Abstract

Organohalogens, including monochloroacetic acid (MCA), are abundantly synthesized compounds for various industrial purposes. MCA is widely used as a raw material or as an intermediate compound for the production of pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, plastics, surfactants, shampoos, liquid soaps, and emulsion agents. Nonetheless, widespread and large-scale utilization of organohalogens might negatively impact life quality as these compounds are toxic to organisms and persistently present in the environment. An effort to decrease the effect of MCA pollutant is by performing bioremediation, taking advantage of microorganisms that produce haloacid dehalogenases, a class of enzymes that catalyze the breakage of carbon halogen bonds. In this sense, we have isolated Klebsiella pneumoniae ITB1 that could degrade MCA. The haloacid dehalogenase gene from this bacterium has been successfully cloned into pGEM-T vector and subcloned into pET-30a(+) expression vector to yield pET-hakp1 recombinant clone in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE) host cell. This research aimed to find an optimum condition for producing haloacid dehalogenase from this recombinant clone using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). Among the independent variables studied were the concentration of inducer, incubation temperature after the induction, and incubation period after the induction. We obtained the crude extract of the enzyme as cells' lysate after sonicating the bacterial cells. Haloacid dehalogenase activity against MCA substrate was determined by measuring the amount of chloride ions released into the medium of the enzymatic reaction using the colorimetry method, according to Bergmann and Sanik. The result indicated that the optimum condition for haloacid dehalogenase production by E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 was observed when using 1.8 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside) as the inducer, followed by 4 h incubation with shaking at 37 °C, which was predicted to result in a maximum of 0.48 mM chloride ions from 0.50 mM of MCA substrate. This report provides an insight into applying RSM for optimization of enzyme production from E. coli recombinant clones.

Keywords: RSM, Haloacid dehalogenase, Organohalogen, Monochloroacetic acid

RSM; Haloacid dehalogenase; Organohalogen; Monochloroacetic acid.

1. Introduction

Organohalogens are organic compounds characterized by a covalent bond between carbon and halogen atoms. Despite their natural occurrence, these compounds are abundantly synthesized for various purposes, including pharmaceutics, herbicides, pesticides, and insecticides [1]. Furthermore, the number of organohalogens is uprising rapidly from time to time due to market demand [2, 3]. Nevertheless, widespread utilization of organohalogens creates a negative impact to the environment; thus, these compounds were considered as an important class of environmental pollutants [4], found a lot in soil [5], hydrosphere [6] and commonly observed in drinking water [7] and wastewater [8]. The xenobiotic characteristic of organohalogen is particularly attributed to its stability, persistency, possible carcinogenicity, and the possibility to be transformed into other toxic metabolites [9].

Monochloroacetic acid (MCA) is an example of organohalogens widely used as raw materials or as intermediate compounds in industries. MCA is often utilized to produce betaine surfactant, a material used to produce shampoo, soap, and cleansing agents [10]. MCA is also widely used as building blocks in the production of carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), and 2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid (MCPA) herbicides, for paint and graffiti removal, plastic, and other forms as its amide or ester derivatives [11]. The sodium salt of MCA, namely sodium monochloro acetate (SCMA), is frequently used in the production of a wide variety of compounds such as drugs, dyes, agrochemicals, and thickening agents [12]. It was predicted that production of MCA would increase every year; hence, the amount of MCA pollutant discharged to the environment would also increase.

Organohalogens xenobiotics, including MCA, could be reduced either by a chemical process or by photochemical self-degradation. Unfortunately, both courses are difficult to occur and often require a long period. On the other hand, bioremediation approach by taking advantage of microorganisms that produce dehalogenase would offer a milder and safer technique to overcome this pollution problem [13] by converting these harmful pollutants into non-toxic compounds [14]. Dehalogenase is a group of enzymes that catalyze the carbon–halogen bonds cleavage in organohalogen compounds via several different mechanisms [15, 16]. Haloacid dehalogenase is an example of dehalogenase, classified as a hydrolase and acts on aliphatic acid organohalogens [17]. In addition, various organisms, particularly bacteria and fungi, have been reported to possess the ability to degrade organohalogens [18], including MCA [19].

Previously, we have successfully isolated an MCA-degrading bacterium strain, which was subsequently identified by 16s ribosomal typing as Klebsiella pneumoniae ITB1 [20]. Haloacid dehalogenase gene from this strain, namely the hakp1, has been cloned into pGEM-T vector using E. coli TOP10 host and further sequenced [20]. This gene was subsequently subcloned into pET-30a(+) expression vector using E. coli BL21 (DE3) host, and again sequenced for confirmation [21]. The hakp1 gene sequence has been submitted to GenBank with accession number AQT27349.

In pET expression system, the gene was cloned under the T7 promoter, whose expression was depended on the availability of T7 RNA polymerase produced by E. coli BL 21 (DE3) host. The synthesis of T7 RNA polymerase in the host cells was regulated by the lacUV5 promoter, which would be activated by IPTG induction [22]. Upon induction, all cell’s resources would be utilized for expressing the target gene, and therefore the desired target protein would be abundantly produced after a few hours of induction [23]. However, such overexpression might generally accumulate the produced protein in the form of inclusion bodies, insoluble protein aggregates of enzyme that were usually inactive. Therefore, researchers have attempted different approaches to prevent the formation of the inclusion bodies, such as engineering the host cells [24], increasing the intracellular concentration of chaperon molecules [25], performing induction in either mid-exponential phase or final exponential phase [26], reducing the inducer concentration [27], and lowering the induction temperature [28].

