Abstract

Background:

Metastatic head and neck cancers (HNCs) predominantly affect the lungs and have a two-year overall survival (OS) of 15% to 50%, if amenable for pulmonary metastasectomy.

Methods:

Retrospective review of the two-year local control (LC), local-regional control (LRC) within the same lobe, OS, and toxicity rates in consecutive patients with metastatic pulmonary HNC who underwent stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) January 2007 to May 2018.

Results:

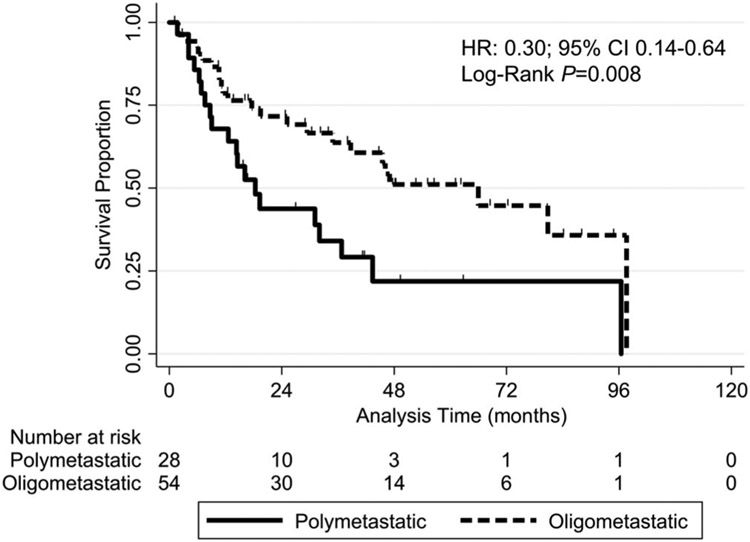

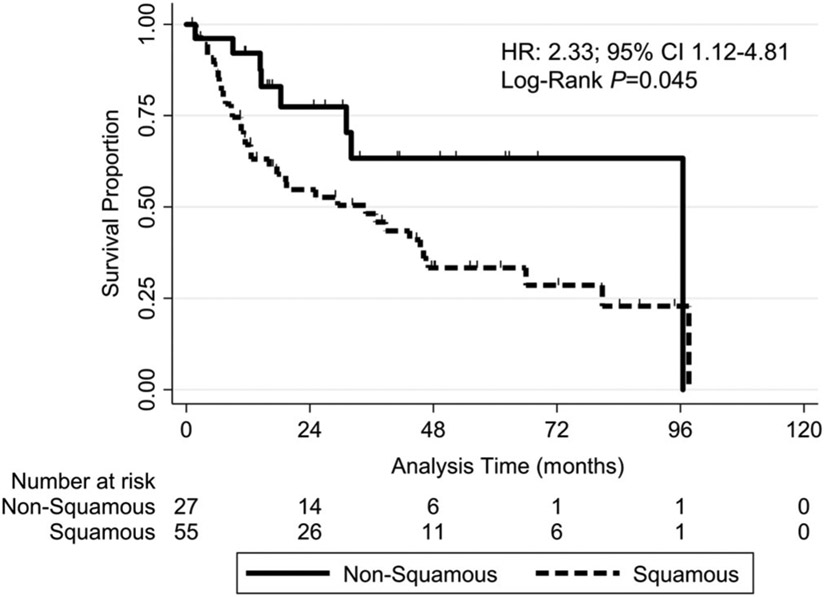

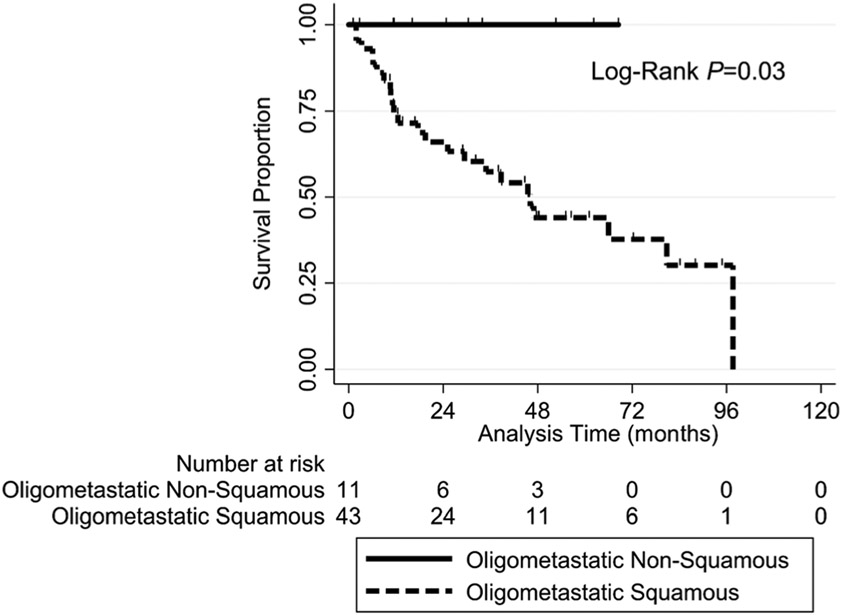

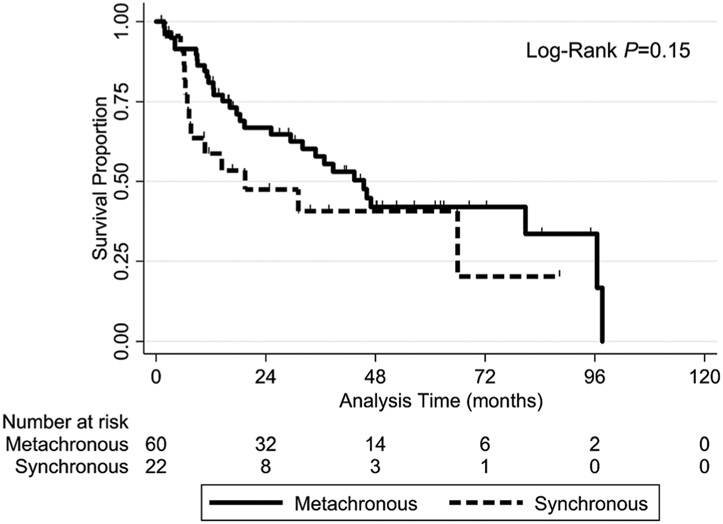

Evaluated 82 patients with 107 lung lesions, most commonly squamous cell carcinoma (SCO; 64%). Median follow-up was 20 months (range: 9.0-97.6). Systemic therapy administered in 34%. LC, LRC, and OS rates were 94%, 90%, and 62%. Patients with oligometastatic disease had a higher OS than polymetastatic disease, 72% vs 44% (HR = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.14-0.64; P = .008). OS in oligometastatic non-SCC and SCC were 100% and 66% (P = .03). There were no grade ≥3 toxicities.

Conclusions:

Metastatic pulmonary HNCs after SABR have a two-year OS rate comparable to pulmonary metastasectomy.

