Abstract

Objectives

Glucose intolerance and insulin resistance are hallmarks of metabolic syndrome and lead to Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The purpose of this study is to elucidate the neuroprotective effect of metformin through insulin regulation with cardiometabolic and neurotransmitter metabolic enzyme regulation in high-fat, high-sucrose diet and streptozotocin (HFHS-STZ)–induced rats.

Methods

Male Wistar rats were treated with metformin (180 mg/kg and 360 mg/kg). STZ (35 mg/kg i.p.) injection was performed on the 14th day of 42 days of HFHS diet treatment. Brain neurotransmitter metabolic enzymes (acetylcholinesterase and monoamine oxidase) were determined along with sodium-potassium ATPase (Na+K+-ATPase). Plasma lipids and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was performed. Mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate and electrocardiogram (QT, QTc and RR intervals) were analysed with PowerLab.

Results

Metformin treatment significantly (p < 0.001) reduced the HOMA-IR index and decreased neurotransmitter metabolic enzymes such as AChE and MAO (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05). The lipid profile was significantly (p < 0.001) controlled with cardiometabolic functions.

Conclusions

Our investigation revealed that metformin has a remarkable role in regulating brain insulin, vascular system with monoaminergic metabolic enzymes and enhancing synaptic plasticity. Metformin may be a selective early therapeutic agent in metabolic syndrome associated with cognitive decline.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40200-022-01074-4.

Keywords: Cognitive dysfunction, Metabolic cardiovascular syndrome, Insulin resistance, Alzheimer’s disease, Metformin, Neuroprotection

Introduction

Dementia, an ageing-related disease in the elderly population, is a major concern worldwide. Globally, 35 million people are at risk for dementia [1]. The elderly population are at higher risk for diabetes and related cardiometabolic syndromes because of high-calorie diet consumption [2, 3]. Metabolic syndrome leads to glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, indicating a type II diabetic state called non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) [4, 5]. Insulin resistance with hypertrophic obesity, a condition in metabolic syndrome, is the primary mechanism for the pathological changes that lead to dementia [6, 7]. It has also been suggested that cardiac dysfunction occurs earlier than the glucose intolerance phase due to metabolic syndrome following insulin resistance [8]. Insulin regulates food consumption, energy balance, autonomic activity, peripheral insulin effects, and other processes, including cognition and memory. Insulin is involved in regulating synaptic transmission and neural proliferation [9]. The dysregulated glucose and insulin signalling in the brain mediate AD-type of neurodegeneration and is termed “brain diabetes” [10]. In Alzheimer’s disease patients, higher plasma insulin levels and lower insulin sensitivity are observed. This insulin dysfunction may lead to the onset of AD by altering the synthesis and degradation of β-amyloid. Insulin receptors (IRs) are involved in AD neuropathology. Downstream of IR signal transduction pathway may increase the synthesis of the Aβ peptide by altering amyloid precursor protein (APP) [11–14]. Many pathological indications suggest the co-morbidity of diabetes, obesity and AD [15, 16]. Acetylcholine is the principal neurotransmitter for learning and memory. Metabolic enzymes such as acetylcholinesterase and monoamine oxidase are implicated in the pathophysiology of cognitive decline during ageing [17, 18]. Diabetes and obesity are related by oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, insulin resistance and cerebral microvascular changes [19, 20]. The Na+/K+-ATPase function preserves neuronal sheath capability; it regulates the cellular ionic exchange during neuronal excitation and involves the transport process (Na+/Ca2 + exchange and vesicular movement of neurotransmitters). During neurodegeneration and AD, a substantial decrease of Na+K+-ATPase is found in various brain regions [18, 21]. These multifactorial mechanisms provide evidence that alterations in insulin sensitivity and glucose intolerance promote the risk of hippocampal memory impairment and cognitive deficits. Hence, it could be hypothesised that an insulin sensitiser may restore impaired glucose metabolism and hippocampal-dependent cognitive deficits. Metformin, a biguanide insulin sensitiser, is widely used in clinical therapy to treat and control metabolic changes associated with type 2 diabetes. It has extensive therapeutic effects, including memory enhancement, immunomodulation, and anticancer and antiobesity effects [22]. In this investigation, we evaluated metformin’s metabolic regulation and neuroprotective potential in streptozotocin treated and high-fat/high-sucrose diet-fed rats.

Methodology

Drugs and chemicals

Biochemical kits (Cholesterol, glucose, triglycerides and lipid), Acetylthiocholine iodide, sodium nitroprusside, iodide, β-phenylethylamine, serotonin and additional reagents have been acquired from Sigma Aldrich, MO, USA. Plasma insulin is determined by ELISA kit obtained from Mercodia Inc. Metformin from Aurobindo Pharma Ltd, Hyderabad, India.

Experimental animals

Wistar rats weighing 200–220 g (3–4 months old, Male) were used. Standard rodent pellet diet, Provimi Limited (India), was fed with water ad libitum to the rats. Environmental conditions of 23–25 °C, 40 to 60% humidity, and 12 h light/dark cycle were adopted one week before experimentations and maintained until the experimental period. The procedures of animal experimentations complied with directive 2010/63/EU guidelines [23] and committee for the purpose of control and supervision of experimental animals (CPCSEA: /IAEC/LCP/013/2012/WR/24), Anurag Group of Institutions, Hyderabad, India.

Design of experiment

The rats (n = 48) were separated into two sets of four groups containing 6 rats per group. The grouping of animals was performed by stratified random sampling method. Each group consist of 6 male animals. Cognitive impairment was induced upon feeding the HFHS diet for 6 weeks and injecting STZ (35 mg/kg) [24–27]. In group, I: the control, animals in the first set were fed with regular pellet food. Group II (negative control) was fed with the HFHS diet and injected with STZ. Animals in groups III and IV were treated with metformin 180 mg/kg (p.o.) and 360 mg/kg (p.o.) from the 15th day until day 42. Except for the control group, all the rats in the other 3 groups (II, III and IV) were given STZ on day 14 and fed an HFHS diet for 6 weeks. STZ was freshly prepared 5 min before the injection. The dietary ingredients in grams of the high-fat high sucrose/regular diet consisted of starch (100/500), sucrose (300/100), casein (200/200), safflower oil (100/100), tallow (200/NA), cellulose (50/50), vitamin mix (10/10), mineral mix (35/35), choline chloride (2.5/2.5) and L-methionine (3/3). Behavioural studies were performed on the 38th day, and OGTT was performed on the 39th day. On the end day of the study period, blood samples were collected through retro-orbital puncture for blood biochemical markers. Then the animals were sacrificed by the cervical dislocation method and isolated the brain under ice-cold conditions. The brain samples were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and homogenates were prepared to determine the brain biochemicals. The second set was treated as same as the first set, and the animals were used for cardiovascular investigations in PowerLab.