In this research, we aimed to find an optimum condition of hakp1 gene expression in recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 clone using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). RSM is a statistical method frequently used in determining an optimum experimental condition with a minimum repetition of laboratory works [29]. This method has been widely utilized in optimizing recombinant protein production [30, 31]. RSM-guided experiments gained success in the production of recombinant protein because they provide information on variable interactions that might escape the one-factor-at-a-time methods [32]. In this study, an optimum production of haloacid dehalogenase from recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 was determined by observing the influence of three variables, which are the inducer concentration, induction incubation temperature, and duration of induction incubation. Bacterial cells from the culture were harvested and subsequently lysed to result in a crude enzyme, which was then subjected to haloacid dehalogenase activity test using MCA as the substrate. The activity of haloacid dehalogenase was represented by the concentration of chloride ions released into the medium of the enzymatic reaction.

2. Experimental

2.1. Source and regeneration of recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1

The E. coli BL21 (DE3) carrying the recombinant pET-hakp1, named E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1, was obtained from our previous research [21]. The glycerol stock culture of this recombinant clone was regenerated by streaking the culture on a solid Luria Bertani (LB) agar medium containing 50 μg/mL of kanamycin to obtain a single colony. The pET-hakp1 recombinant plasmid was subsequently isolated from this single colony culture by the standard lysis alkali method [33]. The obtained recombinant plasmid was analyzed by gel electrophoresis, followed by restriction analysis for confirmation. The production of haloacid dehalogenase from the recombinant clone was further confirmed by SDS PAGE, which also examined the importance of IPTG induction and enzyme bifurcation into soluble or non-soluble entities. Evidence of haloacid dehalogenase activity in the cells' lysate was verified by zymogram analysis using MCA as a substrate. The confirmed E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 recombinant clone was then utilized in all further experiments.

2.2. Culturing E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 for haloacid dehalogenase production

The confirmed recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 was employed in the production of haloacid dehalogenase. A single colony of this recombinant clone was inoculated into 5 mL of LB liquid medium containing 50 μg/mL of kanamycin and incubated overnight at 37 with shaking. To obtain a more concentrated starter culture, cells from this overnight culture were harvested through centrifugation and resuspended again into 1 mL of LB fresh medium. Expression of hakp1 gene to produce haloacid dehalogenase was then performed as follows.

Expression was carried out in 20 mL of LB broth liquid medium containing 50 μg/mL of kanamycin, which was inoculated with 0.2 mL of fresh starter culture and incubated at 37 with shaking for about 2 h. The cell density of the culture was monitored by measuring the culture’s optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Once the OD600 reached 0.6–0.8, the IPTG inducer was added to the desired concentration (as stated in the experimental design), and incubation was continued at the desired temperature for a certain shaking period (as stated in the experimental design). The bacterial cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 4 , resuspended in 50 mM of Tris-acetate buffer pH 7.5, and then lysed by intermittent ultrasonication for 10 min with 50% amplifier level at 4 , 30 s on and 30 s off. Finally, the lysate (the crude enzyme extract) was separated from the cells' debris by centrifugation at 4 , which was subsequently used to perform the enzymatic reaction of MCA degradation.

2.3. Experimental design for optimization of haloacid dehalogenase production

The optimum condition of hakp1 gene expression in the recombinant E. coli Bl21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 was studied by applying the Response Surface Methodology (RSM). First, a set of experimental conditions was determined by central composite designed (CCD), varying three factors in haloacid dehalogenase gene expression to produce the enzyme, namely the inducer (IPTG) concentration, induction incubation temperature, and period of induction incubation. Next, the setup conditions were determined using a range of variables as depicted in Table 1 (Set 1) and the predicted responses were analyzed using Minitab Statistical Software 18 to design 20 experimental runs with one replicate at the central point as shown in Table 2. However, as the laboratory experiments using Set 1 conditions could not provide the expected result from RSM analysis, Set 2 conditions were then designed with a narrower range of variables (as shown in Table 1). The respective responses were statistically predicted (shown in Table 3).

Table 1.

Range of the three variables used in the optimization of haloacid dehalogenase production from E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1.

| Variable | Range for optimization |

|

|---|---|---|

| Set 1 | Set 2 | |

| IPTG concentration | 0.5 mM–1.5 mM | 1.3 mM–2.3 mM |

| Induction temperature | 20 °C–45 °C | 30 °C–44 °C |

| Induction period | 2 h–6 h | 3 h–5 h |

Table 2.