Keywords: oligometastasis, pulmonary metastases, pulmonary oligometastases, squamous cell carcinoma, stereotactic body radiotherapy

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Although the majority of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) head and neck cancer (HNC) cases are local-regional at initial presentation, distant metastatic disease (DMD) has been observed in 14% to 47% of patients and typically signifies a poor prognosis with a median overall survival (OS) of seven to ten months.1-5 Given a rising incidence of thyroid carcinoma and human papillomavirus (HPV) associated oropharyngeal SCC, HNCs are poised to become more burdensome to the healthcare system.6,7 Particularly among HPV-positive SCCs, there is a growing concern for delayed-onset metastasis wherein DMD can occur as late as six years after diagnosis.8 Similarly in thyroid carcinoma, recent epidemiologic studies have demonstrated an increasing incidence of DMD.9 Considering that the lung is the most common metastatic site for HNC, affecting 70% to 80% of patients with distant metastases, understanding the treatment options, and outcomes for this subset of patients is an increasingly important topic.1,2

Local therapy may still be an option for patients with limited DMD (ie, oligometastatic) in light of an emerging body of evidence.10 Historically, the surgical community has selected these types of patients for pulmonary metastasectomy, which resulted in high OS rates and delayed disease progression.11,12 Alternatively, stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy (SABR; also known as SBRT) has emerged as a local treatment option for patients with oligometastatic disease, with evidence from randomized trials demonstrating higher progression-free survival rates and longer OS durations than with systemic therapy alone.13-15 However, HNC patients were severely under-represented in those trials, and the literature, even reports of retrospective studies, is scarce.16

We report herein on the outcomes, disease control rates, and toxicities associated with treating pulmonary metastases using SABR in patients with primary HNCs. We hypothesized that SABR would have OS rates that are comparable to historic pulmonary metastasectomy.

2 ∣. METHODS

2.1 ∣. Patients

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective review. We identified 340 consecutive patients with pulmonary metastases who were treated with SABR from January 2007 to May 2018 using an institutional data analytics search. We then cross-referenced these patients to identify ones with a history of a primary HNC. The cohort of interest was defined by searching the institutional data warehouse for patients who received treatment under billing codes consistent with SABR (CPT codes 77373 and 77386) in association with specific International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnosis codes selected to reflect pulmonary metastatic disease (ICD C78.01 and C78.02, ICD9: C197, and ICD-O: C43.9). Additional patient level demographic information was further extracted via the institutional data warehouse, while specific treatment and outcome-related data were obtained using the MOSAIQ (Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden) and Epic (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, Wisconsin) electronic health record systems.

All patients received standard-of-care treatment of primary HNC (eg, external beam radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy, surgical resection with or without postoperative radiation therapy, induction chemotherapy followed by local therapy). The primary tumors were staged using the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual, Seventh Edition. Pulmonary metastases were treated with SABR as opposed to surgery due to a number of factors, including medical comorbidities, poor performance status, metastatic disease burden, limited pulmonary reserve, inoperable disease, and/or previous surgery with a short disease-free interval. Patients received SABR alone without concurrent administration of systemic agents. Adjuvant systemic therapy (chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or targeted therapy administered within six months of completing radiation therapy) was given at the treating medical oncologist's discretion.

Pre-SABR treatment evaluations were completed in all patients. The evaluations included a physical examination and chest imaging using computed tomography (CT) with contrast and/or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT. Endobronchial ultrasound with lymph node biopsy analysis was completed in patients with chest imaging suspicious for intrathoracic lymphadenopathy or pulmonary disease clinically worrisome for primary lung cancer. Patients were designated as having oligometastatic disease if they had no active extra-thoracic disease, and up to three pulmonary metastases on the most recent chest imaging prior to the SABR start date and all of their lung lesions were treated with SABR. If patients did not meet these criteria, they were considered to have polymetastatic disease. Lung lesions were defined as metachronous if diagnosed via imaging and/or biopsy more than three months after treatment of the primary HNC, a definition used in prior series.16

2.2 ∣. Treatment planning and delivery

A fixed stereotactic Vac-Lok device (CIVCO, Coralville, Iowa) was used to immobilize patients, and four-dimensional CT scans were obtained most commonly using a free-breathing technique. A breath-hold technique was only used for patients with tumor motion greater than 1 cm. The gross tumor volume was delineated during each respiratory phase of four-dimensional CT to generate the internal target volume (ITV). The ITV was expanded uniformly by 5 mm to generate the planning target volume (PTV). Organs at risk (eg, lung parenchyma, heart, spinal cord, esophagus, brachial plexus, chest wall, central blood vessels, bronchial tree) were delineated to minimize the radiation dose as determined by each clinician. Peripheral lesions were most commonly treated using 50 Gy delivered in four fractions, whereas central lesions were treated using 70 Gy delivered in ten fractions, a fractionation scheme that has been used routinely and effectively for primary lung cancer.17 Daily cone-beam CT images and orthogonal megavoltage images were used to verify patient setup and shifts. Treatment plans were normalized according to the mean dose to the PTV and all plans were reviewed for quality assurance.

2.3 ∣. Follow-up

Every three to six months after SABR, patients routinely underwent physical examinations and chest imaging using CT and/or PET-CT. Recurrences were identified radiographically, and biopsy was performed only at the clinician's discretion. Radiographic recurrences were scored by two radiologists specializing in thoracic oncology using the revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors guidelines (version 1.1) plus PET-CT, if available, for confirmation. Recurrences were then reviewed and confirmed by two radiation oncologists.18

Local failure of treated pulmonary metastases was defined as progression within the 50% isodose line of the initial treatment. Regional failure was defined as progression outside the 50% isodose line of the initial treatment but within the same lobe of the lung. Intrathoracic distant failure was defined as progression in the contralateral and/or ipsilateral lung but a different lobe. The study patients' local control (LC), regional control within the same lobe (RC), local-regional control (LRC), and intrathoracic distant control (IDC) rates were analyzed. OS was defined as the time from the start of radiation treatment to that of death due to any cause. Toxicity was assessed using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0).

2.4 ∣. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the Stata/MP software program (version 15.1; StataCorp, College Station, Texas). P values less than .05 were considered significant, and statistical tests were based on a two-sided significance level. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test or a χ test was used to determine differences in patient characteristics and stratification criteria between treatment groups. Kaplan-Meier analyses were used to assess LC, RC, LRC, IDC, and OS over time. LC, RC, LRC, and IDC were evaluated on a per lesion basis while OS was evaluated on a per patient basis using a log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was used for univariate and multivariable analysis. Univariate factors with P values of up to .25 were included in the multivariable analysis and then eliminated in a stepwise manner until the most significant variables were identified. The Wald test was used to assess the role of covariates in the model. LC alone was not assessed using the Cox proportional hazards model due to too few events. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were done to evaluate factors significantly associated with administration of systemic therapy after SABR.

3 ∣. RESULTS

3.1 ∣. Entire cohort

This study included 82 patients with 107 pulmonary lesions treated using SABR from January 2007 to May 2018. The median follow-up time was 20 months (range, 9.0-97.6 months) in all patients and 34 months (range, 9.0-94.9 months) in patients alive as of July 2019. The median time from the end of treatment of the primary HNC to the start of SABR was 29 months (range, 0-212 months).

Table 1 summarizes the patient, lung lesion, and treatment characteristics. Histopathologic confirmation of lung lesions was completed in 72 patients (88%). All patients had a lung lesion histology concordant with that of the primary HNC. SCC was the most common histologic subtype, observed in 55 patients (67%) and 68 lung lesions (64%). However, definitively determining whether these SCC lung lesions represented a primary lung cancer or metastatic disease was not feasible given the limitations of modern histopathologic techniques.19,20 The majority of the patients were male (79%) and white (83%), with a median age at the start of SABR treatment of 65 years (range, 26-93 years). The histologic subtypes include SCC (64%), papillary thyroid carcinoma (14%), adenoid cystic carcinoma (9%), sarcoma (4%), adenocarcinoma (3%), follicular thyroid carcinoma (3%), salivary duct carcinoma (3%), and neuroendocrine carcinoma (1%). The patients with sarcoma histology had tumors with a sarcomatoid or sarcomatoid carcinoma appearance. We thus classified these tumors as sarcomas and included the patients in this analysis and none of these patients experienced a local failure. The sites of primary HNC included the oropharynx (29%), oral cavity (17%), thyroid gland (17%), larynx (15%), skin (7%), salivary gland (5%), hypopharynx (5%), nasal cavity/paranasal sinus (4%), and nasopharynx (1%).

