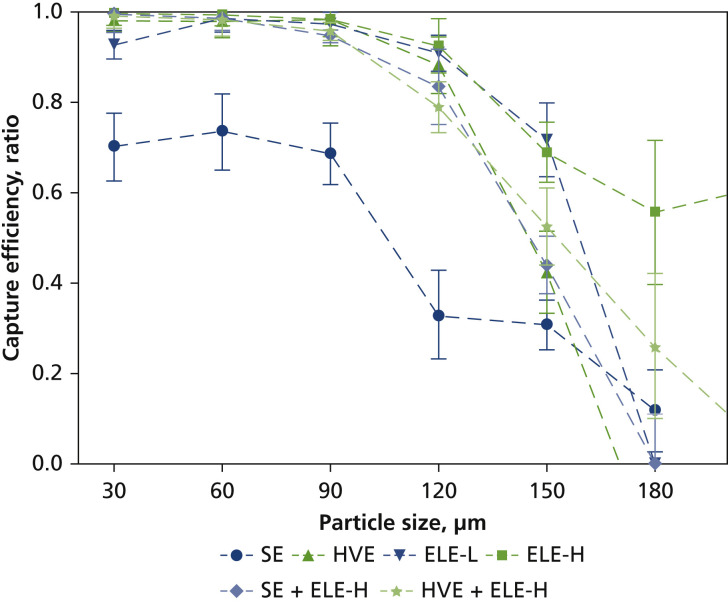

Capture Efficiency of Mitigation Devices

The capture efficiency of various mitigation devices is presented in Figure 5 . We determined the size-dependent capture efficiency by means of comparing the measured droplet size distribution with the mitigation device or devices applied with that measured when no mitigation was applied. The error bars shown represent the standard deviation of the efficiency calculated based on error propagation as a standard engineering approach. There was a clear trend of decreased capture efficiency with increased droplet size. For the particular FOV of the DIH in this experiment, all mitigation devices but SE showed greater than 95% of capture for droplets up to 90 μm. The capture efficiency dropped to approximately 80% and approximately 50% at 120 and 150 μm, respectively. The previously described irregular generation of large spatters made a statistically meaningful quantification of capture efficiency impossible at droplet size greater than 180 μm. As previously discussed, droplets and aerosols smaller than 150 μm are the focus of any mitigation strategies given their high potential for longer-distance travel and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and other airborne infectious agents.

Figure 5.

Size-dependent capture efficiency of various mitigation devices via digital inline holography when cleaning facial surface of teeth nos. 8 and 9. Error bars represent standard deviations of 3 measurements. ELE-H: Extraoral local extractor at high-flow setting. ELE-L: Extraoral local extractor at low-flow setting. HVE: High-volume evacuation. SE: Saliva ejector.

LSI

LSI provided a larger field assessment of the tested mitigation strategies with more comprehensive visualization of their effect on aerosol and spatter spread. A sample video clip of LSI is provided in Appendix 4 (available online at the end of this article), in which an ELE was off first, turned on for approximately 10 seconds, and then turned off again to show its effectiveness. When no mitigation device was used, the plume (mainly clusters of small droplets at low speed) showed a swirling movement representing the vortexing flow generated by an ultrasonic scaler tip moving at high frequency. Larger spatters were generated occasionally (larger and brighter dots in the video), shooting out at higher speed. When the ELE was turned on, the amount of light scattered by both the plume and the distinct spatters were significantly suppressed, with a clear sign of the plume being drawn toward the opening of the extractor. Occasional spatters were still observed, consistent with the size-dependent capture observed via DIH in which droplets with large momentum (larger size or higher speed) have a relatively higher chance to escape from the capture of a mitigation device.

