Abstract

Objectives

Recently, it has been reported that cepharanthine (CEP) is highly likely to be an agent against Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). In the present study, a network pharmacology-based approach combined with RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq), molecular docking, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was performed to determine hub targets and potential pharmacological mechanism of CEP against COVID-19.

Methods

Targets of CEP were retrieved from public databases. COVID-19-related targets were acquired from databases and RNA-seq datasets GSE157103 and GSE155249. The potential targets of CEP and COVID-19 were then validated by GSE158050. Hub targets and signaling pathways were acquired through bioinformatics analysis, including protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis and enrichment analysis. Subsequently, molecular docking was carried out to predict the combination of CEP with hub targets. Lastly, MD simulation was conducted to further verify the findings.

Results

A total of 700 proteins were identified as CEP-COVID-19-related targets. After the validation by GSE158050, 97 validated targets were retained. Enrichment results indicated that CEP acts on COVID-19 through multiple pathways, multiple targets, and overall cooperation. Specifically, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway is the most important pathway. Based on PPI network analysis, 9 central hub genes were obtained (ACE2, STAT1, SRC, PIK3R1, HIF1A, ESR1, ERBB2, CDC42, and BCL2L1). Molecular docking suggested that the combination between CEP and 9 central hub genes is extremely strong. Noteworthy, ACE2, considered the most important gene in CEP against COVID-19, binds to CEP most stably, which was further validated by MD simulation.

Conclusion

Our study comprehensively illustrated the potential targets and underlying molecular mechanism of CEP against COVID-19, which further provided the theoretical basis for exploring the potential protective mechanism of CEP against COVID-19.

Keywords: Cepharanthine, COVID-19, ACE2, PI3K-Akt signal pathway, Network pharmacology, RNA-Sequencing, Molecular docking

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging infectious disease induced by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is a haunting coronavirus discovered in humans and has rapidly turned into a fatal pandemic [1]. Since the first case report of COVID-19 was released in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, more than 400 million patients were diagnosed and nearly 6 million have died, according to the World Health Organization, which reported that as of 11:55 a.m. Central European Time on Mar. 4, 2022 [2]. Mechanically, Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2), the receptor of SARS-CoV-2 to enter host cells, plays crucial effects in the occurrence and development of COVID-19 [3]. Currently, the existing therapies still need to balance effectiveness with side effects [4,5]. Thus, the current major task is to explore effective drugs for COVID-19 with stable efficacy and low toxicity at low cost.

Various natural bioactive compounds are known to contain a wide range of pharmacological activities with low toxicities on multiple diseases [[6], [7], [8], [9]], including COVID-19 [10]. Cepharanthine (CEP) is a natural alkaloid extracted from plants of the genus Stephania [11]. As shown in Fig. S1, the unique 1-benzylisoquinoline moiety of CEP has similarity to natural polypeptides, which arises the interest of researchers and a variety of studies have been carried out [12].

CEP, as a proven medicine for multiple diseases [11], possesses profound antiviral activity [13], including anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity [11,14]. Noteworthy, a paper in Science confirmed its potent anti-SARS-CoV-2 effect in A549 cells in a dose-dependent manner (EC50 = 0.1 μM), while remdesivir (an already approved drug by FDA for COVID-19) has an EC50 seven times higher than CEP at 0.72 μM [15]. Besides, CEP was granted a national invention patent in China for its anti-GX_P2V (an alternative coronavirus model for COVID-19 research) infection effect recently. The patent specification shows that the inhibition of virus replication in the CEP group (10 μM) was 15393 times greater than that in the virus group [16]. Therefore, coupled with the fact that CEP is an approved drug with a good safety profile (low toxicity in animals and no significant side effects in humans) and has been used in the clinic for more than 40 years [11,17], CEP is highly likely to be an agent against COVID-19 [16]. However, the specific mechanism of CEP against COVID-19 has not been fully illustrated.

Network pharmacology combines network biology with polypharmacology to directly identify targets of drugs and diseases from a massive amount of data and to predict the mechanisms and pathways underlying the multiple actions of drugs [18]. Besides, RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) is an indispensable approach for transcriptome-wide analysis of differential gene expression and differential splicing of mRNAs, and has been utilized in drug resistance, drug discovery and so on [19]. Moreover, molecular docking is an established in silico structure-based method broadly used in modern drug design, capable of predicting ligand-protein interactions, estimating the binding free energy, outlining structure-activity relationships, etc [20]. What's more, molecular dynamics (MD) simulation helps study the conformational transition of proteins caused by ligand binding/unbinding and the relationship between protein structure and function [21].

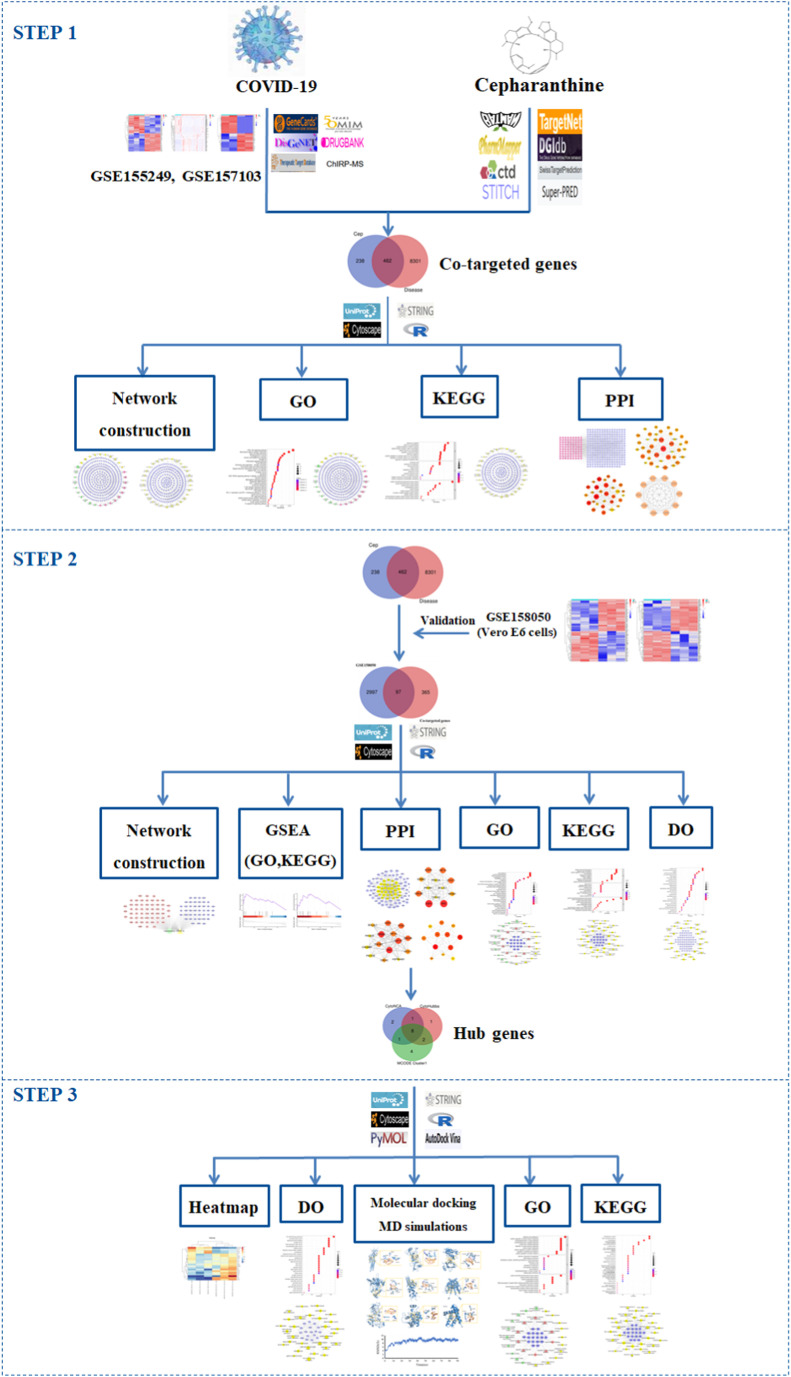

In the present research, we discovered the potential targets, signaling pathways and underlying molecular mechanism of CEP against COVID-19 using a network pharmacology-based strategy, combined with RNA-seq analysis, molecular docking, and MD simulation. The workflow is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of analysis process in the present study. Network pharmacology and RNA-seq data were used to analyze and screen hub targets in CEP against COVID-19. GO, KEGG, GSEA, and DO enrichment analyses were conducted to illustrate potential molecular mechanisms underlying CEP's protective effects on COVID-19. Molecular docking revealed that there exists a strong binding affinity between CEP and the 20 hub genes. MD simulation further verified the results of molecular docking.

2. Methods

2.1. Collection of potential targets of CEP

Putative targets of CEP were obtained from 8 online databases containing PharmMapper Server (http://www.lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/index.html), A Bioinformation Analysis Tool for Molecular mechanism of Traditional Chinese Medicine (BATMAN-TCM, http://bionet.ncpsb.org.cn/batman-tcm/), Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD, http://ctdbase.org/), The Drug Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb, https://www.dgidb.org/), Search Tool for Interacting Chemicals (STITCH, http://stitch.embl.de/), SuperPred (http://prediction.charite.de/), SwissTargetPrediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/), and TargetNet (http://targetnet.scbdd.com/home/index/). The UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) was applied to convert protein names to their corresponding gene symbols in this study due to its comprehensive, high-quality, and freely accessible resource of protein sequence and functional information [22].

2.2. Identification of COVID-19-related therapeutic target genes

For a more comprehensive search for potential therapeutic targets associated with COVID-19, three strategies were utilized.

First, we searched the keywords “COVID-19” and “SARS-CoV-2” from 5 public databases, including Therapeutic Target Database (TTD, http://db.idrblab.net/ttd/), DrugBank (https://go.drugbank.com/), GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/), DisGeNET (https://www.disgenet.org/), and Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM, https://omim.org/).

In addition, host proteins directly interacting with viral RNAs may play significant roles in the occurrence and development of the disease and can be considered as potential targets for antiviral drugs. Therefore, we downloaded the ChIRP-MS results of a piece of literature studying human proteins interacting with SARS-CoV-2 RNAs23 .