Pharmacological studies

Body weight and intake of food

The weight of animals and food intake were determined on days 21, 28, 35 and 42 and expressed as percentage body weight change. Cumulative food intake in grams was noted and calculated for days 7, 14, 21, 28, 35 and 42.

Morris Water maze test (MWM)

The animals were trained for 6 days, and the probe trial was conducted on day 7. In brief, the animals were trained on a water maze apparatus (width: 140 cm, Elevation:50 cm) filled with water (25 ± 1 °C) until 30 cm. A spherical platform (diameter: 10 cm) remained submerged at 1.5 cm underneath the water level in one of the four quadrants’ midpoint. During training sessions for 5 repeated days with 4 trials in one day, the animals were guided to climb onto the platform. After treatment with the test drug, the escape latency of the animals was assessed in the water maze [28].

Open-field habituation memory

Animals were allowed to explore in a 50 cm × 50 cm × 45 cm open arena. It consists of brown linoleum base flooring and is equally partitioned into 16 squares. In training and test evaluation, the rats were ported in the left rear square to reconnoitre for 5 min. The line crossings and nose poking were counted [29, 30].

Alternation test on Y-Maze

The maze device consists of three arms (75 cm × 25 cm ×15 cm) encompassing the mid platform and angled apart 120° [31]. The animals were observed for 8 min, allowing them to explore from the marked end of one arm freely. The arm entry sequence was recorded. The interchange of animals into the different 3 arms was accounted (A, B or C), and the alternation was calculated in percentage.

Biochemical parameters

Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

Plasma samples were prepared to determine the glucose concentration. Retro-orbital puncture was made for blood collection at following intervals (0, 30, 60, and 120 min) post-glucose loading [32]. The area under curve (AUC) was obtained from: AUC = 0.25 × A + 0.5 × B + 0.75 × C + 0.5 × D (A, B, C and D signify the plasma glucose concentration at time intervals).

Determination of plasma biochemical markers

Plasma glucose, triglycerides (TGs), cholesterols such as low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), total cholesterol (TC) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) were evaluated using a semi-automated analyser (Optima-S, Lab India). ELISA kit (Mercodia Inc) was used for plasma insulin determination. Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) was calculated [32]. HOMA-IR = plasma glucose (fasting) × plasma insulin level/405.

Determination of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme

AChE activity in the brain tissue was estimated by the dithiobisnitrobenzoate reaction technique [23]. The rate of thiocholine formation from acetylthiocholine iodide by the enzymatic reaction of brain cholinesterase (in brain homogenate) is quantified spectrophotometrically at 420 nm (Shimadzu-UV-1800) [33].

Determination of monoamine oxidase enzymes

The mitochondrial fraction of the brain was prepared, and MAO action was estimated spectrophotometrically [34]. The reactive blend included 4 mM serotonin or 2 mM β-phenylethylamine as substrates for MAO-A and B. After the reaction, the MAO-A & B were separated organically using 5 ml butyl acetate and 5 ml cyclohexane. Then the organic phases were read on a spectrometer at 280 nm for MAO-A and 242 nm for MAO-B.

Determination of membrane-bound Na+/K+-ATPase

The Na+/K+-ATPase activity in the brain homogenate was determined spectrophotometrically. [35]. In this determination, 0.2 ml of brain homogenate was incubated with Tris-HCl buffer containing 10 mM of ATP. Then 10% TCA was added to complete the reaction. Then the amount of Pi (phosphate) released by the protein-free supernatant was calculated.

Determination of antioxidants

Brain homogenates (10%) were experimented for determining the antioxidant biomarkers. The pyrogallol auto-oxidation method was employed to evaluate superoxide dismutase (SOD) [36]. The glutathione oxidation method was used to quantify the glutathione peroxidase (GPx) enzyme [37]. Catalase (CAT) was measured through the reaction of ammonium molybdate with the brain homogenate and determined spectrophotometrically [38].

Electrocardiogram (ECG) and BP measurements

The rats were anaesthetised under urethane at a dose of 1.5 g/kg i.p. and prepared for the PowerLab (ML408) using LabChart 7.0 (AD Instruments, Australia). The anaesthetised animals were cannulated through the carotid artery with a BP transducer (MLT0380), which was prefilled with heparinised saline, and ECG was recorded using needle electrodes (MLA1203). QTc, PR, RR intervals and heart rate were measured [32].

Statistical analysis

The statistics were expressed as mean ± standard error mean. The data were subjected to one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The data reflecting with P < 0.05 was considered to exhibit statistical significance using the Graph Pad Prism 6.0 software.