Observed chloride ions concentration from RSM designed experimental conditions using CCD approach.

| No. | T (°C) | t (hours) | [IPTG] (mM) | A450 | [Cl─] (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33 | 4 | 1 | 0.237 | 0.37 |

| 2 | 25 | 5 | 1.3 | 0.215 | 0.331 |

| 3 | 45 | 4 | 1 | 0.218 | 0.337 |

| 4 | 33 | 6 | 1 | 0.197 | 0.3 |

| 5 | 33 | 4 | 1 | 0.234 | 0.365 |

| 6 | 25 | 3 | 1.3 | 0.204 | 0.312 |

| 7 | 25 | 5 | 0.7 | 0.205 | 0.314 |

| 8 | 25 | 3 | 0.7 | 0.201 | 0.307 |

| 9 | 20 | 4 | 1 | 0.179 | 0.268 |

| 10 | 40 | 5 | 1.3 | 0.242 | 0.379 |

| 11 | 33 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.231 | 0.359 |

| 12 | 40 | 5 | 0.7 | 0.255 | 0.401 |

| 13 | 33 | 4 | 1 | 0.239 | 0.373 |

| 14 | 40 | 3 | 0.7 | 0.204 | 0.312 |

| 15 | 33 | 2 | 1 | 0.164 | 0.242 |

| 16 | 33 | 4 | 1.5 | 0.24 | 0.375 |

| 17 | 33 | 4 | 1 | 0.239 | 0.373 |

| 18 | 33 | 4 | 1 | 0.218 | 0.337 |

| 19 | 40 | 3 | 1.3 | 0.25 | 0.393 |

| 20 | 33 | 4 | 1 | 0.237 | 0.37 |

Table 3.

The reconstructed induction conditions and computational prediction of the released chloride ions concentration.

| No. | T (°C) | t (hours) | [IPTG] (mM) | A450 | [Cl─] (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33 | 3 | 2.1 | 0.105 | 0.139 |

| 2 | 37 | 4 | 1.8 | 0.281 | 0.447 |

| 3 | 37 | 3 | 1.8 | 0.212 | 0.326 |

| 4 | 37 | 4 | 1.3 | 0.249 | 0.391 |

| 5 | 37 | 4 | 1.8 | 0.31 | 0.498 |

| 6 | 37 | 4 | 2.3 | 0.114 | 0.154 |

| 7 | 33 | 5 | 2.1 | 0.126 | 0.176 |

| 8 | 33 | 5 | 1.5 | 0.121 | 0.167 |

| 9 | 41 | 5 | 1.5 | 0.142 | 0.204 |

| 10 | 33 | 3 | 1.5 | 0.142 | 0.204 |

| 11 | 37 | 4 | 1.8 | 0.29 | 0.463 |

| 12 | 44 | 4 | 1.8 | 0.146 | 0.211 |

| 13 | 41 | 5 | 2.1 | 0.145 | 0.209 |

| 14 | 30 | 4 | 1.8 | 0.132 | 0.186 |

| 15 | 41 | 3 | 1.5 | 0.158 | 0.232 |

| 16 | 37 | 4 | 1.8 | 0.251 | 0.394 |

| 17 | 37 | 4 | 1.8 | 0.298 | 0.477 |

| 18 | 37 | 4 | 1.8 | 0.31 | 0.498 |

| 19 | 41 | 3 | 2.1 | 0.14 | 0.2 |

| 20 | 37 | 5 | 1.8 | 0.287 | 0.458 |

2.4. Enzymatic MCA degradation and chloride ions determination

The ability of the crude enzyme extract to catalyze MCA degradation was investigated by performing an enzymatic reaction in 1 mL solution. A 50 μL crude enzyme extract was added into 850 μL glycine-NaOH buffer pH 9, and 100 μL of 5 mM MCA was added. The mixture was mixed well by inverting the tube and then incubated at 37 in a waterbath for 10 min. A negative control experiment was carried out under an identical condition but in the absence of enzyme extract. The reaction was stopped by placing the tube on ice for about 5 min and the amount of chloride ions released was colorimetrically quantified according to Bergmann and Sanik method [34] as follows.

Into this 1 mL of enzymatic reaction mixture, 100 μL of 0.1% (w/v) Hg(SCN)2 was added. The mixture was mixed well by inverting the tube several times and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Then, 100 μL of 0.25 M Fe(NH4) (SO4)2 in 9 M HNO3 was added, mixed well by inverting the tube, followed by further incubation for 5 min at room temperature. The mixture was centrifuged to separate any formed precipitate and the absorbance of the supernatant, which contained Fe(SCN)2+, was measured at 460 nm. The chloride ions resulted from MCA degradation was determined using NaCl standard curve.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Confirmation of E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 recombinant clone

