Abstract

Objective

The aim of this review is to speculate the pre-clinical and clinical evidences indicating the association between butyrate-synthesizing firmicutes and development and progression of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methodology

Literature was searched using ‘Google Scholar’ and ‘PubMed’ to find out most relevant articles for the scope of this review. Information was also gathered from authentic sources such as the World Health Organisation and the International Diabetes Federation.

Results

Evidences suggest that an abnormal perturbation in the gut microbiome characterized by subsided levels of butyrate-producing bacteria may gradually result in the progression of type-2 diabetes; however, the explicit mechanisms underlying and implicating the role of specific butyrate-producing microbes remain unclear.

Conclusions

This review explicitly summarizes the role of butyrate-synthesizing firmicutes known to be reduced in the subjects with type-2 diabetes mellitus in host metabolic health and contemplates the putative and reported mechanisms underlying its implication in the pathophysiology of type-2 diabetes mellitus.

Keywords: Butyrate, Butyric acid, Diabetes, Gut, Microbiota, Microflora, Firmicutes

Introduction

Type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic metabolic non-communicable disease (NCD) caused by impaired insulin secretion and/or action [1, 2]. For many decades, T2DM was considered a disease of minor significance to global health, but now, its ever-increasing prevalence has seriously affected and concerned human health [3]. According to the WHO global report, the number of T2DM cases is estimated to have an alarming rise from 415 million in 2015 to 642 million by 2040 [4]. Based on the International Diabetes Federation survey in 2015, one in eleven adults has diabetes, one in two adults with diabetes is undiagnosed, one in 7 births is affected by gestational diabetes, and 12% of global health expenditure is spent on diabetes [5].

The gut microbiome is a collective term used to represent the microbial community inhabiting the gut [6]. The five bacterial phyla dominating the human gut microbiome are Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia, followed by Archaea and Euryarchaeota [6]. The maintenance of host health is significantly associated with the relative ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes [7]. The majority of butyrate-producing bacteria belong to phylum Firmicutes. Potential butyrate producers were also identified from other phyla, especially Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Thermotogae, Spirochaetes, Bacteroidetes, and Fusobacteria [8]. Among the phylum Firmicutes, the genera Eubacterium, Clostridium, Coprococcus, Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, and Ruminococcus are the significant members [9]. The altered composition of gut microbiota, especially the distorted Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio, has been linked with several disorders, including T2DM, inflammatory bowel disease, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and many more [10]. The reduced synthesis of beneficial short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) is one of the significant reasons speculated to be underlying this association [11, 12].

This review focuses specifically on Firmicutes, the major butyrate-producing group among the gut microbiome. Instead of a monophyletic group, a functional cohort is established in the gut by the butyrate producers [8]. Among the phylum Firmicutes, Clostridium leptum and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii of the family Ruminococcaceae, and Roseburia spp. and Eubacterium rectale of the family Lachnospiraceae [13, 14] and Eubacterium hallii and Anaerostipes spp. [13] are the significant butyrate-synthesizing species. A much longer list of butyrate-producing bacteria is present as few members belonging to the phyla of Thermotogae, Actinobacteria, Spirochaetes, Fusobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes, have genes encoding enzymes such as butyryl-CoA transferase, butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase, and/or butyrate kinase that synthesize butyrate [8]. Butyrate, an essential and beneficial SCFA in the human gut, plays a vital role in maintaining colonic homeostasis [15]. Reduced levels of butyrate have been found to be linked with an increased risk of T2DM [11]. Hence, it is speculated that an abnormal alteration in the abundance of Firmicutes in the gut may affect various metabolic pathways, leading to the development of various syndromes including T2DM [16] and, thus, butyrate-synthesizing Firmicutes may serve as a prognostic biomarker as well as a therapeutic target in the management and amelioration of these conditions.

Butyrogenic firmicutes

The human gut encompasses a very dense community of metabolically active microbiota. However, only a limited number of gut bacteria are documented as butyrate producers. Most of the butyrate-synthesizing bacteria in the human gut are distributed in the phylum Firmicutes [17]. Among Firmicutes, Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Eubacteriaceae, and Clostridiaceae are the four prominent families encompassing the significant butyrate-synthesizers [8, 18, 19]. Clusters IV, XIVa, XVI, and I of the order Clostridiales comprises most of the species that are butyrate producers. Two important species among them, Eubacterium rectale and F. prausnitzii belonging to clostridial cluster XIVa and clostridial cluster IV, respectively, constitute 12-14% of the total intestinal microbiota in fecal samples of healthy adults [20]. Furthermore, Roseburia spp., Coprococcus spp., Ruminococcus spp., Anaerostipes spp., Butyrivibrio spp., and Clostridium spp., distributed across cluster XIVa and Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum, Subdoligranulu variabile, Anaerotruncus colihominis, and Papillibacter cinnamivorans distributed across cluster IV, are the other butyrogenic species [8, 19, 21].

Megasphaera elsdenii and Caldocellum saccharolyticum belonging to the family Veillonellaceae, Thermoanaerobacterales Family III have also been reported to be synthesizing butyrate [19, 22]. Recently, high throughput metagenomic sequencing of the human samples has revealed that Lawsonibactera saccharolyticus, a novel species in the family Ruminococcaceae [23] and IntestinimonasbutyriciproducensAF211 encodes butyryl-CoA: acetyl-CoA transferases for the synthesis of butyrate [24].

