Abstract

Congenital heart disease (CHD) affects ~ 1% of all live births but a definitive etiology is identified in only ~50%. The causes include chromosomal aneuploidies and copy number variations, pathogenic variation in single genes, and exposure to environmental factors. High throughput sequencing of large CHD patient cohorts and continued expansion of the complex molecular regulation of cardiac morphogenesis has uncovered numerous disease-causing genes, but the previously held monogenic model for CHD etiology does not sufficiently explain the heterogeneity and incomplete penetrance of CHD phenotypes attributed to a single gene. Here, we provide a summary of well-known genetic contributors to CHD and discuss emerging concepts supporting complex genetic mechanisms that may provide explanations for cases that currently lack a molecular diagnosis.

Keywords: congenital heart disease, genetics, cardiac development

1. Introduction

Congenital heart defects (CHD) are a global pediatric concern, affecting ~1% of all live births [1]. In recent years, advances in perinatal care and diagnosis, medical management and surgical repair techniques of CHD has led to drastically improved survival outcomes, even in complex forms of CHD [2, 3]. However, the shifting pattern of CHD related mortality has now transferred the burden to an older population, inviting new challenges in the management of long-term disease and associated co-morbidities [4]. In contrast, the complex, multifactorial etiology of CHD along with the heterogeneity of CHD phenotypes, has made it difficult to uncover precise molecular mechanisms underlying its pathogenesis, precluding efforts for prenatal intervention to prevent CHD. Accordingly, the incidence of CHD has remained consistent, even in recent years [5, 6].

Historically, discovery of heritable risk factors for CHD relied on tracing disease transmission within multiple generations of an affected family. Presently, the application of next generation sequencing (NGS) in small and large CHD cohorts have led to the discovery of numerous pathogenic variants, rapidly increasing our understanding of CHD genetics. In the current landscape, pathogenic variation accounts for ~40% of human CHD cases, which includes chromosomal aneuploidies, copy number variations (CNVs), and single nucleotide variants (SNVs) [7]. Functional analysis of CHD-causing genes in a myriad of animal and cell based models have further implicated several cellular and molecular processes as we begin to unravel the complex mechanisms underlying CHD pathogenesis [8].

In the era of multi-dimensional-omics, deep sequencing, and machine learning technology, it is possible to draw a comprehensive picture of dynamic changes in the genome, epigenome and proteome underlying cardiac morphogenesis and CHD. In this review, we discuss recent advances in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac development, summarize established genetic risk factors for CHD and discuss recent insights in elucidating complex mechanisms that may contribute to CHD with hitherto unknown etiology.

