Abstract

Purpose

Researches have shown the relevance of antioxidants in the management of several diseases. In the present study, the effects of quercetin and vitamin E were investigated on the mitochondrial functions in vivo and in silico.

Methods

Structures of quercetin and vitamin E were docked against mitochondrial Adenosine triphosphatase (mATPase), and cytochrome c cavity. Activity of liver mATPase and mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening were determined by spectrophotometry and activation of cytochrome c was examined by immunohistochemistry.

Results

The binding energy of vitamin E (−9 Kcal/mol) in mATPase cavity compares well with glibenclamide (−9.4 Kcal/mol), while quercetin had a binding energy of −7.1 Kcal/mol. Similarly, vitamin E, quercetin were bound to cytochrome c by −6.4 and − 5.5 Kcal/mol energy, while glibenclamide had −7.0 Kcal/mol binding energy. The results showed that vitamin E was more accessible to the protoporphyrin prosthetic group in cytochrome c than quercetin. In the experimental studies, it was validated that vitamin E inhibited the uncontrolled activity of mATPase in diabetic rat liver. This was also proven and tested on the liver mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening observed in diabetic rats. Further experimental assessment of these on activation of cytochrome c showed that vitamin E reduced the extent of the activation more than quercetin and glibenclamide.

Conclusion

There is a favorable protein-ligand interaction between quercetin and vitamin E in certain apoptotic proteins implicated in diabetes complications.

Keywords: Quercetin, Vitamin E, Diabetes, Mitochondria, Cytochrome C

Introduction

Natural antioxidants are important molecules that defend the body against several diseases that have caused global health challenges [1]. The potentials in these antioxidants are mainly attributable to the phytochemicals they possess [2]. These antioxidants are found in vegetables, fruits, cereals, medicinal plants among others. There is remarkable interest in the consumption of antioxidant rich diet due to risen awareness in their relevance in protection of humans and defense against numerous diseases. Therefore, research on dietary antioxidant is rising rapidly of which one of such with diverse potential is quercetin and vitamin E (Fig. 1a and b). These have shown usefulness in the mitigation of the damaging effect of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in many disease conditions [3]. Quercetin and vitamin E have shown anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, antihelmintic, anticarcinogenic, antidiabetic properties among others [4]. Several human diseases occur when there is overproduction of oxidants in the body, thereby generating a redox imbalance and eventually cell death either by necrosis or apoptosis [5]. Cell death could be either via the mitochondrial-mediated mechanism or otherwise, however, it has been shown that excessive activity of this process is deleterious and causes numerous pathologies including diabetes. Interestingly, mitochondrial-mediated cell death requires the compromise of the highly regulated mitochondrial permeability Transition (mPT) pore. The mPT pore is a porous structure found on the mitochondrion that enables the influx and efflux of tiny particles through the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) and larger particles moved through specific translocases. It has been shown that the mitochondria membrane also has a pore-forming F0F1 Adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase). Furthermore, studies have shown that a relationship exists between the mPT pore and mATPase suggesting that it may be a requirement for the pore formation. It is hypothesized that the F0F1ATPase would dissipate the generated electrochemical gradient in electron transport chain in a controlled manner to generate ATP in oxidative phosphorylation [6]. Reports have shown that the mPT pore opens when the integrity of the F0F1ATPase is compromised; this fact gives a new perspective to the molecular elucidation of the pathophysiology of diseases caused by mPT pore opening. Antioxidants have been described as molecules that help reduce the impact of ROS in the pathophysiological system with little or none side effects. In diabetes, it has been shown that the mitochondria show early pathological features, compromising the integrity of the mPT pore, thereby initiating the process of cell death [7]. Generally, treatment of diabetes is via glycemic control; however, there is an urgent need for multi-factorial approach considered now in modern therapies [8].

Fig. 1.

a Structure of quercetin; b Structure of vitamin E; Fig. 1c Measurement of the mitochondrial ATPase activity in the liver of normal and diabetic rats. NC = Normal control, NC + Q = Normal control that received quercetin, NC + G = Normal control that received glibenclamide, NC + V=Normal control that received vitamin E, DC = Diabetes control, DC + Q = Diabetic control that received quercetin, DC + G = Diabetic control that received glibenclamide, DC + V=Diabetic control that received vitamin E. * Statistical difference with normal rat, # Statistical difference with diabetic control,+ Statistical difference with all the treatment groups

It is suggested that drug development using dietary antioxidants with proven anti-apoptotic potentials targeted at regulation of the mPT pore via the mATPase activity could be an emerging solution to the search for anti-diabetic drugs. In silico method are widely accepted techniques used in development of pharmacology hypothesis and testing. These methods have been used in the identification and optimization of novel molecules to a target [9].