Intestinal short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) synthesis

Carbohydrates are the primary and vital energy sources for human and commensal microbial cells. There are numerous complex carbohydrates and plant polysaccharides that cannot be degraded by human enzymes [6]. These non-digestible carbohydrates (NDCs), including cellulose, xylans, resistant starch, inulin, etc., that gets escaped from digestion and intestinal absorption, undergo saccharolytic microbial fermentation in the large intestine by the gut microbiota, resulting in the production of organic fatty acids with 1 to 6 carbons viz., SCFAs [25]. Acetate, Butyrate, Propionate, and Formate are the major SCFAs products [25], of which acetate, propionate, and butyrate are present in the ratio of 60%, 25%, and 15%, respectively, in the colonic lumen [26]. The flow of carbon from the diet through microbiota to the human host is represented by the production of SFCAs [25].

For most gut anaerobes, acetate is a net fermentation product, and it has the highest concentrations in SCFA in the gut lumen. Butyrate and propionate are solely produced by a distinct cohort of gut bacteria [14]. The majority of butyrate-producing species belongs to the two predominant families, Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae, along with Erysipelotrichaceae and Clostridiaceae of the phylum Firmicutes [19, 27]. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, one of the most abundant species in the Ruminococcaceae family, produces butyrate through butyryl-CoA: acetate CoA-transferase with net consumption of acetate [18]. Similarly, Eubacterium rectale/Roseburia spp., belonging to the Lachnospiraceae family, also utilizes the butyryl-CoA: acetate CoA-transferase pathway in butyrate production. Roseburia spp. uses butyryl-CoA as the main enzyme in butyrate synthesis [14]. CoA-transferase gene in Roseburia spp. A2-183 is responsible for butyrate synthesis in the host colon [28, 29]. Anaerostipes hadrus, Coprococcus catus, and Eubacterium hallii are other Lachnospiraceae species with the butyryl-CoA: acetate CoA-transferase gene [14].

Butyrate synthesis pathways

Only a few glycosidic linkages present in carbohydrates can be degraded by human enzymes. The gut microbiome has a wide range of enzymes, including glycosyltransferases, polysaccharide lyases, glycoside hydrolases, and carbohydrate esterase, all of which are essential for the degradation of carbohydrates. Only a few butyrate-synthesizing species can degrade NDCs [17]. The four major butyrate synthesis pathways are the acetyl-CoA,4-aminobutyrate, lysine, and glutarate pathways [8]. Acetyl-CoA pathway, using carbohydrate as the primary substrate, is the major butyrate synthesis pathway used particularly by the members of the phylum Firmicutes [13]. Other pathways, such as the lysine, succinate, and glutarate pathways, using amino acids as major substrates, have been reported in the phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Fusobacteria [8, 24].

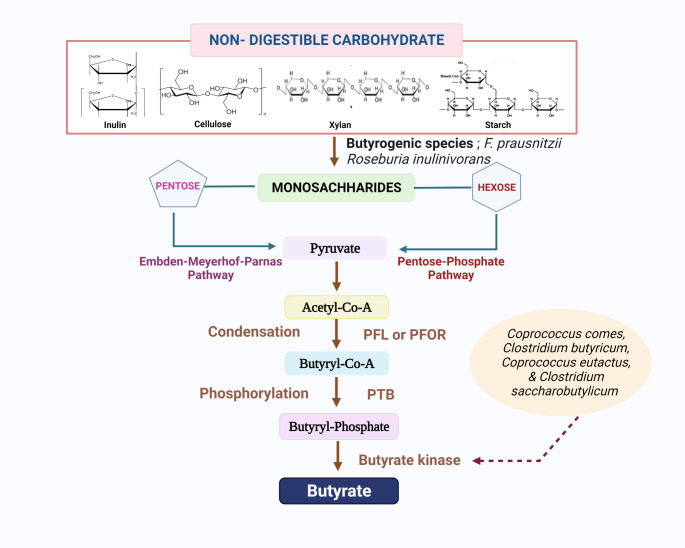

The direct degradation of NDCs is restricted only to a few butyrogenic species [17]. F. prausnitzii have been reported to degrade inulin and pectin [30], and Roseburia inulinivorans encode b-fructo-furanosidase, for degrading both inulin and fructo-oligosaccharide (FOS) [31]. After the oligosaccharides get degraded into monosaccharides, the pentoses get converted to pyruvate through the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway, and hexoses get converted into pyruvate through the pentose phosphate pathway. The pyruvate thus formed gets converted into acetyl-CoA by the enzyme pyruvate-formate lyase (PFL) or by pyruvate: ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR) enzyme. Through condensation reaction, two molecules of acetyl-CoA get converted into butyryl-CoA. Later, Butyryl-CoA undergoes phosphorylation to form butyryl-phosphate by phosphor-trans-butyrylase (PTB) enzyme. Subsequently, butyryl-phosphate gets converted into butyrate by butyrate kinase [14]. The use of butyrate kinase enzyme in the synthesis of butyrate has been observed in Coprococcus comes, Clostridium butyricum, Coprococcus eutactus, and Clostridium saccharobutylicum [8, 13, 32] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Acetyl-CoA pathway in the synthesis of butyrate by the butyrogenic firmicutes is displayed. PFL-Pyruvate-formate lyase; PFOR- pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase; PTB- Phosphor-trans-butyrylase

An alternative pathway in butyrate production has been reported in Megasphaera elsdenii, E. hallii, Anaerostipes caccae, Anaerostipes rhamnosivorans, Anaerostipes butyraticus, and Anaerostipes hadrus where, instead of carbohydrates, lactate is converted into pyruvate and subsequently gets converted into butyrate, either by butyryl-CoA: acetyl-CoA transferase or by butyrate kinase [13, 19, 33–35]. Conversion of succinate to crotonyl-CoA, a butyrate precursor, which then gets transformed into butyrate, is another common butyrate synthesis pathway [36].

