Abstract

Aim

This study explored the experiences of nursing students with respect to learning processes and professional development during internships with COVID-19 patients to build a novel theoretical model.

Background

The COVID-19 outbreak had a profound impact on the worldwide learning system and it interrupted the internship experiences of nursing students. After the second wave of COVID-19, to balance academic activities with COVID-19 containment, some Italian universities allowed nursing students’ internships in COVID-19 units. This new experience may have influenced nursing students’ learning processes and professional development, but this is yet to be investigated.

Design

A qualitative study using a constructivist grounded theory (CGT) approach.

Methods

Nursing students were recruited from two hospitals in northern Italy between January and April 2021. Data are gathered from interviews and a simultaneous comparative analysis were conducted to identify categories and codes, according to Charmaz’s (2006) theory.

Results

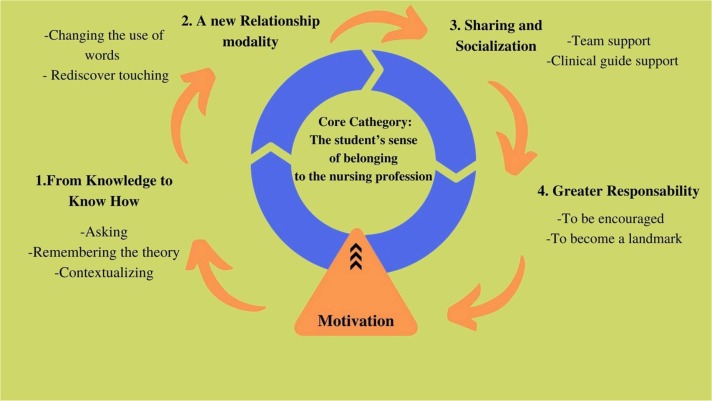

The sample consisted of 28 students. The results suggested the core category, that is the ‘Students’ sense of belonging to the nursing profession’ and four main categories: (1) From knowledge to know-how, (2) A new relationship modality, (3) Sharing and socialisation and (4) Responsibilization. Finally, a premise and a corollary, respectively (5) Motivation and the (6) Circularity of the process, were identified.

Conclusion

Our study proposed a new theory of nursing students’ learning processes in clinical contexts during internships with COVID-19 patients. Despite significant difficulties, the nursing students developed a unique learning process characterised by motivation. Therefore, our study provided insight into the learning process during a pandemic and investigated the support needed for nursing students to continue their internships.

Keywords: Constructivist grounded theory, COVID-19 outbreak, Learning process, Nursing students, Qualitative study

1. Introduction

On the 11th March 2020, after assessing the severity levels and spread of COVID-19, the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic (Atzrodt et al., 2020), catapulting all worldwide population into an unnatural reality, characterised by sudden upheavals of daily life where families, students and citizens felt alone and lost (Bobbo and Moretto, 2020). The entire, including university students, world was burdened (Xiong et al., 2020). In particular, quarantine or isolation rules were imposed to contain the spread of the virus, which resulted in the closing of schools. This meant that all on-site university services were stopped in-person student activities were interrupted. As such, the educational system was revolutionised to address this new challenge: online learning took over and replaced traditional means of communicating (Moreno et al., 2021).

The most consequence of COVID-19 outbreak impact on nursing academies is the interruption of the internship experiences of nursing students. After the second wave of COVID-19, to balance academic activities with COVID-19 containment, some Italian universities allowed nursing students’ internships in COVID-19 units. This new experience may have influenced nursing students’ learning processes and professional development, but this is yet to be investigated.

1.1. Background

In many countries, the abrupt interruption of all in-person educational activities had significant consequences for nursing students, as it essentially removed practical training, which, forced nursing educators and clinical preceptors to reorganise their internship activities (Bobbo and Moretto, 2020, Tolyat, 2022). In particular, nursing students were excluded from clinics, facilitating the online learning, which limited the great opportunity that practical learning would offer to future nurses (Baldini and De Luca, 2021, Park and Seo, 2022).