TABLE 1.

Patient, lung lesion, and treatment characteristics

| Characteristic value or no. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Total no. of patients | 82 (100) |

| Median age at start of radiation, years (range) | 65 (26–93) |

| Male | 65 (79.2) |

| Ethnicity/race | |

| Caucasian | 68 (82.9) |

| Hispanic | 9 (11.0) |

| African American | 4 (4.9) |

| Asian | 1 (1.2) |

| History of smoking | 52 (63.4) |

| Smoked during radiation treatment | 13 (15.9) |

| Pathologically confirmed lung metastasis | 72 (87.8) |

| History of smoking | 47 (57.3) |

| Nonpathologically confirmed lung metastasis | 10 (12.2) |

| History of smoking | 5 (6.1) |

| Primary tumor location | |

| Oropharynx | 24 (29.3) |

| Oral cavity | 14 (17.1) |

| Thyroid | 14 (17.1) |

| Larynx | 12 (14.6) |

| Skin of head and neck | 6 (7.3) |

| Hypopharynx | 4 (4.9) |

| Salivary gland | 4 (3.7) |

| Sinus | 2 (2.4) |

| Nasal cavity | 1 (1.2) |

| Nasopharynx | 1 (1.2) |

| AJCC seventh edition tumor classification | |

| T1 | 9 (11.0) |

| T2 | 22 (26.8) |

| T3 | 29 (35.4) |

| T4 | 22 (26.8) |

| AJCC seventh edition nodal classification | |

| N0 | 30 (36.6) |

| N1 | 20 (24.4) |

| N2 | 32 (39.0) |

| Total no. of metastases | 107 (100) |

| Pathology/histologic subtype | |

| Squamous cell | 68 (63.6) |

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma | 15 (14.0) |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 10 (9.3) |

| Sarcoma | 4 (3.7) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 3 (2.8) |

| Follicular thyroid carcinoma | 3 (2.8) |

| Salivary duct carcinoma | 3 (2.8) |

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 1 (0.9) |

| Pathology/histologic grouping | |

| Squamous cell | 68 (63.6) |

| Nonsquamous cell | 39 (36.4) |

| Oligometastatica | |

| Yes | 73 (68.2) |

| No | 34 (31.8) |

| Metastasis timing | |

| Metachronousb | 84 (78.5) |

| Synchronous | 23 (21.5) |

| Adjuvant systemic therapy | |

| Yes | 36 (33.6) |

| No | 71 (66.4) |

| Laterality | |

| Left lower lobe | 21 (19.6) |

| Left upper lobe | 27 (25.2) |

| Right lower lobe | 22 (20.6) |

| Right middle lobe | 5 (4.7) |

| Right upper lobe | 32 (29.9) |

| Median gross tumor volume, cm3 (range) | 3.6 (0.5-63.9) |

| Dose, Gy/fraction number | |

| 70/10 | 21 (19.6) |

| 54/3 | 5 (4.7) |

| 48/3 | 1 (0.9) |

| 50/4 | 79 (73.8) |

| 62.5/5 | 1 (0.9) |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; Gy, Gray; no., number.

Oligometastatic disease was defined as up to three lung lesions, all of which were treated with SABR.

Metachronous disease was defined as that diagnosed more than three months after treatment of primary HNC.

Among all the patients who underwent SABR, the one-year OS, LC, LRC, and IDC rates were 74.8%, 97.8%, 93.6%, and 81.5%, respectively, and the two-year OS, LC, LRC, and IDC rates were 61.6%, 94.4%, 90.3%, and 72.5%, respectively (Table 2). The median OS duration was 43 months. Adjuvant systemic therapy was not commonly administered (only after SABR for 36 of 107 lung lesions), but those who did receive it had significantly worse OS (log-rank P = .01) and IDC (log-rank P = .005) rates than patients who did not receive it (Table 2). Adjuvant systemic therapy was more frequently delivered to patients in the polymetastatic (62%) group than in the oligometastatic (21%) group (Table 3). On multivariable logistic regression modeling (Table A1), the only factor significantly associated with the use of adjuvant systemic therapy was the use of SABR to all sites of pulmonary lesions (complete consolidation of disease) vs only partial consolidation with SABR (odds ratio = 0.06, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.02-0.22; P < .001).

TABLE 2.

Summary of Kaplan-Meier analysis of patient outcomes at 12 and 24 months stratified according to different variables

| Total number of at-risk lung lesions |

Total number of at-risk patients |

% | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS |

LC |

LRC |

IDC |

|||||||

| 12 mo | 24 mo | 12 mo | 24 mo | 12 mo | 24 mo | 12 mo | 24 mo | |||

| All lung lesions | 107 | 82 | 74.8 | 61.6 | 97.8 | 94.4 | 93.6 | 90.3 | 81.5 | 72.5 |

| Polymetastatic | 34 | 28 | 67.9 | 43.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 74.7 | 65.6 |

| Oligometastaticb | 73 | 54 | 78.6 | 71.6 | 96.8 | 92.3 | 90.7 | 86.3 | 84.7 | 76.1 |

| P value (log-rank test) | — | — | 0.008 | NS | 0.05 | NS | ||||

| Non-SCC | 39 | 27 | 92.2 | 77.4 | 100 | 100 | 97.0 | 97.0 | 79.0 | 75.2 |

| SCC | 68 | 55 | 67.0 | 54.7 | 96.6 | 91.1 | 90.1 | 80.2 | 82.8 | 70.8 |

| P value (log-rank test) | — | — | 0.04 | NS | NS | NS | ||||

| Oligometastatic + Non-SCC | 11 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 78.6 | 78.6 |

| Oligometastatic + SCC | 43 | 43 | 74.1 | 66.0 | 95.9 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 84.2 | 86.1 | 75.0 |

| P value (log-rank test) | — | — | 0.03 | NS | NS | NS | ||||

| Metachronousa | 84 | 60 | 80.9 | 66.9 | 98.5 | 94.4 | 94.5 | 90.5 | 82.9 | 71.8 |

| Synchronousb | 23 | 22 | 58.7 | 47.5 | 95.4 | 95.4 | 90.9 | 90.9 | 77.4 | 77.4 |

| P value (log-rank test) | — | — | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||||

| No adjuvant systemic therapy | 71 | 56 | 72.5 | 65.7 | 98.2 | 95.9 | 95.0 | 92.7 | 87.5 | 80.6 |

| Adjuvant systemic therapy | 36 | 26 | 80.0 | 52.7 | 97.0 | 91.3 | 90.9 | 85.2 | 69.5 | 56.9 |

| P value (log-rank test) | — | — | 0.01 | NS | NS | 0.005 | ||||

Abbreviations: IDC, intrathoracic distant control; LC, local control; LRC, local-regional control; Mo, months; NS, not significant; OS, overall survival; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Metachronous disease was defined as that diagnosed more than three months after treatment of primary HNC.