Since the gut microbiota works as a community, cross-feeding between intermediary metabolites (acetate and lactate) among different species has a critical role in butyrate production. Several Firmicutes have been documented to possess the ability of acetate utilization in the synthesis of butyrate [37, 38]. Butyryl-CoA: acetyl-CoA transferase pathways in butyrate synthesis require acetate through cross-feeding with various species. In this pathway, the CoA moiety of butyryl-CoA gets converted into acetate leading to the formation of butyrate and acetyl-CoA [39, 40]. Thus, the fermentation of NDCs in the human intestine varies within families, species, and even in strains.

Protective role of butyrate in T2DM

Butyrate plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of T2DM. It is the primary source of energy for the gut epithelial cells. The homeostatic/ balanced levels of butyrate reduce liver glucose production by inducing gluconeogenesis in the gut [12]. Butyrate also decreases inflammation and endotoxemia and increases insulin sensitivity, the absence of which can induce the development of T2DM [6].

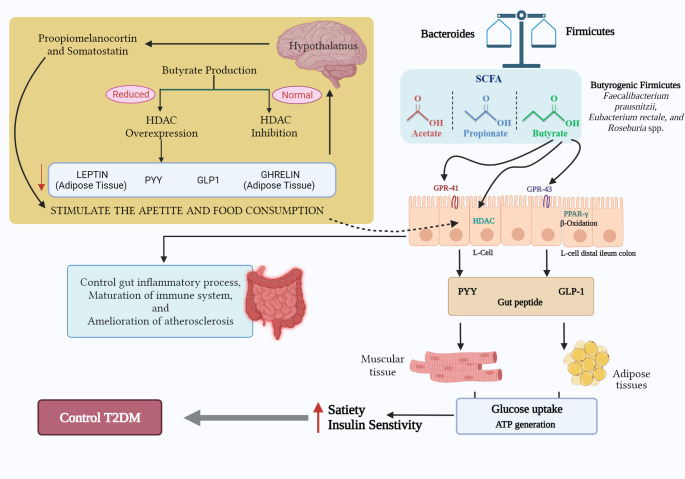

Animal model experiments reveal that butyrate acts as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor [41]. HDAC inhibitors have a significant role in β-cell differentiation and proliferation and improving insulin sensitivity [42]. HDAC controls the expression of glucose-6-phosphate and the resulting gluconeogenesis, thereby alleviating hyperglycemia [43]. Butyrate can regulate gene expression by binding GPCRs (G-Protein-Coupled receptors) GPR41 and GPR43 [6]. Butyrate also has a role in suppressing inflammation through GPR43 signalling in neutrophils [44]. Another vital role of butyrate in glucogenesis is stimulating the release of glucagon-like proteins (GLP-1 and GLP-2) from L-cells of the distal ileum and colon [45]. GLP-1 induces neogenesis and regeneration of pancreatic β-cells and activates GPCRs in β-cells, whereas GLP-2 inhibits endotoxemia and inflammation [12] (Fig. 2). GPCR activation results in the production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), resulting in increased secretion of glucose-stimulated insulin [45].

Fig. 2.

Protective role of butyrate in type-2 diabetes. The ameliorative role of butyrogenic firmicutes in type-2 diabetes via maintaining and promoting gut health primarily through the production of short-chain fatty acid butyrate

Any alteration in the level of butyrate production can affect glucose metabolism resulting in a gradual deterioration in insulin sensitivity, i.e., insulin resistance. This leads to islet failure, wherein pancreatic islets β cells fail to maintain the required insulin output [46]. The dysbiosis of gut microbiota leads to alteration in the abundance of beneficial microbial phyla, especially butyrate-synthesizing Firmicutes [6]. One of the significant consequences of gut dysbiosis is the diminished levels of SCFAs synthesis [45]. Since butyrate acts as an HDAC inhibitor, the reduced levels of butyrate gradually lead to the over-expression of HDAC, causing decreased levels of anorexic hormones such as Leptin, GLP-1, Peptide YY, Ghrelin associated with the appetite and energy intake [6]. Ghrelin and Leptin are the key hunger hormones, the decreased levels of which increase the appetite and food consumption by stimulating hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin and somatostatin neurons, respectively [47](Fig. 1). The reduced secretion of Peptide YY hinders the proper maintenance of peristaltic movement and the functions of pancreatic cells [48]. Another serious concern associated with the over-expression of HDACs is the decreased induction of intestinal gluconeogenesis, resulting in increased hepatic glucose production, slower metabolism, and delayed-phase insulin secretion. Over-expression of HDACs also results in the disruption of β-cells development and insulin signalling [6]. Thus, the depletion in butyrate synthesis plays a vital role in the increased risk for T2DM.

Butyrate also has a significant role in maintaining intestinal and extra-intestinal health. Butyrate has a role in preserving the colonic homeostasis as it is the primary energy source for the intestinal epithelial cells [15]. The multiple effects of butyrate at the homeostatic intestinal level are inflammatory and oxidative stress status, cell growth and differentiation, intestinal motility and visceral perception, immune regulation, ion absorption, and intestinal barrier function. Butyrate also has a role in insulin sensitivity, cholesterol synthesis, energy expenditure, and stimulation of β-oxidation of very long-chain fatty acids at the extra-intestinal level. Neurogenesis, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein function, fatty acids, peroxisome proliferation, and fetal hemoglobin (HbF) production are some of the other extra-intestinal functions of butyrate [26]. This wide range of essential features explains the role butyrate plays in the interactions between key Firmicute species and the host.