Nursing education involves theoretical and practical training processes, but practical learning is essential to increasing the knowledge of clinical setting practices (Fadhliah Mahmud et al., 2014). In essence, internships are learning opportunities where students can apply their theoretical knowledge to a clinical context to develop, test and refine their practical knowledge (Tolyat, 2022). Therefore, the profound upheaval in the way of providing practical training, required to protect safety and health due to the advent of the pandemic, especially during first and second COVID-19 waves, could have influenced the acquisition of skills and knowledge of future nurses and their learning process and personal development.

The importance of practical experience for training areas such as nursing has triggered serious debate among politicians and decision-makers with respect to balancing the risks and benefits of resuming practice activities (Intinarelli et al., 2021). In this regard, starting from October 2020 during the second wave of COVID-19, different approaches to educational activities were applied worldwide that balanced the risks and benefits of resuming practice activities. For example, to address the necessity of nurse recruitment in the context of the pandemic, some Spanish universities recruited nursing students attending the last year of bachelor’s degree course to employ them in clinical realities as a workforce (Casafont et al., 2021). This strategy was implemented to address the overcrowded healthcare system; however, it had some problems, e.g. only 3.4% of all students (n = 502) felt prepared to manage the COVID-19 context (Hernández-Martínez et al., 2021).

Despite this, nursing students’ attending the final year of the bachelor’s degree course were the one who attended the training with simulation, with the mechanical ventilation, as the fundamental aspect to deal with COVID-19 patients. This allowed healthcare systems to fill the nurses lacking, which was filled with nursing student’s recruitment, not only on voluntary basis but also with a symbolic pay (Hernández-Martínez et al., 2021). Additionally, to support the stressed healthcare services, other countries (such as Australia and the UK) recruited nursing students to take care of COVID-19 patients with the support of qualified nurses. So, Intinarelli et al. (2021) demonstrated that nurse practitioner students are an essential emergency workforce in the face of a pandemic, as engaged as part of the COVID-19 response. In their study, the authors reported the swift creation of academic medical centre and community health deployments to minimise the public health impacts of COVID-19, while also providing an opportunity for students to progress and successfully graduate on time in their programmes (Intinarelli et al., 2021).

In Italy, some universities allowed internship units with COVID-19 patients, as they recognised the strategic role of internships in the development of nursing skills and competencies (Barisone et al., 2022). Some of these students experienced stress and anxiety due to insecurity about their own expertise; some felt guilty about the possibility of being a burden on professional nurses (García-Martín et al., 2021). Despite this, nursing students wanted to contribute their skills to the global health emergency, especially in Spain and, as such, some were selected on a voluntary basis to complete their internships (Hernández-Martínez et al., 2021).

1.2. Aim of the study

Therefore, in consideration of the continuous COVID-19-related changes to nursing internships (Bobbo and Moretto, 2020), it is possible to suppose a deep repercussion on the process of learning and professional development of nursing students, but to date it is not investigated yet. Knowing the changes in nursing students' learning process and personal development could provide deepen point of view of the new training experience, to better guide the internship’s organization for future similar events or highly critical scenarios, such as COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, this study explored nursing student professional development experiences during internships in COVID-19 unit.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Design

A qualitative study was performed to explore the nursing student process of learning and professional development during internships with COVID-19 patients, using the constructivist grounded theory (CGT) approach (Charmaz, 2006). CGT is an optimal method to explain social processes and human behaviour (Hutchinson et al., 2001) and has widespread use in nursing, education and sociology areas (Charmaz, 2014). It enables data analysis on flexible yet rigorous analytic procedures, thereby encouraging researcher reflexivity (Charmaz, 2006), whose epistemological perspectives embrace constructivism (Charmaz, 2014).

2.2. Setting and sample

The study was conducted at two universities in northern Italy and involved bachelor-degree nursing students in their third year during the internships with COVID-19 patients. The first nine participants were engaged using purposive sampling (Patton, 2002) and a preliminary analysis of their experiences allowed us to identify initial key concepts or categories (Noble and Gary, 2017). After that, theoretical sampling was adopted to complete data collection; analysis was performed during data collection to guide us in selecting necessary data and consequently shape the emerging theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). Last, once the theoretical saturation was reached, the sampling was concluded, because no new insights emerged from the data (Charmaz, 2014). Indeed, according to CGT, reaching data saturation is not related to the sample size and Charmaz (2006) described the saturation of data related to categories (Charmaz, 2006). The final sample consisted of 28 nursing students. Table 1 presents the main sample characteristics: participants were aged 21–25, 89% were female and 14 students had an internship with COVID-19 patients in Medical Setting, 13 of which were stationed in Critical Care Setting and 3 in Surgical Setting. The internship lengths ranged 15–150 days with an average of 57 days.

