Abstract

Background:

Recent studies show that computer-based training enhances cognition in schizophrenia; furthermore, socialization has also been found to improve cognitive functions. It is generally believed that non-social cognitive remediation using computer exercises would be a pre-requisite for therapeutic benefits from social cognitive training. However, it is also possible that social interaction by itself enhances non-social cognitive functions; this possibility has scarcely been explored in schizophrenia patients. This pilot study examined the effects of computer-based neurocognitive training, along with social interaction either with a peer (PSI) or without one (N-PSI). We hypothesized that PSI will enhance cognitive performance during computerized exercises in schizophrenia, as compared with N-PSI.

Methods:

Sixteen adult participants diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder participating in an ongoing trial of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy completed several computerized neurocognitive remediation training sessions (the Orientation Remedial Module©, or ORM), either with a peer or without a peer.

Results:

We observed a significant interaction between the effect of PSI and performance on the different cognitive exercises (p < 0.05). More precisely, when patients performed the session with PSI, they demonstrated better cognitive performances than with N-PSI in the ORM exercise that provides training in processing speed, alertness, and reaction time (the standard Attention Reaction Conditioner, or ARC) (p < 0.01, corrected). PSI did not significantly affect other cognitive domains such as target detection and spatial attention.

Conclusion:

Our findings suggest that PSI could improve cognitive performance, such as processing speed, during computerized cognitive training in schizophrenia. Additional studies investigating the effect of PSI during cognitive remediation are needed to further evaluate this hypothesis.

Keywords: Cognitive remediation, Schizophrenia, Mental health, Social interaction, Psychosis, Computerized interventions

1. Introduction

Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia are among the most robust features of the illness and strongly predict outcome (Green et al., 2000; Stone and Seidman, 2016). Impairments in social cognition, such as processing emotions (Hooker and Park, 2002; Mueser et al., 1996; Penn and Mueser, 1996), social perception and knowledge (Corrigan and Nelson, 1998; Penn et al., 2002), and theory of mind (Sprong et al., 2007), are robust as well. Impaired neurocognitive and social-cognitive abilities are also related with poorer social functioning in individuals with schizophrenia (Brekke et al., 2007; Isaac and Januel, 2016; Kurtz et al., 2015; Penadés and Gastó, 2014). Hence, the remediation of these cognitive and social deficits is critical for optimal community functioning and for these individuals.

Over the last two decades, growing efforts to ameliorate cognitive deficits in schizophrenia have included computer-based neurocognitive training (CBNT) protocols. Cognitive domains most often treated with CBNT include attention, working memory, verbal declarative memory and learning, and processing speed. There is now increasing evidence that cognitive performances across these domains improved significantly following various computer-assisted neurocognitive remediation programs (Cochet et al., 2006; d'Amato et al., 2011; Dellagi et al., 2009; Hodge et al., 2008; Ikezawa et al., 2012; Mak et al., 2013; Marker, 1987; Sartory et al., 2005; Wykes et al., 2011).

Training programs in these studies have employed an individual and/or a group setting approach. In the interventions that opted for an individualized treatment, participants either interacted only with the computer (Fisher et al., 2009a, 2009b), were coached by a clinician throughout the training (Dickinson et al., 2009), or engaged in a combination of computerized intervention with individual coaching (Medalia et al., 1998). Group settings included interactions in smaller groups, such as triadic groups (Wölwer et al., 2005) or larger groups containing between six and ten participants (Cavallaro et al., 2009; hecardeur et al., 2009). Nonetheless, the quality and characteristics of these group interactions are not specified in these manuscripts. Finally, a new way of delivering cognitive remediation involves combining both individual and group settings, such as the Cognitive Enhancement Therapy (CET) (Eack et al., 2009, 2010; Hogarty et al., 2004), Neuropsychological Educational Approach to Remediation (NEAR) (Ikezawa et al., 2012; Medalia and Freilich, 2008), Bridging Groups (Medalia and Choi, 2009), and other interventions (Hadas-Lidor et al., 2001; Ojeda et al., 2012; Palumbo et al., 2017). While these studies report the effect on cognition following the neurocognitive therapy and/or treatment program, they do not consider the effect of having an additional group format compared to individual setting treatment.

Our study aims to precisely isolate this effect of social interaction (SI) during cognitive remediation treatment on performance in patients with schizophrenia. Our working definition of SI refers to the individuals acting on the basis of taking others' presence and actions into account (Rousseau, 2002). More generally, basic social interactions can lead to improvements in physical health (Berkman et al., 2000; House et al., 1988) and in cognition in healthy subjects (De Jaegher et al., 2010; Seeman et al., 2011; Ybarra et al., 2011). Moreover, SI is likely to promote both mental and physical health in healthy, older adults (Bassuk et al., 1999; Herzog et al., 2002; Krause et al., 1998). Nevertheless, the effects of SI on cognitive outcomes in individuals with psychosis remain largely unexplored.