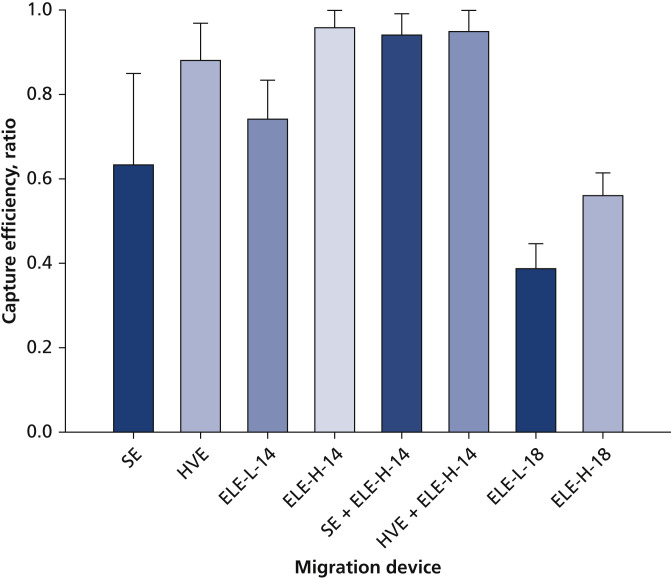

Without distinguishing individual particles and their sizes, we obtained an overall capture efficiency from LSI data for each mitigation device (or their combinations) as shown in Figure 6 by comparing the amount of scattered light with a test case in which no mitigation device was used. Among SE, HVE, and ELE at 14 cm working distance, SE had the lowest capture efficiency at 63%, followed by ELE at low-flow setting (74%). HVE showed a higher capture efficiency at 88%. The ELE operating at high-speed setting provided the best capture, with an efficiency of 96%. A combination of ELE at high-flow setting with either SE (94%) or HVE (95%) did not provide additional improvement in capture efficiency, which implies the best mitigation strategy may be to use an ELE (with proper flow setting, nozzle design, and placement relative to the patient and their oral cavity).

Figure 6.

Capture efficiency of various mitigation devices via laser sheet imaging when cleaning facial surface of teeth nos. 8 and 9. Error bars represent standard deviations of 3 measurements. +: A combination of 2 devices. ELE-H-x: Local extractor at high-flow setting at a distance of x cm. ELE-L-x: Local extractor at low-flow setting at a distance of x cm. HVE: High-volume evacuation. SE: Saliva ejector.

The reported efficiencies for LSI were consistently lower than those for DIH at sizes 30 through 120 μm, which can be explained by the existence of large spatters (with lower capture efficiency) in LSI video reduces the overall efficiency because a single large spatter contributes more intensity signal than a small droplet and by the differences in size and position of the FOV between DIH and LSI result in characterizations of different portions of aerosol and spatter populations from the same source.

When the ELE was moved 4 cm further away (from 14-18 cm) from the generation site, its capture efficiency dropped substantially from 74% to 38% at low-flow setting and from 96% to 56% at high-flow setting. This result suggests the importance of proper positioning of any extraoral mitigation devices for desired capture efficacy.

Discussion

Dental aerosols and spatters are potential transmission modes for many pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2, and it is vital to understand their generation profile and transportation behaviors in the air to support risk assessment and aerosol mitigation in the COVID-19 pandemic. The combination of the DIH and broader FOV of LSI provided important complementary characterization of aerosols generated by ultrasonic scaling with and without mitigation.

Ultrasonic scaler aerosol characterization

Among various engineering parameters, the size and velocity of original droplets are the most important ones that influence how they spread and evaporate and their ability of being inhaled to cause potential aerosol transmission. To our best knowledge, our study characterizes these 2 important droplet properties for the first time, using novel in situ optical methods. We report the wide spread of droplet sizes and the presence of both small and large droplets in the population. Small aerosols (< ≈ 50 μm) are not sampled effectively by any impingement-based collection surface, especially when their velocity is low owing to the lack of momentum in air. Our findings suggest these small aerosols likely have been overlooked in previous studies using surface collection methods for droplet sampling.