Methods

Chemicals

Bovine serum albumin (BSA), ethylene-bis (oxyethylenenitrilo) tetra acetic acid (EGTA),2-[4-(2-hydroxymethyl] piperazin-1 ethane sulphonic acid (HEPES) salt, thiobarbituric acid, acetic acid,sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), spermine, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), rotenone, Trizma®hydrochloride, sodium succinate, were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). Calcium chloride dehydrate, Folin-Ciocalteau reagent, were from May and Baker laboratory (USA), while mannitol and sucrose were from BDH Chemicals Ltd. (Pools, England). Cytochrome c, caspase 3 and 9 antibodies were from Elabscience laboratory (China). Other reagents used were of high analytical grade.

Animal and study design

The procedures for Animal care were in accordance with the guidelines in the Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. The experimental protocol was approved by the University of Ibadan, Animal Care and Use Research Ethics Committee. Thirty-six male Wistar albino rats were obtained from the Animal House of the Department of Vertinary Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. They were acclimatized for 2 weeks and housed in ventilated cages with 12 hours light/dark cycling and were given food and fresh water ad libitum. Eighteen rats (100 - 120 g) were divided into two groups of six rats each, allowed free access to water referred to as normal control (NC), or 10 mg/kg quercetin (Q) or 10 mg/kg vitamin E (V) orally for 4 weeks. Furthermore, eighteen rats (100 - 120 g) were intraperitoneally administered a dose of 45 mg/kg STZ [10]. After 72 hours, blood sample was obtained from the rats to assess the glucose levels and rats which have ≥250 mg/dL were considered diabetic. These were randomly divided into 3 groups of six rats each, administered water as the diabetic control (DC), 10 mg/kg each of quercetin (DC + Q) and 10 mg/kg each of vitamin E (DC + E) orally for 4 weeks. The doses of quercetin and vitamin E were based on earlier reports in rats [11, 12].

Liver mitochondrial isolation

The isolation of mitochondria using differential centrifugation as performed according to the method described by Johnson and Lardy, (1967) [13]. The rats were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, dissected, the tissue removed and briefly rinsed with the isolation buffer [210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 5 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4) and 1 mM EGTA]. This was weighed, finely minced, and homogenized in a 10% suspension of the buffer. The homogenate obtained was centrifuged twice at 2300 rpm for 5 minutes to remove cellular debris and unbroken cells. The supernatant obtained was centrifuged again at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes to obtain the mitochondria. Mitochondria pellets were washed twice with buffer [21 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4) and 0.5% BSA] at 12,000 rpm in a refrigerated centrifuge for 10 minutes. The mitochondria obtained were re-suspended in a buffer [210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, and 5 mM HEPES-KOH], dispensed as aliquots into eppendorf tubes and kept on ice for immediate use. All procedures were done at 4θC.

Measurement of mitochondrial ATPase assay

The activity of mATPase was measured as documented by Lardy and Wellman (1953) and modified by Olorunsogo et al., (1979) [14, 15]. The mitochondria used for the assay were isolated following the steps outlined in the mitochondrial isolation but for 0.25 M sucrose used as isolation buffer. Assay involving mitochondria obtained from normal control, diabetic, and treated rats were performed in a test tube containing 0.25 mM sucrose, 5 mM KCl, and 0.1 M tris-hydrochloride buffer adding up to 2 mL with distilled water as required. Thereafter, 0.01 M ATP was added to the tubes and implored into a shaker water bath. Mitochondria (0.5 mg/mL protein) were added to start the reaction and stopped by the addition of 1 mL of 10% SDS. ATP hydrolysis devoid of ATPase was assessed in a set of tubes that contained only ATP without mitochondria. While tubes with mitochondria isolated from all groups were incubated with ATP. All reaction tubes were incubated in a shaker water bath for 30 minutes at 27θC. Thereafter, 1 mL 10% SDS added sequentially, to terminate the reaction. Furthermore, 1 mL ammonium molybdate and ascorbate were added to the mixture, incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes and read in a spectrophotometer at 660 nm. The release of inorganic phosphate concentration was determined from the phosphate standard curve as described by Bassir (1963) [16].