CBNT studies usually attribute neurocognitive improvements solely to their computerized trainings or repetition of the task (Kurtz et al., 2007), but being in the presence of others during the training (e.g., a peer or a clinician) may also impact cognitive performance. For instance, computerized interventions for mental health problems are known to be affected by direct or indirect contact with clinicians and staff members as well (Warmerdam et al., 2008; Sandoval et al., 2017). In fact, Internet and computerized interventions combined with live therapist support (i.e., interacting with the study personnel) yield better outcomes and greater retention rates (Johansson and Andersson, 2012).

Interestingly, in the sports and exercise psychology literature, SI has been shown to affect participants' physical performance (Rhea et al., 2003; Strauss, 2002). For instance, Feltz et al. (2011) found that participants performed significantly better when they were accompanied than in the solo control condition, when using an isometric plank exergame. Similarly, Snyder et al. (2012) found that participants tend to perform better in the presence of others on simple or well-rehearsed tasks. In other words, these studies suggest that exercise behavior can be impacted by SI (Strauss, 2002).

In this context, the current pilot study built upon previous research showing that both CBNT and SI can impact performance and cognition favorably, by assessing their combined effects in individuals with schizophrenia. The current research questions were generated when one of the investigators (LRS) noticed that peer social interaction (PSI) appeared to lead to better cognitive performance than when there was no engagement in peer social interaction (N-PSI). The aim of the study was to examine the effects of SI on cognitive performance. We hypothesized that the PSI condition drives higher cognitive performance on the computerized neurocognitive training tasks compared to the N-PSI condition.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The sixteen participants who enrolled in the study were referred by mental health programs that specialize in treating early-course schizophrenia in Boston, Massachusetts. This pilot study was embedded within a larger clinical trial called Brain Imaging, Cognitive Enhancement and Early Schizophrenia (BICEPS), which examines the effects of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy (CET) on early-course schizophrenia. The subjects who participated in this study were recruited and screened as part of the BICEPS study. The Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all procedures, and all participants provided written informed consent. Sixteen participants who met inclusion criteria (1) were 18 to 35 years of age; (2) met DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; (3) demonstrated their first psychotic episode symptoms within the last 8 years; (4) demonstrated an IQ of ≥80 on the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition (WASI-II); (5) demonstrated a 6th grade or higher reading level on the Wide Range Reading Test, Fourth Edition (WRAT-4); (6) spoke fluent English; (7) demonstrated significant social and cognitive disabilities based on the Cognitive Style and Social Cognition Eligibility Interview (Eack et al., 2009); and (8) received treatment with antipsychotic medication.

Potential subjects were excluded if they demonstrated (1) significant neurological or medical conditions that are associated with cognitive impairment, such as a seizure disorder or a traumatic brain injury; (2) persistent suicidal or homicidal behavior; (3) a substance abuse/dependence diagnosis within the past 3 months (other than nicotine or caffeine); and (4) MRI contraindications such as ferromagnetic objects in the body and those people too large to fit into the scanner.

2.2. Baseline measures

The Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) battery was used to assess cognition in adults with schizophrenia and related disorders. The WASI-II (Memory Scale Story Recall Part I and II) was also included in the battery. To measure the subjects' IQ values, the study used WASI-II (to estimate current intellectual functioning) and the WRAT (to estimate premorbid intellectual functioning). Participants' cognitive styles were determined through a semi-structured interview (conducted by trained clinicians) that assessed cognitive impairments, functional disability, and social handicap (Hogarty and Greenwald, 2006). This evaluation served as a clinical tool to pair subjects for the neurocognitive training.

2.3. Cognitive Enhancement Therapy (CET)

Cognitive Enhancement Therapy (CET) is a comprehensive evidence-based psychosocial intervention used for the remediation of neuro- and socio-cognitive functions in patients with schizophrenia (Hogarty and Greenwald, 2006). CET consists of three components: individual sessions, CBNT, and group sessions (Hogarty and Greenwald, 2006). The scope of this investigation solely includes the performance on CBNT.

2.4. Computer-based neurocognitive training (CBNT)

The Orientation Remedial Module© (ORM) is a computer-based neurocognitive training program designed by Ben-Yishay et al. (1979) and Ben-Yishay (1983). The ORM consists of various computerized exercises designed to gradually improve aspects of alertness, attention, concentration, vigilance, persistence, and processing speed (Meier et al., 1987). This software has also been used to improve cognitive functions in patients with schizophrenia (Eack et al., 2009, 2010). We focused on seven exercises included in three modules of the ORM training suite: Attention Reaction Conditioner (ARC), Zeroing Accuracy Conditioner (ZAC), and Time Estimation (TE) (Eack et al., 2009; Piasetsky et al., 1983).