2. Molecular regulation of heart development

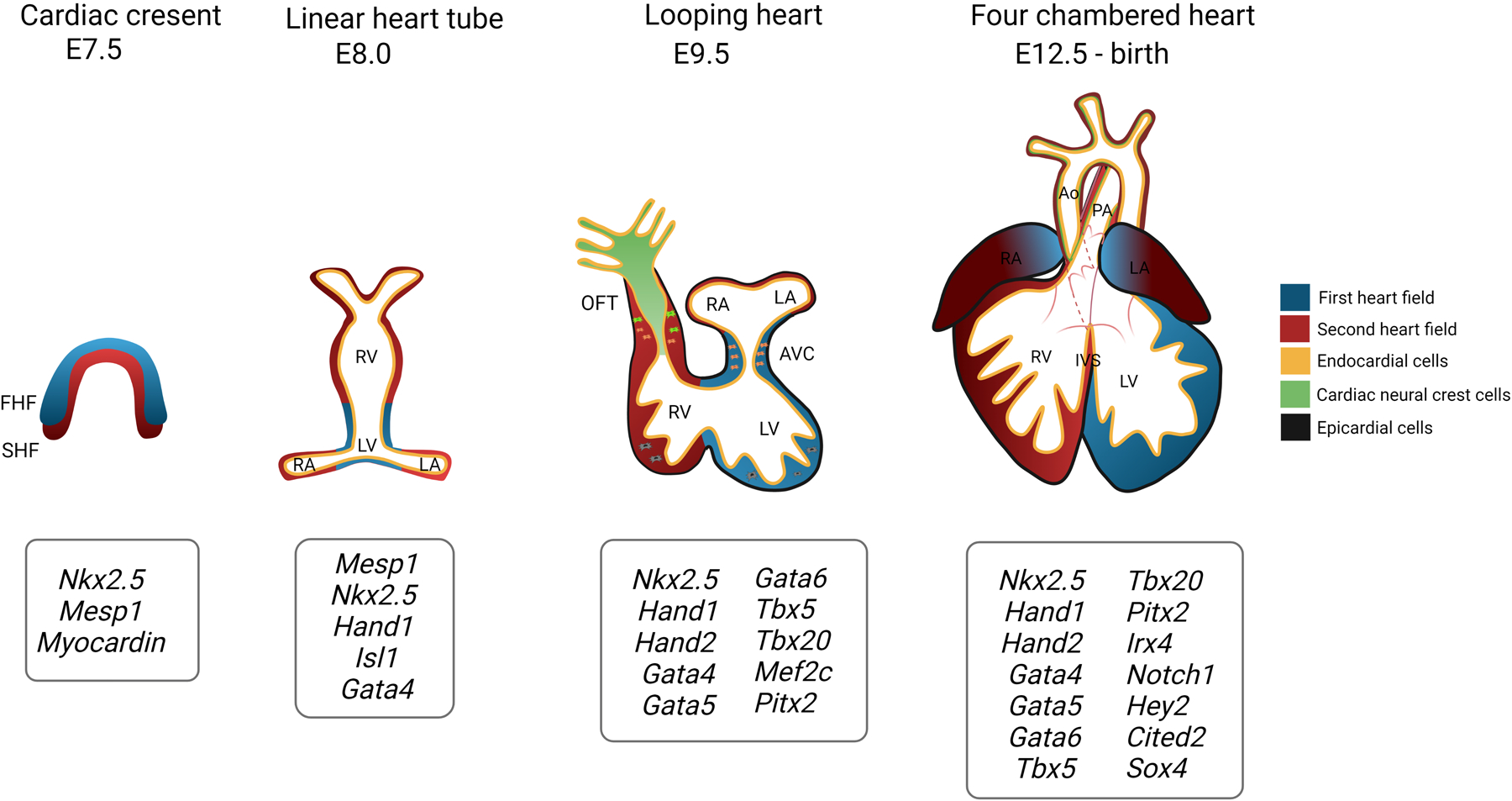

As CHD is the direct consequence of abnormal heart development, a detailed understanding of cardiac morphogenesis is prerequisite to delineating mechanisms underlying CHD. Here, we provide a brief overview of recent advances and refer readers to more comprehensive reviews of cardiac development [9, 10]. As the heart is the first organ to form, cardiac development relies on crucial spatiotemporal interactions between distinct multipotent cardiac progenitors during early embryogenesis. A highly coordinated signaling network of NODAL, TGFβ, BMP, WNT and FGF induce expression of a core group of cardiac transcription factors including NKX2–5, GATA4/5/6, MEF2, TBX1/5/20, and ISL1 that function in a mutually reinforcing cascade to drive lineage restriction and differentiation of progenitor cell populations (i.e., first and second heart field) to chamber specific cardiac cell types (Figure 1). Single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has become a powerful tool to identify lineage specific transcriptional networks. ScRNA-seq of anatomically distinct cardiac regions at different developmental time points has helped map the position of first heart field and second heart field progenitors relative to each other and allowed the identification of a novel population of cells that give rise to the epicardium [11–15]. Parallel to this, studies have utilized the differentiation of human stem cells, including both induced pluripotent stem cells (h-iPSC) and embryonic stem cells (h-ESC) to distinct cardiac cell types in vitro to characterize molecular signatures that drive cardiac lineage restriction [16–19]. The development of h-iPSC derived cardioids, which can recapitulate many morphologic and molecular processes that occur in vivo and are amenable to gene editing, also represent a new model for investigating how cardiac development goes awry to cause CHD [20, 21]. By harnessing the potential of live imaging and deep resolution sequencing, iPSC-derived cardioids provide a new platform for modeling cardiac development and CHD [22–24].

Figure 1. Key stages and regulatory genes in mouse cardiac development.

At embryonic day (E) 7.5, the first heart field (FHF) progenitors, followed closely by the second heart field (SHF) progenitors, become spatially organized into the cardiac crescent at the anterolateral plate of the developing embryo. At ~8.0, these cells migrate to the ventral midline and fuse together to form a linear heart tube containing an inner endocardial lining. The heart tube undergoes rightward looping and begins segmenting into the common atria and common ventricles. Furthermore, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transformation proceeds in the atrioventricular canal (AVC) and outflow tract (OFT) along with neural crest cell migration to the OFT. Subsequently, complete septation of the heart gives rise to four distinct chambers as well as the aorta (Ao) and pulmonary artery (PA) and further remodeling of endocardial cushions lead to the atrioventricular and semilunar valves. A partial list of key cardiac regulatory genes at each stage is shown. RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; IVS, interventricular septum. Created with Biorender.com.

3. Established genetic etiologies of CHD

Known genetic risk factors for CHD can be identified ~40% of cases, with recent literature reviews estimating chromosomal aneuploidies accounting ~13% of CHD cases, chromosomal CNVs of ~25% of syndromic and ~10% of non-syndromic cases, and SNVs in 12% (including both syndromic and non-syndromic) of CHD [7, 25]. Decades of research has been dedicated to investigating molecular mechanisms underlying these defects, which are briefly discussed below.

3.1. Chromosomal aneuploidy and copy number variation

Chromosomal aneuploidies such as trisomy 13, trisomy 21, monosomy X (Turner syndrome) and others are well-established factors for syndromic CHD are associated with cardiac septal and cardiac outflow tract (OFT) defects [26]. Although the exact pathogenic effect of aneuploidies is unknown, the dosage-balance model postulates that alterations in quantities of dose-sensitive genes located on over- or under- represented chromosomes are causative of the defects observed. This concept can be extrapolated to CNVs, described as 1 kilobase to several megabase-sized regions of duplication and/or deletion in the genome, that have been linked to both syndromic and nonsyndromic forms of CHD [27, 28]. To this effect, a recent meta-analysis of CNV data including 4634 nonsyndromic CHD cases revealed ohnologs, which are genes retained from whole genome duplication events due to crucial dosage effects, are overrepresented among CHD genes, suggesting that disrupted gene dosage, rather than gain/loss of gene function, may be a more common mechanism underlying CHD [29].