Measurement of mitochondrial permeability transition

The integrity of the isolated mitochondria for membrane permeability transition was determined by incubating mitochondria (1 mg/mL) in a suspension buffer [220 nm mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 10 mMTris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane for heart or 5 mM HEPES-KOH for liver] containing rotenone (0.8 μM) for 3½ minutes. Afterwards, succinate (5 mM) was added and the absorbance change was monitored over a time scan of 12 minutes at 30 second interval [17]. For swelling assay, calcium chloride (12 mM) was added to induce mitochondrial swelling at 30 seconds before succinate addition. Mitochondria isolated from all groups of rats were subjected to the mPT assay, while the absorbance readings were determined at 540 nm in aspectrophotometer at 30 seconds interval for 12 minutes.

Immunohistopathological analysis of cytochrome c release

The tissues were sliced to 5 μM thick and embedded in paraffin, thereafter, rehydrated using methanol and xylene. Citrate buffer (pH 6.0) was used for heat-induced epitope retrieval for 20 minutes, followed by immersion in cold water for 10 minutes. Afterwards, the endogenous peroxidase activities in the sections were blocked with 5% H2O2 for 5 minutes. Incubation was done overnight at 4θC with 1:200 anticytochrome c monoclonal antibodies. The sections were washed and incubated again with horse-radish peroxidase labeled anti-rabbit monoclonal secondary antibodies. The binding sites were detected by 0.05% 3′-3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and counterstained by Mayer’s hematoxylin. Slides were viewed by microscopy and photographed with a digital camera.

Protein determination

The protein determination of liver mitochondria were done by the methods of Lowry et al.using BSA as standard (1951) [18].

Computational methodology

Ligand preparation

In the present study, two ligands, viz.: Quercetin (CID: 5280343) and alpha Tocopherol (CID: 14985) alongside a reference drug viz.: Glibenclimide (CID: 3488) were downloaded from the PubChem database (www.pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) in the .sdf format. These compounds were prepared to minimize the energy using AutoDock tool of PyRx after which were converted into the dockable .pdbqt format using the Open Babel interface of the PyRx software.

Protein preparation

The F-Type ATPase crystal structure and Cytochrome c solution structure were retrieved from the protein databank (www.rscb.org) having the PDB ID 4BEM and 1J3S respectively. These were pre-processed by the removal of water molecules or co-bound ligands and addition of hydrogen bonds. The proteins were converted to .pdbqt format as described by Qazi et al., [19].

Molecular docking studies

Quercetin, vitamin E and glibenclimide were docked as flexible ligands with F0F1 ATPase and Cytochrome c proteins using AutoDockVina. The binding conformation, binding energy and root mean square deviation were used to select the pose with the best interaction. The post-docking analysis was done using Chimera UCSF 1.14 and BIOVAS Discovery Studio Visualizer v21.1.0.20298 to identify the protein-ligand interactions.

Autodock calculations

AutoDock tools provides different methods used in result analysis of docking simulations like binding site visualization, binding energy, conformational similarity, inhibition constant and energy constant. The tool uses Lamarckian genetic algorithm and empirical free energy force to provide a fast prediction of conformations of the bound ligand along with their predicted free energies of association.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by one way Analysis of Variance using Graph pad prism version 5.0 software (Graph pad software, San Diego, CA, USA). Significance was estimated by Tukey post hoc test and statistical difference of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Enhanced mATPase activity is attenuated by treatment of STZ-induced diabetic rats

To understand how mPT pore influences mATPase, an ATP hydrolysis protocol was adapted simultaneously with temperature equilibration. After which inorganic phosphate released by mitochondria was determined. Using this assay, mATPase enhancement was identified as a validation of mPT pore shift. Under all conditions, aliquots of mitochondrial solution of normal rat liver showed no enhancement of mATPase activity (Fig. 1c). Similarly, administration of quercetin showed no measurable enhancement of mATPase activity when compared with normal control (Fig. 1c). However, in STZ-induced diabetic rats, isolated mitochondria enhanced mATPase activity and treatment with quercetin and vitamin E reduced this effect in liver (Fig. 1c). It was also observed that a statistical difference exist within the entire treatment regimens.

