Abstract

A 43-year-old male patient presented with acute blurring of vision in both eyes associated with photophobia, redness, and mild pain following coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) infection. Clinical examination revealed extensive pigment dusting in the corneal endothelium and the trabecular meshwork with de-pigmentation bands in the iris periphery. The patient was managed empirically with topical anti-glaucoma medications for high intra-ocular pressure. The patient was prescribed systemic antibiotics including cephalosporins and amoxicillin for respiratory symptoms. A rare condition called bilateral acute de-pigmentation of iris (BADI) was suspected after ruling out common entities, for example, viral kerato-uveitis, pigment dispersion syndrome, and Fuchs iridocyclitis. Covid-19 infection and systemic antibiotics including cephalosporins have shown to cause BADI in the literature. The patient responded well with good outcome.

Keywords: Acute uveitis, BADI, Covid-19, ocular hypertension

Bilateral acute de-pigmentation of iris (BADI) is a distinct entity that consists of bilateral, acute, symmetrical de-pigmentation of the iris stroma with pigment deposition in the anterior chamber with increased intra-ocular pressure (IOP).[1] It has been described more commonly in middle-aged females and is usually associated with viral prodromes and more recently with coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) infection.[2]

Since it was first described in 2009 by Tutkun et al.,[1] many associations were observed with this entity. Bilateral acute iris transillumination defect (BAIT)[3] is another close disease entity comprising iris stromal atrophy with pigment dispersion and pupillary abnormalities. These entities should be identified and differentiated from other common diseases, for example, Fuchs iridocyclitis, herpetic iridocyclitis, and pigment dispersion syndrome.

We report a case with features suggestive of BADI with associated Covid-19 infection. It was well managed conservatively.