3.2. Single gene defects

The last decade has seen a dramatic increase in the application of next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies to decipher genetic contributors of CHD [30]. The NIH/NLHBI funded Pediatric Cardiac Genomics Consortium (PCGC), which has recruited >13,000 CHD probands with >5000 parent-offspring trios, has described the discovery of CHD-causing genes at an unprecedented rate [31–36]. Analysis of whole exome sequencing (WES) data from PCGC has established distinct contributions of de novo and inherited variants in developmental genes in syndromic CHD and nonsyndromic CHD, respectively, and a curated list of >400 genes which are recognized to have pathogenic variants that may contribute to CHD [30, 33]. At a glance, these CHD genes encode for cardiac transcription factors (NKX, GATA and T-box family members), structural proteins (MYH6/7/11, ACTC1, ELN), proteins involved in cell signaling and cellular processes (NOTCH1, FLT4, VEGFR) and chromatin modification enzymes (KMT2D, H2UB1) [5, 7, 30]. Studies independent of PCGC have also utilized NGS to identify novel risk loci in smaller CHD cohorts [37–42]. More recently, studies from PCGC as well as others are employing a more phenotype driven approach to identify causal gene variants and their mechanisms. This has led to the identification of a disrupted WAVE2 complex specifically in left ventricular outflow tract obstructions (LVOTO) as well as NOTCH and VEGF signaling disruption in tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) [35, 43–46]. As more studies undertake this approach, the goal will be to profile disrupted molecular signaling networks for different CHD subtypes.

4. New insights into molecular genetic mechanisms of CHD

Even with this large list of identified CHD candidate genes, a definite pathologic factor cannot be identified in ~50% of CHD cases. Furthermore, the monogenic (“one gene-one disease”) model does not sufficiently explain the heterogeneity of CHD phenotypes and incomplete penetrance attributed to a single variant [6, 25]. Recent publications have largely been focused on recognizing novel mechanisms that potentially explain the vast majority of CHD cases that lack a categorical etiology and are discussed below.

4.1. Oligogenic inheritance and genetic modifiers

The notion for oligogenic inheritance of CHD has gained much traction in recent years with several studies publishing experimental proof in support of this model. Previously, coinheritance of rare sequence variants in two interacting genes, COL2A1 and COL9A1, were reported in patients with atrioventricular septal defects (AVSDs) at a statistically significant threshold [39]. A mouse forward genetics screen revealed non-Mendelian segregation of CHD in mutant lines and identified a digenic mechanism for hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) pathogenesis involving two CHD genes, SAP130 and PCDHA9. Mutations in these genes were found together in a patient with HLHS [65]. Recently, WES of a nuclear family with members exhibiting congenital cardiomyopathy revealed affected individuals had inherited three missense single nucleotide variants in MKL2, MYH7 and NKX2–5 and further analysis of these variants in compound heterozygous mice implicated the role of NKX2–5 as a genetic modifier in the pathogenesis of CHD [47]. Additionally, mice compound heterozygous for the interacting genes Megf8 and Mgrn1 that are responsible for modulating hedgehog signaling and whose orthologs have been implicated in human CHD, display heterotaxy and CHD [48]. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) of 100 isolated TGA affected subjects revealed TGA cases harbored significantly more sequence variation in CHD genes, but no clinically relevant variant was identified lending credence to an oligogenic or polygenic inheritance of TGA [49]. Of note, several CHD genes such as NOTCH1, FLT4, and SMAD6 have incomplete penetrance of disease, suggesting that oligogenic or polygenic inheritance of variants may be required for disease manifestation. However, caution must be taken when interpreting multiple co-occurring variants, as a subset of these may ultimately represent benign sequence variants with increased knowledge of genetic variation in diverse human populations. Accordingly, more research is needed before making definitive conclusions. As CHD patient sequencing data becomes more available, future machine learning approaches should consider the use of polygenic risk scores to identify and diagnose clusters of pathologic genetic variation within an affected individual. [50].

4.2. Genetic Mosaicism

Post-zygotic somatic mutations occurring early during embryogenesis can result in cell populations with discrete genotypes, one or more of which may contain pathogenic variants. Disease manifestation largely depends on the proportion and tissue distribution of variant-carrying cells and though traditionally studied in cancer, somatic mutations have been implicated in other diseases such neurodevelopmental disorders and vascular malformations [66]. To this end, WES from 715 CHD trios from PCGC were analyzed for somatic mosaicisms, revealing mosaicism of several CHD genes including KMT2D, ZEB2, WDR19, and TBX20 in the blood or saliva from CHD probands [51]. Subsequently, using both blood and cardiac tissues, WES of 2530 CHD proband-parent trios from PCGC revealed potentially pathogenic mosaicism in 25 patients, with more damaging effects observed in probands with higher allele fractions [52]. However, it is important to note that out of 2530 CHD trios sequenced, matched cardiac tissue was obtained from only 66 subjects and the average read depth of sequenced heart tissue was 160X. This analysis was further limited by the anatomical location from which the tissue was taken. In order to comprehensively capture mosaicisms that drive malformations, future studies should rely on the use of deeper resolution NGS sequencing technologies (>400X coverage) from relevant tissues.

