Abstract

Myopia or short-sightedness is an emerging pandemic affecting more than 50% population in South-Asian countries. It is associated with several sight-threatening complications, such as retinal detachment and choroidal neovascularization, leading to an increased burden of visual impairment and blindness. The pathophysiology of myopia involves a complex interplay of numerous environmental and genetic factors leading to progressive axial elongation. Environmental factors such as decreased outdoor activity, reduced exposure to ambient light, strenuous near work, and role of family history of myopia have been implicated with increased prevalence of this refractive error. While multiple clinical trials have been undertaken to devise appropriate treatment strategies and target the modifiable risk factors, there is no single treatment modality with ideal results; therefore, formulating a comprehensive approach is required to control the myopia epidemic. This review article summarizes the epidemiology, dynamic concepts of pathophysiology, and evolution of the treatment modalities for myopia such as pharmacological (atropine and other agents) and optical methods (spectacles, contact lenses, and orthokeratology).

Keywords: Atropine, childhood myopia, contact lenses, orthokeratology, refractive error, spectacles

Myopia or short-sightedness is an emerging pandemic. Its prevalence has been rising steadily worldwide and has reached alarming proportions, especially in South-East Asia. A recent meta-analysis by Holden et al.[1] predicted that nearly 50% of the world’s population will become myopic by 2050, with 10% of them being high myopes. Besides the sight-threatening complications such as retinal detachment, myopic maculopathy, and choroidal neovascularization, the economic burden and the social impact of myopia are significant.[2] Though several factors such as genetic predisposition and environmental causes are instrumental in the pathogenesis, the discrete role of each of these to target the onset and delay the progression of myopia remains ambiguous. In the quest for the ideal treatment, many pharmacological, optical, and environmental modalities are being explored. This review intends to summarize the current concepts regarding epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, risk factors, and various preventive/curative modalities for myopia control.

Epidemiology

Recent studies have observed a rising trend of myopia in most populations worldwide, with prevalence reaching up to 69% by the age of 15 years in the urban population of East Asia.[3,4,5] Several independent studies confirm a greater predisposition for myopia in Chinese ethnicity than the white population.[6,7,8] Among Caucasians, the estimated prevalence of myopia ranges from approximately 26% in the United States and Western Europe to 16% in Australia and has superseded hyperopia as the most prevalent refractive error.[9]

In India, nearly doubling of myopia prevalence, that is, from 7.4% to 13.1%, was observed when compared with the previous decade in urban schools of Delhi.[10] A recent meta-analysis of the last four decades from India reports a rising trend of myopia in the country with narrowing of the urban-rural gap in myopia prevalence.[11] Young age and female gender are found to be at higher risk. Gender predisposition, although not noted in many studies, is mostly explained by the fact that girls engage less in outdoor activities compared to boys.[11,12]

Pathophysiology

Failure of emmetropisation

During the normal process of emmetropisation, the eye expands in all directions (axial and equatorial) and is associated with mechanical stretching and thinning of the crystalline lens along the equatorial plane, which results in a decrease in the power of the lens. A decoupling between this process of axial elongation and flattening of the corneal and lens curvature causes escalated axial growth and arrest of lens thinning by disruption of the equatorial expansion, leading to myopia.[3] The Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Ethnicity and Refractive Error (CLEERE) Study, an observational cohort study of ocular development and myopia onset, found that an accelerated axial elongation (up to three times faster) was noted in myopic subjects 1 year before and after the onset of myopia, making axial growth a major determinant of the refractive status of the eye.[13]

Peripheral retinal hyperopic defocus

The role of retinal defocus and peripheral hyperopia as a precursor in the onset and progression of myopia has also been widely explored. Animal studies have shown that eye growth is regulated by the location of the image plane to compensate for the defocused image seen. Therefore, the chicken eyes occluded with a negative lens (hyperopia induced) grew more toward the image plane behind the retina and became myopic.[14] Axial elongation is not commonly observed in patients with central macular pathologies such as toxoplasma scar, whereas neonates undergoing laser ablation of the mid-peripheral retina for retinopathy of prematurity are known to show myopic shift consequently, depicting a biological basis of the emmetropization with the sensory stimulus located somewhere in the mid-peripheral retina.[15]

The target tissue and the sensory part are proposed to be integrated via some messenger molecules, such as dopamine, and this is where the role of muscarinic receptors and their antagonists such as atropine and pirenzepine come into play.[16,17,18,19,20,21] Various studies have proposed different target tissues such as the sclera,[22] the choroid,[23] and more recently, the Bruch’s membrane.[18] However, there remains ambiguity about the exact target tissue that drives this feedback loop.

Risk Factors

Myopia occurs due to a complex interplay between numerous factors such as genetic predisposition, parental myopia, ethnic differences, and environmental factors. However, the role of each in lowering the incidence and progression of myopia is not specifically defined.

-

Refractive error: The CLEERE study group observed that children who became myopic showed significantly more axial elongation starting 3 years before the onset and up to 5 years after the onset of myopia, and it was fastest in the preceding year before onset.[13] Less hyperopic/more myopic refractive error at baseline was found to be the most important risk factor predictive of juvenile-onset myopia by Zadnik et al.[24] They also defined the cut-offs for age-normal hyperopia to aid in identifying at-risk groups for myopia: baseline refractive error <+0.75D for grade 1 (6 years), ≤+0.50D for grades 2–3 (7 and 8 years), ≤+0.25D for grade 4 (9 and 10 years), and emmetropia for 11 years. Therefore, baseline refractive error is an important predictor for myopia development.

Keeping this in mind, the International Myopia Institute (IMI) has introduced the concept of “premyopia” to identify children with a greater likelihood of development of myopia. Premyopia has been defined as “a refractive state of the eye of ≤+0.75D and >−0.5D in children by using cycloplegic refraction where the combination of baseline refraction, age, and other quantifiable risk factors predispose to the development of myopia.”[25]

Age: As per the age of onset, myopia can be classified as juvenile-onset type (the most common variety) with peak incidence occurring in elementary schools and the late-onset type coming to light during the teenage years. The lowered age of onset of myopia is associated with a higher rate of progression and greater risk of related debilitating complications such as retinal detachment, myopic macular degeneration, cataract, and glaucoma.[2,26]

Genetics and parental myopia: Myopes tend to have myopic children more often than non-myopes.[3] The risk of developing myopia is increased threefold or more among children with two myopic parents compared to children with no myopic parent.[27,28,29,30,31] However, there exist conflicting views on whether this is solely due to genetic predisposition or due to the myopigenic environment created by myopic parents. In a study by Mutti et al.,[28] heredity was the most important factor having a positive association with juvenile myopia, with smaller contributions from other environmental factors.

-

Environmental factors: There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that environmental factors such as reduced outdoor activity and increased near work play a critical role in the development and progression of refractive errors.

- Outdoor activity: A school-based study from Singapore stated that the potential environmental and behavioral risk factors for myopia progression were reduced outdoor time, less physical activity, and lack of exposure to green spaces and natural daylight together with an excess of near work in children.[32] Saxena et al.[11] in the North India Myopia Study (NIMS) reported that >2 h of outdoor activity had a protective effect on myopia progression. The factor that links the outdoor activity and delayed myopia progression may be increased exposure to bright light (>1000 lux) or the ultraviolet spectrum rather than the level of physical activity as is also evident by the seasonal variation in myopia progression (greater in winters than summers) noted in few studies. The role of dopamine is also being increasingly recognized. Light exposure stimulates retinal dopamine release that has been found to slow axial elongation. Despite these studies, no definite consensus exists explaining the underlying mechanism leading to the beneficial association of outdoor activity in myopia. A more uniform field of view across the retina and less peripheral hyperopic defocus when outdoors may be responsible for the anti-myopia effect.

- Near work and education: It has been stressed that the hours spent in near work and a shorter reading distance are important risk factors for juvenile-onset myopia. As per the study conducted in an Australian school cohort, it was the sustained near work rather than any near activity that predisposed to myopia. The risk of myopia development and progression was found to increase significantly with reading at very close distances (<20 cm) and for continuous periods (>45 min).[33] This view is supported by the concept of short-term changes in the axial length induced by the increase in accommodative demand that is significantly greater in higher myopes than emmetropes. The higher prevalence of myopia in the Asian and Southeast Asian countries with intense educational curriculums and greater academic focus further reinforces the role of near activity in the development of myopia. Possibly, it is the increased accommodation associated with near work that stimulates eye growth. However, recent evidence favors the role of other mechanisms such as accommodation lag that leads to hyperopic defocus.

- Digital screen time: As the dependency on digital devices such as laptops, computers, and smartphones is increasing in children for academic and recreational purposes, the association between myopia and digital screen time has surfaced in several recent studies. Saxena et al.[12] reported >2 h spent on playing video games or television as a risk factor for myopia in school children. With a shift from physical to digital classrooms post-COVID lockdown, a markedly increased screen time has not only impacted ocular health but also predisposed children to the risk of myopia development.[34] However, whether digital screen time is an independent risk factor or mostly related to the effect of increased near activity and resultant reduced outdoor activity is yet to be explored.

