Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Since residency interviews became virtual due to COVID-19, and likely continue in the future, programs must find ways to improve their non-traditional recruiting methods. The objective of this study was to evaluate effectiveness of a structured, non-traditional approach on visibility and perception of the program as well as virtual interview experience.

METHODS

The focus of our approach was to ensure constant engagement while maintaining all pre-interview communication as resident-led and informal. The program focused on improving visibility and outreach through an organized utilization of social media platforms highlighting people and local culture. The virtual interview process was restructured with resident-led virtual meet and greets followed by small group discussions and providing virtual hospital tours, videos, and slides of the program's culture and expectationson the interview day. Perception of the program and the new approach to the interview process was assessed via an anonymous survey.

RESULTS

The program's visibility was measured via social media analytics with an increase in reach on Facebook from 0/post to as high as 4200/post and engagement 2/post to nearly 600/post. Tweet Impressions from approximately 350/mo to 11,000/mo with the increase in new Followers/month by 532.5%. Increase in total number of applicants in 2021 of 16% compared to average between 2018 and 2020. Survey response rate was 66.1%; of those 53.8% of interviewees attended a virtual meet and greet session. Perceptions of interviewees on our program was exclusively positive. Specific characteristics of the program that would make students rank us higher were program's culture, people, academics, and clinical experiences they would get as residents.

CONCLUSIONS

The exponential increase in our program's visibility and exclusively positive program assessment suggest that a structured approach utilizing social media and virtual technologies could improve both the recruitment and the virtual interview process while maintaining positive perceptions of the program.

KEY WORDS: Virtual residency interviews, Social Media, Student Engagement, Use of technology in interviews, Program visibility

Competencies: Professionalism, Interpersonal and Communication Skills, Systems-Based Practice

INTRODUCTION

In the spring of 2020, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) released recommendations to pause all clinical rotations for medical students along with travel,1 with the goals of both protecting medical students from unnecessary exposure to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and preserving of personal protective equipment to be used by essential healthcare workers. In the process, a key component of medical training was lost; i.e., the experiences gained from in-person clinical education, including the visiting medical student (VMS) programs. Medical students participate in these programs, known as away rotations, with the goal of matching into a specific program and similarly, residency programs will use these rotations to guide their recruitment process.2 Furthermore, these interactions in combination with in-person interview days have historically provided medical students with critical information used to create their individual residency rank lists.3 At the time of this publication, applicants are nearly all members of the millennial generation, who have integrated social media into multiple aspects of their daily lives. They turned to social media to learn about residency programs to determine the “best fit” in the absence of traditional in-person approach. This resulted in significant increase in the use of social media by surgery residency programs and many new accounts were created by programs that were not on social media platforms prior to the pandemic.4, 5, 6

Since the virtual interview process could play a large role in residency and fellowship applications moving forward, it is essential for residency programs to improve this process. Previous studies have shown the efficacy of virtual interviews in specific surgical sub-specialties,7 , 8 but the satisfaction of interviewees varied requiring more data. Moreover, there are not significant data available that assess the perception of interviewees of a program through virtual events and interviews. The Wright State University (WSU) General Surgery Residency Program made substantial efforts to improve program visibility and used non-traditional yet organized approach to enhance virtual interview process and provide program overview and culture. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of such an organized approach in our hybrid; i.e., a community hospital-based, university-affiliated program and assess interviewees perception of the program.

METHODS

Improving Program Visibility and Outreach

Using the social media strategies described in the literature platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, were used to provide comprehensive information about our program and learning environments to medical students interested in general surgery residency.6 , 9 From approximately June to December 2020, WSU posted to all three social media platforms at least once per week. Specifically, we created the following promotional materials strategically to introduce the place, people, and culture of our program:

-

(i)

Meet the Residents: Four 20-minute resident interviews in a series that consisted of 1 resident as a host interviewing a guest resident. The guest resident discussed their path to general surgery residency, why they chose WSU, and what they enjoy most about the program and the place.

-

(ii)

Meet the Attendings: Three attending testimonial videos in which they discussed their roles as faculty and passion for resident education.

-

(iii)

“Hot Wings, Cold Steel”: In this more informal series, an attending and a resident each eat 10 increasingly spicy chicken wings from local restaurants, but with each chicken wing, the attending is asked questions about surgical training, personal experiences, life in Dayton, OH, and were ultimately challenged with a surgical skill.