Clinical evidence of the reduced abundance of butyrogenic Firmicutes in T2DM patients

The major butyrate-synthesizing phylum, Firmicutes, has a notable reduction in T2DM patients[49]. Several human studies support the fact that the abundance of butyrate-synthesizing Firmicutes is significantly reduced in T2DM subjects compared to healthy counterparts (Table 1). Fecal microbiota analysis in these patients revealed a declined abundance of families like Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae in subjects with newly diagnosed or long-standing diabetes compared to normal glucose tolerant subjects [50]. Ejtahed et al. (2020), using the qPCR-based microbiota analysis, also reported a higher abundance of Roseburia and Faecalibacterium in healthy subjects compared to individuals with type-2 or type-1 diabetes [51]. A combination of in-depth metagenomics and metaproteomics analysis of fecal samples confirmed that the butyrate-producing Roseburia hominis was significantly lower in both individuals with pre-diabetes (Pre-DM) or treatment-naïve type-2 diabetes (TN-T2D) when compared with normal glucose-tolerant (NGT) and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was lower in Pre-DM compared to both NGT and TN-T2D individuals [52].

Table 1.

Overview of studies depicting the decreased abundance of butyrate-producing Firmicutes in cases of T2DM

| Reference | Participants’ specification | Mean age of participants | Method used | The abundance of butyrate-producing Firmicutes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [54] |

• Healthy Controls (HC, n = 30) • Type 2 Diabetic (T2DM, n = 25) • Diabetic retinopathy (DR, n = 28) |

• HC:52.2 years • T2DM:57.3 years • DR:55.07 years |

Sequencing of 16 S rRNA Gene Amplicons | Roseburia and Lachnospira were significantly reduced in abundance in T2DM and DR patients. |

| [51] |

• Type 1 Diabetic (T1D, n = 21) • Type 2 Diabetic (T2D, n = 49) • Healthy Controls (HC, n = 40) |

• T1D:35.4 ± 12.4 years • T2D:57.2 ± 9.9 years • HC:38.0 ± 9.8 years |

qPCR method targeting bacterial 16 S rRNA gene | Roseburia and Faecalibacterium significantly reduced among DM patients. |

| [52] |

• Treatment-Naïve Type 2 Diabetic (TN-T2D, n = 77) • Pre-Diabetic (Pre-DM, n = 80) • Normal Glucose Tolerant (NGT, n = 97) |

• 66 ± 8 years | Metagenomic and Metaproteomic analysis |

Significantly lower abundance of Roseburia hominis in individuals with Pre-DM and T2D. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii significantly reduced among Pre-DM. |

| [50] |

• Healthy controls (NGT, n = 19) • New-DM(n = 14) • Known-DM(n = 16) |

• NGT: 48.85 ± 5.4 years • New-DM: 48.64 ± 5.68 years • Known-DM: 50.62 ± 3.49 years |

Sequencing of 16 S rRNA Gene Amplicons | Decreased abundance of families like Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae |

| [56] |

• Normal Glucose Tolerant (NGT, n = 44) • Impaired Glucose Tolerant (Pre-DM, n = 64) • Newly diagnosed (T2DM, n = 13) |

• NGT: 55 ± 69 years • Pre-DM: 54 ± 67 years • T2DM: 52 ± 69 years |

qPCR and metagenomic shotgun sequencing of 16 S rDNA gene V3–V5 amplicons. | Akkermansia muciniphila ATCCBAA-835 and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii are more abundant in the NGT group. |

| [57] |

• Type 2 Diabetic (T2D, n = 53) • Impaired Glucose Tolerant (IGT, n = 49) • Normal Glucose Tolerant (NGT, n = 43) |

• T2D: 70.5 ± 0.1 years • IGT:70.5 ± 0.1 years • NGT:70.3 ± 0.1years |

Metagenomic shotgun Sequencing | Decreased abundance of Roseburia, Clostridiales, Eubacterium eligens, Coriobacteriaceae and Bacteroides intestinalis in T2D subjects. |

| [55] |

• Type 2 Diabetic (T2D, n = 18) • Non-Diabetic Controls(n = 18) |

• 56 ± 13 years | Pyrosequencing the 16s rRNA. | Lachnospiraceae and Roseburia less abundant in T2DM |

| [81] |

• Type 2 Diabetic (T2D, n = 23) • Type 1 Diabetic (T1D, n = 22) • Healthy controls (HC, n = 23) |

• T2D: 60 years • T1D: 36 years • HC: 37 years |

Metagenomic sequencing of 16 S rRNA gene | Lower relative abundance of Roseburia and Faecalibacterium in T2DM than in controls. |

| [53] |

• Type 2 Diabetic (T2D, n = 71) • Healthy Controls (HC, n = 74) |

• T2DM: 42.3 ± 10.6 • HC: 53.6 ± 10.9 |

Whole Genome and metagenomic Sequencing | Clostridiales sp. SS3/4, Eubacterium rectale, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia intestinalis and Roseburia inulinivorans enriched in the control samples. |

Similar results were observed by Qin et al. (2012), where butyrate-producing Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Clostridiales sp. SS3/4, Roseburia intestinalis, Roseburia inulinivorans, and Eubacterium rectale were enriched in the control samples compared to T2DM patients [53]. A cross-sectional study on patients with T2DM and diabetic retinopathy revealed a significant decrease of Roseburia and Lachnospira in addition to several other gut microbial genera in patients with T2DM [54]. Several other studies on patients with T2DM, impaired glucose tolerance, or newly-diagnosed diabetes also exhibited a lower abundance of several butyrate-synthesizing Firmicutes in these patients compared to normal control subjects [55–57]. Other parallel studies have also reported a similarly reduced abundance in patients with T2DM [58, 59]. Together, these studies implicate the association of butyrate-synthesizing Firmicutes in the pathophysiology of T2DM-related glucose intolerance and/or insulin resistance.

Influence of diet on the butyrogenic gut bacteria

Dietary habit is a significant environmental factor in shaping the gut microbiota. Variations in long-term dietary patterns, especially following vegetarian, vegan, or omnivorous diets, significantly impacts the composition of butyrate-synthesizing gut microbes, especially firmicutes [60, 61].