Role of circadian rhythm and sleep: Several recent studies have identified newer risk factors for myopia progression. Disruption of sleep[35] and circadian rhythm[36] can have myopigenic effects, and serum melatonin is believed to play a key role in mediating the process.

Other factors: Some other factors such as Chinese or Singaporean ethnicity, decreased physical activity, first-born children, higher socio-economic status, maternal smoking, and urban set-up have been associated with myopia, although the link is weak.

Controlling the Onset and Progression of Myopia

Lifestyle and environmental modifications

Recognition of the modifiable factors involved in myopia pathogenesis is imperative to devise suitable strategies to avert its onset and progression, especially in premyopes.

Many causal factors have been linked to the evolution of the myopia epidemic in its present stage. These can be classified as broad distal factors such as industrialization and urbanization, intermediate factors such as decreased outdoor activities and increased near work, and proximal factors such as heredity and genetics.[37] Morgan et al.[38] elaborated that factors such as a shift to urban areas with confined built-in setup, an overemphasis on academic training with classroom activities in inadequate illumination, increased near work due to introduction of homework at the elementary level, and hereditary predisposition culminate to the increasing myopia prevalence. They suggested reforms in the rigorous educational system by limiting the homework load and laying stress on sports and cultural activities. Most studies have associated 40–80 minutes of outdoor time with reduced myopia incidence. There is also weak evidence linking increased outdoor exposure with reduced progression of myopia.[39] This has led to the introduction of school-based interventions to promote outdoor activity in children in several countries such as Taiwan, Singapore and China.

Implementation of these measures may, however, be challenging during COVID when the entire generation of children have been simultaneously exposed to the influence of cumulative, well-proven risk factors for myopia. Some measures such as frequent breaks from near work and limiting recreational screen time may be advocated. Several tracking devices such as Fitsight[40] and Clouclip[41] are being explored to identify the near-work behaviors in school children. Ophthalmologists can play a critical role by encouraging parents to inculcate healthy lifestyle habits in children and sensitizing the health policy planning bodies to modify the academic curriculum accordingly.

Treatment modalities for myopia

With the growing body of evidence demonstrating that its progression can be slowed in the critical period of growing years, myopia control is becoming increasingly popular in clinical practice. The available treatment modalities that have been shown to attenuate the progression curve in myopia are pharmacological therapy using topical atropine and optical interventions such as bifocal spectacles, progressive addition spectacles, bifocal and multifocal contact lenses, and orthokeratology (OK).

Pharmacological modalities

Literature is replete with evidence supporting the use of topical atropine to arrest the progression of myopia. Considering the safety profile and the ease of administration, atropine has recently evolved as one of the most accepted interventions for myopia in many countries, including India.

Topical atropine:

Atropine is an anticholinergic agent that exerts its pharmacological effect by blocking the parasympathetic acetylcholine muscarinic receptors located on the sphincter pupillae muscle causing mydriasis and cycloplegia. It has long been debated whether the anti-myopia effect of atropine is due to the accommodative mechanisms or some biochemical reactions that remain unclear. The earlier accommodative theories that stemmed from the concept that an increased accommodative demand led to the progression of myopia were rejected when the protective effect of atropine was demonstrated even in animals that had no accommodative mechanism. The non-accommodative theory is based on the local retinal effect and the biochemical changes brought about by its action on the muscarinic receptors that affect the scleral matrix and decelerate scleral growth.[42] Other less popular theory states that the protective effect of atropine is due to the enhanced exposure to ultraviolet spectrum aided by pupillary dilatation leading to downregulation of the inflammatory processes and decreased axial growth, but lack any strong evidence. Although there is no consensus regarding the exact mechanism of action of atropine, its direct and indirect effect on the retina leading to a decreased scleral stretch which halts the axial elongation remains the most accepted theory as of now.[42,43]

The role of atropine in anti-myopia therapy is being explored since the late 1800s, but its use was limited by the debilitating photophobia and near-vision impairment. The interest in the atropine therapy revived after the landmark trial of Atropine in the Treatment of Myopia 1 (ATOM 1) that analyzed the safety and efficacy of 1% topical atropine once a day in 400 Singaporean children aged 6–12 years with refractive error ranging from − 1D to − 6D. A significantly less spherical equivalent progression (SE) and axial length elongation (AL) was noted in the treatment group at the end of 2 years.[44] After the washout period of 1 year, the rebound effect was most marked in the atropine treated group than the placebo. Overall, the atropine treated group fared better than the placebo group in terms of myopia progression at 3 years. However, side effects such as blurring of vision, glare, and allergy were reported.[45] This led to the second landmark trial Atropine in the Treatment of Myopia 2 (ATOM 2) by the same group that was designed to study the efficacy and side effect profile of low doses of atropine in myopia in 400 children of Asian ethnicity with ≥−2D refractive error and who were randomized to receive 0.01%, 0.1%, 0.5% atropine eye drops once nightly for 2 years (Phase 1). This study demonstrated a dose-dependent response to atropine therapy in this phase, with 63%, 58%, and 50% patients showing minimal myopia progression (<0.5D) in the 0.5%, 0.1%, and 0.01% groups, respectively. After the discontinuation of therapy (phase 2: washout phase), a minimal rebound effect was noted with the lowest concentration of 0.01% atropine compared to other higher doses. The lower myopia progression in 0.01% group persisted in phase 3 (retreatment of children who progressed >0.5D in any group with 0.01% atropine) with overall myopia progression and axial length elongation (−1.38 ± 0.98D; 0.75 ± 0.48 mm) being significantly less in this group than 0.1% (−1.83 ± 1.16D; 0.85 ± 0.53 mm) and 0.5% (−1.98 ± 1.10D; 0.87 ± 0.49 mm). Atropine 0.01% was also associated with minimal change in pupil size (0.8 mm) and accommodation (2–3D), thus making it the most effective concentration in myopia. However, this study lacked a control group, and what remains contradictory is despite the minimal change in SE, significant AL elongation continued in the 0.01% group.[46]

Henceforth, many studies have been conducted evaluating the efficacy of various low concentrations of topical atropine. The Low-concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression (LAMP) study from Hong Kong was the first placebo-controlled trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of 0.05%, 0.025%, and 0.01% topical atropine in 438 children in the age group of 4–12 years with progressive myopia ≥1D. Phase 1 (1st year) and phase 2 (2nd year) of this study showed a concentration-dependent response with higher efficacy in the 0.05% group for controlling axial lengthening and myopic shifts. All the concentrations were well tolerated. The 0.01% atropine showed better efficacy in the second year of therapy but yet again was found to have minimal effect on AL elongation.[47,48] Rebound effect in phase 3 of LAMP is yet to be reported, which might influence the outcomes. Although the change in SE and AL elongation do not remain parallel and have a ratio of 0.7–0.8, the LAMP study confirmed that the anti-myopia effect of low-concentration atropine was mediated mainly via reduction of AL elongation.[49]

Recently, a multicentric RCT from India (Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia in India I-ATOM) reported a higher efficacy of 0.01% atropine in the Indian cohort with 54% lesser progression of mean SE in the atropine group (0.16 ± 0.4D) versus placebo (0.35 ± 0.4D) (P = 0.02) at 1 year.[50] The better response has been attributed to less rapid myopia progression or low environmental risk factors in Indian children compared to their Chinese counterparts. Meanwhile, encouraging results are being reported in other ethnic groups from Europe,[51,52,53] the United States,[54] and India[50] with 0.01% atropine. This product has become commercially available in Singapore, Malaysia, India, and various other countries in Asia and Europe.

Table 1 summarizes the results of various studies demonstrating the efficacy of 0.01% atropine in myopia progression. Therefore, although greater response is seen with higher doses of topical atropine, rebound effect and side effect profile are better for 0.01% atropine. Poor or no response to atropine has been demonstrated in a small fraction of myopic children. In ATOM 2, 4.3%, 6.4%, and 9.3% children in the 0.5%, 0.1%, and 0.01% groups, respectively, progressed by ≥−1.5D in the initial 2-years of therapy. This shows the percentage of poor responders on ATOM 2 study. This subset of poor responders are generally younger, have more baseline myopia, and have myopic parents.[55] Rapid myopia progression (>−1D) was noted in none of the patients in the atropine treatment group and in only 9% of patients in the placebo group in the I-ATOM study, which further confirms that Indian children are low-progressing cohort.[50] There is also evidence of change in treatment efficacy of atropine over time.

Table 1.