Table 1.

Socio-demographics and professionals characteristics of participants (N = 28).

| N (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 3 (11) |

| Female | 25 (89) |

| Unit | |

| Medical Setting | 14 (50) |

| Critical Care Setting | 11 (39.3) |

| Surgical Setting | 3 (10.7) |

| Country | |

| Pavia | 8 (28.6) |

| Milan | 20 (71.4) |

| Mean (range) | |

| Age (Years) | 22 (21–25) |

| Internship lasting (days) | 57 (12–75) |

2.3. Data collection

Eligible nursing students were contacted via the head-of-school office at each university, which provided information about the research and requested their availability. Then, we invited potential participants via email to participate in a face-to-face interview or online interview and then we emailed them a demographic questionnaire and consent form once they accepted. All eligible participants consented to participating in the study.

34 semi-structured interviews were conducted between January and April 2021 by a female researcher (PhD) with expertise in conducting qualitative-research interviews to ensure consistency and accuracy. The researcher didn’t know before any participants of our study, but a presentation of the aim of the study and the researcher was conducted before the start of data collection. This strengthened the rigour of the study and ensured that the ethical principles of data confidentiality were adhered to. During data collection, it was necessary to interview six participants twice to delve deeply into their experience. Before starting data collection, we developed an interview guide consisting of initial, intermediate and final semi-opens questions (Charmaz, 2014). An initial open-ended question such as: ‘Tell me about your experience of internship in COVID-19 patients, please?’ was necessary to ensure and to maintain a non-judgmental non‐leading approach. Thereafter, we asked questions that focused on the research topic, i.e. the process of learning (Charmaz, 2014); for instance: ‘How did you learn and acquire skills?’, ‘How did this experience hinder your learning?’ and ‘How did you face the main challenges and difficulties?’. We modified the interview guide during data collection due to the emergence of new topics. Most of the interviews were conducted face to face in a private location to ensure privacy and foster confidentiality. Only five interviews were conducted online (Saarijärvi and Bratt, 2021). Each interview lasted approximately one hour; these were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

2.4. Data analysis

According to the analytical approach of Charmaz (2014), data analysis was developed starting from the manual coding stage. Through the memoing process, categories were developed. Concepts and key phrases were highlighted and moved into subcategories to ensure we could make sense of the data. Specifically, the constant comparison of similarities and differences between the categories achieved the level of abstraction of the terms and produced highly inclusive abstract terms called the core category. The core category consists of chief phenomena on which the categories (and the theory itself) are built. In fact, the categories that emerged (including the core category) allowed us to develop a substantive theory, in particular in the context where it occurs. Every participant to the study checked findings.

2.5. Rigour and reflexivity

The rigour of our study was ensured following the COREQ checklist (File Supplementary 1) (Tong et al., 2007). CGT value and quality are guaranteed by systematically applying the four criteria of rigour suggested by Charmaz (2014): credibility, originality, resonance and usefulness. Study credibility was ensured by accurately transcribing interviews, taking extensive field notes and making constant comparisons and member checking. A deep reflexivity processes, including writing memos and reviewing the existing literature, determined the originality of the findings. To ensure consistency, each participant confirmed our interpretation of each interview and agreed with emerging categories. Lastly, the criterion of usefulness is respected because of the importance of practice implication of theoretical model developed to improve quality of nursing education and learning process and personal development of nursing students in emergency setting.

2.6. Ethical consideration

The institutional review board of the local nursing universities involved evaluated and approved this study. All participants were informed about the aims of the study; the researchers read the material carefully and explained the process prior to each interview. Informed consent was requested, and participants were informed about the study aims and data collection procedures, which were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964). Participants could withdraw from the study at any time. Data confidentiality and anonymity were ensured. In particular, researchers dedicated to data analysis didn’t know the identity of the interviewers. Data were collected by assigning each interview an alpha-numeric code in compliance with the law concerning personal data protection. Every participant was asked to confirm results emerged from interviews. Furthermore, data were kept in a password-protected computer and used only for this project. So, nine coders coded data to build up the four categories and the core category.