Besides, RNA-seq datasets related to COVID-19 in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) [24] were enrolled in analysis, including GSE155249 (human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples) [25], GSE155249 (NHBE cells) [25], and GSE157103 (human plasma samples) [26]. R 4.2.0 software and related R packages (“edgeR” for GSE155249, “limma” for GSE157103, “pheatmap” for both) were adopted to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and draw the heatmaps. |Log2Fold change (FC)|>0.585 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 were taken as the screening criteria.

2.3. RNA-seq data analysis for GSE158050

In the research of GSE158050 [27], after being plated in T75 culture flasks for 24 h at a density of 1.5 × 107 cells/flask, Vero E6 cells (derived from the kidney of an African green monkey) were treated with GX_P2V (an alternative model for COVID-19 research, MOI = 0.01), CEP (6.25 μM), or CEP + GX_P2V, and then cultured for another 72 h. The RNA-seq libraries were constructed using the NEBNext Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB) and sequenced on Hiseq 2500 sequencing system (Illumina). We downloaded the raw RNA-seq data and adopted the R packages “limma” and “pheatmap” to normalize RNA-seq data, identify DEGs (FC > 1.2 or FC < 0.83, P < 0.05) and draw heatmaps.

2.4. Enrichment analyses

R 4.2.0 and related R packages were adopted for enrichment analyses. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis were carried out based on R packages “colorspace”, “stringi”, “ggplot2“, “DOSE”, “clusterProfiler”, and “enrichplot”. The signaling pathway diagrams were visualized by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, https://www.kegg.jp/). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was based on R packages “clusterProfiler” and “enrichplot”. Disease Ontology (DO) analysis was based on R packages “colorspace”, “stringi”, “ggplot2”, “org.Hs.eg.db”, “DOSE”, “clusterProfiler”, “enrichplot”, and “GSEABase”.

2.5. Network construction

Multiple networks, including CEP-targets network, CEP-targets-disease network, CEP-validated targets-disease network, targets-ontology networks, targets-pathways networks, and targets-diseases networks, were visualized by Cytoscape 3.7.2, in which degree values of nodes were calculated by CytoNCA.

2.6. Establishment of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks

First, targets were submitted to STRING database (https://string-db.org/cgi/input.pl). After selecting “Homo sapiens” as the species and hiding the independent proteins, the PPI results were exported and then imported into Cytoscape 3.7.2, which is widely applied to establish and analyze networks, especially in the field of network pharmacology. Three Cytoscape plugins were utilized for core networks and hub genes.

First, the CytoNCA plugin was adopted to analyze six topological parameters (betweenness centrality (BC), closeness centrality (CC), degree centrality (DC), eigenvector centrality (EC), network centrality (NC), and local average connectivity (LAC)) of nodes in the original PPI network. The higher value of a node's topological parameter stands for the greater significance of the node in the network. Only nodes whose six parameters are higher than the corresponding median values were retained for further research. After screening twice, a core PPI network was screened out.

Second, CytoHubba was adopted to analyze the Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) values of nodes in the original PPI network and a core PPI network containing proteins with the biggest MCC values was established.

Last, MCODE was applied for extracting clusters from the original PPI network and ranking clusters according to score values (degree cutoff = 2, node score cutoff = 0.2, K-score = 2, Max. Depth = 100).

For PPI network of co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19, the minimum required interaction score in STRING was set to 0.9, while for PPI network of validated CEP-COVID-19 genes, the minimum required interaction score was set to 0.4.

2.7. Molecular docking of hub genes

Molecular docking is frequently applied in drug discovery owing to its capacity to accurately calculate the conformation of ligands within the appropriate target binding site and the binding affinity [28,29]. Therefore, 20 hub genes that may play significant roles in CEP against COVID-19 were selected for simulation docking with CEP. The docking was conducted based on AutoDock tools 1.5.6 and Vina (ie, AutoDock Vina), both of which have been widely used for molecular docking with the capacity to improve the speed and accuracy of docking with a novel scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading [30,31]. The specific process was as follows:

-

(1)

The preparation of protein receptor PDBQT files: Structures of proteins were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB, http://www.rcsb.org/) [32] or AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (AlphaFold DB, https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk) [33], and then inputted into Pymol software to remove water molecules, co-crystallized ligand and ions. Thereafter, in AutoDock tools 1.5.6 software, non-polar hydrogens of proteins were merged to corresponding carbons, and missing hydrogens and Kollman partial charges were added to proteins. The protein files were then saved as PDBQT format.

-

(2)

The preparation of CEP file: The 2D structure of CEP was downloaded from PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), imported into Chem3D software to minimize energy (in MM2 force field), and then transferred to 3D structures. Subsequently, in AutoDock tools 1.5.6 software, the obtained 3D structure of CEP was modified by the addition of hydrogens and protonation. Non-polar hydrogens were merged to corresponding carbons rotations. The CEP file was then saved as PDBQT format.

-

(3)

The establishment of mating pockets: In AutoDock tools 1.5.6, the PDBQT files of proteins were utilized for the construction of mating pockets. After setting spacing to 1 Å and the appropriate size of the mating box to keep the protein totally covered by the box for blind docking, configuration (config) files were outputted including the information on mating boxes for further docking.

-

(4)

Docking and visualization: After finishing preparing PDBQT files and config files for docking, Vina software was applied for Rigid docking and calculation of the binding affinity based on the PDBQT files of proteins and CEP, as well as config files. The docking results including the information on docking sites and binding energy were outputted as.pdbqt* and log*.txt files. The interactions of docking models were obtained by Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP, https://plip-tool.biotec.tu-dresden.de/plip-web/plip/) [34] and visualized by Pymol [35], both of which have been widely applied to visualize the docking site and hydrogen-bond interaction patterns between the ligands and proteins.

2.8. MD simulation

MD simulation was performed to simulate the binding stability of CEP and ACE2 by AMBER16 software [36] (in AmberFF99SB force field). After establishing a 1-nm protein-centered cubic water box and adding ions (Na+) to make the system electrically neutral, MD simulation was conducted. The specific process was as follows:

-

(1)

Two-step energy minimization: First, the protein was restricted and the energy of the water molecule was minimized. Then the energy of the whole system was minimized by releasing the protein. The first step of energy minimization included 5000 cycles, in which the steepest descent method was used for 1500 cycles. The second step of energy minimization included 5000 cycles, in which the steepest descent method was used for 2000 cycles.

-

(2)

The balance of the system: The system was heated from 0 °C to 100 °C within 100ps using Langevin temperature control method. The boost balance was then obtained for 100ps using the isotropic Berendsen voltage control method.

-

(3)

Dynamic simulation: A constant temperature of 100 °C was set for the overall system. The same temperature and voltage control methods as in the (2) stage were used. The cutoff distance between van der Waals energy and short-range electrostatic energy was 10 Å [37], and the Particle-Mesh-Ewald method was used to calculate the long-range electrostatic energy [38].

During the simulation of the protein system, the human body temperature was used, time was controlled at 90 ns, and the average structure of the protein system was obtained by extracting the trajectories of MD simulation in the 30–90 ns. The stability of system was evaluated using the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the aligned protein-ligand coordinate set calculated against the initial frame. The visualization of protein-ligand complex was performed with PyMOL [35].

Script (MMPBSA.py) in AMBER software was applied for the calculation of the binding free energy between protein-ligand complex [39], where the CEP ligand is the small molecule and ACE2 protein is the receptor. Thereby, MM-PBSA analysis was conducted to calculate the Gibbs free energy of the binding between the protein and the molecular ligand using the last 10–50 ns stable RMSD trajectorie.

3. Results

3.1. Target genes of CEP

Reviewed or predicted target genes of CEP were retrieved in 8 databases, with a result of 203 targets in PharmMapper, 72 in BATMAN, 6 in CTD, 4 in DGIdb, 4 in STITCH, 135 in Superpred, 109 in SwissTargetPrediction, and 592 in TargetNet (Table S1). After removing duplicate targets and transferring protein names to gene symbols, a total of 700 putative targets of CEP were obtained.

3.2. COVID-19-related target genes

First, we searched 5 databases using “COVID-19” and “SARS-CoV-2” as the keywords, with a result of 72 targets in TTD, 25 in Drugbank, 3977 in GeneCards, 1843 in DisgeNet, and 1 in OMIM. After taking a union and transferring protein names to gene symbols, a total of 5206 target genes associated with COVID-19 were collected (Fig. S2A).

Besides, host proteins that directly interact with viral RNAs may play significant roles in the occurrence and development of the disease, which can also be considered as potential targets for antiviral drugs. Recently, a team has reported human proteins which interact with SARS-CoV-2 RNAs by the method of ChIRP-MS23 . After downloading the supplementary data from this research, we obtained 143 proteins proven to directly interact with SARS-CoV-2 RNAs, which were also set as putative COVID-19 targets in our study.

What's more, to enrich potential COVID-19-related target genes, RNA-seq datasets in GEO databases were also enrolled in analysis. After setting the selection criteria of |log2FC|>0.585 and FDR<0.05, 319 DEGs from GSE155249 (human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples), 296 DEGs from GSE155249 (NHBE cells), and 4813 DEGs from GSE157103 (human plasma samples) were identified (Figs. S3A–C).

Combining targets from databases, ChIRP-MS, and RNA-seq datasets, a total of 8763 targets were retrieved and considered as the targets related to COVID-19 for subsequent study (Fig. S2B and Table S2).

3.3. Co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19

The comparison of 700 potential targets of CEP with 8763 candidate DEGs related to COVID-19 revealed 462 common genes, which were considered co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19 (Fig. S2C and Table S3).

3.4. GO enrichment analysis and targets-ontology network of co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19

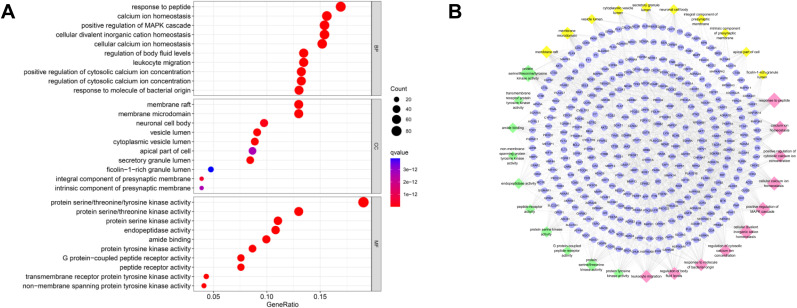

The GO enrichment analysis involves biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF). We obtained a total of 3457 statistically significant GO terms, including 3030 BP, 147 CC, and 280 MF. The top 10 significant enrichment entries of BP, CC and MF with the lowest q value are visualized in a bubble diagram (Fig. 2 A), in which the redder color of a dot stands for the lower the q value and the more significant enrichment of the term. A bigger dot represents higher gene counts in the entry. Furthermore, to better elucidate the interrelationships of targets and the top 10 significant enrichment entries of BP, CC and MF, targets-ontology network containing 378 nodes and 1497 edges was constructed (Fig. 2B). Blue ellipse nodes represent targets, while red, yellow, and green diamond nodes represent BP, CC, and MF of GO entries, respectively. The larger the diamond node, the greater the degree value of the node, and the greater the number of genes enriched in this GO entry, indicating its more significant role in the treatment of COVID-19 by CEP.