The program's visibility and outreach were evaluated through Twitter and Facebook analytics. The Instagram platform did not have analytics capabilities and therefore was not evaluated although we continued to post to Instagram throughout the application cycle. The specific social media definitions can be found in the Appendix.

Enhancing Virtual Interview Process

Following steps were taken to improve overall process of virtual interviews to replicate traditional in-person interviews and provide realistic information about the program:

-

(i)

Resident-Led Virtual Meet and Greet: Throughout the application cycle, we held two virtual meet and greet events that were led by residents and promoted using social media for increased participation. During these events, we first provided an overview presentation of our program before allowing for a question/answer session with the program leaders. This session ended with small resident-only sessions where medical students could meet current residents (without any program leaders and administrators) and ask any questions about the program, culture, diversity, learning environment, place, housing, etc. in smaller groups.

-

(ii)

Virtual Tour of the Hospitals: Since the applicants were not able to interview in person, we recorded and provided them,on the day of interviews, virtual tours of the hospitals where they would work as a surgical resident. This tour included the two area hospitals and details such as: a look at the hospitals in general, intensive care units, physicians and resident work rooms, and cafeteria.

-

(iii)

Digital Materials for Interview Day: We developed a video on the overview of the WSU general surgery program, expectations of the residents, and learning environments including sites of conferences, all to provide a sense of the overall atmosphere at WSU as a surgical resident.These videos featuring facilities, residents, and attendings were provided to applicants during virtual interview days to replicate a traditional in-person interview day. The videos were not published on social media or elsewhere due to facility restrictions and privacy.

Assessing Perception of the Program

All the medical student applicants who were invited and participated in our virtual residency interview process, were provided an IRB approved survey following their interview. The survey included both closed- and open-ended questions about applicant demographics, involvement in our virtual events and social media content, and perception of the program after virtual events and interviews. Moreover, the students were asked any specific characteristic of our program that would persuade them to rank us higher than others.

The total number of applicants was collected from 2018 to 2020 application cycles and compared to the 2020-2021 application cycle during which we implemented an organized approach to the virtual interview process to assess any differences in the applicant pool.

RESULTS

Program Visibility and Outreach

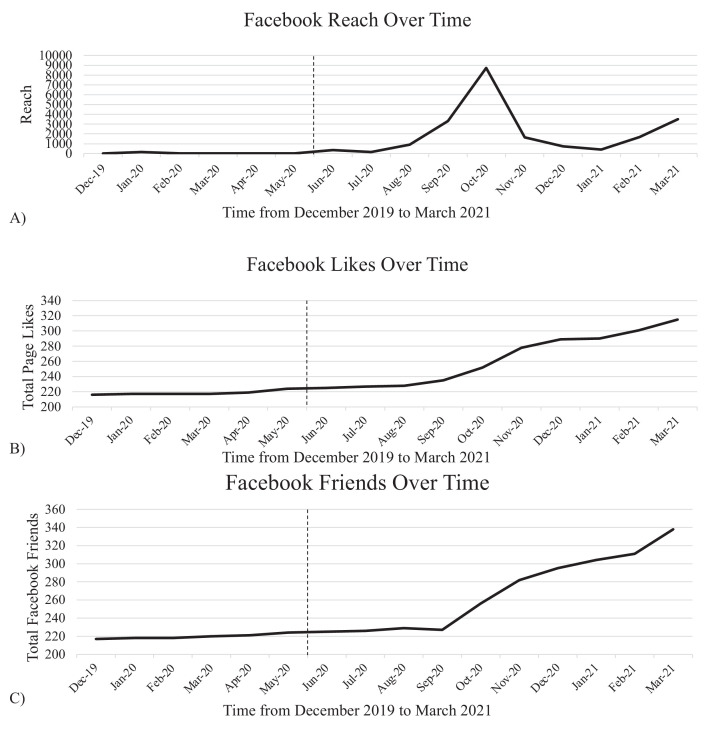

The mean number of total applicants per year prior to virtual interviews (from 2018 to 2020) was 634 compared to 736 for the 2020-2021 cycle; i.e., 16% increase in applications. WSU Facebook analytics comparing before virtual interviews era; i.e., December 2019 to virtual era of 2020-21 application cycle, beginning in June 2020, demonstrate an increase in Reach from 0/post to as high as 4200/post and Engagement growth from 2/post to nearly 600/post. Figure 1 illustrates trends in Likes, Followers, and Reach with a designation to mark when residents were granted posting privileges. Figure 2 displays Twitter analytics, showing Tweet Impressions grew from approximately 350 impressions/mo in 2019 to 11,000/mo in 2020. Moreover, the monthly rate of new Followers on Twitter increased from 4/mo pre-June 2019 to 25/mo after our organized approach to social media. This is an increase in the rate of new followers per month by 532.5% (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1.