3. Findings

According to the nursing students’ experiences during their internship with COVID-19 patients, we found that, despite difficulties, their learning process developed along a rich and accelerated training path with significant characteristics compared to previous internship experiences, comprising their personal development and growth. This new learning process is composed of the core category, that is the ‘Students’ sense of belonging to the nursing profession’ and four main categories: (1) from knowledge to know-how; (2) a new relationship modality; (3) sharing and socialisation; and (4) greater responsibility. Finally, a premise and a corollary, respectively the motivation and the circularity of the process, were identified, as can be seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The nursing students' learning process during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.1. Core category: students’ sense of belonging to the nursing profession

According to the students, being involved in care teams was an enriching experience that made them feel ‘grown up’. In this new experience, they recognised a source of enrichment at the personal level: ‘The experience in the COVID-19 unit let me feel much more confident… I didn’t know anything about COVID-19 or very little… now it's different because I contributed to the pandemic during the internship with other nurses… it was more like a real job for me …’ (S3); ‘Yes, I’ve learnt to… to feel the team. and to become part of it… I learnt a lot from this experience’ (S14); ‘Being helpful… here and now. I was happy. I felt richer. You get so much from it. and I felt. as I was doing my job with them’ (S15). This allowed us to better link all the other categories, in particular “Students’ sense of belonging to the nursing profession”, was developed as the key-role aspect of the entire learning process which moved nursing students’ to their training programme at the bachelor’s degree course, in a highly critical scenario.

3.2. First category: from knowledge to know-how

Student started the learning process from asking continuously to the clinical guide. After that, students strove to remember their knowledge and contextualise it within clinical practice. This was characterised by them recognising university-taught theory in a highly critical context. We identified three sub-categories: (a) asking; (b) remembering the theory; and (c) contextualising. During the learning process, the students observed the new context they found themselves in and their learning process started from asking to the team probing questions. A student said, ‘I was very focused on asking a lot of things and so I asked everything I didn’t know… I was a little sponge in the unit…’ (S3). Furthermore, students were intrinsically motivated, which facilitated their application of theory in a clinical context: ‘Everything was new for me… For example, the arterial blood gas analysis… studying it at the university is a thing… but reading it in the clinical context is different. because you really want to learn it’ (S16). Therefore, it is evident that these nursing students succeeded in combining theory with the practical aspects of a clinical context: ‘But then you think that they have 60 litres per minute so you have to consider it occurs because… if they didn’t have 60 litres per minute, how much would they saturate? Twenty? That’s a problem!’ (S1). Indeed, the nursing students were able to identify patient needs by applying theory in a clinical setting, recognising compromised needs.

3.3. Second category: a new relationship modality

By combining theory with practical aspects, students attempted to develop deep relationships with the COVID-19 patients. However, they reported feeling ‘a wall’ between them and the patients due to personal protective equipment and quarantine restrictions. Consequently, nursing students had to encourage the use of the words to address this gap. We identified two sub-categories: (a) changing the use of words; and (b) rediscover touching. According to the students, developing a relationship with patients was a challenge and the use of words was the only way to establish a relation in such a dramatic context: ‘And so it becomes very hard to be in relationship and it is very important to try to… also through words… try to give comfort and reassurance also in this time…’ (S3). Students wanted to know and address patient needs and they recognised this as a difficulty: ‘Communicating in caring can be understood, but it is very difficult as climbing a mountain… but then, as time goes on, you understand it is not as it seems… because there’s always a patient who [will] listen to you and trust you… and so… you overcome this difficulty…’ (S6). They succeeded in overcoming this difficulty, rediscovering touching in the nursing care: ‘No, nobody has never given me the hand; they don’t do it if they’re agitated. It was a new thing… I understood he was very important to me… I was there with him…’ (S26).

3.4. Third category: sharing and socialisation

Students were able to share the factors that made them feel ‘grown up’ when tending to the COVID-19 patients. Feeling comfortable facilitated the learning process and the environment and team helped the students to learn about caring and to face difficult situations. We identified two subcategories: (1) team support; and (2) clinical guide support. ‘We had the possibility to discuss [some] of your decisions and we were not considered just students… they organised briefing… they trusted me, but they were always available for discussion’ (S4). This was possibly due to the continuous support offered by the clinical guides and the attention they gave to the nursing students: ‘They had an attention for me… and they tried always to know how I felt because I had to face a difficult situation and he and he always asked me, ‘Is everything fine? Don’t worry I’m here…’ (S14). Indeed, the clinical guide was important in the nursing students’ learning process.