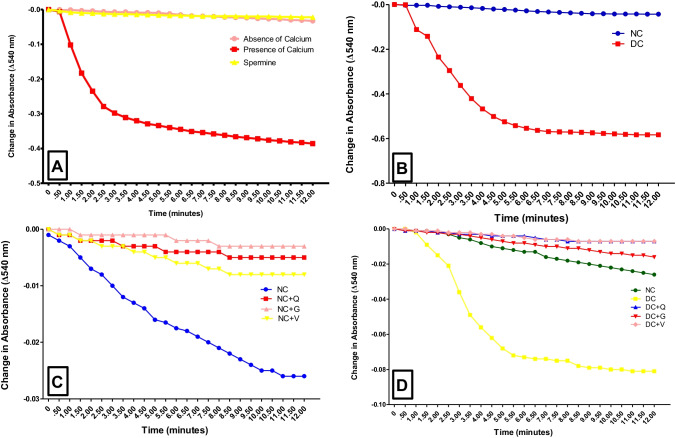

Treatment reverses mPT pore opening in STZ-induced diabetic rats

Figure 2a showed a typical mPT pore intactness in isolated rat liver mitochondria respiring on succinate and rotenone with inhibition by spermine. There was no significant change in absorbance readings at 30 seconds interval over 12 minutes, characterizing intact permeability transition pore. When the mitochondria of normal and diabetic rat were compared, there was a significant pore opening, sequel to diabetes condition ((Fig. 2b). Similarly, the mPT pore in isolated mitochondria from normal rat liver treated orally with quercetin, vitamin E or glibenclamide for 4 weeks showed no pore opening. This was evidenced by absence of observable decrease in the absorbance readings over a period of 12 minutes using mitochondria of similar protein concentrations ((Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Spectrophotometric measurement of liver mPT pore status in normal and diabetic rats. (a) Study of the mPT pore changes in absorbance of liver mitochondria respiring on succinate in the presence of rotenone with Ca2+ as triggering agent (presence of calcium) or without TA (absence of calcium) or Spermine (Inhibitor). (b) Assessment of the integrity of liver mPT pore in diabetic rat (c) Effects of treatment with quercetin and vitamin E on liver mPT pore of control rat. (d) Reversal of liver mPT pore opening in diabetic rats by vitamin E and quercetin treatment. NC = Normal control, DC = Diabetes control, NC + Q = Normal control that received quercetin, NC + G = Normal control that received glibenclamide, NC + V=Normal control that received vitamin E, DC + Q = Diabetic control that received quercetin, DC + G = Diabetic control that received glibenclamide, DC + V=Diabetic control that received vitamin E

Having substantiated that the treatment regimens were safe on the liver mitochondria, we measured the potency of same in reversing diabetes-induced mPT pore opening in rats. The result presented in Fig. 2d showed stimulation of mitochondrial pore opening in diabetic rat liver, evidenced by significant absorbance reading variations (P < 0.05). Treatment with quercetin, glibenclamide or vitamin E after induction of diabetes reversed the pore opening by 87, 70, 85% respectively (Fig. 2d). The result showed the impact of diabetes and treatment on the liver mPT pore.

Quercetin treatment reduced excessive cytochrome c release in STZ-induced diabetes

It has been shown that cytochrome c performs a critical function in apoptosis by initiating the rapid recruitment of Apaf-1 and apoptosome. This activates procaspase 9 and subsequently procaspase 3 resulting in cell death. Extent of cytochrome c release was determined in the stained liver sections of normal, diabetic and treated rats. The normal rat liver showed 42% difference in the level of Cytochrome c release relative to diabetic control (Fig. 3a and b). Following intervention by administration of quercetin and vitamin E in diabetic rats, a decrease of 23 and 48% of Cytochrome c release was observed in the liver (Fig. 3c and d). This result significantly differs from the findings in glibenclamide administration ((Fig. 3e). It was also observed that there was a statistical difference within the entire treatment regimens.

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical measurement of Cytochrome c release in the liver of normal and diabetic rats orally administered quercetin and vitamin E for 28 days. (a) NC (Normal control), (b) DC (Diabetic control), (c) DC + Q (Diabetic control that received 10 mg/kg quercetin), (d) DC + V (Diabetic control that received 10 mg/kg vitamin E), (e) DC + G (Diabetic control that received 6 mg/kg glibenclamide). Image J soft-ware was used to quantity the intensities of the stains. Scale bar = 5 μM. * = p < 0.05 compared to DC, + = Statistical difference between DC + Q10, DC + V and DC + G

Molecular docking

The interaction of amino acids of glibenclamide, quercetin and vitamin E with 4BEM and 1J3S were shown in Table 1. The results showed that glibenclamide had the highest binding energy of −9.4 Kcal/mol with F0F1 ATPase, while vitamin E was closely behind by −9 Kcal/mol (Table 1). The same trend of result was obtained when ligands were bound to Cytochrome C (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the binding affinity of glibenclamide, quercetin and vitamin E (α-Tocopherol) with 4BEM and 1J3S

| S/No | Compounds | 4BEM | Docking score (Kcal/mol) 1J3S |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Glibenclimide | −9.4 | −7.0 |

| 2 | Quercetin | −7.1 | −5.5 |

| 3 | Tocopherol | −9 | −6.4 |

Table 2 showed the amino acid interaction in the binding pocket of the ligands and the proteins. It was shown that while glibenclamide had 19 amino acids, quercetin had 15 and vitamin E had 19 respectively. Similarly, glibenclamide had 14 amino acids bonded in the pockets of Cytochrome C, while quercetin and vitamin E had 9 and 13 respectively.