Fig. 2.

GO enrichment analysis of co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19, including the top 10 significant enrichment terms of BP, CC, and MF, respectively. (A) The bubble diagram. The abscissa indicates the proportion of genes of interest in the entry, while the ordinate represents each GO entry. The bigger the dot, the more genes are annotated in the entry; the redder the color of the dot, the lower the q value. (B) Targets-ontology network. Blue ellipse nodes represent co-targeted genes, while red, yellow, and green diamond nodes represent BP, CC, and MF of GO entries, respectively. The larger size of the diamond node indicates the greater the degree value of the GO entry.

The results revealed that the co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19 are mainly enriched in response to peptide (GO:1901652), calcium ion homeostasis (GO:0055074), positive regulation of cytosolic calcium ion concentration (GO:0007204), and other biological processes; in membrane raft (GO:0045121), membrane microdomain (GO:0098857), vesicle lumen (GO:0031983), and other cellular components; in protein serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase activity (GO:0004712), protein tyrosine kinase activity (GO:0004713), protein serine/threonine kinase activity (GO:0004674), and other molecular functions.

3.5. KEGG enrichment analysis and targets-pathways network of co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19

The KEGG analysis was applied to explore the functions and signaling pathways of the identified anti-COVID-19 targets of CEP. The KEGG pathway annotation indicated that 249 of the 462 target genes are enriched and yield a total of 187 statistically significant pathways, among them, the top 30 significant enrichment potential pathways with the lowest q value are presented in a bubble diagram (Fig. 3 A). Besides, the interactions of targets and the top 30 pathways are visualized by a targets-pathways network containing 279 nodes and 1169 edges (Fig. 3B), in which blue ellipse nodes represent targets, while yellow diamond nodes represent pathways. The larger the pathway node, the greater the degree value of the node, and the more crucial the pathway in anti-COVID-19.

Fig. 3.

KEGG enrichment analysis of co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19, including top 30 most significant pathways. (A) The bubble diagram. The x-axis represents the proportion of genes of interest in the entry, while the ordinate represents each pathway. The larger the dot, the more genes are annotated in that entry; the redder the color of the dot, the lower the q value. (B) Targets-pathways network. Blue ellipse nodes and yellow diamond nodes represent co-targeted genes and pathways, respectively. The larger size of the yellow pathway node indicates the greater the degree value.

The pathways with top 5 highest gene counts are PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (hsa04151, n = 68), neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction (hsa04080, n = 61), lipid and atherosclerosis (hsa05417, n = 53), proteoglycans in cancer (hsa05205, n = 50), and human papillomavirus infection (hsa05165, n = 50). Specifically, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, which possesses the largest gene counts among COVID-19-related pathways, could be the most important pathway in the treatment of COVID-19 for CEP (Fig. S4A).

What interests us is that some target genes are involved in multiple pathways, for example, SRC is involved in 38 KEGG pathways, including lipid and atherosclerosis, human cytomegalovirus infection, chemokine signaling pathway and so on. Collectively, CEP acts on COVID-19 through multiple pathways, multiple targets, and overall cooperation.

3.6. Construction of CEP-targets network and CEP-targets-disease network

To better visualize the relationship between targets, CEP, and COVID-19, we constructed CEP-targets network consisting of 701 nodes and 700 edges (Fig. S5A) and CEP-targets-disease network consisting of 464 nodes and 924 edges (Fig. S5B). Orange ellipse nodes indicate target genes, green hexagon nodes indicate CEP, while yellow triangle node indicates COVID-19.

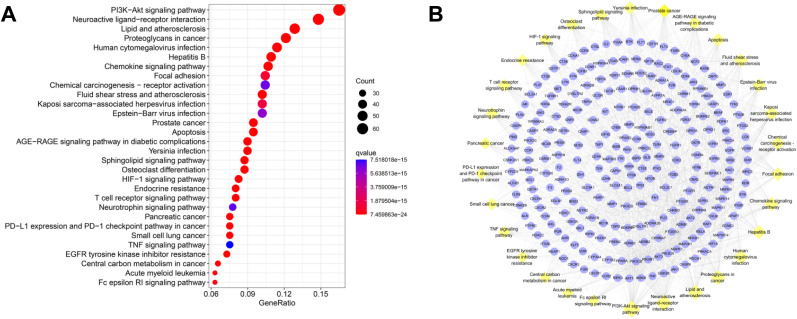

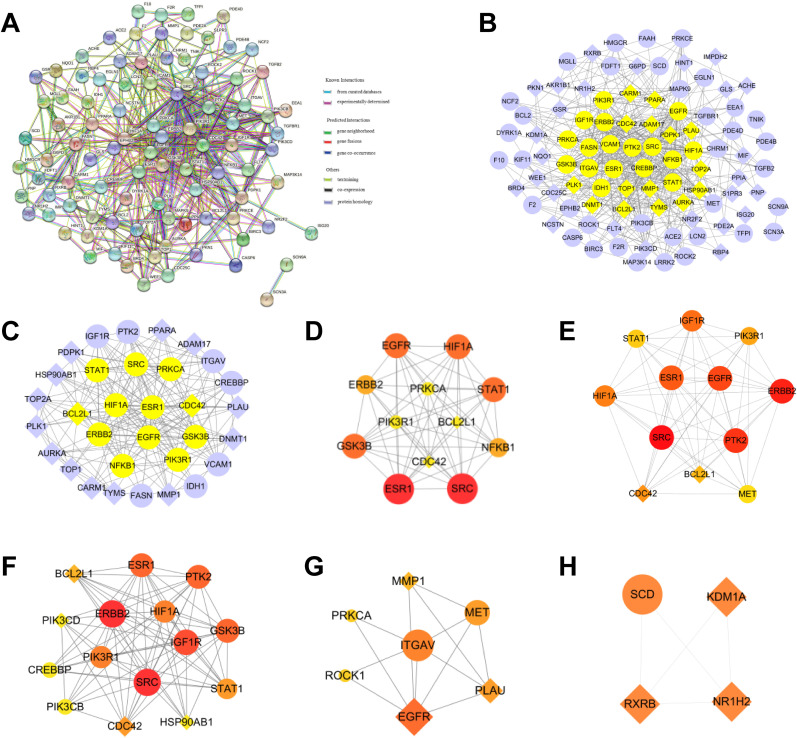

3.7. Construction and topological analysis of PPI network of co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19

462 CEP-COVID-19-related genes were submitted to STRING, and a PPI network containing 360 nodes and 1876 edges was output (minimum interaction score = 0.9), in which nodes represent proteins and edges represent protein-protein interactions (Fig. 4 A). In order to better visualize the interactions, the retrieved PPI data were subsequently imported into Cytoscape 3.7.2 to construct a new PPI network, which also includes 360 nodes and 1876 edges (Fig. 4B). Three Cytoscape plugins, CytoNCA, CytoHubba, and MCODE, were employed to analyze the PPI network and mine the core networks and hub proteins.

Fig. 4.

PPI networks of co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19. (A) The interactive PPI network obtained from STRING database with the minimum required interaction score set to 0.9. It comprises 360 nodes and 1876 edges. Each node represents relevant targets, and edges indicate protein-protein associations, including known interactions (azure represents curated database evidences, purple indicates experimentally determined evidences), predicted interactions (green represents gene neighborhood, red stands for gene fusions, and dark blue indicates gene co-occurrence), and others (light green represents textmining, black stands for co-expression, and light blue indicates protein homology). (B) PPI network imported from STRING database to Cytoscape 3.7.2. Pink nodes are the genes further validated by GSE158050. (C) PPI network of more significant proteins extracted from (B) by using CytoNCA to filter 6 topological parameters. This network is made up of 111 nodes and 993 edges. Pink nodes are the genes further validated by GSE158050. (D) Core PPI network extracted from (C) by using CytoNCA to filter 6 topological parameters, which contains 39 nodes and 353 edges. Nodes with higher degree values are larger and redder. (E) Using CytoHubba to obtain a core PPI network from (B) containing the top 30 nodes with the largest MCC values. (F–H) Top 3 highest scoring clusters extracted from (B) by using MCODE, with score of 10.00 (F), 7.79 (G), and 7.20 (H), respectively. (I) Venn diagram of important genes from core PPI networks.

By utilizing CytoNCA plugin to calculate 6 parameters (BC, CC, DC, EC, NC and LAC) of each node in Fig. 4B, the selection criteria were set based on the corresponding median values (BC > 108.76, CC > 0.076, DC > 6.00, EC > 0.011, LAC> 2.33, NC > 3.25), and only nodes meeting the criteria were retained and a new PPI network made up of 111 nodes and 993 edges was extracted (Fig. 4C). Likewise, by setting the selection criteria for nodes in Fig. 4C (BC > 41.70, CC > 0.50, DC > 15.00, EC > 0.065, LAC>6.35, NC > 7.55), only nodes meeting the criteria were retained and the core PPI network made up of 39 nodes and 353 edges was obtained (Fig. 4D).

After ranking MCC values of nodes in the original PPI network by CytoHubba, a core network consisting of the top 30 nodes with the greatest MCC values was visualized in a new core network (Fig. 4E).

Module analysis of the original PPI network was performed using MCODE. 16 clusters were identified, and the top 3 clusters with the highest scores were visualized as shown in Fig. 4F–H, with score of 10, 7.786, and 7.2, respectively.

Degree value of a node indicates the number of interactions with other nodes, therefore referring to the significance of the node. To better analyze the PPI networks and the hub genes, node degree distribution of networks in Fig. 4 is presented in Figs. S6A–G, while the degree values of proteins in core networks from Fig. 4D–F were calculated and displayed in Figs. S6H–J.