Results

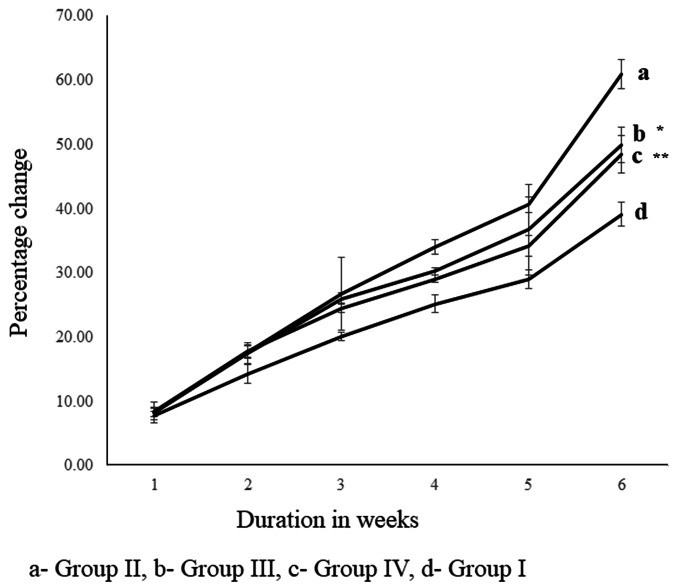

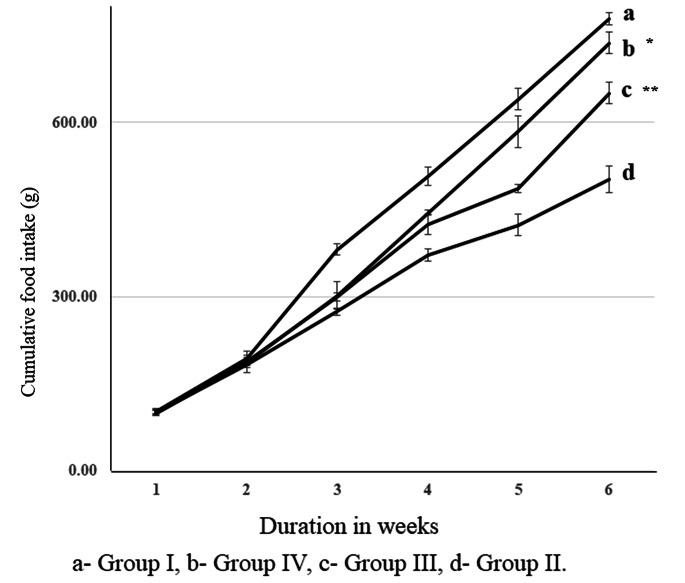

Metformin on percentage body weight gain and cumulative food intake

HFHS-STZ increased the body weight significantly (p < 0.001) in percentage weight gain at 21, 28, 35 and 42 days. In the 180 and 360 mg/kg metformin treatment (Groups III and IV), there was a substantial weight control with p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 (Fig. 1). In negative control HFHS-STZ treatment alone significantly (p < 0.001) decreased cumulative food intake observed on days 7, 14, 21, 28, 35 and 42. The administration of metformin in groups III & IV (180 and 360 mg/kg) elevated the cumulative food intake (grams) significantly (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01) at days 28, 35 and 42 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Body weight

Fig. 2.

Food intake

Effect of metformin on water maze behaviour

The duration of escape latency in the HFHS-STZ alone treated group was significantly (p < 0.001) increased and indicated the deterioration of the hippocampal memory (Table 1). Administration of metformin at both doses (180 and 360 mg/kg) significantly (p < 0.01) improved hippocampal learning and memory.

Table 1.

Effect of metformin on behavioural parameters

| Group | Water Maze (s) | Open field exploration (Counts/ 5 mts) | Y Maze (s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head dip | Rearing | Line crossing | % Alternation | ||

| I (Control) | 59.67 ± 3.98 | 10.33 ± 1.14 | 19.83 ± 1.10 | 29.00 ± 2.36 | 51.40 ± 3.68 |

| II (HS) | 121.7 ± 13.16a | 4.16 ± 0.98b | 9.33 ± 0.91a | 10.00 ± 1.12a | 25.62 ± 2.64a |

| III (HS + Met 180 mg) | 72.50 ± 8.22d | 8.33 ± 1.14c | 14.00 ± 0.93c | 17.33 ± 2.06 | 34.61 ± 2.26 |

| V (HS + Met 360 mg) | 63.83 ± 9.63d | 10.83 ± 0.79e | 18.00 ± 1.26e | 24.83 ± 2.57e | 45.94 ± 5.48d |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of 6 animals. Superscript letters represent the statistical significance performed by ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. ap < 0.001 and bp < 0.01 indicates the comparison of Group II with Group (I) cp < 0.05, dp < 0.01 and ep < 0.001, indicates the significance on comparing group III or IV with group (II) (HS- high fat-high sucrose and Streptozotocin, Met- Metformin)

Effect of metformin on open-field exploration

The HFHS-STZ–induced cognitive impairment in group II demonstrated a significant dropping in head dips (p < 0.01), rearing and line crossings (p < 0.001). Metformin treatment at a dose of 180 mg/kg improved the habituation memory by significantly hovering the activity of head dippings and rearings (p < 0.05). However, it was noticed that there was no improvement observed in line crossings. The treatment of 360 mg/kg metformin in animals exhibited a significant (p < 0.001) improvement on all three assessments of open-field habituation memory (Table 1).

Effect of metformin on Y-Maze test

In the Y-maze test, the negative control group displayed impaired alternation. It was significantly (p < 0.01) impaired than the control group treated with saline. In animals treated with the higher dose of metformin (360 mg/kg), the percentage of alternation displayed significant (p < 0.01) improvement and indicated that high-dose metformin is therapeutically active in reversing HFHS-STZ–induced cognitive dysfunction (Table 1).

Biochemical parameters

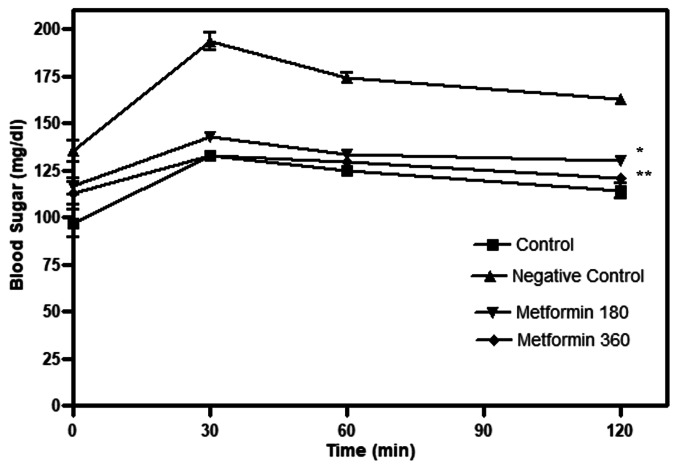

Effect of metformin on OGTT

Fasting glucose levels were significantly (p < 0.01) higher in the HFHS–STZ–fed group compared to the control group. Metformin treatment with both doses significantly (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01) reduced fasting glucose compared to the HFHS-STZ group. The glucose levels in both treated groups had returned to fasting levels in 2 h (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Oral glucose tolerance test

Effect of metformin on plasma glucose, insulin resistance and biochemical markers