3.5. Fourth category: responsibilization

In this dramatic context, the students were successful in learning nursing care. Due to team support, they learnt about the clinical context and how to take care of COVID-19 patients. This was a landmark method in teaching nurses the practical skills required in stressful environments.

We identified two sub-categories: (1) to be encouraged; and (2) to become a landmark. The nursing students were shouldered with the responsibility of caring for COVID-19 patients: ‘The clinical guide taught me a lot… he’s a person who is self-aware and I like him because he taught me a lot of things and then… he was not the one makes you feel relaxed, but he helped you to go and do things and… how can I say? To take your responsibilities’ (S16). Therefore, the students were motivated to be a part of a team, even for minuscule things: ‘Last week a new nurse started to work with us… and so I explained to her how programmes work… I was a landmark for someone else’ (S14).

3.6. The premise: motivation

The new learning process was made possible due to intrinsic motivation. Student motivation was the driving factor for the entire learning process; it is intrinsic that, in a such dramatic context, made the learning process possible: ‘I said, “and now what can I do?” but then I thought, no, I’m here and I must do it… I have to go on and learning as much as possible’ (S2); ‘The experience in [the] COVID-19 unit let me feel much more confident and I’ll remember it more than other experiences because it was very different… there was that damnn virus there… and I wanted to do it… despite of difficulties… because I knew I could do it.’ (S5); ‘You have to show who you are, what you can do’ (S7).

3.7. The corollary: circularity of the process

By acquiring new responsibilities, the nursing students learnt to navigate COVID-19 by combining theoretical knowledge obtained at university with practical clinical aspects: ‘She was responsible of me and of what I was doing in that moment, and it helped be to be more confident and I can manage situations by myself, thanks to the theory, because it is fundamental to know how to do things in the clinical context (S16)’.

4. Discussion

Our study explored, for the first time, nursing students’ learning processes and professional development during internships with COVID-19 patients. Nursing students were able to apply their knowledge to a new and highly demanding clinical context, both physically and mentally and, despite anxiety and some concerns and numerous challenges, they learned and have grown and taken a step further towards being health professionals, in taking care of COVID-19 patients. Research in the field of teaching and learning in nursing education is rich, underlining the high complexity of this process, especially to ensure quality in the nurse degree course, to build strong competencies in future nurses. Various theories that guide the nursing students’ learning processes and professional development are described in the literature, but still, no theory has been studied for learning while caring for the COVID-19 patients. Accordingly, our study seems to lay the foundations for hypothesising new nuances in the dynamics of the nursing student's learning, related to the uniqueness of the pandemic period.

Experience is a fundamental aspect of learning, allowing an actively and independently participation by students, driving the desire for self-realisation and helping to develop the learner's identity (Deyhim et al., 2006). However, when students move on to the 'real world', they are expected to be equipped with appropriate technical and communicative skills and competencies and some understanding of the complexities of the context where they will use their skills. But it’s not simple and the nursing students’ focusing on theoretical foundations can help students to reach it. We describe this in the first theme: recognising and using the university-taught theory had allowed to nursing students to able to face and grow in a highly critical context. Our results seem to emerge as the theory learned during the training course was a lever for the activation of the student's learning process.

The beginning of learning cycle from theoretical foundations is recognise by White and Ewan's (1997) theory, describing that student learning begins with preparatory theory (White and Ewan, 1997). Furthermore, White and Ewan (1997) described the important role of briefing phase for starting in the nursing students' internship, as briefing phase can allow to nursing students to strength their theoretical preparation for practice which they are to face to. Therefore, even if we do not have data that support the presence of a briefing phase at the beginning of the internship with COVID-19 patients, we can assume that it has been done (Garrino et al., 2015). We can hypothesise that theme 3 emerged describe an undeclared and structured form of briefing between the student and team or clinical guide. Indeed, nursing students referred to feel comfortable with clinical tutors and other nurses, which allowed him to better improve their technical and theoretical skills.