To further search for crucial targets, genes that are in the core PPI network formed by CytoNCA, core PPI network formed by CytoHubba, and one of the top 3 clusters formed by MCODE, were considered crucial targets (SRC, PIK3R1, FYN, RAC1, GRB2, EGFR, PTK2, CDC42, JAK1, ITGB3, ITGB1, and ITGAV), which are the potential target genes for CEP against COVID-19 (Fig. 4I).

3.8. GO and KEGG analysis of three clusters in Fig. 4F–H

In order to illustrate the functions of 3 clusters in Fig. 4F–H obtained from MCODE, GO and KEGG analyses were carried out as shown in Fig. S7.

For cluster 1, most GO terms of BP are related to arachidonic acid metabolic process (GO:0019369), long-chain fatty acid metabolic process (GO:0001676), and unsaturated fatty acid metabolic process (GO:0033559); the main terms of CC are associated with nuclear envelope lumen (GO:0005641), organelle envelope lumen (GO:0031970), and photoreceptor outer segment (GO:0001750); the top 3 pathways are arachidonic acid metabolism (hsa00590), serotonergic synapse (hsa04726), and linoleic acid metabolism (hsa00591).

For cluster 2, most GO terms of BP are related to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling (GO:0014065), phosphatidylinositol-mediated signaling (GO:0048015), and inositol lipid-mediated signaling (GO:0048017); the main terms of CC are focal adhesion (GO:0005925), cell-substrate junction (GO:0030055), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex (GO:0005942); MF enrichment is mainly involved in protein phosphatase binding (GO:0019903), phosphatase binding (GO:0019902), and protein tyrosine kinase activity (GO:0004713); the top 3 pathways are PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (hsa04151), focal adhesion (hsa04510), and proteoglycans in cancer (hsa05205).

For cluster 3, most GO terms of BP are related to phagocytosis (GO:0006909), integrin-mediated signaling pathway (GO:0007229), and cell-substrate adhesion (GO:0031589); the main terms of CC are leading edge membrane (GO:0031256), ruffle membrane (GO:0032587), and extrinsic component of cytoplasmic side of plasma membrane (GO:0031234); MF enrichment is mainly involved in non-membrane spanning protein tyrosine kinase activity (GO:0004715), protein tyrosine kinase activity (GO:0004713), and integrin binding (GO:0005178); the top 3 pathways are focal adhesion (hsa04510), proteoglycans in cancer (hsa05205), and regulation of actin cytoskeleton (hsa04810).

3.9. Analysis of RNA-seq data

In order to validate the predicted co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19, we searched for GEO database for RNA-seq data.

GX_P2V is a SARS-CoV-2-related pangolin virus, whose spike protein shares 92.2% amino acid identity with SARS-CoV-2 and whole-genome sequence identities to the SARS-CoV-2 is 90.4% [40,41]. Besides, GX_P2V uses ACE2 as the receptor for infection just like SARS-CoV-2 and is nonpathogenic in humans [41]. Altogether, due to its close relationship to SARS-CoV-2, shared receptor ACE2 and non-pathogenicity, coronavirus GX_P2V can be used as an accessible in vitro model for developing therapies against SARS-CoV-2. In the research of GSE158050 [27], researchers studied CEP in Vero E6 cell culture model infected with GX_P2V to uncover the potential mechanisms of the antiviral activities of CEP, providing evidence for CEP as a promising therapeutic option for SARS-CoV-2 infection. After downloading and analyzing the RNA-seq data (FC > 1.2 or FC < 0.83, P < 0.05), 3766 DEGs were identified when comparing control group with virus group, among which 1982 are regulated and 1784 are down-regulated in virus group. 3094 DEGs, among which 1606 are regulated and 1488 are down-regulated in virus + CEP group, were identified when comparing virus group with virus + CEP group and utilized for further validation of predicted co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19 (Figs. S3D–E and Table S4).

3.10. Identification of validated CEP-COVID-19 genes and the construction of CEP-validated targets-disease network

After intersecting the 3094 DEGs with 462 co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19, 97 validated genes were identified (Fig. S2D), which were then imported into Cytoscape 3.7.2 to form CEP-validated targets-disease network with 99 nodes and 194 edges as shown in Fig. S5C, in which green octagon indicates CEP, yellow triangle indicates COVID-19, pink ellipse nodes indicate validated up-regulated targets (n = 54), while blue diamond nodes indicate validated down-regulated targets (n = 43).

3.11. GSEA analysis of 3094 DEGs and 97 validated CEP-COVID-19 genes

GSEA is a common method for functional enrichment analysis, which can determine significant differences between two biological statuses in a certain gene set [42]. As shown in Fig. 5 A, for 3094 DEGs when comparing virus group and virus + CEP group in GSE158050, GSEA based on the KEGG gene set showed that entries of oxidative phosphorylation, Parkinsons disease, spliceosome, etc. are activated in virus group; entries of steroid biosynthesis, ECM-receptor interaction, Leishmania infection, RIG-I like receptor signaling pathway, steroid hormone biosynthesis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, etc. are activated in virus + CEP group. As shown in Fig. 5B, GSEA based on the GO gene set showed that entries of cell projection assembly (BP), cilium organization (BP), external encapsulating structure organization (BP), tube development (BP), tube morphogenesis (BP), vasculature development (BP), cell surface (CC), cilium (CC), external encapsulating structure, intrinsic component of plasma membrane (CC), intrinsic component of plasma membrane (CC), etc. are activated in virus + CEP group.

Fig. 5.

The typical GESA enrichment entries for 3094 DEGs based on the KEGG gene set (A) and GO gene set (B), as well as 97 validated genes based on the KEGG gene set and GO gene set (C).

As shown in Fig. 5C for 97 validated genes associated with CEP and COVID-19, GSEA based on the KEGG gene set showed that pathway entry of regulation of actin cytoskeleton is activated in virus + CEP group. GSEA based on the GO gene set showed that entries of cation transport (BP), G protein coupled receptor signaling pathway (BP), intracellular transport (BP), regulation of transmembrane transport (BP), transmembrane transport (CC), endoplasmic reticulum (CC), membrane protein complex (CC), and plasma membrane protein complex (CC) are activated in virus + CEP group; while protein containing complex binding (MF) is activated in virus group. These results further mirror the therapeutic mechanism of CEP on COVID-19.

3.12. GO enrichment analysis and targets-ontology network of validated genes of CEP and COVID-19

In GO analysis, 69 of 97 validated target genes are significantly enriched in 1506 BP, 42 CC, and 95 MF. The top 10 significant enrichment entries of BP, CC and MF with the lowest q value are visualized by a bubble diagram (Fig. 6 A) and a targets-ontology network containing 378 nodes and 1497 edges (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

GO enrichment analysis of validated genes of CEP and COVID-19, including the bubble diagram (A) and targets-ontology network (B).

The results revealed that the validated genes of COVID-19 and CEP are mainly enriched in peptidyl-serine phosphorylation (GO:0018105), peptidyl-serine modification (GO:0018209), positive regulation of protein localization (GO:1903829), and other biological processes; in vesicle lumen (GO:0031983), secretory granule lumen (GO:0034774), cytoplasmic vesicle lumen (GO:0060205), and other cellular components; in protein serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase activity (GO:0004712), protein serine/threonine kinase activity (GO:0004674), protein tyrosine kinase activity (GO:0004713), and other molecular functions.

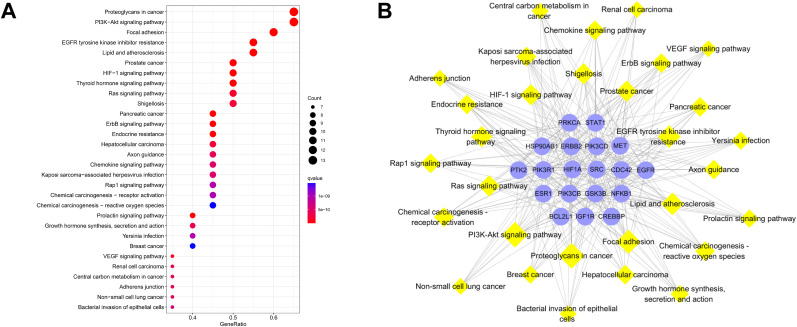

3.13. KEGG enrichment analysis and targets-pathways network of validated genes of CEP and COVID-19

A total of 53 of 97 validated targets are enriched in 138 pathways that potentially participate in the anti-COVID-19 mechanism of CEP, among them, the top 30 significant enrichment potential pathways are presented in a bubble diagram (Fig. 7 A) and visualized by a targets-pathways network containing 83 nodes and 354 edges (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

KEGG enrichment analysis of validated genes of CEP and COVID-19, including the bubble diagram (A) and targets-pathways network (B).

The pathways with top 5 highest gene counts are PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (hsa04151, n = 20), focal adhesion (hsa04510, n = 20), lipid and atherosclerosis (hsa05417, n = 20), proteoglycans in cancer (hsa05205, n = 19), and microRNAs in cancer (hsa05206, n = 17). Notably, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, which possesses the largest gene counts, could be the most important pathway in the treatment of COVID-19 of CEP (Fig. S4B).

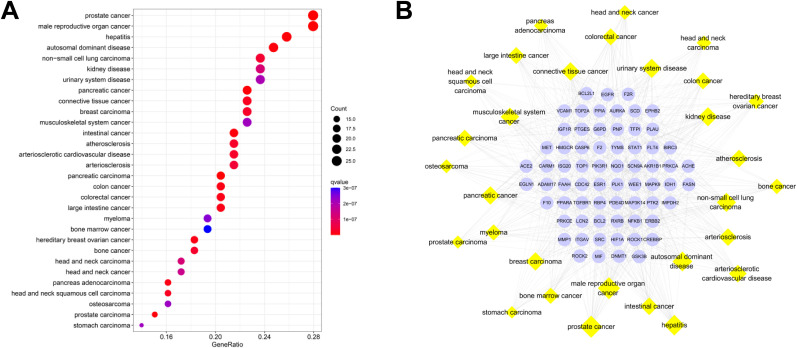

3.14. DO analysis and targets-diseases network of validated genes of CEP and COVID-19

DO enrichment analysis can provide visual analysis of the relationship between the targets and the diseases, and facilitate the development of effective health informatics tools that guide diagnostics and disease-phenotype, as well as disease-drug association predictions [43]. Therefore we performed DO analysis and 67 of 97 validated targets are significantly enriched in 296 diseases. The top 30 disease entries according to q value are displayed in a bubble diagram, in which the redder color of the bubble indicates the more significant of the disease (Fig. 8 A). A targets-diseases network was also constructed (Fig. 8B). Target nodes are in blue while disease nodes are in yellow. The size of the disease node corresponds with the gene counts of the disease entry.