Outlines A) Reach, B) Overall page likes, and C) Facebook friends noted on the WSU Facebook account over time from December 2019 to March 2021 (Match Day) with a dashed line to denote when the organized approach to social media was initiated.

FIGURE 2.

Outlines A) Impressions, B) New followers, and C) Tweets per month noted on the WSU twitter account over time from December 2019 to March 2021 (Match Day) with a dashed line to denote when the organized approach to social media was initiated.

Assessment of the Virtual Interview Process and Program's Perception

The two virtual meet and greet events created to increase awareness of the program prior to sending out formal interview invitations were attended by 80 and 30 medical students, respectively. The survey was sent to a total of 62 applicants who participated in our virtual interviews, of which 41 completed the survey (66.1% response rate). Of those who completed the survey, 21 (51.2%) students were males and the mean age of all the participants was 27.5 ± 3.4 years. Most of the respondents heard about our program either through their medical school or internet search (Fig. 3 ).

FIGURE 3.

Survey response of interviewees when asked how they heard of our General Surgery Residency program.

The survey results suggest 53.7% (22/41) of interviewees attended at least one of our virtual meet and greet sessions (Table 1 ). The thematic analysis suggested that after the virtual meet and greet events students perceived our program as positive and friendly,and said, “Program was friendly, made me want to apply.” Additional comments are in Table 2 . The students also perceived that our program provides wide range of experiences and autonomy and that our residents are supportive and happy. While Table 2 provides detailed description and examples of additional comments, below are the example comments from students in each of these themes:

"Well rounded program, good operative experience and autonomy, residents are happy.”

“I think it was clear from the meet and greet that the residents really do like each other and get along. They also came across as professional and gave good information about the program which as an insider I found was accurate and a good representation of WSU and Dayton.”

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Post Interview Survey Responses

| Categories | Responses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 51.2% (21/41) Male | ||

| Age | 23-41 yrs | ||

| Virtual meet and greet attendance | 53.8% (21/39) Attended | ||

| How was our program perceived post interview? | 56.4% (22/39) Excellent | 41% (16/39) Very Good | 2.5% (1/39) Good |

TABLE 2.

Thematic Analysis on the Perceptions of the Program

| Theme | Description | Example of Respondents’ Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of the program after virtual meet and greet | ||

| Positive and friendly | The program was perceived as friendly and amazing with positive environment | “It [program] was Cohesive, friendly, welcoming.” “Incredible, positive, supportive [program]” |

| Residents are supportive and happy | Camaraderie among residents | “Everyone was extremely friendly, and the residents appeared to be very happy.” “I was able to feel that residents care and support each other.” |

| Provides wide range of operative experience and autonomy | The program offered structured curriculum, high case volume, and early operative room experiences with autonomy | “Residents are well supported with alot of opportunities. Well-structured academics and wide case variety in the OR.” |

| Characteristics of our program that will make students rank us higher than others | ||

| Program culture, people, and academics | Friendly and supportive culture of the program along with strong teaching, mentorship and research assistance available. This also included availability of rural elective and robotic surgery | “Strong teaching, mentorship, and extensive opportunities for research” “Familial/supportive culture, optional research years” “Support the residents get from both attendings and each other” |

| Volume and breadth of cases and autonomy in OR | The program offered high case volume and exposure to many specialties, including trauma, surgical oncology, and others. This also includes the early operative room experiences with autonomy that residents have | “Autonomy that residents have starting intern year” “Early operative experience, heavy operative volume, and diversity of operative experiences” “Surgical oncology exposure, trauma exposure, more exposure to specialty surgeries” |

| Multiple training sites | Residents work at multiple hospitals in our program, including VA and Airforce Base | “Variety of hospital settings to work in” “Separate hospitals to see varying methods” |

| 50:50 split between fellowship and general surgery practice | Program graduates general surgeons and also supports them with fellowship placements | “50/50 practice vs. fellowship” “Fellowship placement” |