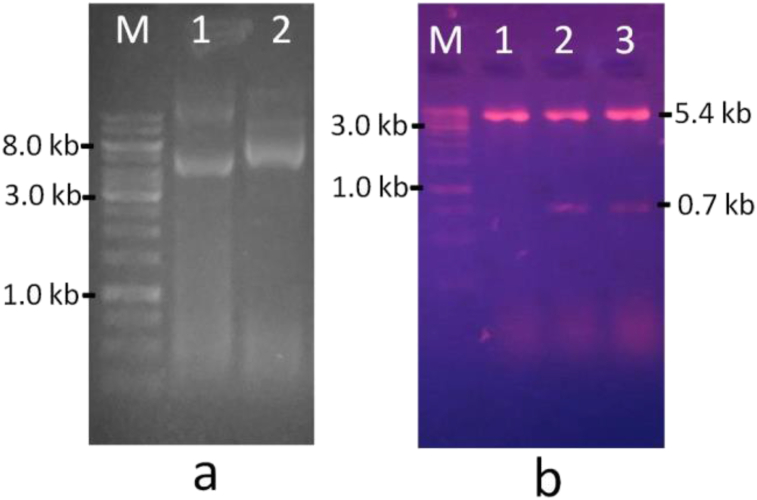

In this study, confirmation of E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 recombinant clone was carried out prior to its utilization in all further experiments. The plasmid was isolated from a fresh culture, originated from a single colony, in liquid LB selective medium containing 50 μg/mL of kanamycin. The sizes of the isolated recombinant plasmid (pET-hakp1) and the resulted fragment from restriction digestion were analyzed through agarose gel electrophoresis. The observed electropherograms were presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Electropherograms for size determination and restriction analysis of the recombinant plasmid. (a) undigested pET-30a(+) and pET-hakp1, (b) pET-30a(+) and pET-hakp1 digested with EcoRI and HindIII. M = 1 kb DNA ladder, a1 = undigested pET-30a(+) plasmid, a2 = undigested pET-hakp1recombinat plasmid, b1 = linearised pET-30a(+) with EcoRI, b2 and b3 = double digested pET-hakp1 with EcoRI and HindIII.

The pET-30a(+) was the expression vector used in cloning the hakp1 gene from K. pneumonia ITB1. The pET-hakp1 recombinant plasmid (Figure 1a line 2) showed a lower mobility in the gel compared to pET-30a(+) vector (Figure 1a line 1), indicating that the size of pET-hakp1 was larger compared to its vector. This fact demonstrated the presence of gene insert in pET-hakp1 recombinant plasmid, which was then confirmed by restriction analysis, as shown in Figure 1b and Figure S1. Restriction enzymes EcoRI and HindIII were used in this analysis because these two enzymes were utilized in hakp1 direct sub-cloning, moving the hakp1 gene from pGEM-T vector to pET-30a(+) expression vector. The double digested pET-hakp1 with EcoRI and HindIII (Figure 1b line 2 and 3) resulted in two fragments of about 5.4 kb and 0.7 kb. The 5.4 kb fragment was identical to the size of the linearized pET-30a(+) vector with EcoRI (Figure 1b line 1). Hence, it could be confirmed that the 0.7 kb insert was present in pET-hakp1. This insert size is the same as the size of hakp1 gene from K. pneumonia ITB1 [21]. All further experiments were then performed using this confirmed E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 recombinant clone.

The importance of IPTG induction and gene product availability in the recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 were both visualized using SDS PAGE analyses, resulting in a gel depicted in Figure 2. Here, the protein was examined within the cell that was cultured either with or without IPTG induction. The harvested cells were ruptured by sonication and the cell debris was further separated by centrifugation. It could be seen that a 28 kDa protein band, which is correlated to haloacid dehalogenase, was observed in the cell only after IPTG introduction (Figure 2 line 1–4) and was not present for the cell with no IPTG addition (Figure 2 line 0), indicating that the gene was only expressed in the presence of IPTG. Furthermore, this 28 kDa protein was not observed in the growth medium (Figure 2 line Med), suggesting that Hakp1 is an intracellular enzyme. Furthermore, this protein was observed both in cell debris (Figure 2 line Deb) and in cells' lysate (Figure 2 line Lys) hinting at no significant bifurcation of the protein into soluble and non-soluble entities inside the cells. Haloacid dehalogenase in the cell debris commonly exists as inclusion bodies and inactive [35].

Figure 2.

SDS PAGE of protein content from the recombinant clone. M = molecular weight protein marker; 0 = cells' lysate with no IPTG induction; 1–4 = cells' lysate after 1–4 h IPTG induction, respectively; Deb, Med, and Lys are cells debris, medium, and cells lysate after 2 h IPTG induction, respectively.

Further analysis on cells' lysate was presented in Figure 3a and Figure S2 confirmed that the 28 kDa protein was present in the lysate only after IPTG induction (Figure 3a line 1 and 2) and was absent if no IPTG was added (Figure 3a line 0). The haloacid dehalogenase activity of this 28 kDa protein was demonstrated by the appearance of white precipitate on zymogram (Figure 3b and Figure S3), which was obtained using MCA substrate and stained with AgNO3. Therefore, our experiment was focused on the lysate from the recombinant cells cultured in various conditions as designed by RSM.

Figure 3.

(a) SDS PAGE of recombinant cells lysate and (b) zymogram stained with AgNO3 from native PAGE using MCA substrate. M = molecular weight protein marker; 1a and 2a = cells lysate after 1 and 2 h IPTG induction, respectively; 0a = cells lysate with no IPTG induction; 1b and 2b = cells lysate after 2 h IPTG induction, respectively.