Summary of the results of 0.01% atropine in myopia progression reported in various studies

| Title, Author, and Study design | Mean Change in SE (D) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Baseline | 1 year | 2 years | |||

| ATOM2 Chia et al., 2012[43] RCT (400); 3 arms- 0.5%, 0.1%, 0.01% (84) Singapore; 6-12y (9.5y) F/U- with therapy (2y) f/b Phase 3 washout phase (1y) f/b restarting therapy (2y) |

Cases= −4.50±1.5 Control- NA |

Cases= −0.43±0.52 Control- NA |

Cases= −0.49±0.63 Control- NA |

||

| LAMP (Phase 1); Yam et al., 2018[47] RCT (438); 4 arms- 0.05%, 0.025%, 0.01% (110), control (111) Hong Kong (China); 4-12y (8.23y- 0.01% grp; 8.42- control grp), F/U- 1y |

Cases=−3.77±1.85 Control=−3.85±1.95 |

Case=−0.59±0.61 Control=−0.81±0.53 |

- | ||

| LAMP (Phase 2); Yam et al., 2019[48] RCT (383); 4 arms- 0.05%, 0.025%, 0.01% (91), switch-over grp (control from 1st year shifted to 0.05% in 2nd year) Hong Kong (China); 4-12y (8.35y- 0.01% grp) F/U- 2y |

Cases= −3.99±1.94 Control=NA |

Cases= −0.64±0.56 Control=NA |

Cases=−1.12±0.85 Control=NA |

||

| Fu et al., 2020[68] Cohort (400); 3 arms- 0.02%, 0.01% (119), control (100); 23 subjects in 0.01% grp and 20 subjects in control group did not complete the follow-up. Zengzhou (China); 6-14y (9.3y- 0.01% grp; 9.5- control) F/U- 1y |

Cases=−2.7±1.64 Control=−2.68±1.42 |

Cases=−0.47±0.45 Control=−0.7±0.6 |

- ------------ | ||

| Moon et al., 2019 Retrospective (285); 3 arms- 0.05%, 0.025% and 0.01% (89) >Korea; 5-14y (8y- 0.01%); F/U- 1y |

Cases=−3.84±2.47 Control- NA |

Reported rate of refractive growth for 0.01% grp- −0.07±0.072/month |

- ------------ | ||

| Moon et al., 2019 Diaz-Llopis et al., 2018[52] Retrospective (285); 3 arms- 0.05%, 0.025% and 0.01% (89) Prospective study (200) with cases (0.01%) and control Korea; 5-14y (8y- 0.01%); F/U- 1y Spain; 9-12y (10.4y- 0.01%; 10.1y- control) |

Cases= −3.84±2.47 Control- NA Cases= −1.1±0.5 Control= −1.2±0.4 Reported annual progression rate at 5 years F/U- Cases=−0.14±0.35 Control=−0.65±0.54 |

Cases=−0.84 Control- NA |

- ------------ - -----NA---- |

||

| Sacchi et al., 2019[53] Retrospective; 0.01% grp (52) and control (50) Milan, Italy; 5-16y (9.7y- 0.01% grp; 12.1y- control grp) | Cases= −3±2.23 Control= −2.63±2.68 |

Cases=−0.54±0.61 Control=−1.09±0.64 |

|||

| Joachimsen et al., 2019[51] Cross-sectional observational of 56 children of European ancestry using 0.01% atropine Germany; 6-17y (11) |

Cases= −3.85±1.88 | Cases=−0.4±0.49 | ------NA---- | ||

| Clark et al., 2015[54] Retrospective case control study (60); 32 cases using 0.01% atropine and 28 control California, USA; 6-15y (10.2y in both groups) |

Cases= −2±1.6 Control= −2±1.5 |

Cases= −0.1±0.6 Control= −0.6±0.4 |

------NA---- | ||

| Larkin GL et al., 2019 Multicentric retrospective case-control study (198); 100 cases and 98 control USA; 6-15y (9y in both groups) |

Cases=−3.1±1.9 Control=−2.8±1.6 |

Cases= −0.2±0.8 Control= −0.6±0.4 |

Cases=−0.3±1.1 Control=−1.2±0.7 |

||

| I-ATOM Saxena R et al. 2020[50] Multicentric randomized placebo-controlled double blinded trial India; (6-14 yrs) (10.58y- 0.01% grp; 10.8y- placebo) |

Cases=−3.45±1.3 Control=−3.68±1.3 |

Cases=−3.54±1.48 Control=−4.06±1.47 |

------------ | ||

|

| |||||

| Title, Author, and Study design | Mean Change in AL (mm) | Side effects related to atropine use | Comments | ||

|

| |||||

| Baseline | 1 year | 2 years | |||

|

| |||||

| ATOM2 Chia et al., 2012[43] RCT (400); 3 arms- 0.5%, 0.1%, 0.01% (84) Singapore; 6-12y (9.5y) F/U- with therapy (2y) f/b Phase 3 washout phase (1y) f/b restarting therapy (2y) |

Cases=25.1±1 Control- NA |

Cases=0.24±0.19 Control- NA |

Cases- −0.41±0.32 Control- NA |

Irritation (1), blur (1) | -Reported 0.01% as the optimal concentration with minimal side effects and rebound effect - Did not have a control group and used the historical control from ATOM 1 |

| LAMP (Phase 1); Yam et al., 2018[47] RCT (438); 4 arms- 0.05%, 0.025%, 0.01% (110), control (111) Hong Kong (China); 4-12y (8.23y- 0.01% grp; 8.42- control grp), F/U- 1y |

Cases=24.7±0.99 Control- 24.82±0.97 |

Cases=0.36±0.29 Control- 0.41±0.22 |

- ------------ | Allergic conjunctivitis | -Reported 0.05% as the most effective concentration; - Phase 3 under trial; this will give an idea about the rebound effect and long term effect of atropin |

| LAMP (Phase 2); Yam et al., 2019[48] RCT (383); 4 arms- 0.05%, 0.025%, 0.01% (91), switch-over grp (control from 1st year shifted to 0.05% in 2nd year) Hong Kong (China); 4-12y (8.35y- 0.01% grp) F/U- 2y |

Cases=24.78±1.02 Control=NA |

Cases=0.35±0.24 Control=NA |

Cases=0.59±0.38 Control=NA |

Need for photochromatic glasses (31), progressive glasses (2), photophobia with photochromatic glasses (1), photophobia without photochromatic glasses (5), allergic conjunctivitis (11) | |

| Fu et al., 2020[68] Cohort (400); 3 arms- 0.02%, 0.01% (119), control (100); 23 subjects in 0.01% grp and 20 subjects in control group did not complete the follow-up. Zengzhou (China); 6-14y (9.3y- 0.01% grp; 9.5- control) F/U- 1y |

Cases=24.58±0.74 Control=24.55±0.71 |

Cases=0.37±0.22 Control=0.46±0.35 |

------------- | Photophobia in bright sunlight (24%), mild near vision blur for initial 2-4 weeks (4.9%), allergy with itching and eyelid swelling (1) | -Reported 0.02% has better efficacy than 0.01% with similar side effect profile. - Not a RCT; RCT however was done for the treatment arm between 0.02% and 0.01% group; |

| Moon et al., 2019 Retrospective (285); 3 arms- 0.05%, 0.025% and 0.01% (89) Korea; 5-14y (8y- 0.01%); F/U- 1y |

Cases=24.86±1.22 Control- NA |

Cases=0.44±0.232 Control- NA |

- ------------ | None | - Atropin acts in a dose-dependent manner - Recommended atropine concentration >0.01% in Koreans - Retrospective study with lack of control |

| Moon et al., 2019 Diaz-Llopis et al., 2018[52] Retrospective (285); 3 arms- 0.05%, 0.025% and 0.01% (89) Prospective study (200) with cases (0.01%) and control Korea; 5-14y (8y- 0.01%); F/U- 1y Spain; 9-12y (10.4y- 0.01%; 10.1y- control) |

Cases=24.86±1.22 Control- NA - -----NA---- |

Cases=0.44±0.232 Control- NA - -----NA---- |

- ------------ - -----NA---- |

None Not a RCT Included low myopia <−2D Data on AL, NPA, pupil size missing |

- Atropin acts in a dose-dependent manner - Recommended atropine concentration >0.01% in Koreans - Retrospective study with lack of control |

| Sacchi et al., 2019[53] Retrospective; 0.01% grp (52) and control (50) Milan, Italy; 5-16y (9.7y- 0.01% grp; 12.1y- control grp) | - -----NA---- | - -----NA---- | - -----NA---- | NA | Photophobia (5) |

| Joachimsen et al., 2019[51] Cross-sectional observational of 56 children of European ancestry using 0.01% atropine Germany; 6-17y (11) |

------NA---- | ------NA---- | ------NA---- | None | -Small sample size - Control NA - Data on axial length NA |

| Clark et al., 2015[54] Retrospective case control study (60); 32 cases using 0.01% atropine and 28 control California, USA; 6-15y (10.2y in both groups) |

------NA---- | ------NA---- | ------NA---- | Intermittent light sensitivity (2), intermittent blurring of vision (1) | -Reported efficacy of 0.01%atropin - Small sample size with no data available for AL, pupil size, and NPA - Based on non-cycloplegic refraction |

| Larkin GL et al., 2019 Multicentric retrospective case-control study (198); 100 cases and 98 control USA; 6-15y (9y in both groups) |