Studies have reported that the plant-based diet has a significant role in maintaining the abundance of butyrate-producing bacterial genera, especially Roseburia. Dietary fibers, especially the NDCs from plant products, increase the abundance of lactic acid bacteria such as Roseburia, resulting in the fermentation of carbohydrates into SCFAs, including butyrate, fermented primarily by Roseburia spp.[60]. A dietary intervention study conducted by David et al. (2014) suggested that the plant-based diet is essential for increasing the levels of fiber-fermenting firmicutes. The dietary intervention provided an animal-based diet including meat, eggs, and cheese to one group of subjects and a plant-based diet rich in grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables to the other group. It was observed that levels of dietary plant polysaccharides metabolizing Firmicutes like Roseburia, Eubacterium rectale, and Ruminococcus bromii were decreased in the animal-based diet group compared to the other group [62]. Ruengsomwong et al. (2014) classified vegetarians further into ovo-lacto vegetarians and lacto-vegetarians and observed that several butyrate-synthesizing bacterial genera were enriched in ovo-lacto vegetarians [63]. A similar study on the vegan and omnivorous group identified that the percentage of butyrate producing bacterial genera, including Bifidobacterium, Roseburia, and Subdoligranulum, was significantly higher in the vegan population [61].

Adherence to a nutritionally balanced Mediterranean diet (MD), which includes increased quantity and frequency of fruits, vegetables, cereals, nuts, and legumes, characterized by essential vitamins, minerals, phenols, terpenes, and flavonoids, has been observed to restore the structure of the gut microbiome and increase the abundance of beneficial Firmicutes in subjects with obesity [49, 64]. Our recent studies on non-human primates maintained on a MD, or a Western diet also demonstrated similar results wherein the intestinal population of butyrate-producing bacteria was significantly increased in subjects consuming the Mediterranean diet [65]. These studies support the importance of including vegetarian foods in the diet, which are essential in maintaining efficient metabolism and a healthy gut environment.

Also, numerous researches have identified the beneficial effect of probiotics in ameliorating diabetes. Among these several butyrogenic firmicutes like Bifidobacterium [66–68], Lactobacillus [66–68], Clostridium [69, 70] etc., are a few among the well-studied genera, as probiotics. Therefore, including these probiotics in diet can augment the butyrate synthesis, which in turn helps in regulating blood glucose level and metabolic health.

Future prospects

The potential benefits of probiotics, including the anti-diabetic property, lowering serum cholesterol concentrations, and enhancing immune responses, are well documented [71, 72]. Several randomized control trials have identified various strains which are effective in maintaining HbA1c levels [66], fasting blood glucose [73], and insulin sensitivity [72]. Animal studies on older obese mice have shown that probiotic therapy may constructively modify the gut microbiota, which subsequently improves the metabolic health of the obese mice [74]. To target microbial dysbiosis and restore gut homeostasis, supplementing butyrate-synthesizing bacteria could be a promising probiotic approach. The few among such probiotic candidates are F. prausnitzii, Roseburia spp. or Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum [75].

According to WHO, the first criterion to be considered a probiotic strain is that the strain should be identified by phenotypic and genotypic methods [76]. Human and animal studies on fecal microbiota transfer (FMT), including butyrate-synthesizing Firmicutes, suggest that it is safe for the intended use [77, 78]. Vrieze et al. (2012) observed that the transfer of fecal microbiota containing 16 bacterial groups, including the Roseburia intestinalis and Eubacterium hallii, from lean donors improved the insulin sensitivity in the obese recipients with metabolic syndrome. The primary observation was that the number of butyrate-synthesizing Roseburia intestinalis had a 2.5-fold increase, attributing the improved insulin sensitivity to increased microbial metabolism and consequent increase in the production of butyrate [77]. The susceptibility to T2DM significantly decreased after the fecal microbiota transfer from healthy to obese rats [78]. Although FMT is considered a promising application for restoring the gut microbiome, several controversies exist regarding the risk-benefit ratio and potential adverse effects [79]. Therefore, defining an ideal protocol for donor screening and infusing donor feces in patients with metabolic disorders can be a promising approach towards improving metabolic health.

Due to the inadequacy of preclinical and clinical studies explicitly conducted with the butyrate-producing Firmicutes alone, these strains’ dose, shelf-life, and probiotic potential remain undefined and await further mechanistic and comprehensive studies [76, 80]. Although several studies have shown a reduced abundance of butyrate-synthesizing Firmicutes in patients with T2DM, further mechanistic and comprehensive clinical studies involving large numbers of T2DM patients are needed to attain and validate specific evidence of the speculated preventive and therapeutic role of butyrate-producing Firmicutes in clinical practice.

Funding

This study was supported/ funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research (DHR-ICMR/GIA/05/18/2020 and ICMR No.5/4/5–12/Diab/21-NCD-III).

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kerner W, Definition, Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus. 2014;384–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Unnikrishnan R, Anjana RM, Mohan V. Diabetes mellitus and its complications in India. Nat Publ Gr. Nature Publishing Group; 2016;12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Zimmet P, Alberti KGMM, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001;414:782–7. doi: 10.1038/414782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Global Report on Diabetes. Glob Rep DIABETES. 2016;978:6–86. [Google Scholar]

- 5.IDF. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 7th Ed. 2015.

- 6.Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. 2012;489:1–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Zhang H. Microbiota associated with type 2 diabetes and its related complications. Food Sci Hum Wellness. Beijing Academy of Food Sciences.; 2013;2:167–72. Available from: 10.1016/j.fshw.2013.09.002.