The aim of the ARC module is to improve attention, alertness, and reaction time by fostering the ability to rely on internal cues to respond to external stimuli (Piasetsky et al., 1983). This module has standard and advanced exercises. The ZAC neurocognitive training module was designed to improve spatial attention and spatial memory (Hogarty and Greenwald, 2006). The module encompasses three different exercise types that require subjects to modulate both duration of spatial attention (ZAC short vs. ZAC long) and visual flexibility (ZAC advanced). The TE module seeks to improve vigilance by requiring subjects to maintain focus and attention on auditory and visual cues for prolonged periods of time (Hogarty and Greenwald, 2006). The standard exercise requires subjects to estimate a shorter duration than the advanced exercise.

Each neurocognitive training module has a set of exercises (i.e., standard, short, long and advanced), which in turn have different levels of difficulty. The overall aim of these three modules is to improve the trainee's capacity for attention. Subjects began with the ARC, followed by the ZAC and the TE. Exercises were adjusted in difficulty according to user performance to maintain a minimum performance rate of 75% correct. Subjects progressed to the next level of difficulty when they reached this minimum performance rate. The performance scoring ranged from 0 to 100% (Hogarty and Greenwald, 2006). Additional details on the CBNT are described in Appendix B.

2.5. Social interaction conditions

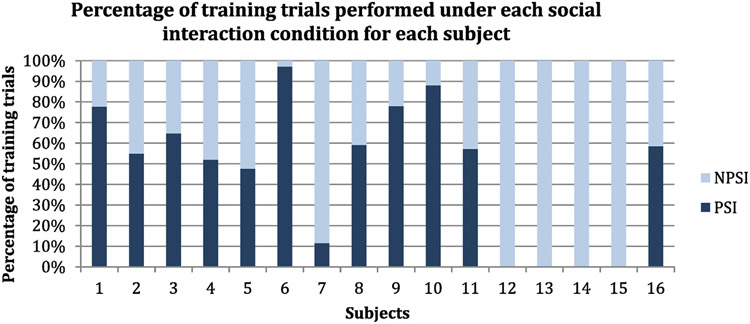

Participants performed the computerized exercises under two different SI conditions: with a peer (PSI) and without a peer (N-PSI). Seventy-five percent of the subjects experienced both SI conditions during the CBNT (mean = 62.2% PSI, median = 58.8% PSI, SD = 22.1%, variance = 4.9%, range = 85.6%); see Fig. 1. Whether a participant partook in PSI or N-PSI depended on whether the peer attended the session. If the peer was absent, the participant performed the training with the clinician (N-PSI). Four participants could not complete the computerized exercises with a partner due to attrition.

Fig. 1.

At each ORM training session, the subject completed the training either accompanied by a peer (PSI) or without a peer (N-PSI). This graph shows the percentage of training trials that each subject completed with PSI or N-PSI.

2.5.1. Peer social interaction (PSI)

The first social condition included two subjects (S1 and S2) and the clinician. In this manner, the subjects worked as a pair during the CBNT. To facilitate the formation of pairs, subjects were matched on their MATRICS overall cognitive scores and their cognitive styles (Hogarty and Greenwald, 2006).

The sessions were structured according to the CET manual (Hogarty and Greenwald, 2006). In the first phase (25 min) of the session, S1 started the CBNT exercises while S2 kept track of S1’s scores. When S1 finished this phase, S2’s training began and S1 kept track of S2’s scores (Hogarty and Greenwald, 2006). In each case, the subject who kept track of the scores was also instructed to encourage his or her training partner. After S1 and S2 completed the first phase, they were encouraged to talk freely with each other about any desirable topic for a period of 10 min, without the participation of the clinician. In this phase, the clinician only intervened to encourage a different topic if the conversation moved towards a topic that could elicit clinical vulnerability, such as talking about severe trauma. The second phase began immediately following the social interaction break and was identical to the first one.

2.5.2. No-peer social interaction (N-PSI)

The second social condition happened when one of the two subjects did not attend the session. In this instance, the clinician kept track of the subject's scores and provided encouragement in the first phase of the session. Next, the subject took a ten-minute break during which he/she was left to his/her own devices (i.e., seek refreshments, etc.). In the second phase, the clinician then again kept track of scores and provided encouragement. This modality is usually the standard procedure for individualized settings in CBNT.

2.6. Statistical analyses

2.6.1. Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics were generated to determine whether the data met the assumptions of normality and to check for the presence of outliers.