Oligometastatic disease was defined as up to three lung lesions, all of which were treated with SABR.

TABLE 3.

Lung lesion and treatment characteristics stratified by polymetastatic disease vs oligometastatic disease, nonsquamous cell carcinoma vs squamous cell carcinoma, and metachronous disease vs synchronous disease

| n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cases (n = 107) |

Polymetastatic disease (n = 34) |

Oligometastatic disease (n = 73) |

P | Non-SCC (n = 39) | SCC (n = 68) | P | Metachronous lesions (n = 84) |

Synchronous lesions (n = 23) |

P | |

| Median age, years (range) | 65 (26-93) | 67 (43-93) | 65 (26-83) | NS | 66 (26-93) | 65 (44-83) | NS | 66 (26-93) | 65 (44-83) | NS |

| Lung surgical history | NS | NS | NS | |||||||

| Any | 13 (12) | 4(12) | 9(12) | 8(20) | 5(7) | 9(11) | 4(17) | |||

| None | 94 (88) | 30 (88) | 64 (88) | 31(80) | 63 (93) | 75 (89) | 19 (83) | |||

| Histology | .002 | — | NS | |||||||

| Non-SCC | 39 (36) | 20 (59) | 19 (26) | — | — | 33 (39) | 6(26) | |||

| see | 68 (64) | 14 (41) | 54 (74) | — | — | 51(61) | 17 (74) | |||

| Oligometastatica | — | .002 | NS | |||||||

| Yes | 73 (68) | — | — | 19 (49) | 54 (79) | 57 (68) | 16 (70) | |||

| No | 34 (32) | — | — | 20 (51) | 14(21) | 27 (32) | 7(30) | |||

| Lung lesion timing | NS | NS | — | |||||||

| Metachronousb | 84 (79) | 27 (79) | 57 (78) | 33 (85) | 6(9) | — | — | |||

| Synchronous | 23 (21) | 7(21) | 16 (22) | 6(15) | 62 (91) | — | — | |||

| Adjuvant systemic therapy | <.001 | NS | NS | |||||||

| Yes | 36 (34) | 21(62) | 15(21) | 22 (56) | 49 (72) | 32 (38) | 4(17) | |||

| No | 71 (66) | 13 (38) | 58 (79) | 17 (44) | 19 (28) | 52 (62) | 19 (83) | |||

| Median GTV, cm3 (range) | 3.6 (0.5–63.9) | 4.15 (0.80-63.90) | 3.49 (0.50-37.80) | NS | 3.06 (0.80-16.90) | 4.03 (0.50-63.90) | NS | 3.4 (0.5-63.9) | 4.3 (0.7-33.1) NS | |

| Dose, Gy/fractions | NS | NS | NS | |||||||

| 70/10 | 21 (20) | 9 (26) | 12 (16) | 8 (21) | 13 (19) | 15 (18) | 6 (26) | |||

| 54/3 | 5 (5) | 1 (3) | 4 (5) | 2 (5) | 3 (4) | 4 (5) | 1 (4) | |||

| 48/3 | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | |||

| 50/4 | 79 (74) | 22 (65) | 57 (78) | 28 (72) | 51 (75) | 64 (76) | 15 (65) | |||

| 62.5/5 | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | |||

| Failure | ||||||||||

| Local | 4 (4) | 0 | 4 (5) | NS | 0 | 4 (6) | NS | 3 (4) | 1 (4) | NS |

| Regional | 5 (5) | 0 | 9 (12) | NS | 1 (3) | 8 (12) | NS | 4 (5) | 1 (4) | NS |

| Local-regional | 9 (8) | 0 | 9 (12) | NS | 1 (3) | 8 (12) | NS | 7 (8) | 2 (9) | NS |

| Intrathoracic distance | 28 (26) | 10 (29) | 18 (25) | NS | 8 (21) | 20 (29) | NS | 22 (26) | 6 (26) | NS |

| Median follow-up time, months | 19.4 | 15.8 | 29.1 | NS | 24.5 | 19.3 | NS | 27.7 | 12.8 | NS |

Abbreviations: GTV, gross tumor volume; Gy, Gray; IDC, intrathoracic distant control; LC, local control; LRC, local-regional control; Mo, months; NS, not significant; OS, overall survival; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Oligometastatic disease was defined as up to three lung lesions, all of which were treated with SABR.

Metachronous disease was defined as that diagnosed more than three months after treatment of primary HNC.

On Cox multivariable analysis of OS, significant factors included oligometastatic disease (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.14-0.64; P = .002), adjuvant systemic therapy (HR = 2.65, 95% CI: 1.21-5.81; P = .015), and any smoking history (HR = 4.46, 95% CI: 1.67-11.90; P = .003) as summarized in Table A2. On Cox multivariable regression analysis, factors significantly associated with an increased probability of IDC (Table A3) included nonwhite race/ethnicity (HR = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.03-0.98; P = .048) and T4 disease (HR = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.07-0.90; P = .033). No multivariable factors were associated with LRC (Table A4).

Of the 32 patients with primary oropharyngeal disease, 19 primary tumors (59.4%) underwent HPV and/or p16 testing, with 15 of 19 (78.9%) tests having positive results. When comparing patients with HPV and/or p16 positive vs negative disease, the median OS was 46 months (range: 8.9-88.1 months) vs 4 months (range: 1.9-10.7 months; log-rank P = .0003), respectively. There was one local failure in the HPV and/or p16 positive group and none in the negative group.

We also found no grade ≥3 toxicities (Table A5). The most common toxicity was pneumonitis, developing in 14 patients (17%), only 2 of which (2%) were grade 2 and required medical intervention. Chest wall pain was the second most common side effect, occurring in four patients (5%). There was one case of hemoptysis. Stratifying toxicities by oligometastatic or polymetastatic group did not demonstrate any differences (Table A6).

3.2 ∣. Oligometastatic vs polymetastatic disease

Out of the 82 patients, 65.8% (n = 54 of 82 patients) were classified as oligometastatic while 34.1% (n = 28 out of 82 patients) were polymetastatic. Patients classified as having oligometastatic (n = 73 of 107 lung lesions) and polymetastatic (n = 34 of 107 lung lesions) HNC were largely similar with respect to age, lung lesion timing (metachronous vs synchronous), and other factors as shown in Table 3. However, more patients had SCC histology in the oligometastatic group (74%) than in the polymetastatic group (41%; P = .002). Also, fewer patients received adjuvant systemic therapy in the oligometastatic group (21%) than in the polymetastatic group (62%; P < .001).