The droplet size and velocity reported in our study are properties measured close to their generation site outside of the oral cavity. When the droplets travel farther in the air, they evaporate to considerably smaller size, and the velocity relaxes close to the movement of the surrounding air. In view of the respiratory disease transmission, particles smaller than 10 μm (the size after droplets have reduced in size owing to evaporation) pose more risk than larger ones because they are more likely to remain suspended in air,44 bypass a face shield, penetrate through face masks and respirators,45, 46, 47 and be inhaled and deposited in the respiratory tract. The residual particle size depends on the size and composition of the original droplets. For dental-generated droplets, especially those generated via ultrasonic scaling, this is dominated by dissolved solid impurities in the cooling water, which is typically tap water filtered with a bacterial filter. Assuming a total dissolved solid level of 350 parts per million for typical tap water,48 , 49 a droplet with a 142 μm original size dries into a 10 μm solid residual, suggesting droplets smaller than approximately 150 μm should receive more attention in dental aerosol mitigation. Larger droplets, however, can deposit onto the ground, dental chairs and other equipment, bodies of patients or dental operators, and surfaces of face shields, face masks, or respirators, causing potential surface contamination. These findings, therefore, support the continued use of enhanced PPE in addition to regular surface cleaning and disinfection. The optical methods used in our study focused on initial droplets greater than 12 μm because smaller droplets can be effectively mitigated as suggested by the size-dependent capture efficiency shown in Figure 5 and verified by the greater than 95% capture measured by an aerodynamic particle sizer (TSI 3321; TSI) on residual particles (completely or partially dried droplets) ranging from 0.7 through 3 μm sampled at the same location as the FOV for DIH measurement.

Aerosol mitigation

The ultrasonic scaler did produce omnidirectional droplets as we expected, owing to the high-frequency oscillation of the ultrasonic tip. However, aerosol mitigation was shown, and the ELE was effective compared with the more traditional clinical mitigation strategies without the need for additional personnel. It was clear that proper positioning of the nozzle and airflow of the ELE is of great importance but that this could be accomplished without impeding the work position of the dental hygienist.

The low average droplet velocity observed in our study suggests suction-based point-of-source mitigation strategies such as those tested may be more effective than whole-room ventilation–based mitigation as has been recommended in other settings.13 , 50 The ELE works on a similar principle as an SE or an HVE but at a higher flow rate and a longer working distance. Unlike an HVE, it can be designed to remain in a fixed position, so an assistant is not needed to operate it. The downside of higher vacuum flow rate is that an ELE tends to generate higher noise in a larger space than an SE or an HVE. The ambient noise (measured via a VLIKE VL6708 sound level meter 10 cm above patient manikin’s chest) increased from 63.2 to 76.9 dB when the ultrasonic scaler was in use to 80.3 dB when the scaler was used in conjunction with the ELE at high flow. The maximum noise level was found at the patient manikin’s ear (near side of ELE), increasing from 81.1 dB (scaler on, ELE off) to 86.8 dB (scaler on, ELE on at high flow).

Room ventilation provided by heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems alone would require significantly higher flow for aerosol mitigation owing to the lack of focus on contamination sources. In addition, it is possible that air ventilation provided by an HVAC system could contribute to aerosol spread rather than mitigation, as an aerosol could travel throughout an entire room before eventually being vented by the room HVAC system (through which the aerosol may be recirculated if not properly filtered). With ELE, however, most contaminants are captured at the source and subsequently filtered.

Dental aerosol and infection risk

Not every aerosol or spatter from ultrasonic scalers carries pathogens, so the emission profiles measured in this study represent a worst-case scenario, which needs to be combined with a biological property evaluation for a more comprehensive risk assessment in the future. Because the knowledge regarding the infective dose of SARS-CoV-2 required to cause COVID-19 is still limited, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions as to the risks posed by dental aerosols and spatters and if the reported efficacy of the mitigation devices is sufficient. It is therefore recommended that multiple mitigation strategies be used to minimize the risk of dental aerosol transmission. We also recommend that dental practitioners continue to use enhanced PPE in addition to other aerosol-mitigation techniques.