3.2. Experimental design and chloride ion determination

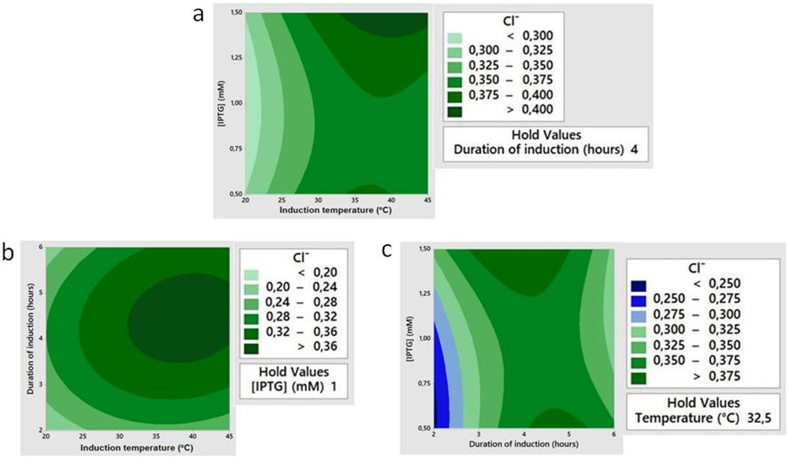

A set of experimental conditions had been determined through RSM, applying central composite designed (CCD) with one replicate at the central point that follows a full factorial design of Plackett-Burman design. The first set of experimental conditions with three studied independent variables, which were induction temperature, duration of induction, and IPTG concentration, was presented in Table 1 Set 1 and further detailed in Table 2. The recombinant E. coli LB21 (DE30/pET-hakp1) was cultured (as stated in materials and methods) and induced by ITPG with these conditions. The crude enzyme from each culture was then obtained through sonication and used to perform an enzymatic reaction in 0.5 mM of MCA. The responses were represented as chloride ion concentrations released in the enzymatic reaction, which were quantified according to Bergmann and Sanik method [34]. The result of 20 experimental runs involving 23 variations was presented in Table 2 and the respective two-dimensional contour plots were presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Contour plots of chloride ions concentration (Cl─) as a function of (a) induction temperature and IPTG concentration, (b) induction temperature and duration of induction, and (c) duration of induction and IPTG concentration. Dark green circle in the plot shows optimum zone of Cl─ concentration.

Among the three contour maps presented in Figure 4, only one contour map (Figure 4b) showed a clear location of the optimum zone (shown as dark green circle at the center point), which was the contour flow effect of induction temperature and duration of induction incubation on Cl− concentration produced by haloacid dehalogenase activity. The optimum condition with 1 mM IPTG was reached when the induction temperature is ∼37 with the induction duration of 4 h. However, the optimum zone to determine the IPTG concentration could not be obtained yet, though it could be predicted from Figure 4a that the IPTG concentration might be above 1.5 mM.

Following this result, the experimental design was reconstructed by shifting the optimum range of variables as shown in Table 1 Set 2 and further detailed in Table 3. The range of induction temperature and induction time is narrowed according to the obtained optimum zone of Set 1, and inducer concentrations range was increased to areas above 1.5 mM. Applying the same RSM procedure with CCD design, 20 new conditions were established and presented in Table 3. In this report, the produced chloride ions were predicted by trial and error following the trend of Figure 4a and 4c. The results were listed in Table 3 and the respective predicted contour plots were presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Contour plots of predicted chloride ions concentration (Cl─) as a function of (a) induction temperature and IPTG concentration, (b) induction temperature and duration of induction, and (c) duration of induction and IPTG concentration. Dark green circle in the center of the plot shows optimum zone of Cl─ concentration.

As shown in Figure 5, the optimum zone of haloacid dehalogenase appeared in all three contour plots, indicated by dark green full circles in the center of the maps. This result was consistent with our previous data from Set 1 experimental design, except for the optimum IPTG concentration observed at 1.8 mM. Therefore, the suggested optimum condition for haloacid dehalogenase production by the recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 was achieved by inducing the culture with 1.8 mM IPTG followed by incubation at 37 °C for 4 h. This IPTG concentration was in the range of the reported effective inducer concentration for recombinant gene expression in pET system, which was stated to be 0.1 mM–3.0 mM and highly dependent on media composition [36]. Moreover, induction conditions must be adopted on different cultivation temperature, though lower inducer concentration was advantageous, as this would not put such a high metabolic burden [37]. Nevertheless, the strength of induction is an essential parameter for optimizing recombinant protein expression [38].

The predicted chloride ions concentrations presented in Table 3 were dependent upon three independent variables, i.e., inducer concentration, duration of induction, and induction temperature. Based on the CCD approach, these variables' relationship was established by the following second-order polynomial equation that includes linear, quadratic, and variables interactions.

| (1) |

where Y is the response of independent variable, the chloride ion concentration (mM) as a result of haloacid dehalogenase activity on MCA substrate. The independent variables are A = induction temperature (), B = duration of induction (hours), and C = IPTG concentration (mM). This second-order polynomial equation can be used to determine response estimations for specific levels of each independent variable. A large positive coefficient of an independent variable demonstrated a significant positive effect on the response. On the other hand, the negative number of coefficients exhibited an inverse correlation between the response and the independent variable, showing that a negative value leads to the acquisition of the response with the highest value. This polynomial equation fit the optimization curve presented in Figure 6, which showed more precise values of the independent variables with high desirable score of response (d = 0.9237).