The two-year OS rate was significantly higher in patients with oligometastatic disease (71.6%) than in those with polymetastatic disease (43.8%; HR = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.14-0.64; log-rank P = .008) (Figure 1). In further subgroup analysis, the two-year OS rate was significantly higher in patients with oligometastatic non-SCC (100%) than in those with oligometastatic SCC (66%; log-rank P = .03) (Table 3, Figure A1). There was not a significant difference in LC, LRC, or IDC between the patients with oligometastatic and polymetastatic disease (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves for the study patients grouped according to oligometastatic disease (up to three lung lesions and consolidation of all lung lesions with stereotactic radiation) vs polymetastatic disease (more than three lung lesions and/or partial consolidation of lung lesions). The overall survival rate was significantly higher (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.30, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.14-0.64; Log-Rank P = .008) in the oligometastatic group (dashed line) than in the polymetastatic group (solid line) at 12 months (78.6% vs 67.9%), 24 months (71.6% vs 43.8%), and 36 months (63.7% vs 34.0%)

3.3 ∣. SCC vs non-SCC histology

More patients with a squamous cell histology (n = 68 of 107 lung lesions) than with a non-squamous cell histology (n = 39 of 107 lung lesions) had oligometastatic disease (79% and 49%, respectively; P = .002) and any smoking history (68% and 41%, respectively; P = .009) (Table 3). In addition, the OS rate was significantly lower in those with SCC than in those with a non-SCC (HR = 2.33, 95% CI: 1.12-4.81; P = .045) (Figure 2). The two-year OS rate was 54.7% in patients with SCC but 77.4% in those with non-SCC. LC, LRC, and IDC did not differ significantly in patients with SCC and non-SCC disease (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves for the study patients grouped according to squamous cell histology vs non-squamous cell histology (consisting of papillary thyroid, adenoid cystic, sarcoma, adenocarcinoma, follicular thyroid, salivary duct, and neuroendocrine cell origins). The overall survival rate was significantly lower (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.33, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.12-4.81; log-rank P = .045) in the squamous cell group (dashed line) than in the nonsquamous cell group (solid line) at 12 months (67.0% vs 92.2%), 24 months (54.7% vs 77.4%), and 36 months (48.2% vs 63.3%)

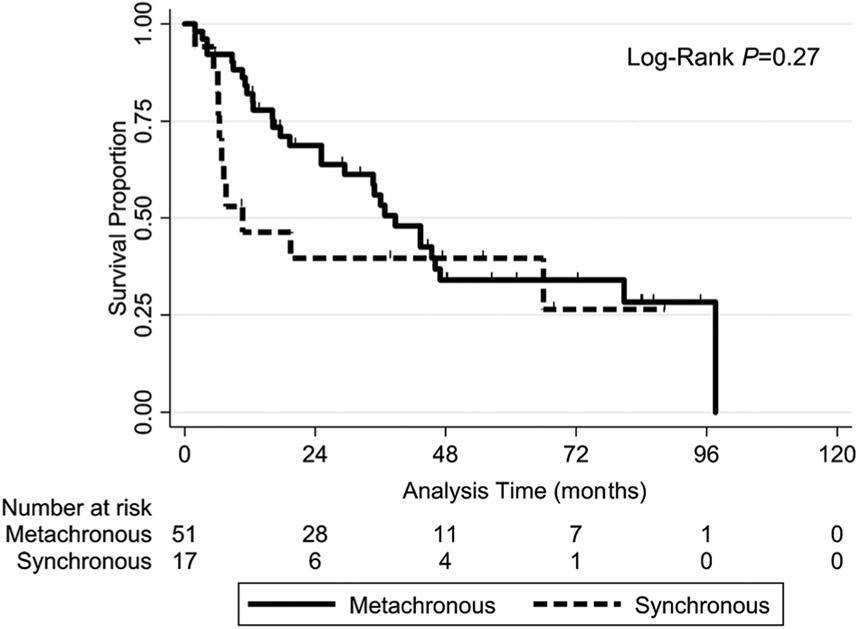

3.4 ∣. Metachronous vs synchronous HNC

Patients who had metachronous disease (n = 84 of 107 lung lesions) and those having synchronous disease (n = 23 of 107 lung lesions) were well balanced (ie, nonsignificant factors) as summarized in Table 3. LC, LRC, and IDC did not differ significantly in these patients according to SCC vs non-SCC histology (Table 2). The OS rate did not differ significantly differ in patients with metachronous or synchronous disease; neither in all cases (log-rank P = .12) (Figure A2) nor in SCC cases (log-rank P = .24) (Figure A3).

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

Our findings described herein represent the largest analysis of its kind in patients with HNC and associated lung lesions. We observed encouragingly high two-year LC (94%) and OS (63%) rates in all cases. In particular, the two-year OS rate for patients with SCC was 55%, which is on par with two-year OS rates after surgical metastasectomy.21 Moreover, the OS was considerably higher in patients with oligometastatic disease (72%) than in those with polymetastatic disease (44%). Whether the lung metastases developed early (synchronous) or late (metachronous) did not appear to impact OS. We found that SABR is a safe treatment option for metastatic HNC given that we observed no grade ≥3 toxicities.

4.1 ∣. Local control

The two-year LC rate in all of the study patients was excellent (94%). In SCC cases, which consisted of patients with lung metastases or primary non-small cell lung cancer, the LC rate was 91%, a value similar to the 90% LC rate after SABR for primary lung cancer reported previously.22 This LC rate, and even our LRC rate, were far better than the two-year LC rate of 57% in the only other reported study of SABR for metastatic head and neck SCC.16 In that study, Bates et al. reported that 73% of the metastases were in the lung; however, the authors noted they did not observe a difference in control of their lung lesions compared with non-lung lesions.

4.2 ∣. Overall survival

Among all patients, the two-year OS rate (62%) and median OS duration (43 months) were favorable. Also, the two-year OS rate was substantially better for oligometastatic than for polymetastatic HNC (72% and 44%, respectively). This was true despite the oligometastatic group having more high-risk features, including worse LRC and more SCCs. Overall, multivariable factors associated with poor OS included polymetastatic disease, smoking history, and receipt of adjuvant systemic therapy. Although the distinction between oligometastatic and polymetastatic disease is often a moving target among studies, the oligometastatic hypothesis proposes a spectrum of disease dissemination based on biological virulence, ranging from single-site to widely metastatic, which still may have curative potential with metastasis-directed therapies as observed in studies of multiple cancer subtypes.13,14,23-25 Similarly, the OS rate in our patients with polymetastatic HNC likely reflects a different disease biology with an associated high disease burden and intrinsic resistance mechanisms. With regards to smoking, previous studies also demonstrated smoking as a poor OS factor likely secondary to the biological effects of cigarette smoking which promotes proliferation, tumorigenesis, and a metastatic phenotype.26,27 Moreover, smoking may simply be a representation of SCC, which occurs more frequently in smokers than in nonsmokers and is associated with a lower OS rate. Additionally, the observed effect of adjuvant systemic therapy on OS may be explained by disease burden. Specifically, patients in the present study who received adjuvant systemic therapy were more likely to have polymetastatic disease and underwent only partial local lung therapy (eg, SABR for an oligoprogressive lesions but not other lung lesions, which were addressed using systemic therapy).

Further examination of our patients with oligometastatic non-SCC vs oligometastatic SCC demonstrated significant excellent two-year OS rates of 100% and 66%, respectively. Given that the majority of non-SCC patients had papillary thyroid cancer, or adenoid cystic carcinoma, both which are often associated with an indolent disease course even in the presence of distant disease, the high two-year OS rates are not surprising. Survival rates may also be improving for these two diseases due to the presence of targetable mutations. While the OS rates in patients with these diseases may reflect the natural history of these cancers, with infrequent exception the disease treated with SABR was controlled. While comparatively the two-year OS rate for the oligometastatic SCC group is less than the non-SCC group, it was still 66%, much higher than predicted for patients in general with distant disease. While difficult to compare to other retrospective trials, our two-year OS rate for oligometastic SCC was higher than reported two-year OS rates after pulmonary metastasectomy (50%) or in other SABR trials (41%).16,21 It should be noted that direct comparisons are made difficult by different subgrouping and the numerical differences could very well fall within the range of statistical error.