------NA---- | ------NA---- | ------NA---- | Mydriasis and sensitivity to light (1%), allergic conjunctivitis (3%) | - Reported efficacy of 0.01%atropin - No data available for AL, pupil size, and NPA - Cycloplegic refraction was done in all patients |

| I-ATOM Saxena R et al. 2020[50] Multicentric randomized placebo-controlled double blinded trial India; (6-14 yrs) (10.58y- 0.01% grp; 10.8y- placebo) |

Cases=24.6±1.02 Control=24.7±0.8 |

Cases=24.82±1.03 Control=24.98±0.88 |

------------- | None | - Multicentric RCT that reports a significant decrease in SE progression with 0.01% atropine without significant change in AL elongation. |

Other agents

The role of a few other anti-muscarinic agents has also been studied. Pirenzepine, a relatively selective M1/M4 receptor antagonist, depicted promising results with minimal side effects in terms of a lower degree of mydriasis and cycloplegia as compared to topical atropine.[56,57] However, recently, the trials for this drug have been suspended due to its lower efficacy and twice-daily dosing requirement. Tropicamide and scopolamine are other less commonly explored anticholinergic agents which have not found much acceptance due to overlapping side effect profiles and lack of follow-up studies.[58] 7-methylxanthine (7MX), an adenosine antagonist, is a metabolite found in caffeine. Its role in slowing myopia progression is based on the stabilizing effect on the collagen fibrils of the posterior sclera.[59] This drug is approved for myopia management in Denmark.[60] Timolol, a beta-adrenergic receptor blocker, was also tried but failed to demonstrate any significant benefit in decreasing myopia progression.[61]

Optical modalities

The optical interventions are designed to reduce the accommodation lag and/or central and peripheral hyperopic defocus, which are considered to be important factors driving myopia progression.

Spectacles [Table 2]

Table 2.

Summary of the results of various studies evaluating the role of spectacles in myopia

| Titles, Authors and Study design | Methodology | Baseline refractive error (SER/D) | Change/Progression of refractive error (SER/D) | Baseline Axial length (mm) | Change in Axial elongation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studying the effect of under-correction on the progression of myopia, Adler D et al., 2006.[63] Prospective, randomized clinical trial, UK. n=48 Duration- 18 months. |

Control (n=23): fully corrected spectacles Treatment (n=25): under-corrected- blurred with+0.5D. | C=−2.82±1.06 Under-corrected=−2.95±1.25 |

C=0.82±0.10 Under-corrected=0.99±0.09 Worsening of myopia progression by 20.7% in the under-corrected group. |

Not evaluated | Not evaluated |

| Spectacle lenses designed to reduce the progression of myopia, Sankaridurg P, et al., 2010.[64] Prospective, randomized, double-blinded study clinical trial, China. n=210 Duration- 24 months. |

Control (n=50): single vision spectacles. Treatment: Novel spectacle design to reduce peripheral hyperopic defocus - type I (n=50), type II (n=60), type III (n=50). | C=−1.87±0.68 Type I=−1.82±0.62 Type II=−1.81±0.67 Type III=−1.82±0.66 |

Age: 6-12 yrs C=−0.90±0.48 Type I=−0.85±0.45 Type II=−0.92±0.38 Type III=−0.75±0.43 Age: 13-16 yrs C=−0.44±0.38 Type I=−0.64±0.31 Type II=−0.50±0.51 Type III=−0.49±0.31 No statistically significant change in progression of myopia. |

C=24.55±0.77 Type I=24.33±0.66 Type II=24.47±0.70 Type III=24.51±0.63 |

Age: 6-12 yrs C=0.43±0.20 Type I=0.40±0.21 Type II=0.39±0.18 Type III=0.36±0.17 Age: C=0.15±0.11 Type I=0.21±0.13 Type II=0.24±0.16 Type III=0.21±0.12 No statistically significant difference in axial elongation. |

| Effect of Bifocal and Prismatic Bifocal Spectacles on Myopia Progression in Children, Cheng D et al., 2014.[65] Prospective, randomized clinical trial, Canada. n=135 Duration- 36 months. |

Control (n=41): Single-vision lenses. Group I (n=48): +1.50D executive bifocals Group II (n=46): +1.50D executive bifocals with 3-Δ base-in prism in the near segment of each lens. |

C=−2.92±0.19 Group I=−3.03±0.16 Group II=−3.27±0.16 |

C=−2.06±0.13 Group I=−1.25±0.10 Group II=−1.01±0.13 Decrease in myopia progression in Group I was 51% and Group II was 39.3%. |

Not mentioned | C=0.82±0.05 Group I=0.57±0.07 Group II=0.54±0.06 Decrease in axial elongation Group I by 34.1% and Group II by 30.5%. |

| Correction of Myopia Evaluation Trial (COMET) study, Gwiazda J et al., 2003. Randomized clinical trial, USA. n=469 Duration- 36 months. |

Control (n=234): Single Vision lenses Treatment (n=235): PALs with a +2.00 addition. |

C=−2.37±0.84 PALs=−2.40±0.75 |

C=−1.48±0.06 PALs=−1.28±0.06 Slowing of myopia progression by 13.5% in PALs group. |

C=24.14±0.72 PALs=24.10±0.72 |

C=0.75±0.02 PALs=0.64±0.02 Slowing of axial elongation by 14.6% in the PALs group. |

|

COMET, 5 years results. Gwiazda J et al., 2005.[66] Randomized clinical trial, USA. COMET cohort followed up for 5 years. |

Control (n=234): Single Vision lenses. Treatment (n=235): PALs with a+2.00 addition. |

C=−2.37±0.84 PALs=−2.40±0.75 |

C=−2.10±0.09 PALs=−1.97±0.09 The difference between the two groups was less than at end of 3 years and not statistically significant. |

C=24.14±0.72 PALs=24.10±0.72 |

Not mentioned. |

| The effectiveness of progressive addition lenses on the progression of myopia in Chinese children, Yang Z et al., 2009.[72] Randomized clinical trial, Hong Kong. n=178 (149 completed) Duration- 24 months. |

Control (n=75): Single vision spectacles. Treatment (n=74): PAL with a +1.50 addition. |

C=−1.78±0.68 PALs=−1.60±0.63 |

C=−1.24±0.56 PALs=−1.50±0.67 Slowing of myopia progression by 17.3% in the PALs group. |

Vitreous chamber depth was assessed instead of axial length C=17.00±0.88 mm PALs=16.81±0.61 |

C=0.70±0.40 PALs=0.59±0.24 Slowing of eye elongation by 15.7% in PALs group. |

| Defocus Incorporated Multiple Segments (DIMS) spectacle lenses slow myopia progression, Lam CSY et al., 2017.[69] Randomized clinical trial, Hong Kong. n=183 (160 completed) Duration- 24 months. |

Control (n=90, 81 completed): Single vision spectacles. DIMS (n=93, 79 completed). DIMS lens incorporated multiple segments with myopic defocus of +3.50D. | C=−2.76±0.96 DIMS=−2.97±0.97 |

C=−0.93±0.06 DIMS=−0.38±0.06 Slowing of myopia progression by 52% in DIMS group. |

C=24.60±0.83 DIMS=24.70±0.82 |

C=0.53±0.03 DIMS=0.21±0.02 Slowing of axial elongation in DIMS group by 62%. |

| Myopia control with positively aspherized progressive addition lenses, Hasebe S et al., 2014.[68] Randomized clinical trial, China/Japan. n=197 (169 completed) Duration- 24 months. |

Control (n=60): Single vison spectacles. Group II (n=58): PA-PALs with +1.0 D addition Group III (n=51): PA-PALs with +1.5 D addition. |

C=−2.55±0.96 Group II=−2.52±1.01 Group III=−2.80±1.02 |

C=−1.39±0.09 Group II=−1.20±0.11 Group III=−1.12±0.11 Slowing of myopia progression by 20% in Group III was noted. |

C=24.64±0.73 Group II=24.56±0.90 Group III=24.71±1.02 |

C=0.69 Group II=0.63 Group III=0.60 Slowing of axial elongation by 8% in Group II and by 12% in Group III. |

Prescription of under-corrected spectacles in myopia was a popular strategy earlier. Based on the rationale that it reduces the accommodative demand at near and therefore the blur that drives the accommodative response, this practice lost favor after studies demonstrated that it can worsen myopia rather than halting its progression.[62,63]

Fully corrected single vision spectacles induce relative peripheral hyperopia; therefore, single vision peripheral defocus spectacles were designed. However, no apparent benefit could be demonstrated.[64]

Bifocal designs aimed to reduce the accommodative lag during extended near tasks have shown some benefit. Cheng et al.,[65] in a randomized control trial comparing the efficacy of single vision lenses, +1.50D executive bifocals, and + 1.50D executive bifocals with 3-D base-in prism in the near segment in 135 Chinese–Canadian myopic children, reported significantly lower myopia progression in bifocal groups after 3 years. They observed greater efficacy of prismatic bifocals in children with higher accommodation lag.