The sense of belonging to the nursing profession, which was identified as the core category, was the basis of the entire learning process in the clinical context, as it resulted in each student contributing to the team. According to Maslow (1987) theory, this sense of belonging is a universal human need, a need for affiliation (Albloushi et al., 2019). Literature describes the need to belong as a fundamental human motivation with a powerful influence on cognitive processes, emotional patterns, behavioural responses and health and well-being (Baumeister and Leary, 1995, Sargent et al., 2002), highlighting the links between belonging and academic engagement and performance (De Beer et al., 2009, Pym et al., 2011).

Furthermore, the sense of belonging influences the decision-making process, as the fundamental part characterising nursing professional development (Santos, 2020) and Zumbrunn et al. (2014) suggested that attributes of passion, enthusiasm, interest and care from academics for their students play a role in fostering motivation and engagement from students (Zumbrunn et al., 2014). So, in light of this, we believe that investment of resources in creating learning environments which foster the nursing students’ sense of belongingness are need, becoming a fundamental pillar in academic strategy, to facilitating student nurses’ engagement in their learning and consequently improving the qualities and competencies in future nurses (Dunbar and Carter, 2017).

5. Conclusion

This study proposed a theory of learning and professional development for nursing students in internships with COVID-19 patients, thereby identifying, for the first time, the importance of internships in a pandemic context. The internship with COVID-19 patients had significant repercussions for the nursing students, both physically and mentally, as they faced several difficulties and challenges. Despite this, due to intrinsic motivation, they were successful in this new learning environment. By rigorously implementing CGT methodology, this research developed a theoretical model of the learning dynamics of nursing students. However, this model cannot be applied to junior nursing students, as they were excluded from the study. Furthermore, this research is limited to a specific cultural context, so the results are not entirely generalisable. So, further studies are required. Our study contributes by providing a guide to nursing education during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the theory that could better explain and describe the entire learning process, which has been modified from the existing one (White and Ewan, 1997) by the COVID-19 pandemic. It can be used to rethink the nursing education curriculum and to organise optimal internship and university experiences.

6. Implications for practice

Numerous aspects of diversity resulting from the historical period of the COVID-19 pandemic, allowed a profound change in the process of learning implemented by the student, in particular, if compared to other internship experiences, to develop skills and professional and personal growth even if in a highly critical scenario.

The experience of clinical internship in the COVID-19 unit allowed the nursing student to manage learning in a new way, strengthening the relationship with the patient and integrating into the entire team, which pushed him to take responsibility and learn to take care of the COVID-19 patient, despite the countless difficulties. Therefore, our results should support the organization's future clinical internships of nursing students in an emergency context health, ensuring the training of the student enroled in the third year of the nursing bachelor’s degree course and, therefore, so near to the exercise of the nursing profession.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103502.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- Albloushi M., Ferguson L., Stamler L., Bassendowski S., Hellsten L., Wilkinson A. Saudi female nursing students experiences of sense of belonging in the clinical settings: a qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019;35:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzrodt C.L., Manknojia I., McCarthy R., Oldfield T.K., Stepp H., Clements T. A guide to COVID-19: a global pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. FEBS J. 2020;287:3633–3650. doi: 10.1111/febs.15375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldini F., De Luca W. Covid-19 E Studenti Di Infermieristica in Prima Linea: Una Riflessione. NSC Nurs. 2021;1(2):25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Barisone M., Ghirotto L., Busca E., Crecitelli M.E., Casalino M., Chilin G, Milani S, Sanvito P, Suardi B, Follenzi A, Dal Molin A. Nursing students’ clinical placement experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic: A phenomenological study’. Nurse Education in Practice. 2022;59(103297) doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R.F., Leary M.R. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobbo N., Moretto B. Didattica e tirocinio a distanza nel corso di studi in Educazione professionale: una valutazione formativa dell’accoglienza da parte degli studenti dell’offerta. J. Health Care Educ. Pract. 2020;2(2):102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Casafont C., Fabrellas N., Rivera P., Olivé-Ferrer M.C., Querol E., Venturas M., Prats J., Cuzco C., Frìas E., Péerez-Ortega S., Zabalegui A. Experiences of nursing students as healthcare aid during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: a phemonenological research study. Nurse Educ. Today. 2021;97:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis, Sage Publication. first ed. Sage Publication; New York: 2006. (Chapter 1) [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis, Sage Publication. second ed. Sage Publication; New York: 2014. (Chapter 3) [Google Scholar]