4.3 ∣. Metachronous vs synchronous lung lesions

Surgical series have demonstrated worse OS for synchronous lung lesions than for metachronous lesions,28,29 whereas our results demonstrated no difference in OS of synchronous and metachronous lesions. The reason for the difference in these results is likely multifactorial, including varying definitions of synchronous lesions (development within three months after primary HNC treatment in our study compared with twelve and six months in older surgical studies) and different treatment eras (ie, differences in diagnostic imaging and therapeutic options). Although consensus definitions of metachronous and synchronous lesions are lacking, we chose the three-month cutoff to compare our results with those of a similar SABR study16 and to follow the International Agency for Research on Cancer recommendation of an interval shorter than six months.30 These results support the use of maximum therapy for LRC of primary HNC followed by aggressive LC of any lung lesion regardless of the timing of its development.

4.4 ∣. Limitations

This study was limited by the biases associated with retrospective studies. Moreover, even though patients received care across a 12-year period (2007 to 2018), tremendous advances in imaging, systemic therapy, and radiation techniques have been made in this short time interval. As described above, differentiating between metastatic and primary lung SCC was not possible from a histopathologic standpoint given the limitations of available molecular analyses. Finally, the study had a selection bias associated with referral for SABR given that the patients had limited metastatic burden and therefore were not necessarily representative of the general milieu of patients with metastatic disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the natural language processing team in the MD Anderson Department of Institutional Analytics and Informatics for helping us build the database, in particular, Chingyi Young, Samuel Camp, and Jeff Jin. We would also like to thank the Scientific Publication Services at MD Anderson in the editing process of this manuscript.

Funding information

NIH, Grant/Award Number: P30CA016672

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Dr Rosenthal serves on the scientific advisory board for Merck. Dr Phan serves on the scientific advisor board for Cyberknife for Accuray, Inc. Dr Tang has stock or other ownership in Corvus Pharmaceuticals, research funding from Varian Medical Systems, patents/royalties (Patent #9,175,079), and travel accommodations from Varian Medical Systems. Dr Fuller has received grants (unrelated to the present work) from GE Healthcare, Elekta AB, National Science Foundation (NSF 1557559), National Institutes of Health (NIH 1R56DE025248-01, 1R25EB025787-01, 5R01CA214825-02; 5R01CA225190-02; 5R01CA218148-02, CA088084), the Sabin Family Foundation, MD Anderson Institutional Research Grant. Dr Fuller has received payments for lectures from the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio and from Elekta AB. Dr Fuller has received royalties from Demos Medical Publishing. Dr Fuller has received travel/accommodations/meeting expenses from OHSU, Greater Baltimore Medical Center, University of Illinois, Elekta AB, and the Translational Research Institute (TRI) Australia. Dr Welsh serves on the scientific advisory boards of Reflexion Medical, MolecularMatch, Mavupharma, OncoResponse, and Checkmate; is a founder of Healios Oncology, MolecularMatch, and OncoResponse; and has received research and clinical trial support from Bristol-Myers Squibb; and research support from Merck, Aileron, Nanobiotix, Mavupharma, and Checkmate.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of adjuvant systemic therapy use in the study cohort

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (vs comparison group) | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value |

| Oligometastatic (vs polymetastatic) | 0.16 | 0.07-0.39 | <.001 | |||

| Nonwhite (vs white) | 1.47 | 0.51-4.26 | .475 | |||

| Age (continuous variable) | 0.98 | 0.95-1.02 | .395 | |||

| Squamous cell histology (vs non-squamous cell) | 0.50 | 0.22-1.15 | .102 | |||

| Oropharyngeal (vs nonoropharyngeal) | 1.05 | 0.44-2.51 | .917 | |||

| T3 stage (vs T0-T2) | 1.36 | 0.54-3.43 | .510 | |||

| T4 stage (vs T0-T2) | 0.90 | 0.32-2.56 | .847 | |||

| N1 stage (vs N0) | 4.27 | 1.52-11.97 | .006 | |||

| N2 stage (vs N0) | 1.19 | 0.43-3.27 | .743 | |||

| Primary treatment modality (vs concurrent chemo + EBRT) | ||||||

| EBRT alone | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Surgery + post-op EBRT | 0.74 | 0.22-2.55 | .636 | |||

| Induction chemo then concurrent chemo + EBRT | 0.51 | 0.11-2.44 | .397 | |||

| Surgery + post-op concurrent chemo + EBRT | 3.71 | 0.90-15.26 | .069 | |||

| Induction chemo then surgery then concurrent chemo + EBRT | 1.86 | 0.10-34.44 | .678 | |||

| Surgery alone | 1.44 | 0.37-5.57 | .593 | |||

| Radiation dose to primary site of disease (continuous variable) | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | .161 | |||

| Radiation fractions to primary site of disease (continuous variable) | 0.92 | 0.77-1.10 | .336 | |||

| Metachronous lung lesion (vs synchronous) | 0.34 | 0.11-1.10 | .071 | |||

| Synchronous lung lesion at time of diagnosis of primary disease (vs not) | 0.13 | 0.02-1.02 | .052 | |||

| Lung lesion laterality (vs LLL) | ||||||

| LUL | 1.00 | 0.30-3.35 | 1.000 | |||

| RLL | 0.75 | 0.20-2.77 | .666 | |||

| RML | 1.33 | 0.18-9.91 | .779 | |||

| RUL | 1.20 | 0.38-3.81 | .757 | |||

| Planning target volume, cm3 (continuous variable) | 1.01 | 0.996-1.02 | .186 | |||

| Gross tumor volume, cm3 (continuous variable) | 1.02 | 0.98-1.07 | .277 | |||

| Any pulmonary surgery history (vs none) | 0.55 | 0.14-2.16 | .395 | |||

| Smoking history | 0.61 | 0.27-1.38 | .237 | |||

| Current smoker (vs never-smoker) | 1.51 | 0.65-3.54 | .342 | |||

| Pack-year smoking history (continuous) | 1.00 | 0.98-1.02 | .656 | |||

| Any toxicity (vs none) | 1.44 | 0.57-3.62 | .444 | |||

| All sites of intrathoracic disease consolidated with stereotactic radiation (vs partial) | 0.07 | 0.02–0.22 | <.001 | 0.06 | 0.02-0.22 | <.001 |

| Local failure (vs none) | 2.03 | 0.27-15.03 | .488 | |||

| Regional failure (vs none) | 1.33 | 0.21-8.36 | .759 | |||

| Intrathoracic distant failure (vs none) | 2.59 | 1.06-6.30 | .036 | |||

Abbreviations: Chemo, chemotherapy; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; LLL, left lower lobe; LUL, left upper lobe; N/A, not applicable; post-op, postoperative; RLL, right lower lobe; RML, right middle lobe; RUL, right upper lobe.

TABLE A2.