Multifocal spectacles with progressive addition lenses (PALs) are aimed to reduce both accommodation lag and peripheral hyperopic defocus. Correction of Myopia Evaluation Trial (COMET) (2006), a prospective multicentric clinical trial comparing the 5-year efficacy of PAL with + 2D add versus single vision lenses, found that PALs were not clinically effective at slowing myopia progression, with a difference of only 0.13D noted between the two groups.[66] As per the meta-analysis by Shi-Ming Li et al.[67] in 2011, PALs slowed myopic progression by 0.25D/year as compared to single vision lenses with greater benefit demonstrated in Asians, children with higher baseline myopia, and with rapid progression. Maximum benefit with PALs has been noted in the first year of therapy with virtually no effect in the second year.[69]

A recent double-masked randomized controlled trial (RCT) from Hong Kong (2020) used a novel Defocus Incorporated Multiple Segments (DIMS) spectacles with a central 9-mm zone for distance viewing and multiple segments of +3.5D defocus surrounding the central zone. This lens was designed to provide clear central vision and induce myopic defocus in the peripheral retina. Around 52% less myopia progression and 62% less axial elongation was noted with DIMS than with single vision lenses with no progression in 22% of children using DIMS.[70]

Among the new spectacle designs, MyoVision™ spectacle lens by Zeiss has become available in Canada,[71] and spectacles using micro-lens segments are being developed in Hong Kong in collaboration with HOYA.[72] However, there still exists some ambiguity in the use of PALs as larger RCTs conducted on a Chinese cohort have failed to demonstrate any significant benefit.[72,73,74] Table 2 summarizes the results of various studies evaluating the role of spectacles in myopia.

Contact lenses [Table 3]

Table 3.

Summary of outcomes of various studies evaluating the role of multifocal contact lens in myopia

| Title, Authors and study design | Methodology | Baseline refractive error (SER/D) | Change/Progression in SER (D) | Baseline Axial length (mm) | Change in axial elongation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease in rate of myopia progression with a contact lens designed to reduce relative peripheral hyperopia, Sankaridurg P et al., 2011.[83] Prospective randomized clinical trial, n=85 Duration- 1 year. |

Control group (n=40): Single vision spectacles. Treatment group (n=45): Novel Contact lens. To be worn at least 8 h/day, 5 days/week, replaced monthly. |

C=−1.99±0.62 CL=−2.24±0.79 |

C=0.84±0.47 CL=0.54±0.37 Slowing of myopia progression by 35.7% in novel contact lens group. |

C=24.57±0.93 CL=24.57±0.77 |

C=0.39±0.19 CL=0.24±0.17 Slowing of axial elongation by 38.5% in novel contact lens group. |

| Multifocal contact lens myopia control, Walline JJ et al., 2013.[79] Historic controls, USA. n=64 Duration- 2 years. |

Control group (n=32): Single vision CL. Treatment group (n=32): Multifocal CL Worn daily, replaced monthly. |

C=−2.35±1.05 MF=2.24±1.02 |

C=1.03±0.06 MF=0.51±0.06 Slowing of myopia progression by 50.5% in multifocal contact lens group. |

C=24.34±0.89 MF=24.27±0.96 |

C=0.41±0.03 MF=0.29±0.03 Slowing of axial elongation by 29.3% in multifocal contact lens group. |

| Effect of low-addition soft contact lenses with decentered optical design on myopia progression in children, Fujikado T et al., 2014.[80] Randomized, cross over study, Japan. n=24 Duration- 1 year. |

Control group (n=13): Monofocal design CL. Treatment group (n=11): New low addition progressive design CL. To be worn 6 h/day, 4 days/week, and replaced daily. |

C=−2.64±0.99 New-CL=−2.56±0.87 |

C=−0.84±0.42 D New-CL=−0.62±0.43 Slowing of myopia progression by 26.2%. |

C=24.97±0.62 New-CL=24.74±0.73 |

C=0.20±0.09 New-CL=0.15±0.07 Slowing of axial elongation by 25%. |

| Defocus Incorporated Soft Contact (DISC) lens slows myopia progression, Lam CSY et al., 2014.[81] Randomized clinical trial, Hong Kong. n=128 Duration- 2 years. |

Control group (n=65):Single vision CL. Treatment group (n=63):Defocus Incorporated Soft CL. To be worn for at least 5-10 h/day and spectacle correction to be used after that. CLs replaced at 6 months. |

C=−2.80±1.03 DISC=−2.90±1.05 |

C=DISC=Slowing of myopia progression by 25.3%. | C=24.62±0.79 DISC=24.69±0.74 |

C=0.37±0.24 DISC=0.25±0.23 Slowing of axial elongation by 32.4% |

| MiSight Assessment Study Spain (MASS), Ruiz-Pomeda A et al., 2018.[92] Randomized clinical trial, Spain. n=89 (74 completed) Duration- 2 years. |

Control (n=33): Single vision CL. Treatment group (n=41): MiSight CL- Daily disposable to be worn for not more than 15 h/day, at least 6 days/week. |

C=−1.75±0.94 MiSight=−2.16±0.94 |

Median (IQR) C=0.74 (0.53-0.95) MiSight=0.45 (0.27-0.64) Slowing of myopia progression by 39.3% in MiSight group. |

C=24.00±0.86 MiSight=24.09±0.55 |

Median (IQR) C=0.44 (0.54-0.35) MiSight=0.28 (0.37-0.20) Slowing of axial elongation in the MiSight group by 36.4%. |

| Effect of High Add Power, Medium Add Power, or Single-Vision Contact Lenses on Myopia Progression in Children (BLINK), Walline JJ, 2020.[85] Randomized clinical trial, Texas and Ohio. n=292 (287 completed) Duration- 3 years. |

Control (n=97): Single vision contact lens Medium power add (n=98): multifocal with +1.5D add High power add (n=97): multifocal with +2.5D add. To wear contact lenses during the day for as long as the participant is comfortable. |

C=−2.46±0.97 Medium=−2.43±1.11 High=−2.28±0.90 |

Median (IQR) C=−1.01 (−1.15 to−0.87) Medium=−0.85 (−0.99 to−0.70) High=−0.56 (−0.70 to−0.41) Slowing of myopia progression by 43% in multifocal contact lens groups. |

C=24.45±0.83 Medium=24.57±0.85 High=24.43±0.74 |

Median (IQR) C=0.62 (0.56-0.69) Medium=0.55 (0.49-0.62) High=0.39 (0.32-0.46) Slowing of axial elongation by 36% in multifocal contact lens groups. |

Contact lenses provide better cosmesis with good image quality,[73,74,75] especially in high myopia, and reduce the degree of aniseikonia in patients with anisometropia.[76] There is no substantial evidence supporting the use of conventional soft contact lenses or rigid gas permeable lenses in myopia.

Soft multifocal contact lenses with center-distance optics, commercially available for presbyopia, have gained off-label use in myopia. Center-distance multifocal contact lenses increase plus power in the lens periphery by using aspheric optics or concentric rings of additional plus that can negate the hyperopic blur without affecting the distance vision.[77] Several randomized control trials conducted to compare the rate of myopia progression between multifocal contact lenses and single vision contact lenses concluded that myopia progression was attenuated by 37%–38% in the multifocal contact lens group and there was a significant reduction in axial elongation in these subjects.[78,79,80,81,82,83] These lenses should be fitted with a maximum plus to maximal visual acuity philosophy to avoid over-minusing the patients and thereby potentially reducing the myopia control effect. Multifocal soft contact lens wear is recommended for 5–8 h as reduced efficacy is noted with a lesser duration of use.

Several novel soft multifocal contact lenses specific for myopia are being designed. Defocus incorporated soft contact lens (DISC), a 2-year randomized clinical trial, showed that daily wearing of DISC lens (incorporated concentric rings which provided the addition of +2.5D, alternating with normal distance correction) led to 25% less myopia progression and 31% less axial elongation than SVL in Hong Kong Chinese schoolchildren.[81] A prospective longitudinal non-randomized study reported comparable effects in preventing myopia progression between OK and soft radial refractive contact lens (SRRG), with axial length increase being 27% and 38% less, respectively.[82] Two daily disposable multifocal soft contact lenses, MiSight® 1 day (CooperVision) and NaturalVue® (Visioneering Technologies), have recently been approved in some countries for anti-myopia therapy. The MiSight® soft multifocal contact lens has a dual-focus, center-distance concentric ring that has become available in the USA, Canada, Europe, Australia, and some other countries. The lens has a large central correction area of 3.36 mm surrounded by concentric zones of alternating distance and near powers which together produce two focal planes. The optical power of the correction zones corrects the refractive error, while the treatment zones produce 2.00D of simultaneous myopic retinal defocus during both distance and near viewing. A multicentric, randomized controlled but non-masked trial reported a 59% reduction in mean cycloplegic spherical equivalent refractive error and a 52% reduction in AL elongation at 3 years with the MiSight lens compared with spherical contact lens.[84] These lenses are currently indicated in myopes aged 8–12 years with − 0.75D to − 4D of myopia and have a far greater risk of microbial keratitis. The Bifocal Lenses In Nearsighted Kids (BLINK) study was a randomized control trial that compared the effect of Biofinity single vision contact lens versus Biofinity multifocal contact lens with high and medium add (+2.5D add and +1.50D add) in 7–11-years-old children reported 43% slower myopia progression in +2.5D group and concluded that +2.5D near add was effective in myopia control.[84] Table 3 summarizes the results of various studies evaluating the role of multifocal contact lenses in myopia.