- 8.Vital M, Howe AC, Tiedje JM. Revealing the bacterial butyrate synthesis pathways by analyzing (meta)genomic data. MBio. 2014;5:1–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00889-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagpal R, Kumar M, Yadav AK, Hemalatha R, Yadav H, Marotta F, et al. Gut microbiota in health and disease: an overview focused on metabolic inflammation. Benef Microbes. 2016;7:181–94. doi: 10.3920/bm2015.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar M, Nagpal R, Hemalatha R, Yadav H, Marotta F. Probiotics and Prebiotics for Promoting Health: Through Gut Microbiota. Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics. Elsevier Inc.; 2016. Available from: 10.1016/B978-0-12-802189-7.00006-X.

- 11.Duggal N, Kapoor S. Role of Gut Microbiota in Pathogenesis and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Eurasian J Med Oncol. 2021;5:103–10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanase DM, Gosav EM, Neculae E, Costea CF, Ciocoiu M, Hurjui LL, et al. Role of Gut Microbiota on Onset and Progression of. Nutrients. 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Louis P, Flint HJ. Diversity, metabolism and microbial ecology of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;294:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louis P, Flint HJ. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ Microbiol. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017;19:29–41. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1462-2920.13589. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hamer HM, Jonkers D, Venema K, Vanhoutvin S, Troost FJ, Brummer R. Review article: the role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:104–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamanai-shacoori Z, Smida I, Bousarghin L, Loreal O, Meuric V, Fong SB, et al. Roseburia spp.: a marker of health ? Future Microbiol. 2017;12:157–70. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2016-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu X, Liu Z, Zhu C, Mou H, Kong Q. Nondigestible carbohydrates, butyrate, and butyrate-producing bacteria. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. Taylor & Francis; 2019;59:S130–52. Available from: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1542587. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Duncan SH, Hold GL, Harmsen HJM, Stewart CS, Flint HJ. Growth requirements and fermentation products of Fusobacterium prausnitzii, and a proposal to reclassify it as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii gen. nov., comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. Microbiology Society; 2002;52:2141–6. Available from: https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/ijsem/10.1099/00207713-52-6-2141. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Louis P, Duncan SH, McCrae SI, Millar J, Jackson MS, Flint HJ. Restricted distribution of the butyrate kinase pathway among butyrate-producing bacteria from the human colon. J Bacteriol. J Bacteriol; 2004;186:2099–106. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15028695/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Walker AW, Duncan SH, Louis P, Flint HJ. Phylogeny, culturing, and metagenomics of the human gut microbiota. Trends Microbiol. Trends Microbiol; 2014;22:267–74. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24698744/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Van Den Abbeele P, Belzer C, Goossens M, Kleerebezem M, De Vos WM, Thas O, et al. Butyrate-producing Clostridium cluster XIVa species specifically colonize mucins in an in vitro gut model. ISME J 2013 75. Nature Publishing Group; 2012;7:949–61. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/ismej2012158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Tsukahara T, Koyama H, Okada M, Ushida K. Stimulation of butyrate production by gluconic acid in batch culture of pig cecal digesta and identification of butyrate-producing bacteria. J Nutr. J Nutr; 2002;132:2229–34. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12163667/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Sakamoto M, Ikeyama N, Yuki M, Ohkuma M. Draft Genome Sequence of Lawsonibacter asaccharolyticus JCM 32166T, a Butyrate-Producing Bacterium, Isolated from Human Feces. Genome Announc. American Society for Microbiology (ASM); 2018;6. Available from: http://pmc/articles/PMC6013597/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Bui TPN, Shetty SA, Lagkouvardos I, Ritari J, Chamlagain B, Douillard FP, et al. Comparative genomics and physiology of the butyrate-producing bacterium Intestinimonas butyriciproducens. Environ Microbiol Rep. Environ Microbiol Rep; 2016;8:1024–37. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27717172/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Morrison DJ, Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes. Taylor & Francis; 2016;7:189–200. Available from: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Canani RB, Costanzo M, Di, Leone L, Pedata M, Meli R, Calignano A, et al. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1519–28. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barcenilla A, Pryde SE, Martin JC, Duncan SH, Stewart CS, Henderson C, et al. Phylogenetic Relationships of Butyrate-Producing Bacteria from the Human Gut. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:195–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.4.1654-1661.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Louis P, Young P, Holtrop G, Flint HJ. Diversity of human colonic butyrate-producing bacteria revealed by analysis of the butyryl-CoA: acetate CoA-transferase gene. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:304–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duncan GJ, Reid MD, Rucklidge GJ, Henderson D, Young P, Russell VJ, et al. A novel class of CoA-transferase involved in short- chain fatty acid metabolism in butyrate-producing human colonic bacteria Printed in Great Britain. Microbiology. 2006;152:179–85. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopez-Siles M, Khan TM, Duncan SH, Harmsen HJM, Garcia-Gil LJ, Flint HJ. Cultured representatives of two major phylogroups of human colonic Faecalibacterium prausnitzii can utilize pectin, uronic acids, and host-derived substrates for growth. Appl Environ Microbiol. Appl Environ Microbiol; 2012;78:420–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22101049/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Falony G, Verschaeren A, Bruycker F, De PV, De, Verbeke K. In Vitro Kinetics of Prebiotic Inulin-Type Fructan Fermentation by Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria: Implementation of Online Gas Chromatography for Quantitative Analysis of Carbon Dioxide and Hydrogen Gas Production †. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:5884–92. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00876-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang C-N, Liebl W, Ehrenreich A. Restriction-deficient mutants and marker-less genomic modification for metabolic engineering of the solvent producer Clostridium saccharobutylicum. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:264. Available from: 10.1186/s13068-018-1260-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Bui TPN, de Vos WM, Plugge CM. Anaerostipes rhamnosivorans sp. nov., a human intestinal, butyrate-forming bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol; 2014;64:787–93. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24215821/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Engels C, Ruscheweyh HJ, Beerenwinkel N, Lacroix C, Schwab C. The common gut microbe Eubacterium hallii also contributes to intestinal propionate formation. Front Microbiol Frontiers Media S A. 2016;7:713. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hashizume K, Tsukahara T, Yamada K, Koyama H, Ushida K. Megasphaera elsdenii JCM1772T normalizes hyperlactate production in the large intestine of fructooligosaccharide-fed rats by stimulating butyrate production. J Nutr American Institute of Nutrition. 2003;133:3187–90. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.10.3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferreyra JA, Wu KJ, Hryckowian AJ, Bouley DM, Weimer BC, Sonnenburg JL. Gut microbiota-produced succinate promotes C. difficile infection after antibiotic treatment or motility disturbance. Cell Host Microbe. Cell Host Microbe; 2014;16:770–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25498344/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Duncan SH, Barcenilla A, Stewart CS, Pryde SE, Flint HJ. Acetate Utilization and Butyryl Coenzyme A (CoA): Acetate-CoA Transferase in Butyrate-Producing Bacteria from the Human Large Intestine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5186–90. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.5186-5190.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duncan SH, Holtrop G, Lobley GE, Calder AG, Stewart CS, Flint HJ. Contribution of acetate to butyrate formation by human faecal bacteria. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:915–23. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morrison DJ, Mackay WG, Edwards CA, Preston T, Dodson B, Weaver LT. Butyrate production from oligofructose fermentation by the human faecal flora: what is the contribution of extracellular acetate and lactate? Br J Nutr. Cambridge University Press; 2006;96:570–7. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/article/butyrate-production-from-oligofructose-fermentation-by-the-human-faecal-flora-what-is-the-contribution-of-extracellular-acetate-and-lactate/5E4FA2F6E4F85A9033129FB3D1616A38. [PubMed]

