Introduction

Durvalumab is an immunotherapy that targets programmed cell death receptor ligand 1 (PD-L1). It has demonstrated encouraging results in the treatment of multiple malignancies and is the subject of ongoing clinical investigations. Here, we described a case of durvalumab-associated generalized morphea with overlapping vitiligo in a patient who also developed durvalumab-associated myasthenia.

Case report

A 60-year-old woman with stage IIIA lung adenocarcinoma underwent chemoradiation with cisplatin and pemetrexed, followed by maintenance therapy with 10 m/kg intravenous durvalumab for 26 cycles over 1 year.

Five months after completing durvalumab, she developed immunotherapy-associated myasthenia gravis confirmed by electromyography. She had no evidence of thymoma. She required hospital admission where she received 5 days of intravenous methylprednisolone with plasma exchange, 2 infusions of rituximab, and prolonged oral steroids with good control of her disease.

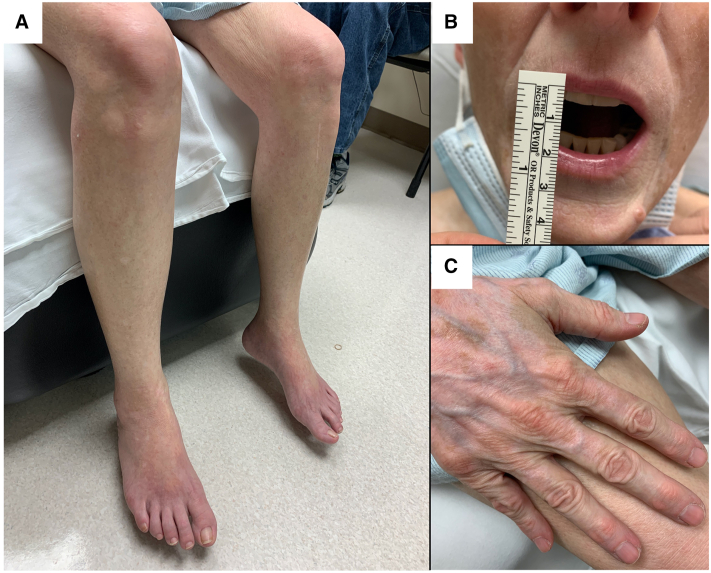

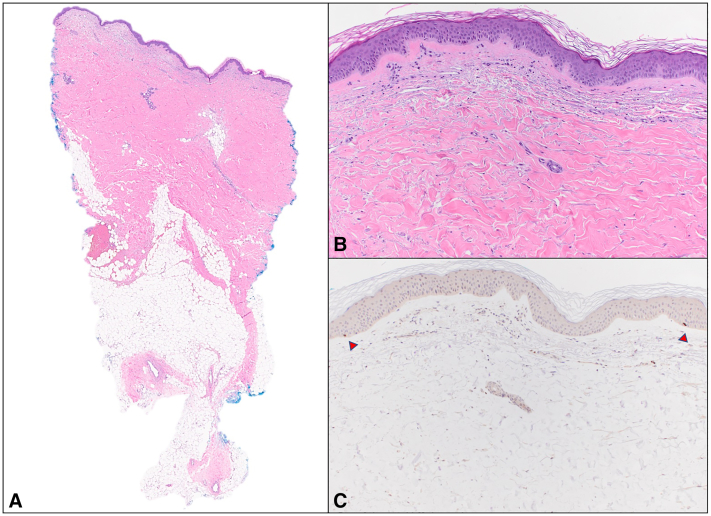

Seven months after completing durvalumab, she experienced progressive thickening, stiffening, and hypopigmentation of her skin. She also reported joint and muscle pain. She had started oral prednisone 2 months prior for her immunotherapy-associated myasthenia gravis and was still taking 20 to 30 mg daily. Rheumatologic testing was broadly negative, including anti-Ro, anti-La, anti-Smith, anti-RNA polymerase III, anti–topoisomerase 1, anticentromere, anticyclic citrullinated peptide, and rheumatoid factor. She then presented to dermatology, and the examination showed fibrotic, thickened plaques on the face, neck, upper portion of the trunk, and bilateral extremities with overlying depigmentation. There were no sclerotic plaques on the hands and feet, although the dorsal aspect of the hands had patches of depigmentation with laxity (Fig 1). There was no sclerodactyly. A punch biopsy of the upper portion of the back showed a squared silhouette, diffuse dermal fibrosis, and atrophic adnexal structures (Fig 2, A). An additional immunohistochemical study with anti-SOX10 revealed the loss of melanocytes in the epidermis (Fig 2, A and B). Overall, this constellation of clinical and histologic findings indicated a diagnosis of generalized morphea with superimposed vitiligo. The patient was started on mycophenolate mofetil and UV-A1 phototherapy biweekly. She also participated in physical therapy. Five months into this regimen, her prednisone was successfully tapered down to 5 mg daily without a myasthenia flare. She reported mild improvement in the range of motion and stable sclerosis. She remains without evidence of malignancy.

Fig 1.

Durvalumab-associated morphea with overlapping vitiligo. Clinical features show smooth, tightened, thickened skin with overlying ill-defined hypopigmented patches on the lower portion of both the legs (A). Perioral sclerosis causes the reduced opening of the mouth (B). The dorsal aspect of the hand shows depigmentation without underlying morphea. There is no sclerodactyly of the hand and no telangiectasias of nail beds (C).

Fig 2.