4.3. Non-coding elements

Although WES has been key to identifying causal genes, it only covers 1–2% of the genome and ignores noncoding regulatory elements that potentially contribute to disease. Previously, a homozygous mutation in an enhancer region ~90 kb downstream of TBX5 was found to be associated with cardiac septal defects [53]. Subsequently, tremendous efforts are being made to map cis-regulatory elements pertinent for heart development so that we may start exploring pathogenic variation in these sequences [54]. Recently, WGS of 763 CHD trios along with 1,611 unaffected controls identified de novo mutations in noncoding genomic sequences, harnessing previously published ChIP-seq data and machine learning to identify variant heart enhancers for functional testing [55].

4.4. Gene-environment interactions

Although environmental risk factors account for ~10% of CHD, this does not account for potentially pathogenic gene-environment interactions that may contribute to CHD [56]. While little is known about gene-environment interactions in human CHD, murine studies have revealed interactions of Notch1 haploinsufficiency with maternal hyperglycemia and hypoxia that lead to highly penetrant CHD [57] [58]. Similarly, murine studies have shown that concomitant genetic defects in second heart field cells and prenatal alcohol exposure leads to increased incidence of cardiac OFT defects [59]. Future studies should focus on identifying genetic aberrations in affected patients that have been exposed to environmental risk factors to determine the contribution of gene-environment interactions in CHD pathogenesis.