Univariate and multivariate cox regression analysis of OS in the study cohort

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (vs comparison group) | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value |

| Oligometastatic (vs polymetastatic) | 0.42 | 0.23-0.74 | .003 | 0.30 | 0.14-0.64 | .002 |

| Nonwhite (vs white) | 0.77 | 0.30-1.94 | .573 | |||

| Age (continuous variable) | 1.04 | 1.02-1.07 | .002 | |||

| Squamous cell histology (vs non-squamous cell) | 2.33 | 1.12–4.81 | .023 | |||

| Oropharyngeal (vs nonoropharyngeal) | 1.55 | 0.86-2.80 | .144 | |||

| T3 stage (vs T0-T2) | 0.95 | 0.48-1.86 | .871 | |||

| T4 stage (vs T0-T2) | 1.01 | 0.50-2.02 | .988 | |||

| N1 stage (vs N0) | 1.28 | 0.62-2.64 | .501 | |||

| N2 stage (vs N0) | 1.31 | 0.67-2.57 | .432 | |||

| Primary treatment modality (vs concurrent chemo + EBRT) | ||||||

| EBRT alone | 1.58 | 0.60-4.17 | .354 | |||

| Surgery + post-op EBRT | 1.18 | 0.48-2.90 | .719 | |||

| Induction chemo then concurrent chemo + EBRT | 1.93 | 0.71-5.26 | .201 | |||

| Surgery + post-op concurrent chemo + EBRT | 1.69 | 0.66-4.35 | .273 | |||

| Induction chemo then surgery then concurrent chemo + EBRT | 4.72 | 0.98-22.68 | .053 | |||

| Surgery alone | 0.31 | 0.07-1.42 | .131 | |||

| Radiation dose to primary site of disease (continuous variable) | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | .735 | |||

| Radiation fractions to primary site of disease (continuous variable) | 0.95 | 0.85-1.07 | .399 | |||

| Metachronous lung lesion (vs synchronous) | 1.77 | 0.93-3.36 | .081 | |||

| Synchronous lung lesion at time of diagnosis of primary disease (vs not) | 1.09 | 0.49-2.43 | .841 | |||

| Adjuvant systemic therapy (vs none) | 1.97 | 1.08-3.58 | .026 | 2.65 | 1.21–5.81 | .015 |

| Lung lesion laterality (vs LLL) | ||||||

| LUL | 1.50 | 0.61-3.68 | .376 | |||

| RLL | 0.87 | 0.31-2.43 | .796 | |||

| RML | 3.72 | 0.94-14.63 | .060 | |||

| RUL | 0.90 | 0.37-2.23 | .826 | |||

| Planning target volume, cm3 (continuous variable) | 1.01 | 1.00-1.01 | .080 | |||

| Gross tumor volume, cm3 (continuous variable) | 1.02 | 0.99-1.05 | .244 | |||

| Any pulmonary surgery history (vs none) | 0.97 | 0.41-2.92 | .936 | |||

| Smoking history (vs none) | 4.50 | 2.10-9.63 | <.001 | 4.46 | 1.67-11.90 | .003 |

| Current smoker (vs never-smoker) | 0.24 | 0.11-0.53 | <.001 | |||

| Pack-year smoking history (continuous) | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | .877 | |||

| Any toxicity (vs none) | 0.85 | 0.44-1.64 | .630 | |||

| Local-regional failure (vs none) | 0.08 | 0.01-0.50 | .007 | |||

Abbreviations: chemo, chemotherapy; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; LLL, left lower lobe; LUL, left upper lobe; post-op, postoperative; RLL, right lower lobe; RML, right middle lobe; RUL, right upper lobe.

TABLE A3.

Univariate and multivariate cox regression analysis of intrathoracic distant failure in the study cohort

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (vs comparison group) | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value |

| Oligometastatic (vs polymetastatic) | 0.63 | 0.81-1.05 | .233 | |||

| Nonwhite (vs white) | 0.40 | 0.10-1.70 | .217 | 0.17 | 0.03–0.98 | .048 |

| Age (continuous variable) | 0.98 | 0.95-1.01 | .159 | |||

| Squamous cell histology (vs non-squamous cell) | 1.30 | 0.57-2.95 | .532 | |||

| Oropharyngeal (vs nonoropharyngeal) | 2.13 | 1.00-4.51 | .049 | |||

| T3 stage (vs T0-T2) | 0.81 | 0.35-1.85 | .609 | |||

| T4 stage (vs T0-T2) | 0.37 | 0.12-1.12 | .078 | 0.25 | 0.07–0.90 | .033 |

| N1 stage (vs N0) | 0.96 | 0.35-2.64 | .934 | |||

| N2 stage (vs N0) | 1.51 | 0.65-3.51 | .333 | |||

| Primary treatment modality (vs concurrent chemo + EBRT) | ||||||

| EBRT alone | 0.79 | 0.20-3.17 | .742 | |||

| Surgery + post-op EBRT | 1.08 | 0.36-3.23 | .892 | |||

| Induction chemo then concurrent chemo + EBRT | 0.72 | 0.14-3.57 | .687 | |||

| Surgery + post-op concurrent chemo + EBRT | 3.25 | 1.14-9.24 | .027 | |||

| Induction chemo then surgery then concurrent chemo + EBRT | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Surgery alone | 0.22 | 0.03-1.85 | .164 | |||

| Radiation dose to primary site of disease (continuous variable) | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | .059 | |||

| Radiation fractions to primary site of disease (continuous variable) | 0.80 | 0.65-1.00 | .047 | |||

| Metachronous lung lesion (vs synchronous) | 1.08 | 0.35-6.29 | .596 | |||

| Synchronous lung lesion at time of diagnosis of primary disease (vs not) | 0.69 | 0.21-2.30 | .549 | |||

| Adjuvant systemic therapy (vs none) | 2.82 | 1.31-6.05 | .008 | |||

| Lung lesion laterality (vs LLL) | ||||||

| LUL | 0.85 | 0.26-2.78 | .786 | |||

| RLL | 1.05 | 0.32-3.44 | .937 | |||

| RML | 1.32 | 0.15-11.56 | .801 | |||

| RUL | 1.08 | 0.37-3.17 | .887 | |||

| Planning target volume, cm3 (continuous variable) | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | .761 | |||

| Gross tumor volume, cm3 (continuous variable) | 1.01 | 0.97-1.05 | .705 | |||

| Any pulmonary surgery history (vs none) | 1.81 | 0.69-4.78 | .228 | |||

| Smoking history | 1.04 | 0.49-2.20 | .914 | |||

| Current smoker (vs never-smoker) | 0.78 | 0.37-1.67 | .528 | |||

| Pack-year smoking history (continuous) | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | .949 | |||

| Any toxicity (vs none) | 1.70 | 0.78-3.69 | .179 | |||

Abbreviations: Chemo, chemotherapy; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; LLL, left lower lobe; LUL, left upper lobe; N/A, not applicable; post-op, postoperative; RLL, right lower lobe; RML, right middle lobe; RUL, right upper lobe.

TABLE A4.

Univariate and multivariate cox regression analysis of local-regional failure in the study cohort

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (vs comparison group) | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value |

| Oligometastatic (vs polymetastatic) | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Nonwhite (vs white) | 2.91 | 0.73-11.70 | 0.131 | |||

| Age (continuous variable) | 1.01 | 0.97-1.05 | 0.613 | |||

| Squamous cell histology (vs non-squamous cell) | 4.48 | 0.56-35.83 | 0.158 | |||

| Oropharyngeal (vs nonoropharyngeal) | 0.68 | 0.14-3.26 | 0.626 | |||

| T3 stage (vs T0-T2) | 1.01 | 0.22-4.52 | 0.992 | |||

| T4 stage (vs T0-T2) | 0.78 | 0.14-4.27 | 0.776 | |||

| N1 stage (vs N0) | 1.57 | 0.22-11.14 | 0.653 | |||

| N2 stage (vs N0) | 3.26 | 0.63-16.87 | 0.158 | |||

| Primary treatment modality (vs concurrent chemo + EBRT) | ||||||

| EBRT alone | 0.80 | 0.07-8.88 | 0.859 | |||

| Surgery + post-op EBRT | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Induction chemo then concurrent chemo + EBRT | 1.04 | 0.09-11.53 | 0.972 | |||