Conclusions

The results of our study provide a scientific basis for risk assessment of aerosols and spatters from ultrasonic scaling. The engineering approaches of size and velocity profile characterization offer insight from a different angle; small aerosols, which may have been overlooked by previous studies, can pose a higher risk of transmitting infectious disease through the aerosol route, especially with the COVID-19 pandemic. Implementing a hands-free ELE can assist dental hygienists in implementing an effective, ergonomically sound method to reduce dental aerosols and spatters. Further research is needed on the biological property of these emissions for a comprehensive risk assessment. The methods in our study can be applied in the future to characterization of other AGPs in dental and medical settings to develop safe and efficient clinical practices in the face of highly contagious airborne diseases. Future investigations should include assessment of water-cooled high-speed handpieces as well as the interplay of point-of-source mitigation and clinical HVAC systems.

Biographies

Dr. Ou is a senior research scientist, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Mr. Placucci is a graduate student, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Ms. Danielson is a clinical professor, Department of Developmental and Surgical Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Dr. Anderson is a professor, Department of Developmental and Surgical Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Dr. Olin is a professor, Department of Restorative Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Dr. Jardine is a professor, Department of Diagnostic and Biological Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Mr. Madden is a dental laboratory production manager, Department of Restorative Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Dr. Yuan is the director of modeling and data science, Donaldson Company, Minneapolis, MN.

Mr. Grafe is the vice president, Donaldson Company, Minneapolis, MN.

Dr. Shao is a research scientist, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Dr. Hong is an associate professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Dr. Pui is a professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Footnotes

Disclosures. Dr. Yuan and Mr. Grafe work for Donaldson Company, the parent company of BOFA International, the designer and manufacturer of the extraoral local extractor tested in this study. None of the other authors reported any disclosures.

This study was supported partially by the Center for Filtration Research, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Qisheng Ou and Rafael Grazzini Placucci made equal contributions to this work.

Supplemental data related to this article can be found at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2021.06.007.

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Karia R., Gupta I., Khandait H., Yadav A., Yadav A. COVID-19 and its modes of transmission. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2(10):1798–1801. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00498-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding H., Broom A., Broom J. Aerosol-generating procedures and infective risk to healthcare workers from SARS-CoV-2: the limits of the evidence. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(4):717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo W., Chan B.H., Chng C.K., Shi A.H. Two cases of inadvertent dental aerosol exposure to COVID-19 patients. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2020;49(7):514–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ge Z., Yang L., Xia J., Fu X., Zhang Y. Possible aerosol transmission of COVID-19 and special precautions in dentistry. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2020;21(5):361–368. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B2010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mick P., Murphy R. Aerosol-generating otolaryngology procedures and the need for enhanced PPE during the COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-00424-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melo P., Barbosa J.M., Jardim L., Carrilho E., Portugal J. COVID-19 management in clinical dental care, part I: epidemiology, public health implications, and risk assessment. Int Dent J. 2021;71(3):251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2021.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2020. Considerations for the Provision of Essential Oral Health Services in the Context of COVID-19: Interim Guidance, 3 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Interim infection prevention and control guidance for dental settings during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/dental-settings.html#section-1 Accessed February 20, 2021.

- 9.Nagraj S.K., Eachempati P., Paisi M., Nasser M., Sivaramakrishnan G., Verbeek J.H. Intervention to reduce contaminated aerosols during dental procedures for preventing infectious diseases. Cochrane Databe Syst Rev. 2020;10:CD013686. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013686.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng X., Xu X., Li Y., Cheng L., Zhou X., Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):9. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amato A., Caggiano M., Amato M., Moccia G., Capunzo M., De Caro F. Infection control in dental practice during the covid-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):1–12. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Standard operating procedure. Transition to recovery. Office of Chief Dental Officer England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/06/C0575-dental-transition-to-recovery-SOP-4June.pdf Accessed February 20, 2021.