Case Report

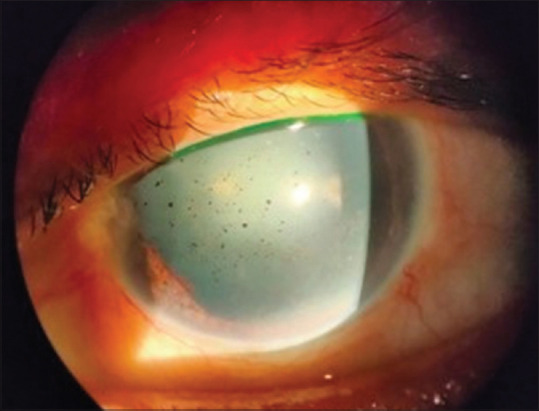

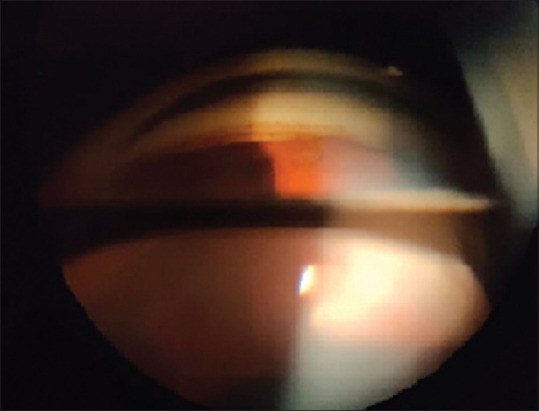

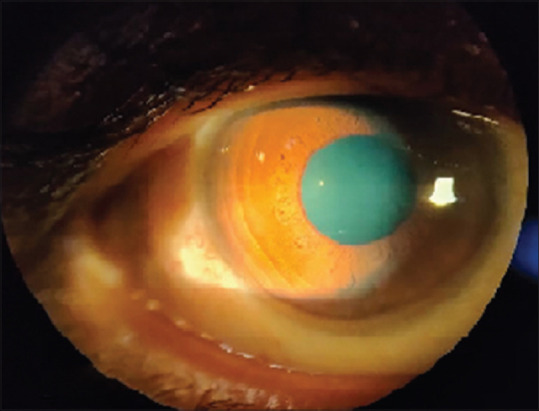

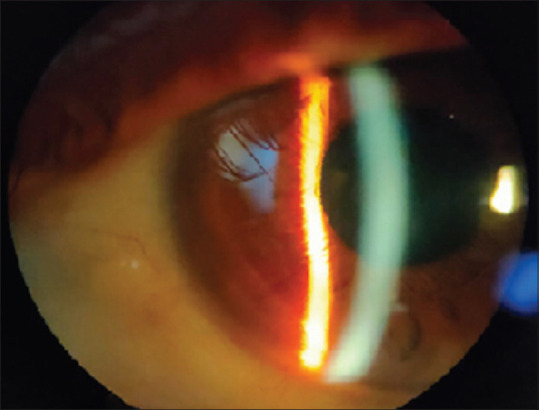

A 43-year-old male patient presented with complaints of blurred vision in both eyes with redness, mild pain, and extreme photophobia for 1 week. He had a history of Covid-19 infection 2 months back, which was followed by a second episode of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive Covid-19 infection 10 days back, and was taking oral antibiotics including cephalosporins and amoxicillin. Past ocular history, systemic history, and family history were unremarkable. On clinical examination, the visual acuity in both eyes was 20/40. The conjunctiva had ciliary congestion; the cornea showed diffuse pigment dusting on the endothelium with epithelial edema and a few superficial punctate defects, which stained well with fluorescein [Fig. 1]. The anterior chamber had a normal depth with grade III pigments. Gonioscopy showed open angles and pigment deposition in the trabecular meshwork [Fig. 2]. The iris had mild de-pigmentation at the periphery near the iris root with normal configuration with no pupillary abnormalities. Fundus examination was normal with no vitreous cells. The IOP was found to be 48 mm Hg in the right eye (RE) and 44 mm Hg in left eye (LE). We made the differential diagnosis of acute anterior uveitis with secondary glaucoma. Viral uveitis was ruled out as there were no Keratic Precipitates (KPs), sectoral iris atrophy, and loss of corneal sensations. The patient was conservatively treated with topical steroid drops every 2 hours and anti-glaucoma medications, including oral acetazolamide with eye drop timolol and brimonidine. After 3 days, the patient was symptomatically better, but the cornea still had pigment dusting involving the endothelium. We further added systemic Acyclovir 400 mg empirically for 10 days assuming it to be of atypical herpetic etiology. We did not perform viral PCR testing of aqueous humor. After 10 days, the visual acuity improved up to 20/20 in both eyes with an IOP of 14 mm Hg in RE and 12 mm Hg in LE. The anterior segment showed a few pigments in the anterior chamber [Fig. 3]. The cornea was also relatively clear in both eyes [Fig. 4] with less pigment deposition noted in the trabecular meshwork [Fig. 5]. After doing literature review for similar presentation, we considered a provisional diagnosis of Covid-19-related BADI. However, the patient responded to systemic acyclovir; the possibility of BADI cannot be ruled out completely. On fundus examination, we noted bilateral disc edema with good foveal reflex [Figs. 6 and 7]. The visual field and neurological work-up were normal. Disc edema resolved after 2 weeks [Figs. 8 and 9]. No ocular cause could be found on examination for disc edema, and fundus fluorescence angiography could not be performed as the patient was not cooperative. The de-pigmentation of the iris remained in the iris periphery as bands until our last follow-up 1 month later [Fig. 10]. After 2 months following presentation, the best corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes with IOP within normal limits.

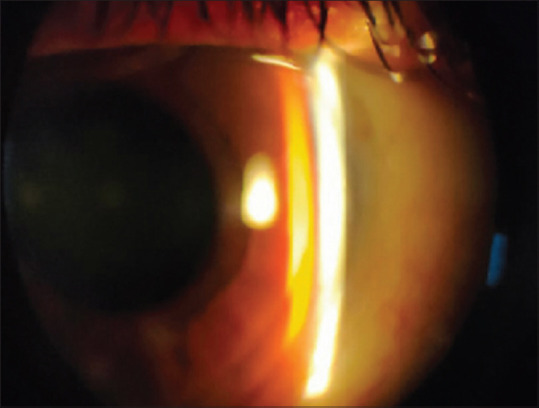

Figure 1.

Left eye (LE) in gross examination showing pigment dusting involving the corneal endothelium with the corneal haze

Figure 2.