| Surgery + post-op concurrent chemo + EBRT | 3.16 | 0.58-17.31 | 0.185 | |||

| Induction chemo then surgery then concurrent chemo + EBRT | 7.97 | 0.69-91.57 | 0.096 | |||

| Surgery alone | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Radiation dose to primary site of disease (continuous variable) | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 0.646 | |||

| Radiation fractions to primary site of disease (continuous variable) | 0.76 | 0.49-1.17 | 0.208 | |||

| Metachronous lung lesion (vs synchronous) | 1.18 | 0.24-5.72 | 0.835 | |||

| Synchronous lung lesion at time of diagnosis of primary disease (vs not) | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Adjuvant systemic therapy (vs none) | 1.70 | 0.46-6.35 | 0.428 | |||

| Lung lesion laterality (vs LLL) | ||||||

| LUL | 0.44 | 0.07-2.66 | 0.374 | |||

| RLL | 0.25 | 0.03-2.43 | 0.234 | |||

| RML | 1.85 | 0.19-17.97 | 0.595 | |||

| RUL | 0.34 | 0.06-2.01 | 0.232 | |||

| Planning target volume, cm3 (continuous variable) | 1.01 | 0.99-1.02 | 0.545 | |||

| Gross tumor volume, cm3 (continuous variable) | 0.98 | 0.89-1.08 | 0.730 | |||

| Any pulmonary surgery history (vs none) | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Smoking history | 7.82 | 0.98-62.58 | 0.053 | 7.88 | 0.98-63.61 | 0.053 |

| Current smoker (vs never-smoker) | 0.11 | 0.01-0.93 | 0.043 | |||

| Pack-year smoking history (continuous) | 1.00 | 0.97-1.02 | 0.730 | |||

| Any toxicity (vs none) | 1.27 | 0.32-5.13 | 0.733 | |||

Abbreviations: chemo, chemotherapy; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; LLL, left lower lobe; LUL, left upper lobe; N/A, not applicable; post-op, postoperative; RLL, right lower lobe; RML, right middle lobe; RUL, right upper lobe.

TABLE A5.

Toxic effects of SABR for pulmonary metastases in the 82 study patients

| Number (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxic effect | Patients affected | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 |

| Hemoptysis | 1 (1) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Rib fracture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brachial plexopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chest wall pain | 4 (5) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Pulmonary | 14 (17) | 12 (15) | 2 (2) | 0 |

Note: Toxicity was graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0).

Abbreviations: N/A, not applicable; SABR, stereotactic ablative radiotherapy.

TABLE A6.

Toxic effects of SABR among oligometastatic vs polymetastatic patients metastases stratified by pulmonary disease burden

| Polymetastatic no. (%) |

Oligometastatic no. (%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 28 | 54 | — |

| Hemoptysis | 0 | 1 (2) | 1.000 |

| Rib fracture | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Brachial plexopathy | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Chest wall pain | 1 (4) | 3 (6) | 1.000 |

| Pulmonary | 5 (18) | 9 (17) | 1.000 |

Note: Toxicity was graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0).

Abbreviation: SABR, stereotactic ablative radiotherapy.

FIGURE A1.

Kaplan-Meier OS curves for the study patients with oligometastatic disease grouped according to non-squamous cell vs squamous cell histology

FIGURE A2.

Kaplan-Meier OS curves for all patients grouped according to metachronous vs synchronous disease

FIGURE A3.

Kaplan-Meier OS curves for the patients with squamous cell lung lesions grouped according to metachronous vs synchronous disease

REFERENCES

- 1.Zbaren P, Lehmann W. Frequency and sites of distant metastases in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. An analysis of 101 cases at autopsy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:762–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotwall C, Sako K, Razack MS, Rao U, Bakamjian V, Shedd DP. Metastatic patterns in squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1987;154:439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duprez F, Berwouts D, De Neve W, et al. Distant metastases in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2017;39:1733–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1116–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen EEW, Soulieres D, Le Tourneau C, et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;393:156–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tota JE, Best AF, Zumsteg ZS, Gillison ML, Rosenberg PS, Chaturvedi AK. Evolution of the oropharynx Cancer epidemic in the United States: moderation of increasing incidence in younger individuals and shift in the burden to older individuals. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1538–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim H, Devesa SS, Sosa JA, Check D, Kitahara CM. Trends in thyroid Cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1974–2013. JAMA. 2017;317:1338–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trosman SJ, Koyfman SA, Ward MC, et al. Effect of human papillomavirus on patterns of distant metastatic failure in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with chemoradiotherapy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welch HG, Kramer BS, Black WC. Epidemiologic signatures in Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1378–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weichselbaum RR, Hellman S. Oligometastases revisited. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pastorino U, Buyse M, Friedel G, et al. Long-term results of lung metastasectomy: prognostic analyses based on 5206 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113:37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu D, Labow DM, Dang N, et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy for head and neck cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:572–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard of care palliative treatment in patients with oligometastatic cancers (SABR-COMET): a randomised, phase 2, open-label trial. Lancet. 2019;393:2051–2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez DR, Tang C, Zhang J, et al. Local consolidative therapy Vs. maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: long-term results of a multi-institutional, phase II, randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1558–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez DR, Blumenschein GR Jr, Lee JJ, et al. Local consolidative therapy versus maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer without progression after first-line systemic therapy: a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1672–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bates JE, De Leo AN, Morris CG, et al. Oligometastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck treated with stereotactic body ablative radiotherapy: single-institution outcomes. HeadNeck. 2019;41:2309–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang JY, Bezjak A, Mornex F, IASLC Advanced Radiation Technology Committee. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for centrally located early stage non-small-cell lung cancer: what we have learned. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishino M, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya NH, van den Abbeele AD. Revised RECIST guideline version 1.1: what oncologists want to know and what radiologists need to know. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Homer RJ. Pathologists’ staging of multiple foci of lung cancer: poor concordance in absence of dramatic histologic or molecular differences. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143:701–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jagirdar J Application of immunohistochemistry to the diagnosis of primary and metastatic carcinoma to the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:384–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiono S, Kawamura M, Sato T, et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy for pulmonary metastases of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:856–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray P, Franks K, Hanna GG. A systematic review of outcomes following stereotactic ablative radiotherapy in the treatment of early-stage primary lung cancer. BrJ Radiol. 2017;90:20160732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitroda SP, Chmura SJ, Weichselbaum RR. Integration of radiotherapy and immunotherapy for treatment of oligometastases. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:e434–e442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ost P, Reynders D, Decaestecker K, et al. Surveillance or metastasis-directed therapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer recurrence: a prospective, randomized multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:446–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milano MT, Katz AW, Zhang H, Okunieff P. Oligometastases treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy: long-term follow-up of prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83: 878–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsons A, Daley A, Begh R, Aveyard P. Influence of smoking cessation after diagnosis of early stage lung cancer on prognosis: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warren GW, Sobus S, Gritz ER. The biological and clinical effects of smoking by patients with cancer and strategies to implement evidence-based tobacco cessation support. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e568–e580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez DR, Rimner A, Simone CB 2nd, et al. The use of radiation therapy for the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma: expert opinion from the National Cancer Institute thoracic malignancy steering committee, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:1172–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dequanter D, Shahla M, Lardinois I, et al. Second primary lung malignancy in head and neck cancer patients. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128:11–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogt A, Schmid S, Heinimann K, et al. Multiple primary tumours: challenges and approaches, a review. ESMO Open. 2017;2:e000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]