Majority of students (97.4%, 38/39) who attended the virtual meet and greet perceived program as excellent/very good and the rest as good after the formal virtual interviews. A few additional things students wished our program could have provided during interviews were, resident case volume and research projects, patient demographics, detailed tour of the hospitals, and any potential changes in the curriculum due to COVID-19 pandemic. Majority of the students, however, said they didn't need any more information and appreciated what was given. Specifically, students said,

“I can't think of anything- WSU actually did a great job of marketing themselves prior to the interview and gave good resources at the interview with the videos and PowerPoint. WSU's meet and greet was actually the most attended one I had been to and I thought the media was put together well in an organized and informative way.”

“I felt both videos gave a ton of great information. Yours is the first program I have seen provide a video tour during the interview time.”

A thematic analysis also suggested that the most important factors influencing students to rank our program higher than others included, program culture and academics, volume and breadth of cases and autonomy in OR, multiple training sites, and fellowship placement. Table 2 describes the specific comments. However, 1 student summarized it all well and said, “The retention rate of residents returning back to WSU as attendings is higher than average and reflects a positive residency experience. The 50:50 split between pursuing fellowship track and private practice is very ideal and likely reflects excellent mentoring and exposure throughout the residency. The residents seem genuinely content with their experience at WSU and struggle to find weaknesses in the program. The program director is a fairly recent graduate and can strongly relate to her residents. Training hospitals are all located within fairly close proximity and the housing market is easy to navigate.”

DISCUSSION

The virtual residency interview process provided several benefits for medical students including reduced travel costs, increased scheduling flexibility, and decreased days away from clinical rotations.10 Thus, some authors argue for a continuation of virtual interviews even post COVID.7 , 10 Our study provides an organized approach to improve program visibility and overall virtual interview process and program's perception.

Since the emergence of social media applications, residency programs have attempted to harness the power of these platforms to expand program visibility and residency applicant pools.11 Our results suggest that the use of social media clearly improved our program's visibility, which was in accordance of the previous literature.6 The video series of meeting with residents and faculty that we developed along with virtual meet and greet events and smaller group discussions with residents not only provided the social media outreach, but also provided additional information to potential applicants about the place, camaraderie between residents, and personality of our residents and faculty they will be working with. Such information led to positive impression of the program where applicants described our program as friendly and supportive with a diverse, high volume case load. These attributes that they used to describe our program were also factors that they claimed to have influence on how they determine the rank list. These results corroborate with previous studies, where residents’ interpersonal factors and quality of life have been shown to improve programs rank.12, 13, 14 Further, as previously reported by Henderson, et al., we also believe that candid and personable content helps create a “friendship” through social media that ultimately assists with recruitment.15 Our program had a 16% increase in total applicants, which was significantly higher than the national increase of 7.1%.16 However, this could be partly due to the fact that virtual interviews and associated time and cost savings for applicants enabled them to apply in more programs, which was evident by the overall increase in total number of general surgery applications by applicants in 2021.16

Since the interview process plays a large role in residency and fellowship applications, programs should improve the virtual interview process considering it could become a standard for the foreseeable future. Our results showed that the virtual hospital tours and program overview videos were very helpful to the applicants as this content provided insight into the facilities, they will be working in along with the learning environment of our program. While one of the respondents in our study even stated that our program was “the first program to provide a video tour of the hospitals,” similar approaches have been described at the residency and fellowship level utilizing virtual reality medium outside of general surgery realm.17, 18, 19 The virtual reality, however, may not work for all as it causes motion sickness in some people as was evident in the study by Zertuche and others and thus some respondents suggested rather a video tour that we utilized in our study.18 The video tours could also provide a cost effective option compared to virtual reality technology.

While our study provides valuable qualitative data, it should be viewed in light of some limitations. This is a single institution study with a single year data. A more complete analysis could be performed if trended over a longer period of time and/or over multiple institutions. The survey could be biased as it was filled out right after the interview process by applicants, who may have not trusted the anonymity of the results, or our program may have been one of the first few they visited virtually. Their opinions about our program might have changed after they saw more programs and/or had time to reflect. Further, there is a possible sample bias regarding the subjective impact of our social media efforts in how your program is perceived by the applicants since we only sampled interviewees who applied to our program and received an interview. In our program, we were able to find and engage residents in creating social media content and had faculty who were willing to participate. It is possible that some programs may have difficulty identifying such a dedicated group of people. However, since social media pages of most of the surgery programs are managed by residents or administrative staff,20 we believe that providing them departmental support in developing new social media content could certainly help.