Fig. 8.

DO analysis of validated CEP-COVID-19 genes, including top 30 most significant disease entries. (A) The bubble diagram. The x-axis represents the proportion of genes of interest in the entry, while the y-axis represents each disease. (B) Targets-diseases network. Blue ellipse and yellow diamond nodes represent validated genes and diseases, respectively.

Top 5 DO entries with the greatest number of genes are prostate cancer (DO ID: 10283, n = 26), male reproductive organ cancer (DO ID: 3856, n = 26), hepatitis (DO ID: 2237, n = 24), autosomal dominant disease (DO ID: 0050736, n = 23), and non-small cell lung carcinoma (DO ID: 3908, n = 22). DO results suggested that validated targets of CEP and COVID-19 may target multi-organs, including lungs, thereby treating COVID-19.

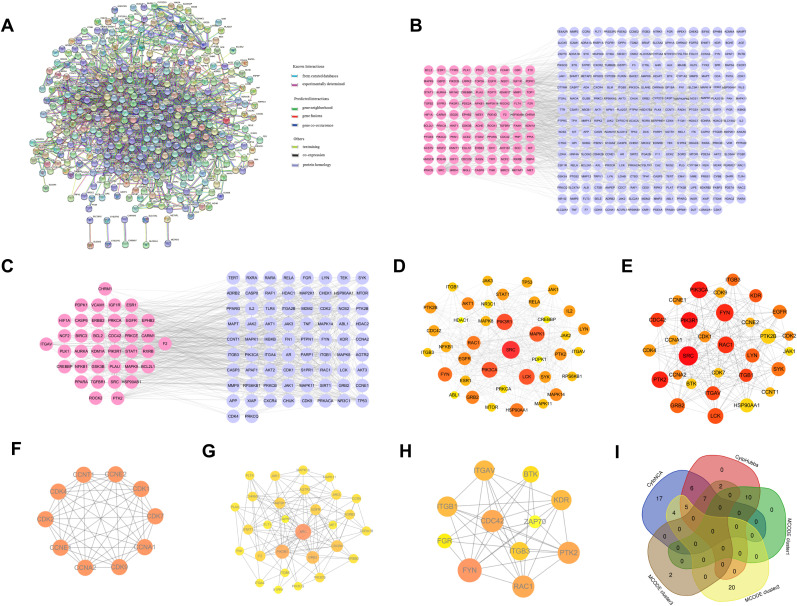

3.15. Construction and topological analysis of PPI network of validated genes of CEP and COVID-19

After submitting 97 validated genes to STRING (interaction score>0.4), a PPI network containing 94 nodes and 498 edges was formed (Fig. 9 A), which was then imported into Cytoscape 3.7.2 to create a new PPI network also containing 94 nodes and 498 edges (Fig. 9B). Likewise, three Cytoscape plugins, CytoNCA, CytoHubba, and MCODE, were utilized to mine the core networks and hub proteins.

Fig. 9.

PPI networks of validated genes of CEP and COVID-19, in which ellipse nodes and diamond nodes stand for up-regulated and down-regulated targets, respectively, based on GSE158050. (A) The interactive PPI network obtained from STRING database (interaction score> 0.4) with 94 nodes and 498 edges. (B) PPI network imported from STRING database to Cytoscape 3.7.2. (C) By using CytoNCA, PPI network extracted from (B) with 32 nodes and 208 edges. (D) By using CytoNCA, the core PPI network extracted from (C) with 12 nodes and 56 edges. (E) Using CytoHubba to obtain a core PPI network from (B) containing the top 12 nodes with the largest MCC values. (F–H) Three clusters extracted from (B) by using MCODE with score of 11.14 (F), 4.33 (G), and 3.33 (H), respectively.

By utilizing CytoNCA to calculate 6 topological parameters of each node in Fig. 9B, the selection criteria were set (BC > 35.68, CC > 0.24, DC > 8.00, EC > 0.054, LAC> 3.53, NC > 4.69), and only nodes meeting the criteria were retained and colored in yellow in Fig. 9B, thereby extracting a new PPI network made up of 32 nodes and 208 edges (Fig. 9C). Likewise, by setting the selection criteria for nodes in Fig. 9C (BC > 7.66, CC > 0.62, DC > 12.00, EC > 0.16, LAC>7.21, NC > 8.57), only nodes meeting the criteria were retained and colored in yellow in Fig. 9C, thereby obtaining the core PPI network made up of 12 nodes and 56 edges (Fig. 9D).

After calculating MCC of nodes in the original PPI network by CytoHubba, a core network consisting of the top 12 nodes with the greatest MCC values was visualized in a new core network (Fig. 9E).

Module analysis was performed using MCODE. 3 clusters were identified from the original PPI network with score of 11.14, 4.33, and 3.33, respectively (Fig. 9F–H).

To better analyze the PPI networks and the hub genes, node degree distribution of PPI networks in Fig. 9B–H and the degree values of proteins from core PPI networks in Fig. 9D–F were also calculated and displayed (Fig. S6K-T).

To search for hub targets in CEP against COVID-19, we took the union of target genes of three core networks in Fig. 9D–F and 19 hub genes were obtained (Table 1 ). Given that ACE2 is a functional receptor on cell surfaces for SARS-CoV-2 [44,45], ACE2 is also included in hub genes, thereby retrieving a total of 20 hub genes (Fig. S2E and Fig. S3F). Among them, there are 8 genes, considered central hub genes, present in 3 core networks from Fig. 9D–F at the same time. On this basis, these 8 genes (STAT1, SRC, PIK3R1, HIF1A, ESR1, ERBB2, CDC42, and BCL2L1), along with ACE2, are considered central hub genes and may play important roles in CEP against COVID-19. Specifically, SRC owns the highest degree value in the core network obtained from CytoNCA, as well as the highest MCC value, indicating that SRC is of great importance in CEP against COVID-19.

Table 1.

Information on hub genes of CEP and COVID-19.

| Hub genes | Degree in CytoNCA-based core network | MCC value | Source networks |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRC | 11 | 291010 | CytoNCA core network, CytoHubba core network, MCODE cluster1 |

| ESR1 | 11 | 185100 | CytoNCA core network, CytoHubba core network, MCODE cluster1 |

| HIF1A | 10 | 154382 | CytoNCA core network, CytoHubba core network, MCODE cluster1 |

| STAT1 | 10 | 106965 | CytoNCA core network, CytoHubba core network, MCODE cluster1 |

| PIK3R1 | 8 | 134282 | CytoNCA core network, CytoHubba core network, MCODE cluster1 |

| ERBB2 | 9 | 278064 | CytoNCA core network, CytoHubba core network, MCODE Cluster1 |

| CDC42 | 8 | 140991 | CytoNCA core network, CytoHubba core network, MCODE Cluster1 |

| BCL2L1 | 8 | 114178 | CytoNCA core network, CytoHubba core network, MCODE Cluster1 |

| EGFR | 10 | 203657 | CytoNCA core network, CytoHubba core network |

| GSK3B | 10 | 87722 | CytoNCA core network, MCODE Cluster1 |

| PTK2 | / | 247350 | CytoHubba core network, MCODE Cluster1 |

| IGF1R | / | 171390 | CytoHubba core network, MCODE Cluster1 |

| PRKCA | 8 | 5114 | CytoNCA core network |

| NFKB1 | 9 | 7954 | CytoNCA core network |

| MET | / | 96720 | CytoHubba core network |

| CREBBP | / | 6217 | MCODE Cluster1 |

| HSP90AB1 | / | 21640 | MCODE Cluster1 |

| PIK3CD | / | 85824 | MCODE Cluster1 |

| PIK3CB | / | 85746 | MCODE Cluster1 |

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; CEP, cepharanthine; MCC: Maximal Clique Centrality.

3.16. GO and KEGG analysis of clusters in Fig. 9F–H

In order to illustrate the functions of three clusters in Fig. 9F–H, GO and KEGG analysis of the clusters was carried out as shown in Fig. S8.

For cluster 1, most GO terms of BP are related to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling (GO:0014065), phosphatidylinositol-mediated signaling (GO:0048015), and inositol lipid-mediated signaling (GO:0048017); the main terms of CC are associated with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex (GO:0005942), extrinsic component of membrane (GO:0019898), transferase complex, and transferring phosphorus-containing groups (GO:0061695); MF enrichment is mainly involved in transcription coactivator binding (GO:0001223), insulin receptor substrate binding (GO:0043560), and RNA polymerase II-specific DNA-binding transcription factor binding (GO:0061629). The top 3 pathways are thyroid hormone signaling pathway (hsa04919), proteoglycans in cancer (hsa05205), and EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance (hsa01521).

For cluster 2, most GO terms of BP are related to response to UV-A (GO:0070141), regulation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway (GO:0008277), and positive regulation of cellular component biogenesis (GO:0044089); the main terms of CC are ruffle (GO:0001726), protein complex involved in cell adhesion (GO:0098636), and cell leading edge (GO:0031252); MF enrichment is mainly involved in protein serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase activity (GO:0004712), transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase activity (GO:0004714), and virus receptor activity (GO:0001618). The top 3 pathways are proteoglycans in cancer (hsa05205), focal adhesion (hsa04510), and microRNAs in cancer (hsa05206).

For cluster 3, most GO terms of BP are related to cold-induced thermogenesis (GO:0106106), regulation of cold-induced thermogenesis (GO:0120161), and adaptive thermogenesis (GO:1990845); the main terms of CC are transcription regulator complex (GO:0005667), RNA polymerase II transcription regulator complex (GO:0090575), and DNA repair complex (GO:1990391); MF enrichment is mainly involved in nuclear receptor activity (GO:0004879), ligand-activated transcription factor activity (GO:0098531), and nuclear receptor binding (GO:0016922). The significantly enriched pathway is PPAR signaling pathway (hsa03320).