- 13.Industrial Ventilation: A Manual of Recommended Practice for Design. 28th ed. American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allison J.R., Currie C.C., Edwards D.C., et al. Evaluating aerosol and splatter following dental procedures: Addressing new challenges for oral health care and rehabilitation. J Oral Rehabil. 2021;48(1):61–72. doi: 10.1111/joor.13098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahlke W.O., Cottam M.R., Herring M.C., Leavitt J.M., Ditmyer M.M., Walker R.S. Evaluation of the spatter-reduction effectiveness of two dry-field isolation techniques. JADA. 2012;143(11):1199–1204. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufmann M., Solderer A., Gubler A., Wegehaupt F.J., Attin T., Schmidlin P.R. Quantitative measurements of aerosols from air-polishing and ultrasonic devices: (How) can we protect ourselves? PLoS One. 2020;15(12):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holliday R., Allison J.R., Currie C.C., et al. Evaluating contaminated dental aerosol and splatter in an open plan clinic environment: Implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dent. 2021;105:103565. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2020.103565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrel S.K., Barnes J.B., Rivera-Hidalgo F. Aerosol and splatter contamination from the operative site during ultrasonic scaling. JADA. 1998;129(9):1241–1249. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comisi J.C., Ravenel T.D., Kelly A., Teich S.T., Renne W. Aerosol and spatter mitigation in dentistry: analysis of the effectiveness of 13 setups. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2021;33(3):466–479. doi: 10.1111/jerd.12717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shahdad S., Patel T., Hindocha A., et al. The efficacy of an extraoral scavenging device on reduction of splatter contamination during dental aerosol generating procedures: an exploratory study. Br Dent J. Published online September 11, 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-2112-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrel S.K. Clinical use of an aerosol-reduction device with an ultrasonic scaler. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1996;17(12):1185–1193. quiz 1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiramana S., O S., Kadiyala K., Prakash M., Prasad T., Chaitanya S. Evaluation of minimum required safe distance between two consecutive dental chairs for optimal asepsis. J Orofac Res. 2013;3:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chavis S.E., Hines S.E., Dyalram D., Wilken N.C., Dalby R.N. Can extraoral suction units minimize droplet spatter during a simulated dental procedure? JADA. 2021;152(2):157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2020.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zemouri C., Volgenant C.M.C., Buijs M.J., et al. Dental aerosols: microbial composition and spatial distribution. J Oral Microbiol. 2020;12(1) doi: 10.1080/20002297.2020.1762040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holloman J.L., Mauriello S.M., Pimenta L., Arnold R.R. Comparison of suction device with saliva ejector for aerosol and spatter reduction during ultrasonic scaling. JADA. 2015;146(1):27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bentley C.D., Burkhart N.W., Crawford J.J. Evaluating spatter and aerosol contamination during dental procedures. JADA. 1994;125(5):579–584. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1994.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timmerman M.F., Menso L., Steinfort J., Van Winkelhoff A.J., Van Der Weijden G.A. Atmospheric contamination during ultrasonic scaling. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31(6):458–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., et al. China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dutil S., Mériaux A., De Latrémoille M.C., Lazure L., Barbeau J., Duchaine C. Measurement of airborne bacteria and endotoxin generated during dental cleaning. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2008;6(2):121–130. doi: 10.1080/15459620802633957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller R.L. Characteristics of blood-containing aerosols generated by common powered dental instruments. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1995;56(7):670–676. doi: 10.1080/15428119591016683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett A.M., Fulford M.R., Walker J.T., Bradshaw D.J., Martin M.V., Marsh P.D. Microbial aerosols in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2000;189(12):664–667. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacks M.E. A laboratory comparison of evacuation devices on aerosol reduction. J Dent Hyg. 2002;76(3):202–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matys J., Grzech-Leśniak K. Dental aerosol as a hazard risk for dental workers. Materials (Basel) 2020;13(22):1–13. doi: 10.3390/ma13225109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nulty A., Lefkaditis C., Zachrisson P., Van Tonder Q., Yar R. A clinical study measuring dental aerosols with and without a high-volume extraction device. Br Dent J. Published online November 12, 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-2274-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu F., Qian H., Zheng X., Song J., Cao G., Liu Z. Evaporation and dispersion of exhaled droplets in stratified environment. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2019;609(4) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu F., Zhang C., Qian H., Zheng X., Nielsen P.V. Direct or indirect exposure of exhaled contaminants in stratified environments using an integral model of an expiratory jet. Indoor Air. 2019;29(4):591–603. doi: 10.1111/ina.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Q., Qian H., Ren H., Li Y., Nielsen P.V. The lock-up phenomenon of exhaled flow in a stable thermally-stratified indoor environment. Build Environ. 2017;116:246–256. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawhney A., Venugopal S., Girish Babu R.J., et al. Aerosols how dangerous they are in clinical practice. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2015;9(4):52–57. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12038.5835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrel S.K., Barnes J.B., Rivera-Hidalgo F. Reduction of aerosols produced by ultrasonic sealers. J Periodontol. 1996;67(1):28–32. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teanpaisan R., Taeporamaysamai M., Rattanachone P., Poldoung N., Srisintorn S. The usefulness of the modified extra-oral vacuum aspirator (EOVA) from household vacuum cleaner in reducing bacteria in dental aerosols. Int Dent J. 2001;51(6):413–416. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2001.tb00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Junevicius J., Surna A., Surna R. Effectiveness evaluation of different suction systems. Stomatologija. 2005;7(2):52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shao S., Li C., Hong J. A hybrid image processing method for measuring 3D bubble distribution using digital inline holography. Chem Eng Sci. 2019;207:929–941. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sergis A., Wade W.G., Gallagher J.E., et al. Mechanisms of atomization from rotary dental instruments and its mitigation. J Dent Res. 2021;100(3):261–267. doi: 10.1177/0022034520979644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hinds W.C. Aerosol technology: properties, behaviour, and measurement of airborne particles. Wiley. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Aerosol+Technology%3A+Properties%2C+Behavior%2C+and+Measurement+of+Airborne+Particles%2C+2nd+Edition-p-9780471194101 Accessed January 24, 2021.