Durvalumab-associated morphea with overlapping vitiligo. Histologic features from punch biopsy on back. Sections showed skin and subcutis with squared silhouette and diffuse dermal fibrosis, with thickened dermal collagen and atrophic adnexal structures (A and B, Hematoxylin-eosin; original magnification: A, ×10; B, ×100). There was a sparse superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and mild edema in the papillary dermis. An immunohistochemical study with anti-SOX10 highlighted rare, scattered basally located junctional melanocytes (arrowheads) that were markedly reduced in number. (C, Original magnification: ×100.)

Discussion

Durvalumab is a fully human monoclonal IgG1 κ antibody targeting PD-L1, which is upregulated in cancer cells.1 Mechanistically, the interaction of PD-L1 with its ligand PD-1 downregulates the T-cell response, allowing cancer cells to evade the host immune system. However, by inhibiting PD-L1, durvalumab enables native T-cells to mount an immune response against malignant cells. Durvalumab was first approved in 2017 and is currently used to treat lung cancer. Additionally, the ongoing studies seek to evaluate its effectiveness as monotherapy and/or combination therapy against other malignancies.

The long-term side effects of durvalumab remain to be determined. Cutaneous immune-related adverse events (irAEs) from durvalumab reported to date include lichenoid dermatitis, granulomatous skin reactions, psoriasis, bullous pemphigoid, and dermatomyositis. Additionally, other PD-L1 inhibitors, such as atezolizumab and avelumab, have been associated with acneiform/follicular dermatitis or rosacea, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, superficial perivascular dermatitis, and vitiligo.2,3 More data are available regarding the cutaneous irAEs of programmed cell death receptor 1 inhibitor, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, including reports of morphea and sclerodermoid reactions.4,5 PD-1 inhibitors share a similar mechanism of action to PD-L1 inhibitors by targeting the interaction between PD-L1 and PD-1. Therefore, similar cutaneous irAEs with PD-L1 inhibition may be anticipated.

This case is medically interesting for multiple reasons. Diagnostically, it was important to correctly identify morphea as the unifying diagnosis for her sclerosis. Fibrosing conditions, such as scleredema and eosinophilic fasciitis were considered but inconsistent by examination and histology. Our patient’s biopsy showed dense collagen and fibrosis throughout the dermis; however, there was no evidence of acid mucopolysaccharide between collagen bundles, as would be seen with scleredema and the fascia was not thickened as would be seen with eosinophilic fasciitis. Additionally, our patient’s biopsy showed adnexal entrapment between the collagen bundles and adnexal atrophy. These histologic findings suggested a diagnosis of morphea or scleroderma. The physical examination did not show sclerodactyly, nailfold changes, telangiectasia, or other stigmata of systemic sclerosis, confirming generalized morphea as the correct diagnosis.

This patient presented with multiple irAEs, which raises the question of when and how to attribute AEs to immunotherapy. IrAEs can present with remarkable latency2,3 and careful consideration must be given to the clinical context for a patient who develops a suspected irAE. Our patient developed multiple autoimmune conditions simultaneously, which was more fitting for a unifying etiology rather than 3 unrelated events. Additionally, she had no prior history of autoimmune disease before durvalumab therapy. Although paraneoplastic conditions must also be considered in patients with underlying malignancy, dermatologic and neurologic paraneoplastic conditions typically precede the diagnosis of the underlying malignancy, and our patient did not develop signs of morphea, vitiligo, or myasthenia until after she had undergone treatment with durvalumab.6

Furthermore, the constellation of findings suggests that certain patients may be predisposed to developing irAEs from immunotherapy. Although it is possible to hypothesize the mechanisms by which durvalumab contributed to morphea with myasthenia and vitiligo in our patient, it is not known why this patient was predisposed to develop all 3 conditions. We know that certain human leukocyte antigen types predispose individuals to severe drug hypersensitivities.7 Similarly, it would be of value to identify biomarkers or unique gene profiles that predict irAEs.8 Predictive models would optimize informed decision-making between treatment teams and patients regarding the risks and benefits of immunotherapy.

Given the profound breadth of irAEs this patient experienced, it is notable that she also had a durable cancer response. Some studies have suggested that patients with irAEs have improved cancer outcomes, specifically vitiligo.9 We do not know if having multiple irAEs also suggests a profound T-cell response to the malignancy that is durable and further studies would be beneficial in this area of oncodermatology.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Drs Martel, Cho, Curry, and Heberton contributed equally to this article.

Funding sources: None.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Paz-Ares L., Dvorkin M., Chen Y., et al. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394:1929–1939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis S.R., Vierra A.T., Millsop J.W., Lacouture M.E., Kiuru M. Dermatologic toxicities to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: a review of histopathologic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):1130–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhardwaj M., Chiu M.N., Pilkhwal Sah S. Adverse cutaneous toxicities by PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors: pathogenesis, treatment, and surveillance. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2022;41(1):73–90. doi: 10.1080/15569527.2022.2034842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terrier B., Humbert S., Preta L.H., et al. Risk of scleroderma according to the type of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tjarks B.J., Kerkvliet A.M., Jassim A.D., Bleeker J.S. Scleroderma-like skin changes induced by checkpoint inhibitor therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:615–618. doi: 10.1111/cup.13273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelosof L.C., Gerber D.E. Paraneoplastic syndromes: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(9):838–854. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karlin E., Phillips E. Genotyping for severe drug hypersensitivity. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(3):418. doi: 10.1007/s11882-013-0418-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M., Zhai X., Li J., et al. The role of cytokines in predicting the response and adverse events related to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.670391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teulings H.E., Limpens J., Jansen S.N., et al. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in patients with stage III-IV melanoma receiving immunotherapy and its association with survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(7):773–781. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.4756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]