- 40.Trachsel J, Bayles DO, Looft T, Levine UY, Allen HK. Function and Phylogeny of Bacterial Butyryl Coenzyme A:Acetate Transferases and Their Diversity in the Proximal Colon of Swine. Appl Environ Microbiol. Appl Environ Microbiol; 2016;82:6788–98. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27613689/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Khan S, Jena G. Chemico-Biological Interactions Sodium butyrate reduces insulin-resistance, fat accumulation and dyslipidemia in type-2 diabetic rat : A comparative study with metformin. Chem Biol Interact. Elsevier Ltd; 2016;254:124–34. Available from: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Khan S, Jena G. The role of butyrate, a histone deacetylase inhibitor in diabetes mellitus : experimental evidence for therapeutic intervention. Epigenomics. 2015;7:669–80. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oiso H, Furukawa N, Suefuji M, Shimoda S, Ito A, Furumai R. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications The role of class I histone deacetylase (HDAC) on gluconeogenesis in liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. Elsevier Inc.; 2011;404:166–72. Available from: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Kamp ME, Shim R, Nicholls AJ, Oliveira AC, Mason J, Binge L, et al. G Protein-Coupled Receptor 43 Modulates Neutrophil Recruitment during Acute Inflammation. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McBrayer DN, Tal-Gan Y. Recent Advances in GLP-1 Receptor Agonists for Use in Diabetes Mellitus Dominic. HHS Public Access. 2018;78:292–9. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coppola S, Avagliano C, Calignano A, Canani RB. The Protective Role of Butyrate against Obesity and Obesity-Related Diseases. Molecules. 2021;26:1–19. doi: 10.3390/molecules26030682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klok MD, Jakobsdottir S, Drent ML. The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review. Obes Rev. 2006;8:21–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han J, Lin H. Intestinal microbiota and type 2 diabetes: from mechanism insights to therapeutic perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17737–45. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagpal R, Shively CA, Register TC, Craft S, Yadav H. Gut microbiome-Mediterranean diet interactions in improving host health [ version 1; peer review : 3 approved ] F1000Research. 2020;8:1–18. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18992.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhute SS, Suryavanshi MV, Joshi SM, Yajnik CS. Gut Microbial Diversity Assessment of Indian Type-2-Diabetics Reveals Alterations in Eubacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryotes. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ejtahed H, Hoseini-tavassol Z, Khatami S, Zangeneh M, Behrouzi A. Main gut bacterial composition differs between patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes and non-diabetic adults. J Diabetes Metab Disord Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders. 2020;19:265–71. doi: 10.1007/s40200-020-00502-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhong H, Ren H, Lu Y, Fang C, Hou G, Yang Z, et al. Distinct gut metagenomics and metaproteomics signatures in prediabetics and treatment-naïve type 2 diabetics. EBioMedicine. Elsevier B.V.; 2019;47:373–83. Available from: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, Li S, Zhu J, Zhang F, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. Nature Publishing Group; 2012;490:55–60. Available from: 10.1038/nature11450. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Das T, Jayasudha R, Chakravarthy S, Prashanthi GS, Bhargava A, Tyagi M, et al. Alterations in the gut bacterial microbiome in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic retinopathy. Sci Rep. Nature Publishing Group UK; 2021;1–15. Available from: 10.1038/s41598-021-82538-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Larsen N, Vogensen FK, Berg FWJ, Van Den, Nielsen DS, Sofie A, Pedersen BK, et al. Gut Microbiota in Human Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Differs from Non-Diabetic Adults. PLoS One. 2010;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Zhang X, Shen D, Fang Z, Jie Z, Qiu X, Zhang C. Human Gut Microbiota Changes Reveal the Progression of Glucose Intolerance. PLoS One. 2013;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Behre CJ, Karlsson FH, Tremaroli V, Nookaew I, Nielsen J, Ba F. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature. 2013;498:4–10. doi: 10.1038/nature12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Candela M, Biagi E, Soverini M, Consolandi C, Quercia S, Severgnini M, et al. Modulation of gut microbiota dysbioses in type 2 diabetic patients by macrobiotic Ma-Pi 2 diet. Br J ofNutrition. 2016;116:80–93. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516001045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Forslund K, Hildebrand F, Nielsen T, Falony G, Chatelier E, Le, Arumugam M, et al. Disentangling type 2 diabetes and metformin treatment signatures in the human gut microbiota. Nature. Nature Publishing Group; 2015; Available from: 10.1038/nature15766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Tomova A, Bukovsky I, Rembert E, Yonas W, Alwarith J. The Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan Diets on Gut Microbiota. Front Nutr. 2019;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Jia W, Zhen J, Liu A, Yuan J, Wu X, Zhao P, et al. Long-Term Vegan Meditation Improved Human Gut Microbiota. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2020;2020. Available from: 10.1155/2020/9517897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. Nature Publishing Group; 2014;505:559–63. Available from: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Ruengsomwong S, Korenori Y, Sakamoto N, Wannissorn B, Nakayama J, Nitisinprasert S. Senior Thai Fecal Microbiota Comparison Between Vegetarians and Non-Vegetarians Using PCR-DGGE and Real-Time PCR. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;24:1026–33. Available from: 10.4014/jmb.1310.10043. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Haroa C, García-Carpinteroa S, Rangel-Zúñiga OA, Alcalá-Díaz JF, Landac BB, Clemented JC, et al. Consumption of two healthy dietary patterns restored microbiota dysbiosis in obese patients with metabolic dysfunction. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;1–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Nagpal R, Shively CA, Appt SA, Register TC, Michalson KT, Vitolins MZ, et al. Gut Microbiome Composition in Non-human Primates Consuming a Western or Mediterranean Diet. Front Nutr. 2018;5:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2018.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raygan F, Rezavandi Z, Bahmani F, Ostadmohammadi V. The effects of probiotic supplementation on metabolic status in type 2 diabetic patients with coronary heart disease. Diabetol Metab Syndr. BioMed Central; 2018;1–7. Available from: 10.1186/s13098-018-0353-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Moroti C, Francine L, Magri S, Costa MDR, Cavallini DCU. Effect of the consumption of a new symbiotic shake on glycemia and cholesterol levels in elderly people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Sabico S, Al-mashharawi A, Al-daghri NM, Wani K, Amer OE, Hussain DS, et al. Effects of a 6-month multi-strain probiotics supplementation in endotoxemic, in fl ammatory and cardiometabolic status of T2DM patients : A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr. Elsevier Ltd; 2019;38:1561–9. Available from: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Jia L, Li D, Fen N, Shamoon M, Sun Z. Anti-diabetic Effects of Clostridium Promoting the Growth of Gut Butyrate-producing Bacteria in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Sci Rep. 2017;1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Wang Y, Dilidaxi D, Wu Y, Sailike J, Sun X, Nabi X. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy Composite probiotics alleviate type 2 diabetes by regulating intestinal microbiota and inducing GLP-1 secretion in db / db mice. Biomed Pharmacother. Elsevier; 2020;125:109914. Available from: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109914. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Kumar M, Behare P, Mohania D, Arora S. Health-promoting probiotic functional foods. Agro Food Ind Hi Tech. 2009;29–33.