Table 2.

Interaction of amino acids of glibenclimide, quercetin, vitamin E with F0F1 ATPase and Cytochrome C. F0F1 ATPase- 4BEM; Cytochrome C-1J3S

| S/No | Compound | Amino acids of interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4BEM | 1J3S | ||

| 1 | Glibenclimide | PHE31F, ILE27E, PHE31E, PHE31D, PHE31B, PHE31C, PHE48J, ILE44J, TYR131J, GLY45J, THR127J, GLY128J, PHE31A, ILE27B, GLY28A, ILE27A, ILE27C, ILE27D, ILE27F | CYS17A, MET80A, ILE81A, GLN16A,MET12A, ILE11A, SER15A, THR19A, LYS22A, LYS13A, CYS14A, HIS18A, PHE82A, GLU21A |

| 2 | Quercetin | PHE31E, ILE27E, GLY28E, GLY30F, ILE27F, PHE31F, GLY28F,ILE27G, PHE31H, GLY28G, GLY28H, PHE31I, ILE27H, ILE27I, PHE31G | GLN16A, PHE82A, ILE81A, MET80A, HIS18A, CYS14A, CYS17A, LYS13A, VAL83A |

| 3 | Tocopherol | PHE31G, PHE31F, ILE27I, PHE31I, PHE48J, THR127J,HIS18A, CYS14A, CYS17A, MET80A, PHE82A, LYS13A, ILE27J, PHE31A, GLY27A, PHE31B, ILE27B, THR131J, GLY45J, ILE44J, PHE31H, ILE27H,GLY28G, ILE27G, GLY28F | ARG91A, LYS87A, LYS86A, GLY84A, VAL83A, ILE85A, ILE81A |

Furthermore, the ligands interaction with proteins in Table 3 showed the hydrogen bond energy which defines the binding affinity to be highest in F0F1 ATPase for quercetin, relative to glibenclamide and vitamin E. However, this was the reverse in Cytochrome C (Table 3). Other bond types and distances which include unfavorable donor-donor, pi-pi T-shaped, alky, pi-alkyl, pi-sigma, van der Waals, pi-anion and carbon-hydrogen bonds were determined and the result shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Bond Type and Bond Distance between ligand molecules with target protein. 4BEM is F-type ATPase, 1J3S is Cytochrome C

| Protein | Compound (distance Å) | Hydrogen bonding | Unfavorable donor-donor | Pi-pi T-shaped | Alkyl | Pi-alkyl | Pi-sigma | Van der Waals | Pi-anion | Carbon Hydrogen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4BEM | Glibenclimide | – | – | PHE31B, PHE48J | ILE44J | PHE31E | – | PHE31F, ILE27E, PHE31D, PHE31C, TYR131J, THR127J, GLY128J, PHE31A, ILE27B, GLY28A, ILE27A, ILE27C, ILE27D, ILE27F | – | GLY45J |

| Quercetin |

ILE27F(2.316) ILE27G(2.371) |

– | PHE31G | – | – | – | PHE31E, ILE27E, GLY28E, GLY30F, PHE31F, PHE31H, GLY28G, GLY28H, PHE31I, ILE27H, ILE27I | – | GLY28F | |

| Tocopherol | ILE27G(2.362) | – | – | PHE48J, PH31A, THR131J | PH31I, PHE31B, ILE27B | – | PHE31G, PHE31F, ILE27I, THR127J, ILE27J, GLY27A, GLY45J, ILE44J, PHE31H, ILE27H, GLY28G, GLY28F | – | – | |

| 1J3S | Glibenclimide | GLN16A(2.026), SER15A(2.194), LYS13A(2.751) | – | – | MET80A | CYS17A, LYS22A | GLN16A (2.711) |