Treatment with metformin 180 and 360 mg/kg significantly (p < 0.01) reduced the day-end fasting glucose levels (Table 2). Metformin treatment at 180 and 360 mg/kg significantly (p < 0.01) reduced the AUC to 20.09% and 25.5%, respectively. The HOMA-IR score was significantly (p < 0.001) elevated in negative control animals when assessed with the control group. Treatment of metformin regulated significantly (p < 0.001), with an indication of a low index of HOMA-IR at both 180 and 360 mg/kg. In the lipid and biochemical profiles, group II exhibited a significant (P < 0.001) elevation in TC, TGs and LDL-C levels. Insulin levels in the HFHS-STZ group dropped to a lower level on comparing to the control. It was also noted with a significant (p < 0.001) reduction in HDL-C. The insulin turnover was exhibited significantly in the 360 mg/kg metformin-treated group (p < 0.001). The TC was significantly (p < 0.01) controlled in both metformin (180 and 360 mg/kg) administered groups. The TGs and LDL-C were found to be regulated well to normal, and the effect was significant (p < 0.001). There was a substantial (p < 0.05) increase in HDL-C at 180 mg/kg, and in the case of 360 mg/kg, there was a remarkable (p < 0.001) improvement in HDL-C.

Table 2.

Effect of metformin on glucose, insulin and lipid profile

| Group | Glucose (mg/dl) | Insulin (µg/L) | HOMA-IR | AUC (h.mg/l) |

Cholesterol (mg/dl) | Triglycerides (mg/dl) | HDL (mg/dl) | LDL (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (Control) | 93.68 ± 4.21 | 18.74 ± 0.70 | 4.31 ± 0.16 | 241.30 ± 3.59 | 87.60 ± 5.05 | 98.24 ± 5.96 | 44.33 ± 2.97 | 38.01 ± 3.08 |

| II (HS) | 364.50 ± 33.40a | 12.52 ± 0.54a | 11.24 ± 1.29a | 342.60 ± 3.47a | 122.30 ± 2.11a | 178.10 ± 7.44a | 26.61 ± 2.03a | 97.13 ± 4.12a |

| III (HS + Met 180mg) | 179.30 ± 21.91e | 14.46 ± 0.46 | 6.32 ± 0.63e | 265.70 ± 1.88e | 93.93 ± 5.11d | 115.90 ± 6.25e | 37.67 ± 2.87c | 58.86 ± 6.33e |

| V (HS + Met 360mg) | 106.30 ± 7.65e | 16.39 ± 0.56e | 4.27 ± 0.28e | 252.20 ± 2.78e | 92.15 ± 7.11d | 101.80 ± 6.67e | 46.40 ± 2.59e | 41.16 ± 4.44 e |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of 6 animals. Superscript letters represent the statistical significance performed by ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. ap < 0.001 indicates the comparison of Group II with Group I. cp < 0.05, dp < 0.01 and ep < 0.001, indicates the significance on comparing group III or IV with group II. (HS- high fat-high sucrose and Streptozotocin, Met- Metformin)

Effect of metformin on acetylcholinesterase enzyme

The induction of cognitive deficits in high fat treated HSHF-STZ (group II) revealed a significant elevation in AChE (p < 0.001), which is assessed with the control group. In the drug administration groups, 180 and 360 mg/kg metformin (III and IV) controlled the AChE and indicated significant reduction (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01) correspondingly. The reduction in AChE was depicted when compared to HFHS-STZ treated group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of metformin on neurotransmitter metabolic enzyme and antioxidants

| Groups | AChE | MAO A | MAO B | Na+/K + ATPase (µm Pi Liberated/mg protein) | SOD | GPx | Catalase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (µmol/min/mg) | (nmol/mg protein.h) | (U/min/mg protein) | (U/mg protein) | ||||

| I (Control) | 12.01 ± 0.99 | 14.20 ± 1.30 | 15.30 ± 1.39 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 7.44 ± 1.49 | 38.70 ± 1.54 | 2.21 ± 0.10 |

| II (HS) | 24.19 ± 2.75a | 25.75 ± 1.01a | 23.48 ± 1.32b | 0.25 ± 0.02a | 1.81 ± 0.32b | 17.66 ± 1.27a | 0.78 ± 0.10a |

| III (HS + Met 180 mg) | 15.42 ± 1.55c | 19.14 ± 1.03c | 15.30 ± 1.36d | 0.46 ± 0.04c | 6.45 ± 0.93c | 29.07 ± 2.94d | 1.84 ± 0.24d |

| V (HS + Met 360 mg) | 13.03 ± 1.64d | 18.99 ± 1.88c | 16.32 ± 1.69c | 0.53 ± 0.06d | 6.88 ± 1.24c | 32.49 ± 2.02e | 2.16 ± 0.18e |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of 6 animals. Superscript letters represent the statistical significance performed by ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. ap < 0.001 and bp < 0.01 indicates the comparison of Group II with Group (I) cp < 0.05, dp < 0.01 and ep < 0.001, indicates the significance on comparing group III or IV with group (II) (HS- high fat-high sucrose and Streptozotocin, Met- Metformin)

Effect of metformin on MAO enzymes

The neurotransmitter metabolic enzymes MAO A & B in the brain were significantly (p < 0.001 & p < 0.01) escalated after HFHS-STZ administration. In the metformin 180 mg/kg–treatment group, the MAO-A & B enzymes exhibited a significant control (p < 0.05 & p < 0.01) in the metabolic deficits induced animals. However, in 360 mg/kg metformin-treated animals a brief significant (p < 0.05) reduction was noted (Table 3).

Effect of metformin on Na+K+-ATPase

In the HFHS-STZ–induced animals, a significant (p < 0.001) disruption in membrane-bound plasticity is noted. The levels have been decreased when compared to the control animals. In the case of the treatment groups (metformin 180 and 360 mg/kg) the membrane integrity is improved by enhancing the membrane-bound ATPase significantly (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01). This result indicates the neuroprotective property of metformin doses. The levels of Na+K+-ATPase are depicted in Table 3.

Effect of metformin on antioxidants

The assessment of antioxidant activity in HFHS-STZ–administered and metformin-treated rats exhibited the potential effect of metformin as a neuroprotectant (Table 3). All the brain antioxidant levels in negative control animals were significantly reduced (p < 0.001) than in the control group. There was a significant increase in SOD, GPx and CAT. The metformin at 180 mg/kg shown the significant improvement (p < 0.05, p < 0.01 and p < 0.01) respectively in SOD, GPx and CAT. In the case of treatment with 360 mg/kg metformin, there was a significant (p < 0.05) increase in SOD. The antioxidants such as GPx and CAT exhibited remarkable effects against neurotoxicity and significantly improved cognitive function (p < 0.001).