Figure 6.

Optimization curve of induction temperature (°C), duration of induction (hours), and IPTG concentration (mM) on the production of haloacid dehalogenase by E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 represented by chloride ions concentrations in the reaction mixture.

The optimum induction condition for E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 to produce haloacid dehalogenase was upon utilizing 1.7444 mM IPTG inducer, followed by incubation at 37.2121 for 4.0909 h. This result is in good agreement with the data from the previous contour plot. Influence of duration incubation after IPTG induction on enzyme production was also shown in Figure 2. Furthermore, the observed optimization curve indicated that the quadratic model was suitable for obtaining the optimum induction condition. Similar results had been reported on inducer optimization to produce specific recombinant protein in E. coli BL2 (DE3) [39].

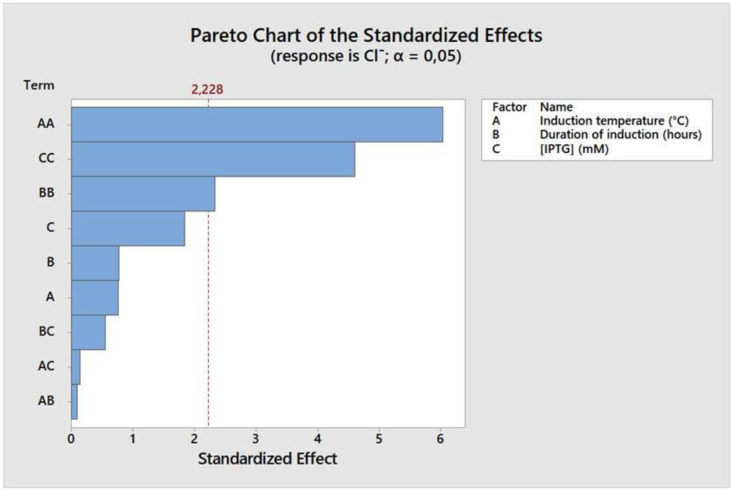

3.3. Contribution and correlation significance of each independent variable

In RSM, the contribution and correlation of each independent variable to the response could be analyzed using a Pareto chart, which could be constructed from the obtained regression polynomial equation. In this study, the constructed Pareto chart (Figure 7) illustrates the standardized effect of the three studied independent variables as well as the relationship and interaction between these variables. The standardized effect is the minimum value that shows the influence of each variable. The size of the effect corresponds to the length of the bar. Independent variables are predicted to have a statistically significant effect and play an important role in the response if the bar of the standardized effect exceeds the minimum limit, in this case is 2.228 (shown as a cross-perpendicular red dotted line) [40].

Figure 7.

Pareto chart that illustrates the three independent variables influence toward the response, which was represented as the chloride ions concentration released on the enzymatic reaction on MCA degradation catalyzed by the produced haloacid dehalogenase. Response significancy was presented at α = 0.5. A = induction temperature (°C), B = duration of induction (hours), and C = IPTG (inducer) concentration (mM).

The Pareto chart (Figure 7) showed that the three independent variables (induction temperature, duration of induction, and inducer concentration) significantly contribute to the observed chloride ions concentration in its quadratic model. On the other hand, the interaction of these three variables to the response was not observed. Induction temperature was apparent to be the most influential factor, followed by IPTG concentration, and then the duration of induction. This result was in good agreement with previous report, which stated that the temperature of induction was critical at a particular inducer concentration, whereas induction time was less relevant when the correct inducer concentration was chosen [37].

ANOVA was finally performed to examine variables' significance to the response as well as to validate the observed model. The obtained result gave a correlation coefficient (R2) and p-value of 85.59% and 0.003 (<0.05), respectively, which indicated that the model was significantly fit to the observed response. Further ANOVA was carried out with this Minitab Statistical Software 18 to obtain the coded coefficient and significant level (p-value) of each independent variable. The results are presented in Table 4. The coded coefficient describes the size effect to response changes, where the sign indicates the direction of changes. A negative sign predicts an increase of variable would decrease the response.

Table 4.

Coded coefficient and significance level (p-value) of the model and independent variables on haloacid dehalogenase production by E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1.