4.5. Disruption of gene regulatory networks

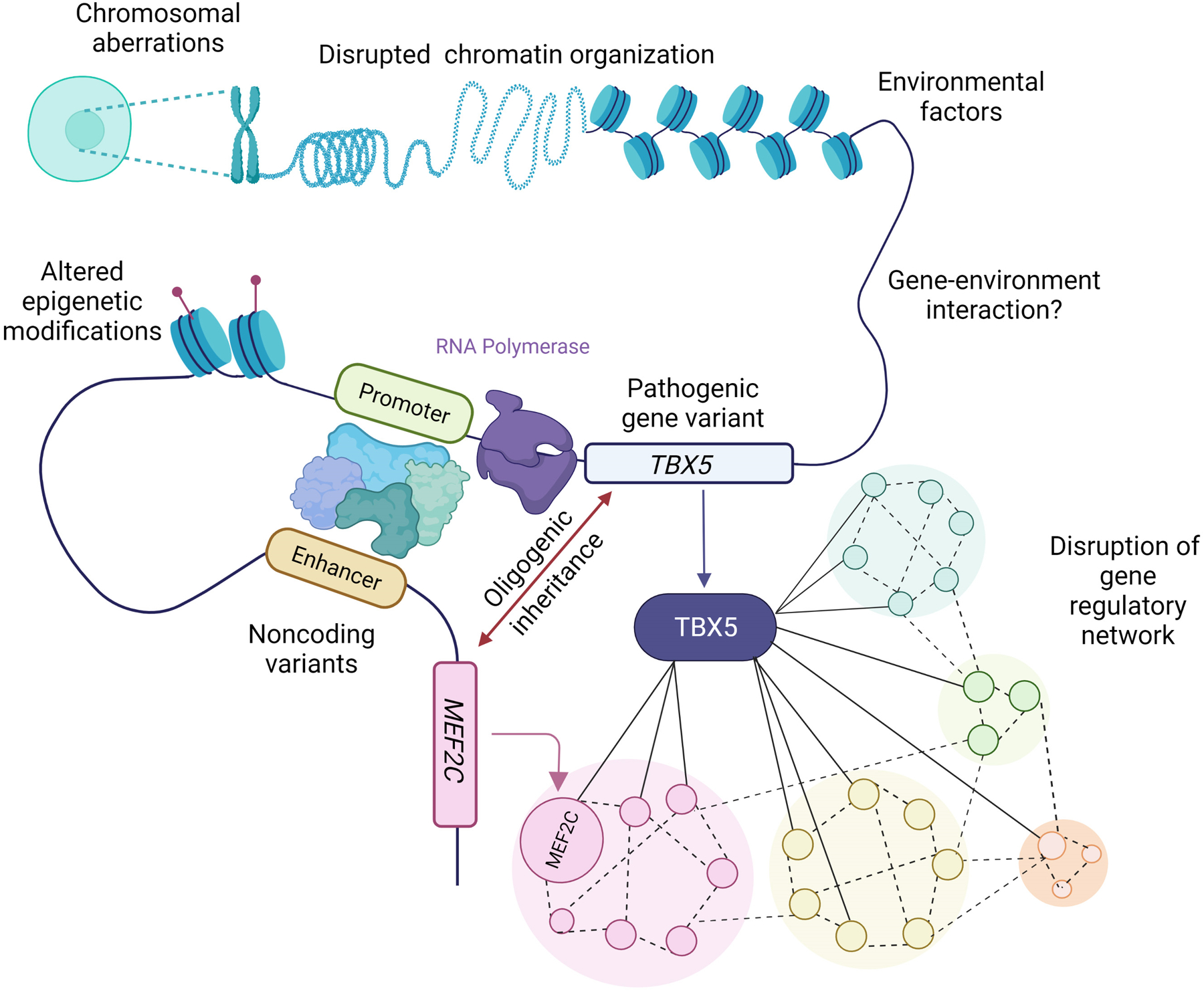

With the emergence of more mechanistic studies of CHD genes, it has become clear that disruption of gene regulatory networks (GRN), rather than a pathogenic gene, accounts for a significant subset of CHD. Synergistic action of cardiac transcription factors during cardiac development means damaging mutations in one has the potential to affect the entire transcriptional network, as described for a hypomorphic MEF2C variant that led to impaired GATA4 function and complete CHD penetrance [60]. Similarly, alterations in the gene dosage of GATA6 disrupts several transcriptional networks critically involved in development of the heart (GATA4, HAND2, KDR) [61]. Mapping of a GRN for TBX5 revealed interaction with vulnerable CHD genes including MEF2C, which is sensitive to dosage effects in maintaining network stability [62]. Reanalysis of WES from TOF patients revealed that many pathogenic variants that were identified belonged to a highly interconnected protein interaction network, with KDR and NOTCH1 representing central nodes [63]. This model can be applied to pathogenic mutations in genes coding proteins involved in post-translational regulation of other CHD genes such as NAA15, which encodes a protein subunit responsible for stable N-terminus acetylation of a host of proteins. Perturbation of NAA15 dosage in iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes leads to disruption in steady state levels of 562 proteins, four of which are established CHD genes [64]. As described above, sequence variation and dose disruption of a single cardiac transcription factor can have ripple effects across the cardiac gene program, in a phenotype specific manner (Figure 2). Conceptually, this is similar to the genetic etiologies for human RASopathies wherein pathogenic variants in genes that encode for critical factors in the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway result in a similar phenotypic spectrum, that includes cardiac diseases [67]. The use of GRNs serves as an excellent tool to identify and rank interacting genes as candidates for oligogenic inheritance and identification of genetic modifiers. Moreover, correcting signaling dosage across a relevant GRN, rather than targeting a single pathogenic variant, may be a promising approach for future therapeutic strategies.

Figure 2. Molecular genetic mechanisms underlying CHD.

Chromosomal aberrations, disrupted chromatin organization, altered epigenetic mechanisms, environmental factors and pathogenic variation represent identified mechanisms for CHD. Additional molecular etiologies for CHD pathogenesis are shown (where TBX5 serves as a representative example) and include oligogenic inheritance of variation in both TBX5 and MEF2C, which represent interconnected nodes in a gene regulatory network, and pathogenic variation in noncoding elements regulating TBX5. The schematic also represents how a subset of these factors could interact in a multifactorial manner to cause CHD. Created with Biorender.com.

5. Summary

While the widespread application of NGS has led to the rapid discovery of many CHD-contributing genes, it has become increasingly apparent that a large fraction of CHD does not have a monogenic etiology that is the result of coding variation. Rather, far more complex etiologies that involve oligogenic inheritance, genetic mosaicism, variation in noncoding elements, interactions with environmental teratogens or their combinations play critical roles. Moreover, vulnerable genes within a regulatory network represent candidates for oligogenic inheritance as co-inheritance of otherwise ‘benign’ sequence variation can greatly affect the interacting network, resulting in decreased signaling dosage of associated molecular and cellular pathways. Continued application of deep resolution multi-omics approaches will be key to uncovering the complex, genetic mechanisms underpinning CHD and progression toward translational approaches that reduce the incidence of CHD.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding support from NIH/NHLBI R01 HL144009 and R21 HL161823 to V.G. and the use of Biorender.com for generation of figures.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, Boehme AK, Buxton AE, Carson AP, Commodore-Mensah Y, et al. : Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022:Cir0000000000001052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khairy P, Ionescu-Ittu R, Mackie AS, Abrahamowicz M, Pilote L, Marelli AJ: Changing mortality in congenital heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2010, 56:1149–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vatta M: Genetic Testing for Congenital Heart Disease: the Future is now. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raissadati A, Nieminen H, Jokinen E, Sairanen H: Progress in late results among pediatric cardiac surgery patients: a population-based 6-decade study with 98% follow-up. Circulation 2015, 131:347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierpont ME, Brueckner M, Chung WK, Garg V, Lacro RV, McGuire AL, Mital S, Priest JR, Pu WT, Roberts A: Genetic basis for congenital heart disease: revisited: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 138:e653–e711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerrone M, Remme CA, Tadros R, Bezzina CR, Delmar M: Beyond the one gene–one disease paradigm: complex genetics and pleiotropy in inheritable cardiac disorders. Circulation 2019, 140:595–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yasuhara J, Garg V: Genetics of congenital heart disease: a narrative review of recent advances and clinical implications. Translational Pediatrics 2021, 10:2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majumdar U, Yasuhara J, Garg V: In vivo and in vitro genetic models of congenital heart disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2021, 13:a036764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meilhac SM, Buckingham ME: The deployment of cell lineages that form the mammalian heart. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2018, 15:705–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houyel L, Meilhac SM: Heart Development and Congenital Structural Heart Defects. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 2021, 22: 257–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyser RC, Ibarra-Soria X, McDole K, Jayaram SA, Godwin J, van den Brand TA, Miranda AM, Scialdone A, Keller PJ, Marioni JC: Characterization of a common progenitor pool of the epicardium and myocardium. Science 2021, 371:eabb2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Q, Carlin D, Zhu F, Cattaneo P, Ideker T, Evans SM, Bloomekatz J, Chi NC: Unveiling complexity and multipotentiality of early heart fields. Circulation Research 2021, 129:474–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lescroart F, Wang X, Lin X, Swedlund B, Gargouri S, Sànchez-Dànes A, Moignard V, Dubois C, Paulissen C, Kinston S: Defining the earliest step of cardiovascular lineage segregation by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 2018, 359:1177–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *14.de Soysa TY, Ranade SS, Okawa S, Ravichandran S, Huang Y, Salunga HT, Schricker A, Del Sol A, Gifford CA, Srivastava D: Single-cell analysis of cardiogenesis reveals basis for organ-level developmental defects. Nature 2019, 572:120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Single cell RNA sequencing of >36,000 cells from distinct cardiogenic regions in mouse at early developmental timepoints (E7.75, E8.25, E9.25) revealed transcriptional determinants specifying fate and differentiation of cardiac progenitor cells including role of Hand2 in outflow tract specification and described how regulatory defects in discrete cell populations can lead to CHD.