Effect of metformin on heart rate, mean arterial pressure and electrocardiogram (ECG)

The HFHS-STZ–treated group, exhibited a significant increase in blood pressure (MAP), HR and alteration of ECG intervals (QT, QTc and RR). In the treatment groups, metformin administered at 180 and 360 mg/kg significantly controlled the elevated MAP and HR. It was noted that treatment of metformin 180 mg/kg revealed a significant (p < 0.05) difference and the group treated with 360 mg/kg had markedly reduced MAP and HR with a significant difference (p < 0.001). The comparisons were made with the negative control group. The QT interval and QTc interval were significantly (p < 0.05 and p < 0.001) controlled to normal among animals administered with 180 and 360 mg/kg metformin, respectively. In the case of the RR interval, there was a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in animals administered with the lower strength of metformin, and high-dose treatment exhibited even greater significance (p < 0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of metformin on cardiovascular parameters (ECG, Blood Pressure and Mean Arterial Pressure)

| Parameters | I (Control) | II (HS) | III (HS + Met 180) | IV (HS + Met 360) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QT interval (sec) | 0.04930 ± 0.0004 | 0.08232 ± 0.002a | 0.06910 ± 0.003c | 0.06109 ± 0.002d |

| QTc interval (sec) | 0. 1233 ± 0.004 | 0.1981 ± 0.007a | 0.1896 ± 0.008c | 0.1521 ± 0.006d |

| RR interval (sec) | 0.1300 ± 0.0039 | 0.1998 ± 0.0128a | 0.1846 ± 0.007b | 0.1505 ± 0.007c |

| Heart rate (BPM) | 388.8 ± 6.19 | 455.0 ± 10.24a | 404.8 ± 7.37b | 390.9 ± 5.88d |

| MAP (mm of Hg) | 107.4 ± 3.22 | 138.9 ± 4.21a | 127.7 ± 3.22b | 116.4 ± 2.79d |

Data are expressed as Mean ± SEM (n = 6), ap < 0.001 represents the significant difference when compared with the group (I) bp < 0.05, cp < 0.01, dp < 0.001 represent significant difference when compared with the group (II) (HS- high fat-high sucrose and Streptozotocin, Met- Metformin)

Discussion

Currently, unravelling the impact of hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance during the pathogenesis of AD-associated dementia is highly focused. It is assumed that altered insulin balance and homeostasis in the brain are due to changes in peripheral glucose homeostasis and accompanying pathophysiology related to metabolic disorders [39, 40]. Brain lesions are associated with cardiometabolic co-morbidities such as hypertension, obesity and diabetes. During neurodegeneration, there is a strong association between inflammation and insulin resistance.

At the cellular level, proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β are elevated. Evidence suggests that NLRP3 (nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain-like receptor) inflammasome activation occurs with chronic inflammation. Studies have found that NLRP3-deficient animals are unaffected by high-fat diet (HFD) induced insulin resistance [41]. The NLRP3 inflammasome also induces neurodegeneration in conditions with metabolic syndrome [42]. Previous studies have shown that rats fed with HFD developed cognitive impairment and memory deficits [43] due to insulin resistance and glucose intolerance [44]. Hence, insulin sensitisers ameliorate the reduced insulin sensitivity and improve cognitive performance; the antidiabetic drug metformin was investigated in HFHS-STZ-induced metabolic complications and cognitive dysfunction in rats. As it is a biguanide insulin sensitiser, it is widely used in clinical therapy to treat and control metabolic changes associated with NIDDM. Metformin has also been reported to exhibit neuroprotection [22, 45–48]. An in vitro study on the neuronal cell line Neuro-2a concluded that metformin regulated neuronal insulin resistance and AD-associated neuropathological changes [49]. Metformin may also inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome in ApoE mice [50].

In the present study, long-term high-energy and low STZ in animals induced cognitive impairment as assessed by various behavioural parameters. Behavioural studies with the water maze, open field exploration and Y-maze tests indicated that the HFHS diet with STZ injection significantly induced memory impairment and reduced behavioural learning. Treatment with metformin improved learning and memory in behavioural parameters. MWM assessment is well-recognised for hippocampal memory determination [51]. Spatial learning and memory performance fail due to integrity loss between cholinergic innervations of the hippocampus and cortex [52, 53]. In this study, treatment with metformin alleviated the memory impairment induced by HFHS-STZ and revealed neuroprotection, especially of hippocampal memory. The open-field habituation test enhances the locomotion of rodents with improved exploratory behaviour, which can be assessed by head dips, line crossing and rearing behaviour [54]. Metformin treatment amplified habituation memory in HFHS-STZ–induced neurodegeneration. The Y-maze test evaluates spatial working and long-term memory, which signify the intact function of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus [55, 56]. In the present study, it was very evident that spatial learning in the Y-maze significantly improved the alternation behaviour after metformin treatment.

Our findings revealed that HFHS-STZ–treated animals experienced a progressive increase in body weight with characteristic hypertrophic obesity and dyslipidaemia. Moreover, the animals also exhibited a hyperglycaemic state. It has been shown that in hypertriglyceridemic and obese conditions, cerebral blood flow in prefrontal regions is severely affected, which disrupts reflex memory with loss of brain alternation memory, reasoning and executive function [57]. The chronic hyperglycaemia resulting from diabetes leads to oxidative stress, neuronal damage, inflammatory response, altered insulin signalling, cognitive deficits and disrupts the synaptic plasticity [58–60]. In our study, the administration of HFHS-STZ induced significant changes in body weight and food intake. The cumulative food intake was reduced, indicating metabolic dysfunction with insulin resistance, altered glycaemic control and lipid imbalance associated with cognitive dysfunction.