- 72.Tonucci LB, Maria K, Oliveira LL, De, Machado S, Ribeiro R, Stampini H, et al. Clinical Application of Probiotics in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Clin Nutr. Elsevier Ltd; 2015; Available from: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Razmpoosh E, Javadi A, Ejtahed HS, Mirmiran P, Javadi M, Yousefinejad A. The effect of probiotic supplementation on glycemic control and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized placebo controlled trial. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. Diabetes India; 2018; Available from: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Ahmadi S, Wang S, Nagpal R, Wang B, Jain S, Razazan A, et al. A human-origin probiotic cocktail ameliorates aging-related leaky gut and inflammation via modulating the microbiota / taurine / tight junction axis. JCI Insight. 2020;5:1–18. Available from: 10.1172/jci.insight.132055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Geirnaert A, Calatayud M, Grootaert C, Laukens D, Devriese S, Smagghe G, et al. Butyrate-producing bacteria supplemented in vitro to Crohn’s disease patient microbiota increased butyrate production and enhanced intestinal epithelial barrier integrity OPEN. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11734-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.FAO, WHO. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. Jt FAO/WHO Work Gr Rep Draft Guidel Eval Probiotics Food. 2002;1–11.

- 77.Vrieze A, Nood ELSVAN, Holleman F, Salojärvi J, Kootte RS, Bloks VW, et al. Transfer of Intestinal Microbiota From Lean Donors Increases Insulin. YGAST. Elsevier Inc.; 2012;143:913–916.e7. Available from: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Zhang L, Zhou W, Zhan L, Hou S, Zhao C, Bi T, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation alters the susceptibility of obese rats to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Aging. 2020;12:17480–502. doi: 10.18632/aging.103756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nood E, Van, Speelman P, Nieuwdorp M, Keller J. Fecal microbiota transplantation: facts and controversies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30:34–9. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Binda S, Hill C, Johansen E, Obis D, Pot B, Sanders ME, et al. Criteria to Qualify Microorganisms as “ Probiotic ” in Foods and Dietary Supplements. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Salamon D, Oleksiak AS, Kapusta P, Szopa M, Mrozińska S, Słomczyńska AHL, et al. Characteristics of gut microbiota in adult patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes based on next – generation sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene fragment. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2018;128:336–43. doi: 10.20452/pamw.4246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.