3.17. GO analysis of 20 hub genes and targets-ontology network

In GO analysis, 18 of 20 hub target genes are significantly enriched in 1209 BP, 47 CC, and 107 MF. The top 10 significant enrichment entries of BP, CC and MF with the lowest q value are visualized in a bubble diagram and a targets-ontology network containing 48 nodes and 168 edges (Fig. 10 ).

Fig. 10.

GO enrichment analysis of 20 validated hub genes of CEP and COVID-19, including bubble diagram (A) and targets-ontology network (B).

The results revealed that the hub genes of COVID-19 and CEP are mainly enriched in positive regulation of protein kinase B signaling (GO:0051897), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling (GO:0014065), phosphatidylinositol-mediated signaling (GO:0048015), and other biological processes; in phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex (GO:0005942), extrinsic component of membrane (GO:0019898), basal plasma membrane (GO:0009925), and other cellular components; in protein tyrosine kinase activity (GO:0004713), protein phosphatase binding (GO:0019903), protein serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase activity (GO:0004712), and other molecular functions.

3.18. KEGG enrichment analysis and targets-pathways network of 20 hub genes

A total of 19 of 20 hub targets are enriched in 137 pathways, among them, the top 30 significant enrichment potential pathways are presented in a bubble diagram (Fig. 11 A) and visualized by a targets-pathways network containing 83 nodes and 354 edges (Fig. 11B).

Fig. 11.

Top 30 most significant KEGG enrichment pathways of hub validated genes of CEP and COVID-19, including the bubble diagram (A) and targets-pathways network (B).

The top 5 pathways with the highest gene counts are PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (hsa04151, n = 13, Fig. S4C), proteoglycans in cancer (hsa05205, n = 13), focal adhesion (hsa04510, n = 12), EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance (hsa01521, n = 11), and lipid and atherosclerosis (hsa05417, n = 11). Noteworthy, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway possesses the highest gene counts in the three times of KEGG analyses (KEGG analysis of 462 co-targeted genes of CEP and COVID-19, KEGG analysis of 97 validated genes of CEP and COVID-19, as well as KEGG analysis of 20 validated hub genes of CEP and COVID-19), indicating that PI3K-Akt signaling pathway could be the most important pathway in the CEP against COVID-19.

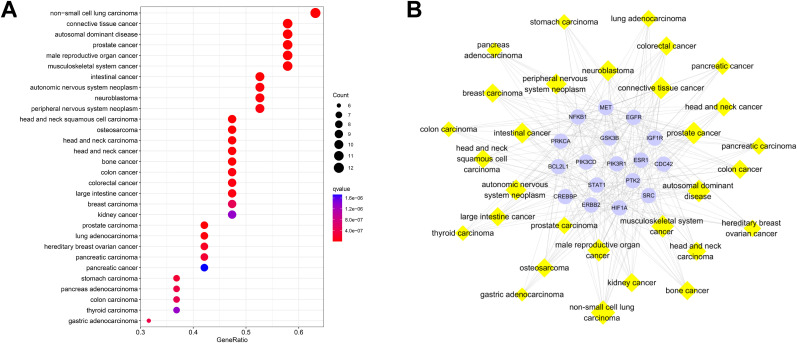

3.19. DO analysis and targets-diseases network of hub genes of CEP and COVID-19

The top 30 disease entries based on hub genes of CEP and COVID-19 according to q value are displayed in a bubble diagram (Fig. 12 A) and a targets-diseases network (Fig. 12B). The top 6 disease entries with the highest gene counts are non-small cell lung carcinoma (DO ID:3908, n = 12), connective tissue cancer (DO ID:201, n = 11), autosomal dominant disease (DO ID:0050736, n = 11), prostate cancer (DO ID:10283, n = 11), male reproductive organ cancer (DO ID:3856, n = 11), and musculoskeletal system cancer (DO ID:0060100, n = 11), indicating that these hub targets might play significant roles by targeting multi-organs thereby treating COVID-19.

Fig. 12.

DO analysis of CEP and COVID-19 including top 30 most significant diseases, including the bubble diagram (A) and targets-diseases network (B).

3.20. Molecular docking

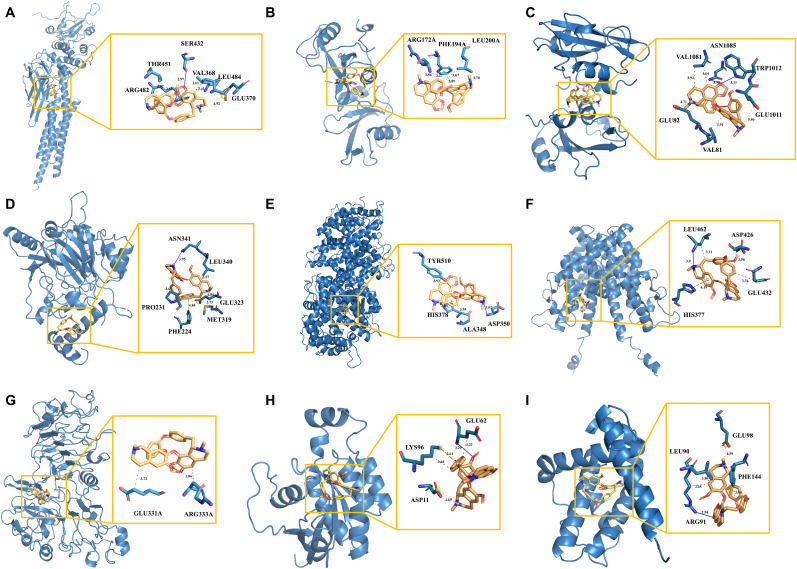

To further explore the interactions between 20 hub targets and CEP, molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina. Non-covalent interactions of 9 central hub genes with CEP were further identified (Fig. 13 and Table S5).

Fig. 13.

The molecular docking model of CEP with STAT1 (A), SRC (B), PIK3R1 (C), HIF1A (D), ACE2 (E), ESR1 (F), ERBB2 (G), CDC42 (H), and BCL2L1 (I), respectively. In the binding model, hydrophobic interactions are indicated by grey dashed lines, hydrogens bonds by navy blue solid lines, salt bridges by yellow dashed lines, π-stacking (parallel) by bright green dashed lines, π-stacking (perpendicular) by dark green dashed lines, and π-cation interactions by orange dashed lines.

For STAT1 as shown in Fig. 13A, CEP could form a hydrophobic interaction with VAL368 (length = 3.61), THR451 (length = 3.47), ARG482 (length = 3.69), and LEU484 (length = 3.41), respectively; a hydrogen bond with SER432 (length = 2.97) and ARG482 (length = 3.6), respectively; and a salt bridge with GLU370 (length = 4.92).

For SRC as shown in Fig. 13B, CEP could form a hydrophobic interaction with ARG172 (length = 3.56) and PHE194 (length = 3.47), respectively; two hydrophobic interactions with LEU200 (length = 3.67, 3.70); and a π-stacking (parallel) with PHE194 (length = 3.89).

For PIK3R1 as shown in Fig. 13C, CEP could form a hydrophobic interaction with VAL81 (length = 3.91); two hydrophobic interactions with VAL1081 (length = 3.64, 3.93); a hydrogen bond with TRP1012 (length = 3.11) and ASN1085 (length = 3.79), respectively; and a salt bridge with GLU82 (length = 4.71) and GLU1011 (length = 5.46), respectively.

For HIF1A as shown in Fig. 13D, CEP could form a hydrophobic interaction with PRO231 (length = 3.69), MET319 (length = 3.75) and LEU340 (length = 3.57), respectively; a hydrogen bond with ASN341 (length = 3.95); a π-stacking (perpendicular) with PHE224 (length = 4.84); and a salt bridge with GLU323 (length = 4.84).

For ACE2 as shown in Fig. 13E, CEP could form a hydrophobic interaction with ALA348 (length = 3.95) and TYR510 (length = 3.93), respectively; a hydrogen bond with ASP350 (length = 3.62); and a π-stacking (parallel) with HIS378 (length = 3.65).

For ESR1 as shown in Fig. 13F, CEP could form a hydrophobic interaction with GLU423 (length = 3.76), ASP426 (length = 3.96), LEU462 (length = 3.11), respectively; a hydrogen bond with LEU462 (length = 3.90); and a π-cation interaction with HIS377 (length = 4.19).

For ERBB2 as shown in Fig. 13G, CEP could form a hydrophobic interaction with GLU331 (length = 3.73) and ARG333 (length = 3.86), respectively.

For CDC42 as shown in Fig. 13H, CEP could form a hydrophobic interaction (length = 3.33) and a hydrogen bond (length = 3.29) with GLU62; a hydrophobic interaction (length = 3.64) and a π-cation interaction (length = 3.61) with LYS96; and a salt bridge with ASP11 (length = 4.65).

For BCL2L1 as shown in Fig. 13I, CEP could form a hydrophobic interaction with LEU90 (length = 3.86) and PHE144 (length = 3.95), respectively; a hydrophobic interaction (length = 3.65) and a hydrogen bond (length = 2.94) with ARG91; and a salt bridge with GLU98 (length = 4.59).

The binding affinity of docking was frequently utilized to evaluate the affinity degree of ingredients with protein targets. It is generally acknowledged that binding affinity less than −4.25 kcal/mol, −5.0 kcal/mol or −7.0 kcal/mol suggests a certain, good or strong binding activity between the ligand and the receptor, respectively. The binding affinity reflects the possibility of binding between the protein receptor and the small molecule ligand. The lower the binding energy, the higher the binding affinity, and the more stable the conformation [46,47]. Docking affinity in Table 2 suggested that the active sites of protein targets could bind well to CEP with an average binding energy of −9.14 kcal/mol. Among them, the docking of ACE2 with CEP has the lowest binding energy (−11.10 kcal/mol), indicating an extremely strong combination. Since ACE2 is the receptor protein of SARS-CoV-2 [3] and can block SARS-CoV-2 binding to target cells thereby inhibiting virus entry [48], we concluded that ACE2 plays the most important role in CEP against COVID-19 and the potential mechanism involves in the binding of ACE2 and CEP thereby blocking the binding of ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 to inhibit virus entry.

Table 2.