Treatment with metformin regulated the altered biochemical changes and demonstrated a protective effect with improved cognitive function. In Alzheimer’s-type dementia, neurotransmitter metabolic enzymes such as AChE and MAO are elevated and considered the primary neuropathology causing cognitive dysfunction [61, 62]. The metabolic dysfunction induced by HFHS-STZ increased the enzymes that impacted cognitive dysfunction in this study. Various studies have also indicated the remarkable influence of neurotransmitter metabolic enzymes on cognitive dysfunction in obesity and diabetes mellitus conditions [63]. Brain neurotransmitter metabolic enzymes (AChE and MAO) were reduced in this investigation. The reduced levels of neurotransmitter metabolic enzymes indicate indirect regulation and improvement of neurotransmitters to enhance cognitive function. Oxidative stress and altered synaptic plasticity are frequently observed in aged individuals with diabetes/obesity conditions. Oxidative stress in cognitive dysfunction is marked by low levels of GPx, SOD, catalase and other antioxidant defence enzymes. Metformin treatment improved cognitive function by inhibiting the AChE and MAO-A & B enzymes [45]. It has also been reported that metformin exhibited neuroprotective effects in early clinical trials with diabetic patients [64]. This research revealed that the pharmacotherapeutic management of diabetes and cardiometabolic complications with metformin would be highly strategic and clinically protect or delay the incidence of cognitive decline during ageing. In our studies, the investigations were extended to the cardiometabolic disorder, in which the interlinked parameters of cardiovascular components associated with diabetes and obesity were explored. In the present study, oxidative stress was identified in rats fed with the HFHS-STZ diet, which is indicated by a significant decrease in SOD, catalase and GPx levels in the brain. Previous studies have demonstrated that metformin protects the brain against the oxidative imbalance promoted by type 2 diabetes [45]. Synaptic plasticity correlates to the Na+/K+-ATPase, and during AD, it is disrupted [65]. Our results are consistent that metformin treatment improved the antioxidant defence mechanism and synaptic plasticity mediated in the brain. This implies a significant increase in brain antioxidant markers such as SOD, catalase and GPx, especially at the optimum metformin dose. The improved antioxidant defence mechanisms protect synaptic plasticity and indicate that metformin acts as a neuroprotectant.

HFHS-STZ treatment also induced a significant increase in blood pressure and intensified cardiovascular changes, which are considered risk factors for late-stage dementia apart from neuropathological changes. Recent studies suggest that obese patients are at higher risk of diabetic-cardiovascular complications, pulmonary disease, and apnoea. Accumulating evidence strongly suggests that conditions that raise the risk of vascular disorders (e.g., midlife high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes and cerebrovascular lesions) also have a pathogenic role in dementia disorder [66]. Hypertension is also considered one of the modifiable risk factors for AD [67]. Lower diastolic and very high systolic pressure is related to metabolic syndrome in older adults and contributes to AD [68, 69]. The cardiovascular changes in HFHS-STZ led to high blood pressure and significant fluctuations in ECG parameters, which demonstrates the correlation between cardiovascular risk and dementia. Treatment with metformin reduced the incidence of cardiovascular aggravation and was found to regulate blood pressure, heart rate, QT interval, QTc interval and RR interval. Although metformin is not an antihypertensive drug, it is believed to regulate vascular effects influenced by insulin regulation. It has also been suggested that metformin regulates blood pressure in STZ-induced rats through vascular-mediated effects [70, 71].

In our study, metformin reversed learning and memory deficits by modifying peripheral insulin resistance, as evidenced by improved insulin sensitivity and decreased plasma glucose, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels. It is evident that metformin primarily improves insulin regulation. Insulin plays a pivotal role in hippocampal neurogenesis. HFHS diet alters the brain insulin transportations and impacts the brain insulin receptors, and causes oxidative stress. Moreover, metformin attenuated the brain mitochondrial dysfunction and improved the antioxidant biomarkers. The cardiometabolic protection of metformin is demonstrated by lowering the blood pressure, controlling the haemodynamic parameters and suggesting that metformin could improve the microvascular function. It is also revealed that metformin ameliorated brain AChE and MAO levels and improved synaptic plasticity through the Na+/K+-ATPase pump regulating oxidative defence markers. Metformin could be a preferred pharmacotherapeutic treatment strategy for age-related dementia associated with metabolic disorders and complex cardiovascular diseases.

Conclusions

This investigation revealed the remarkable neuroprotective effect of metformin and suggested that treatment with metformin in metabolic syndrome conditions prevents cognitive decline. The pharmacotherapeutic effect may be due primarily to insulin regulation and the regulatory control mechanisms of vascular dysfunction with neuroinflammation. NLRP3 inhibition may contribute to the cognitive improvement in animals with HFHS-STZ–induced neurodegeneration. Further research is required to elucidate the role of metformin in NLRP3-mediated signal transduction in obesity-induced cognitive dysfunction with metabolic syndrome.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors express great appreciation to Anurag University, Hyderabad, India, and the Faculty of Pharmacy, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Malaysia, for their support in the research facility.

Declarations

Declaration of conflict of interest

The corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest among all authors.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: In the original publication of the article, the table 2 was incorrectly processed. The corrected Table 2 is provided below.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

7/24/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s40200-023-01229-x

References

- 1.Wilson B, Geetha KM. Neurotherapeutic applications of nanomedicine for treating Alzheimer’s disease. J Control Release. 2020;325:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wahl D, Solon-Biet SM, Cogger VC, Fontana L, Simpson SJ, Le Couteur DG, Ribeiro RV. Aging, lifestyle and dementia. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;130:104481. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeh SH-H, Shie F-S, Liu H-K, Yao H-H, Kao P-C, Lee Y-H, et al. A high-sucrose diet aggravates Alzheimer’s disease pathology, attenuates hypothalamic leptin signaling, and impairs food-anticipatory activity in APPswe/PS1dE9 mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2020;90:60–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou C, Qin Y, Chen R, Gao F, Zhang J, Lu F. Fenugreek attenuates obesity-induced inflammation and improves insulin resistance through downregulation of iRhom2/TACE. Life Sci. 2020;258:118222. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodie LN, Johnson RM, Ahmed B, Fowler S, Haynes W, Carmona B, et al. Western diet-induced obesity disrupts the diurnal rhythmicity of hippocampal core clock gene expression in a mouse model. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:815–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nisoli E, Carruba MO. Emerging aspects of pharmacotherapy for obesity and metabolic syndrome. Pharmacol Res. 2004;50:453–69. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farooqui AA. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s disease. Insulin Resistance as a Risk Factor Visceral Neurological Disorders; 2020. p. 249–292. 10.1016/B978-0-12-819603-8.00006-7.