In cases with astigmatism, Proclear® Toric Multifocal (CooperVision) may be considered.[86] Customization of contact lenses is an upcoming option that may be seen in coming years.

OK is the modality that taps the cornea reshaping potential of gas permeable lenses to treat refractive errors like myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism. In myopia, OK lenses act by flattening the central cornea and changing the peripheral refractive status from hyperopic to relative myopic defocus. The reshaping occurs due to overnight corneal epithelial cell redistribution while the contact lens is worn. This averts the need for use of correction during the day. The first-ever OK lens using PMMA was designed by George Jessen in the 1960s and marketed as “Orthofocus.” The reverse geometry designs and high oxygen permeability of today’s OK lenses have led to improved predictability and shown better response by retarding axial elongation by 32%–55% in several studies.[87] The Longitudinal Orthokeratology Research in Children (LORIC) study (2005), a 2-year pilot study from Hong Kong in 7–12-year-old myopes, noted that AL elongation was almost half in the OK group (0.29 ± 0.27 mm) than in the controls (0.54 ± 0.27 mm) (P = 0.012). They also observed that the benefit was more in higher myopes (>2D).[88] Later, in 2012, these findings were corroborated in the Retardation of Myopia in Orthokeratology (ROMIO) trial, a 2-year RCT conducted in children with − 0.5D to − 4D myopia, that reported a 43% reduction in axial elongation in the OK group (0.36 ± 0.24 mm) than the controls (0.63 ± 0.26 mm). Maximum effect was seen in the second year of therapy and younger myopic children (<9 years).[89] Promising results have also been documented using OK in high myopia (>−6D)[90] and myopia with moderate to high astigmatism (−3.5D)[91] in separate studies. OK is the only myopia treatment that allows myopic children to see clearly without the need for any correction during the day and is therefore preferable in children who are active in sports. A minimum of 8 h of OK lens wear is recommended for optimal results. The benefit is found to be maximum in the first 2 years of therapy and wanes off later. However, the dropout rates in these studies have been high. As per a recent review, OK lenses may be effective in slowing myopia progression, especially in younger children aged 6–8 years, but there remain concerns of risk of microbial keratitis.[78] Despite modest efficacy in myopia control with OK or multifocal soft contact lenses, the acceptance rate remains low in India due to concerns related to the cost of treatment, expertise needed for fitting these lenses, and risk of microbial keratitis. Table 4 summarizes the results of various studies evaluating the role of multifocal contact lenses in myopia.

Table 4.

Summary of outcomes of various studies evaluating the role of orthokeratology in myopia

| Title and Authors and Study design | Methodology | Baseline refractive error (Spherical Equivalent, D) | Refractive error change from baseline (Spherical Equivalent, D) | Axial length baseline (mm) | Axial length elongation from baseline (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Orthokeratology Research in Children (LORIC), Cho P et al., 2005.[88] Historic controls, n=78 Duration- 2 years |

Control group (n=35): Single vison spectacles Treatment group (n=43, 35 completed): ortho-k lenses- Overnight wear. |

C=−2.55±0.98 OK=−2.27±1.09 |

C=−1.20±0.61 OK=2.09±1.34 Reduction in SER by 80% in OK group. |

C=24.64±0.58 OK=24.50±0.71 |

C=0.54±0.27 OK=0.29±0.27 Slowing in axial elongation by 46%. |

| Retardation of Myopia in Orthokeratology (ROMIO), Cho P et al., 2012.[89] Randomized clinical trial, Hong Kong. n=102 Duration=2 years. |

Control group (n=51, 41 completed): Single vision spectacles Treatment group (n=51, 37 completed): ortho-K lenses- Overnight wear. |

C=−2.23±0.84 OK=−2.05±0.72 |

Not evaluated. Slowing of myopia progression by 43% in OK group. |

C=24.40±0.84 OK=24.48±0.71 |

C=0.63±0.26 OK=0.36±0.24 Slowing in axial elongation by 52%. |

| High Myopia-Partial Reduction Orthokeratology (HM-PRO), Charm J et al., 2013.[90] Randomized clinical trial, Hong Kong. n=52 Duration=2 years. |

Control group (n=26): Single vision spectacles. Treatment group (n=26): Partial Reduction-OK lenses: Overnight wear. |

C=Median−6.13D (range 5-8.3D) PR-OK=Median −6.5D (range 6-8.30D) |

Median reduction in the PR-OK group was 3.75D at 1 month follow-up with a median residual myopia of 2.75D. | C=25.93±0.54 PR-OK=26.02±0.57 |

C=0.51±0.32 PR-OK=0.19±0.21 Slowing in axial elongation by 63%. |

| Myopia control using Toric Orthokeratology (TO-SEE), Chen C et al., 2013.[91] Randomized clinical trial, Hong Kong. n=80 Duration=2 years. |

Control group (n=37, 23 completed): single vision spectacles Treatment group (n=43, 35 completed) Toric-OK, Overnight wear. | C=−2.04±1.09 OK=−2.46±1.32 |

In the OK group myopia reduced to 0.18±0.37 D at 6 months of follow-up. | C=24.18±1.00 OK=24.37±0.88 |

C=0.64±0.31 OK=0.31±0.27 Slowing in axial elongation by 63%. |

Combination therapy

As none of the available treatment options can completely stop myopia progression, there is a need to explore the role of combination therapy with modalities having different mechanisms of action. The preliminary results of two randomized trials[93,94] have been promising and shown better efficacy in slowing axial elongation (50% greater effect)[93] with combined treatment with OK lens and 0.01% atropine than with OK alone. Additionally, efforts are underway to explore contact lenses as drug-delivery devices for atropine or pirenzepine.[95] Another study is underway to evaluate the efficacy of 0.01% atropine with bifocal soft contact lens with +2.5D add.[96]

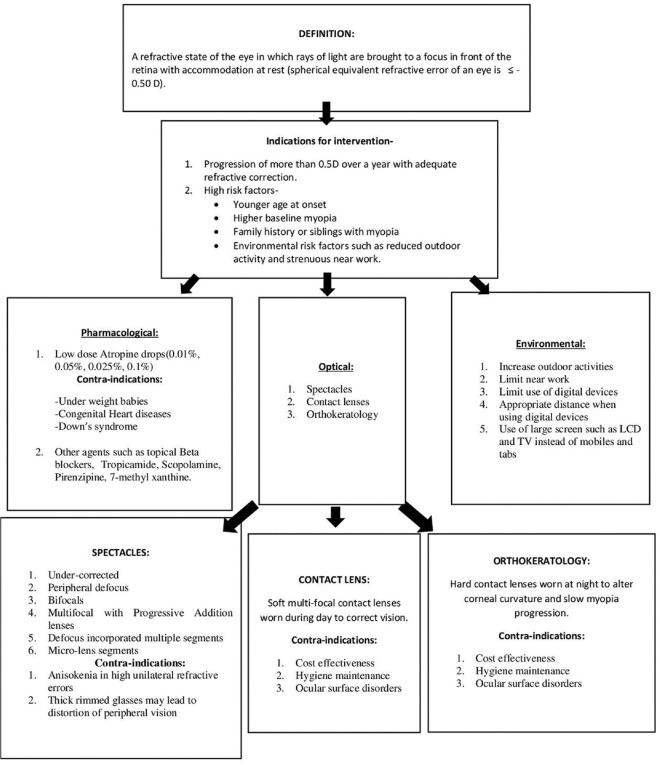

All these management options may slow the myopia progression but cannot halt it completely. (Fig 1 enlists various interventional modalities in childhood myopia.)

Figure 1.