Molecular docking binding energy results of hub genes with CEP.

| Hub proteins | ID in PDB or AlphaFold DB | binding affinity (kcal/mol) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Original ligands | CEP | ||

| STAT1 | 1BF5 | −6.00 | −9.80 |

| SRC | 1A07 | −7.00 | −7.40 |

| PIK3R1 | 2IUI | −6.20 | −9.50 |

| HIF1A | 1H2K | −4.30 | −8.80 |

| ACE2 | 2AJF | −5.60 | −11.10 |

| ESR1 | 1A52 | −10.40 | −8.20 |

| ERBB2 | 2A91 | −6.00 | −9.70 |

| CDC42 | 7S0Y | −6.70 | −8.30 |

| BCL2L1 | 7JGW | −10.40 | −8.90 |

| EGFR | 2ITN | −7.90 | −8.70 |

| PIK3CD | 5DXU | −7.50 | −10.10 |

| PTK2 | 1MP8 | −6.90 | −8.40 |

| IGF1R | 3I81 | −7.50 | −8.90 |

| PIK3CB | AF-P42338-F1 | −7.50 | −10.70 |

| PRKCA | 3IW4 | −10.30 | −10.70 |

| NFKB1 | 2DBF | −5.50 | −7.50 |

| MET | 2RFS | −8.40 | −9.60 |

| CREBBP | 6AY3 | −8.80 | −8.80 |

| HSP90AB1 | 3NMQ | −9.20 | −8.70 |

| GSK3B | 1J1B | −7.40 | −9.00 |

CEP, cepharanthine.

3.21. MD simulation

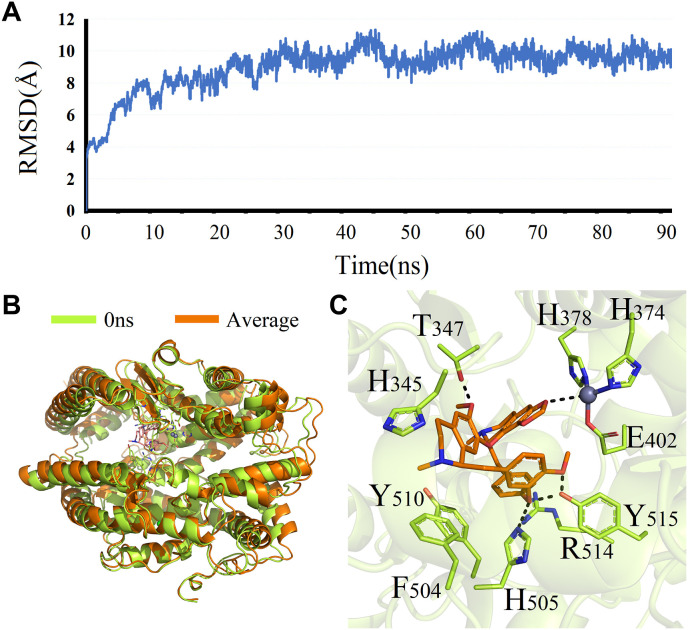

MD simulation has been widely used to evaluate the structural characteristics of the protein-ligand systems and study the binding stability between the proteins and the molecules [49]. In the present study, ACE2, considered the most important target in CEP against COVID-19, was chosen to further analyze the stability of binding to CEP. Analysis of molecular dynamics simulation results can be seen in Fig. 14 A: (1) In the range of 0–30 ns, the system of ACE2 and CEP is constantly fluctuating, suggesting that the system is unstable and is changing constantly. (2) In the range of 30–90 ns, the RMSD value has been in a stable state with little changes, revealing that the binding between ACE2 and CEP is extremely stable, and there exists a good binding state between the two systems.

Fig. 14.

The MD simulation results of ACE2 and CEP, including the RMSD of value of ACE2-CEP (A), structures of the ACE2-CEP complex system before and after simulation (B), and the binding mode of ACE2 and CEP after simulation (C).

In last, through MM-PBSA method, binding free energy was calculated using the last 10–50 ns of stable RMSD trajectorie (Fig. 14B and C). In the protein-ligand system, CEP interacts with Phe504 and Tyr510 through hydrophobic binding actions; it also interacts with Thr347, His505 and Tyr515 through polar interaction. Besides, metal ion from ACE2 forms a chelating interaction with the oxygen atom on CEP. These polar and nonpolar amino acids are able to anchor CEP well in the protein binding pocket, with the binding energy value of −9.94 kcal/mol.

Collectively, MD simulation results are consistent with the findings of molecular docking that CEP can bind well with ACE2, which is the most critical gene in CEP against COVID-19.

4. Discussion

COVID-19, a fatal pandemic, has shown a gigantic increase in incidence and mortality rates worldwide [2]. CEP, as an approved drug with a good safety profile [12], exhibits a range of promising antivirus bioactivity with IC50 values of 0.026 μM, 9.5 μg/mL, and 0.83 μM against the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 [50], severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus [13], and human coronavirus OC43 [51], respectively. Specifically, CEP's anti-SARS-CoV-2 efficacy in Calu-3 cells (IC50 = 30 μM) [52], Vero cells (IC50 = 4.47 μM) [52,53], and A549 cells (IC50 = 1.67 μM, CC50 = 30.92 μM) [23], has been reported, indicating its potential value in the treatment of COVID-19. Besides, a co-treatment comprising CEP and Trifluoperazine was proved to be highly potent against the newly emerged SARS-CoV-2 B.1.351 variant [23]. Mechanically, CEP can block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to target cells thereby inhibiting virus entry [48]. In the present study, to elucidate potential therapeutic mechanism of CEP against COVID-19, strategies of network pharmacology, RNA-sequencing analysis, molecular docking and MD simulation were jointly used. After searching public databases and related RNA-seq datasets, 700 potential targets of CEP against COVID-19 were identified, which were then validated by GSE158050 dataset to acquire 97 validated targets.

To annotate the functions of 97 validated targets and related pathways, GSEA analysis, GO analysis, KEGG pathway analysis, and DO analysis were further conducted. Notably, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, which possesses the largest gene counts in three times of KEGG enrichment analyses, appeared to be the most critical pathway involved in the treatment of COVID-19 by CEP. The PI3K-Akt signaling pathway is an important cell signaling pathway that can regulate various cell functions, including cell growth, cell differentiation, cell survival, cell proliferation, cell motility and so on [54,55].

On the one hand, numerous pieces of literature have implied the potential role of PI3K-Akt signaling pathway in COVID-19. Activation of the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway has been linked to the induction of lung tissue fibrosis in patients with COVID-19 [56,57], while the suppression of PI3K-Akt signaling pathway reduces the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α [58]. SARS-CoV-2 activates the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in Huh7 cells during the initial phases of SARS-CoV-2 infection by upregulating levels of phosphorylation of Akt, mTOR, 4 E-BP1, and S6K1 [59], while the Akt inhibitor MK-2206, the PI3K inhibitor pictilisib, the dual PI3K and mTOR inhibitor omipalisib, as well as the dual mTOR and PI3K-α/(BRD2/BRD4) inhibitor SF2523, all show significant antiviral effects on SARS-CoV-2 in vitro [[59], [60], [61]]. Besides, SARS-CoV-2 endocytosis occurs via a clathrin-mediated pathway which is regulated by the PI3K-Akt signaling [62], and the suppression of this pathway inhibits the entry of other viruses using clathrin-mediated endocytosis [63].

On the other hand, CEP has been validated to regulate PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. CEP inhibits the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway to induce cell apoptosis in cells infected by Herpes simplex virus type-1, hence further reducing virus infection and subsequent reproduction [64]. In addition, CEP can inhibit PI3K-Akt signaling pathways to inhibit bone resorption, while the inhibitory effect is partly reversed by the treatment with SC79 (an Akt agonist) in vitro [65]. What's more, the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway modification appears to play a significant role in the Jurkat T cell apoptosis induced by CEP [66]. These findings are congruent with our point that PI3K-Akt signaling pathway is the most important pathway involved in the anti-COVID-19 mechanism of CEP.

To understand protein-protein interactions, the PPI network of validated targets was constructed. Topological analysis revealed that 9 central hub genes (STAT1, SRC, PIK3R1, HIF1A, ACE2, ESR1, ERBB2, CDC42, and BCL2L1) might exert crucial effects in the anti-COVID-19 process of CEP. Among them, SRC owns the highest degree value in the core network obtained from CytoNCA, as well as the highest MCC value, suggesting that SRC might play a certain anti-COVID role in CEP. Several studies have supported our view. SRC, as a non-receptor tyrosine kinase and a member of the SRC family of kinases [67], can bind to various proteins and mediate intracellular signal transmission [68]. SRC is associated with Bovine coronavirus and implicated in other coronaviruses [69]. Besides, SRC can be activated by the progesterone receptor PGR, which further leads to the induction of antiviral genes [70]. This finding is congruent with the fact that patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 have increased progesterone levels, which are co-related to decreased severity of COVID-19 [70]. On the other hand, in human prostate cancer cells, CEP hydrochloride can mediate GPR30 [71], the activation of which has been validated to affect the activation of SRC [72]. These data further support our findings on the significance of SRC in CEP for COVID-19.

Based on the findings of network pharmacology, molecular docking was carried out to further explore the combination of 20 hub genes and CEP. Docking results showed that the combination of 20 hub genes and CEP is strong. Specifically, docking of CEP and ACE2 shows the lowest binding energy, revealing the combination is the most stable. Moreover, MD simulation also indicated the extremely stably binding between ACE2 and CEP. Given that ACE2 is the receptor protein of SARS-CoV-2 [3] and can block SARS-CoV-2 binding to target cells thereby inhibiting its entry [48], ACE2 plays the most important role in CEP against COVID-19. Besides, level of ACE2 has been reported to be regulated by CEP, thereby suggesting the possible effects of CEP during SARS-CoV-2 infection by regulating level of ACE2 [73], which is congruent with our view that ACE2 is the most important target involved in the anti-COVID-19 mechanism of CEP.