Left eye (LE) gonioscopy image showing open angles with pigment deposition in the trabecular meshwork

Figure 3.

Left eye (LE) showing resolution of the corneal haze, pigment dusting in the corneal endothelium, and the anterior chamber

Figure 4.

Right eye (RE) showing resolution of the corneal haze, pigment dusting in the corneal endothelium, and the anterior chamber

Figure 5.

Gonioscopy picture of LE showing resolution of pigment bands in the trabecular meshwork

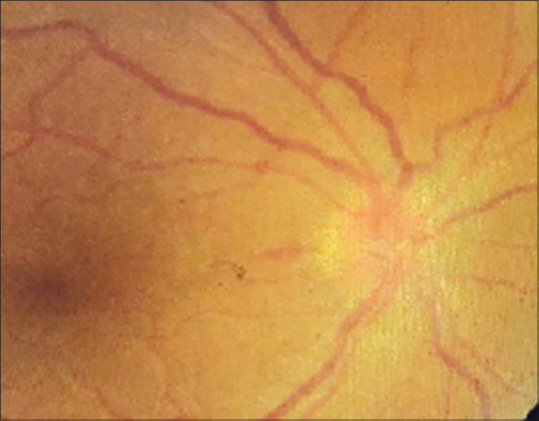

Figure 6.

Right eye (RE) showing disc edema with splinter hemorrhage over the disc in RE

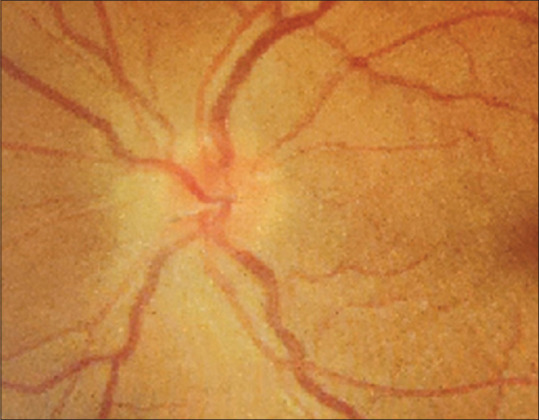

Figure 7.

Left eye (LE) showing disc edema with splinter hemorrhage over the disc in RE

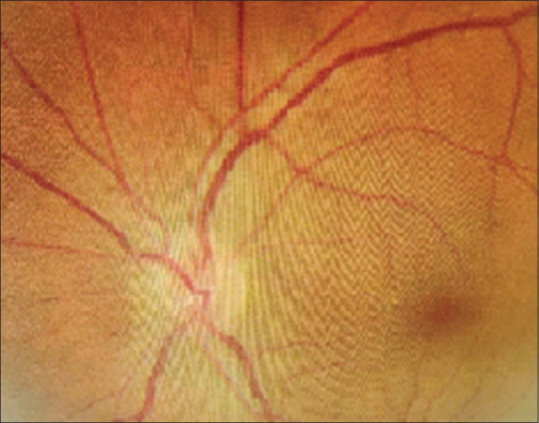

Figure 8.

Left eye (LE) showing resolution of disc edema and splinter hemorrhage over the disc in RE

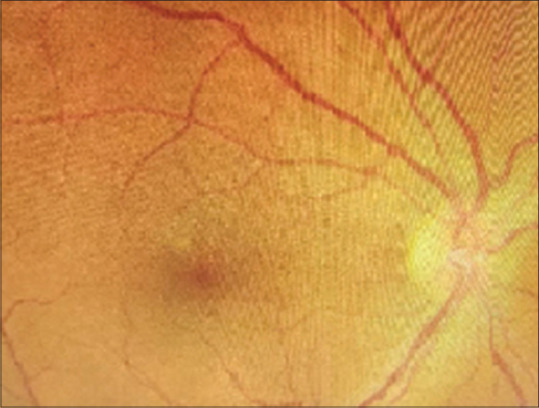

Figure 9.

Right eye (RE) showing resolution of disc edema and splinter hemorrhage over the disc in RE

Figure 10.