2.6.2. Peer social interaction statistics

Analyses focused on the cognitive performances during training trials that each participant did during the CBNT; therefore, the main outcome variable was the accuracy in these exercises. Together, subjects produced a total of 2317 observations that were included in the statistical model (1144 under PSI condition and 1173 under N-PSI condition). Each observation consisted of one training trial from the ORM suite. A linear mixed effects model analysis was used to assess (1) the main effect of the social interaction conditions (PSI and N-PSI) and (2) the interaction between social interaction conditions (PSI and N-PSI) and Module on the subject's performance/accuracy (the dependent variable). Module refers to the cognitive exercise (ARC, ZAC, or TE). This statistical design included the level of difficulty of the exercises (i.e., easy, moderate, and hard) as a covariate, as well as subject identification as a random factor to account for individual differences in the number of observations. Additionally, we performed post-hoc analyses to test if the effect of the therapist and/or the consistency of the partner affected the results, by adding these variables as covariates to the model. To investigate specific differences arising from significant interactions, post hoc pairwise comparisons were then performed on the adjusted mean, using the Bonferroni method to correct for multiple comparisons, maintaining the alpha level at the corrected p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 statistical software.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive results

Table 1 illustrates the demographics for the 16 participants who took part of the study.

Table 1.

Study's descriptive demographics.

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 15 | 92% |

| Female | 1 | 8% | |

| Race | Caucasian | 6 | 38% |

| African American | 3 | 19% | |

| African Caribbean | 3 | 19% | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 | 13% | |

| Middle Eastern | 1 | 6% | |

| East Asia | 1 | 6% | |

| Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 24.31 | 3.34 | |

| IQ (WRAT) | 110.75 | 8.89 | |

| # of psych hospitalization | 3.5 | 3.1 | |

3.2. Peer social interaction results

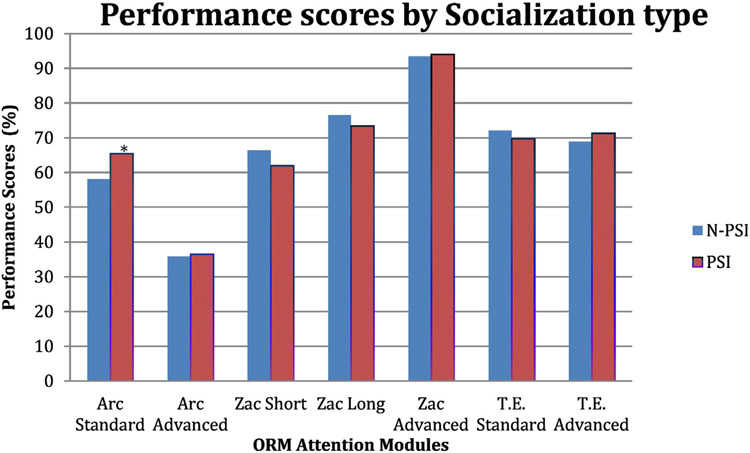

We observed a significant interaction between the social interaction conditions and the different cognitive exercises that the subjects performed during the CBNT (F = 2.12, p = 0.048). Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that PSI had a significant positive effect on performance, but only on the standard exercise of the ARC module. In the ARC standard exercise, the PSI (adjusted mean of percentage accuracy = 65.40) was significantly higher than the N-PSI (adjusted mean = 58.01), p = 0.009, 95% CI = −12.97 to −1.81 (see Fig. 2). There were no statistically significant effects of PSI on other cognitive exercises or significant overall main effect of PSI on global performance (F = 0.019, p = 0.89) (see Table 2 in Appendix A).

Fig. 2.

Mean performance scores (adjusted for the level of difficulty) for each social interaction conditions on the ORM training. PSI = peer social interaction, N-PSI = no-peer social interaction. *The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

We performed post-hoc analysis including the therapist as a covariate in the model, to ensure that the effect of PSI was not affected by the possible variability between the therapists. We did not observe any main effects of therapist on the performance (F = 0.397, p = 0.538), and the interaction between PSI condition and exercise module remained significant (F = 2.125, p = 0.048), showing that PSI improved performance for the standard exercise of the ARC module, compared to the other exercises (p = 0.010, Bonferroni corrected).

Furthermore, to rule out the effects of treatment consistency attributable to partner attendance across CBNT sessions, consistency of partner attendance was entered as an additional covariate. Treatment consistency was defined as the total proportion of training trials that were in the PSI condition (where the partner was present). For patients who never had a CBNT partner, treatment consistency was defined as 100%. Treatment consistency was not a significant covariate (F = 0.499, p = 0.491), and the interaction between the PSI condition and exercise module remained significant (F = 2.127, p = 0.047). Therefore, PSI led to better performance in the ARC training, even after accounting for the differences in partner attendance (p = 0.008, Bonferroni corrected).

4. Discussion

This pilot study investigated the impact of social interaction among peers on performance during computerized training that targets selected cognitive domains (alertness, reaction time, spatial attention and memory, processing speed, and vigilance). To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to provide preliminary evidence of the positive effects of SI during CBNT in people with schizophrenia. Interestingly, training on the standard exercise of the ARC module was associated with greater neurocognitive progress when the CBNT was combined with PSI, as opposed to doing the training without peer interaction. Our findings show that PSI resulted in better cognitive performance, but specifically on the exercise targeting alertness, processing speed, and reaction time, even after controlling for therapist and treatment consistency attributable to partner attendance. The difference in cognitive performance, based partly on the cognitive domain and partly on whether or not the social interaction occurred with a peer, suggests that PSI by itself may be a moderating factor in the degree of success achieved during neurocognitive rehabilitation in these schizophrenia subjects.