ILE81A, MET12A, ILE11A, THR19A, CYS14A, HIS18A, PHE82A |

GLU21A | – |

| Quercetin | GLN16A | GLN16A | PHE82A | – | CYS17A, | – |

ILE81A, MET80A, HIS18A, CYS14A, LYS13A, VAL83A |

– | – | |

| Tocopherol | – | – | – |

CYS14A, HIS18A, CYS17A |

MET80A, PHE82A, LYS13A, LYS86A, VAL83A |

– |

ARG91A, LYS87A, GLY84A, ILE85A, ILE81A |

– | – |

Ligand interaction with F-type ATPase

Illustration in Fig. 4 showed the 2D and 3D plot of the molecular interaction between glibenclamide, and the binding pockets of F0F1 ATPase. In the 2D plot (Fig. 4a), glibenclamide and F0F1 ATPase interacted with no hydrogen bond, however, van der Waals, carbon-hydrogen, Pi-Pi T-shaped, alkyl, pi-alky bonds were present. Figure 4b showed the 3D plot of interaction of glibenclamide at the binding site with F0F1 ATPase.

Fig. 4.

a) Predicted 2D binding interactions between glibenclamide and the active site of F-type ATPase. b) Predicted 3D binding pocket representation between glibenclamide and F-type ATPase

Results in Fig. 5a showed the 2D plot of quercetin and the hydrogen bond (green broken lines) interacting with F0F1 ATPase. The pi-pi T-shaped bond was also represented with pink broken lines. Figure 5b showed the 3D plot of quercetin interaction at the binding site of F0F1 ATPase.

Fig. 5.

a) Predicted 2D bonding mode of quercetin with the active site of F-type ATPase. b) 3D binding pocket representation between quercetin and F-type ATPase

Results in Fig. 6a showed the 2D binding interactions of vitamin E as with the residue of F-type ATPase. The hydrogen bond is represented by green broken lines and the pi-alkyl bond shown by purple broken line. The 3D plot (Fig. 6b) showed the interaction of vitamin E with F-type ATPase.

Fig. 6.

a) Predicted 2D bonding interactions between Vitamin E and F-type ATPase. b) 3D Binding pocket representation between Vitamin E and F-type ATPase

Ligand interaction with cytochrome C

Figure 7a showed that hydrogen bond interaction occurred between quercetin and Cytochrome C residue as represented by a green broken line. Similarly, pi-pi T-shaped bond was also evidenced by a purple broken line. The 3D plot in Fig. 7b also showed the interaction of the ligand and the binding site of Cytochrome C.

Fig. 7.

a) Predicted 2D binding interactions between quercetin and the active site of cytochrome C. b) Predicted 3D binding pocket representation between quercetin and cytochrome C

The 2D molecular interaction between vitamin E and the binding pocket of cytochrome C which include Van der waals, pi-alkyl and alky bonds (Fig. 8a). Figure 8b showed the 3D plot, displaying the conformation of the ligand at the binding site of cytochrome C.

Fig. 8.

a) Predicted 2D binding interactions between vitamin E and the active site of cytochrome C. b) Predicted 3D binding pocket representation between vitamin E and cytochrome C

Molecular interaction depicted by plot 2D in Fig. 9a showed that glibenclamide interacted with cytochrome C with hydrogen bond (green broken lines), pi-anion bond (orange), alkyl bond (pale purple). In the 3D plot (Fig. 9b), showing the position of ligand at the binding site of cytochrome C.

Fig. 9.

a) Predicted 2D binding interactions between glibenclamide and the active site of cytochrome C. b) Predicted 3D binding pocket representation between glibenclamide and cytochrome C

Discussion

Diabetes remains an important global health challenge as a result of the growing population. It has been predicted that the disease would affect almost 600 million people by 2035, majorly of those in the low and middle income areas [20]. Studies have shown that quercetin and vitamin E are cytoprotective in many disease conditions. They have been shown to diminish the classical features of DM and its associated complications, therefore could impart the search for antidiabetic drugs or adjuvants [21]. In the current investigation, an experimental and in silico studies of the use of quercetin and vitamin E were examined on F-type ATPase, as an antiapoptotic therapeutic strategy. It has been suggested by studies that a relationship exists between the mPT pore and the mATPase, and that it could be a requirement for the pore formation [6, 22]. The study aimed at discovering how the mATPase can be manipulated to treat certain pathologies where apoptosis is dysregulated [23]. Molecular docking studies showed that binding affinity of vitamin E to F-type ATPase was −9.0 kcal/mol. This compares well with the pose of glibenclamide (−9.4 kcal/mol), however, quercetin had an affinity of −7.1 kcal/mol. Although not much work has been done on the effect of glibenclamide on F-type mATPase, the present findings showed that the excessive enhancement of ATP hydrolysis noticed in diabetes was reversed by treatment with quercetin and vitamin E with vitamin E comparing more favorably with glibenclamide. Previous work has shown that these dietary molecules inhibited liver mPT pore opening, however, none has shown the versatility of the molecules in inhibiting F0F1 mATPase, a proposed constituent of the mPT pore [11, 24]. The F0F1 ATPase is expected to dissipate the generated electrochemical gradient in electron transport chain in a controlled manner; however, this reverses order in pathological conditions. Quercetin and vitamin E have been shown by docking studies to bind to this protein and stabilize it. This could impact the mPT pore shift observed in diabetes, since mitochondria show early pathological feature in the disease [25]. These observations would underscore the correlation of diabetes and the mitochondria. Our present study showed that the dietary molecules reversed the mPT pore opening in diabetic rat liver as well as glibenclamide. These results are consistent with past suggestions that the mPT pore opening potentiates uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation [6, 26].