Overview and various interventional modalities in childhood myopia

Conclusion

This article elaborates the relevant literature related to etiopathogenesis, risk factors, and the available treatment modalities of myopia. Despite ongoing research, the exact mechanism of onset and progression of myopia is yet to be determined. The mechanism of many treatment modalities in myopia and their role in high myopia is still obscure. Due to lack of any established clinical guidelines for myopia management, the best treatment strategy is to explore the modifiable risk factors, formulate preventive strategies, and possibly integrate them with the school vision screening programs. An informed choice of myopia management should be offered after explaining the expected outcomes and the risks of the therapy to the parents or guardians. “What treatment option?” and “for how long?” are some questions that the clinician must decide on a case-to-case basis after considering various factors such as age, baseline myopia, rate of progression, affordability, and safety. Future research and designing the preferred practice guidelines are imperative to contain this ongoing myopia epidemic.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, Jong M, Naidoo KS, Sankaridurg P, et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1036–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holden B, Sankaridurg P, Smith E, Aller T, Jong M, He M. Myopia, an underrated global challenge to vision:Where the current data takes us on myopia control. Eye. 2014;28:142–6. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mutti DO. Hereditary and environmental contributions to emmetropization and myopia. Optom Vis Sci. 2010;87:255–9. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181c95a24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naidoo KS, Leasher J, Bourne RR, Flaxman SR, Jonas JB, Keeffe J, et al. Global vision impairment and blindness due to uncorrected refractive error, 1990-2010. Optom Vis Sci Off Publ Am Acad Optom. 2016;93:227–34. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourne RR, Stevens GA, White RA, Smith JL, Flaxman SR, Price H, et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990-2010:A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e339–49. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70113-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin LL, Shih YF, Hsiao CK, Chen CJ. Prevalence of myopia in Taiwanese schoolchildren:1983 to 2000. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudnicka AR, Kapetanakis VV, Wathern AK, Logan NS, Gilmartin B, Whincup PH, et al. Global variations and time trends in the prevalence of childhood myopia, a systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis:Implications for aetiology and early prevention. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:882–90. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam CS, Goldschmidt E, Edwards MH. Prevalence of myopia in local and international schools in Hong Kong. Optom Vis Sci Off Publ Am Acad Optom. 2004;81:317–22. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000134905.98403.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kempen JH, Mitchell P, Lee KE, Tielsch JM, Broman AT, Taylor HR, et al. The prevalence of refractive errors among adults in the United States, Western Europe, and Australia. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 2004;122:495–505. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murthy GV, Gupta SK, Ellwein LB, Muñoz SR, Pokharel GP, Sanga L, et al. Refractive error in children in an urban population in New Delhi. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:623–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saxena R, Vashist P, Tandon R, Pandey RM, Bhardawaj A, Gupta V, et al. Incidence and progression of myopia and associated factors in urban school children in Delhi:The North India myopia study (NIM Study) PLoS One. 2017;12:e0189774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saxena R, Vashist P, Tandon R, Pandey RM, Bhardawaj A, Menon V, et al. Prevalence of myopia and its risk factors in urban school children in Delhi:The North India Myopia Study (NIM Study) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mutti DO, Hayes JR, Mitchell GL, Jones LA, Moeschberger ML, Cotter SA, et al. Refractive error, axial length, and relative peripheral refractive error before and after the onset of myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2510–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaeffel F, Feldkaemper M. Animal models in myopia research. Clin Exp Optom. 2015;98:507–17. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harder BC, Schlichtenbrede FC, von Baltz S, Jendritza W, Jendritza B, Jonas JB. Intravitreal bevacizumab for retinopathy of prematurity:Refractive error results. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:1119–24.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldkaemper M, Schaeffel F. An updated view on the role of dopamine in myopia. Exp Eye Res. 2013;114:106–19. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao Q, Liu Q, Ma P, Zhong X, Wu J, Ge J. Effects of direct intravitreal dopamine injections on the development of lid-suture induced myopia in rabbits. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:1329–35. doi: 10.1007/s00417-006-0254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao J, Liu S. Different roles of retinal dopamine in albino Guinea pig myopia. Neurosci Lett. 2017;639:94–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBrien NA, Jobling AI, Truong HT, Cottriall CL, Gentle A. Expression of muscarinic receptor subtypes in tree shrew ocular tissues and their regulation during the development of myopia. Mol Vis. 2009;15:464–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostrin LA, Frishman LJ, Glasser A. Effects of pirenzepine on pupil size and accommodation in rhesus monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3620–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian L, Zhao H, Li X, Yin J, Tang W, Chen P, et al. Pirenzepine inhibits myopia in guinea pig model by regulating the balance of MMP-2 and TIMP-2 expression and increased tyrosine hydroxylase levels. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;71:1373–8. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McBrien NA, Gentle A. Role of the sclera in the development and pathological complications of myopia. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:307–38. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nickla DL, Wallman J. The multifunctional choroid. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29:144–68. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zadnik K, Sinnott LT, Cotter SA, Jones-Jordan LA, Kleinstein RN, Manny RE, et al. Prediction of juvenile-onset myopia. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:683. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.0471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flitcroft DI, He M, Jonas JB, Jong M, Naidoo K, Ohno-Matsui K, et al. IMI –Defining and classifying myopia:A proposed set of standards for clinical and epidemiologic studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:M20–30. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-25957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price H, Allen PM, Radhakrishnan H, Calver R, Rae S, Theagarayan B, et al. The Cambridge anti-myopia study:Variables associated with myopia progression. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:1274–1283. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farbrother JE, Kirov G, Owen MJ, Guggenheim JA. Family aggregation of high myopia:Estimation of the sibling recurrence risk ratio. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2873–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, Moeschberger ML, Jones LA, Zadnik K. Parental myopia, near work, school achievement, and children's refractive error. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3633–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones-Jordan LA, Sinnott LT, Graham ND, Cotter SA, Kleinstein RN, Manny RE, et al. The contributions of near work and outdoor activity to the correlation between siblings in the Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Ethnicity and Refractive Error (CLEERE) study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:6333–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu LJ, Wang YX, You QS, Duan JL, Luo YX, Liu LJ, et al. Risk factors of myopic shift among primary school children in Beijing, China:A prospective study. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12:633–8. doi: 10.7150/ijms.12133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gifford KL, Richdale K, Kang P, Aller TA, Lam CS, Liu YM, et al. IMI –clinical management guidelines report. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:M184–203. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-25977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karuppiah V, Wong L, Tay V, Ge X, Kang L. School-based programme to address childhood myopia in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2021;62:63–8. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2019144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ip JM, Saw S-M, Rose KA, Morgan IG, Kifley A, Wang JJ, et al. Role of near work in myopia:Findings in a sample of Australian school children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2903–10. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganne P, Najeeb S, Chaitanya G, Sharma A, Krishnappa NC. Digital eye strain epidemic amid COVID-19 pandemic-A cross-sectional survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2021;28:285–92. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2020.1862243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jee D, Morgan IG, Kim EC. Inverse relationship between sleep duration and myopia. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 2016 May;94:e204–10. doi: 10.1111/aos.12776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nickla DL, Jordan K, Yang J, Totonelly K. Brief hyperopic defocus or form deprivation have varying effects on eye growth and ocular rhythms depending on the time-of-day of exposure. Exp Eye Res. 2017;161:132–42. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seet B, Wong TY, Tan DT, Saw SM, Balakrishnan V, Lee LK, et al. Myopia in Singapore:Taking a public health approach. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:521–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.5.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan IG, French AN, Ashby RS, Guo X, Ding X, He M, et al. The epidemics of myopia:Aetiology and prevention. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2018;62:134–49. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li S-M, Li H, Li S-Y, Liu L-R, Kang M-T, Wang Y-P, et al. Time outdoors and myopia progression over 2 years in Chinese children:The Anyang childhood eye study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:4734–40. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verkicharla PK, Ramamurthy D, Nguyen QD, Zhang X, Pu S-H, Malhotra R, et al. Development of the FitSight fitness tracker to increase time outdoors to prevent myopia. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2017;6:20. doi: 10.1167/tvst.6.3.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao Y, Lan W, Wen L, Li X, Pan L, Wang X, et al. An effectiveness study of a wearable device (Clouclip) intervention in unhealthy visual behaviors among school-age children:A pilot study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e17992. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McBrien NA, Stell WK, Carr B. How does atropine exert its anti-myopia effects? Ophthalmic Physiol Opt J Br Coll Ophthalmic Opt Optom. 2013;33:373–8. doi: 10.1111/opo.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chia A, Chua W-H, Wen L, Fong A, Goon YY, Tan D. Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia:Changes after stopping atropine 0.01%, 0.1% and 0.5% Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:451–7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chua W, Balakrishnan V, Tan D, Chan Y, Group AS. Efficacy results from the Atropine in the Treatment of Myopia (ATOM) study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3119. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tong L, Huang XL, Koh AL, Zhang X, Tan DT, Chua W-H. Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia:Effect on myopia progression after cessation of atropine. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:572–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chia A, Lu Q-S, Tan D. Five-year clinical trial on atropine for the treatment of myopia 2. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:391–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yam JC, Jiang Y, Tang SM, Law AK, Chan JJ, Wong E, et al. Low-Concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression (LAMP) study:A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of 0.05%, 0.025%, and 0.01% atropine eye drops in myopia control. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:113–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yam JC, Li FF, Zhang X, Tang SM, Yip BH, Kam KW, et al. Two-year clinical trial of the Low-Concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression (LAMP) study:Phase 2 report. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:910–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li F-F, Kam K-W, Zhang Y, Tang SM, Young A, Chen L-J, et al. Effects on ocular biometrics by 0.05%, 0.025%, and 0.01% atropine:Low-concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression (LAMP) study. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:1603–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saxena R, Dhiman R, Gupta V, Kumar P, Matalia J, Roy L, et al. Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia in India:Multicentric randomized trial. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:1367–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joachimsen L, Böhringer D, Gross NJ, Reich M, Stifter J, Reinhard T, et al. A pilot study on the efficacy and safety of 0.01% atropine in German schoolchildren with progressive myopia. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8:427–33. doi: 10.1007/s40123-019-0194-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diaz-Llopis M, Pinazo-Durán MD. Superdiluted atropine at 0.01% reduces progression in children and adolescents. A 5 year study of safety and effectiveness. Arch Soc Espanola Oftalmol. 2018;93:182–5. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sacchi M, Serafino M, Villani E, Tagliabue E, Luccarelli S, Bonsignore F, et al. Efficacy of atropine 0.01% for the treatment of childhood myopia in European patients. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 2019;97:e1136–40. doi: 10.1111/aos.14166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clark TY, Clark RA. Atropine 0.01% eyedrops significantly reduce the progression of childhood myopia. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther Off J Assoc Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2015;31:541–5. doi: 10.1089/jop.2015.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loh K-L, Lu Q, Tan D, Chia A. Risk factors for progressive myopia in the atropine therapy for myopia study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:945–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stone RA, Lin T, Laties AM. Muscarinic antagonist effects on experimental chick myopia. Exp Eye Res. 1991;52:755–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90027-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bartlett JD, Niemann K, Houde B, Allred T, Edmondson MJ, Crockett RS. A tolerability study of pirenzepine ophthalmic gel in myopic children. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther Off J Assoc Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2003;19:271–9. doi: 10.1089/108076803321908392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iribarren R. Tropicamide and myopia progression. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1103–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trier K, Olsen EB, Kobayashi T, Ribel-Madsen SM. Biochemical and ultrastructural changes in rabbit sclera after treatment with 7-methylxanthine, theobromine, acetazolamide, or L-ornithine. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:1370–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.12.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trier K, Munk Ribel-Madsen S, Cui D, Brøgger Christensen S. Systemic 7-methylxanthine in retarding axial eye growth and myopia progression:A 36-month pilot study. J Ocul Biol Dis Infor. 2008;1:85–93. doi: 10.1007/s12177-008-9013-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jensen H. Myopia progression in young school children. A prospective study of myopia progression and the effect of a trial with bifocal lenses and beta blocker eye drops. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1991:1–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chung K, Mohidin N, O'Leary DJ. Undercorrection of myopia enhances rather than inhibits myopia progression. Vision Res. 2002;42:2555–9. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adler D, Millodot M. The possible effect of undercorrection on myopic progression in children. Clin Exp Optom. 2006;89:315–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2006.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sankaridurg P, Donovan L, Varnas S, Ho A, Chen X, Martinez A, et al. Spectacle lenses designed to reduce progression of myopia:12-month results. Optom Vis Sci. 2010;87:631–41. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181ea19c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng D, Woo GC, Drobe B, Schmid KL. Effect of bifocal and prismatic bifocal spectacles on myopia progression in children:Three-year results of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:258–64. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.7623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gwiazda JE, Hyman L, Everett D, Norton T, Kurtz D, Manny R, et al. Five–year results from the correction of?myopia evaluation trial (COMET) Investigative Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1166. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li S-M, Ji Y-Z, Wu S-S, Zhan S-Y, Wang B, Liu L-R, et al. Multifocal versus single vision lenses intervention to slow progression of myopia in school-age children:A meta-analysis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56:451–60. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fu A, Stapleton F, Wei L, Wang W, Zhao B, Watt K, et al. Effect of low-dose atropine on myopia progression, pupil diameter and accommodative amplitude:low-dose atropine and myopia progression. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:1535–41. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-315440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hasebe S, Jun J, Varnas SR. Myopia control with positively aspherized progressive addition lenses:A 2-year, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:7177–88. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lam CS, Tang WC, Tse DY, Lee RP, Chun RK, Hasegawa K, et al. Defocus Incorporated Multiple Segments (DIMS) spectacle lenses slow myopia progression:A 2-year randomised clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:363–8. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.ZEISS Myopia Management Lens Solutions. [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 06]. Availablefrom: https://www.zeiss.ca/vision-care/en/for-eye-care-professionals/products/eyeglass-lenses/myopia-management-lens-solutions.html .