- **15.Cui Y, Zheng Y, Liu X, Yan L, Fan X, Yong J, Hu Y, Dong J, Li Q, Wu X: Single-cell transcriptome analysis maps the developmental track of the human heart. Cell Reports 2019, 26:1934–1950. e1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Single cell RNA sequencing of ~4000 cardiac cells from 18 human embryos at 5–25 weeks of gestation led to transcriptomic mapping of the human fetal heart and comparative analysis with mouse sequencing data led to identification of human-specific marker genes for discrete cardiac cell populations.

- 16.Sahara M, Santoro F, Sohlmér J, Zhou C, Witman N, Leung CY, Mononen M, Bylund K, Gruber P, Chien KR: Population and single-cell analysis of human cardiogenesis reveals unique LGR5 ventricular progenitors in embryonic outflow tract. Developmental Cell 2019, 48:475–490. e477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mononen MM, Leung CY, Xu J, Chien KR: Trajectory mapping of human embryonic stem cell cardiogenesis reveals lineage branch points and an ISL1 progenitor‐derived cardiac fibroblast lineage. Stem Cells 2020, 38:1267–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone NR, Gifford CA, Thomas R, Pratt KJ, Samse-Knapp K, Mohamed TM, Radzinsky EM, Schricker A, Ye L, Yu P: Context-specific transcription factor functions regulate epigenomic and transcriptional dynamics during cardiac reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 25:87–102. e109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miao Y, Tian L, Martin M, Paige SL, Galdos FX, Li J, Klein A, Zhang H, Ma N, Wei Y: Intrinsic endocardial defects contribute to hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27:574–589. e578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofbauer P, Jahnel SM, Papai N, Giesshammer M, Deyett A, Schmidt C, Penc M, Tavernini K, Grdseloff N, Meledeth C: Cardioids reveal self-organizing principles of human cardiogenesis. Cell 2021: 12:3299–3317.e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orlova VV, Mummery CL: Heart defects recapitulated in human cardioids. Cell Research 2021, 31:947–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srivastava D: Modeling Human Cardiac Chambers with Organoids. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 385:847–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin H, McBride KL, Garg V, Zhao M-T: Decoding genetics of congenital heart disease using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitani T, Tian L, Zhang T, Itzhaki I, Zhang JZ, Ma N, Liu C, Rhee J-W, Romfh AW, Lui GK: RNA sequencing analysis of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes from congenital heart disease patients. Circulation Research 2020, 126:923–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diab NS, Barish S, Dong W, Zhao S, Allington G, Yu X, Kahle KT, Brueckner M, Jin SC: Molecular genetics and complex inheritance of congenital heart disease. Genes 2021, 12:1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin AE, Santoro S, High FA, Goldenberg P, Gutmark‐Little I: Congenital heart defects associated with aneuploidy syndromes: New insights into familiar associations. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics 2020, 184:53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rice AM, McLysaght A: Dosage sensitivity is a major determinant of human copy number variant pathogenicity. Nature Communications 2017, 8:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thorsson T, Russell WW, El‐Kashlan N, Soemedi R, Levine J, Geisler SB, Ackley T, Tomita‐Mitchell A, Rosenfeld JA, Töpf A: Chromosomal imbalances in patients with congenital cardiac defects: a meta‐analysis reveals novel potential critical regions involved in heart development. Congenital Heart Disease 2015, 10:193–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fotiou E, Williams S, Martin-Geary A, Robertson DL, Tenin G, Hentges KE, Keavney B: Integration of large-scale genomic data sources with evolutionary history reveals novel genetic loci for congenital heart disease. Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine 2019, 12:e002694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morton SU, Quiat D, Seidman JG, Seidman CE: Genomic frontiers in congenital heart disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2021:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consortium PCG, Committee: W, Gelb B, Brueckner M, Chung W, Goldmuntz E, Kaltman J, Pablo Kaski J, Kim R, Kline J: The congenital heart disease genetic network study: rationale, design, and early results. Circulation Research 2013, 112:698–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoang TT, Goldmuntz E, Roberts AE, Chung WK, Kline JK, Deanfield JE, Giardini A, Aleman A, Gelb BD, Mac Neal M: The congenital heart disease genetic network study: cohort description. PloS One 2018, 13:e0191319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sifrim A, Hitz M-P, Wilsdon A, Breckpot J, Al Turki SH, Thienpont B, McRae J, Fitzgerald TW, Singh T, Swaminathan GJ: Distinct genetic architectures for syndromic and nonsyndromic congenital heart defects identified by exome sequencing. Nature Genetics 2016, 48:1060–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Homsy J, Zaidi S, Shen Y, Ware JS, Samocha KE, Karczewski KJ, DePalma SR, McKean D, Wakimoto H, Gorham J: De novo mutations in congenital heart disease with neurodevelopmental and other congenital anomalies. Science 2015, 350:1262–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin SC, Homsy J, Zaidi S, Lu Q, Morton S, DePalma SR, Zeng X, Qi H, Chang W, Sierant MC: Contribution of rare inherited and de novo variants in 2,871 congenital heart disease probands. Nature Genetics 2017, 49:1593–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watkins WS, Hernandez EJ, Wesolowski S, Bisgrove BW, Sunderland RT, Lin E, Lemmon G, Demarest BL, Miller TA, Bernstein D: De novo and recessive forms of congenital heart disease have distinct genetic and phenotypic landscapes. Nature Communications 2019, 10:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LaHaye S, Corsmeier D, Basu M, Bowman JL, Fitzgerald-Butt S, Zender G, Bosse K, McBride KL, White P, Garg V: Utilization of whole exome sequencing to identify causative mutations in familial congenital heart disease. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics 2016, 9:320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zahavich L, Bowdin S, Mital S: Use of clinical exome sequencing in isolated congenital heart disease. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics 2017, 10:e001581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Priest JR, Osoegawa K, Mohammed N, Nanda V, Kundu R, Schultz K, Lammer EJ, Girirajan S, Scheetz T, Waggott D: De novo and rare variants at multiple loci support the oligogenic origins of atrioventricular septal heart defects. PLoS Genetics 2016, 12:e1005963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alankarage D, Ip E, Szot JO, Munro J, Blue GM, Harrison K, Cuny H, Enriquez A, Troup M, Humphreys DT: Identification of clinically actionable variants from genome sequencing of families with congenital heart disease. Genetics in Medicine 2019, 21:1111–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu S, Chen W, Zhan Y, Li S, Ma X, Ma D, Sheng W, Huang G: DNAH11 variants and its association with congenital heart disease and heterotaxy syndrome. Scientific reports 2019, 9:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cuvertino S, Hartill V, Colyer A, Garner T, Nair N, Al-Gazali L, Canham N, Faundes V, Flinter F, Hertecant J: A restricted spectrum of missense KMT2D variants cause a multiple malformations disorder distinct from Kabuki syndrome. Genetics in Medicine 2020, 22:867–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *43.Edwards JJ, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Wang Z, Lachmann A, Shankaran SS, Bisgrove BW, Demarest B, Turan N, Srivastava D: Systems Analysis Implicates WAVE2 Complex in the Pathogenesis of Developmental Left-Sided Obstructive Heart Defects. JACC Basic to Translational Science 2020, 5:376–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Unbiased global analysis of WES from 2,881 probands with sporadic severe CHD followed by complementary knockdown studies in zebrafish identified novel role of WAVE2 complex proteins and regulators of GTPase signaling in cardiac development.