- 8.Celentano A, Vaccaro O, Tammaro P, Galderisi M, Crivaro M, Oliviero M, et al. Early abnormalities of cardiac function in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:1173–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)80330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van der Heide LP, Ramakers GMJ, Smidt MP. Insulin signaling in the central nervous system: Learning to survive. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;79:205–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera J, Cannon E, Neely JL, Tavares TR, et al. Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease – is this type 3 diabetes? J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2005;7:63–80. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2005-7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imamura T, Yanagihara YT, Ohyagi Y, Nakamura N, Iinuma KM, Yamasaki R, et al. Insulin deficiency promotes formation of toxic amyloid-β42 conformer co-aggregating with hyper-phosphorylated tau oligomer in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;137:104739. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubey SK, Lakshmi KK, Krishna KV, Agrawal M, Singhvi G, Saha RN, et al. Insulin mediated novel therapies for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci. 2020;249:117540. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhtar A, Sah SP. Insulin signaling pathway and related molecules: Role in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int. 2020;135:104707. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tyagi A, Mirita C, Taher N, Shah I, Moeller E, Tyagi A, et al. Metabolic syndrome exacerbates amyloid pathology in a comorbid Alzheimer’s mouse model. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866:165849. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu T-B, Zhang Z, Luo P, Wang S-S, Peng Y, Chu S-F, et al. Lipid metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Bull. 2019;144:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pugazhenthi S, Qin L, Reddy PH. Common neurodegenerative pathways in obesity, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863:1037–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanish Singh JC, Alagarsamy V, Diwan PV, Sathesh Kumar S, Nisha JC, Narsimha Reddy Y. Neuroprotective effect of Alpinia galanga (L.) fractions on Aβ(25–35) induced amnesia in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;138:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar P, Baquer N. Alterations of metabolic parameters and antioxidant enzymes in diabetic aging female rat brain: Neuroprotective role of metformin. J Neurol Sci. 2017;381:573. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.08.1613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebrahimpour S, Zakeri M, Esmaeili A. Crosstalk between obesity, diabetes, and alzheimer’s disease: Introducing quercetin as an effective triple herbal medicine. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;62:101095. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cholerton B, Baker LD, Craft S. Insulin, cognition, and dementia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;719:170–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liguri G, Taddei N, Nassi P, Latorraca S, Nediani C, Sorbi S. Changes in Na+,K+-ATPase, Ca2+-ATPase and some soluble enzymes related to energy metabolism in brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 1990;112:338–42. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90227-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shurrab NT, Arafa E-SA, Metformin A review of its therapeutic efficacy and adverse effects. Obes Med. 2020;17:100186. doi: 10.1016/j.obmed.2020.100186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guillen J, Prins J-B, Smith D, Degryse A-D. The European Framework on Research Animal Welfare Regulations and Guidelines. Lab Anim. Elsevier; 2014. pp. 117–88. 10.1016/B978-0-12-397856-1.00005-2.

- 24.Gheibi S, Kashfi K, Ghasemi A. A practical guide for induction of type-2 diabetes in rat: Incorporating a high-fat diet and streptozotocin. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95:605–13. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srinivasan K, Viswanad B, Asrat L, Kaul CL, Ramarao P. Combination of high-fat diet-fed and low-dose streptozotocin-treated rat: A model for type 2 diabetes and pharmacological screening. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52:313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Sun X, Zhang N, Ji Z, Ma Z, Fu Q, et al. Ferulic acid attenuates diabetes-induced cognitive impairment in rats via regulation of PTP1B and insulin signaling pathway. Physiol Behav. 2017;182:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wongchitrat P, Lansubsakul N, Kamsrijai U, Sae-Ung K, Mukda S, Govitrapong P. Melatonin attenuates the high-fat diet and streptozotocin-induced reduction in rat hippocampal neurogenesis. Neurochem Int. 2016;100:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh HJC, Syeda TUB, Kakalij RM, Prasad VVLN, Diwan PV. Erythropoietin protects polychlorinated biphenyl (Aroclor 1254) induced neurotoxicity in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;707:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanish Singh JC, Muralidharan P, Narsimha Reddy Y, Sathesh Kumar S, Alagarsamy V. Anti-amnesic effects of Evolvulus alsinoides Linn. in amyloid β (25–35) induced neurodegeneration in mice. Pharmacologyonline. 2009;1:70–80. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gould TD, Dao DT, Kovacsics CE. The open field test. In: Gould T, editor. Mood and Anxiety Related Phenotypes in Mice. Neuromethods. Totowa: Humana Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdulbasit A, Stephen Michael F, Shukurat Onaopemipo A, Abdulmusawwir A-O, Aminu I, Nnaemeka Tobechukwu A, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor activation selectively influence performance of Wistar rats in Y-maze. Pathophysiology. 2018;25:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kshirsagar RP, Kothamasu MV, Patil MA, Reddy GB, Kumar BD, Diwan PV. Geranium oil ameliorates endothelial dysfunction in high fat high sucrose diet induced metabolic complications in rats. J Funct Foods. 2015;15:284–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.03.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh JCH, Alagarsamy V, Parthiban P, Selvakumar P, Reddy YN. Neuroprotective potential of ethanolic extract of Pseudarthria viscida (L) Wight and Arn against beta-amyloid(25–35)-induced amnesia in mice. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2011;48:197–201. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21793312. [PubMed]