Previous CBNT studies have shown improvements in attention, reaction time, and processing speed (Cochet et al., 2006; Eack et al., 2009; Medalia et al., 2002; Mohammadi et al., 2014; Sartory et al., 2005); however, our findings move beyond these studies by paying greater attention to the factor of social interaction as one of the principal elements that could impact cognitive performance in schizophrenia. Our results suggest that patients with schizophrenia can be particularly well-suited to promote improvement of their peers in attention, reaction time, alertness, and processing speed. One possible explanation is that in some cases, peers with similar clinical conditions could potentially engender mutual cognitive improvement, as they understand one another's line of reasoning (Heinssen and Cuthbert, 2001; Lee, 1966). In fact, the unstructured nature of the peer interaction scheme in this study allowed it to occur according to the patients' abilities and levels of comfort. Our results also indicated that PSI was not statistically different than N-PSI for improving other cognitive abilities (i.e., vigilance, spatial attention). Perhaps social interaction is not helpful in these cognitive domains, or this might also be an effect of insufficient training time given for these cognitive domains (Fisher et al., 2009a). It is also possible that PSI could differently affect learning and performance in persons who prefer to work individually. Future studies using more powerful designs may resolve this issue.

Nonetheless, PSI seems to positively impact the exercise that targets attention, reaction time, and processing speed. Interestingly, previous studies showed that improvement on processing speed can also affect other cognitive domains eventually. For example, patients with schizophrenia who underwent intensive training using a computer-based remediation software that focuses on processing speed showed significant improvements in higher order cognitive performance, as well as neurobiological adaptation and restorations of neural system functions (Adcock et al., 2009). Another study by Murthy et al. (2012) reported that patients with schizophrenia who improved auditory processing speed showed larger gains in cognition. In this context, if future research continues to show that PSI can enhance performance on processing speed and reaction tasks, the combined effect of PSI with CBNT may improve neuro-cognition after the training. This provides a lead for an important new line of research in cognitive remediation that could explore, for example, to what extent could social interactions impact neuro- and social-cognitive domains as well as functional outcomes (i.e., employment).

Furthermore, such inquiry prompts the exploration of various types of social interaction (e.g., with peers and/or clinicians, individually, or in a group format) on cognitive remediation in varying clinical contexts (such as outpatient, inpatient, partial hospitals, or group homes), as previously suggested by McGurk et al. (2007). Moreover, it would be of great interest to better understand how these types of interaction and settings might affect patients' abilities to recognize and manage their emotions and enhance their socialization skills (i.e., develop, maintain, and sustain a social network). Our findings also encourage the integration of a social psychological approach into cognitive remediation clinical paradigms. Future studies should investigate how combining different types of social interactional modalities (e.g., clinician, peer, or group interaction) with various cognitive remediation models (top-down or bottom-up dimension of cognitive remediation) affects neuro- and socio-cognition in patients with schizophrenia.

5. Limitations

This study is a pilot investigation of the effect of social interaction among peers during CBNT, and our sample is limited to early schizophrenia patients who are psychiatrically stable. Thus, our results should be appraised in this context. Furthermore, it is important to specify that the social interaction conditions were not a controlled variable in the original study design. The effect of PSI and N-PSI on the scores was noted through clinical observations a posteriori, during the course of a larger study on cognitive enhancement therapy for early schizophrenia. This explained the variability between the number of trials that were done with or without a peer for each subject (see Fig. 1). However, to minimize the effects of this variability, the subject was included as a random factor in the model.

Additionally, observation and tracking of partner performance may have contributed to improved CBNT performance in the PSI condition compared to the N-PSI condition as it was always combined with the social interaction with the peer. To rule out this possibility, participants should provide similar feedback to the clinician performing CBNT in the N-PSI condition as well. While we controlled for the individual differences in our current statistical model, future studies should be performed with an a priori control group or within-subject controlled design, to isolate the impact of PSI.

Moreover, it remains unclear if our results are generalizable to cognitive abilities that were not subject to the actual remediation program and that could be measured through standardized neurocognitive batteries such as the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery. Finally, the potential long-term effect of PSI on neuro- and socio-cognition remains to be explored.