| Terms and Variables | Coded Coefficient | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Model | - | 0.003 |

| Linear | - | 0.265 |

| Induction temperature(°C) | 0.0147 | 0.458 |

| Duration of induction (hours) | 0.0148 | 0.456 |

| IPTG concentration (mM) | -0.0351 | 0.095 |

| Square | - | 0.000 |

| Induction temperature (°C)∗Induction temperature (°C) | -0.1116 | 0.000 |

| Duration of induction (hours)∗Duration of induction (hours) | -0.0432 | 0.042 |

| IPTG concentration (mM)∗IPTG concentration (mM) | -0.0853 | 0.001 |

| Interaction | - | 0.950 |

| Induction temperature (°C)∗Duration of induction (hours) | -0.0024 | 0.925 |

| Induction temperature (°C)∗IPTG concentration (mM) | 0.0037 | 0.884 |

| Duration of induction (hours)∗IPTG concentration (mM) | 0.0138 | 0.591 |

As shown in Table 4, all three studied variables in the quadratic model possessed p-values below 0.05, indicating that these three variables significantly influence the haloacid dehalogenase production. Comparison of these p-values, as well as the respective coded coefficients, clearly indicated that the induction temperature and IPTG concentration are more significant compared to the duration of induction. A steeper curve of these two variables shown in Figure 6 also supports this analysis. This result is in good agreement with those obtained from the Pareto chart. Moreover, all interaction types between variables possessing high p-values suggested that interaction between variables was absent.

4. Conclusions

We have demonstrated the use of Response Surface Methodology (RSM) in determining the optimum condition for the production of haloacid dehalogenase from recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 clones. Prior to analyses with RSM, we first confirmed that the recombinant clones indeed contained the haloacid dehalogenase encoding gene, namely hakp1, through plasmid isolation and restriction digestion, which was analyzed using agarose gel electrophoresis. Enzyme bifurcation into soluble and non-soluble entities, the importance of IPTG induction, the influence of duration incubation, and proof of haloacid dehalogenase activity were evaluated and confirmed using SDS PAGE and zymogram analyses. The expressed crude enzyme obtained as cells lysate after sonicating the bacterial cells was employed to degrade MCA, resulting in the release of chloride ions into the medium of enzymatic reaction. The chloride ions were quantified using UV-Vis spectrophotometry according to Bergmann and Sanik method. RSM analyses indicated that the optimum condition for haloacid dehalogenase production by E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pET-hakp1 was achieved at 1.8 mM IPTG as the inducer, followed by 4 h incubation with shaking at 37 , which was predicted to result in a maximum of 0.48 mM chloride ions from 0.50 mM of MCA substrate. Our study showed that RSM is an efficient approach to optimize the condition of enzyme production from E. coli recombinant clones.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Enny Ratnaningsih: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Sarah I. Sukandar: Performed the experiments.

Rindia M. Putri; Grandprix T. M. Kadja: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