CONCLUSION

The global pandemic has significantly challenged the traditional in-person residency interview process and has accelerated the adoption of technologies that could question the future needs for physical proximity during residency interviews. The general hesitancy and primary concern in participating in the virtual interview process is an inability to obtain an accurate picture of the program and/or applicant. A structured approach described in our study that involves developing credible and personable digital media content, utilizing social media to share and promote the content, and using technological advancement for virtual interviews has allowed applicants to experience different facets of our program in a more lighthearted way making it seem more personable. Such an approach is, therefore, feasible and could effectively improve the virtual interview process and maintain positive perception of the program. More research is necessary to assess whether such an approach and more social media outreach could increase number of diverse applicants as well.

Author Contributions

Casey T. Walk, MD - data collection, interpretation, manuscript writing and editing. Rodrigo Gerardo, MD - development of virtual platform content, data collection, manuscript editing. Rebecca Tuttle, MD - data interpretation, critically reviewing and editing manuscript. Priti Parikh, PhD - study design, survey development, analysis, and critically reviewing and editing manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Important Guidance for Medical Students on Clinical Rotations During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak. AAMC. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/important-guidance-medical-students-clinical-rotations-during-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak. Accessed March 4, 2021.

- 2.Wright AS. Virtual interviews for fellowship and residency applications are effective replacements for in-person interviews and should continue post-COVID. J Am Coll Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.09.005. Published online October. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sell NM, Qadan M, Delman KA, et al. Implications of COVID-19 on the general surgery match. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e155–e156. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang HA, Boudreau H, Khan S, et al. An evaluation of social media utilization by general surgery programs in the COVID-19 era. Am J Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.04.014. Published online April. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bludevich BM, Fryer M, Scott EM, Buettner H, Davids JS, LaFemina J. Patterns of general surgery residency social media use in the age of COVID-19. J Surg Educ. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.04.017. Published online May. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walk CT, Gerardo R, Parikh PP. Increasing social media presence for graduate medical education programs. Am Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1177/00031348211031848. Published online July 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bamba R, Bhagat N, Tran PC, Westrick E, Hassanein AH, Wooden WA. Virtual interviews for the independent plastic surgery match: a modern convenience or a modern misrepresentation? J Surg Educ. 2021;78:612–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vining CC, Eng OS, Hogg ME, et al. Virtual surgical fellowship recruitment during COVID-19 and its implications for Resident/Fellow recruitment in the future. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-08623-2. Published online May 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92:1043–1056. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carpinito GP, Khouri RK, Kenigsberg AP, et al. The virtual urology residency match process: moving beyond the pandemic. Urology. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2021.06.038. Published online July. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2017;92:1043–1056. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yousuf SJ, Kwagyan J, Jones LS. Applicants’ choice of an ophthalmology residency program. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:423–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stefanidis D, Miles WS, Greene FL. Factors influencing residency choice of general surgery applicants—how important is the availability of a skills curriculum? J Surg Educ. 2009;66:325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huntington WP, Haines N, Patt JC. What factors influence applicants’ rankings of orthopaedic surgery residency programs in the national resident matching program? Clin Orthop. 2014;472:2859–2866. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3692-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson A, Bowley R. Authentic dialogue? The role of “friendship” in a social media recruitment campaign. Henderson A, Edwards L, eds. J Commun Manag. 2010;14:237–257. doi: 10.1108/13632541011064517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ERAS Statistics. AAMC. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/interactive-data/eras-statistics-data. Accessed March 25, 2021.

- 17.Dinh A, Furukawa L, Caruso TJ. The virtual visit: using immersive technology to visit hospitals during social distancing and beyond. Pediatr Anesth. 2020;30:954–956. doi: 10.1111/pan.13922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zertuche JP, Connors J, Scheinman A, Kothari N, Wong K. Using virtual reality as a replacement for hospital tours during residency interviews. Med Educ Online. 2020;25 doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1777066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson DB, White PT, Rajaram R, Antonoff MB. Showcasing your cardiothoracic training program in the virtual era. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111:1102–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill SS, Dore FJ, Em ST, et al. Twitter use among departments of surgery with general surgery residency programs. J Surg Educ. 2021;78:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]