6. Conclusions

The results from this pilot study provide preliminary evidence that PSI may have a positive effect in processing speed and reaction time tasks in patients with early-course schizophrenia. To date, no study has directly investigated this phenomenon. While there are several evidence-based treatments for cognitive and social deficits associated with schizophrenia, none to our knowledge have specifically encouraged social interaction with computerized training. The current findings represent a potential strategy for facilitating cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. It will be important to evaluate this hypothesis through larger trials with larger groups, longer follow-up assessment periods, larger and more heterogeneous patient samples, and control conditions that minimize socialization. Furthermore, it would be interesting to investigate if implementing a social interaction approach (i.e., alone, with a virtual partner, in pairs, small groups, or with a clinician) within the clinical practice could moderate outcomes and maybe even improve long-term cognitive abilities in patients with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgment

We want to thank Rosa Johnson, Jerred Endsley and Alyssa Alfieri for their clinical input in this study. Similarly, we want to thank Glenn Jacobs, Ph.D. for his editorial assistance and the analysis of social interaction.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by NIMH grant MH 92440 (MSK).

Appendix A

Table 2.

Mean performance scores (adjusted for the level of difficulty) for each cognitive module exercises and social interaction conditions.

| N-PSI | PSI | SE | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arc Standard | 58.02** | 65.41** | 2.85 | 0.01** | −12.97 | −1.81 |

| Arc Advanced | 35.82 | 36.47 | 1.81 | 0.72 | −4.21 | 2.90 |

| Zac Short | 66.39 | 61.92 | 2.46 | 0.17 | −0.35 | 9.30 |

| Zac Long | 76.53 | 73.39 | 2.78 | 0.26 | −2.32 | 8.58 |

| Zac Advanced | 93.48 | 94.04 | 1.66 | 0.74 | −3.81 | 2.69 |

| T.E. Standard | 72.05 | 69.70 | 3.16 | 0.46 | −3.84 | 8.54 |

| T.E. Advanced | 68.90 | 71.29 | 2.98 | 0.42 | −8.23 | 3.45 |

PSI = peer social interaction, N-PSI = no-peer social interaction, SE = standard error, p = p-value, CI = confidence interval.

p < 0.05 Bonferroni corrected.

Appendix B. ORM modules description

Attention Reaction Conditioner (ARC) module

The screen shows a pyramid of nine circles with a smaller circle located at the center and bottom of the pyramid. This smaller circle serves as the stimulus: when it lights up, it prompts the subject to press the space bar. The nine larger circles then provide feedback of the subject's reaction time during the task. In the Standard exercise, the participant is trained to react to a visual and auditory stimulus within 300 ms, while in the Advanced exercise the participant is trained to react to the same stimulus within 170 ms.

Zero Accuracy Conditioner (ZAC) module

The computer screen shows a clock-like, numberless figure with a single sweep hand. The “clock” has four markings (north, south, east, and west) and 28 smaller markings in between the four main markings. The sweep hand moves circularly around the clock when the subject presses the spacebar, and ceases its movement when the subject releases the spacebar. The objective of the task is to stop the sweep hand at the “north” marking, which would be the 12 o'clock position on a clock.

The ZAC module is composed of three exercise types: ZAC Short, ZAC Long, and ZAC Advanced. When the subject releases the spacebar in the ZAC Short condition, the sweep hand stops moving after it has travelled 6 additional markings upon the spacebar release. In the ZAC Long condition, the hand moves an additional 14 markings before it stops. In the ZAC Advanced exercise, the release point on the clock randomly changes with each new trial.

Time Estimation (TE) module

The screen displays a clock-like figure with twelve markings, each representing a second. There are smaller markings that designate one-fifth of a second. The subject needs to estimate a certain amount of time in seconds. The time begins and stops when the spacebar is pressed. In the Standard exercise, participants have to estimate 12 s, while in the Advanced exercise participants need to estimate 25 s.