- 34.Hanish Singh JC, Alagarsamy V, Sathesh Kumar S, Narsimha Reddy Y. Neurotransmitter Metabolic Enzymes and Antioxidant Status on Alzheimer’s Disease Induced Mice Treated with Alpinia galanga (L.) Willd. Phyther Res. 2011;25:1061–7. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arivazhagan P, Panneerselvam C. Effect of DL- α -Lipoic Acid on the Status of Lipids and Membrane-Bound ATPases in Various Brain Regions of Aged Rats. J Anti Aging Med. 2002;5:335–43. doi: 10.1089/109454502763485458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marklund S, Marklund G. Involvement of the Superoxide Anion Radical in the Autoxidation of Pyrogallol and a Convenient Assay for Superoxide Dismutase. Eur J Biochem. 1974;47:469–474. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03714.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Lawrence RA, Burk RF. Glutathione peroxidase activity in selenium-deficient rat liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;71:952–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(76)90747-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Góth L. A simple method for determination of serum catalase activity and revision of reference range. Clin Chim Acta. 1991;196:143–51. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(91)90067-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim B, Elzinga SE, Henn RE, McGinley LM, Feldman EL. The effects of insulin and insulin-like growth factor I on amyloid precursor protein phosphorylation in in vitro and in vivo models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;132:104541. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kellar D, Craft S. Brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:758–66. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30231-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalupahana NS, Moustaid-Moussa N, Claycombe KJ. Immunity as a link between obesity and insulin resistance. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pirzada RH, Javaid N, Choi S. The Roles of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Neurodegenerative and Metabolic Diseases and in Relevant Advanced Therapeutic Interventions. Genes (Basel) 2020;11:131. doi: 10.3390/genes11020131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saiyasit N, Chunchai T, Apaijai N, Pratchayasakul W, Sripetchwandee J, Chattipakorn N, et al. Chronic high-fat diet consumption induces an alteration in plasma/brain neurotensin signaling, metabolic disturbance, systemic inflammation/oxidative stress, brain apoptosis, and dendritic spine loss. Neuropeptides. 2020;82:102047. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2020.102047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winocur G, Greenwood CE, Piroli GG, Grillo CA, Reznikov LR, Reagan LP, et al. Memory impairment in obese Zucker rats: An investigation of cognitive function in an animal model of insulin resistance and obesity. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:1389–95. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.5.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pintana H, Apaijai N, Pratchayasakul W, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn SC. Effects of metformin on learning and memory behaviors and brain mitochondrial functions in high fat diet induced insulin resistant rats. Life Sci. 2012;91:409–14. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meuillet EJ, Wiernsperger N, Mania-Farnell B, Hubert P, Cremel G. Metformin modulates insulin receptor signaling in normal and cholesterol-treated human hepatoma cells (HepG2) Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;377:241–52. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Docrat TF, Nagiah S, Naicker N, Baijnath S, Singh S, Chuturgoon AA. The protective effect of metformin on mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetic mice brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;875:173059. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanokashira D, Kurata E, Fukuokaya W, Kawabe K, Kashiwada M, Takeuchi H, et al. Metformin treatment ameliorates diabetes-associated decline in hippocampal neurogenesis and memory via phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1. FEBS Open Bio. 2018;8:1104–1118. Available from: 10.1002/2211-5463.12436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Gupta A, Bisht B, Dey CS. Peripheral insulin-sensitiser drug metformin ameliorates neuronal insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s-like changes. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:910–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang G, Duan F, Li W, Wang Y, Zeng C, Hu J, et al. Metformin inhibited Nod-like receptor protein 3 inflammasomes activation and suppressed diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis in apoE–/– mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;119:109410. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lleo A, Greenberg SM, Growdon JH. Current Pharmacotherapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:513–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orta-Salazar E, Cuellar-Lemus CA, Díaz-Cintra S, Feria-Velasco AI. Cholinergic markers in the cortex and hippocampus of some animal species and their correlation to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol. 2014;29:497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kar S, Slowikowski SPM, Westaway D, Mount HTJ. Interactions between beta-amyloid and central cholinergic neurons: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004;29:427–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sweatt JD. Rodent Behavioral Learning and Memory Models. Mech Mem. Elsevier; 2010. pp. 76–103. 10.1016/B978-0-12-374951-2.00004-4.

- 55.Reisel D, Bannerman DM, Schmitt WB, Deacon RMJ, Flint J, Borchardt T, et al. Spatial memory dissociations in mice lacking GluR1. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:868–73. doi: 10.1038/nn910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kraeuter A-K, Guest PC, Sarnyai Z. The Y-Maze for Assessment of Spatial Working and Reference Memory in Mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2019. p. 105–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Nota MHC, Vreeken D, Wiesmann M, Aarts EO, Hazebroek EJ, Kiliaan AJ. Obesity affects brain structure and function- rescue by bariatric surgery? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;108:646–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lutsey PL, Steffen LM, Stevens J. Dietary Intake and the Development of the Metabolic Syndrome. Circulation. 2008;117:754–61. doi: 10.1161/Circulationaha.107.716159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peplies J, Börnhorst C, Günther K, Fraterman A, Russo P, Veidebaum T, et al. Longitudinal associations of lifestyle factors and weight status with insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) in preadolescent children: the large prospective cohort study IDEFICS. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:97. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0424-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu W-C, Wei J-N, Chen S-C, Fan K-C, Lin C-H, Yang C-Y, et al. Progression of insulin resistance: A link between risk factors and the incidence of diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;161:108050. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y, Sun Y, Guo Y, Wang Z, Huang L, Li X. Dual functional cholinesterase and MAO inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: synthesis, pharmacological analysis and molecular modeling of homoisoflavonoid derivatives. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2016;31:389–97. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2015.1024675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomas T. Monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors in the treatment of Alzheimers disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:343–8. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silva MFP, Alves PL, Alponti RF, Silveira PF, Abdalla FMF. Effects of obesity induced by high-calorie diet and its treatment with exenatide on muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampus. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;169:113630. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.113630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shi Q, Liu S, Fonseca VA, Thethi TK, Shi L. Effect of metformin on neurodegenerative disease among elderly adult US veterans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e024954. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumar P, Baquer N. The diabetes drug metformin reverses cognitive impairment and membrane functions in diabetic aging female rat brain: A link with diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2019. 354. 10.1016/j.jns.2019.10.1505.

- 66.Qiu C, Kivipelto M, von Strauss E. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: occurrence, determinants, and strategies toward intervention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:111–28. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/cqiu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:819–28. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stakos DA, Stamatelopoulos K, Bampatsias D, Sachse M, Zormpas E, Vlachogiannis NI, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid-Beta Hypothesis in Cardiovascular Aging and Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:952–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Claassen JAHR. New cardiovascular targets to prevent late onset Alzheimer disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;763:131–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hamidi Shishavan M, Henning RH, van Buiten A, Goris M, Deelman LE, Buikema H. Metformin Improves Endothelial Function and Reduces Blood Pressure in Diabetic Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats Independent from Glycemia Control: Comparison to Vildagliptin. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10975. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11430-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Majithiya JB, Balaraman R. Metformin reduces blood pressure and restores endothelial function in aorta of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Life Sci. 2006;78:2615–24. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.