- De Beer J., Smith U., Jansen C. ‘Situated’ in a separated campus–students’ sense of belonging and academic performance: a case study of the experiences of students during a higher education merger. Educ. Chang. 2009;13(1):167–194. [Google Scholar]

- Deyhim F., Lopez E., Gonzalez J., Garcia M., Patil B. Citrus juice modulates antioxidant enzymes and lipid profiles in orchidectomized rats. J. Med. Food. 2006;9(3):422–426. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.9.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar H., Carter B. A sense of belonging: the importance of fostering student nurses’ affective bonds. J. Child Health Care. 2017;21(4):367–369. doi: 10.1177/1367493517739977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadhliah Mahmud N.F., Mohamad Ali A., Mei Yuit C. Review of studies on oral case presentations in clinical settings. Malays. J. Lang. Linguist. 2014;3(1):108. [Google Scholar]

- García-Martín M., Roman P., Rodriguez-Arrestia M., Diaz-Cortes M., Soriano-Martin P.J., Ropero-Padilla C. Novice nurse’s transitioning to emergency nurse during COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021;29(2):258–267. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrino L., Arrigoni C., Grugnetti A.M., Martin B., Cola S., Dimonte S. Il briefing e il debriefing nell’apprendimento protetto in simulazioni per le professioni della cura: analisi della letteratura. MEDIC. 2015;23(2):73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B.G., Strauss A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. first ed. Routledge; New York: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Martínez A., Rodriguez-Almagro J., Martìnez-Arce A., Romero-Blanco C., Garcìa-Iglesias J., Gòmez-Salgado J. Nursing students’ experience and training in healthcare aid during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021;00:1–8. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson S.A., Munhall P.L., Oiler B.C. Nursing Research: A Qualitative Perspective. first ed. Jones and Barlett Learning; Boston: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Intinarelli G., Wagner L.M., Burgel B., Andersen R., Gillis C.L. Nurse practitioner students as an essential workforce: the lessons of coronavirus disease 2019. Nurs. Outlook. 2021;69(3):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno C., Wykes T., Galderisi S., Nordentoft M., Crossley N., Jones N., Cannon M., Correll C., Byrne L., Carr S., Chen E., Gorwood P., Johnson S., Karkkainen H., Krystal J.H., Lee J., Lieberman J., JAramillo C.L., Mannikko M., Philips M.R., Uchida H., Vieta E., Vita A., Arango C. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(7):16–17. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble H., Gary M. What is grounded theory? Pediatr. Nurs. 2017;43(6):34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Seo M. Influencing factors on nursing students. learning flow during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed method research. Asian Nurs. Res. 2022;16(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2021.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M.Q. Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: a personal, experiential perspective. Qual. Soc. Work. 2002;1(3):261–283. [Google Scholar]

- Pym J., Goodman S., Patsika N. Does belonging matter?: Exploring the role of social connectedness as a critical factor in students’ transition to higher education. Psychol. Soc. 2011;42:35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Saarijärvi M., Bratt E.L. When face-to-face interviews are not possible: tips and tricks for video, telephone, online chat and email interviews in qualitative research. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2021;20(4):392–396. doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvab038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos L.M.D. The relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and nursing students’ sense of belonging: the experiences and nursing education management of pre-service nursing professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(16):5848. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent J., Williams R.A., Hagerty B., et al. Sense of belonging as a buffer against depressive symptoms. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2002;8(4):120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tolyat M. Education of nursing profession amid COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Prof. 2022;10(1):39–47. doi: 10.30476/JAMP.2021.90779.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R., Ewan C. Clinical Teaching in Nursing. first ed. Nelson Thornes; United Kindom: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J.D., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M., Gill H., Phan L., Chen-Li, Iacobcci M., Ho R., Majeed A., McIntyre S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. Elsevier Connect. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumbrunn S., McKim C., Buhs E., et al. Support, belonging, motivation and engagement in the college classroom: a mixed method study. Instr. Sci. 2014;42(5):661–684. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material