Image showing iris de-pigmentation bands involving the periphery of the iris

Discussion

BADI is a distinct entity and was first described by Tutkun et al.[1] in 2006, and since then, there have been many reports in the literature describing its variable features and associations. Studies suggested BADI following acute viral prodromes or associated with certain medications, including fluoroquinolones.[4] Among medications, systemic use of moxifloxacin was found to be associated in most of the cases (66% cases).[5] In a case series, Tugan-Tutkun described features of BAIT, followed by viral prodromes and systemic antibiotics including moxifloxacin (35% cases) and amoxicillin-clavulanate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cefixime, and penicillin V.[6] Therefore, temporal relationship of BAIT and antibiotic therapy could not be established, but the history of viral prodromes was thought to be significant.[6] Most cases of uveitis were seen after 13 days on average.[7] It is of utmost importance to rule out other entities first to make a diagnosis of BADI.

Pigment dispersion syndrome was also present with anterior chamber pigment deposition and high IOP. The pigments are derived from the posterior pigmented epithelium of the iris and are seen not only in the anterior chamber and endothelium but also in the lens epithelium, zonules, and angle.[8] Herpetic iridocyclitis can also present with anterior uveitis with pigment dusting over the endothelium. Differentiating features from BADI are the presence of KPs, sectoral iris atrophy, and decreased corneal sensation. These can be diagnosed definitely with PCR testing of aqueous humor.[9] Fuchs iridocyclitis can be differentiated with the presence of stellate diffuse KPs and unilateral presentation. However, it is bilateral in 5–10% of the cases.[10] Another similar clinical entity described is BAIT, which can be differentiated with the presence of iris transillumination defects and sphincter paralysis.[3] Moreover, the source of iris pigments in BADI is the iris stroma, whereas in BAIT, it is the posterior pigmented epithelium of the iris.

Covid-19 is also associated with uveitis-like features, and BAIT is already described in the literature.[2] The patient had a positive history of Covid-19 and antibiotic use. Although the patient responded after starting empiric acyclovir, it may be coincidental, and the possibility of BADI/BAIT cannot be ruled out considering that not much is clearly described about this new entity in the literature.

Conclusion

BADI and BAIT are uveitic masquerades and usually are self-limiting. The exact pathogenesis is still unknown. Gene sequencing analysis of aqueous humor or tears from BADI or BAIT patients may help to discover the unknown causative organism if at all present. The role of antibiotics still needs to be established. Covid-19 is associated with BADI and BAIT and should be kept in mind and treated accordingly.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tugal-Tutkun I, Urgancioglu M. Bilateral acute depigmentation of the iris. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:742–6. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yagci BA, Atas F, Kaya M, Arikan G. COVID-19 associated bilateral acute iris transillumination. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:719–21. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1933073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tugal-Tutkun I, Onal S, Garip A, Taskapili M, Kazokoglu H, Kadayifcilar S, et al. Bilateral acute iris transillumination. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:1312–9. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wefers Bettink-Remeijer M, Brouwers K, van Langenhove L, De Waard PWT, Missotten TO, Martinez Ciriano JP, et al. Uveitis-like syndrome and iris transillumination after the use of oral moxifloxacin. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:2260–2. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bringas Calvo R, Iglesias Cortiñas D. Acute and bilateral uveitis secondary to moxifloxacin. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2004;79:357–9. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912004000700011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perone JM, Chaussard D, Hayek G. Bilateral acute iris transillumination (BAIT) syndrome:Literature review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:935–43. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S167449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinkle DM, Dacey MS, Mandelcorn E, Kalyani P, Mauro J, Bates JH, et al. Bilateral uveitis associated with fluoroquinolone therapy. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:111–6. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2011.617024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niyadurupola N, Broadway DC. Pigment dispersion syndrome and pigmentary glaucoma--a major review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:868–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siverio CD, Imai YD, Cunningham ET. Management of Herpetic Anterior Uveitis. International Ophthalmology Clinics:Winter. 2002;42:43–8. doi: 10.1097/00004397-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atilgan CU, Kosekahya P, Caglayan M, Berker N. Bilateral acute depigmentation of iris :3-year follow-up of a case. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2018;10:2515841418787988. doi: 10.1177/2515841418787988. doi:10.1177/2515841418787988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]