- 44.Page DJ, Miossec MJ, Williams SG, Monaghan RM, Fotiou E, Cordell HJ, Sutcliffe L, Topf A, Bourgey M, Bourque G: Whole exome sequencing reveals the major genetic contributors to nonsyndromic tetralogy of Fallot. Circulation Research 2019, 124:553–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manshaei R, Merico D, Reuter MS, Engchuan W, Mojarad BA, Chaturvedi R, Heung T, Pellecchia G, Zarrei M, Nalpathamkalam T: Genes and pathways implicated in tetralogy of Fallot revealed by ultra-rare variant burden analysis in 231 genome sequences. Frontiers in Genetics 2020, 11:957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reuter MS, Jobling R, Chaturvedi RR, Manshaei R, Costain G, Heung T, Curtis M, Hosseini SM, Liston E, Lowther C: Haploinsufficiency of vascular endothelial growth factor related signaling genes is associated with tetralogy of Fallot. Genetics in Medicine 2019, 21:1001–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **47.Gifford CA, Ranade SS, Samarakoon R, Salunga HT, De Soysa TY, Huang Y, Zhou P, Elfenbein A, Wyman SK, Bui YK: Oligogenic inheritance of a human heart disease involving a genetic modifier. Science 2019, 364:865–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Identified missense variation in MYH7, MKL2 and NKX2–5 in members of a family affected by left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy and further analysis using CRISPR-Cas gene editing in mice revealed the role of NKX2–5 as a genetic modifier that works in conjunction with MKL2 and MYH7 variants for disease manifestation.