Studies have shown that prolonged mPT pore opening due to various stress stimuli can activate the well conserved factors of intrinsic apoptosis, such as Cytochrome c, while quercetin and vitamin E have been shown to inhibit this in the heart [11, 27]. In the present study, the molecular docking studies of glibenclamide, quercetin and vitamin E were performed in the binding cavity of Cytochrome c. The results showed that all the ligands had favorable interaction with the protein. Vitamin E has the docking score of −6, 4 kcal/mol, which compared closely with glibenclamide (−7.4 kca/mol). The hydrogen bonding energy and other interactions of vitamin E was relatively similar to glibenclamide than quercetin. Despite current mPT pore concept evolution, elaborate evidences have shown that it’s uncoupling is accountable for Cytochrome c release. This strategically initiates cell demise via apoptosis [11, 28]. In the study, it was shown that diabetes-induced mPT pore opening and excessive mATPase activity influenced the release of apoptogenic Cytochrome c, a decisive point for caspase activation in intrinsic apoptosis. Furthermore, treatment with glibenclamide, quercetin and vitamin E decreased the extent of release with the best results from vitamin E administration. This coroborate the studies of Dhanya et al., (2021) on the antiapoptotic effect of quercetin in diabetes treatment [29].

Taken together, we have described the favorable interaction of quercetin and vitamin E with F-type mATPase and Cytochrome c. We have elucidated the close interaction of the ligands with the proteins as an essential feature of its non-activity mechanism. This unveiled that vitamin E has more privileged access to the binding cavity of the mATPase and Cytochrome c than quercetin, comparing well with the standard drug. While quercetin showed specific pi-pi interactions with the proteins, a critical fingerprint in molecular biology recognition, it was not as potent as vitamin E in the present study. These molecules may then be considered as potent adjuvants for diabetic treatment and drug like candidates.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the Director, Biomembrane and Biotechnology Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

Author contribution

Material preparation, investigation, resources, funding, data collection [Oluwatoyin Ojo, Ogunleke Titlayo]; Computational Studies [Joshua Ajeoge]; Analysis, writing, editing [Oluwatoyin Ojo]; Conceptualization, supervision, project administration [Olufunso Olorunsogo].

Data availability

The dataset generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed using experimental animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the procedures of the University of Ibadan Ethics Committee, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sarker U, Oba S, Daramy MA . Nutrients, minerals, antioxidant pigments and phytochemicals, and antioxidant capacity of the leaves of stem amaranth. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Zhang YJ, Gan RY, Li S, Zhou Y, Li AN, Xu DP, & Li HB. Antioxidant phytochemicals for the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2015;20(12):21138–21156. 10.3390/molecules201219753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Pisoschi AM, Pop A, Iordache F, Stanca L, Predoi G, & Serban AI. Oxidative stress mitigation by antioxidants-an overview on their chemistry and influences on health status. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;209:112891. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Salehi B, Machin L, Monzote L, Sharifi-Rad J, Ezzat SM, Salem MA, ... & Cho WC. Therapeutic potential of quercetin: new insights and perspectives for human health. Acs Omega. 2020;5(20):11849-11872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams JM, Adam D, Agostinis P, ... & Turk B. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2018. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2018:25(3);486-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Bonora M, Wieckowski MR, Chinopoulos C, Kepp O, Galluzzi L, Pinton P. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: central implication of ATP synthase in mitochondrial permeability transition. Oncogene. 2014;1-12. 10.1038/onc.2014-96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Najafi M, Farajnia S, Mohammadi M. Badalzedeh R, Ahmadi AN, Baradaran B, Amani M. Inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore restores the cardioprotection by postconditioning in diabetic hearts. J Diab Metab Disorders. 2014;13:106. 10.1186/s40200-014-0106-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Goldenberg RM, Gilbert JD, Hramiak IM, Woo VC, Zinman B . Sodium-glucose co-transporter inhibitors, their role in type 1 diabetes treatment and a risk mitigation strategy for preventing diabetic ketoacidosis: the STOP DKA protocol. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(10):2192-2202. 10.1111/dom.13811. Epub 2019 Jun 30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ekins S, Mestres J, & Testa B. In silico pharmacology for drug discovery: methods for virtual ligand screening and profiling. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152(1):9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Punithavathi VR, Stanely Mainzen Prince P . Protective effects of combination of quercetin and α-tocopherol on mitochondrial dysfunction and myocardial infarct size in isoproterenol-treated myocardial infarcted rats: biochemical, transmission electron microscopic, and macroscopic enzyme mapping evidences. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2010;24:303–312, 2010. 10.1002/jbt.20339. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Ojo OO, Obaidu IM, Obigade OC, Olorunsogo OO. Quercetin and vitamin E ameliorate cardio-apoptotic risks in diabetic rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2022;477(3):793-803. Doi: 10.1007/s11010-021-04332-w. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Saravanan G, Leelavinothan P. Effect of Syzygium Cumini bark on blood glucose, plasma, insulin and C-peptide in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Intl J Endocrinol Metab. 2005;4(2):96-105.