References

- Adcock R, Dale C, Fisher M, Aldebot S, Genevsky A, Simpson G, Nagarajan S, Vinogradov S, 2009. When top-down meets bottom-up: auditory training enhances verbal memory in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull 35 (6), 1132–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk S, Glass T, Berkman L, 1999. Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly persons. Ann. Intern. Med 131 (3), 165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yishay Y, 1983. Working Approaches to Remediation of Cognitive Deficits in Brain Damaged Persons (Rehabilitation Monograph No. 65). New York University Medical Center, Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yishay Y, Diller L, Rattok J, Ross B, Schaier A, Scherger P, 1979. Working Approaches to Remediation of Cognitive Deficits in Brain Damaged Persons (Supplement to Seventh Annual Workshop for Rehabilitation Professionals Department of Behavioral Science). Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman T, 2000. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med 51 (6), 843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke J, Hoe M, Long J, Green M, 2007. How neurocognition and social cognition influence functional change during community-based psychosocial rehabilitation for individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull 33 (5), 1247–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro R, Anselmetti S, Poletti S, Bechi M, Ermoli E, Cocchi F, Stratta P, Vita A, Rossi A, Smeraldi E, 2009. Computer-aided neurocognitive remediation as an enhancing strategy for schizophrenia rehabilitation. Psychiatry Res. 169 (3), 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochet A, Saoud M, Gabriele S, Broallier V, Daléry J, D'amato T, 2006. Impact de la remédiation cognitive dans la schizophrénic sur les stratégies de résolution de problèmes et l'autonomie sociale: utilisation du logiciel Rehacom®. L'Encéphale 32 (2), 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P, Nelson D, 1998. Factors that affect social cue recognition in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 78 (3), 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Amato T, Bation R, Cochet A, Jalenques I, Galland F, Giraud-Baro E, Pacaud-Troncin M, Augier-Astolfi F, Llorca P, Saoud M, Brunelin J, 2011. A randomized, controlled trial of computer-assisted cognitive remediation for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 125 (2–3), 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jaegher H, Di Paolo E, Gallagher S, 2010. Can social interaction constitute social cognition? Trends Cogn. Sci 14 (10), 441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellagi L, Ben AO, Johnson I, Kebir O, Amado I, Tabbane K, 2009. Cognitive remediation therapy in schizophrenia: a case report. La Tunisie Medicale 87 (10), 660–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Tenhula W, Morris S, Brown C, Peer J, Spencer K, Li L, Gold JM, Bellack AS, 2009. A randomized, controlled trial of computer-assisted cognitive remediation for schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 167 (2), 170–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack S, Greenwald D, Hogarty S, Cooley S, DiBarry A, Montrose D, Keshavan M, 2009. Cognitive enhancement therapy for early-course schizophrenia: effects of a two-year randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr. Serv 60 (11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack S, Greenwald D, Hogarty S, Keshavan M, 2010. One-year durability of the effects of cognitive enhancement therapy on functional outcome in early schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 120 (1–3), 210–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltz D, Kerr N, Irwin B, 2011. Buddy up: the köhler effect applied to health games. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol 33 (4), 506–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Holland C, Merzenich MM, Vinogradov S, 2009a. Using neuroplasticity based auditory training to improve verbal memory in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 166 (7), 805–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Holland C, Subramaniam K, Vinogradov S, 2009b. Neuroplasticity-based cognitive training in schizophrenia: an interim report on the effects 6 months later. Schizophr. Bull 36 (4), 869–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M, Kern R, Braff D, Mintz J, 2000. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr. Bull 26 (1), 119–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadas-Lidor N, Katz N, Tyano S, Weizman A, 2001. Effectiveness of dynamic cognitive intervention in rehabilitation of clients with schizophrenia. Clin. Rehabil 15 (4), 349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinssen R, Cuthbert B, 2001. Barriers to relationship formation in schizophrenia: implications for treatment, social recovery, and translational research. Psychiatry 64 (2), 126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog A, Ofstedal M, Wheeler L, 2002. Social engagement and its relationship to health. Clin. Geriatr. Med 18 (3), 593–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge MAR, Siciliano D, Withey P, Moss B, Moore G, Judd G, Shores EA, Harris A, 2008. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull 36 (2), 419–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, 2006. Cognitive Enhancement Therapy: The Training Manual. Hogarty G and Greenwald P. [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, Carter M, Greenwald D, Pogue-Geile M, Kechavan M, Cooley S, DiBarry AL, Garrett A, Parepally H, 2004. Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 61 (9), 866–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker C, Park S, 2002. Emotion processing and its relationship to social functioning in schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res. 112 (1), 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D, 1988. Social relationships and health. Science 241 (4865), 540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikezawa S, Mogami T, Hayami Y, Sato I, Kato T, Kimura I, Pu S, Kaneko K, Nakagome K, 2012. The pilot study of a neuropsychological educational approach to cognitive remediation for patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 195 (3), 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac C, Januel D, 2016. Neural correlates of cognitive improvements following cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: a systematic review of randomized trials. Socioaff. Neurosci. Psychol 6 (1), 30054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson R, Andersson G, 2012. Internet-based psychological treatments for depression. Expert. Rev. Neurother 12, 861–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Ellison CG, Wulff KM, 1998. Church-based emotional support, negative interaction, and psychological well-being: findings from a national sample of Presbyterians. J. Sci. Study Relig 725–741. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz MM, Seltzer JC, Shagan DS, Thime WR, Wexler BE, 2007. Computer-assisted cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: what is the active ingredient? Schizophr. Res 89 (1), 251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz MM, Mueser KT, Thime WR, Corbera S, Wexler BE, 2015. Social skills training and computer-assisted cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 162 (1), 35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecardeur L, Stip E, Giguere M, Blouin G, Rodriguez JP, Champagne-Lavau M, 2009. Effects of cognitive remediation therapies on psychotic symptoms and cognitive complaints in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a randomized study. Schizophr. Res 111 (1), 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AM, 1966. Multivalent Man. Braziller G. [Google Scholar]

- Mak M, Tybura P, Bieńikowski P, Karakiewicz B, Samochowiec J, 2013. The efficacy of cognitive neurorehabilitation with RehaCom program in schizophrenia patients. Psychiatr. Pol 47 (2), 213–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marker KR, 1987. COGPACK. The Cognitive Training Package Manual. Marker Software, Heidelberg & Ladenburg. [Google Scholar]

- McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, McHugo GJ, Mueser KT, 2007. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 164 (12), 1791–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalia A, Choi J, 2009. Cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Neuropsychol. Rev 19 (3), 353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalia A, Freilich B, 2008. The neuropsychological educational approach to cognitive remediation (NEAR) model: practice principles and outcome studies. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil 11 (2), 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Medalia A, Aluma M, Tryon W, Merriam AE, 1998. Effectiveness of attention training in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull 24 (1), 147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalia A, Revheim N, Herlands T, 2002. Remediation of Cognitive Deficits in Psychiatric Patients. A Clinician's Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Meier MJ, Benton AL, Diller LE, 1987. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi MR, Keshavarzi Z, Talepasand S, 2014. The effectiveness of computerized cognitive rehabilitation training program in improving cognitive abilities of schizophrenia clients. Iran. J. Psychiatry 9 (4), 209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Doonan R, Penn DL, Blanchard JJ, Bellack AS, Nishith P, DeLeon J, 1996. Emotion recognition and social competence in chronic schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol 105 (2), 271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy NV, Mahncke H, Wexler BE, Maruff P, Inamdar A, Zucchetto M, Lund J, Shabbir S, Shergill S, Keshavan M, Kapur S, 2012. Computerized cognitive remediation training for schizophrenia: an open label, multi-site, multinational methodology study. Schizophr. Res 139 (1), 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda N, Peña J, Bengoetxea E, García A, Sánchez P, Segarra R, Ezcurra J, Gutiérrez-Fraile M, Eguíluz JI, 2012. REHACOP: programa de rehabilitación cognitiva en psicosis. Rev. Neurol 54, 337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo D, Mucci A, Piegari G, D'Alise V, Mazza A, Galderisi S, 2017. SoCIAL–training cognition in schizophrenia: a pilot study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat 13, 1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penadés R, Gastó C, 2014. El tratamiento de rehabilitación neurocognitiva en la esquizofrenia. Herder Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Penn DL, Mueser KT, 1996. Research update on the psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 153 (5), 607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn DL, Ritchie M, Francis J, Combs D, Martin J, 2002. Social perception in schizophrenia: the role of context. Psychiatry Res. 109 (2), 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasetsky EB, Rattok J, Ben-Yishay Y, Lakin P, Ross B, Diller L, 1983. Computerized ORM: A Manual for Clinical and Research Uses. Working Approaches to Remediation of Cognitive Deficits in Brain Damaged Persons (Rehabilitation Monograph No. 66, pp. 1-40). New York University Medical Center, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Rhea MR, Landers DM, Alvar BA, Arent SM, 2003. The effects of competition and the presence of an audience on weight lifting performance. J. Strength Cond. Res 17 (2), 303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau N (Ed.), 2002. Self, Symbols, and Society: Classic Readings in Social Psychology. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval LR, Buckey JC, Ainslie R, Tombari M, Stone W, Hegel MT, 2017. Randomized controlled trial of a computerized interactive media-based problem solving treatment for depression. Behav. Ther 48 (3), 413–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartory G, Zorn C, Groetzinger G, Windgassen K, 2005. Computerized cognitive remediation improves verbal learning and processing speed in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 75 (2), 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Miller-Martinez DM, Stein Merkin S, Lachman ME, Tun PA, Karlamangla AS, 2011. Histories of social engagement and adult cognition: midlife in the US study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci 66 (supp_1), i141–i152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder AL, Anderson-Hanley C, Arciero PJ, 2012. Virtual and live social facilitation while exergaming: competitiveness moderates exercise intensity. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol 34 (2), 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprong M, Schothorst P, Vos E, Hox J, Van Engeland H, 2007. Theory of mind in schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 191 (1), 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone WS, Seidman LJ, 2016. Neuropsychological and structural neuroimaging endophenotypes in schizophrenia. Dev. Psychopathol 2, 931–965. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss B, 2002. Social facilitation in motor tasks: a review of research and theory. Psychol. Sport Exerc 3 (3), 237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Warmerdam L, van Straten A, Twisk J, Riper H, Cuijpers P, 2008. Internet-based treatment for adults with depressive symptoms: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res 10 (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wölwer W, Frommann N, Halfmann S, Piaszek A, Streit M, Gaebel W, 2005. Remediation of impairments in facial affect recognition in schizophrenia: efficacy and specificity of a new training program. Schizophr. Res 80 (2), 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, McGurk SR, Czobor P, 2011. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am. J. Psychiatry 168 (5), 472–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra O, Winkielman P, Yeh I, Burnstein E, Kavanagh L, 2011. Friends (and sometimes enemies) with cognitive benefits: what types of social interactions boost executive functioning? Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci 2 (3), 253–261. [Google Scholar]