- 48.Kong JH, Young CB, Pusapati GV, Patel CB, Ho S, Krishnan A, Lin J-HI, Devine W, de Bellaing AM, Athni TS: A membrane-tethered ubiquitination pathway regulates Hedgehog signaling and heart development. Developmental Cell 2020, 55:432–449. e412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blue GM, Mekel M, Das D, Troup M, Rath E, Ip E, Gudkov M, Perumal G, Harvey RP, Sholler GF: Whole genome sequencing in transposition of the great arteries and associations with clinically relevant heart, brain and laterality genes.: WGS in transposition of the great arteries. American Heart Journal 2022, 244:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis CM, Vassos E: Polygenic risk scores: from research tools to clinical instruments. Genome Medicine 2020, 12:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manheimer KB, Richter F, Edelmann LJ, D’Souza SL, Shi L, Shen Y, Homsy J, Boskovski MT, Tai AC, Gorham J: Robust identification of mosaic variants in congenital heart disease. Human Genetics 2018, 137:183–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *52.Hsieh A, Morton SU, Willcox JA, Gorham JM, Tai AC, Qi H, DePalma S, McKean D, Griffin E, Manheimer KB: EM-mosaic detects mosaic point mutations that contribute to congenital heart disease. Genome Medicine 2020, 12:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Whole exome squencing from 2,530 CHD proband trios were subjected to a novel computational analysis for mosaic detection and revealed 1% of the CHD cohort had a detectable mosaic variant that may contribute to CHD.

- 53.Smemo S, Campos LC, Moskowitz IP, Krieger JE, Pereira AC, Nobrega MA: Regulatory variation in a TBX5 enhancer leads to isolated congenital heart disease. Human Molecular Genetics 2012, 21:3255–3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chahal G, Tyagi S, Ramialison M: Navigating the non-coding genome in heart development and Congenital Heart Disease. Differentiation 2019, 107:11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *55.Richter F, Morton SU, Kim SW, Kitaygorodsky A, Wasson LK, Chen KM, Zhou J, Qi H, Patel N, DePalma SR: Genomic analyses implicate noncoding de novo variants in congenital heart disease. Nature Genetics 2020, 52:769–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Whole genome sequencing of 749 CHD proband trios followed by neural network prediction revealed de novo mutations in fetal heart enhancers, 31 of which were functionally tested in human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and 5 of which led to significantly altered transcription of CHD genes.

- 56.Nora JJ: Multifactorial inheritance hypothesis for the etiology of congenital heart diseases: the genetic-environmental interaction. Circulation 1968, 38:604–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Basu M, Zhu J-Y, LaHaye S, Majumdar U, Jiao K, Han Z, Garg V: Epigenetic mechanisms underlying maternal diabetes-associated risk of congenital heart disease. JCI insight 2017, 2:e95085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chapman G, Moreau JL, Ip E, Szot JO, Iyer KR, Shi H, Yam MX, O’Reilly VC, Enriquez A, Greasby JA: Functional genomics and gene-environment interaction highlight the complexity of congenital heart disease caused by Notch pathway variants. Human Molecular Genetics 2020, 29:566–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harvey DC, De Zoysa P, Toubat O, Choi J, Kishore J, Tsukamoto H, Kumar SR: Concomitant genetic defects potentiate the adverse impact of prenatal alcohol exposure on cardiac outflow tract maturation. Birth Defects Research 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu C-X, Wang W, Wang Q, Liu X-Y, Yang Y-Q: A novel MEF2C loss-of-function mutation associated with congenital double outlet right ventricle. Pediatric cardiology 2018, 39:794–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *61.Sharma A, Wasson LK, Willcox JA, Morton SU, Gorham JM, DeLaughter DM, Neyazi M, Schmid M, Agarwal R, Jang MY: GATA6 mutations in hiPSCs inform mechanisms for maldevelopment of the heart, pancreas, and diaphragm. Elife 2020, 9:e53278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Study described the effects of damaging GATA6 variants on the cardiac gene program during human iPSC differentiation to cardiomyocytes and revealed disrupted molecular programs that cause abnormal development of the cardiac outflow tract, pancreas and diaphragm.

- **62.Kathiriya IS, Rao KS, Iacono G, Devine WP, Blair AP, Hota SK, Lai MH, Garay BI, Thomas R, Gong HZ: Modeling human TBX5 haploinsufficiency predicts regulatory networks for congenital heart disease. Developmental Cell 2021, 56:292–309. e299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Described the genetic dosage effect of TBX5 on the cardiac gene network during cardiomyocyte differentiation from human iPSC using scRNA-seq and identified a gene-gene interaction between Tbx5 and Mef2c in mice which led to highly penetrant ventricular septal defects, serving as candidates for oligogenic inheritance of CHD.

- 63.Reuter MS, Chaturvedi RR, Jobling RK, Pellecchia G, Hamdan O, Sung WW, Nalpathamkalam T, Attaluri P, Silversides CK, Wald RM: Clinical genetic risk variants inform a functional protein interaction network for tetralogy of Fallot. Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine 2021, 14:e003410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *64.Ward T, Tai W, Morton S, Impens F, Van Damme P, Van Haver D, Timmerman E, Venturini G, Zhang K, Jang MY: Mechanisms of congenital heart disease caused by NAA15 haploinsufficiency. Circulation Research 2021, 128:1156–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; By following NAA15 haploinsufficient and null human iPSC differentiation to cardiomyocytes, the study described the effect of reduced NAA15 dosage in maintaining steady state levels of 562 proteins, 4 of which were previously identified CHD genes.

- 65.Liu X, Yagi H, Saeed S, Bais AS, Gabriel GC, Chen Z, Peterson KA, Li Y, Schwartz MC, Reynolds WT: The complex genetics of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Nature Genetics 2017, 49:1152–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.D’Gama AM, Walsh CA: Somatic mosaicism and neurodevelopmental disease. Nature Neuroscience 2018, 21:1504–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rauen KA: The RASopathies. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 2013, 14:355–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]