Although a series of analyses were conducted to illustrate the potential protective mechanism of CEP on COVID-19 in the present study, there are some limitations based on the corresponding guidance [74]: (1) The targets from online databases and RNA-seq datasets were based on the reviewed and documented data; thus, undocumented targets may not be included in our analysis, which acquires further research. (2) Since the therapeutic effect of CEP against COVID-19 involves multi-targets and multi-pathways, other targets and pathways which haven't been emphasized also need attention and further investigation. (3) In this study, GSE158050 dataset was utilized to validate potential targets of CEP and COVID-19. However, the dataset used GX_P2V model (SARS-CoV-2-related pangolin coronavirus model) in Vero E6 cells (derived from the kidney of an African green monkey kidney) to study the potential mechanism of CEP against COVID-19; therefore, human cells infected by SARS-CoV-2 and clinical trials should be conducted in the future. (4) Though CEP is a clinically approved drug with a long-established excellent safety profile [12], the efficacy and security of CEP in treating patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection still require careful evaluation.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, we firstly performed strategies of network pharmacology and RNA-seq to illustrate that ACE2 is the most important target, and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway is the most crucial pathway. Additionally, molecular docking analysis validated the prediction by the network pharmacology-based method. Besides, MD simulation was carried out to further evaluate the structural characteristics and simulate the binding stability of CEP and ACE2. Based on a multidisciplinary strategy, our study provides evidence for exploring the potential protective mechanism of CEP in COVID-19, as well as a comprehensive and innovative approach to search for core targets and potential molecular mechanisms in drug discovery.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants of the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (Nos. 82173911, 81973406), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University (Nos. 2022ZZTS0954, 2022ZZTS0243), Hunan Provincial Natural Scientific Foundation (Nos. 2019JJ50849, 2020JJ4823, 2022JJ80109), Scientific Research Project of Hunan Provincial Health and Family Planning Commission (No. 202113050843), and Research Project established by Chinese Pharmaceutical Association Hospital Pharmacy department (No. CPA-Z05-ZC-2021-002).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106298.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. Feb 20 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velavan T.P., Meyer C.G. The COVID-19 epidemic. Trop. Med. Int. Health. Mar 2020;25(3):278–280. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. Apr 16 2020;181(2):271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozturk T., Talo M., Yildirim E.A., Baloglu U.B., Yildirim O., Rajendra Acharya U. Automated detection of COVID-19 cases using deep neural networks with X-ray images. Comput. Biol. Med. Jun 2020;121 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders J.M., Monogue M.L., Jodlowski T.Z., Cutrell J.B. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. May 12 2020;323(18):1824–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Yozbaki M., Wilkin P.J., Gupta G.K., Wilson C.M. Therapeutic potential of natural compounds in lung cancer. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021;28(39):7988–8002. doi: 10.2174/0929867328666210322103906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo H., Vong C.T., Chen H., et al. Naturally occurring anti-cancer compounds: shining from Chinese herbal medicine. Chin. Med. 2019;14:48. doi: 10.1186/s13020-019-0270-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehta J., Rayalam S., Wang X. Cytoprotective effects of natural compounds against oxidative stress. Antioxidants. Oct 20 2018;7(10) doi: 10.3390/antiox7100147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu H., Qiu Y., Tasneem S., et al. Advancement of natural compounds as anti-rheumatoid arthritis agents: a focus on their mechanism of actions. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2021;21(19):2957–2975. doi: 10.2174/1389557521666210304112916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Y., Islam M.S., Wang J., Li Y., Chen X. Traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of patients infected with 2019-new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): a review and perspective. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16(10):1708–1717. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogosnitzky M., Danks R. Therapeutic potential of the biscoclaurine alkaloid, cepharanthine, for a range of clinical conditions. Pharmacol. Rep. 2011;63(2):337–347. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70500-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manske R.H.F., Holmes H.L. Elsevier; 2014. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Physiology. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang C.H., Wang Y.F., Liu X.J., et al. Antiviral activity of cepharanthine against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in vitro. Chin. Med. J. Mar 20 2005;118(6):493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailly C. Cepharanthine: an update of its mode of action, pharmacological properties and medical applications. Phytomedicine. Sep 2019;62 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.152956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drayman N., DeMarco J.K., Jones K.A., et al. Masitinib is a broad coronavirus 3CL inhibitor that blocks replication of SARS-CoV-2. Science. Aug 20 2021;373(6557):931–936. doi: 10.1126/science.abg5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong Y, Fan H, Song L, et al, Inventors; Pangolin Coronavirus xCoV and its Application, and the Application of Drugs against Coronavirus Infection. patent CN113046327B.

- 17.Liu X. Jinan University; Jinan: 2004. Studies on the Immune Evaluation of Inactivated SARS-CoV Experimental Vaccine and the Screening of Antiviral Drugs in Vitro. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Z., Chen B., Chen S., et al. Applications of network pharmacology in traditional Chinese medicine research. Evid. Based Compl. Alternat. Med. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/1646905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong M., Tao S., Zhang L., et al. RNA sequencing: new technologies and applications in cancer research. J. Hematol. Oncol. Dec 4 2020;13(1):166. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-01005-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinzi L., Rastelli G. Molecular docking: shifting paradigms in drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. Sep 4 2019;(18):20. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X., Xu L.Y., Li E.M., Dong G. Application of molecular dynamics simulation in biomedicine. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. May 2022;99(5):789–800. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.14038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UniProt A worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. Jan 8 2019;47(D1):D506–D515. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang S., Huang W., Ren L., et al. Comparison of viral RNA-host protein interactomes across pathogenic RNA viruses informs rapid antiviral drug discovery for SARS-CoV-2. Cell Res. Jan 2022;32(1):9–23. doi: 10.1038/s41422-021-00581-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett T., Wilhite S.E., Ledoux P., et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets--update. Nucleic Acids Res. Jan 2013;41(Database issue):D991–D995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant R.A., Morales-Nebreda L., Markov N.S., et al. Circuits between infected macrophages and T cells in SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Nature. Feb 2021;590(7847):635–641. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03148-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Overmyer K.A., Shishkova E., Miller I.J., et al. Large-scale multi-omic analysis of COVID-19 severity. Cell Syst. Jan 20 2021;12(1):23–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2020.10.003. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S., Liu W., Chen Y., et al. Transcriptome analysis of cepharanthine against a SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus. Briefings Bioinf. Mar 22 2021;22(2):1378–1386. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng X.Y., Zhang H.X., Mezei M., Cui M. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. Jun 2011;7(2):146–157. doi: 10.2174/157340911795677602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.López-Vallejo F., Caulfield T., Martínez-Mayorga K., et al. Integrating virtual screening and combinatorial chemistry for accelerated drug discovery. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. Jul 2011;14(6):475–487. doi: 10.2174/138620711795767866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. Jan 30 2010;31(2):455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clyne A., Yang L., Yang M., May B., Yang A.W.H. Molecular docking and network connections of active compounds from the classical herbal formula Ding Chuan Tang. PeerJ. 2020;8 doi: 10.7717/peerj.8685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., et al. The protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. Jan 1 2000;28(1):235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varadi M., Anyango S., Deshpande M., et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. Jan 7 2022;50(D1):D439–d444. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salentin S., Schreiber S., Haupt V.J., Adasme M.F., Schroeder M. PLIP: fully automated protein-ligand interaction profiler. Nucleic Acids Res. Jul 1 2015;43(W1):W443–W447. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez X., Krone M., Alharbi N., et al. Molecular graphics: bridging structural biologists and computer scientists. Structure. Nov 5 2019;27(11):1617–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amber v. Vol. 16. University of California; San Francisco: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xue W., Wang P., Tu G., et al. Computational identification of the binding mechanism of a triple reuptake inhibitor amitifadine for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. Feb 28 2018;20(9):6606–6616. doi: 10.1039/c7cp07869b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darden Tom, York Darrin, Pedersen Lee. Particle mesh Ewald: an N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98(12):10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kollman P.A., Massova I., Reyes C., et al. Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: combining molecular mechanics and continuum models. Acc. Chem. Res. Dec 2000;33(12):889–897. doi: 10.1021/ar000033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lam T.T., Jia N., Zhang Y.W., et al. Identifying SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature. Jul 2020;583(7815):282–285. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fan H.H., Wang L.Q., Liu W.L., et al. Repurposing of clinically approved drugs for treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 in a 2019-novel coronavirus-related coronavirus model. Chin. Med. J. May 5 2020;133(9):1051–1056. doi: 10.1097/cm9.0000000000000797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. Oct 25 2005;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schriml L.M., Munro J.B., Schor M., et al. The human disease ontology 2022 update. Nucleic Acids Res. Jan 7 2022;50(D1):D1255–d1261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simmons G., Zmora P., Gierer S., Heurich A., Pöhlmann S. Proteolytic activation of the SARS-coronavirus spike protein: cutting enzymes at the cutting edge of antiviral research. Antivir. Res. Dec 2013;100(3):605–614. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuba K., Imai Y., Rao S., et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat. Med. Aug 2005;11(8):875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu J., Liu J., Tong X., et al. Network pharmacology prediction and molecular docking-based strategy to discover the potential pharmacological mechanism of huai hua san against ulcerative colitis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021;15:3255–3276. doi: 10.2147/dddt.S319786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chao P., Lin-lin S., Jing L., Hui-bin S., Jun F. Study on the mechanism of Carthami Flos in treating retinal vein occlusion based on network pharmacology and molecular docking technology. Natural Product Research and Development. 2020;32(11):1844. doi: 10.16333/j.1001-6880.2020.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohashi H., Watashi K., Saso W., et al. Potential anti-COVID-19 agents, cepharanthine and nelfinavir, and their usage for combination treatment. iScience. Apr 23 2021;24(4) doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tutone M., Virzì A., Almerico A.M. Reverse screening on indicaxanthin from Opuntia ficus-indica as natural chemoactive and chemopreventive agent. J. Theor. Biol. Oct 14 2018;455:147–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okamoto M., Ono M., Baba M. Potent inhibition of HIV type 1 replication by an antiinflammatory alkaloid, cepharanthine, in chronically infected monocytic cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. Sep 20 1998;14(14):1239–1245. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim D.E., Min J.S., Jang M.S., et al. Natural bis-benzylisoquinoline alkaloids-tetrandrine, fangchinoline, and cepharanthine, inhibit human coronavirus OC43 infection of MRC-5 human lung cells. Biomolecules. Nov 4 2019;9(11) doi: 10.3390/biom9110696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ko M., Jeon S., Ryu W.S., Kim S. Comparative analysis of antiviral efficacy of FDA-approved drugs against SARS-CoV-2 in human lung cells: nafamostat is the most potent antiviral drug candidate. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.12.090035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeon S., Ko M., Lee J., et al. Identification of antiviral drug candidates against SARS-CoV-2 from FDA-approved drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. Jun 23 2020;(7):64. doi: 10.1128/aac.00819-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu G.Y., Sabatini D.M. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. Apr 2020;21(4):183–203. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0199-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]