- 13.Johnson D and Lardy H. Isolation of liver or kidney mitochondria. Methods Enzymol. 1967;10:94-96.

- 14.Lardy HA and Wellman H. The catalytic effect of 2, 4-dinitrophenol on adenosinetriphosphate hydrolysis by cell particles and soluble enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1953;201(1): 357-370. [PubMed]

- 15.Olorunsogo O, Bababunmi E, Bassir O. Uncoupling effects of N-phosphonomethylglycine on rat liver mitochondria. Biochem Pharmacol. 1979;27: 925-927. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Bassir O. Improving the level of nutrition. West African J Biol Appl Chem. 1963;7: 32-40.

- 17.Lapidus RG and Sokolove PM. Inhibition by spermine of the inner membrane permeability transition of isolated rat heart mitochondria. FEBS letters. 1992;313.3: 314-318. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL and Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193.1: 265-275. [PubMed]

- 19.Qazi S, Das S, Khuntia BK, Sharma V, Sharma S, Sharma G, Raza K. In silico molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation analysis of phytochemicals from Indian foods as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp and 3CLpro. Natural Products Communication. 2021.

- 20.Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2014;103.2: 137-149. 10.1177/2F1934578X211031707. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Gomes AC, Bueno AA, de Souza RG, Mota JF. Gut microbiota, probiotics and diabetes. Nutr J. 2014;2014 Jun 17;13:60. 10.1186/1475-2891-13-60. PMID: 24939063; PMCID: PMC4078018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Alvian KN, Beutner G, Lazrove E, Sacchetti S, Park HA, Licznerski P, Li H, Nabili P, Hockensmith K, Graham M et al. An uncoupling channel within the c-subunit ring of the F1F0-ATP synthase is the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014. 111:10580-10585 [PubMed:24979777]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Bonora M, Pinton P. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and cancer: molecular mechanisms involved in cell death. Front Oncol. 2014;4(3):302. 10.3389/fonc.2014.00302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Daniel OO, Adeoye AO, Ojowu J, Olorunsogo OO. Inhibition of liver mitochondrial membrane permeability transition pore opening by quercetin and vitamin E in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. 2018;BBRC 504: 460-469. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Alston CL, Rocha MC, Lax NZ, Turnbull DM, & Taylor RW. The genetics and pathology of mitochondrial disease. J Pathol. 2017;241(2):236–250. 10.1002/path.4809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Bernardi P, Di Lisa F. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: molecular nature and role as a target in cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;78:100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Hüttemann M, Lee I, Perkins GA, Britton SL, Koch LG & Malek MH. (−)-Epicatechin is associated with increased angiogenic and mitochondrial signalling in the hindlimb of rats selectively bred for innate low running capacity. Clin Sci. 2013;124(11):663-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Wu J, Ye J, Kong W, Zhang S, & Zheng Y. Programmed cell death pathways in hearing loss: a review of apoptosis, autophagy and programmed necrosis. Cell Prolif. 2020;53(11):e12915. 10.1111/cpr.12915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Dhanya R. Quercetin for managing type 2 diabetes and its complications, an insight into multitarget therapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;146:112560. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.