- 45.Pei C., Ou Q., Kim S.C., Chen S.-C., Pui D.Y.H. Alternative face masks made of common materials for general public: fractional filtration efficiency and breathability perspective. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2020;20(8):2581–2591. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ou Q., Pei C., Chan Kim S., Abell E., Pui D.Y.H. Evaluation of decontamination methods for commercial and alternative respirator and mask materials: view from filtration aspect. J Aerosol Sci. 2020;150:105609. doi: 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2020.105609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Konda A., Prakash A., Moss G.A., Schmoldt M., Grant G.D., Guha S. Aerosol filtration efficiency of common fabrics used in respiratory cloth masks. ACS Nano. 2020;14(5):6339–6347. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park M., Snyder S.A. In: Contaminants of Emerging Concern in Water and Wastewater. Hernande-Maldonado A., Blaney L., editors. Elsevier; 2020. Attenuation of contaminants of emerging concerns by nanofiltration membrane: rejection mechanism and application in water reuse; pp. 177–206. [Google Scholar]

- 49.What’s in your water: total dissolved solids (TDS) in drinking water. Quench. https://quenchwater.com/blog/tds-in-drinking-water/ Accessed February 20, 2021.

- 50.Li A., Kosonen R., Hagström K. In: Industrial Ventilation Design Guidebook. Goodfellow H., Tahti E., editors. Elsevier; 2020. Industrial ventilation design method. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.