I Gede Wenten: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ridani Rino Anggoro for providing SDS-PAGE and zymogram results.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Wong W.Y., Huyop F. Molecular identification and characterization of dalapon 2,2-dichloropropionate (2,2-DCP) degrading bacteria from a rubber estate agricultural area. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2012;6(7):1520–1526. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zakary S., Oyewusi H.A., Huyop F. Dehalogenases for pollutant degradation: a mini review. J. Trop. Life Sci. 2021;11(1):17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adamu A., Wahab R.A., Aliyu F., Aminu A.H., Hamza M.M., Huyop F. Haloacid dehalogenases of rhizobium sp. and related enzymes: catalytic properties and mechanistic analysis. Process Biochem. 2020;92:437–446. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohamed M.F., Kang D., Aneya V.P. Volatile organic compounds in some urban locations in United States. Chemosphere. June 2002;47(8):863–882. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(02)00107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diez A., Alvarez M.J., Prieto M.I., Bautista J.M., Garrido-Pertierra A. Monochloroacetate dehalogenase activities of bacterial strains isolated from soil. Can. J. Microbiol. 1995;41(8):730–739. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Römpp A., Klemm O., Fricke W., Frank H. Haloacetates in fog and rain. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001;35(7):1294–1298. doi: 10.1021/es0012220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang P., Lapara T.M., Goslan E.H., Xie Y., Parsons S.A., Hozalski R.M. Biodegradation of haloacetic acids by bacterial isolates and enrichment cultures from drinking water systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43(9):3169–3175. doi: 10.1021/es802990e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Islam N.F., Sarma H., Prasad M.N. Disinfection by-Products in Drinking Water. Elsevier; 2020. Emerging disinfection by-products in water: novel biofiltration techniques; pp. 109–135. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huyop F.Z., Yusn T.Y., Ismail M., Ab Wahab R., Cooper R.A. Overexpression and Characterization of non-stereospecific haloacid dehalogenase E (DehE) of Rhizobium sp., Asia Pac. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;12(1-2):15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghassempour A., Chalavi S., Abdollahpour A., Mirkhani S.A. Determination of mono- and dichloroacetic acids in betaine media by liquid chromatography. Talanta. 2006;68(4):1396–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Commision . Bilthoven; The Netherlands: 2005. Summary Risk Assessment Report: Monochloroacetic Acid. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sunray International . 2021. Product, Sodium Monochloro Acetate (SCMA) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimoto H., Suye S., Makashima H., Aral J., Yamaguchi S., Fujii Y., Yoshioka T., Taketo A. Cloning of a novel dehalogenase from environmental DNA. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010;74(6):1290–1292. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maier R.M., Pepper I.L., Gerba C.P. Introduction to environmental microbiology. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;3–7 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slater J.H., Bull A.T., Hardman D.J. Microbial dehalogenation of halogenated alkanoicacids, alcohols and alkanes. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 1997;38:133–176. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y., Feng Y., Cao X., Liu Y., Xue S. Insights into the molecular mechanism of dehalogenation catalyzed by D-2-haloacid dehalogenase from crystal structures. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-19050-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardman D.J., Slater J.H. Dehalogenases in soil bacteria. Microbiology. 1981;123(1):117–128. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ang T.-F., Maiangwa J., Salleh A.B., Normi Y.M., Leow T.C. Dehalogenases: from improved performance to potential microbial dehalogenation applications. Molecules. 2018;23(5):1100. doi: 10.3390/molecules23051100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alomar D., Hamid A.A.A., Khosrowabadi E., Gicana R.G., Lamis R.J., Huyop F., Hamid T.H.T.A. Molecular characterization of monochloroacetate degrading arthrobacter sp. strain D2 isolated from university Teknologi Malaysia agricultural area. Bioremediat J. 2014;18(1):12–19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tahya C.Y., Ratnaningsih E. Cloning and sequencing of haloacid dehalogenase gene from Klebsiella pneumoniae ITB1. Procedia Chem. 2015;16:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anggoro R.R., Ratnaningsih E. Expression of haloacid dehalogenase gene and its molecular protein characterization from Klebsiella pneumoniae ITB1. Indones. J. Biotechnol. 2017;22(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubendorf J.W., Studier F.W. Controlling basal expression in an inducible T7 expression system by blocking the target T7 promoter with lac repressor. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;219(1):45–59. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90856-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mierendorf R.C., Morris B.B., Hammer B., Novy R.E. Vol. 13. Humana Press; Totowa NJ: 1998. Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins Using pET System, Methods Mol. Med. pp. 257–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosano G.L., Morales E.S., Ceccarelli E.A. New tools for recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli: a 5-year update. Protein Sci. 2019;28(8):1412–1422. doi: 10.1002/pro.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mogk A., Mayer M.P., Deuerling E. ChemInform abstract: mechanisms of protein folding: molecular chaperones and their application in biotechnology. ChemInform. 2010;33(46):272. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020902)3:9<807::AID-CBIC807>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galloway C.A., Sowden M.P., Smith H.C. Increasing the yield of soluble recombinant protein expressed in E. coli by induction during late log phase. Biotechniques. 2003;34(3):524–530. doi: 10.2144/03343st04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winograd E., Pulido M.A., Wasserman M. Production of DNA-recombinant polypeptides by tac-inducible vectors using micromolar concentrations of IPTG. Biotechniques. 1993;14(6):886–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schein C.H., Noteborn M.H.M. formation of soluble recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli is favored by lower growth temperature. Nat. Biotechnol. 1988;6(3):291–294. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Said K.A.M., Amin M.A.M. Overview on the response Surface methodology (RSM) in extraction process. J. Appl. Sci. Process Eng. 2015;2(1):279–287. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Behravan A., Hashemi A. Statistical optimization of culture conditions for expression of recombinant humanized anti-EpCAM single-chain antibody using response Surface methodology. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2021;16(2):153–164. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.310522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pal D., Patel G., Dobariya P., Nile S.H., Pande A.H., Banerjee U.C. Optimization of medium composition to increase the expression of recombinant human interferon-ꞵ using the plackett-burman and central composite design in E. coli SE1. Biotech. 2021;11(5):226. doi: 10.1007/s13205-021-02772-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papaneophyton C.P., Kontopidis G. Statistical approaches to maximize recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: a general review. Protein Expr. Purif. 2014;94:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J., Russell D.W. In: ed. 3, editor. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 2001. (Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergmann J.G., Sanik J. Determination of trace amounts of chlorine in Naphtha. Anal. Chem. 1957;29(2):241–243. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratnaningsih E., Sunaryo S.N., Idris I., Putri R.M. Recombinant production and one-pot purification for enhancing activity of haloacid dehalogenase from Bacillus cereus IndB1. Reaktor, (Chem. Eng. J.) 2021;21(2):56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ashayeri-Panah M., Eftekhar F., Kazemi B., Joseph J. Cloning,Optimization of induction Conditions and Purification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv1733c protein Expressed in Escherichia coli, Iran. J. Microbiol. 2017;9(2):64–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muhlmann M., Forsten E., Noack S., Buchs J. Optimizing recombinant protein expression via automated induction profiling in microtiter plates at different temperatures. Microb. Cell Factories. 2017;16:220. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0832-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J., Xin Y., Cao X., Xue S., Zhang W. Purification and Characterization of 2-haloacid Dehalogenase from marine bacterium Paracoccus sp. DEH99, Isolated from marine sponge Hymeniacidon perlevis. J. Ocean Univ. China. 2014;13(1):91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kusuma S.A.F., Parwati I., Rostinawati T., Yusuf M., Fadhollah M., Ahyudanari R.R., Rukayadi Y., Subroto T. Optimization of culture conditions for Mpt64 synthetic gene expression in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) using Surface response methodology. Heliyon. 2019;5(11) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antony J. In: ed. 2, editor. Elsevier; 2014. Fundamentals of design of experiments; pp. 7–17. (Design of Experiments for Engineers and Scientists). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.