- 72.University (PolyU) THKP. Defocus Incorporated Multiple Segments (DIMS) Spectacle Lens for Myopia Control Awarded the Championship in Geneva's Invention Expo. [Last accessed on2021 Jun 06]. Available from:https://www.prnewswire.co.uk/news-releases/defocus-incorporated-multiple-segments-dims-spectacle-lens-for-myopia-control-awarded-the-championship-679876803.html .

- 73.Yang Z, Lan W, Ge J, Liu W, Chen X, Chen L, et al. The effectiveness of progressive addition lenses on the progression of myopia in Chinese children. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt J Br Coll Ophthalmic Opt Optom. 2009;29:41–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2008.00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang Z, Lan W, Ge J, Liu W, Chen X, Chen L, et al. The effectiveness of progressive addition lenses on the progression of myopia in Chinese children. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2009;29:41–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2008.00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gwiazda J, Hyman L, Hussein M, Everett D, Norton TT, Kurtz D, et al. A randomized clinical trial of progressive addition lenses versus single vision lenses on the progression of myopia in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1492–500. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bradley A, Rabin J, Freeman RD. Nonoptical determinants of aniseikonia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1983;24:507–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pauné J, Thivent S, Armengol J, Quevedo L, Faria-Ribeiro M, González-Méijome JM. Changes in peripheral refraction, higher-order aberrations, and accommodative lag with a radial refractive gradient contact lens in young myopes. Eye Contact Lens. 2016;42:380–7. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Walline JJ, Gaume Giannoni A, Sinnott LT, Chandler MA, Huang J, Mutti DO, et al. A randomized trial of soft multifocal contact lenses for myopia control:Baseline data and methods. Optom Vis Sci Off Publ Am Acad Optom. 2017;94:856–66. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Walline JJ, Greiner KL, McVey ME, Jones-Jordan LA. Multifocal contact lens myopia control. Optom Vis Sci Off Publ Am Acad Optom. 2013;90:1207–14. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fujikado T, Ninomiya S, Kobayashi T, Suzaki A, Nakada M, Nishida K. Effect of low-addition soft contact lenses with decentered optical design on myopia progression in children:A pilot study. Clin Ophthalmol Auckl NZ. 2014;8:1947–56. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S66884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lam CS, Tang WC, Tse DY, Tang YY, To CH. Defocus Incorporated Soft Contact (DISC) lens slows myopia progression in Hong Kong Chinese schoolchildren:A 2-year randomised clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:40–5. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pauné J, Morales H, Armengol J, Quevedo L, Faria-Ribeiro M, González-Méijome JM. Myopia control with a novel peripheral gradient soft lens and orthokeratology:A 2-year clinical trial. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:507572. doi: 10.1155/2015/507572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sankaridurg P, Holden B, Smith E, Naduvilath T, Chen X, de la Jara PL, et al. Decrease in rate of myopia progression with a contact lens designed to reduce relative peripheral hyperopia:One-year results. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:9362–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chamberlain P, Peixoto-de-Matos SC, Logan NS, Ngo Cheryl, Jones D, Young G. A 3-year Randomized Clinical Trial of MiSight Lenses for Myopia control. Optometry Vis Sci. 2019;96:556–67. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Walline JJ, Walker MK, Mutti DO, Jones-Jordan LA, Sinnott LT, Giannoni AG, et al. Effect of high add power, medium add power, or single-vision contact lenses on myopia progression in children:The BLINK randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:571–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Three-Year Study Indicates Pioneering Contact Lens Therapy Effective in Slowing Myopia Progression in Children by 59%. CooperVision. [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 06]. Available from:https://coopervision.com/our-company/news-center/press-release/three-year-study-indicates-pioneering-contact-lens-therapy .

- 87.Wildsoet CF, Chia A, Cho P, Guggenheim JA, Polling JR, Read S, et al. IMI –Interventions for controlling myopia onset and progression report. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:M106–31. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-25958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cho P, Cheung SW, Edwards M. The longitudinal orthokeratology research in children (LORIC) in Hong Kong:A pilot study on refractive changes and myopic control. Curr Eye Res. 2005;30:71–80. doi: 10.1080/02713680590907256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cho P, Cheung S-W. Retardation of myopia in Orthokeratology (ROMIO) study:A 2-year randomized clinical trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:7077–85. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Charm J, Cho P. High myopia-partial reduction orthokeratology (HM-PRO):Study design. Contact Lens Anterior Eye J Br Contact Lens Assoc. 2013;36:164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen C, Cheung SW, Cho P. Myopia control using toric orthokeratology (TO-SEE study) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:6510–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ruiz-Pomeda A, Pérez-Sánchez B, Valls I, Prieto-Garrido FL, Gutiérrez-Ortega R, Villa-Collar C. MiSight Assessment Study Spain (MASS). A 2-year randomized clinical trial. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256(5):1011–21. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-3906-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]